1. Introduction

Primates have diverse diets, primarily consisting of plants (Lambert & Rothman, 2015; Richard, 1985). Plant parts vary in their chemical composition, like sugar content, pH, secondary metabolites and fiber content, and in external physical properties, like color, texture and size (Del Bubba et al., 2009). Primates evaluate the physical and chemical properties of food from handling to consumption (Dominy et al., 2001; Laska et al., 2000a, 2009; Sánchez Solano et al., 2022; Sclafani, 2001; Stroebele et al., 2004; Valenta et al., 2013, 2018a). When choosing a fruit, primates have been reported to use color, size, pH, and sugar content as sensory cues. For example, Alouatta spp. Callithrix geoffroyi, Cebus apella, and Hylobates spp. choose yellow, orange, red, and brown fruit (Caine & Mundi, 2000; Dominy & Lucas, 2001; Regan et al., 2001). Other primates, like Cercopithecus ascanius, Cercopithecus mitis and Colobus guereza, select fruits from 1 cm to 7.5 cm in diameter (Flörchinger et al., 2010; McConkey et al., 2002). Several primate species select fruits with a pH ranging from 2 to 5 (Dominy et al., 2001; Laska et al., 2000a; Sánchez-Solano et al., 2022; Ungar, 1995), and those with high sugar content (Riba-Hernández et al., 2003; Stevenson, 2004; Ungar, 1995). Primates that consume leaves also use properties such as color and size as sensory cues for their food choices. For example, Alouatta palliata choose yellow, light green, or reddish colored leaves, and prefer small leaves (Melin et al., 2017; Sánchez-Solano et al., 2020).

The foods that primates select are usually beneficial for their nutritional balance and correspond to their sensory capacity and familiarity. Primates are more likely to consume other foods when preferred foods are unavailable in search of potential energy and nutritional gains (Huskisson et al., 2021) and might modulate their decision-making based on the physical and chemical properties of fruits and leaves.

The relatively controlled conditions of captivity provide an opportunity to evaluate the influence of the physical and chemical properties of foods and plant species on food selection. For example, captive Alouatta guariba clamitans, Saimiri sciureus, Macaca nemestrina, Pithecia pithecia, and Ateles geoffroyi select cultivated food non-opportunistically (Laska, 2001; Martins et al., 2023; Silveira et al., 2024). Cultivated foods have different physical and chemical properties compared to their wild counterparts, influencing the food selection of primates (Lambert & Rothman, 2015; Silveira et al., 2024).

Dietary specialist primates, like spider monkeys, select food based on high energy content while avoiding limiting compounds such as secondary metabolites and fiber using sensory cues offered by the physical and chemical properties of the different plant parts (Del Bubba et al., 2009; Riba-Hernández et al., 2003). Spider monkeys are mainly frugivorous, and wild spider monkeys dedicate 55-90% of their feeding time to ripe fruits (Di Fiore et al., 2008). However, they also consume unripe fruits, and other plant parts such as leaves, seeds, flowers and bark (Felton et al., 2008, 2009; González-Zamora et al., 2009). Leaves can represent as much as 37% of spider monkeys' feeding time (de Luna et al., 2017), and the percentage of total feeding time on young leaves is higher than (7.3%) on mature leaves (1.2%) (Chapman, 1987). This suggests that leaf maturity and the associated changes in macronutrient content may play a role in leaf choice (Felton et al., 2009). Captive black-handed spider monkeys have been reported to select fruits with high amounts of lipids and sugars (Laska et al., 2000b). However, corresponding data on possible correlations between the selection of leaves and their chemical composition are lacking for spider monkeys.

We aimed to assess food selection patterns of Ateles geoffroyi related to the stage of maturity of fruits and leaves from six plant species. We asked the following questions: 1) do the physical and chemical properties of fruits and leaves vary with maturity stage? and 2) how does the maturity of different fruits and leaves influence the food selection of A. geoffroyi? We hypothesized that Ateles geoffroyi are flexible in their food selection depending on the maturity stage of fruits and leaves. We predicted that A. geoffroyi uses different physical and chemical properties (sucrose, pH, color, and size) related to the maturity stage of both fruits and leaves.

2. Methods

2.1. Site and Study Subjects

We conducted our study at the "Hilda Avila de O'Farrill" Environmental Management Unit of the Universidad Veracruzana, near Catemaco in the Los Tuxtlas region (Veracruz, Mexico), from March to August 2022. We conducted tests on five adult female and five adult male spider monkeys. The subjects were kept in individual enclosures (4 m x 4 m x 4 m) connected by sliding doors that allowed them to interact but be separated for individual testing. All individuals were exposed to natural conditions of temperature, relative humidity and light-dark cycles. We did not deprive the monkeys of food but conducted all experiments 2 hours before feeding to ensure that they were motivated. We fed the monkeys a diet of cultivated fruits and vegetables, which varied with fruit availability and seasonality (avocado, banana, mango, tomato, apple, pear, orange, papaya, melon, prickly pear, pineapple, celery, beet, chard and broccoli).

2.2. Fruit and Leaf Collection

We collected unripe and ripe fruits, and young and mature leaves, from six plant species that are part of the diet of wild spider monkeys at Los Tuxtlas (González-Zamora et al., 2009): Ficus colubrinae, Ficus rzedowskiana, Ficus yoponensis, Spondias mombin, Spondias radlkoferi and Poulsenia armata.

We collected fresh food items on the morning of each test day. We selected trees with available fruits and leaves and collected samples from the middle layer, reported as more accessible to fruits and leaves (Feagle et al., 2024). We collected 50 samples of unripe fruit (UF), ripe fruit (RF), young leaf (YL) and mature leaf (ML), from each plant species, resulting in 100 fruits and 100 leaves for each species/day for 5 days. We estimated the maturity stage of fruits and leaves based on color, size and consistency (Di Fiore et al., 2008; Felton et al., 2008; 2009). Additionally, we collected, depending on their availability, a range of 17-28 fruits and 17-28 leaves from each maturity stage to measure fruit sucrose content, pH, color, and size, and leaf color and size.

2.3. Selection Tests

We presented food items to the animals on the same day that we collected them. We conducted one session per day for fruits and one for leaves for five consecutive days for each plant species. In each test we simultaneously presented five items from each maturity stage of the same plant species pseudo-randomly on a 50 cm x 30 cm metal tray. We presented the tray to the monkeys 20 cm away from the mesh of the enclosure and allowed them to take and consume food items for 1 min. We recorded the number of ripe and unripe fruits and young and mature leaves consumed from each plant species.

2.4. Analysis of the Physical and Chemical Properties of the Fruits and Leaves

We measured sucrose content, pH, color and size in unripe and ripe fruits and color and size in young and mature leaves. We measured the sucrose concentration by placing a drop of fruit juice in a refractometer (Atago® Automatic Brix 0.0 ~ 33.0%; Kitamura et al., 2004; Pablo-Rodríguez et al., 2015; Sánchez-Solano et al., 2022). We measured the pH by placing a drop of fruit juice on a test strip (HICARER®). We photographed each item with a moto G9 plus cell phone with a main sensor rear camera: 64 MP (1/1.73"), f/1.8, PDAF, ultra-angular: 8 Mega Pixels (MP) (1/4.0"), f/2.2, Depth 2 MP f/2.2 and Macro: 2 MP f/2.2. We took all photographs using a white LED light ring (NOVOLUNE®). We measured color (RGB composition) and size by analyzing photographs (Chen et al., 2020; Yadav et al., 2010) with the program ImageJ (v 1.52a).

2.5. Statistical Analysis

We used ANOVAs to compare the physical and chemical properties between unripe and ripe fruits (sucrose, pH, color and size as dependent variables) and between young and mature leaves (color and size as dependent variables) of the different plant species. When the ANOVA was significant, we used TukeyHSD post hoc tests to determine which physical and chemical properties showed significant differences in maturity stage (Hothorn et al., 2008; Kassambara, 2023). We used the partial η2 as the size effect calculated with the library effect size (Ben-Shachar et al., 2020).

We used models to test our predictions regarding how A. geoffroyi considers different physical and chemical properties that are associated with the maturity stage of various species of fruits and leaves, respectively. We used generalized linear mixed models, using the number of selected ripe and unripe fruits or mature and young leaves as the dependent variables, to model selection of ripe and unripe fruits and young and mature leaves, respectively, from the same plant species. We ran five models for fruit selection and five models for leaf selection with increasing numbers of fixed effects and interactions. Model 1 included only the random effect individual identity (1 Individual). We included this random effect in all subsequent models. Model 2A evaluated maturity stage as a fixed effect (State + (1 Individual)). Model 2B evaluated only the plant species as a fixed effect (Species + (1 Individual)). Model 3 considered maturity stage and plant species together as fixed effects (State + Species + (1 Individual)). Model 4 evaluated maturity stage nested within species (State/Species + (1 Individual)). We fitted models with Poisson distribution and a log-link function. We report the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC), the r2 of the random effects, and the r2 of the fixed effects for each model.

We conducted all analyses using R (R Core Team, 2023). We used the lme4 library and the glmer function (Bates et al., 2015) to fit the models. We used the rsq library (Zhang, 2023) to calculate the r2 values for each model.

3. Results

3.1. Physical and Chemical Characterization of Food Items

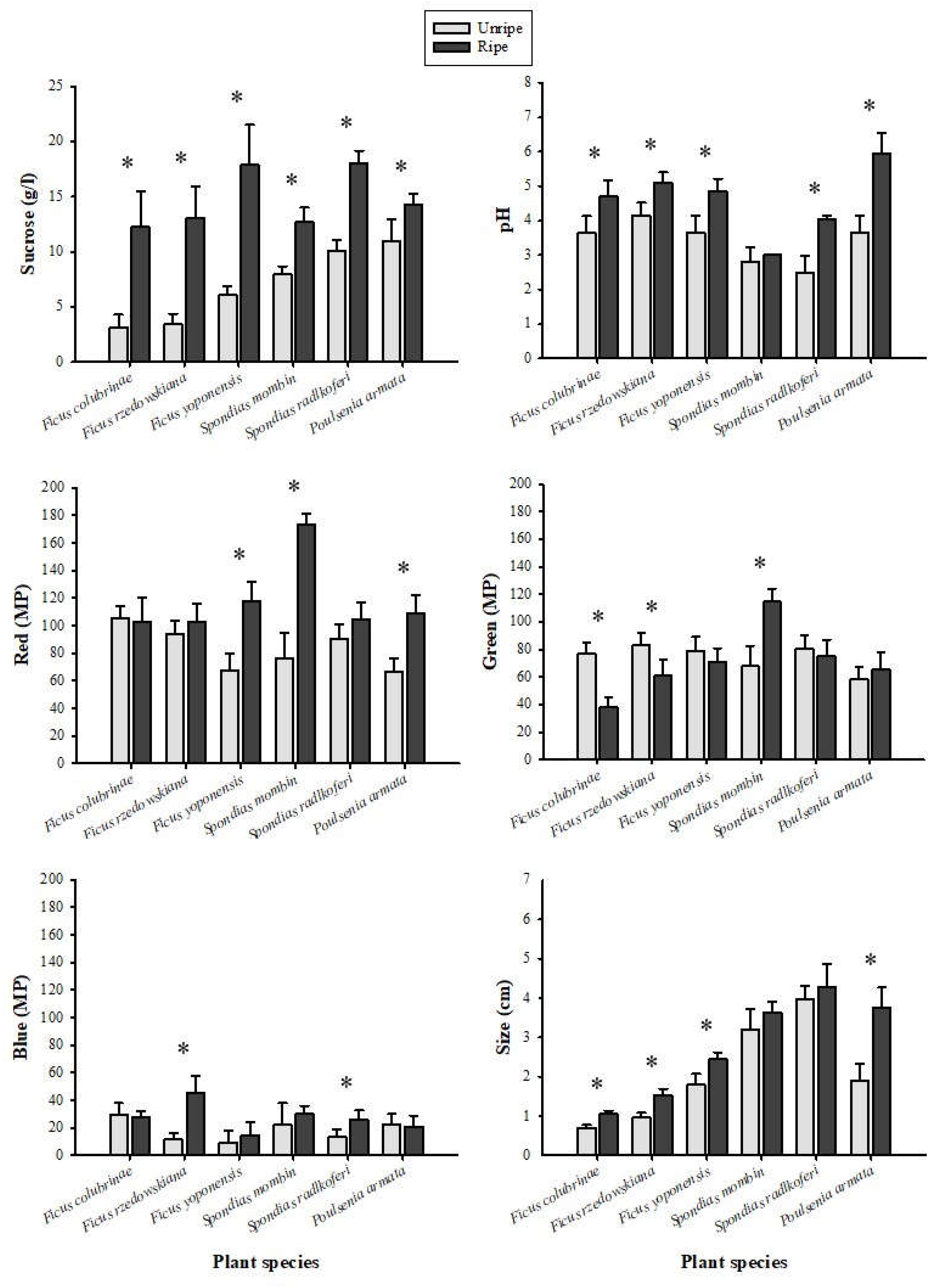

Fruit sucrose content, pH, and size varied significantly among plant species, between ripening stages, and according to the interaction of these two variables (species and ripening stage) (

Table 1). We also found significant differences between plant species, ripening stages, and interaction of these two variables on red and blue colors. For green, we found significant effects for plant species and the interaction term, but not for ripening stage (

Table 1). Sucrose concentration was significantly higher in ripe fruits than in unripe fruits across all six species, and the pH was less acidic in the ripe fruits except for

Spondias mombin (

Figure 1). The RGB color composition of fruits varied: three of the six species turned reddish when mature, the green color decreased in two species, and the blue color increased in only two species (

Figure 1). Ripe fruits were significantly larger than unripe fruits in four species, while we found no significant differences in the size of fruits of

Spondias mombin and

Spondias radlkoferi as a function of ripeness.

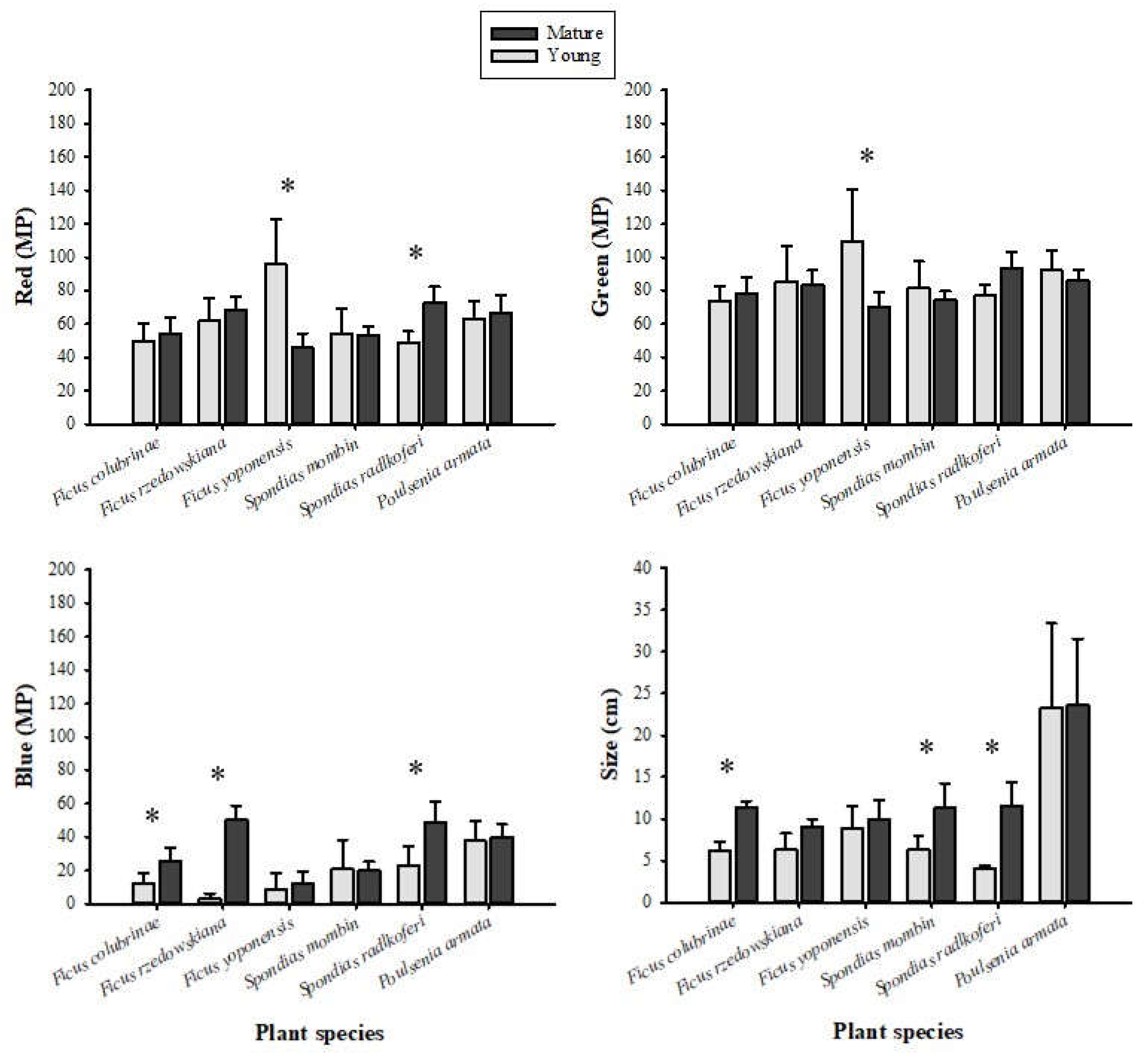

For the leaves we found significant effects of the plant species, maturity stage, and the interaction of these two variables on green and blue color. In the case of red color, the interaction had a significant impact, but not the maturity stage (

Table 2). We found significant effects of the interaction between plant species and ripening state on leaf size (

Table 2). The post hoc Tukey HSD tests revealed significant differences in RGB color intensity, with green exhibiting higher intensity than red and blue (

Figure 2). Mature leaves were significantly larger than young leaves in three of the six plant species (

Figure 2).

3.2. Food Selection

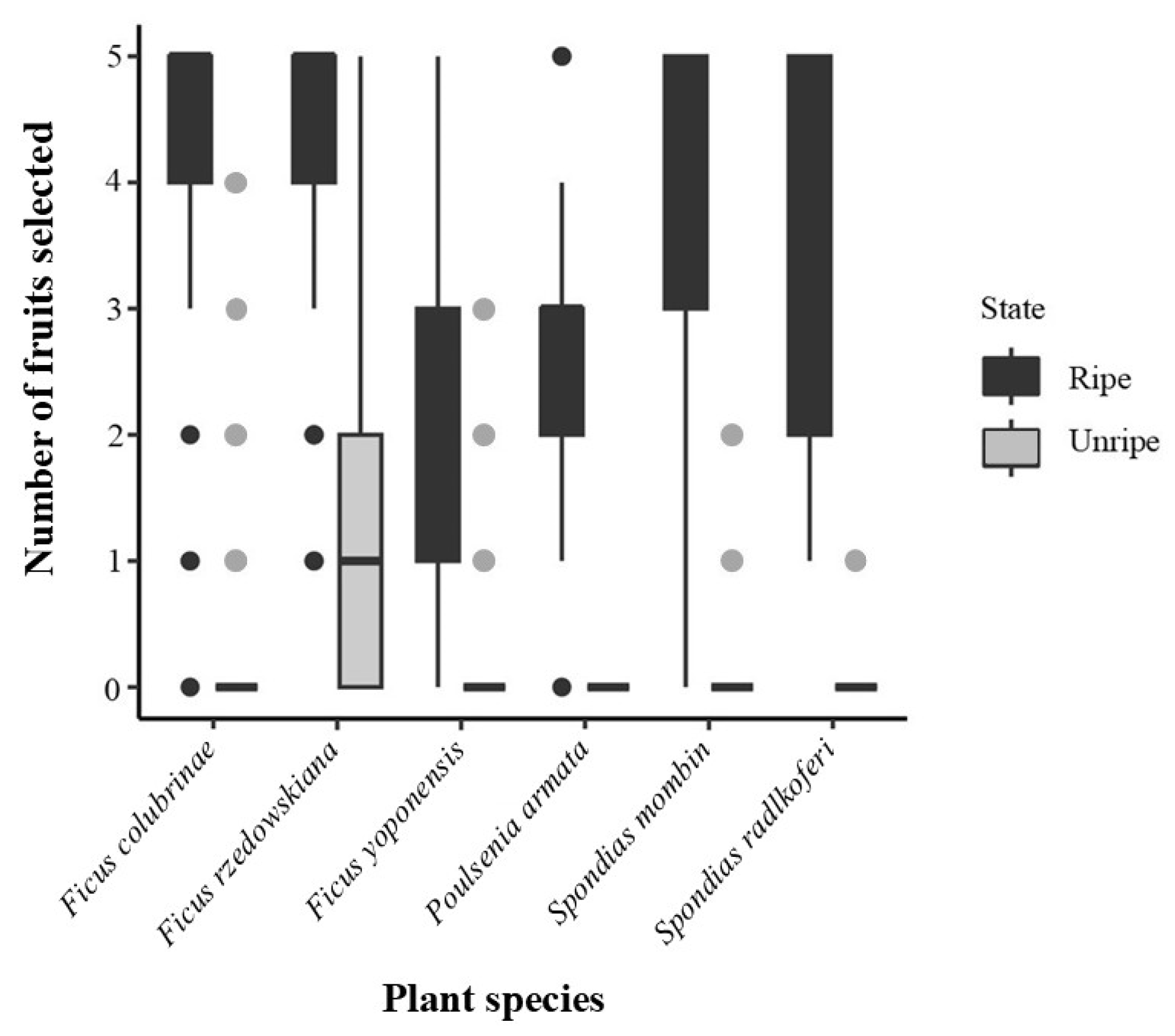

All individuals selected more ripe fruits than unripe fruits (

Figure 3). Once ripe fruits were no longer available, the monkeys selected unripe fruits of all species except for

Poulsenia armata, of which no unripe fruit was consumed (

Figure 3). From our GLMMs, Model 4 showed the lowest AIC values with a decrease of more than 100 units and an increase in the

r2 of the full model compared with Model 3 (

Table 3). The GLMMs showed that individual variability (

r2 random) accounted for approximately 5% of data in Model 4 (

Table 3).

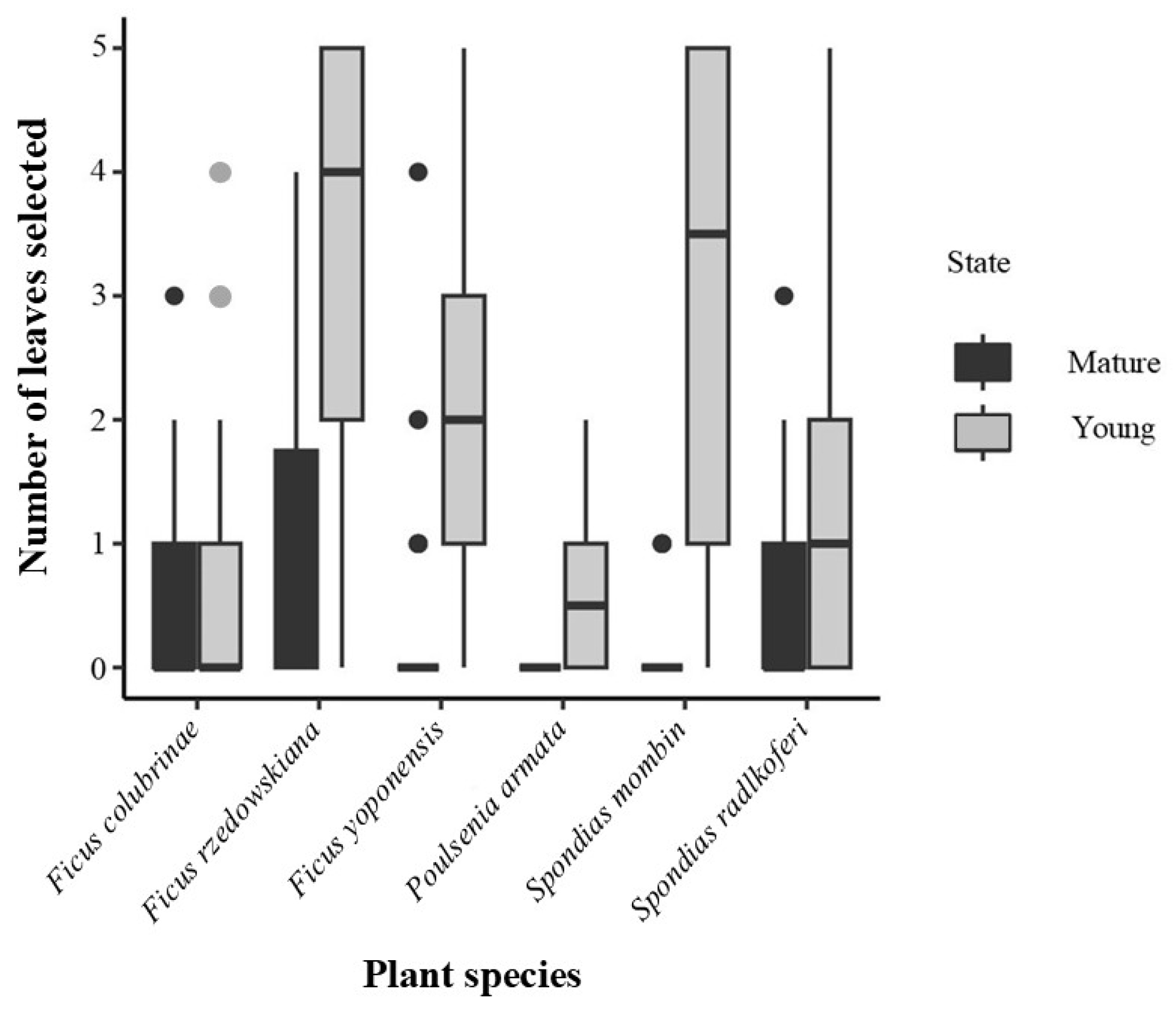

Spider monkeys selected more young than mature leaves. They consumed young leaves from all species, and mature leaves from all species except

Poulsenia armata (

Figure 4). In the GLMMs, Model 4 (fixed nested effects) had the lowest AIC values and the greatest

r2 for the full model. However, the reduction of the AIC between Model 3 and Model 4 was smaller than the reduction between Model 3 and Models 2A and 2B (

Table 4). The

r2 for the full model was similar in Models 3 and 4. Based on parsimony (simple fixed effects relations instead of nested interactions), we chose Model 3 to describe leaf selection. Model 3 showed that individual variability (

r2 random) accounted for 10% of the data for leaves (

Table 4).

4. Discussion

We found significant differences in the physical and chemical properties of unripe and ripe fruits from the same plant species. Sucrose levels increased in all species during ripening. The acidity of five of the six fruit species decreased once they reached ripeness. Color intensity changed differently across the fruit species: three increased in red, two decreased in green, and two increased in blue. The size of the fruit also increased significantly with ripening in four of the six species. The physical and chemical properties of the fruits from the six plant species we examined fell within the ranges reported for fruits consumed by other primate species (Dominy et al., 2001). We also found that leaves changed in color and size with maturity. The intensity of the blue color (in three of the six plant species) increased in mature leaves compared to young leaves, and mature leaves were larger than young leaves in three of the six plant species.

The concentration of sucrose in the fruits we analyzed here was higher than the gustatory thresholds for sucrose in Ateles geoffroyi (Laska et al., 1996) and is consistent with the sucrose concentrations found in fruits chosen by A. geoffroyi in the wild (Pablo-Rodríguez et al., 2015). Our finding that spider monkeys preferred ripe over unripe fruits supports the notion that the concentration of sucrose in ripe fruits may play a role in fruit selection. The acidity of fruits consumed by the spider monkeys in our study was also similar to the pH reported for fruits consumed by other primates (Dominy et al., 2001; Laska et al., 2000a; Ungar, 1995). The concentration of sucrose and acidity in fruits is likely to serve as a criterion to assess the ripeness, as suggested for Pongo pygmaeus, Macaca fascicularis, Hylobates lar including Ateles geoffroyi (Dominy et al., 2001; Laska et al., 2000a).

The intensity of red or blue color associated with maturity is thought to be a visual cue aiding the selection of mature fruits in some primate species, particularly those with trichromatic vision (Lomáscolo & Schaefer, 2010; Valenta et al., 2018b). The fruits we analyzed here changed color during maturation. In some cases, they increased in red and blue tones when ripe, and in some cases, they decreased in greens. Ateles geoffroyi has polymorphic vision, with males being dichromats while females may be trichromats or dichromats (Veilleux et al., 2021). However, dichromats may not be less efficient in fruit selection as vision plays only a limited role in food selection, with other senses also involved, as reported in frugivorous primates (Melin et al., 2009; 2014; Valenta et al., 2018b). We found that ripe fruits were larger than unripe fruits, which fits to the notion that size may also serve as a visual cue for fruit selection by spider monkeys, as described for other frugivorous primates (Flörchinger et al., 2010; McConkey et al., 2002).

We found that mature leaves were larger than young leaves in some plant species consumed by spider monkeys in the wild, but not in Ficus rzedowskiana, Ficus yoponensis, and Poulsenia armata. Young leaves of F. rzedowskiana, F. yoponensis, S. mombin, and P. armata were greener than mature leaves, but F. colubrinae and S. radlkoferi leaves showed the opposite pattern. Our results suggest that primate species with polymorphic color vision, such as A. geoffroyi, select young leaves based on both size and their red hues (Lucas et al., 1998; Melin et al., 2017). Primates have repeatedly been reported to use changes in leaf color and size to evaluate maturity stage, and, in some cases those characteristics are related to protein contents, toughness, and secondary metabolites (Veilleux et al., 2022).

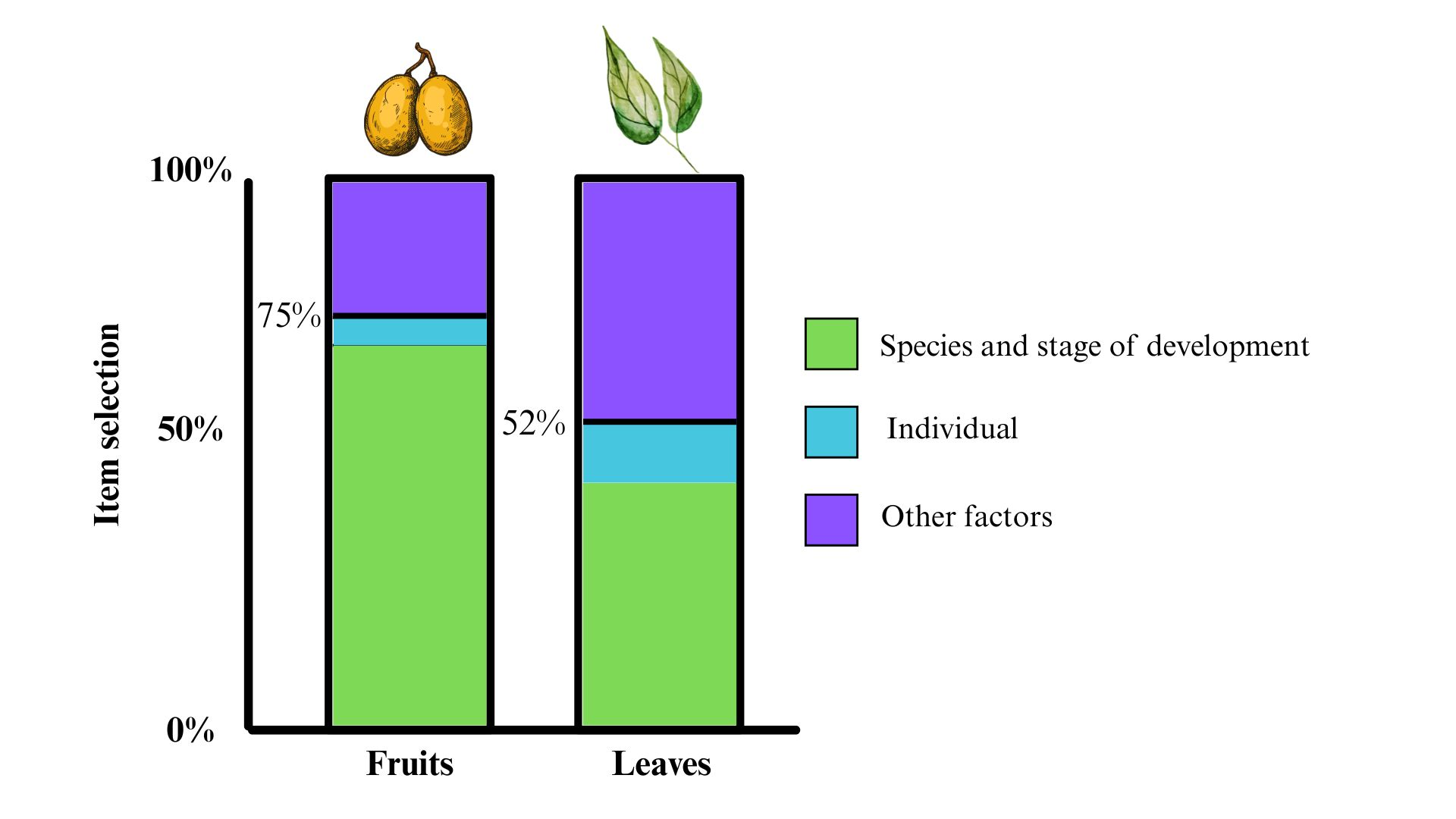

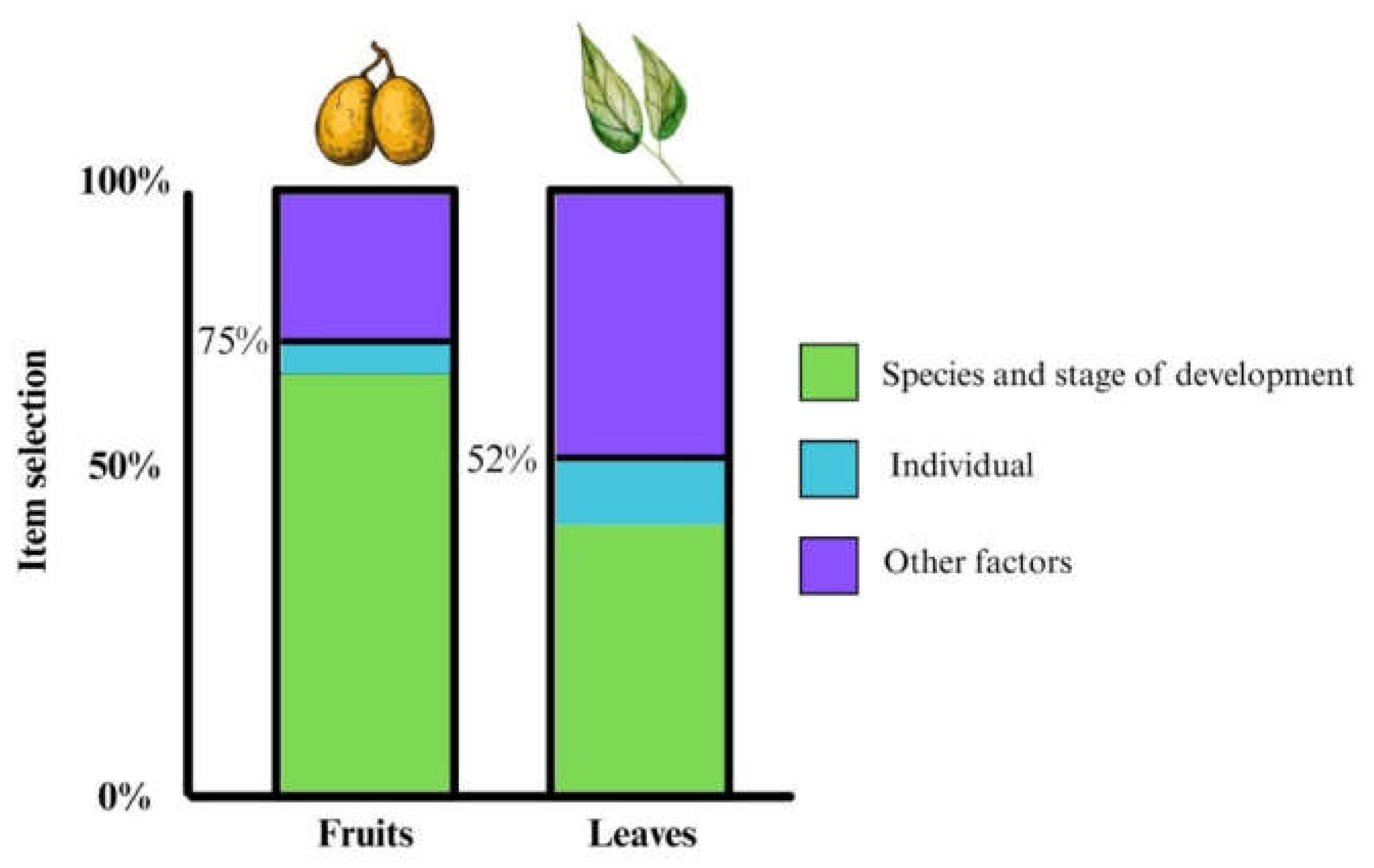

We found that 75% of fruit selection by Ateles geoffroyi was influenced by fruit maturity (State/Species + (1 Individual)). This finding suggests that most of the fruits of the plant species we studied undergo similar changes in sucrose content and pH, making them more attractive when ripe (Dominy et al., 2001; Laska et al., 2000a; Lomáscolo & Schaefer, 2010; Riba-Hernández et al., 2003, 2005; Stevenson, 2004; Ungar, 1995; Valenta et al., 2018b). However, differences in chemical properties such as sucrose content and pH levels may affect the palatability of plants. It has been proposed that A. geoffroyi selects fruits using the ratio between sweetness and sourness as a criterion (Laska et al., 2000a; Pablo-Rodríguez et al., 2015). Our findings support the idea that gustatory cues may play a role in fruit selection (Laska et al., 2000b).

We found that A. geoffroyi consistently preferred ripe fruits but also ate some unripe fruits from five of the six species tested. This is in line with findings from previous studies showing that Ateles spp. prefer ripe over unripe fruit (Di Fiore et al., 2008). However, when ripe fruits were no longer available, the spider monkeys also consumed unripe fruit. Thus, our results support the notion that these primates are flexible in their food choices depending on availability of preferred items (Laska et al., 2000b). In our study, A. geoffroyi avoided the unripe fruits of Poulsenia armata, although the sucrose levels, pH, size, and color of this fruit species were within the range of the other unripe fruits consumed. Besides the ratio between sweetness and sourness, color, and size, other chemical properties such as the content of plant secondary metabolites or fiber that we did not measure in our study may influence food selection and thus explain the avoidance of some plants.

We found that the maturity stage influenced 52% of spider monkeys' leaf selection (State + Species + (1 Individual)). This finding is consistent with those of previous studies in spider monkeys which showed a higher consumption of young than mature leaves (Felton et al., 2008, 2009; González-Zamora et al., 2009). However, other factors may also influence leaf selection. For example, fiber content and plant secondary metabolites can vary depending on ultraviolet radiation, water stress, pathogens, and plant defense strategies against herbivores (Akula & Ravishankar, 2011; de Andrade et al., 2021; War et al., 2012; Yang et al., 2018). Fiber and plant secondary metabolites have been reported to affect the selection of leaves and the assimilation of nutrients in primates such as Pongo pygmaeus, Pongo abelii, Presbytis entellus, Alouatta guariba and Alouatta palliata (Glander, 1978; Kar-Gupta & Kumar, 1994; Leighton, 1993; de Andrade et al., 2021; Schmidt et al., 2005; War et al., 2012; Windley et al., 2022). Spider monkeys may also use fiber content and the content of plant secondary metabolites to select leaves. There are reports that Ateles hybridus increases leaf consumption when fruits are scarce (De Luna et al., 2017), suggesting that for spider monkeys the assessment of the physical and chemical properties of leaves are important when fruits are scarce.

We also found individual differences in fruit and leaf selection by

A. geoffroyi, depending on the plant part. Individual variation accounted for 5% of variation in fruit selection, and 10% of variation in leaf selection. Individual variability has also reported in the selection of cultivated fruits by spider monkeys (Laska et al., 2000b). Species like

Ateles belzebuth belzebuth and

Ateles chamek prefer ripe fruits (Suarez, 2006; Wallace, 2005), and are thought to be more selective for fruits than for leaves (

Figure 5). Spider monkeys are considered as ripe-fruit specialists, and have been reported to select food items high in metabolizable energy. However, they can consume other, nutritionally less favorable food items (like leaves, flowers, bark, and roots) when their preferred foods are unavailable (Huskisson et al., 2021; Lakshminarayanan et al., 2011). This flexibility has also been reported in primates like

Pan troglodytes,

Gorilla gorilla gorilla and

Macaca fuscata, that consume a variety of fruits, leaves, and other plant parts (Huskisson et al., 2021; Lakshminarayanan et al., 2011). Such dietary flexibility may be supported by physiological adaptations, such as changes in saliva composition that occur in response to an increase in plant secondary metabolites like tannins (Ramírez-Torres et al., 2022).

5. Conclusion

Food selection in Ateles geoffroyi is influenced by the plant species and the developmental stage of food items, especially in fruits. Individual preferences also influence food selection. Future studies should consider other physical and chemical properties of food items, such as odors, texture and hardness, that may shape food selection.

Author Contributions

All authors (CERT, JERC, KGSS, ML and LTHS) contributed to the conceptualization, methodology, software, validation, formal analysis, investigation, resources, data curation, writing – original draft preparation, writing – review & editing, visualization, supervision, project administration, and funding acquisition.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The experiments reported here comply with the Guidelines for the care and use of mammals in neuroscience and behavioral research (National Research Council, 2011) and with the Mexican law (NOM-062-ZOO-1999 and NOM-051-ZOO-1995). The research protocol was approved by the board of ethics of the Secretaría de Medio Ambiente y Recursos Naturales (SEMARNAT [SGPA/DGVS/000041/22 and 09/GS-2132/05/10]).

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

The authors thank to Secretaría de Ciencia Humanidades Tecnologías e Innovación -SECIHTI for funding (CERT, 931446; KGSS, 561841; JERC, 489955; & LTHS, 36477), PADD for the review first draft, and Gildardo Castañeda and Alejandro Coyohua for their help during field work. Many thanks to all the monkeys that participated in our experiments.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Akula, R., & Ravishankar, G. A. (2011). Influence of abiotic stress signals on secondary metabolites in plants. Plant Signaling & Behavior, 6(11), 1720–1731. [CrossRef]

- Bates, D., Mächler, M., Bolker, B. M., & Walker, S. C. (2015). Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. Journal of Statistical Software, 67(1). [CrossRef]

- Ben-Shachar, M., Lüdecke, D., & Makowski, D. (2020). effect size: Estimation of Effect Size Indices and Standardized Parameters. Journal of Open Source Software, 5(56), 2815. [CrossRef]

- Caine, N. G., & Mundy, N. I. (2000). Demonstration of a foraging advantage for trichromatic marmosets (Callithrix geoffroyi) dependent on food colour. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 267(1442), 439–444. [CrossRef]

- Chapman, C. (1987). Flexibility in Diets of Three Species of Costa Rican Primates. Folia Primatologica, 49(2), 90–105. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z., Wang, F., Zhang, P., Ke, C., Zhu, Y., Cao, W., & Jiang, H. (2020). Skewed distribution of leaf color RGB model and application of skewed parameters in leaf color description model. Plant Methods, 16(1), 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Chetri, M., Odden, M., & Wegge, P. (2017). Snow leopard and himalayan Wolf: Food habits and prey selection in the central Himalayas, Nepal. PLoS ONE, 12(2), 1–16. [CrossRef]

- de Andrade Carneiro, L., Moreno, T. B., Fernandes, B. D., Souza, C. M. M., Bastos, T. S., Félix, A. P., & da Rocha, C. (2021). Effects of two dietary fiber levels on nutrient digestibility and intestinal fermentation products in captive brown howler monkeys (Alouatta guariba). American Journal of Primatology, 83(3), 1–10. [CrossRef]

- de Luna, A. G., Link, A., Montes, A., Alfonso, F., Mendieta, L., & Di Fiore, A. (2017). Increased folivory in brown spider monkeys Ateles hybridus living in a fragmented forest in Colombia. Endangered Species Research, 32(1), 123–134. [CrossRef]

- Del Bubba, M., Giordani, E., Pippucci, L., Cincinelli, A., Checchini, L., & Galvan, P. (2009), Changes in tannins, ascorbic acid and sugar content and astringent persimmons during on-tree growth and ripening and in response to different postharvest treatments. Journal of Food Composition and Analysis, 22(7-8), 668-677. [CrossRef]

- Di Fiore, Anthony, L. A. and L. D. (2008). Diets of wild spider monkeys. In Spider Monkeys: Behavior, Ecology, and Evolution of the Genus Ateles (pp. 81–137).

- Dominy, N. J., & Lucas, P. W. (2001). Ecological importance of trichromatic vision to primates. Nature, 410(6826), 363–366. [CrossRef]

- Dominy, N. J., Lucas, P. W., Osorio, D., & Yamashita, N. (2001). The sensory ecology of primate food perception. Evolutionary Anthropology: Issues, News, and Reviews, 10(5), 171–186. [CrossRef]

- Felton, A. M., Felton, A., Wood, J. T., Foley, W. J., Raubenheimer, D., Wallis, I. R., & Lindenmayer, D. B. (2009). Nutritional ecology of Ateles chamek in lowland Bolivia: How macronutrient balancing influences food choices. International Journal of Primatology, 30(5), 675–696. [CrossRef]

- Felton, A. M., Felton, A., Wood, J. T., & Lindenmayer, D. B. (2008). Diet and feeding ecology of Ateles chamek in a Bolivian semihumid forest: The importance of Ficus as a staple food resource. International Journal of Primatology, 29(2), 379–403. [CrossRef]

- Fleagle, J. G., Baden, A. L., & Gilbert, C. C. (2024). Primate Lives In: Primate adaptation and evolution. Academic press (pp. 39-40).

- Flörchinger, M., Braun, J., Böhning-Gaese, K., & Schaefer, H. M. (2010). Fruit size, crop mass, and plant height explain differential fruit choice of primates and birds. Oecologia, 164(1), 151–161. [CrossRef]

- Glander, K. E. (1978). Drinking from Arboreal Water Sources by Mantled Howling Monkeys (Alouatta palliata Gray). Folia Primatologica, 29(3), 206–217. [CrossRef]

- González-Zamora, A., Arroyo-Rodríguez, V., Chaves, Ó. M., Sánchez-López, S., Stoner, K. E., & Riba-Hernández, P. (2009). Diet of spider monkeys (Ateles geoffroyi) in mesoamerica: Current knowledge and future directions. American Journal of Primatology, 71(1), 8–20. [CrossRef]

- Hothorn, T., Bretz, F., & Westfall, P. (2008). Simultaneous inference in general parametric models. Biometrical Journal, 50(3), 346–363. [CrossRef]

- Huskisson, S. M., Egelkamp, C. L., Jacobson, S. L., Ross, S. R., & Hopper, L. M. (2021). Primates’ Food Preferences Predict Their Food Choices Even Under Uncertain Conditions. Animal Behavior and Cognition, 8(1), 69–96. [CrossRef]

- Kar-Gupta, K., & Kumar, A. (1994). Leaf chemistry and food selection by common langurs (Presbytis entellus) in Rajaji National Park, Uttar Pradesh, India. International Journal of Primatology, 15(1), 75–93. [CrossRef]

- Kassambara, A. (2022). Ggpubr: ‘Ggplot2’ Based Publication Ready Plots. https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/ggpubr/index.html.

- Kitamura, S., Yumoto, T., Poonswad, P., Chuailua, P., & Plongmai, K. (2004). Characteristics of hornbill-dispersed fruits in a tropical seasonal forest in Thailand. Bird Conservation International, 14(SPEC. ISS.), 81–88. [CrossRef]

- Kohl, K. D., Coogan, S. C. P., & Raubenheimer, D. (2015). Do wild carnivores forage for prey or for nutrients?: Evidence for nutrient-specific foraging in vertebrate predators. BioEssays, 37(6), 701–709. [CrossRef]

- Lakshminarayanan, V. R., Chen, M. K., & Santos, L. R. (2011). The evolution of decision-making under risk: Framing effects in monkey risk preferences. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 47(3), 689–693. [CrossRef]

- Lambert, J. E., & Rothman, J. M. (2015). Fallback Foods, Optimal Diets, and Nutritional Targets: Primate Responses to Varying Food Availability and Quality. Annual Review of Anthropology, 44(1), 493–512. [CrossRef]

- Laska, M. (2001). A comparison of food preferences and nutrient composition in captive squirrel monkeys, Saimiri sciureus, and Pigtail macaques, Macaca nemestrina. Physiology & Behavior, 73(1-2), 111-120. [CrossRef]

- Laska, M., Rivas Bautista, R. M., & Hernandez Salazar, L. T. (2009). Gustatory responsiveness to six bitter tastants in three species of nonhuman primates. Journal of Chemical Ecology, 35(5), 560–571. [CrossRef]

- Laska, M., Salazar, L. T. H., Rodriguez Luna, E., & Hudson, R. (2000a). Gustatory responsiveness to food-associated acids in the spider monkey (Ateles geoffroyi). Primates, 41(2), 213–221. [CrossRef]

- Laska, M., Salazar, L. T. H., & Luna, E. R. (2000b). Food preferences and nutrient composition in captive spider monkeys, Ateles geoffroyi. International Journal of Primatology, 21(4), 671–683. [CrossRef]

- Laska, M., Sanchez, E. C., Rivera, J. A. R., & Luna, E. R. (1996). Gustatory thresholds for food-associated sugars in the spider monkey (Ateles geoffroyi). American Journal of Primatology, 39(3), 189–193. [CrossRef]

- Laska, M., Sanchez, E. C., & Luna, E. R. (1998). Relative taste preferences for food-associated sugars in the spider monkey (Ateles geoffroyi). Primates, 39(1), 91–96. [CrossRef]

- Leighton, M. (1993). Modeling dietary selectivity by Bornean orangutans: Evidence for integration of multiple criteria in fruit selection. International Journal of Primatology, 14(2), 257–313. [CrossRef]

- Lomáscolo, S. B., & Schaefer, H. M. (2010). Signal convergence in fruits: A result of selection by frugivores? Journal of Evolutionary Biology, 23(3), 614–624. [CrossRef]

- Lucas, P. W., Darvell, B. W., Lee, P. K. D., Yuen, T. D. B., & Choong, M. F. (1998). Colour Cues for Leaf Food Selection by Long-Tailed Macaques (Macaca fascicularis) with a New Suggestion for the Evolution of Trichromatic Colour Vision. Folia Primatologica, 69(3), 139–152. [CrossRef]

- Martins, V. A., Magnusson, N., & Laska, M. (2023). Go for lipids! Food preferences and nutrient composition in zoo-housed white-faced sakis, Pithecia pithecia. International Journal of Primatology, 44(2), 341-356. [CrossRef]

- McConkey, K. R., Aldy, F., Ario, A., & Chivers, D. J. (2002). Selection of fruit by gibbons (Hylobates muelleri x agilis) in the rain forests of Central Borneo. International Journal of Primatology, 23(1), 123–145. [CrossRef]

- Melin, A. D., Hiramatsu, C., Parr, N. A., Matsushita, Y., Kawamura, S., & Fedigan, L. M. (2014). The Behavioral Ecology of Color Vision: Considering Fruit Conspicuity, Detection Distance and Dietary Importance. International Journal of Primatology, 35(1), 258–287. [CrossRef]

- Melin, A. D., Veilleux, C. C., Janiak, M. C., Hiramatsu, C., Sánchez-Solano, K. G., Lundeen, I. K., Webb, S. E., Williamson, R. E., Mah, M. A., Murillo-Chacon, E., Schaffner, C. M., Hernández-Salazar, L., Aureli, F., & Kawamura, S. (2022). Anatomy and dietary specialization influence sensory behaviour among sympatric primates. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 289(1981). [CrossRef]

- Melin, A. D., Fedigan, L. M., Hiramatsu, C., Hiwatashi, T., Parr, N., & Kawamura, S. (2009). Fig foraging by dichromatic and trichromatic cebus capucinus in a tropical dry forest. International Journal of Primatology, 30(6), 753–775. [CrossRef]

- Melin, A. D., Khetpal, V., Matsushita, Y., Zhou, K., Campos, F. A., Welker, B., & Kawamura, S. (2017). Howler monkey foraging ecology suggests convergent evolution of routine trichromacy as an adaptation for folivory. Ecology and Evolution, 7(5), 1421–1434. [CrossRef]

- Pablo-Rodríguez, M., Hernández-Salazar, L. T., Aureli, F., & Schaffner, C. M. (2015). The role of sucrose and sensory systems in fruit selection and consumption of Ateles geoffroyi in Yucatan, Mexico. Journal of Tropical Ecology, 31(3), 213–219. [CrossRef]

- Provenza, F. D., Villalba, J. J., Haskell, J., MacAdam, J. W., Griggs, T. C., & Wiedmeier, R. D. (2007). The value to herbivores of plant physical and chemical diversity in time and space. Crop Science, 47(1), 382–398. [CrossRef]

- Ramírez-Torres, C. E., Espinosa-Gómez, F. C., Morales-Mávil, J. E., Eduardo Reynoso-Cruz, J., Laska, M., & Hernández-Salazar, L. T. (2022). Influence of tannic acid concentration on the physicochemical characteristics of saliva of spider monkeys (Ateles geoffroyi). PeerJ, 10, 1–21. [CrossRef]

- Regan, B. C., Julliot, C., Simmen, B., Viénot, F., Charles–Dominique, P., & Mollon, J. D. (2001). Fruits, foliage and the evolution of primate colour vision. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences, 356(1407), 229-283. [CrossRef]

- Riba-Hernández, P., Stoner, K. E., & Lucas, P. W. (2003). The sugar composition of fruits in the diet of spider monkeys (Ateles geoffroyi) in tropical humid forest in Costa Rica. Journal of Tropical Ecology, 19(6), 709–716. [CrossRef]

- Riba-Hernández, P., Stoner, K. E., & Lucas, P. W. (2005). Sugar concentration of fruits and their detection via color in the central american spider monkey (Ateles geoffroyi). American Journal of Primatology, 67(4), 411–423. [CrossRef]

- Rozin, P. (1976). The Selection of Foods by Rats, Humans, and Other Animals. Advances in the Study of Behavior, 6(C), 21–76. [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Solano, K. G., Morales-Mávil, J., Laska, M., Melin, A., & Hernández-Salazar, L. T. (2020). Visual detection and fruit selection by the mantled howler monkey (Alouatta palliata). American Journal of Primatology, 82(10). [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Solano, K. G., Reynoso-Cruz, J. E., Guevara, R., Morales-Mávil, J. E., Laska, M., & Hernández-Salazar, L. T. (2022). Non-visual senses in fruit selection by the mantled howler monkey (Alouatta palliata). Primates, 63(3), 293–303. [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, D. A., Kerley, M. S., Dempsey, J. L., Porton, I. J., Porter, J. H., Griffin, M. E., Ellersieck, M. R., & Sadler, W. C. (2005). Fiber digestibility by the orangutan (Pongo abelii): In vitro and in vivo. Journal of Zoo and Wildlife Medicine, 36(4), 571–580. [CrossRef]

- Sclafani, A. (2001). Psychobiology of food preferences. International Journal of Obesity, 25, S13–S16. [CrossRef]

- Silveira, P., Valler, Í. W., Hirano, Z. M. B., Dada, A. N., Laska, M., & Hernández-Salazar, L. T. (2024). Food preferences and nutrient composition in captive Southern brown howler monkeys, Alouatta guariba clamitans. Primates, 65(2), 115-124. [CrossRef]

- Stevenson, P. R. (2004). Fruit Choice by Woolly Monkeys in Tinigua National Park, Colombia. International Journal of Primatology, 25(2), 367–381. [CrossRef]

- Stroebele, N., & De Castro, J. M. (2004). Effect of ambience on food intake and food choice. Nutrition, 20(9), 821–838. [CrossRef]

- Suarez, S. A. (2006). Diet and travel costs for spider monkeys in a nonseasonal, hyperdiverse environment. Int J Primatol 27:411–436. [CrossRef]

- Ungar, P. S. (1995). Fruit preferences of four sympatric primate species at Ketambe, northern Sumatra, Indonesia. International Journal of Primatology, 16(2), 221–245. [CrossRef]

- Valenta, K., Burke, R. J., Styler, S. A., Jackson, D. A., Melin, A. D., & Lehman, S. M. (2013). Colour and odour drive fruit selection and seed dispersal by mouse lemurs. Scientific Reports, 3. [CrossRef]

- Valenta, K., Kalbitzer, U., Razafimandimby, D., Omeja, P., Ayasse, M., Chapman, C. A., & Nevo, O. (2018a). The evolution of fruit colour: phylogeny, abiotic factors and the role of mutualists. Scientific Reports, 8(1), 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Valenta, K., Nevo, O., & Chapman, C. A. (2018b). Primate Fruit Color: Useful Concept or Alluring Myth? International Journal of Primatology, 39(3), 321–337. [CrossRef]

- Veilleux, C. C., Dominy, N. J., & Melin, A. D. (2022). The sensory ecology of primate food perception, revisited. Evolutionary Anthropology: Issues, News, and Reviews, 31(6), 281-301. [CrossRef]

- Villalba, J. J., Provenza, F. D., & Bryant, J. P. (2002). Consequences of the interaction between nutrients and plant secondary metabolites on herbivore selectivity: Benefits or detriments for plants? Oikos, 97(2), 282–292. [CrossRef]

- Wallace, R. B. (2005). Seasonal variations in diet and foraging behavior of Ateles chamek in a southern Amazonian tropical forest. Int J Primatol 26:1053–1075. [CrossRef]

- War, A. R., Paulraj, M. G., Ahmad, T., Buhroo, A. A., Hussain, B., Ignacimuthu, S., & Sharma, H. C. (2012). Psb-7-1306. Plant Signaling and Behavior, 7(10), 1306–1320.

- Windley, H. R., Starrs, D., Stalenberg, E., Rothman, J. M., Ganzhorn, J. U., & Foley, W. J. (2022). Plant secondary metabolites and primate food choices: A meta-analysis and future directions. American Journal of Primatology, 84(8), 1–18. [CrossRef]

- Yadav, S. P., Ibaraki, Y., & Gupta, S. D. (2010). Estimation of the chlorophyll content of micropropagated potato plants using RGB based image analysis. Plant Cell, Tissue and Organ Culture, 100(2), 183–188. [CrossRef]

- Yang, L., Wen, K. S., Ruan, X., Zhao, Y. X., Wei, F., & Wang, Q. (2018). Response of plant secondary metabolites to environmental factors. Molecules, 23(4), 1–26. [CrossRef]

- Zhang D (2023). rsq: R-Squared and Related Measures_. R package version 2.6. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=rsq.

Figure 1.

Physical and chemical properties of fruits (mean + SD) consumed by spider monkeys in Los Tuxtlas region, Veracruz, Mexico, from March to August 2022. (*) Indicates significant Tukey HSD tests (p < 0.01).

Figure 1.

Physical and chemical properties of fruits (mean + SD) consumed by spider monkeys in Los Tuxtlas region, Veracruz, Mexico, from March to August 2022. (*) Indicates significant Tukey HSD tests (p < 0.01).

Figure 2.

Physical and chemical properties of leaves (mean + SD) consumed by spider monkeys in Los Tuxtlas region, Veracruz, Mexico, from March to August 2022. (*) Indicates significant Tukey HSD tests (p < 0.01).

Figure 2.

Physical and chemical properties of leaves (mean + SD) consumed by spider monkeys in Los Tuxtlas region, Veracruz, Mexico, from March to August 2022. (*) Indicates significant Tukey HSD tests (p < 0.01).

Figure 3.

Number of unripe and ripe fruits selected from six plant species by spider monkeys in Catemaco, Veracruz, Mexico, from March to August 2022. Ripe fruits are represented in black, while unripe fruits are represented in grey. Plots represent the monkey's selection of fruits (mean + SD).

Figure 3.

Number of unripe and ripe fruits selected from six plant species by spider monkeys in Catemaco, Veracruz, Mexico, from March to August 2022. Ripe fruits are represented in black, while unripe fruits are represented in grey. Plots represent the monkey's selection of fruits (mean + SD).

Figure 4.

Number of young and mature leaves selected from six plant species reported in the diet of spider monkeys in Catemaco, Veracruz, Mexico, from March to August 2022. Mature leaves are represented in black, while young ones are represented in grey. Plots represent the monkey's selection of leaves (mean + SD).

Figure 4.

Number of young and mature leaves selected from six plant species reported in the diet of spider monkeys in Catemaco, Veracruz, Mexico, from March to August 2022. Mature leaves are represented in black, while young ones are represented in grey. Plots represent the monkey's selection of leaves (mean + SD).

Figure 5.

Proposed model of the factors involved in fruit and leaf selection in Ateles geoffroyi.

Figure 5.

Proposed model of the factors involved in fruit and leaf selection in Ateles geoffroyi.

Table 1.

Results of ANOVA of the physical and chemical properties of fruits consumed by spider monkeys in Los Tuxtlas region, Veracruz, Mexico, from March to August 2022.

Table 1.

Results of ANOVA of the physical and chemical properties of fruits consumed by spider monkeys in Los Tuxtlas region, Veracruz, Mexico, from March to August 2022.

| Fruit physical-chemical characteristics |

Variable |

F |

p |

Partial η2

|

| Sucrose |

Species |

(5, 237) = 68.18 |

<0.001 |

0.20 |

| Ripe state |

(1, 237) = 1002.34 |

<0.001 |

0.58 |

| Interaction |

(5, 237) = 30.54 |

<0.001 |

0.09 |

| pH |

Species |

(5, 237) = 151.81 |

<0.001 |

0.46 |

| Ripe state |

(1, 237) = 206.20 |

<0.001 |

0.13 |

| Interaction |

(5, 237) = 86.38 |

<0.001 |

0.26 |

| Red |

Species |

(5, 237) = 46.68 |

<0.001 |

0.16 |

| Ripe state |

(1, 237) = 563.43 |

<0.001 |

0.37 |

| Interaction |

(5, 237) = 94.18 |

<0.001 |

0.31 |

| Green |

Species |

(5, 237) = 59.275 |

<0.001 |

0.30 |

| Ripe state |

(1, 237) = .087 |

0.768 |

<0.001 |

| Interaction |

(5, 237) = 92.553 |

<0.001 |

0.46 |

| Blue |

Species |

(5, 237) = 20.19 |

<0.001 |

0.20 |

| Ripe state |

(1, 237) = 66.28 |

<0.001 |

0.13 |

| Interaction |

(5, 237) = 22.23 |

<0.001 |

0.22 |

| Size |

Species |

(5, 237) = 544.69 |

<0.001 |

0.81 |

| Ripe state |

(1, 237) = 255.20 |

<0.001 |

0.08 |

| Interaction |

(5, 237) = 30.08 |

<0.001 |

0.04 |

Table 2.

ANOVAs of the physical and chemical properties of leaves consumed by spider monkeys in Los Tuxtlas region, Veracruz, Mexico, from March to August 2022.

Table 2.

ANOVAs of the physical and chemical properties of leaves consumed by spider monkeys in Los Tuxtlas region, Veracruz, Mexico, from March to August 2022.

| Leaves physical-chemical characteristics |

Variables |

F |

p |

Partial η2

|

| Red |

Species |

(5, 228) = 13.420 |

<0.001 |

0.13 |

| Mature state |

(1, 228) = 1.667 |

0.198 |

0.003 |

| Interaction |

(5, 228) = 40.194 |

<0.001 |

0.40 |

| Green |

Species |

(5, 228) = 6.638 |

<0.001 |

0.09 |

| Mature state |

(1, 228) = 10.147 |

0.001 |

0.03 |

| Interaction |

(5, 228) = 17.911 |

<0.001 |

0.25 |

| Blue |

Species |

(5, 228) = 49.38 |

<0.001 |

0.31 |

| Mature state |

(1, 228) = 148.32 |

<0.001 |

0.18 |

| Interaction |

(5, 228) = 36.26 |

<0.001 |

0.23 |

| Size |

Species |

(5, 228) = 88.989 |

<0.001 |

0.60 |

| Mature state |

(1, 228) = 46.545 |

<0.001 |

0.06 |

| Interaction |

(5, 228) = 4.295 |

<0.001 |

0.03 |

Table 3.

Results of the models for fruits collected in Los Tuxtlas region, Veracruz, Mexico, from March to August 2022.

Table 3.

Results of the models for fruits collected in Los Tuxtlas region, Veracruz, Mexico, from March to August 2022.

| Model |

AIC |

r2 fixed effects |

r2 random |

r2 full model |

| 1. Individual |

2495.6 |

- |

0.029 |

0.029 |

| 2A. State + (1 Individual) |

1699.9 |

0.566 |

0.045 |

0.611 |

| 2B. Species + (1 Individual) |

2388.4 |

0.033 |

0.091 |

0.12 |

| 3. State + Species + (1 Individual) |

1592.7 |

0.65 |

0.042 |

0.692 |

| 4. State/Species + (1 Individual) |

1484.9 |

0.694 |

0.051 |

0.746 |

Table 4.

Results of the models for leaves collected in Los Tuxtlas region, Veracruz, Mexico, from March to August 2022.

Table 4.

Results of the models for leaves collected in Los Tuxtlas region, Veracruz, Mexico, from March to August 2022.

| Model |

AIC |

r2 fixed effects |

r2 random |

r2 full model |

| 1. Individual |

1881.8 |

- |

0.073 |

0.073 |

| 2A. State + (1 Individual) |

1587.5 |

0.214 |

0.099 |

0.314 |

| 2B. Species + (1 Individual) |

1706.5 |

0.132 |

0.074 |

0.207 |

| 3. State + Species + (1 Individual) |

1412.2 |

0.418 |

0.101 |

0.519 |

| 4. State/Species + (1 Individual) |

1355.4 |

0.438 |

0.107 |

0.546 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).