Introduction

Crop breeding has entered the genomics era, yet its progress has long been constrained by reliance on a single reference genome to represent a species’ genomic sequences. While this single-reference approach has been foundational, it overlooks the vast genetic diversity within crops, as evidenced by the increasing number of genome assemblies [

1]. These advances reveal that single reference genome missed significant number of SVs, PAVs, and novel genes that distinguish cultivated varieties and wild relatives [

2]. The pangenome, representing the combined genetic diversity of multiple accessions, has emerged to encompass core genes found in every individual and dispensable gene missing from one or more accessions [

3]. By capturing significantly more diverse genes and SVs present in both cultivated and wild rice, the pangenome offers a more comprehensive blueprint of rice genetics than any single genome alone [

4].

Despite its potential to uncover hidden genetic variation, a substantial gap remains between generating pangenomic datasets and applying them in breeding programs. This gap arises from the lack of breeder friendly SV/PAV genotyping platforms, integrated pipelines that connect pangenomic and phenotypic data, and sufficient computational resources and expertise to analyze graph-based pangenome. This disconnect raises critical questions for plant geneticists and breeders: How can we harness this richer genomic resource to accelerate molecular breeding? What technical and practical barriers hinder the integration of pangenomics data into routine breeding workflows?

As a staple crop for over half the global population and a model organism in cereal genomics, rice offers an ideal case study to address above challenges. This review uses rice to explore the promise of the pangenome for crop improvement, highlight recent breakthroughs enabled by pangenomics approaches, and examine the technical and practical challenges that must be addressed before pangenome-assisted breeding can become routine. Although our focus is on rice pangenomics as a model system, the challenges and solutions discussed are broadly applicable to pangenome-enabled breeding in other crops.

The Promise of the Pangenome in Rice Breeding

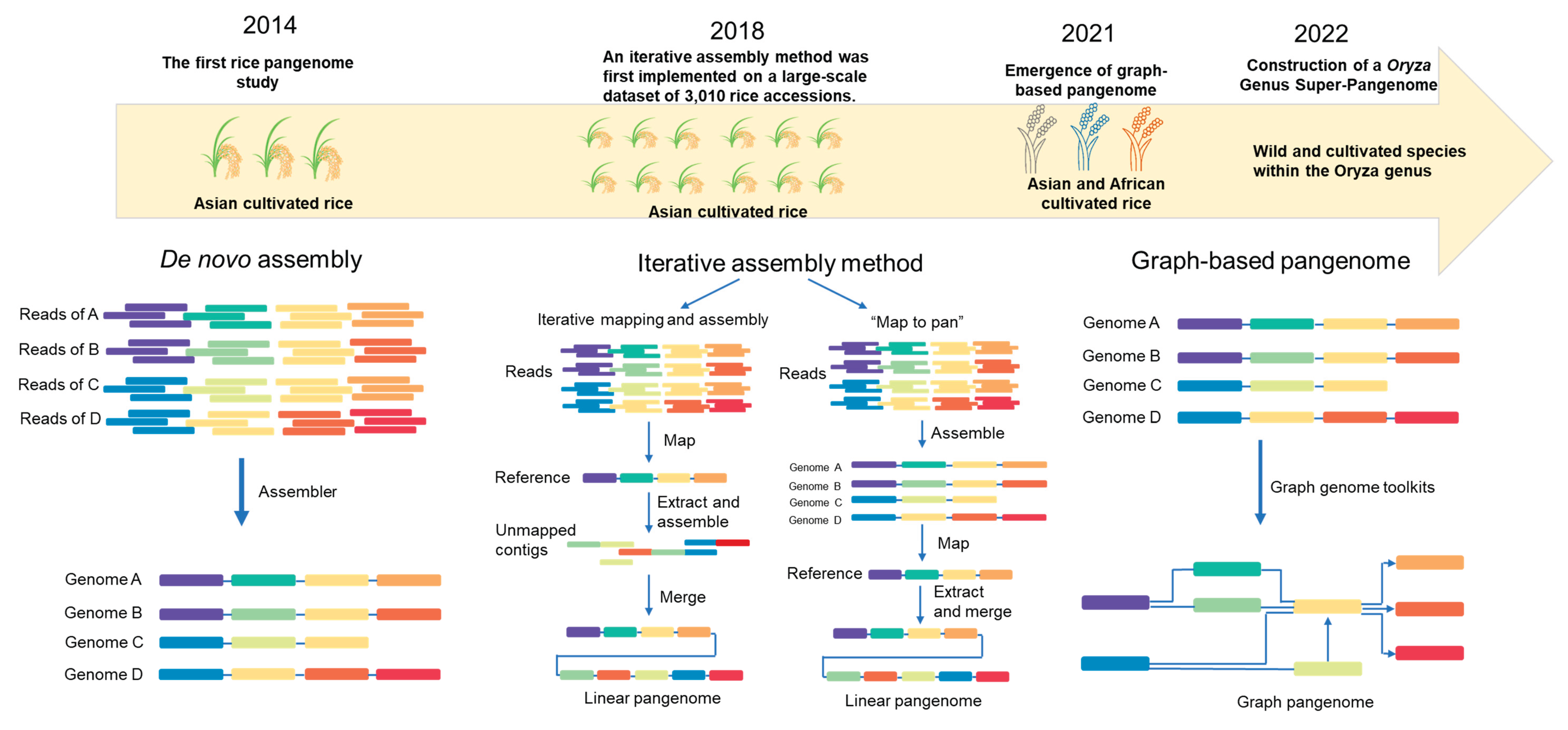

Rice pangenome research has progressed markedly in recent years, with more than 10 pangenomics studies published to date (

Table 1), reflecting both technological innovations and an expanding research scope (

Figure 1). Early pangenomics studies focused primarily on Asian cultivated rice (

Oryza sativa) and were limited to only a few representative varieties [

5]. Advances in sequencing technologies and computational methods have since enabled the inclusion of wild rice species (

Oryza rufipogon) [

6] and African rice (

Oryza glaberrima) [

7].

Notably, a linear rice pangenome was constructed using 3010 Asian cultivated rice accessions to delineate nine distinct subpopulations, including several novel geographically defined groups, and provides unprecedented resolution of population structure and genetic diversity [

8]. This comprehensive resource establishes a robust framework for exploring allelic variation and informing future rice breeding strategies. Another landmark study constructed a graph-based pangenome from 145 wild and cultivated rice genomes. This effort revealed 3.87Gb of novel sequences absent from the reference genome and identified 69,531 pan-genes, including 19.74% wild-specific genes linked to disease resistance and environmental adaptation [

9]. This work also resolved longstanding debates by affirming a single origin of domestication for Asian rice and tracing the emergence of

indica and

basmati subpopulations through gene flow [

9]. These developments underscore the evolution of pangenome studies from linear reference genomes to dynamic graph-based frameworks, capturing SVs and PAVs across thousands of accessions. Complementing these approaches, gene-centric analyses like the Rice Gene Index (RGI) [

10] integrate gene annotations from multiple individual genomes to map the pan-coding potential (the pangene set) of the species, offering a unified Ortholog Gene Index (OGI) for functional studies. Moreover, incorporating diverse

Oryza species into pangenome analyses also provides a more comprehensive view of the genus’s genetic diversity, facilitating the discovery of novel genes and SVs essential for breeding [

11]. For instance, a recent pangenome study spanning the

Oryza genus identified unique NBS-LRR gene clusters in BB- and GG-genome wild rice species, representing untapped resistance loci absent from modern cultivars [

12]. Collectively, these rice pangenomes provide an unprecedented catalog of genetic variation, which holds enormous promise for breeding applications.

Integrating pangenomic data into breeding strategies represents a transformative shift in rice improvement. Traditional breeding and association studies that rely on a single reference genome often overlook critical genes, especially those absent from the reference, as well as SVs underlying essential traits [

13]. In contrast, a pangenomic approach encompasses both core genes and dispensable genes, thereby harnessing a wider spectrum of genetic variation. For example, a rice pangenome analysis of 3,010 Asian accessions uncovered ~268 Mb of sequence absent from the Nipponbare reference, revealing 12,465 novel genes and 19,721 dispensable genes [

8]. Later studies employing long-read sequencing of 111 genomes further expanded the known pangenome, identifying a total of 879 Mb of new sequences and ~19,000 new genes when wild rice relatives were included [

14]. Rice pangenomes thus reveal a vast reservoir of previously hidden alleles associated with disease resistance, stress tolerance, yield, and grain quality, offering breeders valuable new targets for selection [

15,

16,

17]. By moving beyond the constraints of a single reference genome, researchers can now capture “missing heritability” by exploring SVs and PAVs across diverse germplasm [

18]. Beyond merely cataloging genes, pangenome references can be integrated with modern molecular breeding strategies such as genome-wide association studies (GWAS) [

19] and genomic selection [

20]. This allows PAVs and SVs to serve as genetic markers alongside SNPs, providing a more comprehensive genotype dataset for linking genetic variation to phenotypes. As a result, SV-controlled traits can be pinpointed more effectively, and candidate genes located in regions absent from a single reference can be uncovered within the pangenome. Overall, the rice pangenome offers a more holistic view of genetic diversity, enabling more precise and efficient breeding, spanning approaches from marker-assisted selection and SV-augmented genomic selection to the direct editing of novel genes into elite varieties.

Breakthroughs in Trait Discovery Enabled by Rice Pangenomics

The potential impact of pangenomics on crop improvement is immense, as demonstrated by numerous recent case studies and applications in rice breeding [

17,

21,

22]. Integrated pangenome analyses have unlocked important agronomic traits that previously eluded detection by conventional single-reference approaches [

17]. Several notable examples exemplify how pangenomics has transformed rice research and breeding. A major breakthrough involves the discovery of novel loci for yield and plant architecture. For example, using a 12-genome rice pangenome reference, Wang et al. [

23] applied PAV-based GWAS to 413 diverse rice lines, successfully identifying causal structural variants affecting grain weight and plant height that traditional SNP-based GWAS (using a single reference genome) had failed to detect. Notably, a new quantitative trait locus (QTL) for plant height on chromosome 8 (

qPH8-1) was discovered exclusively through the pangenomics analysis, highlighting its unique power to reveal hidden genetic factors influencing key yield components [

16].

Similarly, pangenomic approaches have significantly enhanced the discovery of disease resistance genes in rice [

12]. Resistance loci often occur in clusters and are exhibit presence/absence polymorphism, making them difficult to detect with single-reference methods. By harnessing pangenome-based GWAS, a recent study discovered 74 QTLs for blast resistance, including the novel

qPBR1 (conferring both panicle and leaf blast resistance) and

qPBR12 (co-localized with the known broad-spectrum resistance gene

ptr) [

24]. Within

qPBR1, six candidate genes were pinpointed, one of which (

LOC_Os1g14580) showed a strong association with enhanced blast resistance. This pangenome-driven approach not only revealed new resistance loci but also reaffirmed established R genes (such as

Pi9,

Pi5,

Pid1, and

Pita), demonstrating the power of pangenome-based genotyping to capture both known and novel disease resistance genes.

Moreover, pangenomics approaches have shed light on the genetic basis of heat stress tolerance in rice. A recent study constructed a mini-pangenome from 60 rice cultivars (45 heat-tolerant and 15 susceptible) to identify genes associated with high-temperature tolerance [

25]. This analysis revealed 1,141 genes exclusive to heat-tolerant varieties and absent from the reference genome; many of these genes were differentially expressed under heat stress. By intersecting these findings with known heat-tolerance QTLs, researchers pinpointed two strong candidate genes from non-reference regions, suggesting promising targets for developing heat-resilient rice cultivars. Furthermore, the development of the Rice Pangenome Genotyping Array (RPGA), which incorporates approximately 80,000 markers (including SNPs and PAVs) from the 3K rice pangenome, has underscored the practical value of pangenomics tools [

26]. GWAS using the RPGA, identified 42 loci associated with grain size and weight, including eight novel loci that were undetected by traditional single-reference approaches. For example, a dispensable gene on chromosome 7, encoding a WD40-repeat protein at the

qLWR7 locus, was identified as a regulator of the grain length/width ratio. Validation with mapping populations confirmed that pangenome-based markers can reliably uncover new yield-related genes, offering tangible targets for marker-assisted selection or gene editing.

Collectively, these studies illustrate that incorporating pangenome data into rice breeding programs enables the capture of “missing” genetic variations related to yield, plant architecture, stress tolerance, and disease resistance. Tools such as pangenome arrays and PAV-GWAS broaden the search for beneficial alleles and provide a direct pathway from genomic discovery to breeding application.

Key Barriers to Translating Pangenomics Insights into Practical Breeding

However, transitioning these proof-of-concept successes into routine breeding strategies will require further efforts to address remaining technical and logistical challenges. Several challenges continue to impede its integration into routine molecular breeding (

Table 2). Below, we highlight the major barriers.

Data Volume and Complexity Limit Functional Variant Discovery

A primary obstacle is the enormous volume of data generated: a comprehensive rice pangenome can encompass tens of thousands of variable genes and millions of SVs, making it difficult to extract actionable insights [

27]. Most current studies remain focused on bi-allelic variants, largely due to limitations of short-read sequencing technologies and the lack of robust analytical frameworks capable of handling complex multi-allelic variation. Complex variants, such as tandem repeats, are frequently underrepresented because their accurate detection and interpretation require high-quality genome assemblies, graph-based reference structures, and integration with multi-omics datasets [

28].

Identifying which alleles are functionally relevant requires more than just DNA sequencing data but also integration of transcriptomic, epigenomic, and phenotypic information. For example, RNA expression profiles reveal which genes are active; epigenetic marks show how chromatin status influences allele usage, and observable trait measurements (e.g., yield, stress response) link specific variants to real-world outcomes. High-throughput analytical pipelines that systematically combine these diverse data types with pangenomes, researchers can narrow hundreds of thousands of polymorphisms down to the subset that directly drives meaningful biological functions or agronomic traits. For instance, integrating transcriptomic profiles from key developmental stages with the rice pangenome data has been essential for uncovering the regulatory roles of multiallelic variants [

29]. In one notable study, genome-wide DNA methylation (methylome) and transcriptome data were combined in rice hybrids and their parents to identify differentially methylated regions associated with allele-specific expression and phenotypic traits such as tiller number and biomass, demonstrating the epimutations can drive heritable expression changes relevant to agronomic performance [

30]. Such integrative approaches enable the identification of expression quantitative trait loci (eQTLs) that remain undetectable using bi-allelic markers alone, offering deeper insights into the genetic regulation of complex traits and supporting more precise breeding decisions [

31].

Emerging AI Approaches in Pangenome Interpretation: Gaps for Breeding

While artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) offer transformative potential for interpreting complex pangenomics data, but integrating these approaches into practical breeding pipelines remains a significant gap [

43,

44]. Recent advances demonstrate that AI can enhance the detection and genotyping of SVs and PAVs within pangenomes that are normally challenging for traditional bioinformatics methods, especially as data volume and complexity increase [

45]. For example, convolutional neural networks (CNNs) and other deep learning models have been incorporated into SV detection pipelines, improving sensitivity and accuracy across large population datasets and enabling the construction of high-resolution pan-SV maps [

46]. These advances provide breeders with more precise molecular markers and facilitate the identification of cultivar-specific targets for genome editing.

Despite these technical breakthroughs, the application of AI in breeding with pangenome-assisted faces several key obstacles. One major issue is usability and accessibility for breeders: most AI-driven tools for pangenome analysis are designed for geneticists and bioinformaticians, not breeders. Breeding programs struggle to adopt pangenome based methods because intuitive, breeder-friendly interfaces and visualization platforms are lacking to translate complex graph structures into actionable trait and variant information [

47]. At the same time, breeding datasets such as field trial records, remote sensing images and pedigree data exist in separate silos and cannot be integrated smoothly with genomic variant data [

48]. Creating unified portals and decision support modules that bring these diverse streams together will be essential to applying pangenomic insights in everyday breeding decisions. There remains a disconnect between the genetic insights generated by AI-powered pangenome analysis and the phenotypic and breeding data needed for selection decisions. Effective breeding requires the integration of genotypic, phenotypic, and environmental data, yet current ML models often lack access to structured, high-quality breeding datasets with standardized metadata [

49]. Data scarcity and imbalance further impede the development of robust ML models. Many crops-especially orphan or under-resourced species-suffer from limited genomic and phenotypic data, impeding the development of accurate predictive models for breeding [

3]. In addition, model interpretability and trust remain to be concerns. Breeders need transparent and interpretable models to make confident selection decisions. However, many state-of-the-art AI models, particularly deep learning architectures, function as “black boxes,” making it difficult to understand how predictions are made or to validate results in a breeding context [

50].

Furthermore, resource and infrastructure limitations present another barrier. The computational demands of AI-driven pangenome analysis can be prohibitive for many breeding programs, particularly in low- and middle-income regions [

51]. These issues are not merely extensions of general pangenome adoption barriers; they are specific challenges arising from the application of AI/ML as an enabling technology in breeding. For example, while AI/ML could theoretically streamline variant discovery and trait prediction, the current lack of standardized, high-quality datasets and explainable models limits their practical utility in breeding programs [

52]. Moreover, the resource requirements for deploying advanced AI models often exceed the capacity of many breeding operations, particularly in resource-limited settings. To bridge this gap, future efforts should prioritize the development of AI tools that are tailored for breeding applications, including user-friendly interfaces, standardized data integration frameworks, and explainable models [

53]. Collaborative initiatives to share and standardize breeding datasets, as well as investments in local capacity and infrastructure, will be essential for democratizing access to these technologies and ensuring their impact on crop improvement [

54].

Translational and Organizational Challenges in Applying Pangenomics Discoveries

Even after novel trait-associated genes are identified, significant translational and organizational challenges remain in bringing these discoveries to fields. Introgression of valuable alleles from wild rice or untapped landraces into elite cultivars often requires multiple generations and can be complicated by issues such as linkage drag or reduced fertility [

55]. While conventional methods like marker-assisted backcrossing are widely used to move traits from wild into cultivated backgrounds, genome editing techniques (particularly CRISPR/Cas9) offer a promising alternative [

56].

Rice pangenome studies have uncovered beneficial genes, particularly resistance loci lost during domestication but retained in wild rice [

57]. Leveraging these findings through a “super-pangenome guided” genome editing strategy can rapidly reintroduce desirable traits such as drought tolerance or disease resistance into modern varieties, potentially circumventing the lengthy process of backcrossing [

57]. However, the implementation of both traditional and genome editing approaches faces hurdles, including regulatory constraints on genetically modified crops and the need for breeder acceptance of new technologies. These issues are common across crop improvement programs.

Breeders typically rely on established selection criteria and operational pipelines, so introducing complex structural variation information or novel PAV markers identified through pangenomics demands a significant shift in breeding practice. This transition requires extensive communication and knowledge exchange between genomic researchers and breeding practitioners [

58]. Furthermore, the technical complexities of interpreting and applying large-scale pangenomic datasets often exceed breeders’ traditional expertise. This highlights the critical importance of collaborative training programs, user-friendly bioinformatics tools, and decision-support platforms tailored to practical breeding scenarios [

59].

Conclusions and Outlook

The translation of the rice pangenome into routine molecular breeding applications is progressing steadily, albeit with several challenges still to be overcome. Recent proofs-of-concept studies have demonstrated the power of pangenomics approaches to identify trait-associated genes that conventional methods failed to detect [

60]. The development of innovative tools, such as pangenome-based SNP arrays and the expansion of comprehensive

Oryza genus-wide pangenomes further reinforce the transformative potential of this approach for both functional genomics and practical breeding. Collectively, these advancements indicate that the rice pangenome is emerging as a valuable model for crop improvement.

Despite this progress, significant obstacles remain before pangenome-informed breeding becomes widespread. Many breeding programs are only beginning to incorporate massive genomics datasets into their decision-making processes. Continued refinement of analytical methods, reductions in costs, and capacity building through training and infrastructure investment are essential to transition these advances from research settings into routine breeding practice [

61]. A critical emerging challenge lies in the integration of AI and ML approaches into pangenome interpretation and breeding pipelines. AI/ML techniques have shown remarkable potential to enhance the detection and genotyping of complex SVs and PAVs, tasks that are difficult for traditional methods, but several practical gaps currently limit their adoption in plant breeding [

62]. These include the lack of breeder-friendly interfaces and decision-support tools, insufficient integration of genotypic, phenotypic, and environmental data, scarcity of large, well-annotated datasets for model training, issues of model interpretability, and high computational demands that many breeding programs cannot meet. Addressing these AI/ML-specific challenges through the development of accessible, explainable, and integrated tools, alongside collaborative data-sharing initiatives and infrastructure investment, will be essential to fully harness AI/ML’s transformative potential in crop breeding.

Looking ahead, by the late 2020s rice breeders may routinely use pangenome panels to select parental lines with complementary novel gene content. They could leverage pangenome-based GWAS to identify critical genomic regions for introgression from exotic donors, and consult expansive pangenome databases to guide precise gene editing strategies. Ultimately, the rice pangenome has evolved from an academic concept into a practical asset that promises to enhance molecular breeding [

22]. This transformation offers valuable lessons and best practices for many other crops. While the integration of pangenomic data into breeding pipelines is already underway, a few more years of collaborative research, infrastructure investment, and breeder engagement are needed to fully harness this emerging resource. The breakthroughs achieved to date offer a tantalizing glimpse of a future where higher-yielding, stress-resilient, and disease-resistant rice varieties are developed by exploiting the full breadth of genetic diversity. In summary, although the journey is ongoing, the fusion of pangenomic data, advanced genotyping platforms, and AI/ML-driven analytical tools with modern breeding strategies is well on its way—each technical advance bringing global agriculture closer to realizing this transformative promise and providing a framework for other crops to follow.

Table 1.

Summary of research progress in rice pangenomics studies.

Table 1.

Summary of research progress in rice pangenomics studies.

| Pangenome composition |

Pangenome construction method |

Pangenome representations |

Number of accessions |

Sequencing platform |

Reference |

| Asian cultivated rice and African cultivated rice |

Iterative mapping and assembly |

64.10 Mb PAVs and 43,232 pan-genes |

12 |

PacBio |

[23] |

| Asian cultivated rice |

Iterative mapping and assembly |

268 Mb PAVs and 53,758 pan-genes |

3,010 |

Illumina |

[8] |

| Asian cultivated rice and wild progenitor of Asian cultivated rice |

De novo assembly and gene annotations comparison |

10,872 gene PAVs and 42,580 pan-genes |

66 |

Illumina |

[6] |

| Asian cultivated rice and African cultivated rice |

Graph pangenome |

~24,469 PAVs and 66,636 pan-genes |

33 |

PacBio |

[7] |

| Asian and African wild and cultivated rice |

Graph pangenome |

Pan-genome of 1.52 Gb and 51 359 pan-genes |

251 |

Nanopore |

[57] |

| Asian and African wild and cultivated rice |

De novo assembly and gene annotations comparison |

604 Mb PAVS and 60,293 pan-genes |

111 |

PacBio |

[14] |

| Asian and African wild and cultivated rice, weedy rice |

De novo assembly and gene annotations comparison |

175,528 pan-gene families |

74 |

PacBio |

[63] |

| Asian cultivated rice |

De novo assembly and gene annotations comparison |

297 to 786 genome-specific loci |

3 |

Illumina |

[5] |

| Asian cultivated rice and wild progenitor of Asian cultivated rice |

De novo assembly and gene annotations comparison |

3.87 Gb of non-reference sequences and 69,531 pan-genes |

129 |

PacBio and Nanopore |

[9] |

| African cultivated rice |

De novo assembly and gene annotations comparison |

The gene number ranging from 49,662 to 51,262 |

3 |

Illumina |

[64] |

| Asian cultivated rice |

Iterative mapping and assembly |

38,998 pan-genes and 71.74Mb non--reference sequences |

60 |

Illumina |

[25] |

| Wild and cultivated Oryza species |

De novo assembly and gene annotations comparison |

101723 pan-gene families |

13 |

PacBio |

[12] |

| Asian cultivated rice |

De novo assembly and gene annotations comparison |

119783 pan-gene families |

16 |

PacBio |

[10] |

Table 2.

Current challenges and potential solutions in rice pangenomics studies and their breeding applications.

Table 2.

Current challenges and potential solutions in rice pangenomics studies and their breeding applications.

| Category |

Challenge |

Potential Solution |

| Data volume & variant complexity |

Pangenomes encompass tens of thousands of variable genes and millions of SVs, while multi-allelic variants (e.g., tandem repeats) remain underrepresented, complicating downstream analysis. |

Integrate transcriptomic, epigenomic, and phenotypic data through high-throughput pipelines, and employ gene-centric summarization workflows to extract core and dispensable gene sets for targeted allele discovery. |

| Computational & bioinformatic complexity |

Linear pangenome representations lack positional context, and graph-based tools (vg, GraphTyper2) demand substantial compute and memory, limiting scalability for large, repeat-rich plant genomes. |

Develop scalable software tools such as VRPG that combine linear reference coordinate projection, annotation integration, and advanced data structures for graph-based pangenome analysis. |

| Tool adaptation & resource constraints |

Many pangenome tools were developed for human datasets, and breeding programs often lack high-performance computing and specialized bioinformatics expertise. |

Establish plant-specific benchmarking frameworks and optimize human-derived tools for crop genomes, following best practices from recent methodological reviews. |

| Genotyping platform limitations |

Conventional SNP arrays miss non-reference and SVs, and novel pan-genome arrays require integration with existing breeding decision-support systems. |

Integrate RPGA outputs with genome navigation tools like RiceNavi to streamline QTL pyramiding and breeding-route optimization within familiar breeder interfaces. |

| AI & Machine Learning Gaps |

AI/ML shows promise for variant detection and trait prediction but faces usability, data, and trust issues. |

Develop accessible, explainable AI/ML tools tailored for breeding; standardize and share high-quality breeding datasets; invest in collaborative training and infrastructure; design user-friendly decision-support platforms; prioritize model transparency and integration with existing breeding workflows. |

| Translational & organizational hurdles |

Introgression of novel alleles via traditional backcrossing is time-consuming and prone to linkage drag, while CRISPR/Cas9 editing faces regulatory and breeder-acceptance barriers. |

Encourage partnerships among breeders, bioinformaticians, and policymakers to align pangenome data with regulations and breeding workflows through training and clear communication. |

Figure 1.

Timeline of major milestones in rice pangenomics research. The first rice pangenome was constructed in 2013 [

5]. Iterative assembly methods were subsequently applied to a large population of 3,010 Asian cultivated rice accessions [

8]. In 2021, the first graph-based rice pangenome was developed [

7], and by 2022, pangenomics studies had expanded to the genus

Oryza level [

57].

Figure 1.

Timeline of major milestones in rice pangenomics research. The first rice pangenome was constructed in 2013 [

5]. Iterative assembly methods were subsequently applied to a large population of 3,010 Asian cultivated rice accessions [

8]. In 2021, the first graph-based rice pangenome was developed [

7], and by 2022, pangenomics studies had expanded to the genus

Oryza level [

57].

Authors Contribution

H.H. and C.K.K.C. wrote the manuscript. S.N., C.K.K.C., F.L., O.N.G, S.M.A, R.L., J.Z., and H.H. contributed to editing the manuscript.

Data availability Statement

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32400512). The GuangDong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation (2024A1515011981). The “YouGu” Plan and “Outstanding youth Researcher” of Rice Research Institute of Guangdong Academy of Agricultural Sciences (2023YG04&2024YG01), the Introduction of Young Key Talents of Guangdong Academy of Agricultural Sciences (R2023YJ-QC001). We thank Dr. Runxuan Zhao of the James Hutton Institute for providing valuable feedback during manuscript editing.

Conflicts of Interests

There is no competing interest within the authors.

References

- Schreiber, M. , Jayakodi, M., Stein, N. & Mascher, M. Plant pangenomes for crop improvement, biodiversity and evolution. Nature Reviews Genetics 2024, 25, 563–577. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Y.; et al. Pan-genome inversion index reveals evolutionary insights into the subpopulation structure of Asian rice. Nature Communications 2023, 14, 1567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H. , Zhao, J., Thomas, W.J.W., Batley, J. & Edwards, D. The role of pangenomics in orphan crop improvement. Nat Commun 2025, 16, 118. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, E. , Huang, X., Tian, Z., Wing, R.A. & Han, B. The genomics of Oryza species provides insights into rice domestication and heterosis. Annual review of plant biology 2019, 70, 639–665. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Schatz, M.C.; et al. Whole genome de novo assemblies of three divergent strains of rice, Oryza sativa, document novel gene space of aus and indica. Genome biology 2014, 15, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Q.; et al. Pan-genome analysis highlights the extent of genomic variation in cultivated and wild rice. Nature genetics 2018, 50, 278–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, P.; et al. Pan-genome analysis of 33 genetically diverse rice accessions reveals hidden genomic variations. Cell 2021, 184, 3542–3558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; et al. Genomic variation in 3,010 diverse accessions of Asian cultivated rice. Nature 2018, 557, 43–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, D.; et al. A pangenome reference of wild and cultivated rice. Nature 2025, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; et al. Rice Gene Index: a comprehensive pan-genome database for comparative and functional genomics of Asian rice. Molecular plant 2023, 16, 798–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornasiero, A.; et al. Oryza genome evolution through a tetraploid lens. Nature Genetics 2025, 57, 1287–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Long, W.; et al. Genome evolution and diversity of wild and cultivated rice species. Nature Communications 2024, 15, 9994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, H.; et al. Plant pangenomics, current practice and future direction. Agriculture Communications 2024, 100039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; et al. Long-read sequencing of 111 rice genomes reveals significantly larger pan-genomes. Genome Research 2022, 32, 853–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; et al. Identification of natural allelic variation in TTL1 controlling thermotolerance and grain size by a rice super pan-genome. Journal of Integrative Plant Biology 2023, 65, 2541–2551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; et al. Natural Variation of PH8 Allele Improves Architecture and Cold Tolerance in Rice. Rice 2025, 18, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.; et al. Genomic investigation of 18,421 lines reveals the genetic architecture of rice. Science 2024, 385, eadm8762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; et al. Graph pangenome captures missing heritability and empowers tomato breeding. Nature 2022, 606, 527–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayakodi, M. , Schreiber, M., Stein, N. & Mascher, M. Building pan-genome infrastructures for crop plants and their use in association genetics. DNA Research 2021, 28, dsaa030. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, L.; et al. GWAS meta-analysis using a graph-based pan-genome enhanced gene mining efficiency for agronomic traits in rice. Nature Communications 2025, 16, 3171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varshney, R.K.; et al. A chickpea genetic variation map based on the sequencing of 3,366 genomes. Nature 2021, 599, 622–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, C. , Chen, Z. & Liang, C. Oryza pan-genomics: A new foundation for future rice research and improvement. The Crop Journal 2021, 9, 622–632. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; et al. A pangenome analysis pipeline provides insights into functional gene identification in rice. Genome Biology 2023, 24, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; et al. Pangenome-wide association study and transcriptome analysis reveal a novel QTL and candidate genes controlling both panicle and leaf blast resistance in rice. Rice 2024, 17, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woldegiorgis, S.T.; et al. Identification of heat-tolerant genes in non-reference sequences in rice by integrating pan-genome, transcriptomics, and QTLs. Genes 2022, 13, 1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daware, A.; et al. Rice Pangenome Genotyping Array: an efficient genotyping solution for pangenome-based accelerated genetic improvement in rice. The Plant Journal 2023, 113, 26–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naithani, S. , Deng, C.H., Sahu, S.K. & Jaiswal, P. Exploring pan-genomes: an overview of resources and tools for unraveling structure, function, and evolution of crop genes and genomes. Biomolecules 2023, 13, 1403. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, W.; et al. A barley pan-transcriptome reveals layers of genotype-dependent transcriptional complexity. Nature Genetics 2025, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, H.; et al. The pan-tandem repeat map highlights multiallelic variants underlying gene expression and agronomic traits in rice. Nature Communications 2024, 15, 7291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chodavarapu, R.K.; et al. Transcriptome and methylome interactions in rice hybrids. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2012, 109, 12040–12045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.K.; et al. Mapping genomic regulation of kidney disease and traits through high-resolution and interpretable eQTLs. Nature communications 2023, 14, 2229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, H. , Li, R., Zhao, J., Batley, J. & Edwards, D. Technological development and advances for constructing and analyzing plant pangenomes. Technological development and advances for constructing and analyzing plant pangenomes. Genome biology and Evolution 2024, 16, evae081. [Google Scholar]

- Garrison, E.; et al. Variation graph toolkit improves read mapping by representing genetic variation in the reference. Nature biotechnology 2018, 36, 875–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eggertsson, H.P.; et al. GraphTyper2 enables population-scale genotyping of structural variation using pangenome graphs. Nature communications 2019, 10, 5402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Z.-Z. , He, J.-B. & Jiao, W.-B. A comprehensive benchmark of graph-based genetic variant genotyping algorithms on plant genomes for creating an accurate ensemble pipeline. Genome Biology 2024, 25, 91. [Google Scholar]

- Miao, Z. & Yue, J.-X. Interactive visualization and interpretation of pangenome graphs by linear reference–based coordinate projection and annotation integration. Genome Research 2025, 35, 296–310. [Google Scholar]

- Li, W.; et al. Plant pan-genomics: recent advances, new challenges, and roads ahead. Journal of Genetics and Genomics 2022, 49, 833–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, C.; et al. RPAN: rice pan-genome browser for∼ 3000 rice genomes. Nucleic acids research 2017, 45, 597–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; et al. Smart breeding driven by big data, artificial intelligence, and integrated genomic-enviromic prediction. Molecular Plant 2022, 15, 1664–1695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, S. , Srivastava, A.K., Khan, A.W., Tran, L.-S.P. & Nguyen, H.T. The era of panomics-driven gene discovery in plants. Trends in Plant Science 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, X.; et al. A quantitative genomics map of rice provides genetic insights and guides breeding. Nature Genetics 2021, 53, 243–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; et al. A rice variation map derived from 10 548 rice accessions reveals the importance of rare variants. Nucleic Acids Research 2023, 51, 10924–10933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H. , Danilevicz, M.F., Li, C. & Edwards, D. Pangenomics and Machine Learning in Improvement of Crop Plants. in Plant Molecular Breeding in Genomics Era: Concepts and Tools 321-347 (Springer, 2024).

- Bayer, P.E.; et al. The application of pangenomics and machine learning in genomic selection in plants. The Plant Genome 2021, 14, e20112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, C. , Liu, Y.H. & Zhou, X.M. VolcanoSV enables accurate and robust structural variant calling in diploid genomes from single-molecule long read sequencing. Nature Communications 2024, 15, 6956. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, J.; et al. SVision: a deep learning approach to resolve complex structural variants. Nature methods 2022, 19, 1230–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; et al. Revolutionizing Crop Breeding: Next-Generation Artificial Intelligence and Big Data-Driven Intelligent Design. Engineering 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakoor, N. , Northrup, D., Murray, S. & Mockler, T.C. Big data driven agriculture: big data analytics in plant breeding, genomics, and the use of remote sensing technologies to advance crop productivity. The Plant Phenome Journal 2019, 2, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Varshney, R.K.; et al. Designing future crops: genomics-assisted breeding comes of age. Trends in plant science 2021, 26, 631–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lisboa, P.J. , Saralajew, S., Vellido, A., Fernández-Domenech, R. & Villmann, T. The coming of age of interpretable and explainable machine learning models. Neurocomputing 2023, 535, 25–39. [Google Scholar]

- Talabi, A.O.; et al. Orphan crops: a best fit for dietary enrichment and diversification in highly deteriorated marginal environments. Frontiers in Plant Science 2022, 13, 839704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murmu, S.; et al. A review of artificial intelligence-assisted omics techniques in plant defense: current trends and future directions. Frontiers in Plant Science 2024, 15, 1292054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Dijk, A.D.J. , Kootstra, G., Kruijer, W. & de Ridder, D. Machine learning in plant science and plant breeding. Machine learning in plant science and plant breeding. Iscience 2021, 24. [Google Scholar]

- Ghamkhar, K. , Hay, F.R., Engbers, M., Dempewolf, H. & Schurr, U. Realizing the potential of plant genetic resources: the use of phenomics for genebanks. Plants, People, Planet 2025, 7, 23–32. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C. , Hu, S., Gardner, C. & Lübberstedt, T. Emerging avenues for utilization of exotic germplasm. Trends in Plant Science 2017, 22, 624–637. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, O.X.; et al. Marker-free carotenoid-enriched rice generated through targeted gene insertion using CRISPR-Cas9. Nature communications 2020, 11, 1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, L.; et al. A super pan-genomic landscape of rice. Cell Research 2022, 32, 878–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, H.; et al. Unravelling inversions: Technological advances, challenges, and potential impact on crop breeding. Plant biotechnology journal 2024, 22, 544–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varshney, R.K.; et al. Analytical and decision support tools for genomics-assisted breeding. Trends in plant science 2016, 21, 354–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayer, P.E. , Golicz, A.A., Scheben, A., Batley, J. & Edwards, D. Plant pan-genomes are the new reference. Nature plants 2020, 6, 914–920. [Google Scholar]

- Tuggle, C.K.; et al. Current challenges and future of agricultural genomes to phenomes in the USA. Genome biology 2024, 25, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz, M.A. & Masmoudi, K. Molecular breakthroughs in modern plant breeding techniques. Horticultural Plant Journal 2025, 11, 15–41. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, D.; et al. A syntelog-based pan-genome provides insights into rice domestication and de-domestication. Genome Biology 2023, 24, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monat, C.; et al. De novo assemblies of three Oryza glaberrima accessions provide first insights about pan-genome of African rices. Genome biology and evolution 2017, 9, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).