Submitted:

12 June 2025

Posted:

12 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Experimental

2.1. Sample Collection and Preliminary Processing

2.2. Infrared Spectroscopy Analysis

2.3. Multivariate Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

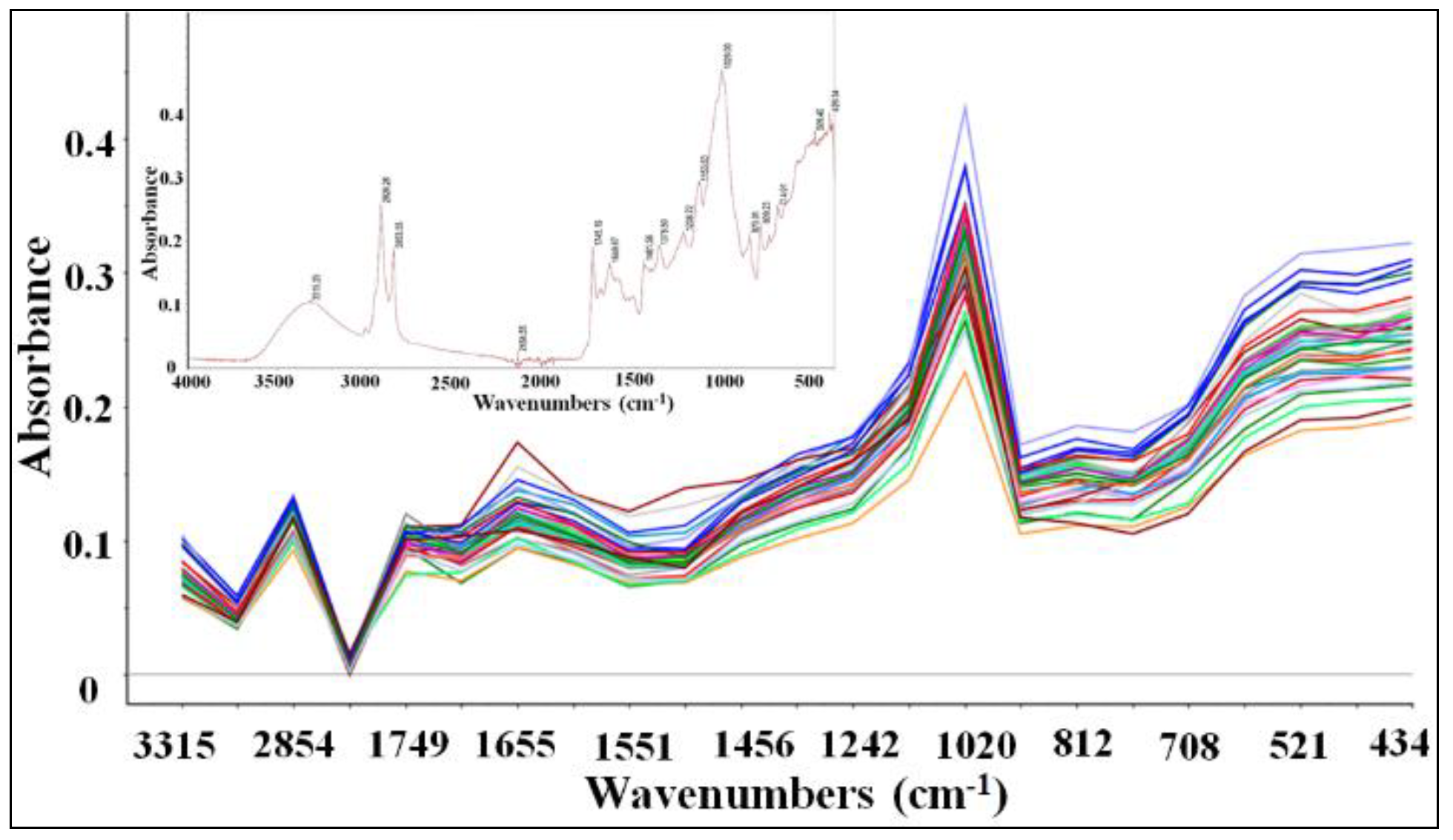

3.1. FTIR Spectral Analysis

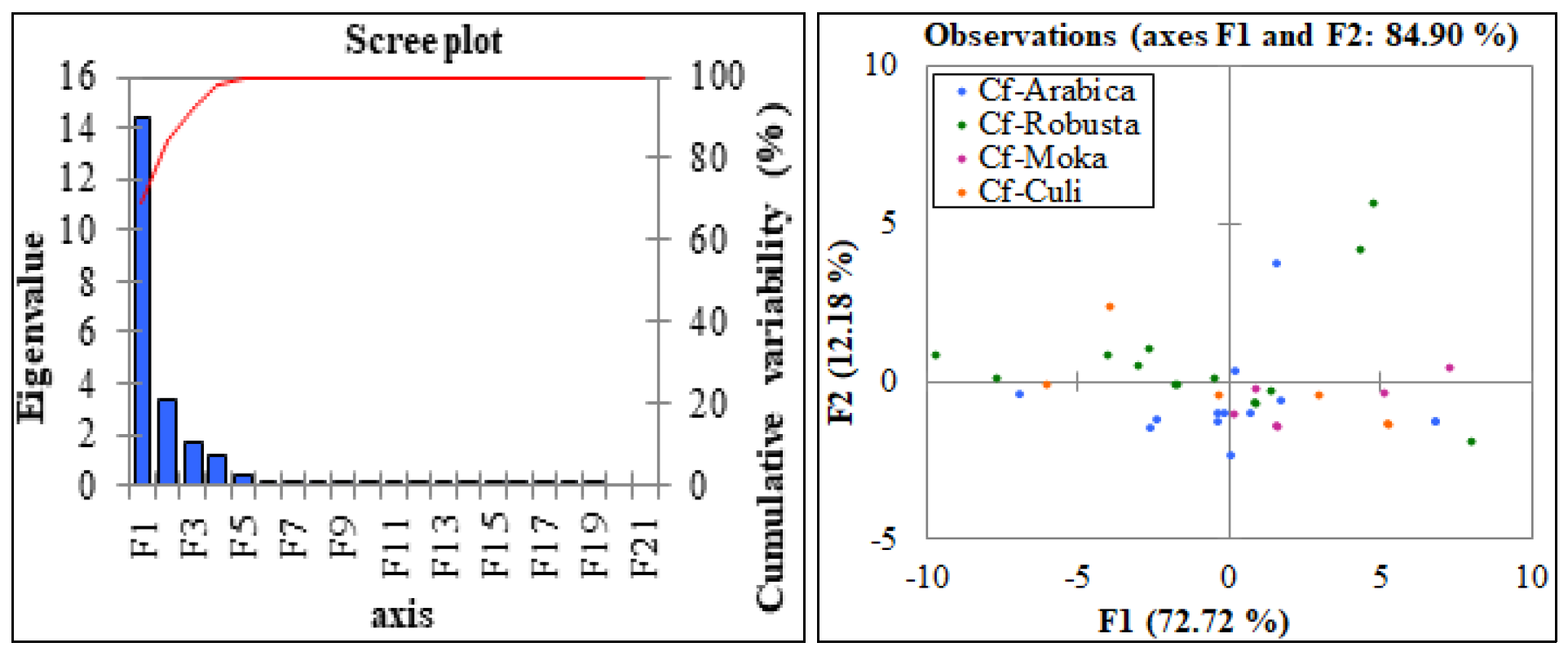

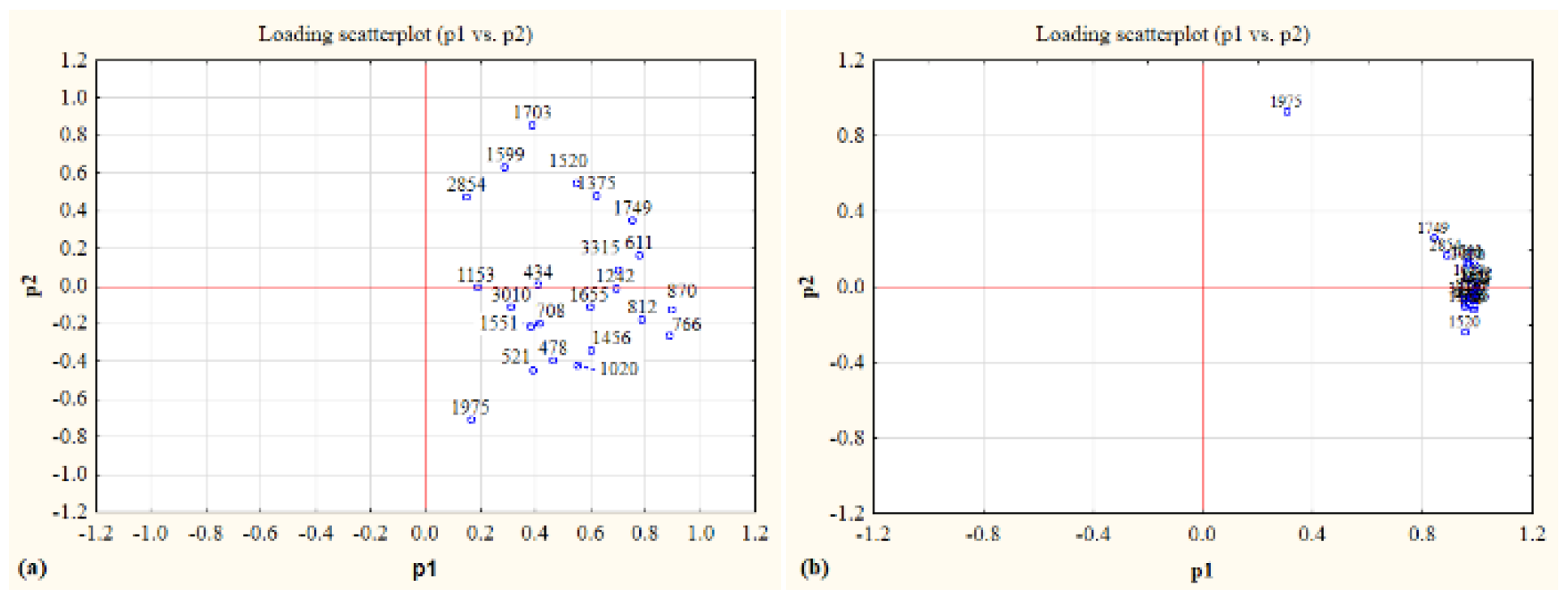

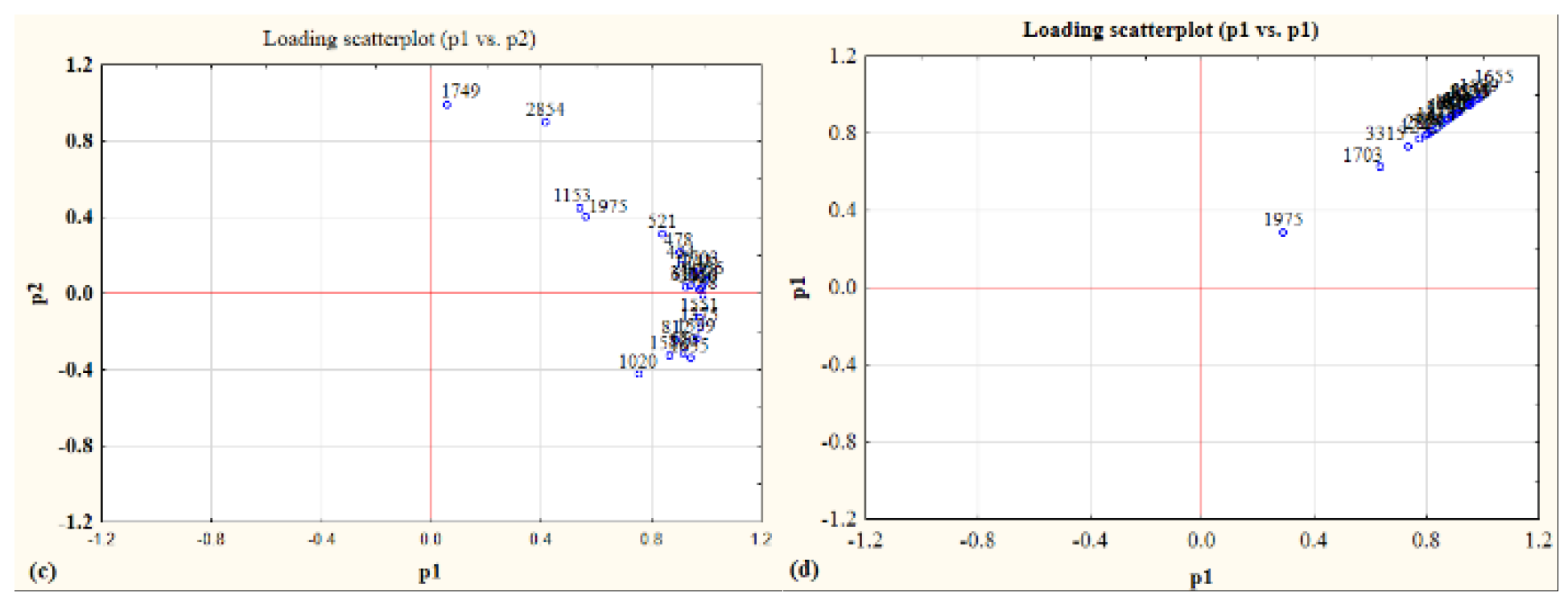

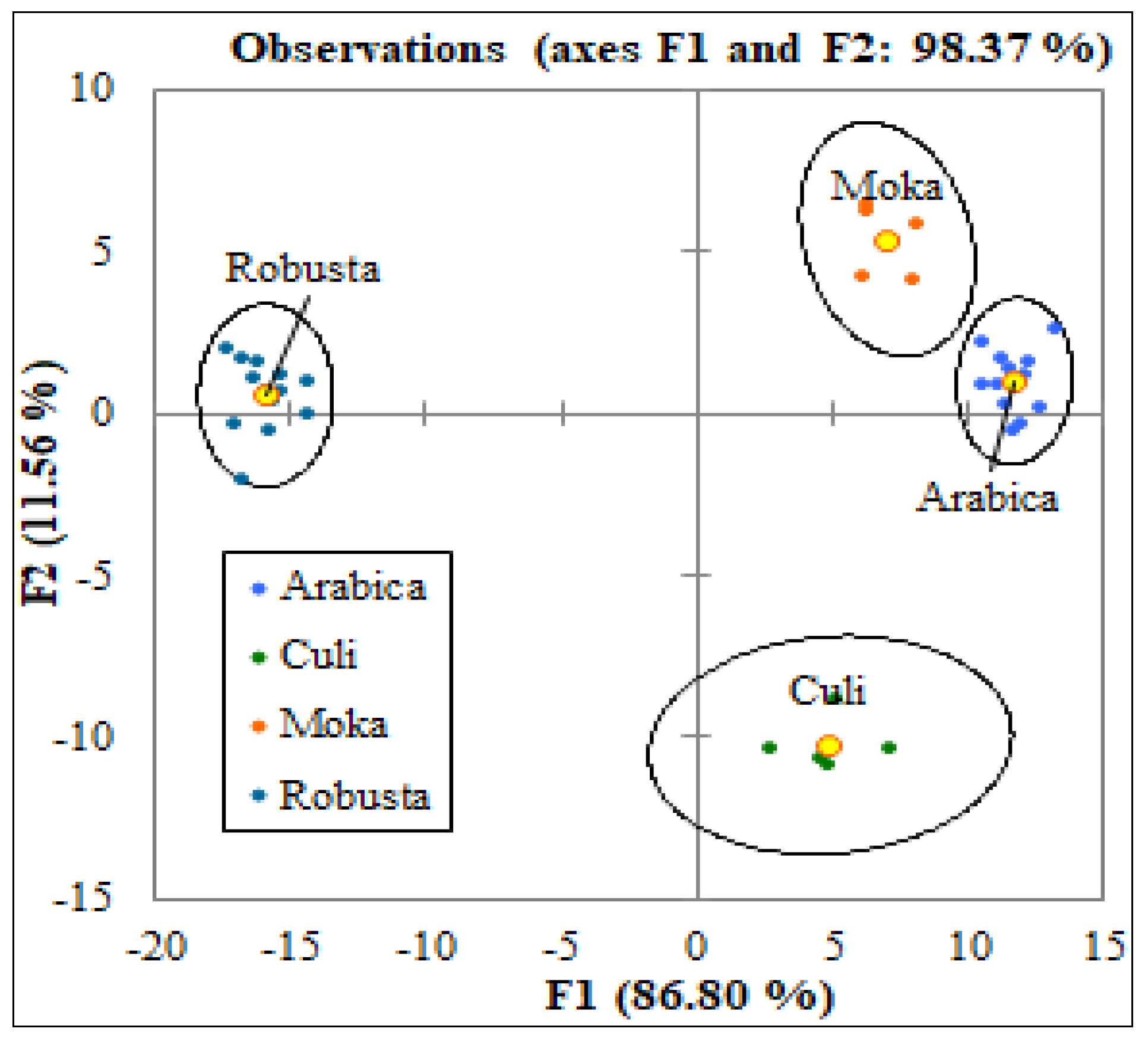

3.2. Application of Principal Component Analysis (PCA)

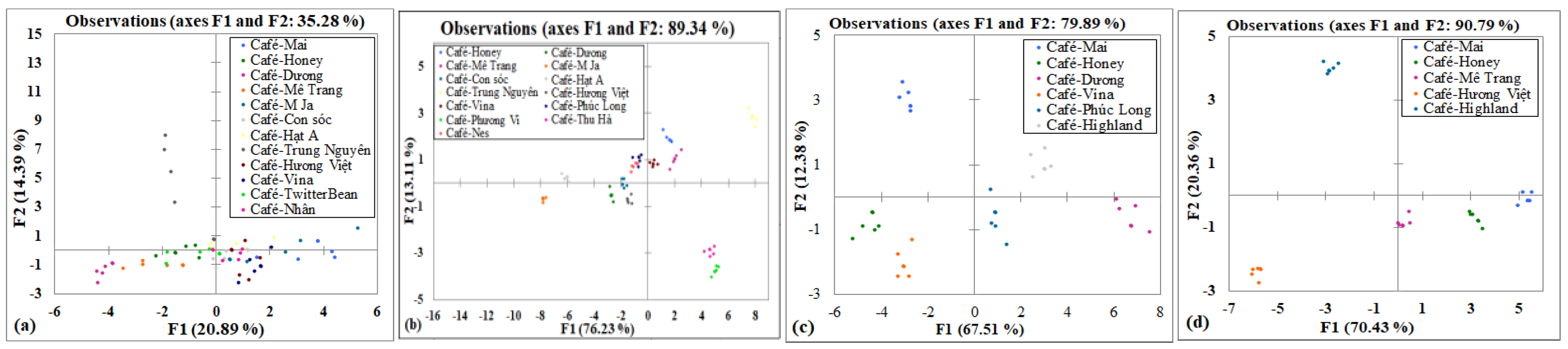

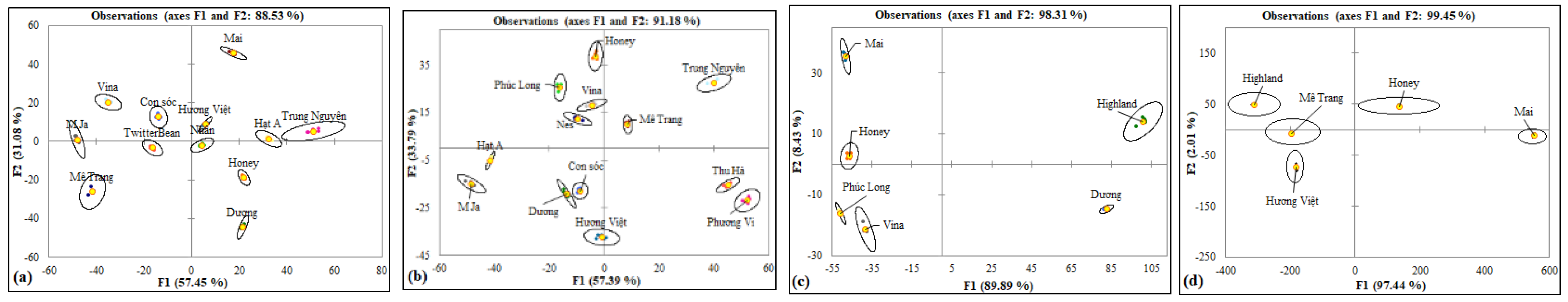

3.3. Application of Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA)

4. Conclusions

References

- United States Department of Agriculture Report VM2020-0052. 2020.

- Vietnam Trade Promotion Agency. Vietnam Coffee Industry Report. 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Ukers, W. All About Coffee United States Department of Agriculture. 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Caporaso, N.; Whitworth, M.B.; Cui, C.; Fisk, I.D. Variability of single bean coffee volatile compounds of Arabica and robusta roasted coffees analysed by SPME-GC-MS. Food Research International 2018, 108, 628–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferruzzi, M.G. The influence of beverage composition on delivery of phenolic compounds from coffee and tea. Physiology & Behavior 2010, 100, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flament, I. Coffee flavor chemistry. West Sussex: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. International Coffee Council. Country Coffee Profile: Vietnam. 124th Session 25–29 March 2019 Nairobi, Kenya.

- Lim, T.K. Coffea liberica. Edible Medicinal and Non-Medicinal Plants 2012, 710–714. [Google Scholar]

- Hai, Y.D.; Tran-Lam, T.-T.; Nguyen, T.Q.; Vu, N.D.; Ma, K.H.; Le, G.T. Acrylamide in daily food in the metropolitan area of Hanoi, Vietnam. Food Additives & Contaminants: Part B 2019, 12, 159–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, V.N.; Nguyen, Q.T.; Nguyen, T.D.; Nguyen, N.T.; Janda, T.; Szalai, G.; Le, T.G. The potential health risks and environmental pollution associated with the application of plant growth regulators in vegetable production in several suburban areas of Hanoi, Vietnam. Biologia Futura 2020, 71, 323–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.Q.; Le, N.V.; Nguyen, T.N.; Truong, M.N.; Pham, T.T.P.; Nguyen, T.T.; Pham, D.H.; Bui, M.Q.; Nguyen, M.H.N. Analytical method development of Bifenthrin in dried meat-based foods using gas chromatography coupled to mass spectrometry. American Chemical Society (ACS) 2025. [CrossRef]

- Vu-Duc, N.; Nguyen-Quang, T.; Le-Minh, T.; Nguyen-Thi, X.; Tran, T.M.; Vu, H.A.; Nguyen, L.-A.; Doan-Duy, T.; Van Hoi, B.; Vu, C.-T.; et al. Multiresidue Pesticides Analysis of Vegetables in Vietnam by Ultrahigh-Performance Liquid Chromatography in Combination with High-Resolution Mass Spectrometry (UPLC-Orbitrap MS). Journal of Analytical Methods in Chemistry 2019, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, T.T.; Vo, T.A.; Duong, M.T.; Pham, T.M.; Van Nguyen, Q.; Nguyen, T.Q.; Bui, M.Q.; Syrbu, N.N.; Van Do, M. Heavy metals in cultured oysters (Saccostrea glomerata) and clams (Meretrix lyrata) from the northern coastal area of Vietnam. Marine Pollution Bulletin 2022, 184, 114140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, V.N.; Nguyen, Q.T.; Nguyen, T.D.; Nguyen, N.T.; Janda, T.; Szalai, G.; Le, T.G. The potential health risks and environmental pollution associated with the application of plant growth regulators in vegetable production in several suburban areas of Hanoi, Vietnam. Biologia Futura 2020, 71, 323–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.P.L.; Nguyen, V.T.A.; Do, T.T.T.; Nguyen Quang, T.; Pham, Q.L.; Le, T.T. Fatty Acid Composition, Phospholipid Molecules, and Bioactivities of Lipids of the Mud Crab Scylla paramamosain. Journal of Chemistry 2020, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quang Trung, N.; Thi Luyen, N.; Duc Nam, V.; Tien Dat, N. Chemical Composition and in Vitro Biological Activities of White Mulberry Syrup during Processing and Storage. Journal of Food and Nutrition Research 2018, 6, 660–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.Q.; Tran-Lam, T.-T.; Nguyen, H.Q.; Dao, Y.H.; Le, G.T. Assessment of organic and inorganic arsenic species in Sengcu rice from terraced paddies and commercial rice from lowland paddies in Vietnam. Journal of Cereal Science 2021, 102, 103346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bui, M.Q.; Quan, T.C.; Nguyen, Q.T.; Tran-Lam, T.-T.; Dao, Y.H. Geographical origin traceability of Sengcu rice using elemental markers and multivariate analysis. Food Additives & Contaminants: Part B 2022, 15, 177–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bui, D.T.; Truong, N.M.; Le, V.A.; Nguyen, H.K.; Bui, Q.M.; Pham, V.T.; Nguyen, Q.T. Preserving the Authenticity of ST25 Rice (Oryza sativa) from the Mekong Delta: A Multivariate Geographical Characterization Approach. Stresses 2023, 3, 653–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, L.H.T.; Tran-Lam, T.-T.; Nguyen, H.Q.; Quan, T.C.; Nguyen, T.Q.; Nguyen, D.T.; Dao, Y.H. A study on multi-mycotoxin contamination of commercial cashew nuts in Vietnam. Journal of Food Composition and Analysis 2021, 102, 104066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen-Quang, T.; Bui-Quang, M.; Pham-Van, T.; Le-Van, N.; Nguyen-Hoang, K.; Nguyen-Minh, D.; Phung-Thi, T.; Le-Viet, A.; Tran-Ha Minh, D.; Nguyen-Tien, D.; et al. Classification of Vietnamese Cashew Nut (Anacardium occidentale L.) Products Using Statistical Algorithms Based on ICP/MS Data: A Study of Food Categorization. Journal of Analytical Methods in Chemistry 2023, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minh, T.N.; Van Thinh, P.; Anh, H.L.T.; Anh, L.V.; Khanh, N.H.; Van Nhan, L.; Trung, N.Q.; Dat, N.T. Chemometric classification of Vietnamese green tea (Camellia sinensis) varieties and origins using elemental profiling and FTIR spectroscopy. International Journal of Food Science and Technology 2024, 59, 9234–9244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truong Ngoc, M.; Nguyen, Q.T.; Pham, V.T.; Hoang, L.T.A.; Le, V.A.; Le, V.N.; Tran, H.M.D.; Nguyen, T.D. Assessing Vodka Authenticity and Origin in Vietnam’s Market: An Analytical Approach Using FTIR and ICP-MS with Multivariate Statistics. Journal of Analytical Methods in Chemistry 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flament, I. Coffee Flavor Chemistry; Wiley, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Bicchi, C.P.; Panero, O.M.; Pellegrino, G.M.; Vanni, A.C. Characterization of Roasted Coffee and Coffee Beverages by Solid Phase Microextraction−Gas Chromatography and Principal Component Analysis. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 1997, 45, 4680–4686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyman, D.J.; Benck, R.; Dell, S.; Merle, S.; Murray-Wijelath, J. FTIR-ATR Analysis of Brewed Coffee: Effect of Roasting Conditions. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 2003, 51, 3268–3272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos, J.R.; Sarraguça, M.C.; Rangel, A.O.S.S.; Lopes, J.A. Evaluation of green coffee beans quality using near infrared spectroscopy: A quantitative approach. Food Chemistry 2012, 135, 1828–1835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kemsley, E. Discrimination between Coffea arabica and Coffea canephora variant robusta beans using infrared spectroscopy. Food Chemistry 1995, 54, 321–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Jun, S.; Bittenbender, H.C.; Gautz, L.; Li, Q.X. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy for Kona Coffee Authentication. Journal of Food Science 2009, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mardia, K.V. Mahalanobis distances and angles. In Multivariate Analysis; Krishnaiah, P.R., Ed.; North-Holland: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1977; Volume 495, pp. 5–11. [Google Scholar]

- Jolliffe, I.T. Principal Components Analysis; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen-Quang, T.; Bui-Quang, M.; Truong-Ngoc, M. Rapid Identification of Geographical Origin of Commercial Soybean Marketed in Vietnam by ICP-MS. Journal of Analytical Methods in Chemistry 2021, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen Thi, K.-O.; Do, H.-G.; Duong, N.-T.; Nguyen, T.D.; Nguyen, Q.-T. Geographical Discrimination of Curcuma longa L. in Vietnam Based on LC-HRMS Metabolomics. Natural Product Communications 2021, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, V.N.; Nguyen, Q.T.; Nguyen, N.T.; Le, T.G.; Janda, T.; Szalai, G.; Rui, Y.-K. Simultaneous determination of plant endogenous hormones in green mustard by liquid chromatography—Tandem mass spectrometry. Chinese Journal of Analytical Chemistry 2021, 49, 111–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, Q.; Nguyen, T.; Le, V.; Nguyen, N.; Truong, N.; Hoang, M.; Pham, T.; Bui, Q. Towards a Standardized Approach for the Geographical Traceability of Plant Foods Using Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry (ICP-MS) and Principal Component Analysis (PCA). Foods 2023, 12, 1848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen-Quang, T.; Do-Hoang, G.; Truong-Ngoc, M. Multielement Analysis of Pakchoi (Brassica rapa L. ssp. chinensis) by ICP-MS and Their Classification according to Different Small Geographical Origins. Journal of Analytical Methods in Chemistry 2021, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mottaz, C.J. The Relative Importance of Intrinsic and Extrinsic Rewards as Determinants of Work Satisfaction. The Sociological Quarterly 1985, 26, 365–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bui, Q.M.; Nguyen, Q.T.; Nguyen, T.T.; Nguyen, H.M.; Phung, T.T.; Le, V.A.; Truong, N.M.; Mac, T.V.; Nguyen, T.D.; Hoang, L.T.A.; et al. Multivariate Statistical Analysis for the Classification of Sausages Based on Physicochemical Attributes, Using Attenuated Total Reflectance-Fourier Transform Infrared (ATR-FTIR) and Inductively Coupled Plasma-Mass Spectrometry (ICP-MS). Journal of Analytical Methods in Chemistry 2024, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbin, D.F.; Felicio ALde, S.M.; Sun, D.-W.; Nixdorf, S.L.; Hirooka, E.Y. Application of infrared spectral techniques on quality and compositional attributes of coffee: An overview. Food Research International 2014, 61, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Brand | Sample information | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arabica | Robusta | Moka | Culi | |

| Mai | A1 | - | M1 | Cu1 |

| Honey | A2 | R2 | M2 | Cu2 |

| Dương | A3 | R3 | M3 | - |

| Mê Trang | A4 | R4 | - | Cu4 |

| M Ja | A5 | R5 | - | - |

| Con soc | A6 | R6 | - | - |

| Hat A | A7 | R7 | - | - |

| Trung Nguyen | A8 | R8 | - | - |

| Huong Viet | A9 | R9 | - | Cu9 |

| Vinacafe | A10 | R10 | M10 | - |

| Phuc Long | - | R11 | M11 | - |

| TwitterBean | A12 | - | - | - |

| Nhan | A13 | - | - | - |

| Phuong Vi | - | R14 | - | - |

| Thu Ha | - | R15 | - | - |

| Nescafe | - | R16 | - | - |

| Highland | - | - | M17 | Cu17 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).