1. Introduction

Tumors exhibit high cellular and molecular complexity, evidenced by the profound divergences and convergences present in their pathways and mechanisms associated with their malignancy [

1].

Divergences can be exemplified by the contrasting influence of energy metabolism on the tumor surface versus its necrotic core [

2], the heterogeneity of the tumor microenvironment [

3], and the intricate intracellular signaling network [

4], which together poses significant challenges for oncology in terms of diagnosis, prognosis, and therapy [

5]. Convergences, on the other hand, are primarily associated with mutations in key genes [

6], interrelationships between pathways governing proliferation, migration and cellular invasion [

7,

8,

9], in addition to pivotal molecules involved in tumor progression processes, which are similarly present across dozens of tumor types. These convergences greatly contribute to the search for more comprehensive therapies.

In recent years, there has been a substantial increase in molecules displaying dual actions, depending on the organ, tissue or tumor type, most of which are non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs) [

10]. Among the main classes of ncRNAs with broad roles in tumors are long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) [

11], which perform numerous functions in the nuclear and cytoplasmic cellular environments [

11,

12].

LncRNAs are large molecules, typically ranging from 200 to 2000 nucleotides in length, that bear a high resemblance to mRNAs, often featuring 5’ capping and a 3’ poly-(A) tail [

13].

Their complex spatial structure allows for multiple regions of interaction with other classes of molecules, such as miRNAs, siRNAs, mRNAs, tRNAs, rRNAs, proteins, and enzymes [

14], facilitating modifications in transcriptional and translational processes. These interactions can inhibit or induce pathways related to tumorigenesis and tumor malignancy.

At least four types of lncRNAs have been identified based on their genomic location: intergenic (e.g., XIST, MEG3, LINC-RoR) [

15,

16,

17], antisense (e.g., ZEB1-AS1, FOXP4-AS1, antisense variant of HOTAIR) [

18,

19,

20], sense (e.g., HOTAIR, UCA1, NEAT) [

21,

22,

23], and intronic (e.g., Braveheart, Charme) [

24,

25]. Additionally, lncRNAs are classified by their general function as either cis-acting (when influencing chromatin states) or trans-acting (when associated with cytoplasmic functions) [

26].

Their functions vary widely depending on their cellular localization and interactions. Some lncRNAs are involved in chromatin remodeling, influencing the degree of condensation and subsequent transcriptional expression of genomic regions through interactions with epigenetic elements [

27,

28]. Others act as sponges for miRNAs, sequestering them to prevent mRNA silencing and consequent inhibition, thereby deregulating or altering molecular pathways [

29]. Many lncRNAs perform functions ranging from serving as molecular scaffolds — forming protein and/or nucleic complexes involved in signaling pathways — to directly regulating gene expression by interfering with the RNA polymerase activity, competing with transcription factors or acting as guide RNAs for effector molecules in cellular transcription and translation processes [

30,

31].

The long intergenic non-coding RNA LINC01133 (or LINC01133, only) has attracted significant attention in recent years due to its dual role in various tumor types. Functioning as a miRNA sponge and a scaffold for DNA/protein complexes [

32,

33,

34], it exhibits high cellular heterogeneity and distribution, which has expanded its study and potential use as a diagnostic and prognostic biomarker. However, its overall structure, molecular mechanisms and direct and indirect roles in tumorigenesis and tumor progression processes remain largely unknown, including its broader epigenetic and cellular influence.

This article presents a mixed exploratory study based on in silico analysis of public biobanks and a narrative literature review on LINC01133, detailing its structure, molecular interactions and associations with mechanisms of tumorigenesis and tumor progression. It also discusses perspectives for basic and clinical research and its potential as an oncological biomarker.

2. Methods

Sequence Acquisition

The gene and transcriptional sequences of LINC01133 were obtained from the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI,

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov) [

35] by consulting the Gene and Nucleotide portals for the LINC01133 gene, retrieving its complete genomic sequence and annotated splicing variants. The data included 5’/3’ UTR regulatory regions, canonical GT-AG splicing sites, and associated metadata (transcript length, number of exons, initiation codon position), with priority given to experimentally validated REVIEWED records. After validation, the sequences were processed for comparative primary structure analysis and subsequent use in bioinformatic analyses.

Alignment and Structural Analysis

Molecular structure analyses were performed using the ViennaRNA package [

36], with minimum free energy (MFE) and spatial structure predictions made using the RNAfold Server (

http://rna.tbi.univie.ac.at/). To quantify the reliability of the predicted structures, base pairing probabilities were calculated using a thermodynamic partition function, considering significant values > 0.7 (range: 0-1), which indicate robust conformational stability. In addition, the centroid structure that maximizes the expected pairing accuracy was generated, with statistical evaluation based on the probability distribution of the ensemble of secondary structures. Splicing variant alignments were conducted with the T-Coffee suite (

https://tcoffee.crg.eu/apps/tcoffee/index.html) [

37], which employs probabilistic consistency algorithms for global optimization. Each aligned residue received a CORE index (0-9), where scores ≥ 5 indicate statistically reliable alignments (p < 0.05 by sequence randomization). Consensus sequences were visualized and acquired in Jalview (v2.11.4.1) [

38], with conservation scores calculated via normalized Shannon entropy (H(x) = -Σp(x)log₂p(x)), considering values H < 0.2 as highly conserved. Consensus was established with a threshold of 70% identity per position, validated by bootstrap (1,000 iterations) for significance estimation

Interspecies Conservation Analysis

Inter-species conservation analyses were conducted using the Ensembl platform’s genomic comparison algorithm (

https://www.ensembl.org/) [

39], with metadata from GENCODE (

https://www.gencodegenes.org/) [

40], covering 91 vertebrate species. Refinement was performed using LncBook 2.0 (

https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/lncbook/) [

41] for 40 eutherian mammal species, based on UCSC genome alignments between humans and vertebrates. This process aimed to identify coding and non-coding homologous genes and determine the evolutionary age of human lncRNA genes. For gene representation, the best-aligned transcript was selected by comparing the isoforms, considering the one with the highest number of paired bases in the comparative analysis. The total alignment length was calculated as the sum of all aligned segments of the selected transcript, while sequence identity was determined by the weighted average (by length and identity) of all alignments. In the evaluation of sequence conservation, alignments with a minimum length of 50 nucleotides and coverage greater than 20% of the lncRNA transcript were considered homologous, requiring that the alignment performance (length and identity) exceed the Q50 threshold of introns - a parameter that represents the intermediate level of conservation observed in alignments of intronic regions. Illustratively, in the human-mouse comparison, transcripts such as TUG1 and MALAT1 were found to be exceptionally conserved, exceeding the Q99.5 threshold for introns. This approach allowed the identification of 139,306 homologous genes associated with 22,347 human lncRNA genes. The evolutionary age of lncRNAs was defined as the oldest phylogenetic period with homologous sequence occurrence, covering 17 hierarchical temporal nodes from the most recent to the most ancestral: ‘Homo’ (human-specific), ‘Hominini’, ‘Homininae’, ‘Hominidae’, ‘Hominoidea’, ‘Catarrhini’, ‘Simiiformes’, ‘Haplorrhini’, ‘Primates’, ‘Euarchontoglires’, ‘Boreoeutheria’, ‘Eutheria’, ‘Theria’, ‘Mammalia’, ‘Amniota’, ‘Tetrapoda’, and ‘Euteleostomi’, corresponding to key clades in the phylogenetic tree from zebrafish to humans.

Interactions Between LINC01133 and Tumorigenesis and Tumor Progression Pathways

Correlations between genes linked to tumorigenesis and tumor progression processes were analyzed using BioConductor packages (within the R Project for Statistical Computing Software 4.4.1 environment) [

36] and the online suite cBioPortal for Cancer Genomics (Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, USA) [

37]. Analyses were based on 11 Pan-Cancer studies (Cancer Therapy and Clonal Hematopoiesis (MSK, Nat Genet 2020); China Pan-cancer (OrigiMed, Nature 2022); MSK MetTropism (MSK, Cell 2021); MSK-CHORD (MSK, Nature 2024); MSK-IMPACT Clinical Sequencing Cohort (MSK, Nat Med 2017); MSS Mixed Solid Tumors (Broad/Dana-Farber, Nat Genet 2018); Metastatic Solid Cancers (UMich, Nature 2017); Pan-cancer analysis of whole genomes (ICGC/TCGA, Nature 2020); SUMMIT - Neratinib Basket Study (Multi-Institute, Nature 2018); TMB and Immunotherapy (MSK, Nat Genet 2019); Tumors with TRK fusions (MSK, Clin Cancer Res 2020) with an initial sample size (n) of 101,679 patient samples.

Methylation Profile in Tumors

The methylation levels of the LINC01133 gene in different tumor types were de-termined using the LncBook 2.0 platform (

https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/) [

41], provided by the China National Center for Bioinformation, Chinese Academy of Sciences. To characterize the DNA methylation profiles of lncRNAs in human diseases, LncBook 2.0 integrates 16 public bisulfite-seq datasets from TCGA (The Cancer Genome Atlas) and GEO (Gene Expression Omnibus), covering 14 types of cancer. The sets include data from Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia (GSE116229, 38 samples), Acute Myeloid Leukemia (GSE135869, 15 samples), Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia (GSE113336, 18 samples), Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma (GSE149608, 19 samples), Medullo-blastoma (GSE142241, 12 samples), Liver Cancer (GSE79799, 6 samples), in addition to eight TCGA sets: Bladder Urothelial Carcinoma (TCGA-BLCA, 7 samples), Invasive Breast Carcinoma (TCGA-BRCA, 6 samples), Colorectal Adenocarcinoma (TCGA-COAD, 3 samples), Lung Adenocarcinoma (TCGA-LUAD, 6 samples), Lung Squamous Cell Carcinoma (TCGA-LUSC, 5 samples), Rectal Adenocarcinoma (TCGA-READ, 3 samples), Gastric Adenocarcinoma (TCGA-STAD, 5 samples), and Uterine Endometrioid Carcinoma (TCGA-UCEC, 6 samples).

In identifying differentially methylated lncRNAs (characteristic lncRNA genes), promoter regions were defined as segments of -1500 bp relative to the transcription start site, calculating the average methylation level of all CpGs in the promoter or body regions. Considering the small sample size in some sets, specific criteria were ap-plied: for ALL (GSE116229), AML (GSE135869), CLL (GSE113336), and ESCC (GSE149608), a maximum sample value > 0. 2, median variation ≥ 2 or ≤ 1/2, and ad-justed p-value ≤ 0.05 (Wilcoxon test) was adopted; for MB (GSE142241) and RTT (GSE119980), a maximum value > 0. 2 and p-value ≤ 0.02 (Wilcoxon); for the TCGA sets (BLCA, BRCA, COAD, LUAD, LUSC, READ, STAD, UCEC), a consistent in-crease/decrease in all case versus control samples was required, maximum value > 0. 2 and control methylation level twice higher/lower than the maximum/minimum value of cases; for liver cancer (GSE79799), the minimum methylation level of cases/controls should exceed the maximum of controls/cases, with maximum value > 0.2 and median variation ≥ 4 or ≤ 1/4. Using these strict criteria, a total of 19,543 characteristic lncRNA genes with differential methylation profiles (hyper- or hypomethylated in the promot-er or body region) were identified.

Narrative Literature Review

The narrative literature review was conducted by searching major scientific indexers (PubMed,

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/, Google Scholar,

https://scholar.google.com/, Web of Science,

https://www.webofscience.com/, and Scopus,

https://www.scopus.com/) for original articles, reviews, and systematic reviews published between 2015 and 2024. A total of 49 articles were selected, including 41 original research articles specifically on LINC01133 and tumors, seven articles on tumors and associated molecules (including LINC01133), and one review article specifically on LINC01133.

3. Results and Discussion

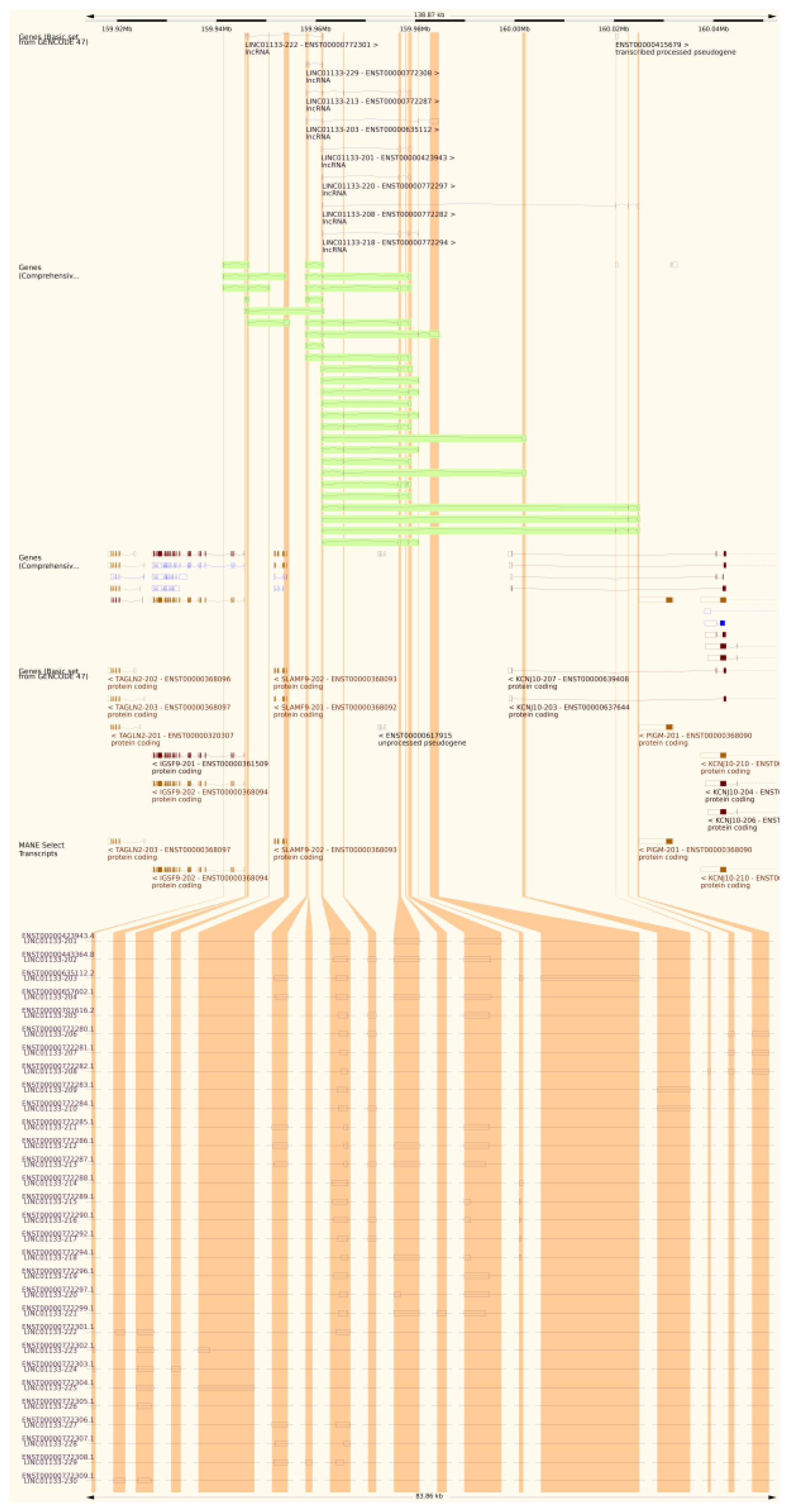

Genetic and Structural Analysis of LINC01133

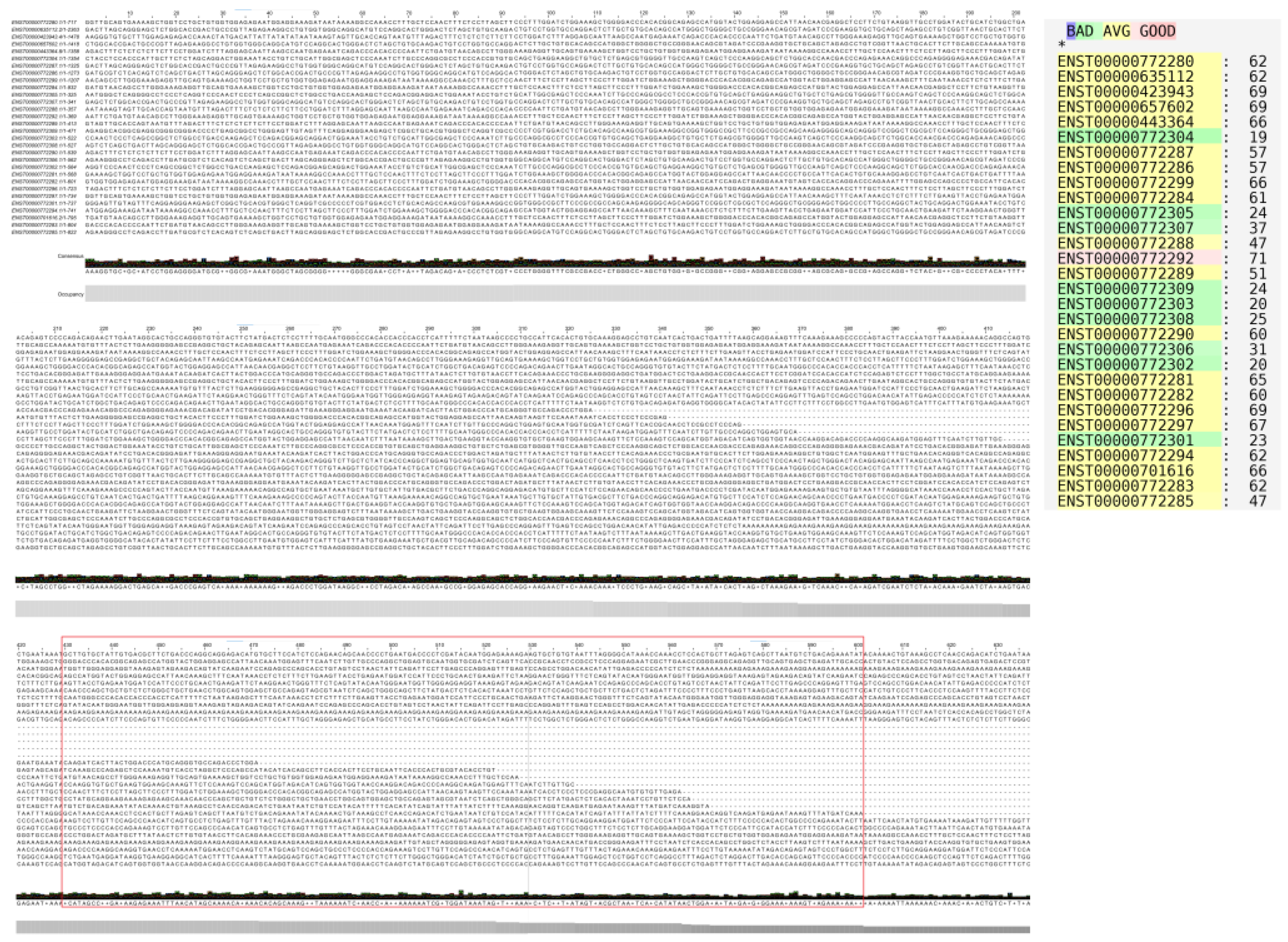

The LINC01133 gene (GRC37.p13/GRC38.p14, Primary Assembly, NCBI, ID: 100505633) has two variants (NC_000001.11, range 159961224–159979086: 17,863 nt; and NC_060925.1, range 159098290–159116157: 17,868 nt) and is located on the long arm of chromosome 1 (Chr1q.23.2), on the sense strand, in a downstream direction. There are 30 annotated transcripts (GRC37.p13/GENCODE47/MANE Select Transcripts), ranging between 300 and 2,400 bps, with three canonical exons (exon 1: 181 nt; exon 2: 468 nt; exon 3: 486 nt), as shown in

Table 1 and

Figure 1. Alignment of the transcripts, performed using T-Coffee and Jalview, indicates an average conservation of 51% among the cDNA sequences of the analyzed transcripts (

Figure 2). Based on this alignment, a consensus sequence was obtained for centroid and minimum free energy structure analysis, considering base pairing correlations, and regions with the highest probability of molecular interaction (

Figure 3).

The analyses revealed four regions of interest with internal loops (

Figure 3). Internal loops are regions with a high probability of molecular interaction due to the absence of base pairing with other regions of the RNA strand [

38], serving as interaction sites for scaffold formation or miRNA sequestration, for example [

39]. Three internal loops (1, 2, 3) observed in the predicted structure (

Figure 3) are formed by base pairs between positions 430–600, present in 24 of the 30 transcripts, while one internal loop (4) is formed by base pairs between positions 1125–1153, present in only 9 of the 30 transcripts (

Figure 2 and

Figure 3).

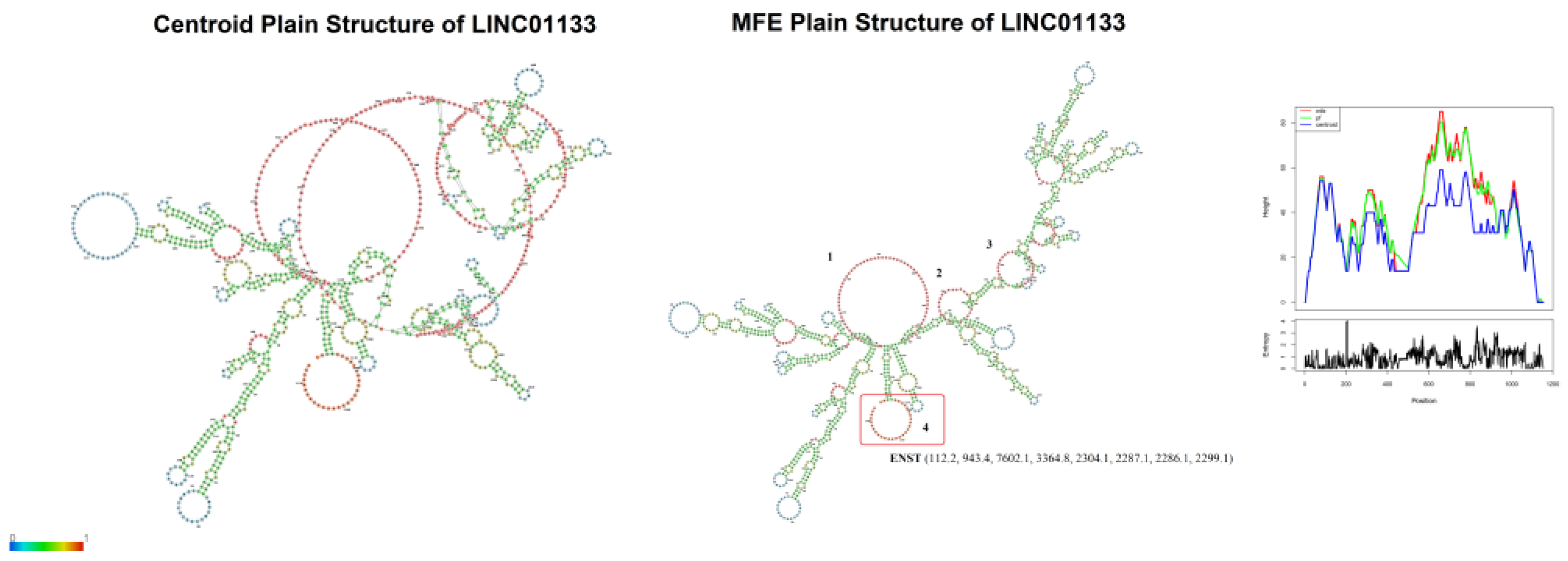

However, alignment analyses using treeplot neighbor joining (

Figure 4) demonstrate diffuse conservation among the transcripts containing internal loop 4 in their structure, since one of the transcripts (ENST00000772287.1) is positioned as an outlier in the interaction network. The relationship between transcripts ENST00000772287.1 (1925 bp) and ENST00000635112.2 (2363 bp) also validates the conjecture of two main indel events through which the LINC01133 gene underwent during human evolution.

The conservation of internal loops 1, 2, and 3 in 80% of the transcripts is likely to be correlated with vital functions of LINC01133 in cellular and molecular processes related to the control of cell proliferation, migration and invasion, as exemplified in its aberrant activity across various tumor types, and discussed in this article.

Inter-Species Conservation of LINC01133

The conservation of the LINC01133 gene was assessed using the consensus transcript sequence relative to genomic annotations from 91 vertebrate species obtained through the NCBI platform (

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/), with refinement for 40 species of particular interest. Conservation was analyzed comparatively, considering Q90 as a high conservation standard (≥ 90% gene similarity), Q75 as a medium conservation standard (≥ 75% gene similarity), and Q50 as a low conservation standard (≤ 50% gene similarity). Gray plots and the absence of a conservation pattern highlight the lack of gene conservation or absence of relevant data.

According to the analyses shown in

Figure 5, LINC01133 exhibits high conservation in hominid primates, such as

Homo sapiens,

Pan paniscus,

Pan troglodytes,

Gorilla gorilla, and

Pongo abelli, with a Q90 conservation index. In non-hominid primates, such as

Macaca fascicularis and

Macaca mulatta, the conservation is slightly lower. In rodents, the conservation levels are moderate, with a Q75 index. In more distant mammals, such as

Felis catus and

Bos taurus, the conservation was lower, reflecting the progressive decrease in similarity as phylogenetic distance increases. In birds, reptiles, and fish (such as, respectively,

Gallus gallus,

Thamnophis sirtalis,

Xenopus laevis, and

Danio rerio), LINC01133 was not detected, suggesting its absence or functional loss in these groups.

The high conservation of LINC01133 in hominid primates and

Equus caballus and

Loxodonta africana may suggest a strong correlation between the activity of LINC01133 in tumorigenic processes linked to the early dysregulation of genes involved in the cell cycle [

46]. Several species from the orders Ungulata and Afrotheria possess multiple copies of the TP53 gene, and studies have already supported the relationship between possessing multiple copies of TP53 and tumors resistance to drugs [

47,

48].

Associations Between LINC01133 and Tumors via RNA-Seq Data

Based on evidence linking the LINC01133 gene to tumorigenesis and tumor progression, bioinformatics analyses were conducted using RNA-Seq repositories from Pan-Cancer studies, aiming to identify cellular and molecular associations of the transcript with tumors.

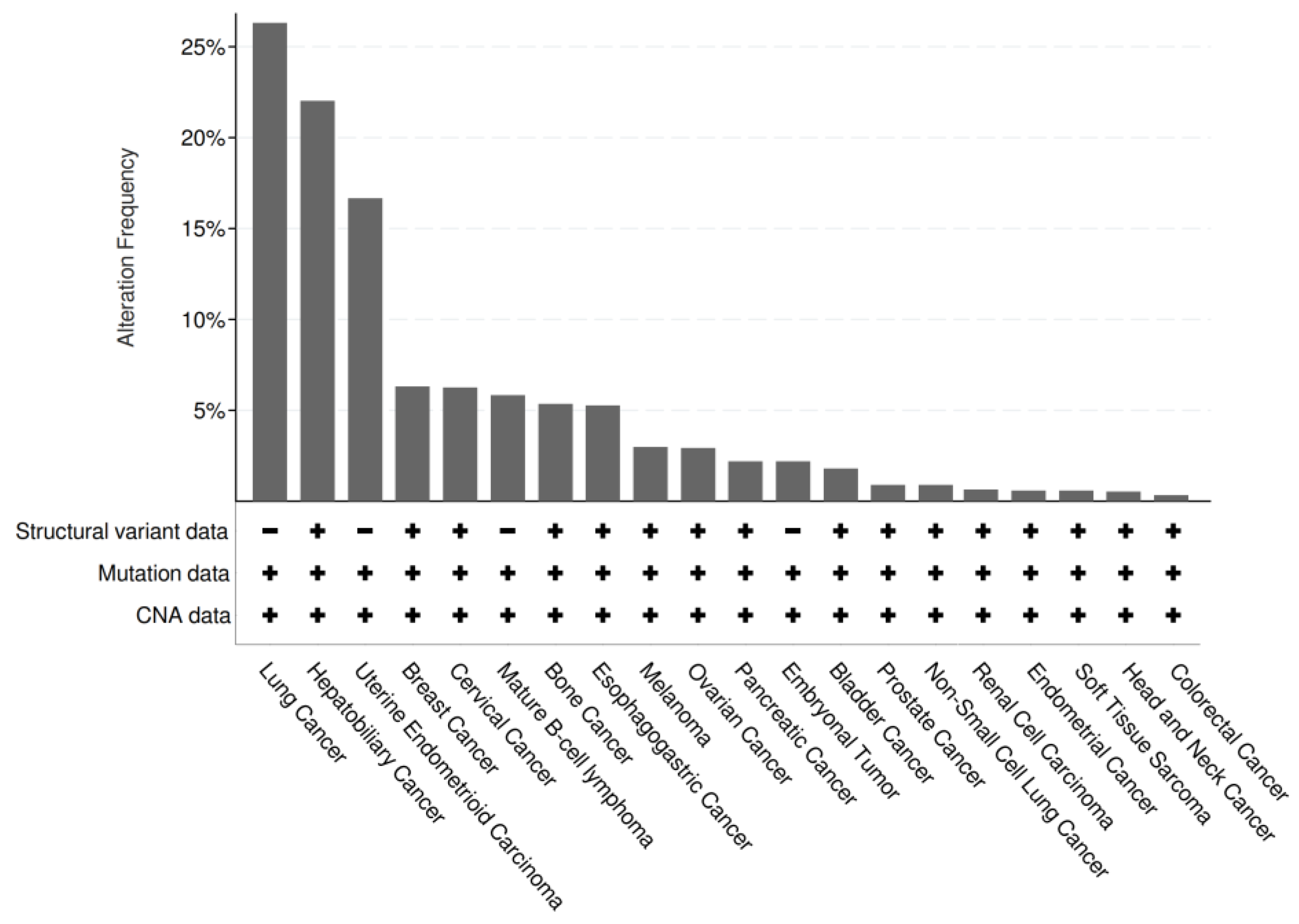

Of the 101,679 samples (n) analyzed, 9.66% (n1 = 9,819) showed significant alterations in LINC01133 expression, including structural variations (such as duplications, deletions, inversions, or translocations), base substitutions or indels, or changes in copy number. Among n1, 3.30% (n2 = 324) exhibited amplifications in LINC01133 expression.

While insufficient data precludes the establishment of precise hypotheses regarding the convergent function of LINC01133 in tumors, evidence suggests its strong association as a tumor suppressor.

Figure 6.

Genetic alterations of LINC01133 in different types of tumors. The identification of structural variations was carried out via breakpoint detection; the Ensembl database was used to determine the associated mutations, searching for synonymous and non-synonymous mutations for categorization; the gene copy number alteration (CNA) data was analyzed via GISTIC.

Figure 6.

Genetic alterations of LINC01133 in different types of tumors. The identification of structural variations was carried out via breakpoint detection; the Ensembl database was used to determine the associated mutations, searching for synonymous and non-synonymous mutations for categorization; the gene copy number alteration (CNA) data was analyzed via GISTIC.

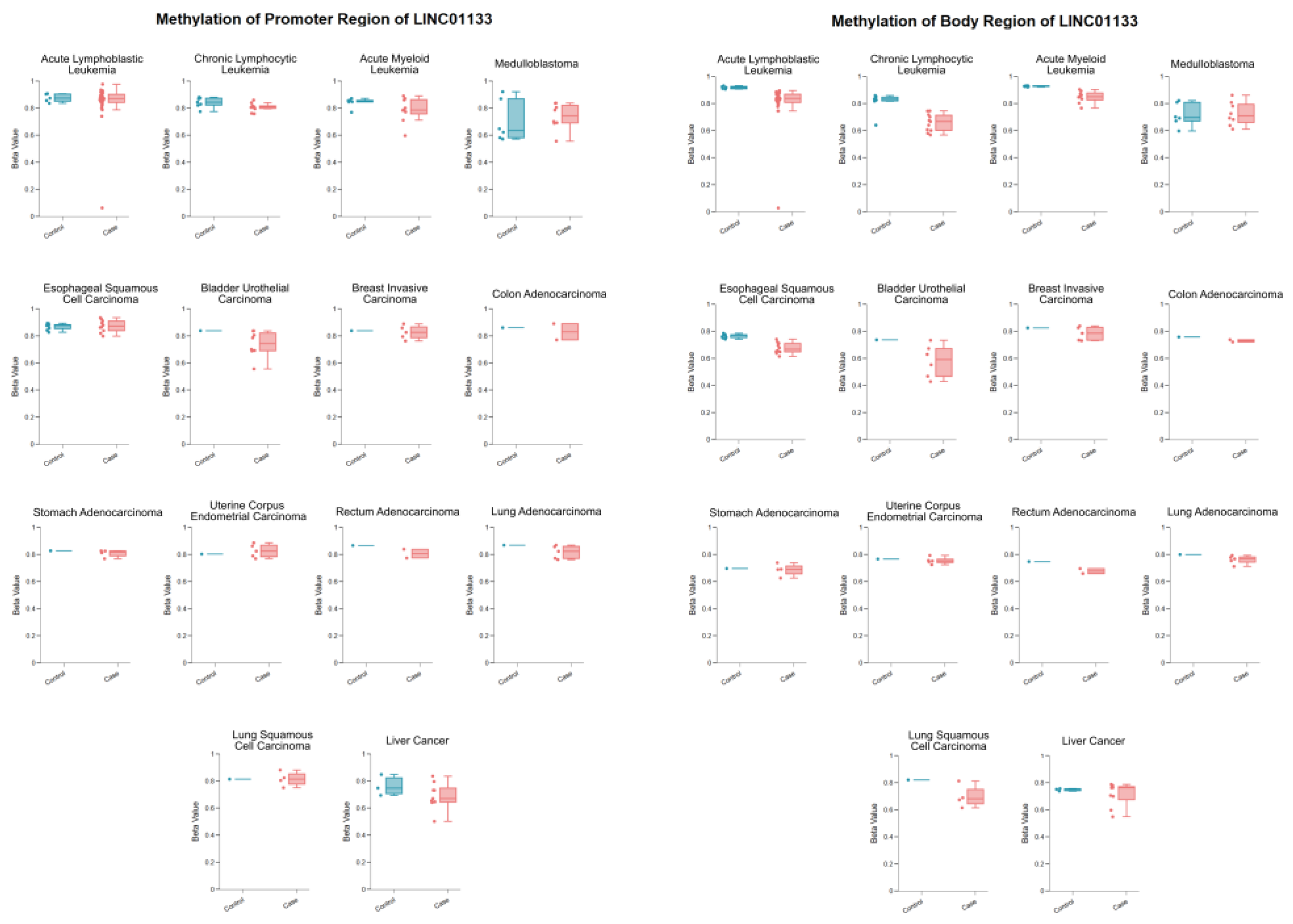

DNA Methylation Profile of the LINC01133 Gene in Different Tumor Types

Methylation profiles were obtained via LncRNAbook from bisulfite-seq datasets derived from The Cancer Genome Atlas Program (TCGA) and the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO), as shown in

Table 2.

The data presented in

Table 2 highlight the methylation levels in the promoter and gene body regions of LINC01133 in various tumor types and their respective controls. The analysis is based on methylation values (Beta-value), with emphasis on the potential role of these epigenetic alterations in the samples. DNA methylation in promoter regions is generally associated with gene expression repression [

49], while methylation in gene body regions is linked to different regulatory contexts, such as the maintenance of active transcription [

49,

50].

The promoter methylation of LINC01133 in acute leukemias (ALL and AML) shows a slight reduction in the samples compared to controls, suggesting a possible epigenetic deregulation that may favor the gene’s overexpression in tumor conditions. In CLL, the promoter methylation is also significantly reduced, suggesting that the activation of LINC01133 could be a common mechanism in hematologic neoplasms.

In solid tumors, similar patterns of hypomethylation of the promoter are observed in most tumor samples (such as in BLCA, READ, and Hepatic Tumor). This finding reinforces the potential oncogenic role of LINC01133, possibly contributing to tumor progression through increased expression.

Considering the methylation patterns in the gene body region, a clear and notable hypomethylation is observed in hematologic, bladder, and esophageal tumors. While intragenic methylation is generally associated with active transcription, its reduction may alter transcript processing, such as splicing or RNA stabilization, leading to changes in gene functionality and contributing to processes such as evasion of suppressive mechanisms or promotion of cell proliferation [

51].

Figure 7.

Differential methylation profiles of LINC01133 in tumor types based on the comparison of methylation levels (Beta values) in the promoter and body regions of LINC01133 between tumor samples and controls, highlighting hypomethylation and hypermethylation patterns in 14 tumor types, with data processed via LncBook 2. 0 from 16 bisulfite-seq sets (TCGA/GEO), with sample sizes ranging from 6 to 38 samples. Disease-specific statistical criteria applied as described in the methodology (e.g., median variation ≥ 2x, maximum value > 0.2, directional consistency in TCGA samples); (p-adj ≤ 0.05; Wilcoxon test).

Figure 7.

Differential methylation profiles of LINC01133 in tumor types based on the comparison of methylation levels (Beta values) in the promoter and body regions of LINC01133 between tumor samples and controls, highlighting hypomethylation and hypermethylation patterns in 14 tumor types, with data processed via LncBook 2. 0 from 16 bisulfite-seq sets (TCGA/GEO), with sample sizes ranging from 6 to 38 samples. Disease-specific statistical criteria applied as described in the methodology (e.g., median variation ≥ 2x, maximum value > 0.2, directional consistency in TCGA samples); (p-adj ≤ 0.05; Wilcoxon test).

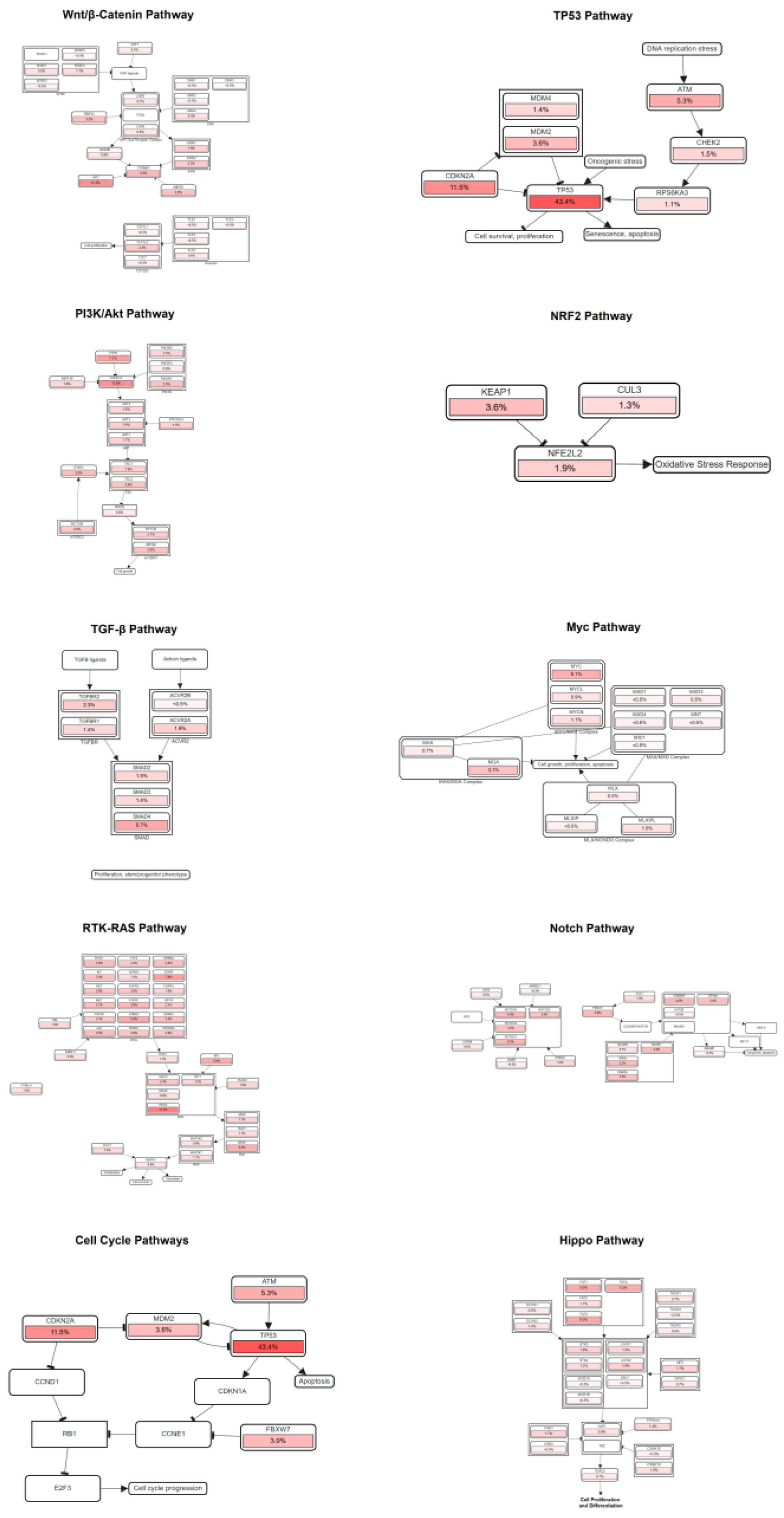

Relationships Between LINC01133 and Pathways Associated with Tumor Progression

Pathway and gene analyses related to LINC01133 were performed based on the positive correlation between mutually aberrant expressions of genes linked to the pathways and LINC01133, using the sample size obtained from the Pan-Cancer studies. The selected pathways are involved in processes directly and indirectly related to genomic or cell cycle destabilization that drives tumorigenic processes, as outlined in

Table 3 below:

The correlations between LINC01133 and the pathways analyzed can be related in the following manners:

(i) the APC gene, which encodes a protein of the same name, is part of a protein complex responsible for the degradation of β-catenin [

70]. Aberrant expression of APC, along with LINC01133 expression, suggests an influence of the lncRNA on tumor suppressor activity, inhibiting neoplastic cell proliferation;

(ii) the expression of mutated TP53 genes and inhibition of the expression of wild-type TP53 copies is one of the main factors leading to cell cycle deregulation and the onset and maintenance of tumors [

71]. The increased expression of CDKN2A, linked to inhibition of wild-type TP53, possibly promoted by LINC01133, may be associated with early tumorigenesis;

(iii) the increased expression of PIK3CA, along with the slight increase in PTEN expression, may be involved in a gene switch related to optimizing epithelial-mesenchymal transition processes;

(iv) the increased expression of KRAS and LINC01133 may be related to long-term tumor maintenance.

These potential correlations demonstrate the dual activity of LINC01133 in different types of tumors, with various actions that may either promote or inhibit tumor growth and processes of late malignancy, such as angiogenesis and proximal or distant metastasis.

Figure 8.

Positive correlations between aberrant expression of LINC01133 and key genes of pathways related to cell cycle destabilization and tumorigenesis. Analyses performed using Spearman’s correlation (ρ) and FDR-adjusted significance (q < 0.05).

Figure 8.

Positive correlations between aberrant expression of LINC01133 and key genes of pathways related to cell cycle destabilization and tumorigenesis. Analyses performed using Spearman’s correlation (ρ) and FDR-adjusted significance (q < 0.05).

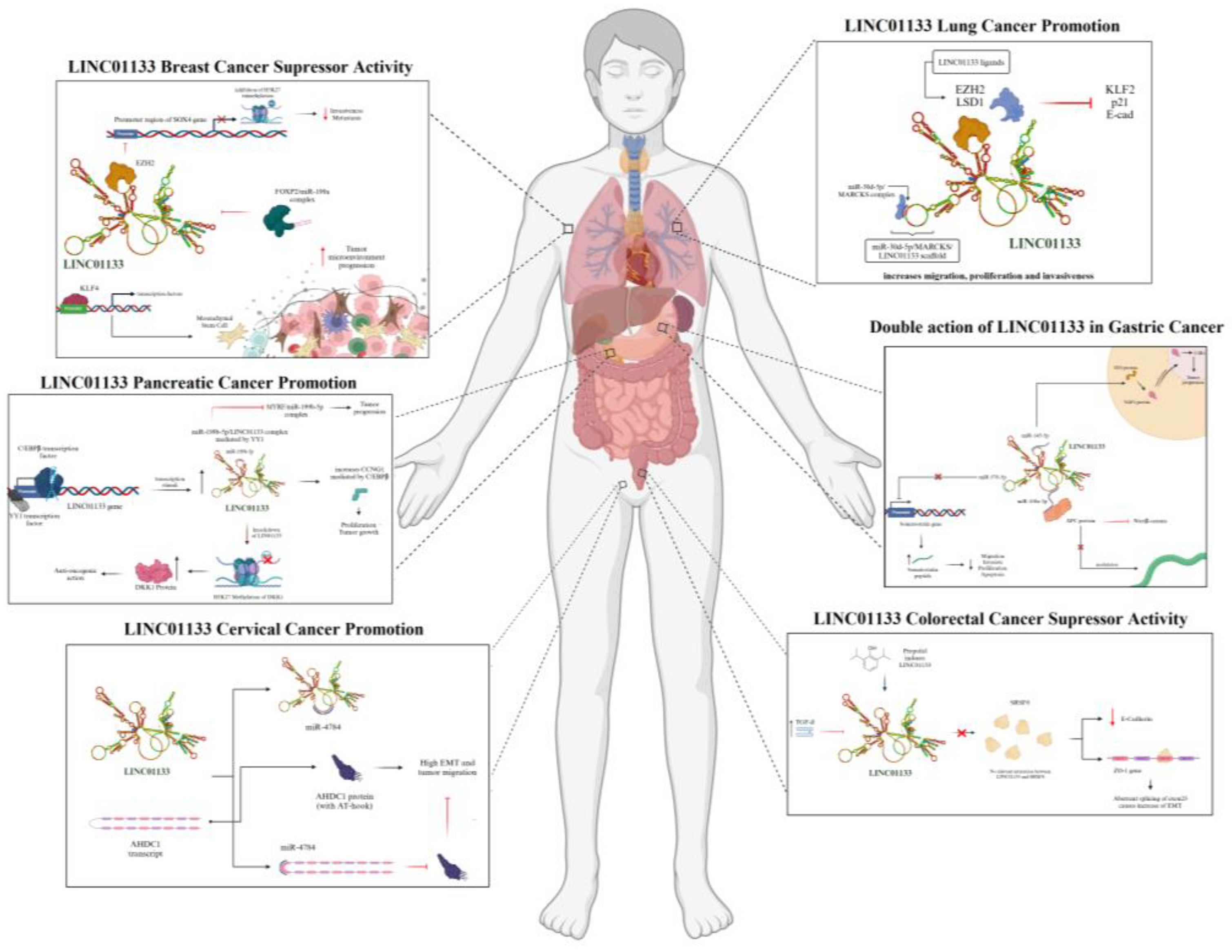

LINC01133 and Its Actions in Different Types of Tumors

The investigation of LINC01133 began systematically in 2015, when Zhang et al. [

72] identified its contribution to tumorigenesis in lung squamous cell carcinoma. Since this discovery, 41 scientific studies have been published exploring the role of LINC01133 in different types of neoplasms, as detailed in

Table 4, which shows the main hypotheses regarding its oncogenic and/or tumor-suppressing actions in 15 different types of tumors:

Lung Tumors

Lung tumors (LT) are among the leading neoplasms in terms of mortality, regardless of gender. Although advanced therapies exist, the prognosis remains extremely challenging, positioning them as one of the major obstacles in clinical oncology. The association between pulmonary neoplastic progression and lncRNAs was initially established in 2012, and since then, increasing research has demonstrated the strong influence of lncRNAs in the tumorigenic and metastatic processes. Recent evidence shows the contiguous action of LINC01133 in enhancing malignancy in different types of LT, with LINC01133 being classified among the top 20 most differentially expressed lncRNAs in a positive manner in LAD and LSCC, through bioinformatics analyses of omics databases, as well as in vitro assays showing that silencing LINC01133 in the H1703 LT cell line inhibited tumor migration and invasion [

72].

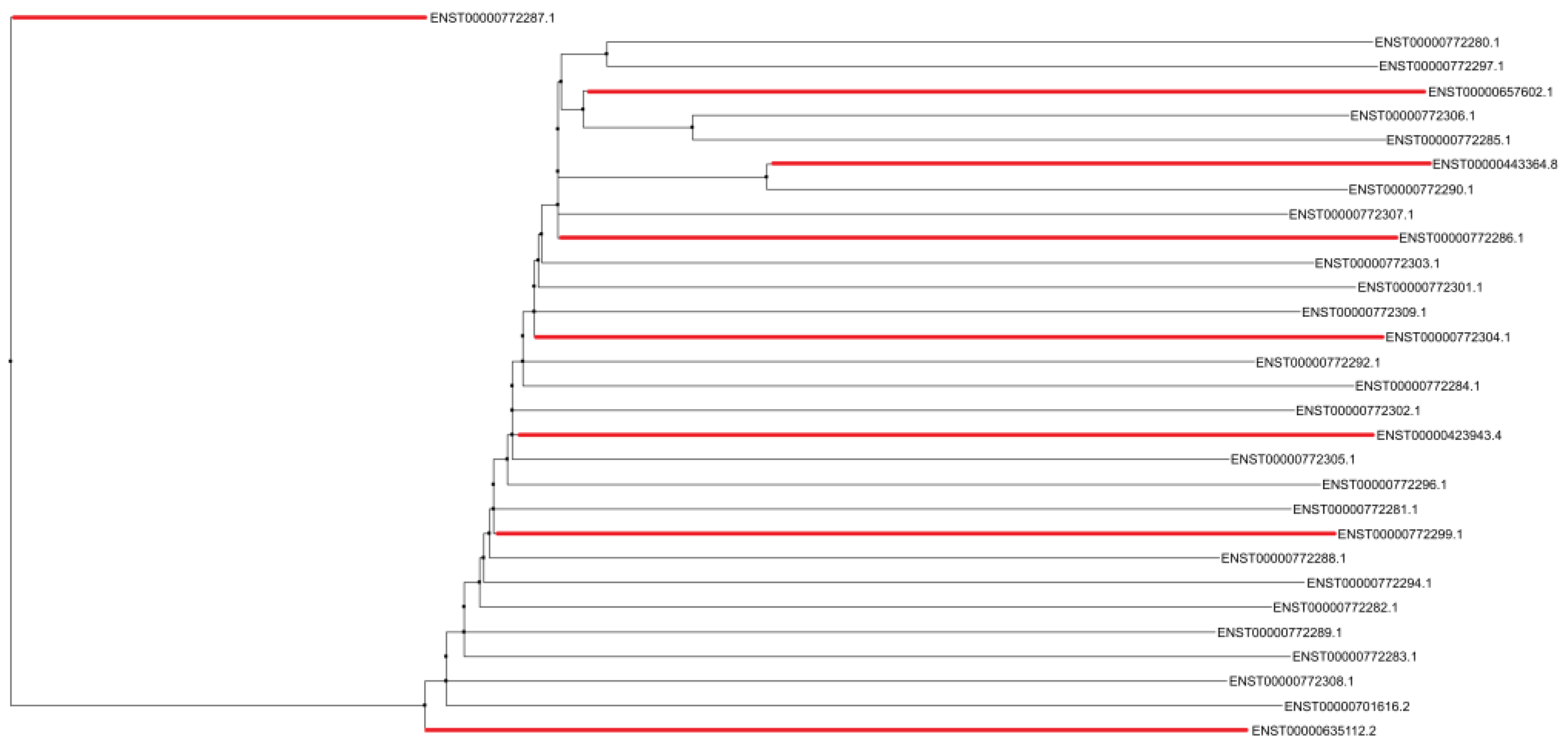

The association of LINC01133 in LT may strongly influence processes of EMT and cell migration. Through LINC01133 silencing in NSCLC cell lines, Zang et al. (2016) [

73] demonstrated a substantial reduction in the mechanisms of proliferation, migration, and tumor invasion. RIP assays, RNA pulldown, silencing, and qPCR showed that LINC01133 interacts with the EZH2 and LSD1 proteins to repress transcription of the KLF2, P21, and E-cadherin genes, which are associated with a significant reduction in cell adhesion and, consequently, enhanced EMT mechanisms.

LINC01133 may also be associated with the tumorigenic process in LSCC through the formation of a scaffold between miR-30d-5p and the MARCKS protein, a kinase that activates the NF-kB signaling pathway in tumors [

75]. Evidence shows that the scaffold formation inhibits the action of miR-30d-5p, which, consequently, fails to repress the PI3K/Akt pathway and increases the expression and activity of the kinase, also enhancing tumor migration, proliferation, and invasion, as shown in

Figure 9.

Colorectal Tumors

In CRC, LINC01133 appears to have a tumor-suppressive effect. In in vitro experiments, negative regulation of LINC01133 by TGF-β, an inherent tumor promoter, was observed. LINC01133 silencing assays in HT29 and HCT28 human cell lines showed minimal influence on proliferation mechanisms, but a dramatic reduction in E-cadherin expression, which, along with deregulation of other genes such as Vimentin and Fibronectin, was associated with an increase in migratory potential and EMT. The gene deregulation observed and the consequent increase in EMT processes may be directly associated with the interaction of LINC01133 with the alternative splicing factor SRSF6 [

77]. When LINC01133 is expressed, it inhibits the activation of mesenchymal markers such as Fibronectin, while maintaining the expression of epithelial markers such as E-cadherin. Manipulation of SRSF6, in turn, promotes EMT and metastasis independently of LINC01133, indicating that SRSF6 plays a central role in the induction of these processes, as shown in

Figure 9 [

77].

Another interesting finding, by Yao et al. (2023) [

79], links the anesthetic Propofol to LINC01133. In vitro and in vivo assays showed that Propofol induces transcription of the LINC01133 gene, thus inhibiting tumor progression by suppressing proliferation and invasion mechanisms through interaction with the miR-186-5p miRNA.

Breast Tumors

BRC, although classified into five well-defined subtypes (Luminal A, Luminal B, HER2+, HER2-enriched, and Basal-Like (Triple-Negative)), are extremely heterogeneous in terms of gene mutations and aberrant expression of molecules linked to tumor progression, with LINC01133 being a target of great interest, considering the dual actions it may exhibit in different subtypes and classes of each subtype.

The discovery of LINC01133 interaction with BRC dates back to 2017, when its aberrant expression was identified in MCF7, MDA-MB-231, and Hs578T human cell lines. Subsequent assays showed that the increased expression of LINC01133 is possibly regulated by mesenchymal cells from the tumor microenvironment, in addition to evidence showing the role of LINC01133 as a scaffold for the miR-199a/FOXP2 complex, directly influencing the differentiation of tumor stem cells [

82], as shown in

Figure 9.

The relationship between LINC01133 and the zinc-finger protein KLF4 was also evidenced. LINC01133 silencing assays showed a direct relationship with the reduction of KLF4 expression and the subsequent inhibition of the RAS/ERK signaling pathway, inhibiting the proliferation processes [

80].

The tumor-suppressive action of LINC01133 was also observed in vitro and in patient samples. From seven tumor cell lines and one non-tumor cell line, as well as samples from 74 breast cancer patients with no indicated subclassification, Song et al. (2019) [

81] showed that reduced expression of LINC01133 in different cell lines increases tumor progression through enhanced migration and invasion. Results from patient samples revealed a possible correlation between the decreased expression of LINC01133 and increased lymph node and distant metastasis in patients with low TNM staging. The increased malignancy due to non-significant expression of LINC01133 may be closely associated with its interaction with the EZH2 protein, and their combined action on the increased expression of SOX4 through interaction with the gene’s promoter region, positively influencing tumor progression mechanisms [

81].

Ovarian Tumors

Ovarian tumors (OVT), along with BRC and cervical tumors (CvT), are among the most common and lethal in women worldwide. While their therapy is well-established, the discovery of lncRNA interactions with their tumor progression mechanisms has provided new tools for clinicians in developing more effective therapies.

LINC01133 appears to have a dual role in OVT. Microarray experiments directly correlated LINC01133 and miR-205 as molecules of interest. Subsequent assays revealed that low expression of LINC01133 is associated with poorer prognosis in OVT.

Experiments performed in cells transfected with LINC01133 demonstrated a substantial decrease in proliferation, migration and invasion, accompanied by changes in the expression of key proteins linked to the cell cycle and cell migration, including Cyclin D1, Cyclin D3, CDK2, Vimentin, N-cadherin and E-cadherin. In vivo, mice inoculated with cells transfected with LINC01133 showed a significant reduction in tumor weight and volume, as well as a decrease in metastatic nodules, when compared to controls. Bioinformatic and in vitro assays also showed an association between LINC01133 and miR-205, with evidence of LINC01133 functioning as a sponge, primarily repressing colony formation, tumor invasion, and migration [

83].

On the other hand, the oncogenic action of LINC01133 in OVT may arise from the modulation of the miR-495-3p/TPD52 axis, as seen by Liu and Xi (2020) [

84]. Bioinformatic predictions showed binding sites between LINC01133 and miR-495-3p, as well as interaction between the miRNA and the protein TPD52, which is overexpressed in several tumors and associated with poor prognosis due to its role in uncontrolled proliferation. The modulation of TPD52 occurs via miR-495-3p, meaning that the capture of the miRNA by LINC01133 enhances the tumorigenic action of TPD52, leading to increased OVT malignancy.

Bladder Tumors

In bladder tumors (BLT), LINC01133 potentially plays a tumor-suppressive role. Molecular expression assays revealed its significant expression in non-tumor cell lines (SV-HUC-1), particularly in associated exosomes, while in BLT cell lines, its expression was predominantly reduced. Overexpression assays of LINC01133 in BLT cell lines showed its suppressive action, linked to a decrease in proliferation through interaction with the cell cycle, Wnt, and c-Myc pathways, results that were also observed in in vivo analyses [

85].

Hepatic Tumors

Evidences suggest that LINC01133 has oncogenic activity in HpT. Two studies analyzed the influence of LINC01133 on various pathways and molecules in human liver tumor cell lines, with the first results showing its increased expression compared to normal liver cell lines. Silencing assays were performed in He3B and HepG2 cell lines, also observing the inhibition of proliferation mechanisms, colony formation, and, in combination, induction of apoptotic mechanisms. Subsequent in vitro and in vivo assays also suggest a direct relationship between LINC01133 and hyperactivation of the PI3K/Akt pathway [

87].

Further assays also revealed an increase in the number of LINC01133 copies in genomic data from patients, which correlated with a worse prognosis for the patients. Overexpression assays were also performed in liver tumor cell lines, showing results of increased proliferation and oncogenic aggressiveness, with a direct relationship between the sponge activity of LINC01133 and miRNA miR-199a-5p, triggering an increase in the EMT process due to the exacerbated expression of Snail [

86].

Pancreatic Tumors

The association between LINC01133 and PC is the most well-established among all other tumors, with its tumorigenic and tumor progression action evidenced and corroborated by several studies over the last 10 years. The current state of knowledge between LINC01133 and PC indicates three main established pathways, namely: (i) increased tumor proliferation mediated by C/EBPB; (ii) tumor progression stimulated by DKK1; and (iii) tumor progression mediated by miR-199b-5p/YY1, as shown in

Figure 9.

In a study by Huang et al. (2018) [

88], the significant increase in LINC01133 expression in pancreatic tumor tissues was observed. In vitro experiments, through LINC01133 silencing, showed a substantial reduction in proliferation processes in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) cell lines. The C/EBPb transcription factor was identified as a positive regulator of LINC01133, binding to the promoter of this gene, and its elevated expression was also observed in PDAC tissues, correlating with worse patient prognosis. Mutation assays at the C/EBPb binding sites showed that interaction with the LINC01133 promoter is crucial for its activation. Gene expression analysis revealed that LINC01133 silencing reduced the expression of Cyclin G1 (CCNG1), which was positively correlated with LINC01133, based on TCGA data analysis [

88].

Weng et al. (2019) [

90] observed the oncogenic promotion capability of LINC01133 through gene expression analysis from microarray data, showing a positive differential expression of LINC01133 to be directly correlated with the exacerbated methylation of the DKK1 gene promoter and linked to increased proliferation through the deregulation of the Wnt pathway. The interaction between LINC01133 and the DKK1 promoter was verified by luciferase assays, revealing that LINC01133 binds to the DKK1 promoter, inducing H3K27 trimethylation and reducing DKK1 expression, while Wnt-5a, MMP-7, and β-catenin levels were increased. Silencing assays of LINC01133 further revealed a reduction in proliferation, migration, and invasion of pancreatic cancer cells.

Employing luciferase assays, Yang et al. (2022) [

93] showed that the YY1 protein positively regulates LINC01133 expression by binding to its promoter. Moreover, LINC01133 exhibited a sponge activity towards miR-199b-5p, promoting tumor progression mechanisms by inhibiting the miRNA. The tumor progression caused by miR-199b-5p inhibition is primarily related to its reduced binding to the MYRF protein. LINC01133’s binding to the miRNA indirectly elevates MYRF levels, contributing to increased proliferation and metastatic processes in PT.

Esophageal Tumors

Although data regarding the relationship between LINC01133 and esophageal tumors (EPT) are scarce, there is evidence suggesting its tumor-suppressive action in esophageal squamous cell carcinomas. Molecular qPCR assays conducted with tumor and normal tissue samples showed significantly lower LINC01133 expression in tumor cell lines. Furthermore, the expression of LINC01133 decreased independently of TNM stage and lifestyle, which indicated a higher risk of tumor mass growth, proximal metastasis and overall invasiveness [

98].

Oral Squamous Cell Carcinomas

Studies on the role of LINC01133 in oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) have shown its suppressive action, associating its significant expression with reduced metastasis and better prognosis. qRT-PCR assays revealed lower transcriptional expression of LINC01133 in tissues from OSCC patients compared to healthy individuals. RNA-Seq sequencing identified strong evidence of gene modulation linked to metastasis (such as GDF15) by LINC01133, along with reciprocal regulation of LINC01133 expression by GDF15, identified through GDF15 silencing assays in CAL27, HN4 and 293FT tumor cell lines [

99].

Gastric Tumors

Despite both promoter and suppressor tumor activities, LINC01133 predominantly acts as a tumor suppressor in gastric tumors (GT). Its constitutive expression in tumors obtained from patient tissue samples and in human cell lines is reduced, negatively correlating with tumorigenesis and tumor progression processes. LINC01133 silencing assays showed a substantial increase in cell proliferation, migration and EMT mechanisms, negatively modulating the expression of E-cadherin. The same study, conducted by Yang et al. (2018) [

100], also clarified that LINC01133 acts as an endogenous competitor for miR-106a-3p, indirectly regulating the expression of the APC gene, essential for inactivating the Wnt/β-catenin pathway.

Other miRNAs are also involved in the neoplastic modulation by LINC01133, such as miR-576-5p, which also has a direct interaction with the peptide hormone Somatostatin (SST). In tumor tissue samples, a negative correlation between LINC01133, miR-576-5p, and SST was observed, suggesting that LINC01133 inhibits miR-576-5p to increase SST expression [

102], as shown in

Figure 9.

Despite its predominantly suppressive activity, a study by Sun et al. (2022) provided evidence of the association between LINC01133 and tumor progression through modulation via interaction with miR-145-5p. Its role as an endogenous competitor for this miRNA increases the expression of the YES1 protein, a target of miR-145-5p. The YES1 protein promotes the nuclear translocation of YAP1, positively modulating the aberrant expression of cyclins and enabling excessive proliferation [

103], as shown in

Figure 9.

Nasopharyngeal Tumors

In NPC, LINC01133 likely plays a tumor-suppressive role. In vitro assays and patient tissue samples showed that LINC01133 directly interacts with the YBX1 protein, with both molecules modulating Snail. LINC01133 overexpression and silencing assays in the CNE-1 and SUNE-1 human tumor cell lines, respectively, showed that increasing LINC01133 expression negatively modulated Snail and N-cadherin expression, leading to increased E-cadherin expression and decreased EMT processes, while a switch occurred upon LINC01133 silencing [

105].

Cervical Tumors

In CvC, LINC01133 is associated with pro-tumorigenic and tumor progression activities. Studies conducted by Feng et al. (2019) [

106] showed a positive differential expression of LINC01133 in RNA-Seq data obtained from TCGA. In vitro assays with Hela, ME-180, C33A and M5751 human tumor cell lines showed, through LINC01133 silencing, qRT-PCR and phenotypic migration and invasion assays, that LINC01133 modulates EMT processes and increases cell invasion and migration capabilities. Through protein predictions and reporter assays, the interaction of miRNAs miR-3065 and miR-4784 with LINC01133 was also determined, with direct endogenous competition between LINC01133 and miR-4784 and the AHDC1 protein (which has two AT-hooks in its structure that enable its effect on transcriptional modulation of genes linked to the EMT process), with binding between LINC01133 and miR-4784 being an important factor for the oncogenic action of AHDC1 [

107], as shown in

Figure 9.

Renal Tumors

LINC01133 plays an oncogenic role in renal tumors (RT), particularly in renal cell carcinomas. Recent studies show its high expression in various renal human tumor cell lines, such as ACHIN, A498, and 786-O. Silencing assays revealed a profound inhibition of migration, proliferation, and cell invasion, while its knockout in mouse models substantially suppressed tumor growth. Interaction prediction assays with miRNA and luciferase reporter assays also demonstrated the action of LINC01133 as a sponge for the miRNA miR-30b-5p, negatively regulating it and, as a consequence, increasing the expression of the Rab3D protein, which is directly associated with tumor growth [

109].

Lv et al. (2022) [

110] also highlighted the sponge activity of LINC01133 with another miRNA, miR-760, similarly negatively regulating it, and acting through the same mechanism as that of miR-30b-5p, leading to increased expression of Rab3D.

Bone Tumors

Although few studies have linked LINC01133 to bone tumors (BC), Zeng et al. (

apud Li, et al., 2018) [

111] demonstrated, through silencing of LINC01133 in an osteosarcoma cell line, a prominent reduction in migration, proliferation and cell invasion in vitro. Strong evidence, from bioinformatics assays and luciferase reporter assays, showed a relationship between LINC01133 and miR-442a, widely known as a tumor-suppressive miRNA, with LINC01133 acting as an lncRNA sponge, inhibiting the action of miR-442a.

Endometrial Tumors

Endometrial tumors (EC) are difficult to diagnose and have seen a sharp increase in both incidence and lethality worldwide in recent decades. Classical lncRNAs such as HOTAIR and MALAT1 have already been shown to be overexpressed in EC, but bioinformatics analyses demonstrate a more intricate network of ncRNAs. Recent studies observed positive differential expression of LINC01133 in EC, enabling silencing assays of LINC01133 in vitro, in Ishikawa and HEC-1-A human cell lines. These assays showed inhibition of tumor invasion and migration mechanisms, as well as induction of cell cycle arrest and apoptotic processes, thus correlating LINC01133 as an oncogenic agent in EC [

112].

4. Conclusions

The study of lncRNAs in pathological contexts, although extremely recent, has already profoundly altered the paradigm of clinical and oncological therapeutic research. Their associations with various tumor-promoting and tumor-suppressing mechanisms open up a range of new possibilities that extend beyond emerging therapies and initiate a potential new era of treatments focused on ncRNAs.

LINC01133, like other lncRNAs of interest, such as HOTAIR, MALAT1, TUG1, and FOXCUT, should be at the forefront of clinical research, considering its importance both in the intratumoral context and in the tumor microenvironment.

Association of LINC01133 with modulation of cell proliferation pathways (Akt/PKB, Wnt/β-Catenin), which are related to regulation of the cell cycle, molecules associated with migration (E-cadherin, N-cadherin, Snail, Slug, Vimentin, Fibronectin), and with invasion and metastatic processes (EZH2, Integrin, TNF-A, EGFR, VEGFR) provides a comprehensive outlook for future research, especially regarding its deep connection with pivotal molecules such as p53, p21, PTEN, c-Myc, and TGF-beta. Additionally, its role as an endogenous competitor, protein scaffold and miRNA sponge is of utmost importance for more detailed investigations.

Thus, we believe that bioinformatics reviews and investigations such as the one presented here should encourage basic and clinical research on LINC01133 and provide periodic updates regarding its great potential in the oncological field.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.T.J.; methodology, L.T.J.; validation, L.T.J.; formal analysis, L.T.J.; investigation, L.T.J.; resources, M.C.S.; data curation, L.T.J.; writing—original draft preparation, L.T.J.; writing—review and editing, M.C.S; visualization, L.T.J.; supervision, M.C.S.; project administration, M.C.S; funding acquisition, M.C.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the following Brazilian research funding agencies: CAPES (Grant No. 88887.646286/2021-00), FAPESP (Thematic Project No. 2016/05311-2) and CNPq (Grant No. 457601/2013-2, 401430/2013-8 and INCT-Regenera 465656/2014-5).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data supporting the findings of this study are available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare. Both co-authors have seen and agreed with the contents of the manuscript and there is no financial interest to report. We certify that the work submitted is original and is not under review by any other publication.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ALL |

Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia |

| AML |

Acute Myeloid Leukemia |

| BC |

Bone cancer/Tumors |

| BLCA |

Bladder Urothelial Carcinoma |

| BLT |

Bladder Tumors |

| bp |

base pair |

| BRC |

Breast Cancer/Tumor |

| BRCA |

Breast Invasive Carcinoma |

| CESC |

Cervical squamous cell carcinoma |

| CLL |

Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia |

| COAD |

Colon Adenocarcinoma |

| CRC |

Colorectal Cancer/Tumor |

| CvC |

Cervical Cancer/Tumors |

| EC |

Endometrium Cancer/Tumors |

| EMT |

Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition |

| EOC |

Epithelial Ovarian Cancer |

| EPT |

Esophageal Tumors |

| ESCC |

Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma |

| ESCC |

Esophageal squamous cell carcinoma |

| GT |

Gastric Cancer/Tumors |

| HCC |

Hepatocellular Carcinoma |

| HpT |

Hepatic Tumors |

| LINC01133 |

Long intergenic non-coding RNA 01133 |

| lncRNA |

long non-coding RNA |

| LSCC |

Lung Squamous Cell Carcinoma |

| LT |

Lung Tumors |

| LUAD |

Lung Adenocarcinoma |

| LUSC |

Lung Squamous Cell Carcinoma |

| MB |

Medulloblastoma |

| miRNAs |

micro RNAs |

| mRNAs |

messenger RNAs |

| ncRNA |

non-coding RNA |

| NPC |

Nasopharyngeal Cancer/Tumors |

| NSCLC |

Non-Small Cells Lung Cancer |

| OSCC |

Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma |

| OVT |

Ovarian Tumors |

| PAAD |

Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma |

| PC |

Pancreatic Cancer/Tumors |

| PDAC |

Pancreactic Ductal Adenocarcinoma |

| RCC |

Renal Cell Carcinoma |

| READ |

Rectum Adenocarcinoma |

| rRNAs |

ribosomic RNAs |

| RT |

Renal Tumors |

| siRNAs |

small interfering RNAs |

| SST |

Somatostatin |

| STAD |

Stomach Adenocarcinoma |

| TNBC |

Triple-Negative Breast Cancer |

| tRNAs |

transporter RNAs |

| UCEC |

Uterine Corpus Endometrial Carcinoma |

References

- Wishart, D.S. Is Cancer a Genetic Disease or a Metabolic Disease? EBioMedicine 2015, 2, 478–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, A.; Huang, Y.; Krajina, B.A.; McBirney, M.; Doak, A.E.; Qu, S.; Wang, C.L.; Haffner, M.C.; Cheung, K.J. Metastasis from the tumor interior and necrotic core formation are regulated by breast cancer-derived angiopoietin-like 7. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2023, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dagogo-Jack, I.; Shaw, A.T. Tumour heterogeneity and resistance to cancer therapies. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2018, 15, 81–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yip, H.Y.K.; Papa, A. Signaling pathways in cancer: Therapeutic targets, combinatorial treatments, and new developments. Cells 2021, 10, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lei, Z.N.; Tian, Q.; Teng, Q.X.; Wurpel, J.N.D.; Zeng, L.; Pan, Y.; Chen, Z.S. Understanding and targeting resistance mechanisms in cancer. MedComm (Beijing) 2023, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mendiratta, G.; Ke, E.; Aziz, M.; Liarakos, D.; Tong, M.; Stites, E.C. Cancer gene mutation frequencies for the U.S. population. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feitelson, M.A.; Arzumanyan, A.; Kulathinal, R.J.; Blain, S.W.; Holcombe, R.F.; Mahajna, J.; Marino, M.; Martinez-Chantar, M.L.; Nawroth, R.; Sanchez-Garcia, I.; Sharma, D.; Saxena, N.K.; Singh, N.; Vlachostergios, P.J.; Guo, S.; Honoki, K.; Fujii, H.; Georgakilas, A.G.; Bilsland, A.; Amedei, A.; Niccolai, E.; Amin, A.; Ashraf, S.S.; Boosani, C.S.; Guha, G.; Ciriolo, M.R.; Aquilano, K.; Chen, S.; Mohammed, S.I.; Azmi, A.S.; Bhakta, D.; Halicka, D.; Keith, W.N.; Nowsheen, S. Sustained proliferation in cancer: Mechanisms and novel therapeutic targets. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2015, 35, S25–S54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamaguchi, H.; Wyckoff, J.; Condeelis, J. Cell migration in tumors. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2005, 17, 559–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krakhmal, N.V.; Zavyalova, M.V.; Denisov, E.V.; Vtorushin, S.V.; Perelmuter, V.M. Perelmuter, Cancer invasion: Patterns; mechanisms. Acta Nat. 2015, 7, 17–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slack, F.J.; Chinnaiyan, A.M. The Role of Non-coding RNAs in Oncology. Cell 2019, 179, 1033–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarroux, J.; Morillon, A.; Pinskaya, M. History, discovery, and classification of lncRNAs. In Adv Exp Med Biol; Springer New York LLC, 2017; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.D.J. LncRNAs: The missing link to senescence nuclear architecture. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2023, 48, 618–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Statello, L.; Guo, C.J.; Chen, L.L.; Huarte, M. Gene regulation by long non-coding RNAs and its biological functions. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2021, 22, 96–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agliano, F.; Rathinam, V.A.; Medvedev, A.E.; Vanaja, S.K.; Vella, A.T. Long Noncoding RNAs in Host–Pathogen Interactions. Trends Immunol. 2019, 40, 492–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biological Function of Long Non-coding RNA (LncRNA) Xist. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Wang, H.; Wang, L.; Wu, W.; Zhao, J.; Li, X.; Xiong, R.; Ding, X.; Yuan, D.; Yuan, C. LncRNA MEG3: Targeting the Molecular Mechanisms and Pathogenic causes of Metabolic Diseases. Curr. Med. Chem. 2023, 31, 6140–6153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghafouri-Fard, S.; Pourtavakoli, A.; Hussen, B.M.; Taheri, M.; Kiani, A. A review on the importance of LINC-ROR in human disorders. Pathol. Res. Pract. 2023, 244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghafouri-Fard, S.; Askari, A.; Moghadam, K.B.; Hussen, B.M.; Taheri, M.; Samadian, M. A review on the role of ZEB1-AS1 in human disorders. Pathol. Res. Pract. 2023, 245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J. Emerging roles of long non-coding RNA FOXP4-AS1 in human cancers: From molecular biology to clinical application. Heliyon 2024, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajagopal, T.; Talluri, S.; Akshaya, R.L.; Dunna, N.R. HOTAIR LncRNA: A novel oncogenic propellant in human cancer. Clin. Chim. Acta 2020, 503, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, X.; Alsager, S.; Zhuo, Y.; Shan, B. HOX transcript antisense RNA (HOTAIR) in cancer. Cancer Lett. 2019, 454, 90–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, F.; Wang, Q.; Wu, Q. The prognostic value and mechanisms of LNCRNA UCA1 in human cancer. Cancer Manag. Res. 2019, 11, 7685–7696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekar, D.; Tusubira, D.; Ross, K. TDP-43 and NEAT long non-coding RNA: Roles in neurodegenerative disease. Front. Cell Neurosci. 2022, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srivastava, D.; Metzler, K.R.C. Fending for a Braveheart. EMBO J. 2013, 32, 1211–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Desideri, F.; Cipriano, A.; Petrezselyova, S.; Buonaiuto, G.; Santini, T.; Kasparek, P.; Prochazka, J.; Janson, G.; Paiardini, A.; Calicchio, A.; Colantoni, A.; Sedlacek, R.; Bozzoni, I.; Ballarino, M. Intronic Determinants Coordinate Charme lncRNA Nuclear Activity through the Interaction with MATR3 and PTBP1. Cell Rep. 2020, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopp, F.; Mendell, J.T. Functional Classification and Experimental Dissection of Long Noncoding RNAs. Cell 2018, 172, 393–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Much, C.; Lasda, E.L.; Pereira, I.T.; Vallery, T.K.; Ramirez, D.; Lewandowski, J.P.; Dowell, R.D.; Smallegan, M.J.; Rinn, J.L. The temporal dynamics of lncRNA Firre-mediated epigenetic and transcriptional regulation. Nat Commun 2024, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herman, A.B.; Tsitsipatis, D.; Gorospe, M. Integrated lncRNA function upon genomic and epigenomic regulation. Mol. Cell 2022, 82, 2252–2266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, M.; Weiswald, L.B.; Poulain, L.; Denoyelle, C.; Meryet-Figuiere, M. Involvement of lncRNAs in cancer cells migration, invasion and metastasis: Cytoskeleton and ECM crosstalk. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2023, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.C.; Chang, H.Y. Molecular Mechanisms of Long Noncoding RNAs. Mol. Cell 2011, 43, 904–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cech, T.R.; Steitz, J.A. The noncoding RNA revolution - Trashing old rules to forge new ones. Cell 2014, 157, 77–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, U.; Barwal, T.S.; Murmu, M.; Acharya, V.; Pant, N.; Dey, D.; Vivek; Gautam, A.; Bazala, S.; Singh, I.; Azzouz, F.; Bishayee, A.; Jain, A. Clinical potential of long non-coding RNA LINC01133 as a promising biomarker and therapeutic target in cancers. Biomark. Med. 2022, 16, 349–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S.; Zhang, Q.; Li, J.; Raziq, K.; Kang, X.; Liang, S.; Sun, C.; Liang, X.; Zhao, D.; Fu, S.; Cai, M. New Sights Into Long Non-Coding RNA LINC01133 in Cancer. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghafouri-Fard, S.; Khoshbakht, T.; Hussen, B.M.; Taheri, M.; Mokhtari, M. A review on the role of LINC01133 in cancers. Cancer Cell Int. 2022, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sayers, E.W.; Bolton, E.E.; Brister, J.R.; Canese, K.; Chan, J.; Comeau, D.C.; Connor, R.; Funk, K.; Kelly, C.; Kim, S.; Madej, T.; Marchler-Bauer, A.; Lanczycki, C.; Lathrop, S.; Lu, Z.; Thibaud-Nissen, F.; Murphy, T.; Phan, L.; Skripchenko, Y.; Tse, T.; Wang, J.; Williams, R.; Trawick, B.W.; Pruitt, K.D.; Sherry, S.T. Database resources of the national center for biotechnology information. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022, 50, D20–D26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruber, A.R.; Lorenz, R.; Bernhart, S.H.; Neuböck, R.; Hofacker, I.L. The Vienna RNA websuite. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magis, C.; Taly, J.F.; Bussotti, G.; Chang, J.M.; Di Tommaso, P.; Erb, I.; Espinosa-Carrasco, J.; Notredame, C. T-coffee: Tree-based consistency objective function for alignment evaluation. Methods Mol. Biol. 2014, 1079, 117–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Procter, J.B.; Carstairs, G.M.; Soares, B.; Mourão, K.; Ofoegbu, T.C.; Barton, D.; Lui, L.; Menard, A.; Sherstnev, N.; Roldan-Martinez, D.; Duce, S.; Martin, D.M.A.; Barton, G.J. Alignment of Biological Sequences with Jalview. In Methods in Molecular Biology; Humana Press Inc., 2021; pp. 203–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, P.W.; Amode, M.R.; Austine-Orimoloye, O.; Azov, A.G.; Barba, M.; Barnes, I.; Becker, A.; Bennett, R.; Berry, A.; Bhai, J.; Bhurji, S.K.; Boddu, S.; Lins, P.R.B.; Brooks, L.; Ramaraju, S.B.; Campbell, L.I.; Martinez, M.C.; Charkhchi, M.; Chougule, K.; Cockburn, A.; Davidson, C.; De Silva, N.H.; Dodiya, K.; Donaldson, S.; El Houdaigui, B.; El Naboulsi, T.; Fatima, R.; Giron, C.G.; Genez, T.; Grigoriadis, D.; Ghattaoraya, G.S.; Martinez, J.G.; Gurbich, T.A.; Hardy, M.; Hollis, Z.; Hourlier, T.; Hunt, T.; Kay, M.; Kaykala, V.; Le, T.; Lemos, D.; Lodha, D.; Marques-Coelho, D.; Maslen, G.; Merino, G.A.; Mirabueno, L.P.; Mushtaq, A.; Hossain, S.N.; Ogeh, D.N.; Sakthivel, M.P.; Parker, A.; Perry, M.; Piližota, I.; Poppleton, D.; Prosovetskaia, I.; Raj, S.; Pérez-Silva, J.G.; Salam, A.I.A.; Saraf, S.; Saraiva-Agostinho, N.; Sheppard, D.; Sinha, S.; Sipos, B.; Sitnik, V.; Stark, W.; Steed, E.; Suner, M.M.; Surapaneni, L.; Sutinen, K.; Tricomi, F.F.; Urbina-Gómez, D.; Veidenberg, A.; Walsh, T.A.; Ware, D.; Wass, E.; Willhoft, N.L.; Allen, J.; Alvarez-Jarreta, J.; Chakiachvili, M.; Flint, B.; Giorgetti, S.; Haggerty, L.; Ilsley, G.R.; Keatley, J.; Loveland, J.E.; Moore, B.; Mudge, J.M.; Naamati, G.; Tate, J.; Trevanion, S.J.; Winterbottom, A.; Frankish, A.; Hunt, S.E.; Cunningham, F.; Dyer, S.; Finn, R.D.; Martin, F.J.; Yates, A.D. Ensembl 2024. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024, 52, D891–D899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frankish, A.; Carbonell-Sala, S.; Diekhans, M.; Jungreis, I.; Loveland, J.E.; Mudge, J.M.; Sisu, C.; Wright, J.C.; Arnan, C.; Barnes, I.; Banerjee, A.; Bennett, R.; Berry, A.; Bignell, A.; Boix, C.; Calvet, F.; Cerdán-Velez, D.; Cunningham, F.; Davidson, C.; Donaldson, S.; Dursun, C.; Fatima, R.; Giorgetti, S.; Giron, C.G.; Gonzalez, J.M.; Hardy, M.; Harrison, P.W.; Hourlier, T.; Hollis, Z.; Hunt, T.; James, B.; Jiang, Y.; Johnson, R.; Kay, M.; Lagarde, J.; Martin, F.J.; Gómez, L.M.; Nair, S.; Ni, P.; Pozo, F.; Ramalingam, V.; Ruffier, M.; Schmitt, B.M.; Schreiber, J.M.; Steed, E.; Suner, M.M.; Sumathipala, D.; Sycheva, I.; Uszczynska-Ratajczak, B.; Wass, E.; Yang, Y.T.; Yates, A.; Zafrulla, Z.; Choudhary, J.S.; Gerstein, M.; Guigo, R.; Hubbard, T.J.P.; Kellis, M.; Kundaje, A.; Paten, B.; Tress, M.L.; Flicek, P. GENCODE: Reference annotation for the human and mouse genomes in 2023. Nucleic Acids Res 2023, 51, D942–D949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Liu, L.; Feng, C.; Qin, Y.; Xiao, J.; Zhang, Z.; Ma, L. LncBook 2.0: Integrating human long non-coding RNAs with multi-omics annotations. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, 51, D186–D191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lun, A.T.L.; McCarthy, D.J.; Marioni, J.C. A step-by-step workflow for low-level analysis of single-cell RNA-seq data with Bioconductor. F1000Res 2016, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerami, E.; Gao, J.; Dogrusoz, U.; Gross, B.E.; Sumer, S.O.; Aksoy, B.A.; Jacobsen, A.; Byrne, C.J.; Heuer, M.L.; Larsson, E.; Antipin, Y.; Reva, B.; Goldberg, A.P.; Sander, C.; Schultz, N. The cBio Cancer Genomics Portal: An open platform for exploring multidimensional cancer genomics data. Cancer Discov. 2012, 2, 401–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schroeder, S.J.; Burkard, M.E.; Turner, D.H. The energetics of small internal loops in RNA. Biopolymers 1999, 52, 157–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsai, M.C.; Manor, O.; Wan, Y.; Mosammaparast, N.; Wang, J.K.; Lan, F.; Shi, Y.; Segal, E.; Chang, H.Y. Long noncoding RNA as modular scaffold of histone modification complexes. Science (1979) 2010, 329, 689–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, K.; Xiao, Y.; Zhong, L.; Zhang, W.; Wang, P.; Ren, Y.; Shi, L. p53-regulated lncRNAs in cancers: From proliferation and metastasis to therapy. Cancer Gene Ther. 2023, 30, 1456–1470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulak, M.; Fong, L.; Mika, K.; Chigurupati, S.; Yon, L.; Mongan, N.P.; Emes, R.D.; Lynch, V.J. TP53 copy number expansion is associated with the evolution of increased body size and an enhanced DNA damage response in elephants. Elife 2016, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chusyd, D.E.; Ackermans, N.L.; Austad, S.N.; Hof, P.R.; Mielke, M.M.; Sherwood, C.C.; Allison, D.B. Aging: What We Can Learn From Elephants. Front. Aging 2021, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, L.D.; Le, T.; Fan, G. DNA methylation and its basic function. Neuropsychopharmacology 2013, 38, 23–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Xiong, F.; Wu, G.; Liu, W.; Chen, J.; Wang, B.; Chen, Y. Gene body methylation in cancer: Molecular mechanisms and clinical applications. Clin. Epigenetics 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulis, M.; Queirós, A.C.; Beekman, R.; Martín-Subero, J.I. Intragenic DNA methylation in transcriptional regulation, normal differentiation and cancer. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Gene Regul. Mech. 2013, 1829, 1161–1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duchartre, Y.; Kim, Y.M.; Kahn, M. The Wnt signaling pathway in cancer. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2016, 99, 141–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rim, E.Y.; Clevers, H.; Nusse, R. The Wnt Pathway: From Signaling Mechanisms to Synthetic Modulators. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2022, 91, 571–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnamurthy, N.; Kurzrock, R. Targeting the Wnt/beta-catenin pathway in cancer: Update on effectors and inhibitors. Cancer Treat. Rev. 2018, 62, 50–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holzem, M.; Boutros, M.; Holstein, T.W. The origin and evolution of Wnt signalling. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2024, 25, 500–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanova, M.M.; Dao, J.; Kasaci, N.; Friedman, A.; Noll, L.; Goker-Alpan, O. Wnt signaling pathway inhibitors, sclerostin and DKK-1, correlate with pain and bone pathology in patients with Gaucher disease. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aubrey, B.J.; Strasser, A.; Kelly, G.L. Tumor-suppressor functions of the TP53 pathway. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2016, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández Borrero, L.J.; El-Deiry, W.S. Tumor suppressor p53: Biology; signaling pathways; therapeutic targeting. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Rev. Cancer 2021, 1876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eischen, C.M.; Lozano, G. The mdm network and its regulation of p53 activities: A rheostat of cancer risk. Hum. Mutat. 2014, 35, 728–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimian, A.; Ahmadi, Y.; Yousefi, B. Multiple functions of p21 in cell cycle, apoptosis and transcriptional regulation after DNA damage. DNA Repair (Amst) 2016, 42, 63–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, C.; Mei, W.; Zeng, C. PI3K/Akt/mTOR Pathway and Its Role in Cancer Therapeutics: Are We Making Headway? Front. Oncol. 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghareghomi, S.; Habibi-Rezaei, M.; Arese, M.; Saso, L.; Moosavi-Movahedi, A.A. Nrf2 Modulation in Breast Cancer. Biomedicines 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Z.; Fan, T.; Xiao, C.; Tian, H.; Zheng, Y.; Li, C.; He, J. TGF-β signaling in health; disease; therapeutics. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2024, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tauriello, D.V.F.; Sancho, E.; Batlle, E. Overcoming TGFβ-mediated immune evasion in cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2022, 22, 25–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhanasekaran, R.; Deutzmann, A.; Mahauad-Fernandez, W.D.; Hansen, A.S.; Gouw, A.M.; Felsher, D.W. The MYC oncogene — the grand orchestrator of cancer growth and immune evasion. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2022, 19, 23–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sundaram, M.V. Canonical RTK-Ras-ERK signaling and related alternative pathways. WormBook 2013, 1–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, L.; Mishra, L.; Sharma, Y.; Chahar, K.; Kumar, M.; Patel, P.; Das Gupta, G.; Das Kurmi, B. NOTCH Signaling Pathway: Occurrence, Mechanism, and NOTCH-Directed Therapy for the Management of Cancer. Cancer Biother. Radiopharm. 2024, 39, 19–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, A.; Gessler, M. Delta-Notch-and then? Protein interactions and proposed modes of repression by Hes and Hey bHLH factors. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007, 35, 4583–4596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, S.; Meng, Z.; Chen, R.; Guan, K.L. Guan, The hippo pathway: Biology; pathophysiology. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2019, 88, 577–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennell, J.; Cadigan, K.M. APC and β-catenin degradation. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2009, 656, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lü, Y.Q.; Cho, T.; Mukherjee, S.; Suarez, C.F.; Gonzalez-Foutel, N.S.; Malik, A.; Martinez, S.; Dervovic, D.; Oh, R.H.; Langille, E.; Al-Zahrani, K.N.; Hoeg, L.; Lin, Z.Y.; Tsai, R.; Mbamalu, G.; Rotter, V.; Ashton-Prolla, P.; Moffat, J.; Chemes, L.B.; Gingras, A.C.; Oren, M.; Durocher, D.; Schramek, D. Genome-wide CRISPR screens identify novel regulators of wild-type and mutant p53 stability. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2024, 20, 719–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhu, N.; Chen, X. A novel long noncoding RNA LINC01133 is upregulated in lung squamous cell cancer and predicts survival. Tumor Biol. 2015, 36, 7465–7471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zang, C.; Nie, F.Q.; Wang, Q.; Sun, M.; Li, W.; He, J.; Zhang, M.; Lu, K.H. Long non-coding RNA LINC01133 represses KLF2, P21 and E-cadherin transcription through binding with EZH2, LSD1 in non small cell lung cancer. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 11696–11707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Ma, X.; Zhu, C.; Guo, L.; Li, Q.; Liu, M.; Zhang, J. The prognostic value of long non coding RNAs in non small cell lung cancer: A meta-analysis. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 81292–81304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Shi, W.; Chen, R.; Gu, Y.; Zhao, M.; Song, J.; Shi, Z.; Wu, J.; Chang, H.W.; Liu, M. LINC01133 regulates MARCKS expression via sponging miR-30d-5p to promote the development of lung squamous cell carcinoma. Transl. Oncol. 2024, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, X.; Liu, Y.; Li, Y.; Ji, X.; Yun, Y.; Yang, G.; Liu, H.; Liang, X.; Yang, S. LINC01133 contributes to the malignant phenotypes of non-small cell lung cancer by targeting miR-30b-5p/FOXA1 pathway. Cell Mol. Biol. 2024, 70, 42–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong, J.; Sun, W.; Li, C.; Wan, L.; Wang, S.; Wu, Y.; Xu, E.; Zhang, H.; Lai, M. Long non-coding RNA LINC01133 inhibits epithelial–mesenchymal transition and metastasis in colorectal cancer by interacting with SRSF6. Cancer Lett. 2016, 380, 476–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- gianni, Downregulation of long non-coding RNA LINC01133 is predictive of poor prognosis in colorectal cancer patients. (n.d.) Https://Www.Europeanreview.Org/Article/12686.

- Yao, Y.; Zhang, F.; Liu, F.; Xia, D. Propofol-induced LINC01133 inhibits the progression of colorectal cancer via miR-186-5p/NR3C2 axis. Env. Toxicol. 2024, 39, 2265–2284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, Z.; Schmöllerl, J.; Cuiffo, B.G.; Karnoub, A.E. Microenvironmental Regulation of Long Noncoding RNA LINC01133 Promotes Cancer Stem Cell-Like Phenotypic Traits in Triple-Negative Breast Cancers. Stem Cells 2019, 37, 1281–1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Z.; Zhang, X.; Lin, Y.; Wei, Y.; Liang, S.; Dong, C. LINC01133 inhibits breast cancer invasion and metastasis by negatively regulating SOX4 expression through EZH2. J. Cell Mol. Med. 2019, 23, 7554–7565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Layeghi, S.M.; Arabpour, M.; Shakoori, A.; Naghizadeh, M.M.; Mansoori, Y.; Bazzaz, J.T.; Esmaeili, R. Expression profiles and functional prediction of long non-coding RNAs LINC01133, ZEB1-AS1 and ABHD11-AS1 in the luminal subtype of breast cancer. J. Transl. Med. 2021, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Shen, C.; Wang, C. Long Noncoding RNA LINC01133 Confers Tumor-Suppressive Functions in Ovarian Cancer by Regulating Leucine-Rich Repeat Kinase 2 as an miR-205 Sponge. Am. J. Pathol. 2019, 189, 2323–2339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Xi, X. LINC01133 contribute to epithelial ovarian cancer metastasis by regulating miR-495-3p/TPD52 axis. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2020, 533, 1088–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Qu, H.; Huang, H.; Mu, Z.; Mao, M.; Xie, Q.; Wang, K.; Hu, B. Exosomes-mediated transfer of long noncoding RNA LINC01133 represses bladder cancer progression via regulating the Wnt signaling pathway. Cell Biol. Int. 2021, 45, 1510–1522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, D.; Hu, Z.Q.; Luo, C.B.; Wang, X.Y.; Xin, H.Y.; Sun, R.Q.; Wang, P.C.; Li, J.; Fan, J.; Zhou, Z.J.; Zhou, J.; Zhou, S.L. LINC01133 promotes hepatocellular carcinoma progression by sponging miR-199a-5p and activating annexin A2. Clin. Transl. Med. 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.F.; Zhang, X.Y.; Bu, Y.Z. LINC01133 aggravates the progression of hepatocellular carcinoma by activating the PI3K/AKT pathway. J. Cell Biochem. 2019, 120, 4172–4179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.S.; Chu, J.; Zhu, X.X.; Li, J.H.; Huang, X.T.; Cai, J.P.; Zhao, W.; Yin, X.Y. The C/EBPβ-LINC01133 axis promotes cell proliferation in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma through upregulation of CCNG1. Cancer Lett. 2018, 421, 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giulietti, M.; Righetti, A.; Principato, G.; Piva, F. LncRNA co-expression network analysis reveals novel biomarkers for pancreatic cancer. Carcinogenesis 2018, 39, 1016–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, Y.C.; Ma, J.; Zhang, J.; Wang, J.C. Long non-coding RNA LINC01133 silencing exerts antioncogenic effect in pancreatic cancer through the methylation of DKK1 promoter and the activation of Wnt signaling pathway. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2019, 20, 368–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Gao, S.; Zhang, Y.; Yi, H.; Xu, M.; Xu, J.; Liu, H.; Ding, Z.; He, H.; Wang, H.; Hao, Z.; Sun, L.; Liu, Y.; Wei, F. Mir-216a-5p inhibits tumorigenesis in pancreatic cancer by targeting tpt1/mtorc1 and is mediated by linc01133. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2020, 16, 2612–2627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Tang, T.; Yang, X.; Qin, P.; Wang, P.; Zhang, H.; Bai, M.; Wu, R.; Li, F. Tumor-derived exosomal long noncoding RNA LINC01133, regulated by Periostin, contributes to pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma epithelial-mesenchymal transition through the Wnt/β-catenin pathway by silencing AXIN2. Oncogene 2021, 40, 3164–3179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Wang, L.; Zhou, F.; Ye, S.; Sun, Q. Yin Yang 1-induced activation of LINC01133 facilitates the progression of pancreatic cancer by sponging miR-199b-5p to upregulate myelin regulatory factor expression. Bioengineered 2022, 13, 13352–13365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; He, X.; Yao, R.; Fan, L.; Zhao, L.; Lu, B.; Pang, Z. Genome instability-related LINC02577, LINC01133 and AC107464.2 are lncRNA prognostic markers correlated with immune microenvironment in pancreatic adenocarcinoma. BMC Cancer 2023, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Lin, J.; Ji, Y.; Wang, X.; Fu, D.; Wang, W.; Shen, B. A novel pyroptosis-associated lncRNA LINC01133 promotes pancreatic adenocarcinoma development via miR-30b-5p/SIRT1 axis. Cell. Oncol. 2023, 46, 1381–1398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Jiang, F.; Chen, F.; Deng, Y.; Huang, H. Silencing long noncoding RNA LINC01133 suppresses pancreatic cancer through regulation of microRNA-1299-dependent IGF2BP3. J. Biochem. Mol. Toxicol. 2024, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Gong, Y.; Ding, Y.; Sun, S.; Bai, R.; Zhuo, S.; Zhang, Z. LINC01133 promotes pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma epithelial–mesenchymal transition mediated by SPP1 through binding to Arp3. Cell Death Dis. 2024, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.Z.; He, Q.J.; Cheng, T.T.; Chi, J.; Lei, Z.Y.; Tang, Z.; Liao, Q.X.; Zhang, H.; Zeng, L.S.; Cui, S.Z. Predictive Value of LINC01133 for Unfavorable Prognosis was Impacted by Alcohol in Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 2018, 48, 251–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, J.; Sun, W.; Zhu, W.; Liu, C.; Zhang, H.; Wang, H. Long noncoding RNA LINC01133 inhibits oral squamous cell carcinoma metastasis through a feedback regulation loop with GDF15. J. Surg. Oncol. 2018, 118, 1326–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.Z.; Cheng, T.T.; He, Q.J.; Lei, Z.Y.; Chi, J.; Tang, Z.; Liao, Q.X.; Zhang, H.; Zeng, L.S.; Cui, S.Z. LINC01133 as ceRNA inhibits gastric cancer progression by sponging miR-106a-3p to regulate APC expression and the Wnt/β-catenin pathway. Mol. Cancer 2018, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foroughi, K.; Amini, M.; Atashi, A.; Mahmoodzadeh, H.; Hamann, U.; Manoochehri, M. Tissue-specific down-regulation of the long non-coding RNAs PCAT18 and LINC01133 in gastric cancer development. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Pan, K.; Zuo, Z.; Ye, F.; Cao, D.; Peng, Y.; Tang, T.; Li, X.; Zhou, S.; Duan, L. LINC01133 hampers the development of gastric cancer through increasing somatostatin via binding to microRNA-576-5p. Epigenomics 2021, 13, 1205–1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Tian, Y.; He, J.; Tian, Y.; Zhang, G.; Zhao, R.; Zhu, W.J.; Gao, P. Linc01133 contributes to gastric cancer growth by enhancing YES1-dependent YAP1 nuclear translocation via sponging miR-145-5p. Cell Death Dis. 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sui, X.; Zhang, Q.; Hao, M.; Chen, Y. Serum LINC01133 combined with CEA and CA19-9 contributes to the diagnosis and survival prognosis of gastric cancer. Medicine 2024, 103, e40564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W.; Du, M.; Wang, T.; Chen, W.; Wu, J.; Li, Q.; Tian, X.; Qian, L.; Wang, Y.; Peng, F.; Fei, Q.; Chen, J.; He, X.; Yin, L. Long non-coding RNA LINC01133 mediates nasopharyngeal carcinoma tumorigenesis by binding to YBX1. Am. J. Cancer Res. 2019, 9, 779–790. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, Y.; Qu, L.; Wang, X.; Liu, C. LINC01133 promotes the progression of cervical cancer by sponging miR-4784 to up-regulate AHDC1. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2019, 20, 1453–1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, S.; Huang, X.; Zhu, J.; Xu, B.; Xu, L.; Gu, D.; Zhang, W. ADH7, miR–3065 and LINC01133 are associated with cervical cancer progression in different age groups. Oncol. Lett. 2020, 19, 2326–2338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.J.; Wang, D.; Zhao, M.; Sun, X.J.; Li, Y.; Lin, H.; Che, Y.Q.; Huang, C.Z. Serum lncrnas (Ccat2, linc01133, linc00511) with squamous cell carcinoma antigen panel as novel non-invasive biomarkers for detection of cervical squamous carcinoma. Cancer Manag. Res. 2020, 12, 9495–9502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, X.; Wu, Y.; Wang, Z.; Zhao, D.; Li, H.; Chong, T.; Zhao, J. Long Noncoding RNA LINC01133 Promotes the Malignant Behaviors of Renal Cell Carcinoma by Regulating the miR-30b-5p/Rab3D Axis. Cell Transpl. 2020, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, W.; Li, Y.; Fu, L.; Meng, F.; Li, J. Linc01133 promotes proliferation and metastasis of human renal cell carcinoma through sponging miR-760. Cell Cycle 2022, 21, 1502–1511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Xu, D.; Chen, X.; Li, S.; Chan, M.T.V.; Wu, W.K.K. LINC01133: An emerging tumor-associated long non-coding RNA in tumor and osteosarcoma. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 32467–32473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Yue, Y.; Yin, F.; Qi, Z.; Guo, R.; Xu, Y. LINC01133 and LINC01243 are positively correlated with endometrial carcinoma pathogenesis. Arch. Gynecol. Obs. 2021, 303, 207–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).