The Necessity of Spinal Erector Training for Spinal Health

Spinal pain and dysfunction are widespread issues affecting individuals across all demographics, with estimates suggesting that approximately 80% of adults experience some form of spinal discomfort during their lives (Deyo & Weinstein, 2001). It is one of the leading causes of disability worldwide, significantly impacting work productivity and quality of life (Hartvigsen et al., 2018). Despite its prevalence, a common misconception persists in both medical and fitness communities—that bending the spine and directly training the spinal erectors increases the risk of injury. This belief has led to widespread avoidance of spinal flexion and minimal emphasis on strengthening the muscles responsible for supporting and controlling spinal movement.

Recent research suggests that undertraining the spinal erectors may be a contributing factor to chronic pain and dysfunction rather than a preventive measure. Studies indicate that a lack of strength and endurance in the spinal extensors correlates with an increased risk of developing spinal pain (Steele et al., 2015). Additionally, biomechanical analyses demonstrate that controlled spinal flexion, rather than being inherently dangerous, plays a crucial role in maintaining mobility and distributing forces across the spine effectively (McGill, 2015). Avoiding flexion altogether may lead to compensatory movement patterns, resulting in muscle imbalances and greater susceptibility to injury.

This paper aims to challenge the prevailing notion that spinal flexion should be avoided and argues for a structured approach to training the spinal erectors for both strength and resilience. By examining the role of key exercises—such as seated good mornings, weighted toe touches, cable toe touches, cable back extensions, and traditional back extensions—this discussion will highlight how proper training can not only reduce the risk of injury but also enhance functional movement. Additionally, this paper will explore the principles of progressive overload, recovery strategies, and the importance of mobility in ensuring long-term spinal health. Through a reevaluation of traditional perspectives, this work advocates for a paradigm shift in how the spinal erectors are trained and perceived in both fitness and rehabilitation settings.

The Myth of Avoiding Spinal Erector Training

For decades, conventional wisdom in rehabilitation and strength training has cautioned against spinal flexion and direct spinal erector training, often portraying these movements as inherently dangerous and a leading cause of spinal injury. This belief is deeply ingrained in physical therapy, fitness coaching, and general health recommendations, where individuals are frequently advised to “keep a neutral spine” and avoid rounding the back during movement. However, recent biomechanical research suggests that avoiding spinal flexion and failing to strengthen the spinal erectors may actually contribute to chronic pain and dysfunction rather than prevent it.

One of the primary arguments against spinal flexion is the concern over intervertebral disc herniation. Studies by Callaghan and McGill (2001) suggest that repeated, excessive flexion—particularly under high compressive loads—can contribute to disc degeneration over time. While this finding has been widely cited as evidence to avoid spinal flexion altogether, it does not account for the context of controlled and progressive training. More recent analyses emphasize that the spine is an adaptable structure, capable of strengthening and responding positively to appropriate loading patterns (Radebold et al., 2001). Just as with any other muscle group, the spinal erectors require progressive overload and exposure to varying degrees of movement to develop strength and resilience.

Avoiding spinal flexion entirely can lead to increased stiffness and reliance on passive structures such as ligaments for stability, rather than engaging the erector spinae and deep spinal stabilizers. Research by Steele et al. (2015) found that individuals with chronic spinal pain often exhibit deconditioned spinal extensors, which directly correlates with pain severity. Without sufficient loading and movement, these muscles remain weak, and the spine becomes more susceptible to injury during everyday activities. Additionally, studies have shown that when individuals avoid flexion-based movements, they often compensate by overloading the hips or upper back, increasing the risk of injury elsewhere (Van Dieën et al., 1999).

The fear of spinal flexion also stems from misinterpretations of spinal biomechanics. While extreme or uncontrolled flexion under heavy loads can be problematic, controlled flexion exercises—when properly programmed—can enhance mobility, improve strength, and reduce the likelihood of injury (Schoenfeld et al., 2021). Furthermore, spinal flexion is a natural movement that occurs in everyday activities, such as tying shoes or picking up objects from the ground. Training this movement in a controlled environment can improve an individual’s capacity to handle these real-world demands safely and efficiently.

By continuing to demonize spinal flexion and avoiding direct spinal erector training, individuals may be setting themselves up for greater injury risk rather than protecting their spines. Instead, a more balanced approach—one that incorporates both flexion and extension training—should be adopted to strengthen the spinal erectors, improve mobility, and reduce the prevalence of chronic pain. The next section will explore specific exercises that can safely and effectively develop the spinal erectors, challenging outdated beliefs and encouraging a more progressive approach to spinal health.

The Importance of Spinal Erector Training

The spinal erectors play a critical role in overall musculoskeletal function, serving as central stabilizers for movement, posture, and force transfer. Despite their importance, these muscles are often neglected in traditional fitness programs, contributing to widespread issues of weakness, instability, and pain. Research indicates that strengthening the spinal erectors can significantly reduce the prevalence of chronic pain and improve functional capacity (Steele et al., 2015). Furthermore, avoiding direct training of the spinal erectors may lead to compensatory movement patterns that increase the risk of injury in other regions, such as the hips and thoracic spine (Van Dieën et al., 1999).

The spinal erectors function as a structural foundation, providing support for both the upper and lower body. During fundamental movements such as squatting, lifting, and bending, the spinal erectors play a crucial role in force distribution and spinal alignment (McGill, 2015). Weakness in these muscles can compromise movement efficiency, leading to excessive strain on passive structures such as intervertebral discs and ligaments. Studies have demonstrated that individuals with stronger spinal extensors exhibit improved stability and reduced pain-related disability (Steele et al., 2015). A well-conditioned spinal erector complex also enhances athletic performance by facilitating greater power transfer between the upper and lower extremities. Sports that require explosive movements, such as sprinting and weightlifting, depend on a strong and stable core to optimize force production (Comfort et al., 2011). Without adequate spinal erector strength, athletes may experience performance deficits and increased susceptibility to injuries such as hamstring strains and pelvic misalignment.

One of the most significant consequences of undertraining the spinal erectors is an increased risk of chronic pain. Epidemiological studies have identified spinal pain as one of the leading causes of disability worldwide, often linked to poor muscular endurance and deconditioning (Hartvigsen et al., 2018). A sedentary lifestyle, combined with a lack of targeted spinal erector training, contributes to muscular atrophy and reduced spinal support. Without sufficient strength in the erector spinae and deep spinal stabilizers, individuals become more reliant on passive tissues, increasing the likelihood of disc degeneration and vertebral instability (Radebold et al., 2001). Additionally, insufficient spinal erector training can impair movement patterns in daily activities. Tasks such as lifting objects from the ground or maintaining an upright posture for extended periods require active engagement of the spinal musculature. Weakness in this area often results in compensatory strategies, such as excessive reliance on the hip extensors or an exaggerated anterior pelvic tilt, both of which can contribute to secondary musculoskeletal issues (Van Dieën et al., 1999).

As with any muscle group, the spinal erectors require progressive overload to develop strength and resilience. Controlled exposure to increased resistance and movement complexity allows the tissues to adapt and strengthen over time. Research supports the use of resistance training for improving spinal function, with exercises such as back extensions and good mornings demonstrating significant efficacy in enhancing spinal extensor endurance (Schoenfeld et al., 2021). Implementing a structured training program that includes both extension and flexion-based movements can lead to measurable improvements in both strength and pain reduction. Furthermore, integrating controlled spinal flexion into training—contrary to traditional avoidance strategies—may enhance spinal mobility and mitigate stiffness-related discomfort.

The undertraining of the spinal erectors is a critical factor contributing to chronic pain and dysfunction. Strengthening this region improves stability, reduces injury risk, and enhances overall movement efficiency. A well-structured training approach that incorporates progressive overload, targeted spinal erector exercises, and controlled spinal flexion can significantly improve spinal health and functional performance. The next section will explore specific exercises that effectively develop the spinal erectors, providing practical applications for both rehabilitation and strength training contexts.

Exercises for Spinal Erector Training

Strengthening the spinal erectors requires a structured approach that balances both extension and flexion-based movements. While many traditional programs emphasize core stability and avoid direct spinal loading, research indicates that targeted exercises for the spinal erectors can significantly enhance muscular endurance, reduce pain, and improve movement efficiency (Steele et al., 2015). The spinal extensors, including the erector spinae and multifidus, play a crucial role in maintaining spinal stability and force distribution during functional movements (Bergmark, 1989). Properly training these muscles not only reduces injury risk but also enhances overall athletic performance and daily movement capacity.

A well-rounded spinal erector training program should incorporate a combination of extension-based movements, such as back extensions and cable back extensions, and flexion-based movements, such as controlled toe touches and seated good mornings. While conventional wisdom has often discouraged spinal flexion under load, recent biomechanical studies suggest that controlled spinal flexion can improve resilience and adaptability in the spinal erectors (McGill, 2015). By progressively exposing the spine to varying degrees of motion and resistance, individuals can develop both strength and mobility, reducing the likelihood of chronic pain and injury (Schoenfeld et al., 2021).

Beyond just strengthening the spinal erectors, these exercises also contribute to improved posture, greater functional capacity, and better load tolerance. Movements like seated good mornings and toe touches reinforce hip and spinal coordination, enhancing flexibility and neuromuscular control. Cable variations, such as cable back extensions and cable toe touches, allow for constant tension throughout the movement, offering a unique stimulus for spinal development. By incorporating these exercises into a well-structured training plan, individuals can address weaknesses, enhance spinal stability, and ultimately promote long-term spinal health.

The following sections will provide an in-depth analysis of specific exercises, detailing their proper execution, biomechanical benefits, and potential progressions for different skill levels. Each exercise will be examined in the context of strengthening the spinal erectors while maintaining safety and efficiency in movement.

Back Extensions

Back extensions are a foundational exercise for strengthening the spinal erectors, primarily targeting the erector spinae, gluteus maximus, and hamstrings. This movement is typically performed on a Roman chair (hyperextension bench), which allows for controlled spinal extension while maintaining proper hip positioning. Research suggests that back extensions are highly effective for improving spinal extensor endurance and reducing the risk of chronic spinal pain (Steele et al., 2015). Furthermore, progressive loading through external resistance, such as holding a weight plate or dumbbell, can enhance muscle activation and strength adaptations (McGill, 2015).

To perform a back extension, an individual should begin by positioning themselves on a Roman chair with the hip crease aligned with the edge of the pad, ensuring that the torso can move freely. The feet should be secured under the foot rollers to maintain stability. Depending on the difficulty level, the arms can be crossed over the chest, the hands can be placed behind the head, or a weight can be held against the chest. The movement begins with the lowering phase, where the individual hinges at the hips and lowers the torso toward the floor in a controlled manner while maintaining a neutral spine. This controlled descent ensures engagement of the spinal erectors and hamstring muscles without unnecessary strain. The lifting phase involves engaging the spinal erectors, glutes, and hamstrings to extend the torso back to the starting position. It is crucial to avoid excessive hyperextension at the top, ensuring that the body returns to a neutral position where a straight line is maintained. Controlled breathing should be emphasized, with an exhale during the ascent and an inhale during the descent.

Several progressions and variations can be implemented to adjust the difficulty of back extensions. Weighted back extensions involve holding a dumbbell or plate against the chest, increasing resistance and muscular engagement. Paused back extensions incorporate a two- to three-second pause at the top of the movement, emphasizing time under tension to improve endurance and strength. Banded back extensions can also be performed by attaching a resistance band for variable resistance, which increases difficulty as the movement progresses. These variations allow for progressive overload, a key principle in strength training that facilitates continual muscular adaptation (Schoenfeld et al., 2021).

The biomechanical benefits of back extensions are extensive, as they reinforce spinal stability and enhance posterior chain strength, both of which are essential for functional movements such as deadlifts, squats, and sprinting. Research indicates that individuals with greater spinal extensor endurance experience significantly lower incidences of chronic back pain, emphasizing the importance of training these muscles (Steele et al., 2015). Additionally, strengthening the eccentric phase of back extensions can improve tissue resilience and reduce injury risk, further supporting their inclusion in a comprehensive strength program (Schoenfeld et al., 2021). By incorporating back extensions into a well-rounded training regimen, individuals can improve spinal erector strength, enhance posture, and develop greater spinal resilience. The next section will explore cable back extensions, a variation that provides constant tension throughout the movement.

Figure 1.

Position 1 of the back extension.

Figure 1.

Position 1 of the back extension.

Figure 2.

Position 2 of the back extension.

Figure 2.

Position 2 of the back extension.

Cable Back Extensions

Cable back extensions provide a unique variation of traditional back extensions by utilizing constant tension from a cable machine. Unlike conventional back extensions performed on a Roman chair, this movement is executed using a lat row cable machine, allowing for controlled spinal flexion and extension under load. The primary muscles targeted include the erector spinae, gluteus maximus, and hamstrings, with additional engagement of the latissimus dorsi due to the cable resistance. Research suggests that cable-based exercises can enhance muscular activation by maintaining consistent tension throughout the movement, leading to improved strength adaptations and endurance (McGill, 2015).

To perform the cable back extension, an individual should begin by positioning themselves in front of a lat row cable machine and setting the cable at the lowest attachment point. A straight bar or rope attachment should be used, and the individual should grasp the handle with both hands, keeping the arms fully extended throughout the movement. The starting position requires a neutral spine, a slight knee bend, and the feet placed shoulder-width apart for stability. The movement begins with the lowering phase, where the individual bends forward at the hips, allowing the torso to descend while maintaining straight arms. The goal is to achieve as much controlled spinal flexion as possible without compromising form.

The lifting phase involves engaging the spinal erectors, glutes, and hamstrings to return to the starting position. The focus should be on actively contracting the spinal extensors while maintaining a smooth, controlled movement. Unlike traditional back extensions, where the hips serve as the primary pivot point, cable back extensions emphasize spinal articulation, requiring more engagement from the erector spinae. Controlled breathing should be incorporated, with an inhale during the descent and an exhale during the ascent to optimize stability and muscle activation.

Several modifications can be implemented to adjust difficulty and muscular engagement. Increased resistance can be applied by progressively adding weight to the cable stack, ensuring that overload is applied gradually to avoid excessive strain. Paused repetitions, where a two- to three-second hold is added at the top of the movement, can enhance endurance and muscle activation. Feet-elevated variations can also be introduced, where the individual places their feet on a platform to increase the range of motion and further challenge spinal mobility and strength.

Cable back extensions offer several advantages over their bodyweight counterpart. The continuous tension provided by the cable machine eliminates the resting phase at the top of the movement, keeping the spinal erectors under constant engagement. Additionally, research indicates that incorporating spinal flexion and extension under controlled conditions can enhance tissue resilience and reduce stiffness-related discomfort (Schoenfeld et al., 2021). Unlike free-weight exercises, cable-based movements allow for precise load adjustments, making them suitable for individuals recovering from injury or looking to gradually strengthen their spinal erectors without excessive compression forces.

By integrating cable back extensions into a structured training program, individuals can develop greater spinal endurance, improve spinal mobility, and enhance overall posterior chain strength. This movement serves as an effective alternative or complement to traditional back extensions, offering variable resistance and a greater range of motion. The next section will cover seated good mornings, another essential exercise for spinal erector development.

Figure 3.

Position 1 of the cable back extension.

Figure 3.

Position 1 of the cable back extension.

Figure 4.

Position 2 of the cable back extension.

Figure 4.

Position 2 of the cable back extension.

Seated Good Mornings

Seated good mornings are a highly effective exercise for strengthening the spinal erectors, specifically targeting the erector spinae while also engaging the glutes and hamstrings. Unlike traditional good mornings performed in a standing position, the seated variation isolates the movement to the lumbar and thoracic spine by removing the contribution of the lower body. This allows for a greater focus on controlled spinal flexion and extension, a key component of improving spinal erector strength and mobility. Contrary to common practice in many resistance exercises, the goal of seated good mornings is not to maintain a rigid spine but rather to deliberately bend the back throughout the movement. Encouraging spinal flexion under load helps strengthen the spinal musculature in positions it naturally encounters in daily life and athletic movements, reducing the risk of injury while improving overall resilience.

There are two primary variations of the seated good morning: one performed with a dumbbell held in a palm grip and the other with a barbell placed on the upper back. In the dumbbell variation, the individual begins in an upright seated position on a flat bench, holding a dumbbell at chest level with both hands. The spine starts in a neutral position, with the feet firmly planted on the ground for stability. The individual then initiates the movement by bending forward at the waist, allowing the spine to flex naturally while maintaining control over the descent. As the torso moves downward, the weight of the dumbbell provides resistance against the spinal extensors, encouraging active engagement of the spinal erectors. In the bottom position, the spine is fully flexed, and the individual then reverses the motion by extending the back, engaging the spinal musculature to return to the upright position.

The barbell variation follows a similar movement pattern but with the barbell resting on the upper traps rather than being held in the hands. The starting position involves a neutral spine with the barbell placed securely across the back. The movement begins with a forward bend, allowing the spine to round naturally as the torso moves toward the thighs. This flexion increases the stretch and engagement of the erector spinae, placing a controlled load on the spinal musculature. The bottom position represents the deepest point of flexion before the individual contracts the spinal erectors and drives the torso back to the starting position. The barbell variation generally allows for greater loading than the dumbbell version, making it ideal for individuals seeking progressive overload.

Progressions and modifications for seated good mornings include adjusting the range of motion, increasing resistance, and incorporating paused repetitions to enhance time under tension. For beginners, starting with a lighter dumbbell or an unloaded barbell can help develop technique and confidence in the movement. More advanced lifters may benefit from adding resistance, using a slower eccentric phase to increase muscular engagement, or incorporating brief pauses at the bottom position to further challenge the spinal erectors. Elevating the feet on a platform can also slightly change the angle of the movement, increasing the demand on the spinal musculature.

Seated good mornings offer several advantages over other spinal erector exercises, particularly in their ability to strengthen the spine through its full range of motion. Unlike many conventional back exercises that emphasize maintaining a straight spine, this movement deliberately trains the spine to handle controlled flexion and extension under load. Research supports the idea that exposure to progressive spinal flexion in a controlled setting can enhance tissue resilience and reduce injury susceptibility over time (McGill, 2015). Additionally, by removing the contribution of the lower body, seated good mornings create an isolated training stimulus for the erector spinae, leading to greater strength and endurance improvements in the spinal region.

Incorporating seated good mornings into a structured training program can provide significant benefits for individuals looking to improve spinal erector strength, mobility, and durability. Whether using a dumbbell or barbell, this movement reinforces proper spinal mechanics and prepares the back for real-world demands that require bending and lifting under load. The next section will cover toe touches, another essential exercise for training the spinal erectors through a full range of motion.

Figure 5.

Position 1 of the dumbbell seated good morning.

Figure 5.

Position 1 of the dumbbell seated good morning.

Figure 6.

Position 2 of the dumbbell seated good morning.

Figure 6.

Position 2 of the dumbbell seated good morning.

Figure 7.

Position 1 of the barbell seated good morning.

Figure 7.

Position 1 of the barbell seated good morning.

Figure 8.

Position 2 of the barbell seated good morning.

Figure 8.

Position 2 of the barbell seated good morning.

Toe Touches

Toe touches are an effective exercise for strengthening the spinal erectors by emphasizing controlled spinal flexion and extension. This movement targets the erector spinae, glutes, and hamstrings while also improving flexibility and mobility in the posterior chain. Unlike traditional spinal erector exercises that focus primarily on extension, toe touches allow for a full range of motion, training the spine’s ability to bend and return to an upright position under load. Incorporating both dumbbell and cable variations provides different resistance profiles, with the cable version maintaining constant tension throughout the movement. Elevating the feet on a platform can also increase the difficulty by extending the range of motion, further challenging the spinal erectors.

The dumbbell variation begins in an upright stance, holding a dumbbell in each hand with a neutral spine and feet shoulder-width apart. The starting position maintains slight tension in the spinal erectors, with the arms extended naturally. The movement is initiated by bending forward at the waist, allowing the spine to flex fully as the dumbbells move toward the ground. The goal is to lower the weights as close to the floor as possible while maintaining control. At the bottom of the movement, the spine is maximally flexed, ensuring full engagement of the spinal erectors and hamstrings. The concentric phase involves contracting the erector spinae and glutes, pulling the torso back to the starting position in a smooth and controlled manner.

The cable variation follows a similar movement pattern but utilizes a low cable attachment, which increases resistance and ensures constant tension throughout the range of motion. The starting position requires the individual to stand upright while gripping the cable handle with both hands, maintaining straight arms. The descent mirrors the dumbbell version, with the individual bending forward and allowing the spine to flex completely as the cable handle moves toward the floor. At the bottom of the movement, the spine reaches its deepest point of flexion, ensuring that the spinal erectors are fully engaged. The return to the starting position is driven by an active contraction of the spinal erectors, bringing the torso back to an upright position while maintaining control.

Both variations of toe touches can be modified for progressive overload by increasing resistance, adding a pause at the bottom position, or elevating the feet on a platform to extend the range of motion. Elevating the feet forces the spinal erectors to work through a greater degree of flexion, making the movement more challenging and increasing muscular activation. Additionally, slowing down the eccentric phase (lowering portion) can improve control and enhance time under tension, leading to greater strength adaptations in the spinal musculature.

Biomechanically, toe touches offer a unique benefit by training spinal flexion under controlled resistance, which is often overlooked in traditional strength training programs. Research suggests that incorporating controlled spinal flexion movements can improve spinal resilience and reduce stiffness-related discomfort (McGill, 2015). Unlike static flexibility exercises, such as standing toe touches performed as a stretch, loaded toe touches require the active engagement of the spinal erectors, reinforcing their ability to generate force and stabilize the spine under load.

Toe touches serve as a highly effective tool for developing spinal erector strength, flexibility, and endurance, making them a valuable addition to any comprehensive training program. By training the spine through its full range of motion, these exercises prepare the spinal erectors for real-world movements that require bending, lifting, and stabilizing against external resistance. The next section will discuss the broader implications of spinal erector training and how incorporating these exercises can lead to long-term improvements in spinal health and injury prevention.

Figure 9.

Position 1 of the dumbbell toe touches.

Figure 9.

Position 1 of the dumbbell toe touches.

Figure 10.

Position 2 of the dumbbell toe touches.

Figure 10.

Position 2 of the dumbbell toe touches.

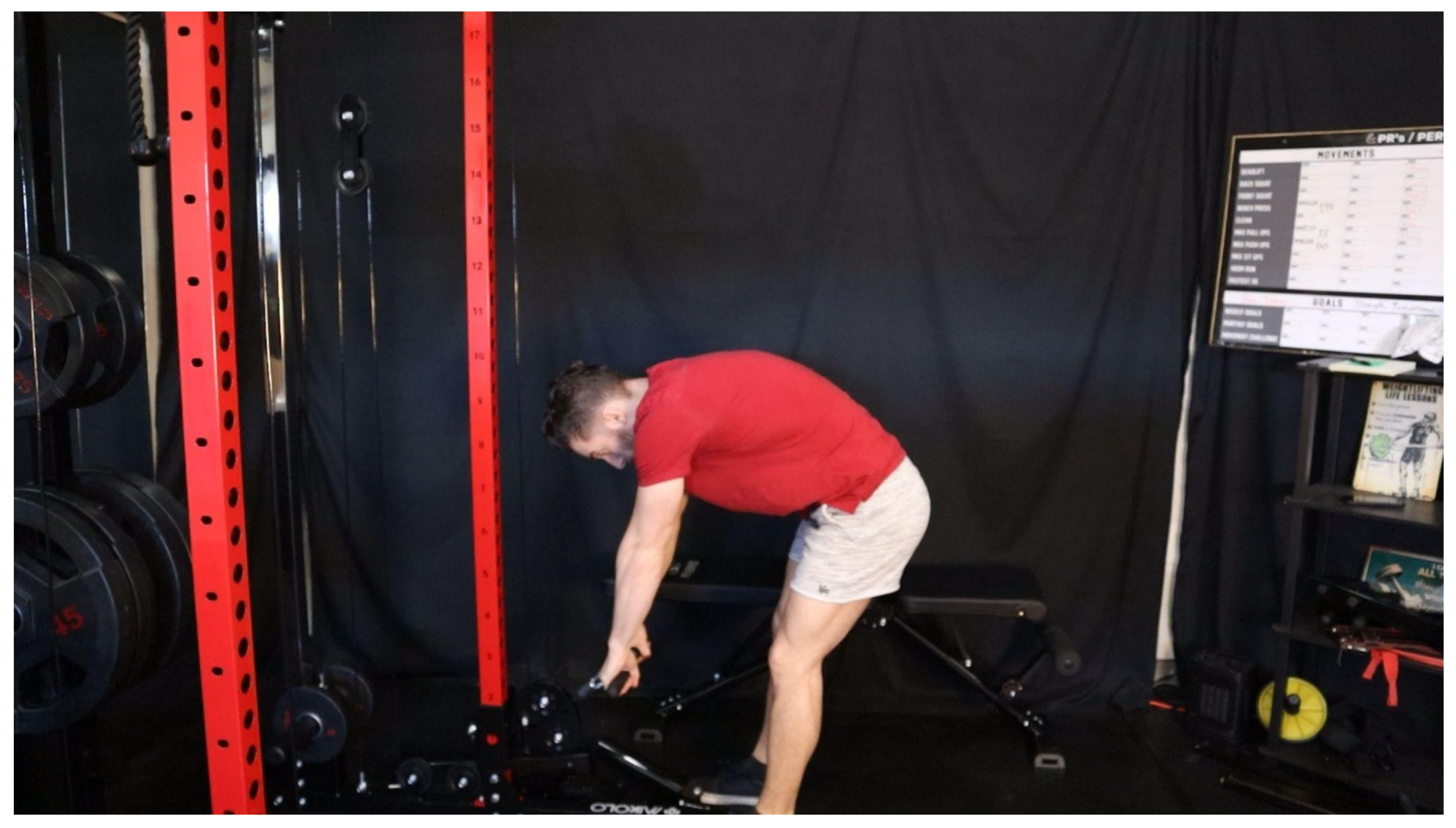

Figure 11.

Position 1 of the cable toe touches.

Figure 11.

Position 1 of the cable toe touches.

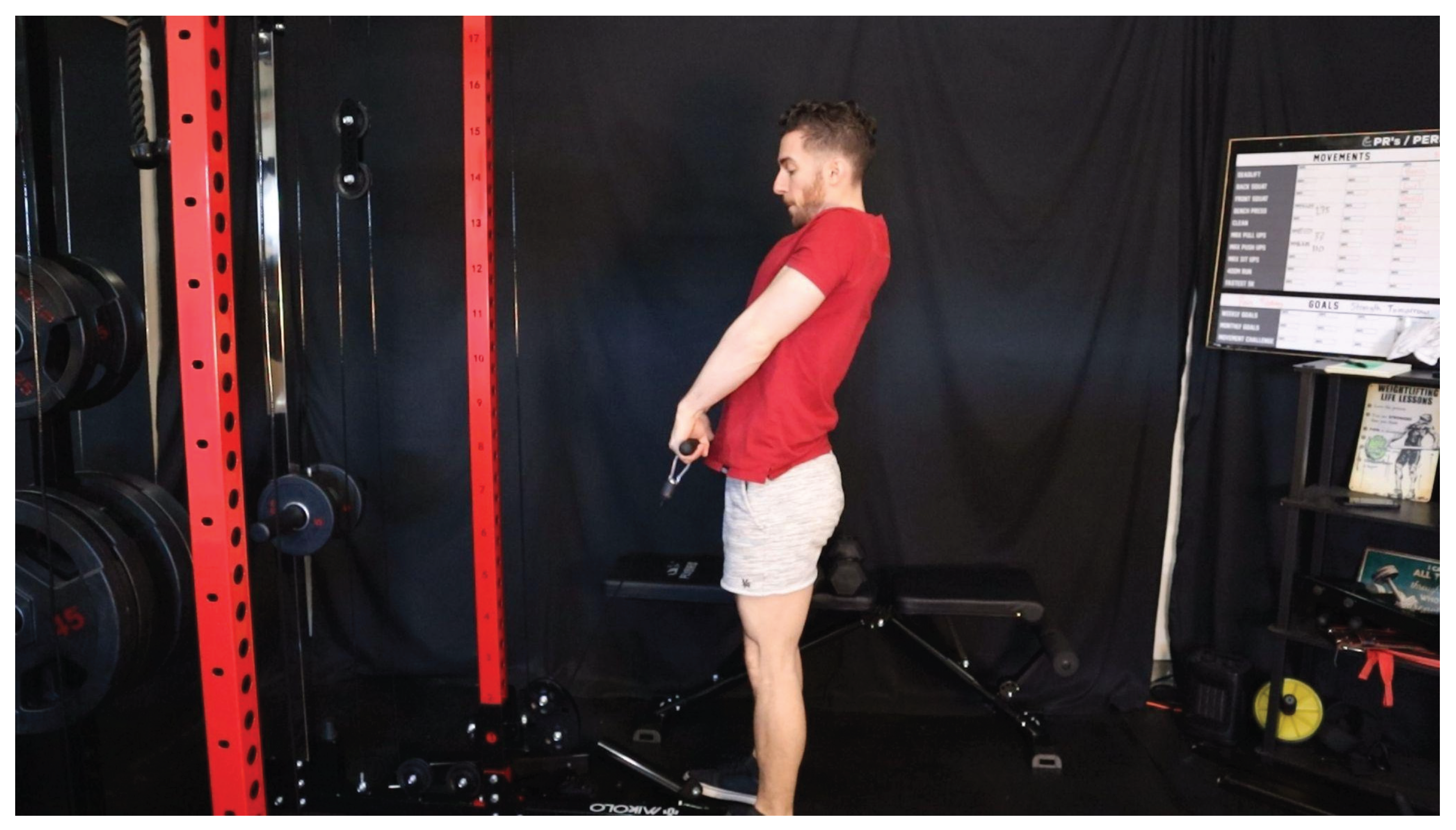

Figure 12.

Position 2 of the cable toe touches.

Figure 12.

Position 2 of the cable toe touches.

Posture and Alignment

Proper posture and spinal alignment play a crucial role in spinal erector health, movement efficiency, and injury prevention. The spine is designed to move dynamically through flexion, extension, and rotation, yet many individuals develop compensatory movement patterns due to prolonged static postures, muscular imbalances, or improper training habits. Poor posture, particularly excessive anterior pelvic tilt or excessive lumbar lordosis, can place undue stress on passive structures such as the intervertebral discs and ligaments, leading to chronic pain and movement dysfunction (McGill, 2015). Strengthening the spinal erectors through controlled, intentional movement patterns can help correct postural imbalances, reinforcing proper spinal alignment and reducing the risk of pain and dysfunction.

Maintaining a neutral spine is often emphasized in strength training, yet avoiding controlled spinal flexion altogether can create weaknesses and limitations. A rigid spine is not necessarily a strong spine—rather, resilience is built through strengthening the spinal erectors across a variety of movement patterns (Van Dieën et al., 1999). Studies indicate that individuals who avoid spinal flexion entirely tend to develop stiffness and compensatory hip dominance, leading to inefficient force transfer during lifting and bending movements (Steele et al., 2015). Proper training should aim to reinforce postural awareness while also allowing for safe, progressive exposure to spinal flexion, ensuring that the spinal erectors are capable of handling real-world movements effectively.

Incorporating spinal erector exercises that train both flexion and extension can significantly improve postural control and movement efficiency. Exercises such as seated good mornings and toe touches train the spine through full ranges of motion, enhancing neuromuscular coordination and movement fluidity. Similarly, back extensions and cable back extensions develop isometric and concentric strength in the spinal erectors, improving postural endurance for daily activities and athletic performance. Research suggests that reinforcing postural endurance through targeted strength training can lead to a significant reduction in spinal pain symptoms and improve overall movement function (Danneels et al., 2001).

Beyond strength training, daily habits and ergonomics play a critical role in maintaining proper posture. Prolonged sitting in a flexed position without movement can lead to muscle imbalances, tightness, and reduced spinal erector endurance. Implementing frequent movement breaks, adjusting sitting posture, and integrating mobility work can help maintain spinal alignment and muscular activation throughout the day. Additionally, core training and hip mobility exercises should complement spinal erector training, ensuring that the entire kinetic chain supports proper posture and movement mechanics.

Developing a strong, well-conditioned spinal erector complex goes beyond avoiding poor posture—it requires active engagement, strategic training, and movement variability. By reinforcing proper spinal mechanics through exercise and daily movement habits, individuals can reduce pain, improve performance, and enhance overall spinal health. The next section will discuss progressive overload and recovery, ensuring that spinal erector training leads to sustainable strength gains without excessive fatigue or injury risk.

Progressive Overload and Recovery

Progressive overload and recovery are essential components of an effective spinal erector training program. Strengthening the spinal musculature requires gradual increases in resistance, volume, and movement complexity, ensuring continuous adaptation without excessive strain. At the same time, proper recovery strategies are necessary to prevent overuse injuries, reduce soreness, and optimize long-term gains. Research supports the idea that balancing progressive overload with adequate recovery leads to greater strength adaptations and reduced injury risk (Schoenfeld et al., 2021).

Progressive overload refers to the systematic increase of mechanical stress placed on muscles over time, stimulating hypertrophy and strength gains. In the context of spinal erector training, this can be achieved through gradual increases in weight, repetitions, range of motion, or time under tension. For example, in back extensions and seated good mornings, progressive loading can be applied by adding external resistance such as a dumbbell or barbell. In cable-based movements, increasing the weight stack or slowing down the eccentric phase enhances muscular engagement and control. Elevating the feet in toe touches also increases the range of motion, further challenging the spinal erectors. Regardless of the method used, incremental increases in difficulty must be controlled and intentional, preventing excessive strain on the spine.

While progressive overload is necessary for strength development, recovery plays an equally important role in muscle adaptation. The spinal erectors experience significant stress during resistance training, requiring adequate rest and recovery strategies to prevent fatigue-related injuries. Studies indicate that muscle tissue requires 48 to 72 hours for full recovery following intense strength training sessions, depending on individual training volume and intensity (Damas et al., 2019). Overtraining the spinal erectors without sufficient recovery can lead to increased muscle stiffness, joint discomfort, and potential injury, emphasizing the need for structured rest periods between sessions.

One of the most effective recovery strategies for spinal erector training is active recovery, which includes mobility work, stretching, and low-intensity movement to enhance blood flow and reduce stiffness. Exercises such as cat-cow stretches, spinal decompressions, and light core work can promote circulation and reduce muscle tightness after heavy spinal training. Additionally, sleep quality, hydration, and nutrition play crucial roles in optimizing recovery. Studies highlight that adequate protein intake and hydration contribute to muscle repair, while sleep deprivation negatively impacts recovery and performance (Vitale et al., 2019).

Monitoring training frequency and adjusting intensity based on fatigue levels can prevent overuse injuries and ensure long-term progression. A well-structured program should incorporate at least one to two rest days between intense spinal erector training sessions, allowing for sufficient recovery. Training variation, such as alternating between different spinal erector exercises, also reduces repetitive stress on the same muscle groups while maintaining strength progression.

Balancing progressive overload with recovery ensures that spinal erector training leads to strength gains without excessive fatigue or injury risk. By gradually increasing resistance and allowing for proper recovery, individuals can develop strong, resilient spinal erectors capable of handling both daily and athletic demands. The final section will summarize key takeaways and discuss the long-term benefits of incorporating spinal erector training into a comprehensive strength program.

Conclusions

Spinal erector training is an essential yet often overlooked component of strength and conditioning programs. The widespread misconception that spinal flexion should be avoided has led many to undertrain the spinal musculature, contributing to chronic pain, stiffness, and increased injury risk. However, research indicates that controlled exposure to both flexion and extension-based movements can significantly enhance spinal resilience, muscular endurance, and overall movement efficiency (McGill, 2015). By challenging outdated beliefs and implementing a structured approach to spinal erector training, individuals can reduce their risk of injury while improving functional strength and mobility.

A well-rounded spinal erector training program should incorporate both extension and flexion-based exercises, ensuring that the spine is strengthened through its full range of motion. Exercises such as back extensions and cable back extensions reinforce posterior chain endurance, while seated good mornings and toe touches encourage controlled spinal flexion under load. Each of these movements plays a unique role in developing spinal strength, mobility, and resilience, preparing the body for real-world tasks that involve bending, lifting, and stabilizing against resistance. Additionally, progressive overload must be applied systematically, with gradual increases in weight, range of motion, or time under tension to stimulate muscular adaptation.

Equally important is the role of recovery in long-term strength development. The spinal erectors are involved in nearly all movement patterns, making proper rest and active recovery strategies crucial for avoiding overuse injuries. Ensuring adequate sleep, hydration, and mobility work can enhance recovery efficiency, preventing excessive fatigue while allowing for consistent progress (Vitale et al., 2019). A training plan that balances progressive overload with proper recovery will yield the best results, fostering a stronger, more durable spinal musculature capable of withstanding both daily activities and athletic demands.

By integrating intentional spinal erector training into a structured strength program, individuals can significantly reduce pain, improve posture, and enhance overall movement quality. Rather than fearing spinal flexion, controlled training should be embraced as a necessary and beneficial stimulus for spinal health. With the right combination of exercise selection, progressive overload, and recovery strategies, individuals can develop a resilient spinal erector complex, ensuring long-term durability, reduced pain, and improved functional performance.

References

- Deyo, R. A. Deyo, R. A., & Weinstein, J. N. (2001). Low back pain. The New England Journal of Medicine, 344. [CrossRef]

- Hartvigsen, J. Hartvigsen, J., Hancock, M. J., Kongsted, A., Louw, Q., Ferreira, M. L., Genevay, S., Hoy, D., Karppinen, J., Pransky, G., Sieper, J., Smeets, R. J., & Underwood, M. (2018). What low back pain is and why we need to pay attention. The Lancet, 391, 2367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steele, J. Steele, J., Bruce-Low, S., & Smith, D. (2015). A reappraisal of the role of exercise in the prevention and management of chronic low back pain. Journal of Functional Morphology and Kinesiology, 1. [CrossRef]

- McGill, S. M. (2015). Back mechanic: The secrets to a healthy spine your doctor isn’t telling you. BackFitPro Inc.

- Callaghan, J. P., & McGill, S. M. (2001). Intervertebral disc herniation: Studies on a porcine model exposed to highly repetitive flexion/extension motion with compressive force. Clinical Biomechanics, 16(1), 28–37. [CrossRef]

- Radebold, A. Radebold, A., Cholewicki, J., Polzhofer, G. K., & Greene, H. S. (2001). Impaired postural control of the lumbar spine is associated with delayed muscle response times in patients with chronic low back pain. Spine, 26. [CrossRef]

- Van Dieën, J. H. Van Dieën, J. H., Cholewicki, J., & Radebold, A. (1999). Trunk muscle recruitment patterns in patients with low back pain enhance the stability of the lumbar spine. Spine, 28. [CrossRef]

- Schoenfeld, B. J. Schoenfeld, B. J., Grgic, J., & Krieger, J. W. (2021). How does progressive overload promote muscle hypertrophy? Strength and Conditioning Journal, 43. [CrossRef]

- Comfort, P. Comfort, P., Jones, P. A., McMahon, J. J., & Newton, R. U. (2011). Effect of knee and trunk angle on kinetic variables during the squat lift. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 25, 2829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damas, F. Damas, F., Phillips, S. M., Lixandrão, M. E., Vechin, F. C., Libardi, C. A., & Ugrinowitsch, C. (2019). Early resistance training-induced increases in muscle cross-sectional area are concomitant with edema-induced muscle swelling. European Journal of Applied Physiology, 119. [CrossRef]

- Vitale, K. C., Owens, R., Hopkins, S. R., & Malhotra, A. (2019). Sleep hygiene for optimizing recovery in athletes: Review and recommendations. International Journal of Sports Medicine, 40(8), 535–543. [CrossRef]

- Danneels, L. A. Danneels, L. A., Cools, A. M., Vanderstraeten, G. G., Cambier, D. C., Witvrouw, E. E., & De Cuyper, H. J. (2001). The effects of three different training modalities on the cross-sectional area of the paravertebral muscles. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports, 11. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).