Submitted:

10 June 2025

Posted:

12 June 2025

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study design and sample collection

2.2. Microbiological Analysis

2.3. Risk Assessment and Statistical Analysis

3. Results

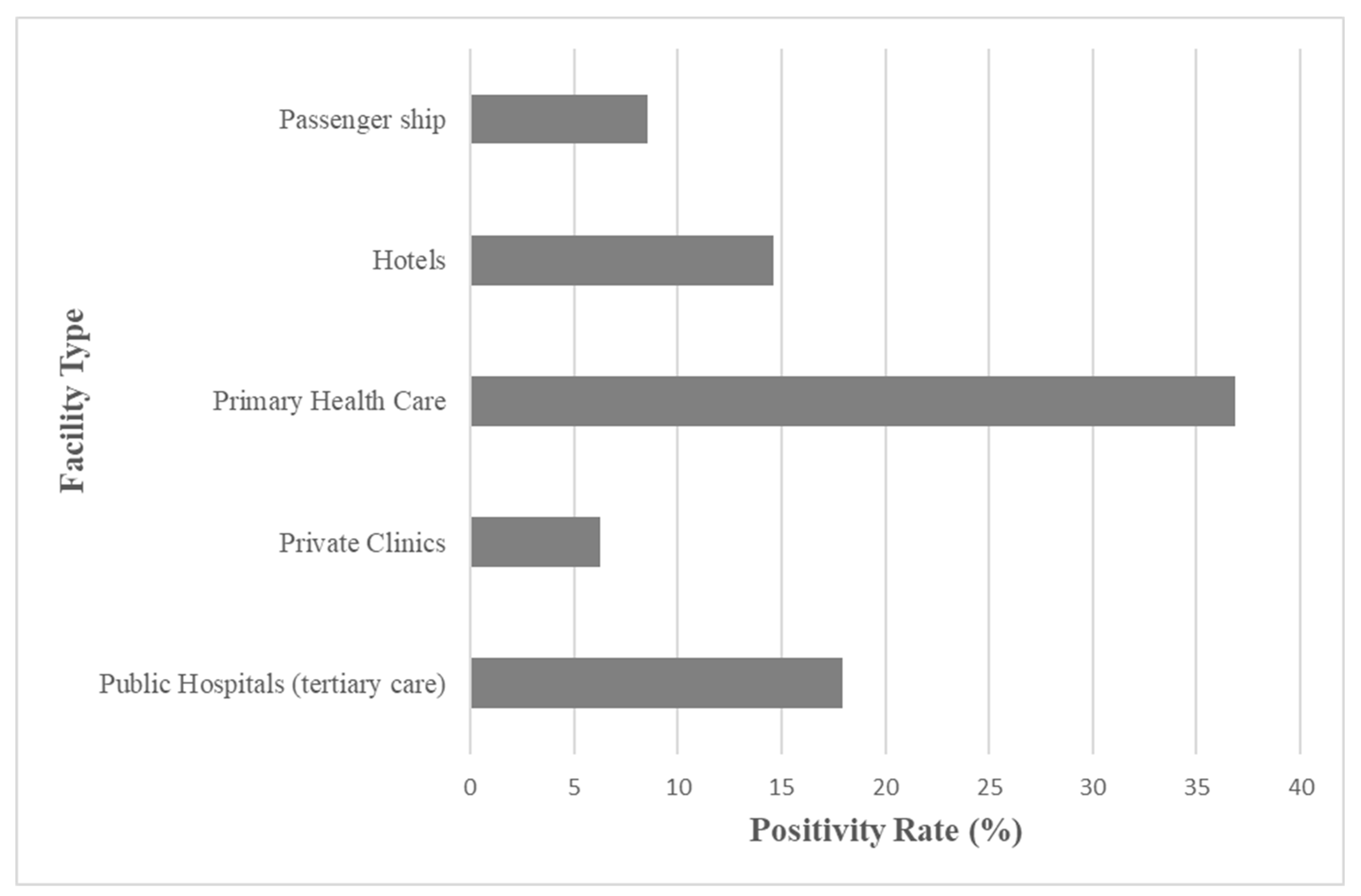

3.1. Sampling Scope and Facility Comparison

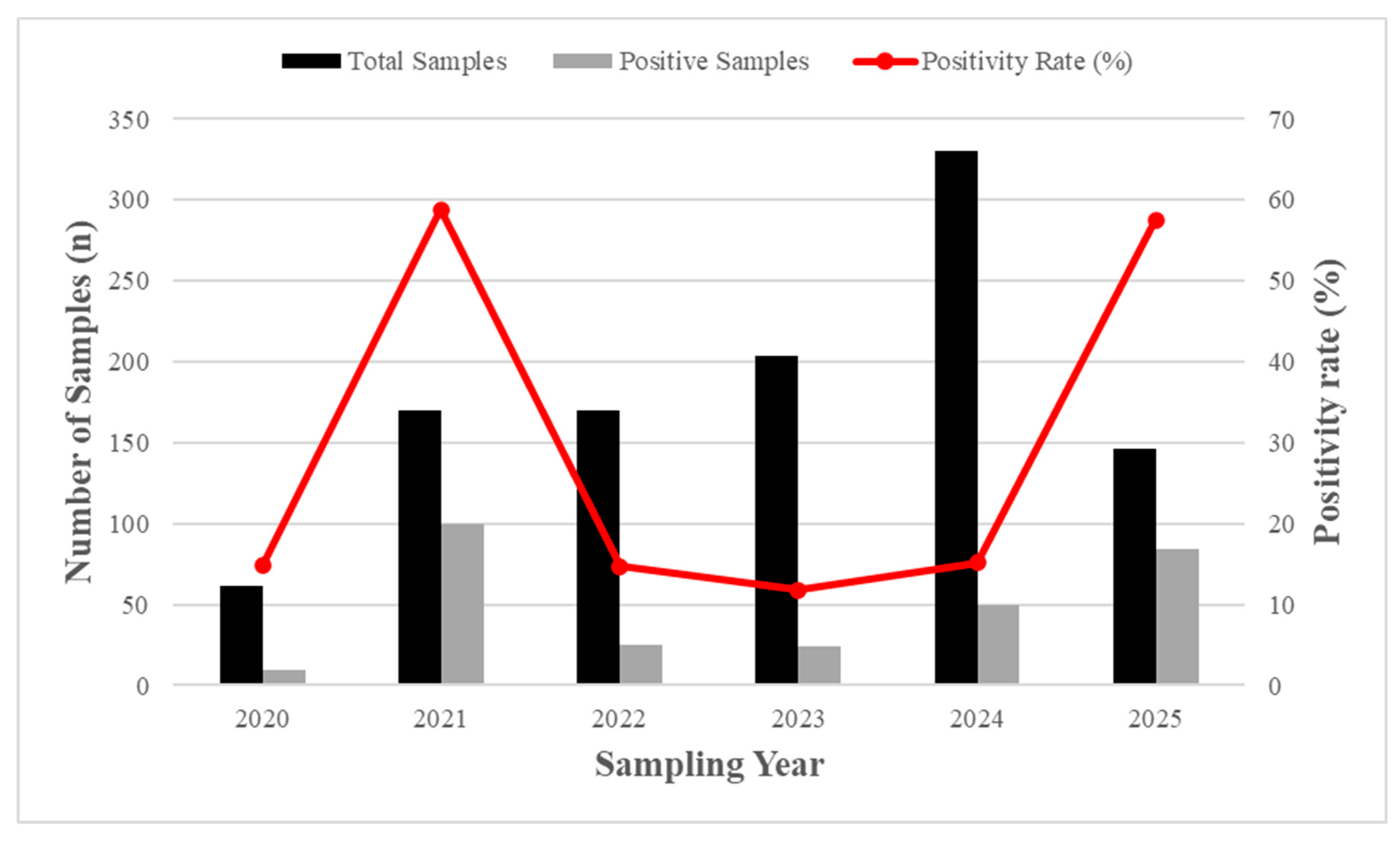

3.2. Legionella Positivity and Temporal Trends

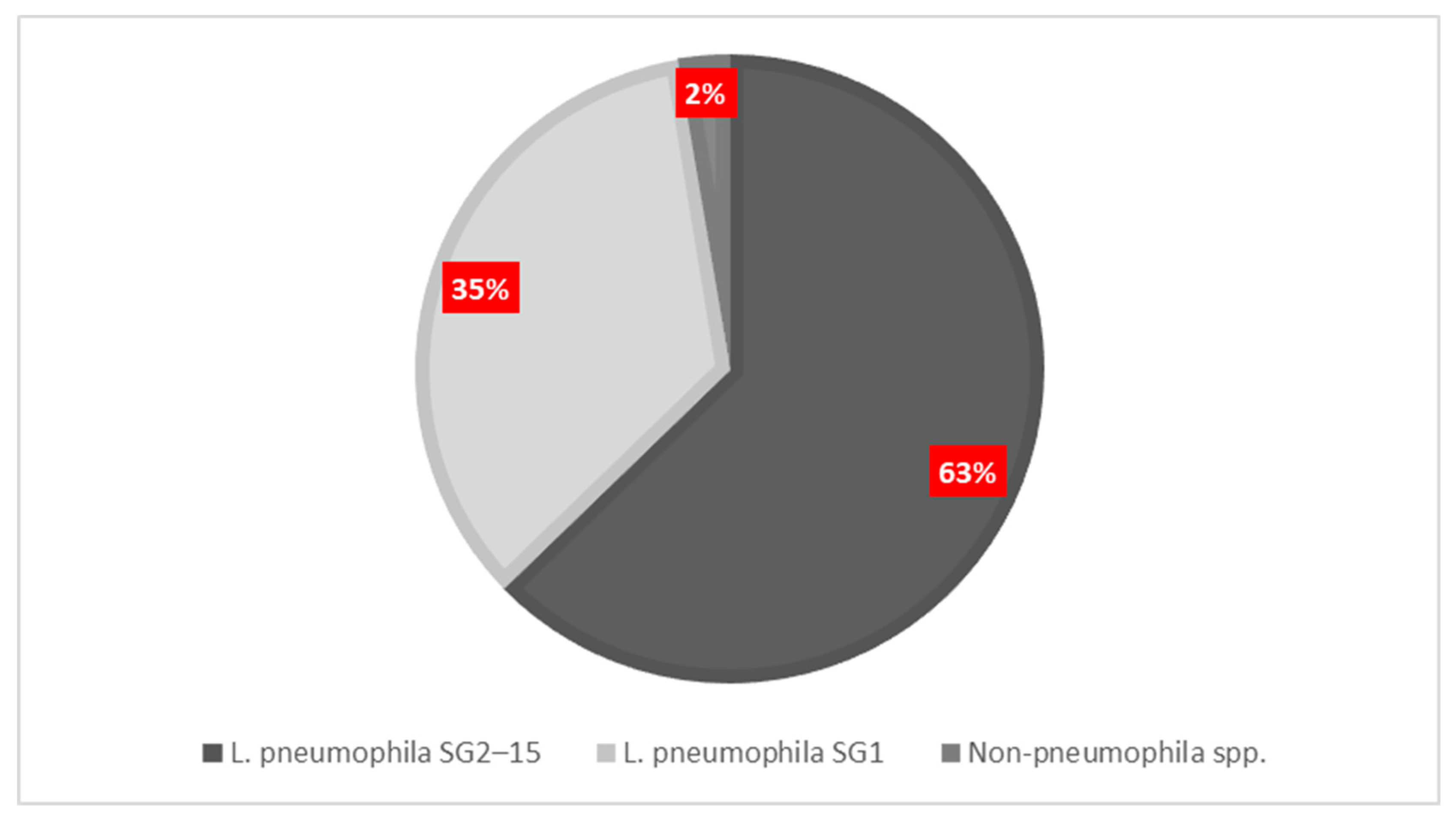

3.3. Serogroup Distribution and Facility Colonization Risks

3.4. Temporal evolution, Positivity Trends and Post-COVID Risk Profile

3.4.1. Hotels: Post-COVID Risk Profile

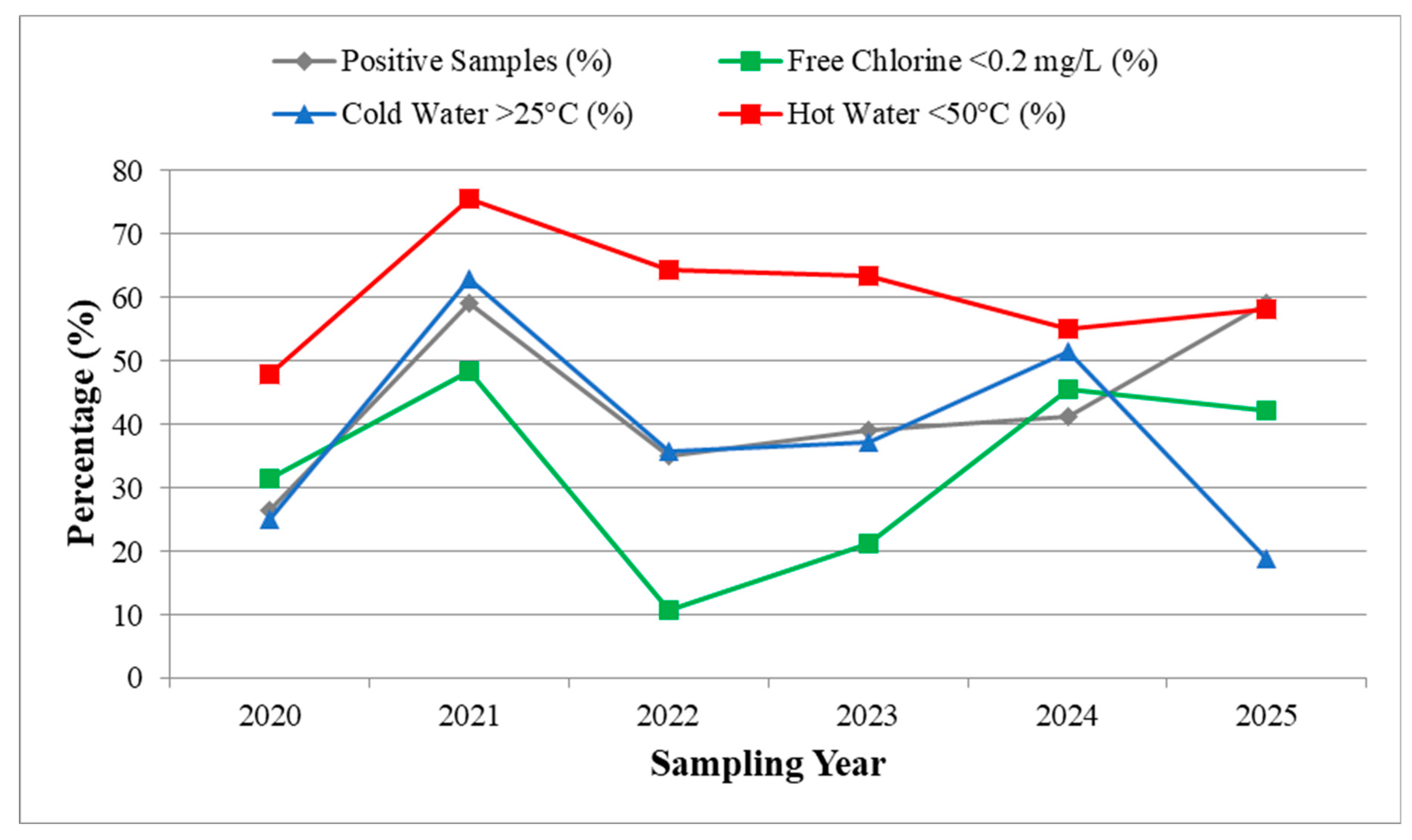

3.5. Environmental Risk Factors and Relative Risk Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Renwick, D.V.; Heinrich, A.; Weisman, R.; Arvanaghi, H.; Rotert, K. Potential Public Health Impacts of Deteriorating Distribution System Infrastructure. J Am Water Works Assoc 2019, 111, 42–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Public Water Supply Distribution Systems Assessing and Reducing Risks | National Academies Available online:. Available online: https://www.nationalacademies.org/our-work/public-water-supply-distribution-systems-assessing-and-reducing-risks (accessed on 6 June 2025).

- Public Water Supply Distribution Systems: Assessing and Reducing Risks -- First Report; National Academies Press: Washington, D.C., 2005. ISBN 978-0-309-09628-7.

- LeChevallier, M.W.; Prosser, T.; Stevens, M. Opportunistic Pathogens in Drinking Water Distribution Systems—A Review. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brady, M.F.; Awosika, A.O.; Nguyen, A.D.; Sundareshan, V. Legionnaires Disease. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island (FL), 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Rello, J.; Allam, C.; Ruiz-Spinelli, A.; Jarraud, S. Severe Legionnaires’ Disease. Annals of Intensive Care 2024, 14, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papageorgiou, K.; Chronis, E.; Tzouanopoulos, A.; Steris, V.; Koutsopoulos, D.; Tzavaras, I.; Paraskevopoulos, K.; Karolidis, S. Prevalence of Legionella Spp. in the Water Distribution Systems of Northern Greece. EUR J ENV PUBLIC HLT 2023, 7, em0147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadakis, A.; Chochlakis, D.; Sandalakis, V.; Keramarou, M.; Tselentis, Y.; Psaroulaki, A. Legionella Spp. Risk Assessment in Recreational and Garden Areas of Hotels. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2018, 15, 598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mnisi, Z.F.; Delair, Z.; Singh, A. Legionella in Urban and Rural Water, a Tale of Two Environments. Water 2025, 17, 1491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legionnaires’ Disease - Annual Epidemiological Report for 2021. Available online: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications-data/legionnaires-disease-annual-epidemiological-report-2021 (accessed on 5 June 2025).

- Legionnaires’ Disease - Annual Epidemiological Report for 2021. Available online: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications-data/legionnaires-disease-annual-epidemiological-report-2021 (accessed on 3 June 2025).

- Hoge, C.W.; Breiman, R.F. Advances in the Epidemiology and Control of Legionella Infections. Epidemiologic Reviews 1991, 13, 329–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Hoof, J.; Hornstra, L.M.; van der Blom, E.; Nuijten, O.W.; van der Wielen, P.W. The Presence and Growth of Legionella Species in Thermostatic Shower Mixer Taps: An Exploratory Field Study. Building Services Engineering Research & Technology 2014, 35, 600–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laganà, P.; Gioffrè, M.E.; Delia, S.A.; Facciolà, A. Legionella Spp. in Thermal Facilities: A Public Health Issue in the One Health Vision. Water 2023, 15, 689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyritsi, M.A.; Mouchtouri, V.A.; Katsioulis, A.; Kostara, E.; Nakoulas, V.; Hatzinikou, M.; Hadjichristodoulou, C. Legionella Colonization of Hotel Water Systems in Touristic Places of Greece: Association with System Characteristics and Physicochemical Parameters. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2018, 15, 2707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, M.; Ross, K.; Bentham, R. Legionella, Protozoa, and Biofilms: Interactions within Complex Microbial Systems. Microb Ecol 2009, 58, 538–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lau, H. y.; Ashbolt, N. j. The Role of Biofilms and Protozoa in Legionella Pathogenesis: Implications for Drinking Water. Journal of Applied Microbiology 2009, 107, 368–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valster, R.M.; Wullings, B.A.; van der Kooij, D. Detection of Protozoan Hosts for Legionella Pneumophila in Engineered Water Systems by Using a Biofilm Batch Test. Appl Environ Microbiol 2010, 76, 7144–7153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincenti, S.; Nurchis, M.C.; Boninti, F.; Sapienza, M.; Raponi, M.; Pattavina, F.; Pesaro, C.; D’Alonzo, C.; Damiani, G.; Laurenti, P. An Innovative Device for the Hot Water Circuit in Hospitals to Save Energy Without Compromising the Safety and Quality of Water: Preliminary Results. Water 2025, 17, 692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexandropoulou, I.G.; Ntougias, S.; Konstantinidis, T.G.; Parasidis, T.A.; Panopoulou, M.; Constantinidis, T.C. Environmental Surveillance and Molecular Epidemiology of Waterborne Pathogen Legionella Pneumophila in Health-Care Facilities of Northeastern Greece: A 4-Year Survey. Environ Sci Pollut Res 2015, 22, 7628–7640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naher, N.; Bari, M.L.; Ahmed, S. Risk Assessment and Detection of Legionella Species in the Water System of A Luxury Hotel in Dhaka City, Bangladesh. Bangladesh Journal of Microbiology 2023, 40, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadakis, A.; Keramarou, M.; Chochlakis, D.; Sandalakis, V.; Mouchtouri, V.A.; Psaroulaki, A. Legionella Spp. Colonization in Water Systems of Hotels Linked with Travel-Associated Legionnaires’ Disease. Water 2021, 13, 2243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mellou, K.; Mplougoura, A.; Mandilara, G.; Papadakis, A.; Chochlakis, D.; Psaroulaki, A.; Mavridou, A. Swimming Pool Regulations in the COVID-19 Era: Assessing Acceptability and Compliance in Greek Hotels in Two Consecutive Summer Touristic Periods. Water 2022, 14, 796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadakis, A.A.; Tsirigotakis, I.; Katranitsa, S.; Donousis, C.; Papalexis, P.; Keramydas, D.; Chaidoutis, E.; Georgakopoulou, V.E.; Spandidos, D.A.; Constantinidis, T.C. Assessing the Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic Health Protocols on the Hygiene Status of Swimming Pools of Hotel Units. Medicine International 2023, 3, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrigo, I.; Galia, E.; Fasciana, T.; Diquattro, O.; Tricoli, M.R.; Serra, N.; Palermo, M.; Giammanco, A. Four-Year Environmental Surveillance Program of Legionella Spp. in One of Palermo’s Largest Hospitals. Microorganisms 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goutziana, G.; Mouchtouri, V.A.; Karanika, M.; Kavagias, A.; Stathakis, N.E.; Gourgoulianis, K.; Kremastinou, J.; Hadjichristodoulou, C. Legionella Species Colonization of Water Distribution Systems, Pools and Air Conditioning Systems in Cruise Ships and Ferries. BMC Public Health 2008, 8, 390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kourentis, L.; Anagnostopoulos, L.; Tsinaris, Z.; Galanopoulos, A.P.; Van Reusel, D.; Van den Bogaert, R.; Helewaut, B.; Steenhout, I.; Helewaut, H.; Damman, D.; et al. Legionella Spp. Colonization on Non-Passenger Ships Calling at Belgian Ports. Medical Sciences Forum 2022, 13, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proctor, C.R.; Rhoads, W.J.; Keane, T.; Salehi, M.; Hamilton, K.; Pieper, K.J.; Cwiertny, D.M.; Prévost, M.; Whelton, A.J. Considerations for Large Building Water Quality after Extended Stagnation. AWWA Water Sci 2020, 2, e1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papadakis, A.; Chochlakis, D.; Koufakis, E.; Carayanni, V.; Psaroulaki, A. Recreational Water Safety in Hotels: Lessons from the COVID-19 Pandemic and the Way Forward for a Safe Aquatic Environment. Tourism and Hospitality 2024, 5, 1167–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhoads, W.J.; Hammes, F. Growth of Legionella during COVID-19 Lockdown Stagnation. Environ. Sci.: Water Res. Technol. 2021, 7, 10–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunz, J.M.; Hannapel, E.; Vander Kelen, P.; Hils, J.; Hoover, E.R.; Edens, C. Effects of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Legionella Water Management Program Performance across a United States Lodging Organization. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2023, 20, 6885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Water Safety Plan Manual: Step-by-Step Risk Management for Drinking-Water Suppliers, Second Edition. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240067691 (accessed on 6 June 2025).

- Water Safety Planning: A Roadmap to Supporting Resources. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/water-safety-planning-a-roadmap-to-supporting-resources (accessed on 6 June 2025).

- Borella, P.; Bargellini, A.; Marchegiano, P.; Vecchi, E.; Marchesi, I. Hospital-Acquired Legionella Infections: An Update on the Procedures for Controlling Environmental Contamination. Ann Ig 2016, 28, 98–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mentula, S.; Kääriäinen, S.; Jaakola, S.; Niittynen, M.; Airaksinen, P.; Koivula, I.; Lehtola, M.; Mauranen, E.; Mononen, I.; Savolainen, R.; et al. Tap Water as the Source of a Legionnaires’ Disease Outbreak Spread to Several Residential Buildings and One Hospital, Finland, 2020 to 2021. Euro Surveill 2023, 28, 2200673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donohue, M.J.; O’Connell, K.; Vesper, S.J.; Mistry, J.H.; King, D.; Kostich, M.; Pfaller, S. Widespread Molecular Detection of Legionella Pneumophila Serogroup 1 in Cold Water Taps across the United States. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2014, 48, 3145–3152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchesi, I.; Ferranti, G.; Mansi, A.; Marcelloni, A.M.; Proietto, A.R.; Saini, N.; Borella, P.; Bargellini, A. Control of Legionella Contamination and Risk of Corrosion in Hospital Water Networks Following Various Disinfection Procedures. Appl Environ Microbiol 2016, 82, 2959–2965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Technical Guidelines for the Prevention, Control and Investigation of Infections Caused by Legionella Species. Available online: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications-data/european-technical-guidelines-prevention-control-and-investigation-infections (accessed on 6 June 2025).

- ISO 5667-1:2020. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/72369.html (accessed on 6 June 2025).

- ISO 5667-1:2023. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/84099.html (accessed on 6 June 2025).

- ISO 11731:2017. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/61782.html (accessed on 6 June 2025).

- Schoonjans, F. MedCalc’s Relative Risk Calculator. Available online: https://www.medcalc.org/calc/relative_risk.php (accessed on 9 June 2025).

- IBM SPSS Statistics. Available online: https://www.ibm.com/products/spss-statistics?lot=5&mhsrc=ibmsearch_a&mhq=spss (accessed on 9 June 2025).

- Epi InfoTM | CDC. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/epiinfo/index.html (accessed on 9 June 2025).

- Buse, H.Y.; Schoen, M.E.; Ashbolt, N.J. Legionellae in Engineered Systems and Use of Quantitative Microbial Risk Assessment to Predict Exposure. Water Res 2012, 46, 921–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Legionella Diversity and Spatiotemporal Variation in the Occurrence of Opportunistic Pathogens within a Large Building Water System. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/2076-0817/9/7/567 (accessed on 5 June 2025).

- Hamilton, K.A.; Hamilton, M.T.; Johnson, W.; Jjemba, P.; Bukhari, Z.; LeChevallier, M.; Haas, C.N. Health Risks from Exposure to Legionella in Reclaimed Water Aerosols: Toilet Flushing, Spray Irrigation, and Cooling Towers. Water Research 2018, 134, 261–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Directive - 2020/2184 - EN - EUR-Lex. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/dir/2020/2184/oj/eng (accessed on 5 June 2025).

- Molina, J.J.; Bennassar, M.; Palacio, E.; Crespi, S. Impact of Prolonged Hotel Closures during the COVID-19 Pandemic on Legionella Infection Risks. Front Microbiol 2023, 14, 1136668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buchholz, U.; Brodhun, B.; Lehfeld, A.-S. Incidence of Legionnaires’ Disease among Travelers Visiting Hotels in Germany, 2015–2019. Emerging Infectious Diseases 2024, 30, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes-Phillips, D.; Bentham, R.; Ross, K.; Whiley, H. Factors Influencing Legionella Contamination of Domestic Household Showers. Pathogens 2019, 8, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buse, H.Y.; Morris, B.J.; Gomez-Alvarez, V.; Szabo, J.G.; Hall, J.S. Legionella Diversity and Spatiotemporal Variation in the Occurrence of Opportunistic Pathogens within a Large Building Water System. Pathogens 2020, 9, 567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincenti, S.; Nurchis, M.C.; Boninti, F.; Sapienza, M.; Raponi, M.; Pattavina, F.; Pesaro, C.; D’Alonzo, C.; Damiani, G.; Laurenti, P. An Innovative Device for the Hot Water Circuit in Hospitals to Save Energy Without Compromising the Safety and Quality of Water: Preliminary Results. Water 2025, 17, 692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romano Spica, V.; Borella, P.; Bruno, A.; Carboni, C.; Exner, M.; Hartemann, P.; Gianfranceschi, G.; Laganà, P.; Mansi, A.; Montagna, M.T.; et al. Legionnaires’ Disease Surveillance and Public Health Policies in Italy: A Mathematical Model for Assessing Prevention Strategies. Water 2024, 16, 2167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leoni, E.; Catalani, F.; Marini, S.; Dallolio, L. Legionellosis Associated with Recreational Waters: A Systematic Review of Cases and Outbreaks in Swimming Pools, Spa Pools, and Similar Environments. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2018, 15, 1612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anagnostopoulos, L.; Kourentis, L.; Papadakis, A.; Mouchtouri, V.A. Re-Starting the Cruise Sector during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Greece: Assessing Effectiveness of Port Contingency Planning. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2022, 19, 13262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Legionnaires’ Disease Surveillance Network (ELDSNet) - Operating Procedures. Available online: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications-data/european-legionnaires-disease-surveillance-network-eldsnet-operating-procedures (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- Yao, X.H.; Shen, F.; Hao, J.; Huang, L.; Keng, B. A Review of Legionella Transmission Risk in Built Environments: Sources, Regulations, Sampling, and Detection. Front. Public Health 2024, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- CDC Legionella (Legionnaires’ Disease and Pontiac Fever). Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/Legionella/index.html (accessed on 9 June 2025).

- Legionellosis (Legionnaires’ Disease). Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/questions-and-answers/item/legionellosis-legionnaires-disease (accessed on 9 June 2025).

- Legionellosis. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/legionellosis (accessed on 6 June 2025).

- Legionnaires’ Disease. Available online: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/legionnaires-disease (accessed on 6 June 2025).

- Vatansever, C.; Turetgen, I. Investigation of the Effects of Various Stress Factors on Biofilms and Planktonic Bacteria in Cooling Tower Model System. Arch Microbiol 2021, 203, 1411–1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rhoads, W.J.; Hammes, F. Growth of Legionella during COVID-19 Lockdown Stagnation. Environ. Sci.: Water Res. Technol. 2021, 7, 10–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, R.L.; Harrison, K.; Proctor, C.R.; Martin, A.; Williams, K.; Pruden, A.; Edwards, M.A. Chlorine Disinfection of Legionella Spp., L. pneumophila, and Acanthamoeba under Warm Water Premise Plumbing Conditions. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leaflet for Managers of Tourist Accommodation on How to Reduce the Risk of Legionnaires’ Disease. Available online: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications-data/leaflet-managers-tourist-accommodation-how-reduce-risk-legionnaires-disease (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- Directive - 2020/2184 - EN - EUR-Lex. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/dir/2020/2184/oj/eng (accessed on 10 June 2025).

| Facilities | Frequency | Percent | Cum. Percent | Wilson 95% LCL | Wilson 95% UCL |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Public Hospitals | 440 | 40.70% | 100.00% | 37.81% | 43.66% |

| Hotels | 239 | 22.11% | 22.11% | 19.74% | 24.68% |

| Passenger ships | 176 | 16.28% | 38.39% | 14.20% | 18.60% |

| Primary Health care units | 114 | 10.55% | 48.94% | 8.85% | 12.52% |

| Private Clinics | 112 | 10.36% | 59.30% | 8.68% | 12.32% |

| Total | 1081 | 100.00% | 100.00% |

| Sampling description | Frequency | Percent | Cum. Percent | Wilson 95% LCL | Wilson 95% UCL |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Close point | 66 | 40.74% | 40.74% | 33.10% | 48.73% |

| Far point | 96 | 59.26% | 100.00% | 51.27% | 66.90% |

| Direct | 600 | 57.92% | 57.92% | 54.88% | 60.89% |

| Indirect | 436 | 42.08% | 100.00% | 39.11% | 45.12% |

| Cold water | 600 | 55.50% | 55.50% | 52.53% | 58.44% |

| Hot water | 481 | 44,50% | 100,00% | 41,56% | 47,47% |

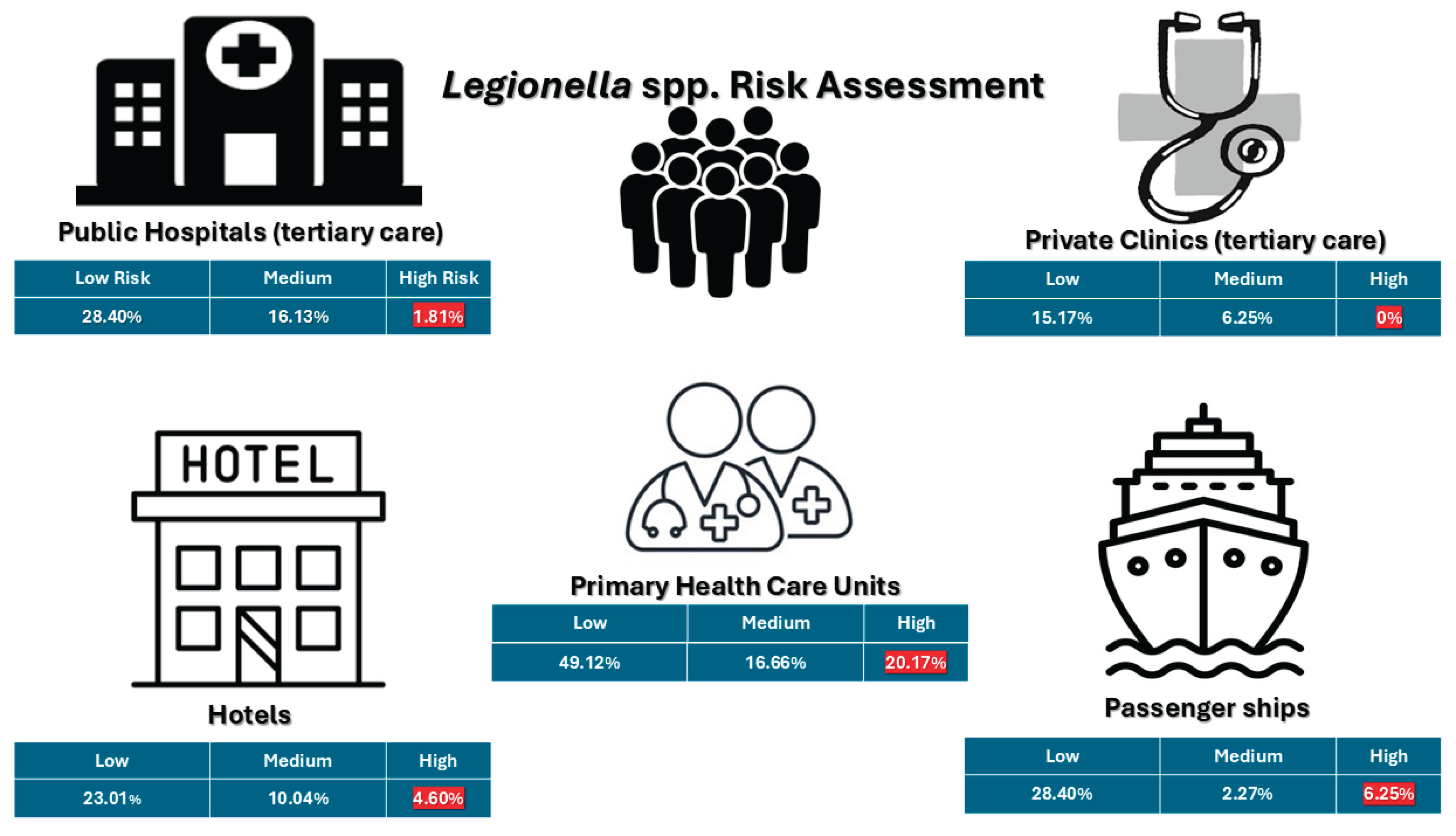

| Facility | Number of samples | <103 cfu/L | >=103 and <104 cfu/L | >=104 cfu/L | Total positive samples (>50 cfu/L) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Public Hospitals (tertiary-level care) | 440 | 125 (28.40%) | 71 (16.13%) | 8 (1.81%) | 204 (46.36%) |

| Private Clinics | 112 | 17 (15.17%) | 7 (6.25%) | 0 | 24 (21.42%) |

| Primary Health Care | 114 | 56 (49.12%) | 19 (16.66%) | 23 (20.17%) | 98 (85.96%) |

| Hotels | 239 | 55 (23.01%) | 24 (10.04%) | 11 (4.60%) | 91 (38.08%) |

| Passenger ship | 176 | 50 (28.40%) | 4 (2.27%) | 11 (6.25%) | 65 (36.93%) |

| Total | 1081 | 303 (28.03%) | 125 (11.56%) | 53 (4.90%) | 482 (44.59%) |

| Sample Type | Number of Samples (n) | Positive Samples (n, percentage) |

|---|---|---|

| Hot water (total) | 481 | 252 (52.28%) |

| └─ Direct outlet | 258 | 131 (50.71%) |

| └─ Indirect outlet | 206 | 103 (50%) |

| └─ Far away point | 50 | 24 (48%) |

| └─ Close point | 32 | 11 (34.37%) |

| Cold water (total) | 600 | 230 (47.72%) |

| └─ Direct outlet | 342 | 134 (39.18%) |

| └─ Indirect outlet | 230 | 83 (36.08%) |

| └─ Far away point | 46 | 12 (23.80%) |

| └─ Close point | 34 | 11 (28%) |

| Facility | Total Positive Samples (n, %) | L. pneumophila SG1 (n, %) | L. pneumophila SG2–15 (n, %) | Other Legionella spp. (n, %) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hotels | 91 (18.88%) | 27 (5.60%) | 66 (13.69%) | 6 (1.24%) |

| Passenger ships | 65 (13.49%) | 24 (4.5%) | 41 (8.50%) | 0 (0.00%) |

| Primary Health Care | 98 (20.33%) | 21 (12.07%) | 80 (16.60%) | 0 (0.00%) |

| Private Clinics | 24 (4.98%) | 7 (1.45%) | 17 (3.53%) | 0 (0.00%) |

| Public Hospitals | 204 (42.32%) | 95 (19.70%) | 111 (23.03%) | 7 (1.45%) |

| Total | 482 (44.59%) | 174 (36.09%) | 315 (65.35%) | 13 (2.70%) |

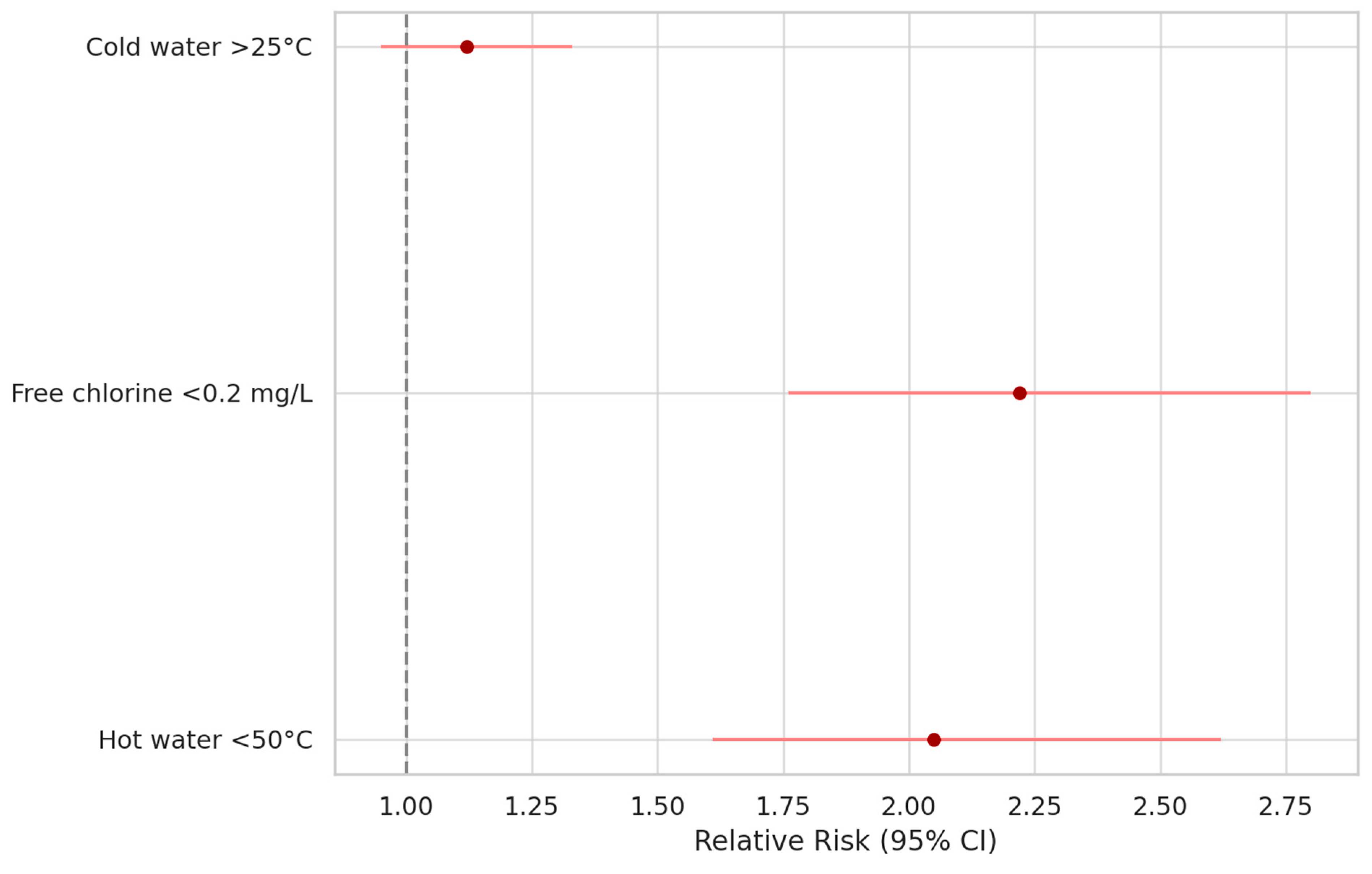

| Risk Factor | Odds Ratio (Cross Product) | Odds Ratio (MLE) | Risk Ratio (RR) | Risk Difference (RD%) | p-V |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Free residual chlorine < 0.2 mg/L | 2.2213 | 2.2175 | 2.2175 | 18.6545 | <0.0001 |

| Cold water temperature > 25 °C | 1.2380 | 1.2375 | 1.1252 | 5.2736 | 0.1 |

| Hot water temperature < 50 °C | 6.5394 | 6.5073 | 2.054 | 41.5504 | <0.0001 |

| Hot water temperature < 35 °C | 4.7365 | 4.7202 | 3.5792 | 22.3196 | <0.0001 |

| Turbidity (non-compliant) | 2.5662 | 2.5639 | 2.5313 | 1.3503 | 0.04 |

| Direct water sample (vs. outlet) | 0.9341 | 0.9342 | 0.9610 | -1.6562 | 0.29 |

| Sampling at distal (far) outlet point | 1.3534 | 1.3504 | 1.1124 | 6.8915 | 0.22 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).