Submitted:

12 June 2025

Posted:

13 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results & Discussion

2.1. Genetic Diversity Analysis and Collections Characterization

2.2. Parentage Analysis

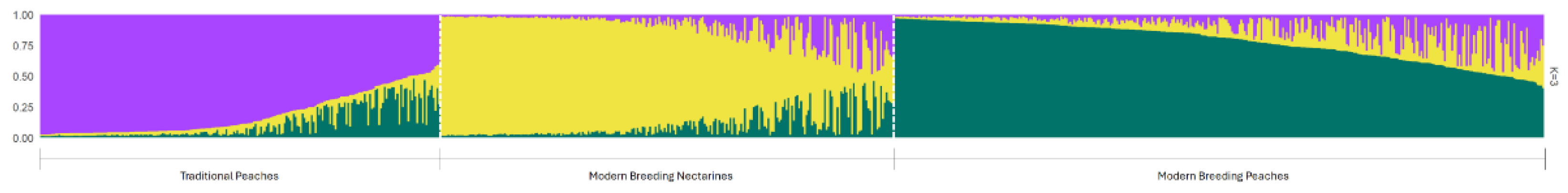

2.3. Population Structure

2.4. SNP and SSR Markers for GenBank Management

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Plant Materials and DNA Extraction

3.2. SSR Analysis

3.3. Population Structure Analysis

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| NGFC CREA | National Fruit Germplasm Collection |

| MAS.PES | Breeding apricot and peach through Marker-Assisted Selection |

| ITPGRFA | International Treaty for Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture |

| GWAS | Genome Wide Association Studies |

| GBS | Genotyping by Sequencing |

| SSRs | Simple Sequence Repeats |

| SNPs | Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms |

| PD | Discrimination Power |

| Ho | observed Heterozygosity |

| He | expected Heterozygosity |

| PIC | Polymorphic Information content |

| PI | Probability of Identity |

| MAF | Minor Allele Frequency |

References

- D. Potter et al., “Phylogeny and classification of Rosaceae,” Plant Systematics and Evolution, vol. 266, no. 1–2, pp. 5–43, Jul. 2007. [CrossRef]

- S. Lee and J. Wen, “A phylogenetic analysis of Prunus and the Amygdaloideae (Rosaceae) using ITS sequences of nuclear ribosomal DNA,” Am J Bot, vol. 88, no. 1, pp. 150–160, Jan. 2001. [CrossRef]

- V. Shulaev et al., “Multiple Models for Rosaceae Genomics,” Plant Physiol, vol. 147, no. 3, pp. 985–1003, Jul. 2008. [CrossRef]

- K. Boudehri, A. Bendahmane, G. Cardinet, C. Troadec, A. Moing, and E. Dirlewanger, “Phenotypic and fine genetic characterization of the D locus controlling fruit acidity in peach,” BMC Plant Biol, vol. 9, no. 1, pp. 1–14, May 2009. [CrossRef]

- S. A. Gilani, R. A. Qureshi, A. M. Khan, and D. Potter, “A molecular phylogeny of selected species of genus Prunus L. (Rosaceae) from Pakistan using the internal transcribed spacer (ITS) spacer DNA,” Afr J Biotechnol, vol. 9, no. 31, pp. 4867–4872, 2010, Accessed: Jun. 10, 2025. [Online]. Available online: https://www.ajol.info/index.php/ajb/article/view/92035.

- I. Verde et al., “The high-quality draft genome of peach (Prunus persica) identifies unique patterns of genetic diversity, domestication and genome evolution,” Nature Genetics 2013 45:5, vol. 45, no. 5, pp. 487–494, Mar. 2013. [CrossRef]

- M. Faust and B. Timon, “Origin and Dissemination of Peach,” Hortic Rev (Am Soc Hortic Sci), pp. 331–379, Nov. 1995. [CrossRef]

- P. Vaccino et al., “Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture: The Role and Contribution of CREA (Italy) within the National Program RGV-FAO,” Agronomy, vol. 14, no. 6, p. 1263, Jun. 2024. [CrossRef]

- R. Van Treuren and T. J. L. Van Hintum, “Marker-assisted reduction of redundancy in germplasm collections: Genetic and economic aspects,” Acta Hortic, vol. 623, pp. 139–149, Jul. 2003. [CrossRef]

- J. C. Bettoni, R. Bonnart, and G. M. Volk, “Challenges in implementing plant shoot tip cryopreservation technologies,” Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult, vol. 144, no. 1, pp. 21–34, Jan. 2021. [CrossRef]

- P. Tripodi et al., “Global range expansion history of pepper (Capsicum spp.) revealed by over 10,000 genebank accessions,” Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, vol. 118, no. 34, p. e2104315118, Aug. 2021. [CrossRef]

- F. Emanuelli et al., “Genetic diversity and population structure assessed by SSR and SNP markers in a large germplasm collection of grape,” BMC Plant Biol, vol. 13, no. 1, pp. 1–17, Mar. 2013. [CrossRef]

- R. van Treuren, H. Kemp, G. Ernsting, B. Jongejans, H. Houtman, and L. Visser, “Microsatellite genotyping of apple (Malus × domestica Borkh.) genetic resources in the Netherlands: Application in collection management and variety identification,” Genet Resour Crop Evol, vol. 57, no. 6, pp. 853–865, Jan. 2010. [CrossRef]

- W. Liang, L. Dondini, P. De Franceschi, R. Paris, S. Sansavini, and S. Tartarini, “Genetic Diversity, Population Structure and Construction of a Core Collection of Apple Cultivars from Italian Germplasm,” Plant Mol Biol Report, vol. 33, no. 3, pp. 458–473, Jun. 2015. [CrossRef]

- L. Lassois et al., “Genetic Diversity, Population Structure, Parentage Analysis, and Construction of Core Collections in the French Apple Germplasm Based on SSR Markers,” Plant Mol Biol Report, vol. 34, no. 4, pp. 827–844, Aug. 2016. [CrossRef]

- B. Larsen, T. B. Toldam-Andersen, C. Pedersen, and M. Ørgaard, “Unravelling genetic diversity and cultivar parentage in the Danish apple gene bank collection,” Tree Genet Genomes, vol. 13, no. 1, pp. 1–12, Feb. 2017. [CrossRef]

- A. Pina, J. Urrestarazu, and P. Errea, “Analysis of the genetic diversity of local apple cultivars from mountainous areas from Aragon (Northeastern Spain),” Sci Hortic, vol. 174, no. 1, pp. 1–9, Jul. 2014. [CrossRef]

- C. M. H. D. C.-E. Denancé, “MUNQ - Malus UNiQue genotype code for grouping apple accessions corresponding to a unique genotypic profile,” 2020.

- B. Larsen et al., “Cultivar fingerprinting and SNP-based pedigree reconstruction in Danish heritage apple cultivars utilizing genotypic data from multiple germplasm collections in the world,” Genet Resour Crop Evol, vol. 72, no. 2, pp. 2397–2411, Feb. 2024. [CrossRef]

- M. J. Aranzana, J. Carbó, and P. Arús, “Microsatellite variability in peach [Prunus persica (L.) Batsch]: Cultivar identification, marker mutation, pedigree inferences and population structure,” Theoretical and Applied Genetics, vol. 106, no. 8, pp. 1341–1352, May 2003. [CrossRef]

- M. J. Aranzana, E. K. Abbassi, W. Howad, and P. Arús, “Genetic variation, population structure and linkage disequilibrium in peach commercial varieties,” BMC Genet, vol. 11, no. 1, pp. 1–11, Jul. 2010. [CrossRef]

- X. wei Li et al., “Peach genetic resources: Diversity, population structure and linkage disequilibrium,” BMC Genet, vol. 14, no. 1, pp. 1–16, Sep. 2013. [CrossRef]

- M. Méndez, G. Rojas, C. Muñoz, G. Lemus, and P. Hinrichsen, “Identification of a minimal microsatellite marker panel for the fingerprinting of peach and nectarine cultivars,” 2008.

- M. Bouhadida, M. Á. Moreno, M. J. Gonzalo, J. M. Alonso, and Y. Gogorcena, “Genetic variability of introduced and local Spanish peach cultivars determined by SSR markers,” Tree Genet Genomes, vol. 7, no. 2, pp. 257–270, Apr. 2011. [CrossRef]

- D. J. Chavez, T. G. Beckman, D. J. Werner, and J. X. Chaparro, “Genetic diversity in peach [prunus persica (l.) batsch] at the university of florida: past, present and future,” Tree Genet Genomes, vol. 10, no. 5, pp. 1399–1417, Oct. 2014. [CrossRef]

- Z. J. Shen, R. J. Ma, Z. X. Cai, and M. L. Yu, “Diversity, Population structure, And evolution of local peach cultivars in China identified by simple sequence repeats,” Genetics and Molecular Research, vol. 14, no. 1, pp. 101–117, Jan. 2015. [CrossRef]

- D. Micheletti et al., “Whole-Genome Analysis of Diversity and SNP-Major Gene Association in Peach Germplasm,” PLoS One, vol. 10, no. 9, p. e0136803, Sep. 2015. [CrossRef]

- I. Verde et al., “Development and evaluation of a 9K SNP array for peach by internationally coordinated SNP detection and validation in breeding germplasm.,” PLoS One, vol. 7, no. 4, p. e35668, 2012. [CrossRef]

- K. Cao et al., “Genome-wide association study of 12 agronomic traits in peach,” Nat Commun, vol. 7, no. 1, pp. 1–10, Nov. 2016. [CrossRef]

- J. Guo et al., “An integrated peach genome structural variation map uncovers genes associated with fruit traits,” Genome Biol, vol. 21, no. 1, pp. 1–19, Oct. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Y. Li et al., “Genomic analyses of an extensive collection of wild and cultivated accessions provide new insights into peach breeding history,” Genome Biol, vol. 20, no. 1, pp. 1–18, Feb. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Y. Yu et al., “Population-scale peach genome analyses unravel selection patterns and biochemical basis underlying fruit flavor,” Nature Communications 2021 12:1, vol. 12, no. 1, pp. 1–13, Jun. 2021. [CrossRef]

- F. S. R. M. and C. L. Bassi D, “Progetto ‘MAS.PES‘ per il miglioramento genetico del pesco: criteri di selezione e individuazione ideotipi di riferimento,” Italus Hortus 17 (5), pp. 60–62, 2010.

- B. V. F. J. Paula LA, “Caracterização molecular variabilidade genética entre porta-enxertos de pessegueiro com base em marcadores codominantes,” Pesquisa Agropecuária Brasileira, Brasília., vol. 47, no. 2, pp. 193–199, 2012.

- C. A. E. A. C. P. Z. A. and D. E. Chalak L, “Morphological and molecular characterization of peach accessions (Prunus persica L.) cultivated in Lebanon,” Lebanese Sci. J., vol. 7, no. 2, pp. 23–31, 2003.

- D. J. Chavez, T. G. Beckman, D. J. Werner, and J. X. Chaparro, “Genetic diversity in peach [Prunus persica (L.) Batsch] at the University of Florida: past, present and future,” Tree Genet Genomes, 2014. [CrossRef]

- D. Botstein, R. L. White, M. Skolnick, and R. W. Davis, “Construction of a genetic linkage map in man using restriction fragment length polymorphisms,” Am J Hum Genet, vol. 32, no. 3, p. 314, 1980, Accessed: Jun. 10, 2025. [Online]. Available online: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC1686077/.

- D. Giovannini et al., “Assessment of genetic variability in Italian heritage peach resources from Emilia-Romagna using microsatellite markers,” J Hortic Sci Biotechnol, vol. 87, no. 5, pp. 435–440, 2012. [CrossRef]

- R. Falchi et al., “Three distinct mutational mechanisms acting on a single gene underpin the origin of yellow flesh in peach,” Plant Journal, vol. 76, no. 2, pp. 175–187, 2013. [CrossRef]

- M. Adami et al., “Identifying a Carotenoid Cleavage Dioxygenase (ccd4) Gene Controlling Yellow/White Fruit Flesh Color of Peach,” Plant Mol Biol Report, vol. 31, no. 5, pp. 1166–1175, 2013. [CrossRef]

- K. Cao et al., “Comparative population genomics reveals the domestication history of the peach, Prunus persica, and human influences on perennial fruit crops,” Genome Biol, vol. 15, no. 7, pp. 1–15, Jul. 2014. [CrossRef]

- A. Smykov, O. Fedorova, T. Shishova, and I. Ivashchenko, “Introduction and use of the peach gene pool from China in Nikita Botanical Garden,” Acta Hortic, vol. 1208, pp. 1–6, Aug. 2018. [CrossRef]

- R. Testolin et al., “Microsatellite DNA in peach (Prunus persica L. Batsch) and its use in fingerprinting and testing the genetic origin of cultivars,” https://doi.org/10.1139/g00-010, vol. 43, no. 3, pp. 512–520, Jun. 2011. [CrossRef]

- R. Falchi et al., “Three distinct mutational mechanisms acting on a single gene underpin the origin of yellow flesh in peach,” The Plant Journal, vol. 76, no. 2, pp. 175–187, Oct. 2013. [CrossRef]

- W. R. Okie, Handbook of peach and nectarine varieties. National TechnicaU.S. Dept. of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service; National Technical Information Service, distributor, 1998.

- E. Vendramin et al., “A Unique Mutation in a MYB Gene Cosegregates with the Nectarine Phenotype in Peach.,” PLoS One, vol. 9, no. 3, p. e90574, 2014. [CrossRef]

- R. Scorza, S. A. Mehlenbacher, and G. W. Lightner, “Inbreeding and Coancestry of Freestone Peach Cultivars of the Eastern United States and Implications for Peach Germplasm Improvement,” Journal of the American Society for Horticultural Science, vol. 110, no. 4, pp. 547–552, Jul. 1985. [CrossRef]

- AA.VV., Atlante dei fruttiferi autoctoni italiani, 2016th ed., vol. I-II–III. Roma: CREA Olivicoltura, Frutticoltura e Agrumicoltura & MIPAAF, 2016.

- C. Jouy et al., “Management of peach tree reference collections: Ongoing research & development program relevant to the community plant variety rights protection system,” Acta Hortic, vol. 962, pp. 51–56, Oct. 2012. [CrossRef]

- M. J. Hayden, T. M. Nguyen, A. Waterman, and K. J. Chalmers, “Multiplex-Ready PCR: A new method for multiplexed SSR and SNP genotyping,” BMC Genomics, vol. 9, no. 1, pp. 1–12, Feb. 2008. [CrossRef]

- I. Eduardo et al., “QTL analysis of fruit quality traits in two peach intraspecific populations and importance of maturity date pleiotropic effect,” Tree Genet Genomes, vol. 7, no. 2, pp. 323–335, Apr. 2011. [CrossRef]

- F. J. Rohlf, “NTSYS-pc, Numerical Taxonomy and Multivariate Analysis System. Ver. 1. 80,” 1994, Exeter Software, New York.

- M. Lynch, “The similarity index and DNA fingerprinting.,” Mol Biol Evol, vol. 7, no. 5, pp. 478–484, Sep. 1990. [CrossRef]

- S. T. Kalinowski, M. L. Taper, and T. C. Marshall, “Revising how the computer program CERVUS accommodates genotyping error increases success in paternity assignment,” Mol Ecol, vol. 16, no. 5, pp. 1099–1106, Mar. 2007. [CrossRef]

- R. Peakall and P. E. Smouse, “GenAlEx 6.5: genetic analysis in Excel. Population genetic software for teaching and research—an update,” Bioinformatics, vol. 28, no. 19, pp. 2537–2539, Oct. 2012. [CrossRef]

- J. K. Pritchard, M. Stephens, and P. Donnelly, “Inference of Population Structure Using Multilocus Genotype Data,” Genetics, vol. 155, no. 2, pp. 945–959, Jun. 2000. [CrossRef]

- Y. L. Li and J. X. Liu, “StructureSelector: A web-based software to select and visualize the optimal number of clusters using multiple methods,” Mol Ecol Resour, vol. 18, no. 1, pp. 176–177, Jan. 2018. [CrossRef]

- M. Jakobsson and N. A. Rosenberg, “CLUMPP: a cluster matching and permutation program for dealing with label switching and multimodality in analysis of population structure,” Bioinformatics, vol. 23, no. 14, pp. 1801–1806, Jul. 2007. [CrossRef]

- R. M. Francis, “pophelper: an R package and web app to analyse and visualize population structure,” Mol Ecol Resour, vol. 17, no. 1, pp. 27–32, Jan. 2017. [CrossRef]

| BPPCT017 | BPPCT001 | UDP-005 | BPPCT007 | BPPCT038 | UDP-412 | EPPCU5176 | BPPCT015 | CPDCT045 | UDP-409 | CPPCT006 | UDP-022 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| size | 134 | 162 | 149 | 157 | 119 | 128 | 183 | 171 | 161 | 152 | 208 | 147 |

| f | 0,001 | 0,009 | 0,001 | 0,001 | 0,001 | 0,001 | 0,001 | 0,001 | 0,001 | 0,12 | 0,291 | 0,001 |

| size | 149 | 166 | 157 | 161 | 121 | 133 | 185 | 178 | 167 | 156 | 210 | 157 |

| f | 0,012 | 0,001 | 0,001 | 0,025 | 0,002 | 0,001 | 0,001 | 0,001 | 0,001 | 0,001 | 0,001 | 0,173 |

| size | 151 | 170 | 162 | 163 | 123 | 143 | 191 | 180 | 172 | 158 | 216 | 159 |

| f | 0,026 | 0,004 | 0,001 | 0,001 | 0,594 | 0,003 | 0,001 | 0,016 | 0,003 | 0,742 | 0,001 | 0,002 |

| size | 155 | 176 | 166 | 165 | 125 | 145 | 193 | 182 | 174 | 160 | 218 | 165 |

| f | 0,001 | 0,076 | 0,002 | 0,001 | 0,038 | 0,003 | 0,001 | 0,022 | 0,024 | 0,101 | 0,157 | 0,143 |

| size | 157 | 178 | 168 | 167 | 127 | 150 | 197 | 186 | 176 | 162 | 220 | 167 |

| f | 0,002 | 0,007 | 0,004 | 0,001 | 0,018 | 0,004 | 0,505 | 0,257 | 0,438 | 0,004 | 0,544 | 0,15 |

| size | 159 | 182 | 170 | 169 | 129 | 152 | 199 | 188 | 178 | 168 | 222 | 169 |

| f | 0,017 | 0,102 | 0,001 | 0,001 | 0,061 | 0,262 | 0,026 | 0,006 | 0,124 | 0,001 | 0,002 | 0,021 |

| size | 161 | 184 | 172 | 171 | 131 | 154 | 201 | 190 | 180 | 170 | 224 | 171 |

| f | 0,539 | 0,152 | 0,001 | 0,001 | 0,006 | 0,09 | 0,229 | 0,02 | 0,406 | 0,001 | 0,002 | 0,509 |

| size | 163 | 186 | 174 | 175 | 133 | 156 | 203 | 198 | 182 | 179 | 226 | 173 |

| f | 0,007 | 0,072 | 0,185 | 0,044 | 0,021 | 0,142 | 0,001 | 0,614 | 0,002 | 0,005 | 0,001 | 0,002 |

| size | 165 | 188 | 176 | 177 | 135 | 158 | 205 | 200 | 184 | 181 | 228 | |

| f | 0,011 | 0,439 | 0,066 | 0,437 | 0,25 | 0,448 | 0,022 | 0,034 | 0,001 | 0,021 | 0,002 | |

| size | 167 | 190 | 178 | 179 | 137 | 160 | 207 | 202 | 186 | 183 | ||

| f | 0,003 | 0,058 | 0,004 | 0,067 | 0,004 | 0,038 | 0,209 | 0,026 | 0,001 | 0,004 | ||

| size | 169 | 192 | 187 | 181 | 139 | 162 | 209 | 206 | ||||

| f | 0,009 | 0,06 | 0,004 | 0,01 | 0,005 | 0,005 | 0,004 | 0,003 | ||||

| size | 171 | 194 | 189 | 183 | 141 | 164 | 211 | |||||

| f | 0,004 | 0,01 | 0,104 | 0,408 | 0,001 | 0,004 | 0,001 | |||||

| size | 173 | 196 | 191 | 186 | 149 | |||||||

| f | 0,001 | 0,002 | 0,611 | 0,002 | 0,001 | |||||||

| size | 175 | 198 | 193 | 198 | ||||||||

| f | 0,001 | 0,006 | 0,015 | 0,001 | ||||||||

| size | 177 | 200 | 195 | |||||||||

| f | 0,013 | 0,003 | 0,001 | |||||||||

| size | 179 | |||||||||||

| f | 0,343 | |||||||||||

| size | 181 | |||||||||||

| f | 0,009 | |||||||||||

| size | 183 | |||||||||||

| f | 0,001 | |||||||||||

| size | 185 | |||||||||||

| f | 0,001 |

| Locus | N | Na | Ne | I | Ho | He | F | PIC | PD | Nra |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BPPCT001 | 885 | 15 | 4,1 | 1,81 | 0,5 | 0,76 | 0,34 | 0,73 | 0,92 | 8 |

| BPPCT007 | 935 | 14 | 2,74 | 1,24 | 0,5 | 0,64 | 0,21 | 0,57 | 0,8 | 11 |

| BPPCT015 | 871 | 11 | 2,24 | 1,15 | 0,37 | 0,55 | 0,34 | 0,5 | 0,75 | 9 |

| BPPCT017 | 939 | 19 | 2,44 | 1,23 | 0,46 | 0,59 | 0,22 | 0,52 | 0,76 | 17 |

| BPPCT038 | 949 | 13 | 2,38 | 1,21 | 0,44 | 0,58 | 0,24 | 0,53 | 0,77 | 10 |

| CPDCT045 | 909 | 10 | 2,69 | 1,13 | 0,49 | 0,63 | 0,22 | 0,55 | 0,78 | 7 |

| CPPCT006 | 921 | 9 | 2,47 | 1,03 | 0,44 | 0,6 | 0,26 | 0,53 | 0,77 | 6 |

| EPPCU5176 | 948 | 12 | 2,84 | 1,24 | 0,5 | 0,65 | 0,23 | 0,59 | 0,82 | 9 |

| UDP-005 | 841 | 15 | 2,36 | 1,21 | 0,4 | 0,58 | 0,3 | 0,54 | 0,78 | 11 |

| UDP-022 | 894 | 8 | 3,01 | 1,32 | 0,42 | 0,67 | 0,38 | 0,63 | 0,85 | 4 |

| UDP-409 | 926 | 10 | 1,74 | 0,88 | 0,32 | 0,42 | 0,24 | 0,4 | 0,64 | 7 |

| UDP-412 | 932 | 12 | 3,35 | 1,45 | 0,53 | 0,7 | 0,24 | 0,66 | 0,87 | 8 |

| Sample/SSR | BPPCT001 | BPPCT007 | BPPCT015 | BPPCT017 | BPPCT038 | CPDCT045 | CPPCT006 | EPPCU5176 | UDP-005 | UDP-022 | UDP-409 | UDP-412 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AB/6 | 170 190 | 169 177 | - - | 157 161 | 125 129 | 178 184 | 220 224 | 205 205 | 162 174 | 167 167 | 158 168 | 154 154 |

| Chui_Huang_Tao | 182 182 | 177 177 | 186 186 | 151 151 | 131 149 | 176 176 | - - | 193 193 | 157 157 | 165 169 | 181 181 | 152 152 |

| Citation | 162 166 | 171 177 | 198 198 | 161 161 | 123 131 | 176 178 | 220 226 | 185 197 | 191 191 | 165 165 | 158 158 | 152 160 |

| Dourado | 186 188 | 161 177 | 180 180 | 151 165 | 123 127 | 176 178 | 208 220 | 197 207 | 172 191 | 165 167 | 158 158 | 152 158 |

| Ferganensis | 182 182 | 183 183 | - - | 161 161 | 123 123 | 178 178 | 220 220 | 209 209 | 193 195 | 165 165 | 183 183 | 162 162 |

| Fiorenza | 188 188 | 177 183 | 198 198 | 161 185 | 123 123 | 180 180 | 220 220 | 197 205 | 191 191 | 165 171 | 152 158 | 158 160 |

| Glowin_Star | 170 190 | 179 179 | 198 198 | 134 169 | 123 123 | 176 186 | 220 224 | 207 207 | 174 189 | 165 165 | 160 183 | 156 156 |

| IF_817023 | 162 162 | - - | 186 186 | 155 161 | 123 123 | 167 180 | 216 228 | 191 191 | 174 174 | - - | 183 183 | 128 133 |

| P1/12 | 186 186 | 177 198 | 198 198 | 161 161 | 123 123 | 176 176 | 220 220 | 197 207 | 176 176 | 157 157 | 158 158 | 156 158 |

| P5/645 | 182 188 | 161 177 | 186 186 | 177 179 | 135 135 | 176 180 | 208 208 | 203 207 | 189 191 | 165 171 | 158 158 | 158 158 |

| Queen_Ruby | 176 184 | 179 183 | 198 200 | 161 161 | 123 123 | 178 180 | 208 220 | 201 211 | 189 191 | 165 171 | 158 158 | 152 156 |

| Red_Robin | 182 182 | 165 175 | 198 198 | 149 179 | 129 135 | 176 180 | 208 208 | 197 201 | 191 191 | 165 171 | 152 158 | 152 158 |

| Shan_Dong | 184 184 | 161 177 | 198 198 | 149 179 | 123 141 | 176 180 | - - | 197 199 | 174 191 | - - | 158 181 | 152 158 |

| XIAGUANG_a | 186 186 | 167 183 | 198 198 | 159 161 | 123 123 | 176 176 | 208 208 | 201 201 | 174 176 | 171 171 | 158 160 | - - |

| Type of Pedigree | N° | N Match | % Match |

|---|---|---|---|

| P1xP2 | 47 | 16 | 34.0 |

| PxSelf | 14 | 5 | 35.7 |

| P op | 59 | 42 | 71.2 |

| Clones | 29 | 17 | 55.2 |

| N° TOT | 149 | 80 | 53.0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).