Submitted:

11 June 2025

Posted:

12 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

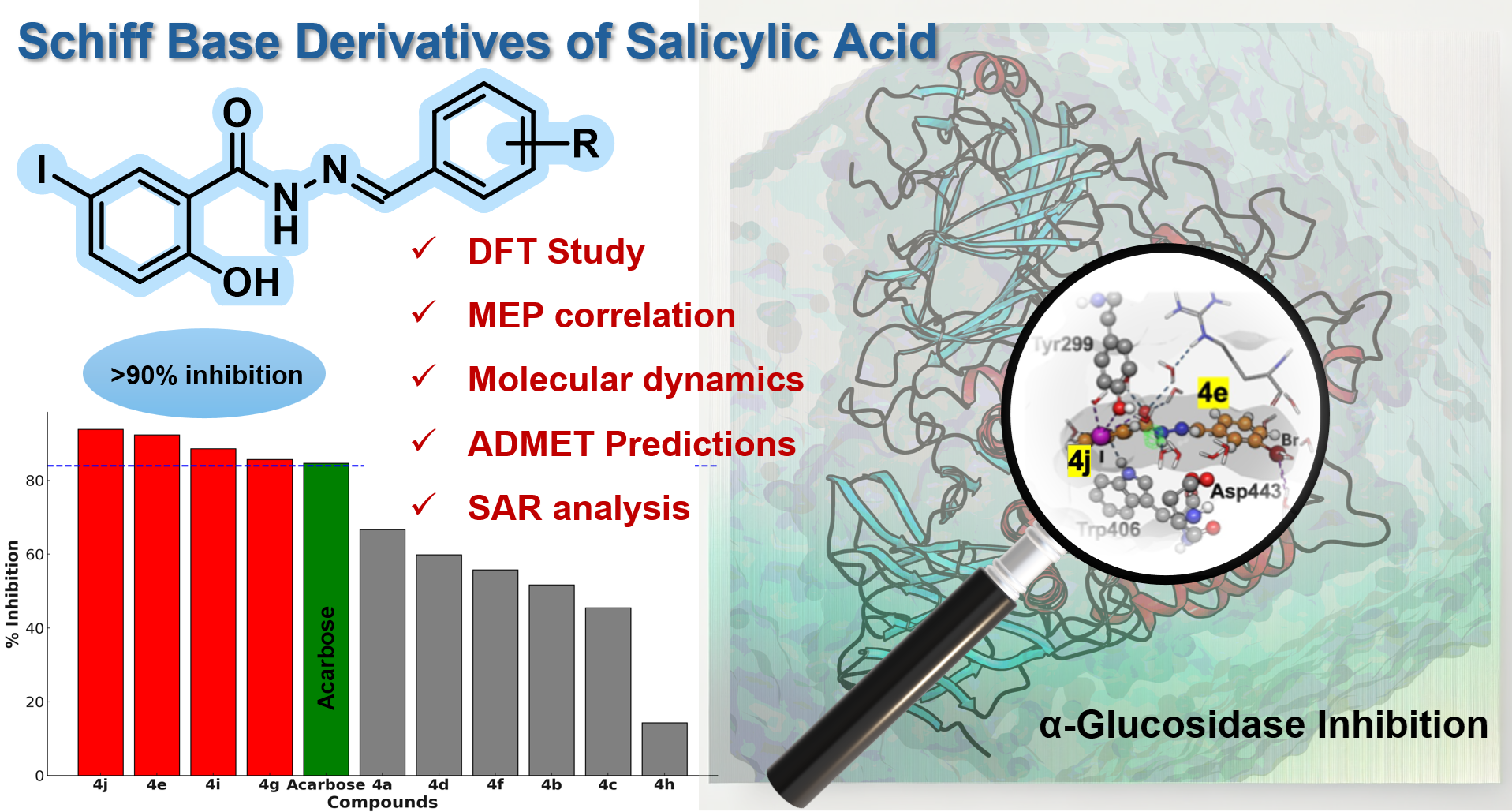

Abstract

Keywords:

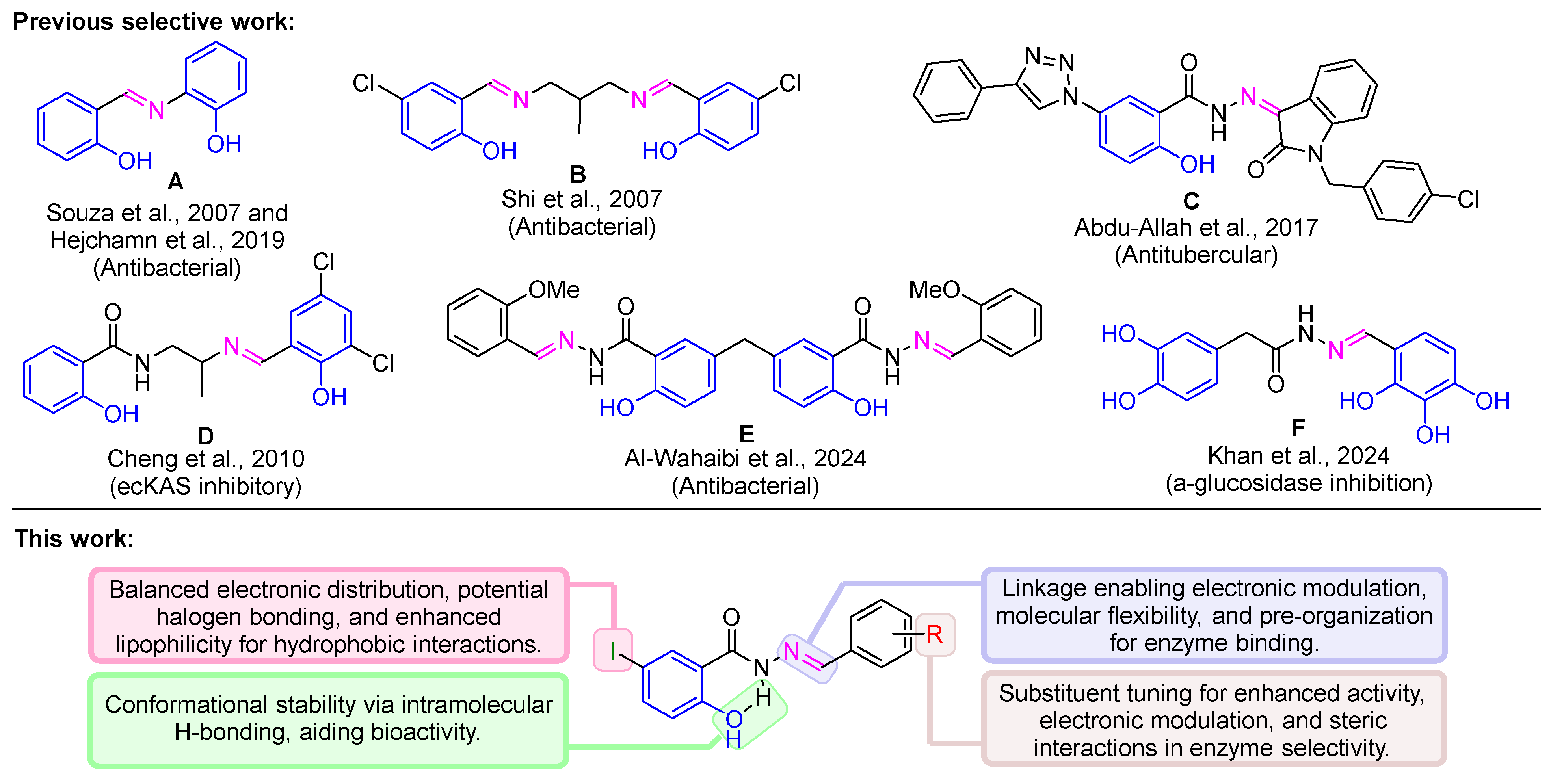

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. General Method

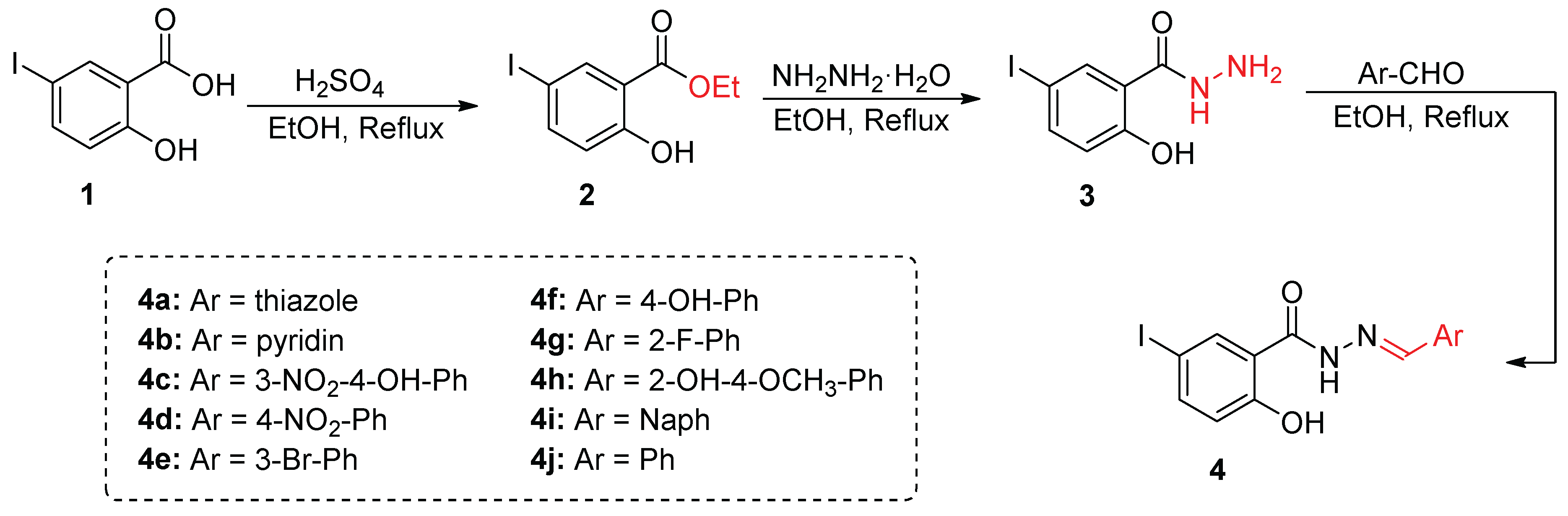

2.2. Synthesis and Characterization

2.2.1. 5-Iodo-2-Salicylic Ester (2)

2.2.2. 5-Iodo-2-Hydroxybenzo-hydrazide (3)

2.2.3. General Procedure for the Synthesis

2.3. Biological Assay

2.3.1. Screening for α-Glucosidase Inhibitory Activity

2.3.2. Determination of IC50 Values

2.4. Theoretical Study

2.4.1. Density Functional Theory (DFT) and Molecular Electrostatic Potential (MEP)

2.4.2. Molecular Docking (MD) and Molecular Dynamics Simulations (MDS)

2.4.3. ADMET Profiling

2.4.4. SAR and Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Synthesis and Characterization

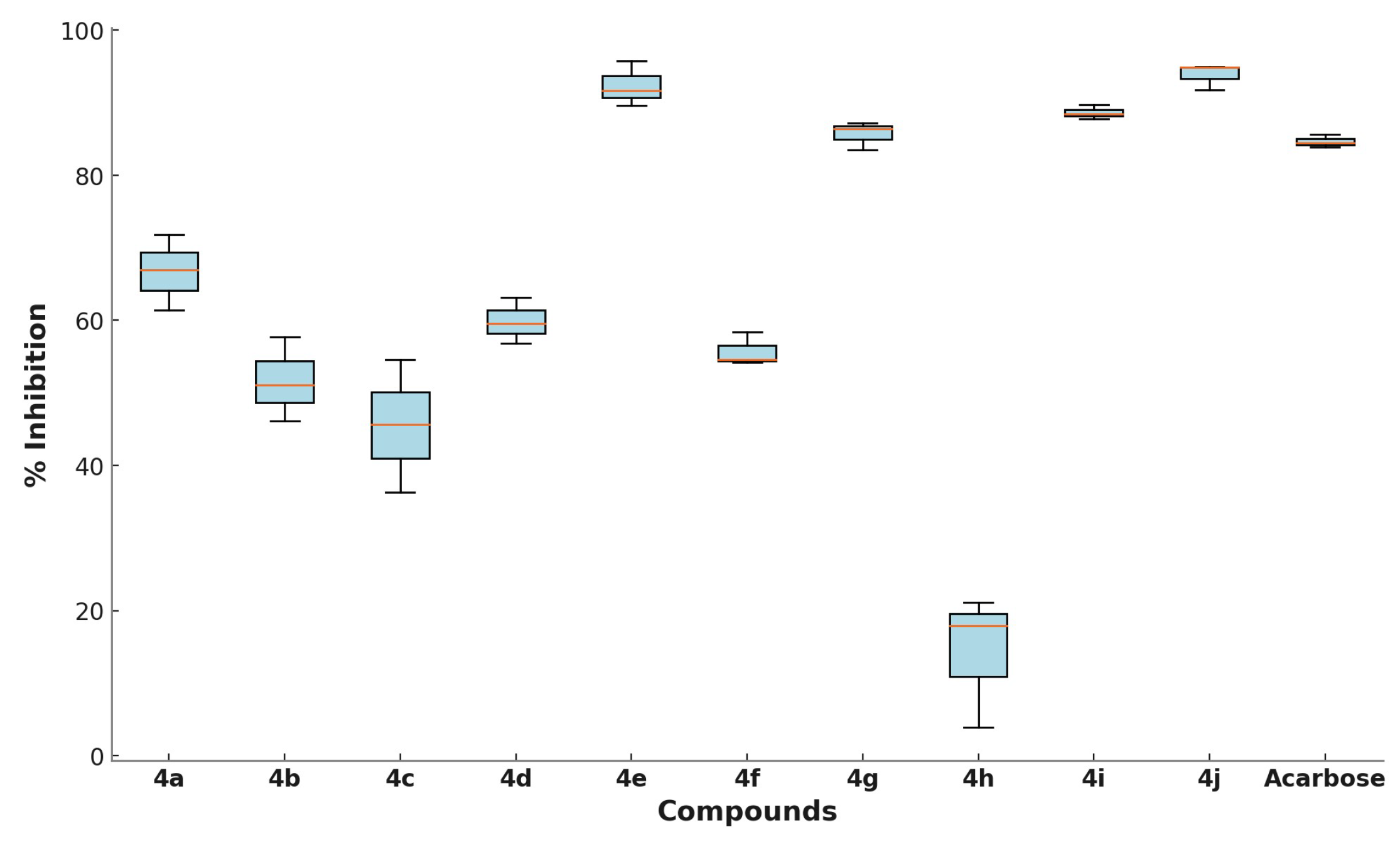

3.2. α-Glucosidase Inhibition Assay

3.3. Density Functional Theory (DFT) Study

3.4. Molecular Dynamics Simulations

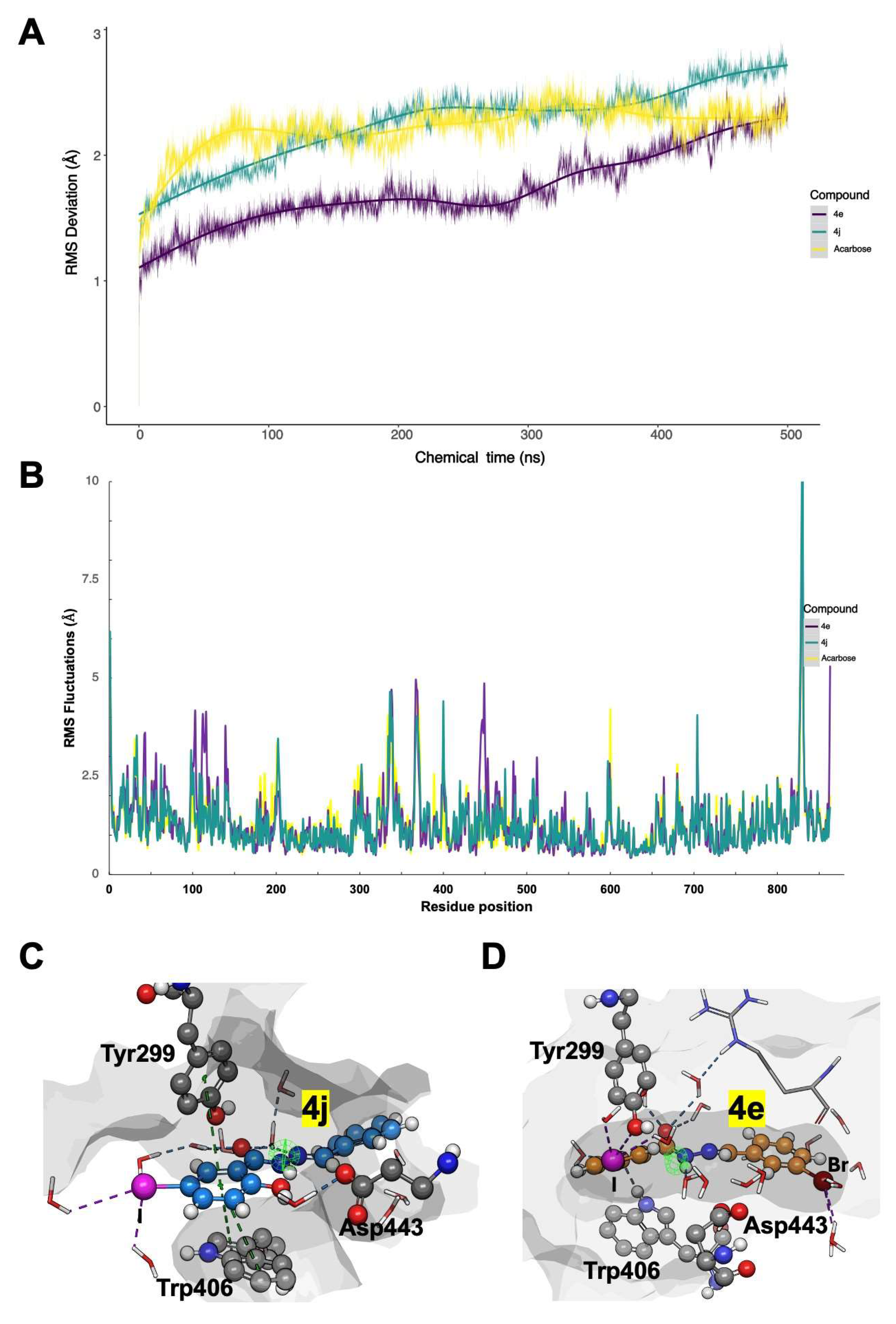

3.5. Molecular Dynamics Simulation for 4e and 4j

3.6. ADMET Profiling of Acarbose, 4e, and 4j

3.7. Structure-Activity Relationship (SAR) Analysis

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Diabetes: Fact Sheet; World Health Organization: Geneva, 2024; Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/diabetes (accessed on 31 December 2024).

- International Diabetes Federation. IDF Diabetes Atlas, 10th ed.; International Diabetes Federation: Brussels, 2021; Available online: https://diabetesatlas.org (accessed on 31 December 2024).

- International Diabetes Federation. Diabetes Facts and Figures; International Diabetes Federation: Brussels, 2024; Available online: https://idf.org (accessed on 31 December 2024).

- American Diabetes Association Professional Practice Committee. Retinopathy, Neuropathy, and Foot Care: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes—2022. Diabetes Care 2022, 45, S185–S194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratner, R. E. Controlling Postprandial Hyperglycemia. Am. J. Cardiol. 2001, 88, 26–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Citarella, A.; Cavinato, M.; Rosini, E.; Shehi, H.; Ballabio, F.; Camilloni, C.; Fasano, V.; Silvani, A.; Passarella, D.; Pollegioni, L.; Nardini, M. Nicotinic Acid Derivatives as Novel Noncompetitive α-Amylase and α-Glucosidase Inhibitors for Type 2 Diabetes Treatment. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2024, 15, 1474–1481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Liu, C.; Hu, L. Fragment-Based Dynamic Combinatorial Chemistry for Identification of Selective α-Glucosidase Inhibitors. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2022, 13, 1791–1796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mwakalukwa, R.; Amen, Y.; Nagata, M.; Shimizu, K. Postprandial Hyperglycemia Lowering Effect of the Isolated Compounds from Olive Mill Wastes – An Inhibitory Activity and Kinetics Studies on α-Glucosidase and α-Amylase Enzymes. ACS Omega 2020, 5, 20070–20079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Xie, L.; Xie, J.; Liu, Y.; Chen, W. Pelargonidin-3-O-Rutinoside as a Novel α-Glucosidase Inhibitor for Improving Postprandial Hyperglycemia. Chem. Commun. 2019, 55, 39–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanefeld, M. The Role of Acarbose in the Treatment of Non-Insulin-Dependent Diabetes Mellitus. J. Diabetes Complicat. 1998, 12, 228–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kageyama, S.; Nakamichi, N.; Sekino, H.; Nakano, S. Comparison of the Effects of Acarbose and Voglibose in Healthy Subjects. Clin. Ther. 1997, 19, 720–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashtoh, H.; Baek, K.-H. Recent Updates on Phytoconstituent Alpha-Glucosidase Inhibitors: An Approach towards the Treatment of Type Two Diabetes. Plants 2022, 11, 2722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.-S.; Xie, H.-X.; Zhang, J.-H.; Li, Y.; Zhang, J.; Wang, K.-M.; Jiang, C.-S. An Updated Overview of Synthetic α-Glucosidase Inhibitors: Chemistry and Bioactivities. Curr. Med. Chem. 2023, 23, 2488–2526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moya-Garzón, M. D.; Martín Higueras, C.; Peñalver, P.; Romera, M.; Fernandes, M. X.; Franco-Montalbán, F.; Gómez-Vidal, J. A.; Salido, E.; Díaz-Gavilán, M. Salicylic Acid Derivatives Inhibit Oxalate Production in Mouse Hepatocytes with Primary Hyperoxaluria Type 1. J. Med. Chem. 2018, 61, 7144–7167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Forster, E. R.; Darabedian, N.; Kim, A. T.; Pratt, M. R.; Shen, A.; Hang, H. C. Translation of Microbiota Short-Chain Fatty Acid Mechanisms Affords Anti-Infective Acyl-Salicylic Acid Derivatives. ACS Chem. Biol. 2020, 15, 1141–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Lu, W.; Chen, H.; Bian, X.; Yang, G. A New Series of Salicylic Acid Derivatives as Non-Saccharide α-Glucosidase Inhibitors and Antioxidants. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2019, 42, 231–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aminu, K. S.; Uzairu, A.; Umar, A. B.; Ibrahim, M. T. Salicylic Acid Derivatives as Potential α-Glucosidase Inhibitors: Drug Design, Molecular Docking, and Pharmacokinetic Studies. Bull. Natl. Res. Cent. 2022, 46, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harohally, N.V.; Cherita, C.; Bhatt, P.; Appaiah, K.A. Antiaflatoxigenic and Antimicrobial Activities of Schiff Bases of 2-Hydroxy-4-methoxybenzaldehyde, Cinnamaldehyde, and Similar Aldehydes. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2017, 65, 8773–8778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thakor, P.M.; Patel, J.D.; Patel, R.J.; Chaki, S.H.; Khimani, A.J.; Vaidya, Y.H.; Chauhan, A.P.; Dholakia, A.B.; Patel, V.C.; Patel, A.J.; Bhavsar, N.H.; Patel, H.V. Exploring New Schiff Bases: Synthesis, Characterization, and Multifaceted Analysis for Biomedical Applications. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 35431–35448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afzal, H.R.; Khan, N.H.; Sultana, K.; Mobashar, A.; Lareb, A.; Khan, A.; Gull, A.; Afzaal, H.; Khan, M.T.; Rizwan, M.; Imran, M. Schiff Bases of Pioglitazone Provide Better Antidiabetic and Potent Antioxidant Effect in a Streptozotocin–Nicotinamide-Induced Diabetic Rodent Model. ACS Omega 2021, 6, 4470–4479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarfraz, M.; Ayyaz, M.; Rauf, A.; Yaqoob, A.; Tooba, *!!! REPLACE !!!*; Ali, M.A.; Siddique, S.A.; Qureshi, A.M.; Sarfraz, M.H.; Aljowaie, R.M.; Almutairi, S.M.; Arshad, M. New Pyrimidinone Bearing Aminomethylenes and Schiff Bases as Potent Antioxidant, Antibacterial, SARS-CoV-2, and COVID-19 Main Protease MPro Inhibitors: Design, Synthesis, Bioactivities, and Computational Studies. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 25730–25747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mushtaq, I.; Ahmad, M.; Saleem, M.; Ahmed, A. Pharmaceutical Significance of Schiff Bases: An Overview. Futur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2024, 10, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, A. O.; Galetti, F.; Silva, C. L.; Bicalho, B.; Parma, M. M.; Fonseca, S. F.; et al. Synthesis and Antimicrobial Activity of Novel Schiff Bases. Quim. Nova 2007, 30, 1563–1566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hejchman, E.; Kruszewska, H.; Maciejewska, D.; Sowirka-Taciak, B.; Tomczyk, M.; Sztokfisz-Ignasiak, A.; Jankowski, J.; Młynarczuk-Biały, I. Design, Synthesis, and Biological Activity of Schiff Bases Bearing Salicyl and 7-Hydroxycoumarinyl Moieties. Monatsh. Chem. 2019, 150, 255–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, L.; Ge, H.-M.; Tan, S.-H.; Li, H.-Q.; Song, Y.-C.; Zhu, H.-L. Antibacterial Activity of Schiff Bases Derived from 3-Hydroxyquinoxaline-2-carboxaldehyde. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2007, 42, 558–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdu-Allah, H. H.; Youssif, B. G.; Abdelrahman, M. H.; Abdel-Hamid, M. K.; Reshma, R. S.; Yogeeswari, P.; et al. Synthesis and Biological Activity of Hydrazones of o- and p-Hydroxybenzoic Acids. Russ. J. Gen. Chem. 2017, 87, 2299–2306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, K.; Zheng, Q.-Z.; Hou, J.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, C.-H.; Zhao, J.; et al. Design, Synthesis, and Biological Evaluation of Novel Schiff Bases as Enzyme Inhibitors. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2010, 18, 2447–2455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Wahaibi, L. H.; Mahmoud, M. A.; Alzahrani, H. A.; Abou-Zied, H. A.; Gomaa, H. A. M.; Youssif, B. G. M.; Bräse, S.; Rabea, S. M. Investigating Novel Chemical Scaffolds in Medicinal Chemistry. Front. Chem. 2024, 12, Article–1419242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, H.; Jan, F.; Shakoor, A.; Khan, A.; AlAsmari, A. F.; Alasmari, F.; et al. Design, Synthesis, Molecular Docking Study, and α-Glucosidase Inhibitory Evaluation of Novel Hydrazide–Hydrazone Derivatives of 3,4-Dihydroxyphenylacetic Acid. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 11410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guha, R. On Exploring Structure–Activity Relationships. In Methods in Molecular Biology; Ekins, S., Ed.; Humana Press: Totowa, NJ, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waziri, I.; Yusuf, T. L.; Kelani, M. T.; Akintemi, E. O.; Olofinsan, K. A.; Muller, A. J. Exploring the Potential of N-Benzylidenebenzohydrazide Derivatives as Antidiabetic and Antioxidant Agents: Design, Synthesis, Spectroscopic, Crystal Structure, DFT, and Molecular Docking Study. ChemistrySelect 2024, 9, e202401631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, J.-D.; Head-Gordon, M. Long-Range Corrected Hybrid Density Functionals with Damped Atom–Atom Dispersion Corrections. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2008, 10, 6615–6620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weigend, F.; Ahlrichs, R. Balanced Basis Sets of Split Valence, Triple Zeta Valence and Quadruple Zeta Valence Quality for H to Rn: Design and Assessment of Accuracy. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2005, 7, 3297–3305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sim, L.; Quezada-Calvillo, R.; Sterchi, E.E.; Nichols, B.L.; Rose, D.R. Human Intestinal Maltase–Glucoamylase: Crystal Structure of the N-Terminal Catalytic Subunit and Basis of Inhibition and Substrate Specificity. J. Mol. Biol. 2008, 375, 782–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsson, M.H.M.; Søndergaard, C.R.; Rostkowski, M.; Jensen, J.H. PROPKA3: Consistent Treatment of Internal and Surface Residues in Empirical pKa Predictions. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2011, 7, 525–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jorgensen, W.L.; Maxwell, D.S.; Tirado-Rives, J. Development and Testing of the OPLS All-Atom Force Field on Conformational Energetics and Properties of Organic Liquids. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1996, 118, 11225–11236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, G.; Wu, Z.; Yi, J.; Fu, L.; Yang, Z.; Hsieh, C.; Yin, M.; Zeng, X.; Wu, C.; Chen, X.; Hou, T.; Cao, D. ADMETlab 2.0: An Integrated Online Platform for Accurate and Comprehensive Predictions of ADMET Properties. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, W5–W14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nurkenov, O.A.; Satpaeva, Zh.B.; Schepetkin, I.A.; Khlebnikov, A.I.; Turdybekov, K.M.; Seilkhanov, T.M.; Fazylov, S.D. Synthesis and Biological Activity of Hydrazones of o- and p-Hydroxybenzoic Acids. Russ. J. Gen. Chem. 2017, 87, 2299–2306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNutt, A.T.; Francoeur, P.; Aggarwal, R.; Masuda, T.; Meli, R.; Ragoza, M.; Sunseri, J.; Koes, D.R. GNINA 1.0: Molecular Docking with Deep Learning. J. Cheminf. 2021, 13, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quiroga, R.; Villarreal, M.A. Vinardo: A Scoring Function Based on Autodock Vina Improves Scoring, Docking, and Virtual Screening. PLoS One 2016, 11, e0155183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

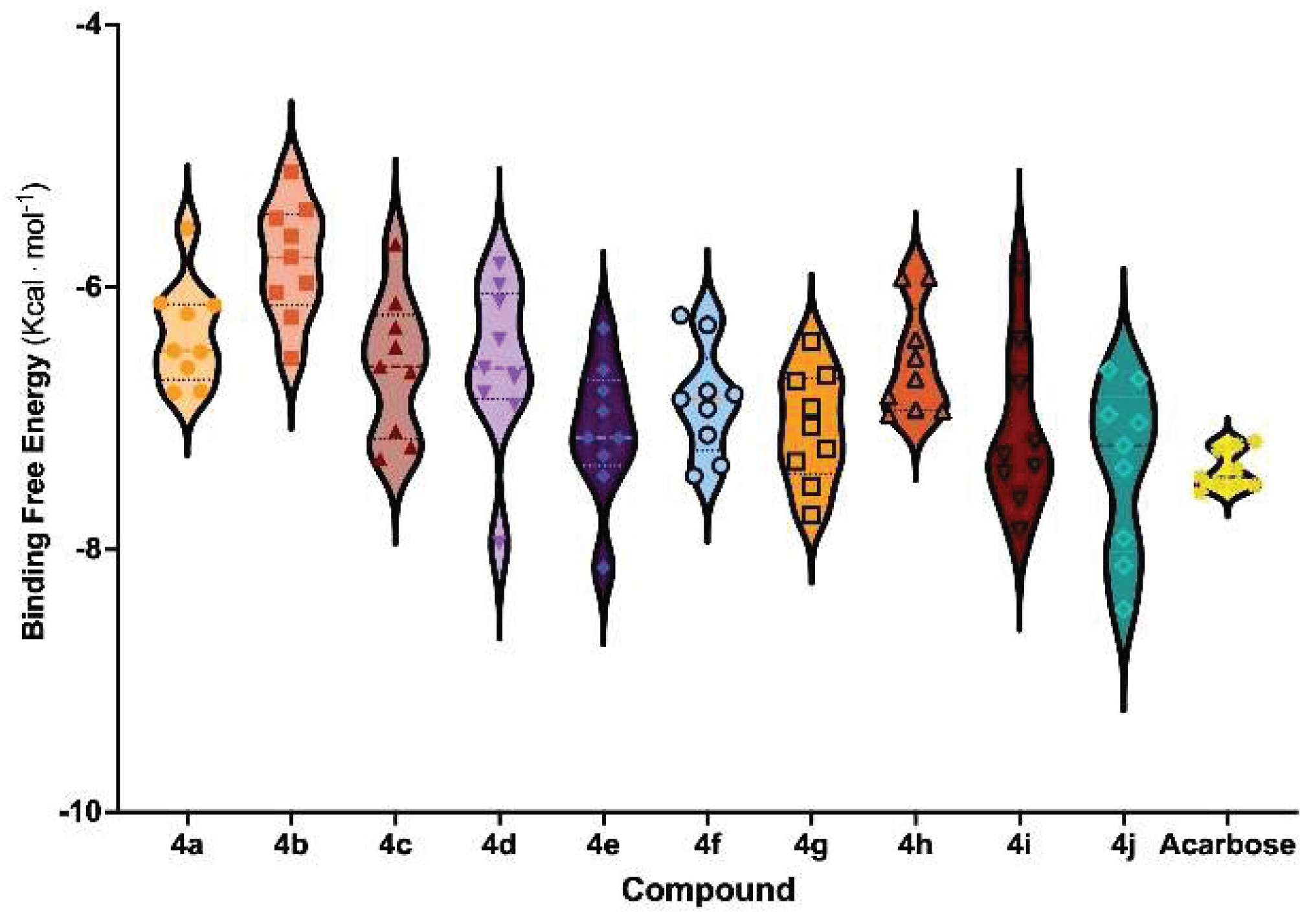

| Entry | Compounds | Ar | % inhibition 1 | IC50 (µM) | ΔE 2 (eV) |

BFE 3 (Kcal mol-1) |

Affinity 4 (pK units) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 4a | thiazole | 66.71 ± 4.27 | nd5 | 7.89 | -6.46 ± 0.62 | 4.74 ± 0.33 |

| 2 | 4b | pyridine | 51.65 ± 4.72 | nd | 8.09 | -5.83 ± 0.58 | 4.78 ± 0.35 |

| 3 | 4c | 3-NO2-4-OH-Ph | 45.51 ± 7.45 | nd | 7.24 | -6.62 ± 0.66 | 4.60 ± 0.27 |

| 4 | 4d | 4-NO2-Ph | 59.86 ± 2.60 | nd | 7.60 | -6.61 ± 0.78 | 4.69 ± 0.27 |

| 5 | 4e | 3-Br-Ph | 92.35 ± 2.52 | 14.86 ± 0.24 | 8.03 | -7.23 ± 0.64 | 4.63 ± 0.26 |

| 6 | 4f | 4-OH-Ph | 55.75 ± 1.91 | nd | 7.73 | -6.87 ± 0.60 | 4.77 ± 0.26 |

| 7 | 4g | 2-F-Ph | 85.69 ± 1.59 | 15.58 ± 0.30 | 8.04 | -7.09 ± 0.63 | 4.71 ± 0.23 |

| 8 | 4h | 2-OH-4-OCH3-Ph | 14.33 ± 7.47 | nd | 7.50 | -6.59 ± 0.59 | 4.64 ± 0.24 |

| 9 | 4i | Naph | 88.64 ± 0.78 | 18.05 ± 0.92 | 7.62 | -7.10 ± 0.88 | 4.67 ± 0.20 |

| 10 | 4j | Ph | 93.84 ± 1.49 | 17.56 ± 0.39 | 8.01 | -7.38 ± 0.82 | 4.78 ± 0.31 |

| 11 | Acarbose | - | 84.66 ± 0.71 | 45.78 ± 1.95 | - | -7.41 ± 0.79 | 5.00 ± 0.22 |

| Parameters | Acarbose | 4e | 4j |

|---|---|---|---|

| MW (g/mol) | 645.2 | 443.9 | 365.99 |

| H-bond donors | 14.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 |

| H-bond acceptors | 19.0 | 4.0 | 4.0 |

| logPo/w1 | −4.064 | 4.559 | 4.253 |

| logSwat2 | 0.591 | −5.999 | −5.466 |

| Lipinski’s Rule | Rejected | Accepted | Accepted |

| Pfizer Rule | Accepted | Rejected | Rejected |

| Apparent Caco-2 Permeability log(nm/s)3 | −6.472 | −4.928 | −4.750 |

| Apparent MDCK Permeability log(nm/s)4 | 0.0 | −4.704 | −4.837 |

| Skin sensitization5 | 1.0 | 0.944 | 0.906 |

| Human Intestinal Absorption | Low | Low | Low |

| % Plasma Protein Binding6 | 13.03 | 99.09 | 98.82 |

| CYP1A2 inhibitors7 | 0.0 | 0.979 | 0.999 |

| CYP2C8 inhibitors8 | 0.942 | 0.999 | 0.998 |

| Nephrotoxicity9 | 0.981 | 0.374 | 0.493 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).