Submitted:

11 June 2025

Posted:

13 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

| Compounds | Matrix | Extraction methods | Instrument | Number detection | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PFAS | human serum and semen | QuEChERS | UPLC-MS/MS | 17 | [21] |

| Bromophenols | environment | GC-MS | 19 | [22] | |

| Antibiotic | Plasma | Oasis HLB μEluting Plate | HPLC–MS/MS | 50 | [23] |

| Endocrine disrupting chemicals | human amniotic fluid | SPE | LC-MS/MS | 59 | [24] |

| Pesticides and pharmaceuticals | soil, orange leaves and fruits | QuEChERS | LC-MS/MS | 33 | [25] |

| Lipid-soluble pesticides and metabolites | chicken liver and pork | QuEChERS | HPLC-MS/MS | 24 | [26] |

| Alkaloids | cereal-based food | QuEChERS | LC-MS/MS | 42 | [27] |

| Illegal drugs | Sewage | SPE | SPE-ISTD-UHPLC-MS/MS | 28 | [28] |

| Sulfonamide | Livestock | QuEChERS | LC/MS | 31 | [29] |

| Micro-pollutants | Surface water | LLE | GC-MS and GC-MS-MS | 950 | [15] |

| Semi-volatile organic compounds | Floodwater | LLE | GC-MS | 940 | [30] |

| Micro-pollutants | Surface water | SPE | LC-TOF-MS and GC-MS | 1153 | [31] |

| Pesticides | Medicines | QuEChERS or SPE | GC-MS-MS | 147 | [32] |

| Solvents | Drug | SLE | GC-MS | 50 | [33] |

| SVOCs | indoor air | SLE | GC-MS | 73 | [34] |

2. Classification of Organic Compounds in Multi-Residue Analysis

2.1. Based on Functional Use or Source

2.2. Based on Polarity and Solubility

3. Overview of Sample Matrices

4. Technical Requirements in Sample Preparation for the Simultaneous Determination of Organic Compounds

4.1. High and Uniform Recovery Efficiency Across Compound Groups

- Some compounds are highly polar (e.g., organic acids, carbamate pesticides, hydroxylated metabolites), while others are non-polar (e.g., polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons – PAHs, pyrethroid pesticides).

- Some are volatile and thermally stable (suitable for GC analysis), while others decompose at high temperatures and are better suited for LC techniques.

- Optimizing the extraction solvent composition (e.g., acetonitrile can be acidified or basified to extract both neutral and ionizable compounds).

- Combining multiple sorbents in dSPE (e.g., a mixture of PSA, C18, and GCB can simultaneously address matrices rich in organic acids, lipids, and pigments).

- Using internal standards or isotopically labeled standards to correct for losses during sample processing.

- Testing and verifying recovery for each representative compound group, followed by adjustments in extraction and cleanup conditions as needed.

4.2. Matrix Effects

- Suppress or enhance ionization in LC-MS/MS (ion suppression or ion enhancement).

- Clog or damage chromatographic columns, affecting separation efficiency.

- Generate interfering peaks, complicating the identification and quantification of analytes.

- Enhance sensitivity and lower detection limits.

- Improve the accuracy and repeatability of the analysis.

- Protect analytical instruments and extend the lifespan of chromatographic columns and ion sources.

-

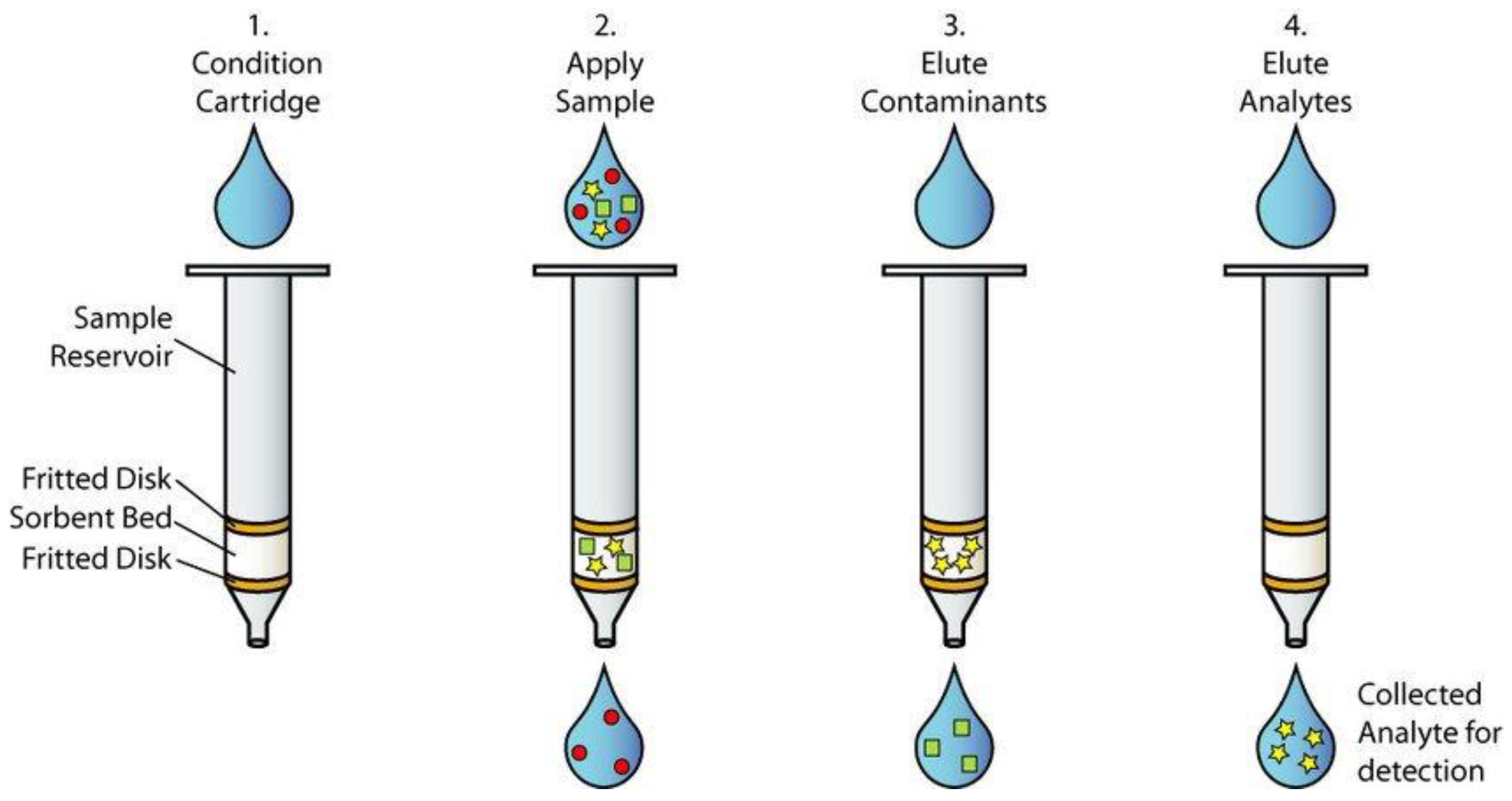

Selective sorbent-based cleanup:The use of specific sorbents in solid-phase extraction (SPE) or dispersive SPE (dSPE), such as PSA (for removal of organic acids and some pigments), C18 (for lipid adsorption), and GCB (for removing pigments and chlorophyll), helps eliminate many interfering substances.

-

Selective phase extraction:Choosing suitable extraction solvents and pH conditions allows for better separation of target compounds from unwanted matrix components.

-

Standardization and internal standards:Internal standards or isotopically labeled standards not only correct for losses during sample processing but also compensate for matrix effects, improving quantification accuracy.

-

Optimized centrifugation and filtration:Thorough centrifugation and filtration steps remove particulate matter, proteins, and large molecules, reducing the risk of clogging and mechanical interferences.

-

Advanced matrix separation techniques:Emerging techniques such as sample preparation using nanomaterials, functionalized materials, or dual-phase separation methods offer improved efficiency in matrix cleanup while maintaining high recovery of target analytes.

4.3. High Repeatability and Accuracy

- In applications such as pesticide residue testing, pharmaceutical analysis, or environmental pollution monitoring, high accuracy is essential to ensure that results comply with international regulations and standards.

- Inconsistent or biased results may lead to incorrect decisions, potentially impacting human health, the environment, or industrial processes.

- Consistency of procedures: Sample handling steps must be strictly standardized in terms of timing, temperature, solvent volumes, and mixing techniques to minimize human-induced variability.

- Stability of sorbents and solvents: High-purity solvents and reusable sorbents should be used to prevent chemical changes or degradation during extraction.

- Sample storage conditions: Extracted and cleaned samples must be stored under proper conditions to avoid degradation or chemical transformation.

- Contamination and matrix effect control: Minimizing background interference enhances measurement accuracy.

- Use of internal standards and calibration: Isotopically labeled internal standards help correct for errors arising during sample preparation and analysis.

- Automation of sample preparation: Automated systems reduce manual handling errors and improve consistency across analyses.

- Training of laboratory personnel: The skill and experience of the operator significantly influence the stability and reproducibility of the procedure.

- Process validation and quality control: Implementing repeated measurements, using quality control (QC) samples, and regularly checking the system help detect and correct deviations promptly.

4.4. Selectivity

- Enhances the purity of the analytical extract, reduces background noise, and minimizes unwanted interactions during chromatographic analysis.

- Prevents unnecessary loss of target compounds due to non-specific adsorption or reactions with incompatible sorbents.

- Improves detection and quantification accuracy, especially for low-concentration compounds or those in complex matrices.

- Type of sorbent material: For example, PSA is effective for removing organic acids and some pigments; C18 is suitable for retaining lipids and non-polar compounds; while GCB is selective for pigments and chlorophyll. Combining these sorbents in dSPE techniques enhances multi-dimensional selectivity for complex matrices.

- Extraction and sample handling conditions: Parameters such as pH, solvent composition, and contact time also influence the selective separation between analytes and matrix components.

- Adsorption mechanisms and chemical interactions: Understanding the interaction mechanisms between sorbents and compounds in the sample helps select appropriate materials and avoid non-specific binding or analyte loss.

- Balancing selectivity and recovery: Excessive selectivity may result in the removal of some target compounds, while insufficient selectivity may fail to eliminate interfering substances. Therefore, optimal conditions must be established to achieve the best compromise.

- Use dispersive solid-phase extraction (dSPE) with a combination of sorbents possessing different functionalities to target a broad range of matrix interferences.

- Apply additional pre-treatment steps such as filtration, centrifugation, or pH adjustment to improve analyte-matrix separation.

- Develop and select novel functionalized sorbents, such as nanomaterials or specialized polymers, which offer high selectivity toward specific classes of target compounds.

4.5. Integration Capability with Analytical Systems

- Ensures chemical compatibility between the sample solvent and the mobile phase, preventing issues such as phase separation, syringe clogging, or peak distortion during chromatography.

- Minimizes manual sample transfer steps such as solvent evaporation, solvent phase switching, or additional filtration—saving time and reducing the risk of analyte loss.

- Enhances automation compatibility, aligning with the trend toward integrated, online, or at-line analytical workflows.

-

Use of extraction solvents compatible with analytical systems:

- ○

- For LC-MS/MS, solvents like acetonitrile or methanol are preferred due to their miscibility with the mobile phase and rapid evaporation at the ion source.

- ○

- For GC-MS/MS, samples must be highly volatile and water-free; thus, solvents like hexane or ethyl acetate are used, and sometimes a solvent evaporation–reconstitution step is required.

- Complete removal of residual solids, proteins, or lipids: These components can clog syringes, affect system pressure, and cause severe background noise in detectors. Strong centrifugation, membrane filtration (0.22–0.45 µm), or lipid removal using C18 sorbents is critical.

- Optimization of sample volume and concentration: The injection volume must meet the requirements of the chromatographic system (typically 1–10 µL for LC, <1 µL for GC), and sample concentration should be adjusted to fall within the detector’s linear range to avoid signal saturation.

- Stability of the processed sample: Samples should remain stable without degradation or transformation during the waiting period before analysis—especially important in automated, chained systems where there may be a delay between sample preparation and analysis.

- Automated QuEChERS systems allow full sample preparation—from extraction to dSPE—and direct injection into LC-MS/MS without manual handling.

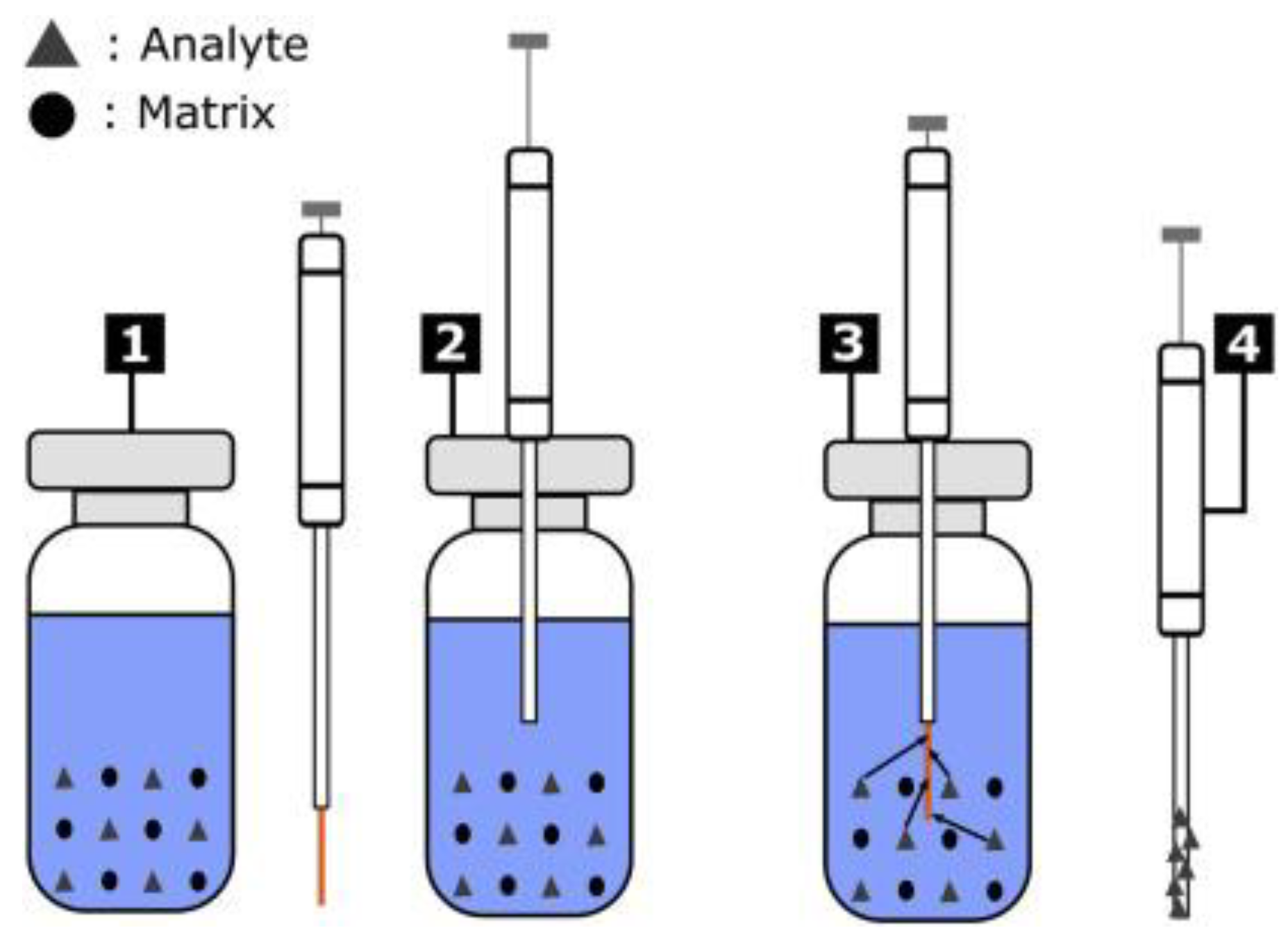

- Directly coupled microextraction techniques, such as solid-phase microextraction (SPME) linked directly to GC-MS, eliminate intermediate processing steps entirely.

- On-line SPE–LC-MS/MS systems, where the sample is cleaned directly on an in-line SPE cartridge and transferred to the LC-MS system without manual withdrawal or filtration.

5. Common Sample Preparation Techniques in Simultaneous Analytical Methods

| Method | Advantages | Applications |

|---|---|---|

| QuEChERS | Fast, low-cost, suitable for multi-residue analysis (pesticides, pharmaceuticals) | Food samples, water, plasma |

| SPE (Solid Phase Extraction) | Good cleanup, flexible with separation phases | Environmental samples, wastewater, biological samples |

| SPME (Solid Phase Microextraction) | Solvent-free, ideal for volatile compound analysis | Air, water, food |

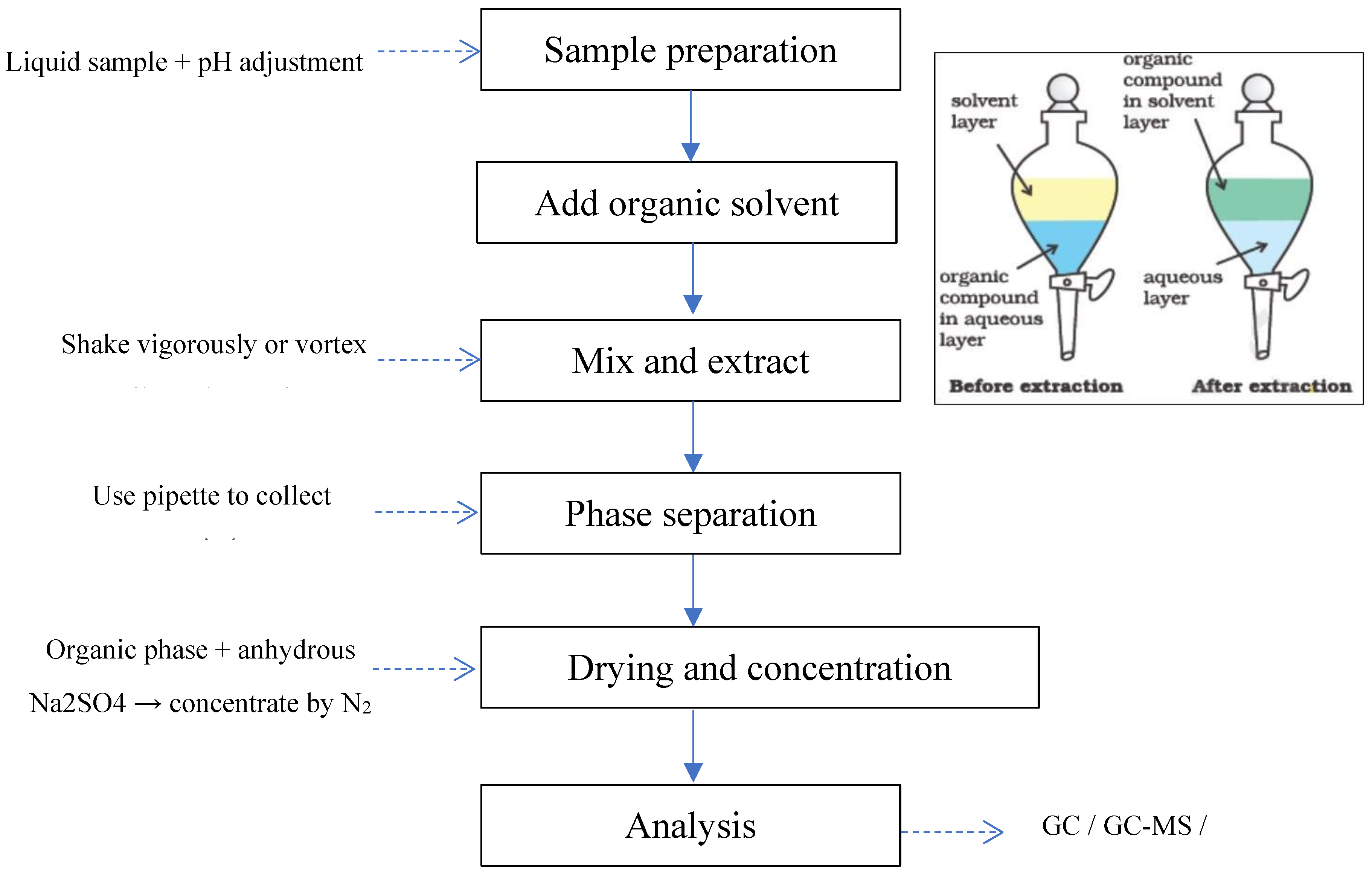

| LLE (Liquid-Liquid Extraction) | Widely used, easy to implement | Water samples, biological samples |

| dSPE (Dispersive SPE) | Enhanced matrix cleanup, commonly used in QuEChERS | Combined with complex sample matrices |

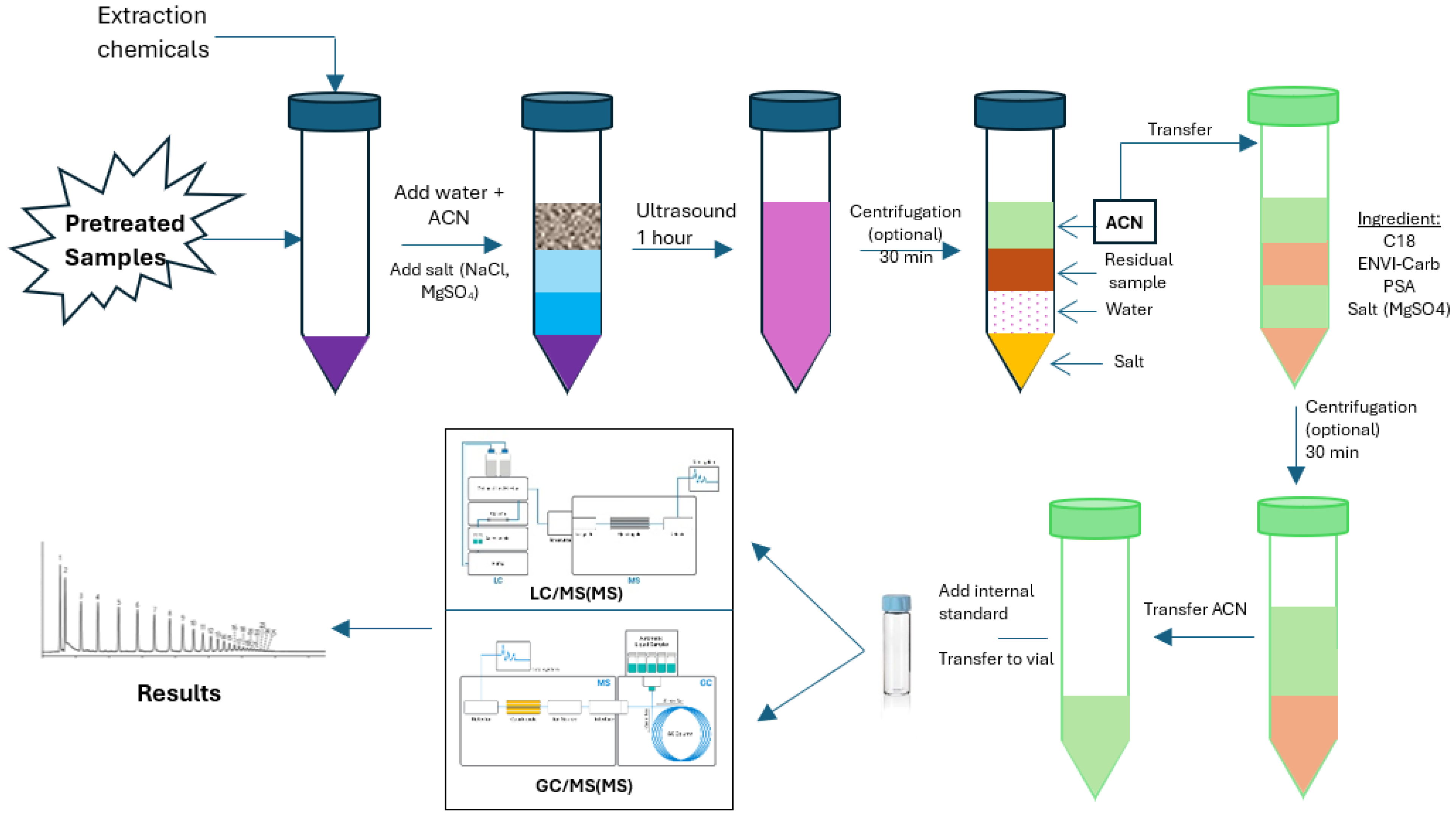

5.1. QuEChERS

-

Extraction:Approximately 5–15 g of solid sample (or an equivalent volume of liquid sample) is placed into a centrifuge tube. The most common extraction solvent is acetonitrile due to its excellent ability to extract polar to moderately non-polar compounds while having low miscibility with water. After adding the solvent, the sample is vigorously shaken to extract the target organic compounds into the organic phase.

-

Partitioning:mixture of anhydrous salts, typically magnesium sulfate (MgSO₄) to remove water, combined with sodium chloride (NaCl) or buffering salts such as sodium citrate or sodium acetate, is added. These salts facilitate a clear phase separation between the organic solvent and water while adjusting the pH to stabilize the analytes. The result is a separated acetonitrile phase containing the analytes, isolated from the aqueous matrix.

-

Clean-up (dispersive Solid Phase Extraction, dSPE):The acetonitrile phase obtained after partitioning is transferred to a tube containing sorbents such as PSA (to remove organic acids and sugars), C18 (to remove lipids), and GCB (to eliminate pigments and chlorophyll). The choice of sorbents or their combinations depends on the sample matrix and the analyte groups. This step significantly reduces matrix interference, improving the sensitivity and accuracy of the measurements.

-

Instrumental Analysis:The cleaned supernatant after centrifugation is collected for analysis by instrumentation such as GC, GC-MS, LC, LC-MS/MS, or GC-FID. QuEChERS allows sample preparation in small volumes, suitable for injection requirements in modern chromatographic techniques. Furthermore, the resulting extract generally has good cleanliness and stability, prolonging column lifetime and reducing ion source contamination in mass spectrometry.

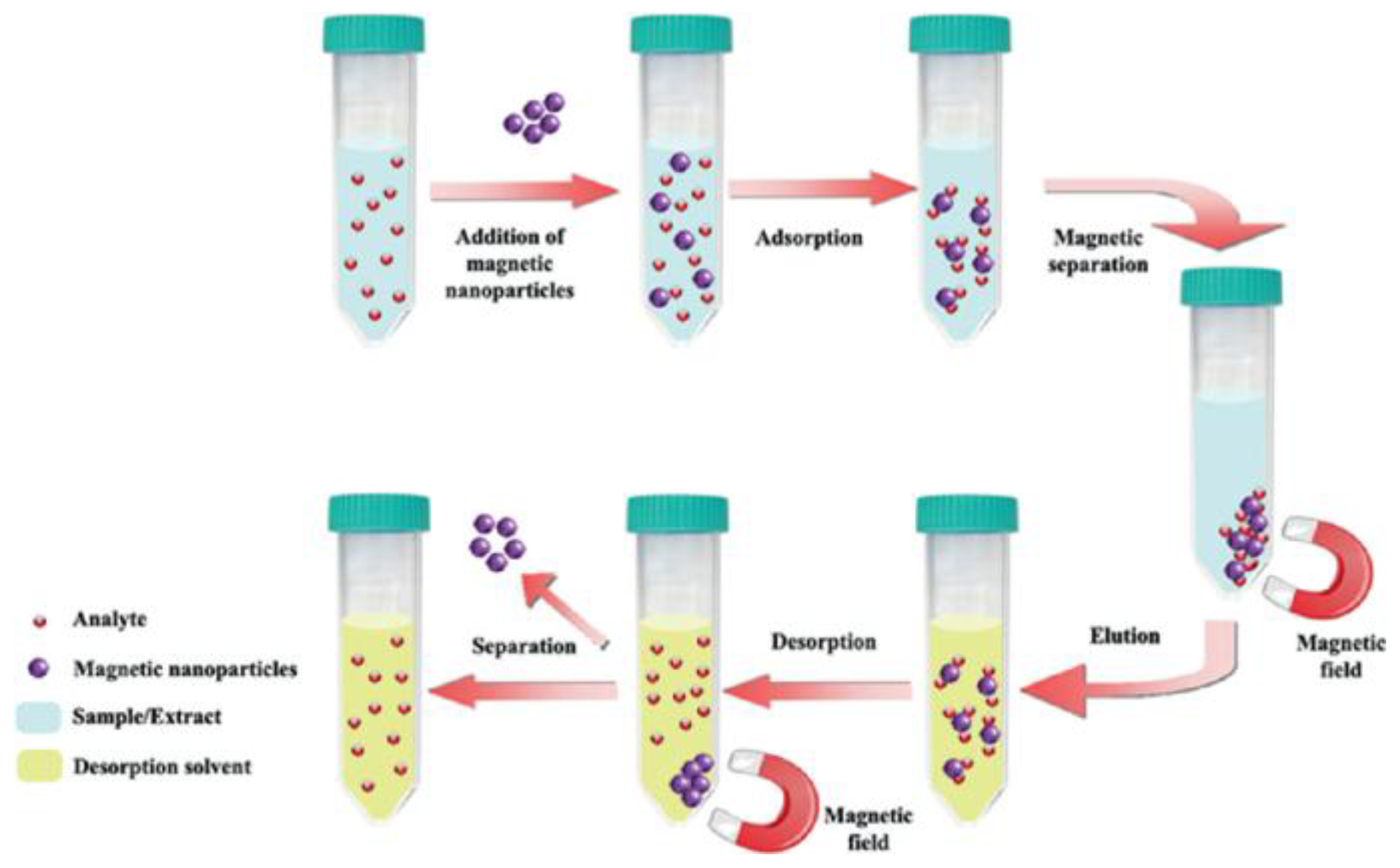

5.2. Solid Phase Extraction

5.3. Solid Phase MicroExtraction

5.4. Liquid-Liquid Extraction

- Low selectivity when compounds with similar physicochemical properties partition into the organic phase, causing high background interference.

- Uneven recovery efficiency since some analytes may remain in the aqueous phase or be lost during solvent evaporation.

- High solvent consumption, impacting sustainability and analysis costs.

5.5. Dispersive Solid Phase Extraction

- PSA (Primary Secondary Amine): removes organic acids, certain sugars, and fatty acids.

- C18 (Octadecylsilane): adsorbs lipids and non-polar compounds.

- GCB (Graphitized Carbon Black): targets pigments and aromatic ring-containing compounds.

- Anhydrous MgSO₄: helps remove residual water from the organic phase.

- Fast and efficient clean-up, minimizing matrix effects on analytical performance.

- No requirement for specialized or vacuum equipment, making it suitable for small-scale laboratories.

- Easily customizable based on sample type by selecting or combining appropriate sorbents.

- Highly compatible with modern chromatographic systems such as LC-MS/MS and GC-MS, enhancing sensitivity and accuracy.

6. Comparison and Selection of Appropriate Sample Preparation Techniques

| Technique | Advantages | Limitations | Typical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| QuEChERS | – Fast, simple, low-cost – Suitable for various analyte groups – Integrates extraction and clean-up | – May not effectively clean complex matrices – Unsuitable for highly polar compounds | Pesticide residues, contaminants in food and environmental samples |

| SPE | – Excellent clean-up, high reproducibility – Allows sample enrichment – Highly customizable by analyte | – Multi-step procedure requiring equipment – Costly when multiple cartridges are used | Pharmaceuticals, pollutants in water and biological matrices |

| dSPE | – Simple and time-saving – Easily integrated with QuEChERS – No need for specialized equipment | – Strongly dependent on sorbent selection – Unsuitable for strongly adsorptive analytes | Rapid clean-up of food extracts, environmental matrices |

| SPME | – Solvent-free – Combines extraction and preconcentration – Well-suited for GC and GC-MS | – Limited to analytes that can be extracted – Requires specialized fibers and equipment; high cost | VOCs and SVOCs in air, water, food headspace |

| LLE | – Effective for non-polar compounds – Easy to perform, no complex equipment needed | – High solvent consumption, not environmentally friendly – Poor phase separation with emulsions or complex matrices | Organic compounds in water, serum, biological samples |

- Chemical diversity of target analytes: For multi-residue analysis, techniques like QuEChERS or SPE are often preferred due to their flexibility and effective matrix removal.

- Sample matrix type: For complex matrices such as food and environmental samples, techniques with strong matrix removal capabilities like SPE or QuEChERS-dSPE are recommended.

- Required detection limits: For high sensitivity requirements, SPE or SPME techniques can preconcentrate analytes prior to analysis.

- Compatibility with analytical instrumentation: Techniques such as QuEChERS, dSPE, and SPME are easily compatible with LC-MS/MS and GC-MS without requiring intermediate processing.

- Automation potential and sample throughput: For labs handling high sample volumes, cartridge-based or 96-well plate SPE and autosampler-compatible SPME are ideal choices.

| Criterion | LLE | SPE | dSPE/QuEChERS | SPME | DLLME |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Selectivity | Low | High | Medium | High | High |

| Automation | Limited | Possible | Possible | Possible | Difficult |

| Solvent saving | No | Moderate | Yes | Yes | Very high |

| Processing time | Moderate | Moderate | Fast | Moderate | Very fast |

7. Coupling Sample Preparation with Chromatographic Techniques

8. Method Validation in Multi-Residue Analysis

9. Perspectives

10. Conclusions

References

- Wang, Z., Walker, G. W., Muir, D. C. G., & Nagatani-Yoshida, K. (2020). Toward a Global Understanding of Chemical Pollution: A First Comprehensive Analysis of National and Regional Chemical Inventories. Environmental Science & Technology, 54(5), 2575–2584. [CrossRef]

- Muir DCG, Getzinger GJ, McBride M, Ferguson PL. How Many Chemicals in Commerce Have Been Analyzed in Environmental Media? A 50 Year Bibliometric Analysis. Environ Sci Technol. 2023 Jun 27;57(25):9119-9129. [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y., Liu, R., Hu, F., Liu, R., Ruan, T., & Jiang, G. (2016). Simultaneous qualitative and quantitative analysis of fluoroalkyl sulfonates in riverine water by liquid chromatography coupled with Orbitrap high resolution mass spectrometry. Journal of Chromatography A, 1435, 66–74. [CrossRef]

- Kalogeropoulou AG, Kosma CI, Albanis TA. Simultaneous determination of pharmaceuticals and metabolites in fish tissue by QuEChERS extraction and UHPLC Q/Orbitrap MS analysis. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2021 Nov;413(28):7129-7140. Epub 2021 Oct 1. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vu-Duc, N.; Nguyen-Quang, T.; Le-Minh, T.; Nguyen-Thi, X.; Tran, T.M.; Vu, H.A.; Nguyen, L.A.; Doan-Duy, T.; Van Hoi, B.; Vu, C.T.; et al. Multiresidue pesticides analysis of vegetables in Vietnam by ultrahigh-performance liquid chromatography in combination with high-resolution mass spectrometry (UPLC-Orbitrap MS). J. Anal. Methods Chem. 2019, 2019, 3489634. [CrossRef]

- D.A. Truong, H.T. Trinh, G.T. Le, T.Q. Phan, H.T. Duong, T.T.L. Tran, T.Q. Nguyen, M.T.T. Hoang, T.V. Nguyen, Occurrence and ecological risk assessment of organophosphate esters in surface water from rivers and lakes in urban Hanoi, Vietnam, Chemosphere, 331 (2023), Article 138805. [CrossRef]

- H.T. Duong, K. Kadokami, H. Shirasaka, R. Hidaka, H.T.C. Chau, L. Kong, T.Q. Nguyen, T.T. Nguyen, Occurrence of perfluoroalkyl acids in environmental waters in Vietnam, Chemosphere, 122 (2015), pp. 115-124. [CrossRef]

- Hoang, T. T. M.; Truong, G.; Kiwao, K.; Thi, H. Chemosphere Occurrence and Risk of Human Exposure to Organophosphate Flame Retardants in Indoor Air and Dust in Hanoi, Vietnam. Chemosphere, 2023, 328, 138597. [CrossRef]

- Thang, P.Q., Taniguchi, T., Nabeshima, Y. et al. Distribution of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons concentrations simultaneously obtained in gas, rainwater and particles. Air Qual Atmos Health 7, 273–281 (2014). [CrossRef]

- V. N. Le, Q. T. Nguyen, T. D. Nguyen, N. T. Nguyen, T. Janda, G. Szalai, and T. G. Le, “The potential health risks and environmental pollution associated with the application of plant growth regulators in vegetable production in several suburban areas of hanoi, Vietnam,” Biologia Futura, vol. 71, no. 3, pp. 323–331, Sep. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen HMN, Khieu HT, Ta NA, Le HQ, Nguyen TQ, Do TQ, Hoang AQ, Kannan K, Tran TM, Distribution of cyclic volatile methylsiloxanes in drinking water, tap water, surface water, and wastewater in Hanoi, Vietnam. Environmental Pollution, 2021, 285:117260. [CrossRef]

- T.M. Le, P.T. Pham, Truong Quang Nguyen, Trung Quang Nguyen, M.Q. Bui, H.Q. Nguyen, N.D. Vu, K. Kannan, T.M. Tran, A survey of parabens in aquatic environments in Hanoi, Vietnam and its implications for human exposure and ecological risk, Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res., 29 (2022), pp. 46767-46777. [CrossRef]

- Alexa Canchola, Lillian N. Tran, Wonsik Woo, Linhui Tian, Ying-Hsuan Lin, Wei-Chun Chou, Advancing non-target analysis of emerging environmental contaminants with machine learning: Current status and future implications, Environment International, 2025, 198, 109404. [CrossRef]

- Rebryk A, Haglund P. Comprehensive non-target screening of biomagnifying organic contaminants in the Baltic Sea food web. Sci Total Environ. 2022 Dec 10;851(Pt 1):158280. Epub 2022 Aug 24. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D.T. Hanh, K. Kadokami, N. Matsuura, N.Q. Trung, Screening analysis of a thousand micro-pollutants in Vietnamese rivers, Southeast Asian Water Environ., 5 (2013), pp. 195-202.

- Yang Gao, Yanhua Chen, Xiaofei Yue, Jiuming He, Ruiping Zhang, Jing Xu, Zhi Zhou, Zhonghua Wang, Rui Zhang, Zeper Abliz, Development of simultaneous targeted metabolite quantification and untargeted metabolomics strategy using dual-column liquid chromatography coupled with tandem mass spectrometry, Analytica Chimica Acta, 2018, 1037, 369-379. [CrossRef]

- Pengwei Guan, Yuting Wang, Tiantian Chen, Jun Yang, Xiaolin Wang, Guowang Xu, and Xinyu Liu, Novel Method for Simultaneously Untargeted Metabolome and Targeted Exposome Analysis in One Injection, Analytical Chemistry, 2025 97 (7), 3996-4004. [CrossRef]

- H.T. Duong, K. Kadokami, S. Pan, N. Matsuura, T.Q. Nguyen, Screening and analysis of 940 organic micro-pollutants in river sediments in Vietnam using an automated identification and quantification database system for GC–MS, Chemosphere, 107 (2014), pp. 462-472. [CrossRef]

- Winnike JH, Wei X, Knagge KJ, Colman SD, Gregory SG, Zhang X. Comparison of GC-MS and GC×GC-MS in the analysis of human serum samples for biomarker discovery. J Proteome Res. 2015 Apr 3;14(4):1810-7. Epub 2015 Mar 16. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Luiz Antonio Fonseca de Godoy, Ronei Jesus Poppi, Márcio Pozzobon Pedroso, Fabio Augusto, Leandro Wang Hantao, GCxGC-FID for Qualitative and Quantitative Analysis of Perfumes, LCGC Europe, 2010, 23, 8, 430 – 438.

- Alessandro Di Giorgi, Giuseppe Basile, Francesco Bertola, Francesco Tavoletta, Francesco Paolo Busardò, Anastasio Tini, A green analytical method for the simultaneous determination of 17 perfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) in human serum and semen by ultra-performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (UPLC-MS/MS), Journal of Pharmaceutical and Biomedical Analysis, 2024, 246, 116203. [CrossRef]

- Yanwei Liu, Xingwang Hou, Xiaoying Li, Jiyan Liu, Guibin Jiang, Simultaneous determination of 19 bromophenols by gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC-MS) after derivatization, Talanta, 2024, 274, 126015. [CrossRef]

- Jun Hu, Yina Ba, Zhifeng Pan, Xiaogang Li, Simultaneous determination of 50 antibiotic residues in plasma by HPLC–MS/MS, Heliyon, 2024, 10, 24, e40629. [CrossRef]

- Lei Zhao, Zi Lin, Duan Ju, Jiayan Ni, Yuxuan Ma, Bin Chen, Xiaozhou Li, Congcong Sun, Jianqiong Zheng, Hongping Zhang, Shike Hou, Penghui Li, Shanjun Song, Liqiong Guo, Simultaneous determination of multiple endocrine disrupting chemicals in human amniotic fluid samples by solid phase extraction coupled with liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS), Talanta, 2025, 293, 128088. [CrossRef]

- Mahdiyeh Otoukesh, Claudia Simarro-Gimeno, Félix Hernández, Elena Pitarch, Simultaneous LC-MS/MS determination of multi-class emerging contaminants in an orange plant system, Environmental Nanotechnology, Monitoring & Management, 2025, 23, 101077. [CrossRef]

- Qianqian Deng, Yang Liu, Dan Liu, Ziwei Meng, Xianghong Hao, Development of a design of experiments (DOE) assistant modified QuEChERS method coupled with HPLC-MS/MS simultaneous determination of twelve lipid-soluble pesticides and four metabolites in chicken liver and pork, Journal of Food Composition and Analysis, 2024, 133, 106379. [CrossRef]

- Alejandro García-Juan, Nuria León, Sergio Armenta, Olga Pardo, Development and validation of an analytical method for the simultaneous determination of 12 ergot, 2 tropane, and 28 pyrrolizidine alkaloids in cereal-based food by LC-MS/MS, Food Research International, 2023, 174, 1, 113614. [CrossRef]

- Shunqin Chen, Han Yang, Shan Zhang, Faze Zhu, Shan Liu, Huan Gao, Qing Diao, Wenbo Ding, Yuemeng Chen, Peng Luo, Yubo Liu, Simultaneous determination of 28 illegal drugs in sewage by high throughput online SPE-ISTD-UHPLC-MS/MS, Heliyon, 2024, 10, 6, e27897. [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.R., Park, S., Kim, J.Y. et al. Simultaneous determination of 31 Sulfonamide residues in various livestock matrices using liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. Appl Biol Chem 67, 13 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Trinh, H. T.; Marcussen, H.; Hansen, H. C. B.Screening of inorganic and organic contaminants in floodwater in paddy fields of Hue and Thanh Hoa in Vietnam. Environ. Sci. Pollut Res. 2017, 24 (8), 7348– 7358,. [CrossRef]

- Chau, H. T. C.; Kadokami, K.; Duong, H. T.; Kong, L.; Nguyen, T. T.; Nguyen, T. Q.; Ito, Y. Occurrence of 1153 organic micropollutants in the aquatic environment of Vietnam. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2018, 25, 7147– 7156,. [CrossRef]

- Chao Ji, Li Xiao, Xingyu Wang, Marti Z. Hua, Yifeng Wu, Yifan Wang, Zhiqiang Wu, Xiahong He, Dunming Xu, Wenjie Zheng, and Xiaonan Lu, Simultaneous Determination of 147 Pesticide Residues in Traditional Chinese Medicines by GC–MS/MS, ACS Omega 2023 8 (31), 28663-28673. [CrossRef]

- WU Zhao-wei,CHEN An-dong,WANG Tie-song,TONG Yan-hua,CONG Luo-luo* ,CHE Bao-quan. Simultaneous Determination of 50 Residual Solvents in Solid Drug Preparations by GC-MS[J]. Chinese Pharmaceutical Journal, 2014, 49(9): 764-768. [CrossRef]

- Yoshida T, Matsunaga I, Oda H. Simultaneous determination of semivolatile organic compounds in indoor air by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry after solid-phase extraction. J Chromatogr A. 2004 Jan 16;1023(2):255-69. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, M.-L., Gao, Y., Wang, X., Han, X. X., & Zhao, B. (2021). Comprehensive Strategy for Sample Preparation for the Analysis of Food Contaminants and Residues by GC–MS/MS: A Review of Recent Research Trends. Foods, 10(10), 2473. [CrossRef]

- Veloo, K. V., & Ibrahim, N. A. S. (2021). Analytical Extraction Methods and Sorbents’ Development for Simultaneous Determination of Organophosphorus Pesticides’ Residues in Food and Water Samples: A Review. Molecules, 26(18), 5495. [CrossRef]

- Duong, T. T., Nguyen, T. T. L., Dinh, T. H. V., Hoang, T. Q., Vu, T. N., Doan, T. O., Dang, T. M. A., Le, T. P. Q., Tran, D. T., Le, V. N., Nguyen, Q. T., Le, P. T., Nguyen, T. K., Pham, T. D., & Bui, H. M. (2021). Auxin production of the filamentous cyanobacterial Planktothricoides strain isolated from a polluted river in Vietnam. Chemosphere, 284, 131242. [CrossRef]

- Alahmad, W., Kaya, S. I., Cetinkaya, A., Varanusupakul, P., & Ozkan, S. A. (2023). Green chemistry methods for food analysis: Overview of sample preparation and determination. Advances in Sample Preparation, 5, 100053. [CrossRef]

- Jayaraj, R., Megha, P., & Sreedev, P. (2016). Review Article. Organochlorine pesticides, their toxic effects on living organisms and their fate in the environment. Interdisciplinary Toxicology, 9(3–4), 90–100. [CrossRef]

- Shekhar, C., Khosya, R., Thakur, K., Mahajan, D., Kumar, R., Kumar, S., & Sharma, A. K. (2024). A systematic review of pesticide exposure, associated risks, and long-term human health impacts. Toxicology Reports, 13, 101840. [CrossRef]

- Mdeni, N. L., Adeniji, A. O., Okoh, A. I., & Okoh, O. O. (2022). Analytical Evaluation of Carbamate and Organophosphate Pesticides in Human and Environmental Matrices: A Review. Molecules, 27(3), 618. [CrossRef]

- Araújo, M. F., Castanheira, E. M. S., & Sousa, S. F. (2023). The Buzz on Insecticides: A Review of Uses, Molecular Structures, Targets, Adverse Effects, and Alternatives. Molecules, 28(8), 3641. [CrossRef]

- Hodoșan, C., Gîrd, C. E., Ghica, M. V., Dinu-Pîrvu, C.-E., Nistor, L., Bărbuică, I. S., Marin, Ștefan-C., Mihalache, A., & Popa, L. (2023). Pyrethrins and Pyrethroids: A Comprehensive Review of Natural Occurring Compounds and Their Synthetic Derivatives. Plants, 12(23), 4022. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen Thi, K.-O., Do, H.-G., Duong, N.-T., Nguyen, T. D., & Nguyen, Q.-T. (2021). Geographical Discrimination of Curcuma longa L. in Vietnam Based on LC-HRMS Metabolomics. Natural Product Communications, 16(10). [CrossRef]

- Ngoc, P. H., An, T. C., Hiep, N. T., Nhu, T. P. H., Hung, L. N., Trung, N. Q., Minh, B. Q., & Van Trung, P. (2023). UHPLC-Q-TOF-MS/MS-guided dereplication to study chemical constituents of Hedera nepalensis leaves in northern Vietnam. Journal of Analytical Science and Technology, 14(1). [CrossRef]

- Le, V. N., Nguyen, Q. T., Nguyen, N. T., Le, T. G., Janda, T., Szalai, G., & RUI, Y.-K. (2021). Simultaneous determination of plant endogenous hormones in green mustard by liquid chromatography – Tandem mass spectrometry. Chinese Journal of Analytical Chemistry, 49(12), 111–117. [CrossRef]

- Hoang, A. Q., Trinh, H. T., Nguyen, H. M. N., Nguyen, T. Q., Nguyen, T. X., Duc, T. V., Nguyen, T. T., Do, T. Q., Minh, T. B., & Tran, T. M. (2022). Assessment of cyclic volatile methyl siloxanes (CVMSs) in indoor dust from different micro-environments in northern and central Vietnam. Environmental Geochemistry and Health, 45(5), 1711–1722. [CrossRef]

- Minh, T. N., Minh, B. Q., Duc, T. H. M., Thinh, P. V., Anh, L. V., Dat, N. T., Nhan, L. V., & Trung, N. Q. (2022). Potential Use of Moringa oleifera Twigs Extracts as an Anti-Hyperuricemic and Anti-Microbial Source. Processes, 10(3), 563. [CrossRef]

- Hai, C. T., Luyen, N. T., Giang, D. H., Minh, B. Q., Trung, N. Q., Chinh, P. T., Hau, D. V., & Dat, N. T. (2023). <i>Atractylodes macrocephala</i> Rhizomes Contain Anti-inflammatory Sesquiterpenes. Chemical and Pharmaceutical Bulletin, 71(6), 451–453. [CrossRef]

- Metcalfe, C. D., Bayen, S., Desrosiers, M., Muñoz, G., Sauvé, S., & Yargeau, V. (2022). Methods for the analysis of endocrine disrupting chemicals in selected environmental matrixes. Environmental Research, 206, 112616. [CrossRef]

- Manh Tri Tran, Thuy Le Minh, Thi Ngoc Anh Nguyen, Trinh Le Thi, Huong Le Quang, Thi Phuong Thao Pham, Quang Trung Nguyen, Determination and distribution of phthalate diesters in plastic bottled beverages collected in Hanoi, Vietnam, VNU Journal of Science: Natural Sciences and Technology, 2018, 34, 4.

- Thang, P.Q., Taniguchi, T., Nabeshima, Y. et al. Distribution of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons concentrations simultaneously obtained in gas, rainwater and particles. Air Qual Atmos Health 7, 273–281 (2014). [CrossRef]

- Thang, P. Q., Taniguchi, T., Nabeshima, Y., Bandow, H., Trung, N. Q., & Takenaka, N. (2014). Distribution of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons concentrations simultaneously obtained in gas, rainwater and particles. Air Quality, Atmosphere & Health, 7(3), 273–281. [CrossRef]

- Sikiti, P., Msagati, T. A. M., Mishra, A. K., & Mamba, B. B. (2012). Simultaneous determination of tetrachloro dibenzo-p-dioxin and poly-aromatic chlorinated biphenyls in aqueous environment using liquid phase microextraction. Physics and Chemistry of the Earth, Parts A/B/C, 50–52, 98–103. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen Xuan, H., Phan Dinh, Q., Nguyen Thi, X., Mai Thi Hong, H., Nguyen Phuc, A., Le Van, N., Bui Quang, M., Nguyen Quang, T., Chu Dinh, B., Nguyen Tien, D., Anh Le Hoang, T., & Vu Duc, N. (2024). Occurrence and Contamination Levels of Polychlorinated Dibenzo- P -Dioxins (PCDDs) and Polychlorinated Dibenzofurans (PCDFs) in Soil and Sediment in the Vicinity of Recycled Metal Casting Villages: A Case Study in Vietnam. Soil and Sediment Contamination: An International Journal, 1–26. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H. X., Nguyen, X. T., Mai, H. T. H., Nguyen, H. T., Vu, N. D., Pham, T. T. P., Nguyen, T. Q., Nguyen, D. T., Duong, N. T., Hoang, A. L. T., Nguyen, T. N., Le, N. V., Dao, H. V., Ngoc, M. T., & Bui, M. Q. (2024). A Comprehensive Evaluation of Dioxins and Furans Occurrence in River Sediments from a Secondary Steel Recycling Craft Village in Northern Vietnam. Molecules, 29(8), 1788. [CrossRef]

- Tran, L. T., Kieu, T. C., Bui, H. M., Nguyen, N. T., Nguyen, T. T. T., Nguyen, D. T., Nguyen, T. Q., Nguyen, H. T. A., Le, T. H., Takahashi, S., Tu, M. B., & Hoang, A. Q. (2021). Polybrominated diphenyl ethers in indoor dusts from industrial factories, offices, and houses in northern Vietnam: Contamination characteristics and human exposure. Environmental Geochemistry and Health, 44(8), 2375–2388. [CrossRef]

- Duong, H. T., Kadokami, K., Shirasaka, H., Hidaka, R., Chau, H. T. C., Kong, L., Nguyen, T. Q., & Nguyen, T. T. (2015). Occurrence of perfluoroalkyl acids in environmental waters in Vietnam. Chemosphere, 122, 115–124. [CrossRef]

- Silvestro, L., Tarcomnicu, I., & Rizea, S. (2012). HPLC-MS/MS of Highly Polar Compounds. In Tandem Mass Spectrometry - Applications and Principles. InTech. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T. P. L., Nguyen, V. T. A., Do, T. T. T., Nguyen Quang, T., Pham, Q. L., & Le, T. T. (2020). Fatty Acid Composition, Phospholipid Molecules, and Bioactivities of Lipids of the Mud Crab Scylla paramamosain. Journal of Chemistry, 2020, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Le, L. H. T., Tran-Lam, T.-T., Nguyen, H. Q., Quan, T. C., Nguyen, T. Q., Nguyen, D. T., & Dao, Y. H. (2021). A study on multi-mycotoxin contamination of commercial cashew nuts in Vietnam. Journal of Food Composition and Analysis, 102, 104066. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen-Quang, T., Bui-Quang, M., & Truong-Ngoc, M. (2021). Rapid Identification of Geographical Origin of Commercial Soybean Marketed in Vietnam by ICP-MS. Journal of Analytical Methods in Chemistry, 2021, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T. Q., Tran-Lam, T.-T., Nguyen, H. Q., Dao, Y. H., & Le, G. T. (2021). Assessment of organic and inorganic arsenic species in Sengcu rice from terraced paddies and commercial rice from lowland paddies in Vietnam. Journal of Cereal Science, 102, 103346. [CrossRef]

- Anh, B. T. K., Minh, N. N., Ha, N. T. H., Kim, D. D., Kien, N. T., Trung, N. Q., Cuong, T. T., & Danh, L. T. (2018). Field Survey and Comparative Study of Pteris Vittata and Pityrogramma Calomelanos Grown on Arsenic Contaminated Lands with Different Soil pH. Bulletin of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology, 100(5), 720–726. [CrossRef]

- Bui, T. K. A., Dang, D. K., Nguyen, T. K., Nguyen, N. M., Nguyen, Q. T., & Nguyen, H. C. (2014). Phytoremediation of heavy metal polluted soil and water in Vietnam. Journal of Vietnamese Environment, 6(1), 47–51. [CrossRef]

- Markus Amann, Zbigniew Klimont, T An Ha, Peter Rafaj, Gregor Kiesewetter, Adriana Gomez Sanabria, Binh Nguyen, TN Thi Thu, Kimminh Thuy, Wolfgang Schöpp, Jens Borken-Kleefeld, L Höglund-Isaksson, Fabian Wagner, Robert Sander, Chris Heyes, Janusz Cofala, Nguyen Quang Trung, Nguyen Tien Dat, Nguyen Ngoc Tung, Future Air Quality in Ha Noi and Northern Vietnam. http://pure.iiasa.ac.at/15803 (2019).

- Truong, A. H., Kim, M. T., Nguyen, T. T., Nguyen, N. T., & Nguyen, Q. T. (2018). Methane, Nitrous Oxide and Ammonia Emissions from Livestock Farming in the Red River Delta, Vietnam: An Inventory and Projection for 2000–2030. Sustainability, 10(10), 3826. [CrossRef]

- Thang, P. Q., Taniguchi, T., Nabeshima, Y., Bandow, H., Trung, N. Q., & Takenaka, N. (2014). Distribution of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons concentrations simultaneously obtained in gas, rainwater and particles. Air Quality, Atmosphere & Health, 7(3), 273–281. [CrossRef]

- Duong, T. T., Nguyen, T. T. L., Dinh, T. H. V., Hoang, T. Q., Vu, T. N., Doan, T. O., Dang, T. M. A., Le, T. P. Q., Tran, D. T., Le, V. N., Nguyen, Q. T., Le, P. T., Nguyen, T. K., Pham, T. D., & Bui, H. M. (2021). Auxin production of the filamentous cyanobacterial Planktothricoides strain isolated from a polluted river in Vietnam. Chemosphere, 284, 131242. [CrossRef]

- Hanh, T. T. H., Anh, D. H., Huong, P. T. T., Thanh, N. V., Trung, N. Q., Cuong, T. V., Mai, N. T., Cuong, N. T., Cuong, N. X., Nam, N. H., & Minh, C. V. (2018). Crinane, augustamine, and β -carboline alkaloids from Crinum latifolium. Phytochemistry Letters, 24, 27–30. [CrossRef]

- Van Cong, P., Anh, H. L. T., Trung, N. Q., Quang Minh, B., Viet Duc, N., Van Dan, N., Trang, N. M., Phong, N. V., Vinh, L. B., Anh, L. T., & Lee, K. Y. (2022). Isolation, structural elucidation and molecular docking studies against SARS-CoV-2 main protease of new stigmastane-type steroidal glucosides isolated from the whole plants of Vernonia gratiosa. Natural Product Research, 37(14), 2342–2350. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, Q., Nguyen, T., Le, V., Nguyen, N., Truong, N., Hoang, M., Pham, T., & Bui, Q. (2023). Towards a Standardized Approach for the Geographical Traceability of Plant Foods Using Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry (ICP-MS) and Principal Component Analysis (PCA). Foods, 12(9), 1848. [CrossRef]

- Darkó, E., Khalil, R., Elsayed, N., Pál, M., Hamow, K. A., Szalai, G., Tajti, J., Nguyen, Q. T., Nguyen, N. T., Le, V. N., & Janda, T. (2019). Factors playing role in heat acclimation processes in barley and oat plants. Photosynthetica, 57(4), 1035–1043. [CrossRef]

- Minh, T. N., Anh, L. V., Trung, N. Q., Minh, B. Q., & Xuan, T. D. (2022). Efficacy of Green Extracting Solvents on Antioxidant, Xanthine Oxidase, and Plant Inhibitory Potentials of Solid-Based Residues (SBRs) of Cordyceps militaris. Stresses, 3(1), 11–21. [CrossRef]

- Le, V. N., Nguyen, Q. T., Nguyen, N. T., Janda, T., Szalai, G., Nguyen, T. D., & Le, T. G. (2021). FOLIAGE APLLIED GIBBERELIC ACID INFLUENCES GROWTH, NUTRIENT CONTENTS AND QUALITY OF LETTUCES (LACTUCA SATIVA L.). The Journal of Animal and Plant Sciences, 31(6), 1720–1727. [CrossRef]

- Dang, T. T., Vo, T. A., Duong, M. T., Pham, T. M., Van Nguyen, Q., Nguyen, T. Q., Bui, M. Q., Syrbu, N. N., & Van Do, M. (2022). Heavy metals in cultured oysters (Saccostrea glomerata) and clams (Meretrix lyrata) from the northern coastal area of Vietnam. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 184, 114140. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T. P. L., Nguyen, V. T. A., Do, T. T. T., Nguyen Quang, T., Pham, Q. L., & Le, T. T. (2020). Fatty Acid Composition, Phospholipid Molecules, and Bioactivities of Lipids of the Mud Crab Scylla paramamosain. Journal of Chemistry, 2020, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Le, L. H. T., Tran-Lam, T.-T., Nguyen, H. Q., Quan, T. C., Nguyen, T. Q., Nguyen, D. T., & Dao, Y. H. (2021). A study on multi-mycotoxin contamination of commercial cashew nuts in Vietnam. Journal of Food Composition and Analysis, 102, 104066. [CrossRef]

- Quang, T. H., Phong, N. V., Anh, L. N., Hanh, T. T. H., Cuong, N. X., Ngan, N. T. T., Trung, N. Q., Nam, N. H., & Minh, C. V. (2020). Secondary metabolites from a peanut-associated fungus Aspergillus niger IMBC-NMTP01 with cytotoxic, anti-inflammatory, and antimicrobial activities. Natural Product Research, 36(5), 1215–1223. [CrossRef]

- Hanh, T. T. H., Hang, L. T. T., Huong Giang, V., Trung, N. Q., Thanh, N. V., Quang, T. H., & Cuong, N. X. (2021). Chemical constituents of Blumea balsamifera. Phytochemistry Letters, 43, 35–39. [CrossRef]

- Janda, T., Lejmel, M. A., Molnár, A. B., Majláth, I., Pál, M., Nguyen, Q. T., Nguyen, N. T., Le, V. N., & Szalai, G. (2020). Interaction between elevated temperature and different types of Na-salicylate treatment in Brachypodium dystachion. PLOS ONE, 15(1), e0227608. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen-Quang, T., Bui-Quang, M., & Truong-Ngoc, M. (2021). Rapid Identification of Geographical Origin of Commercial Soybean Marketed in Vietnam by ICP-MS. Journal of Analytical Methods in Chemistry, 2021, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Hanh, T. T. H., Hang, L. T. T., Huong, P. T. T., Trung, N. Q., Cuong, T. V., Thanh, N. V., Cuong, N. X., Nam, N. H., & Minh, C. V. (2017). Two new guaiane sesquiterpene lactones from the aerial parts of Artemisia vulgaris. Journal of Asian Natural Products Research, 20(8), 752–756. [CrossRef]

- Le-Quang, H., Phuong, T. P. T., Bui-Quang, M., Nguyen-Tien, D., Nguyen-Thanh, T., Nguyen-Ha, M., Shimadera, H., Kondo, A., Luong-Viet, M., & Nguyen-Quang, T. (2022). Comprehensive Analysis of Organic Micropollutants in Fine Particulate Matter in Hanoi Metropolitan Area, Vietnam. Atmosphere, 13(12), 2088. [CrossRef]

- Hanh, T. T. H., Hang, L. T. T., Huong Giang, V., Trung, N. Q., Thanh, N. V., Quang, T. H., & Cuong, N. X. (2021). Chemical constituents of Blumea balsamifera. Phytochemistry Letters, 43, 35–39. [CrossRef]

- Hanh, T. T. H., Anh, D. H., Quang, T. H., Trung, N. Q., Thao, D. T., Cuong, N. T., An, N. T., Cuong, N. X., Nam, N. H., Kiem, P. V., & Minh, C. V. (2019). Scutebarbatolides A-C, new neo-clerodane diterpenoids from Scutellaria barbata D. Don with cytotoxic activity. Phytochemistry Letters, 29, 65–69. [CrossRef]

- Quang Trung, N., Thi Luyen, N., Duc Nam, V., & Tien Dat, N. (2018). Chemical Composition and in Vitro Biological Activities of White Mulberry Syrup during Processing and Storage. Journal of Food and Nutrition Research, 6(10), 660–664. [CrossRef]

- Hanh, T. T. H., Cham, P. T., Anh, D. H., Cuong, N. T., Trung, N. Q., Quang, T. H., Cuong, N. X., Nam, N. H., & Minh, C. V. (2021). Dammarane-type triterpenoid saponins from the flower buds of Panax pseudoginseng with cytotoxic activity. Natural Product Research, 36(17), 4343–4351. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen-Quang, T., Do-Hoang, G., & Truong-Ngoc, M. (2021). Multielement Analysis of Pakchoi (Brassica rapa L. ssp. chinensis) by ICP-MS and Their Classification according to Different Small Geographical Origins. Journal of Analytical Methods in Chemistry, 2021, 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Trung, N. Q., Van Nhan, L., Thao, P. T. P., & Giang, L. T. (2017). Novel draw solutes of iron complexes easier recovery in forward osmosis process. Journal of Water Reuse and Desalination, 8(2), 244–250. [CrossRef]

- Van, Pc. P., Ngo Van, H., Quang, M. B., Duong Thanh, N., Nguyen Van, D., Thanh, T. D., Tran Minh, N., Thi Thu, H. N., Quang, T. N., Thao Do, T., Thanh, L. P., Do Thi Thu, H., & Le Tuan, A. H. (2023). Stigmastane-type steroid saponins from the leaves of Vernonia amygdalina and their α -glucosidase and xanthine oxidase inhibitory activities. Natural Product Research, 38(4), 601–606. [CrossRef]

- Minh, T. N., Minh, B. Q., Duc, T. H. M., Thinh, P. V., Anh, L. V., Dat, N. T., Nhan, L. V., & Trung, N. Q. (2022). Potential Use of Moringa oleifera Twigs Extracts as an Anti-Hyperuricemic and Anti-Microbial Source. Processes, 10(3), 563. [CrossRef]

- Quang, T. H., Phong, N. V., Anh, D. V., Hanh, T. T. H., Cuong, N. X., Ngan, N. T. T., Trung, N. Q., Oh, H., Nam, N. H., & Minh, C. V. (2021). Bioactive secondary metabolites from a soybean-derived fungus Aspergillus versicolor IMBC-NMTP02. Phytochemistry Letters, 45, 93–99. [CrossRef]

- Bui, M. Q., Quan, T. C., Nguyen, Q. T., Tran-Lam, T.-T., & Dao, Y. H. (2022). Geographical origin traceability of Sengcu rice using elemental markers and multivariate analysis. Food Additives & Contaminants: Part B, 15(3), 177–190. [CrossRef]

- Thang, P. Q., Muto, Y., Maeda, Y., Trung, N. Q., Itano, Y., & Takenaka, N. (2016). Increase in ozone due to the use of biodiesel fuel rather than diesel fuel. Environmental Pollution, 216, 400–407. [CrossRef]

- Hanh, T. T. H., Anh, L. N., Trung, N. Q., Quang, T. H., Anh, D. H., Cuong, N. X., Nam, N. H., & Van Minh, C. (2021). Cytotoxic phenolic glycosides from the seeds of Senna tora. Phytochemistry Letters, 45, 190–194. [CrossRef]

- Trung, N. Q., Dat, N. T., Anh, H. N., Tung, Q. N., Nguyen, V. T. H., Van, H. N. B., Van, N. M. N., & Minh, T. N. (2024). Substrate Influence on Enzymatic Activity in Cordyceps militaris for Health Applications. Chemistry, 6(4), 517–530. [CrossRef]

- Bach, M. X., Minh, T. N., Anh, D. T. N., Anh, H. N., Anh, L. V., Trung, N. Q., Minh, B. Q., & Xuan, T. D. (2022). Protection and Rehabilitation Effects of Cordyceps militaris Fruit Body Extract and Possible Roles of Cordycepin and Adenosine. Compounds, 2(4), 388–403. [CrossRef]

- Tung, N. N., Hung, T. T., Trung, N. Q., & Giang, L. T. (2019). Symmetrical Fatty Dialkyl Carbonates as Potential Green Phase Change Materials: Synthesis and Characterisation. Russian Journal of General Chemistry, 89(7), 1513–1518. [CrossRef]

- Thang, P. Q., Maeda, Y., Trung, N. Q., & Takenaka, N. (2014). Low molecular weight methyl ester in diesel/waste cooking oil biodiesel blend exhausted gas. Fuel, 117, 1170–1171. [CrossRef]

- Minh, T. N., Anh, L. V., Trung, N. Q., Minh, B. Q., & Xuan, T. D. (2022). Efficacy of Green Extracting Solvents on Antioxidant, Xanthine Oxidase, and Plant Inhibitory Potentials of Solid-Based Residues (SBRs) of Cordyceps militaris. Stresses, 3(1), 11–21. [CrossRef]

- Trung, N. Q., Quyen, P. D. T., Ngoc, N. T. T., & Minh, T. N. (2024). Diversity of Host Species and Optimized Cultivation Practices for Enhanced Bioactive Compound Production in Cordyceps militaris. Applied Sciences, 14(18), 8418. [CrossRef]

- Ngoc, T., Thinh, P., Mui, D., Uyen, L., Ngan, N., Tran, N., Khang, P., Huy, L., Minh, T., & Trung, N. (2024). Influences of Fermentation Conditions on the Chemical Composition of Red Dragon Fruit (Hylocereus polyrhizus) Wine. Beverages, 10(3), 61. [CrossRef]

- Duong Thanh, N., Tran Thi, H., Nguyen Quang, T., Nguyen Van, H., Hoang Nguyen, G., Nguyen Huu, Q., & Tran Son, T. (2023). Performance evaluation of multiple particulate matter monitoring instruments under higher temperatures and relative humidity in Southeast Asia and design of an affordable monitoring instrument (ManPMS). Instrumentation Science & Technology, 51(6), 660–680. [CrossRef]

- Cong, P. V., Anh, H. L. T., Vinh, L. B., Han, Y. K., Trung, N. Q., Minh, B. Q., Duc, N. V., Ngoc, T. M., Hien, N. T. T., Manh, H. D., Lien, L. T., & Lee, K. Y. (2023). Alpha-Glucosidase Inhibitory Activity of Saponins Isolated from Vernonia gratiosa Hance. Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology, 33(6), 797–805. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T. N., Trinh, H. T., Hoang, T. M., Van Le, N., Bui, M. Q., & Nguyen, T. Q. (2022). Experimental investigation into the room thermoregulation efficiency in tropical climate of novel green phase change material eutectic mixture. Journal of Thermal Analysis and Calorimetry, 147(20), 11039–11048. [CrossRef]

- Doncheva, T., Kostova, N., Toshkovska, R., Philipov, S., Vu, N., Nguyen, D., Nguyen, T., Do, G., & Dang, H. (2022). Alkaloids from Pandanus amaryllifolius and Pandanus tectorius from Vietnam and Their Anti-inflammatory Properties. Proceedings of the Bulgarian Academy of Sciences, 75(6), 812–820. [CrossRef]

- Quang, T. H., Anh, L. N., Hanh, T. T. H., Cuong, N. X., Ngan, N. T. T., Trung, N. Q., & Nam, N. H. (2021). Cytotoxic and antimicrobial benzodiazepine and phenolic metabolites from Aspergillus ostianus<scp>IMBC-NMTP03</scp>. Vietnam Journal of Chemistry, 59(5), 660–666. [CrossRef]

- Bui, Q. M., Nguyen, Q. T., Nguyen, T. T., Nguyen, H. M., Phung, T. T., Le, V. A., Truong, N. M., Mac, T. V., Nguyen, T. D., Hoang, L. T. A., Tran, H. M. D., Le, V. N., & Nguyen, M. D. (2024). Multivariate Statistical Analysis for the Classification of Sausages Based on Physicochemical Attributes, Using Attenuated Total Reflectance-Fourier Transform Infrared (ATR-FTIR) and Inductively Coupled Plasma-Mass Spectrometry (ICP-MS). Journal of Analytical Methods in Chemistry, 2024, 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Wieczorek, M. N., Zhou, W., & Pawliszyn, J. (2024). Perspective on sample preparation fundamentals. Advances in Sample Preparation, 10, 100114. [CrossRef]

- Ingle, R. G., Zeng, S., Jiang, H., & Fang, W.-J. (2022). Current developments of bioanalytical sample preparation techniques in pharmaceuticals. Journal of Pharmaceutical Analysis, 12(4), 517–529. [CrossRef]

- Lou, Y., Xu, Q., Chen, J., Yang, S., Zhu, Z., & Chen, D. (2023). Advancements in Sample Preparation Methods for the Chromatographic and Mass Spectrometric Determination of Zearalenone and Its Metabolites in Food: An Overview. Foods, 12(19), 3558. [CrossRef]

- Almeida, C. M. M. (2021). Overview of Sample Preparation and Chromatographic Methods to Analysis Pharmaceutical Active Compounds in Waters Matrices. Separations, 8(2), 16. [CrossRef]

- Kuppusamy, S., Meivelu, M., Praburaman, L., Mujahid Alam, M., Al-Sehemi, A. G., & K, A. (2024). Integrating AI in food contaminant analysis: Enhancing quality and environmental protection. Journal of Hazardous Materials Advances, 16, 100509. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).