Submitted:

12 June 2025

Posted:

16 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

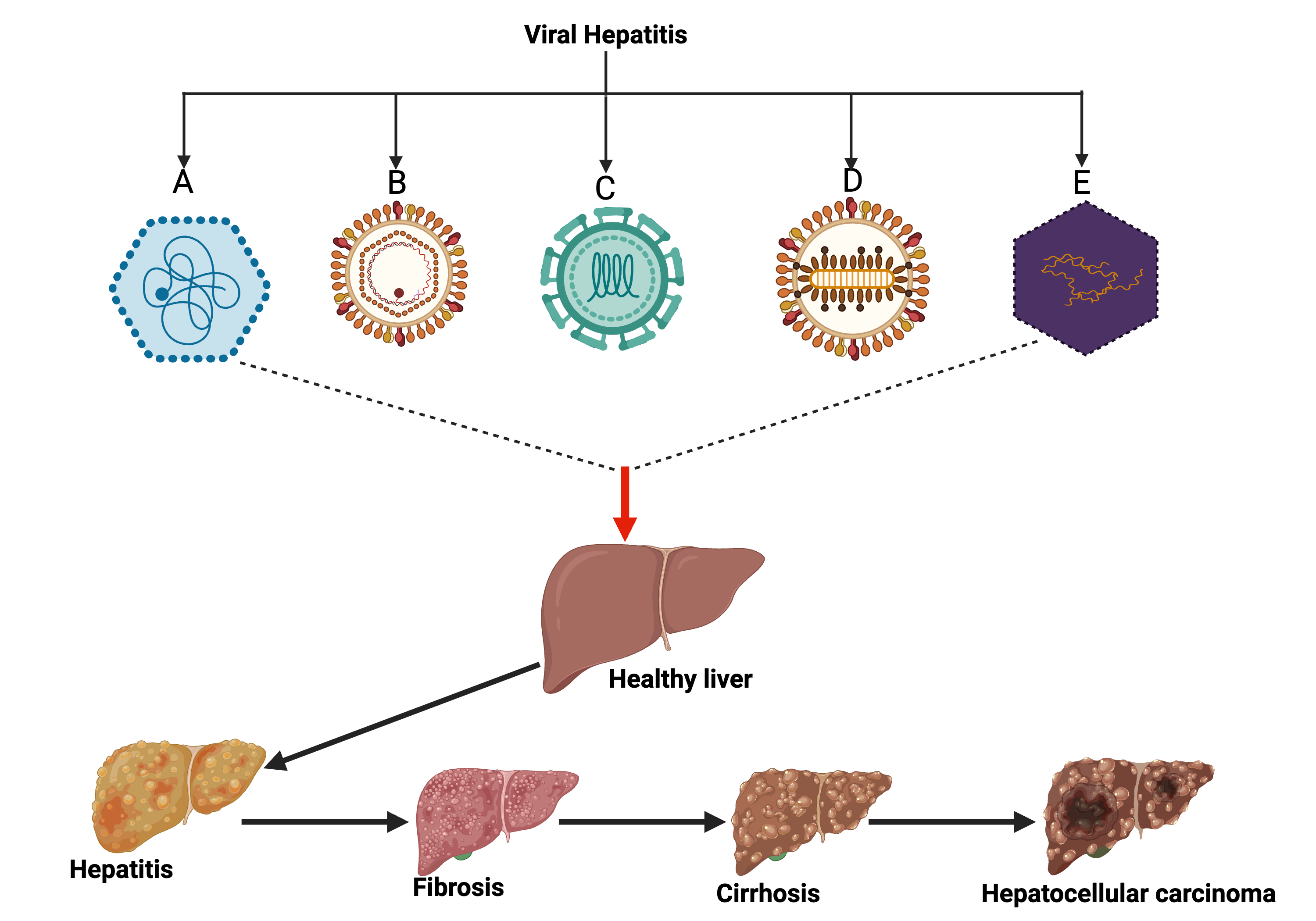

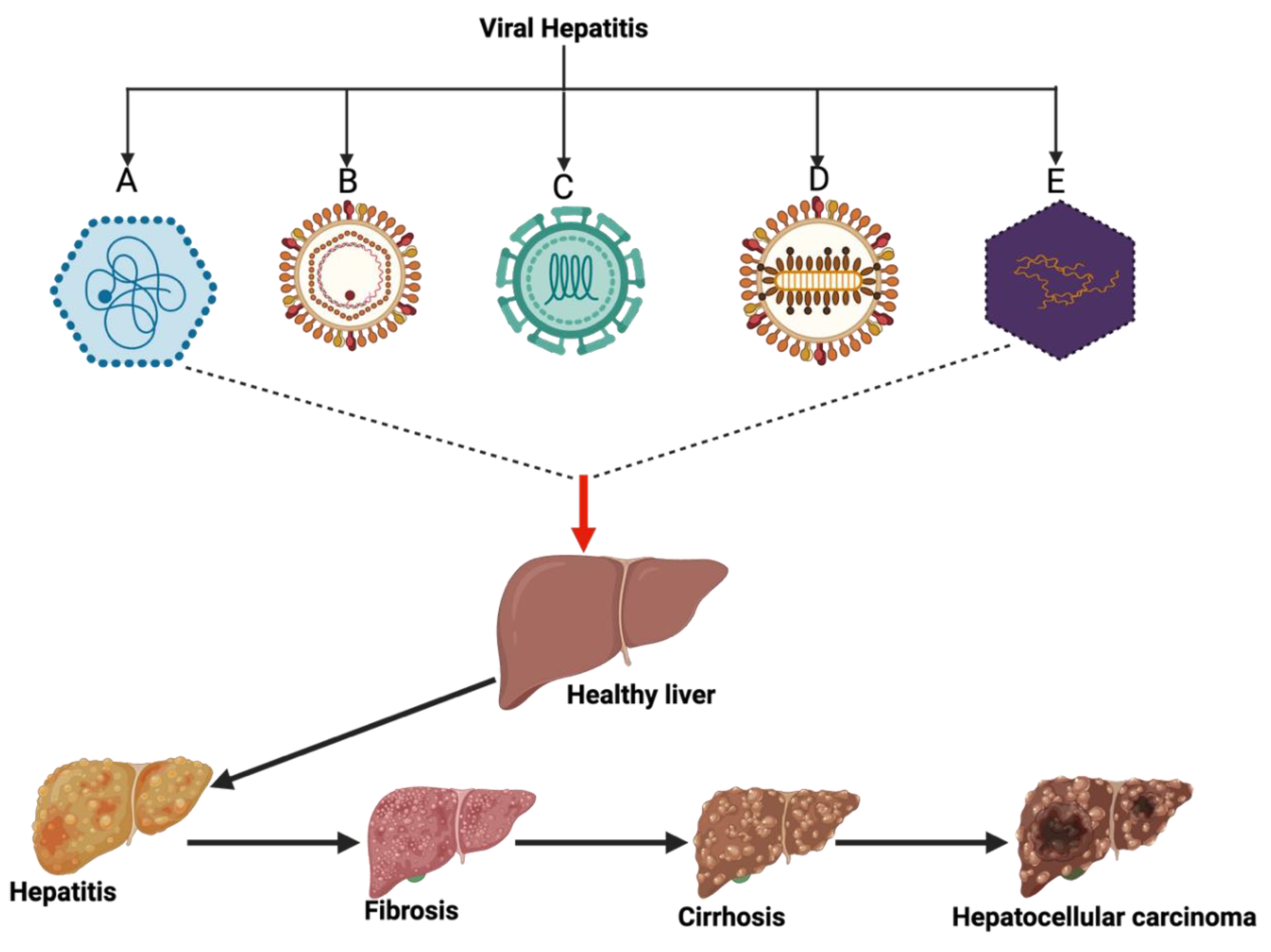

1. Introduction

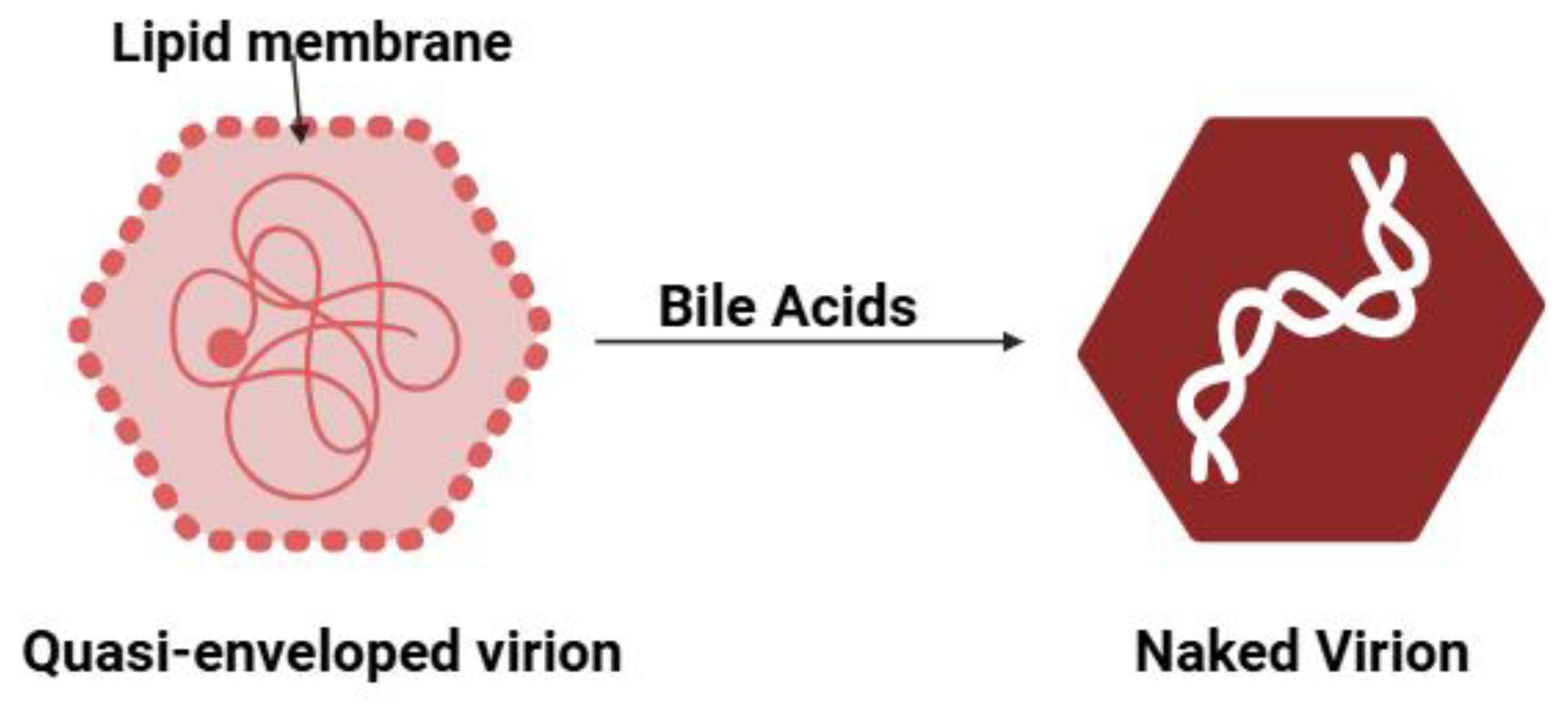

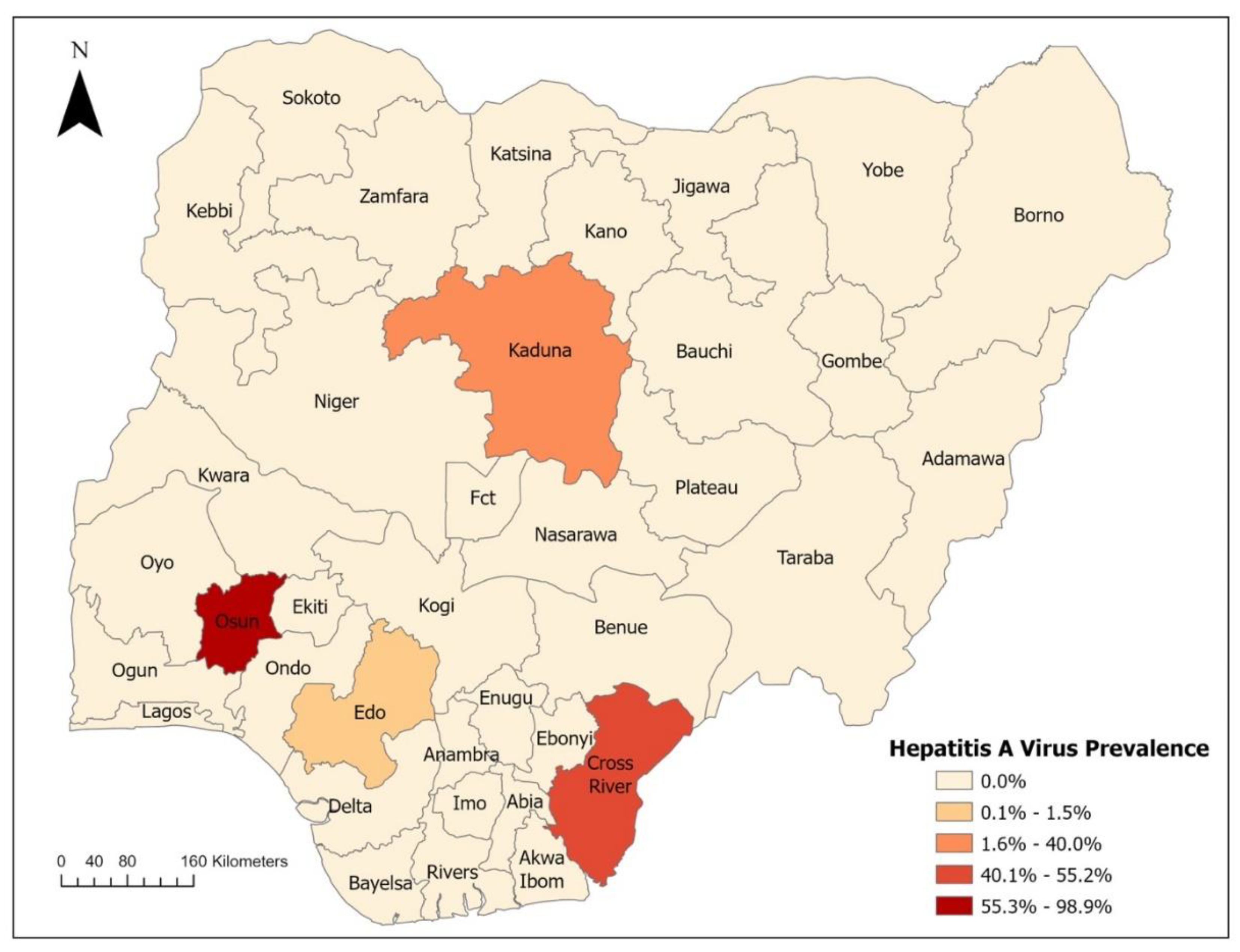

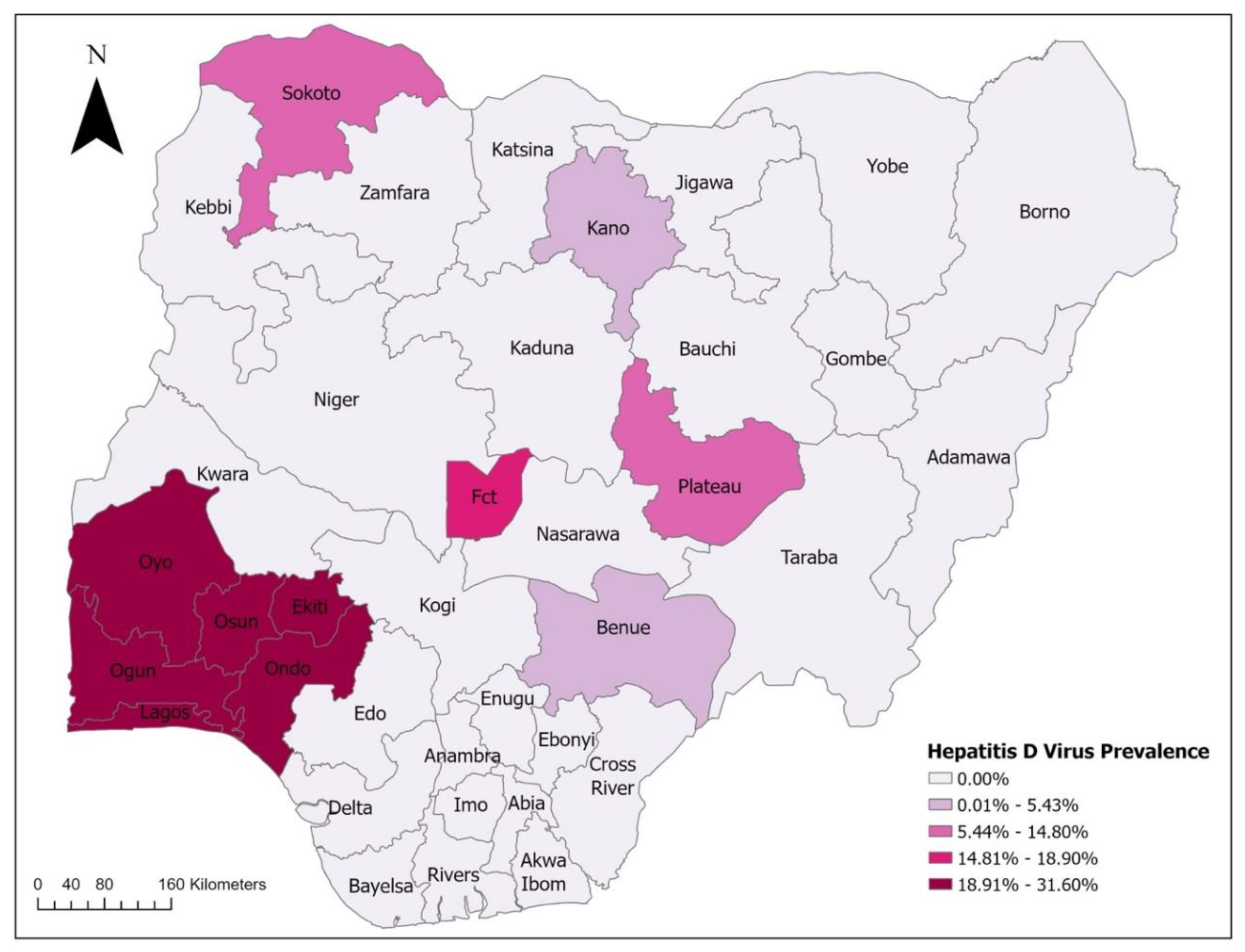

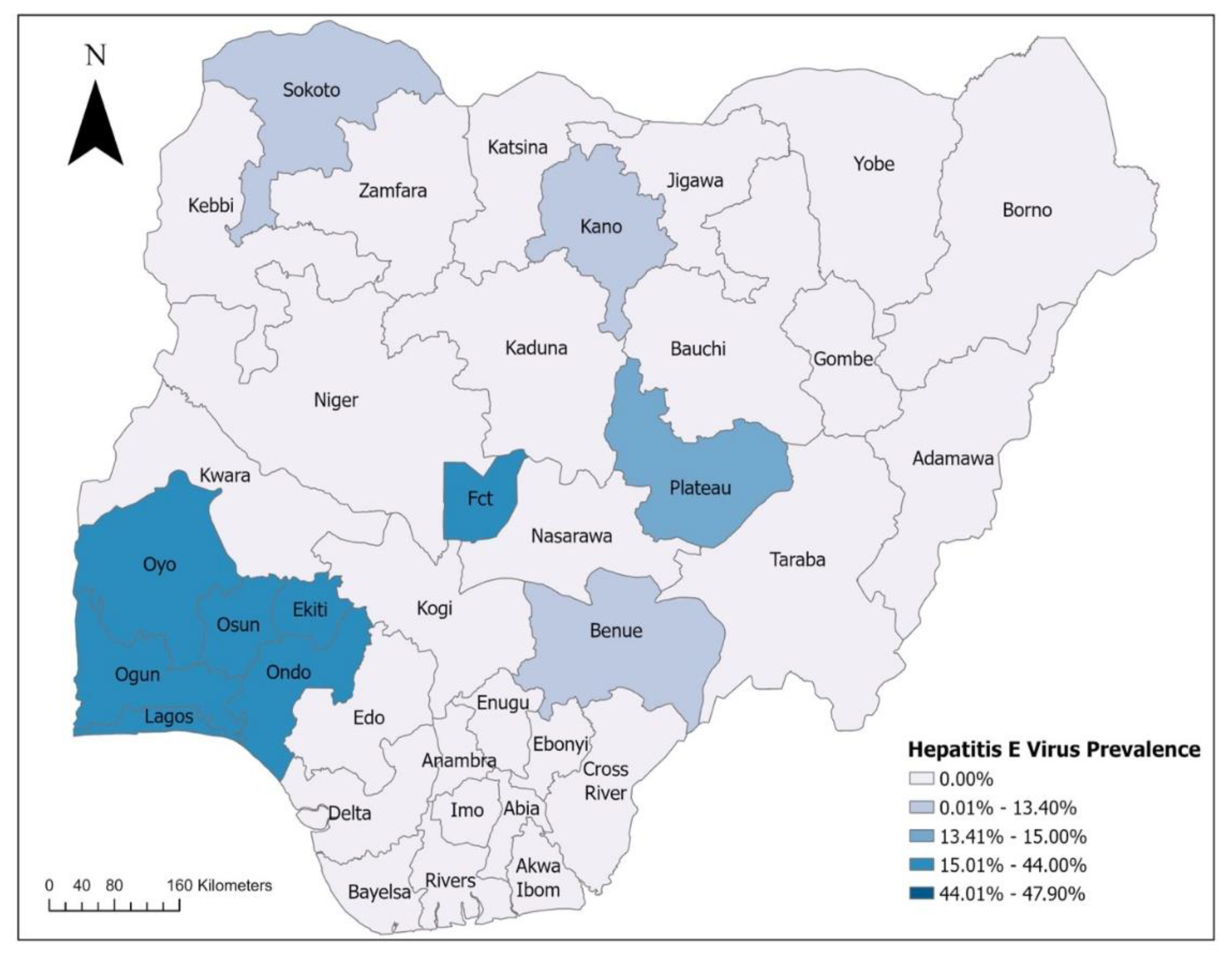

2. Epidemiology of Viral Hepatitis in Nigeria

3. Role of Traditional Medicine in Treatment Practices

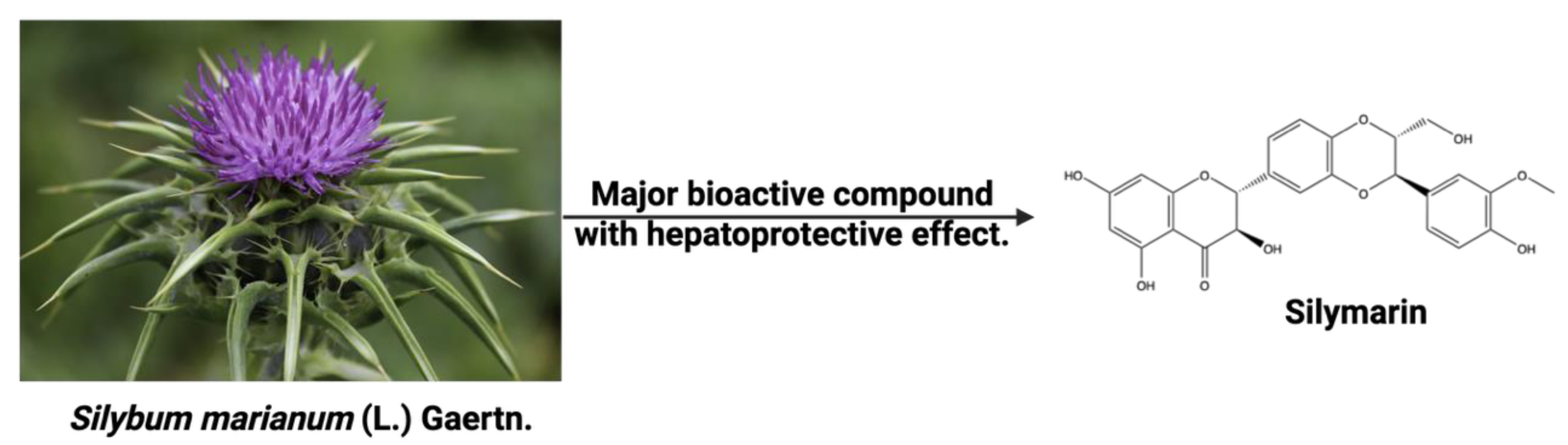

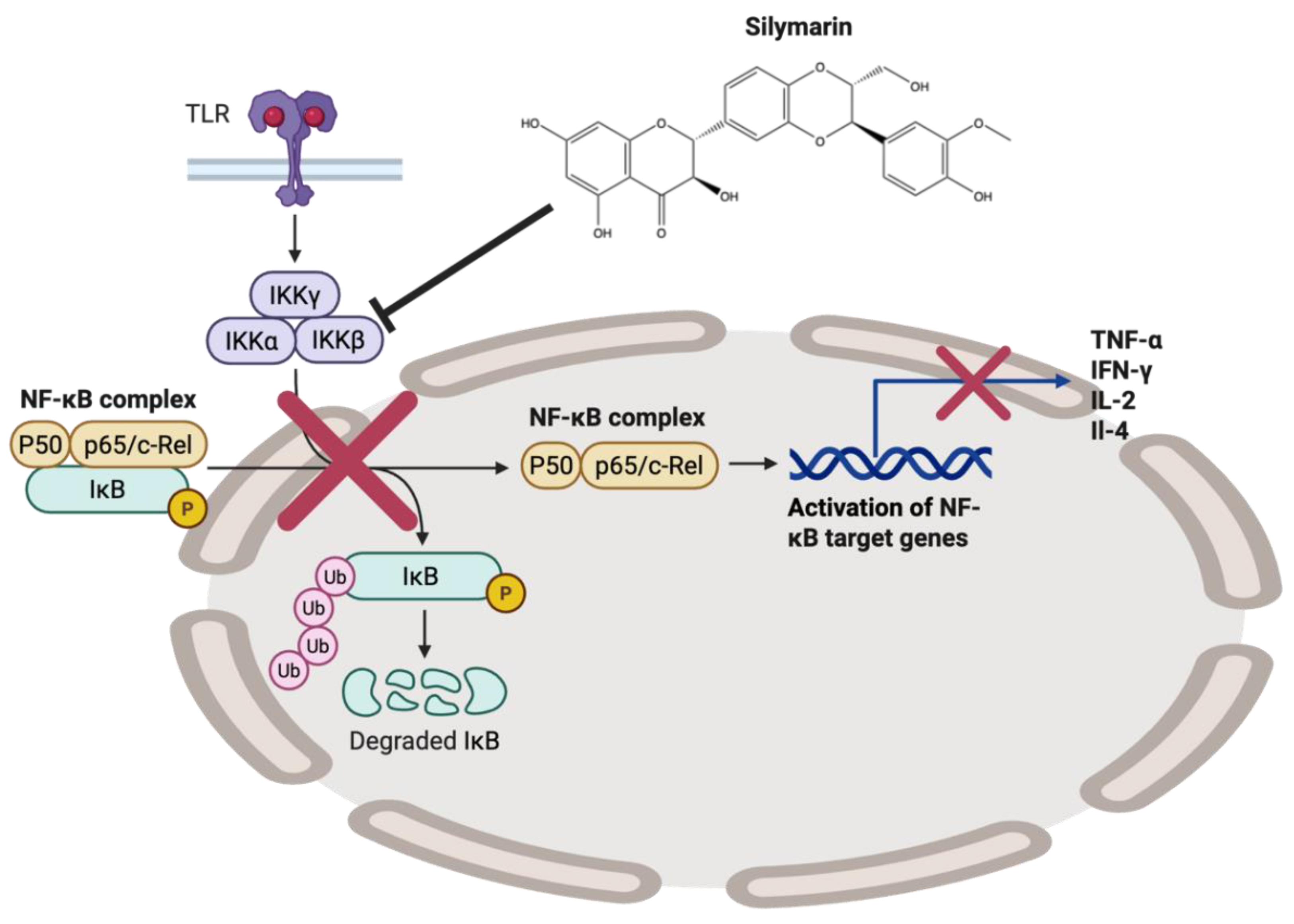

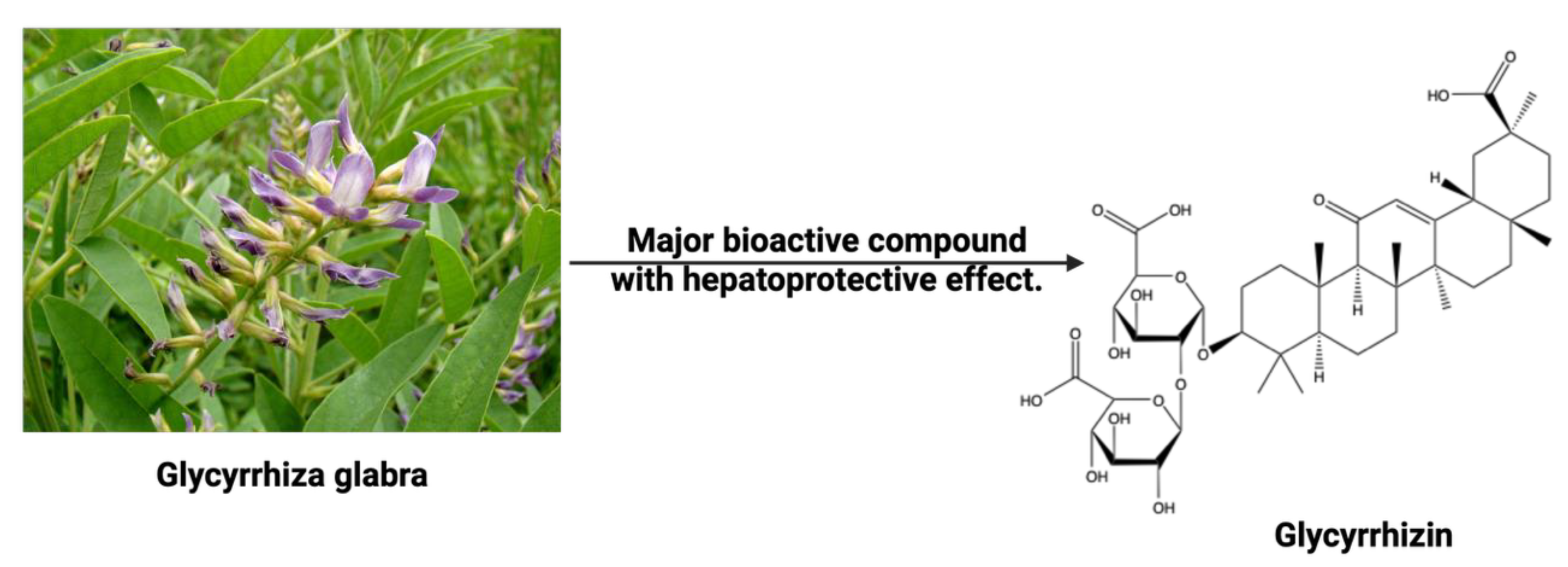

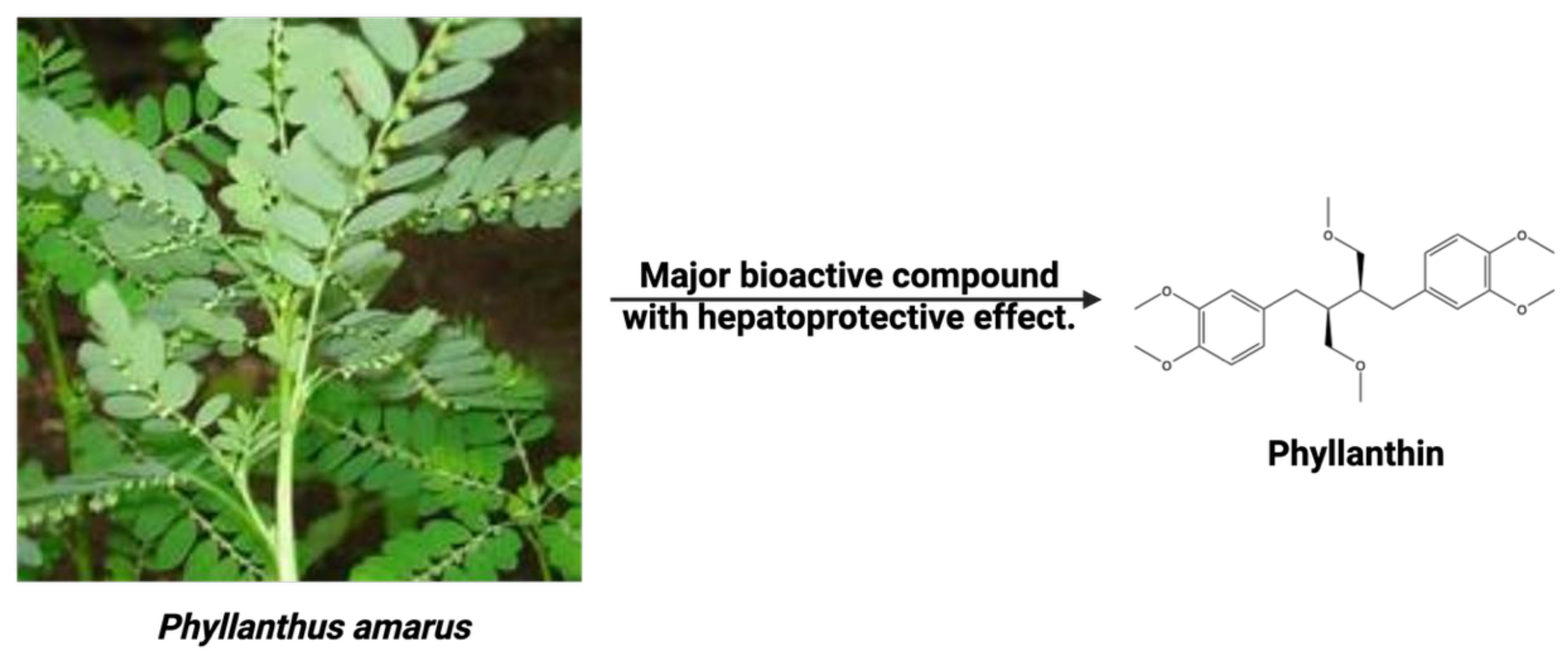

3.1. Selected Medicinal Plants Effective for Hepatitis Treatment and Their Possible Mechanism of Action

| Medicinal Plants | Major Bioactive Agents | Hepatoprotective Effects | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Picrorhiza kurroa | Picroside I, picroside II, apocyanin, and cucurbitacins | It enhances antioxidant activities and scavenges the superoxide anion (O2•−). | [208,209] |

| Adrographis paniculata | Andrographolide | It inhibits viral replication and reduces liver inflammation and injury. It also modulates the NF-kB pathway, thereby decreasing the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-6, IL-1β, TNF-α), scavenges free radicals and enhances antioxidant activities. | [210-212] |

| Eclipta alba | Wedelolactone, demethylwedelolactone | It stimulates regeneration of hepatocytes, regulates the levels of hepatic microsomal drug-metabolizing enzymes, and inhibits HCV replication | [213,214] |

| Carica papaya | Papain, phenolic compounds, flavonoids, alkaloids (carpaine), cyanogenic chemicals (benzyl glucosinolates) | It decreases lipid peroxidation, pro-inflammatory cytokines such as tumour NF-α and IL-6, AST and ALT activies, and improves enzymatic antioxidants CAT and SOD. | [215] |

| Phyllanthus niruri L. | Quercetin rhamnoside, quercetin glucoside, gallic acid, geranin | It inhibits cellular DNA polymerase activity during HBV replication, HBV DNA synthesis and secretion of HBsAg and HBcAg | [216-218] |

| Musa sapientum L. | Alkaloids, phenols, terpenoids, flavonoids, phytosterols | It mediates antioxidant activities, improves hepatocyte regeneration, and inhibits the expression of inflammatory cytokines. Promotes the production of anti-inflammatory cytokines | [219] |

| Syzygium aromaticum L. | Eugenol, β-caryophyllene | It inhibits hepatic cell proliferation into fibroblasts, mediates antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities, and enhances liver defence mechanism | [220,221] |

| Psidium guajava L. | Flavonoids, gallic acids, catechins, epicatechins | It lowers elevated levels of serum AST, ALT, ALP, and bilirubin, and neutralizes free radicals. | [222,223] |

| Ziziphus mauritiana L. | Phenolic compounds, flavonoids, tannins, alkaloids, saponins | It lowers AST, ALT, ALP, total bilirubin and lipid peroxide levels, prevents lipid peroxidation, and increases levels of glutathione and vitamin E | [224,225] |

| Entada africana Guill. & Perr. | Flavonoids, triterpenes, saponins, sugar | It enhances the expression of heme oxygenase-1 and 2’-5’ oligoadenylate synthetase-3, inhibits cytochrome P450 2E1 (CYP2E1), activates Nuclear factor-erythroid 2-related factors-2 (Nrf2) signaling pathway, and Inhibits HCV replication | [226,227] |

| Allium sativum L. | Allicin, alliin, diallyl sulfide, ajoene | Inhibit viral cell cycle. Reduction of cellular oxidative stress. Reduces viral load and improves liver function. Regulates lipid metabolism | [228,229] |

| Morus alba | Alkaloids (1-deoxynojirimycin), flavonoids, polyphenols | It inhibits the maturation of HBV, suppresses the glycosylation of viral envelop glycoproteins, reduces HBsAg, HBeAg, and HBV DNA, and inhibits the activity of HCV NS3 protease | [230,231] |

| Phyllanthus amarus Schum. & Thonn. | Lignans (phyllanthin and hypophyllanthin), flavonoids (quercetin) | It inhibits viral DNA polymerase and replication, mediates antioxidant and immunomodulatory activities, scavenges free radicals, and reduces lipid peroxidation of hepatic and intracellular membranes. | [232,233] |

| Momordica charantia L. | MAP30, α-momorcharin, triterpenes, saponins, flavonoids | It reduces liver inflammation, scavenges free radicals, reduces oxidative stress, inhibits viral DNA replication, HBV proteins (HBsAg and HBeAg) secretion in HepG2 cells, and stimulates hepatocyte regeneration | [234-236] |

| Adansonia digitata L. | Triterpenoids, flavonoids, tannin, carotenoids | It neutralizes free radicals, increases GSH, CAT, and SOD levels, reduces serum levels of AST, ALT, ALP, total bilirubin, and total proteins as well as lowers serum TNF-α level. | [237,238] |

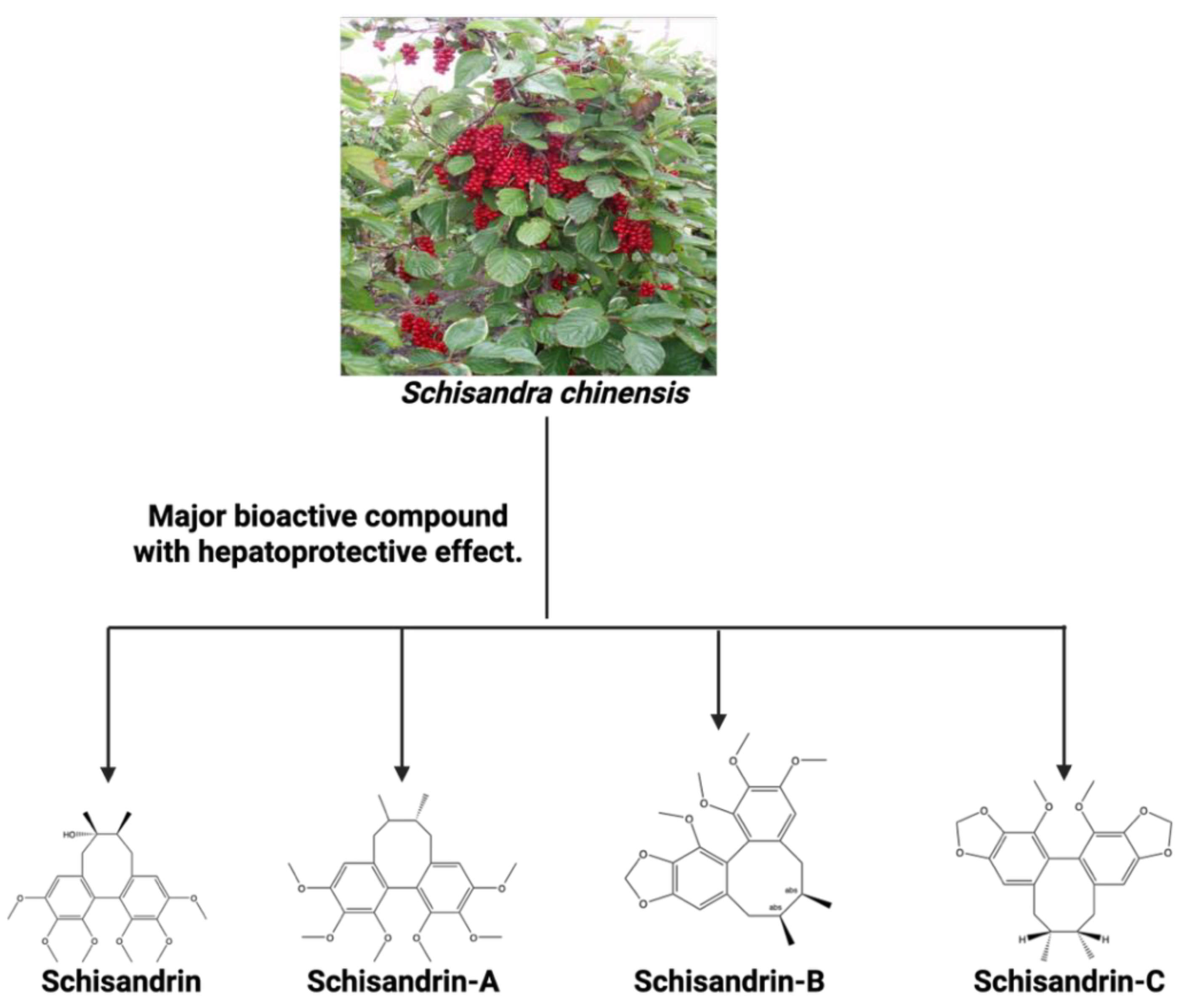

| Schisandra chinensis | Schisandrin, Schisandrin A, Schisandrin B, and Schisandrin C | It enhances the activation of the cGAS-STING pathway. When combined with luteolin, it HBV replication and further stimulating the activation of the cGAS-STING pathway in macrophages. | [181,182] |

4. Safety Concerns and Regulation of Traditional Medicine in Nigeria

5.0. Future Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviation

| ALP | - Alkaline Phosphatase |

| ALT | - Alanine Aminotransferase |

| ART | - Antiretroviral Therapy |

| AST | - Aspartate Aminotransferase |

| CAT | - Catalase |

| CCl₄ | - Carbon Tetrachloride |

| cGAS-STING | – Cyclic GMP-AMP synthase – Stimulator of interferon genes |

| COX-2 | - Cyclooxygenase 2 |

| DALYs | - Decline in Age-Standardised Disability adjusted life years |

| DNA | - Deoxyribonucleic Acid |

| EGF | - Epidermal growth factor |

| EN I | - Enhancer I |

| GBD | - Global Burden of Disease |

| GBD | - Global Burden of Disease |

| GMP | - Good Manufacturing Practices |

| GPX | - Glutathione peroxidase |

| GSH | - Glutathione |

| GST | - Glutathione S-transferase |

| HAV | - Hepatitis A Virus |

| HBcAg | - Hepatitis B Core Antigen |

| HBeAg | - Hepatitis B e-antigen |

| HBsAG | - Hepatitis B surface antigen |

| HBsAg | - Hepatitis B Surface Antigen |

| HBV | - Hepatitis B Virus |

| HCC | - Hepatocellular carcinoma |

| HCV | - Hepatitis C Virus |

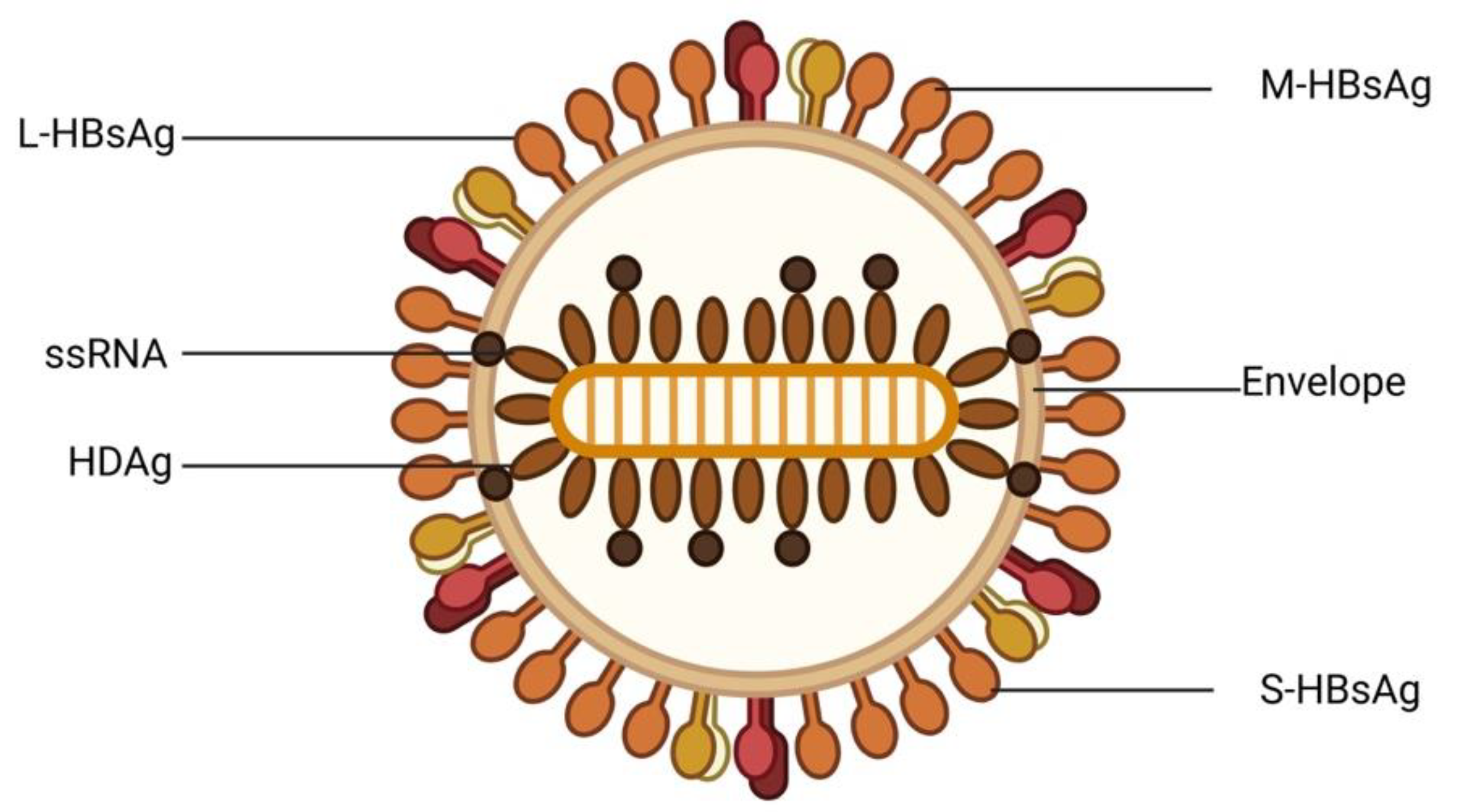

| HDAg | - Hepatitis delta antigen |

| HDV | - Hepatitis D Virus |

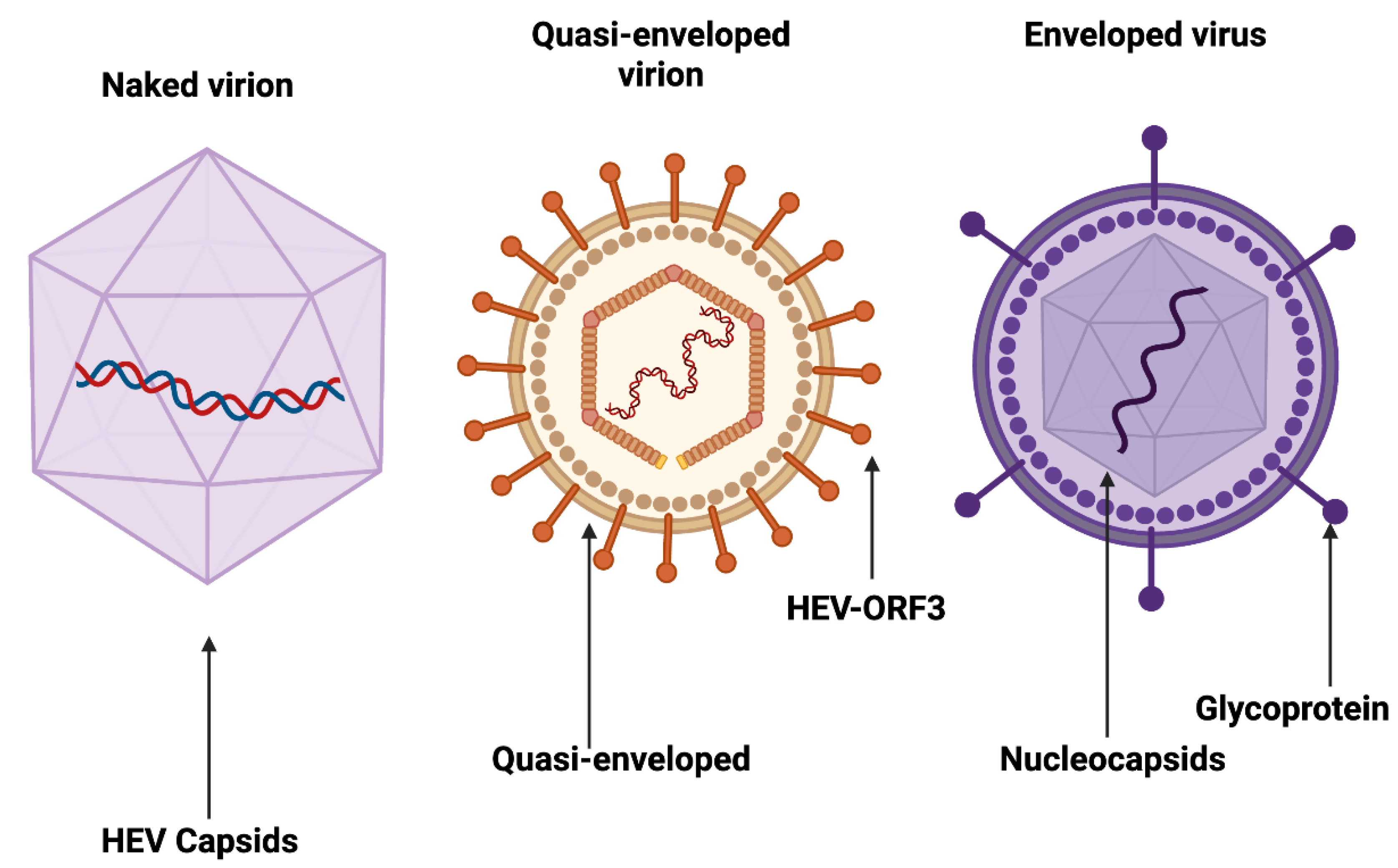

| HEV | - Hepatitis E Virus |

| HIV | - Human Immunodeficiency Virus |

| IFIT1 | - Interferon Alpha/Beta Receptor 1 |

| IFN-γ | - Interferon-gamma |

| IgG | - Immunoglobulin G |

| IgM | - Immunoglobulin M |

| IL | -Interleukin |

| ISG15 | - Interferon Stimulated Gene 15 |

| L-HDAg | - Large Hepatitis Delta Antigen |

| LSTMB | - Lagos State Traditional Medicine Board |

| MDA | - Malondialdehyde |

| NAFDAC | - National Agency for Food Drug Administration and Control |

| NF-κb | - Nuclear factor kappa B |

| ORFs | - Open Reading Frame |

| RNA | - Ribonucleic Acid |

| S-HDAg | - Small Hepatitis Delta Antigen |

| SDI | - Social Demographic Index |

| SGOT | - Serum glutamic oxaloacetic transaminase |

| SGPT | - Serum glutamic-pyruvic transaminase (SGPT) |

| SOD | - Superoxide dismutase |

| TBK1 | - TANK-binding kinase 1 |

| TM | - Traditional medicine |

| TNF-α | - Tumour necrosis factor - alpha |

| WHO | - World Health Organization |

References

- Lanini, S.; Ustianowski, A.; Pisapia, R.; Zumla, A.; Ippolito, G. Viral Hepatitis: Etiology, Epidemiology, Transmission, Diagnostics, Treatment, and Prevention. Infect Dis Clin North Am 2019, 33, 1045–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jefferies, M.; Rauff, B.; Rashid, H.; Lam, T.; Rafiq, S. Update on global epidemiology of viral hepatitis and preventive strategies. World J Clin Cases 2018, 6, 589–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Owumi, S.E.; Kazeem, A.I.; Wu, B.; Ishokare, L.O.; Arunsi, U.O.; Oyelere, A.K. Apigeninidin-rich Sorghum bicolor (L. Moench) extracts suppress A549 cells proliferation and ameliorate toxicity of aflatoxin B1-mediated liver and kidney derangement in rats. Sci Rep 2022, 12, 7438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringelhan, M.; McKeating, J.A.; Protzer, U. Viral hepatitis and liver cancer. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 2017, 372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Péneau, C.; Zucman-Rossi, J.; Nault, J.C. Genomics of Viral Hepatitis-Associated Liver Tumors. J Clin Med 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Devarbhavi, H.; Asrani, S.K.; Arab, J.P.; Nartey, Y.A.; Pose, E.; Kamath, P.S. Global burden of liver disease: 2023 update. J Hepatol 2023, 79, 516–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Global hepatitis report 2024: action for access in low- and middle-income countries; ISBN 978-92-4-009167-2 World Health Organization, Geneva., 2024. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240091672.

- Lemoine, M.; Eholié, S.; Lacombe, K. Reducing the neglected burden of viral hepatitis in Africa: strategies for a global approach. J Hepatol 2015, 62, 469–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ondigui, J.L.N.; Kenmoe, S.; Kengne-Ndé, C.; Ebogo-Belobo, J.T.; Takuissu, G.R.; Kenfack-Momo, R.; Mbaga, D.S.; Tchatchouang, S.; Kenfack-Zanguim, J.; Fogang, R.L.; et al. Epidemiology of occult hepatitis B and C in Africa: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Infect Public Health 2022, 15, 1436–1445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lekskulchai, V. Prevalence of Hepatitis B and C Virus Infections: Influence of National Health Care Policies and Local Clinical Practices. Med Sci Monit Basic Res 2021, 27, e933692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adane, T.; Getawa, S. The prevalence and associated factors of hepatitis B and C virus in hemodialysis patients in Africa: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 2021, 16, e0251570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girmay, G.; Bewket, G.; Amare, A.; Angelo, A.A.; Wondmagegn, Y.M.; Setegn, A.; Wubete, M.; Assefa, M. Seroprevalence of viral hepatitis B and C infections among healthcare workers in Ethiopia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 2024, 19, e0312959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonderup, M.W.; Afihene, M.; Ally, R.; Apica, B.; Awuku, Y.; Cunha, L.; Dusheiko, G.; Gogela, N.; Lohouès-Kouacou, M.J.; Lam, P.; et al. Hepatitis C in sub-Saharan Africa: the current status and recommendations for achieving elimination by 2030. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol 2017, 2, 910–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odoom, A.; Boamah, I.; Sagoe, K.W.C.; Kotey, F.C.N.; Donkor, E.S. Zoonotic and Food-Related Hazards Due to Hepatitis A and E in Africa: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Environmental Health Insights 2024, 18, 11786302241299370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhagwandin, K.; Thaver-Kleitman, J.; Subramoney, K.; Manamela, M.J.; Prabdial-Sing, N. Exploring the Epidemiological Surveillance of Hepatitis A in South Africa: A 2023 Perspective. Viruses 2024, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bane, A.; Sultan, A.; Ahmed, R. Increasing Burden of Acute Hepatitis A among Ethiopian Children, Adolescents, and Young adults: A Change in Epidemiological Pattern and Need for Hepatitis A Vaccine. Ethiop J Health Sci 2022, 32, 255–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stockdale, A.J.; Chaponda, M.; Beloukas, A.; Phillips, R.O.; Matthews, P.C.; Papadimitropoulos, A.; King, S.; Bonnett, L.; Geretti, A.M. Prevalence of hepatitis D virus infection in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Glob Health 2017, 5, e992–e1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tuaillon, E.; Kania, D.; Gordien, E.; Van de Perre, P.; Dujols, P. Epidemiological data for hepatitis D in Africa. Lancet Glob Health 2018, 6, e33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaquet, A.; Muula, G.; Ekouevi, D.K.; Wandeler, G. Elimination of Viral Hepatitis in Low and Middle-Income Countries: Epidemiological Research Gaps. Curr Epidemiol Rep 2021, 8, 89–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonderup, M.W.; Spearman, C.W. Global Disparities in Hepatitis B Elimination-A Focus on Africa. Viruses 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemoine, M.; Eholié, S.; Lacombe, K. Reducing the neglected burden of viral hepatitis in Africa: Strategies for a global approach. Journal of Hepatology 2015, 62, 469–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobsen, K.; Koopman, J. The effects of socioeconomic development on worldwide hepatitis A virus seroprevalence patterns. International Journal of Epidemiology 2005, 34, 600–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koroglu, M.; Jacobsen, K.H.; Demiray, T.; Ozbek, A.; Erkorkmaz, U.; Altindis, M. Socioeconomic indicators are strong predictors of hepatitis A seroprevalence rates in the Middle East and North Africa. Journal of Infection and Public Health 2017, 10, 513–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chattu, V.K.; Knight, W.A.; Adisesh, A.; Yaya, S.; Reddy, K.S.; Di Ruggiero, E.; Aginam, O.; Aslanyan, G.; Clarke, M.; Massoud, M.R.; et al. Politics of disease control in Africa and the critical role of global health diplomacy: A systematic review. Health Promot Perspect 2021, 11, 20–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, C.T.; Kalu, K. The political economy of health policy in Sub-Saharan Africa. Med Law 2008, 27, 29–51. [Google Scholar]

- Ikobah, J.M.; Okpara, H.C.; Ekanem, E.E.; Udo, J.J. Seroprevalence and predictors of hepatitis A infection in Nigerian children. Pan Afr Med J 2015, 20, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ifeorah, I.; Bakarey, A.; Adeniji, J.; Onyemelukwe, F. Seroprevalence of hepatitis B and delta viruses among HIV-infected population attending anti-retroviral clinic in selected health facilities in Abuja, Nigeria. Journal of Immunoassay and Immunochemistry 2017, 38, 608–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fakunle, Y.M.; Abdurrahman, M.B.; Whittle, H.C. Hepatitis-B virus infection in children and adults in Northern Nigeria: a preliminary survey. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 1981, 75, 626–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belo, A.C. Prevalence of hepatitis B virus markers in surgeons in Lagos, Nigeria. East Afr Med J 2000, 77, 283–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adedeji, A.; Nnaji, I.; Muhammad, F.; Amaza, R.; Adewusi, A.; Ojo, J.; Ojenya, E.; Mustapha, A.; Gassi, S.; Klink, P.; et al. Seroprevalence patterns of viral hepatitis B, C, and E among internally displaced persons in Borno State, Nigeria. IJID Reg 2024, 13, 100481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ola, S.O.; Odaibo, G.N.; Olaleye, O.D.; Ayoola, E.A. Hepatitis B and E viral infections among Nigerian healthcare workers. Afr J Med Med Sci 2012, 41, 387–391. [Google Scholar]

- Junaid, S.A.; Agina, S.E.; Abubakar, K.A. Epidemiology and Associated Risk Factors of Hepatitis E Virus Infection in Plateau State, Nigeria. Virology 2014, 5, VRT.S15422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melnick, J.L.; Howard, C.R. Classification and Taxonomy of Hepatitis Viruses: Summary of a Workshop. Tokyo, 1994; pp. 47-49.

- Usuda, D.; Kaneoka, Y.; Ono, R.; Kato, M.; Sugawara, Y.; Shimizu, R.; Inami, T.; Nakajima, E.; Tsuge, S.; Sakurai, R.; et al. Current perspectives of viral hepatitis. World J Gastroenterol 2024, 30, 2402–2417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemes, K.; Persson, S.; Simonsson, M. Hepatitis A Virus and Hepatitis E Virus as Food- and Waterborne Pathogens-Transmission Routes and Methods for Detection in Food. Viruses 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pintilie, H.; Brook, G. Commentary: A review of risk of hepatitis B and C transmission through biting or spitting. J Viral Hepat 2018, 25, 1423–1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerlich, W.H. [Hepatitis B and C. Risk of transmission from infected health care workers to patients]. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz 2004, 47, 369–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lappalainen, M.; Chen, R.W.; Maunula, L.; von Bonsdorff, C.; Plyusnin, A.; Vaheri, A. Molecular epidemiology of viral pathogens and tracing of transmission routes: hepatitis-, calici- and hantaviruses. J Clin Virol 2001, 21, 177–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Ren, J.; Gao, Q.; Hu, Z.; Sun, Y.; Li, X.; Rowlands, D.J.; Yin, W.; Wang, J.; Stuart, D.I.; et al. Hepatitis A virus and the origins of picornaviruses. Nature 2015, 517, 85–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirai-Yuki, A.; Hensley, L.; Whitmire, J.K.; Lemon, S.M. Biliary Secretion of Quasi-Enveloped Human Hepatitis A Virus. mBio 2016, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najarian, R.; Caput, D.; Gee, W.; Potter, S.J.; Renard, A.; Merryweather, J.; Van Nest, G.; Dina, D. Primary structure and gene organization of human hepatitis A virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1985, 82, 2627–2631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegl, G.; Weitz, M.; Kronauer, G. Stability of hepatitis A virus. Intervirology 1984, 22, 218–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramsay, C.N.; Upton, P.A. HEPATITIS A AND FROZEN RASPBERRIES. The Lancet 1989, 333, 43–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costafreda, M.I.; Pérez-Rodriguez, F.J.; D'Andrea, L.; Guix, S.; Ribes, E.; Bosch, A.; Pintó, R.M. Hepatitis A virus adaptation to cellular shutoff is driven by dynamic adjustments of codon usage and results in the selection of populations with altered capsids. J Virol 2014, 88, 5029–5041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tjon, G.M.; Coutinho, R.A.; van den Hoek, A.; Esman, S.; Wijkmans, C.J.; Hoebe, C.J.; Wolters, B.; Swaan, C.; Geskus, R.B.; Dukers, N.; et al. High and persistent excretion of hepatitis A virus in immunocompetent patients. J Med Virol 2006, 78, 1398–1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Severi, E.; Verhoef, L.; Thornton, L.; Guzman-Herrador, B.R.; Faber, M.; Sundqvist, L.; Rimhanen-Finne, R.; Roque-Afonso, A.M.; Ngui, S.L.; Allerberger, F.; et al. Large and prolonged food-borne multistate hepatitis A outbreak in Europe associated with consumption of frozen berries, 2013 to 2014. Euro Surveill 2015, 20, 21192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Cola, G.; Fantilli, A.C.; Pisano, M.B.; Ré, V.E. Foodborne transmission of hepatitis A and hepatitis E viruses: A literature review. Int J Food Microbiol 2021, 338, 108986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Migueres, M.; Lhomme, S.; Izopet, J. Hepatitis A: Epidemiology, High-Risk Groups, Prevention and Research on Antiviral Treatment. Viruses 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, S.G.; Leon, L.A.; Alves, G.; Brito, S.M.; Sandes Vde, S.; Lima, M.M.; Nogueira, M.C.; Tavares Rde, C.; Dobbin, J.; Apa, A.; et al. A Rare Case of Transfusion Transmission of Hepatitis A Virus to Two Patients with Haematological Disease. Transfus Med Hemother 2016, 43, 137–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health, O. WHO immunological basis for immunization series: module 18: hepatitis A; World Health Organization: Geneva, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, D.Y.; Li, J.M.; Lin, S.; Dong, X.; You, J.; Xing, Q.Q.; Ren, Y.D.; Chen, W.M.; Cai, Y.Y.; Fang, K.; et al. Global burden of acute viral hepatitis and its association with socioeconomic development status, 1990-2019. J Hepatol 2021, 75, 547–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Shi, O.; Zhang, T.; Jin, L.; Chen, X. Disease burden of viral hepatitis A, B, C and E: A systematic analysis. J Viral Hepat 2020, 27, 1284–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobsen, K.H. Globalization and the Changing Epidemiology of Hepatitis A Virus. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 2018, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.Y.; Chae, S.J.; Cho, S.R.; Choi, W.; Kim, C.K.; Han, M.G. Nationwide seroprevalence of hepatitis A in South Korea from 2009 to 2019. PLoS One 2021, 16, e0245162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sule, W.F.; Kajogbola, A.T.; Adewumi, M.O. High prevalence of anti-hepatitis A virus immunoglobulin G antibody among healthcare facility attendees in Osogbo, Nigeria. J Immunoassay Immunochem 2013, 34, 75–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Afegbua, S.L.; Bugaje, M.A.; Ahmad, A.A. Seroprevalence of hepatitis A virus infection among schoolchildren and adolescents in Kaduna, Nigeria. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 2013, 107, 627–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogefere, H.O.; Egbe, C.A. Seroprevalence of IgM antibodies to hepatitis A virus in at-risk group in Benin City, Nigeria. Libyan J Med 2016, 11, 31290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ott, J.J.; Stevens, G.A.; Groeger, J.; Wiersma, S.T. Global epidemiology of hepatitis B virus infection: new estimates of age-specific HBsAg seroprevalence and endemicity. Vaccine 2012, 30, 2212–2219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portilho, M.M.; Martins, P.P.; Lampe, E.; Villar, L.M. A comparison of molecular methods for hepatitis B virus (HBV) DNA detection from oral fluid samples. J Med Microbiol 2012, 61, 844–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zenebe, Y.; Mulu, W.; Yimer, M.; Abera, B. Sero-prevalence and risk factors of hepatitis B virus and human immunodeficiency virus infection among pregnant women in Bahir Dar city, Northwest Ethiopia: a cross sectional study. BMC Infect Dis 2014, 14, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, R.X.; Seto, W.K.; Lai, C.L.; Yuen, M.F. Epidemiology of Hepatocellular Carcinoma in the Asia-Pacific Region. Gut Liver 2016, 10, 332–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sadoh, A.E.; Ofili, A. Hepatitis B infection among Nigerian children admitted to a children's emergency room. Afr Health Sci 2014, 14, 377–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eke, A.C.; Eke, U.A.; Okafor, C.I.; Ezebialu, I.U.; Ogbuagu, C. Prevalence, correlates and pattern of hepatitis B surface antigen in a low resource setting. Virol J 2011, 8, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aba, H.O.; Aminu, M. Seroprevalence of hepatitis B virus serological markers among pregnant Nigerian women. Ann Afr Med 2016, 15, 20–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iloh, G.U.; Ikwudinma, A.O. Sero-epidemiology of Hepatitis B Surface Antigenaemia among Adult Nigerians with Clinical Features of Liver Diseases Attending a Primary-Care Clinic in a Resource-Constrained Setting of Eastern Nigeria. N Am J Med Sci 2013, 5, 293–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bada, A.S.; Olatunji, P.O.; Adewuyi, J.O.; Iseniyi, J.O.; Onile, B.A. Hepatitis B surface antigenaemia in Ilorin, Kwara State, Nigeria. Cent Afr J Med 1996, 42, 139–141. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Em, M.; Enenebeaku, M.; Okopi, J.A.; Damen, J. Hepatitis B Virus (HBV) Infection among Pregnant Women in Makurdi, Nigeria. African Journal of Biomedical Research 2010, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lesi, O.A.; Kehinde, M.O.; Omilabu, S.A. Prevalence of the Hepatitis B “e” Antigen in Nigerian Patients with Chronic Liver Disease. Nigerian Quarterly Journal of Hospital Medicine 2008. [CrossRef]

- Rabiu, K.A.; Akinola, O.I.; Adewunmi, A.A.; Omololu, O.M.; Ojo, T.O. Risk factors for hepatitis B virus infection among pregnant women in Lagos, Nigeria. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2010, 89, 1024–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opaleye, O.; Saheed, S.; Familua, F.; Olowe, A.; Ojurongbe, O.; Bolaji, O.; Odewale, G.; Ojo, J. Seroprevalence of Hepatitis B Surface Antigen and Antibody among Pregnant Women Attending a Tertiary Health Institution in Southwestern Nigeria. IOSR Journal of Dental and Medical Sciences 2014, 13, 67–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shittu, M.; Ajao, K.; Adeniji, T.; Awe, C. Seroprevalence of Hepatitis B Surface Antigenemia and Hepatitis C Virus among Intending Blood Donors at Mother and Child Hospital, Akure, Nigeria. International Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences 2014, 47, 2051–5731. [Google Scholar]

- Okonko, I.; Fa, S.; Ta, A.; Augustine, U.; Adeolu, A.; Ojezele, M.; Nwanze, J.; Fadeyi, A. Seroprevalence of HBsAg among patients in Abeokuta, South Western Nigeria. Global Journal of Medical Research 2010, Okonko IO, Soleye FA, Amusan TA, Udeze AO, Alli JA, Ojezele MO, Nwanze JC, Fadeyi A. 2010. Seroprevalence of HBsAg among patients in Abeokuta, South Western Nigeria. Global Journal of Medical Research 10(2): 40-49, 40-49.

- Anaedobe, C.G.; Fowotade, A.; Omoruyi, C.E.; Bakare, R.A. Prevalence, sociodemographic features and risk factors of Hepatitis B virus infection among pregnant women in Southwestern Nigeria. Pan Afr Med J 2015, 20, 406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikeako, L.; Ezegwui, H.; Ajah, L.; Dim, C.; Okeke, T. Seroprevalence of Human Immunodeficiency Virus, Hepatitis B, Hepatitis C, Syphilis and Co-infections among Antenatal Women in a Tertiary Institution in South-East Nigeria. Ann Med Health Sci Res 2014, 4, S259–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chima, C.; Opara, D.; Ahiara, J.; Obeagu, C.; Nwosu, D.; Opara, U.; Dike-Ndudim, J.; Ahiara, C.; Obeagu, E. STUDIES ON HEPATITIS B VIRUS INFECTION IN EBONYI STATE NIGERIA USING HBSAG AS MARKERS: RAPID ASSESSMENT SURVEY. 2022, 2, 185-203.

- Onwuakor, C.; V. C, E.; Nwankwo, I.; J.O, I. Sero-prevalence of Hepatitis B Surface Antigen (HBsAg) amongst Pregnant Women Attending Antenatal Clinic at the Federal Medical Centre Umuahia, Abia State, Nigeria. American Journal of Public Health Research 2014, 2, 255–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awanye, A.M.; Stanley, C.N.; Orji, P.C.; Sasovworho, S.; Okonko, I.O.; Ibezi, C.N.E. Seroprevalence of hepatitis B virus surface antigens and antibodies among healthcare workers in selected hospitals in Rivers State, Nigeria. West African Journal of Pharmacy (2023, 34 132 - 149. [CrossRef]

- Utoo, B.T. Hepatitis B surface antigenemia (HBsAg) among pregnant women in southern Nigeria. Afr Health Sci 2013, 13, 1139–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osazuwa, F.; Erhumwunseimade, P. LETTER TO THE EDITOR REMUNERATED OR NON-REMUNERATED BLOOD DONATION: HOW DO WE ENSURE THE SAFETY OF BLOOD IN NIGERIA? 2013, 1-2. [CrossRef]

- Terwase, J.M.; Emeka, C.K. Prevalence of Hepatitis B Surface Antigen among Residents of Julius Berger Staff Quarters, Kubwa, Abuja. 2015.

- Atilola, G.; Tomisin, O.; Randle, M.; Isaac, K.O.; Odutolu, G.; Olomu, J.; Adenuga, L. Epidemiology of HBV in Pregnant Women, South West Nigeria. J Epidemiol Glob Health 2018, 8, 115–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okonko, I.; Sule, W.; Ebute, A.J.; Donbraye, E.; Fadeyi, A.; Augustine, U.; lli, J.A. Farming and Non-Farming Individuals Attending Grimard Catholic Hospital, Anyigba, Kogi State, Nigeria Were Comparable in Hepatitis B Surface Antigen Seroprevalence. Current Research Journal of Biological Sciences 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Osasona, O.; Ariyo, O.; Ariyo, E.; Oguzie, J.; Olumade, T.; George, U.; Adewale-Fasoro, O.; Oguntoye, O. Comparative serologic profiles of hepatitis B Virus (HBV) between HIV/HBV co-infected and Hbv mono-infected patients in Ile-Ife, Nigeria. Journal of Immunoassay and Immunochemistry 2020, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forbi, J.C.; Onyemauwa, N.; Gyar, S.D.; Oyeleye, A.O.; Entonu, P.; Agwale, S.M. High prevalence of hepatitis B virus among female sex workers in Nigeria. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo 2008, 50, 219–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olusayo, A.; Okwori, E.E.; Egwu, C.; Audu, F. Seroprevalence of hepatitis B surface antigen among prospective blood donors in an urban area of Benue State. Internet Journal of Hematology 2009, 5. [Google Scholar]

- Aminu, M.; Md, V. HEPATITIS B INFECTION IN NIGERIA: A REVIEW; 2014.

- Saidu, A.; Salihu, Y.; Umar, A.A.; Muhammad, B.; Abdullahi, I.N. Seroprevalence of Hepatitis B Surface Antigen among Pregnant Women Attending Ante-Natal Clinics in Sokoto Metropolis. 2015.

- Ndako, J.; Yahaya, A.; Amira, J.; Olaolu, T.; Adelani-Akande, T. Hepatitis B Virus (HBV) Infection among Alcoholic Consumers at a Local Community, North-East Nigeria. The Journal of Natural Science, Biology and Medicine 2013, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Imarenezor, N.; Brown, S.; Yakubu, O.; Soken, D. Survey of Hepatitis B and C among students of Federal. 2016.

- Aliyu, B.; Alhaji Isa, M.; Gulumbe, B. Prevalence of Hepatitis B virus infection among children attending mohammed shuwa memorial hospital Maiduguri, Borno state, Nigeria. 2020.

- Okoye, I.; Samba, S. Sero-Epidemic Survey Of Hepatitis B In A Population Of Northern Nigeria. Animal Research International 2008, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Ishaq, A.; Mohammed, F. Prevalence of HepaTitis B Surface Antigen Among Blood Donors and Patients Attending General Hospital Potiskum. Ext J App Sci. 2015, 3, 199–203. [Google Scholar]

- Schillie, S.; Wester, C.; Osborne, M.; Wesolowski, L.; Ryerson, A.B. CDC Recommendations for Hepatitis C Screening Among Adults - United States, 2020. MMWR Recomm Rep 2020, 69, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Te, H.S.; Jensen, D.M. Epidemiology of hepatitis B and C viruses: a global overview. Clin Liver Dis 2010, 14, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sy, T.; Jamal, M.M. Epidemiology of hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection. Int J Med Sci 2006, 3, 41–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madhava, V.; Burgess, C.; Drucker, E. Epidemiology of chronic hepatitis C virus infection in sub-Saharan Africa. Lancet Infect Dis 2002, 2, 293–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maheshwari, A.; Thuluvath, P.J. Management of acute hepatitis C. Clin Liver Dis 2010, 14, 169–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, X.; Luo, J.; Bai, J.; Yu, R. Epidemiology of hepatitis C virus infection among injection drug users in China: systematic review and meta-analysis. Public Health 2008, 122, 990–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tohme, R.A.; Holmberg, S.D. Is sexual contact a major mode of hepatitis C virus transmission? Hepatology 2010, 52, 1497–1505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafari, S.; Copes, R.; Baharlou, S.; Etminan, M.; Buxton, J. Tattooing and the risk of transmission of hepatitis C: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Infect Dis 2010, 14, e928–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owusu-Ofori, S.; Temple, J.; Sarkodie, F.; Anokwa, M.; Candotti, D.; Allain, J.P. Predonation screening of blood donors with rapid tests: implementation and efficacy of a novel approach to blood safety in resource-poor settings. Transfusion 2005, 45, 133–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, N.C.; Gotsch, P.B.; Langan, R.C. Caring for pregnant women and newborns with hepatitis B or C. Am Fam Physician 2010, 82, 1225–1229. [Google Scholar]

- Jeannel, D.; Fretz, C.; Traore, Y.; Kohdjo, N.; Bigot, A.; E, P.G.; Jourdan, G.; Kourouma, K.; Maertens, G.; Fumoux, F.; et al. Evidence for high genetic diversity and long-term endemicity of hepatitis C virus genotypes 1 and 2 in West Africa. J Med Virol 1998, 55, 92–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ejele, O.A.; Nwauche, C.A.; Erhabor, O. Seroprevalence of hepatitis C virus in the Niger Delta of Nigeria. Niger Postgrad Med J 2006, 13, 103–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Urban, S.; Neumann-Haefelin, C.; Lampertico, P. Hepatitis D virus in 2021: virology, immunology and new treatment approaches for a difficult-to-treat disease. Gut 2021, 70, 1782–1794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores, R.; Owens, R.A.; Taylor, J. Pathogenesis by subviral agents: viroids and hepatitis delta virus. Current Opinion in Virology 2016, 17, 87–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.G.; Lemon, S.M. Hepatitis delta virus antigen forms dimers and multimeric complexes in vivo. J Virol 1993, 67, 446–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Japhet, O.A.A.M.O. Hepatitis Delta Virus in Patients Referred for Malaria Parasite Test in Ile-Ife, Nigeria. Methodology 2017, 36. [Google Scholar]

- Akande, K.O.; Adeola, F.; and Adekanmbi, O. The effect of Hepatitis D co-infection on the immunologic and molecular profile of Hepatitis B in asymptomatic Chronic Hepatitis B patients in southwest Nigeria. Journal of Immunoassay and Immunochemistry 2020, 41, 272–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulkareem, L.O.; Ndububa, D.A.; Uhunmwangho, A.O.; Yunusa, T. Hepatitis D virus antibodies and liver function profile among patients with chronic hepatitis B infection in Abuja, Nigeria. J Infect Dev Ctries 2021, 15, 141–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbaawuaga, E.M.; Iroegbu, C.U.; Ike, A.C. Hepatitis B virus (HBV) serological patterns in Benue State, Nigeria. Open Journal of Medical Microbiology 2014, 4, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waiya, S.; Taura, D.; Shehu, A.; Yahaya, S.; Ali, M.; Garba, M. Prevalence of hepatitis D virus antigens among sero-positive hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) patients attending Aminu Kano teaching hospital (AKTH), Kano. Arch Immunol Allergy 2018, 1, 67–74. [Google Scholar]

- Inyang-Etoh, P.C.; Obi, O.A.; Udonkang, M.I. Prevalence of hepatitis B, C, and D among patients on highly active antiretroviral drug therapy (HAART) in calabar metropolis, Nigeria. Journal of Medical and Allied Science 2018, 8, 17–22. [Google Scholar]

- Egbebi, A.; Okiki, P.; Oyinloye, J.; Daramola, G.; Ogunfolakan, O. Prevalence of Hepatitis B and D Antibodies Among Pregnant Women Attending Antenatal Clinic at Ekiti State University Teaching Hospital, Ado-Ekiti, Ekiti State, Nigeria. J. Adv. Microbiol 2022, 22, 97–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ifeorah, I.M.; Gerber, A.; Dziri, S.; Bakarey, S.A.; Le Gal, F.; Aglavdawa, G.; Alloui, C.; Kalu, S.O.; Ghapouen, P.-A.B.; Brichler, S. The prevalence and molecular epidemiology of hepatitis delta virus in Nigeria: The results of a nationwide study. Viruses 2024, 16, 1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nwokediuko, S.; Ijeoma, U. Seroprevalence of antibody to HDV in Nigerians with hepatitis B virus-related liver diseases. Nigerian Journal of Clinical Practice 2009, 12. [Google Scholar]

- Okonkwo, U.C.; Okpara, H.C.; Inaku, K.; Aluka, T.M.; Chukwudike, E.S.; Ogarekpe, Y.; Emin, E.J.; Hodo, O.; Otu, A.A. Prevalence and risk factors of Hepatitis D virus antibody among asymptomatic carriers of Hepatitis B virus: a community survey. African Health Sciences 2022, 22, 504–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nwika, G.N.; Awortu, J.Z.; Mgbeoma, E.E. Prevalence of hepatitis D virus among hepatitis B positive blood donors in Port Harcourt, Nigeria. Int. Blood Res. Rev 2023, 14, 48–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okpokam, D.; Kooffreh-Ada, M.; Okhormhe, Z.; Akpabio, E.; Akpotuzor, J.; Nna, V. Hepatitis D virus in chronic liver disease patients with hepatitis B surface antigen in University of Calabar Teaching Hospital, Calabar, Nigeria. 2015.

- Anejo-Okopi, J.; Okpara, J.; Dabol, J.; Adetunji, J.; Adeniyi, D.; Amanyi, D.; Ujah, O.; David, V.; Omaiye, P.; Audu, O. Hepatitis delta virus infection among HIV/HBV and HBV-mono infected patients in Jos, Nigeria. Hosts Viruses 2021, 8, 23–28. [Google Scholar]

- Opaleye, O.O.; Japhet, O.M.; Adewumi, O.M.; Omoruyi, E.C.; Akanbi, O.A.; Oluremi, A.S.; Wang, B.; Tong, H.v.; Velavan, T.P.; Bock, C.-T. Molecular epidemiology of hepatitis D virus circulating in Southwestern Nigeria. Virology Journal 2016, 13, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- feorah, I.; Bakarey, A.; Adeniji, J.; Onyemelukwe, F. Hepatitis C and delta viruses among HBV positive cohort in Abuja Nigeria. 2019.

- Abdulkareem, L.O.; Ndububa, D.A.; Uhunmwangho, A.O.; Yunusa, T. Hepatitis D virus antibodies and liver function profile among patients with chronic hepatitis B infection in Abuja, Nigeria. The Journal of Infection in Developing Countries 2021, 15, 141–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, G.W.; Dalton, H.R. Hepatitis E: an underestimated emerging threat. Ther Adv Infect Dis 2019, 6, 2049936119837162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nimgaonkar, I.; Ding, Q.; Schwartz, R.E.; Ploss, A. Hepatitis E virus: advances and challenges. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2018, 15, 96–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Das, A.; Rivera-Serrano, E.E.; Yin, X.; Walker, C.M.; Feng, Z.; Lemon, S.M. Cell entry and release of quasi-enveloped human hepatitis viruses. Nature Reviews Microbiology 2023, 21, 573–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, X.; Feng, G. Hepatitis E Virus Entry. Viruses 2019, 11, 883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purdy, M.A.; Harrison, T.J.; Jameel, S.; Meng, X.-J.; Okamoto, H.; Van der Poel, W.H.M.; Smith, D.B.; Consortium, I.R. ICTV Virus Taxonomy Profile: Hepeviridae. Journal of General Virology 2017, 98, 2645–2646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, G.H.; Tan, B.H.; Teo, E.C.; Lim, S.G.; Dan, Y.Y.; Wee, A.; Aw, P.P.; Zhu, Y.; Hibberd, M.L.; Tan, C.K.; et al. Chronic Infection With Camelid Hepatitis E Virus in a Liver Transplant Recipient Who Regularly Consumes Camel Meat and Milk. Gastroenterology 2016, 150, 355–357.e353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nelson, K.E.; Labrique, A.B.; Kmush, B.L. Epidemiology of Genotype 1 and 2 Hepatitis E Virus Infections. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 2019, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Akanbi, O.A.; Harms, D.; Adesina, O.; Osundare, F.A.; Naidoo, D.; Deveaux, I.; Ogundiran, O.; Ugochukwu, U.; Mba, N.; et al. A new hepatitis E virus genotype 2 strain identified from an outbreak in Nigeria, 2017. Virology Journal 2018, 15, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buisson, Y.; Grandadam, M.; Nicand, E.; Cheval, P.; van Cuyck-Gandre, H.; Innis, B.; Rehel, P.; Coursaget, P.; Teyssou, R.; Tsarev, S. Identification of a novel hepatitis E virus in Nigeria. J Gen Virol 2000, 81, 903–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osundare, F.A.; Klink, P.; Majer, C.; Akanbi, O.A.; Wang, B.; Faber, M.; Harms, D.; Bock, C.-T.; Opaleye, O.O. Hepatitis E Virus Seroprevalence and Associated Risk Factors in Apparently Healthy Individuals from Osun State, Nigeria. Pathogens 2020, 9, 392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adesina, O.; Japhet, M.; Donbraye, E.; Kumapayi, T.; Kudoro, A. Anti hepatitis E virus antibodies in sick and healthy Individuals in Ekiti State, Nigeria. African Journal of Microbiology Research 2009, 3, 533–536. [Google Scholar]

- Tu, A.; Zhu, X.; Dastjerdi, P.Z.; Yin, Y.; Peng, M.; Zheng, D.; Peng, Z.; Wang, E.; Wang, X.; Jing, W. Evaluate the clinical efficacy of traditional Chinese Medicine as the neoadjuvant treatment in reducing the incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with hepatitis B-related cirrhosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Heliyon 2024, 10, e24437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, F.; Yang, Y.; Bai, Z.; Si, L.; Wang, X.; Yu, J.; Xiao, X.; Liu, Y.; Ren, Z. The role of Traditional Chinese medicine in anti-HBV: background, progress, and challenges. Chin Med 2023, 18, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demie, G.; Negash, M.; Awas, T. Ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants used by indigenous people in and around Dirre Sheikh Hussein heritage site of South-eastern Ethiopia. J Ethnopharmacol 2018, 220, 87–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aschale, Y.; Wubetu, M.; Abebaw, A.; Yirga, T.; Minwuyelet, A.; Toru, M. A Systematic Review on Traditional Medicinal Plants Used for the Treatment of Viral and Fungal Infections in Ethiopia. J Exp Pharmacol 2021, 13, 807–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaudhary, A.N.; Arif, A.M; Shafi B., S; Kushwaha A. S., P; P, S.A. Emerging role of natural bioactive compounds in navigating the future of liver disease. iLIVER 2025, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arunsi, U.O.; Chioma, O.E.; Etusim, P.E.; Owumi, S.E. Indigenous Nigeria medicinal herbal remedies: A potential source for therapeutic against rheumatoid arthritis. Experimental Biology and Medicine 2022, 247, 1148–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, A.; Datta, S. Medicinal Plants against Ischemic Stroke. Curr Pharm Biotechnol 2021, 22, 1302–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, A.; Roy, M.; Gacem, A.; Datta, S.; Zeyaullah, M.; Muzammil, K.; Farghaly, T.A.; Abdellattif, M.H.; Yadav, K.K.; Simal-Gandara, J. Role of bioactive compounds in the treatment of hepatitis: A review. Front Pharmacol 2022, 13, 1051751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhazmi, H.A.; Najmi, A.; Javed, S.A.; Sultana, S.; Al Bratty, M.; Makeen, H.A.; Meraya, A.M.; Ahsan, W.; Mohan, S.; Taha, M.M.E.; et al. Medicinal Plants and Isolated Molecules Demonstrating Immunomodulation Activity as Potential Alternative Therapies for Viral Diseases Including COVID-19. Front Immunol 2021, 12, 637553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagunas-Rangel, F.A.; Bermudez-Cruz, R.M. Natural Compounds That Target DNA Repair Pathways and Their Therapeutic Potential to Counteract Cancer Cells. Front Oncol 2020, 10, 598174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beykaso, G.; Teklehaymanot, T.; Mulu, A.; Berhe, N.; Alemayehu, D.H.; Giday, M. Medicinal Plants in Treating Hepatitis B Among Communities of Central Region of Ethiopia. Hepat Med 2023, 15, 265–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malik, Z.A.; Bhat, J.A.; Ballabha, R.; Bussmann, R.W.; Bhatt, A.B. Ethnomedicinal plants traditionally used in health care practices by inhabitants of Western Himalaya. J Ethnopharmacol 2015, 172, 133–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ntemafack, A.; Ayoub, M.; Hassan, Q.p.; Gandhi, S.G. A systematic review of pharmacological potential of phytochemicals from Rumex abyssinicus Jacq. S Afr J Bot 2023, 154, 11–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilyas, U.; Katare, D.P.; Aeri, V.; Naseef, P.P. A Review on Hepatoprotective and Immunomodulatory Herbal Plants. Pharmacogn Rev 2016, 10, 66–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freitag, A.F.; Cardia, G.F.; da Rocha, B.A.; Aguiar, R.P.; Silva-Comar, F.M.; Spironello, R.A.; Grespan, R.; Caparroz-Assef, S.M.; Bersani-Amado, C.A.; Cuman, R.K. Hepatoprotective Effect of Silymarin (Silybum marianum) on Hepatotoxicity Induced by Acetaminophen in Spontaneously Hypertensive Rats. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2015, 2015, 538317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valenzuela, A.; Garrido, A. Biochemical bases of the pharmacological action of the flavonoid silymarin and of its structural isomer silibinin. Biol Res 1994, 27, 105–112. [Google Scholar]

- Song, Z.; Deaciuc, I.; Song, M.; Lee, D.Y.; Liu, Y.; Ji, X.; McClain, C. Silymarin protects against acute ethanol-induced hepatotoxicity in mice. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2006, 30, 407–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, D.Y.; Jung, Y.S.; Kim, S.J.; Kim, Y.S.; Choi, D.W.; Kim, Y.C. Alterations in sulfur amino acid metabolism in mice treated with silymarin: a novel mechanism of its action involved in enhancement of the antioxidant defense in liver. Planta Med 2013, 79, 997–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javed, S.; Kohli, K.; Ali, M. Reassessing bioavailability of silymarin. Altern Med Rev 2011, 16, 239–249. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, C.; Lu, Y.; Chen, J.; Zhang, W.; Wu, W. Synchronized and sustained release of multiple components in silymarin from erodible glyceryl monostearate matrix system. Eur J Pharm Biopharm 2007, 66, 210–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferenci, P.; Scherzer, T.M.; Kerschner, H.; Rutter, K.; Beinhardt, S.; Hofer, H.; Schoniger-Hekele, M.; Holzmann, H.; Steindl-Munda, P. Silibinin is a potent antiviral agent in patients with chronic hepatitis C not responding to pegylated interferon/ribavirin therapy. Gastroenterology 2008, 135, 1561–1567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tunca, R.; Sozmen, M.; Citil, M.; Karapehlivan, M.; Erginsoy, S.; Yapar, K. Pyridine induction of cytochrome P450 1A1, iNOS and metallothionein in Syrian hamsters and protective effects of silymarin. Exp Toxicol Pathol 2009, 61, 243–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.C.; Hsiang, C.Y.; Wu, S.L.; Ho, T.Y. Identification of novel mechanisms of silymarin on the carbon tetrachloride-induced liver fibrosis in mice by nuclear factor-kappaB bioluminescent imaging-guided transcriptomic analysis. Food Chem Toxicol 2012, 50, 1568–1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gharagozloo, M.; Velardi, E.; Bruscoli, S.; Agostini, M.; Di Sante, M.; Donato, V.; Amirghofran, Z.; Riccardi, C. Silymarin suppress CD4+ T cell activation and proliferation: effects on NF-kappaB activity and IL-2 production. Pharmacol Res 2010, 61, 405–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trappoliere, M.; Caligiuri, A.; Schmid, M.; Bertolani, C.; Failli, P.; Vizzutti, F.; Novo, E.; di Manzano, C.; Marra, F.; Loguercio, C.; et al. Silybin, a component of sylimarin, exerts anti-inflammatory and anti-fibrogenic effects on human hepatic stellate cells. J Hepatol 2009, 50, 1102–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manna, S.K.; Mukhopadhyay, A.; Van, N.T.; Aggarwal, B.B. Silymarin suppresses TNF-induced activation of NF-kappa B, c-Jun N-terminal kinase, and apoptosis. J Immunol 1999, 163, 6800–6809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faulstich, H.; Jahn, W.; Wieland, T. Silybin inhibition of amatoxin uptake in the perfused rat liver. Arzneimittelforschung 1980, 30, 452–454. [Google Scholar]

- El-Bahay, C.; Gerber, E.; Horbach, M.; Tran-Thi, Q.H.; Rohrdanz, E.; Kahl, R. Influence of tumor necrosis factor-alpha and silibin on the cytotoxic action of alpha-amanitin in rat hepatocyte culture. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 1999, 158, 253–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Odedina, S.; Agwai, I.; Ojengbede, O.; Huo, D.; Olopade, O.I. Traditional medicine usage among adult women in Ibadan, Nigeria: a cross-sectional study. BMC Complement Med Ther 2020, 20, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, M.K.; Ara, I.; Mondal, M.S.A.; Kabir, Y. Phytochemistry, pharmacological activity, and potential health benefits of Gly cyrrhiza glabra. Heliyon 2021, 7, e07240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Rossum, T.G.; Vulto, A.G.; de Man, R.A.; Brouwer, J.T.; Schalm, S.W. Review article: glycyrrhizin as a potential treatment for chronic hepatitis C. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 1998, 12, 199–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asl, M.N.; Hosseinzadeh, H. Review of pharmacological effects of Glycyrrhiza sp. and its bioactive compounds. Phytother Res 2008, 22, 709–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kimura, M.; Moro, T.; Motegi, H.; Maruyama, H.; Sekine, M.; Okamoto, H.; Inoue, H.; Sato, T.; Ogihara, M. In vivo glycyrrhizin accelerates liver regeneration and rapidly lowers serum transaminase activities in 70% partially hepatectomized rats. Eur J Pharmacol 2008, 579, 357–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.Y.; Cao, H.Y.; Liu, P.; Cheng, G.H.; Sun, M.Y. Glycyrrhizic acid in the treatment of liver diseases: literature review. Biomed Res Int 2014, 2014, 872139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korenaga, M.; Hidaka, I.; Nishina, S.; Sakai, A.; Shinozaki, A.; Gondo, T.; Furutani, T.; Kawano, H.; Sakaida, I.; Hino, K. A glycyrrhizin-containing preparation reduces hepatic steatosis induced by hepatitis C virus protein and iron in mice. Liver Int 2011, 31, 552–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiki, Y.; Shirai, K.; Saito, Y.; Yoshida, S.; Mori, Y.; Wakashin, M. Effect of glycyrrhizin on lysis of hepatocyte membranes induced by anti-liver cell membrane antibody. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 1992, 7, 12–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abe, Y.; Ueda, T.; Kato, T.; Kohli, Y. [Effectiveness of interferon, glycyrrhizin combination therapy in patients with chronic hepatitis C]. Nihon Rinsho 1994, 52, 1817–1822. [Google Scholar]

- Shaneyfelt, M.E.; Burke, A.D.; Graff, J.W.; Jutila, M.A.; Hardy, M.E. Natural products that reduce rotavirus infectivity identified by a cell-based moderate-throughput screening assay. Virol J 2006, 3, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, J.; Meng, T.; Wang, Y.; Tang, W. A Review of the Antiviral Activities of Glycyrrhizic Acid, Glycyrrhetinic Acid and Glycyrrhetinic Acid Monoglucuronide. Pharmaceuticals (Basel) 2023, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marhaeny, H.D.; Widyawaruyanti, A.; Widiandani, T.; Fuad Hafid, A.; Wahyuni, T.S. Phyllanthin and hypophyllanthin, the isolated compounds of Phyllanthus niruri inhibit protein receptor of corona virus (COVID-19) through in silico approach. J Basic Clin Physiol Pharmacol 2021, 32, 809–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumaran, A. , Karunakaran, R. J. In vitro antioxidant activities of methanol extracts of five Phyllanthus species from India. LWT - Food Science and Technology 2007, 40, 344–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, X.; Wu, L.F.; Guo, H.L.; Chen, W.J.; Cui, Y.P.; Qi, Q.; Li, S.; Liang, W.Y.; Yang, G.H.; Shao, Y.Y.; et al. The Genus Phyllanthus: An Ethnopharmacological, Phytochemical, and Pharmacological Review. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2016, 2016, 7584952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanh, N.D.; Sinchaipanid, N.; Mitrevej, A. Physicochemical characterization of phyllanthin from Phyllanthus amarus Schum. et Thonn. Drug Dev Ind Pharm 2014, 40, 793–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin-Hua, W.; Chang-Qing, L.; Xing-Bo, G.; Lin-Chun, F. A comparative study of Phyllanthus amarus compound and interferon in the treatment of chronic viral hepatitis B. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health 2001, 32, 140–142. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Chirdchupunseree, H.; Pramyothin, P. Protective activity of phyllanthin in ethanol-treated primary culture of rat hepatocytes. J Ethnopharmacol 2010, 128, 172–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ott, M.; Thyagarajan, S.P.; Gupta, S. Phyllanthus amarus suppresses hepatitis B virus by interrupting interactions between HBV enhancer I and cellular transcription factors. Eur J Clin Invest 1997, 27, 908–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Zhao, X.; Li, R.; Wen, X.; Xiu, Y.; Long, M.; Li, J.; Huang, X.; Wen, J.; Dong, X.; et al. The combination of Schisandrin C and Luteolin synergistically attenuates hepatitis B virus infection via repressing HBV replication and promoting cGAS-STING pathway activation in macrophages. Chin Med 2024, 19, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Xu, G.; Hou, X.; Mu, W.; Yang, H.; Shi, W.; Wen, J.; Liu, T.; Wu, Z.; Bai, J.; et al. Schisandrin C enhances cGAS-STING pathway activation and inhibits HBV replication. J Ethnopharmacol 2023, 311, 116427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehambarampillai, D.; Wan, M.L.Y. A comprehensive review of Schisandra chinensis lignans: pharmacokinetics, pharmacological mechanisms, and future prospects in disease prevention and treatment. Chin Med 2025, 20, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donnapee, S.; Li, J.; Yang, X.; Ge, A.H.; Donkor, P.O.; Gao, X.M.; Chang, Y.X. Cuscuta chinensis Lam.: A systematic review on ethnopharmacology, phytochemistry and pharmacology of an important traditional herbal medicine. J Ethnopharmacol 2014, 157, 292–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, S.W. Panax ginseng, Rhodiola rosea and Schisandra chinensis. Int J Food Sci Nutr 2012, 63 Suppl 1, 75–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, H.J.; Ji, S.B.; Kim, S.E.; Lee, G.M.; Park, S.Y.; Wu, Z.; Jang, D.S.; Liu, K.H. Inhibitory Effects of Schisandra Lignans on Cytochrome P450s and Uridine 5'-Diphospho-Glucuronosyl Transferases in Human Liver Microsomes. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yen, F.L.; Wu, T.H.; Lin, L.T.; Lin, C.C. Hepatoprotective and antioxidant effects of Cuscuta chinensis against acetaminophen-induced hepatotoxicity in rats. J Ethnopharmacol 2007, 111, 123–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, B.; Alam, T.; Varshney, M.; Khan, S.A. Hepatoprotective activity of two plants belonging to the Apiaceae and the Euphorbiaceae family. J Ethnopharmacol 2002, 79, 313–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

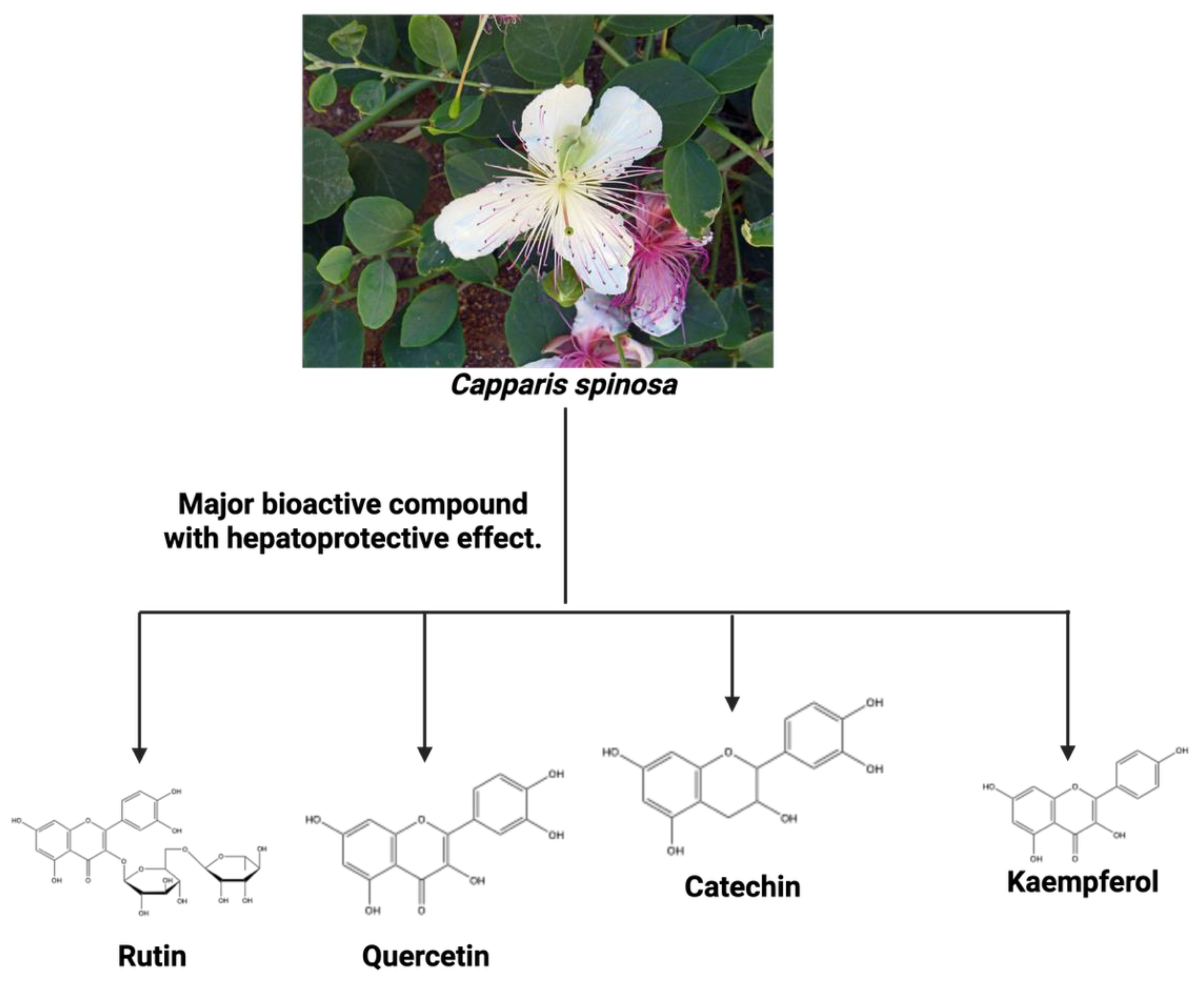

- Tlili, N.; Elfalleh, W.; Saadaoui, E.; Khaldi, A.; Triki, S.; Nasri, N. The caper (Capparis L.): ethnopharmacology, phytochemical and pharmacological properties. Fitoterapia 2011, 82, 93–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mollica Adriano, G.Z. , Marcello Locatelli, Azzurra Stefanu, Andrei Mocan, Giorgia Macedonio, Simone Carradori, Olakunle Onaolapo, Adejoke Onaolapo, Juliet Adegoke, Marufat Olaniyan, Abdurrahman Aktumsek, Ettore Novellino Anti-diabetic and anti-hyperlipidemic properties of Capparis spinosa L.: In vivo and in vitro evaluation of its nutraceutical potential. Journal of Functional Foods 2017, 35, 32–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Ma, Z.F. Phytochemical and Pharmacological Properties of Capparis spinosa as a Medicinal Plant. Nutrients 2018, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleem, H.; Khurshid, U.; Sarfraz, M.; Ahmad, I.; Alamri, A.; Anwar, S.; Alamri, A.S.; Locatelli, M.; Tartaglia, A.; Mahomoodally, M.F.; et al. Investigation into the biological properties, secondary metabolites composition, and toxicity of aerial and root parts of Capparis spinosa L.: An important medicinal food plant. Food Chem Toxicol 2021, 155, 112404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huseini, H.F.; Alavian, S.M.; Heshmat, R.; Heydari, M.R.; Abolmaali, K. The efficacy of Liv-52 on liver cirrhotic patients: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled first approach. Phytomedicine 2005, 12, 619–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Li, Q.; Feng, T.; Li, K. Aqueous extract of Solanum nigrum inhibit growth of cervical carcinoma (U14) via modulating immune response of tumor bearing mice and inducing apoptosis of tumor cells. Fitoterapia 2008, 79, 548–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.P.; Ma, X.; Li, M.M.; Li, Z.; Han, Q.; Li, R.; Li, C.W.; Chang, Y.C.; Zhao, C.W.; Lin, Y.X. Hepatoprotective effects of Solanum nigrum against ethanol-induced injury in primary hepatocytes and mice with analysis of glutathione S-transferase A1. J Chin Med Assoc 2016, 79, 65–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Son, Y.O.; Kim, J.; Lim, J.C.; Chung, Y.; Chung, G.H.; Lee, J.C. Ripe fruit of Solanum nigrum L. inhibits cell growth and induces apoptosis in MCF-7 cells. Food Chem Toxicol 2003, 41, 1421–1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verma, S.K. , Rai, M. K., Asthana, P., Jaiswal, V. S., Jaiswal, U. In vitro plantlets from alginate-encapsulated shoot tips of Solanum nigrum L. In vitro plantlets from alginate-encapsulated shoot tips of Solanum nigrum L. 2010, 124, 517–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prashanth Kumar, V.; Shashidhara, S.; Kumar, M.M.; Sridhara, B.Y. Cytoprotective role of Solanum nigrum against gentamicin-induced kidney cell (Vero cells) damage in vitro. Fitoterapia 2001, 72, 481–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultana, S.; Perwaiz, S.; Iqbal, M.; Athar, M. Crude extracts of hepatoprotective plants, Solanum nigrum and Cichorium intybus inhibit free radical-mediated DNA damage. J Ethnopharmacol 1995, 45, 189–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, H.M.; Tseng, H.C.; Wang, C.J.; Lin, J.J.; Lo, C.W.; Chou, F.P. Hepatoprotective effects of Solanum nigrum Linn extract against CCl(4)-induced oxidative damage in rats. Chem Biol Interact 2008, 171, 283–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javed, T.; Ashfaq, U.A.; Riaz, S.; Rehman, S.; Riazuddin, S. In-vitro antiviral activity of Solanum nigrum against Hepatitis C Virus. Virol J 2011, 8, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akdere, H.; Tastekin, E.; Mericliler, M.; Burgazli, K.M. The protective effects of Ginkgo biloba EGb761 extract against renal ischemia-reperfusion injury in rats. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 2014, 18, 2936–2941. [Google Scholar]

- Kleijnen, J.; Knipschild, P. Ginkgo biloba. Lancet 1992, 340, 1136–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.K.; Srivastav, S.; Castellani, R.J.; Plascencia-Villa, G.; Perry, G. Neuroprotective and Antioxidant Effect of Ginkgo biloba Extract Against AD and Other Neurological Disorders. Neurotherapeutics 2019, 16, 666–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohanta, T.K.; Tamboli, Y.; Zubaidha, P.K. Phytochemical and medicinal importance of Ginkgo biloba L. Nat Prod Res 2014, 28, 746-752. Nat Prod Res 2014, 28, 746–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Birks, J.; Grimley Evans, J. Ginkgo biloba for cognitive impairment and dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2009, CD003120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naik, S.R.; Panda, V.S. Hepatoprotective effect of Ginkgoselect Phytosome in rifampicin induced liver injury in rats: evidence of antioxidant activity. Fitoterapia 2008, 79, 439–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almeleebia, T.M.; Alsayari, A.; Wahab, S. Pharmacological and Clinical Efficacy of Picrorhiza kurroa and Its Secondary Metabolites: A Comprehensive Review. Molecules 2022, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soren, P.; Sharma, R.; Mal, G.; Singh, B.; Kumar, P.; Patil, R.D.; Singh, B. Hepatoprotective activity of Picrorhiza kurroa and Berberis lycium is mediated by inhibition of COX-2 and TGF-β expression in lantadenes-induced sub-chronic toxicity in guinea pigs. Phytomedicine Plus 2022, 2, 100288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, X.; Wang, X.; Tian, M.; Dong, Z.; Wang, J.; Wang, C.; Huang, Q. The role of Andrographolide in the prevention and treatment of liver diseases. Phytomedicine 2023, 109, 154537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sareer, O.; Ahmad, S.; Umar, S. Andrographis paniculata: a critical appraisal of extraction, isolation and quantification of andrographolide and other active constituents. Nat Prod Res 2014, 28, 2081–2101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Ratha, K.K.; Jaiswal, S.; Rao, M.M.; Acharya, R. Exploring the potential of andrographis paniculata and its bioactive compounds in the management of liver diseases: A comprehensive food chemistry perspective. Food Chemistry Advances 2024, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manvar, D.; Mishra, M.; Kumar, S.; Pandey, V.N. Identification and evaluation of anti hepatitis C virus phytochemicals from Eclipta alba. J Ethnopharmacol 2012, 144, 545–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naik, K.S.; Gurushanthaiah, M.; Kavimani, M.; Prabhu, K.; Lokanadham, S. Hepatoprotective Role of Eclipta alba against High Fatty Diet Treated Experimental Models - A Histopathological Study. Maedica (Bucur) 2018, 13, 217–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deenin, W.; Malakul, W.; Boonsong, T.; Phoungpetchara, I.; Tunsophon, S. Papaya improves non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in obese rats by attenuating oxidative stress, inflammation and lipogenic gene expression. World J Hepatol 2021, 13, 315–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung, J.; Kim, N.K.; Park, S.; Shin, H.J.; Hwang, S.G.; Kim, K. Inhibitory effect of Phyllanthus urinaria L. extract on the replication of lamivudine-resistant hepatitis B virus in vitro. BMC Complement Altern Med 2015, 15, 255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slagle, B.L.; Andrisani, O.M.; Bouchard, M.J.; Lee, C.G.; Ou, J.H.; Siddiqui, A. Technical standards for hepatitis B virus X protein (HBx) research. Hepatology 2015, 61, 1416–1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Pandey, A.K. Plant Secondary Metabolites With Hepatoprotective Efficacy. Nutraceuticals and Natural Product Pharmaceuticals 2019, 71–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dikshit, P.; Tyagi, M.K.; Shukla, K.; Sharma, S.; Gambhir, J.K.; Shukla, R. Hepatoprotective effect of stem of Musa sapientum Linn in rats intoxicated with carbon tetrachloride. Ann Hepatol 2011, 10, 333–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batiha, G.E.; Alkazmi, L.M.; Wasef, L.G.; Beshbishy, A.M.; Nadwa, E.H.; Rashwan, E.K. Syzygium aromaticum L. (Myrtaceae): Traditional Uses, Bioactive Chemical Constituents, Pharmacological and Toxicological Activities. Biomolecules 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.; Prasad, R.; Mahmood, A.; Routray, I.; Shinkafi, T.S.; Sahin, K.; Kucuk, O. Eugenol-rich Fraction of Syzygium aromaticum (Clove) Reverses Biochemical and Histopathological Changes in Liver Cirrhosis and Inhibits Hepatic Cell Proliferation. J Cancer Prev 2014, 19, 288–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, C.K.; Kamath, J.V.; Asad, M. Hepatoprotective activity of Psidium guajava Linn. leaf extract. Indian J Exp Biol 2006, 44, 305–311. [Google Scholar]

- Ugbogu, A.E.; Emmanuel, O.; Uche, M.E.; Dike, D.E.; Okoro, B.C.; Ibe, C.; Ude, V.C.; Ekweogu, C.N.; Ugbogu, O.C. The ethnobotanical, phytochemistry and pharmacological activities of Psidium guajava L. Arabian Journal of Chemistry 2022, 15. Arabian Journal of Chemistry 2022, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyibo, A.; Gbadegesin, M.A.; Odunola, O.A. Ethanol extract of Vitellaria paradoxa (Gaertn, F) leaves protects against sodium arsenite - induced toxicity in male wistar rats. Toxicol Rep 2021, 8, 774–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahiru, D.; Obidoa, O. Evaluation of the antioxidant effects of Ziziphus mauritiana Lam. Leaf extracts against chronic ethanol-induced hepatotoxicity in rat liver. Afr J Tradit Complement Altern Med 2007, 5, 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kouam, A.F.; Owona, B.A.; Fifen, R.; Njayou, F.N.; Moundipa, P.F. Inhibition of CYP2E1 and activation of Nrf2 signaling pathways by a fraction from Entada africana alleviate carbon tetrachloride-induced hepatotoxicity. Heliyon 2020, 6, e04602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tietcheu, B.R.G.; Sass, G.; Njayou, N.F.; Mkounga, P.; Tiegs, G.; Moundipa, P.F. Anti-hepatitis C virus activity of crude extract and fractions of Entada africana in genotype 1b replicon systems. Am J Chin Med 2014, 42, 853–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rouf, R.; Uddin, S.J.; Sarker, D.K.; Islam, M.T.; Ali, E.S.; Shilpi, J.A.; Nahar, L.; Tiralongo, E.; Sarker, S.D. Antiviral potential of garlic (Allium sativum) and its organosulfur compounds: A systematic update of pre-clinical and clinical data. Trends Food Sci Technol 2020, 104, 219–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, A.; Cao, S.Y.; Xu, X.Y.; Gan, R.Y.; Tang, G.Y.; Corke, H.; Mavumengwana, V.; Li, H.B. Bioactive Compounds and Biological Functions of Garlic (Allium sativum L.). Foods 2019, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacob, J.R.; Mansfield, K.; You, J.E.; Tennant, B.C.; Kim, Y.H. Natural iminosugar derivatives of 1-deoxynojirimycin inhibit glycosylation of hepatitis viral envelope proteins. J Microbiol 2007, 45, 431–440. [Google Scholar]

- Geng, C.A.; Ma, Y.B.; Zhang, X.M.; Yao, S.Y.; Xue, D.Q.; Zhang, R.P.; Chen, J.J. Mulberrofuran G and isomulberrofuran G from Morus alba L.: anti-hepatitis B virus activity and mass spectrometric fragmentation. J Agric Food Chem 2012, 60, 8197–8202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogunmoyole, T.; Awodooju, M.; Idowu, S.; Daramola, O. Phyllanthus amarus extract restored deranged biochemical parameters in rat model of hepatotoxicity and nephrotoxicity. Heliyon 2020, 6, e05670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, J.R.; Tripathi, P.; Sharma, V.; Chauhan, N.S.; Dixit, V.K. Phyllanthus amarus: ethnomedicinal uses, phytochemistry and pharmacology: a review. J Ethnopharmacol 2011, 138, 286–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.M.; Zhang, Q.; Xu, J.; Zhu, S.; Ke, T.; Gao, D.F.; Xu, Y.B. Inhibition on Hepatitis B virus in vitro of recombinant MAP30 from bitter melon. Mol Biol Rep 2009, 36, 381–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waiyaput, W.; Payungporn, S.; Issara-Amphorn, J.; Panjaworayan, N.T. Inhibitory effects of crude extracts from some edible Thai plants against replication of hepatitis B virus and human liver cancer cells. BMC Complement Altern Med 2012, 12, 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, X.; Li, J.; Deng, N.; Wang, S.; Meng, Y.; Shen, F. Immunoaffinity purification of alpha-momorcharin from bitter melon seeds (Momordica charantia). J Sep Sci 2011, 34, 3092–3098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanafy, A.; Aldawsari, H.M.; Badr, J.M.; Ibrahim, A.K.; Abdel-Hady Sel, S. Evaluation of Hepatoprotective Activity of Adansonia digitata Extract on Acetaminophen-Induced Hepatotoxicity in Rats. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2016, 2016, 4579149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, M.L.; Rita, K.; Bernardo, M.A.; Mesquita, M.F.; Pintao, A.M.; Moncada, M. Adansonia digitata L. (Baobab) Bioactive Compounds, Biological Activities, and the Potential Effect on Glycemia: A Narrative Review. Nutrients 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NAFDAC. The Role Of NAFDAC In Traditional Herbal Medicine Development And Approval In Nigeria. Control, N. A. f. F. a. D. A. a., Ed.; Abuja: 2019; p. 13. NAFDAC. The Role Of NAFDAC In Traditional Herbal Medicine Development And Approval In Nigeria. Control, N. A. f. F. a. D. A. a. Eds.

- Oguntade, A.E.; Oluwalana, I.B. Structure, control and regulation of the formal market for medicinal plants' products in Nigeria. Afr J Tradit Complement Altern Med 2011, 8, 370–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modibbo, M.R.; Ibrahim, H.; Sulaiman, M.Y.; Zakir, B. Maganin Gargajiya: Assessing the Benefits, Challenges, and Evidence of Traditional Medicine in Nigeria. Cureus 2024, 16, e71425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Awodele, O.; Amagon, K.I.; Usman, S.O.; Obasi, P.C. Safety of herbal medicines use: case study of ikorodu residents in Lagos, Nigeria. Curr Drug Saf 2014, 9, 138–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abubakar, I.B.; Kankara, S.S.; Malami, I.; Danjuma, J.B.; Muhammad, Y.Z.; Yahaya, H.; Singh, D.; Usman, U.J.; Ukwuani-Kwaja, A.N.; Muhammad, A.; et al. Traditional medicinal plants used for treating emerging and re-emerging viral diseases in northern Nigeria. Eur J Integr Med 2022, 49, 102094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, A.J.; Odula, I.L.; Etinosa, O.B.; Ifeanyi, O.V. Effectiveness of herbal and conventional management interventions of Hepatitis B virus. Afr J Infect Dis 2025, 19, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).