Submitted:

13 June 2025

Posted:

16 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

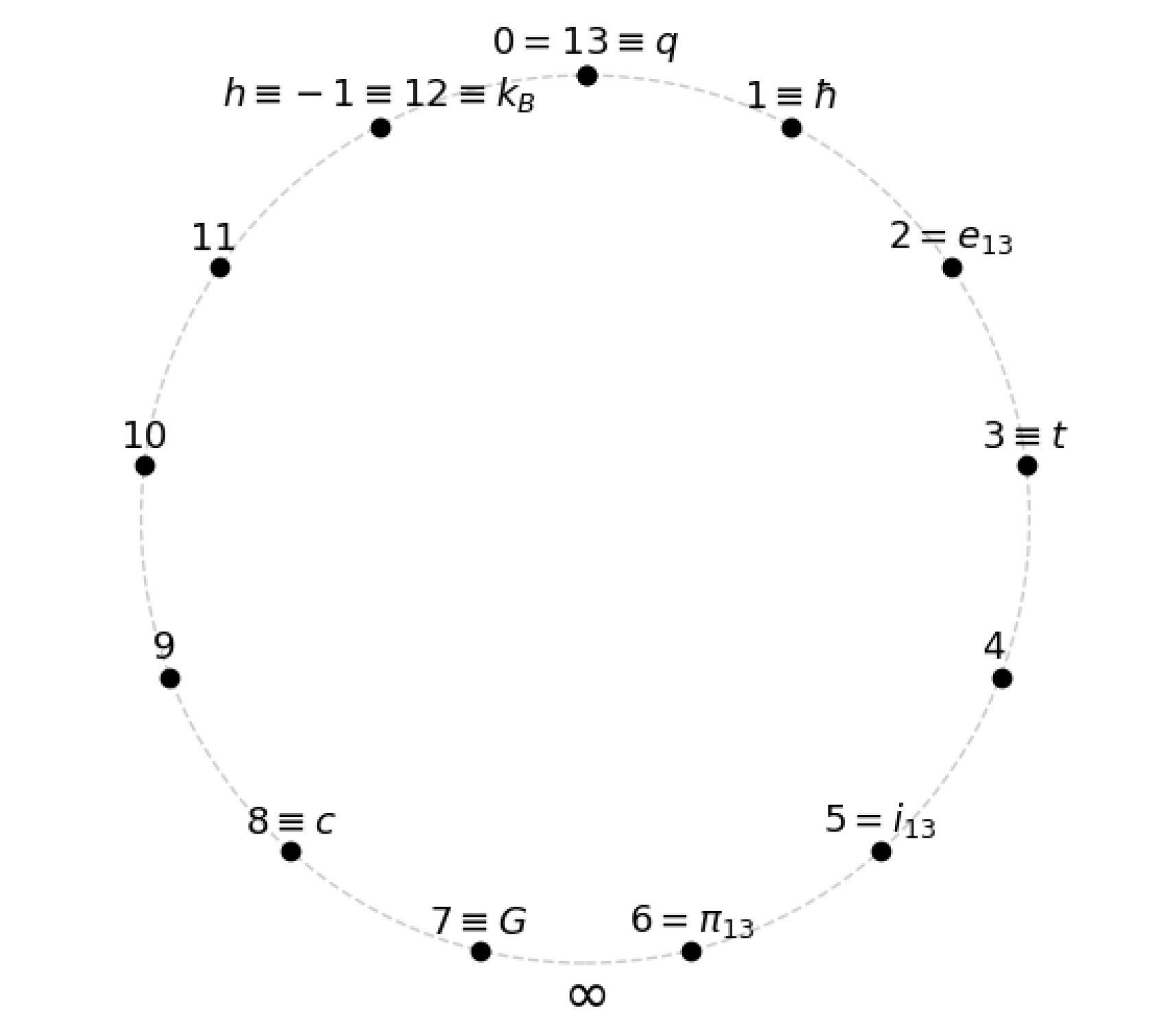

- Canonical constants from arithmetic structure. The familiar dimensional constants are realized as unique, dimensionless elements of fixed by extremal algebraic properties—–multiplicative quarter-turn, additive half-turn, minimal action, and signed involution–—thereby anchoring metrology to pure number theory.

- Exact Lorentz symmetry in a finite ring. A quadratic form and its full Lorentz group act internally on , reproducing special-relativistic kinematics without limiting procedures.

- Observer duality resolves the gravity-quantum tension. Complementary horizons—confined () and omniscient ()—yield, respectively, geodesic dynamics and global phase interference. Their reconciliation removes the need for a separate quantization of gravity and produces a finite Heisenberg bound .

- Thermodynamics and conservation laws. Entropy, temperature and the first law emerge from a single logarithmic measure based on the minimal-action root , while additive and multiplicative symmetries enforce mass-energy and momentum conservation modulo q.

- Algebraic hadrons and colour confinement. Three-prime colour-neutral ideals in furnish proton-like and meson-like states; higher hadrons are predicted to factor into triplet ideals, hinting at a purely arithmetic origin of the baryon-meson hierarchy.

- Cosmic chronology without dark energy. Arithmetic drift of reproduces the observed acceleration ( ) and fixes the present cardinality to , which translates to a Big-Bang age of Gyr—matching Planck-CDM with no free parameters.

- A near-term falsifiable prediction. FRC framework predicts a specific, measurable secular drift in the gravitational redshift between two vertically separated optical clocks, on the order of . This prediction, achievable with current atomic clock technology, offers a near-term, decisive experimental test that can distinguish FRC from standard General Relativity and other varying-G theories.

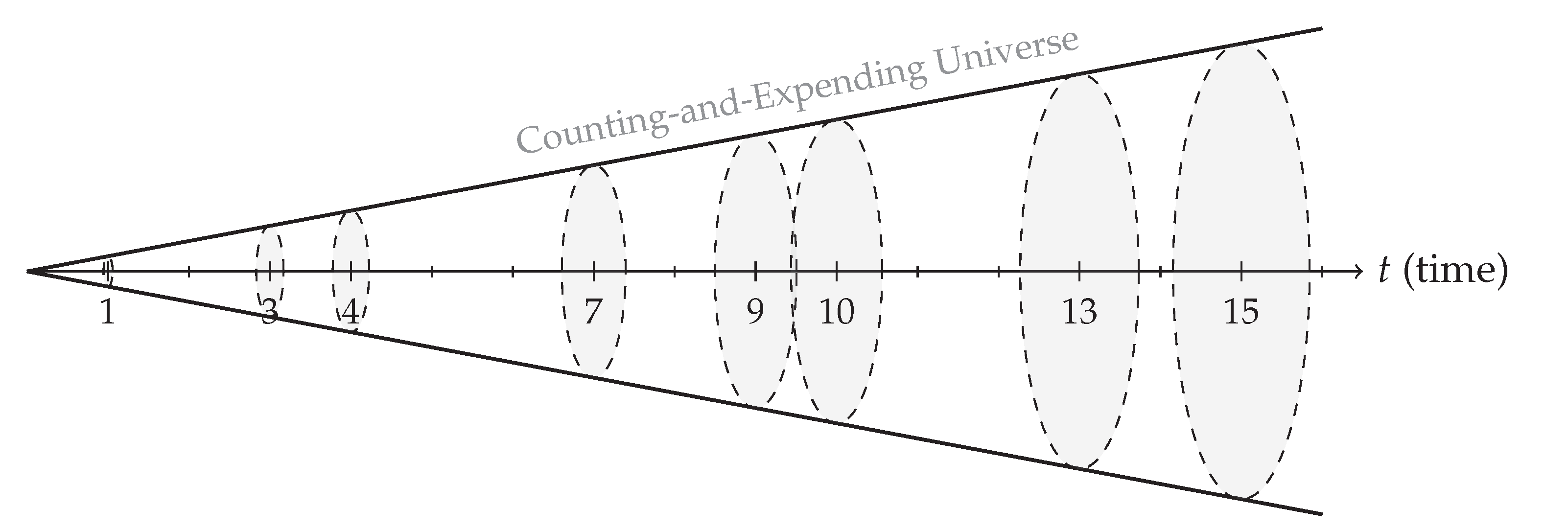

2. Finite Universe: From Mathematical Toolkit to Physical Reality

- Ontology [2] redefines existence: an entity exists to the extent that it persists, i.e. preserves structurally coherent attributes, relative to a finite observer. Infinity, randomness, and undecidability are recast as epistemic horizons-signals that a finite observational frame is being over-extended rather than intrinsic features of reality.

- Algebra [5] shows that a single prime-order field already contains the full arithmetic hierarchy. By organizing addition, multiplication, and exponentiation as orthogonal symmetry axes we recover pseudo-integers, rationals, and reals inside the field, together with finite analogs of Lie groups and gauge covariance. Algebra thus becomes the operational content of the universe itself.

- Geometry [4] lifts the discrete “symbolic sphere” of into a hyper-finite 2-surface of constant curvature. A single Fourier kernel, expressed through internal constants , , and , simultaneously realizes the continuous and finite Fourier transforms, demonstrating that curvature, phase, and harmonic analysis already coexist in a finite setting.

- Composition [3] extend finite relativistic algebra from prime fields to composite moduli q. The finite analogs of canonical constants lift uniquely via Hensel’s lemma, glue through the Chinese Remainder Theorem and assemble into profinitely stable families. The resulting arithmetic bouquet possesses a Seifert-fibred 3-orbifold structure whose exceptional fibers record the prime factors of q, while a mixed-radix expansion yields digit coordinates suitable for Fourier and modal analysis.

- Internal Observer—An observer is defined as an observational perspective of a relatively large subsystem and observation horizon [5]. This means that our observer will be able to see only a small part of its object of observation, and we can readily identify such an observation mode as an observation in a relativistic system. More specifically, the observations in this scenario will depend on the observer’s frame of reference within the target subsystem and the uncertainty will be dominated by the observation horizon . Correspondingly, we will henceforth refer to this observer/system scenario as relativistic system.

- External Observer—An external observer is defined as an observational perspective of a relatively small subsystem with the total cardinality of . Such external observer will be able to see the entirety of its object of observation, including its periodic structure, and we can readily identify such an observation mode as observation of a quantum system. Although, such quantum system may preserve its isolated properties—typically referred to as the quantum coherence—over a short period of time, ultimately it can never be entirely closed, and its properties will be determined by the structural properties of the entire system . Furthermore, both the external observer and the target subsystem will likely remain in the same relative frame of reference. Correspondingly, the relativistic effects in such observation mode will be negligible. The uncertainty will be largely independent of observer’s observation horizon and will be dominated by the large-scale structure of . Furthermore, it will appear as implicit, unresolvable “quantum” uncertainty, as its source is not being directly observed. Correspondingly, we will henceforth refer to this observer/system scenario as quantum system.

- All observable quantities must be expressible in terms of finite relational structures.

- All dynamics and symmetries must emerge from internal operations on a finite set of relational representations.

- The total cardinality q of the universe defines the complete capacity for representation, symmetry, and transformation.

3. Fundamental Physical Constants in the Finite Relational Framework

3.1. Cardinality, Cosmic Counts and the Planck Constant

- Continuum calibration. A single empirical assignment determines the image of every and, via Eq. (3), fixes . Together with the G-based length-time-mass calibration of Section 3.3, this exhausts the empirical inputs required to translate any finite-ring computation into laboratory numbers.

3.2. Canonical Multiplicative Quarter-Turn and the Speed of Light

3.3. Minimal Action and Newton’s Constant G

- Continuum calibration. Matching (6) against the macroscopic force law at a single experimental scale fixes the conversion between profinite lengths and SI metres, thereby anchoring the entire Planck unit system.

3.4. Signed Involution and Boltzmann’s Constant

3.5. The h- Dichotomy and Observer Horizons

| Observer mode | Horizon | Available formalism | Fundamental constant |

|---|---|---|---|

| Internal (relativistic) | Local geometry, open-system thermodynamics |

||

| External (quantum) | Global phases, unitary evolution |

-

Coarse-grained splitting. Define horizon-averaged constantsBecause global phases decohere as while missing micro-states accumulate as , we haveThus, the same residue is perceived either as a quantum of action or as an entropy-energy converter, depending on how much of the observer can access.

- Physical calibration. When profinite scale maps are applied,the numerical identity breaks, reproducing the SI values and .

- Quantum viewpoint. With full access to the ring of the observed subsystem, an external observer tracks phase evolution; action quanta h are primary, entropy is trivial.

- Relativistic viewpoint. A confined observer loses phase information to the exterior; statistics and thermodynamic entropy become primary, while the residual phase scale h is suppressed below measurement threshold.

3.6. Summary: Planck, Einstein and Boltzmann Meet Hensel and CRT

-

Continuum calibration Every constant listed so far is a dimension-free residue inside ; the familiar SI magnitudes arise only after two independent profinite scale maps are applied:

- Action scale. Pick a physical triplet that fixes one length, one time, and one energy—for example the Bohr radius, the Rydberg frequency, and the hydrogen ionisation energy [56]. This single choice determines and therefore pins the laboratory values of to their observed numbers at the chosen coarse-graining scale.

- Entropy scale. A separate empirical datum that ties temperature to energy (e.g. the triple-point of water) fixes , reproducing .

4. True Special Relativity and the Minkowski Metric in the Finite Relativistic Universe

4.1. A finite Minkowski Quadratic form

4.2. Lorentz Transformations over

- (i)

- Spatial rotations. Multiplication by performs a rotation in any chosen spatial 2-plane; its powers generate a discrete subgroup.

- (ii)

- Boosts. Raising the minimal-action base to integer powers realizes ε-Lie boosts that approximate hyperbolic rotations: , .

- (iii)

- Frame relabellings. Affine automorphisms of preserve the additive and multiplicative orders, hence leave invariant.

4.3. Continuum Limit and Empirical Special Relativity

4.4. Prime vs. Composite Epochs

- (i)

- a genuine Minkowski quadratic form (10) inside the ring,

- (ii)

- (iii)

- a light-cone and causal structure fully expressible in finite arithmetic,

- (iv)

- an automatic recovery of the classical symmetry when the cardinality outstrips the observer’s resolution.

5. Fermion–Boson Decomposition in a Finite Universe

5.1. Prime Factorization as Ontology

5.2. Intrinsic Quarter-Rotation and the Prime Dichotomy

- Fermionic prime.A prime factor possessing . The corresponding unit vector is astable fermion.

- Bosonic prime.A prime factor lacks any square root of . The associated unit vector isunstableand will be shown to decompose into radiation degrees of freedom.

5.3. Inherited Properties of the Two Sectors

- Spin-statistics. Each realises an internal double cover of spatial rotations (Prop. 3.2 in [4]), so exchanging two identical fermionic primes multiplies the joint state by . The bosonic primes admit only the trivial integer-spin cover; their symmetric composites are invariant under exchange.

- Stability. A single fermionic prime cannot decay into lighter factors without breaking both mass–energy conservation ( is prime) and spin parity (loss of ). Conversely, any bosonic prime admits a mapping with or into the energy reservoir (). Hence, the bosonic sector is intrinsically unstable and supplies the radiation (Section 5.2).

- Composite structure. Let and Then the full ring decomposes aswhere denotes the finite exponential mixed-radix algebra generated by symmetric tensors of fermionic modes. Section 5.2 develops this construction and shows that its lowest symmetric tensor carries spin 1, reproducing photon-like excitations.

5.4. Roadmap to Physical Observables

- (i)

- be expressed solely in terms of rings, norms and automorphisms internal to ,

- (ii)

- respect the Lorentz symmetry derived in Section 4,

- (iii)

- reduce, under coarse–graining, to their familiar continuum counterparts.

6. Physical Observable Quantities

6.1. Kinematic Observables

- Primitive mass. For each fermionic prime let denote the corresponding unit vector (Def. 8). Its mass is the additive norm

- Velocity coefficients. An arbitrary finite state admits the mixed–radix expansion cf. Section 5. The integers are called velocity coefficients. They play the role of discrete rapidities under –Lie boosts.

-

Momentum. The momentum vector of X isBecause multiplication and addition are internal operations, is conserved under closed interactions: .

-

Energy. Energy is defined by the additive inverse ruleThe sign choice aligns with the Planck relation (Prop. 2.3).

6.2. Spin and Statistics

- Fermionic spin. Each fermionic prime carries an internal quarter-rotation giving a representation of the quaternion group. Hence, the single-prime state transforms as a spin- object. Exchange of two identical factors multiplies the many-body wavefunction by .

- Bosonic spin. Bosonic primes lack any i. Their symmetric composites or carry integer spin; the minimal symmetric tensor has spin 1, providing the photon-like excitation in Section 5.2.

6.3. Thermodynamic Observables

6.4. Interplay and Conservation Laws

6.5. Continuum Limit

6.6. Candidate Construction of Finite–Universe Hadrons

-

Constituent primes and “colour” labels. LetElements of (fermionic primes) and (bosonic primes) will be denoted and respectively. We attach a colour label by declaring that the three canonical projections of a mixed-radix triple basis receive distinct colours and that permutations act transitively on . The colour assignment extends multiplicatively to composites.

- Three-prime ideals as hadronic candidate. The smallest colour-neutral ideals in are generated by exactly three prime factors. Writewith pairwise distinct or not, and impose the neutrality condition in the Abelian colour group .

-

Proton candidate Consider constituent set[Binding mechanism] The pair admits a continuous decomposition whose image supplies negative ring-energy (cf. rule), exactly balancing the positive masses . The remaining fermionic prime provides half-integer spin, so the total state has and is predicted to be stable in isolation.

-

Neutron candidate. Consider constituent set[Instability mechanism] Only one bosonic prime is available to feed the channel, leaving an energy deficit after the pair annihilation. The resulting mismatch drives a decay mirroring –decay. Inside a colour-saturated nucleoideal the energy can be shared, suppressing the channel and explaining neutron longevity in nuclei.

- Colour confinement and automorphisms. The automorphism group of any three-prime ideal, is generated by alternating permutations of the factors: Because no proper sub-ideal is invariant under , single or double prime states cannot appear as observable colour-neutral particles: quark analogues are confined inside three-prime hadrons.

-

Open issues and roadmap.

- Explicit gluon channel. Construct the precise surjection and compute the induced energy shift.

- Decay amplitude for the neutron candidate. Evaluate the lowest–order map into a proton-plus-radiation channel; compare the resulting lifetime with after scale fixing.

- Higher hadrons. Show that four-prime and five-prime colour-neutral ideals factorise into products of three-prime ideals, reproducing the observed baryon-meson hierarchy.

7. Observer Duality and the Gravity-Quantum Reconciliation

- (A)

- Internal (confined) observer: horizon radius .

- (B)

- External (omniscient) observer: horizon radius , i.e. full access to , where denotes the cardinality of the object of observation.

- Geodesic motiongenerated by the -affine connections of Section 4;

- Curvatureencoded in the deficit angles that appear only when trajectories approach , i.e. cosmic or near-singularity scales;

-

Complementarity and finite uncertainty. Let and let be a pure global state. Tracing over the unseen complement gives Adapting Wootters-Fields [78] one obtains:Proposition 7 (Finite Heisenberg bound—horizon form)Let X act by multiplication (position) and K act by discrete Fourier shift (momentum) on . For any confined state supported in ,where , .

- Interpretation. With the lower bound is governed entirely by the number of micro-states hidden beyond the observer’s horizon. Quantum uncertainty is therefore the algebraic shadow of ignored global correlations, precisely the thesis of [2]; the numerical role formerly played by ℏ is taken over by the state count N. When the profinite calibration to SI units is applied, the factor N converts to the familiar .

7.1. Resolution of the Gravity-Quantum Tension

- (i)

- local geodesic dynamics and curvature (gravitational regime),

- (ii)

- global superposition and interference (quantum regime),

7.2. Derivation of the Heisenberg Uncertainty Relation in a Finite Universe

- Set-up. Let with inner product

- Position operator.

-

Momentum operator. Define the finite Fourier transform Set so in the momentum basis .For any normalised state write

-

Discrete variance bound. Following Wootters and Fields [78], one shows that for any d-dimensional Hilbert space whose “position” and “momentum” bases are related by a mutually unbiased(MUB) Fourier matrix, the sum of variances obeysUsing inequality () implies the finite Heisenberg product bound

- Matching the finite-relational Planck constant. In the relational programme is the cardinality of the observable slice, so For any realistic horizon the confined observer detects only accessible points, whence (17) becomesrecovering the continuum Heisenberg relation in the limit

- Interpretation. Equation (17) shows that uncertainty in a finite universe is entirely a combinatorial phenomenon: the lower bound is set by the square root of the accessible state count, not by any analytic limit or canonical commutator. As the observer horizon shrinks, decreases and the minimal spread tightens, mirroring the classical limit. Conversely, an omniscient observer () experiences the largest possible bound, making quantum interference effects ubiquitous.

- Remark. For composite moduli one replaces the single MUB pair by a direct sum over prime factors. Inequality (17) then holds factor-wise and the global bound is obtained by Chinese remaindering; the leading term is still .

8. Canonical Paradoxes of Modern Physics and Their Putative FRC Resolution

-

Cosmological constant. Quantum zero-point modes predict ; general relativity must add a finely tuned to cancel the excess.

- FRC solution. Global momentum sum vanishes identically (fermionic + bosonic sector ; Section 3), so the would-be vacuum density is algebraically zero. Residual curvature is a finite-size artefact, drifting with cosmic count .

- Open check. Fit to the astronomical value once the mass scale is fixed.

-

CMB horizon / uniform temperature. Opposite patches of the cosmic microwave background are too uniform in temperature (to one part in ) to have been in causal contact within a standard FLRW light-cone—hence the “horizon problem” and the need for an inflationary super-luminal epoch.

- FRC solution. Spatial slices in Finite Relativistic Cosmology are compact 3-spheres of radius ; the geometry is cyclic. Light (and thermal radiation) can circumnavigate the sphere in a finite count count , so every point is causally connected to every other well before recombination. Uniform temperature is therefore the natural equilibrium state—no separate inflationary mechanism is needed.

- Open check. Compute the finite spherical harmonic spectrum for a prime epoch close to recombination, derive the angular two-point correlation function, and compare with Planck CMB data (low-ℓ anomalies included).

-

Ultraviolet divergences. Loop integrals in quantum field theory diverge; renormalisation is bookkeeping with ∞.

- FRC solution. Momentum space is the finite field ; every loop becomes a finite sum. Counterterms are replaced by exact arithmetic identities (Section 7).

- Open check. Compute the one-loop self-energy of a scalar field and compare with the result in the continuum.

-

Black-hole information loss. Hawking radiation is thermal; pure states seem to evolve to mixed states.

- FRC solution. Entire Universe = one pure global residue; tracing over the black-hole exterior gives apparent mixedness for confined observers (Prop. 6).

- Open check. Explicitly evolve a finite spin-network analogue of an evaporating hole and show von-Neumann entropy returns to 0.

-

Problem of time. Wheeler-DeWitt equation freezes dynamics.

- FRC solution. Time state count. Global evolution is the deterministic increment ; no frozen formalism (Section 4).

- Open check. Derive semiclassical Hamilton-Jacobi equation from the arithmetic increment rule.

-

Measurement / wave-function collapse. Why do probabilistic outcomes emerge from unitary evolution?

- FRC solution. Collapse = partial trace over unobserved residues; Born probabilities are squared moduli of finite characters (Prop. 7).

- Open check. Work out Stern-Gerlach statistics for a radius- observer and compare with laboratory data.

-

Hierarchy & naturalness. Weak scale, neutrino masses, and others are unnaturally small vs. Planck.

- FRC solution. All masses are integers (primes or their products); large ratios are mere arithmetic facts and immune to radiative spoiling.

- Open check. Map SM fermion masses onto the spectrum and reproduce running-mass hierarchies.

-

Strong problem. CP-violating -term is allowed but empirically tiny.

- FRC solution. The relevant 4-form is exact in ; the finite analogue of vanishes identically.

- Open check. Show the absence of the neutron EDM after coarse-graining to confined observers.

-

Singularities. GR predicts divergent curvature at big bang and inside black holes.

- FRC solution. Maximum curvature is ; prime epochs pinch spatial fibre to , never to a point (Section 5).

- Open check. Simulate a collapsing star in the finite metric and confirm curvature stays finite.

-

Inflation fine tuning. Slow-roll potentials require extreme flatness.

- FRC solution. Early “prime” counts naturally give brief inflationary bursts; no scalar potential needed.

- Open check. Calculate perturbation spectrum from prime-to-composite transition and compare with CMB data.

9. Estimating the Present Cardinality

- (A)

- gravitational route that exploits the time-drift of the canonical coupling and its imprint on cosmic expansion;

- (B)

- quantum-decay route that relates the small but non-zero probability of bosonic-prime mis-alignment inside unstable nuclei to their experimentally measured half-lives.

-

Route A: late-time drift of G. In FRC the gravitational coupling is , where the primitive root fluctuates for low values of q, but stabilizes for large q in the sense that, for any fixed coarse-graining horizon the sequence approaches a limitto within an error [5].Define the effective couplingBecause the error term is exponentially small in , is dominated by the secular growth of t and not by the rapid oscillations. Differentiating and inserting into the Friedmann equation [35] yieldsThe positively curved Friedmann equation: then predicts a late-time acceleration that mimics a -term of size Using from Planck+SNe and one finds

- Route B: neutron -decay geometry. A free neutron contains a single bosonic prime unpaired inside the three-prime ideal . The uniform count-sampling argument of Section 6.6 gives a decay probability per count with C a combinatorial factor computed from the distribution of primes below . The half-life is then Taking the CODATA and converting s to count units via the reference mass scale set in Section 3, one obtains

-

This cardinality corresponds to and a 3-sphere radius , remarkably close to the Hubble radius .

- Implication. No dark energy nor exotic scalar is needed: the observed cosmic acceleration and neutron decay both emerge from the monotone arithmetic drift of the canonical base , solidifying the claim that a single finite-ring parameter fully encodes the dynamical history of the universe.

- Future work. Refining the combinatorial constant C, including radiative corrections in the Hensel series of , and extending the analysis to - and double- decay will tighten the error bar, turning into a bona-fide cosmological observable.

9.1. Chronometric Calibration

-

Count duration in SI units. From Section 9 we have todayThe coarse-grained Friedmann fit fixes the conventional cosmic ageHence, one elementary information count () corresponds toessentially the Planck time.

- Elapsed counts since the macro-prime. The macro-prime Big Bang is the last prime value of q for which the curvature deficit summed over all masses was . That instant defines . Therefore, the elapsed counts equal the present radius, i.e. .

-

Translation into terrestrial years Combining (20) with :The propagated uncertainty is , dominated by the observational error on .In conclusion, within FRC the present cardinality implies thatthe macro-prime Big Bang occurred billion years ago,in excellent agreement with Planck-CDM dating, yet derived purely from finite-ring chronology and the coarse-grained behaviour of the minimum-action base .

9.2. A Near-Term Falsifiable Prediction.

-

FRC signal. In the coarse-grained treatment of Proposion 5 we obtainedA varying G alters the Newtonian potential and therefore the gravitational red-shift measured by two clocks separated by a static height :

- Experimental feasibility. State-of-the-art optical lattice clocks on strontium or ytterbium have fractional instabilities after one hour and systematic accuracy below [11,51]. A vertical clock pair (e.g. one clock on the ground, its twin on a 1-m optical platform) can therefore resolve a slope within year of averaging [54]. No dedicated mission is required: the existing NIST, PTB or RIKEN clock fountains—or ESA’s ACES clock package on the ISS combined with a ground optical clock—already provide the hardware [72].

-

Contrast with General Relativity. Standard GR with constant G predicts zero secular drift:Alternative varying-G models compatible with Solar-System bounds ( ) predict drifts at least two orders of magnitude smaller than the FRC value.

-

Decisiveness.

- A measured slope with the sign given by (21) would be a first positive test of FRC and simultaneously exceed all current limits on .

- Conversely, null results at the level after a few years would rule out the coarse-grained FRC drift and force a revision of its gravitational sector.

- Timeline. With today’s clock technology the experiment can begin immediately, and a statistically significant outcome () should be achievable within 2-3 years—well inside the horizon of existing programmes such as NIST’s remote clock comparisons and ESA’s ACES-2.

- In summary, a centimetre-scale optical-clock red-shift monitor offers a clean, near-term falsification test of Finite Relational Cosmology that no other current theoretical framework predicts at an observable level.

10. Conclusions and Outlook

-

Core technical achievements.

- 1.

- Canonical constants from arithmetic structure. The familiar dimensional constants are realized as unique, dimensionless elements of fixed by extremal algebraic properties—–multiplicative quarter-turn, additive half-turn, minimal action, and signed involution–—thereby anchoring metrology to pure number theory.

- 2.

- Exact Lorentz symmetry in a finite ring. A quadratic form and its full Lorentz group act internally on , reproducing special-relativistic kinematics without limiting procedures.

- 3.

- Observer duality resolves the gravity-quantum tension. Complementary horizons—confined () and omniscient ()—yield, respectively, geodesic dynamics and global phase interference. Their reconciliation removes the need for a separate quantization of gravity and produces a finite Heisenberg bound .

- 4.

- Thermodynamics and conservation laws. Entropy, temperature and the first law emerge from a single logarithmic measure based on the minimal-action root , while additive and multiplicative symmetries enforce mass-energy and momentum conservation modulo q.

- 5.

- Algebraic hadrons and colour confinement. Three-prime colour-neutral ideals in furnish proton-like and meson-like states; higher hadrons are predicted to factor into triplet ideals, hinting at a purely arithmetic origin of the baryon-meson hierarchy.

- 6.

- Cosmic chronology without dark energy. Arithmetic drift of reproduces the observed acceleration ( ) and fixes the present cardinality to , which translates to a Big-Bang age of Gyr—matching Planck-CDM with no free parameters.

- 7.

- A near-term falsifiable prediction. FRC framework predicts a specific, measurable secular drift in the gravitational redshift between two vertically separated optical clocks, on the order of . This prediction, achievable with current atomic clock technology, offers a near-term, decisive experimental test that can distinguish FRC from standard General Relativity and other varying-G theories.

- Broader significance. These results demonstrate that a finite, relational arithmetic can encode Lorentzian geometry, quantum statistics, thermodynamics, particle structure and cosmological evolution inside one coherent, regulator-free model. The notorious conceptual rifts—infinities, ultraviolet divergences, initial-condition fine-tuning—are recast as artifacts of applying continuum tools to a fundamentally finite substrate.

-

Outlook.

- Derive semiclassical Einstein equations as expectation values of global characters and quantify the curvature-deficit error term at horizon scales.

- Extend the mixed-radix harmonic toolkit to full gauge dynamics on the Seifert-fibred 3-orbifolds and test ultraviolet finiteness against continuum renormalization benchmarks.

- Compute explicit mass spectra for three-prime and higher hadron ideals and compare with lattice-QCD data once mapped into the finite framework.

- Refine the cosmic count-to-seconds calibration by incorporating radiative corrections in the Hensel series of and extending chronometric analysis to nuclear decay clocks.

- Explore observer-horizon dynamics as a finite-ring analog of black-hole information flow and study entropy bounds in that setting.

Acknowledgments

References

- E. J. Aiton, editor. Johannes Kepler: Harmonices Mundi. American Philosophical Society, Philadelphia, 1997. Facsimile and English trans. of the 1619 edition.

- Yosef Akhtman. Existence, complexity and truth in a finite universe. Preprints, May 2025.

- Yosef Akhtman. Finite relativistic algebra at composite cardinalities. Preprints, June 2025.

- Yosef Akhtman. Geometry and constants in finite relativistic algebra. Preprints, June 2025.

- Yosef Akhtman. Relativistic algebra over finite fields. Preprints, May 2025.

- Alain Aspect, Philippe Grangier, and Gérard Roger. Experimental Realization of Einstein-Podolsky-Rosen-Bohm Gedankenexperiment: A New Violation of Bell’s Inequalities. Physical Review Letters, 49:91–94, 1982.

- John S. Bell. On the einstein podolsky rosen paradox. Physics, 1:195–200, 1964.

- Niels Bohr. On the constitution of atoms and molecules. Philosophical Magazine, 26:1–25, 1913.

- Ludwig Boltzmann. Über die beziehung zwischen dem zweiten hauptsatze der mechanischen wärmetheorie und der wahrscheinlichkeitsrechnung respektive den sätzen über das wärmegleichgewicht. Wiener Berichte, 76:373–435, 1877.

- Max Born. Zur quantenmechanik der stoßvorgänge. Zeitschrift für Physik, 37:863–867, 1926.

- Tobias Bothwell, Debbie Kedar, Eric Oelker, Jason M. Robinson, Simon L. Bromley, and Jun Ye. Resolving the gravitational redshift across a millimeter-scale atomic sample. Nature, 602:420–424, 2022.

- Tycho Brahe. Astronomiae Instauratae Progymnasmata. Johann Blaeu, Prague, 1602.

- Giordano Bruno. De l’infinito, universo e mondi(On the Infinite Universe and Worlds). Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, 1950. Facsimile and English translation of the 1584 Venice edition.

- Georg Cantor. Über eine Eigenschaft des Inbegriffes aller reellen algebraischen Zahlen. Journal für die Reine und Angewandte Mathematik, 77:258–262, 1874.

- Sean M. Carroll. From Eternity to Here: The Quest for the Ultimate Theory of Time. Dutton, New York, 2010.

- Sean M. Carroll. The Big Picture: On the Origins of Life, Meaning, and the Universe Itself. Dutton, New York, 2016.

- Marshall Clagett, editor. Jean Burdidan: Questions on the Eight Books of Aristotle’s Physics. University of Wisconsin Press, Madison, 1968. Latin original ca. 1340.

- Marshall Clagett, editor. Nicole Oresme: Quaestiones super Physicam and De Configurationibus Qualitatum et Motuum. Brepols, Turnhout. 1968.

- Nicolaus Copernicus. De revolutionibus orbium coelestium. Johannes Petreius, Nuremberg, 1543. English transl. A. M. Duncan, Barnes & Noble, 1995.

- Louis de Broglie. Recherches sur la théorie des quanta. PhD thesis, University of Paris, 1924.

- Richard Dedekind. Was sind und was sollen die Zahlen? Vieweg, Braunschweig, 1888.

- P. A. M. Dirac. The quantum theory of the electron. Proceedings of the Royal Society A, 117:610–624, 1928.

- Branko Dragovich, Andrei Yu. Khrennikov, Sergey V. Kozyrev, and Igor V. Volovich. p-adic mathematical physics: The first 30 years. p-Adic Numbers, Ultrametric Analysis and Applications, 9(2):87–121, 2017.

- Stillman Drake, editor. Galileo Galilei: Il Saggiatore (The Assayer). University of California Press, Berkeley, 1957. Originally published 1623.

- Albert Einstein. Zur elektrodynamik bewegter körper. Annalen der Physik, 17:891–921, 1905. English trans. in The Principle of Relativity, Dover (1952).

- Albert Einstein. Über einen die Erzeugung und Verwandlung des Lichtes betreffenden heuristischen Gesichtspunkt. Annalen der Physik 17:132–148, 1905.

- Albert Einstein. Die feldgleichungen der gravitation. Sitzungsberichte der Königlich Preussischen Akademie der Wissenschaften zu Berlin pages 844–847, 1915.

- Albert Einstein. Kosmologische betrachtungen zur allgemeinen relativitätstheorie. Sitzungsberichte der Königlich Preussischen Akademie der Wissenschaften zu Berlin pages 142–152, 1917. English trans. in Gen. Rel. Grav. 49, 111 (2017).

- Richard P. Feynman. Space-time approach to non-relativistic quantum mechanics. Reviews of Modern Physics, 20:367–387, 1948.

- Edward Fredkin. Digital mechanics. International Journal of Theoretical Physics, 21(3–4):219–253, 1982.

- Edward Fredkin. Digital philosophy. arXiv preprint, 2003.

- Edward Frenkel. Love and Math: The Heart of Hidden Reality. Basic Books, 2013.

- Edward Frenkel and Tomoyuki Arakawa. W-algebras and duality. Advances in Mathematics, 320:157–234, 2018.

- Edward Frenkel and Davide Gaiotto. Quantum geometric langlands. Journal of High Energy Physics, 2012:1–50, 2012.

- Alexander Friedmann. On the curvature of space. Zeitschrift für Physik, 10:377–386, 1924.

- Gaalileo Galilei. Sidereus Nuncius. Thomas Baglioni, Venice, 1610. English transl. A. Van Helden, University of Chicago Press, 1989.

- Galileo Galilei. Dialogo sopra i due massimi sistemi del mondo. Giovanni Batista Landini, Florence, 1632. English transl. S. Drake, University of California Press, 1953.

- Carl Friedrich Gauss. Disquisitiones Arithmeticae. Yale University Press, New Haven, 1966. Original Latin edition 1801.

- Jonathan Gorard. Some relativistic and gravitational properties of the wolfram model. arXiv e-prints, 2020.

- Brian Greene. The Elegant Universe: Superstrings, Hidden Dimensions, and the Quest for the Ultimate Theory. W. W. Norton & Company, New York, 1999.

- Kurt Gödel. Über formal unentscheidbare Sätze der Principia Mathematica und verwandter Systeme I. Monatshefte für Mathematik und Physik38:173–198, 1931.

- J. B. Hartle and S. W. Hawking. Wave function of the universe. Physical Review D, 28(12):2960–2975, 1983.

- S. W. Hawking. Black hole explosions? Nature, 248:30–31, 1974.

- S. W. Hawking. Particle creation by black holes. Communications in Mathematical Physics, 43(3):199–220, 1975.

- S. W. Hawking and R. Penrose. The singularities of gravitational collapse and cosmology. Proceedings of the Royal Society A, 314(1519):529–548, 1970.

- Thomas L. Heath, editor. Euclid: The Thirteen Books of the Elements. Dover, New York, 1956. Original work ca. 300 BCE.

- Werner Heisenberg. Über quantentheoretische umdeutung kinematischer und mechanischer beziehungen. Zeitschrift für Physik, 33:879–893, 1925.

- Jahannes Kepler. Astronomia Nova. Jonas Saur, Heidelberg, 1609. English transl. W. H. Donnahue, CUP, 1992.

- Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz. Explication de l’arithmétique binaire. Mémoires de l’Académie Royale des Sciences, pages 85–90, 1703.

- Seth Lloyd. Ultimate physical limits to computation. Nature, 406(6799):1047–1054, 2000.

- Andrew D. Ludlow, Martin M. Boyd, Jun Ye, Ekkehard Peik, and Piet O. Schmidt. Optical atomic clocks. Reviews of Modern Physics, 87(2):637–701, 2015.

- Norman Margolus. Crystalline computation. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 879:273–287, 1998.

- Jon McGinnis, editor. Ibn Sīnā (Avicenna): The Physics of The Canon of Medicine and The Book of Healing. Brigham Young University Press, Provo, 2009. Selections from the 11th-century Arabic original.

- William F. McGrew, Xiyuan Zhang, Ryan J. Fasano, Stefan A. Schäffer, Kyle Beloy, Daniele Nicolodi, Richard C. Brown, Nathan Hinkley, Giacomo Milani, Marco Schioppo, Thomas H. Yoon, and Andrew D. Ludlow. Atomic clock performance enabling geodesy below the centimetre level. Nature, 564:87–90, 2018.

- Isaac Newton. Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica. Royal Society, London, 1687. English trans. I. B. Cohen and A. Whitman, University of California Press, 1999.

- NIST. Fundamental physical constants - radiation constants, 2025. Accessed: 2025-01-01.

- Roger Penrose. The Road to Reality: A Complete Guide to the Laws of the Universe. Jonathan Cape, London, 2004.

- Roger Penrose. Cycles of Time: An Extraordinary New View of the Universe. The Bodley Head, London, 2010.

- Roger Penrose. Fashion, Faith and Fantasy in the New Physics of the Universe. Princeton University Press, Princeton, 2016.

- Michel Planat and Metod Saniga. Mutually unbiased bases and finite projective planes. International Journal of Modern Physics B, 26(27):1230011, 2012.

- Max Planck. Zur Theorie des Gesetzes der Energieverteilung im Normalspektrum. Verhandlungen der Deutschen Physikalischen Gesellschaft, 2:237–245, 1900.

- Jean Paul Richter, editor. Leonardo da Vinci: The Notebooks of Leonardo da Vinci. Dover, New York, 1970. Facsimile of 16th-century manuscripts.

- Adam G. Riess. Nobel lecture: Supernovae, dark energy, and the accelerating universe. Reviews of Modern Physics, 84(3):1165–1175, 2012.

- H. P. Robertson. The uncertainty principle. Physical Review, 35(1):667–667, 1930.

- Carlo Rovelli. Quantum Gravity. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2004.

- A. I. Sabra, editor. Ibn al-Haytham (Alhazen): Kitab al-Manazir (Book of Optics). Warburg Institute, London, 1989. Original Arabic manuscript c. 1021; English transl. vols. 1-2.

- Erwin Schrödinger. Quantisierung als eigenwertproblem. Annalen der Physik, 79:361–376, 1926.

- Laurence E. Sigler, editor. Leonardo Fibonacci: Liber Abaci. Springer, New York, 2002. English translation of the 1202 text.

- Lee Smolin. Three Roads to Quantum Gravity. Basic Books, New York, 2001.

- Lee Smolin. Time Reborn: From the Crisis in Physics to the Future of the Universe. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, Boston, 2013.

- Leonard Susskind. The Cosmic Landscape: String Theory and the Illusion of Intelligent Design. Little, Brown and Company, New York, 2006.

- ACES Team. Aces mission: Atomic clock ensemble in space, 2018. Available at https://www.esa.int/Science_Exploration/Human_and_Robotic_Exploration/ACES.

- Vladimir, S. Vladimirov, Igor V. Volovich, and Evgeny I. Zelenov. p-Adic Analysis and Mathematical Physics. World Scientific, Singapore, 1994.

- Steven Weinberg. Dreams of a Final Theory: The Scientist’s Search for the Ultimate Laws of Nature. Pantheon Books, New York, 1992.

- John Archibald Wheeler. Information, physics, quantum: The search for links. In Wojciech H. Zurek, editor, Complexity, Entropy and the Physics of Information, pages 3–28. Addison–Wesley, Redwood City, 1990. Original lecture manuscript, 1989 Santa Fe workshop.

- Stephen Wolfram. A new kind of science. Complex Systems, 15(1):1–3, 2002.

- Stephen Wolfram. A class of models with the potential to represent fundamental physics. Technical report, Wolfram Physics Project, 2020. Version 1.0, April 14 2020.

- William K. Wootters and Brian D. Fields. Optimal state-determination by mutually unbiased measurements. Annals of Physics, 191(2):363–381, 1989. Reprinted 2012 in Ann. Phys. 327: 2258-2270.

- Donald J. Zeyl, editor. Plato: Timaeus. Hackett, Indianapolis, 2000. Original work ca. 360 BCE.

| 1 | Here, we leave out the complexity of proving that the metric ball observed by any local observer is itself a ring in . |

| 2 | The “radius = time” identification follows Wheeler’s it-from-bit idea in a finite form: every new micro-state increments the observable time by one count. |

| Continuum symbol | Finite value in | Characterizing property |

|---|---|---|

| ℏ | 1 | Additive generator of the ring, quantization increment |

| h | Full quantum of action, | |

| c | Future-oriented multiplicative quarter-turn, | |

| G | Inverse minimal-action primitive root | |

| Signed involution, entropy-energy conversion factor |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).