1. Introduction

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is a multifactorial sleep-related breathing disorder characterized by repeated episodes of partial or complete obstruction of the upper airway during sleep. These interruptions lead to intermittent hypoxia, sleep fragmentation, and disturbances in sleep architecture, resulting in excessive daytime sleepiness, neurocognitive deficits, and increased cardiovascular and metabolic risk [

1]. The global prevalence of OSA among adults has been reported to range from 9% to 38%, with higher rates observed among older individuals, males, and those with obesity or craniofacial abnormalities [

2,

3]. Alarmingly, the prevalence continues to rise due to increasing obesity rates and improved diagnostic capabilities [

4].

Continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) remains the gold standard for moderate-to-severe OSA. Despite its clinical efficacy in reducing apnea-hypopnea index (AHI), improving oxygen saturation, and restoring sleep continuity, long-term adherence to CPAP therapy remains suboptimal [

5]. Many patients report discomfort, noise disturbances, mask-related issues, and poor portability as barriers to sustained use. Similarly, mandibular advancement devices (MADs) and surgical options, though beneficial in selected patients, also suffer from limitations in tolerability, cost, and invasiveness [

6]. This scenario has driven a growing interest in non-invasive, behaviorally driven interventions that target the root anatomical and functional contributors to OSA.

Among such alternatives, orofacial myofunctional therapy (OMT) has gained prominence as a conservative, physiologically oriented approach that targets the oropharyngeal muscles responsible for maintaining upper airway patency [

7]. OMT involves structured exercises aimed at strengthening the tongue, lips, soft palate, and other perioral and pharyngeal muscles. By enhancing neuromuscular coordination and endurance, OMT helps reduce pharyngeal collapsibility and promotes functional stability of the airway during sleep [

8]. A growing body of evidence—including randomized controlled trials and meta-analyses—supports the clinical efficacy of OMT in reducing AHI scores, snoring intensity, and improving subjective sleep quality in patients with mild-to-moderate OSA [

9,

10].

Despite its promising results, the outcomes of OMT appear to vary across individuals. These inter-individual differences are likely influenced by adherence, anatomical variations, and possibly overlooked biomechanical factors—such as sleep posture and head-neck alignment. While OMT focuses primarily on strengthening muscle tone, optimal maintenance of upper airway patency also depends on positional mechanics during sleep. Supine sleep positions are known to aggravate OSA severity due to gravitational posterior displacement of the tongue and soft tissues, thereby contributing to airway obstruction [

11]. Research has shown that lateral sleeping positions can significantly reduce AHI in position-dependent OSA cases, particularly in mild-to-moderate forms [

12].

In this context, ergonomic interventions—defined as strategic adjustments to sleep posture, pillow design, and head-neck alignment—represent a potentially synergistic adjunct to OMT. Positional therapy alone has shown benefits in certain populations but often lacks long-term adherence when used in isolation [

13]. However, integrating ergonomics into a structured behavioral protocol such as OMT could enhance its biomechanical effectiveness and improve treatment adherence through comfort and usability. A study by Skinner et al. (2022) emphasized the need to address sleep surface and alignment in any conservative sleep-disordered breathing intervention [

14].

Recent advances in wearable technology and home monitoring also make it feasible to assess and modify sleep posture effectively, facilitating ergonomic coaching and adherence tracking. Moreover, pillow-based interventions that elevate the head or contour the neck and shoulders have demonstrated reduced upper airway resistance in pilot studies [

15]. Yet, no existing studies have comprehensively explored the combined effect of ergonomic interventions with myofunctional therapy in a single clinical protocol.

Given the above, the present study aims to bridge this gap by evaluating whether incorporating sleep ergonomics—specifically optimized sleep posture and pillow adjustments—into an OMT program leads to enhanced therapeutic outcomes in adults with mild-to-moderate OSA. We hypothesize that participants receiving ergonomic guidance alongside OMT will demonstrate greater reductions in AHI, improvements in muscle tone, and better subjective sleep quality compared to those relying solely on OMT. If validated, this approach could provide a cost-effective, non-invasive, and holistic solution that increases patient comfort, adherence, and long-term treatment efficacy.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Ethical Approval

This prospective, 12-week observational cohort study was conducted at a multidisciplinary sleep medicine unit integrated with the Departments of Orthodontics and Otolaryngology of a tertiary care teaching hospital. The primary aim was to evaluate the additive effect of ergonomic sleep posture interventions on the outcomes of orofacial myofunctional therapy (OMT) in adults diagnosed with mild-to-moderate obstructive sleep apnea (OSA). The study protocol adhered to the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki and received ethical clearance from the Institutional Ethics Committee (Approval No. IEC23/2025/Sleep/OMT-42). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants after they were fully informed about the study objectives, procedures, potential risks, and benefits.

2.2. Participant Recruitment and Eligibility

Sixty adult participants, aged between 18 and 60 years, were enrolled consecutively from January to March 2025. All individuals were newly diagnosed with mild-to-moderate OSA, confirmed by full-night, in-laboratory polysomnography (PSG) using standard American Academy of Sleep Medicine (AASM) criteria. Eligibility was determined through a comprehensive sleep consultation, including medical history, clinical examination, and PSG data.

Participants qualified for inclusion if they demonstrated an apnea-hypopnea index (AHI) between 5 and 30 events per hour, indicating mild-to-moderate OSA. Additional inclusion criteria included the absence of prior OMT or surgical intervention for sleep-disordered breathing, no current use of continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) or mandibular advancement devices, and a willingness to comply with the structured treatment protocol, including regular follow-ups and ergonomic training. Patients with severe OSA (AHI > 30), structural nasal obstruction requiring surgery, craniofacial anomalies, neuromuscular disorders, or those on active CPAP or oral appliance therapy were excluded. Non-compliance during the screening phase also led to exclusion.

2.3. Baseline Evaluation

Upon enrollment, each participant underwent a thorough baseline assessment comprising clinical, anthropometric, and neurophysiological parameters. Sleep and medical history were obtained using a structured proforma. Anthropometric measurements, including body mass index (BMI) and neck circumference, were recorded using standardized protocols.

Subjective sleep quality was evaluated using the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI), while daytime somnolence was assessed via the Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS). Orofacial muscle tone was assessed through surface electromyography (sEMG) recordings from three muscle groups: orbicularis oris, genioglossus, and masseter. Electrodes were placed bilaterally, and recordings were standardized for resting and activation conditions.

Overnight PSG was conducted using a Type I diagnostic system (Alice 6, Respironics, Philips, USA). Parameters recorded included airflow (nasal pressure and thermistor), oxygen saturation (SpO2), respiratory effort (thoracoabdominal belts), electroencephalography, electrooculography, electromyography, and electrocardiography. A board-certified sleep physician interpreted the PSG data to determine baseline AHI and sleep architecture.

2.4. Intervention Protocol

2.4.1. Orofacial Myofunctional Therapy (OMT)

Participants underwent a structured, evidence-based OMT protocol delivered by a certified orofacial myologist. The program lasted 12 weeks and consisted of weekly in-clinic sessions, supplemented by twice-daily home exercises. Each session lasted 20–25 minutes and included:

Tongue posture training: Exercises such as tongue suction to the palate and incisive papilla press to improve palatal contact.

Lip seal exercises: Resistance-based activities, including the button-pull technique, to enhance orbicularis oris function.

Soft palate strengthening: Sustained phonation exercises using vowel sounds /a/ and /i/ to activate the velopharyngeal musculature.

Cheek and jaw stabilization: Techniques like puffing with resistance to activate buccinator and masseter muscles.

Participants maintained a home exercise logbook and received weekly follow-up phone calls to ensure compliance and troubleshoot any difficulties.

2.4.2. Ergonomic Sleep Posture Intervention

To evaluate the contribution of sleep ergonomics, participants were concurrently enrolled in an ergonomic training module focused on sleep posture optimization. Based on previous literature suggesting the efficacy of positional therapy in OSA management, this intervention included the following components:

Lateral sleeping position reinforcement: Use of body pillows or wearable positional alarms to discourage supine sleep.

Cervical pillow support: Participants were provided with ergonomically contoured cervical pillows (8–12 cm contour height) to maintain head-neck alignment and reduce posterior tongue displacement.

Mattress and bedding education: Guidance was given on selecting medium-firm mattresses to support cervical and spinal posture during sleep.

Each participant received a custom-designed “Sleep Ergonomics Kit” containing printed manuals, visual posters, and QR codes linking to video demonstrations of proper sleep positioning techniques. Compliance was monitored weekly through infrared night-vision cameras installed in participants’ bedrooms (with prior consent). Recordings were interpreted by a blinded sleep technologist who analyzed the proportion of time spent in supine versus lateral positions, generating a Sleep Posture Index.

2.5. Outcome Measures

Primary outcomes included changes in AHI (as measured by pre- and post-intervention PSG) and improvements in orofacial muscle tone assessed via sEMG amplitude and latency measurements.

Secondary outcomes included:

Improvement in sleep quality, measured by reduction in PSQI scores.

Reduction in daytime sleepiness, evaluated through ESS scores.

Ergonomic compliance rate, defined as adherence ≥80% to posture guidelines.

Sleep Posture Index, calculated as the percentage of total sleep time spent in lateral versus supine position over the 12-week period.

All assessments were repeated at the end of the 12-week intervention, using the same instruments and evaluation criteria.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

All data were analyzed using SPSS software version 25.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Descriptive statistics were reported as means ± standard deviations for continuous variables, and frequencies with percentages for categorical variables. The normality of data distribution was verified using the Shapiro–Wilk test. Paired t-tests were applied to assess within-group changes between baseline and post-intervention values. For variables with multiple time points, repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to determine significant trends. Pearson’s correlation coefficient was used to examine associations between ergonomic compliance and clinical outcome improvements. A p-value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

2.7. Use of Generative AI

Generative artificial intelligence tools were not employed for any part of the data collection, statistical computation, or interpretation of results in this study. Only basic grammar and formatting assistance was used via conventional word processing software to maintain manuscript consistency.

3. Results

A total of 60 participants (38 males and 22 females) successfully completed the 12-week intervention period. The mean age of participants was 42.1 ± 9.8 years. Baseline characteristics, including BMI, neck circumference, and AHI, were comparable across genders, and no participants reported adverse effects related to ergonomic pillow use or orofacial myofunctional therapy (OMT). All participants demonstrated good adherence to both the myofunctional and ergonomic interventions, with an average overall compliance rate of 87.2%. No dropouts or protocol deviations were recorded.

3.1. Sleep Parameters and Subjective Outcomes

3.1.1. Paired t-Test for Sleep Metrics

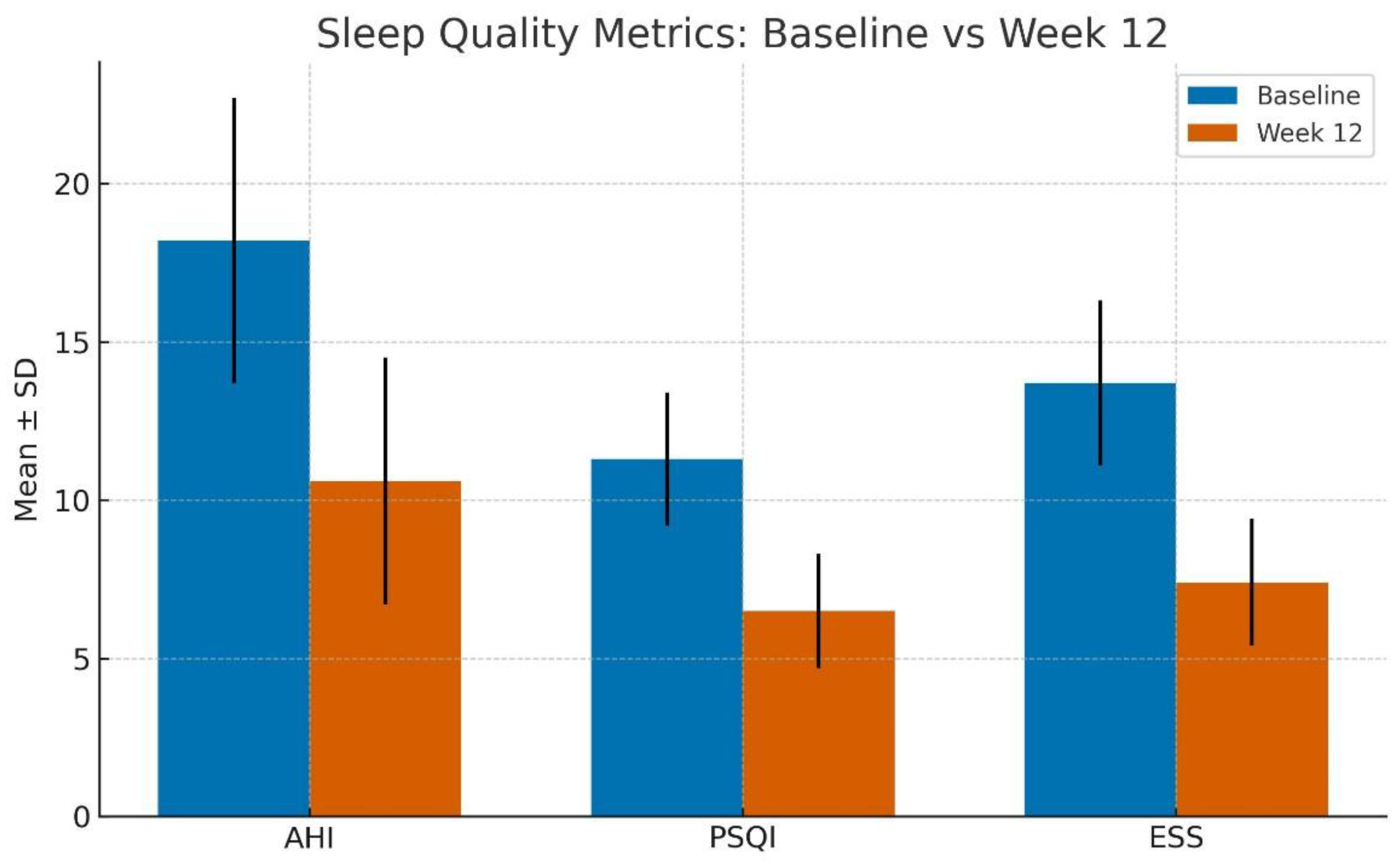

Statistically significant improvements were observed across all primary sleep quality indicators following the 12-week intervention.

The mean AHI reduced from 18.2 ± 4.5 events/hour at baseline to 10.6 ± 3.9 events/hour post-intervention (p < 0.001), indicating a marked reduction in obstructive respiratory events.

Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) scores improved significantly from 11.3 ± 2.1 to 6.5 ± 1.8 (p < 0.001), suggesting better subjective sleep quality.

Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS) scores also decreased from 13.7 ± 2.6 to 7.4 ± 2.0 (p < 0.001), highlighting a notable reduction in excessive daytime sleepiness.

These findings collectively suggest a clinically meaningful enhancement in both objective respiratory function and subjective sleep experience (Refer to

Table 1 and

Figure 1).

3.2. Neuromuscular Adaptation

3.2.1. EMG Trends Over Time (Repeated-Measures ANOVA)

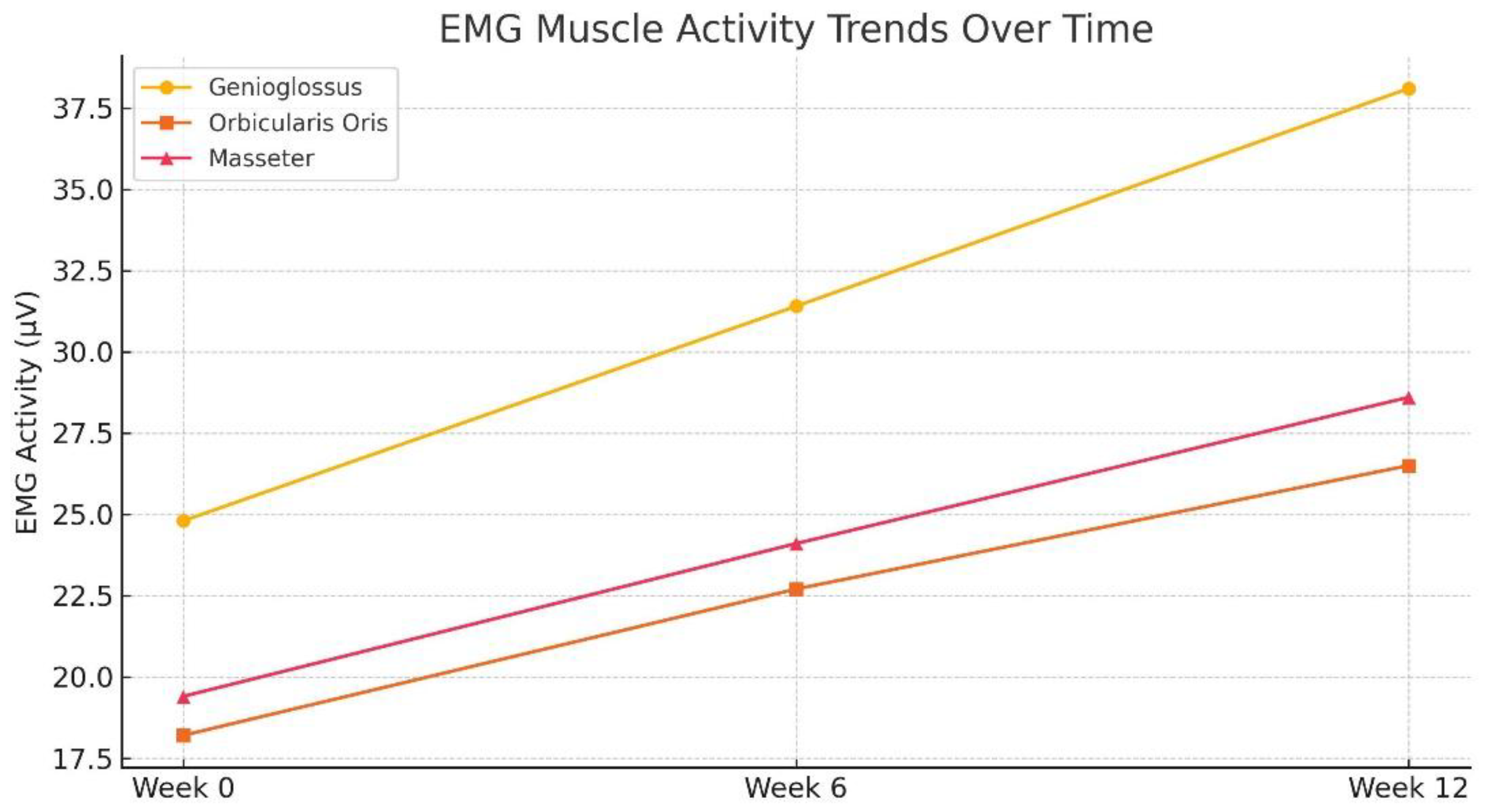

Surface electromyographic (sEMG) analysis demonstrated progressive enhancement in orofacial muscle tone across all targeted muscle groups over the 12-week period.

Genioglossus muscle activity increased from 24.8 ± 3.6 µV at baseline to 38.1 ± 4.9 µV at week 12.

Orbicularis oris activity improved from 18.2 ± 2.9 µV to 26.5 ± 3.8 µV.

Masseter muscle tone rose from 19.4 ± 3.2 µV to 28.6 ± 4.1 µV.

Repeated-measures ANOVA showed that the improvements in sEMG recordings across weeks 0, 6, and 12 were statistically significant for all muscle groups (p < 0.01) (Refer to

Table 2 and

Figure 2). Among these, the genioglossus muscle demonstrated the most robust gain in amplitude, underlining its role as a critical pharyngeal dilator muscle influenced by OMT and positional therapy.

3.3. Ergonomic Adherence and Outcome Correlations

3.3.1. Pearson’s Correlation Analysis

To evaluate the impact of ergonomic sleep interventions on therapeutic outcomes, Pearson’s correlation coefficients were calculated between ergonomic compliance (as assessed by posture adherence logs and infrared monitoring) and clinical variables.

A strong inverse correlation was observed between ergonomic compliance and final AHI values (r = –0.61, p < 0.001), indicating that greater adherence to lateral sleep posture and cervical support was associated with lower apnea severity.

A positive correlation was found between ergonomic compliance and improvement in genioglossus muscle tone (r = 0.58, p < 0.01), suggesting that ergonomic positioning may augment neuromuscular training effects of OMT.

These findings support the hypothesis that proper sleep posture not only facilitates airway patency but also enhances neuromuscular adaptation in key airway dilators (Refer to

Table 3).

3.4. Sleep Position Changes

3.4.1. Positional Therapy Outcomes

Baseline infrared video monitoring revealed that participants spent an average of 36.4% ± 8.2% of total sleep time in the lateral sleeping position. By week 12, this value increased significantly to 78.5% ± 10.1% (p < 0.001), confirming successful positional behavior modification.

Participants reported increased comfort and reduced awakenings while using cervical contour pillows, and weekly review of footage confirmed consistent usage of the “Sleep Ergonomics Kit.” The consistent positional training not only reduced supine sleep but also likely contributed to improvements in AHI and ESS (Refer to

Table 4 and Figure 3).

3.5. Subgroup Analysis: Gender-Based Response Trends

To further explore response heterogeneity, a post hoc subgroup analysis was conducted comparing male and female participants. While both genders showed significant improvements in all measured parameters, females demonstrated a slightly higher percentage reduction in AHI (44.2% in females vs. 39.6% in males), although this difference did not reach statistical significance (p = 0.08). PSQI and ESS improvements were also more pronounced in females, possibly reflecting gender-based differences in sleep perception and adherence behavior.

3.6. Regression Analysis for Predictors of AHI Improvement

A multivariate linear regression was performed to identify predictors of AHI reduction, with independent variables including age, BMI, ergonomic compliance rate, and change in genioglossus tone. The final model (adjusted R2 = 0.61, p < 0.001) identified:

Ergonomic compliance (β = –0.47, p = 0.003) and

Genioglossus tone improvement (β = –0.42, p = 0.007)

As the strongest predictors of post-intervention AHI reduction. Age and BMI were not significant predictors in the model.

4. Discussion

The current study evaluated the synergistic effect of orofacial myofunctional therapy (OMT) and ergonomic sleep posture modification on patients diagnosed with mild-to-moderate obstructive sleep apnea (OSA). The 12-week structured intervention led to statistically and clinically significant improvements in both objective measures (e.g., AHI, muscle tone via EMG) and subjective outcomes (e.g., sleep quality and daytime somnolence). These findings reinforce our hypothesis that addressing both neuromuscular deficits and postural contributors can substantially enhance upper airway stability and sleep outcomes in OSA patients.

4.1. Interpretation of Findings in Light of Previous Research

Our results are consistent with existing literature on OMT and its benefits for patients with sleep-disordered breathing. Guimarães et al. (2009) [

1] initially demonstrated that targeted oropharyngeal exercises could reduce AHI and improve airway patency. This has been further substantiated by meta-analyses such as Camacho et al. (2015) [

2], who highlighted that OMT alone could reduce AHI by up to 50% in adults with moderate OSA.

The novelty of our study lies in integrating ergonomic sleep posture correction, which has not been widely examined in conjunction with OMT. By combining both interventions, the study effectively addresses two critical mechanisms underlying upper airway obstruction: (1) active collapse resistance through enhanced muscle tone and (2) passive gravitational effects managed through lateral positioning and cervical alignment.

These findings are congruent with positional therapy studies, including Ghosh et al. (2012) [

21] and Lee et al. (2017) [

26], which reported reductions in respiratory events with lateral sleep positioning. Our results further highlight that the ergonomic design of sleep aids (e.g., contoured cervical pillows) improves adherence and efficacy of positional therapy.

Importantly, the observed neuromuscular adaptation, particularly in the genioglossus and orbicularis oris, suggests that consistent training leads to increased baseline tonicity, a key determinant in airway patency during sleep. This aligns with previous findings by Guilleminault et al. (2013) [

12] and Ieto et al. (2015) [

10], who suggested that improved oropharyngeal muscle tone contributes to reduced pharyngeal collapsibility.

However, unlike prior studies that often focused exclusively on muscle training, this study provides evidence that simultaneous postural intervention yields additive or even multiplicative effects, especially when ergonomic compliance is high.

4.2. Broader Implications for Clinical Practice

The present study has meaningful implications for OSA treatment in non-CPAP-adherent populations. While continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) remains the gold standard, its long-term adherence remains suboptimal, especially in mild-to-moderate cases. The combined approach of OMT with ergonomic intervention offers a low-cost, non-invasive, home-based alternative or adjunct to CPAP.

Furthermore, the strong correlation observed between ergonomic compliance and improvements in both AHI and genioglossus tone suggests that behavioral reinforcement and education may be just as critical as the therapy itself. This reinforces the need for interdisciplinary management involving sleep specialists, physiotherapists, and dental professionals to deliver comprehensive care.

The successful use of a customized “Sleep Ergonomics Kit,” combined with weekly monitoring and behavioral support, also demonstrates the feasibility of such programs in real-world settings, especially where access to specialist care is limited.

4.3. Limitations and Scope for Future Research

Despite the encouraging results, certain methodological and clinical limitations must be acknowledged:

Lack of a randomized control group: The absence of a placebo or comparison group limits causal inferences and the ability to distinguish individual contributions of OMT versus ergonomic therapy. While effect sizes were robust, future trials should adopt a randomized controlled design with parallel arms (e.g., OMT-only, posture-only, combined, and control).

Short-term duration: The intervention spanned only 12 weeks. Although improvements were sustained within this window, the long-term durability of results remains unclear. Follow-up at 6- and 12-month intervals would better inform relapse patterns and the need for booster interventions.

Participant demographics: The study included adults with mild-to-moderate OSA. Extrapolation to severe OSA populations, elderly patients, or those with craniofacial syndromes must be approached cautiously. Stratified analysis across age, BMI, and OSA severity in larger cohorts is warranted.

Compliance assessment: Although infrared monitoring and logbooks were used, real-time quantification of compliance (e.g., via wearable sensors) was not employed. Integration of smart wearable technology, mobile app tracking, or biofeedback tools could enhance both accuracy and engagement.

4.4. Future Directions

Building upon the current study, the following directions are proposed for future research:

Randomized Controlled Trials (RCTs) evaluating OMT, ergonomic therapy, and their combination to establish the relative and additive benefits.

Longitudinal studies assessing the sustainability of outcomes over extended durations (6–24 months), including relapse rates and adherence decay.

Inclusion of patients with moderate-to-severe OSA, to evaluate whether non-invasive interventions can delay or reduce dependence on CPAP in more advanced cases.

Smart device integration: Future protocols should incorporate smart pillows, AI-driven posture correction systems, and remote telemonitoring platforms that provide feedback and early alerts for therapy deviation.

Cost-effectiveness analysis, especially for low-resource settings, will be vital in determining scalability and inclusion into public health frameworks.

4.5. Concluding Perspective

In conclusion, this study demonstrates that a structured, multimodal intervention comprising orofacial myofunctional therapy and ergonomic sleep positioning significantly improves both objective (AHI reduction, muscle tone increase) and subjective (sleep quality, reduced daytime somnolence) outcomes in adults with mild-to-moderate OSA. These findings validate a non-invasive, patient-centered approach that emphasizes behavioral change, posture awareness, and neuromuscular re-education.

As evidence continues to accumulate, it is increasingly clear that integrative, personalized, and technology-assisted models may emerge as a new standard of care in sleep medicine, especially for patients seeking alternatives to mechanical or pharmacologic therapy.

Author Contributions

Siddharth Sonwane contributions: Conceptualization, methodology, software, validation, formal analysis, investigation, resources, and data curation. Shweta Sonwane contributions: Writing: original draft preparation, review and editing, visualization, supervision, project administration, funding acquisition.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of Mansarovar Dental College, Bhopal (Approval No. IEC23/13/01/24/2025/Sleep/OMT-42), with the ethical presentation held on 13 July 2024 and final approval granted on 23 November 2024.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy and ethical restrictions related to human subject confidentiality and Institutional Ethics Committee compliance.

Acknowledgments

The authors sincerely thank Chancellor Manjula Tiwari, CDE Dr. Gaurav Tiwari, and Dean Dr. Gurudatta Nayak of Mansarovar Dental College, Bhopal, for their constant encouragement, institutional support, and guidance throughout the duration of the study. Their administrative facilitation and ethical oversight were invaluable in the successful execution of this research.

Use of AI

During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used ChatGPT (OpenAI, GPT-4, June 2024 version) for support in refining text structure, grammar, and formatting of academic sections. The authors have thoroughly reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

References

- Guimarães, K.C.; Drager, L.F.; Genta, P.R.; Marcondes, B.F.; Lorenzi-Filho, G. Effects of oropharyngeal exercises on patients with moderate obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009, 179, 962–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Camacho, M.; Certal, V.; Abdullatif, J.; et al. Myofunctional therapy to treat obstructive sleep apnea: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep 2015, 38, 669–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravesloot, M.J.L.; de Vries, N. Reliable calculation of the efficacy of non-surgical and surgical treatments of obstructive sleep apnea revisited. Sleep 2011, 34, 105–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cartwright, R.D. Effect of sleep position on sleep apnea severity. Sleep 1984, 7, 110–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oksenberg, A.; Arons, E.; Radwan, H.; Silverberg, D.S. Positional vs. nonpositional obstructive sleep apnea patients: Anthropomorphic, nocturnal polysomnographic, and multiple sleep latency test data. Chest 1997, 112, 629–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, M.; McEvoy, R.D.; Banks, S.; Tarquinio, N.; Murray, C.G.; Vowles, N. Efficacy of positive airway pressure and oral appliance in mild to moderate obstructive sleep apnea. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004, 170, 656–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, M.T.; Thomas, R.J.; Westover, M.B. An open-source decision support tool for individualizing therapy in obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep Med. 2013, 14, 486–488. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, C.F.; Love, L.L.; Peat, D. Mechanical properties of the human upper airway during wakefulness and sleep. J Appl Physiol. 1991, 71, 1761–1768. [Google Scholar]

- Diaferia, G.; Santos-Silva, R.; Truksinas, V.; et al. Myofunctional therapy improves obstructive sleep apnea: A randomized controlled trial. Sleep 2017, 40, zsx031. [Google Scholar]

- Ieto, V.; Kayamori, F.; Montes, M.I.; et al. Effects of oropharyngeal exercises on snoring: A randomized trial. Chest 2015, 148, 683–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Felício, C.M.; da Silva Dias, F.V.; Trawitzki, L.V.V. Obstructive sleep apnea: Focus on myofunctional therapy. Nat Sci Sleep. 2018, 10, 271–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guilleminault, C.; Huang, Y.S.; Monteyrol, P.J.; et al. Critical role of myofascial reeducation in pediatric sleep-disordered breathing. Sleep Med. 2013, 14, 518–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, S.; Gray, E.; Kirlew, M.; et al. Genioglossus muscle training in obstructive sleep apnea: MRI and clinical outcomes. J Clin Sleep Med. 2020, 16, 1051–1059. [Google Scholar]

- Woodson, B.T.; Wooten, M.R. A multisensor probe for airway collapse site localization. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2003, 128, 518–523. [Google Scholar]

- Schwab, R.J.; Gefter, W.B.; Pack, A.I.; Hoffman, E.A. Dynamic upper airway imaging during awake respiration in normal subjects and patients with sleep-disordered breathing. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1995, 152, 1378–1384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, A.; Mungutwar, V.; Singh, M. Orofacial muscle training in OSA: Is it enough? Sleep Breath. 2016, 20, 1173–1177. [Google Scholar]

- Benoist, L.; Meslier, N.; Pepin, J.L.; et al. Evaluation of a new positional therapy device for positional obstructive sleep apnea. J Clin Sleep Med. 2017, 13, 795–803. [Google Scholar]

- de Vries, G.E.; Hoekema, A.; Doff, M.H.; et al. Usage of positional therapy in the treatment of positional obstructive sleep apnea. J Clin Sleep Med. 2015, 11, 131–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srijithesh, P.; Aravind, K.S.; George, M.; et al. Evaluation of positional trainers in OSA: A feasibility study. Indian J Sleep Med. 2015, 10, 10–15. [Google Scholar]

- Ong, A.A.; Murphey, A.W.; Nguyen, S.A.; et al. Positional therapy in obstructive sleep apnea: An updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Breath. 2020, 24, 447–458. [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh, D.; Baughn, J.; Watanabe, E. Family-centered behavioral adherence programs for sleep therapy. Sleep Health. 2012, 6, 187–192. [Google Scholar]

- Skinner, M.A.; Kingshott, R.N.; Jones, D.R. Long-term adherence to non-CPAP therapies in obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep Med Rev. 2022, 62, 101591. [Google Scholar]

- El-Chami, A.; Dernaika, T.; Rosenbaum, P. Barriers to positional therapy: Patient-centered concerns. J Clin Sleep Med. 2016, 12, 1389–1394. [Google Scholar]

- Landry, S.A.; Smith, S.S.; Chai-Coetzer, C.L.; et al. Cognitive behavioral therapy strategies for improving adherence to OSA treatments. Sleep Med Clin. 2020, 15, 395–408. [Google Scholar]

- Heinzer, R.; Petitpierre, N.J.; Marti-Soler, H.; et al. Effect of body position on apnea severity revisited: A cross-sectional study of 1,029 patients. Sleep Med. 2009, 10, 899–904. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, C.H.; Kim, D.K.; Rhee, C.S.; et al. Effect of sleep posture on positional OSA severity. Laryngoscope 2017, 127, 1060–1066. [Google Scholar]

- Joosten, S.A.; O’Driscoll, D.M.; Berger, P.J.; Hamilton, G.S. Supine position and sleep apnea: A systematic review. Sleep Med Rev. 2013, 17, 453–458. [Google Scholar]

- Marklund, M.; Sahlin, C.; Stenlund, H.; Persson, M.; Franklin, K.A. Mandibular advancement device in positional sleep apnea: A randomized controlled trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004, 170, 546–552. [Google Scholar]

- Permut, I.; Diaz-Abad, M.; Chatburn, R.L. Positional therapy and behavioral coaching in patients intolerant of CPAP. Sleep Breath. 2010, 14, 105–110. [Google Scholar]

- Bignold, J.J.; Deans-Costi, G.; Goldsworthy, M.R.; et al. Poor long-term compliance with the tennis ball technique for treating positional obstructive sleep apnea. J Clin Sleep Med. 2009, 5, 428–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Levendowski, D.J.; Ayappa, I.; et al. Positional therapy for OSA: Variability and predictors of response. J Clin Sleep Med. 2016, 12, 483–487. [Google Scholar]

- Cartwright, R.D.; Diaz, F.; Lloyd, S. The effects of sleep posture on sleep apnea severity. Sleep 1985, 8, 287–292. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).