Introduction

Aquaculture has increasingly become a key strategy for meeting the rising global demand for fish protein, contributing significantly to food security, livelihoods, and economic growth [

41]. However, the intensification of aquaculture systems has heightened their susceptibility to infectious diseases, which can severely compromise fish health, reduce productivity, and lead to substantial economic losses [

23]. Among the most pressing challenges for fish producers are bacterial pathogens [

15].

One of the major concerns in this regard is fish Mycobacteriosis, a chronic and progressive granulomatous disease that affects a broad range of fish species [

41]. Various species within the Mycobacterium genus cause this disease, with documented cases in wild, cultured, marine, brackish, and freshwater fish populations worldwide [

22,

46]

. Mycobacterium species are acid-fast, non-motile, free-living, and highly resilient bacteria capable of thriving in diverse environments, including water and soil [

23]. They can infect both aquatic animals and humans [

8,

16,

36,

41].

The most commonly detected mycobacterial species in fish include Mycobacterium marinum, M. gordonae, M. fortuitum, M. chelonae, M. aurum, M. parafortuitum, and M. triplex [

33]. Among these, the primary pathogens affecting fish are M. chelonae, M. fortuitum, and M. marinum [

17,

19,

25,

40,

41,

49]. Of particular concern is M. marinum, a slow-growing, non-tuberculous, acid-fast bacterium responsible for chronic granulomatous infections in fish and recognized as a zoonotic threat to humans [

18,

33]. This pathogen infects a wide range of freshwater and marine fish species, causing clinical signs such as lethargy, weight loss, exophthalmia, skin ulcers, and granulomatous lesions in organs including the liver, spleen, and kidneys [

38,

45]. Transmission typically occurs through the ingestion of contaminated feces or the carcasses of infected fish [

20,

35,

48]. M. marinum was initially described by Aronson (1926) in saltwater fish and has since been detected in numerous species, including Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) [

6], turbot (Scophthalmus maximus) [

13], and sea bass (Dicentrarchus labrax) [

4]. It is also widespread among ornamental fish, with [

41] reporting a prevalence of 41.7% in aquarium fish compared to 19.3% in environmental samples [

2,

15,

22,

34]. Factors such as high fish stocking density and frequent transfers between tanks further promote the spread of this pathogen [

21,

41].

The presence of granulomatous lesions containing acid-fast rods (AFRs), typically observed using Ziehl–Neelsen (ZN) staining, serves as a key diagnostic indicator of this disease [

33]. On gross examination, affected fish display grayish-white nodules within the liver, spleen, and kidneys. Microscopically, these granulomas are characterized by necrotic centers encircled by layers of epithelioid cells and peripheral fibrous tissue [

10,

15]. While acid-fast staining and histopathology provide useful diagnostic information, definitive identification of the causative agent requires bacterial culture and molecular approaches such as 16S rRNA gene sequencing [

44]. Nonetheless, diagnosis remains challenging due to the non-specific nature of clinical symptoms and the variability of diagnostic methodologies [

41].

Currently, there is no comprehensive synthesis that captures the gross and histopathological characteristics of M. marinum infections in aquaculture fish. Prevalence data are scattered across different regions and fish species, and variation in diagnostic methods, including culture, PCR, and histopathology, complicates cross-study comparisons. Few studies have established clear links between pathological findings, epidemiological patterns, and risk factors. Moreover, a global summary of the pathological features and prevalence of M. marinum in clinically diseased aquaculture fish is lacking.

This systematic review is designed to summarize and integrate existing knowledge on the gross and histopathological characteristics of M. marinum in clinically diseased fish from aquaculture systems. Estimate and analyze the infection prevalence across and assess the diagnostic methods employed in various studies and evaluate their reliability. Identify gaps in the current research and propose recommendations for future investigations into fish Mycobacteriosis. By addressing these objectives, the review aims to provide a critical evidence base that will benefit veterinarians, researchers, fish health specialists, and policymakers. The findings are expected to improve disease control strategies, diagnostic protocols, and public health safeguards in aquaculture systems globally.

Methodology

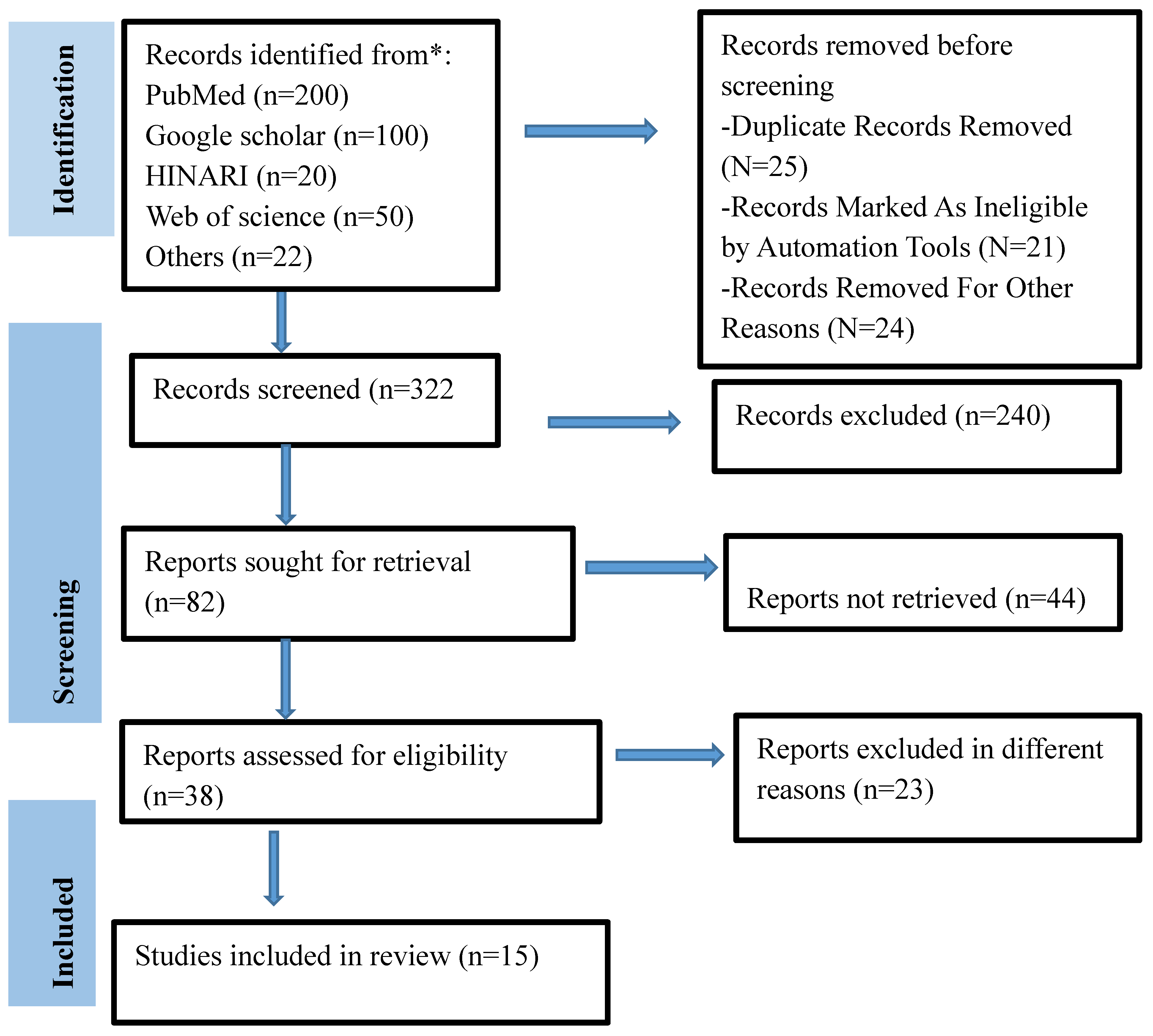

The systematic review was based on the STROBIE (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews) checklist (Supplementary file-1 STROBIE checklist for included cross-sectional studies). The checklists were used to confirm that relevant information from the selected articles had been included, in accordance with the protocols that were underlined.

Search Engine/Strategy

The STROBIE (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis) criteria served as the foundation for the systematic review (Supplementary file-1 STROBIE checklist for included cross-sectional studies). The checklists were utilized to verify that the pertinent information from the chosen publications was included in accordance with the specified procedures. The period of the literature search was March 20, 2025, to April 30, 2025. Two writers (M.A. and A.M.) independently developed a thorough search technique to find included studies. The literature searches were conducted using both manual techniques and databases, including PubMed, Web of Science, Google Scholar, and HINARI. What are the pathological characteristics and descriptions, the incidence of histological lesions in various organs, and the presence and detection of M. marinum in fish raised in aquaculture that are clinically ill? To find pertinent articles, the CoCoPop (Condition, Context, and Population) paradigm was used. Fishes (Pop) were the population, aquaculture (Co) was the context, and M. marinum (Co) was the condition. A variety of important keywords and Medical Subject Heading (MeSH) terms were included in the search strategy. The MeSH terms utilized at this time are pathology, fish infection with M. marinum, aquaculture, fish histopathology, cross-sectional study, and M. marinum. Following the integration of relevant terms and expressions, an online search was conducted using the Boolean operator "AND /OR." M. marinum OR M. marinum infection OR M. marinum AND (occurrence OR prevalence OR infection rate) AND (fishes OR fish species OR) AND histopathology OR AND fish bacterial disease in aquaculture were among the search terms that were employed. English was the only language available for publication. To eliminate duplication, all identified studies were imported into End-Note 20.

Criteria for Selection of Articles

When choosing pertinent studies, the following factors were crucial: all studies should have observational study designs, pathological descriptions should be included, and studies were chosen based on their specificity to M. marinum infection in fish, clinical cases, gaps, related objectives, related research questions, cross-sectional studies, case series, reports, published research papers in indexed journals, and aquaculture studies. All clinical case studies are selected based on the aforementioned criteria for pathological characteristics and the presence of M. marinum in clinically ill fish raised in aquaculture. The specimens that were cultivated, the papers that dictated M. marinum isolation and identification using standard bacteriology techniques, the fact that the research was conducted in aquaculture, and the fact that the study was published in English were all taken into consideration in their review work when they subsequently selected all positive cases. Publications and indexes that satisfied the previously indicated inclusion criteria were selected. Cohort and case control studies, non-clinical research, experimental research, traditional reviews, and outbreak reports were among the exclusion criteria. Finally, these inclusion and exclusion criteria (study screening strategy and grounds for exclusion) were used in the data extraction procedure (

Figure 1).

Quality Assessment and Evaluation of Study

The research protocols methodological quality and evidence strength in connection to the review question were assessed in this review using the AMSTAR-2 (Supplementary file-2) quality evaluation. The results of this systematic review and meta-analysis are based on the quality assessment of the included studies (

https://drive.google.com/file/d/186it7bH).

Data Synthesis and Statistical Analysis

Based on the papers that were examined, an estimate of the average prevalence/occurrence of M. marinum in clinical diseased fishes and frequency/prevalence of histological in different were made using the SPSS software version 25. To ascertain the average prevalence of M. marinum, a subgroup calculation was carried out, taking into account the degree taking into account the degree of M. marinum infection rate associated with the study years.

Throughout the investigation, the pathological characteristics and infection prevalence of M. marinum in clinically ill fish raised in aquaculture changed. Additionally, research year categories were developed based on the pooled papers, such as (≤2010), (2011–2014), and (≥2015).

Discussion

In aquaculture, non-tuberculous mycobacteria (NTM) are important pathogens, causing a disease often referred to as Mycobacteriosis or fish tuberculosis [

27,

29]. M. marinum is the most common species associated with fish infections [

24,

46]. M. marinum is a slow-growing, non-tuberculous, acid-fast bacterium known for causing chronic granulomatous infections in fish and posing zoonotic risks to humans [

18]. This pathogen affects a wide variety of fish species [

38].

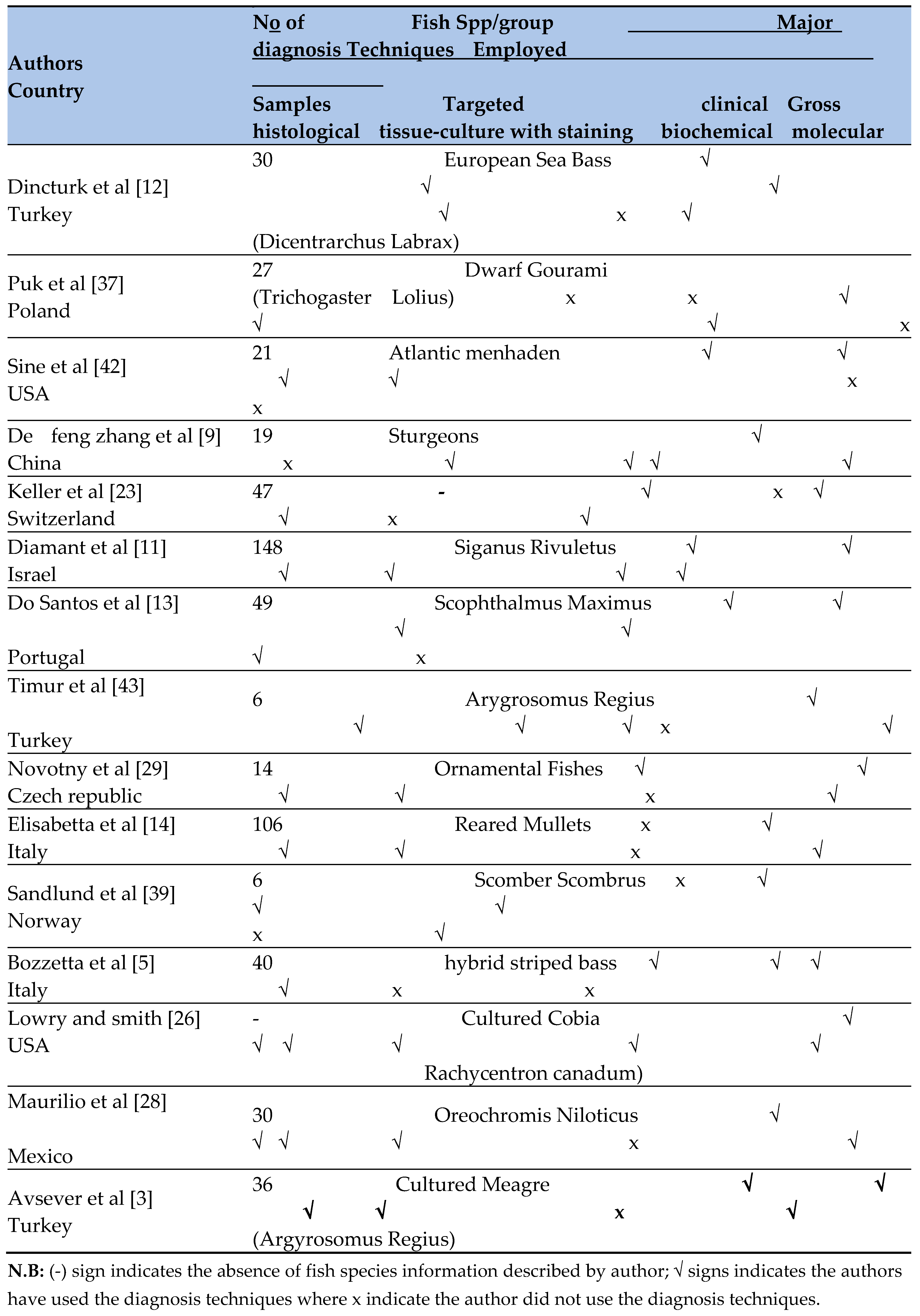

Regarding diagnostic techniques, the current systematic review found that most of the 15 included studies used a combination of clinical signs, gross lesions/necropsy findings, histological examination, tissue culturing with staining, and molecular techniques to diagnose and detect M. marinum in clinically diseased fish. The diagnosis of Mycobacteriosis in fish primarily relies on the gross examination of internal organs, which may show white granulomatous nodules [

3,

37]. However, culturing the bacteria on Middlebrook 7H10 or Löwenstein-Jensen (L-J) media is a crucial method for diagnosis and further biochemical and molecular identification [

22,

33]. Diagnosis was confirmed by culturing microorganisms from the kidney, spleen, and liver of affected fish using selective Löwenstein-Jensen medium, producing slow-growing yellow to orange colonies of the causative organisms, as described in previous reports [

22,

29].

Histopathology remains the most commonly used method for diagnosing fish Mycobacteriosis, while culture and PCR-based methods are required for species identification [

11]. Recent advancements in culturing and molecular techniques have led to more precise identification and characterization of Mycobacterium species [

29]. These methods confirmed M. marinum as the major cause of this disease in cultured fish [

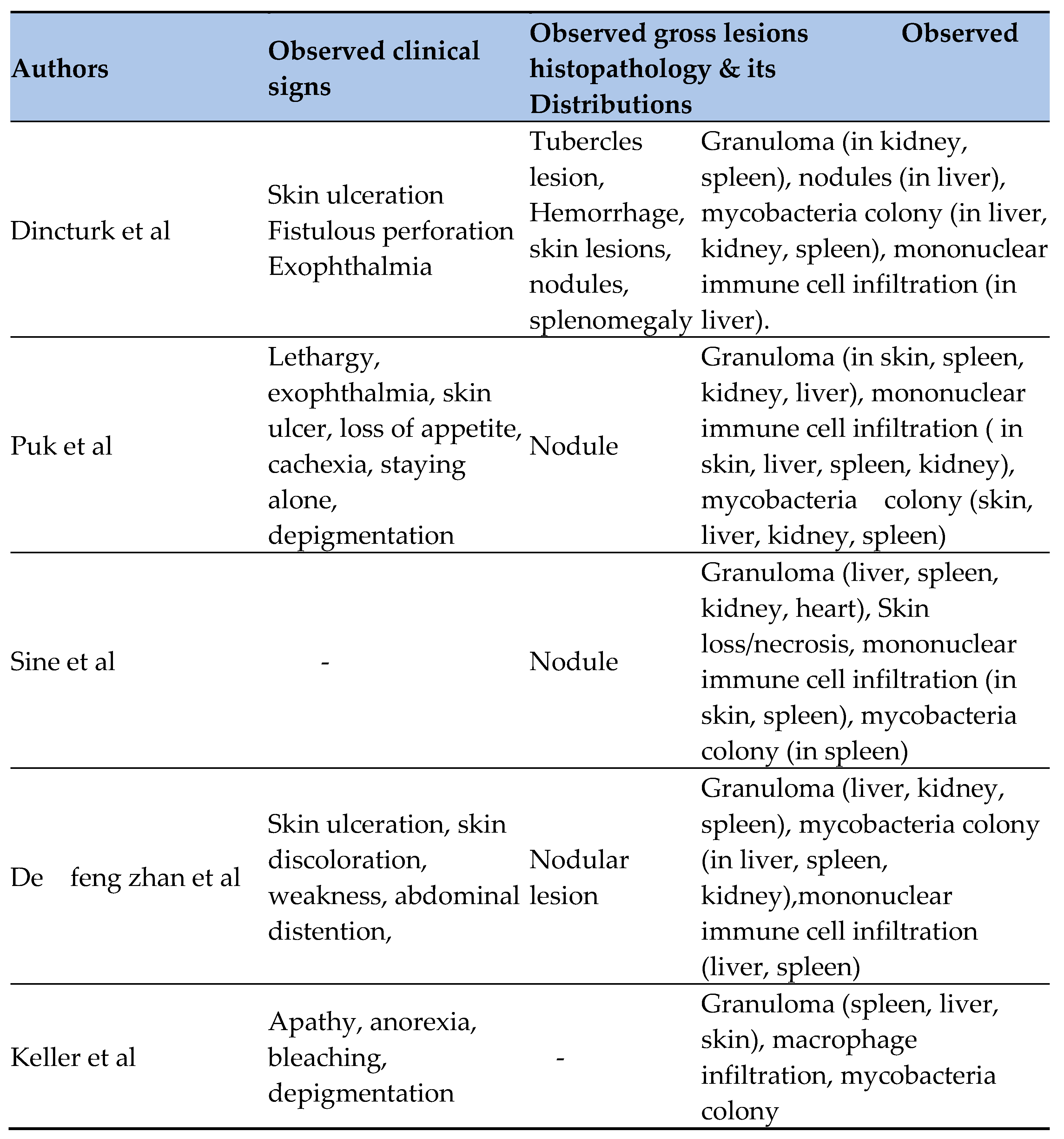

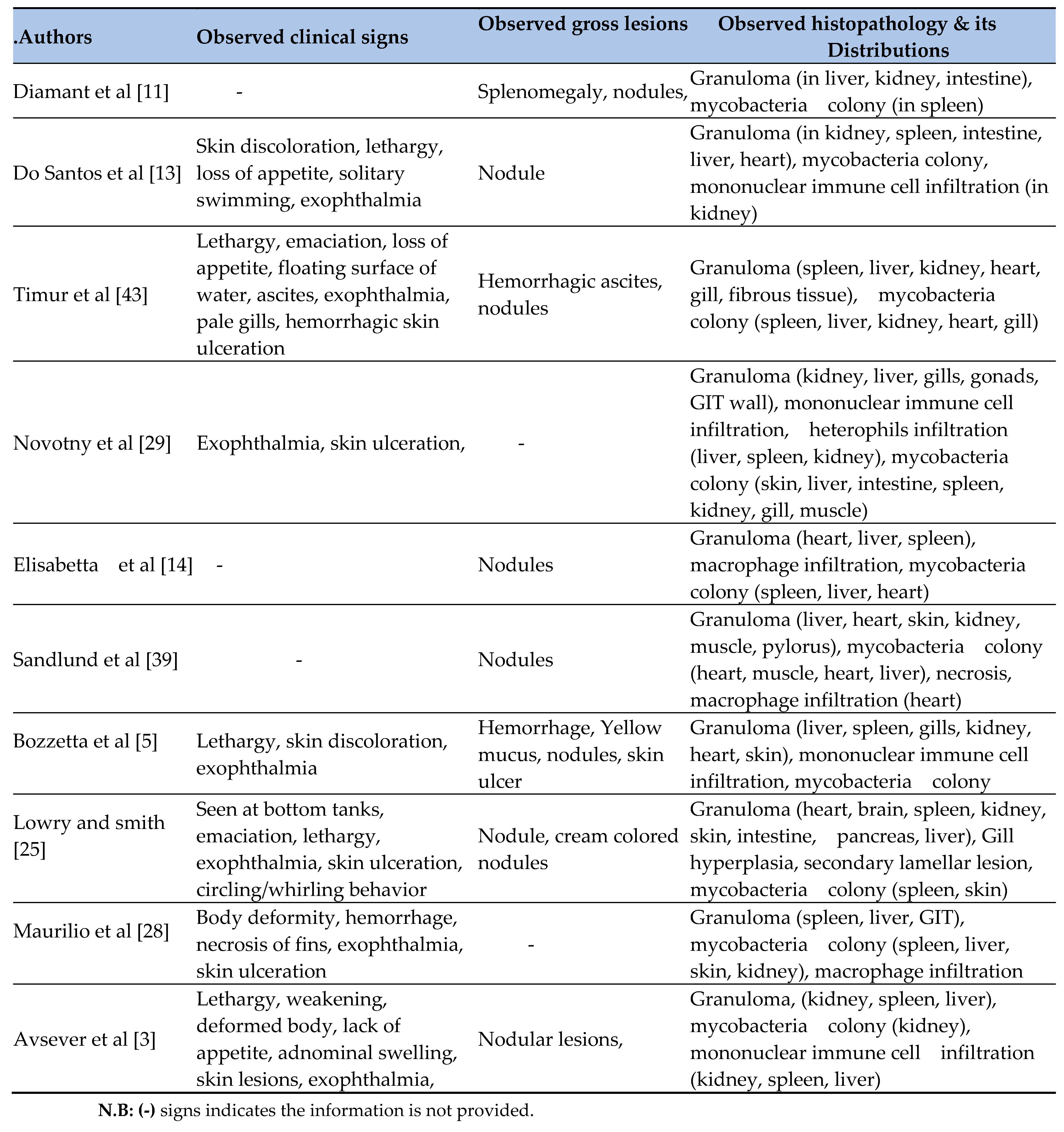

24]. The systematic review found that the most commonly reported clinical signs included skin lesions, lethargy, hemorrhage, exophthalmia, cachexia, isolation from other fish, depigmentation, weakness, abdominal distension or ascites, emaciation, and loss of appetite [

23] described clinical signs such as apathy, anorexia, and skin ulcerations [

4] observed skin lesions, cachexia, and paleness, while [

24] reported pale gills, exophthalmia, and fin hemorrhage in affected sea bass.

Figure 9.

(

a) Ulcerative dermal lesions (white arrow) [

4],

(b) Affected fish showed emaciation and stunted growth [

43].

Figure 9.

(

a) Ulcerative dermal lesions (white arrow) [

4],

(b) Affected fish showed emaciation and stunted growth [

43].

Figure 10.

(

a) Slight exophthalmia (white arrow), (

b) Hemorrhagic ulcerative skin lesions at the base of caudal fin (black arrow) [

43], (

c) Gills of hybrid striped bass: hemorrhagic lesions with yellow-brown nodules and mucus exudate (red arrow) [

5].

Figure 10.

(

a) Slight exophthalmia (white arrow), (

b) Hemorrhagic ulcerative skin lesions at the base of caudal fin (black arrow) [

43], (

c) Gills of hybrid striped bass: hemorrhagic lesions with yellow-brown nodules and mucus exudate (red arrow) [

5].

Figure 11.

(A-B) Necrotic areas on the ventral region (white arrows), (

C) hemorrhages in the ventral fins, (black arrow) (

D) different grades of skin lesions (black lines), (

E-F) tubercules in the spleen (red arrows), (

G) granulomas in heart (red arrow), (

H) enlarged spleen and liver (red and white arrows respectively), diffuse hemorrhage in liver (black arrow) [

12].

Figure 11.

(A-B) Necrotic areas on the ventral region (white arrows), (

C) hemorrhages in the ventral fins, (black arrow) (

D) different grades of skin lesions (black lines), (

E-F) tubercules in the spleen (red arrows), (

G) granulomas in heart (red arrow), (

H) enlarged spleen and liver (red and white arrows respectively), diffuse hemorrhage in liver (black arrow) [

12].

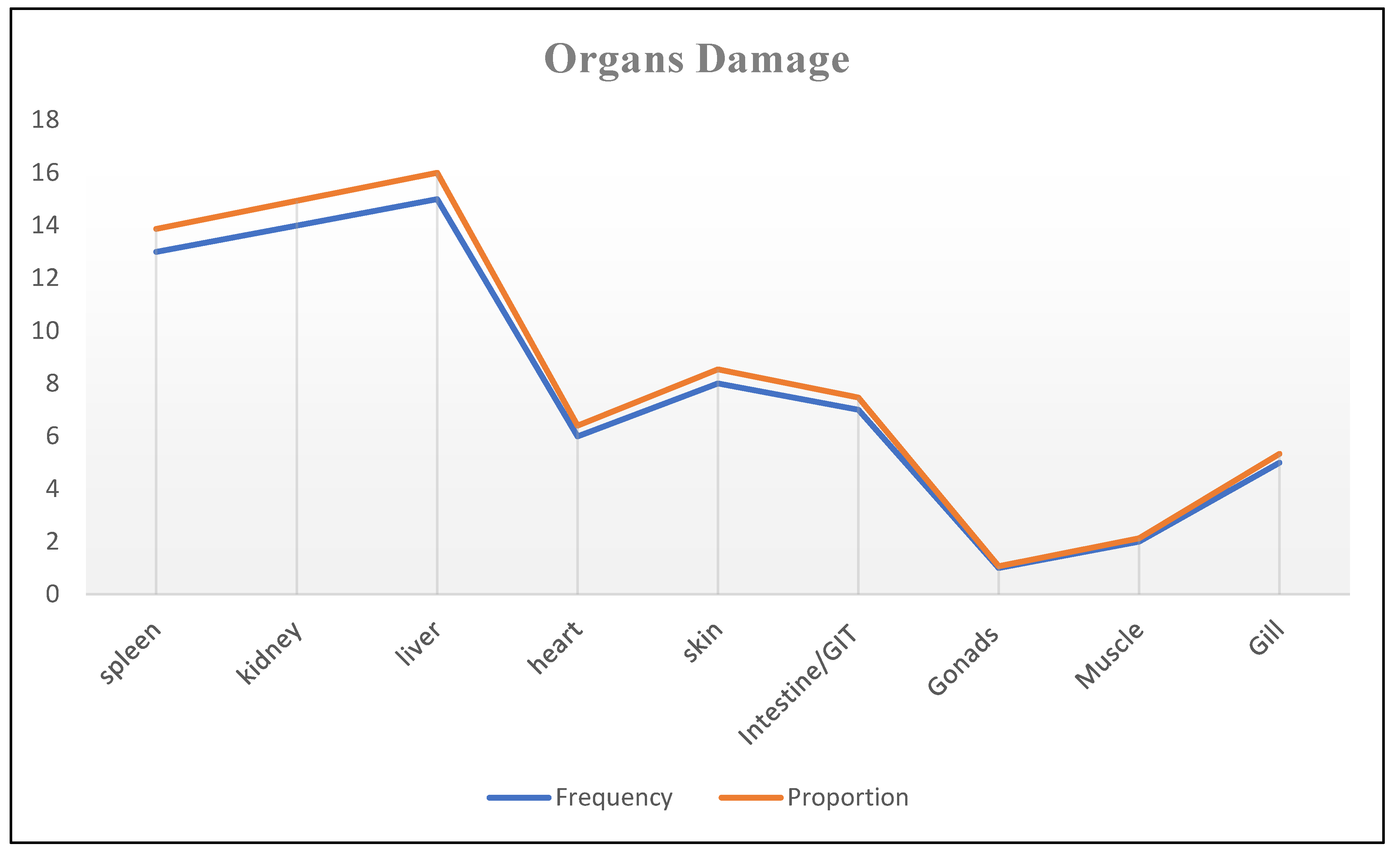

This systematic review have found frequently observed gross or necropsy lesions of M. marinum included tubercle lesions, splenomegaly, ascites, hemorrhage, yellow mucus, and nodules. Necropsy revealed tubercles in internal organs, particularly diffuse granulomas in the spleen and liver [

13]. The primary pathological feature of M. marinum infection in fish is classical granulomatous inflammation [

22]. Tubercle formation and splenic enlargement [

4], along with nodular lesions in the liver, kidney, and spleen, were the most commonly reported pathological findings [

43]. Similarly, the current systematic review found that the kidney, liver, and spleen were the most frequently damaged organs where granulomas were commonly observed.

Figure 12.

(

a) Granulomas in spleen in meagre infected with mycobacterium marinum [

3], (

b) gills of hybrid striped bass: hemorrhagic lesions with yellow-brown nodules and mucus exudate [

13].

Figure 12.

(

a) Granulomas in spleen in meagre infected with mycobacterium marinum [

3], (

b) gills of hybrid striped bass: hemorrhagic lesions with yellow-brown nodules and mucus exudate [

13].

Figure 13.

(

a) Scophthalmus maximus, Fish heavily infected by mycobacteria, Notice the granulomatous lesions in kidney (black arrow) [

13], (

b) Gray and whitish nodules observed on internal organs of a goldfish (Carassius auratus) (red arrow) [

32].

Figure 13.

(

a) Scophthalmus maximus, Fish heavily infected by mycobacteria, Notice the granulomatous lesions in kidney (black arrow) [

13], (

b) Gray and whitish nodules observed on internal organs of a goldfish (Carassius auratus) (red arrow) [

32].

Figure 14.

Multifocal white granulomas, (

a) in the liver and spleen (red & black arrows respectively), (

b) in the spleen and kidney (red & blue arrows respectively), (

c) in the spleen (red arrow), (

d) in the kidney (black arrow) [

43].

Figure 14.

Multifocal white granulomas, (

a) in the liver and spleen (red & black arrows respectively), (

b) in the spleen and kidney (red & blue arrows respectively), (

c) in the spleen (red arrow), (

d) in the kidney (black arrow) [

43].

Figure 15.

Mugil cephalus. Internal organs affected by Mycobacteriosis (

a) (white arrow), Multifocal small whitish nodules ranging in size from 0.2 to 0.5 cm (white arrows) in liver (

b) and spleen (

c) (white arrow) (Bar = 2 mm) [

14].

Figure 15.

Mugil cephalus. Internal organs affected by Mycobacteriosis (

a) (white arrow), Multifocal small whitish nodules ranging in size from 0.2 to 0.5 cm (white arrows) in liver (

b) and spleen (

c) (white arrow) (Bar = 2 mm) [

14].

Figure 16.

(a–d) Gross pathology of Atlantic mackerel showing nodules in viscera. All diagnosed with Mycobacteriosis. (

a) Nodules around intestine and on liver (white arrow). (

b) Smaller nodules in kidney (red arrow). (

c) White arrows pointing at one large tumor-like growth cut in half (white arrow). (

d) Extensive occurrence of nodules in kidney and viscera (red arrow) [

39].

Figure 16.

(a–d) Gross pathology of Atlantic mackerel showing nodules in viscera. All diagnosed with Mycobacteriosis. (

a) Nodules around intestine and on liver (white arrow). (

b) Smaller nodules in kidney (red arrow). (

c) White arrows pointing at one large tumor-like growth cut in half (white arrow). (

d) Extensive occurrence of nodules in kidney and viscera (red arrow) [

39].

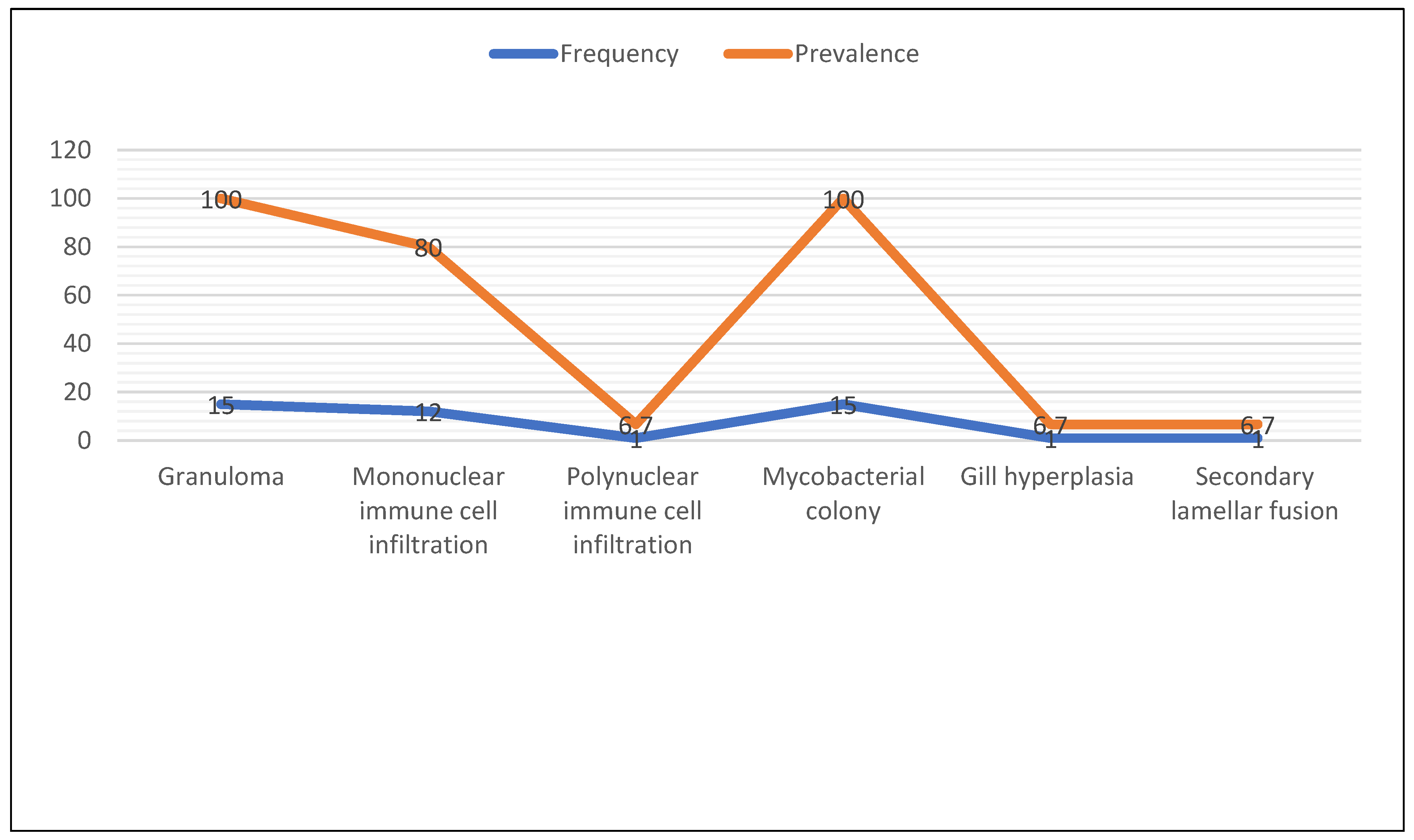

At the histological level, this systematic review found that granulomas, nodules, colonies of mycobacteria, and mononuclear cell infiltration were the most frequently reported findings. These histopathological features closely resembled those observed in striped bass, experimentally infected sea bass, wild rabbitfish [

11], turbot [

13], cultured sea bass [

24], and ornamental fish [

29]. However, granulomas were not observed in the gut and eye tissues [

11,

29]. Similarly, this systematic review did not find granulomas in the eye.

Figure 17.

(A) Multiple granulomas in spleen (black arrow) (x10), (

B) Bacteria clumps in splenic lesion (black arrow) (x20) [

5].

Figure 17.

(A) Multiple granulomas in spleen (black arrow) (x10), (

B) Bacteria clumps in splenic lesion (black arrow) (x20) [

5].

Figure 18.

Spleen: granulomas with a central eosinophilic area of necrosis with dark brown pigment surrounded by inflammatory cells and enclosed by a thin capsule (black arrow) (H&E, •10) [

5].

Figure 18.

Spleen: granulomas with a central eosinophilic area of necrosis with dark brown pigment surrounded by inflammatory cells and enclosed by a thin capsule (black arrow) (H&E, •10) [

5].

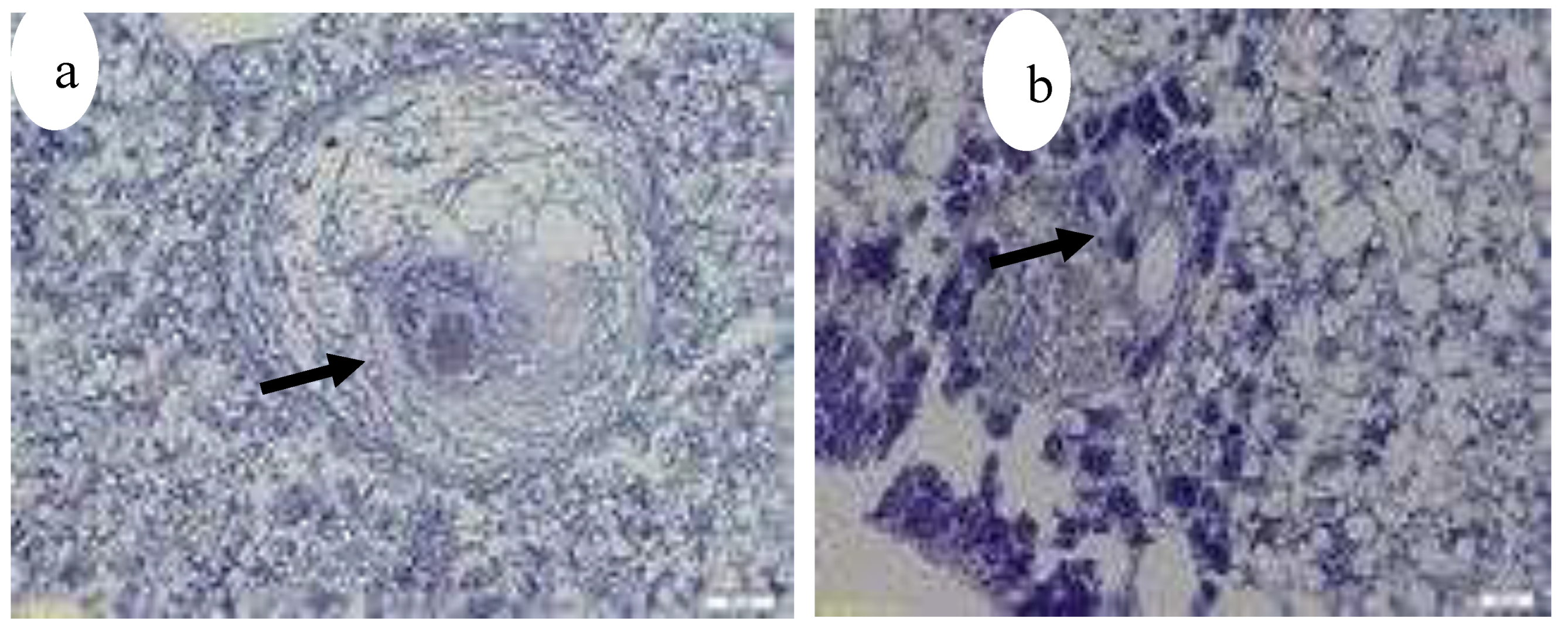

Figure 19.

Granulomas in kidney, Hex200 (

a) (black arrow), Granuloma containing numerous acid fast bacteria (arrows), ZN x 1000 (

b) (black arrow) [

3].

Figure 19.

Granulomas in kidney, Hex200 (

a) (black arrow), Granuloma containing numerous acid fast bacteria (arrows), ZN x 1000 (

b) (black arrow) [

3].

Figure 20.

(a) Kidney of Aphyosemion gardneri with hyaline droplets in the tubular epithelium adjacent to granulomas (H&E, ·400) (black arrow), (

b) Kidney of Aphyosemion gardneri with infiltration of adipose tissue containing inflammatory infiltrate (H&E, 40) (black arrow) [

29].

Figure 20.

(a) Kidney of Aphyosemion gardneri with hyaline droplets in the tubular epithelium adjacent to granulomas (H&E, ·400) (black arrow), (

b) Kidney of Aphyosemion gardneri with infiltration of adipose tissue containing inflammatory infiltrate (H&E, 40) (black arrow) [

29].

Figure 21.

(

a) Scophthalmus maximus infected by mycobacteria, Haematoxylin-eosin stained kidney granulomata at different stages of development; fibrous capsule; CN, caseative necrosis; EP, epithelioid cells; G, mature granuloma; PG, pregranulomatous lesions, (

b) Scophthalmus maximus infected by mycobacteria, Atypical mononucleated giant cells (MGC) in a granulomatous lesion of kidney (haematoxylin-eosin stained) [

13].

Figure 21.

(

a) Scophthalmus maximus infected by mycobacteria, Haematoxylin-eosin stained kidney granulomata at different stages of development; fibrous capsule; CN, caseative necrosis; EP, epithelioid cells; G, mature granuloma; PG, pregranulomatous lesions, (

b) Scophthalmus maximus infected by mycobacteria, Atypical mononucleated giant cells (MGC) in a granulomatous lesion of kidney (haematoxylin-eosin stained) [

13].

Figure 22.

(

c) Atypical mononucleated giant cells (MGC) in a granulomatous lesion of kidney (haematoxylin-eosin stained). (

c) Higher magnification of an area in (

b) [

13].

Figure 22.

(

c) Atypical mononucleated giant cells (MGC) in a granulomatous lesion of kidney (haematoxylin-eosin stained). (

c) Higher magnification of an area in (

b) [

13].

Histopathological examination of infected spleen and liver samples revealed numerous epithelioid cell granulomas, with clumps of mycobacteria inside the nodules causing bacterial inflammation. Similarly, nodular appearances were evident on the liver surface, surrounded by inflammatory cells. These findings align with previous observations of Mycobacterium infection in fish [

3] observed granulomas surrounded by inflammatory cells in the kidney, liver, and spleen tissues of infected meagre (Argyrosomus regius).

30 reported more severe infections in the spleen and head kidney compared to the liver, with chronic inflammation as the predominant histopathological change.

Figure 23.

Histological picture of acute (

a, b) and chronic cases (

c, d); (

a) spleen of a lyretail coral fish (Pseudanthias squamipinnis) showing pathology interpreted as acute lesions, like infiltration with high numbers of macrophages and single cell necrosis in the center of the infiltration (circle); (

b) acid fast bacteria are visible in high numbers intracellular in the macrophages and extracellular in the surrounding tissue (open arrowheads); (

c) liver of a lyretail coral fish (Pseudanthias squamipinnis) showing chronic lesions characterized by multiple well circumscribed granulomas with a central necrosis, a small rim of macrophages and peripheral thick rim of fibroblasts (closed arrowhead); (

d) acid fast bacteria are present only extracellular in the surrounding tissue (open arrowhead); bars = 50mm; HE stain (

a, c), ZN stain (

b, d) [

23].

Figure 23.

Histological picture of acute (

a, b) and chronic cases (

c, d); (

a) spleen of a lyretail coral fish (Pseudanthias squamipinnis) showing pathology interpreted as acute lesions, like infiltration with high numbers of macrophages and single cell necrosis in the center of the infiltration (circle); (

b) acid fast bacteria are visible in high numbers intracellular in the macrophages and extracellular in the surrounding tissue (open arrowheads); (

c) liver of a lyretail coral fish (Pseudanthias squamipinnis) showing chronic lesions characterized by multiple well circumscribed granulomas with a central necrosis, a small rim of macrophages and peripheral thick rim of fibroblasts (closed arrowhead); (

d) acid fast bacteria are present only extracellular in the surrounding tissue (open arrowhead); bars = 50mm; HE stain (

a, c), ZN stain (

b, d) [

23].

Figure 24.

(

a) Liver of Aphyosemion gardneri with focal lipomatosis with adjacent macrophages forming a granuloma (H&E, ·400) (black arrow), (

b) Liver of Aphyosemion gardneri showing a later stage of granuloma with central necrosis (H&E, ·100) (black arrow) [

29].

Figure 24.

(

a) Liver of Aphyosemion gardneri with focal lipomatosis with adjacent macrophages forming a granuloma (H&E, ·400) (black arrow), (

b) Liver of Aphyosemion gardneri showing a later stage of granuloma with central necrosis (H&E, ·100) (black arrow) [

29].

Figure 25.

Liver of Aphyosemion gardneri with focal lipomatosis and an early stage of granuloma formation. Macrophages with abundant cytoplasm and scattered heterophils (H&E, ·400) (black arrow) [

29].

Figure 25.

Liver of Aphyosemion gardneri with focal lipomatosis and an early stage of granuloma formation. Macrophages with abundant cytoplasm and scattered heterophils (H&E, ·400) (black arrow) [

29].

Figure 26.

(

a) Nodule development on the surface of liver (black arrow) (x20) [

5], (

b) Inflammatory cells caused by mycobacteria in liver tissue (x40) (black arrow) (H&E) [

12].

Figure 26.

(

a) Nodule development on the surface of liver (black arrow) (x20) [

5], (

b) Inflammatory cells caused by mycobacteria in liver tissue (x40) (black arrow) (H&E) [

12].

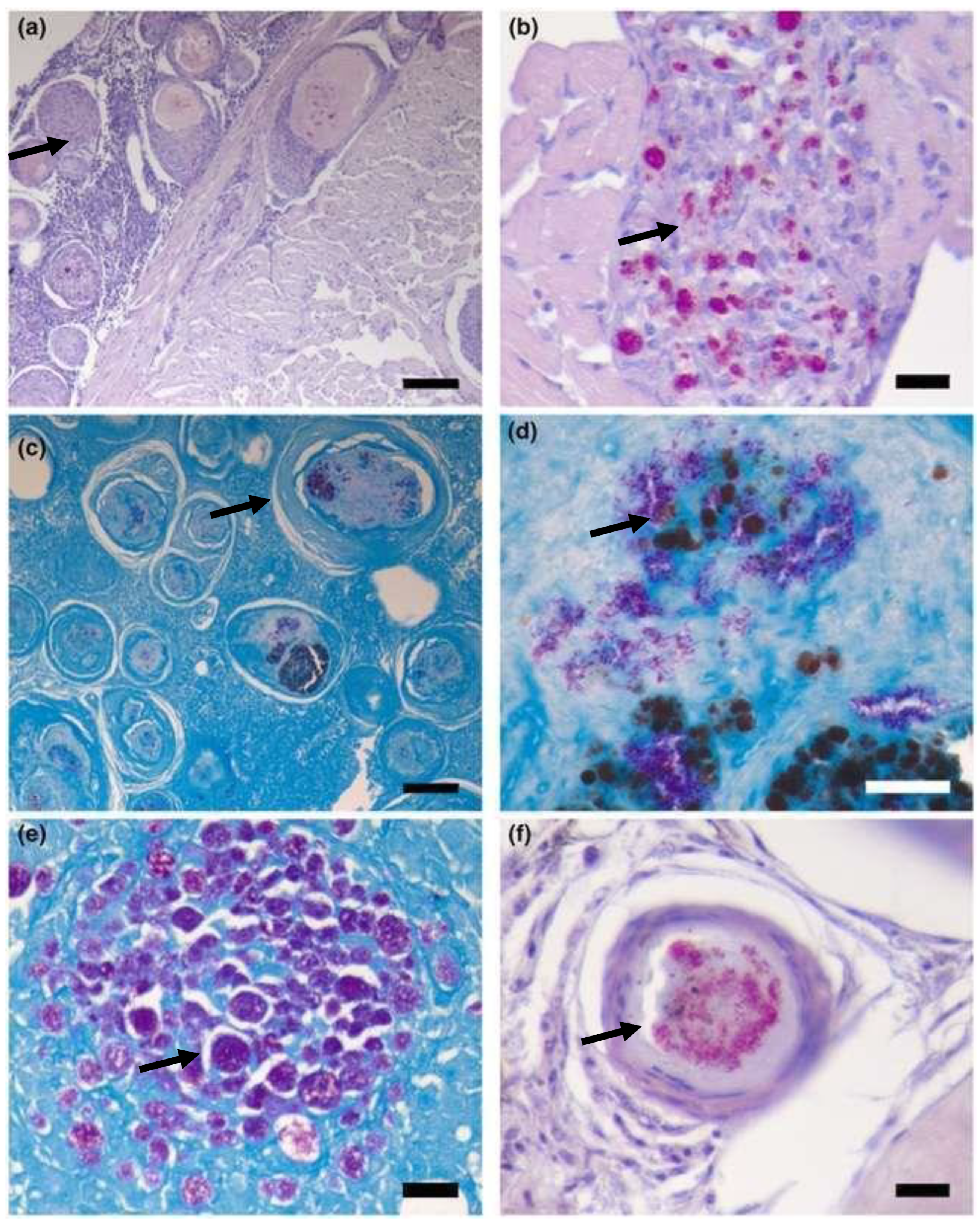

Figure 27.

(a–f) Histopathology based on tissue samples from fresh mackerels; Ziehl-Neelsen staining, (a, b, f) hematoxyline counterstaining and (c–e) methyl blue as counterstaining. Mycobacteria are stained bright pink/ purple. (a) Severe granulomatous epicarditis of, scale bar 100 μm. (b) Staining of mycobacteria in granuloma in myocardium, scale bar 15 μm. (c) Granulomas in kidney, scale bar 100 μm. (d) Enlargement of centre granuloma in (c) showing free mycobacteria cells, scale bar 15 μm. (e) Aggregates of mycobacteria in liver of, scale bar 25 μm. (f) Muscle with granuloma containing mycobacteria, scale bar 10 μm.39.

Figure 27.

(a–f) Histopathology based on tissue samples from fresh mackerels; Ziehl-Neelsen staining, (a, b, f) hematoxyline counterstaining and (c–e) methyl blue as counterstaining. Mycobacteria are stained bright pink/ purple. (a) Severe granulomatous epicarditis of, scale bar 100 μm. (b) Staining of mycobacteria in granuloma in myocardium, scale bar 15 μm. (c) Granulomas in kidney, scale bar 100 μm. (d) Enlargement of centre granuloma in (c) showing free mycobacteria cells, scale bar 15 μm. (e) Aggregates of mycobacteria in liver of, scale bar 25 μm. (f) Muscle with granuloma containing mycobacteria, scale bar 10 μm.39.

Figure 28.

(

a) Bacterial embolus (asterisk) with acid-fast rods in the afferent artery of the primary gill lamella of Poecilia reticulate (star) (Ziehl–Neelsen, ·400) [

29], (

b) Gills: multiple granulomatous lesions characterised by a central area of intensely eosinophilic cellular debris (black arrow) (H&E, ·20) [

5].

Figure 28.

(

a) Bacterial embolus (asterisk) with acid-fast rods in the afferent artery of the primary gill lamella of Poecilia reticulate (star) (Ziehl–Neelsen, ·400) [

29], (

b) Gills: multiple granulomatous lesions characterised by a central area of intensely eosinophilic cellular debris (black arrow) (H&E, ·20) [

5].

Figure 29.

Gills: acid fast bacilli within the necrotic core of the granuloma (black arrows) (ZN, ·40) [

5]

.

Figure 29.

Gills: acid fast bacilli within the necrotic core of the granuloma (black arrows) (ZN, ·40) [

5]

.

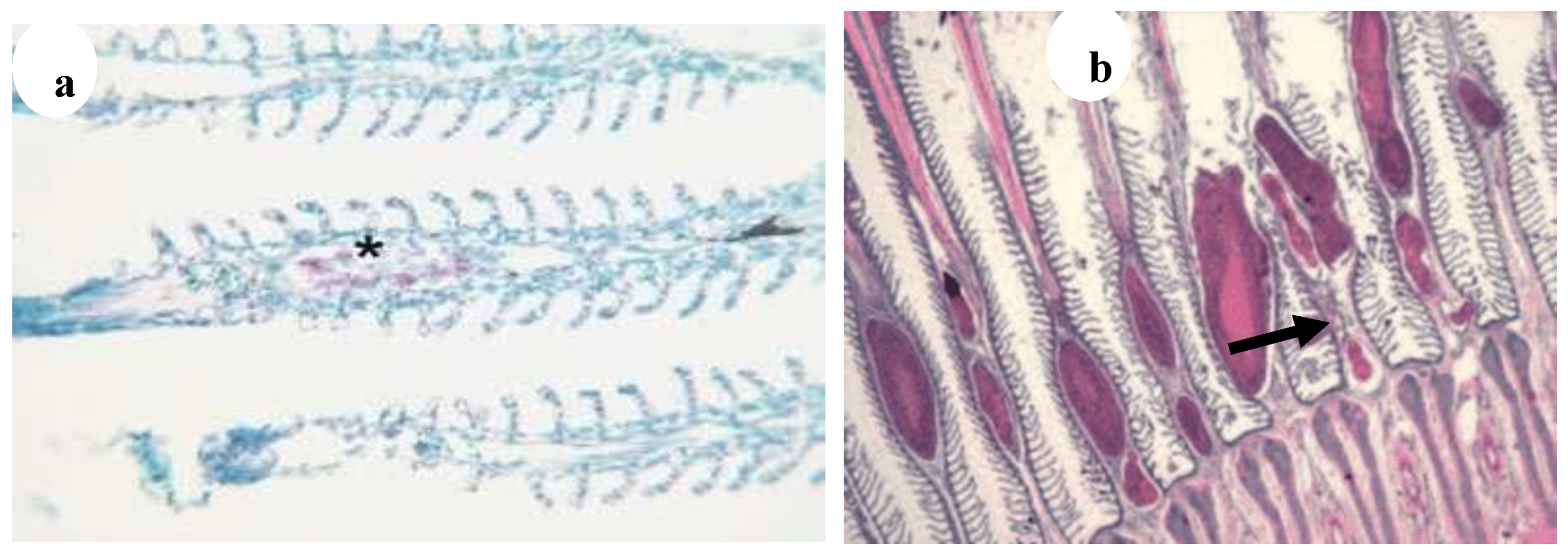

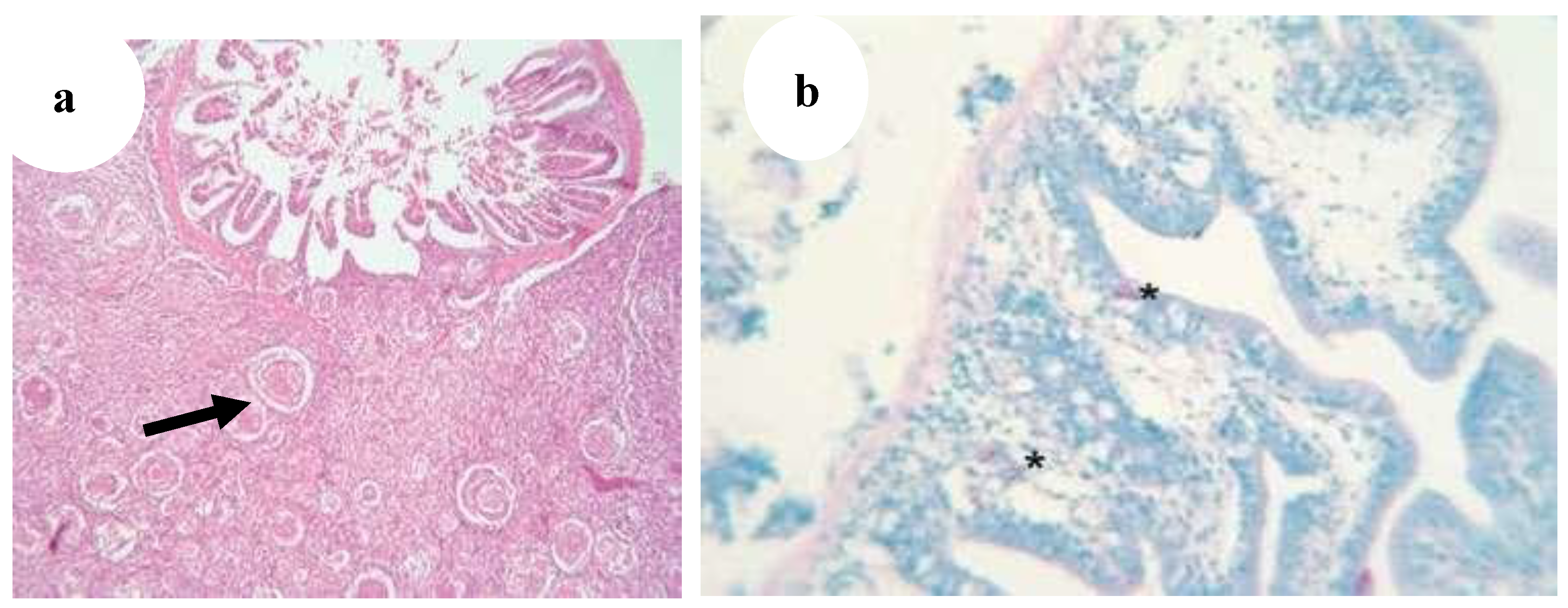

Figure 30.

(

a) Gut wall of Poecilia reticulata infiltrated with granulomatous inflammation spreading from the liver; infection per contactum (black arrow) (H&E, ·100), (

b) Gut of Pterophyllum scalare with acid-fast rods (asterisks) in the enterocytes and in the lamina propria of intestinal villi without granulomas (star) (Ziehl–Neelsen, ·400 [

29].

Figure 30.

(

a) Gut wall of Poecilia reticulata infiltrated with granulomatous inflammation spreading from the liver; infection per contactum (black arrow) (H&E, ·100), (

b) Gut of Pterophyllum scalare with acid-fast rods (asterisks) in the enterocytes and in the lamina propria of intestinal villi without granulomas (star) (Ziehl–Neelsen, ·400 [

29].

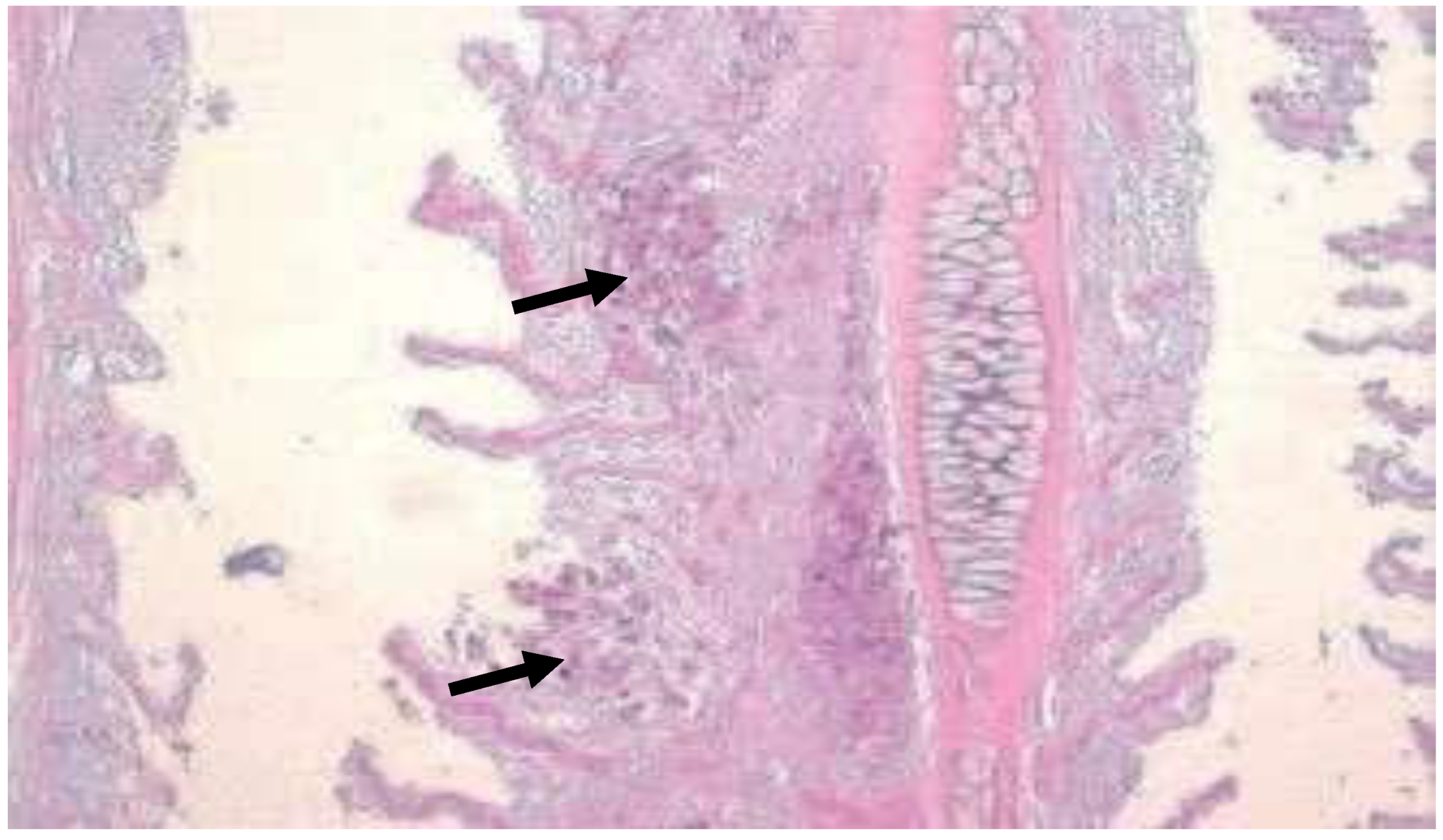

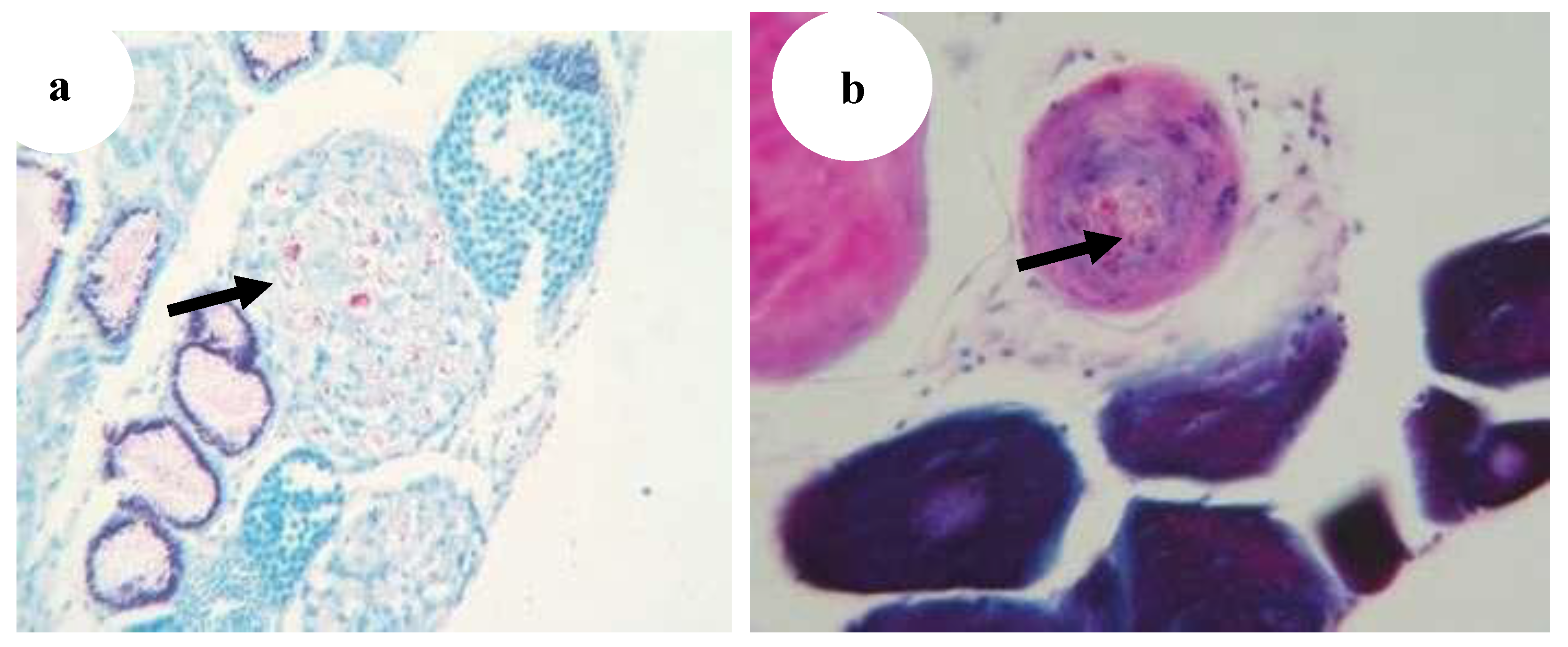

Figure 31.

(

a) Testes of Xiphophorus maculatus with granulomas containing acid-fast rods (Ziehl–Neelsen, ·400) (black arrow), (

b) Ovary of Poecilia reticulata with granulomas containing acid-fast rods (Ziehl–Neelsen, ·400) (black arrow) [

29].

Figure 31.

(

a) Testes of Xiphophorus maculatus with granulomas containing acid-fast rods (Ziehl–Neelsen, ·400) (black arrow), (

b) Ovary of Poecilia reticulata with granulomas containing acid-fast rods (Ziehl–Neelsen, ·400) (black arrow) [

29].

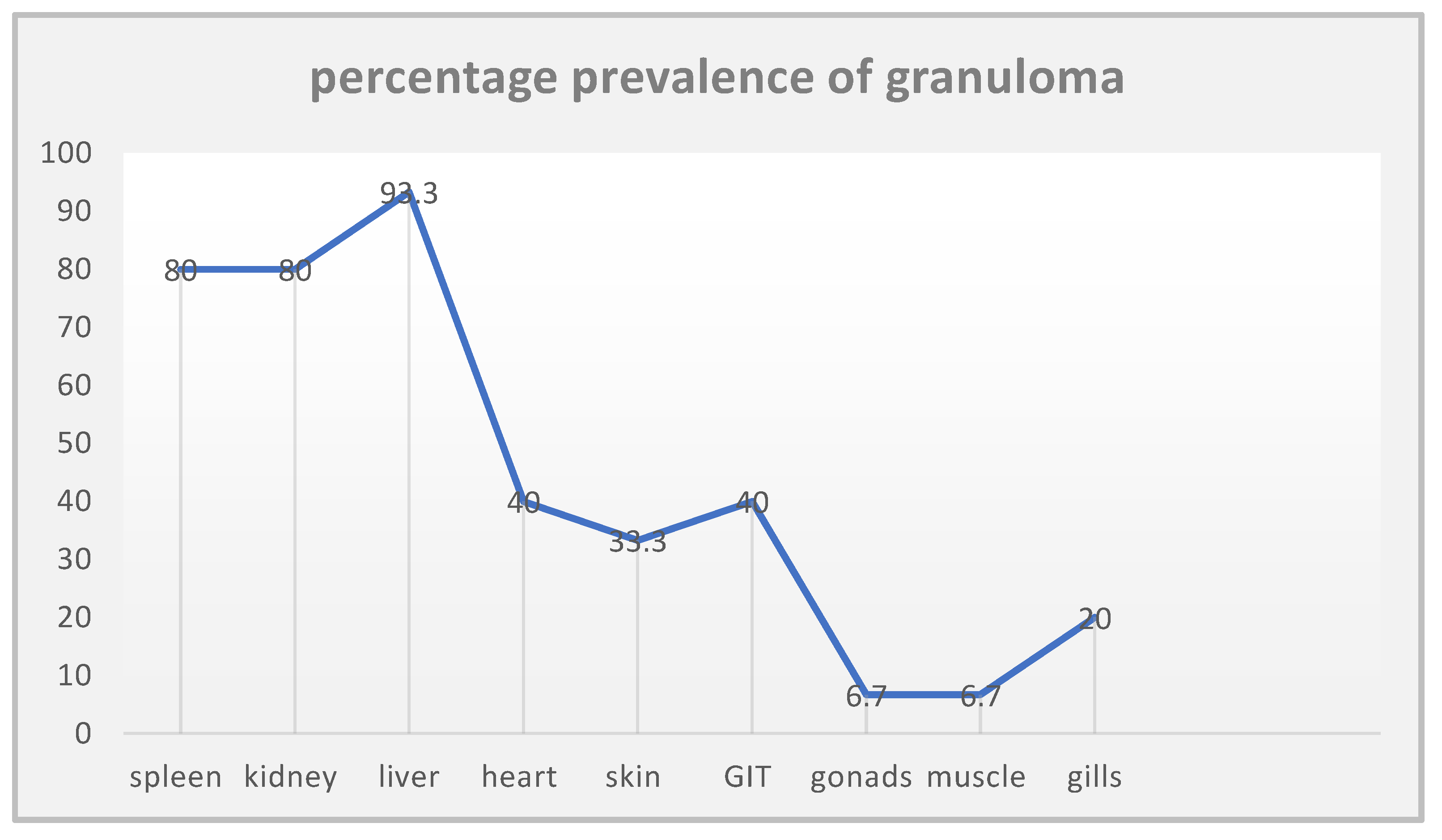

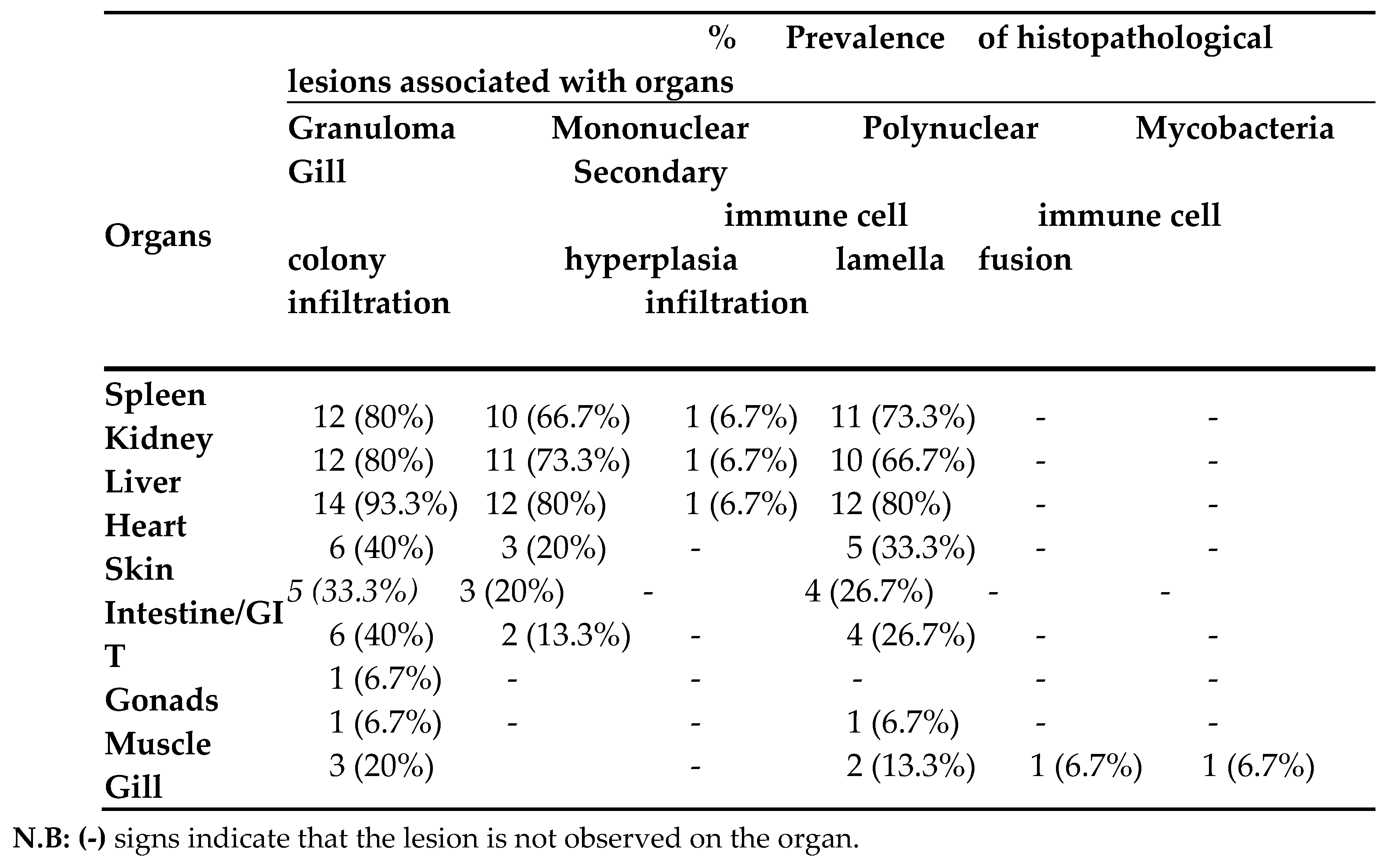

The systematic review found that the prevalence of histopathological lesions (particularly granulomas) was highest in the liver (93.3%), spleen (80%), and kidney (80%), followed by mycobacterial colonies and mononuclear immune cell infiltration (mainly macrophages). Granulomas were less frequently observed in gonads and muscle tissues, while gill hyperplasia and secondary lamellar fusion were least frequent.

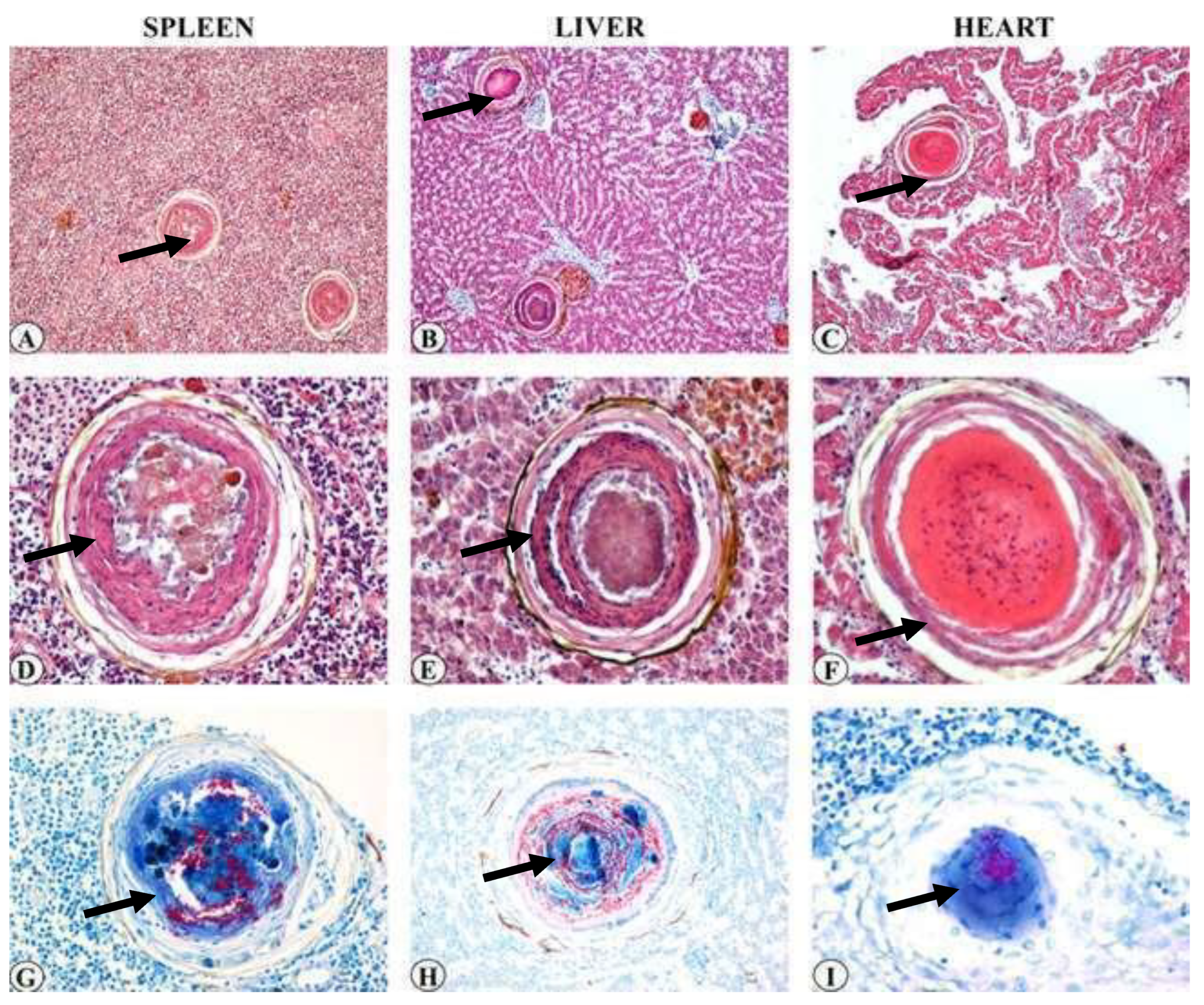

Figure 32.

Multiple granulomas throughout the splenic (

a) and liver (

b) parenchyma (HE stain, bar = 50 lm). (

c) Focal granuloma in heart (HE stain, bar = 50 lm). (

d–f) high magnification of (

a–c). Intermediate granulomas with focal central necrosis in spleen (

d) and showing a central area of coagulative necrosis lined by a layer of flat cells and macrophages in liver (

e) (HE stain, bar = 100 lm). Late granuloma composed of laminar material without necrotic core within cardiac muscle (

f) (HE stain, bar = 100 lm). Numerous acid-fast rods are visible within spleen (

g), liver (

h) and heart (

i) granulomas (ZN stain, bar = 100 lm) (black arrows for each organs) [

14].

Figure 32.

Multiple granulomas throughout the splenic (

a) and liver (

b) parenchyma (HE stain, bar = 50 lm). (

c) Focal granuloma in heart (HE stain, bar = 50 lm). (

d–f) high magnification of (

a–c). Intermediate granulomas with focal central necrosis in spleen (

d) and showing a central area of coagulative necrosis lined by a layer of flat cells and macrophages in liver (

e) (HE stain, bar = 100 lm). Late granuloma composed of laminar material without necrotic core within cardiac muscle (

f) (HE stain, bar = 100 lm). Numerous acid-fast rods are visible within spleen (

g), liver (

h) and heart (

i) granulomas (ZN stain, bar = 100 lm) (black arrows for each organs) [

14].

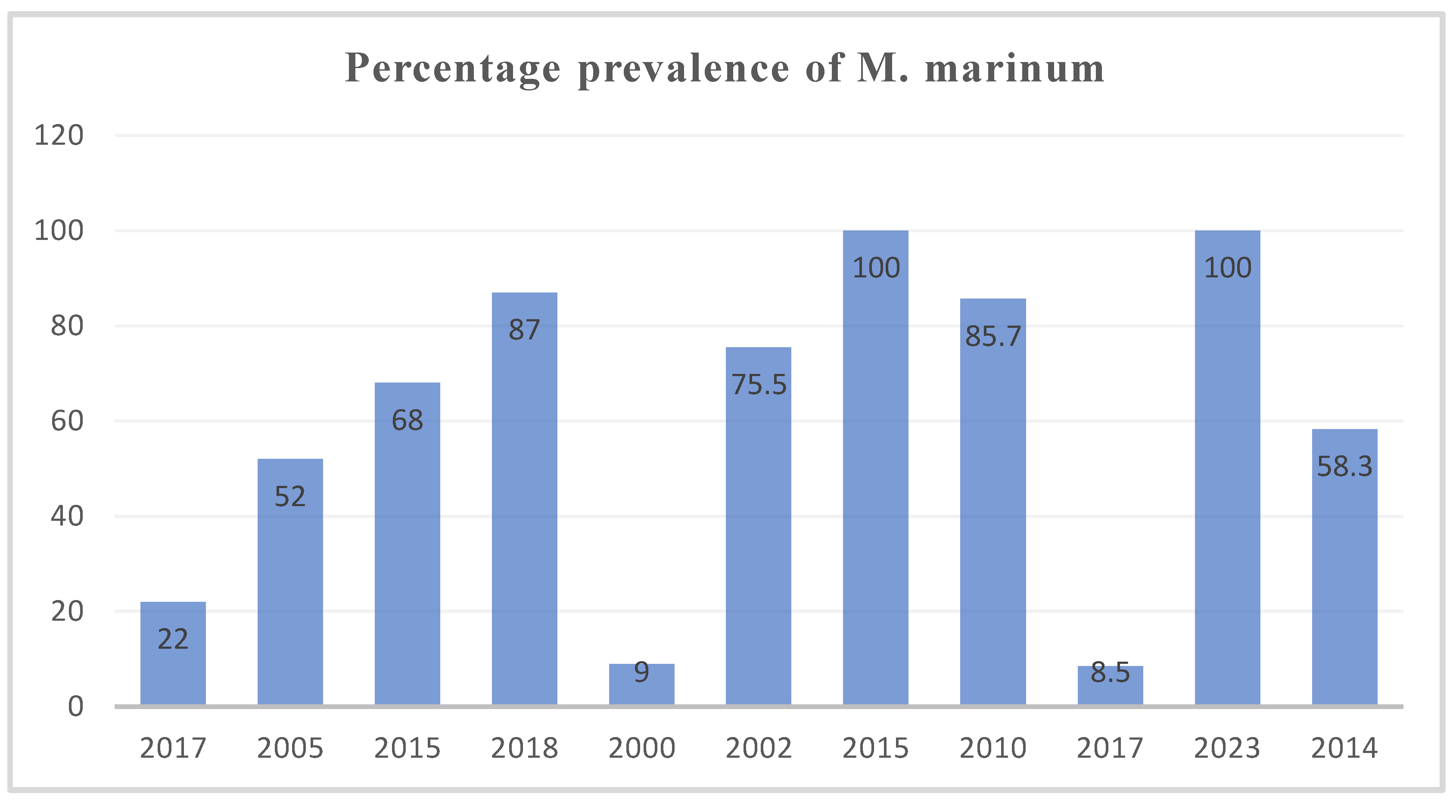

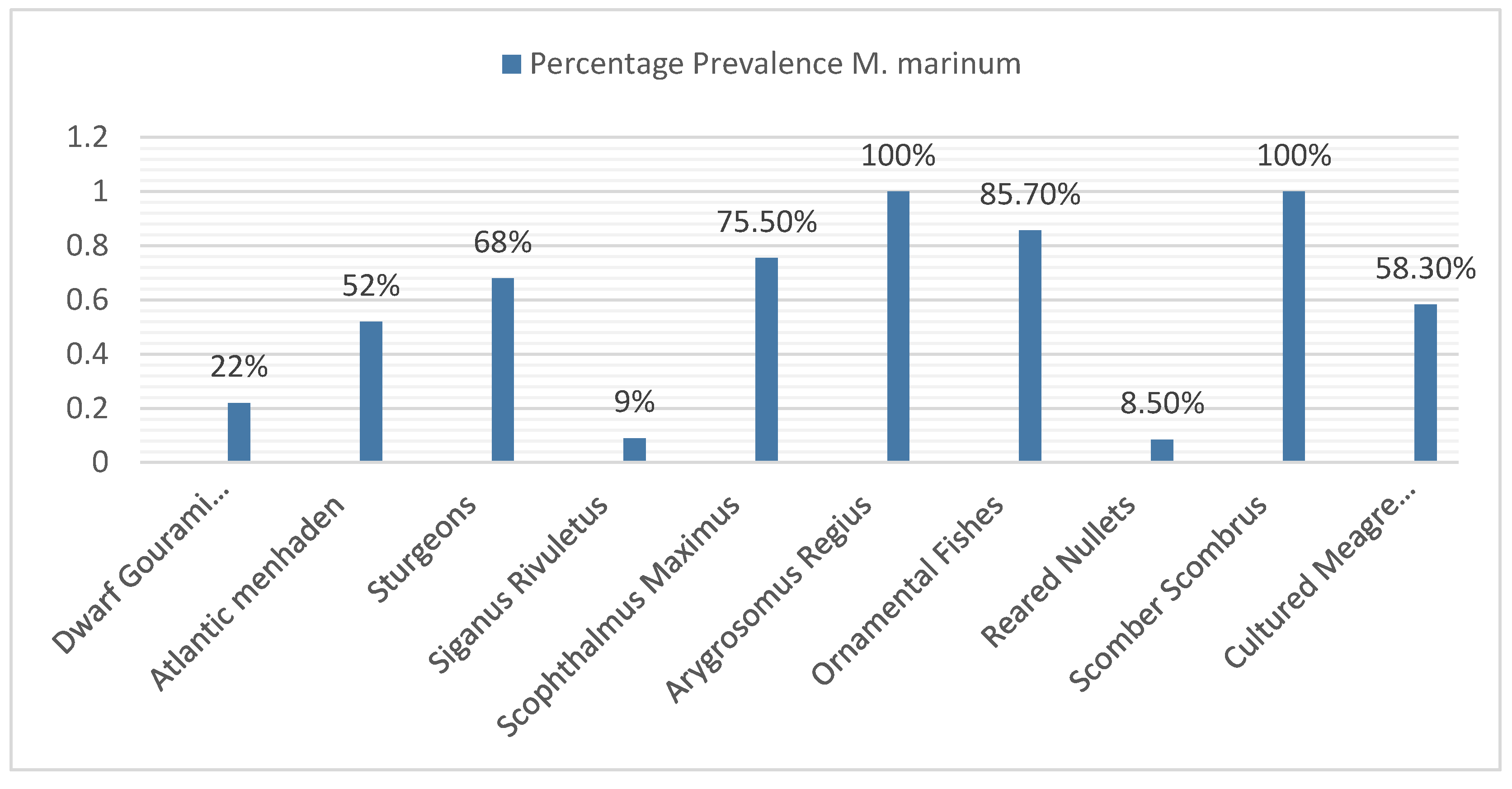

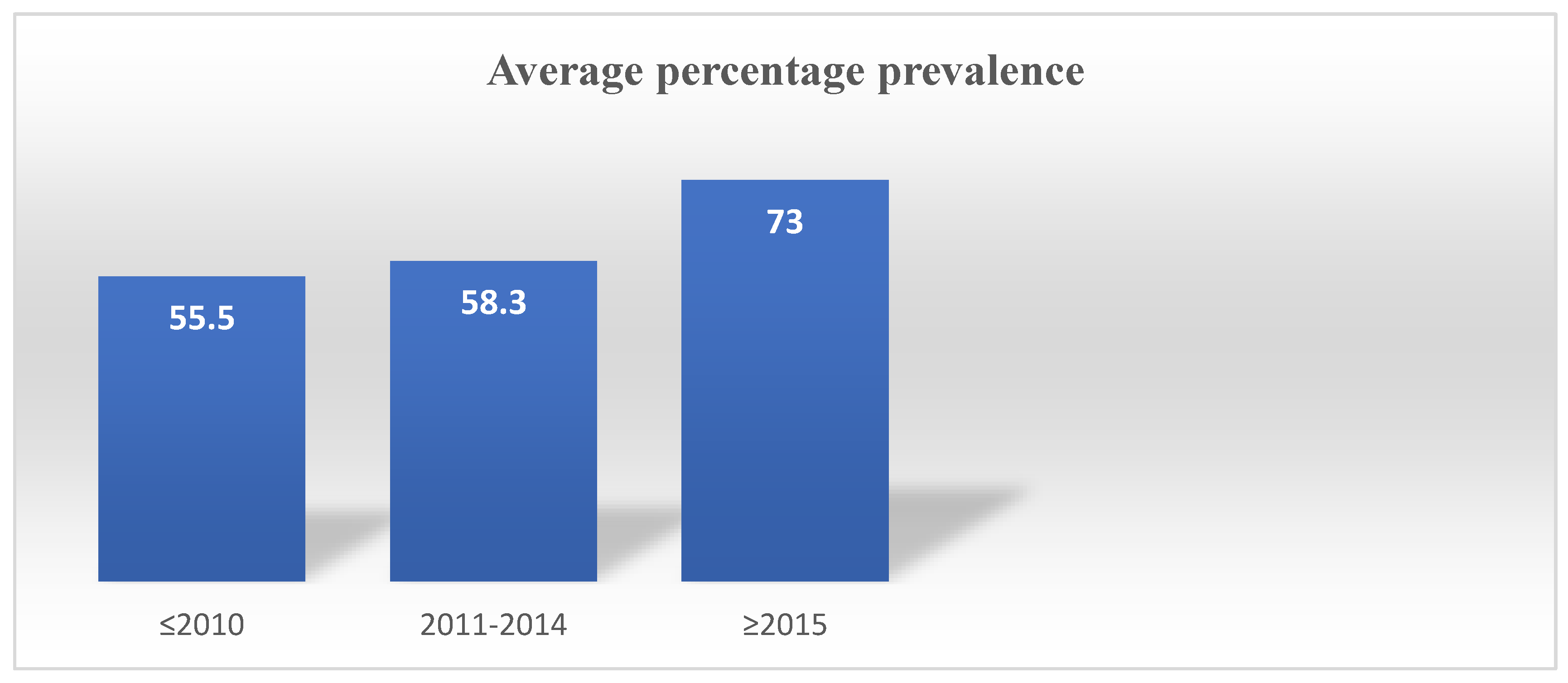

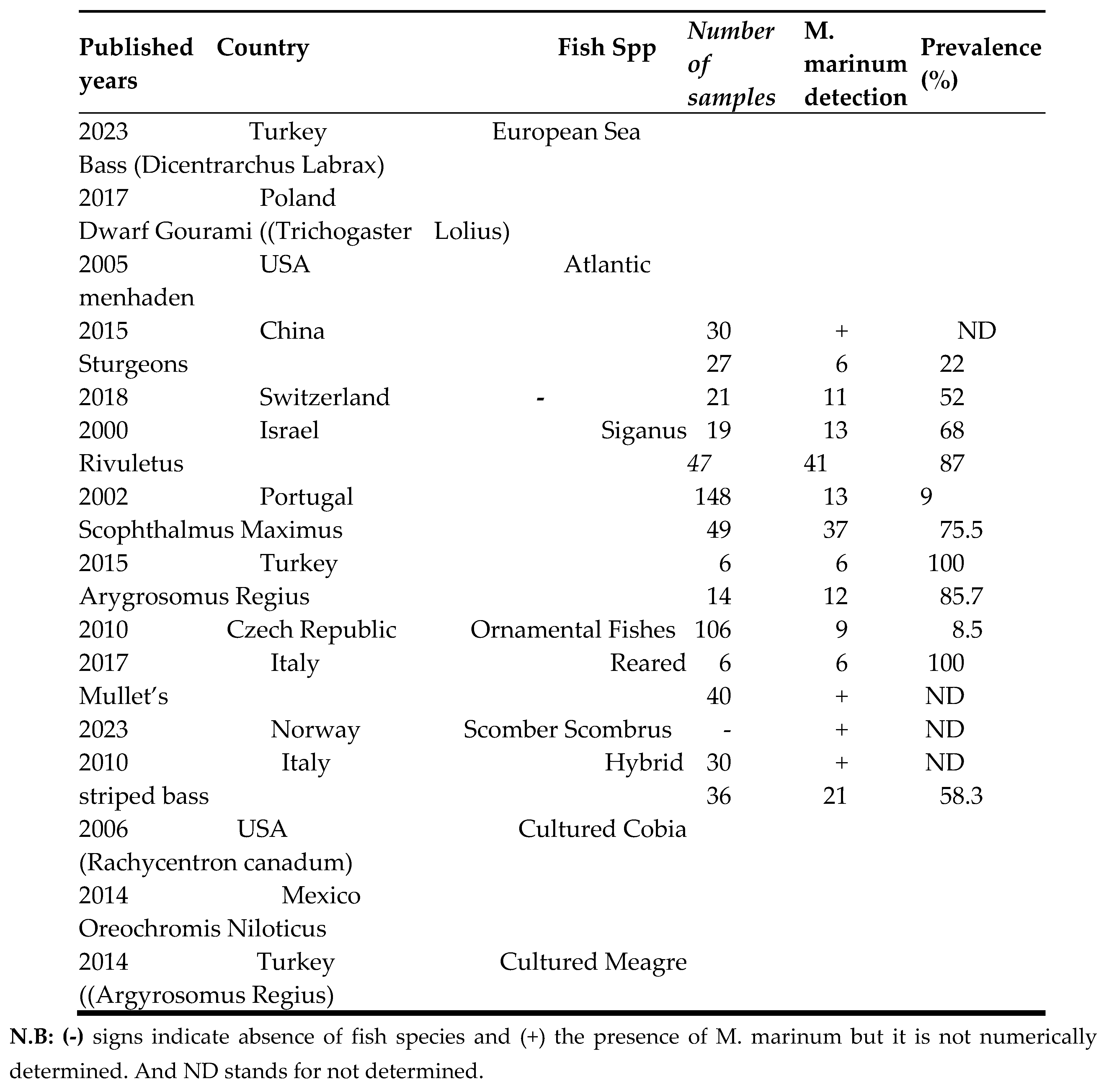

Based on the compiled data, Argyrosomus regius in Turkey (2015) and Scomber scombrus in Norway (2023) showed the highest prevalence of M. marinum (100%), while Siganus rivulatus in Israel (2000) (9%) and mullets in Italy (2017) (8.5%) exhibited the lowest prevalence. The systematic review found that the average prevalence of M. marinum was 57.5%, which was lower than most of the included studies on clinically diseased fish. The prevalence ranged from 55.5% (≤2010), 58.3% (2011–2014), and 73% (≥2017). This indicates an increasing trend in M. marinum occurrence in aquaculture, likely due to inadequate management practices such as poor water treatment, irregular cleaning, and suboptimal feeding systems. The incidence of Mycobacteriosis has been increasing dramatically, and its consequences for aquaculture are still poorly understood. Species-specific interactions, overcrowded conditions, and environmental stressors could play central roles in the epidemiology of Mycobacteriosis [

12,

22,

46].

Mycobacteriosis caused by M. marinum continues to pose a significant threat, particularly to sea bass cultured along the Mediterranean coasts of Greece, Israel, Italy, and Turkey, as well as along the Red Sea coast of Israel [

11,

45]. similarly, the current systematic review included studies conducted in Israel, Italy, and Turkey. The review also found that sturgeon fish groups, Scophthalmus maximus, Argyrosomus regius, ornamental fish groups, Scomber scombrus, and cultured meagre (Argyrosomus regius) fish species are mostly at higher risk from M. marinum. Moreover, Mycobacteriosis in fish has not been thoroughly investigated using a combination of histopathological, bacteriological, biochemical and molecular biology methods [

43]. As a result, this disease is often underdiagnosed, and information about its impact on farmed fish remains limited [

5].

Some authors have reported that striped bass is more susceptible to M. marinum infection than hybrid tilapia, while zebrafish are more susceptible than medaka [

7] and hybrid striped bass [

30]. Several infections caused by this species have been documented worldwide [

1,

47], although only a few cases have been reported from Italy [

5,

27]. While episodes of mycobacterial infections caused by M. marinum and other species have been reported in cultured fish [

13], such cases in Italy have involved rainbow and brown trout. Regular monitoring of M. marinum in marine-farmed fish causing significant mortalities should be maintained and prevented.

Conclusion and Recommendation

Data on the pathological characteristics and frequency of Mycobacterium marinum infection in fish with clinical illnesses in aquaculture were compiled in this systematic review. According to the combined data, Siganus rivulatus and raised mullets had the lowest prevalence, while Argyrosomus regius and Scomber scombrus had the highest. Granulomas, clusters of Mycobacterium colonies, and mononuclear immune cell infiltration were the most commonly seen histopathological abnormalities; these mostly affected the liver, kidney, and spleen, with the gonads and muscles being minimally affected. Skin ulceration, fatigue, exophthalmia, and appetite loss were common clinical indicators, and nodules, splenomegaly, and hemorrhages were frequently seen in gross lesions. The increment in prevalence over time suggests a possible increasing trend of M. marinum occurrence in aquaculture settings. Therefore, Strengthen global and regional surveillance programs for M. marinum infection in aquaculture, Future studies should provide more comprehensive details on: Fish farm management systems, housing, hygiene practices, and biosecurity protocols, Sampling methodologies and risk factors to enhance study comparability and reproducibility, Encourage the use of molecular diagnostics and standardized histopathological protocols to improve detection sensitivity and reduce misdiagnoses, Conduct targeted studies to identify key risk factors contributing to M. marinum infections, such as water quality, stocking density, nutrition, and stress levels, Capacity Building in Emerging Regions, Promote capacity-building initiatives and funding for research in regions like Africa, where data on M. marinum in aquaculture are scarce, Implement preventive measures, including vaccination research, biosecurity improvements, and farmer training programs to reduce the burden of M. marinum, Longitudinal Studies Design long-term, multi-regional cohort studies to track the temporal trends of M. marinum prevalence and understand its evolving impact on aquaculture.