1. Introduction

Metabolic syndrome (MetS) involves a group of risk factors for atherosclerosis that include obesity, glucose intolerance, dyslipidemia, and hypertension. The prevalence of MetS has been increasing every year due to unhealthy diets and a lack of exercise, and MetS has become a social problem due to populations' increased risks of developing atherosclerotic diseases and death [

1]. Since MetS has a complex etiology and ultimately leads to irreversible cardiovascular dysfunction [

2,

3], its early detection and the prevention of its progression are particularly important during the stage when the vascular dysfunction can be reversed. In the field of ophthalmology, it is recognized that MetS is associated with several ophthalmic diseases such as retinal vein occlusion development and the progression of diabetic retinopathy [

4,

5].

Laser speckle flowgraphy (LSFG) is a technique that can be used noninvasively and reproducibly to quantify ocular blood flow [

6,

7,

8]. The measured ocular blood flow value is displayed as the mean blur rate (MBR). The MBR has been reported to be influenced by background and systemic conditions such as age-related changes and sex differences [

9,

10,

11,

12]. The pulse waveform parameters of the MBR that are synchronized with the heart rate and reported to be related to systemic vascular function include the blowout score (BOS), the blowout time (BOT), and the rising rate (RR) [

13,

14,

15,

16]. For example, associations between the BOS and macrovascular arterial stiffness [

13] and left diastolic ventricular function [

14] have been reported, while the BOT is associated with arterial stiffness [

15] and systemic peripheral vascular resistance [

16] and the RR is associated with left ventricular systolic function [

14]. Although the items obtained and evaluated when using LSFG are not assigned units, interindividual comparisons are possible when analyses are conducted using data from various basic and clinical studies [

17,

18,

19].

We thus hypothesized that MetS and its components may lead to arteriosclerosis and influence the onset of ocular diseases via the ocular blood flow. One of our research group's earlier studies examined the ocular blood flow in individuals with sleep apnea syndrome who met the diagnostic criteria for MetS, and in subjects with MetS we observed decreases in the MBR in the optic nerve head (ONH) and choroid area and the BOS in the choroidal region [

20]. However, that study was of a small number of older sleep apnea syndrome patients (n=76) with an average age in the 60s. An additional study limitation was that although we performed a multiple regression analysis, the numbers of male and female patients were not balanced.

Further research is thus necessary to clarify the precise relationships between MetS and its components and ocular blood flow. We conducted the present study to re-investigate the ocular blood flow in a large number of males with MetS in a comparison with age-adjusted healthy subjects.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Subjects

Between December 2016 and December 2018 at the JCHO Tokyo Kamata Medical Center, 853 males who underwent an ocular blood flow examination by LSFG during physical examinations . A total of 138 subjects met the diagnostic criteria for MetS and were placed in the MetS group (49.95 ± 8.21 years). To create conditions that had fewer background factors, we then compared the extracted subjects who did not exhibit all of the abnormalities concerning glucose tolerance, hypertension, and dyslipidemia by conducting propensity score matching using age as the covariate. A final total of 138 healthy males then comprised the control group (49.96 ± 8.24 years). Subjects who were found to have experienced a cardiovascular event, cerebrovascular event, systemic disease such as arrhythmia, ocular disease (glaucoma, uveitis, optic neuropathy, retinal diseases, etc.), or intraocular surgery were excluded due to the potential impact on their ocular blood flow.

2.2. Study Design

This was a retrospective analysis that used the data obtained in our previous studies [

9,

10]. The study information was made available to the public, and subjects had the opportunity to opt out of participation in the study. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Toho University Omori Hospital (approval no. M23044) and conducted according to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. Although this study was a sub-analysis of the two studies reported by Kobayashi et al. in 2019 [

9,

10], after renewed submission to and approval by the Ethics Committee, we performed our analysis in the same patients who were once again given the option to opt out if so desired.

2.3. LSFG Measurements

The LSFG measurements were performed as we described [

9,

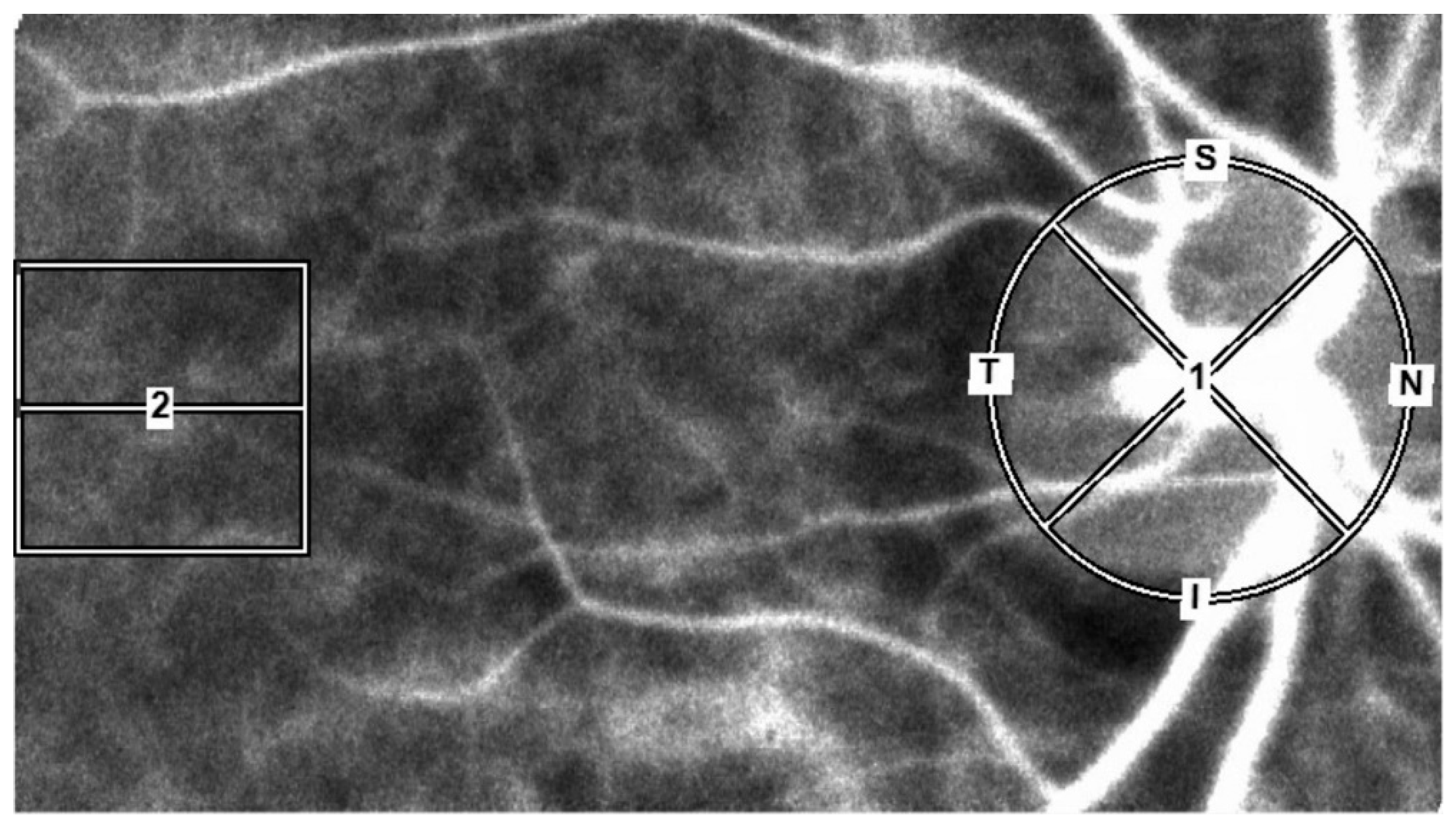

10]. Briefly, an LSFG-NAVI™ instrument (Softcare Co., Fukuoka, Japan) was used to measure the subject's MBR after an elliptical circle was set along the papillary margin for the ONH blood flow and a 150×150-pixel square was set in the macula for the choroidal blood flow. The use of this method avoided measurements of the retinal vessels (

Figure 1).

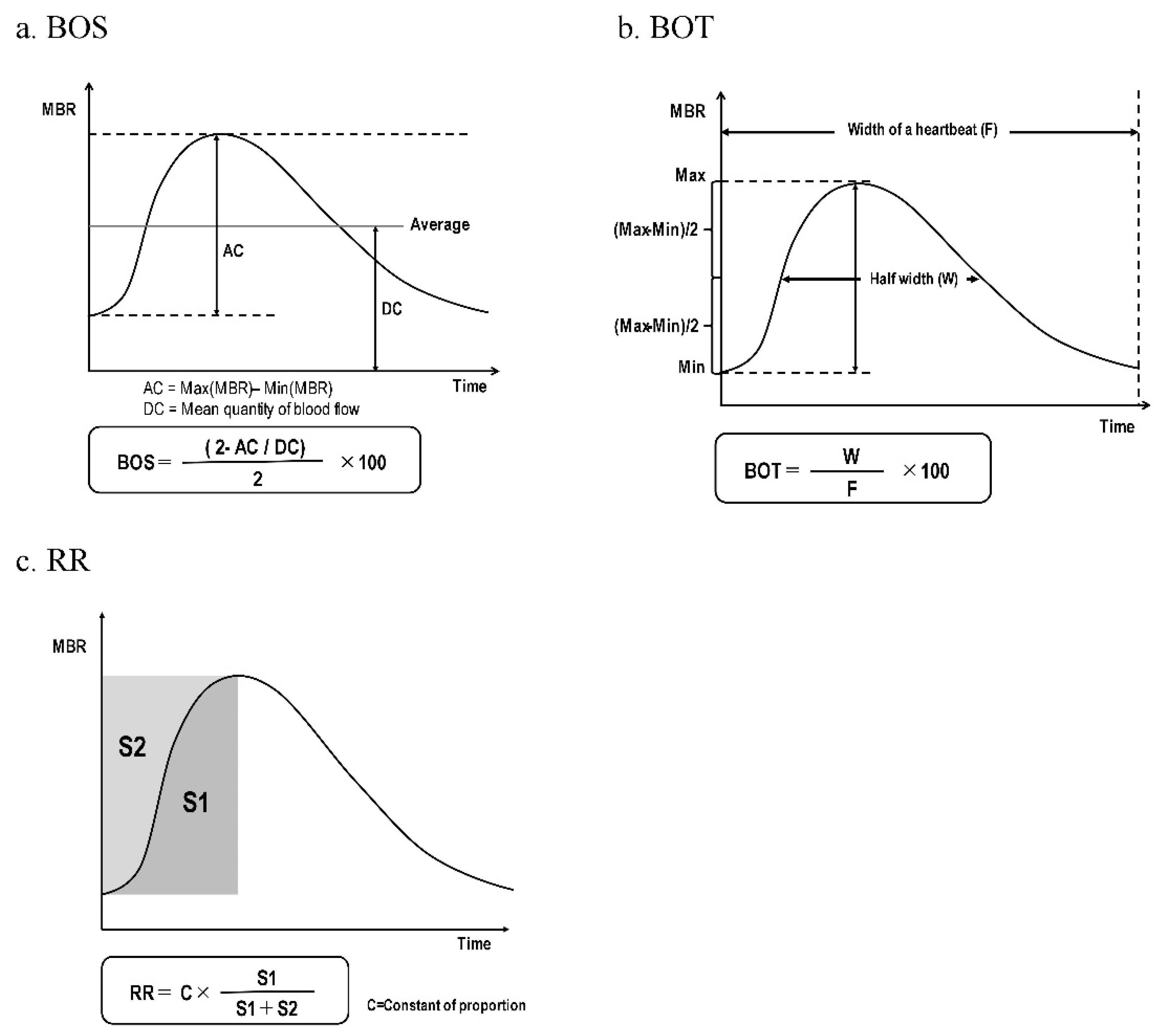

For the ONH region, the MBR was calculated using two gradations, i.e., the vascular region (-vessel), and the tissue region (-tissue), for the entire ONH region (-all). We then averaged the data obtained from 4 sec of continuous ocular blood flow measurements by the LSFG instrument in order to calculate the MBR of the ONH region and the MBR of the choroidal region (-choroid) for one heartbeat. The BOS, BOT, and RR were calculated from the MBR using the LSFG instrument's analytical software (ver. 3.2.3.0, Softcare Co.) (Figre 2, 2a–e) [

21,

22].

All of the ophthalmic parameters examined were from each subject's right eye.

2.4. Systemic, Laboratory, and Ophthalmic Parameter Measurements

The systemic parameters included age, body mass index (BMI, kg/m2), waist circumference (cm), systolic blood pressure (SBP, mmHg), diastolic blood pressure (DBP, mmHg) , and heart rate (beat per minute, bpm), with clinical biochemistry and hematology parameters obtained from fasting morning blood draws. Ophthalmic parameters were collected from the LSFG data, along with the spherical refraction (diopter, D), and intraocular pressure (IOP mmHg) measured by non-contact tonometry. The subjects' fasting blood sugar (FBS, mg/dL), triglycerides (TG, mg/dL), high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C, mg/dL), low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C, mg/dL), hematocrit (%), and glycated hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c %) values were assessed with the use of fasting morning blood samples.

2.5. Diagnosis of MetS

The diagnostic criteria for MetS were based on the diagnostic criteria published by the Japanese Metabolic Syndrome Diagnostic Study Committee [

23]. MetS is defined as abdominal obesity (waist ≥85 cm) along with two or more of the following three criteria: (1) hypertension: SBP ≥130 mmHg or DBP ≥85 mmHg or a history of hypertension treatment; (2) dyslipidemia: HDL-C <40 mg/dL or TG ≥150 mg/dL or a history of dyslipidemia treatment; and (3) glucose tolerance: FBS ≥110 mg/dL or having been diagnosed with diabetes mellitus.

2.6. Statistical Analyses

We compared all of the above-mentioned parameters between the MetS and control groups by unpaired t-test and χ

2-test. Single and multiple regression analyses were used to determine the relationships among the prevalence of MetS, its components, the MBR, and the parameters that showed a significant difference between the MetS and control groups. All statistical analyses were performed by EZR (Saitama Medical Center, Jichi Medical University, Saitama, Japan, ver. 1.54) [

24]. Probability (p)-values <0.05 were considered significant. Data for the continuous variables are presented as the mean ± standard deviation.

3. Results

After the propensity score matching of the control groups using age as covariates, 138 males were classified in the MetS group and 138 males comprised the control group (49.95 ± 8.21 vs. 49.96 ± 8.24 yrs, p=0.99).

Table 1 summarizes the subject backgrounds for each group.

Compared to the control group, the MetS group had significantly higher systemic or laboratory parameters (BMI, SBP, DBP, FBS, TG, hematocrit, and HbA1c) and significantly lower HDL-C values. Among the ocular parameters, a significantly higher IOP (p=0.021) was observed in the MetS group compared to the control group.

Table 2 provides the results of a comparison of the groups' MBR values. There was a significantly lower MBR-choroid (p=0.02) in the MetS subjects versus the control subjects. In the ONH region, there were no significant differences between the MetS and control groups for the MBR-all (p=0.28), MBR-tissue (p=0.19), and MBR-vessel (p=0.85).

The comparison of LSFG waveform parameters between the MetS and control groups is summarized in

Table3. The BOS-All (p<0.001), BOS-Tissue (p<0.001), and BOS-Vessel (p=0.002) were significantly higher in the MetS group versus the control group. The BOS-Choroid values in the MetS group tended to be lower than those of the control group (p=0.07). The MetS group's RR-all (p<0.001), RR-tissue (p<0.001), RR-vessel (p<0.001), and RR-Choroid (p<0.001) values were significantly lower than those of the control group. There was no significant difference in the BOT results between the two groups.

We next conducted a single-regression analysis to investigate whether the number of MetS components contributes independently to the MBR-Choroid value (

Table 4). The number of MetS components was significantly negatively correlated only with the MBR-Choroid among the evaluated parameters (r = −0.14, p=0.02).

We then performed single and multiple regression analyses to determine which MetS component was most strongly correlated with the MBR-Choroid. The explanatory variables were the factors that were correlated significantly with objective variables by the single regression analysis (

Table 5). Because the correlation coefficients were >0.8 between HbA1c and FBS and between BMI and waist circumference, we selected HbA1c and waist circumference as the explanatory variables which showed stronger correlations with the objective variables. The analysis revealed that HbA1c was the only factor that contributed independently to the MBR-Choroid (β = −0.45, t-value = −2.25, p=0.03).

4. Discussion

MetS has been recognized as an important risk factor for not only systemic arteriosclerotic and atherosclerotic diseases but also ocular diseases such as glaucoma and retinal vein occlusion [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]. It would thus be very informative to determine the effects of MetS on micro-hemodynamics before the onset of systemic or ocular diseases. One of our research groups' focused on the relationship between ocular hemodynamics and MetS, and we observed that the ocular blood flow in sleep apnea syndrome patients who had MetS was decreasing the MBR in the ONH, choroid, and the BOS-Choroid [

20]. There were several matters to resolve in that study, however. It was of a small number of elderly subjects and both genders were included, although a multiple regression analysis was performed. Since gender-related differences in ocular microcirculation have been revealed, further investigation was needed.

In the present study, we re-examined the ocular blood flow obtained by LSFG in a large number of male subjects with MetS compared with healthy subjects adjusted by age. All of the enrolled subjects were selected from among the individuals who underwent physical examinations. As a result, the present subjects were >10 years younger than the subjects in the earlier study [

20], and there was also a between-study difference in the duration of MetS in the earlier study (MetS group 49.95 ± 8.21 years).

Our comparisons of the background factors between the present MetS and control groups matched for age demonstrated that the heart rate, hematocrit, and IOP in the MetS group were significantly higher those of the control group, other than components of MetS. It has been reported that heart rate was associated with obesity and diabetes mellitus, both of which are MetS components [

25], and high heart rate is an independent predictor of long-term death [

26,

27]. Several descriptions of relationships between MetS and ocular findings are available, and it has been reported that subjects with a greater number of MetS components had higher IOP values [

28]. Relationships between erythrocyte parameters and MetS and its components were described [

29]. Together the above-cited reports may support our present findings.

Our analysis of the ocular blood flow in the present MetS and control groups revealed that although the MBR-choroid was significantly lower in the MetS group, there was no significant difference in the MBR values in the 'all' section of the ONH (

Table 2). This may be because the present subjects were >10 years younger than the subjects in the previous reports, in addition to the difference in the duration of MetS in the earlier studies. In the next 10 years, our subjects' MBR-tissue and MBR-all values could also become different and should thus be examined in a continuous study. In other words, our findings indicate that decreasing choroidal blood flow shown by the MBR may be present from the early stage of MetS.

As summarized in

Table 3, we compared the MetS and control groups' values for the BOS, BOT, and RR, which are pulse waveform parameters of LSFG. Although the BOS-Tissue and Vessel data were higher and the RR was lower in the MetS group, no significant differences were observed for the BOT. Our group has reported that the BOT and BOS in the ONH were significantly negatively correlated with carotid arterio-atherosclerotic formation [

13], and heart rate was reported to be strongly positively correlated with the BOS [

20]. We speculate that this result shows that the heart rate contributes more strongly to the BOS compared to atherosclerotic changes in the early stages of MetS. Regarding the RR, especially in the choroid area, our group has demonstrated that the RR reflects left ventricular function [

14]. It was reported that MetS components may have a substantial effect on the development of cardiac heart failure [

30]. It was also proposed that MetS poses a risk of preclinical heart failure [

31]. Further investigations are thus necessary to determine the exact relationships between cardiac hemodynamics obtained by echocardiography and the ocular blood flow of individuals with MetS.

Table 4 provides the results of the single regression analysis conducted to determine whether the accumulation of MetS components affects the MBR-Choroid. Among the background factors examined, only the number of MetS components showed a significant correlation; it was significantly negatively correlated with MBR-Choroid. This result re-confirmed that the overlap of MetS components is one of the important factors for defining the ocular blood flow in the choroid.

Finally, we conducted single and multiple regression analyses to determine the factor(s) that most affect the MBR-Choroid among the MetS-related factors (

Table 5). The multiple regression analysis identified HbA1c as a factor contributing independently to the MBR-Choroid. Our findings clarified that at the early stage of MetS, (

i) the MetS subjects had lower ONH and choroid RR values (which reflect left ventricular function), and (

ii) the MBR in the choroid area is decreasing in parallel with the accumulation of MetS components. Our results also clarified that the MetS component with the strongest influence to the MBR-Choroid was the HbA1c value, which is a blood sugar- related factor. Studies of patients with diabetes have reported that the ocular blood flow is reduced even before the onset of diabetic retinopathy [

32,

33] and there is a gradual decrease in the ocular blood flow in the ONH in conjunction with the progression of retinal vascular morphology changes [

34,

35].

The ocular blood flow in MetS is also expected to decrease not only the choroidal blood flow but also the ONH blood flow if functional as well as morphological changes progress in the retinal vessels. In any case, our present findings demonstrated a reduced choroidal blood flow, even during conditions that were considered to be at a relatively early stage of MetS. These results contribute to the elucidation of the pathology of progressing systemic and ocular diseases related to MetS from the viewpoint of ocular microcirculation.

There are several major study limitations to consider. Only males were examined, and our findings should not be generalized to females. The study data were extracted from a large database in order to enable a matched pair analysis, and this could have led to some selection bias. Although fundus photographs were taken for all subjects, optical coherence tomography was not performed for all of the subjects, it is thus possible that retinal and choroidal diseases cannot be completely ruled out. Finally, because the information on ocular and systemic diseases was obtained primarily from medical interviews of the subjects, there is a chance that other comorbidities or treatments for diseases such as hypertension and diabetes were overlooked. Due to the nature of the subjects' physical examinations, it is possible that the restrictions on fasting, alcohol consumption, and smoking prior to the examinations may not have been strictly adhered to. Further careful validation studies are necessary to overcome these limitations.

5. Conclusions

Our study of males clarified that at the early stage of MetS, the subjects with MetS had lower values of the rising rate (RR, which reflects the left ventricular function), and MBR in the choroid area is decreasing in parallel with the accumulation of MetS components. The MetS component with the strongest influence on the MBR-Choroid was the HbA1c value, which is a blood sugar-related factor.

Author Contributions

T.M., and T.S., wrote the main manuscript text, Table and prepared figures 1,2. T.K., and S.T., verified the analytical methods. Y.H., supervised the findings of this work. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Funding

No funding was received for this research.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Toho University Omori Hospital (approval no. M23044) and conducted according to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available due to data privacy concerns but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Abbreviations

| MetS |

Metabolic syndrome |

| LSFG |

Laser speckle flowgraphy |

| MBR |

mean blur rate |

| BOS |

blowout score |

| BOT |

blowout time |

| RR |

rising rate |

| ONH |

optic nerve head |

| BMI |

body mass index |

| SBP |

systolic blood pressure |

| DBP |

diastolic blood pressure |

| bpm |

beat per minute |

| D |

diopter |

| IOP |

intraocular pressure |

| FBS |

fasting blood sugar |

| TG |

triglycerides |

| HDL-C |

high-density lipoprotein cholesterol |

| LDL-C |

low-density lipoprotein cholesterol |

| HbA1c |

glycated hemoglobin A1c |

References

- Lakka, H.; Laaksonen, DE.; Lakka, TA.; Niskanen, LK.; Kumpusalo, E.; Tuomilehto, J.; Salonen, JT. The metabolic syndrome and total and cardiovascular disease mortality in middle-aged men. JAMA. 2002, 288, 2709–2716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tune, JD.; Goodwill, AG.; Sassoon, DJ.; Mather, KJ. Cardiovascular consequences of metabolic syndrome. Transl Res. 2017, 183, 57–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, SM.; Eleftheriadou, A.; Alam, U.; Cuthbertson, DJ.; Wilding, JPH. Cardiac autonomic neuropathy in obesity, the metabolic syndrome and prediabetes: a narrative review. Diabetes Ther. 2019, 10, 1995-2021.

- Lim, DH.; Shin, KY.; Han, K.; Kang, SW.; Ham, DI.; Kim, SJ.; Park, YG.; Chung, TY. Differential effect of the metabolic syndrome on the incidence of retinal vein occlusion in the Korean population: A nationwide cohort study. Transl Vis Sci Technol. 2020, 9, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, LA.; Canani, LH.; Lisboa, HR.; Tres, GS.; Gross, JL. Aggregation of features of the metabolic syndrome is associated with increased prevalence of chronic complications in Type 2 diabetes. Diabet Med. 2004, 21, 252–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Isono, H.; Kishi, S.; Kimura, Y.; Hagiwara, N.; Konishi, N.; Fujii, H. Observation of choroidal circulation using index of erythrocytic velocity. Arch Ophthalmol. 2003, 121, 225–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamaki, Y.; Araie, M.; Kawamoto, E.; Eguchi, S.; Fujii, H. Non-contact, two-dimensional measurement of tissue circulation in choroid and optic nerve head using laser speckle phenomenon. Exp Eye Res. 1995, 60, 373–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aizawa, N.; Yokoyama, Y,; Chiba, N.; Omodaka, K.; Yasuda, M.; Otomo, T.; Nakamura, M.; Fuse, N.; Nakazawa, T. Reproducibility of retinal circulation measurements obtained using laser speckle flowgraphy-NAVI in patients with glaucoma. Clin Ophthalmol. 2011, 5, 1171-1176.

- Kobayashi, T.; Shiba, T.; Nishiwaki, Y.; Kinoshita, A.; Matsumoto, T.; Hori, Y. Influence of age and gender on the pulse waveform in optic nerve head circulation in healthy men and women. Sci Rep. 2019, 9, 17895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, T.; Shiba, T.; Kinoshita, A.; Matsumoto, T.; Hori, Y. The influences of gender and aging on optic nerve head microcirculation in healthy adults. Sci Rep. 2019, 9, 15636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aizawa, N., Kunikata, H.; Nitta, F.; Shiga, Y.; Omodaka, K.; Tsuda, S.; Nakazawa, T. Age- and sex-dependency of laser speckle flowgraphy measurements of optic nerve vessel microcirculation. PLoS One. 2016, 11, e0148812.

- Yanagida, K.; Iwase, T.; Yamamoto, K.; Ra, E.; Kaneko, H.; Murotani, K.; Matsui, S.; Terasaki, H. Sex-related differences in ocular blood flow of healthy subjects using laser speckle flowgraphy. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2015, 56, 4880–4890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muramatsu, R.; Shiba, T.; Takahashi, M.; Hori, Y.; Maeno, T. Pulse waveform analysis of optic nerve head circulation for predicting carotid atherosclerotic changes. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2015, 253, 2285–2291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiba, T.; Takahashi, M.; Matsumoto, T.; Hori, Y. Pulse waveform analysis in ocular microcirculation by laser speckle flowgraphy in patients with left ventricular systolic and diastolic dysfunction. J Vasc Res. 2018, 55, 329–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shiba, T.; Takahashi, M.; Hori, Y.; Maeno, T. Pulse-wave analysis of optic nerve head circulation is significantly correlated with brachial–ankle pulse-wave velocity, carotid intima-media thickness, and age. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2012, 250, 1275–1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shiba, T.; Takahashi, M.; Hashimoto, R.; Matsumoto, T.; Hori, Y. Pulse waveform analysis in the optic nerve head circulation reflects systemic vascular resistance obtained via a Swan-Ganz catheter. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2016, 254, 1195–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takahashi, H.; Sugiyama, T.; Tokushige, H.; Maeno, T.; Nakazawa, T.; Ikeda, T., Araie, M. Comparison of CCD-equipped laser speckle flowgraphy with hydrogen gas clearance method in the measurement of optic nerve head microcirculation in rabbits. Exp Eye Res. 2013, 108, 10-15.

- Luft, N.; Wozniak, PA.; Aschinger, GC.; Fondi, K.; Bata, AM.; Werkmeister, RM.; Schmidl, D.; Witkowska, KJ.; Bolz, M.; Garhöfer, G.; Schmetterer, L. Ocular blood flow measurements in healthy white subjects using laser speckle flowgraphy. PLoS One. 2016, 11, e0168190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luft, N.; Wozniak, PA.; Aschinger, GC.; Fondi, K.; Bata, AM.; Werkmeister, RM.; Schmidl, D.; Witkowska, KJ.; Bolz, M.; Garhöfer, G.; Schmetterer, L. Measurements of retinal perfusion using laser speckle flowgraphy and Doppler optical coherence tomography. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2016, 57, 5417–5425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiba, T.; Takahashi, M.; Matsumoto, T.; Hori, Y. Relationship between metabolic syndrome and ocular microcirculation shown by laser speckle flowgraphy in a hospital setting devoted to sleep apnea syndrome diagnostics. J Diabetes Res. 2017, 2017, 3141678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuda, S.; Kunikata, H.; Shimura, M.; Aizawa, N.; Omodaka, K.; Shiga, Y.; Yasuda, M.; Yokoyama, Y.; Nakazawa, T. Pulse-waveform analysis of normal population using laser speckle flowgraphy. Curr Eye Res. 2014, 39, 1207–1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enomoto, N.; Anraku, A.; Tomita, G.; Iwase, A.; Sato, T.; Shoji, N.; Shiba, T.; Nakazawa, T.; Sugiyama, K.; Nitta, K.; Araie, M. Characterization of laser speckle flowgraphy pulse waveform parameters for the evaluation of the optic nerve head and retinal circulation. Sci Rep, 2021, 11, 6847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Examination Committee for Criteria of Metabolic Syndrome. Definition and Criteria of metabolic syndrome. Nihon Naika Gakkai Zasshi. 2005, 94, 794-809 (in Japanese).

- Kanda, Y. Investigation of the freely available easy-to-use software 'EZR' for medical statistics. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2013, 48, :452-458.

- Shigetoh, Y.; Adachi, H.; Yamagishi, S.; Enomoto, M.; Fukami, A.; Otsuka, M.; Kumagae, S.; Furuki, K.; Nanjo, Y.; Imaizumi, T. Higher heart rate may predispose to obesity and diabetes mellitus: 20-year prospective study in a general population. Am J Hypertens. 2009, 22, 151–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okamura, T.; Hayakawa, T.; Kadowaki, T.; Kita, Y.; Okayama, A.; Elliott, P.; Ueshima, H.; NIPPONDATA80 Research Group. Resting heart rate and cause-specific death in a 16.5-year cohort study of the Japanese general population. Am Heart J. 2004, 147, 1024-1032.

- Gillman, MW.; Kannel, WB.; Belamger, A.; D'Agostino, RB. Influence of heart rate mortality among persons with hypertension: the Framingham Study. Am Heart J. 1993, 125, 1148–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, SW.; Lee, S.; Park, C.; Kim, DJ. Elevated intraocular pressure is associated with insulin resistance and metabolic syndrome. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2005, 21, 434–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Lin, H.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, D.; Zhang, Y.; Meng, W.; Zhu, Z.; Tang, F.; Xue, F.; Liu, Y. Association between erythrocyte parameters and metabolic syndrome in urban Han Chinese: A longitudinal cohort study. BMC Public Health. 2013, 13, 989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miura, Y., Fukumoto, Y.; Shiba, N.; Miura, T.; Shimada, K.; Iwama, Y.; Takagi, A.; Matsusaka, H.; Tsutsumi, T.; Yamada, A.; Kinugawa, S.; Asakura, M.; Okamatsu, S.; Tsutsui, H.; Daida, H.; Matsuzaki, M.; Tomoike, H.; Shimokawa, H. Prevalence and clinical implication of metabolic syndrome in chronic heart failure. Circ J. 2010, 74, 2612-2621.

- Sharma, A.; Razaghizad, A.; Ferreira, JP.; Machu, JL.; Bozec, E.; Girerd, N.; Rossignol, P.; Zannad, F. Metabolic syndrome and the risk of preclinical heart failure: Insights after 17 years of follow-up from the STANISLAS Cohort. Cardiology. 2022, 147, 281–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shiba, C.; Shiba, T.; Takahashi, M.; Matsumoto, T.; Hori, Y. Relationship between glycosylated hemoglobin A1c and ocular circulation by laser speckle flowgraphy in patients with/without diabetes mellitus. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2016, 254, 1801–1809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagaoka, T.; Sato, E.; Takahashi, A.; Yokota, H.; Sogawa, K.; Yoshida, A. Impaired retinal circulation in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: Retinal laser doppler velocimetry study. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2010, 51, 6729–6734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ueno, Y.; Iwase, T.; Goto, K.; Tomita, R.; Ra, E.; Yamamoto, K.; Terasaki, H. Association of changes of retinal vessels diameter with ocular blood flow in eyes with diabetic retinopathy. Sci Rep. 2021, 11, 4653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iwase, T.; Ueno, Y.; Tomita, R.; Terasaki, H. Relationship between retinal microcirculation and renal function in patients with diabetes and chronic kidney disease by laser speckle flowgraphy. Life (Basel). 2023, 13, 424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).