1. Introduction

The advent of Large Language Models (LLMs) such as GPT-3 [

1], PaLM [

2], and LLaMA [

3] has transformed natural language understanding and reasoning tasks. LLMs can generate high-quality text, answer questions, solve mathematical problems, and perform multi-step reasoning from natural prompts. These capabilities have given rise to two prominent and converging research directions: LLM inference, which focuses on enhancing reasoning and decision-making, and LLM-based feature generation, which explores how LLMs can construct or refine input representations for downstream tasks.

Inference-focused techniques have evolved from simple scaling to structured prompting strategies. Chain-of-Thought (CoT) [

4] prompting enables step-by-step reasoning, significantly improving performance in arithmetic and logic tasks. Tree of Thoughts (ToT) [

5] generalizes this concept by exploring multiple reasoning paths in a tree structure. Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) [

6] incorporates document retrieval to provide factual grounding, while extensions like Retrieval-Augmented Thought Trees (RATT) [

8] and Thought Space Explorer (TSE) [

9] integrate search-based and verification-aware mechanisms to improve depth and accuracy in reasoning.

Simultaneously, feature generation has become critical for adapting LLMs to specific domains. Text-Informed Feature Generation (TIFG) [

10] uses RAG to produce domain-relevant features. Dynamic and Adaptive Feature Generation (DAFG) [

11] deploys LLM agents that iteratively improve features based on task-specific feedback. Transformer-based Feature Weighting (TFWT) [

12] applies attention mechanisms to emphasize important features in structured data.

Auxiliary strategies have further enhanced LLM utility. Data augmentation [

13] methods improve generalization by creating diverse training examples using approaches like SMOTE [

14], Mixup [

15], or GANs. In low-data environments, Prototypical Reward Modeling (Proto-RM) [

16] has been shown to strengthen RLHF pipelines by modeling feedback more effectively than scalar reward functions.

In this survey, we study and categorize ten influential works across these categories. We organize these developments into a unified taxonomy and compare them across key dimensions such as scalability, interpretability, and applicability. This structure forms the foundation for a comprehensive analysis of current techniques and emerging trends in reasoning-aware, adaptable LLM systems.

2. Taxonomy and Methodological Foundations

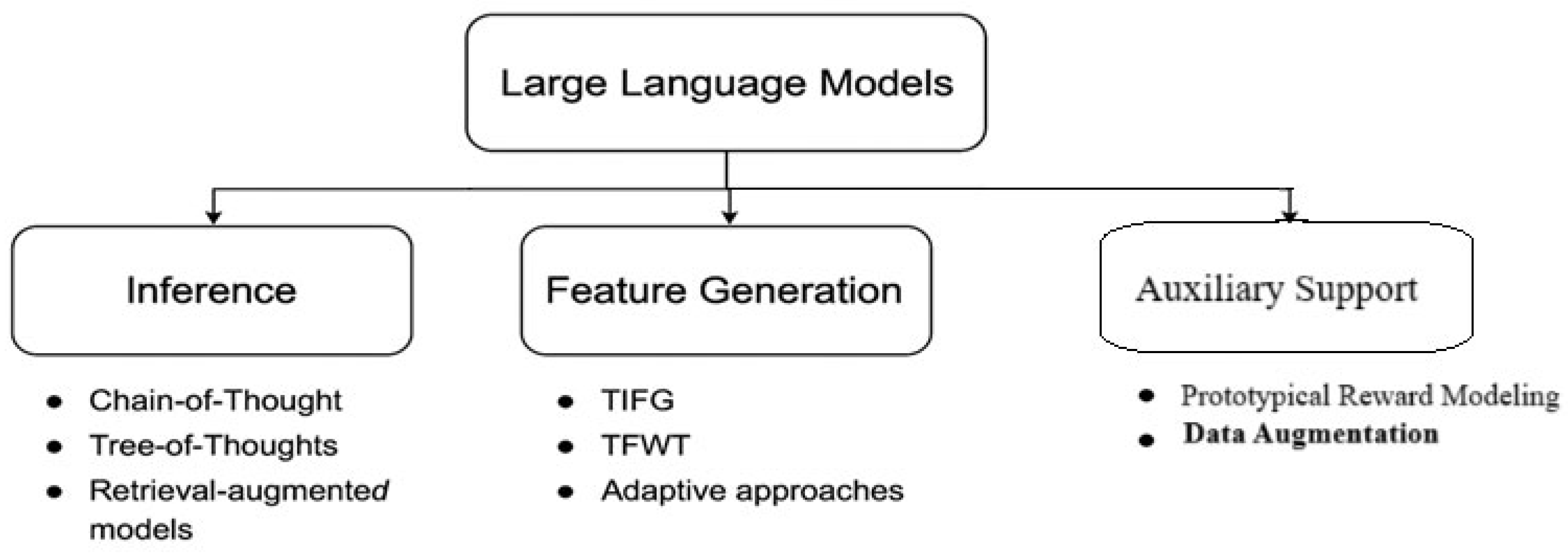

As illustrated in

Figure 1, current LLM-based research can be broadly divided into three major areas: inference, feature generation and auxiliary support strategies. Inference methods guide how LLMs reason through prompts, while feature generation methods enable LLMs to construct, modify, or prioritize inputs for downstream tasks. Additionally, auxiliary support strategies—such as data augmentation and reward modeling—enhance these core capabilities. This section presents a structured taxonomy and introduces foundational concepts that will be examined in detail in subsequent sections.

2.1. Inference Techniques

Chain-of-Thought (CoT): This method prompts LLMs to solve tasks by breaking them down into a sequence of intermediate reasoning steps. For example, instead of giving a direct answer to a math problem, the model lists each step—mirroring human problem-solving. This technique improves performance in arithmetic, logic, and symbolic tasks by reducing cognitive load and improving interpretability.

Tree of Thoughts (ToT): ToT extends CoT by enabling the LLM to explore multiple reasoning paths in a tree structure. Each branch of the tree represents a different line of thought, and a scoring function helps select the most promising path. This allows for backtracking, pruning, and decision revision—similar to strategies used in heuristic search.

Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG): RAG augments the model's generative capabilities by combining text generation with document retrieval. When responding to a prompt, the system retrieves relevant passages from an external corpus, which are then included in the model's input. This improves factual grounding and mitigates hallucinations in knowledge-intensive tasks.

Retrieval-Augmented Thought Trees (RATT): RATT fuses RAG’s document retrieval with ToT’s multi-path reasoning. It evaluates multiple lines of reasoning while grounding each with factual context from retrieved materials. This architecture is particularly useful in tasks requiring both deep reasoning and factual accuracy.

Thought Space Explorer (TSE): TSE encourages the LLM to generate and explore a variety of intermediate reasoning paths. It creates a graph of thought nodes—each representing a potential hypothesis or intermediate step. This graph is then expanded and pruned based on scoring mechanisms, improving reasoning depth and diversity.

2.2. Feature Generation Techniques

Text-Informed Feature Generation (TIFG): TIFG enables LLMs to generate task-specific features from raw input data using context retrieved from external knowledge sources. It combines structured prompting with retrieval mechanisms to extract relevant patterns or indicators (e.g., risk scores, category markers) and convert them into machine-readable features.

Transformer-based Feature Weighting (TFWT): TFWT leverages the attention mechanism inherent in transformer models to assign weights to input features. These weights reflect the relative importance of each feature in the prediction task. The model adapts weights at inference time, allowing it to handle heterogeneous or evolving input data distributions.

Dynamic and Adaptive Feature Generation (DAFG): DAFG uses multiple LLM agents to iteratively propose and refine candidate features. Feedback from downstream model performance (e.g., accuracy, F1 score) is used to accept, reject, or improve features. This creates a closed-loop system where feature design evolves over time.

2.3. Auxiliary Support Strategies

Support strategies enhance the efficiency and generalizability of LLMs:

Prototypical Reward Modeling (Proto-RM): Proto-RM addresses the data inefficiency in RLHF by clustering similar user feedback examples and learning reward functions from representative prototypes. This method improves generalization in low-resource settings and ensures stable reward gradients.

Data Augmentation: This class of techniques enhances model robustness by expanding the training dataset using synthetic examples. Classic approaches include SMOTE (which generates new data points for minority classes), Mixup (which blends inputs and labels), and GAN-based augmentation (which generates synthetic samples via adversarial networks). These are especially useful in addressing data imbalance and improving generalization.

3. Method Analysis and Technical Deep Dive

This section provides an in-depth analysis of ten representative methods in the domain of LLM-based inference and feature generation. Each method is examined through multiple lenses—its motivation, underlying mechanism, input/output structure, strengths, limitations, and evaluation strategy. This layered breakdown not only clarifies the design principles of each approach but also highlights their applicability to real-world problems. By comparing these methods systematically, we aim to provide readers with a nuanced understanding of the diverse ways in which LLMs are being adapted to reason, generate features, and interact with data-driven pipelines.

3.1. Chain-of-Thought (CoT)

Chain-of-Thought prompting was introduced to enhance the reasoning capabilities of LLMs, particularly for complex tasks such as multi-step arithmetic and symbolic reasoning. Instead of producing an answer in a single step, CoT encourages the model to generate a sequence of intermediate steps that lead to the final answer. This mirrors the human approach to problem-solving, where each logical move builds on the previous one. The input is a standard prompt, and the output includes a reasoning trail followed by the conclusion. This technique significantly improves accuracy on datasets like GSM8K and SVAMP. While it enhances interpretability and performance, it may also propagate errors if the early steps in the reasoning chain are incorrect.

3.2. Tree of Thoughts (ToT)

Tree of Thoughts extends CoT by introducing a structured tree search mechanism. Instead of following a single reasoning path, ToT enables the LLM to explore multiple branches of reasoning in parallel. Each node in the tree represents a possible intermediate thought, and a scoring function is used to evaluate and select promising branches while pruning less relevant ones. This architecture allows the model to backtrack and revise decisions when a reasoning path appears suboptimal. ToT excels in tasks that benefit from exploratory problem-solving, such as logic puzzles (e.g., Game of 24). However, its main limitation lies in its high computational cost and inference latency, making it challenging to deploy at scale.

3.3. Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG)

RAG combines document retrieval with generative modeling to improve factual consistency in outputs. Upon receiving a query, the model first retrieves relevant documents from an external corpus and incorporates this retrieved context into the prompt before generating the final response. This hybrid design enhances the model’s ability to answer knowledge-intensive questions without hallucination. RAG was evaluated on benchmarks such as Natural Questions and TriviaQA, where it consistently outperformed standard generative models like BART. However, its effectiveness is highly dependent on the quality and relevance of the retrieved documents, and suboptimal retrieval can limit its performance.

3.4. Retrieval-Augmented Thought Trees (RATT)

RATT merges the retrieval capabilities of RAG with the structured reasoning of ToT. It constructs multiple lines of reasoning, each supported by evidence from retrieved documents. For each node in the reasoning tree, relevant documents are fetched and validated before allowing the reasoning to proceed. This architecture ensures both logical depth and factual grounding, making it suitable for tasks like StrategyQA that require justification and evidence. Although RATT provides robust and interpretable outputs, it is computationally expensive and complex to implement due to the dual-layered design of retrieval and tree traversal.

3.5. Thought Space Explorer (TSE)

Thought Space Explorer focuses on maximizing reasoning diversity and coverage. It generates a graph of intermediate thoughts (nodes), where each node represents a different hypothesis or reasoning step. These nodes are expanded based on plausible continuations, and the system uses scoring mechanisms to prioritize and prune paths. This exploration allows the model to discover less obvious but valid solutions, especially in tasks involving ambiguity or multiple correct answers, such as commonsense QA. While TSE enhances the breadth of reasoning, it risks producing redundant or overly speculative outputs, making pruning and scoring functions essential to its effectiveness.

3.6. Text-Informed Feature Generation (TIFG)

TIFG is designed to extract interpretable, domain-specific features from structured and unstructured input using LLM prompting and document retrieval. Given a dataset and a task objective, the model retrieves relevant contextual information (e.g., guidelines, domain examples) and uses structured prompts to generate new features—such as risk scores or category labels. These features are machine-readable and align with domain-specific semantics. TIFG has shown effectiveness in clinical applications where explainability is crucial. However, its success hinges on the quality of the retrieval and the specificity of the prompt templates, which require careful tuning.

3.7. Transformer-Based Feature Weighting (TFWT)

TFWT utilizes attention mechanisms in transformer models to assign dynamic weights to input features during inference. Each feature's relevance is determined based on its contextual importance to the prediction task, as learned through the attention heads. This method adapts to shifts in data distribution and offers a form of model interpretability by revealing which features influenced the decision. It has been evaluated on tabular datasets like those from the UCI repository. While TFWT enhances adaptability, it is limited by the controversial nature of interpreting attention weights as true explanations.

3.8. Dynamic and Adaptive Feature Generation (DAFG)

DAFG adopts a multi-agent framework where LLMs iteratively propose and refine candidate features. The system incorporates feedback loops that evaluate the quality of generated features based on performance metrics such as accuracy or F1-score. Poor features are discarded or improved in subsequent iterations, resulting in a self-improving feature set. DAFG is particularly useful in environments where task definitions evolve or are poorly specified. However, its iterative and agent-based nature introduces complexity and computational overhead, which can be a barrier to widespread adoption.

3.9. Prototypical Reward Modeling (Proto-RM)

Proto-RM aims to improve reward modeling in Reinforcement Learning with Human Feedback (RLHF) by clustering similar human feedback samples and training on representative prototypes rather than individual data points. This approach reduces noise and increases sample efficiency, enabling better generalization from limited labeled feedback. Proto-RM is especially valuable in low-resource settings where annotated data is scarce. However, the effectiveness of the model heavily depends on the quality of clustering, and poor prototype selection can lead to misleading reward signals.

3.10. Data Augmentation

Data augmentation techniques expand the training dataset by creating synthetic examples, which improves model robustness and generalization. Methods like SMOTE (for balancing imbalanced datasets), Mixup (interpolating input-label pairs), and GANs (generating realistic synthetic samples) have been widely adopted across NLP, vision, and tabular domains. These techniques are particularly effective in low-data or imbalanced-class scenarios. Nonetheless, poorly tuned augmentation can introduce noise, unrealistic data, or bias, potentially degrading model performance.

Table 1.

Comparative analysis of work.

Table 1.

Comparative analysis of work.

| Method |

Dataset/Task |

Interpretability |

Scalability |

Strength |

Limitation |

| CoT |

GSM8K, SVAMP |

Medium |

High |

Enables stepwise logical reasoning |

May propagate early reasoning errors |

| ToT |

Game of 24 |

High |

Low |

Explores multiple reasoning paths |

Computationally intensive |

| RAG |

Natural Questions, TriviaQA |

High |

Medium |

Improves factual grounding |

Dependent on retrieval quality |

| RATT |

StrategyQA |

High |

Low |

Combines CoT, ToT, and retrieval for robust reasoning |

High architectural complexity |

| TSE |

Commonsense QA |

High |

Medium |

Expands reasoning space dynamically |

May generate redundant steps |

| TIFG |

Clinical QA, Tabular Text |

High |

Medium |

Produces domain-specific, explainable features |

Requires curated context |

| DAFG |

MLBench tasks |

High |

Low |

Iteratively refines features via feedback loops |

Needs multi-agent orchestration |

| TFWT |

UCI tabular datasets |

Medium |

High |

Learns contextual feature importance |

Limited transparency in attention weights |

|

SMOTE/Augment

|

Imbalanced tabular/image data |

Low |

High |

Increases diversity in underrepresented classes |

May introduce noise or artifacts |

| Proto-RM |

HH-RLHF |

Medium |

High |

Enhances data efficiency in RLHF |

Sensitive to prototype definition |

Through this detailed exploration, it becomes evident that each method contributes uniquely to enhancing the reasoning capabilities and data-processing effectiveness of large language models. While inference techniques like CoT, ToT, and RATT prioritize logical structure and factual grounding, feature-oriented methods such as TIFG, TFWT, and DAFG focus on improving data representations and model adaptability. Auxiliary strategies like Proto-RM and data augmentation serve as critical enablers, enhancing learning efficiency and generalization. Together, these innovations represent a shift from static model execution to dynamic, interpretable, and feedback-aware systems. This analysis lays the groundwork for identifying synergies and limitations across approaches, which we expand upon in the following sections through real-world applications and discussion of open challenges.

4. Key Insights and Open Research Challenges

Several patterns emerge from this review:

- 4.1.

Co-evolution of Reasoning and Retrieval: Structured prompting techniques increasingly incorporate retrieval to support factual accuracy. RAG and RATT are prime examples. However, they also increase latency and model complexity.

- 4.2.

Rise of Feedback Loops: Feature generation frameworks now support feedback from downstream task metrics. Adaptive FG agents iterate over proposals, using results to refine feature quality.

- 4.3.

Importance of Interpretability: CoT, ToT, and TIFG are popular because they make decisions understandable. This is essential in high-stakes domains like healthcare or finance.

- 4.4.

Cost and Scalability: Tree-based reasoning and dynamic feature generation are compute-intensive. Future work must address the trade-off between complexity and accuracy.

Open questions include:

- -

How to benchmark reasoning-guided feature generation?

- -

Can LLMs generate features for non-textual modalities (e.g., images, graphs)?

- -

What are the theoretical limits of inference-augmented data engineering?

- -

How can transparency and performance be jointly optimized in domains that require both accuracy and explainability?

5. Limitations and Future Directions

While recent progress in LLM-based inference and feature generation is promising, several limitations remain that warrant attention from the research community.

- 5.1

Lack of Unified Frameworks: Most reviewed methods address either reasoning or feature engineering in isolation. Although approaches like TIFG and RATT begin to merge these paradigms, there is no end-to-end pipeline that modularly integrates reasoning, feature construction, and feedback-driven refinement in a scalable architecture.

- 5.2

Benchmarking Challenges: Unlike traditional NLP tasks that rely on standard benchmarks such as GLUE or SQuAD, LLM-based feature generation lacks evaluation protocols for assessing feature novelty, interpretability, and downstream effectiveness. This hampers reproducibility and model comparison across studies.

- 5.3

Interpretability Trade-offs: While tree-based reasoning methods like ToT and TSE enhance transparency, they often incur high computational costs and longer inference times. On the other hand, transformer-based approaches like TFWT provide performance gains but may obscure the model’s decision logic—especially to non-expert users.

- 5.4

Generalization and Domain Transfer: Many proposed techniques are demonstrated on narrowly scoped or synthetic datasets, limiting confidence in their performance on real-world, noisy, or multimodal data. Broader validation and domain adaptation strategies are required to ensure robustness.

- 5.5

Underutilization of Human Feedback: Human-in-the-loop collaboration is largely restricted to reward modeling stages (e.g., RLHF). Broader incorporation of user input during reasoning or feature generation—such as approving, modifying, or vetoing model-generated elements—could make systems more interactive and trustworthy.

- 5.6

Ethical and Fairness Considerations: As LLMs influence high-stakes domains, issues of fairness, bias, and transparency become critical. There is an urgent need for research on ethical safeguards, bias mitigation, and explainable feature attribution in both reasoning and data generation processes.

6. Real-World Applications: Integrating LLM Methods to Overcome Systemic Limitations

Building on the previously discussed taxonomy and comparative analysis, this section illustrates how various LLM-based methods can be applied in real-world settings through three use case scenarios. To better illustrate the practical implications of integrating large language model (LLM) inference and feature generation, this section presents real-world use case scenarios that leverage the methods reviewed in this survey. These examples demonstrate how structured reasoning, retrieval augmentation, and adaptive feature design can work together to address complex tasks across various domains such as fraud detection, personalized education, and medical triage. By grounding abstract methods like TIFG, RATT, ToT, TFWT, and TSE into application contexts, we highlight their potential to enhance system performance, interpretability, and adaptability.

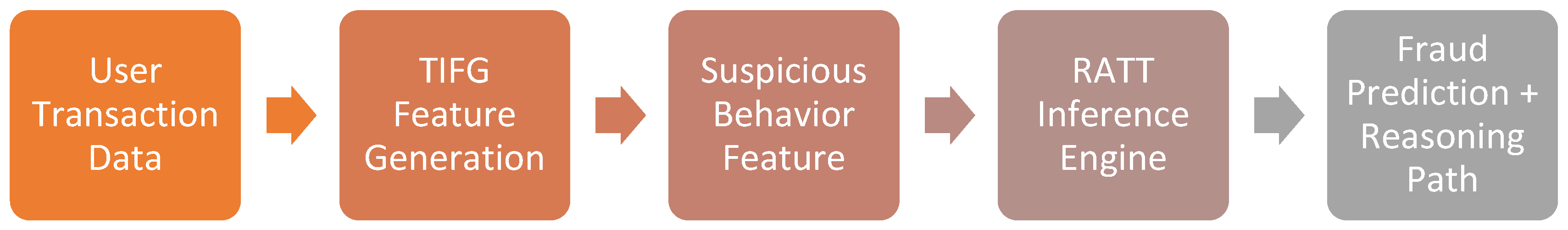

6.1. Use Case 1: Fraud Detection Using RATT and TIFG

Fraud detection systems must not only identify suspicious behavior accurately but also explain why a specific transaction or account is flagged—especially in domains like banking, insurance, or e-commerce where trust and regulation are key. Large language models offer a promising approach to enhance both precision and interpretability in these systems.

In this scenario, we propose a system that integrates Text-Informed Feature Generation (TIFG) and Retrieval-Augmented Thought Trees (RATT) to form a reasoning-aware fraud detection pipeline.

The pipeline begins with structured and semi-structured input such as transaction logs, device fingerprints, login history, and user demographics. TIFG is used to prompt an LLM to dynamically generate new, domain-informed features from this data. For example, it may infer "inconsistency score" based on address changes or compute a "login context risk factor" using metadata and real-time location anomalies. These features are generated using prompt templates and retrieval-augmented signals from known fraud cases or regulatory documents.

These enriched features are then passed into the RATT inference module, which constructs multiple reasoning paths to assess the probability of fraud. Each path may evaluate different hypotheses—for example, one may test for account takeover risk, while another checks behavioral anomalies. By using retrieved documents (e.g., prior fraud examples or compliance reports), RATT ensures each reasoning path is both logically sound and factually grounded.

The final output is a binary fraud prediction (fraud or no fraud) alongside an interpretable reasoning chain. This structured explanation can be reviewed by human analysts or used to trigger compliance workflows. Importantly, the system can adapt as new fraud types emerge—by adjusting the feature generation prompts or incorporating new retrieved materials.

Benefits:

High explainability due to reasoning trees.

Strong contextual relevance via LLM-generated features.

Fewer false positives due to targeted inference paths.

Easily auditable, satisfying legal requirements for model transparency.

Figure 2.

Use Case 1: Fraud Detection with RATT and TIFG.

Figure 2.

Use Case 1: Fraud Detection with RATT and TIFG.

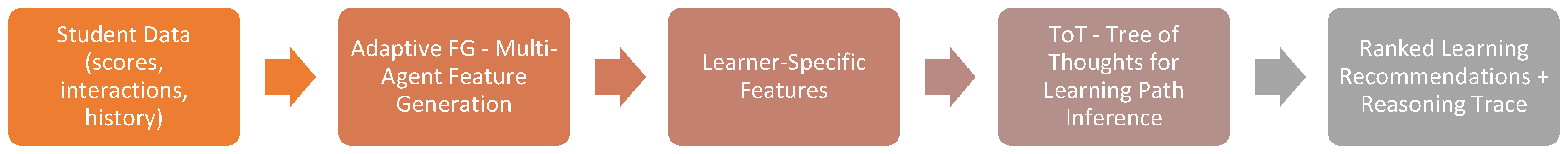

6.2. Use Case 2: Personalized Learning Pathways Using ToT and Adaptive FG

Modern education platforms increasingly seek to provide personalized learning experiences, tailored to a student's pace, strengths, and weaknesses. However, static recommendation systems often lack the reasoning depth and adaptability required to truly individualize content. Large language models can address this gap by combining multi-agent feature generation with structured reasoning.

In this use case, we propose a hybrid system that integrates Adaptive Feature Generation (Adaptive FG) and Tree of Thoughts (ToT) to model student behavior and recommend next steps in their learning journey.

The input includes student interaction data (quiz scores, question attempts, time on task), demographic metadata, and historical content engagement. The Adaptive FG module launches LLM agents that generate candidate features such as "concept retention decay," "preferred learning modality," or "struggle topic cluster." These features are evaluated using the student's performance on recent tasks and updated iteratively via a feedback loop.

The refined feature set is passed into the ToT-based inference system, where the LLM constructs a decision tree to explore multiple learning pathways. For instance, one branch might suggest revision of prerequisite topics, while another proposes switching from text to video material. Each node in the tree reflects a pedagogical action and is evaluated based on estimated learning gain, engagement likelihood, and student fit.

The system outputs a ranked list of actionable recommendations (e.g., "review concept X via visual explanation" or "skip ahead to advanced problems in topic Y") along with a reasoning path for each suggestion. Instructors or students can trace the logic and adjust preferences, supporting human-in-the-loop customization.

Benefits:

Rich, interpretable learning analytics for educators.

Personalized content sequencing based on actual behavior patterns.

Adaptive, feedback-driven refinement of recommendations.

Supports both autonomous learners and guided instruction.

Figure 3.

Use Case 2: Medical Triage Using TFWT and TSE.

Figure 3.

Use Case 2: Medical Triage Using TFWT and TSE.

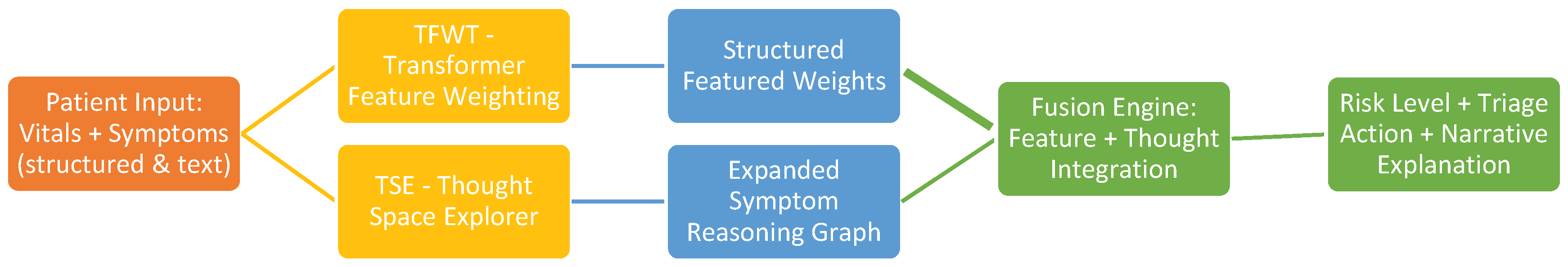

6.3. Use Case 3: Medical Triage and Symptom Analysis Using TSE and TFWT

Modern healthcare systems often face the dual challenge of managing patient overload while ensuring timely, accurate triage. Patients input a range of symptoms—often vague or unstructured—and clinicians must quickly prioritize who needs urgent care, who can wait, and who can be self-treated. In such situations, a system that combines deep reasoning with context-sensitive feature evaluation can be invaluable.

We propose a system that integrates Thought Space Explorer (TSE) for deep reasoning and Transformer-based Feature Weighting for Tabular Data (TFWT) for personalized, interpretable feature importance to assist in AI-driven medical triage.

The process starts with patient-reported data, which may include structured fields (age, sex, vital signs, symptom duration) and free-form symptom descriptions. First, TFWT processes structured inputs and applies attention-based mechanisms to assign relevance scores to each feature—prioritizing, for example, heart rate in elderly patients or respiratory symptoms during a flu outbreak. Unlike static feature weights, TFWT’s attention allows personalized weighting, adapting the triage evaluation per patient.

Simultaneously, the free-text symptom input is parsed and reasoned through using TSE, which builds a graph of possible medical conditions or causes. TSE introduces and explores “thought nodes”, such as “shortness of breath → potential asthma or cardiac issue → check for history of hypertension.” It expands this graph by hypothesizing intermediate causes and branching reasoning paths that allow exploratory diagnosis.

The outputs from both components are fused into a triage decision: a risk score (e.g., high, medium, low) and a reasoning trace that includes both structured evaluation (via TFWT) and narrative inference (via TSE). For instance, the system might output:

“High-risk triage: Elevated heart rate and breathlessness in elderly patient with hypertension. Thought path: possible cardiac issue > recommend immediate ECG and physical exam.”

Benefits:

Combines structured data precision with unstructured reasoning.

Personalized triage recommendations tailored to risk profiles.

Highly interpretable: shows what mattered and why.

Scalable: could be deployed in clinics, telemedicine apps, or pre-screening portals.

This setup supports not only frontline clinicians but also under-resourced settings where decision support is critical. It demonstrates how LLMs can be used not to replace clinicians, but to augment decision-making in complex, high-stakes environments.

Figure 4.

Use Case 3 Medical Triage Using TFWT and TSE.

Figure 4.

Use Case 3 Medical Triage Using TFWT and TSE.

7. Conclusions

This survey has provided a comprehensive analysis of the evolving landscape of Large Language Models (LLMs), focusing on two interconnected domains: inference and feature generation. We reviewed ten influential methods, which were categorized into three major themes—structured reasoning techniques (e.g., Chain-of-Thought, Tree-of-Thoughts, RAG, RATT, TSE), feature generation and weighting frameworks (e.g., TIFG, Adaptive FG, TFWT), and auxiliary strategies such as data augmentation and reward modeling (e.g., Proto-RM).

Through a detailed comparative framework, we identified key strengths of each method in terms of scalability, interpretability, and adaptability. We observed a notable shift toward retrieval-augmented reasoning, attention-based feature selection, and feedback-driven refinement—signaling a maturation in LLM-based system design. However, several persistent limitations remain, including limited integration across techniques, the absence of standardized benchmarks for evaluating generated features, and challenges in ensuring interpretability and generalizability.

To illustrate real-world relevance, we presented three detailed application scenarios across fraud detection, personalized learning, and medical triage. These case studies demonstrated how structured reasoning and adaptive feature learning can work together to tackle high-stakes decision-making tasks that demand explainability, adaptability, and trustworthiness.

In summary, LLMs are evolving from passive predictors into active agents—capable of constructing, reasoning, and adapting features for complex environments. We envision a future where unified frameworks seamlessly combine inference, feature engineering, and feedback mechanisms to build transparent, modular, and intelligent systems. Advancing toward this vision will not only expand the scope of LLM applications but also shape the next generation of interpretable and reliable AI solutions.

References

- T. B. Brown, B. Mann, N. Ryder et al., “Language Models are Few-Shot Learners,” in Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, vol. 33, 2020, pp. 1877–1901.

- Chowdhery, S. Narang, J. Devlin et al., “PaLM: Scaling Language Modeling with Pathways,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2204.02311, 2022.

- H. Touvron, T. Lavril, G. Izacard et al., “LLaMA: Open and Efficient Foundation Language Models,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2302.13971, 2023.

- J. Wei, X. Wang, D. Schuurmans et al., “Chain-of-Thought Prompting Elicits Reasoning in Large Language Models,” Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, vol. 35, 2022.

- Yao, D. Yu, J. Zhao et al., “Tree of Thoughts: Deliberate Problem Solving with Large Language Models,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2305.10601, 2023.

- P. Lewis, E. Perez, A. Piktus et al., “Retrieval-Augmented Generation for Knowledge-Intensive NLP Tasks,” Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, vol. 33, 2020.

- M. Lewis, Y. Liu, N. Goyal et al., “BART: Denoising Sequence-to-Sequence Pre-training for Natural Language Generation,” in Proceedings of the 58th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, 2020, pp. 7871–7880. [CrossRef]

- J. Zhang, X. Wang, W. Ren et al., “RATT: A Thought Structure for Coherent and Correct LLM Reasoning,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2406.02746, 2024. [CrossRef]

- J. Zhang, F. Mo, X. Wang, and K. Liu, “Thought Space Explorer: Navigating and Expanding Thought Space for Large Language Model Reasoning,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2410.24155, 2024.

- J. Zhang, F. Mo, and K. Liu, “Text-Informed Feature Generation with LLMs,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2406.11177, 2024.

- J. Zhang, F. Mo, and K. Liu, “Dynamic and Adaptive Feature Generation with LLMs,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2406.03505, 2024.

- J. Zhang, X. Wang, and K. Liu, “Transformer-Based Feature Weighting for Tabular Data Using LLMs,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2405.08403, 2024.

- Z. Wang, Q. Yang, and Y. Li, “A Comprehensive Survey on Data Augmentation,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2405.09591, 2024.

- N. V. Chawla, K. W. Bowyer, L. O. Hall, and W. P. Kegelmeyer, “SMOTE: Synthetic Minority Over-sampling Technique,” Journal of Artificial Intelligence Research, vol. 16, pp. 321–357, 2002. [CrossRef]

- H. Zhang, M. Cisse, Y. N. Dauphin, and D. Lopez-Paz, “mixup: Beyond Empirical Risk Minimization,” in International Conference on Learning Representations, 2018. [Online]. Available: https://openreview.net/forum?id=r1Ddp1-Rb.

- J. Zhang, X. Wang, and K. Liu, “Proto-RM: A Prototypical Reward Model for Data-Efficient RLHF,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2406.06606, 2024.

- L. Ouyang, J. Wu, X. Jiang et al., “Training Language Models to Follow Instructions with Human Feedback,” Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, vol. 35, 2022.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).