Submitted:

14 June 2025

Posted:

16 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

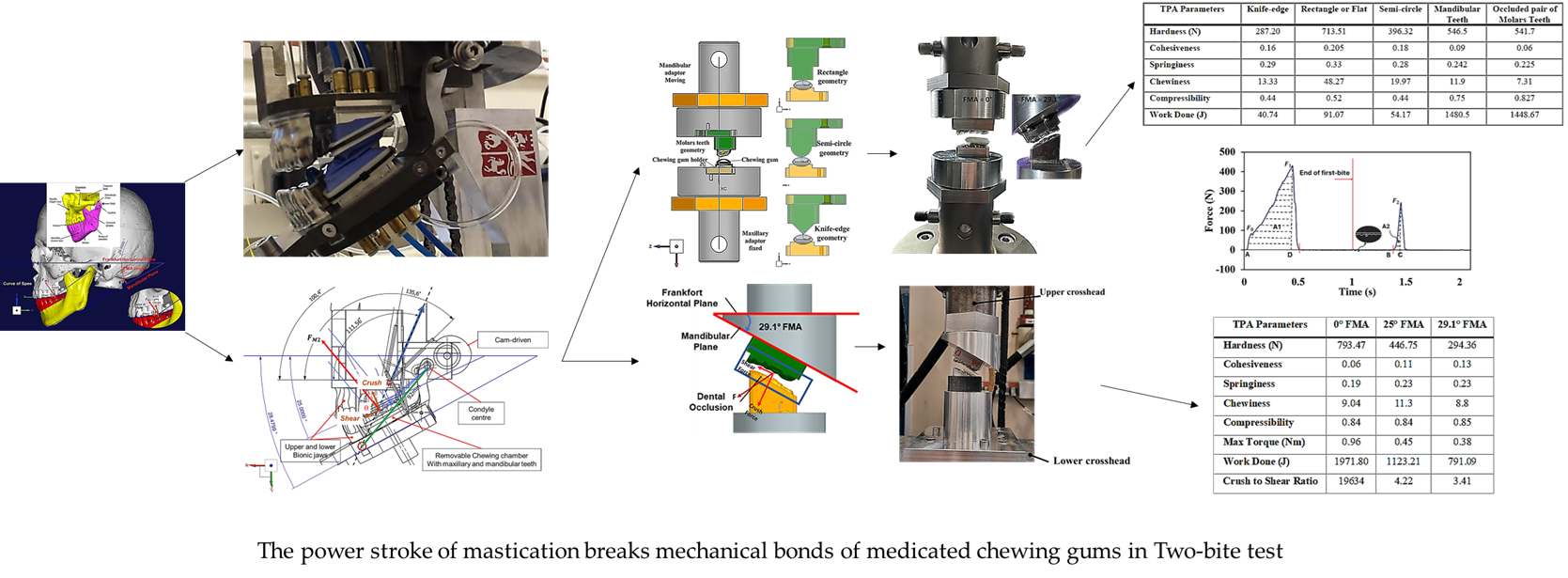

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

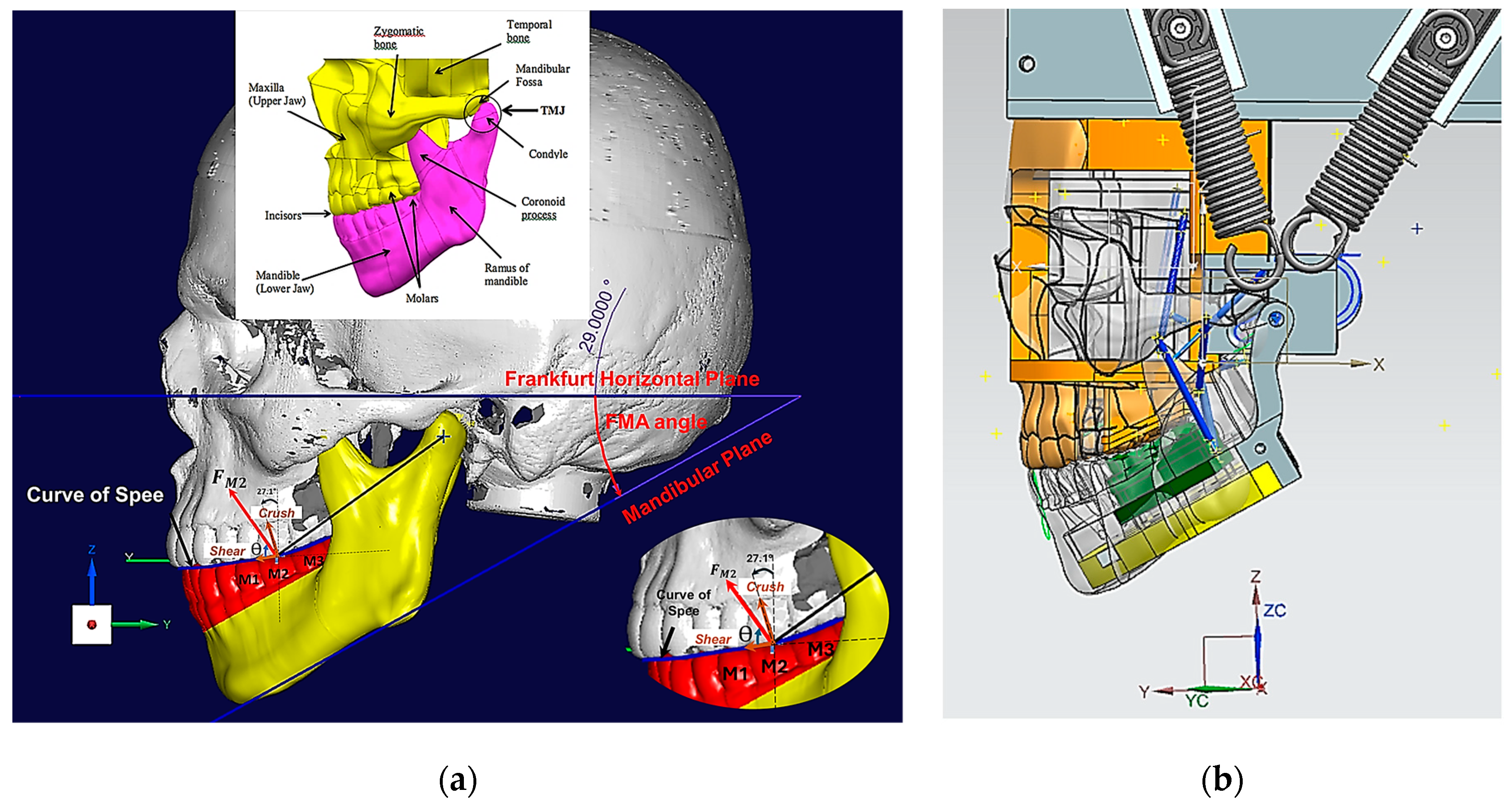

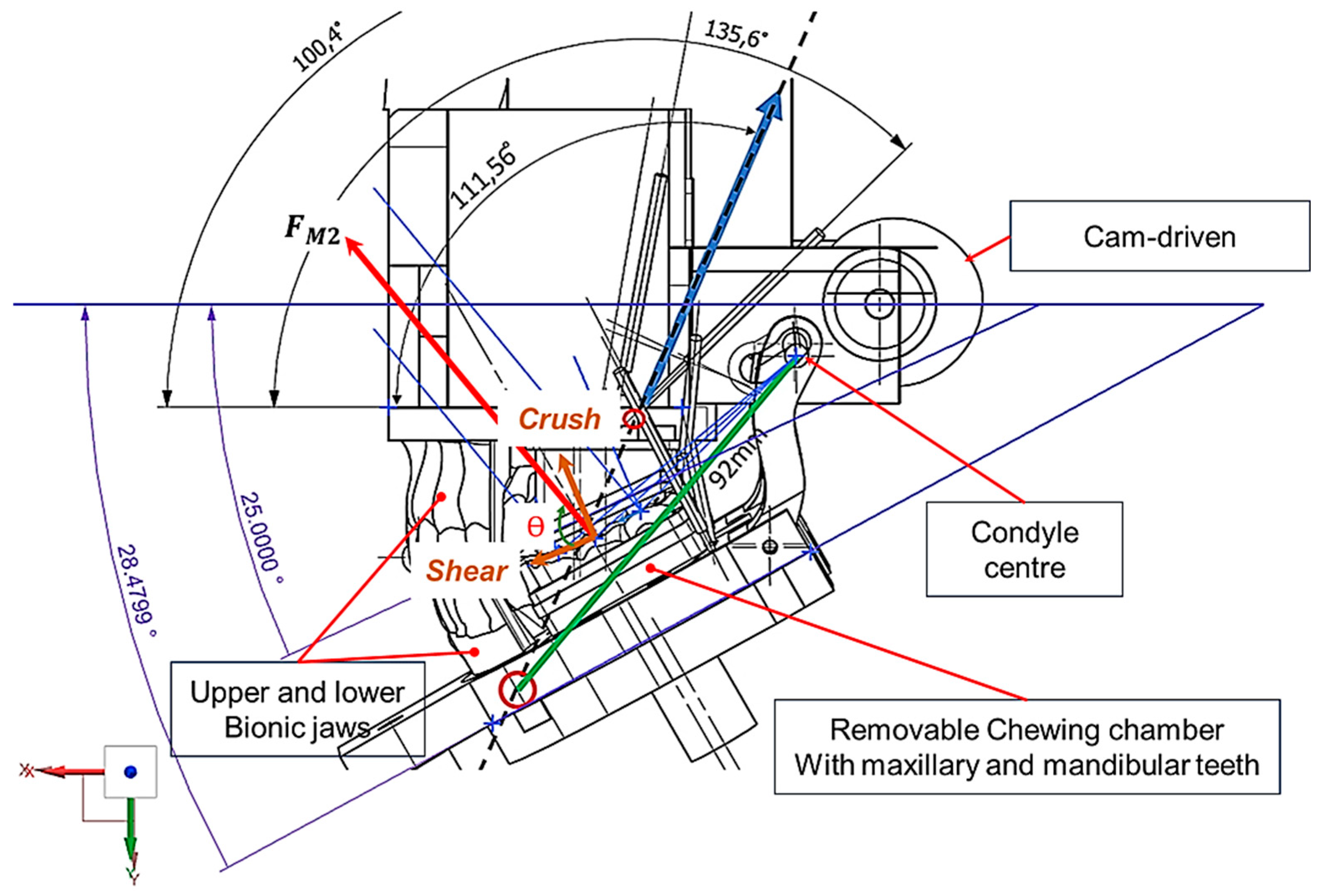

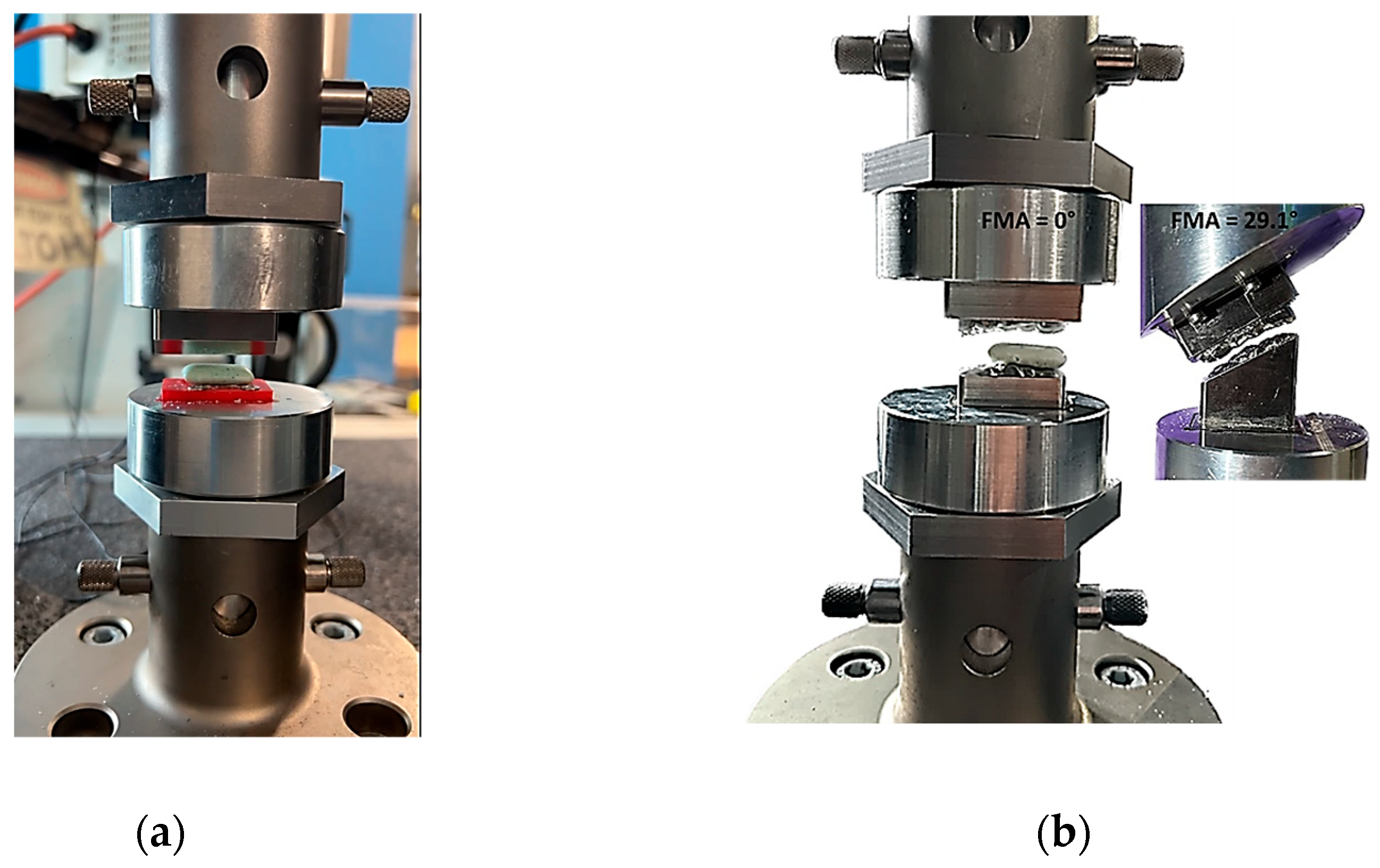

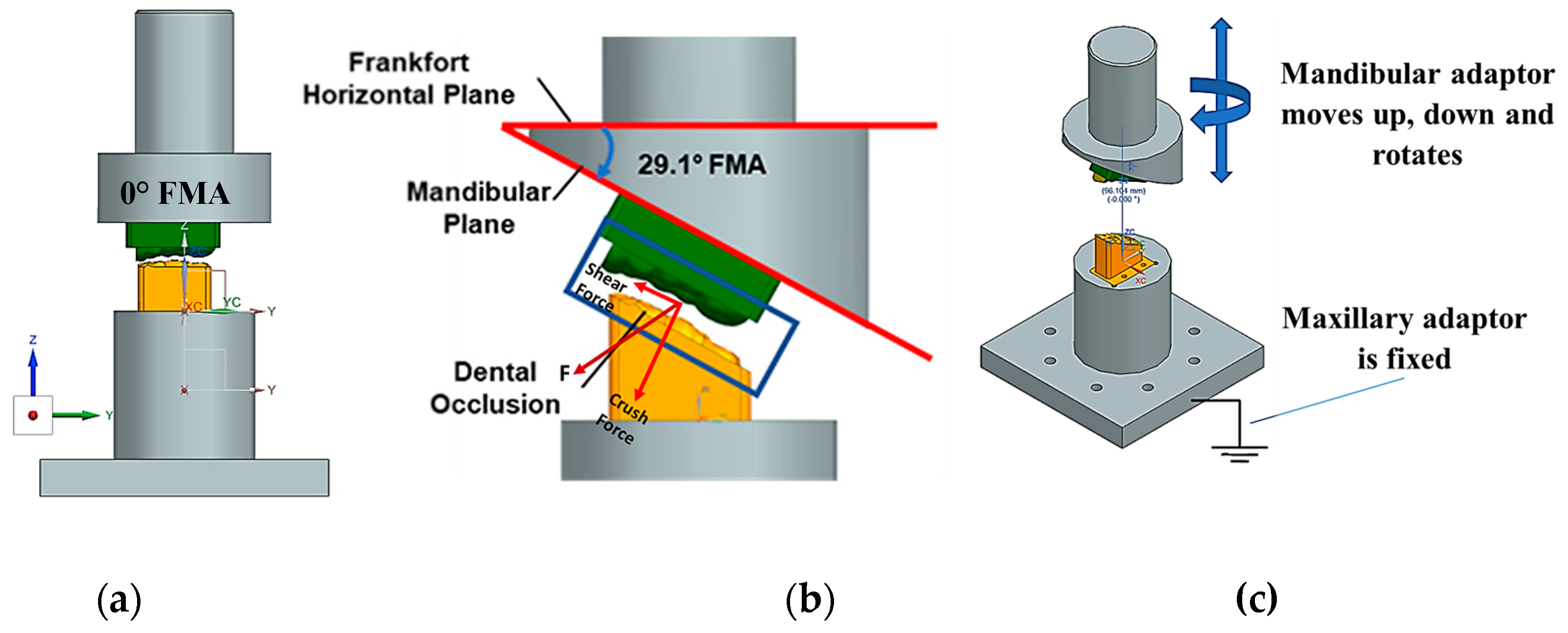

2.1. Design and Modelling of Maxillary-Mandibular-Bio Testbed

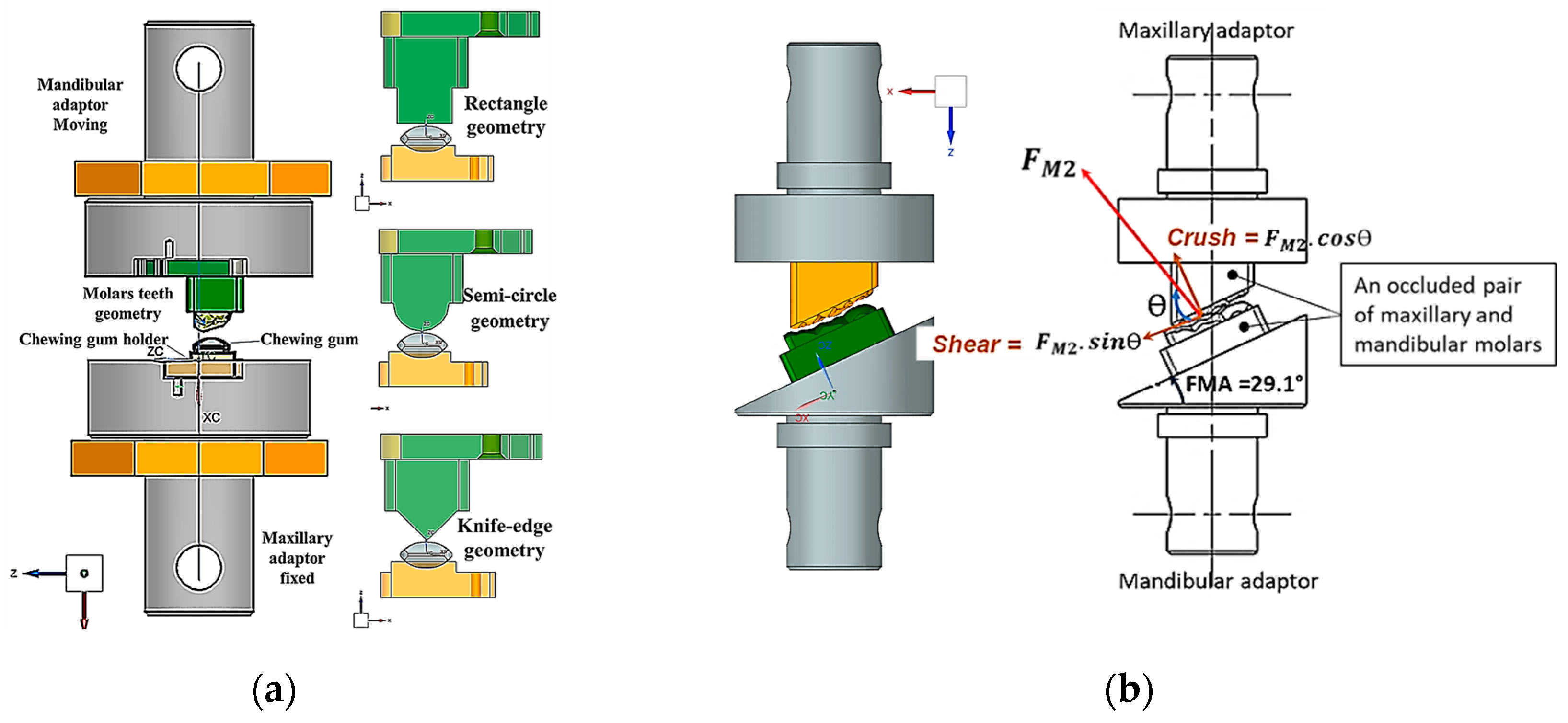

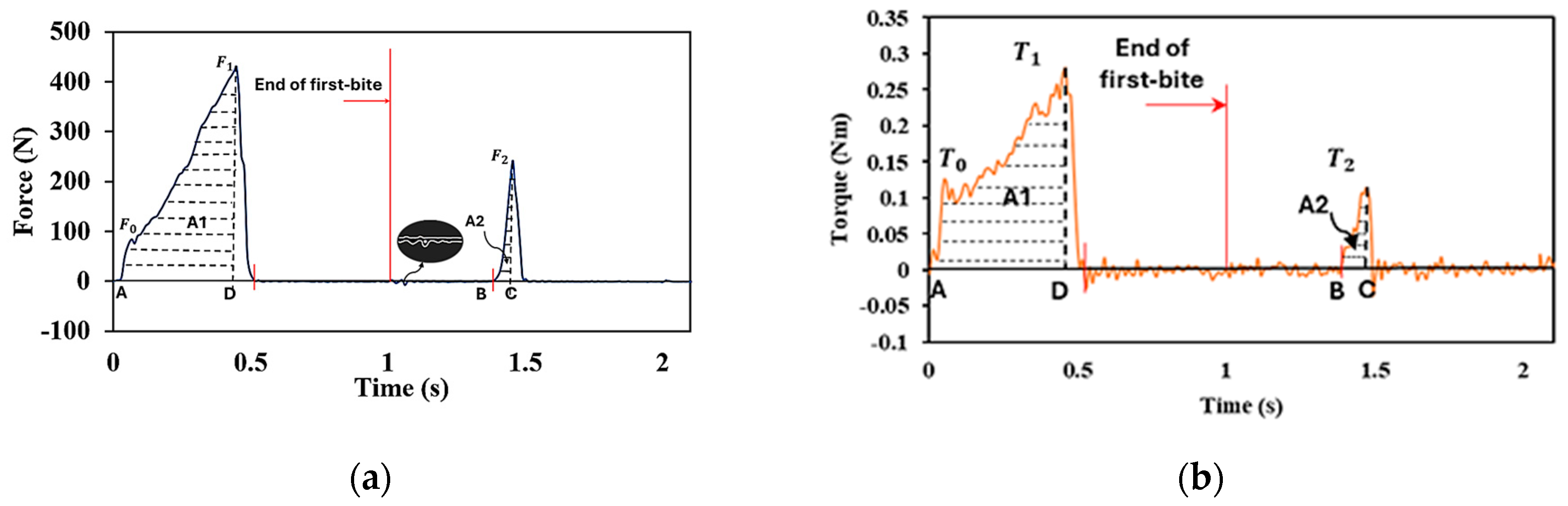

2.2. Two-Bite Test – Texture Profile Analysis (TPA)

- Section 1 - Bio-inspired design principles

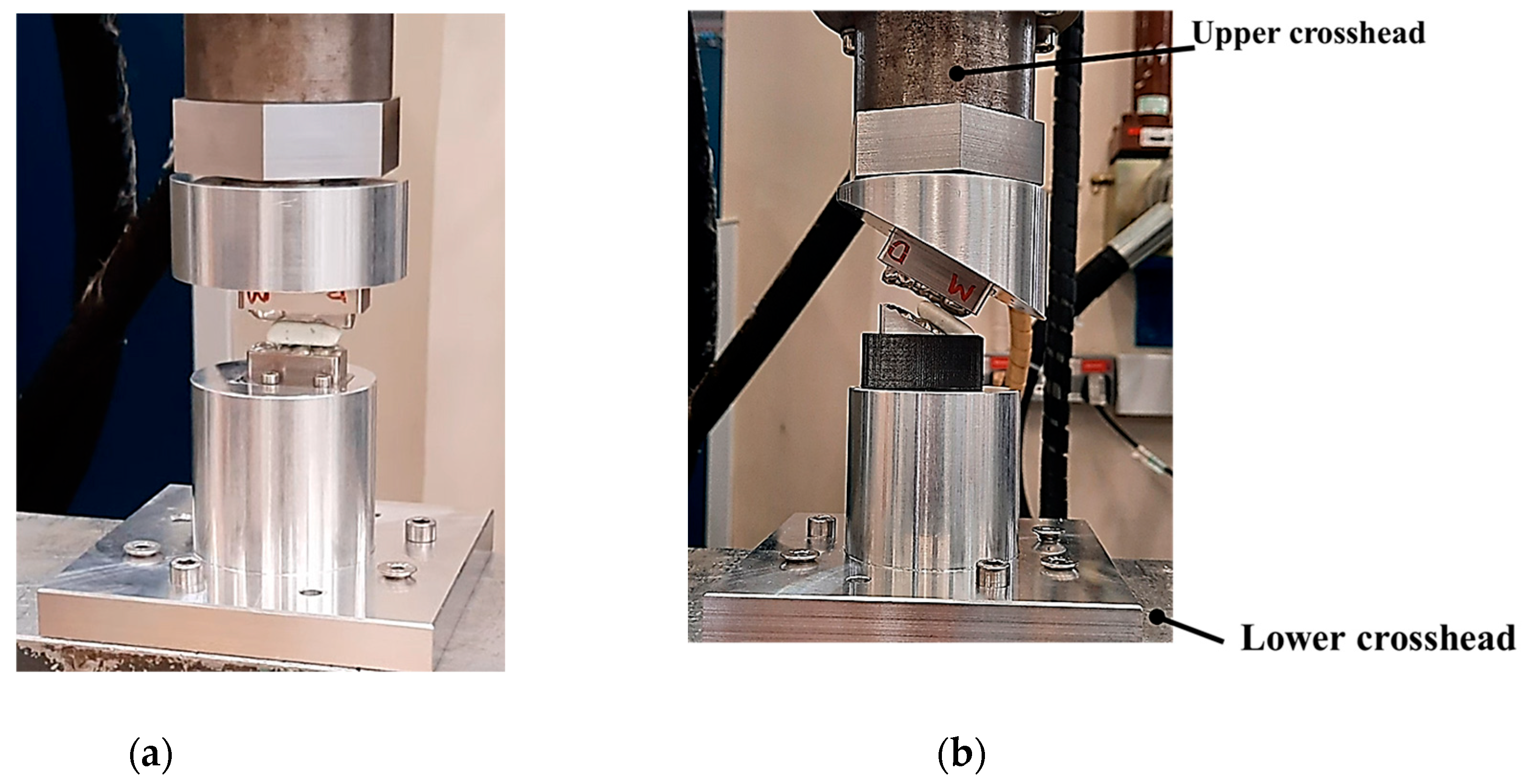

- Section 2 - Instron set-ups

- Section 3 - Zwick-Roell set-ups

3. Results

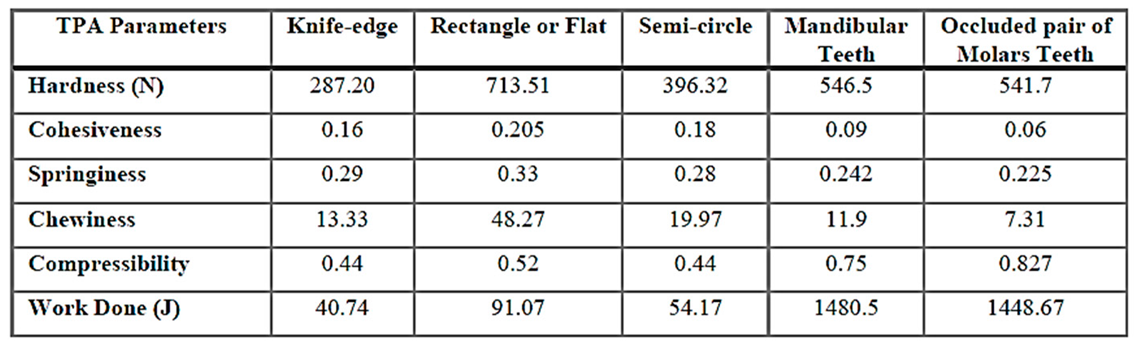

3.1. Set-Up A: Instron Using 10 mm/s Compression and FMA = 0 to Evaluate Tooth Morphologies (Including an Occluded Pair of Molars)

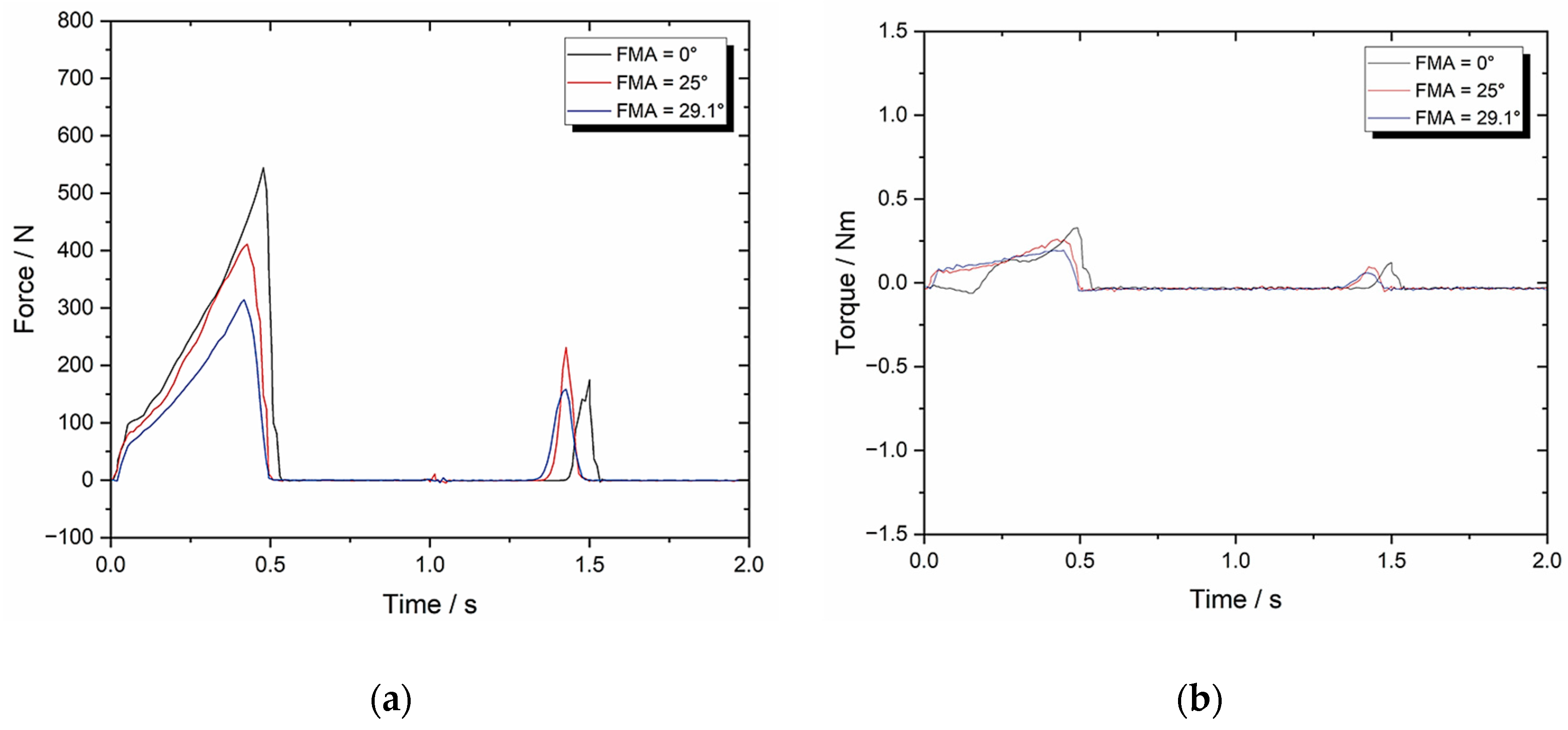

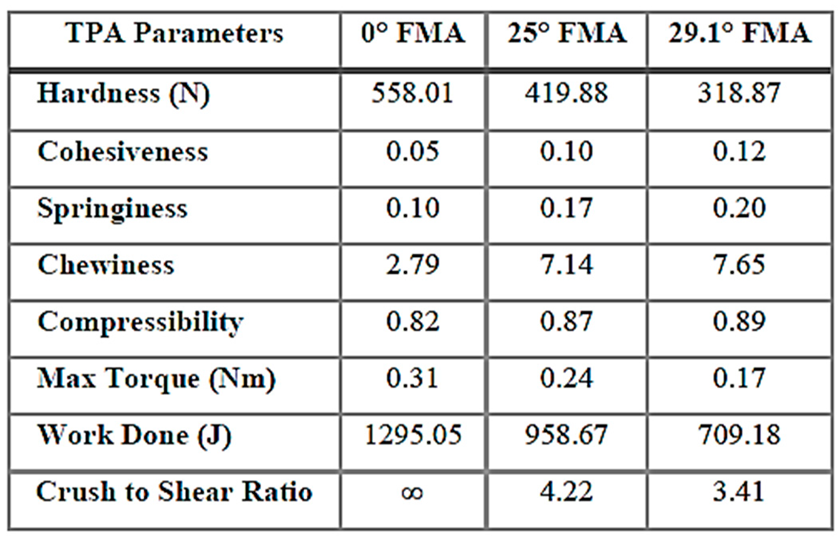

3.2. Set-Up B: Zwick-Roell Using 10 mm/s Compression and BA = 0 Whilst Varying FMA

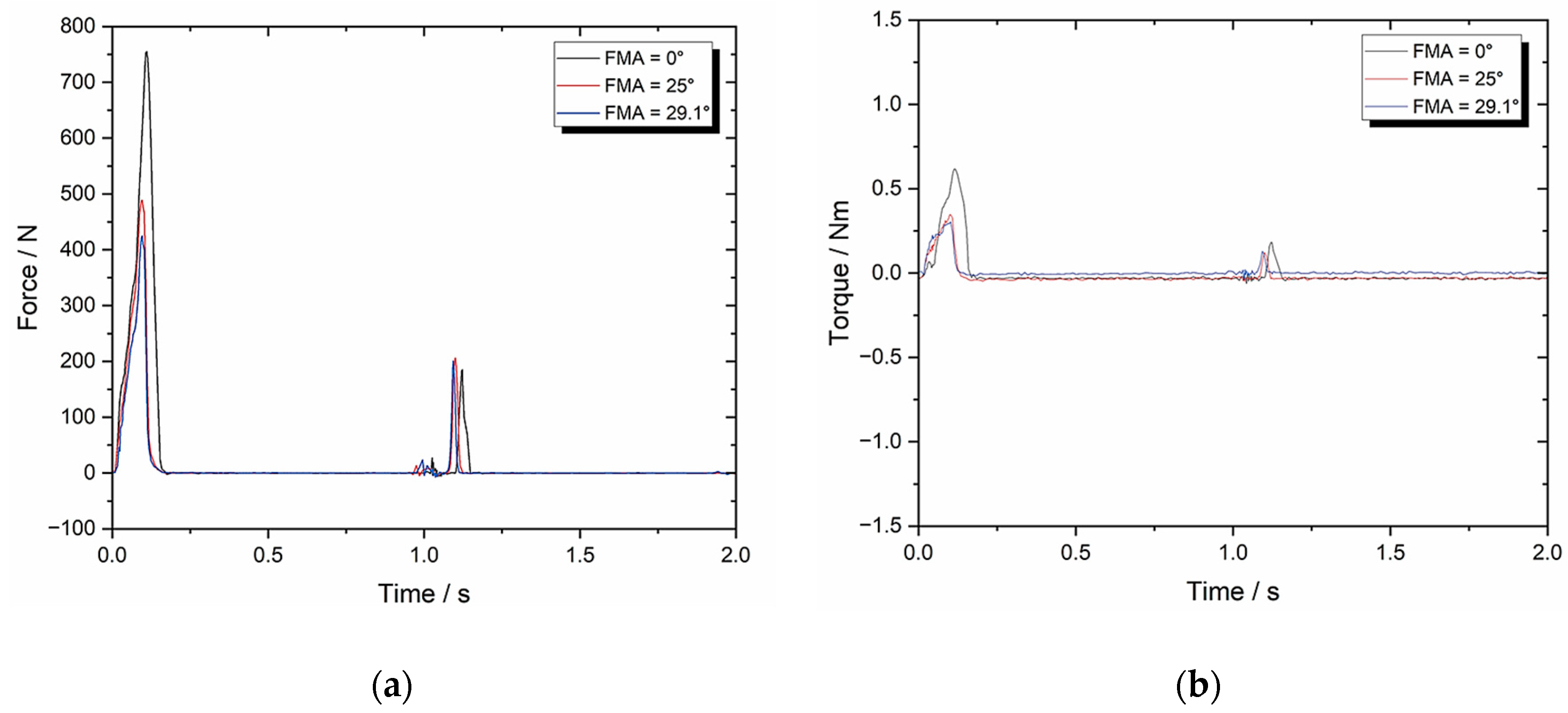

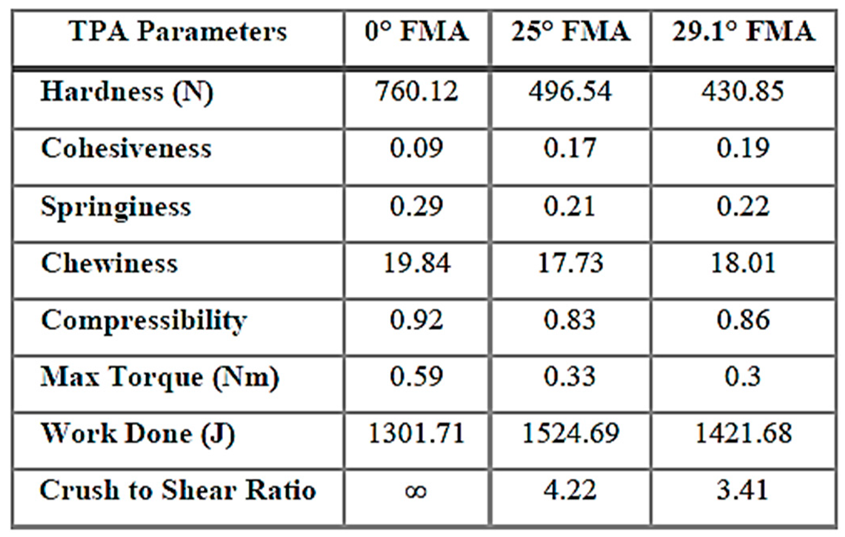

3.3. Set-Up C: Zwick-Roell Using 49.5 mm/s Compression and BA = 0 Whilst Varying FMA (to Emulate Human Chewing Speed)

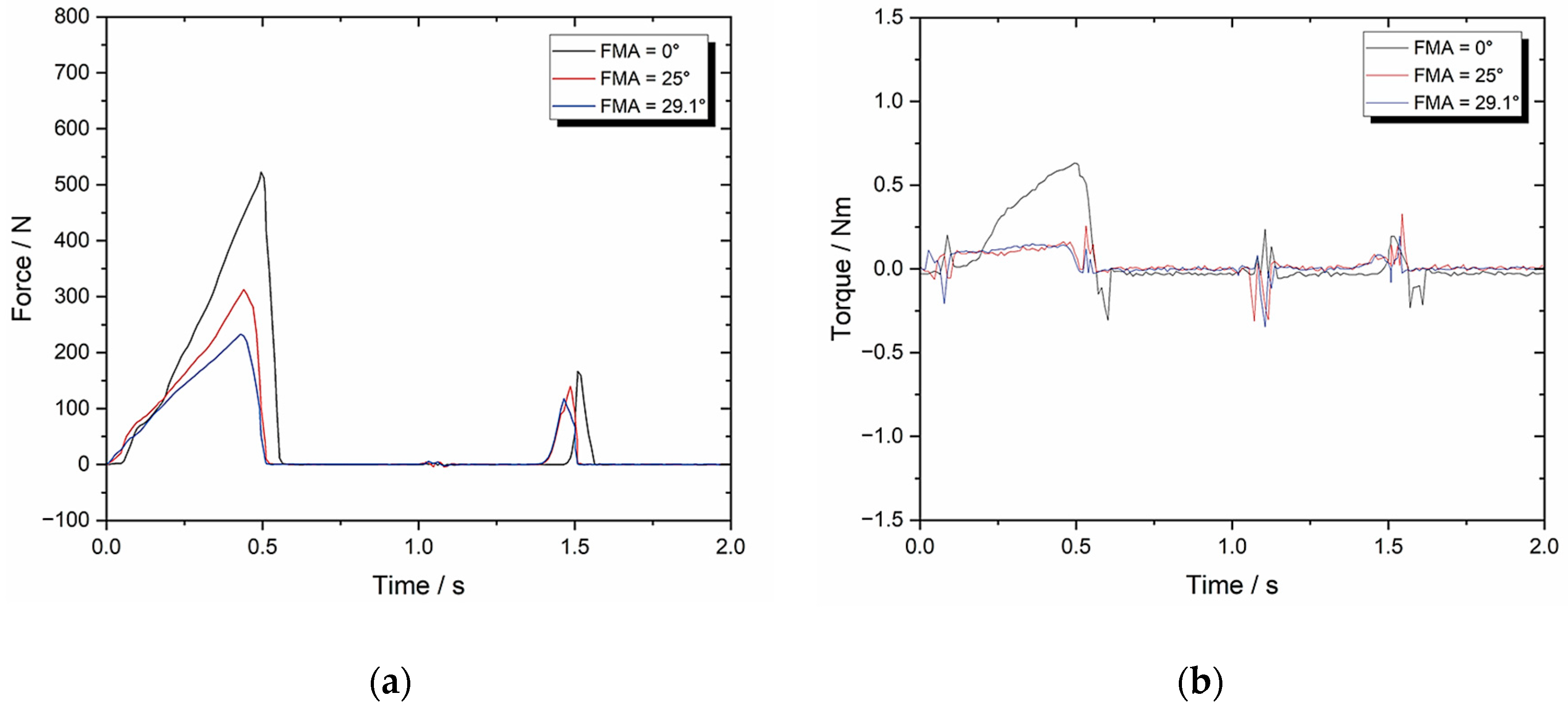

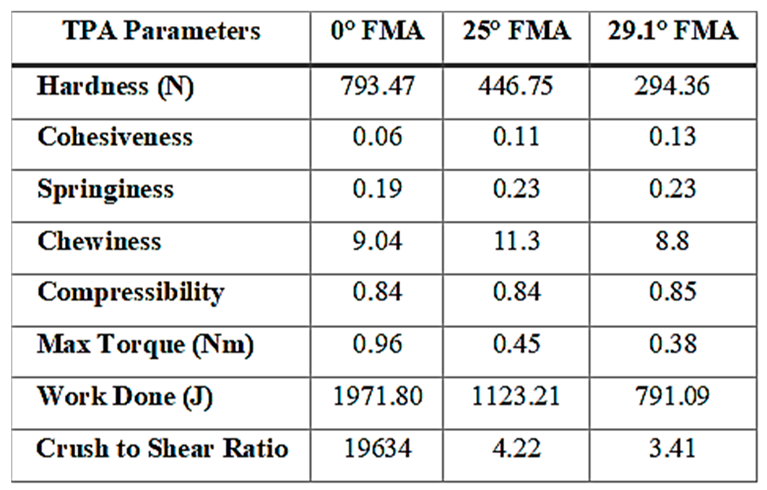

3.4. Set-Up D: Zwick-Roell Using 10 mm/s Compression and BA = 8 Whilst Varying FMA (to Evaluate the Change in BA)

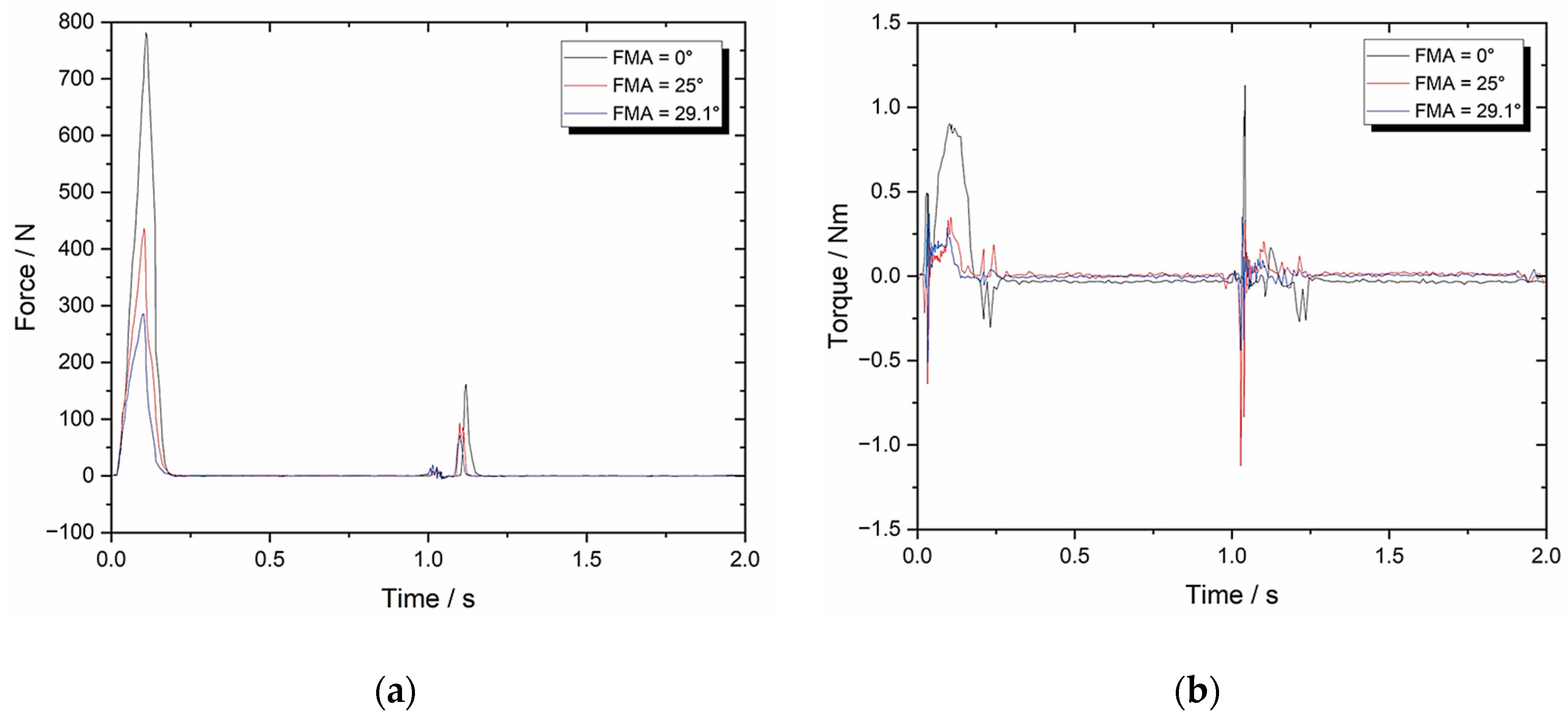

3.5. Set-Up E: Zwick-Roell Using 49.5 mm/s Compression and BA = 8 Whilst Varying FMA (to Emulate Human Chewing Speed)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

6. Patents

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MCG | Medicated chewing gum |

| PLM | Product lifecycle management |

| API | Active pharmaceutical ingredient |

| BA | Bennett angle of mandible |

| FMA | Frankfort-mandibular plane angle |

| CUR | Curcumin |

| TPA | Texture profile analysis |

| CeA | Cephalometric analysis |

| FHP | Frankfurt Horizontal plane |

| MP | Mandibular Plane |

| ART | Artificial Resynthesis Technology |

| CNS | Central-Nervous-System |

| POC | Proof of Concept |

| CPP-ACP | Casein Phosphopeptide-Amorphous Calcium Phosphate |

| CUR | Curcumin |

References

- Alemzadeh, K. and Raabe, D., Prototyping artificial jaws for the robotic dental testing simulator. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. H. 2008, 222(8), pp. 1209–1220. [CrossRef]

- Grau, A., Stawarczyk, B., Roos, M., Theelke, B. and Hampe, R., Reliability of wear measurements of CAD-CAM restorative materials after artificial aging in a mastication simulator. J. Mech.Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2018, 86, pp. 185–190. [CrossRef]

- Steiner, M., Mitsias, M.E., Ludwig, K. and Kern, M., In vitro evaluation of a mechanical testing chewing simulator. Dent. Mater. 2009, 25(4), pp. 494–499. [CrossRef]

- Morell, P., Hernando, I. and Fiszman, S.M., Understanding the relevance of in-mouth food processing. A review of in vitro techniques. Trends Food Sci. Tech. 2014, 35(1), pp. 18–31. [CrossRef]

- Peyron, M.A. and Woda, A., An update about artificial mastication. Food Sci. 2016, 9, pp. 21–28. [CrossRef]

- Salles, C., Tarrega, A., Mielle, P., Maratray, J., Gorria, P., Liaboeuf, J. and Liodenot, J.J., Development of a chewing simulator for food breakdown and the analysis of in vitro flavor compound release in a mouth environment. J. Food Eng. 2007, 82(2), pp. 189–198. [CrossRef]

- Woda, A., Mishellany-Dutour, A., Batier, L., François, O., Meunier, J.P., Reynaud, B., Alric, M. and Peyron, M.A., Development and validation of a mastication simulator. J. Biomechanics, 2010, 43(9), pp. 1667–1673. [CrossRef]

- Christrup, L.L. and Moeller, N., Chewing gum as a drug delivery system. Arch. Pharm. Chem. Sci. Ed. 1986, 14, pp. 30–36.

- Kvist, C., Andersson, S.B., Fors, S., Wennergren, B. and Berglund, J., Apparatus for studying in vitro drug release from medicated chewing gums. International journal of pharmaceutics, Int. J. Pharm. 1999, 189(1), pp. 57–65. [CrossRef]

- Alemzadeh, K., Jones, S.B., Davies, M. and West, N., Development of a chewing robot with built-in humanoid jaws to simulate mastication to quantify robotic agents release from chewing gums compared to human participants. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 2020, 68(2), pp492-504. [CrossRef]

- Vincent, J., Biomimetics with Trade-Offs. Biomimetics, 2023, 8(2), p.265. [CrossRef]

- Swiderski, D.L. and Zelditch, M.L., Complex adaptive landscape for a “Simple” structure: The role of trade-offs in the evolutionary dynamics of mandibular shape in ground squirrels. Evolution, 2022, 76(5), pp.946-965. [CrossRef]

- Heintze, S.D., Reichl, F.X. and Hickel, R., Wear of dental materials: Clinical significance and laboratory wear simulation methods—A review. Dent. Mater. J. 2019, 38(3), p.343-353. [CrossRef]

- Krueger, K.L., Chwa, E., Peterson, A.S., Willman, J.C., Fok, A., van Heel, B., Heo, Y., Weston, M. and DeLong, R., Artificial Resynthesis technology for the experimental formation of dental microwear textures. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 2021, 176(4), pp.703-712. [CrossRef]

- Daegling, D.J., Hua, L.C. and Ungar, P.S., The role of food stiffness in dental microwear feature formation. Arch. Oral Biol. 2016, 71, pp.16-23. [CrossRef]

- Pu, D., Shan, Y., Wang, J., Sun, B., Xu, Y., Zhang, W. and Zhang, Y., Recent trends in aroma release and perception during food oral processing: Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2024, 64(11), pp.3441-3457. [CrossRef]

- Krause, A.J., Henson, L.S. and Reineccius, G.A., Use of a chewing device to perform a mass balance on chewing gum components. Flavour Fragr. J. 2011, 26 (1), pp.47–54. [CrossRef]

- Peyron, M.A., Santé-Lhoutellier, V., Dardevet, D., Hennequin, M., Remond, D., François, O. and Woda, A., Addressing various challenges related to food bolus and nutrition with the AM2 mastication simulator. Food Hydrocoll. 2019, 97, p.105229. [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y., Zhao, Q., Li, T. and Mao, Q., Masticatory simulators based on oral physiology in food research: A systematic review. J. Texture Stud. 2024, 55(5), p.e12864. [CrossRef]

- Walker, A.E., Guy, F., Salles, C., Thiery, G. and Lazzari, V., Assessment of comminution capacity related to molar intercuspation in catarrhines using a chewing simulator. BMSAP, 2022, 34(34 (2)).

- Lucas, P.W., Corlett, R.T. and Luke, D.A., Postcanine tooth size and diet in anthropoid primates. Z. Morphol. Anthropol. 1986, pp. 253-276. [CrossRef]

- Lucas, P.W., Dental functional morphology: how teeth work. Cambridge University Press, 2004.

- Berthaume, M.A., Dumont, E.R., Godfrey, L.R. and Grosse, I.R., The effects of relative food item size on optimal tooth cusp sharpness during brittle food item processing. J. R. Soc. Interface. 2014, 11(101), p.20140965. [CrossRef]

- Jeannin, C., Gritsch, K., Liodénot, J.J. and Grosgogeat, B., MARIO: the first chewing bench used for ageing and analysis the released compounds of dental materials. CMBBE. 2019, 22(sup1), pp.S62-S64, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Chen, B., Dhupia, J.S., Morgenstern, M.P., Bronlund, J.E. and Xu, W., Development of a biomimetic masticating robot for food texture analysis. J. Mech. Robot. 2022, 14(2), p.021012. [CrossRef]

- Rathbone, M.J., Şenel, S. and Pather, I., Design and development of systemic oral mucosal drug delivery systems. Oral Mucosal Drug Delivery and Therapy, 2015, pp.149-167.

- Wanasathop, A. and Li, S.K., Iontophoretic drug delivery in the oral cavity. Pharm. 2018, 10(3), p.121. [CrossRef]

- Al Hagbani, T. and Nazzal, S., Medicated chewing gums (MCGs): composition, production, and mechanical testing. AAPS PharmSciTech, 2018, 19(7), 2908-2920. [CrossRef]

- Rassing, M.R., Chewing gum as a drug delivery system. Adv. Drug. Deliv. Rev. 1994, 13(1-2), pp.89-121. [CrossRef]

- Ferrazzano, G.F., Cantile, T., Coda, M., Alcidi, B., Sangianantoni, G., Ingenito, A., Di Stasio, M. and Volpe, M.G., In vivo release kinetics and antibacterial activity of novel polyphenols-enriched chewing gums. Molecules, 2016, 21(8), p.1008. [CrossRef]

- Giacaman, R.A., Maturana, C.A., Molina, J., Volgenant, C. and Fernández, C.E., Effect of casein phosphopeptide-amorphous calcium phosphate added to milk, chewing gum, and candy on dental caries: a systematic review. Caries Res. 2023, 57(2), pp.106–118. [CrossRef]

- Kassebaum, N.J., Bernabé, E., Dahiya, M., Bhandari, B., Murray, C.J.L. and Marcenes, W., Global burden of untreated caries: a systematic review and metaregression. J. Dent. Res. 2015, 94(5), pp650-658. [CrossRef]

- GBD 2017 Oral Disorders Collaborators, Bernabe, E., Marcenes, W., Hernandez, C.R., Bailey, J., Abreu, L.G., Alipour, V., Amini, S., Arabloo, J., Arefi, Z. and Arora, A., Global, regional, and national levels and trends in burden of oral conditions from 1990 to 2017: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease 2017 study. J. Dent. Res. 2020, 99(4), pp.362–373.

- Aspirin Market Size, Share, Value and Forecast 2030, https://www.zionmarketresearch.com (accessed 31 /5/2025).

- Global Vitamin C Market Size & Share to Surpass $1.8 Bn by (https://www.globenewswire.com (accessed 31 /5/2025).

- Al Hagbani, T. and Nazzal, S., Curcumin complexation with cyclodextrins by the autoclave process: Method development and characterization of complex formation. Int. J. Pharm. 2017, 520(1-2), pp.173–180. [CrossRef]

- Al Hagbani, T., Altomare, C., Kamal, M.M. and Nazzal, S., Mechanical characterization and dissolution of chewing gum tablets (CGTs) containing co-compressed health in gum® and curcumin/cyclodextrin inclusion complex. AAPS PharmSciTech, 2018, 19, pp.3742-3750. [CrossRef]

- Daniell, H., Nair, S.K., Esmaeili, N., Wakade, G., Shahid, N., Ganesan, P.K., Islam, M.R., Shepley-McTaggart, A., Feng, S., Gary, E.N. and Ali, A.R., Debulking SARS-CoV-2 in saliva using angiotensin converting enzyme 2 in chewing gum to decrease oral virus transmission and infection. Mol. Ther. 2022, 30(5), pp.1966-1978. [CrossRef]

- Imfeld, T., Chewing gum—facts and fiction: a review of gum-chewing and oral health. Crit. Rev. Oral. Biol. Med. 1999, 10(3), pp.405-419. [CrossRef]

- Konar, N., Palabiyik, I., Toker, O.S. and Sagdic, O., Chewing gum: Production, quality parameters and opportunities for delivering bioactive compounds. Trends in food science & technology. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 55, pp.29-38. [CrossRef]

- Al Hagbani, T. and Nazzal, S., Development of postcompressional textural tests to evaluate the mechanical properties of medicated chewing gum tablets with high drug loadings. Journal of Texture Studies. J. Text. Stud. 2018, 49(1), pp.30-37. [CrossRef]

- Maslii, Y., Kolisnyk, T., Ruban, O., Yevtifieieva, O., Gureyeva, S., Goy, A., Kasparaviciene, G., Kalveniene, Z. and Bernatoniene, J., Impact of compression force on mechanical, textural, release and chewing perception properties of compressible medicated chewing gums. Pharm. 2021, 13(11), p.1808. [CrossRef]

- Monograph 2.9.25 (2012). In Ph.Eur.9.0.

- Stomberg, C., Kanikanti, V.R., Hamann, H.J. and Kleinebudde, P., Development of a new dissolution test method for soft chewable dosage forms. AAPS PharmSciTech. 2018, 18, pp.2446-2453. [CrossRef]

- Zieschang, L., Klein, M., Krämer, J. and Windbergs, M., In vitro performance testing of medicated chewing gums. Dissolut. Technol. 2018, 25 (3), pp.64-69. [CrossRef]

- [46] Externbrink, A., Sharan, S., Sun, D., Jiang, W., Keire, D. and Xu, X., An in vitro approach for evaluating the oral abuse deterrence of solid oral extended-release opioids with properties intended to deter abuse via chewing. Int. J. Pharm. 2019, 561:305-313. [CrossRef]

- Cai, F., Shen, P., Walker, G.D., Reynolds, C., Yuan, Y. and Reynolds, E.C., Remineralization of enamel subsurface lesions by chewing gum with added calcium. J. Dent. 2009, 37(10), pp.763-768. [CrossRef]

- Alemzadeh, K., Innovative Bionics Product Life-Cycle Management Methodology Framework with Built-In Reverse Biomimetics: From Inception to Clinical Validation. Biomimetics, 2025, 10(3), p.158. [CrossRef]

- Schreuders, F.K., Schlangen, M., Kyriakopoulou, K., Boom, R.M. and van der Goot, A.J., Texture methods for evaluating meat and meat analogue structures: A review. Food Control, 2021, 127, p.108103. [CrossRef]

- Al Hagbani, T., Altomare, C., Salawi, A. and Nazzal, S., D-optimal mixture design: Formulation development, mechanical characterization, and optimization of curcumin chewing gums using oppanol® B 12 elastomer as a gum-base. Int. J. Pharm. 2018, 553(1-2), pp.210-219.

- Bogdan, C., Hales, D., Cornilă, A., Casian, T., Iovanov, R., Tomuță, I. and Iurian, S., Texture analysis–A versatile tool for pharmaceutical evaluation of solid oral dosage forms. Int. J. Pharm. 2023, 638, p.122916. [CrossRef]

- Peleg, M., The instrumental texture profile analysis revisited. J. Texture Stud. 2019, 50(5), pp.362-368. [CrossRef]

- Benazzi, S., Grosse, I.R., Gruppioni, G., Weber, G.W. and Kullmer, O., Comparison of occlusal loading conditions in a lower second premolar using three-dimensional finite element analysis. Clin. Oral. Investig. 2014, 18, pp. 369–375. [CrossRef]

- Katona, T.R. and Eckert, G.J., The mechanics of dental occlusion and disclusion. Clin. Biomechanics, 2017, 50, pp. 84–91. [CrossRef]

- Katona, T.R., An engineering analysis of dental occlusion principles. Amer. J. Orthodontics Dentofacial Orthoped. 2009, 135(6), pp.696-e1.

- Katona, T.R., Engineering analyses of the link between occlusion and temporomandibular joint disorders. J. Stomat. Occ. Med. 2013, 6, pp. 16–21. [CrossRef]

- Katona, T.R., Isikbay, S.C. and Chen, J., An analytical approach to 3D orthodontic load systems. Angle Orthod. 2014, 84(5), pp. 830–838. [CrossRef]

- Bourdiol, P. and Mioche, L., Correlations between functional and occlusal tooth-surface areas and food texture during natural chewing sequences in humans. Archives Oral Biol., 2000, 45(8), pp.691-699. [CrossRef]

- Ungar, P.S., Mammalian dental function and wear: a review. Biosurf. Biotribol. 2015, 1(1), pp. 25–41. [CrossRef]

- Osborn, J.W., Relationship between the mandibular condyle and the occlusal plane during hominid evolution: some of its effects on jaw mechanics. Amer. J. Phy. Anthropol. 1987, 73(2), pp.193-207. [CrossRef]

- Osborn, J.W., Orientation of the masseter muscle and the curve of Spee in relation to crushing forces on the molar teeth of primates. Amer. J.Phys. Anthropol. 1993, 92(1), pp.99-106. [CrossRef]

- Fukoe, H., Basili, C., Slavicek, R., Sato, S. and Akimoto, S., Three-dimensional analyses of the mandible and the occlusal architecture of mandibular dentition. J. Stomat. Occ. Med. 2012, 5, pp. 119–129. [CrossRef]

- Cimić, S., Simunković, S.K. and Catić, A., The relationship between Angle type of occlusion and recorded Bennett angle values. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2016, 115(6), 729–735. [CrossRef]

- Andrews, L.F., The six keys to normal occlusion. Amer. J. Orthod. 1972, 62(3), pp.296-309. [CrossRef]

- Nam, S.E., Park, Y.S., Lee, W., Ahn, S.J. and Lee, S.P., Making three-dimensional Monson’s sphere using virtual dental models. J. Dent. 2013, 41(4), pp.336-344. [CrossRef]

- Spee, F.G., Biedenbach, M.A., Hotz, M. and Hitchcock, H.P., The gliding path of the mandible along the skull. J. Amer.Dent. Assoc. 1980, 100(5), pp.670-675. [CrossRef]

- Marshall, S.D., Caspersen, M., Hardinger, R.R., Franciscus, R.G., Aquilino, S.A. and Southard, T.E., Development of the curve of Spee. Amer. J. Orthod. Dentofacial. Orthop. 2008, 134(3), pp.344-352.

- Lynch, C.D. and McConnell, R.J., 2002. Prosthodontic management of the curve of Spee: use of the Broadrick flag. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2002, 87(6), pp.593-597. [CrossRef]

- Monson, G.S., 1932. Applied mechanics to the theory of mandibular movements. Dent. Cosmos. 1982, 74, pp. 1039–1053.

- Artificial Human Skull (Separates into 3 Parts). Available online: https://www.adam-rouilly.co.uk/product/po10-artificial-human-skull-separates-into-3-parts (accessed 31/5/2025).

- https://texturetechnologies.com/resources/texture-profile-analysis (accessed 31/5/2025).

- BOURNE, M.C., Texture measurement of individual cooked dry beans by the puncture test. J. Food Sci. 1972, 37(5), pp.751-753. [CrossRef]

- Rosenthal, A.J., Texture profile analysis–how important are the parameters?. Journal of texture studies, J. Text. Stud. 2010, 41(5), pp.672-684. [CrossRef]

- Madieta, E., Symoneaux, R. and Mehinagic, E., Textural properties of fruit affected by experimental conditions in TPA tests: an RSM approach. IJFST, 2011, 46(5), pp.1044-1052. [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.S., Al-Attabi, Z.H., Al-Habsi, N. and Al-Khusaibi, M., Measurement of instrumental texture profile analysis (TPA) of foods. Techniques to Measure Food Safety and Quality: Microbial, Chemical, and Sensory, 2021, pp.427-465.

- Nishinari, K. and Fang, Y., Perception and measurement of food texture: Solid foods. J. Texture Stud. 2018, 49(2), pp.160-201. [CrossRef]

- Paredes, J., Cortizo-Lacalle, D., Imaz, A.M., Aldazabal, J. and Vila, M., Application of texture analysis methods for the characterization of cultured meat. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12(1), p.3898. [CrossRef]

- Salejda, A.M., Janiewicz, U., Korzeniowska, M., Kolniak-Ostek, J. and Krasnowska, G., Effect of walnut green husk addition on some quality properties of cooked sausages. LWT-FOOD SCI. TECHNOL. 2016, 65, pp.751-757. [CrossRef]

- Florek, M., Junkuszew, A., Bojar, W., Skałecki, P., Greguła-Kania, M., Litwińczuk, A. and Gruszecki, T.M., Effect of vacuum ageing on instrumental and sensory textural properties of meat from Uhruska lambs. Ann. Anim. Sci. 2016, 16(2), pp.601-609. [CrossRef]

- Rapisarda, M., Valenti, G., Carbone, D.C., Rizzarelli, P., Recca, G., La Carta, S., Paradisi, R. and Fincchiaro, S., Strength, fracture and compression properties of gelatins by a new 3D printed tool. J. Food Eng. 2018, 220, pp.38-48. [CrossRef]

- I. Nitschke et al., “Validation of a New Measuring Instrument for the Assessment of Bite Force”. Diagnostics, 2023, 13(23), p.3498. [CrossRef]

- Saberi, F., Azmoon, E. and Nouri, M., Effect of thermal processing and mixing time on textural and sensory properties of stick chewing gum. Food Structure, 2019, 22, p.100129, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Mehta, F.F. and Trivedi, P., Formulation and characterization of biodegradable medicated chewing gum delivery system for motion sickness using corn zein as gum former. Trop. j. pharm. res. 2015, 4(5), pp.753-760. [CrossRef]

- Palabiyik, I., Güleri, T., Gunes, R., Öner, B., Toker, O.S. and Konar, N., A fundamental optimization study on chewing gum textural and sensorial properties: The effect of ingredients. Food Structure, 2020, 26, p.100155. [CrossRef]

- Jonkers, N., van Dommelen, J.A.W. and Geers, M.G.D., Intrinsic mechanical properties of food in relation to texture parameters. Mech. Time-Depend Mater. 2022, 26, 323–346. [CrossRef]

- Nishinari, K., Fang, Y. and Rosenthal, A., Human oral processing and texture profile analysis parameters: Bridging the gap between the sensory evaluation and the instrumental measurements. J. Texture Stud. 2019, 50(5), pp.369-380. [CrossRef]

- Foster, K.D., Woda, A. and Peyron, M.A., Effect of texture of plastic and elastic model foods on the parameters of mastication. J. Neurophysiol. 2006, 95(6), pp.3469-3479. [CrossRef]

- Adeleke, O.A. and Abedin, S., Characterization of Prototype Gummy Formulations Provides Insight into Setting Quality Standards. AAPS PharmSciTech. 2024, 25(6), p.155. [CrossRef]

- Lira-Morales, D., Montoya-Rojo, M.B., Varela-Bojórquez, N., González-Ayón, M., Vélez-De La Rocha, R., Verdugo-Perales, M. and Sañudo-Barajas, J.A., Dietary fiber and lycopene from tomato processing. In Plant Food by-Products: Industrial Relevance for Food Additives and Nutraceuticals (pp. 256-281). Apple Academic Press. 2018.

- Johnson, M., 2014. Overview of texture profile analysis, Modified October 2023, https://www.texturetechnologies.com/resources/texture-profile-analysis (accessed 31/5/2025).

- Noren, N.E., Scanlon, M.G. and Arntfield, S.D., Differentiating between tackiness and stickiness and their induction in foods. Trends Food Sci Technol. 2019, 88, pp.290-301. [CrossRef]

- Salahi, M.R., Mohebbi, M. and Razavi, S.M.A., Analyzing the effects of aroma and texture interactions on oral processing behavior and dynamic sensory perception: A case study on cold-set emulsion-filled gels containing limonene and menthol, Food Hydrocoll. 2024, 154, p.110128. [CrossRef]

- Simpson, G.G., Paleobiology of Jurassic mammals. Paleobiologica, 1933, 5, pp.127–158.

- Fiorenza, L., Nguyen, H.N. and Benazzi, S., Stress Distribution and Molar Macrowear in Pongo pygmaeus: A New Approach through Finite Element and Occlusal Fingerprint Analyses. Hum. Evol. 2015, 30(3-4), pp.215–226.

- Kay, R.F. and Hiiemae, K.M., 1974. Jaw movement and tooth use in recent and fossil primates. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 1974, 40(2):227–256. [CrossRef]

- DiPietro, G.J. and Moergeli Jr, J.R., Significance of the Frankfort-mandibular plane angle to prosthodontics. J. Prosthet. Dent. 1976, 36(6), pp.624-635.

- Kaushik, P., Mittal, V. and Kaushik, D., Unleashing the Potential of β–cyclodextrin Inclusion Complexes in Bitter Taste Abatement: Development, Optimization and Evaluation of Taste Masked Anti-emetic Chewing Gum of Promethazine Hydrochloride. AAPS PharmSciTech. 2024, 25(6), p.169.

- Xu, Y., Lv, B., Wu, P. and Chen, X.D., Creating similar food boluses as that in vivo using a novel in vitro bio-inspired oral mastication simulator (iBOMS-Ⅲ): The cases with cooked rice and roasted peanuts. Food Res. Int. 2024, 190, p.114630. [CrossRef]

- Market Segmentation by Product, News, Technavio https://www.prnewswire.com, Functional Chewing Gum Market size to increase by USD 3.15 Billion between 2023 to 2028 (accessed 31/5/2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).