Submitted:

14 June 2025

Posted:

17 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Waste-Water Treatment: Contaminants and Current Challenges

3. LCB: Composition, Nanoparticle Formulation and Applications

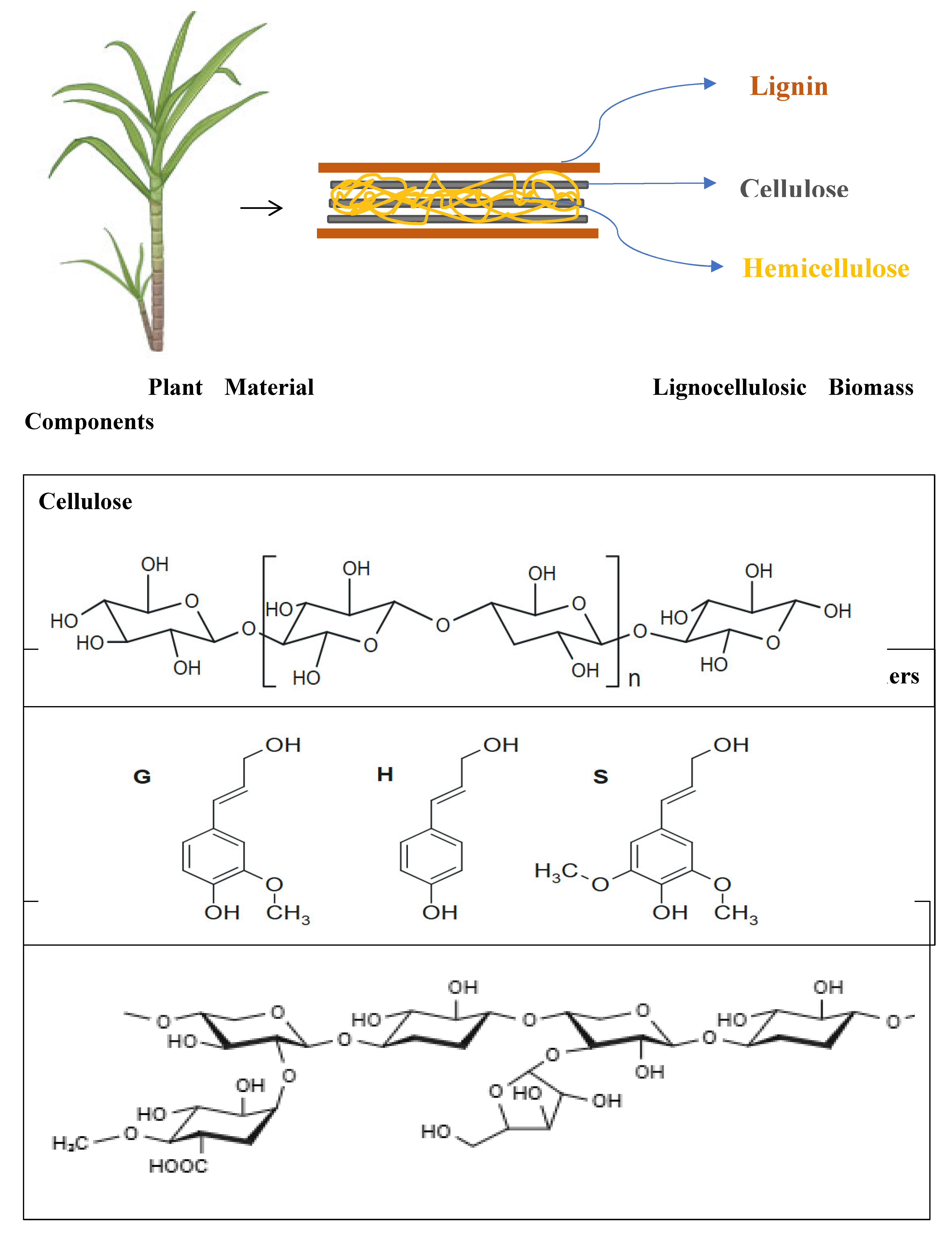

3.1. LCB: Constituents and Structural Overview

3.2. Synthesis of LCB NPs

Characterization of Nanoparticles

4. Nano-Formulations Based on LCB for Waste-Water Treatment

4.1. Nanocellulose

4.2. Nanohemicellulose

4.3. Nanolignin

5. Strategies for Waste-Water Treatment Using LCB

5.1. Adsorption

5.2. AOPs

5.3. Disinfection

5.4. Sensors

6. Advancements in LCB NMs Used for Wastewater Treatment: Patented Technologies and Their Status

7. Other Applications of LCB Nanoparticles

7.1. Food Packaging and Paper Industry:

7.2. Biofuel Production:

7.3. Biomedical Applications:

7.4. Environmental Applications:

8. Future Perspectives

9. Conclusions

Abbreviations

References

- Wang, F. , Ouyang, D., Zhou, Z., Page, S. J., Liu, D., & Zhao, X. Lignocellulosic biomass as sustainable feedstock and materials for power generation and energy storage. Journal of Energy Chemistry 2021, 57, 247–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathania, D. , & Srivastava, A. K. Advances in nanoparticles tailored lignocellulosic biochars for removal of heavy metals with special reference to cadmium (II) and chromium (VI). Environmental Sustainability 2021, 4, 201–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, P. , Ali, S. , Jan, R., & Kim, K.-M. Lignin Nanoparticles: Transforming Environmental Remediation. Nanomaterials 2024, 14, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakhtouna, H. , Benzeid, H., Zari, N., Qaiss, A. E. K., & Bouhfid, R. Recent advances in eco-friendly composites derived from lignocellulosic biomass for wastewater treatment. Biomass Conversion and Biorefinery 2024, 14, 12085–12111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wani, A. A. , Khan, A. M., Manea, Y. K., & Singh, M. Facile synthesis of layered superparamagnetic Fe3O4-MoS2 nanosheets on chitosan for efficient removal of chromium and ciprofloxacin from aqueous solutions. Journal of Water Process Engineering 2023, 51, 103340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

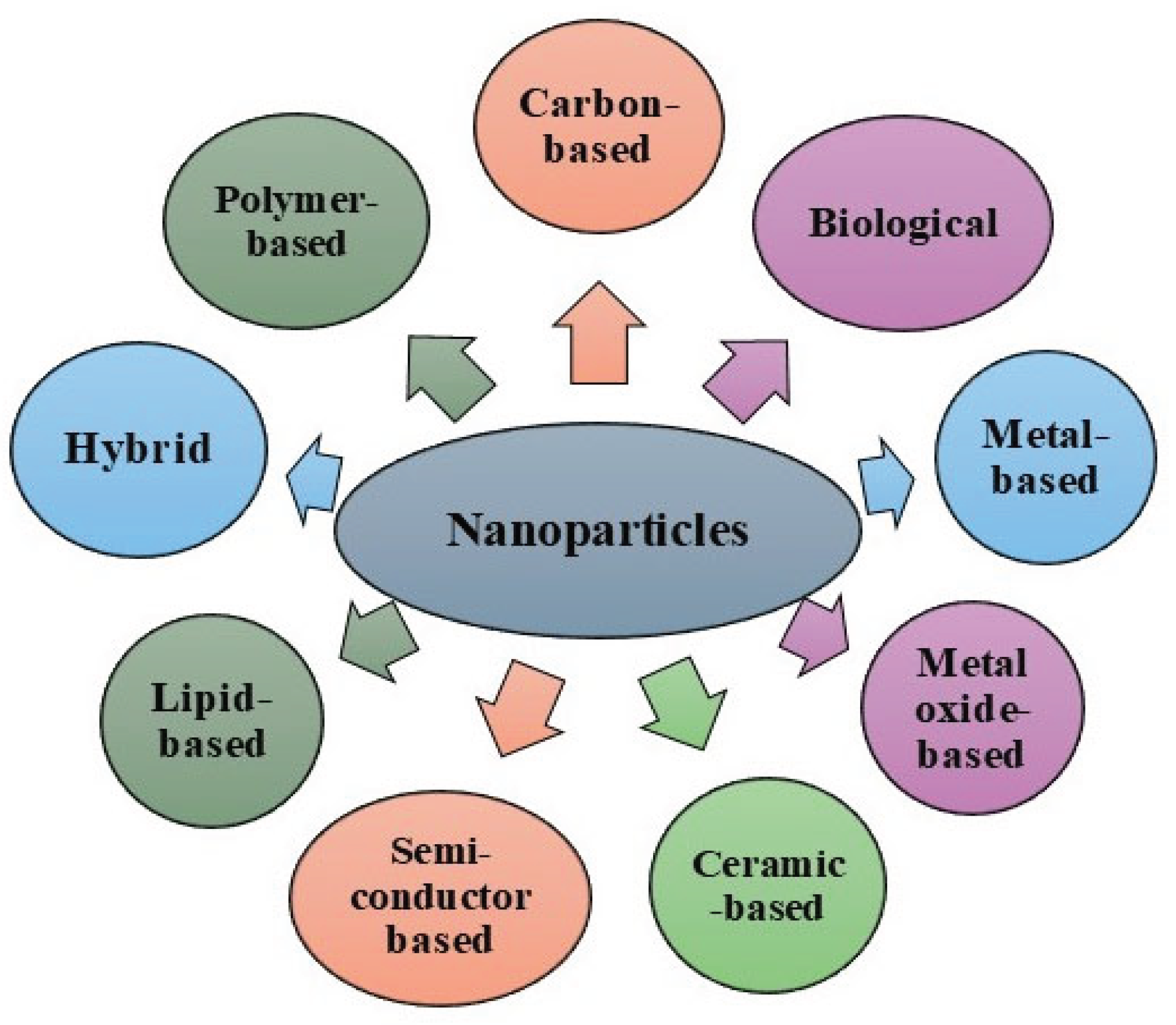

- Namakka, M. , Rahman, Md. R., Said, K. A. M. B., Abdul Mannan, M., & Patwary, A. M. A review of nanoparticle synthesis methods, classifications, applications, and characterization. Environmental Nanotechnology, Monitoring & Management 2023, 20, 100900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mankar, A. R. , Pandey, A., Modak, A., & Pant, K. K. Pretreatment of lignocellulosic biomass: A review on recent advances. Bioresource Technology 2021, 334, 125235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Water, U. N. (2020). Water and climate change. The United Nations World Water Development Report. Retrieved from https://www.unesco.org/en/wwap/wwdr/2020.

- Nishat, A. , Yusuf, M., Qadir, A., Ezaier, Y., Vambol, V., Ijaz Khan, M., Ben Moussa, S., Kamyab, H., Sehgal, S. S., Prakash, C., Yang, H.-H., Ibrahim, H., & Eldin, S. M. Wastewater treatment: A short assessment on available techniques. Alexandria Engineering Journal 2023, 76, 505–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Othmani, A. , Magdouli, S., Senthil Kumar, P., Kapoor, A., Chellam, P. V., & Gökkuş, Ö. Agricultural waste materials for adsorptive removal of phenols, chromium (VI) and cadmium (II) from wastewater: A review. Environmental Research 2022, 204, 111916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, A. , Sharma, A., Yadav, S., Jule, L. T., & Krishnaraj, R. Nanomaterials for Remediation of Environmental Pollutants. Bioinorganic Chemistry and Applications 2021, 2021, 1764647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sajjadi, M. , Ahmadpoor, F., Nasrollahzadeh, M., & Ghafuri, H. Lignin-derived (nano)materials for environmental pollution remediation: Current challenges and future perspectives. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2021, 178, 394–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chauhan, P. S. Lignin nanoparticles: Eco-friendly and versatile tool for new era. Bioresource Technology Reports 2020, 9, 100374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatri, N. , & Tyagi, S. Influences of natural and anthropogenic factors on surface and groundwater quality in rural and urban areas. Frontiers in Life Science 2015, 8, 23–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akter, M. , Bhattacharjee, M., Dhar, A. K., Rahman, F. B. A., Haque, S., Rashid, T. U., & Kabir, S. M. F. Cellulose-Based Hydrogels for Wastewater Treatment: A Concise Review. Gels 2021, 7, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, J. , Sharma, S., & Soni, V. Classification and impact of synthetic textile dyes on Aquatic Flora: A review. Regional Studies in Marine Science 2021, 45, 101802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, Y. , & Li, Z. Application of Lignin and Its Derivatives in Adsorption of Heavy Metal Ions in Water: A Review. ACS Sustainable Chemistry & Engineering 2018, 6, 7181–7192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agoro, M. A. , Adeniji, A. O., Adefisoye, M. A., & Okoh, O. O. Heavy Metals in Wastewater and Sewage Sludge from Selected Municipal Treatment Plants in Eastern Cape Province, South Africa. Water 2020, 12, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seruga, P. , Krzywonos, M., Pyżanowska, J., Urbanowska, A., Pawlak-Kruczek, H., & Niedźwiecki, Ł. Removal of Ammonia from the Municipal Waste Treatment Effluents using Natural Minerals. Molecules 2019, 24, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y. , Liu, G., Rood, J., Liang, L., Bray, G. A., de Jonge, L., Coull, B., Furtado, J. D., Qi, L., Grandjean, P., & Sun, Q. Perfluoroalkyl substances and changes in bone mineral density: A prospective analysis in the POUNDS-LOST study. Environmental Research 2019, 179, 108775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roa, K. , Oyarce, E., Boulett, A., ALSamman, M., Oyarzún, D., Pizarro, G. D. C., & Sánchez, J. Lignocellulose-based materials and their application in the removal of dyes from water: A review. Sustainable Materials and Technologies 2021, 29, e00320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collin, M. S. , Venkatraman, S. K., Vijayakumar, N., Kanimozhi, V., Arbaaz, S. M., Stacey, R. G. S., Anusha, J., Choudhary, R., Lvov, V., Tovar, G. I., Senatov, F., Koppala, S., & Swamiappan, S. Bioaccumulation of lead (Pb) and its effects on human: A review. Journal of Hazardous Materials Advances 2022, 7, 100094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamaru, Y. M. , Matsuda, R., & Sonoda, T. Environmental risks of organic fertilizer with increased heavy metals (Cu and Zn) to aquatic ecosystems adjacent to farmland in the northern biosphere of Japan. Science of The Total Environment 2023, 884, 163861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, G. , Gao, Y., Xue, K., Qi, Y., Fan, Y., Tian, X.,... & Liu, J. Toxicity mechanisms and remediation strategies for chromium exposure in the environment. Frontiers in Environmental Science 2023, 11, 1131204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamba, M. , Graham, D. W., & Ahammad, S. Z. Hospital Wastewater Releases of Carbapenem-Resistance Pathogens and Genes in Urban India. Environmental Science & Technology 2017, 51, 13906–13912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakhtouna, H. , Benzeid, H., Zari, N., Qaiss, A. el kacem, & Bouhfid, R. Functional CoFe2O4-modified biochar derived from banana pseudostem as an efficient adsorbent for the removal of amoxicillin from water. Separation and Purification Technology 2021, 266, 118592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chettleburgh, C. , Ma, S. X., Swinwood-Sky, M., McDougall, H., Kireina, D., Taggar, G., McBean, E., Parreira, V., Goodridge, L., & Habash, M. Evaluation of four human-associated fecal biomarkers in wastewater in Southern Ontario. Science of The Total Environment 2023, 904, 166542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamai, S. , & Suzuki, Y. Diversity of Fecal Indicator Enterococci among Different Hosts: Importance to Water Contamination Source Tracking. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehra, S. , Saroha, J., Rani, E., Sharma, V., Goswami, L., Gupta, G., Srivastava, A. K., & Sharma, S. N. Development of visible light-driven SrTiO3 photocatalysts for the degradation of organic pollutants for waste-water treatment: Contrasting behavior of MB & MO dyes. Optical Materials 2023, 136, 113344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhiman, S. , Agarwal, S., & Gupta, H. Application of phosphonium ionic liquids to separate Ga, Ge and In utilizing solvent extraction: A review. Journal of Ionic Liquids 2024, 4, 100080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korak, J. A. , Mungan, A. L., & Watts, L. T. Critical review of waste brine management strategies for drinking water treatment using strong base ion exchange. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2023, 441, 129473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahu, J. N. , Kapelyushin, Y., Mishra, D. P., Ghosh, P., Sahoo, B. K., Trofimov, E., & Meikap, B. C. Utilization of ferrous slags as coagulants, filters, adsorbents, neutralizers/stabilizers, catalysts, additives, and bed materials for water and wastewater treatment: A review. Chemosphere 2023, 325, 138201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iftekhar, S. , Heidari, G., Amanat, N., Zare, E. N., Asif, M. B., Hassanpour, M., Lehto, V. P., & Sillanpaa, M. Porous materials for the recovery of rare earth elements, platinum group metals, and other valuable metals: A review. Environmental Chemistry Letters 2022, 20, 3697–3746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, S. , Awad, J., Sarkar, B., Chow, C. W. K., Duan, J., & van Leeuwen, J. Coagulation of dissolved organic matter in surface water by novel titanium (III) chloride: Mechanistic surface chemical and spectroscopic characterisation. Separation and Purification Technology 2019, 213, 213–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghimire, U. , Jang, M., Jung, S. P., Park, D., Park, S. J., Yu, H., & Oh, S.-E. Electrochemical Removal of Ammonium Nitrogen and COD of Domestic Wastewater using Platinum Coated Titanium as an Anode Electrode. Energies 2019, 12, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohapatra, S. , Snow, D., Shea, P., Gálvez-Rodríguez, A., Kumar, M., Padhye, L. P., & Mukherji, S. Photodegradation of a mixture of five pharmaceuticals commonly found in wastewater: Experimental and computational analysis. Environmental Research 2023, 216, 114659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Julian, H. , Nurgirisia, N., Qiu, G., Ting, Y.-P., & Wenten, I. G. Membrane distillation for wastewater treatment: Current trends, challenges and prospects of dense membrane distillation. Journal of Water Process Engineering 2022, 46, 102615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raj, S. , Singh, H., & Bhattacharya, J. Treatment of textile industry wastewater based on coagulation-flocculation aided sedimentation followed by adsorption: Process studies in an industrial ecology concept. Science of The Total Environment 2023, 857, 159464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, J. , Qi, P., Wang, Y., Liu, Y., & Sui, K. Electrostatic assembly construction of polysaccharide functionalized hybrid membrane for enhanced antimony removal. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2021, 410, 124633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reisoglu, Ş. , & Aydin, S. Bacteriophage and Their Potential Use in Bioaugmentation of Biological Wastewater Treatment Processes. Sustainability 2023, 15, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brar, K. K. , Magdouli, S., Othmani, A., Ghanei, J., Narisetty, V., Sindhu, R., Binod, P., Pugazhendhi, A., Awasthi, M. K., & Pandey, A. Green route for recycling of low-cost waste resources for the biosynthesis of nanoparticles (NPs) and nanomaterials (NMs)-A review. Environmental Research 2022, 207, 112202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y. , Tan, W., Wang, J., Xu, J., Wang, K., & Jiang, J. Liquefaction of bamboo biomass and production of three fractions containing aromatic compounds. Journal of Bioresources and Bioproducts 2020, 5, 114–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kucharska, K. , Rybarczyk, P., Hołowacz, I., Łukajtis, R., Glinka, M., & Kamiński, M. Pretreatment of Lignocellulosic Materials as Substrates for Fermentation Processes. Molecules 2018, 23, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namakka, M. , Rahman, Md. R., Said, K. A. M. B., Abdul Mannan, M., & Patwary, A. M. A review of nanoparticle synthesis methods, classifications, applications, and characterization. Environmental Nanotechnology, Monitoring & Management 2023, 20, 100900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, D. , Shen, F., Hu, J., Huang, M., Zhao, L., He, J., Li, Q., Zhang, S., & Shen, F. Complete conversion of lignocellulosic biomass into three high-value nanomaterials through a versatile integrated technical platform. Chemical Engineering Journal 2022, 428, 131373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartoyo, A. P. P. , & Solikhin, A. Valorization of Oil Palm Trunk Biomass for Lignocellulose/Carbon Nanoparticles and Its Nanomaterials Characterization Potential for Water Purification. Journal of Natural Fibers 2023, 20, 2131688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedin, F. A. , Mohan, H., Thomas, S., & Kochupurackal, J. Synthesis and characterization of nanocelluloses isolated through acidic hydrolysis and steam explosion of Gliricidia sepium plant fiber. Biomass Conversion and Biorefinery 2024, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camargos, C. H. M. , & Rezende, C. A. Antisolvent versus ultrasonication: Bottom-up and top-down approaches to produce lignin nanoparticles (LNPs) with tailored properties. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2021, 193, 647–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samsalee, N. , Meerasri, J., & Sothornvit, R. Rice husk nanocellulose: Extraction by high-pressure homogenization, chemical treatments and characterization. Carbohydrate Polymer Technologies and Applications 2023, 6, 100353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilatto, S. , Marconcini, J. M., Mattoso, L. H. C., & Farinas, C. S. Lignocellulose nanocrystals from sugarcane straw. Industrial Crops and Products 2020, 157, 112938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L. , Shi, Y., Gao, B., Zhao, Y., Jiang, Y., Zha, Z., Xue, W., & Gong, L. Lignin Nanoparticles: Green Synthesis in a γ-Valerolactone/Water Binary Solvent and Application to Enhance Antimicrobial Activity of Essential Oils. ACS Sustainable Chemistry & Engineering 2020, 8, 714–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, B. , & Arantes, V. Production of cellulose nanocrystals integrated into a biochemical sugar platform process via enzymatic hydrolysis at high solid loading. Industrial Crops and Products 2020, 152, 112377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMichael, P. , Hoque, M., Santos, F. B. dos, French, V., & Johan Foster, E. Binary mixture of subcritical water and acetone: A hybrid solvent system towards the production of lignin nanoparticles. Reaction Chemistry & Engineering 2024, 9, 226–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juikar, S. J. , & Vigneshwaran, N. Extraction of nanolignin from coconut fibers by controlled microbial hydrolysis. Industrial Crops and Products 2017, 109, 420–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, W. , Kamboj, A., Banerjee, I., & Jaiswal, K. K. Pomegranate peels mediated synthesis of calcium oxide (CaO) nanoparticles, characterization, and antimicrobial applications. Inorganic and Nano-Metal Chemistry 2024, 54, 157–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aradmehr, A. , & Javanbakht, V. A novel biofilm based on lignocellulosic compounds and chitosan modified with silver nanoparticles with multifunctional properties: Synthesis and characterization. Colloids and Surfaces A: Physicochemical and Engineering Aspects 2020, 600, 124952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aref, M. S. , & Salem, S. S. Bio-callus synthesis of silver nanoparticles, characterization, and antibacterial activities via Cinnamomum camphora callus culture. Biocatalysis and Agricultural Biotechnology 2020, 27, 101689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayachandran, A., T. r., A., & Nair, A. S. Green synthesis and characterization of zinc oxide nanoparticles using Cayratia pedata leaf extract. Biochemistry and Biophysics Reports 2021, 26, 100995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khane, Y. , Benouis, K., Albukhaty, S., Sulaiman, G. M., Abomughaid, M. M., Al Ali, A., Aouf, D., Fenniche, F., Khane, S., Chaibi, W., Henni, A., Bouras, H. D., & Dizge, N. Green Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles Using Aqueous Citrus limon Zest Extract: Characterization and Evaluation of Their Antioxidant and Antimicrobial Properties. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botteon, C. E. A. , Silva, L. B., Ccana-Ccapatinta, G. V., Silva, T. S., Ambrosio, S. R., Veneziani, R. C. S., Bastos, J. K., & Marcato, P. D. Biosynthesis and characterization of gold nanoparticles using Brazilian red propolis and evaluation of its antimicrobial and anticancer activities. Scientific Reports 2021, 11, 1974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altammar, K. A. A review on nanoparticles: Characteristics, synthesis, applications, and challenges. Frontiers in Microbiology 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd Elkodous, M., S. El-Sayyad, G., Abdel Maksoud, M. I. A., Kumar, R., Maegawa, K., Kawamura, G., Tan, W. K., & Matsuda, A. Nanocomposite matrix conjugated with carbon nanomaterials for photocatalytic wastewater treatment. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2021, 410, 124657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amjad Mumtaz Khan, Manea, Y. K., & Nabi, S. A. Synthesis and Characterization of Nanocomposite Acrylamide TIN(IV) Silicomolybdate: Photocatalytic Activity and Chromatographic Column Separations. Journal of Analytical Chemistry 2019, 74, 330–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barhoum, A. , Jeevanandam, J., Rastogi, A., Samyn, P., Boluk, Y., Dufresne, A., Danquah, M. K., & Bechelany, M. Plant celluloses, hemicelluloses, lignins, and volatile oils for the synthesis of nanoparticles and nanostructured materials. Nanoscale 2020, 12, 22845–22890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, M. W. , Manan, S., Ul-Islam, M., Revin, V. V., Thomas, S., & Yang, G. Introduction to nanocellulose. In Nanocellulose: synthesis, structure, properties and applications 2021; pp. 1-50. [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z. , Hu, C., Dichiara, A. B., Jiang, W., & Gu, J. Cellulose Nanofibril/Carbon Nanomaterial Hybrid Aerogels for Adsorption Removal of Cationic and Anionic Organic Dyes. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goswami, R. , Mishra, A., Bhatt, N., Mishra, A., & Naithani, P. Potential of chitosan/nanocellulose based composite membrane for the removal of heavy metal (chromium ion). Materials Today: Proceedings 2021, 46, 10954–10959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goswami, R. , Mishra, A., Bhatt, N., & Prasad, B. Chitosan/NC Based Bio Composite Membrane: An Impact of Varying Amount of Chitosan on Filtration Ability for the Malachite Green Dye. Journal of Graphic Era University 2022, 117–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariaeenejad, S. , Motamedi, E., & Salekdeh, G. H. Highly efficient removal of dyes from wastewater using nanocellulose from quinoa husk as a carrier for immobilization of laccase. Bioresource Technology 2022, 349, 126833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijaya, C. J. , Ismadji, S., & Gunawan, S. A Review of Lignocellulosic-Derived Nanoparticles for Drug Delivery Applications: Lignin Nanoparticles, Xylan Nanoparticles, and Cellulose Nanocrystals. Molecules 2021, 26, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, G.-Q. , Su, L.-Y., Yue, P.-P., Huang, Y.-H., Bian, J., Li, M.-F., Peng, F., & Sun, R.-C. Syntheses of xylan stearate nanoparticles with loading function from by-products of viscose fiber mills. Cellulose 2019, 26, 7195–7206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farghal, H. H. , Nebsen, M., & El-Sayed, M. M. H. Multifunctional Chitosan/Xylan-Coated Magnetite Nanoparticles for the Simultaneous Adsorption of the Emerging Contaminants Pb(II), Salicylic Acid, and Congo Red Dye. Water 2023, 15, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqahtani, M. S. , Kazi, M., Ahmad, M. Z., Syed, R., Alsenaidy, M. A., & Albraiki, S. A. Lignin nanoparticles as a promising vaccine adjuvant and delivery system for ovalbumin. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2020, 163, 1314–1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azimvand, J. , Didehban, K., & Mirshokraie, S. ahmad. Preparation and Characterization of Nano-lignin Biomaterial to Remove Basic Red 2 dye from aqueous solutions. Pollution 2018, 4, 395–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azimvand, J. , Didehban, K., & Mirshokraie, S. Safranin-O removal from aqueous solutions using lignin nanoparticle-g-polyacrylic acid adsorbent: Synthesis, properties, and application. Adsorption Science & Technology 2018, 36, 1422–1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohni, S. , Hassan, T., Khan, S. B., Akhtar, K., Bakhsh, E. M., Hashim, R., Nidaullah, H., Khan, M., & Khan, S. A. Lignin nanoparticles-reduced graphene oxide based hydrogel: A novel strategy for environmental applications. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2023, 225, 1426–1436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pourbaba, R. , Abdulkhani, A., Rashidi, A., & Ashori, A. Lignin nanoparticles as a highly efficient adsorbent for the removal of methylene blue from aqueous media. Scientific Reports 2024, 14, 9039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, R. , Hu, J., Chen, X., Xu, Z., Wen, Z., & Jin, M. Facile synthesis of manganese oxide modified lignin nanocomposites from lignocellulosic biorefinery wastes for dye removal. Bioresource Technology 2020, 315, 123846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorat, M. N. , Jagtap, A., & Dastager, S. G. Fabrication of bacterial nanocellulose/polyethyleneimine (PEI-BC) based cationic adsorbent for efficient removal of anionic dyes. Journal of Polymer Research 2021, 28, 354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makhesana, M. A. , Patel, K. M., & Nyabadza, A. (2024). Applicability of nanomaterials in water and waste-water treatment: A state-of-the-art review and future perspectives. Materials Today: Proceedings 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y. , Li, X., Liu, S., Liu, Y., Kong, T., Zhang, H., Duan, X., Chen, C., & Wang, S. Roles of Catalyst Structure and Gas Surface Reaction in the Generation of Hydroxyl Radicals for Photocatalytic Oxidation. ACS Catalysis 2022, 12, 2770–2780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.-D. , Zhang, L.-Q., Zhou, P., Liu, Y., Lin, H., Zhong, G.-J., Yao, G., Li, Z.-M., & Lai, B. Natural cellulose supported carbon nanotubes and Fe3O4 NPs as the efficient peroxydisulfate activator for the removal of bisphenol A: An enhanced non-radical oxidation process. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2022, 423, 127054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S. F. , Mofijur, M., Ahmed, B., Mehnaz, T., Mehejabin, F., Maliat, D., Hoang, A. T., & Shafiullah, G. M. Nanomaterials as a sustainable choice for treating wastewater. Environmental Research 2022, 214, 113807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M. , Shi, Y., Wang, R., Chen, K., Zhou, N., Yang, Q., & Shi, J. Triple-functional lignocellulose/chitosan/Ag@TiO2 nanocomposite membrane for simultaneous sterilization, oil/water emulsion separation, and organic pollutant removal. Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering 2021, 9, 106728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J. , Zhou, P., Xiao, X., Zhang, C., Huo, K., & Xu, J. Introducing lignocellulose valorization into multifunctional water purification: Metal-ion sensing, antibiotic dissociation, and capacitive deionization. Chemical Engineering Journal 2024, 497, 154490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, R. , Gao, J., Wu, M., & Chen, X. (2025). Composite nanofiltration membrane capable of efficiently intercepting ammonium sulfate and ammonium nitrate while adsorbing and removing mercury ions and preparation method thereof (Patent No. US20250073644). North China Electric Power University (Baoding).

- Reyes Contreras, P. I. , Vásquez Garay, F. M., & Araya Hormazábal, I. J. (2024). Adsorbing agent based on lignin-coated, high-selectivity, regenerable and reusable magnetic micro/nanoparticles, for adsorbing heavy metals from wastewater and polluted soil (Patent No. WO2024103192A1). Fund Leitat Chile.

- Xiao, L. , Jia, J., Sun, R., Wang, Q., Ren, Z., & Li, X. (2023). Preparation method and application of lignin-based heavy metal ion adsorbent (Patent No. CN118874421A). Univ Dalian Polytechnic.

- Jin, M. , Zhai, R., Chen, X., Xu, Z., & Wen, Z. (2023). Lignin/manganese oxide composite adsorption material and preparation method and application thereof (Patent No. CN112844324A). Univ Nanjing Sci & Tech.

- Ao, C. , Li, J., Zhong, S., Yuan, L., Zhang, Z., & Zhang, B. (2023). Method for preparing water-stable cellulose aerogel without cross-linking agent and application of water-stable cellulose aerogel (Patent No. CN116675901A). Univ Kunming Science & Technology.

- Deng, Z. , Hu, X., & Zhang, W. (2023). Nanocellulose-based MIL-100-Fe composite aerogel as well as preparation method and application thereof (Patent No. CN117019110A). Univ Tongji.

- Mamane, H. , Gerchman, Y., & Peretz, R. (2021). Process for conversion of cellulose recycling or waste material to ethanol, nanocellulose, and biosorbent material (Patent No. WO2021226094A1). Univ Ramot.

- Zhang, X. , Luo, W., Xiao, N., Chen, M., & Liu, C. Construction of functional composite films originating from hemicellulose reinforced with poly (vinyl alcohol) and nano-ZnO. Cellulose 2020, 27, 1341–1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, N. , Vickram, S., Thanigaivel, S., Subbaiya, R., Kim, W., Karmegam, N., & Govarthanan, M. Nanomaterials for transforming barrier properties of lignocellulosic biomass towards potential applications–A review. Fuel 2022, 316, 123444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H. , Xue, T., Wang, S., Jia, X., Cao, S., Niu, B., & Yan, H. Preparation, characterization and food packaging application of nano ZnO@ Xylan/quaternized xylan/polyvinyl alcohol composite films. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2022, 215, 635–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, P. , Thakur, M., Tondan, D., Bamrah, G. K., Misra, S., Kumar, P.,... & Kulshrestha, S. Nanomaterial conjugated lignocellulosic waste: cost-effective production of sustainable bioenergy using enzymes. 3 Biotech 2021, 11, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rekha, B. , & Saravanathamizhan, R. Preparation and characterization of biomass-based nanocatalyst for hydrolysis and fermentation of catalytic hydrolysate to bioethanol. Biomass Conversion and Biorefinery 2023, 13, 1601–1612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haque, S. , Singh, R., Harakeh, S., Teklemariam, A. D., Tayeb, H. H., Deen, P. R.,... & Srivastava, M. Green synthesis of nanostructures from rice straw food waste to improve the antimicrobial efficiency: New insight. International Journal of Food Microbiology 2023, 386, 110016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamza, M. F. , Fouda, A., Elwakeel, K. Z., Wei, Y., Guibal, E., & Hamad, N. A. Phosphorylation of Guar Gum/Magnetite/Chitosan Nanocomposites for Uranium (VI) Sorption and Antibacterial Applications. Molecules 2021, 26, 1920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M. , Zhou, H., Hao, L., Chen, H., & Zhou, X. A high-efficient nano pesticide-fertilizer combination fabricated by amino acid-modified cellulose-based carriers. Pest Management Science 2022, 78, 506–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montazeri, M. , & Norouzbeigi, R. Investigation of synergistic effects incorporating esterified lignin and guar gum composite aerogel for sustained oil spill cleanup. Scientific Reports 2024, 14, 13892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahnaz, T. , Vishnu Priyan, V., Jayakumar, A., & Narayanasamy, S. Magnetic nanocellulose from Cyperus rotundas grass in the absorptive removal of rare earth element cerium (III): Toxicity studies and interpretation. Chemosphere 2022, 287, 131912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J. , Xu, J. J., Lin, Q., Jiang, L., Zhang, D., Li, Z.,... & Loh, X. J. Lignin-incorporated nanogel serving as an antioxidant biomaterial for wound healing. ACS Applied Bio Materials 2020, 4, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haider, Md. K. , Kharaghani, D., Sun, L., Ullah, S., Sarwar, M. N., Ullah, A., Khatri, M., Yoshiko, Y., Gopiraman, M., & Kim, I. S. Synthesized bioactive lignin nanoparticles/polycaprolactone nanofibers: A novel nanobiocomposite for bone tissue engineering. Biomaterials Advances 2023, 144, 213203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L. , Kang, Y., Zhang, W., Yang, J., Li, H., Niu, M., Guo, Y., & Wang, Z. Preparation of Lignin-Based Nanoparticles with Excellent Acidic Tolerance as Stabilizer for Pickering Emulsion. Polymers 2023, 15, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, M. , Singh, K. R., Singh, T., Asiri, M., Suliman, M., Sabia, H., Deen, P. R., Chaube, R., & Singh, J. Bioinspired fabrication of zinc hydroxide-based nanostructure from lignocellulosic biomass Litchi chinensis leaves and its efficacy evaluation on antibacterial, antioxidant, and anticancer activity. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2023, 253, 126886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X. , Li, Q., Wu, H., Zhou, Z., Feng, S., Deng, P., Zou, H., Tian, D., & Lu, C. Sustainable Starch/Lignin Nanoparticle Composites Biofilms for Food Packaging Applications. Polymers 2023, 15, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, T. , Zhang, Z., Li, Y., Miao, X., & Ji, J. Continuous production of lignin nanoparticles using a microchannel reactor and its application in UV-shielding films. RSC Advances 2019, 9, 24915–24921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| S. No. | Source | Class of contaminant | Major contaminants | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Agricultural | Organic Pollutant |

Pesticides and fertilizers, stable and persistent, accumulate in wastewater, posing serious threats to human health. Heavy metals, Fe, Zn, Cu, and Pb are most abundant, while others such as Mn, Al, Cr, As, Se, Hg, Cd, Mo, Ni are present in trace amounts. |

(Agoro et al., 2020) |

| Inorganic Pollutant |

N and NH3, excessive nitrogenous compound’s discharge, ammonia is the root cause of various detrimental effects including accelerated eutrophication, algal blooms, and oxygen depletion. | (Seruga et al., 2019) | ||

| 2. | Industrial | Organic Pollutant |

Dyes are major effluents of food, textile, paint and varnishing industries; highly stable and resistant to degradation by microorganisms; severely toxic and recalcitrant xenobiotic compounds. Azo dyes are most toxic; have carcinogenic effects. Azure B, if introduced in the biological system, can affect the nucleic acid content, particularly dsDNA. Polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAs), by-product/used in manufacturing in various industries including food-packaging, oil-refineries, firefighting, dyes and wax. Main PFAs include perfluoro octane sulfonate (PFOS) and perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) which are highly resistant and cause a milieu of diseases comprised of neurological disorders, asthma, cancer (liver, pancreatic adenocarcinoma). |

(Hu et al., 2019; Roa et al., 2021; Roy et.al., 2021; Chakhtouna et al., 2024) |

| Inorganic Pollutant | Heavy metals such as Cr, As & Cd are major industrial effluent contaminants, that are classified as strong carcinogens and teratogens by US EPA, causing kidney dysfunction, osteoporosis, GIT, reproductive organs related cancers. Pb and As cause serious CNS damage, Hg leads to allergies, GIT, reproductive and respiratory tract disorders, Zn and Cu cause hepatic disorders and Ni causes serious dermatitis conditions. | (Pathania & Srivastava, 2021; Collin et al., 2022; Nakamaru et al., 2023; Yan et al., 2023) |

||

| 3. | Hospitals | Microbio-logical |

Pathogenic Microbes, including AMR bacteria i.e., fecal coliforms (FC), carbapenem resistant enterobacteriaceae (CRE), extended spectrum beta-lactamases (ESBL), were found to be around nine orders of magnitude more in hospital wastewater as compared to local sewage waters. | (Lamba et al., 2017) |

| Organic pollutants | Prevalence of pharmaceutical and personal care products (PPCPs) including xenobiotics such as antibiotics, anti-inflammatory drugs, steroids, deodorants, antimycotics, and mosquito repellents in water bodies is increasing, harming aquatic flora and fauna. | (Chakhtouna et al., 2021) |

||

| 4. | Domestic household | Microbio- logical waste | Animal and human fecal matter comprises of enteric pathogens like Enterococcus spp., E. coli which are responsible for communicable disease transmission. Human faecal biomarkers (HFBs) are one of the indicative markers for monitoring pathogen transmission from humans via wastewater. | (Chettleburgh et al., 2023; Tamai & Suzuki, 2023) |

| Organic and Inorganic pollutant | Household wastes including kitchen waste, surfactants i.e., detergents, and excreta, all primarily contain nitrogenous compounds like NH3, PO43−, SO42- as major contaminants. | (Mehra et al., 2023) |

| S. No. | Treatment | Method | Application | Disadvantages | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Chemical |

Solvent extraction |

In the chemical and mining industries, as well as in processing fermentation products like antibiotics, amino acids, and steroids. |

Release of volatile organic compounds (VOCs); Use of toxic and flammable solvents; high investment in equipment. |

(Dhiman et al., 2024) |

| Ion exchange |

In medical research, food processing, mining, and agriculture. | High operational and chemical expenses. |

(Korak et al., 2023) |

||

| Neutralization |

Used as a pretreatment method before actual 1֯ and 2֯ treatment of wastewater. | Disposal issues; May lead to production of hazardous by-products; costly. |

(Sahu et al., 2023) |

||

| Adsorption |

For eliminating toxic organic and mineral compounds from contaminated water. | Limited adsorption capacity; requires frequent replacement or regeneration; not suitable for all pollutants. |

(Iftekhar et al., 2022) |

||

| Precipitation |

In metallurgy, pharmaceutical industry, food and beverage industry | Accumulation of a huge amount of sludge; disposal or treatment issues. |

(Hussain et al., 2019) |

||

| Electrochemical oxidation |

It has been employed to reduce oxygen demand and eliminate colour from wastewater. | Generation of byproducts and elevated energy costs. |

(Ghimire et al., 2019) |

||

| Photodegradation |

Broad range applications in wastewater disinfection, pharmaceutical industries and environmental remediation | Formation of potentially toxic and less biodegradable byproducts; high energy demand; limited efficiency in turbid water. | (Mohapatra et al., 2023) | ||

| 2. | Physical | Distillation |

In chemical, brewery, pharmaceutical, cosmetic and oil industries. |

Slow process; high energy requirements; not suitable for non-volatile compounds; efficiency for complex mixtures e.g., azeotropes is less. Membrane distillation (MD) is more sensitive to fouling and scaling. |

(Julian et al., 2022) |

| Sedimentation |

In mineral processing, chemical and petrochemical, food and pharmaceutical industries | Not effective for dissolved compounds; very slow process; effective only when used in conjunction with other methods. | (Raj et al., 2023) |

||

| Membrane filtration | In juice clarification (food and beverage industry), textile and dye industry, biotech and petrochemical sector. | Membrane clogging; requires timely cleaning; thick sludge formation | (Zeng et al., 2021) | ||

| 3. | Biological | Microbial activity | In mining, solid waste management (SWM), biofuel production, air pollution control | Biofilm and fouling issues; longer processing time; sensitivity to environmental conditions; not suitable for all types of recalcitrant pollutants. | (Reisoglu & Aydin, 2023) |

| S.No. | NP preparation technologies | NP size (diameter) range (nm) | Yield (%) | Advantages | Drawbacks | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Steam explosion | ~6 | 51.4 | Eco-friendly; efficient breakdown and scalable method | High energy input; equipment prone to wear and tear; 2֯ byproducts produced | (Fedin et al., 2024) |

| 2. | Ultrasonication | 25-50 | 90±2 | No chemicals used; eco-friendly; fast | Specialized equipment required; limted control on particle size | (Camargos & Rezende, 2021) |

| 3. | High pressure homogenization (HPH) | 10-13 | 19 | Quick and efficient; chemical-free; scalable | Requires high energy; clogging; damage to crystalline structure; heat generation | (Samsalee et al., 2023) |

| 4. | Acid hydrolysis | 10-20 | 40-64 | Monodisperse size distribution | Use of hazardous acids; Residual acid | (Bilatto et al., 2020) |

| 5. | Solvent shifting/ solvent exchange/Anti-solvent precipitation | 250 | 90 | NPs with uniform size distribution; simple and cost-effective process | Time constraints; residual solvent; high solvent consumption | (Chen et al., 2020) |

| 6. | Enzymatic hydrolysis | 20 | 50 | NPs with greater thermal stability and higher aspect ratio | Costly; time consuming | (Pereira & Arantes, 2020) |

| 7. | Sub-critical water | 1.6-128 | 88-92 | Environment-friendly; no residual solvents | Costly; complex; high pressure system required | (McMichael et al., 2024) |

| 8. | Self-assembly | 50 | 93± 4 | No harmful chemicals required; regulated method | Time consuming; post-treatment stabilization required | (Camargos & Rezende, 2021) |

| 9. | Biosynthesis | 1-500 | - | Abundantly available substrate; affordable and ecofriendly approach | Safety risk; slow process | (Brar et al., 2022) |

| 10. | Microbial hydrolysis | 20-250 | 58.4 | Eco-friendly; cost-effective highly specific and selective; | Longer duration; less yield and efficiency; contamination issues; lignin recalcitrance | (Juikar & Vigneshwaran, 2017) |

| S.No. | Patent no. (publication date) | Title | Applicant(s) | Description | References |

| 1. | US20250073644 (2025-03-06) |

Composite nanofiltration membrane capable of efficiently intercepting ammonium sulfate and ammonium nitrate while adsorbing and removing mercury ions and preparation method thereof | North China Electric Power University (Baoding) | A composite nanofiltration membrane fabricated using CNFs and carboxylated carbon nanotubes, further integrated with MXene layers. The membrane is designed to efficiently intercept ammonium sulfate and ammonium nitrate (NH₄⁺ salts) while simultaneously adsorbing mercury (Hg²⁺) ions. The preparation involves vacuum filtration followed by drying, resulting in enhanced selectivity and efficiency for wastewater treatment applications. |

Hao et.al., 2025 |

| 2. | WO2024103192A1 (2024-05-23) | Adsorbing agent based on lignin-coated, high-selectivity, regenerable and reusable magnetic micro/nanoparticles, for adsorbing heavy metals from wastewater and polluted soil; preparation method; and method for removing and quantifying the heavy metal load |

Fund Leitat Chile | Use of lignin coated magnetic micro/NPs to selectively adsorb heavy metals like Cu, Pb, and As, from water or soil. |

Reyes Contreras et al., 2024 |

| 3. | CN116675901A (2023-09-01) | Method for preparing water-stable cellulose aerogel without cross-linking agent and application of water-stable cellulose aerogel |

Univ Kunming Science and Technology | A green synthesis route for producing water-stable cellulose aerogels without the use of chemical cross-linking agents. Utilizing solvent-assisted extraction and physical stripping of biomass, the resulting aerogel exhibits high porosity, excellent water stability, and strong potential for large-scale adsorption of environmental pollutants. |

Ao et.al., 2023 |

| 4. | CN118874421A (2024-11-01) | Preparation method and application of lignin-based heavy metal ion adsorbent | Univ Dalian Polytechnic |

This patent describes the development of a lignin-based adsorbent comprising Fe–Fe₂O₃ nanochains encapsulated within polymer coatings. The formulation exhibits high efficacy in the adsorption and removal of Pb²⁺ from wastewater, positioning it as a potent candidate for targeted heavy metal remediation. |

Xiao et.al., 2023 |

| 5. | CN117019110A (2023-11-10) | Nanocellulose-based MIL-100-Fe composite aerogel as well as preparation method and application | Univ Tongji | A nanocellulose-based composite aerogel integrated with MIL-100-Fe, a metal-organic framework (MOF), synthesized via a green method. The composite exhibits a high surface area, excellent adsorption performance, pH stability, and recyclability, making it an eco-friendly and efficient adsorbent for wastewater treatment. |

Deng Z et.al., 2023 |

| 6. | WO2021226094A1 (2021-11-11) | Process for conversion of cellulose recycling or waste material to ethanol, nanocellulose and biosorbent material | Univ Ramot [IL] and Geraghty Erin [US]. | Low-dose ozone treatment to convert cellulosic waste into ethanol or nanocellulose, with its solid byproduct serving as a biosorbent for wastewater treatment. | Mamane et.al., 2021 |

| 7. | CN112844324A (2021-05-28) | Lignin/manganese oxide composite adsorption material and preparation method and application |

Univ Nnajing Sci & Tech | A cost-effective and energy-efficient method for synthesizing a lignin/manganese oxide composite adsorbent. The material demonstrates high adsorption capacity for dye-contaminated wastewater and is amenable to scale-up, indicating strong applicability for industrial dye effluent treatment. |

Jin et.al., 2021 |

| S.No. | Application | Description | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Nano pesticides | EB@CPG cellulose-based nano pesticide; non-toxic to seed germination with high insecticidal activity; also utilized as an organic N-fertilizer (boosted plants’ fresh weight by 39.77%). | (Zhao et al., 2022) |

| 2. | Oil-spills clean-up | Guar-gum esterified lignin aerogel with high porosity values (>95%), low density (27.4 mg/cm3) and great absorbing capacity for sunflower oil (32.5g/g) | (Montazeri & Norouzbeigi, 2024) |

| 3. | Recovery and removal of rare earth elements | Magnetic grass nano-cellulose from Cyperus rotundus showed high absorption capacity of 353.04 mg/g for the removal of Ce+3. | (Shahnaz et al., 2022) |

| 4. | Antioxidant | Lignin-incorporated nanogel formulation (extracted from coconut husk) showed strong antioxidant activity i.e., IC50 = 25.7 ppm, reduced ROS level and enhanced wound healing in mice. | (Xu et al., 2021) |

| 5. | Drug-delivery | Curcumin-loaded NP formulation (104nm) with enhanced the stability and effectiveness; increased bioavailability of drug upon oral administration. | (Wijaya et al., 2021) |

| 6. | Tissue engineering | The alkaline phosphatase activity test revealed that LgNP/PCL nanofiber scaffolds significantly promoted osteogenic differentiation in MC3T3-E1 cells compared to clean PCL nanofibers. | (Haider et al., 2023) |

| 7. | Stabilizer and dispersant | LgNPs, having uniform particles and avg size of 41.1 ± 14.5 nm were synthesized. Emulsions (with olive oil) with a 3:7 volume ratio (oil-water) resulted in droplet diameters of 13.99 ± 4.82μm at pH 3.0, which also demonstrated long term storage stability (30days). This showed decorous valorization of kraft lignin. | (Wang et al., 2023) |

| 8. | Antimicrobial activity | Lignin-Zn hydroxide-based NPs derived from Litchi chinensis leaves showed antibacterial (against Bacillus subtilis), antioxidant (IC50= 45.22μg/ml) and in-vitro cytotoxicity (against HepG2 cells with 73.21% cell inhibition at 25.6μg/ml; IC50= 2.58 μg/ml.) | (Srivastava et al., 2023) |

| 9. | Food packaging | Bio-nanofiller composite significantly decreased peroxide value (POV), acid value (AV) and saponification value (SV) therefore showed an oxidative delay in rancidity of soyabean oil. | (Sun et al., 2023) |

| 10. | UV Absorbents | Highly stable lignin-polyvinyl alcohol NPs with ~13nm diameter, enhanced the UV-shielding by 13.3% at 250nm wavelength. | (Ju et al., 2019) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).