1. Introduction

Ionic liquids (ILs) are widely recognized as ionic compounds that remain liquid at relatively low temperatures below 100°C [

1,

2,

3,

4]. In addition to their characteristic thermal stability and low volatility, these compounds permit to tune their physicochemical properties by structural modifications in both, cations and anions, as well as by combining diverse cations and anions [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21]. This structural adaptability has facilitated the development of ILs for more sophisticated applications [

22]. Whereas early-generation ILs were primarily employed for industrial purposes, nowadays, ILs are increasingly been explored for biological applications [

22]. Thefore, it becomes necessary to address significant challenges related with their potentially toxic interactions with living organisms [

23,

24]. The growing interest in biological applications of ILs has emerged in part as a response to environmental concerns associated with the ecotoxicity of certain IL classes [

23,

24]. Particular attention has been given to the cytotoxicity of imidazolium-based ILs, which stems from their strong interactions with phospholipid membranes in cellular structures [

25,

26,

27].

The cytotoxic effects of imidazolium ILs appear directly correlated with their membrane-disrupting capabilities. Experimental studies have demonstrated that these cations intercalate into lipid bilayers, inducing perturbations that range from moderate fluidity alterations to complete membrane disintegration, depending on their specific molecular architecture [

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30]. A comprehensive understanding of these interaction mechanisms is essential for developing safe pharmaceutical and medical applications of ILs [

28,

29]. Cytotoxicity assessments across various biological systems, including antifungal and bactericidal tests as well as mammalian cell exposure studies, have revealed that both, cation-anion combinations and alkyl chain lengths, play crucial roles in determining toxicity profiles [

1,

31,

32]. These observed structure-activity relationships highlight the need for more detailed mechanistic studies on IL-membrane interactions.

Recent advances in computational chemistry have provided valuable theoretical insights into the interactions between imidazolium ILs and phospholipid bilayers [

33,

34,

35]. Current computational models primarily focus on two aspects: the structural modifications induced in the bilayer and the molecular mechanisms governing cation insertion and stabilization within membranes. The stabilization of incorporated cations appears to involve both electrostatic interactions with phosphate groups and hydrophobic effects mediated by alkyl side chains [

33,

34,

35]. However, these studies describe in general dialkylated cations with a fixed methyl group [

36]. Dialkyl-substituted variants remain relatively unexplored. The presence of two longer alkyl chains may significantly alter both, the insertion dynamics and the membrane perturbation patterns, due to additional steric constraints in the polar headgroup region.

Herein, we employ atomistic molecular dynamics simulations to systematically investigate the interaction of 1-hexadecyl-3-nalkyl-imidazolium cations (where n represents the number saturated carbons in the second alkyl chain) with 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (POPC) bilayers, focusing particularly on the structural perturbations induced in the membrane. These simulations provide atomic-level insights into IL-membrane interactions, serving as a tool for elucidating the fundamental molecular mechanisms underlying in IL cytotoxicity.

2. Materials and Methods

We performed molecular dynamics simulations on systems containing a hydrated POPC phospholipid bilayer composed of 128 lipids (64 per leaflet) incorporating 1-hexadecyl-3-nalkyl-imidazolium cations using the GROMACS software package [

37]. Each simulated system contained the solvated bilayer along with four ion pairs, with the cationic component consisting of [C₁₆MIM] (1-hexadecyl-3-methylimidazolium), [C₁₆BMIM] (1-hexadecyl-3-butylimidazolium), or [C₁₆OMIM] (1-hexadecyl-3-octylimidazolium), and the chloride (Cl⁻) anion. The molecular structures of the utilized cations are presented in

Figure 1. The pre-equilibrated POPC bilayer system has been obtained from the Slipids database [

38], with the ionic liquid structures and force fields generated following the AMBER protocol methodology [

39,

40]. This approach ensured proper system preparation while maintaining consistency with established computational chemistry standards for membrane simulations.

The simulations were conducted in the isothermal-isobaric (NPT) ensemble. Temperature was maintained at 303 K using the velocity-rescaling algorithm [

41]. The pressure was regulated at 1 bar by the Berendsen barostat [

42] operating in semi-isotropic mode. Three-dimensional periodic boundary conditions were implemented with a 1.4 nm cutoff radius for intermolecular interactions. Long-range electrostatic interactions were calculated using the Particle Mesh Ewald (PME) method [

43] with an identical 1.4 nm cutoff distance. The LINCS algorithm [

44] was employed to maintain all chemical bond constraints throughout the simulations.

The AMBER force field was selected for molecular representations in the simulations with water molecules modeled described by the TIP3P potential [

45]. Ionic pairs were randomly inserted into the hydrated bilayer simulation boxes. Prior to production runs, all systems underwent potential energy minimization using the steepest descent algorithm [

46]. Subsequently, simulations were carried out for 100 ns of production time with four cations and chlorides inserted into the bilayer systems. A reference system consisting solely of a hydrated phospholipid bilayer without ionic liquids was subjected to identical simulation protocols and analysis procedures for comparative purposes.

3. Results and Discussions

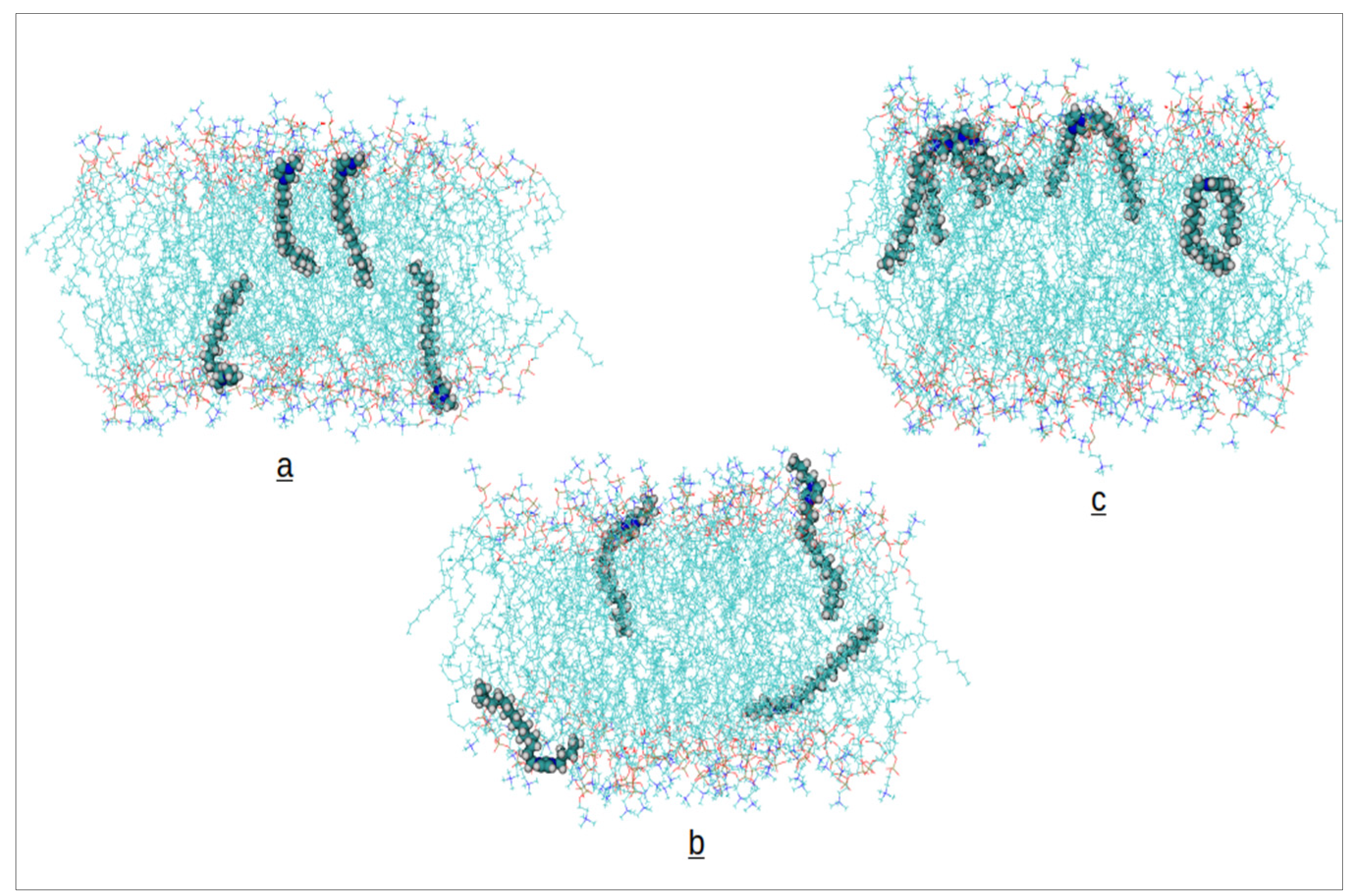

Along the simulations of the bilayer systems containing Ils, we observed in any case the insertion of the cations from the water phase into the phospholipid bilayer. Afterwards, we extended the simulations up to 100 ns monitoring the convergence of the area per phospholipid (APL) and interactions energies between cations and bilayer molecules. The final 10 ns of each trajectory have been utilized to compute the results presented in the following. A snapshot of the final configuration for each system is presented in

Figure 2.

At a glance, we observe the configurations of cations inserted into the bilayer. The [C₁₆OMIM] cation inserts both alkyl chains into the hydrophobic environment of the bilayer. The [C₁₆BMIM] cation, containing the shorter butyl chain (4 carbons), can not fully insert the second substituent into the hydrophobic domain, leaving it closer to the polar headgroups at the membrane surface. As exptected, [C₁₆MIM] directs only the long alkyl chain towards the membrane’s center.

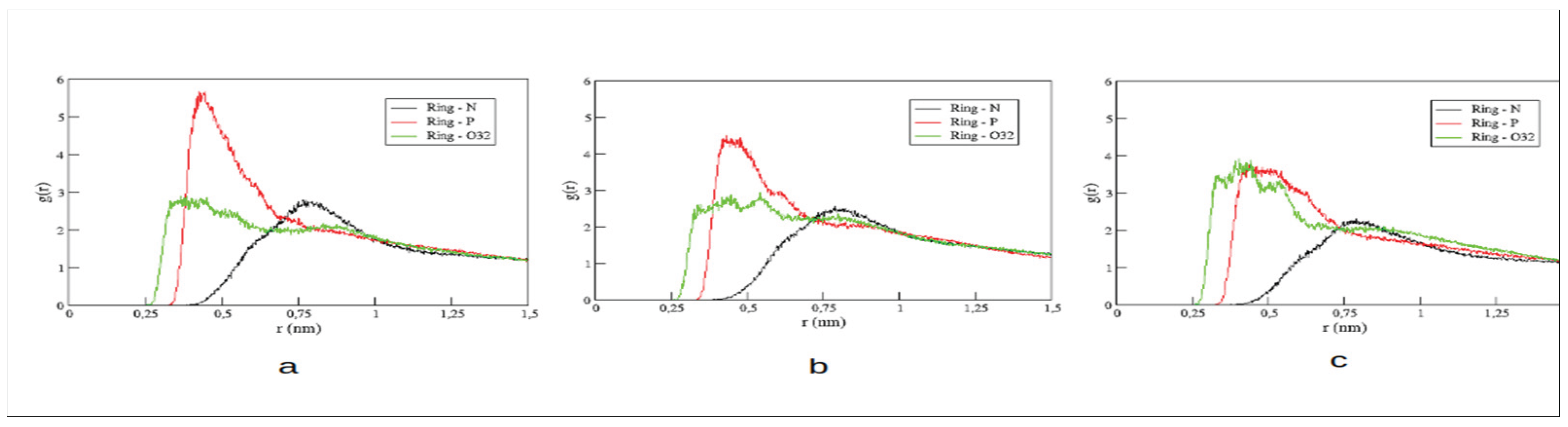

Radial pair distribution functions (RDFs) for distances between the center of the imidazolium ring and three distinct atoms of POPC’s polar head group have been computed. We have chosen the nitrogen atom of the choline group (N), the phosphorous (P), and the innermost oxygen (O) of the glycerol backbone to monitor changes in the coordination of the imidazolium ring within the membrane’s polar region. The RDFs are illustrated in

Figure 3.

In general, peak positions of these RDFs are maintained. Both, the imidazolium ring and choline group contain positive charge distributions. Thus, not surprisingly, the RDF with choline’s nitrogen presents maximum amplitudes at larger distances than the other RDFs and appear only slightly affected by the second alkyl substitution in the cations. The [C₁₆MIM] cation presents the most intense peak with the negatively charged phosphate group. Increasing the second alkyl chain, the amplitude of this peak is decreased accompanied by larger amplitudes in the RDF with the oxygen of POPC’s glycerol unit. This observation indicates that longer second alkyl chains favor a deaper insertion of the cation into the membrane.

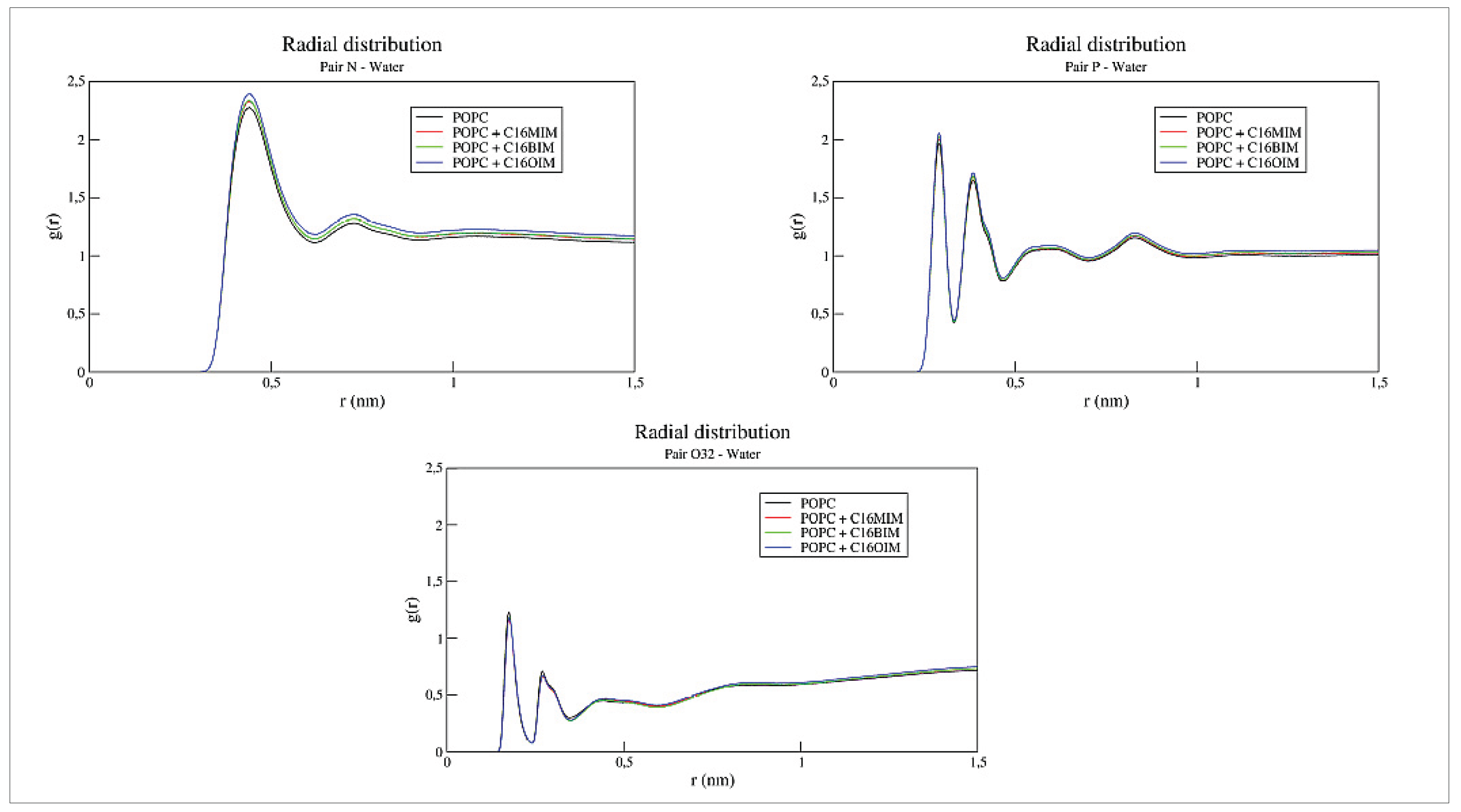

Figure 4 presents RDFs between water molecules and the aforementioned headgroup atoms of the bilayer. Comparing these functions demonstrates no significant changes in the hydration patterns of the membrane surface. These results indicate that the cation insertion does not promote water intrusion into the bilayer’s hydrophobic domain, preserving the membrane’s fundamental barrier properties despite the structural perturbations caused by the ionic liquids.

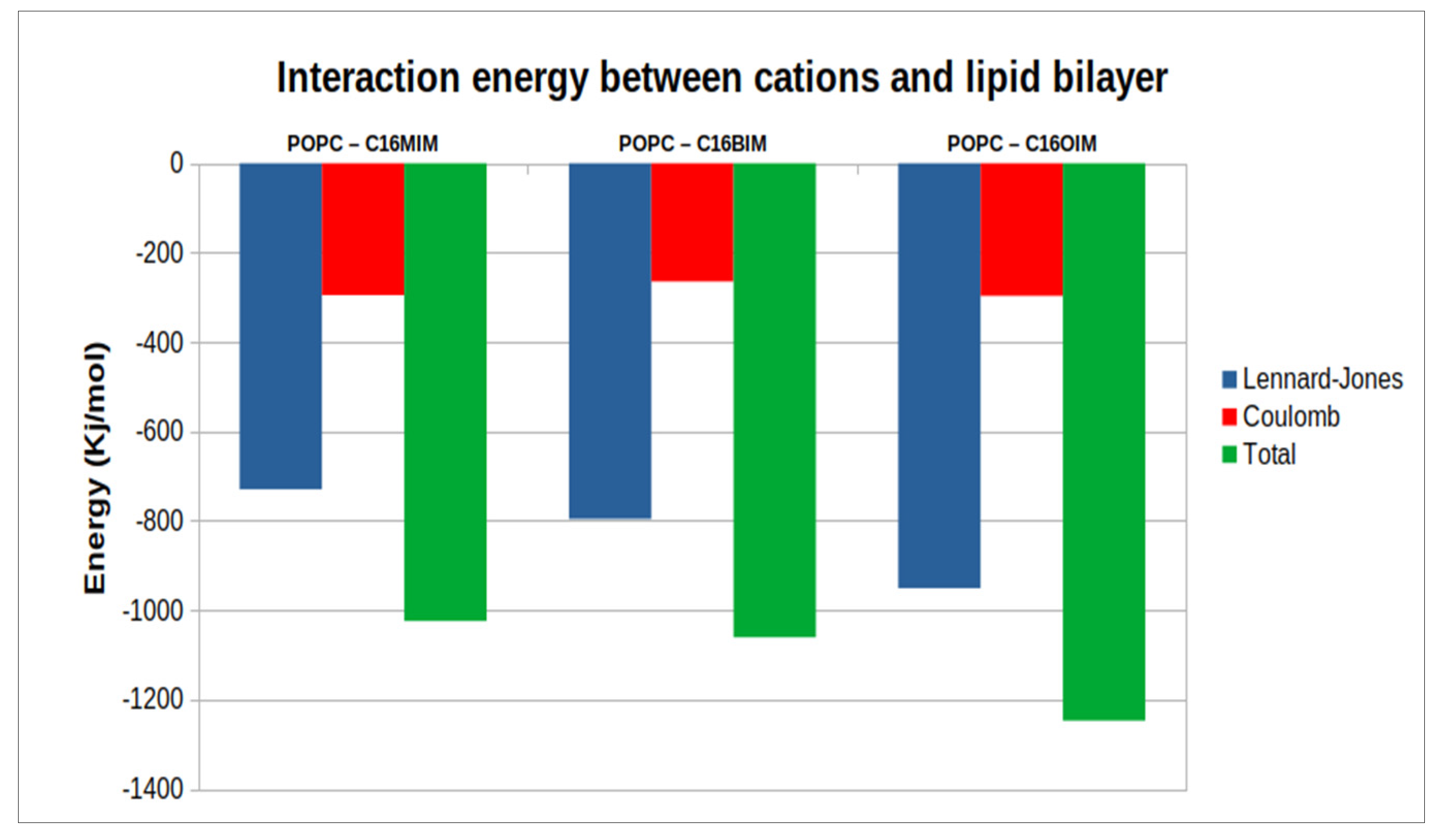

The interaction energy between the cations and the phospholipid molecules has been separated into contributions stemming from Lennard-Jones and Coulomb interactions as depicted in

Figure 5. More negative values in this analysis indicate stronger contributions to the overall interaction energy within the system. The total interaction energy is increased by adding more atoms to the cations as one might expect. The electrostatic contributions are mostly due to interactions of the cation’s ring and the head group atoms of the membrane and are almost the same for the three cations. On the other side, increasing the second alkyl chain in the cations comes along with enhanced Lennard-Jones interactions. A large fraction of these van der Waals type interactions reflects the hydrophobic interactions between the alkyl chains of the cations and the lipid tails and, therefore, grows strongly with larger alkyl groups in the cations.

In

Table 1, we have summarized several structural data for the bilayer in comparison with the unperturbed POPC bilayer. We focused on the area per phospholipid (APL) and the membrane’s thickness computed with the APL@Voro post-processing software [

48].

The APL and thickness of the unperturbed bilayer are in agreement with literature data [

49]. Our POPC membrane contains 128 phospholipid molecules and four cations which represents a molar fraction of approximately 0.03. We observed slightly increased APLs due to the presence of the cations without a clear tendency. The computed differences in the APLs are smaller than the statistical uncertainty of the numerical values. This holds also for the membrane’s thickness exhibiting numerical values within the error range for the unperturbed bilayer. As outlined by

Figure 2, in the case of the [C₁₆BMIM] cation, all the four cations inserted into the same leaflet of the membrane, whereas in the other systems, each leaflet contains two cations causing the apparentely different trends in the APLs and thicknesses. The membrane structural results obtained for the C16MIM cation are in good agreement with values reported in the literature [

36] for studies involving smaller monoalkylated cations such as C12MIM, showing that the new data generated for dialkylated cations have good reliability.

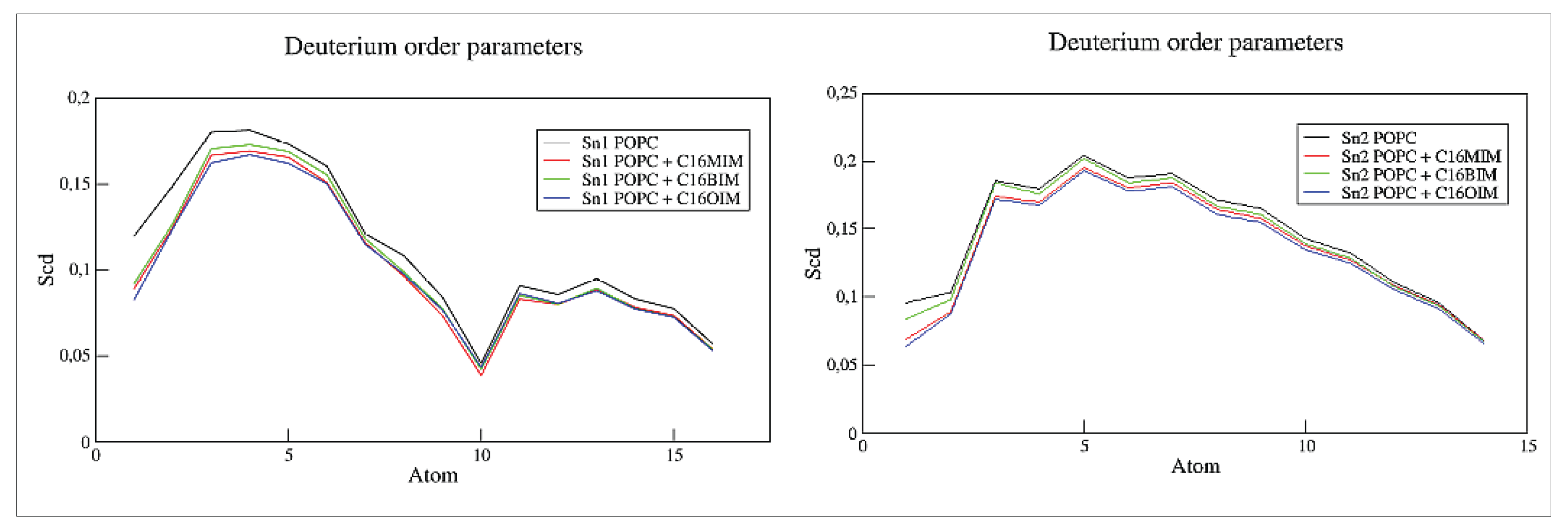

In

Figure 6, we illustrate the deuterium order parameter for the unsaturated (left panel) and saturated (right panel) alkyl chains of the POPC molecules calculated with the gmx order module of the GROMACS software. The presence of the cations quite generally reduces slightly the order parameter affecting more the carbons close to the membrane’s head group than those close to the membrane’s center

4. Conclusions

Ionic liquids based on the imidazolium cation containing a fixed hexadecyl substituent and a substituent ranging from methyl, butyl and octyl with chloride as the counterion were inserted into hydrated POPC-type phospholipid bilayers. MD simulations of 100 nanoseconds were performed to evaluate the structural effects on the bilayer promoted by the presence of the cations. The stabilization of the cations in the membrane occurs through nonpolar interactions within the bilayer between carbon chains of the cations and lipids and through polar interactions on the membrane surface between the head groups of the phospholipids and the rings present in the cations. Increasing the second alkyl chain in the cations favor configurations with deeper inserted cations. Four inserted cations do not promote significant changes in the overall structure of the membrane’s (area per lipid and thickness), but decrease the deuterium order parameter for POPC chain carbons close to the head groups. In any case, the simulated systems describe stable bilayers without changes in the hydration patterns.

Funding

This study was financed in part by the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior – Brasil (CAPES) – Finance Code 001.

Acknowledgments

Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul, the Department of Materials (DEMAT), the Institute of Chemistry and the Group of Computational Theoretical Chemistry for all the support provided and the infrastructure provided.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| IL’s |

Ionic liquids |

| POPC |

1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine |

| C16MIM |

1-Hexadecyl-3 -Methylimidazolium |

| C16BIM |

1-Hexadecyl-3 -Butylimidazolium |

| C168OIM |

1-Hexadecyl-3-Octylimidazolium |

| MD |

Molecular dynamics |

| APL |

Area per lipid |

| RDF |

Radial pair distribution functions |

| NPT |

Isothermal-isobaric ensemble |

| PME |

Particle Mesh Ewald |

References

- Walden, Paul. “Molecular weights and electrical conductivity of several fused salts.” Bull. Acad. Imper. Sci.(St. Petersburg) 1800 (1914).

- Chum, Helena L., et al. “Electrochemical scrutiny of organometallic iron complexes and hexamethylbenzene in a room temperature molten salt.” Journal of the American Chemical Society 97.11 (1975): 3264-3265. [CrossRef]

- De Long, Hugh C. “Structure of 1-ethyl-3-methylimidazolium hexafluorophosphate: model for room temperature molten salts.” Journal of the Chemical Society, Chemical Communications 3 (1994): 299-300.

- Wilkes, John S., and Michael J. Zaworotko. “Air and water stable 1-ethyl-3-methylimidazolium based ionic liquids.” Journal of the Chemical Society, Chemical Communications 13 (1992): 965-967. [CrossRef]

- Fredlake, Christopher P., et al. “Thermophysical properties of imidazolium-based ionic liquids.” Journal of Chemical & Engineering Data 49.4 (2004): 954-964. [CrossRef]

- Raabe, Gabriele, and Jürgen Köhler. “Thermodynamical and structural properties of imidazolium based ionic liquids from molecular simulation.” The Journal of chemical physics 128.15 (2008). [CrossRef]

- Weingärtner, Hermann. “Understanding ionic liquids at the molecular level: facts, problems, and controversies.” Angewandte Chemie International Edition 47.4 (2008): 654-670.

- Zhang, Suojiang, et al. “Physical properties of ionic liquids: database and evaluation.” Journal of physical and chemical reference data 35.4 (2006): 1475-1517. [CrossRef]

- Bonhote, Pierre, et al. “Hydrophobic, highly conductive ambient-temperature molten salts.” Inorganic chemistry 35.5 (1996): 1168-1178.

- Tokuda, Hiroyuki, et al. “Physicochemical properties and structures of room temperature ionic liquids. 1. Variation of anionic species.” The Journal of Physical Chemistry B 108.42 (2004): 16593-16600.

- McEwen, Alan B., et al. “Electrochemical properties of imidazolium salt electrolytes for electrochemical capacitor applications.” Journal of the Electrochemical Society 146.5 (1999): 1687. [CrossRef]

- Hyun, Byung-Ryool, et al. “Intermolecular dynamics of room-temperature ionic liquids: femtosecond optical Kerr effect measurements on 1-alkyl-3-methylimidazolium bis ((trifluoromethyl) sulfonyl) imides.” The Journal of Physical Chemistry A 106.33 (2002): 7579-7585. [CrossRef]

- Every, Hayley A., et al. “Transport properties in a family of dialkylimidazolium ionic liquids.” Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics 6.8 (2004): 1758-1765. [CrossRef]

- Huddleston, Jonathan G., et al. “Characterization and comparison of hydrophilic and hydrophobic room temperature ionic liquids incorporating the imidazolium cation.” Green chemistry 3.4 (2001): 156-164.

- Tsuzuki, Seiji, et al. “Magnitude and directionality of interaction in ion pairs of ionic liquids: Relationship with ionic conductivity.” The Journal of Physical Chemistry B 109.34 (2005): 16474-16481. [CrossRef]

- Fitchett, Brian D., Travis N. Knepp, and John C. Conboy. “1-Alkyl-3-methylimidazolium bis (perfluoroalkylsulfonyl) imide water-immiscible ionic liquids: the effect of water on electrochemical and physical properties.” Journal of the Electrochemical Society 151.7 (2004): E219.

- McFarlane, D. R., et al. “High conductivity molten salts based on the imide ion.” Electrochimica Acta 45.8-9 (2000): 1271-1278. [CrossRef]

- Hyk, Wojciech, et al. “Properties of microlayers of ionic liquids generated at microelectrode surface in undiluted redox liquids. Part II.” The Journal of Physical Chemistry B 105.29 (2001): 6943-6949. [CrossRef]

- Earle, Martyn J., et al. “The distillation and volatility of ionic liquids.” Nature 439.7078 (2006): 831-834. [CrossRef]

- Zaitsau, Dzmitry H., et al. “Experimental vapor pressures of 1-alkyl-3-methylimidazolium bis (trifluoromethylsulfonyl) imides and a correlation scheme for estimation of vaporization enthalpies of ionic liquids.” The Journal of Physical Chemistry A 110.22 (2006): 7303-7306. [CrossRef]

- Köddermann, Thorsten, Dietmar Paschek, and Ralf Ludwig. “Ionic liquids: Dissecting the enthalpies of vaporization.” ChemPhysChem 9.4 (2008): 549-555. [CrossRef]

- Egorova, Ksenia S., Evgeniy G. Gordeev, and Valentine P. Ananikov. “Biological activity of ionic liquids and their application in pharmaceutics and medicine.” Chemical reviews 117.10 (2017): 7132-7189. [CrossRef]

- Wei, Penghao, et al. “Emerging impacts of ionic liquids on eco-environmental safety and human health.” Chemical Society Reviews 50.24 (2021): 13609-13627. [CrossRef]

- Liu, R., et al. “Progress in environmental behaviors and safety of ionic liquids.” Chinese Sci. Bull 64 (2019): 3158-3164.

- Galluzzi, Massimiliano, et al. “Interaction of imidazolium-based ionic liquids with supported phospholipid bilayers as model biomembranes.” Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics 24.44 (2022): 27328-27342. [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, Margarida M., et al. “Ionic liquids as biocompatible antibacterial agents: a case study on structure-related bioactivity on Escherichia coli.” ACS applied bio materials 5.11 (2022): 5181-5189.

- Flieger, Jolanta, and Michał Flieger. “Ionic liquids toxicity—benefits and threats.” International Journal of Molecular Sciences 21.17 (2020): 6267.

- Galluzzi, Massimiliano, et al. “Interaction of imidazolium-based ionic liquids with supported phospholipid bilayers as model biomembranes.” Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics 24.44 (2022): 27328-27342. [CrossRef]

- Gupta, Ritika, et al. “1, 3 Dialkylated Imidazolium Ionic Liquid Causes Interdigitated Domains in a Phospholipid Membrane.” Langmuir 38.11 (2022): 3412-3421.

- Hitaishi, Prashant, et al. “Cholesterol-controlled interaction of ionic liquids with model cellular membranes.” Langmuir 39.27 (2023): 9396-9405. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, Veerendra K., et al. “Enhanced microscopic dynamics of a liver lipid membrane in the presence of an ionic liquid.” Frontiers in chemistry 8 (2020): 577508. [CrossRef]

- Klähn, Marco, and Martin Zacharias. “Transformations in plasma membranes of cancerous cells and resulting consequences for cation insertion studied with molecular dynamics.” Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics 15.34 (2013): 14427-14441. [CrossRef]

- Bingham, Richard J., and Pietro Ballone. “Computational study of room-temperature ionic liquids interacting with a POPC phospholipid bilayer.” The Journal of Physical Chemistry B 116.36 (2012): 11205-11216. [CrossRef]

- Lee, Hwankyu. “Effects of imidazolium-based ionic surfactants on the size and dynamics of phosphatidylcholine bilayers with saturated and unsaturated chains.” Journal of Molecular Graphics and Modelling 60 (2015): 162-168. [CrossRef]

- Lim, Geraldine S., Stephan Jaenicke, and Marco Klähn. “How the spontaneous insertion of amphiphilic imidazolium-based cations changes biological membranes: a molecular simulation study.” Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics 17.43 (2015): 29171-29183. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, Sandeep, et al. “Effect of the alkyl chain length of amphiphilic ionic liquids on the structure and dynamics of model lipid membranes.” Langmuir 35.37 (2019): 12215-12223. [CrossRef]

- Berendsen, Herman JC, David van der Spoel, and Rudi van Drunen. “GROMACS: A message-passing parallel molecular dynamics implementation.” Computer physics communications 91.1-3 (1995): 43-56.

- Jambeck, Joakim PM, and Alexander P. Lyubartsev. “An extension and further validation of an all-atomistic force field for biological membranes.” Journal of chemical theory and computation 8.8 (2012): 2938-2948. [CrossRef]

- De Andrade, Jones, Elvis S. Böes, and Hubert Stassen. “Computational study of room temperature molten salts composed by 1-alkyl-3-methylimidazolium cations force-field proposal and validation.” The journal of physical chemistry B 106.51 (2002): 13344-13351.

- de Andrade, Jones, Elvis S. Böes, and Hubert Stassen. “A force field for liquid state simulations on room temperature molten salts: 1-ethyl-3-methylimidazolium tetrachloroaluminate.” The Journal of Physical Chemistry B 106.14 (2002): 3546-3548.

- Bussi, Giovanni, Davide Donadio, and Michele Parrinello. “Canonical sampling through velocity rescaling.” The Journal of chemical physics 126.1 (2007).

- Berendsen, Herman JC, et al. “Molecular dynamics with coupling to an external bath.” The Journal of chemical physics 81.8 (1984): 3684-3690. [CrossRef]

- Essmann, Ulrich, et al. “A smooth particle mesh Ewald method.” The Journal of chemical physics 103.19 (1995): 8577-8593.

- Hess, Berk, et al. “LINCS: A linear constraint solver for molecular simulations.” Journal of computational chemistry 18.12 (1997): 1463-1472.

- Jorgensen, William L., et al. “Comparison of simple potential functions for simulating liquid water.” The Journal of chemical physics 79.2 (1983): 926-935. [CrossRef]

- Arfken, G., H. Weber, and F. E. Harris. “Fresnel Integrals.” (2018).

- Lee, Hwankyu, and Tae-Joon Jeon. “The binding and insertion of imidazolium-based ionic surfactants into lipid bilayers: The effects of the surfactant size and salt concentration.” Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics 17.8 (2015): 5725-5733.

- Lukat, Gunther, Jens Krüger, and Björn Sommer. “APL@ Voro: a Voronoi-based membrane analysis tool for GROMACS trajectories.” Journal of chemical information and modeling 53.11 (2013): 2908-2925.

- Grote, Fredrik, and Alexander P. Lyubartsev. “Optimization of slipids force field parameters describing headgroups of phospholipids.” The Journal of Physical Chemistry B 124.40 (2020): 8784-8793. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).