Introduction

The theoretical model of Gestalt Psychotherapy (GP), born from Lewin’s (1943) field theory, Wertheimer’s (1938) Gestalt psychology, and Goldstein’s (1995) organismic conception, has evolved into a complex and multidimensional structure over the years. Although GP is based on shared conceptual pillars—first introduced in the foundational text by Perls, Hefferline, and Goodman (1951), which still represents a common denominator across different sensitivities and internal orientations within the model—it has never developed a comprehensive theory encompassing the numerous theoretical expansions that have emerged in recent decades. In Italy specifically, no descriptive, analytical, and systematic work has been conducted to outline the various authors’ perspectives, aiming to identify convergences and differences in their specific theoretical approaches. Nevertheless, from the active dialogue among Italian Gestaltists, it is clear that Gestalt thinking, while respecting its shared roots, has welcomed numerous stimuli from the complex landscape of modern psychotherapeutic approaches and is offering original and valuable responses to contemporary psychopathological challenges. Given the inherently open theoretical and epistemological foundations of GP, today’s Gestaltists have developed flexible therapeutic modalities that integrate elements from the evolving field of psychotherapy. These approaches are capable of addressing the pressures of modern societies and changes in pathoplastics.

It is evident that an organic description of the current structure of Gestalt thinking is needed to clarify its relationship with the latest developments in the human sciences and computational sciences—including recent contributions on the role of large language models in psychological care processes (Cioffi, 2025). Ultimately, constructing a solid theoretical formulation will support empirical research into the clinical effectiveness of GP in its contemporary articulations.

The research program launched in 2022 by the Italian Federation of Gestalt Schools and Institutes (FISIG) aims to redefine the Gestalt approach through the creation of a map of the key contents of the current landscape, based on a systematic semantic analysis of the theoretical contributions of various authors. Starting from this map, it will be possible to redesign the foundations of a modern Gestalt psychotherapy.

This study begins with a semantic analysis of contributions provided by several Gestalt psychotherapy institutes affiliated with FISIG, focusing on the concept of confluence.

The decision to begin the analysis of the current Italian Gestalt perspective from the concept of confluence was based on three main reasons: it is the first pathological mechanism described in the temporal sequence of the contact process between individual and environment; it is the pathogenic mechanism that produces the most severe clinical manifestations of contemporary psychopathology; and finally, it is the most complex and ambiguous concept proposed by the model’s founders—one that has generated ongoing international debate without reaching solid and universally shared foundations.

Before describing the semantic analysis of the contributions from Italian Gestalt schools, it is necessary to briefly outline the theoretical assumptions underlying the concept of confluence.

The Classic Model – The Contact Process

The theoretical model of GP, as presented in the foundational text, is based on a field perspective. It views the self as a temporal process and the phenomena of contact between organism and environment as the fundamental units of experience (Bandìn, 2018; Francesetti, 2024).

Perls writes in the foundational book of GT: “Experience occurs at the boundary between the organism and its environment.” We often refer to the Self entering into contact with the environment, “...but the simple and immediate reality is contact (between organism and environment) itself” (Perls et al., 1997, p. 47). “Contact—that process which allows assimilation and thus growth—consists of the gradual emergence of a figure against a background or context, determined by the organism/environment field. In perceptual processes, the figure (gestalt) can be a vivid and clear perception, an image, or an insight; in motor behavior, the gestalt can be an energetic and harmonious movement completed to its end... In both these domains, the organism’s needs and the environment’s possibilities are incorporated and unified in the figure” (p. 41 - Perls, F. et al. 1997).

“When a new configuration (gestalt) gains consistency, previously acquired contact-generating habits of the organism are automatically destroyed in function of the new contact” (p. 43 - Perls, F. et al. 1997). The emerging gestalts are stored in the organism’s memory and form the Id of pre-verbal experience (Perls et al., 1997).

The self is the totality of contact processes that occur through the activity of sensory organs (sensory and perceptual networks of the nervous system), where the encounter between organism and environment takes place.

The temporal sequence in which these sensory and perceptual contact phenomena occur—giving rise to experience—is divided into stages and termed the “Contact Process” (Lobb, 2001).

It partly corresponds to the gratification cycle of needs—also called the organismic self-regulation cycle—but expands it by explaining conscious experience as a unified perception (Gestalt) of the self in interaction with the world. This perception arises from an undifferentiated organism-environment field at the end of the contact process, as a clear and distinct experiential configuration of a completed gestalt (De Lucca, 2012; Di Sarno et al., 2018). The emergent gestalt remains in the neural memory of perceptual-motor processes and constitutes the pre-verbal subjective experience of the self in the world with which the person engages in subsequent encounters with reality (Perls et al., 1997; Fuchs, 2021).

The Concept of Confluence

Confluence is one of the most debated mechanisms of contact interruption, leading to the failure of the cycle of satisfaction of organismic needs (Yontef, 1993; Clarkson, 1989; Mackewn, 1997). Didactically, confluence is described as a pathological interruption mechanism in which the self remains absorbed in the pre-verbal experience of being-in-the-world. This psychic state prevents the recognition of homeostatic perturbations in the organism-environment encounter, interrupts the contact cycle, and renders the creation of new gestalts impossible (Stevens, 1971; Philippson, 2001; Robine, 2001).

However, from the very definition in the foundational text, confluence assumes a complexity that is difficult to reduce: “Confluence is the condition in which a lack of contact occurs (an absence of self-boundary lines)... We have already seen that usually, after contact, assimilation occurs with a diminished self and all habits and learning are confluent... Confluence is unhealthy only when maintained as a means to prevent contact. Once contact has been achieved and lived, confluence takes on an entirely different meaning” (p. 256 - Perls, F. et al., 1997).

In this way, the authors explain that confluence is physiological when it occurs at the end of the contact process and pathological when it arises at the beginning, as it prevents the organism-environment field from moving beyond the Id phase and blocks the initial stage of the organismic process.

Confluence thus appears to be the contact interruption mechanism underlying severe psychopathological manifestations. However, the founders’ description is far from rigorous—rather, it is markedly ambiguous—leaving room for contradictory interpretations.

To illustrate, we cite two classical interpretations of confluence which, while clarifying the concept’s boundaries, fail to resolve its contradictions:

Ginger (2004) defines confluence as: a state of fusion due to the absence of boundaries; a form of contact in which the self cannot be identified. By its very nature, confluence is followed by withdrawal, which allows the subject to regain their boundary-contact and thereby rediscover their identity and singularity. Confluence becomes pathological when withdrawal does not occur.

Polster (1986) states: “Confluence is a phantom pursued by those who wish to reduce difference to moderate the disruptive experience of the new and the other. [...] One of the problems with confluence is, of course, that it is a fragile foundation for relationships.”

Study Objectives

The complexity of the definition of confluence may be viewed as a strength of the Gestalt approach, as it supports the adaptation of the concept to the therapist’s style and the patient’s individuality. However, this comes at the expense of a clear identification of this fundamental contact interruption mechanism. Consequently, the absence of a shared definition could pose a problem for the scientific rigor of the therapeutic method.

This study aims to chart a precise map of the concept of confluence as presented by Italian Gestaltists, with the goal of identifying both shared areas and differences among models. This would allow, on one hand, for a clearer conceptual definition, and on the other, for the development of studies aimed at empirically validating Gestalt Therapy’s effectiveness in treating psychotic disorders and severe personality disturbances.

Although we view the establishment of a rigid Gestalt psychotherapy orthodoxy as counterproductive—since its strength lies in flexibility, creativity, and adaptability to the “here and now” of times, contexts, and specific situations—we acknowledge the undeniable necessity of achieving broader and more robust consensus on the definition of key mechanisms, such as confluence, without sacrificing nuances of meaning.

Through this study, we aim to promote greater homogeneity and shared understanding of the foundational principles of GP, thereby laying a solid and shared foundation for future process and efficacy research in Gestalt Psychotherapy.

Materials and Methods

The directors and trainers of several Italian Gestalt psychotherapy schools—members of the Italian Federation of Gestalt Schools and Institutes (FISIG)—provided brief written contributions on their view of confluence. These contributions were subjected to semantic analysis using ChatGPT (Generative Pre-trained Transformer), a natural language processing AI tool based on advanced machine learning algorithms (Roumeliotis & Tselikas, 2023; Cioffi, 2022; Cioffi, 2023).

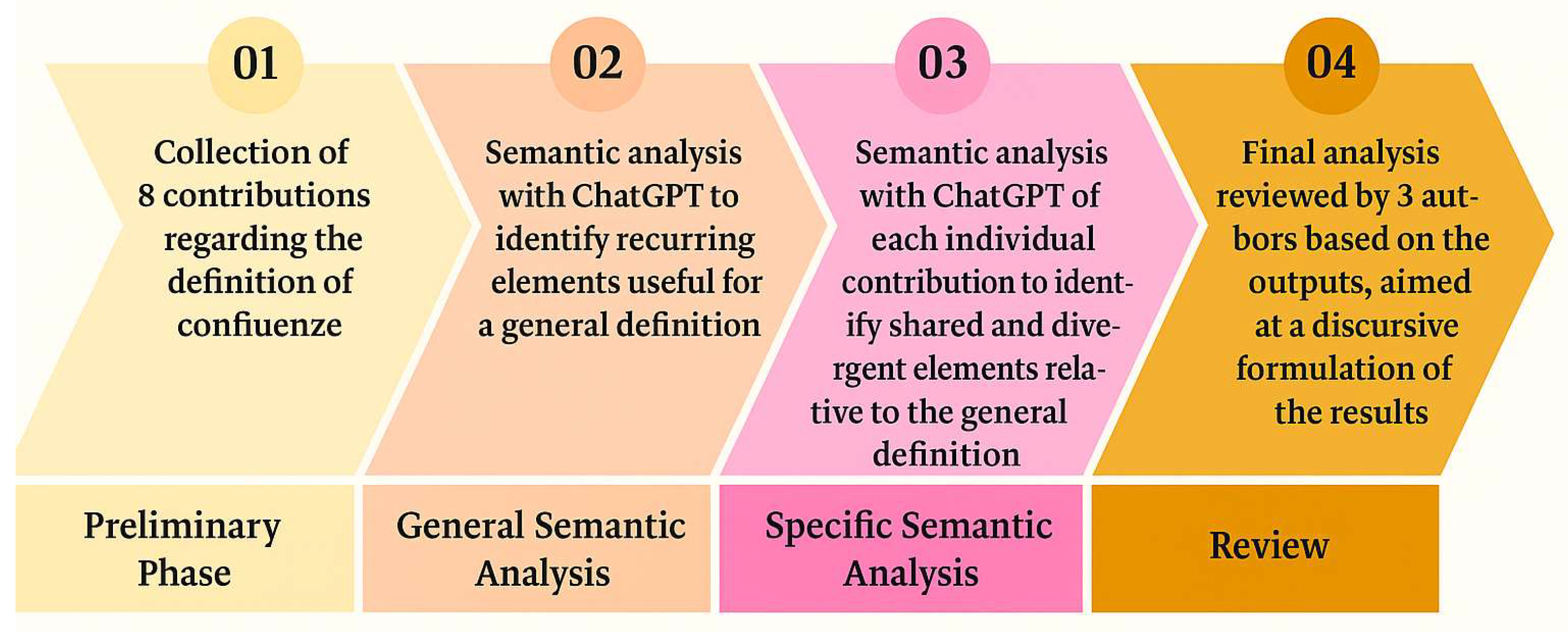

In Phase 01 (preliminary phase), we collected eight contributions from Italian Gestalt schools.

In Phase 02 (general semantic analysis), all contributions were analyzed to identify recurring elements and formulate a shared conceptual map of confluence.

In Phase 03 (specific semantic analysis), individual contributions were compared—highlighting similarities and differences—against the previously developed map.

In Phase 04 (final review), a systematic synthesis was carried out to verify concept recurrence across contributions and distill the essence of the concept of confluence (

Figure 1).

The Contributions Analyzed

Below we briefly outline the contributions received on the definition of confluence, which were subjected to the procedures described.

IGF: Confluence is that process, also defined as a contact avoidance mechanism, which causes confusion between the personal boundaries of the individual and those of the environment: a process that prevents the individual from returning to themselves. Overall, confluence thus refers to a situation where the boundaries between a person and their interlocutor are not clearly defined, where potential differences in sensations, emotions, and evaluations between the two are not allowed, to the point that individuality is sacrificed in order to preserve the fusion typical of confluence.

IGRO: Confluence can be defined as a mechanism of contact interruption that places the individual in a condition to respond to the environment based on the needs of the environment itself. Within an I-Thou relationship, the self of the confluent person manifests little or not at all, out of fear of differentiation from the other; however, it is important to note that confluence also has a positive aspect, when it allows the person to engage in what is known as “teamwork,” thereby mediating the empathic ability to be with and share with the other. From the perspective of psychological development, it can be recognized in the movements of the newborn, especially in that developmental phase where no differentiation between the self and the external environment seems to exist. In this case, confluence takes on a positive connotation.

School of Expressive Gestalt: Confluence can be defined as an “undifferentiation between figure and ground,” which, in the absence of a contact figure, remains in a state outside of awareness. This is very close to Piaget’s theory according to which, in the child’s initial world, no distinction is possible between the self and the external world. There is a sort of fusion between the two parts, and the self has no awareness of itself; thus, the transition from “initial chaos” to an “ordered cosmos” requires a laborious process.

ASPIC: Confluence is the attempt to cling to an inner sense of safety, without however defining and individuating oneself, in order to avoid confrontation. Its expression is also mediated by bodily characteristics essentially related to desensitization and muscular paralysis, differences in skin density and color, as well as minimal sensitivity in various body parts. Bodily manifestations can include, for example, a clenched jaw; a bear hug (clamp-like grip); a very low voice; agitation and continuous movement (to avoid perceiving external demands); spontaneity often perceived as false (or random spontaneity). Work can thus be done on points of contraction or desensitization, or the contraction itself can be exaggerated (especially when anxiety is present) (Pizzimenti, Rivetti, 2020, pp. 81–82).

IGF2: It could be said that confluence is a condition of temporary loss of psychological boundaries. Certain experiences—for example, orgasm, referred to by the French as “la petite mort”—are sometimes described as totalizing, fusion-like, as an explosive loss of boundaries with the other, an opening toward the indistinct, the undifferentiated. It is a condition in which it is difficult to recount the conscious experience, but it can be recognized through a sense of confusion, a lack of clarity about what one feels and desires.

SGT: The term confluence refers to the confluence of two rivers: immediately after the point of confluence, one sees a single river, but if the water were analyzed, one would see that the two waters are not yet united and their differences persist. This characteristic of the appearance of union serves different functions at various moments of encounter between the individual and their environment. Confluence is thus a particular and temporally limited feature of the contact process, defining a phenomenon marked by vagueness, fogginess, non-disturbing confusion, absence of clear boundaries in our perceptions, and absence of judgment, which precedes the emergence of new clarity in encountering novelty.

IGP: Confluence is defined as a mechanism of contact interruption characterized by the loss of differentiation from the other, which can be either the environment or the interlocutor. What happens in confluence is that, just as it becomes impossible to differentiate the waters of two rivers once joined, likewise the person no longer perceives the difference between self and other: this creates confusion, difficulty in being present to oneself, in understanding what is truly important for oneself, and in making individual decisions.

IGAT: Confluence is defined as a form of contact interruption that manifests in the early stages of existence, when the movement leading to the sensory exploration of the external world is not fully activated. More commonly, confluence can be likened to symbiosis—a phenomenon where boundaries are not perceived and which allows for the survival of the species and the individual. In confluence, one seeks bonds that do not provide nourishment or facilitate personal development, but instead offer reassurance. In the confluent person, passivity dominates, and the transition to what Gestalt seeks—responsible action—is absent. In the tradition of the Enneagram, this mechanism is typical of the Sloth character: an emotional state that distracts from deep self-knowledge and encourages over-adaptation, leading to dependency on people and things, to the point of immobility and superficiality. Its way out is a virtue called action. Confluence, as already mentioned, has its roots in the early stages of existence and prevents smooth progression toward pre-contact and full contact. Naturally, in adult men and women, these needs will never be met unless the ties to the past are broken and one takes direct responsibility for oneself without seeking support.

Results

The definitions of the concept of “confluence” provided by eight directors of Gestalt psychotherapy schools present a number of recurring themes, which can serve as a basis for a unified and more concise definition.

Table 1 outlines the shared content.

From These Shared Elements, the Following Definition of ^#:

Confluence is a mechanism that entails a loss or weakening of the boundaries between the self and the environment. Physiologically present during the early developmental stages of the individual, it may display both positive and negative aspects in the emergence of experience and self. Confluence often arises as a response to the fear of differentiation and, if it becomes a persistent mechanism, can limit the natural process of adaptation.

Based on the above, it has been possible to formulate a concise description of the phenomenon of confluence, highlighting the elements that proved most central and widely agreed upon:Confluence is a contextual mechanism within the process of experience (or contact). Depending on the intensity with which it manifests and the phase of the process in which it occurs, it may take on either functional or pathological connotations.

The theme of fusion, repeatedly mentioned across the various contributions, can be understood as either an adaptive or maladaptive experience, depending on its function, the temporal-developmental context, and its capacity to exhaust itself while enabling the progression of the contact cycle.

Confluence can therefore be contextualized within specific developmental phases, marked by processes of personal growth and development. It may be temporally limited to specific phases within the experiential and developmental cycle, and circumscribed to certain contexts and specific needs.

In its pathological expressions, it is included among the so-called “contact interruption mechanisms.” What distinguishes it from other interruption mechanisms is the experience of boundary weakening or loss between the self and the other, or between the self and the environment.Finally, it can be defined in either pathological or functional terms, depending on its position within the functional–dysfunctional continuum, along with its related bodily and emotional manifestations.

Table 2 outlines the conceptual contents characterizing each individual contribution.

IGF focuses on the loss of individual differentiation, understood both as an affective experience and as a cognitive difficulty in identifying one’s own ideas and emotions.

IGRO highlights the fear of self-disclosure as a mechanism that gives rise to confluence, while also emphasizing two positive dimensions of confluence: the sense of belonging and the lack of identity in the newborn, with the significant potential of this developmental state.

IGE points to the failure to differentiate figure from ground and the reduced awareness of experience in the confluence state.

ASPIC underscores how confluence reflects an avoidance of contact with the world from an adult position, coupled with a search for a sense of fusion-based security typical of early childhood.

IGF2 identifies confluence within peak experiences, during which it is difficult to organize a structured narrative of the experience.

IGT emphasizes that the experience of confluence is transitory, accompanied by a pleasant mental state of confusion and functioning as a prelude to creative adjustment and personal growth.

IGP underlines how the state of confluence hinders personal decision-making.

Finally, IGAT clarifies the function of confluence during the developmental phases of the individual, its therapeutic value as a starting point for re-establishing contact with reality, and its nature as a stable personality trait also described in certain personality theories such as the Enneagram.

Table 3 illustrates how the concepts of blurred boundaries, undifferentiation of perceptual gestalts, avoidance of contact with the world, and the developmental function of confluence are shared among various authors. Emotional dimensions, bodily manifestations of confluence, and the transitory nature of the phenomenon are described only by a few authors.

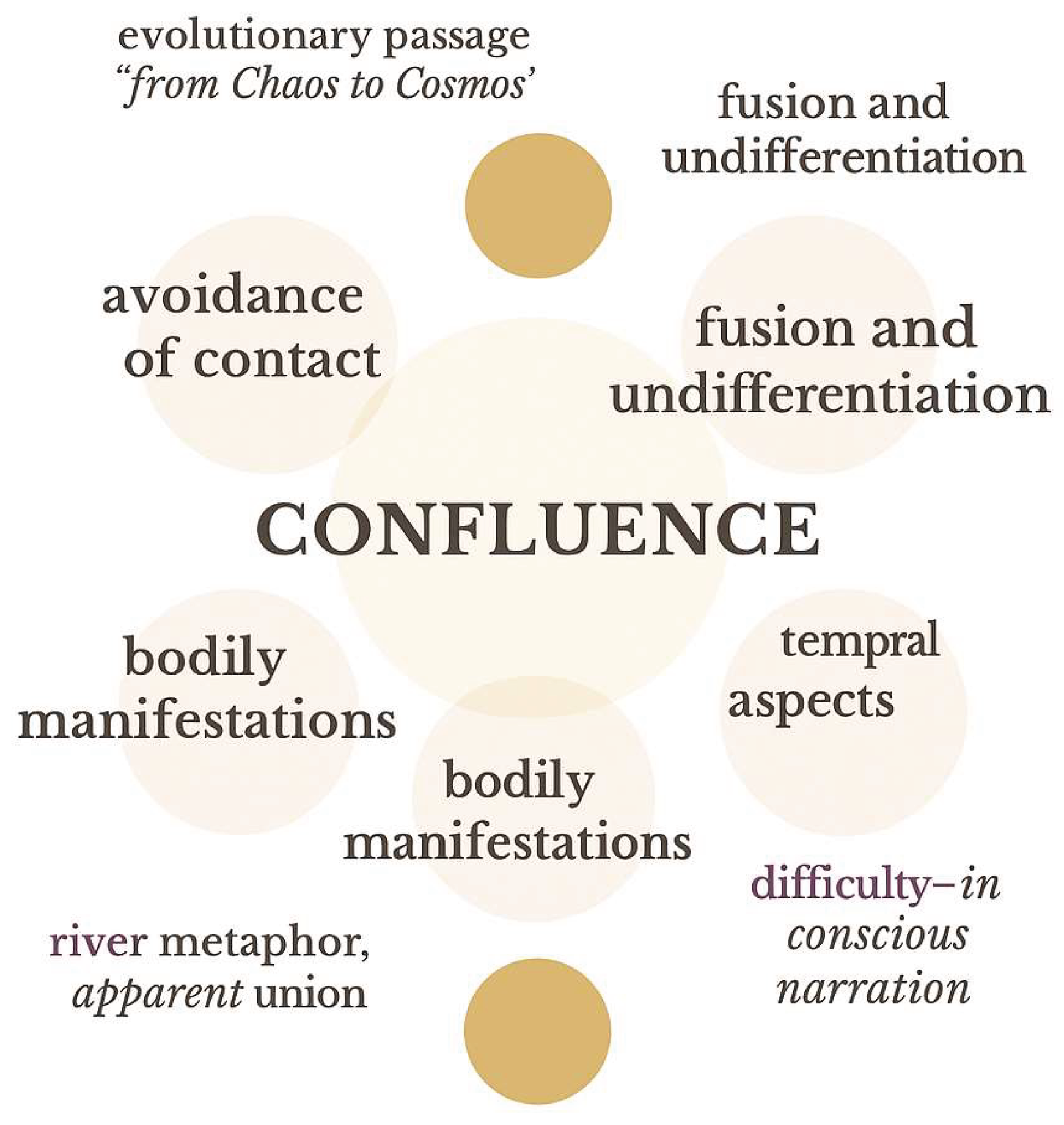

Figure 2 illustrates the frequency with which the meanings attributed to the phenomenon of confluence appear in the semantic analysis. The most frequent is the theme of blurred boundaries, present in 7 out of 8 contributions, which emphasizes how the separation between self and world is indistinct and diffuse.

Next in frequency is the lack of differentiation, appearing in 6 out of 8 contributions, understood as a difficulty in developing a clear definition of personal identity, where the persistence of an undifferentiated field allows for the preservation of a primordial inner sense of safety.Lastly, contact avoidance is evident, highlighted in 5 out of 8 contributions, which places confluence within a perspective of stagnation in which contact with the other and with the world is no longer possible, resulting in a loss of spontaneity and genuineness in intersubjective dynamics.Following in frequency and significance are additional concepts described by the eight contributors: the temporal aspects of confluence, the necessity of confluence in developmental phases, bodily manifestations, and confluence as a protection from the fear of differentiation. Related concepts that appear particularly evocative include the river metaphor of confluence, difficulty in self-narration, loss of awareness, and the transition from chaos to cosmos.

Discussion

As already proposed by Perls (1969) in “Ego, Hunger and Aggression,” the etymology of the concept “confluence” refers to the idea of “flowing together” (con-fluere) (Philippson, 2001). This semantic dimension is clearly reflected in the shared themes found across the eight analyzed contributions.The semantic analysis revealed a shared core in the phenomenological and psychopathological description of confluence. This core consists of three main dimensions: blurred boundaries, lack of differentiation, and contact avoidance. The first dimension describes the functional aspect of the confluence phenomenon; the second expresses its psychopathological significance when it becomes persistent and the person remains stuck in that experiential state; the third highlights the teleological quality of confluence, interpreted not as the “primum movens” but as a central point within a circular causality framework.

The theme of blurred boundaries shows that confluence is a state in which the experience of separation between person and environment is indistinct. It involves a state of uncertainty that alters the perception of the distinction between self and world. The representation of personal identity as a distinct entity within the field is attenuated, generating a sense of belonging to the field that can, in some contexts, be fulfilling or even ecstatic. This is, for instance, the deeply gratifying condition experienced in the moments following orgasm, which implies a temporary loss of alterity. The person may fully identify with a role or status as a basis for their sense of self, which may serve a “protective” function for some, avoiding the anxiety of choice by clinging to familiar and secure roles (Perls, 1980).Blurred boundaries mediate a temporary phase in individual growth. A certain degree of sensory undifferentiation is necessary to feel rooted in one’s family; minimal emotional undifferentiation enables the formation of affective bonds; and minimal value-based undifferentiation fosters identification with one’s social group (e.g., belonging to a scientific community is grounded in the sense that all members believe in the same epistemology) (Diamare et al., 2024). Thus, blurred boundaries can be a natural expression of human experience—as a necessary stage in early attachment or moments of profound group belonging. However, if this condition persists longer than necessary, it can become an obstacle to authenticity and self-determination.

The concept of lack of differentiation clarifies that confluence is characterized by the absence of distinction between one’s own sensations, emotions, and evaluations and those of the interlocutor. When this lack of differentiation endures, elements of the field remain blurred, as in the initial stages of the experiential process. This contributes to the creation of an experiential continuum where self and other share the same psychological space. Initially, this may feel reassuring and useful for preserving existential or ontological security. Over time, however, it may become disorienting and pathological. In persistent confluence (being stuck in confluence), perceptions become less defined, potentially resulting in the total absence of critical judgment. In such a state, individuals may be unable to recognize or express their own needs, desires, or feelings as distinct from those of others. When the loss of alterity persists, the result is a relinquishment of will, decision-making, and autonomy—key factors for a functioning organism, as highlighted in studies on anger and anxiety disorders from a Gestalt perspective (Lommatzsch et al., 2024).

Persistent confluence may manifest in ways ranging from automatic, uncritical acceptance of conventions to chronic denial of differentiation, from pathological abandonment anxiety to psychotic loss of agency. It expresses itself across a wide spectrum of manifestations, which become increasingly incompatible with autonomous existence. In this state, individuals live in a liminal space where the usual perception of self as a separate, autonomous entity is weakened or temporarily lost, as seen in clinical forms like panic disorder analyzed through the Gestalt-relational model (Orlando, 2020).

Thus, lack of differentiation may be associated with a “comfortable undifferentiation,” a double-edged sword that facilitates social adaptation but also impedes individuation and personal growth. It can render the perception of one’s identity and needs elusive. In such cases, individuals avoid defining or clearly identifying their self, opting for a nebulous refuge that, on one hand, provides a sense of safety and, on the other, hinders personal fulfillment.

The third element presents confluence as a mechanism of contact avoidance that disrupts the experiential process. Confluence thus acts as an active psychological mechanism that prevents sensations from integrating into perception. While maintaining sensory and physical contact with the world, the person loses the ability for evolutionary interaction within the organism-environment field and withdraws into an invisible shell, evading authentic contact. Contact avoidance functions as an active resistance to experience to prevent associated vulnerability.

The subject appears to seek an optimal distance from internal and external stimuli to avoid disturbances in homeostatic balance. The refusal to engage with situations and people becomes a central aspect of confluence. The individual remains in a semi-isolated state, where external exchanges are filtered through this protective mechanism.

This mechanism also generates avoidance of contact with parts of the self—desires, needs, emotions—which remain unexpressed or unheard. It fractures the integrity of the field and stands between the individual and their ability to live a life rich in deep personal experiences and authentic relationships.Other, less frequently shared but equally defining qualities are also attributed to confluence. These too carry functional, pathological, and causal meanings.

As a functional phenomenon, confluence is described as characteristic of the early stages of individual development. The newborn’s sense of self is initially so fused with the mother’s that there is no perception of where one ends and the other begins. The concept of confluence aptly applies to this fusion experience, which is both physical and psychological. As found in Piaget’s theory (cited in one contribution), confluence at this stage is indispensable for the infant’s survival, allowing deep attunement with the mother to ensure fulfillment of needs such as nourishment, protection, and comfort.

Equally vital is that, at a certain point, the child emerges from this confluence, develops an autonomous self, and learns to interact with others and the world while recognizing and constructing personal boundaries. If this transition does not occur, or if a person regresses to this state later in life, psychological difficulties may arise—ranging from dependency to the inability to recognize and meet one’s own needs.

The fear of differentiation, which leads to undifferentiation, is described as a central part of the circular process underlying confluence. It is a fear that profoundly affects self-expression and the ability to recognize and communicate one’s internal experience. In a confluence state, the ground for individual differences vanishes, and distinctions become so blurred that individuality is lost in a mosaic of experiences. This often reflects fear of rejection or of being different and disconnected from others. The confluent individual may adopt chameleon-like behaviors, adapting to others and risking becoming an echo of others’ expectations, thus losing their own authenticity. This lack of space for individuality not only constrains authentic self-expression but may also lead to a form of inner alienation rooted in the conflict between the desire to belong and the need for authenticity.

As a pathological phenomenon, confluence is also characterized by bodily manifestations that reveal altered personal boundaries. Examples include desensitization and “functional muscular paralysis”—physical phenomena in which the body becomes an ally in avoiding contact. Desensitization refers to a diminished emotional and bodily sensitivity that impairs the ability to fully perceive and respond to the field. It can manifest as emotional numbness or reduced physical reactivity. Functional muscular paralysis may be understood as rigidity or freezing of action capabilities. In a confluent state, the body becomes static, as if movement capacities are temporarily suspended until the threat of differentiation has passed.

Changes in skin tone and texture may also serve as physical indicators of confluence. These somatic responses reflect intense internal reactions to an environment perceived as overwhelming or invasive—a defensive strategy that creates physical distance from reality.

At both the macro level of personal development and the micro-level of the excitement/assimilation/growth cycle in the here-and-now of contact, confluence appears as a fundamental phenomenon for experience assimilation. It can serve functions of gratification, field identification, developmental rooting, emotional and social belonging, and protection from anxiety. From the analysis of the contributions, it is clear that confluence must be a transitory phenomenon occurring at the beginning and end of the contact process to remain healthy. When confluence persists beyond its useful time, it results in a blockage of the evolutionary/assimilative process with pathological expressions ranging from mild difficulty in making autonomous decisions to psychotic fusion with the other.

These findings offer evidence that the current articulation of this central concept in GP aligns with epistemologies at the foundation of contemporary sciences.

All authors perceive confluence within an enactivist perspective, referring to the mind as an embodied process that exists in the act of experience and in the here and now of action. This vision of the human being—where the external world is not a separate domain to be represented internally but a relational domain created by the subject’s perceptual-motor functions—is aligned with the most advanced models in biological sciences such as complex systems theory, network theory, and ecological biology (Maldonato et al., 2018; Fuchs, 2021; Mosca et al., 2018; Sperandeo et al., 2019).

Notably, neurobiological evidence supports the description of confluence as both the initial and final stages of perceptual processes. For example, in the early phases of visual perception, the experience of a confluent field is diffuse and organized at the thalamus and tectum level—where sensory and perceptual neural pathways arrive. These inputs lack the structured organization of the occipital cortex and underlie the experience of blurred boundaries. In the final stage of visual processing, conscious experience appears to involve activation of the Default Mode Network (DMN), which mediates experiential participation via complex and widespread perceptual-motor neural networks. These two stages may represent the neural correlates of healthy confluence (Pessoa, 2023).

Additionally, failure to deactivate the insula at the end of the DMN phase may result in difficulty distinguishing what belongs to the self from what belongs to the environment (Ebisch et al., 2013)—a potential neurobiological correlate of dysfunctional persistent confluence.

This strong correspondence between confluence theory and perception neuroscience highlights how GP is rooted in Gestalt psychology and underscores its place among non-dualistic, non-reductionist models of the human being (Di Leva, 2023; Cozzolino & Celia, 2020; Scarito, 2021).

Conclusions, Limitations, and Future Developments

This study has shown that the concept of confluence, while presenting varied facets and interpretations within the Italian Gestalt community, is grounded in a core theoretical structure describing its functional and dysfunctional expressions and the circular mechanisms that give rise to its pathological manifestations. Our semantic analysis enabled the construction of a clear definition of confluence, integrating both converging and diverging views for a more nuanced and comprehensive understanding of the phenomenon.

However, it must be acknowledged that this definition needs further development in descriptive, evolutionary, and causal terms within the psychological, biological, anthropological, and social domains (Maciariello et al., 2023). The recurring and divergent themes identified in this study offer a solid foundation for future scientific inquiries that aim to root the theory within a scientific framework. This empirical orientation strengthens the theoretical landscape of GP and provides valuable guidance for therapeutic practice, supporting evidence of its clinical effectiveness—as demonstrated in recent studies on perceived psychological well-being during Gestalt treatments (Roti et al., 2023) and integrated blended approaches (Iannazzo et al., 2023; Rosa et al., 2024).

Despite promising results, this study is limited by the relatively small number of analyzed contributions. However, those contributions are highly representative of the perspectives held by various Italian Gestalt schools. The semantic analysis derived from them effectively revealed the core aspects of the confluence concept. It achieved the declared objective: to build a sufficiently shared and precise definition of confluence that could become the object of scientific investigation without compromising its richness or plurality.

Nevertheless, exploring a larger number of interpretations could provide a more nuanced and articulated view of confluence, potentially yielding a richer conceptual outcome and a more robust, widely accepted core of meaning. Additionally, extending the analysis to include international contributions could further enrich the debate, integrating diverse perspectives and prompting broader reflection on the concept. Future developments could involve empirical studies aimed at exploring both functional and clinical manifestations of confluence, as well as its relationship to specific psychopathologies. It is also hoped that interdisciplinary research methodologies—combining qualitative and quantitative approaches—will be employed to deepen understanding of confluence and its therapeutic implications.

References

- Bandìn C. V.(2018). “come il fiume interminabile che passa e resta”. la teoria del sé nella psicoterapia della Gestalt. Sé: Una polifonia di psicoterapeuti della Gestalt contemporanei. Robine, J. M., FrancoAngeli.

- Bandín, C. V. (2012). Personality: Co-creating a dynamic symphony. In Gestalt Therapy (pp. 49-58). Routledge.

- Cioffi, V. (2025). Editorial: Mental Health 4.0: the contribution of LLM models in mental health care processes. Phenomena Journal - International Journal of Psychopathology, Neuroscience and Psychotherapy, 7(1),38–40. [CrossRef]

- Cioffi, V., Mosca, L. L., Moretto, E., Ragozzino, O., Stanzione, R., Bottone, M., ... & Sperandeo, R. (2022). Computational Methods in Psychotherapy: A Scoping Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(19), 12358. [CrossRef]

- Cioffi, V., Mosca, L. L., Moretto, E., Stanzione, R., Ragozzino, O., Salonia, G., ... & Sperandeo, R. (2023, September). Hypothesis for Describing a Case of Gestalt Psychotherapy Using the Network and Process Model Approach with Reference to RDoC. In 2023 14th IEEE International Conference on Cognitive Infocommunications (CogInfoCom) (pp. 000033-000044). IEEE. [CrossRef]

- Cozzolino, M., & Celia, G. (2020). Psychotherapy and neuroscience: the neuroscience-oriented strategic model and the mind-body method. Phenomena Journal - International Journal of Psychopathology, Neuroscience and Psychotherapy, 2(1), 89–101. [CrossRef]

- Clarkson, P. (1989). Gestalt Counselling in Action. London: Sage Publications.

- De Lucca, F. J. (2012). A estrutura da transformação: teoria, vivência e atitude em Gestalt-terapia à luz da sabedoria organísmica. Summus Editorial.

- Diamare, S., Romano, B. ., Gagliotta, M., Giangrande, A., Motta, V., Osterini, D., & Di Laura, D. (2024). Work and Organizational Psychology in Healthcare Systems. Phenomena Journal - International Journal of Psychopathology, Neuroscience and Psychotherapy, 6(1), 12–29. [CrossRef]

- Di Leva, A. (2023). Being in the world “between” psychotherapy and neuroscience. Phenomena Journal - International Journal of Psychopathology, Neuroscience and Psychotherapy, 5(1), 21–33. [CrossRef]

- Di Sarno, A. D., Fusco, M. L., Dell’Orco, S., Cioffi, V., Sperandeo, R., Moretto, E., ... & Buonocore, G. (2018, August). Conscious experience using the Virtual Reality: A proposal of study about connection between memory and conscience. In 2018 9th IEEE International Conference on Cognitive Infocommunications (CogInfoCom) (pp. 000289-000294). IEEE.

- Ebisch, S. J., Salone, A., Ferri, F., De Berardis, D., Romani, G. L., Ferro, F. M., & Gallese, V. (2013). Out of touch with reality? Social perception in first-episode schizophrenia. Social cognitive and affective neuroscience, 8(4), 394-40. [CrossRef]

- Fuchs, T. (2021). Ecologia del cervello: fenomenologia e biologia della mente incarnata. Astrolabio.

- Francesetti, G. (2024). Il campo fenomenico: l’origine del sé e del mondo. Phenomena Journal-Giornale Internazionale di Psicopatologia, Neuroscienze e Psicoterapia, 6(1), 1-5.

- Francesetti, G., Gecele, M., & Roubal, J. (Eds.). (2014). La psicoterapia della Gestalt nella pratica clinica. Dalla psicopatologia all’estetica del contatto: Dalla psicopatologia all’estetica del contatto. FrancoAngeli. From Psychopathology to the Aesthetics of Contact; Francesetti, G., Gecele, M., Roubal, J., Eds, 59-76.

- Fuchs, T. (2021). Ecologia del cervello: fenomenologia e biologia della mente incarnata. Astrolabio.

- Ginger, S., & Ginger, A. (2004). La Gestalt. Terapia del «con-tatto» emotivo. Edizioni mediterranee.

- Goldstein, K. (1995). The organism: A holistic approach to biology derived from pathological data in man. Zone Books.

- Iannazzo, A., Stefano, S., Ruggero, L. Z., Santonicola, C., Armenante, O., Motta, V., … Rosa, V. (2023). Blended psychotherapy: integrated intervention. Phenomena Journal - International Journal of Psychopathology, Neuroscience and Psychotherapy, 5(2), 124–142. [CrossRef]

- Kepner, J. I. (2016). Body process: Il lavoro con il corpo in terapia. Franco Angeli.

- Lewin, K. (1943). Defining the’field at a given time.’. Psychological review, 50(3), 292. [CrossRef]

- Lobb, M. S. (2001). The theory of self in Gestalt therapy: A restatement of some aspects. Gestalt Review, 5(4), 276-288. [CrossRef]

- Lommatzsch, A., Cirasino, D., De Fabrizio, M., Orlando, S., Terzi, C., & Antoncecchi, M. (2024). Lavorare sull’emozione della rabbia nel disturbo di panico: un approccio psicoterapeutico fenomenologico-esistenziale e gestaltico. Phenomena Journal - Rivista Internazionale di Psicopatologia, Neuroscienze e Psicoterapia, 6 (1), 6–11. [CrossRef]

- Maciariello G., Bucciarelli F., De Blasi A.,Giangrande A., Glorioso A., Maciariello P., Perrone M. (2023). Benessere digitale vs benessere nel digitale Phenomena Journal, 5, 143-148. [CrossRef]

- Mackewn, J. (1997). Developing Gestalt Counselling. London: Sage Publications.

- Maldonato, N. M., Sperandeo, R., Valerio, P., Duval, M., Scandurra, C., & Dell’Orco, S. (2018). The centrencephalic space of functional integration: A model for complex intelligent systems. Acta Polytechnica Hungarica, 15(5), 169-184.

- Mosca, L. L., Maldonado, N. M., Di Sarno, A. D., Duval, M., Cioffi, V., Dell’Orco, S., ... & di Ronza, G. (2018, August). “I am a brain, Watson. The rest of me is a mere appendix”: The memory, a characteristic of the human being. In 2018 9th IEEE International Conference on Cognitive Infocommunications (CogInfoCom) (pp. 000295-000298). IEEE. [CrossRef]

- Orlando, G. (2020). Terapia della Gestalt e attacchi di panico: modello relazionale di base, ciclo vitale e clinica nella GTK. Phenomena Journal - Rivista internazionale di psicopatologia, neuroscienze e psicoterapia , 2 (2), 82–91. [CrossRef]

- Perls F. (1942 or ed., 1947, 1969), Ego, Hunger and Aggression: a Revision of Freud’s Theory and Method, G. Allen & Unwin, London, 1947; Vintage Books, New York, 1947; Random House, New York, 1969.

- Perls F. (1980). La terapia gestaltica parola per parola, Astrolabio, Roma.

- Perls, F. , Hefferline, R. F., & Goodman, P. (1997). Teoria e pratica della terapia della Gestalt. Astrolabio, Roma.

- Perls, F., Hefferline, R., & Goodman, P. (1951). Gestalt Therapy: Excitement and Growth in the Human Personality. New York: Julian Press. [CrossRef]

- Pessoa, L. (2023). The entangled brain. Journal of cognitive neuroscience, 35(3), 349-360. [CrossRef]

- Philippson P. (2001), Self in Relation, Gestalt Journal Press, Highland NY; Karnac Books, London.

- Philippson, P. (2001). The Emergent Self: An Existential-Gestalt Approach. London: Karnac Books.

- Pizzimenti, M., Rivetti L. (2020). ABC Gestalt. Manuale pratico per psicoterapeuti, counselor e chiunque voglia avvicinarsi a una seduta di terapia. Franco Angeli.

- Polster, E., & Polster, M. (1986). Terapia della Gestalt integrata: Profili di teoria e pratica. Giuffrè.

- Robine, J.-M. (Ed.). (2001). On the Occasion of an Other. Highland, NY: The Gestalt Journal Press.

- Robine, J. M. (2006). Il rivelarsi del sé nel contatto: studi di psicoterapia della Gestalt. F. Angeli.

- Rosa V., Ruggiero L. Z., Armenante O.,Santonicola C., Iannazzo A. (2024). Psicoterapia del Trauma e Intervento Blended: Un’ipotesi di modello integrato Phenomena Journal, 6, 54-80. [CrossRef]

- Roti, S., Berti, F., Geniola, N., Zajotti, S., Calvaresi, G., Defraia, M., & Cini, A. (2023). Un percorso gestaltico: come cambia il benessere durante un trattamento gestaltico. Phenomena Journal - Rivista Internazionale di Psicopatologia, Neuroscienze e Psicoterapia , 5 (2). [CrossRef]

- Roumeliotis, K. I., & Tselikas, N. D. (2023). Chatgpt and open-ai models: A preliminary review. Future Internet, 15(6), 192. [CrossRef]

- Scarito, F. P. (2021). Memory reconsolidation: Towards a unified model of change in psychotherapy. Phenomena Journal - International Journal of Psychopathology, Neuroscience and Psychotherapy, 3(1), 27–34. [CrossRef]

- Sperandeo, R., Mosca, L. L., Alfano, Y. M., Cioffi, V., Di Sarno, A. D., Galchenko, A., ... & Maldonato, N. M. (2019, October). Complexity in the narration of the self A new theoretical and methodological perspective of diagnosis in psychopathology based on the computational method. In 2019 10th IEEE International Conference on Cognitive Infocommunications (CogInfoCom) (pp. 445-450). IEEE. [CrossRef]

- Sperandeo, R., Maldonato, M., Moretto, E., & Dell’Orco, S. (2019). Executive Functions and Personality from a Systemic-Ecological Perspective: A Quantitative Analysis of the Interactions Among Emotional, Cognitive and Aware Dimensions of Personality. Cognitive Infocommunications, Theory and Applications, 79-90. [CrossRef]

- Stevens, J. O. (1971). Awareness: Exploring, Experimenting, Experiencing. Moab, UT: Real People Press.

- Wertheimer, M. (1938). Laws of organization in perceptual forms. In W. D. Ellis (Ed.), A source book of Gestalt psychology (pp. 71–88). Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner & Company.

- Yontef, G. (1993). Awareness, Dialogue, and Process: Essays on Gestalt Therapy. Highland, NY: The Gestalt Journal Press.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).