Submitted:

11 June 2025

Posted:

13 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

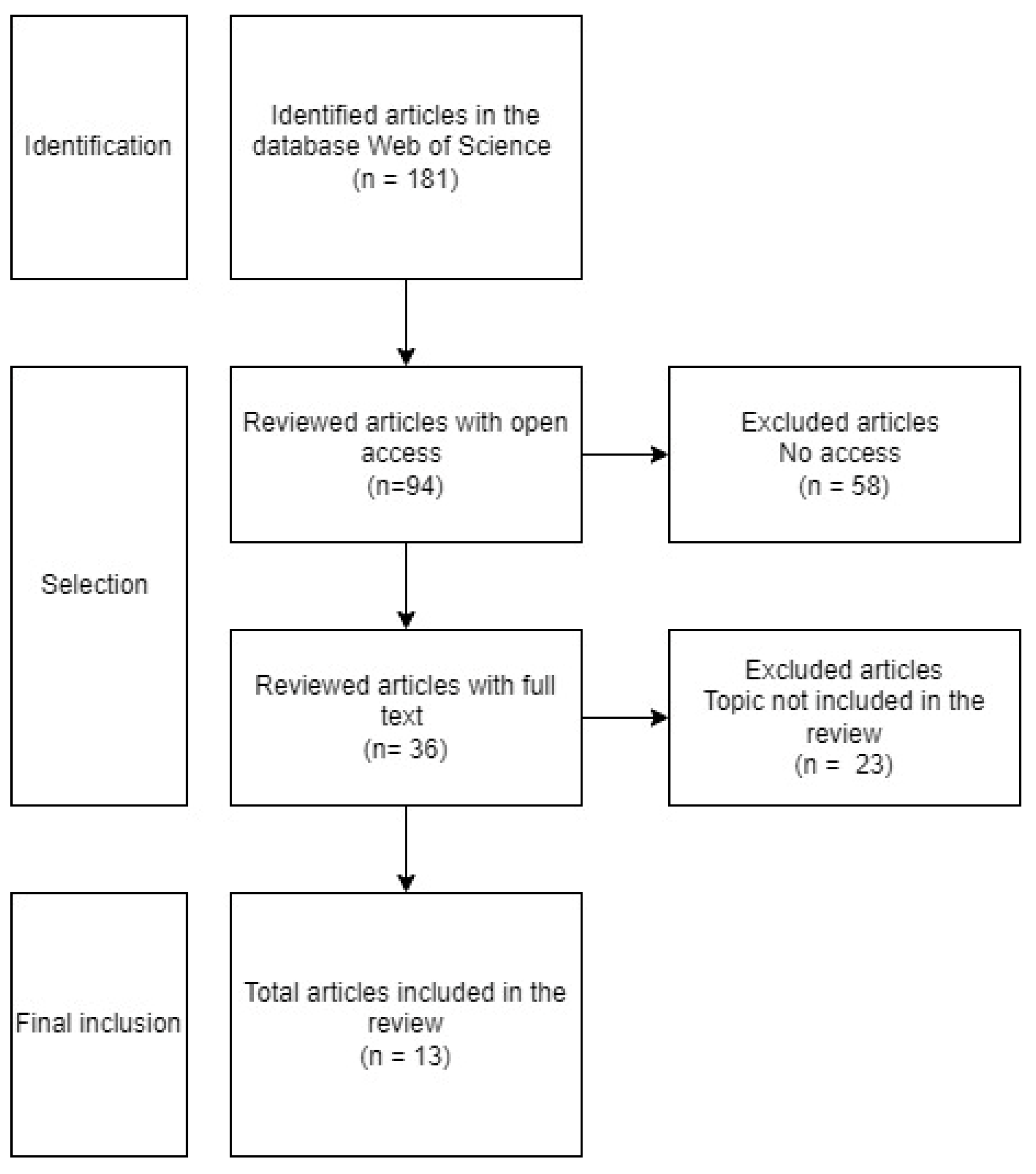

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.2. Literature Search Process

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the Studies

3.2. Content Analysis of the Articles

3.3. Description of Results

3.3.1. Internalizing Symptoms

3.3.2. Externalizing Symptoms

3.3.3. Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder

3.3.4. Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder in Women and Its Impact on Their Children

3.3.5. Long-Term Consequences

3.4. Risk of Bias

3.5. Bibliometric Data of Review Documents

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations

4.2. Practical Implications

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. World Report on Violence and Health: Summary. WHO 2002. Available from: https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/43431.

- López, R.M.; Fernández, M.C. Gender violence: current situation, advances, and pending challenges in the health system response. Atención Primaria 2024, 56, 102767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corsi, J. Violence against women as a social problem: analysis of consequences and risk factors. Emakunde 2010. Available from: https://www.emakunde.euskadi.eus/contenidos/informacion/gizonduz_dokumentuak/es_def/adjuntos/laviolenciahacialasmujerescomoproblemasocial.pdf.

- Neale, J. The beam and shadow of the spotlight: visibility and invisibility in women’s experiences of domestic violence and abuse. Ethos 2019. Available from: https://ethos.bl.uk/OrderDetails.do?uin=uk.bl.ethos.774223.

- Paixão, G.P.D.N.; Pereira, A.; Gomes, N.P.; De Sousa, A.R.; Estrela, F.M.; Da Silva Filho, U.R.P.; De Araújo, I.B. Naturalization, reciprocity, and marks of marital violence: male defendants’ perceptions. Rev. Bras. Enferm. 2017, 71, 178–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, K.; Van Ee, E. Mothers and children exposed to intimate partner violence: A review of treatment interventions. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 1955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mertin, P.; Wijendra, S.; Loetscher, T. Posttraumatic stress symptoms and correlates in women and children from backgrounds of domestic violence. J. Child Adolesc. Trauma 2022, 15, 391–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howell, K.H.; Barnes, S.E.; Miller, L.E.; Graham-Bermann, S.A. Developmental variations in the impact of intimate partner violence exposure during childhood. J. Inj. Violence Res. 2016, 8, 43–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronfenbrenner, U.; Evans, G.W. Developmental science in the 21st century: Emerging questions, theoretical models, research designs and empirical findings. Soc. Dev. 2000, 9, 115–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, H.M.; Hankin, B.L. Exposure to intimate partner violence alters longitudinal associations between caregiver depressive symptoms and effortful control in children and adolescents. Dev. Psychopathol. 2023, 1, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogat, G.A.; Levendosky, A.A.; Cochran, K. Developmental consequences of intimate partner violence on children. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2023, 19, 303–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zvara, B.J.; Mills-Koonce, W.R. The role of early caregiving environments in shaping child stress response systems following exposure to interpersonal violence. Child Dev. Perspect. 2024, 18, 38–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, H.; Li, H. Association between exposure to domestic violence during childhood and depressive symptoms in middle and older age: A longitudinal analysis in China. Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehrensaft, M.K.; Cohen, P.; Brown, J.; Smailes, E.; Chen, H.; Johnson, J.G. Intergenerational transmission of partner violence: A 20-year prospective study. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2003, 71, 741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez, G.A. History of domestic violence in men who perpetrate gender violence. UDC Repository 2016. Available from: https://ruc.udc.es/dspace/handle/2183/18000.

- Capaldi, D.M.; Tiberio, S.S.; Shortt, J.W.; Low, S.; Owen, L.D. Associations of exposure to intimate partner violence and parent-to-child aggression with child competence and psychopathology symptoms in two generations. Child Abuse Negl. 2020, 103, 104434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y. The effects of child maltreatment and exposure to intimate partner violence on the co-occurrence of anxious/depressive symptoms and aggressive behavior. Child Abuse Negl. 2024, 149, 106655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ehrensaft, M.K.; Knous-Westfall, H.; Cohen, P. Long-term influence of intimate partner violence and parenting practices on offspring trauma symptoms. Psychol. Violence 2016, 7, 296–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gower, T.; Jouriles, E.N.; Rosenfield, D.; McDonald, R. Physical and psychological intimate partner violence: Relations with child threat appraisals and internalizing and externalizing symptoms. J. Fam. Psychol. 2022, 36, 1106–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greene, C.A.; Chan, G.; McCarthy, K.J.; Wakschlag, L.S.; Briggs-Gowan, M.J. Psychological and physical intimate partner violence and young children’s mental health: The role of maternal posttraumatic stress symptoms and parenting behaviors. Child Abuse Negl. 2018, 77, 168–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, S.E.; Shin, S.; Corona, R.; Maternick, A.; Graham-Bermann, S.A.; Ascione, F.R.; et al. Children exposed to intimate partner violence: Identifying differential effects of family environment on children’s trauma and psychopathology symptoms through regression mixture models. Child Abuse Negl. 2016, 58, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Showalter, K.; Yoon, S.; Maguire-Jack, K.; Wolf, K.G.; Letson, M. Are dual and single exposures differently associated with clinical levels of trauma symptoms? Child Fam. Soc. Work 2020, 25, 439–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronzón-Tirado, R.; Redondo, N.; Zamarrón, M.D.; Rivas, M.J.M. Does time heal all wounds? How is children’s exposure to intimate partner violence related to their current internalizing symptoms? Front. Psychol. 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pernebo, K.; Fridell, M.; Almqvist, K. Reduced psychiatric symptoms at 6 and 12 months’ follow-up of psychotherapeutic and psychoeducative group interventions for children exposed to intimate partner violence. Child Abuse Negl. 2019, 93, 228–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Oliveira, C.V.R.; Sudfeld, C.R.; Muhihi, A.; McCoy, D.C.; Fawzi, W.W.; Masanja, H.; Yousafzai, A.K. Association of exposure to intimate partner violence with maternal depressive symptoms and early childhood socioemotional development among mothers and children in rural Tanzania. JAMA Netw. Open 2022, 5, e2248836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alanna Association. Gender violence. 2025. Available from: https://www.alanna.org.es/violencia-de-genero/.

- Refuge. Refuge, the largest UK domestic abuse organization for women. 2017. Available from: https://refuge.org.uk/.

- Child Witness to Violence Project – Boston Medical Center. Boston Medical Center. 2025. Available from: https://www.bmc.org/child-witness-violence-project.

| Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria | |

|---|---|---|

| Date | Studies published between 2015 and 2025 | Studies published before 2015 |

| Type of document | Original articles | Books, Theses, Web pages, Conferences, Documents not peer-reviewed |

| Language | Articles in English | Articles in any language other than English |

| Accessibility | Open-access studies | Studies with limited access |

| Population | Women who have experienced gender-based violence Children who have experienced gender-based violence |

Children who have suffered child abuse, but not gender-based violence Children who have suffered sexual abuse Women who have suffered gender-based violence but have no children |

| Age | Articles focused on childhood Articles covering other stages, but whose main age focus is childhood |

Articles that do not include childhood |

| Citation | Sample | Procedure | Assessment | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Capaldia et al. (2020) | 206 children aged 9 to 10 and their female caregivers. Sample drawn from public schools in Oregon, USA, where juvenile delinquency rates are higher than the city average. | Study examining the main associations between gender-based violence and child abuse with externalizing and internalizing behaviors, academic competence, and social competence | -CBCL; Achenbach & Edelbrock, 1983 - CTS; Straus, 1979 |

As child abuse and gender-based violence increase, children’s adjustment in these areas worsens. However, individual abuse has a stronger impact on children than gender-based violence. When they appear at the same time, they influence adolescents more in school performance and children in externalizing behaviors such as aggression and impulsiveness. |

| Chen (2024) | 459 children between the ages of 1 and 3. Sample taken in the U.S. from the second National Survey of Child and Adolescent Well-Being. | Longitudinal study examining how child abuse and gender-based violence affect the development of anxious and depressive symptoms, as well as aggressive behavior. | - CBCL; Achenbach , 1991 - CTSPC; Straus et al., 1998 -CTS2; Straus et al., 1996 |

The emergence of anxious and depressive symptoms and aggressive behavior among children who have suffered abuse and partner violence demonstrate the negative effects of these |

| Clark & Hankin (2023) | 365 children and adolescents between the ages of 7 and 17. Sample drawn from schools in Denver and Colorado | Study assessing how exposure to gender-based violence mediates depressive symptoms and self-regulation in those who have experienced it. | -YLSI; Rudolph & Flynn, 2007 -EATQ-R; Ellis & Rothbart , 2001 |

Children who have experienced gender-based violence have lower scores on self-regulation and higher scores on depressive symptoms. In addition to exposure to this type of violence, individual factors also influence scores on these symptoms. |

| De Oliveira et al. (2022) | 981 mother-child dyads, aged 18 to 36 months. Sample from the Morongo region of Tanzania. | Longitudinal study examining the association between gender-based violence, maternal depressive symptoms, harsh child discipline, and child stimulation with child socioemotional development | -PHQ- 9; Kroenke et al., 1999 - CTSPC; Straus , et al., 1998 -CREDI; McCoy et al., 2017 |

Maternal depressive symptoms may explain the negative association between gender-based violence and children’s socioemotional development. Therefore, clear protocols are needed to help professionals identify this type of violence and make appropriate referrals to protect mothers and children. |

| Ehrensaft et al. (2016) | 243 parents and their children, ages 6 to 18. Random sample from 100 different counties in upstate New York. | A study that analyzes how children’s exposure to gender-based violence affects them and whether the type of upbringing they receive also influences the symptoms. | -CTS; Straus, 1979 |

Children exposed to gender-based violence during childhood are more likely to develop trauma. Intimate partner violence affects parenting, reducing support for the child and increasing negative practices. Positive parenting can act as a protective factor. |

| Greene et al. (2018) | 308 mother-child dyads, aged 3 to 6 years. Sample drawn from the Multidimensional Assessment of Preschoolers Study in the U.S., recruited in pediatric clinics. | Study investigating the relationship between post-traumatic stress disorders in mothers who have suffered gender-based violence and the psychopathology of their children | -CTS- 2; Straus et al., 1996 - PCL; Weathers et al., 1993 -PAPA; Egger et al., 2006 |

Post-traumatic stress disorder experienced by mothers acts as a potential mediator between gender-based violence experienced by mothers and their children’s mental health. They also point to the importance of supporting mothers in their recovery from trauma for their children’s emotional health. |

| Gower et al. (2022) | 535 mother-child dyads, ages 7 to 10. Sample drawn from a large urban area in the southern US. | Study examining the effects of physical and psychological intimate partner violence on children | -CTS; Straus, 1979 -CPIC-Y; Grych, 2000 -RCMAS; Reynolds & Richmond, 1978 -CBCL; Achenbach, 1991 -CDBS; McDonald & Jouriles , 1999 |

Intimate partner violence was linked to anxiety symptoms and disruptive behavior in children, even when physical violence was absent. However, when this type of violence occurred, the consequences were more severe. |

| Lv & Li (2023) | 10,521 middle-aged and elderly individuals. Sample taken from the China Longitudinal Study of Health and Retirement | Study assessing the relationship between experiencing gender violence during childhood and suffering from depression in middle and old age | -CES-D; Radloff, 1977 | Exposure to domestic violence during childhood is associated with a higher likelihood of experiencing depression in middle and old age. Witnessing parental conflict and exposure to corporal punishment were consistently associated with a higher likelihood of experiencing depression later in life. |

| McDonald et al. (2016) | 289 mother-child dyads, ages 7 to 12. Sample drawn from community-based domestic violence agencies in Colorado. | Study examining the differential effects of gender-based violence and family contextual factors on children who experience it | -CBCL; Achenbach & Rescorla, 2001 -CEDV; Edlesonet al., 2008 |

The findings indicate that environmental factors differentially influence the development of post-traumatic stress disorder and other psychopathological symptoms in children exposed to gender-based violence. |

| Mertin et al. (2021) | 50 mother-child dyads. Sample drawn from metropolitan domestic violence services in Adelaide, South Australia. | Study that seeks to evaluate maternal and child emotional functioning in relation to post-traumatic stress symptoms in those who have suffered gender-based violence | -CPSS; Foa et al., 2001 -TSCC -A; Briere , 1996 -TSI -2A; Briere , 2011 |

The emotional responses of older children may tend to reflect their own experiences rather than being a reflection of maternal distress, as seems more likely in children who are younger. |

| Pernebo et al. (2019) | 50 children aged 4 to 13. Sample taken in Sweden from a mental health service that provides interventions. | Study investigating the long-term outcomes of group interventions for children exposed to gender-based violence | -CTS 2; Straus et al., 1996 -SDQ- P; Goodman et al., 2000 - TSCYC; Briere et al., 2001 -EQ- P; Rydell et al., 2003 -BSI; Derogatis & Melisaratos , 1983 -IES-R; Weiss, 2004 |

Children benefit from interventions and reduce symptoms of gender-based violence. Furthermore, children with more severe trauma symptoms benefited the most from the intervention, although maternal psychological problems may have hindered recovery for some of them. |

| Ronzón-Tirado et al. (2023) | 107 mother-child dyads. Sample taken from the Comprehensive Monitoring System for Gender-Based Violence in Spain. | A study that analyzes the effects of gender-based violence, adverse experiences after it ends, and the time it takes for depression and anxiety to appear in children. | -CTS2; Straus et al., 1996 -DASS: Lovibond and Lovibond, 1995 |

There is a high prevalence of depression and anxiety in children who have experienced gender-based violence. Furthermore, experiences of re-victimization and sustained stress also play a role. |

| Showalter et al. (2020) | 580 children between the ages of 3 and 12. Sample taken in the U.S. from a Children’s Advocacy Center. | Study examining whether physical abuse and exposure to gender-based violence are associated with depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress, dissociation, anger, and sexual concerns | -TSCYC; Briere, 1997 -PHQ-9; Kroenke et al., 1999 |

Physical abuse and gender-based violence are implicated to varying degrees in depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress, dissociation, anger, and sexual concerns. |

| Question framing bias (Review design bias) |

Inclusion bias (Inclusion criteria bias) |

Attrition bias (Incomplete outcome data) |

Reporting bias (Selective outcome reporting) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Capaldia et al. (2020) | ● | ● | ● | ● |

| Chen (2024) | ● | ● | ● | ● |

| Clark & Hankin (2023) | ● | ● | ● | ● |

| De Oliveira et al. (2022) | ● | ● | ● | ● |

| Ehrensaft et al. (2016) | ● | ● | ● | ● |

| Greene et al. (2018) | ● | ● | ● | ● |

| Gower et al. (2022) | ● | ● | ● | ● |

| Lv & Li (2023) | ● | ● | ● | ● |

| McDonald et al. (2016) | ● | ● | ● | ● |

| Mertin et al. (2021) | ● | ● | ● | ● |

| Pernebo et al. (2019) | ● | ● | ● | ● |

| Ronzón-Tirado et al. (2023) | ● | ● | ● | ● |

| Showalter et al. (2020) | ● | ● | ● | ● |

| Capaldia et al. (2020) | Chen (2024) |

Clark & Hankin (2023) | De Oliveira et al. (2022) | Ehrensaft et al. (2016) |

Greene et al. (2018) | Gower et al. (2022) |

Lv & Li (2023) |

McDonald et al. (2016) | Mertin et al. (2021) | Pernebo et al. (2019) |

Ronzón-Tirado et al. (2023) | Showalter et al. (2020) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Title | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● |

| Abstract | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● |

| Rationale | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● |

| Aim | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● |

| Design | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● |

| Context | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● |

| Sample | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● |

| Variables | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● |

| Sample size | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● |

| Statistical analyses | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● |

| Descriptive data | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● |

| Outcome data | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● |

| Key results | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● |

| Limitations | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● |

| Interpretation | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● |

| Generalization | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● |

| Document | Journal | Category | Impact factor | Quartile | Citations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Capaldia et al. (2020) | Child abuse & Neglect | Family Studies | 3.4 | Q1 | 12 |

| Chen (2024) | Child abuse & Neglect | Family Studies | 3.4 | Q1 | 65 |

| Clark & Hankin (2023) | Development and Psychopathology | Psychology, Developmental | 3.1 | Q1 | 1 |

| De Oliveira et al. (2022) | Jama Network | Medicine, General & Internal | 13.8 | Q1 | 6 |

| Ehrensaft et al. (2016) | Psychology of Violence | Criminology & Penology | 2.192 | Q1 | 44 |

| Greene et al. (2018) | Child abuse & Neglect | Family Studies | 2.845 | Q1 | 84 |

| Gower et al. (2022) | Journal of Family Psychology | Family Studies | 2.7 | Q2 | 2 |

| Lv & Li (2023) | Behavioral Sciences | Psychology, Multidisciplinary | 2.5 | Q2 | 2 |

| McDonald et al. (2016) | Child abuse & Neglect | Family Studies | 2.293 | Q1 | 39 |

| Mertin et al. (2021) | Journal of Child and Adolescent Trauma | Family Studies | 0.91 | Q1 | 0 |

| Pernebo et al. (2019) | Child abuse & Neglect | Family Studies | 2.569 | Q1 | 8 |

| Ronzón-Tirado et al. (2023) | Frontiers in Psychology | Psychology, Multidisciplinary | 2.6 | Q2 | 0 |

| Showalter et al. (2020) | Child & Family Social Work | Family Studies | 2.386 | Q2 | 5 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).