3.3. Cyclic Loading Tests

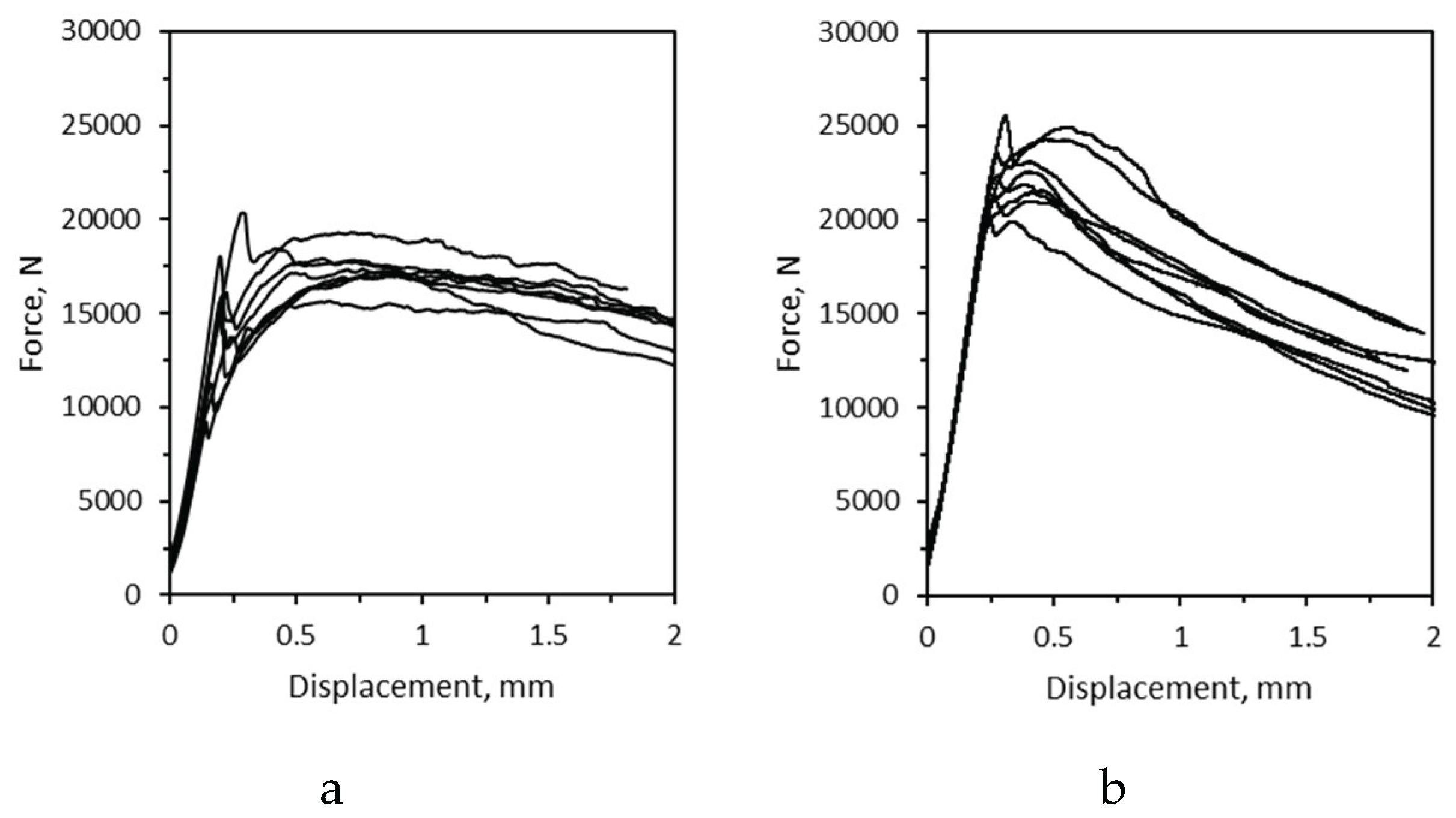

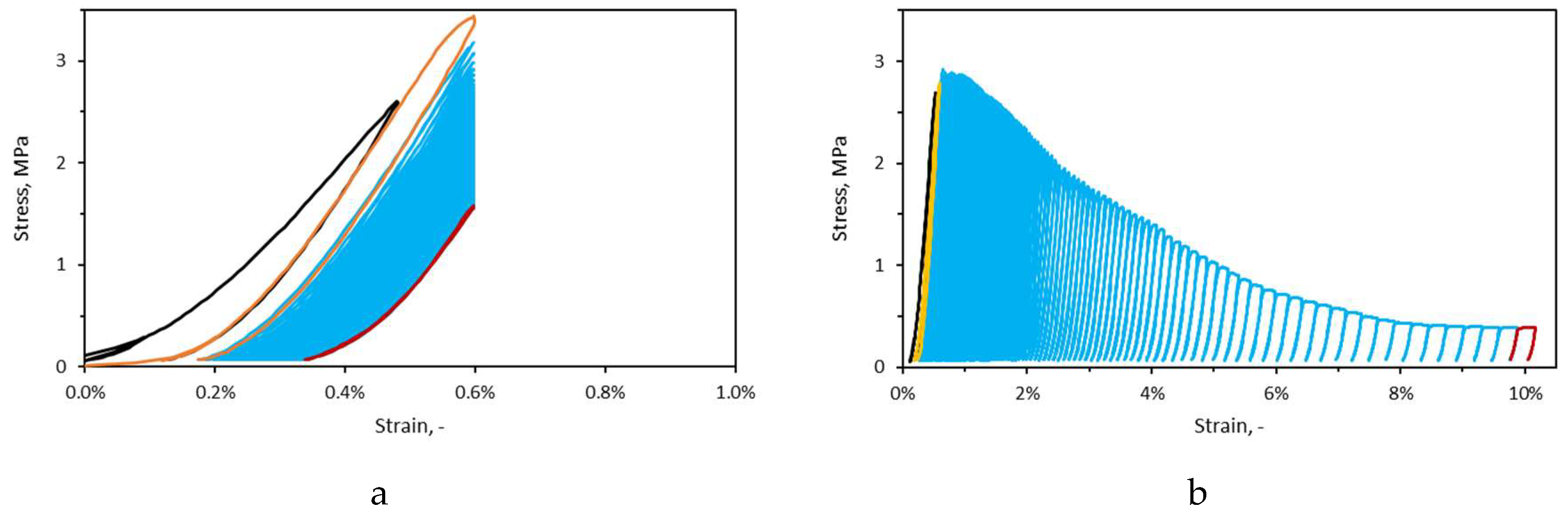

Stress-strain curves of two medium intensity cyclic tests of method II and III are shown as examples in

Figure 5. For the former the strain limit is 0.48% and for the latter the strain amplitude is 0.4%. In method III (

Figure 5-b), the development of every cycle follows the stress-strain envelope of the sample. One can clearly distinct the pre-peak, peak and post peak area. While in method II (

Figure 5-a), peak and post-peak areas may not develop. As strain at maximal stress and strain of linear proportion (SNLP) of IFB 28 are 0.6%, 0.44%, respectively, one can expect the peak stress in case of sample of method II is reached. However, as the upper limits strain in method II is constant, the post peak part of the envelope is not developed. Unlike the example of method II, the presence of a well-developed post peak area is obvious in the example of method III.

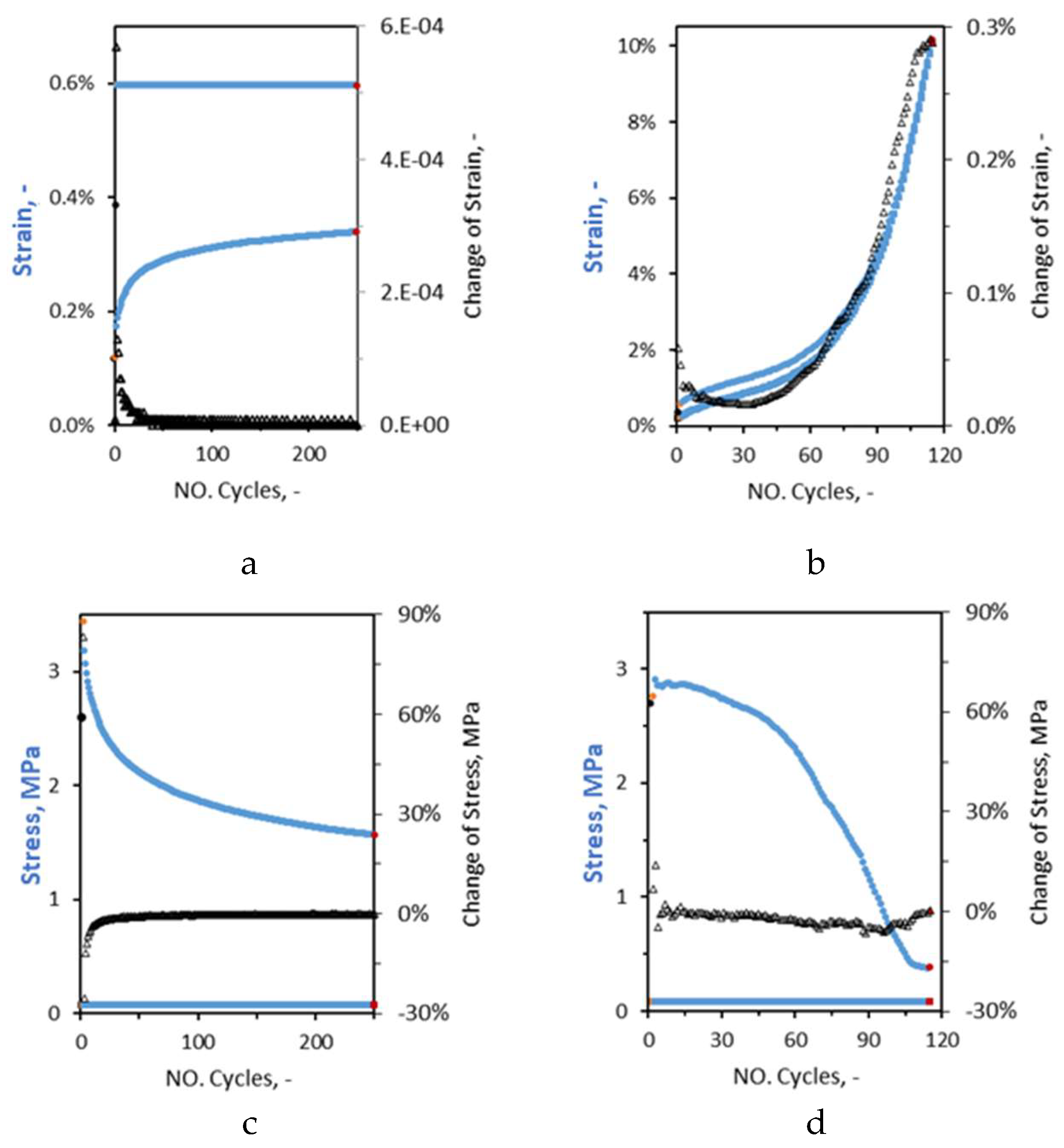

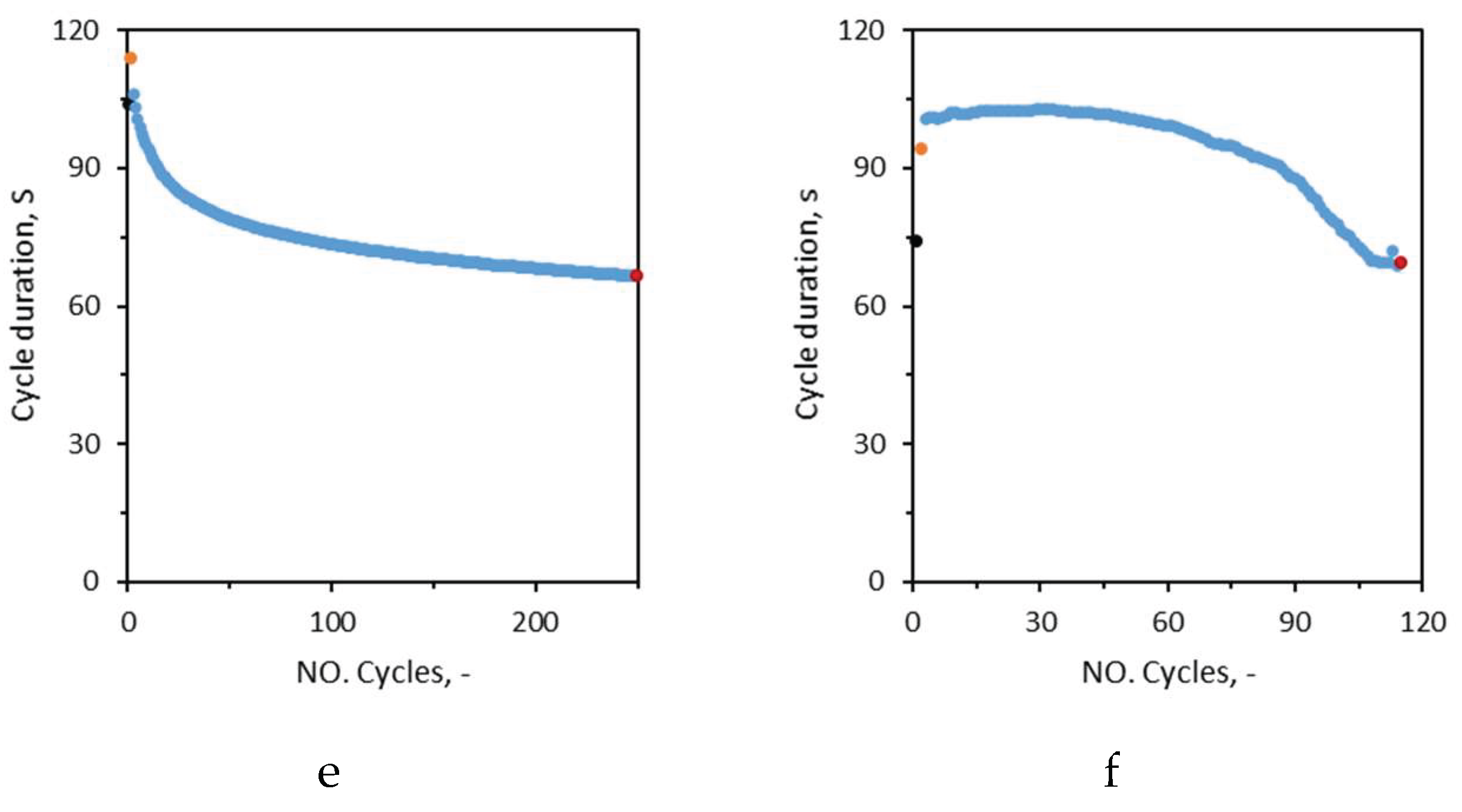

From stress-strain curves of

Figure 5 several parameters were extracted and are shown distinctly in two series of graphs for each method’s example (

Figure 6). The parameters are strain (

Figure 6-a,b), stress (

Figure 6-c,d) and cycle’s duration (

Figure 6-e,f) with respect to the number of cycles. This was done to show the evolution of each parameter in the lower and upper limits of every cycle. Comparing the evolution of strain at the limits in method II and method III examples, one can note the evolution of strain in method III shows three phases of fatigue degradation. Strain initially sharply increases, then the rate of changes calms shortly (phase II) and follows by an exponential increase up to failure (phase III). Whereas in case of method II’s example only the first two phases of fatigue were witnessed. Strain initially increases exponentially (phase I) but shortly after, the rate of increase stagnates and becomes almost constant (phase II). The difference becomes more obvious to the eyes by comparing the change of strain (black) curves. Even though the upper limits strain is growing in method III’s example, in case of method II it was kept constant (

Figure 6-a,b). Evolution of stress in upper limits follows a different trend in method II and method III. In method III, the stress increases in the first few cycles (positive values) whereas in method II stress of only the second cycle (yellow dot) may be higher than the first cycle and then it starts to decrease. Change of stress in every consecutive cycle (black curves -

Figure 6-c,d) becomes almost constant and remain negative. As the extent of damage is more significant in example of method III than method II, one can note the closeness of upper and lowers stresses (red dots –

Figure 6-c,d) in method III than method II. In terms of cycle’s duration examples of method II and method III could be compared. In general, it follows a similar trend as of upper stress limits. In method II, second cycle is longest cycle where the highest stress was recorded. After the first few cycles, the cycles become abruptly shorter (phase I) and then the rate tends to slow down, but keeps decreasing in case of method II (incomplete phase II). In case of method III, the first few cycles become lengthier (phase I) and then almost constant during phase II. With the start of phase III, the cycles become gradually shorter. By comparison of the position of black and red dots in

Figure 6-e,f, one can note that the duration of the last cycle in method II is significantly lower than the first cycle, whereas in case of method III the difference is less (5 s, 7%).The consecutive cycles in the cyclic tests of method II become consistently shorter as the accumulated strain gets closer to the defined strain limit, but in the cyclic tests of method III strain grows and accumulates with the cycles up to the failure.

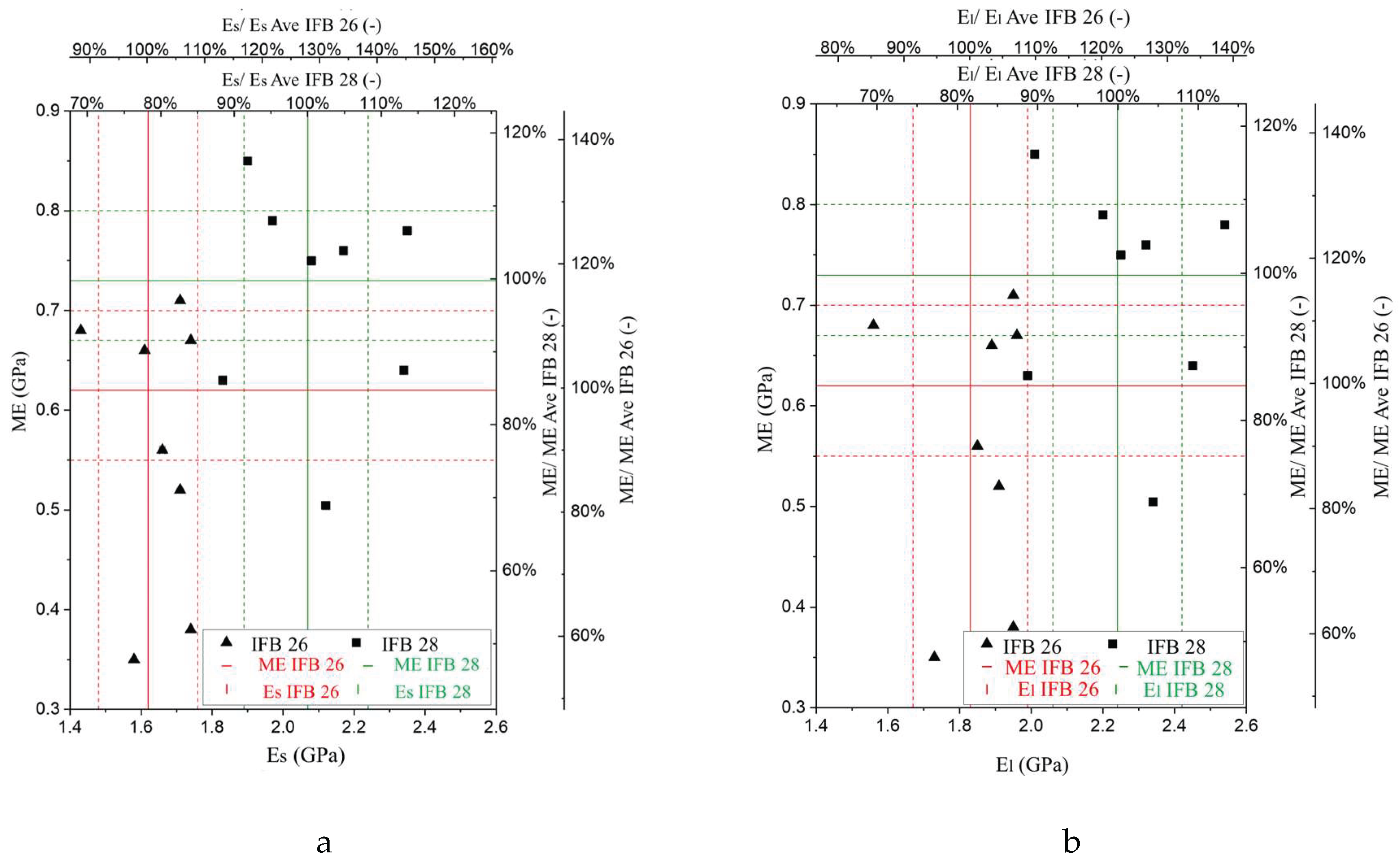

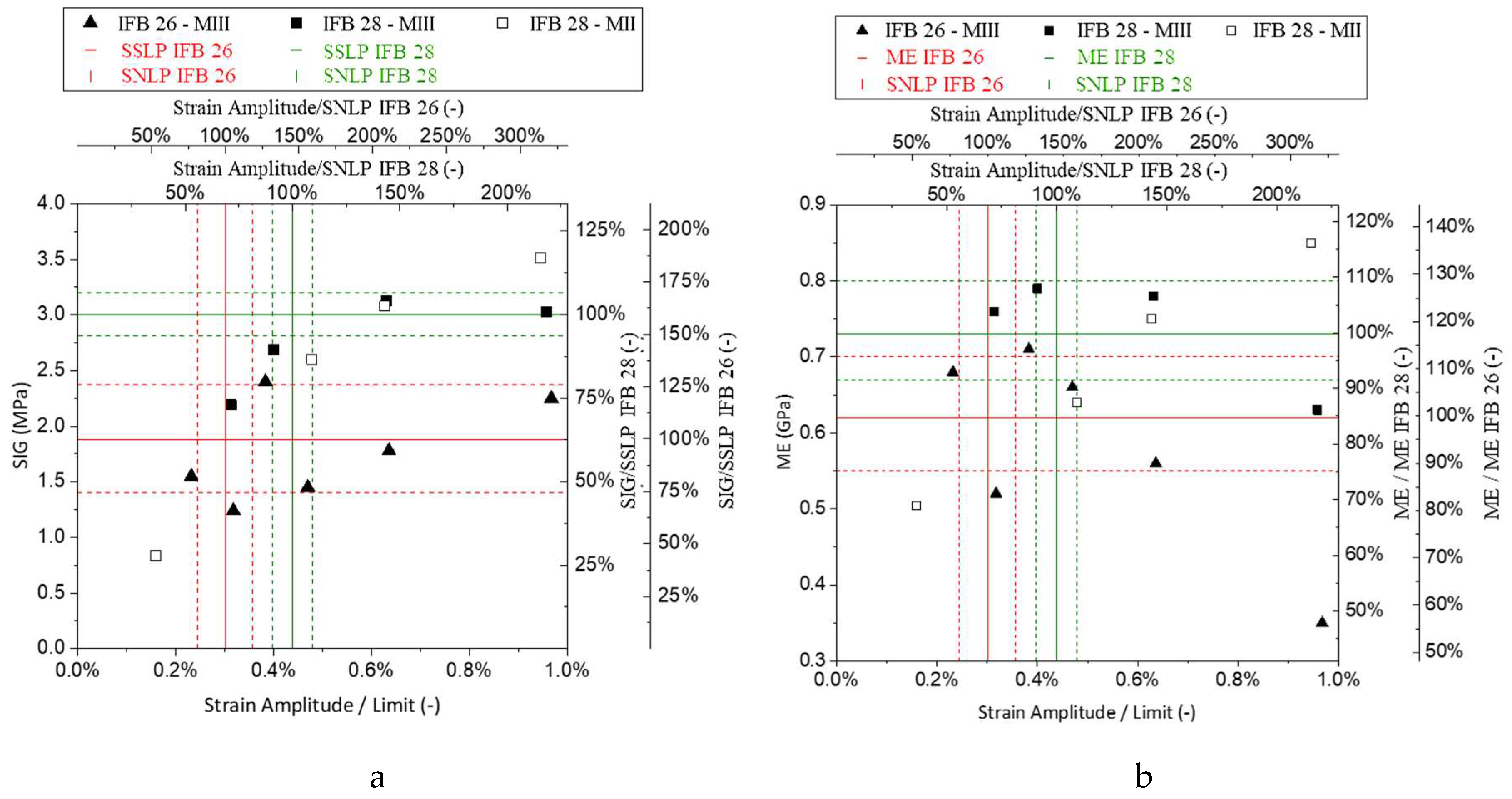

The maximal stress (SIG) every first cycle reached and its modulus of elasticity (ME) are depicted in

Figure 7. It can be noted with the increase of strain amplitude/limit the corresponding first cycle reaches a higher SIG value. The SIG values approach peak stress values obtained from monotonic tests, especially for strain amplitudes/limits close and above SNLP limit of the materials. It can be seen for similar strain amplitudes, IFB 28 samples reached higher SIG values than IFB 26 samples. This is in line with lower peak stress of IFB 26 than IFB 28 obtained from monotonic loading tests. Unlike SIG, ME of the first cycles with respect to strain amplitude/limit do not show any specific trend, rather mostly scatter within the range of ME values obtained from monotonic loading tests.

3.4. Damage Indicators and Degradation Process

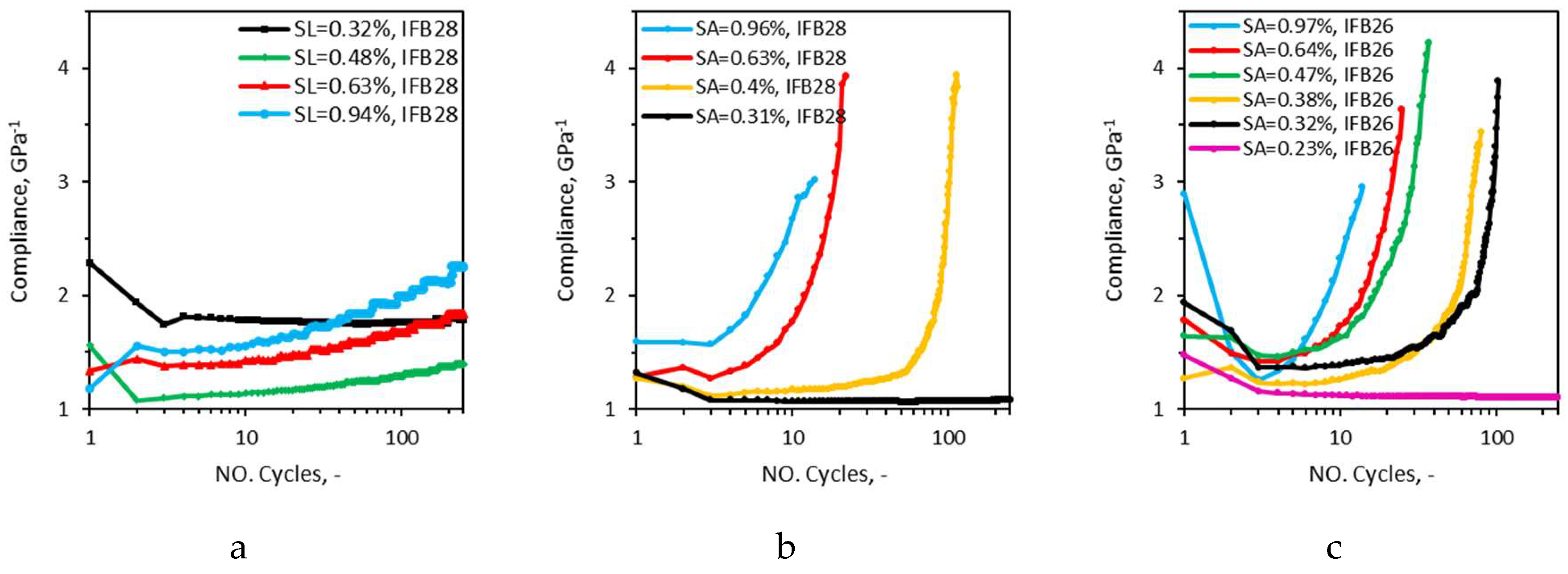

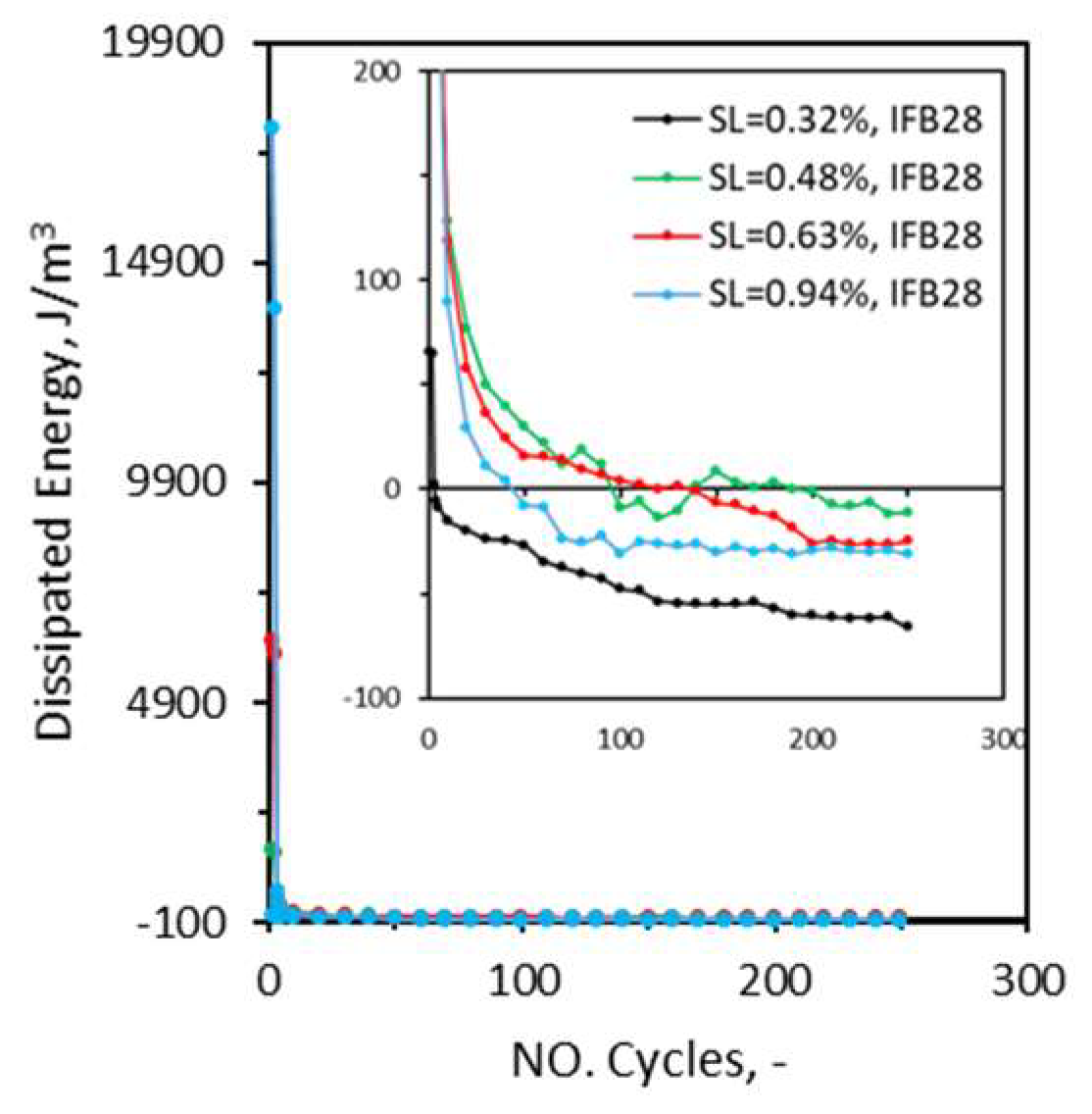

The evolution of damage in the materials could be compared in terms of compliance (

Figure 8-a,b,c), irreversible strain (

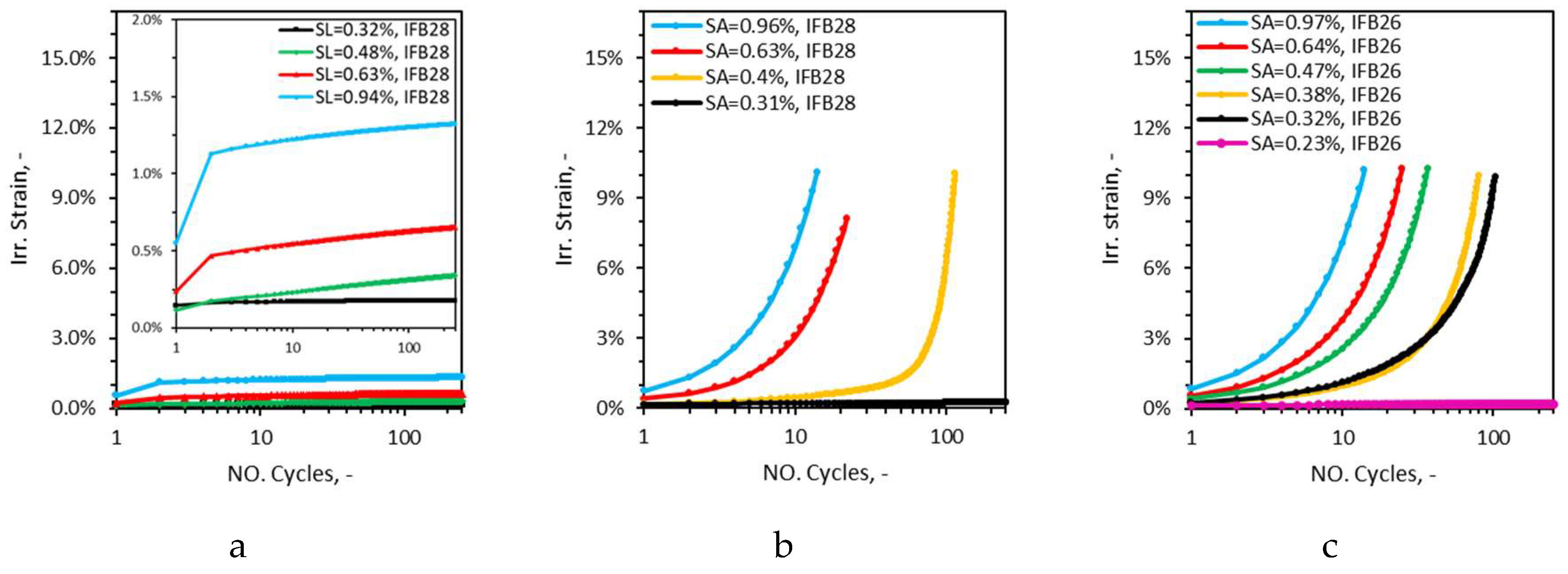

Figure 9-a,b,c), strain rate (

Figure 10-a,b,c) and dissipated energy (

Figure 11-

Figure 12) between method II and method III. As only IFB 28 was tested in method II and method III, the material comparison would be limited to method III results and methods comparison would be limited to IFB 28 results.

Figure 8.

Evolution of compliance with number of cycles in cyclic tests of method II (a) and method III, IFB28(b) and IFB26(c), SL-strain limit and SA-strain amplitude.

Figure 8.

Evolution of compliance with number of cycles in cyclic tests of method II (a) and method III, IFB28(b) and IFB26(c), SL-strain limit and SA-strain amplitude.

Figure 9.

Evolution of irreversible strain with number of cycles in cyclic tests of method II (a) and method III, IFB28(b) and IFB26(c), SL-strain limit and SA-strain amplitude.

Figure 9.

Evolution of irreversible strain with number of cycles in cyclic tests of method II (a) and method III, IFB28(b) and IFB26(c), SL-strain limit and SA-strain amplitude.

Figure 10.

Evolution of strain rate with number of cycles in cyclic tests of method II (a) and method III, IFB28(b) and IFB26(c), SL-strain limit and SA-strain amplitude.

Figure 10.

Evolution of strain rate with number of cycles in cyclic tests of method II (a) and method III, IFB28(b) and IFB26(c), SL-strain limit and SA-strain amplitude.

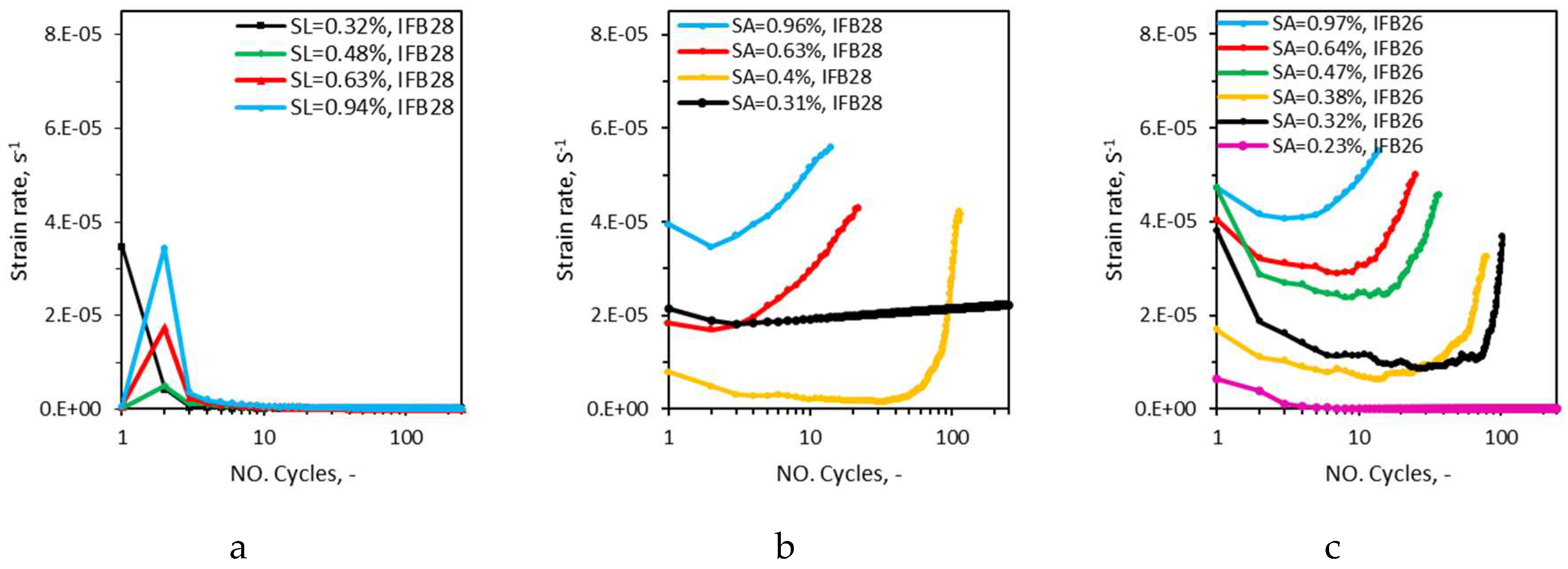

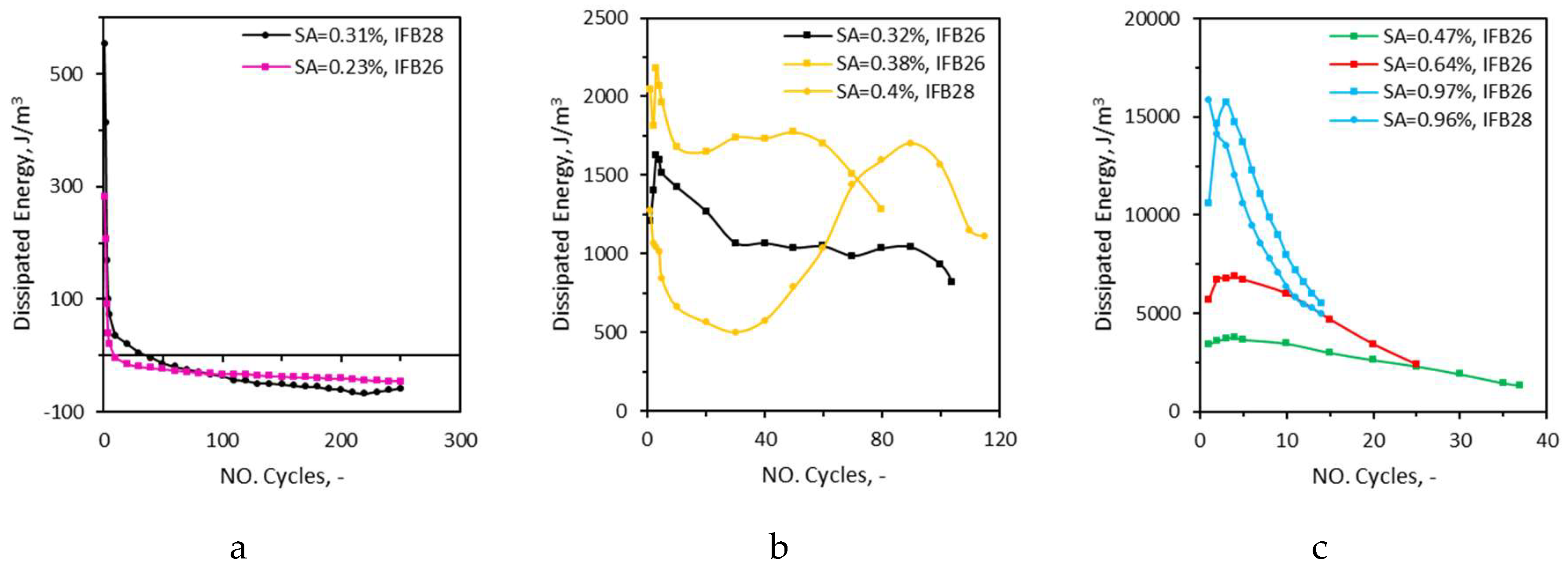

Figure 11.

Evolution of dissipated energy with number of cycles in cyclic tests of method II, SL-strain limit.

Figure 11.

Evolution of dissipated energy with number of cycles in cyclic tests of method II, SL-strain limit.

Figure 12.

Evolution of dissipated energy with number of cycles in cyclic tests of method III, low (a), medium (b) and high (c) strain amplitudes, SA-strain amplitude.

Figure 12.

Evolution of dissipated energy with number of cycles in cyclic tests of method III, low (a), medium (b) and high (c) strain amplitudes, SA-strain amplitude.

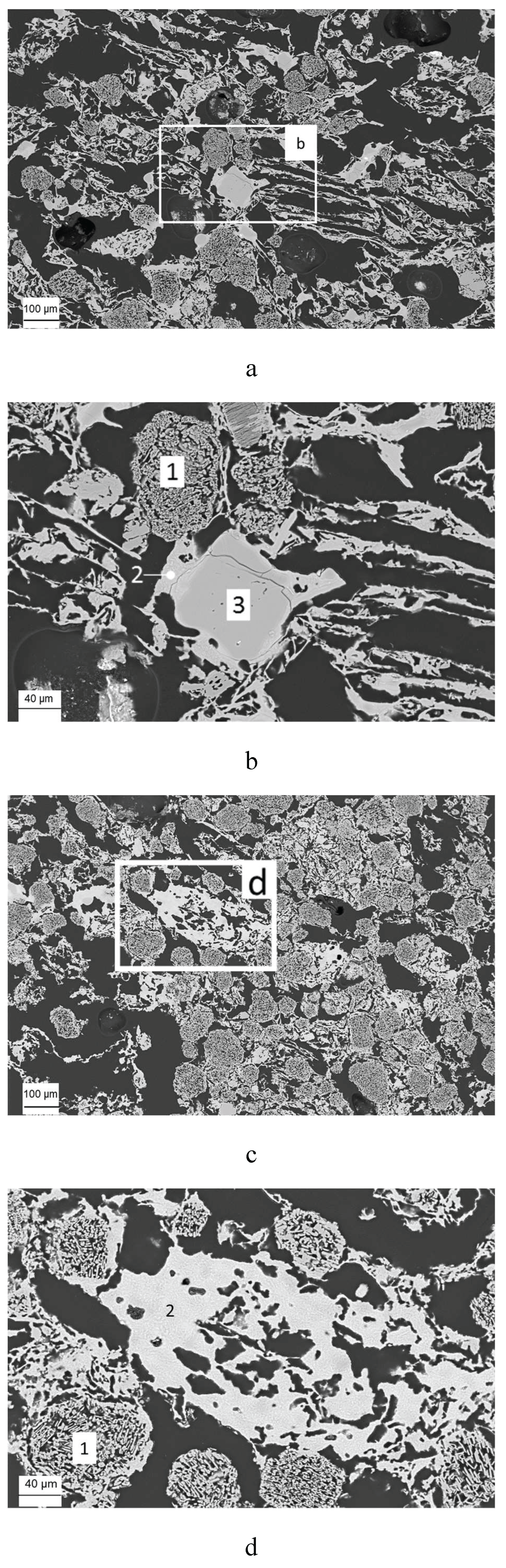

In case of method III, compliance and strain rate curves form a bath-tub shape, whereas in case of method II, as the third phase of fatigue is not developed, the last part of the tub shape (exponential increase) is replaced by a rather steady line. In case of method III, irreversible strain forms an exponential shape, however again as the third phase of fatigue is not developed in method II, after the second cycle irreversible strain forms a line with a slightly increasing slope. The slope of the line increases in every case with the increase of strain limit. The black curve, which had strain limit of 0.32%, shows almost no degradation, after the second cycle all three parameters stay constant throughout the measurement. The blue curve presents the steepest increase among all curves which has a strain limit of 0.94%. In case of method III curves also colours are representative of a similar magnitude of strain amplitude, instead of strain limits. In case of method III curves, the blue curves do not necessarily have the steepest slope, but rather shifted toward the left of the plot. As with increasing strain amplitude, the second phase of fatigue becomes shorter, earlier (in terms of number of cycles) the exponential increase (phase III) kicks off. The black curve remains steady with no (limited) sign of damage. However, the black curve, which has strain amplitude of 0.32% in the case of IFB 26 demonstrate fatigue degradation which was not the case for IFB 28. This can be explained by recalling the strain of linear proportion (SNLP) of the materials. The strain amplitude of the black curve 0.31% is lower than the SNLP of IFB 28 (0.44%) but higher than SNLP of IFB 26 (0.30%). The pink curve, which has strain amplitude of 0.23% develops no damage throughout the measurement again as its strain amplitude is lower than SNLP of IFB 26.

When the loading and unloading curves fully overlap, the energy put into the sample is recovered after removal of the load and sample returns to its original state. Otherwise, the energy is lost in the form of heat or damage in the sample [

32]. During cyclic loading the dissipated energy by heat stays almost constant [

33]. For this, the change in dissipated energy in consecutive cycles is related to the degradation of the sample [

26]. A crack within the microstructure would only propagate, if there is a change in the dissipated energy of two consecutive cycles [

34]. The extent of degradation is higher when more energy is dissipated in a cycle.

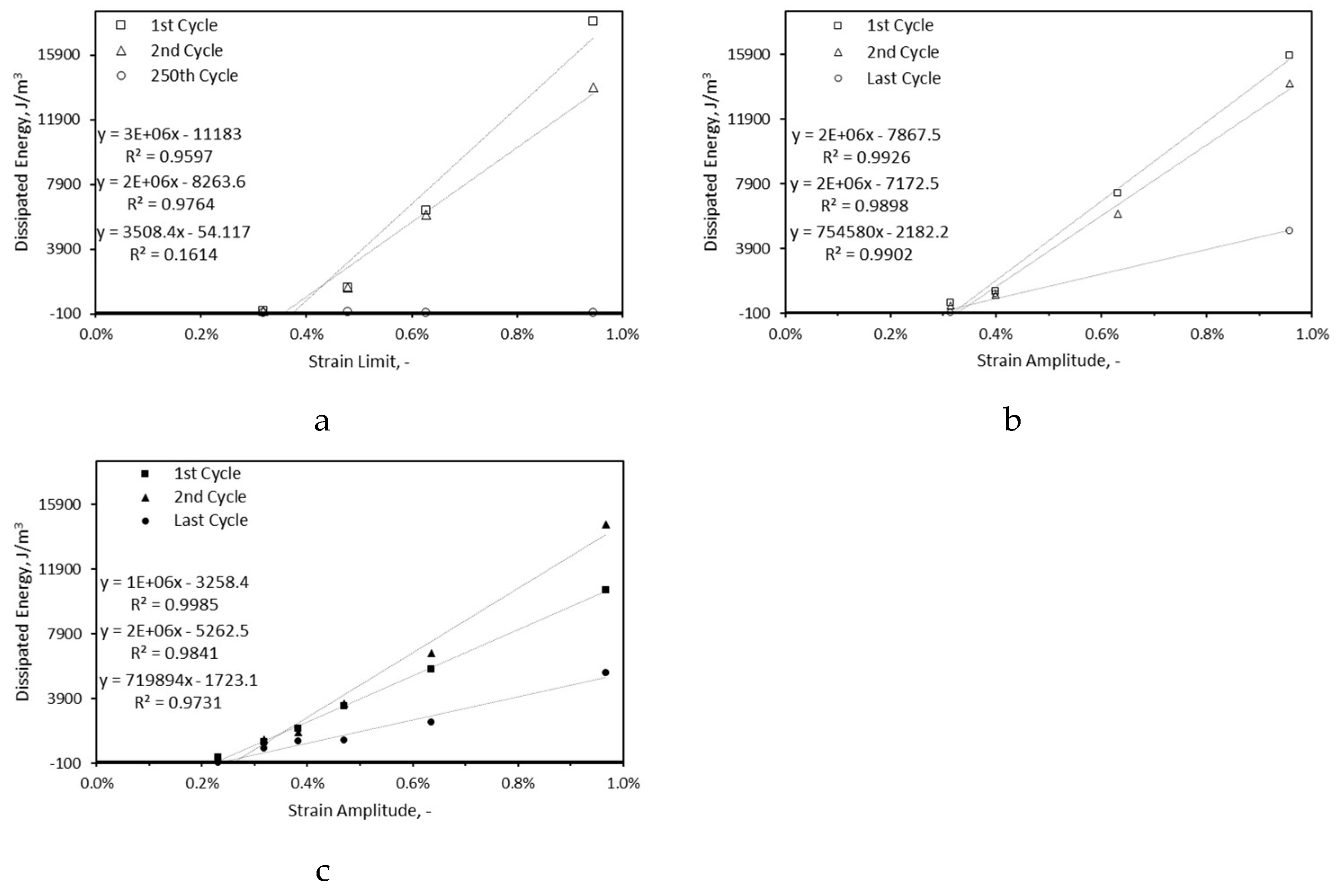

Figure 11 and

Figure 12 show the evolution of dissipated energy in cyclic tests of method II and method III, respectively. In all cyclic tests of method II, the trend is as follows: The dissipated energy starts with a relatively high magnitude, but abruptly drops to negative values after just a few cycles. Then the rate of decrease stagnates until the final cycle. Here the negative values of dissipated energy mean that the unloading curve had overlapped the loading one and no energy was dissipated. This observation is in line with the other damage indicators where damage was produced only during the first few cycles in cyclic tests of method II. The low intensity (strain amplitude) tests conducted in method III setup (

Figure 12-a) follow a similar trend as of the curves of the cyclic tests of method II (

Figure 11). Here again only during the first few cycles some energy (but to a much lower extent than medium and high strain limit tests of method II) is dissipated. Unlike the low intensity curves, medium (

Figure 12-b) and high (

Figure 12-c) strain amplitude curves of cyclic tests method III do not approach negative values. Even they are different in terms of profile shape. In medium intensity strain amplitude tests the initial decrease of dissipated energy is followed by an increasing trend before decreasing again up to failure. The curve has a s-shape in the case of the sample of IFB 28 which was cycled at strain amplitude of 0.4%. In case of IFB 26 materials, the magnitude of dissipated energy initially increases, then decreases up to failure. The initial increase of dissipated energy can be attributed to the occurrence of strain hardening due to compaction in this material. However, such behaviour was not witnessed for the samples of IFB 28. The rate of decrease of dissipated energy increased with the increase of strain amplitude in both of the materials.

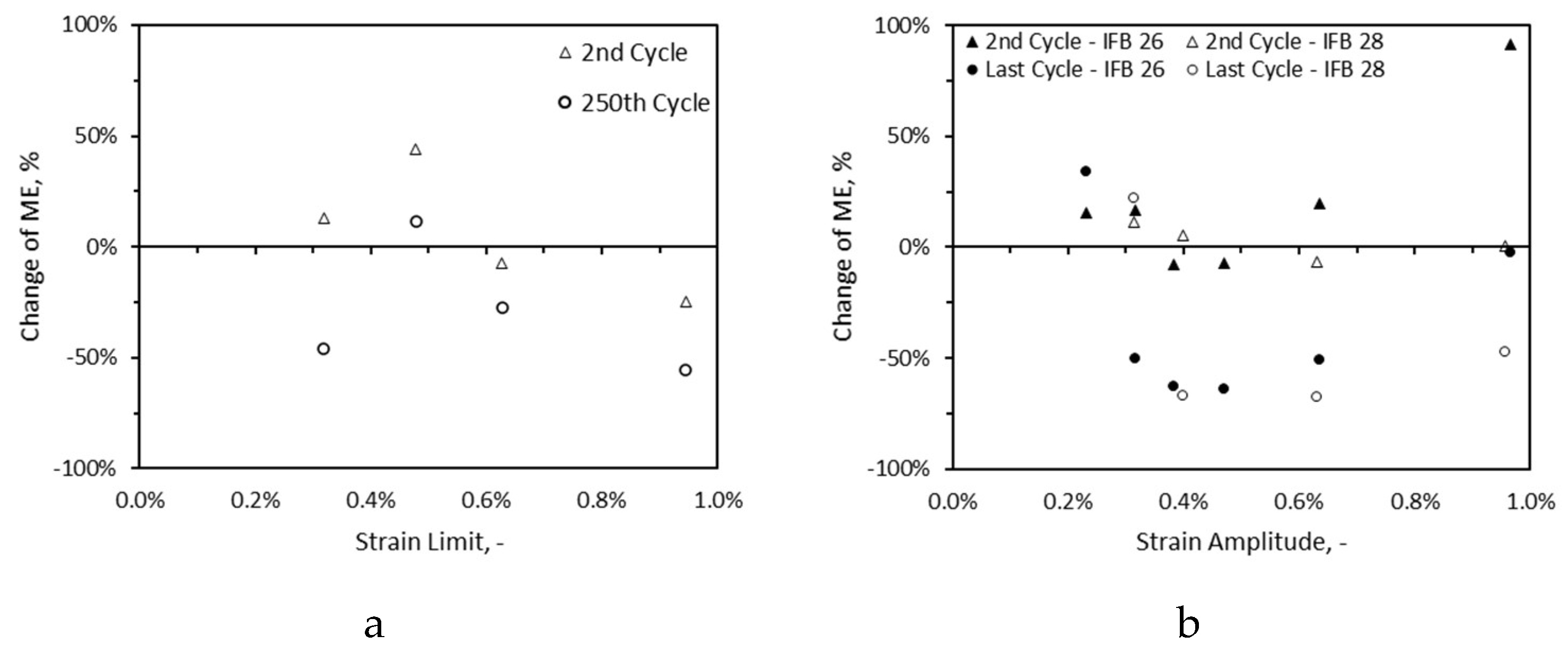

Figure 13 and

Figure 14 present changes of modulus of elasticity (ME) and upper limits stress (SIG) for the second and last cycles in comparison to the first cycle for all cyclic measurements, respectively. For the measurements performed at the strain amplitude of 0.23%, 0.31% as they were below the SNLP of their respective material, the values of the SIG and ME for both the second and last cycles are all positive, except for method II in which the ME of last cycle for the sample cycled at 0.32% is negative. In case of method III, these samples experienced stiffening through the cycles without loss of stress capacity. For the same strain limit, 0.32%, the sample lost its stiffness by -46%. For all samples cycled at strain amplitude/limit above their respective SNLP, the values of SIG and ME of last cycles lie in the negative range. This is in line with the fact that the samples went through degradation. In case of IFB 28 a similar trend applies to the second cycles, but this is not the case for IFB 26. It can be seen that black triangles are all positive irrespective of the applied strain amplitude (

Figure 14-b). This implies IFB 26 in method III went through strain hardening, even though the first cycle could have well-passed the material’s SNLP limit.

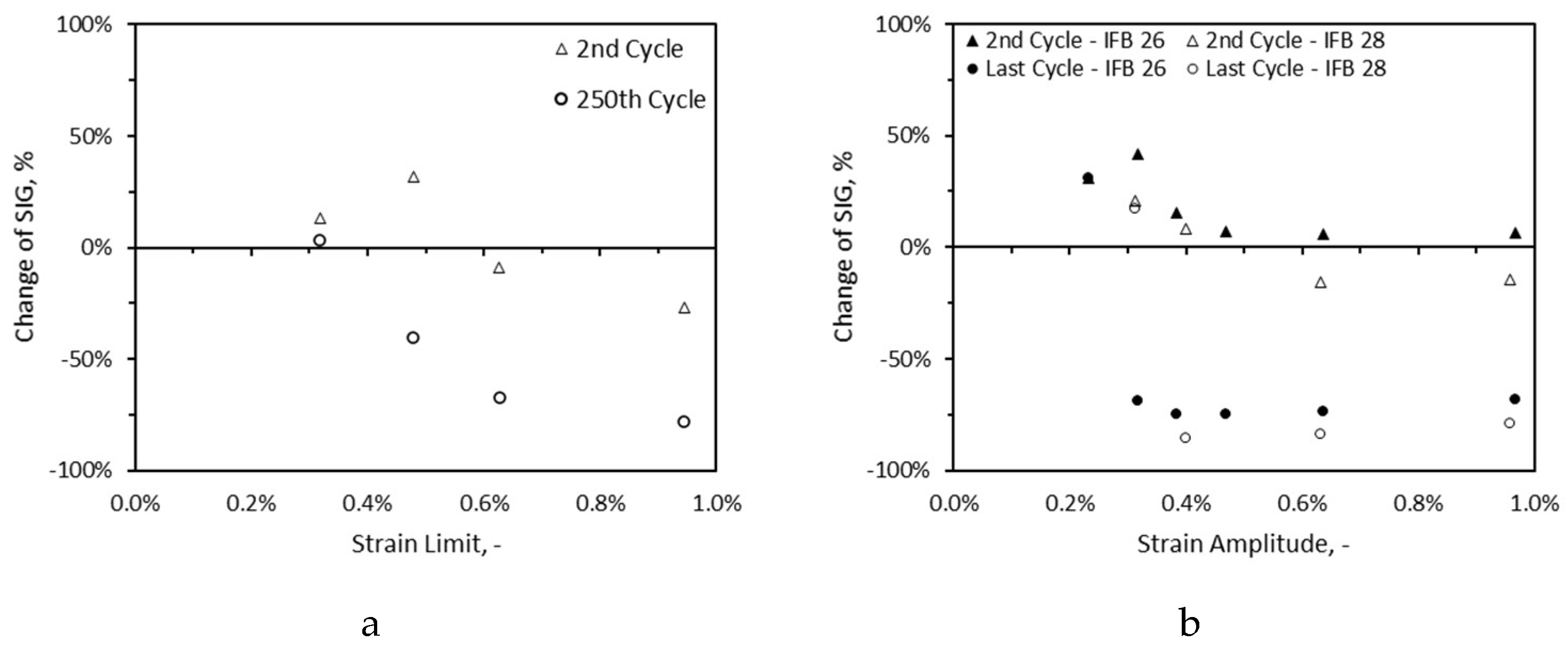

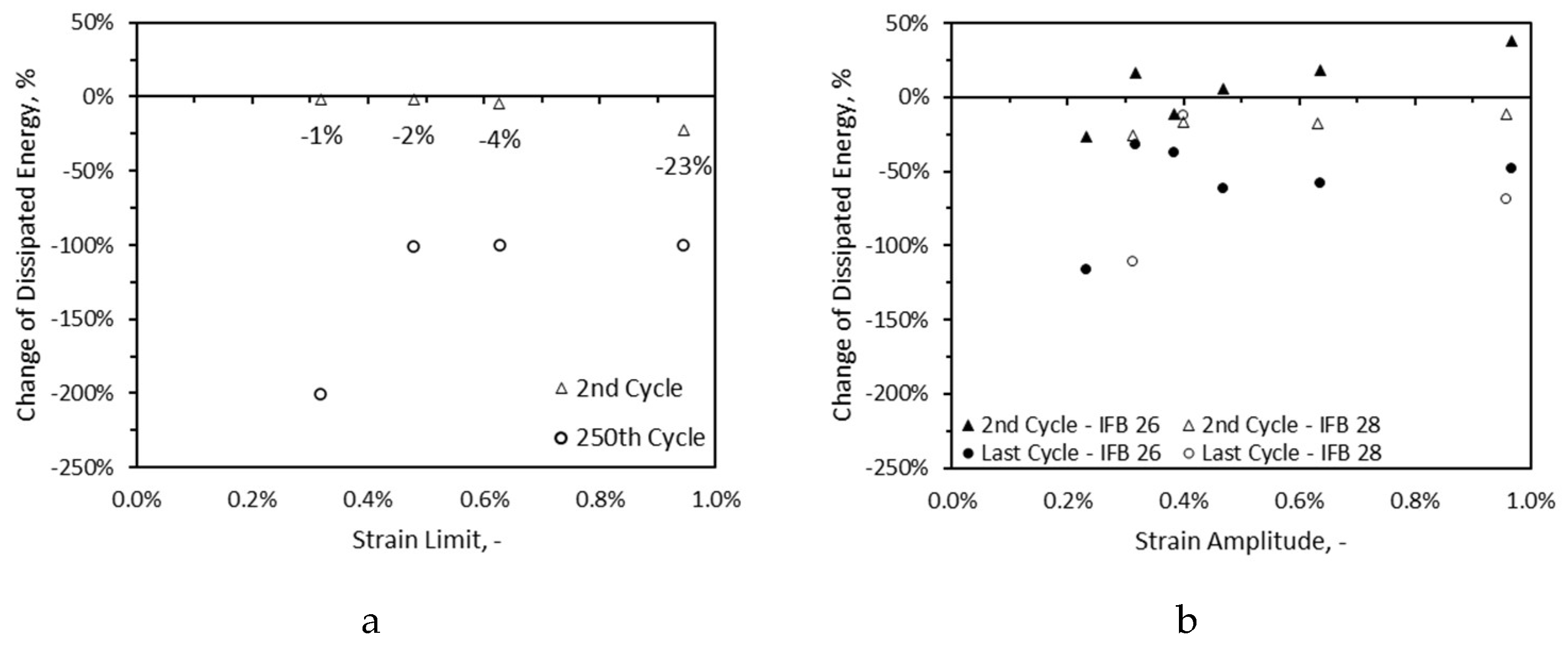

The change of dissipated energy in the second and last cycles in comparison to the first cycle of the cyclic tests of method II and method III are depicted in

Figure 15-a and

Figure 15-b, respectively. In case of no failure samples, the dissipated energy of the last cycle is lower by 100%-200% than the first cycle’s dissipated energy. For samples cycled with strain amplitudes in the range of SNLP of the materials the difference of dissipated energy between the first and last cycle becomes minimal. In IFB 26 sample which was cycled at the strain amplitude of 0.32%, the difference is only -32%. In IFB 28 sample which was cycled at the strain amplitude of 0.4%, the difference of dissipated energy of the last and first cycle is only -13%. For higher strain amplitudes the difference becomes in the range of 48%-68%. In IFB 26 samples, the dissipated energy in the most of the cases was higher in the second cycles than the first cycles. As mentioned earlier, possibly the strain hardening due to the compaction of the material explains such behaviour.

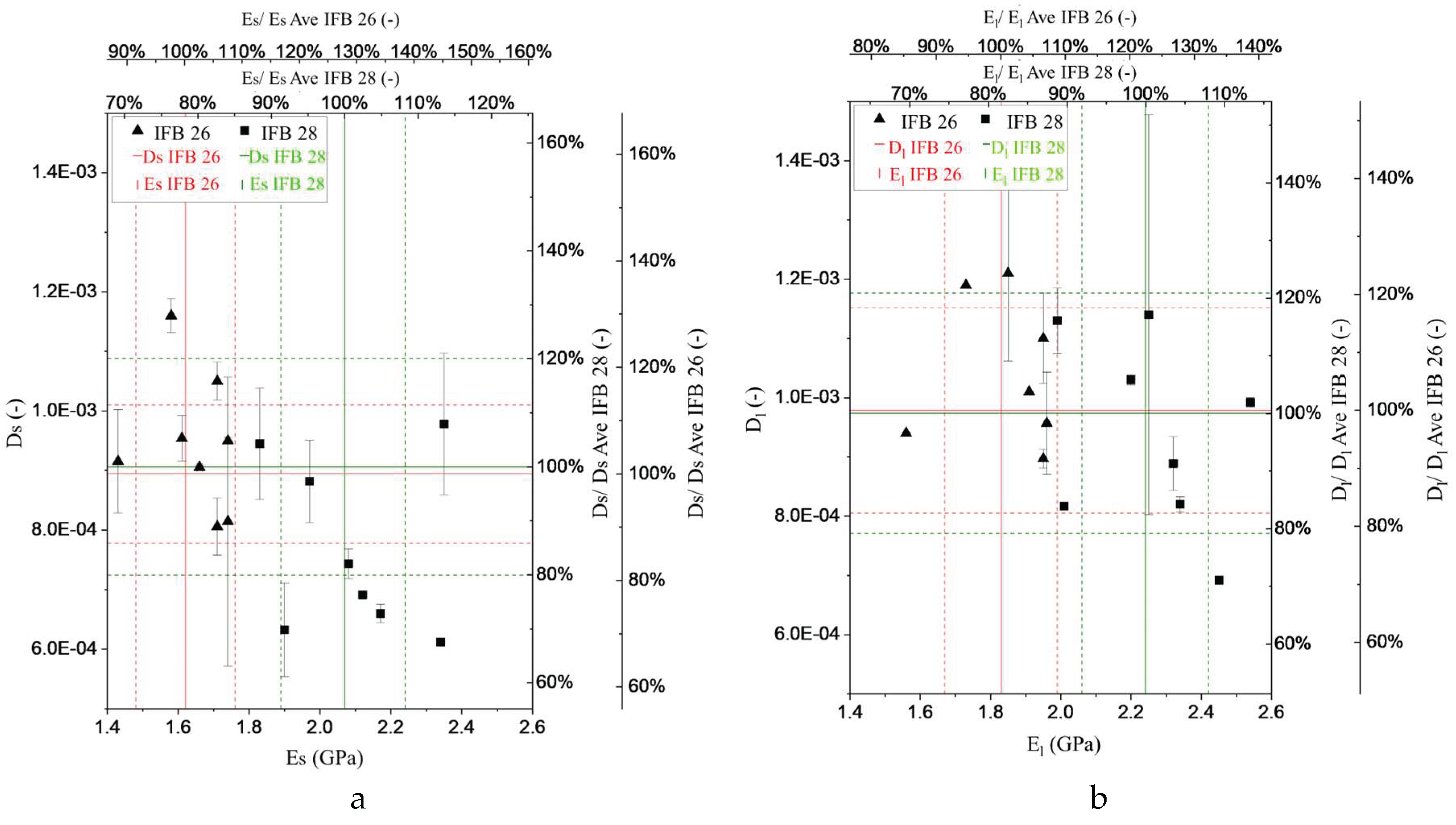

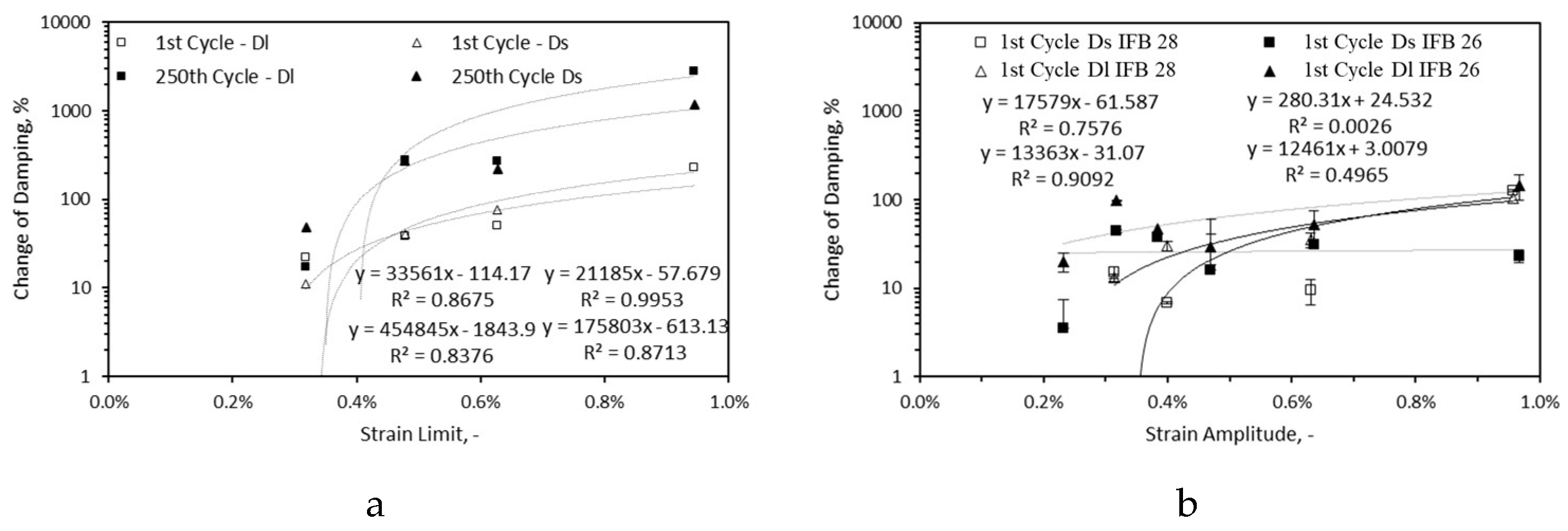

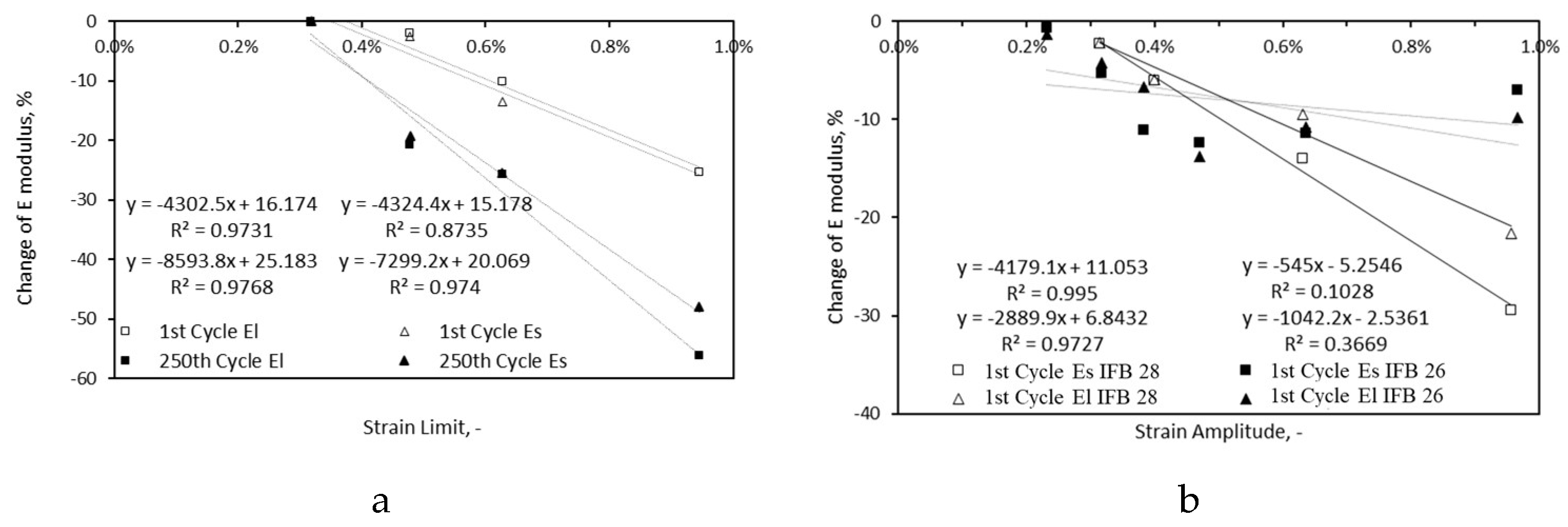

Figure 16 and

Figure 17 present the changes of damping and dynamic Young’s modulus of samples after the first and 250th (last) cycles in comparison to their original state, respectively. Two directions, the low thickness (s) and high thickness (l) were employed to address precisely the damage on the sides of the samples. As it can be seen from the figures, the general trend is with the increase in extent of damage, damping values (logarithmic scale) increase, while the dynamic Young’s modulus decreases. The magnitude of changes in damping are much higher than dynamic Young’s modulus. For the sample cycled at the strain limit of 0.97%, after 250 cycles E

l corresponds to -56.2% while D

l shows 2831%. Damping seems to be the more sensitive damage indicator than the dynamic Young’s modulus. For the sample cycles at 0.32% strain limit, neither dynamic Young’s modulus nor irreversible strain (

Figure 18) indicate any development of damage, but damping parameters after 250 cycles are 11% (D

s), 22% (D

l). The magnitude of changes of dynamic Young’s modulus is similar for IFB 28 samples after the first cycle where strain amplitude and limit were similar, however the damping differs significantly. The higher scatter in damping data after the first cycles requires more datapoints to obtain a more reasonable data fit. For low and medium intensity strain amplitudes, both damping and dynamic Young’s modulus show higher extent of damage (changes) in IFB 26 than IFB 28 after the first cycle, but for high intensity strain amplitudes data is not consistent. In IFB 26, with the increase of strain amplitude not necessarily the changes of dynamic Young’s modulus and damping increases, the low value of goodness of linear fit for this material, unlike IFB 28 can be noted from

Figure 17 and

Figure 16.

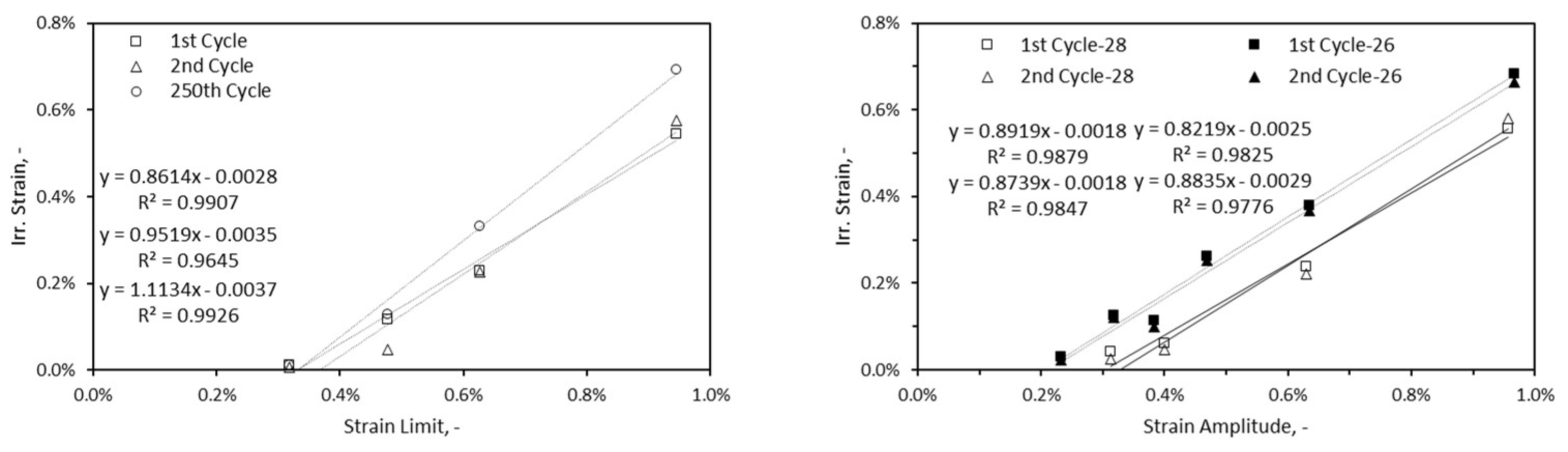

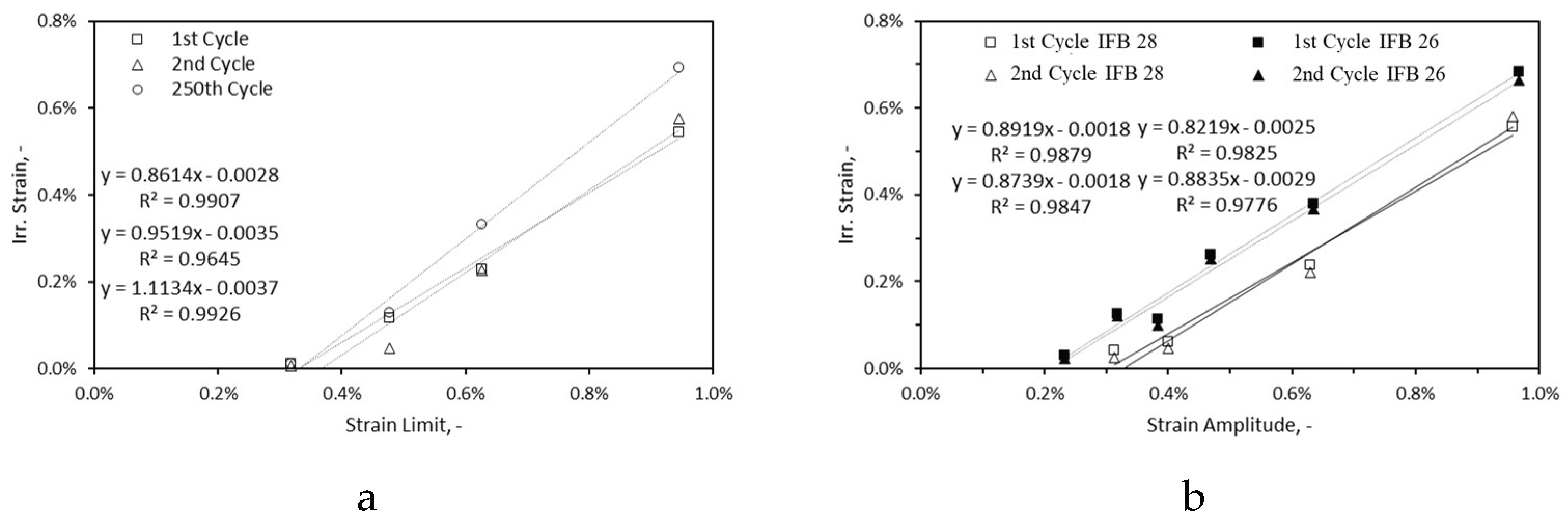

The data of all samples after the first and 250

th cycles was linearly fitted, the equation and the goodness of fit are shown. In case of irreversible strain, as the data for the second cycle was also available, the same was done. The goodness of fit for damping curves is slightly lower which can be attributed to the sensitivity of the method. The irreversible strain developed with respect to strain amplitude/limit is depicted in

Figure 18 for the first, second and last cycle (method II only). As it can be seen, with the increase of strain amplitude/limit, the developed irreversible strain increases. For IFB 28 samples cycled at strain amplitude/limit of 0.3% almost no irreversible strain was developed as the amplitude/limit was below the materials respective SNLP limit. The further the amplitude/limit gets from SNLP limits, greater irreversible strain is developed. Interestingly the amount of irreversible strain developed by the samples cycled at the same strain amplitude/limit in method II and method III are similar. The samples cycled at the strain amplitude/limit of 0.63% and 0.96% in method II and method III develop around 0.23% and 0.55% irreversible strain, respectively. This is due to the fact that the only similarity in terms of cycle setup method II and method III share is the first cycle and the consecutive cycles follow different paths. For low and medium intensity strain limits, the irreversible strain produced after the last cycle is in the range of the second cycle. For high intensity strain limits, the amount of irreversible strain produced after the last cycle is by 20%-45% greater than the irreversible strain recorded after the second cycle, which is a very small development in comparison to irreversible strain developed after the last cycle in method III. From Figure 22 It can be also inferred for similar strain amplitudes IFB 26 samples developed a greater amount of irreversible strain than IFB 28 after the first cycle. At strain amplitude of 0.3% IFB 28 developed only 0.04% irreversible strain whereas IFB 26 sample developed 0.12% irreversible strain.

For the prediction of damage trend in the last cycle of the cyclic tests of method III, dissipated energy was the only feasible parameter. Irreversible strain was not helpful since the total strain of 10% was assumed as the failure criteria for cyclic tests of method III. Measurements of dynamic Young’s modulus and damping property were not possible due to the sever extent of damage (failure of samples).

Figure 19 shows the energy dissipated by sample after the first, second and last cycles of cyclic tests. For similar strain limits and amplitudes, the magnitude of dissipated energy is close for the first and second cycles but quite different for the last cycle. The samples cycled at the strain limit of 0.94% and strain amplitude of 0.96% dissipated around 1700 J/m

3 and 1400 J/m

3 energy during the first and second cycles, but during the last cycle the former and latter dissipated -30 J/m

3 and 5000 J/m

3, respectively. Summing up the amount of dissipated energy during the first and second cycle, it can be noted in low and medium intensity strain amplitudes, IFB26 dissipated greater amount of energy than IFB 28 but in case of high intensity strain amplitudes the values become close and even greater for IFB 28.

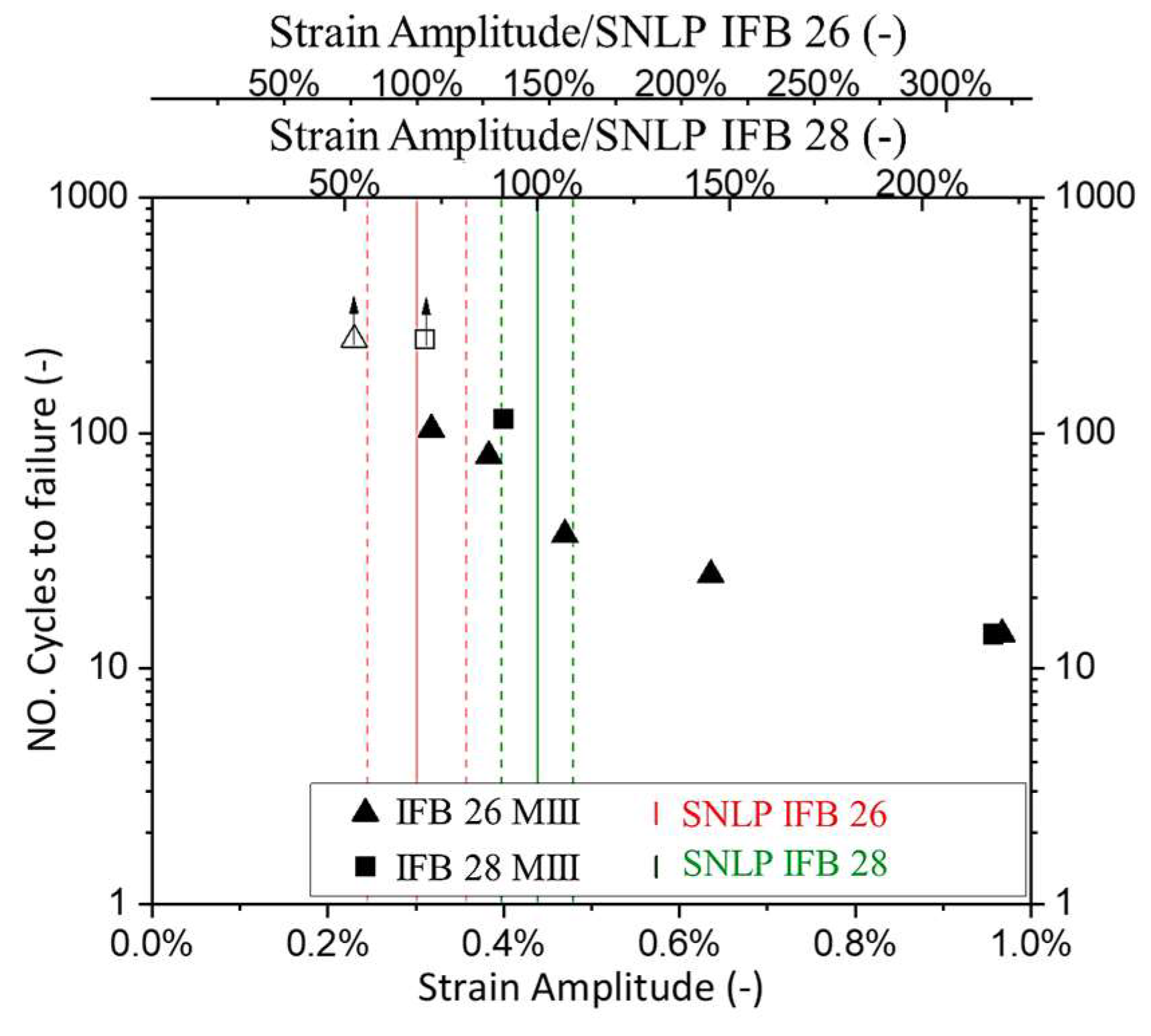

The strain of proportional limit (SNLP) obtained from monotonic loading tests was found to define the potential for failure of the samples in cyclic tests of method III. For the studied materials, especially in case of IFB 26 strain at maximal stress was found unsatisfactory for this purpose. The cyclic tests conducted with strain amplitude below SNLP of the material did not result in failure (

Figure 20). The cyclic tests with strain amplitude greater than the defined SNLP of the materials ended with the failure of the sample. For this, IFB 28 shows sensitivity to damage formation at higher strains than IFB 26. The greater the strain amplitude the lower the number of cycles the sample sustained before failure. Method III permits build-up of damage, enables comparison of the degradation process in the materials.

Method II represents the constrained thermal expansion occurring in service. For this, in practice as long as the loads (thermal strains) are within the elastic limits of the IFBs, no degradation occurs. By increase of the load magnitude over the elastic limits, compaction of the IFBs occur. This may initially lead to some relaxation as the degradation process stagnates with no major crack formation. In the framework of the current study, however none of the samples tested in the cyclic method II setup failed. None of the damage indicators showed the third phase of fatigue for the cyclic tests of method II, even though the strain limit in case of high intensity tests was well above the defined SNLP of the material. Similar to the tests of repetitive thermal cycles [

35], damage tended to stagnate in the cyclic test of method II for the number of cycles investigated in this study. Potentially for a higher number of cycles in tests of high intensities failure may occur.