1. Introduction

Thyroid carcinoma (TC) is the most prevalent endocrine malignancy accounting for approximately 568,000 new cases and over 44,000 deaths worldwide, according to GLOBOCAN. The global incidence rate for TC is three times higher in women than in men [

1]. The incidence of TC has increased markedly in recent decades, largely due to widespread use of sensitive imaging techniques, which have led to enhanced detection of asymptomatic and small tumors [

2,

3] Differentiated thyroid cancer (DTC), which arises from the follicular cells within the thyroid glands, is the most common subtype of TC. It accounts for approximately 90-95% of all TC and includes the papillary (PTC), follicular (FTC) and oncocytic (also known as Hürthle) [

2,

3]. Surgery is curative in most cases of well-differentiated TC and radioactive iodine (RAI) treatment after surgery improves overall survival in patients with high risk [

2]. However, a subset of patients develops progressive disease that becomes refractory to RAI therapy. In this case, the multi-kinase inhibitor lenvatinib has been approved. Although lenvatinib exhibits favourable anti-tumor activity and extends progression-free survival, progressive disease is common. In addition, severe adverse effects frequently occur, often necessitating dose reductions or treatment breaks [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8]. Given the limitations of current therapies, there is a need for novel, more efficient and better-tolerated treatment options for DTC patients.

There is growing evidence that changes in mitochondrial metabolism play a crucial role in the development and progression of various tumor entities. Mitochondrial reprogramming has been linked to uncontrolled cell proliferation, as cancer cells require more energy and building blocks than healthy cells [

9]. Additionally, increased mitochondrial activity and oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) have been associated with resistance to therapies like tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) [

10,

11]. Therefore, targeting mitochondrial function is considered a promising approach to overcome therapy resistance.

The endosymbiotic hypothesis suggests that mitochondria originated from ancestral bacteria. Therefore, several antibiotics affect these organelles by targeting mitochondrial components. Certain antibiotics, particularly tetracyclines, have been shown to disrupt mitochondrial function by inhibiting mitochondrial biogenesis and increasing reactive oxygen species (ROS) levels, leading to metabolic stress and anti-proliferative or pro-apoptotic effects [

12,

13,

14]. Tigecycline, a representative of the tetracycline class, has demonstrated anti-cancer properties across various tumor entities by impairing cell proliferation, disrupting aerobic metabolism, inducing mitochondrial dysfunction and cell cycle arrest, and sensitizing cancer cells to chemotherapeutic agents [

13,

14]. Eravacycline, another synthetic tetracycline analogue, has been associated with a better toxicity profile compared to tigecycline, particularly regarding gastrointestinal side effects. Although its anti-cancer effect has not yet been investigated, the mitochondrial targeting potential and improved tolerability makes it an interesting candidate for combinational approaches in cancer therapy [

15,

16].

Combination therapies have gained increasing interest in oncology due to their potential to enhance therapeutic efficacy, overcome resistance and reduce drug-related adverse events by lowering the required doses. Given the limited efficacy of lenvatinib in advanced TC, novel treatment strategies are urgently needed [

17]. Considering the role of mitochondria in tumor progression and drug resistance, we hypothesized that combining lenvatinib with mitochondrial targeting antibiotics such as tigecycline or eravacycline could potentiate anti-tumor effects and overcome presumed resistance mechanisms in DTC.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cell Lines

K1, TPC-1, FTC-133 and Nthy-Ori 3.1 cells were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (Missouri, USA), whereas TT2609-C02 cells were purchased from the German Collection of Microorganisms and Cell Cultures GmbH (DSMZ, Braunschweig, Germany). For the cultivation of K1 and FTC-133, DMEM w/o L-glutamine (Sigma-Aldrich, Missouri, USA) was used. For K1, media was supplemented with Ham’s F12 (Sigmal-Aldrich, Missouri, USA), MCDB 105 (Sigma-Aldrich, Missouri, USA), 2 mM L-glutamine (PAN Biotech GmbH, Aidenbach, Germany), 10% FCS (Sigma-Aldrich, Missouri, USA) and 1% Penicillin/Streptomycin (Pen/Strep, PAN Biotech GmbH, Aidenbach, USA). For FTC-133, DMEM was supplemented with Ham’s F12, 2 mM L-glutamine, 10% FCS and 1% Pen/Strep. TPC-1 and TT2609-C02 were cultivated in RPMI 1640 (PAN Biotech GmbH, Aidenbach, Germany). For TPC-1 cells, 10% FCS and 1% Pen/Strep was added, whereas for TT2609-C02 20% FCS, 1% Pen/Strep and 0.1% insulin-transferrin-selenite were supplemented. Nthy-Ori 3.1 were cultured in RPMI 1640 with sodium bicarbonate, supplemented with 2 mM L-glutamine, 10% FCS and 1% Pen/Strep. All cells were cultivated at 37°C with 5% CO2 and constant humidity. Before cell seeding, all culture flasks and multi-well plates (except for the Seahorse experiments) were coated with collagen G (0.001% in PBS, Sigma-Aldrich, Missouri, USA).

2.2. Compounds

Lenvatinib and tigecycline were obtained from Selleckchem (Houston, USA), whereas Eravacycline dihydrochloride was purchased from THP Medical Products (Vienna, Austria).

2.3. Cell Viability

Cell viability was determined using the Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK8, Sigma-Aldrich, Missouri, USA). Cells were seeded in triplicates into a 96-well plate, stimulated 24 hours after seeding and incubated for 72 hours. For measurement, 5 µl of CCK8 reagent were added to each well containing 50 µl culture medium. After an incubation time of 2 hours, the metabolic activity was quantified via absorbance measurement at 450 nm on a Tecan Spark plate reader (Tecan, Grödig, Austria). Absorbance values were normalized to the mean absorbance of the untreated control (UTC). For IC50 determination, the equation log(agonist) vs. response – Variable slope (four parameters) in GraphPad prism 10.2.3 was used.

2.4. 3D Cell Culture Model

Cell viability of 3D spheroids was investigated using the CellTiter-Glo® 3D Cell Viability assay (CTG) from Promega (Wisconsin, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Cells were seeded in triplicates into a low-attachment 96-well U-bottom plate, centrifuged for 10 min at 350 g, stimulated 72 hours after seeding and incubated for 96 hours. For measurement, cells were equilibrated 30 min at RT, and 100 µl of CTG were added to each well containing 100 µl culture medium. The plate was shaken for 5 min at 450 rpm and further incubated for 25 min at RT in the dark. For quantification of the luminescence signal, the supernatant was transferred to a white 96-well plate and luminescence was recorded with an integration time of 10 ms on a Tecan Spark plate reader. Before CTG measurement, spheroid pictures were taken using an Olympus CKX53SF microscope (Vienna, Austria). Control values were set to 100%, whereas treated samples were normalized to the UTC.

2.5. Clonogenic Assay

For evaluation of long-term cell survival, cells were seeded into 6-well plates and treated with the respective compounds for 24 hours. After incubation, cells were trypsinized and re-seeded at a density of 5 x 103 cells per well into a 6-well plate. After incubation for 5 days, attached cells were stained with crystal violet solution for 10 min at RT. After taking pictures with the ChemiDoc Imaging System of Bio-Rad (Hercules, USA), the dye was released by adding 500 µl SDS/EtOH dissolving buffer per well. Absorbance at 550 nm was measured with the Tecan Spark plate reader (Grödig, Austria). The mean value of the UTC was set to 100%. Samples were normalized to the UTC.

2.6. Caspase 3/7 Activity

For evaluation of apoptosis, the Promega Caspase-Glo® 3/7 Assay System was used. Briefly, cells were seeded in 96-well plates and stimulated 24 hours after seeding with mono- or combination therapy for 24, 48 and 72 hours. After an equilibration time of 20 min at RT, caspase substrate was added in a 1:1 ratio to each well and the plate was shaken for 2 min. After 30 min at RT, the luminescence signal was measured on a Tecan Spark plate reader, with an integration time of 10 ms. For normalization, the control mean was set to 1 and the treated samples were normalized to the UTC.

2.7. ATP Assay

For verification of the metabolic cell viability data, the Promega CellTiter-Glo® Cell Viability Assay was performed. Therefore, cells were seeded in 96-well plates, incubated 24 hours and stimulated for 24, 48 and 72 hours. CellTiter-Glo® Reagent was added to the cells according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Luminescence signal was recorded on a Tecan Spark plater reader with an integration time of 10 ms. Luminescence values were normalized to the mean luminescence signal of the UTC.

2.8. JC-10

For determination of the mitochondrial membrane potential, the mitochondrial membrane potential kit (JC-10) from Sigma-Aldrich (Missouri, USA) was used according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, cells were seeded, grown overnight and stimulated with mono- or combination therapy for 72 hours. JC-10 dye was diluted 1:100 in assay buffer A and 25 µl were pipetted into each well. After incubating for 60 min at 37°C in the dark, 25 µl/well of assay buffer B were added. Green fluorescence intensity was recorded at an excitation (ex) wavelength of 490 nm and an emission (em) wavelength of 525 nm. Red fluorescence was measured at ex = 540 nm and em = 590 nm with a Tecan Spark plate reader (Grödig, Austria). For calculation of the mitochondrial membrane potential, the following formula was used: (red fluorescence)/(green fluorescence). The mean control values were set to 100% and the treatments were normalized to the control.

2.9. Live Cell Imaging

Mitochondrial morphology was assessed using the MitoTracker Green FM from Invitrogen (Massachusetts, USA). Cells were seeded in ibidi-µslides (Ibidi GmbH, Martinsried, Germany) and grown overnight. After 72 hours of mono- and combination therapeutic stimulation, respectively, cells were washed with PBS and incubated at 37°C, protected from light, for 30 min with 200 µl/well MitoTracker Green FM (1:5,000). After another washing step with PBS, 200 µl/well of Hoechst 33342 (1:12,300, Thermo Scientific, Massachusetts, USA) were added per well. Cells were incubated for 5 min at RT in the dark, washed once with PBS, and 200 µl/well culture medium were pipetted into the slides. Images were obtained using a Zeiss LSM700 confocal microscope (Oberkochen, Germany) and image analysis was performed with the Zeiss Zen software.

2.10. Western Blot

Proteins were separated via SDS-PAGE, transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane and incubated with a primary antibody diluted in either 5% of BSA or 5% of milk powder in TBS-T overnight at 4°C: caspase 7 (1:1,000, 35,20 kDa), Bcl-xl (1:1,000, 30 kDa), Mcl-1 (1:1,000, 40 kDa), Bcl-2 (1:1,000, 28 kDa), PARP (1:1000, 116,89 kDa) and cleaved PARP (1:1,000, 89 kDa). Proteins were visualized using horseradish peroxidase (HRP) coupled secondary antibodies and ECL solution containing luminol. The following secondary antibodies diluted in 5% of BSA or milk powder in TBS-T were incubated with the membrane for 1 hour at RT: anti-rabbit IgG, HRP-linked and anti-mouse IgG, HRP-linked antibody (1:2,000) from Cell Signaling (Massachusetts, USA). Chemiluminescence was detected with the ChemiDoc Touch Imaging System (Bio-Rad, Munich, Germany) and the protein expression was quantified using stain-free technology and the Image Lab Software. For all quantifications, the protein expression was normalized to the respective protein load and to the mean control values.

2.11. Bioenergetic Measurements

For the metabolic characterization of DTC and non-tumorigenic cell lines, cells were seeded in XFe96/XF Pro cell culture microplates (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, US) with following densities: 10,000 (K1, TPC-1 and Nthy-Ori 3.1), 7,500 (FTC-133) and 15,000 (TT2609-C02) cells/well 24 hours prior to the analysis. For drug treatment determination, K1 cells were seeded at a density of 7,500 cells/well, incubated for 24 hours and treated with the drugs for 12 hours. On the day of the assay, cells were washed once and 180 µl/well assay medium (Seahorse XF RPMI) supplemented with 10 mM glucose, 1 mM sodium pyruvate and 2 mM glutamine were added. Cells were then incubated for 1 hour at 37°C in a non-CO2 incubator. For the XF Cell Mito Stress Test, basal oxygen consumption rates (OCR) were measured, followed by sequential injections of the ATP synthase inhibitor oligomycin (2.5 µM; port A), the uncoupling agent fluoro-carbonyl cyanide phenylhydrazone (FCCP, 1 µM; port B), and a combination of the complex I inhibitor rotenone (0.5 µM; port C) and the complex III inhibitor antimycin A (0.5 µM; port C) along with the nuclear stain Hoechst 33342 (2 µM; port C). For the XF Glycolytic Rate Assay, basal extracellular acidification rates (ECAR) were initially measured, followed by sequential injections of the rotenone (0.5 µM; port A) in combination with antimycin A (0.5 µM; port A), the hexokinase inhibitor 2-deoxy-D-glucose (2-DG, 50 mM; port B), and the nuclear stain Hoechst 33342 (2 µM; port C). After calibration of the Seahorse XFe96 Analyzer, the assay was performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions. For data normalization, measurements were normalized based on quantified cell numbers. Briefly, nuclei fluorescence images were acquired using the BioTek Lionheart FX Automated Microscope and cell counts were determined with the BioTek Gen5 Software. Data analysis was conducted using Wave software (version 2.6.4) and Seahorse Analytics (Agilent Technologies).

2.12. Statistics

All experiments described were conducted at least three times. The data are presented as mean ± SEM and were statistically evaluated using GraphPad Prism 10.2.3. Statistically relevant differences between the UTC and the treated samples were determined using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA).

2.13. Assessment of Additive Effects and Synergism

To evaluate potential synergistic effects of combination treatments, an additive reference value was calculated based on the mean effects of the respective monotherapies. Specifically, the expected additive effect (EA) was defined as:

This value represents the theoretical additive effect [

18]. The measured effect of the combination therapy was then compared to this calculated threshold. If the observed combination effect exceeded the EA value, the effect was considered synergistic. To facilitate visual interpretation, the EA was indicated as a red line in the respective figures.

4. Discussion

Efficacious treatment options for radioiodine-refractory differentiated thyroid cancer (RR-DTC) remain limited, and disease progression is often inevitable. Although lenvatinib is currently the first-line treatment for RR-DTC, its clinical use is accompanied by severe side effects due to the high dosage required. Moreover, the development of resistance represents a major therapeutic challenge [

4,

5,

6,

7]. These aspects underscore the urgent need to develop novel therapeutic strategies to enhance treatment efficacy and improve both, prognosis and quality of life for patients.

In this context, metabolic reprogramming, one of the hallmarks of cancers, has gained attention due to its critical role in tumorigenesis. Beyond their role in energy production, mitochondria are involved in various cellular processes, including apoptosis, metabolic adaptation and cell cycle regulation [

24]. In tumors, the functions of mitochondria are often dysregulated and there is evidence that altered mitochondria might be one regulator of therapy resistance making them attractive targets for therapeutic intervention [

10,

11,

25]. Therefore, the aim of the present study was to investigate whether the combination of lenvatinib with mitochondria-targeting antibiotics could enhance treatment efficacy in DTC cells. Interestingly, although lenvatinib is the first-line treatment for RR-DTC, we observed a heterogeneous sensitivity profile across DTC cell lines, whereby two cell lines showed no response to lenvatinib. This lack of response in some DTC cell lines mirrors clinical observations, where a proportion of patients fails to benefit from lenvatinib treatment [

5]. Our data align with previously reported variability in lenvatinib response across thyroid cancer models, where only two out of 11 cell lines exhibited a significant sensitivity to the drug, whereas in xenograft models, lenvatinib showed better anti-tumor effects [

26]. Therefore, our data supports the need to enhance treatment efficacy, particularly in resistant cells.

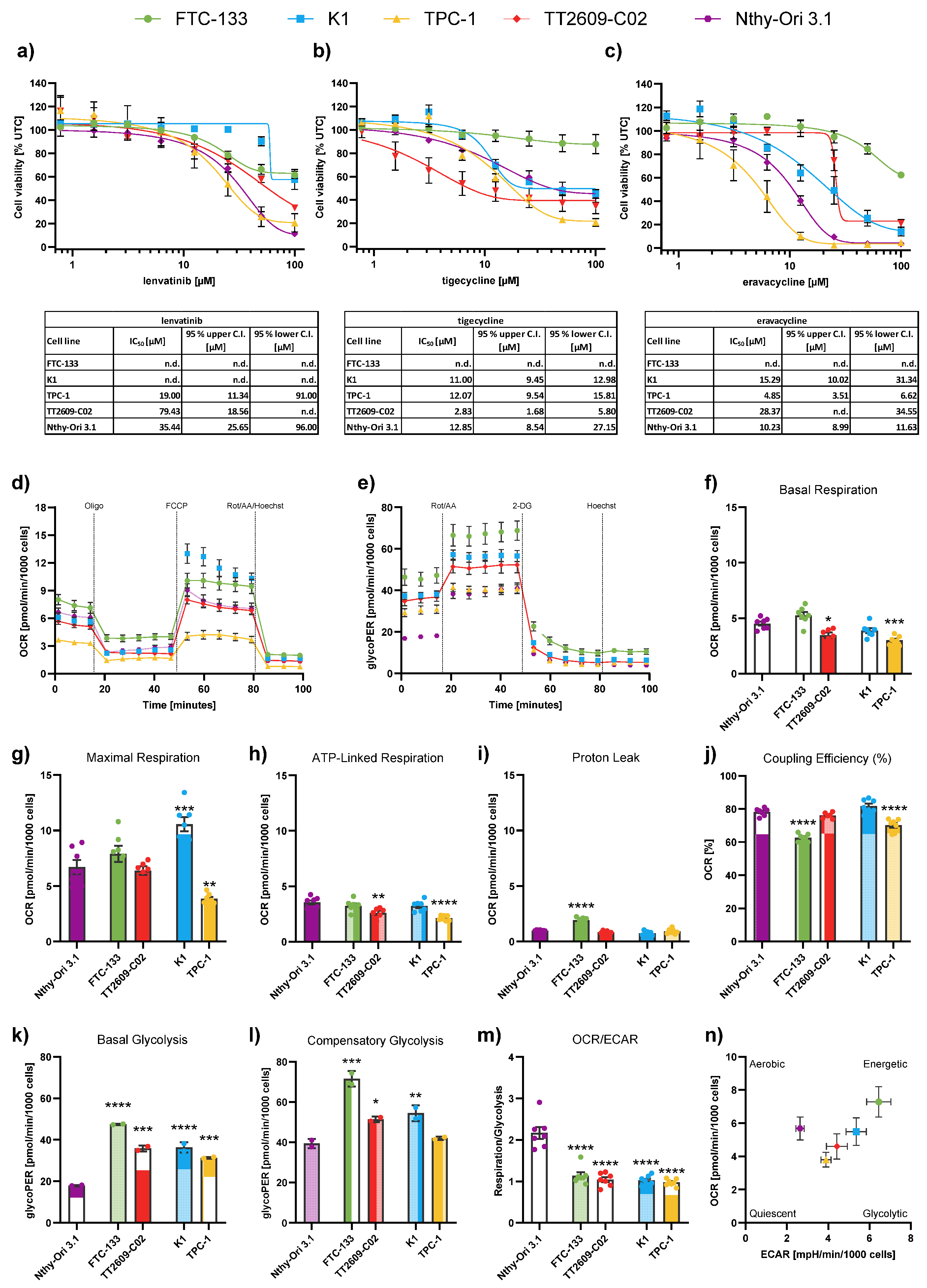

Given the increasing interest in targeting mitochondria, we investigated two different tetracyclines in their ability to inhibit cell proliferation. Tigecycline, a known inhibitor of mitochondrial translation, has been previously shown to have anti-proliferative effects in various tumor entities, including sorafenib-resistant hepatocellular carcinoma cells [

25]. Alongside tigecycline, we also tested eravacycline, a newer member of the tetracycline class of antibiotics with improved pharmacokinetic properties and structural modifications that may enhance mitochondrial targeting [

27]. Both antibiotics exhibited a concentration-dependent reduction in cell viability across all cell lines tested. Previous studies show that the main effects of tigecycline on cancer cells are the inhibition of cell proliferation and mitochondrial function, whereby the IC

50 on cancer cells range from 5.8 to 51.4 µM in diverse tumor entities [

14]. Although data on eravacycline in cancer is still emerging, it is described that eravacycline significantly inhibited cancer cell proliferation in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma [

28] and melanoma cells [

29]. The study by Liu et al. demonstrates, that eravacycline inhibited tumor proliferation in melanoma cells with IC

50 values of 1.48 µM to 6.47 µM. Interestingly, eravacycline exhibited higher IC

50 values compared to tigecycline in our DTC cell lines, which might be explainable by the structural differences of the drugs [

30]. Another study by Aminzadeh-Gohari et al. compared the effect of different antibiotics on the cell viability of melanoma cells, and similar to our data, they showed that tigecycline had a stronger anti-proliferative effect than doxycycline and azithromycin [

13]. However, eravacycline generally shows a less adverse effect profile with better individual patient tolerability.

Since some of the DTC cell lines showed only limited sensitivity to either lenvatinib or the antibiotics, and mitochondria are known to contribute to therapy resistance, we further assessed the metabolic characteristics of the follicular and papillary DTC cell lines. In FTC-133, we observed significantly increased proton leakage across the mitochondrial membrane and reduced mitochondrial coupling efficiency compared to Nthy-Ori 3.1, indicating impaired mitochondrial respiration. This dysfunction may explain why FTC-133 do not respond to tigecycline or eravacycline. Interestingly, our findings indicate that DTC cells do not follow a uniform mitochondrial phenotype, as most analyzed parameters showed only minor differences between malignant and non-malignant cells. Despite these minor differences, it remains possible that DTC cells are more dependent on mitochondrial function under stress. This assumption is supported by findings that thyroid cancer cells can shift between aerobic glycolysis and OXPHOS depending on the tumor microenvironment [

31]. Thus, targeting mitochondria with antibiotics may still represent a therapeutic strategy. In addition, it has to be mentioned that, to ensure comparability across cell lines, bioenergetic measurements were performed using a fixed FCCP concentration (1 µM). It might be possible that different cell lines require different FCCP concentrations to achieve maximal respiratory uncoupling.

In agreement with the Warburg effect, we showed that DTC cells possess elevated rates of glycolysis, while on the other hand non-malignant cells had a significantly higher OCR/ECAR ratio. This indicates that DTC cells exhibit an increased dependence on glucose metabolism through glycolysis, highlighting glucose metabolism as an attractive target for therapeutic strategies [

32].

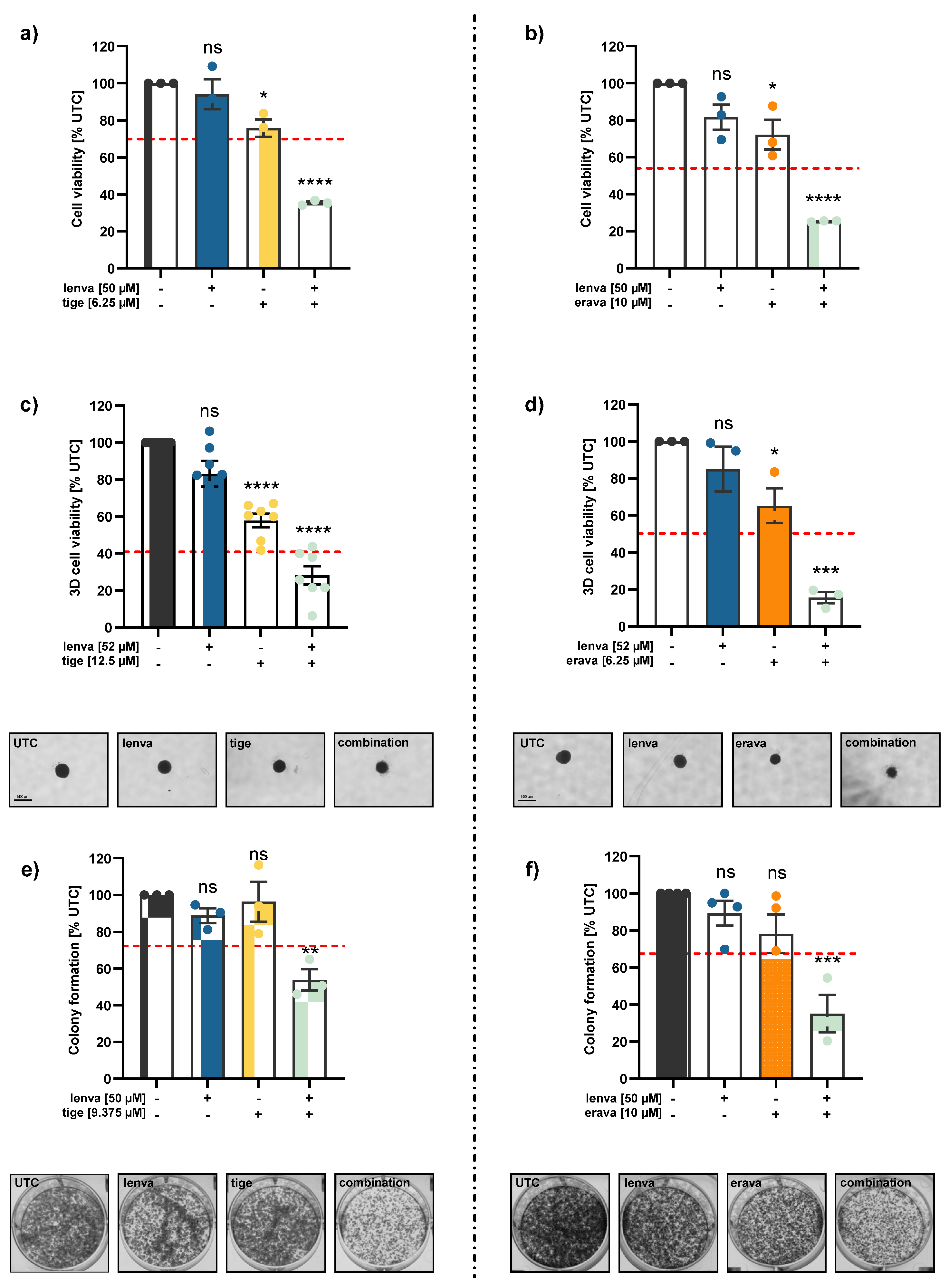

The main aspect of the present study was to elucidate whether combining lenvatinib with mitochondria-targeting antibiotics, such as tigecycline or eravacycline, could improve treatment efficacy in DTC cells. Indeed, our data show that both combinations – lenvatinib with tigecycline and lenvatinib with eravacycline – led to significantly reduced cell viability in 2D and 3D models compared to single treatments in lenvatinib-resistant K1 cells. Notably, in all cases, the combination treatments clearly exceeded the EA, indicating a synergistic effect rather than an additive one. Up to now, various preclinical studies have reported that tetracycline antibiotics can enhance sensitivity to chemotherapeutic drugs in various cancers [

33,

34,

35,

36]. A study by Wang et al. showed that combination of tigecycline and paclitaxel at sub-toxic concentrations significantly enhanced the efficacy of paclitaxel in DTC

in vitro and

in vivo [

37]. Therefore, our results highlight the potential of combinational treatments, especially with antibiotics, to overcome intrinsic resistance in DTC.

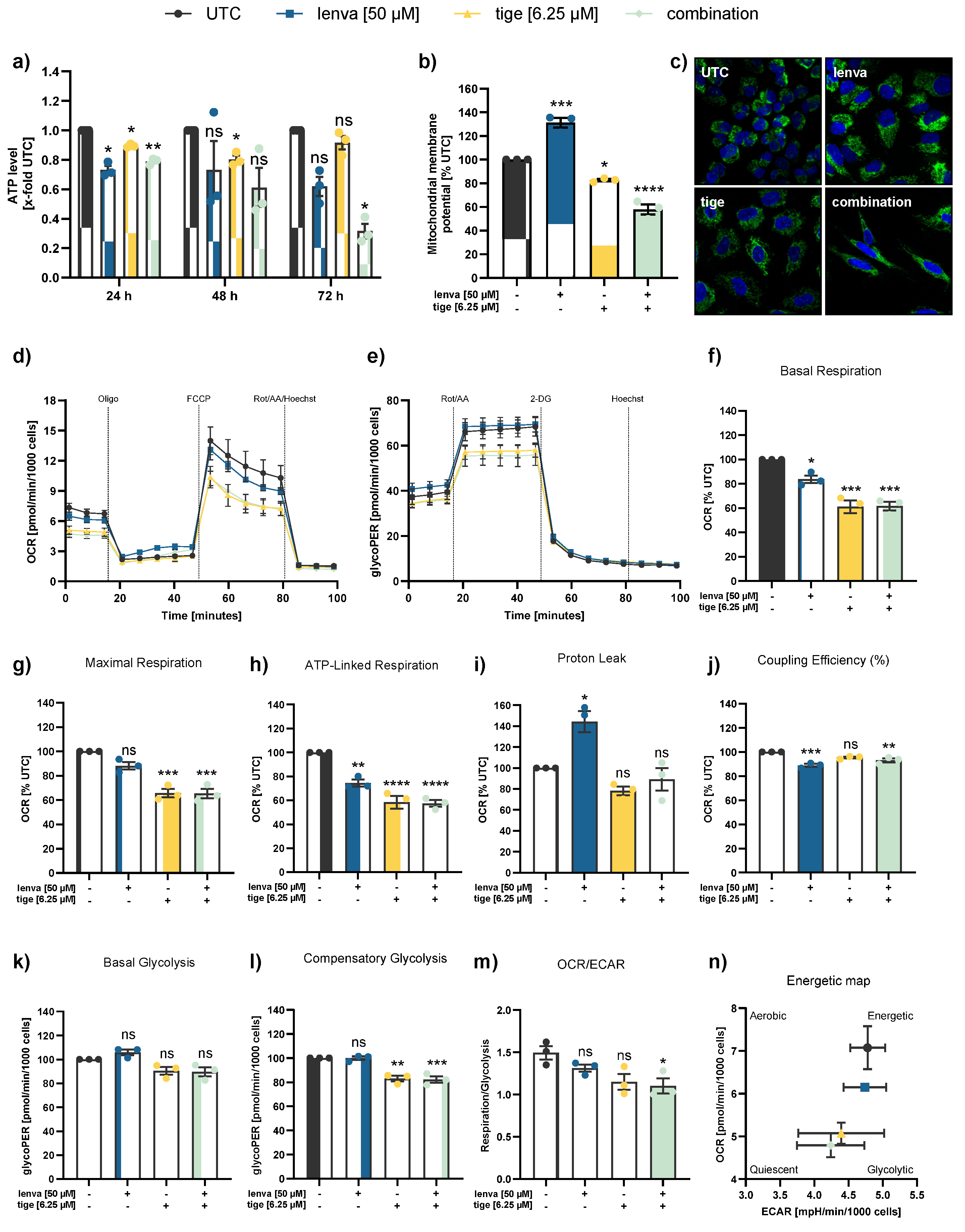

Although the anti-cancer activities of tigecycline have been demonstrated in various cancers, there is no unifying mechanism of action for tigecycline across different tumor types and despite its structural similarity to tigecycline, the mechanism by which eravacycline affects cancer cells is still poorly understood. However, the majority of studies suggest that mitochondria are the predominant target of tigecycline, either through downregulation of mitochondrial protein synthesis and respiratory-chain complexes or by reducing mitochondrial mass [

12,

14,

37,

38]. Our results display that combinational treatment exerts effects on both mitochondrial respiration and glycolysis after 12 hours of treatment, indicating a general impairment in mitochondrial ATP production. The reduced ATP production may be linked to the loss of mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP) observed upon treatment. Notably, the pronounced reduction in OCR and ATP production observed in the combination treatments is largely attributed to the antibiotics. This is in agreement with a previous study indicating that chemotherapeutic agents have minimal impact on mitochondrial respiration in thyroid cancer cells, whereas tigecycline significantly impairs mitochondrial function via decreasing the MMP and mitochondrial respiration [

37]. Liu et al. additionally reported that targeting mitochondria in multidrug-resistant tumors enhances the sensitivity of cells to chemotherapy, as mitochondrial targeting facilitated increased drug accumulation within resistant cancer cells [

39].

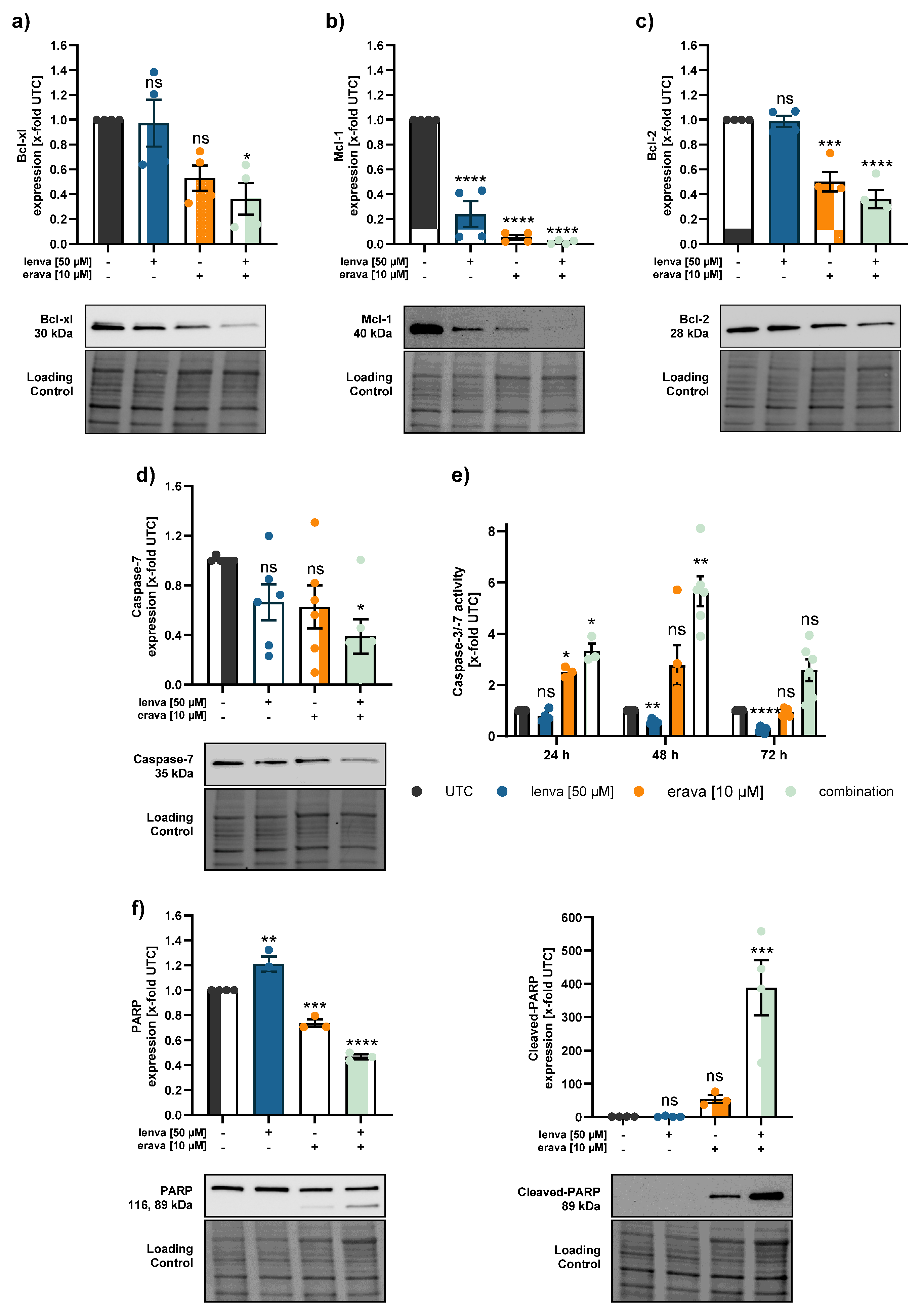

Since mitochondria play a pivotal role in the regulation of apoptosis, we investigated whether the observed reduction in cell viability was associated with apoptotic mechanisms. When anti-apoptotic proteins are less abundant and pro-apoptotic Bcl-2 family members are dominant, the mitochondrial outer membrane starts to permeabilize. Executioner caspases (like caspase-3 and -7) cleave various cellular substrates, including PARP, which is widely recognized as a hallmark of apoptosis [

23]. Our data show that members of the anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 family, including Bcl-xl, Mcl-1 and Bcl-2, were significantly downregulated following combinational treatment with lenvatinib and the respective antibiotics. In parallel, procaspase-7 protein levels were reduced, suggesting activation through cleavage, which was further supported by a significant increase in caspase-3/7 activity, particularly after 48 hours. While total-PARP levels remained largely unchanged, we observed a pronounced increase in cleaved-PARP, indicating the induction of apoptosis in response to the combination therapy. Our data is in line with other studies, which showed that the inhibition of mitochondria with tigecycline induced apoptosis via the intrinsic pathway, with activation of Bcl-2, release of cytochrome c, and cleavage of caspase-9/caspase-3/caspase-7 [

14,

40,

41].

In summary, our study highlights that combining lenvatinib with mitochondria-targeting antibiotics represents a promising strategy to overcome resistance in DTC by impairing mitochondrial function and promoting apoptotic cell death.

Our study not only provides a promising proof-of-concept for overcoming lenvatinib resistance in DTC through combination with antibiotics, but also offering interesting new research questions.

In vivo confirmation is required to validate the therapeutic potential and to evaluate how antibiotic treatment might alter the gut microbiota and potentially affect the efficacy of multikinase inhibitors. Therefore, clinical application may require careful evaluation of risks and consideration of co-administration of probiotics or prebiotics [

35]. Nonetheless, our findings represent an important step towards the development of more effective treatment strategies for RR-DTC.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.P., J.P., P.H.-C., and C.A.; methodology, C.A., P.H.-C., J.P., C.P., B.K. and D.D.W.; validation, C.A., P.H.-C., J.P., D.D.W. and B.K.; formal analysis, C.A. and S.P.; investigation, C.A., P.H.-C., S.P., M.G.-M., G.S. and D.D.W.; resources, J.P., C.P. and B.K.; data curation, C.A., S.P., P.H.-C., G.S. and D.D.W.; writing—original draft preparation, C.A. and P.H.-C.; writing—review and editing, C.A., P.H.-C., J.P., C.P., G.R., T.K., D.D.W., B.K., G.S., S.P. and M.G.-M.; visualization, C.A.; supervision, P.H.-C., J.P. and C.P.; project administration, P.H.-C.; funding acquisition, J.P., C.P., D.D.W., B.K., C.A. and P.H.-C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

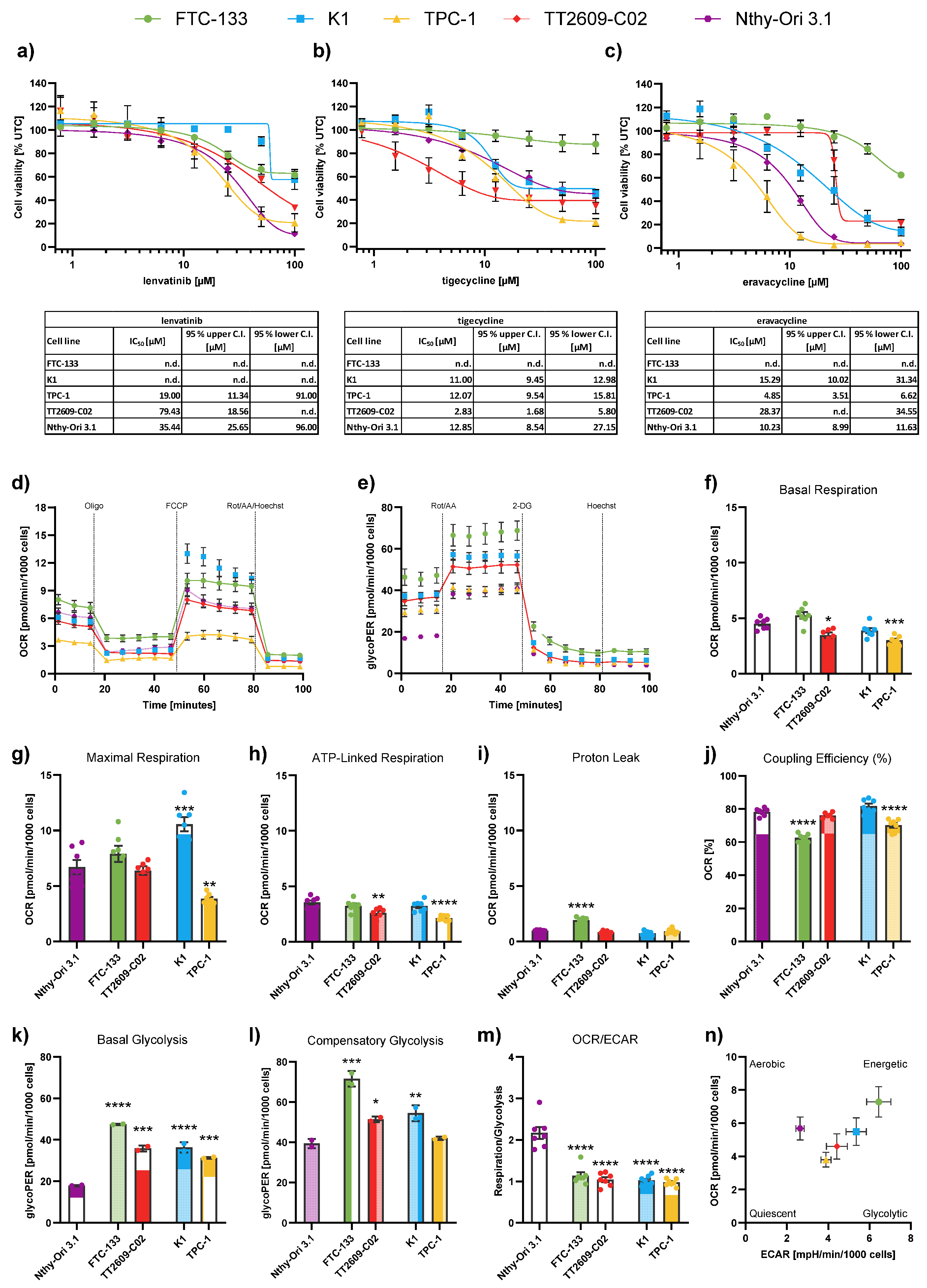

Figure 1.

Baseline drug response and metabolic characterization of differentiated thyroid cancer (DTC) and non-malignant thyroid cell lines. (a-c) Cell viability of four DTC cell lines and one non-malignant thyroid cell line (Nthy-Ori 3.1) following treatment with (a) lenvatinib, (b) tigecycline, and (c) eravacycline for 72 h. Line charts show viability curves normalized to untreated controls (% UTC). IC50 values were determined with log(agonist) vs. response – Variable slope (four parameters) including 95% upper and lower confidence intervals (C.I.). (d) Representative kinetic profile of the Mito Stress test using oligomycin (Oligo, 2.5 µM), the uncoupling agent fluoro-carbonyl cyanide phenylhydrazone (FCCP, 1 µM), and a combination of rotenone/antimycin A followed by Hoechst 33342 injection for normalization (Rot/AA/Hoechst, 0.5 µM, 0.5 µM and 2 µM, respectively). (e) Representative profile of the Glycolytic Rate assay with injections of Rot/AA (0.5 µM each), 2-deoxyglucose (2-DG, 50 mM) and Hoechst (2 µM). (f-m) Quantification of key metabolic parameters from Seahorse analysis: (f) basal respiration, (g) maximal respiration, (h) ATP-linked respiration, (i) proton leak, (j) coupling efficiency, (k) basal glycolysis, (l) compensatory glycolysis, and (m) OCR/ECAR ratios. (n) Energy map visualizing metabolic phenotypes across cell lines. Significance refers to comparisons between DTC cell lines and the non-malignant Nthy-Ori 3.1 cell line. Data are shown as mean ± SEM for n≥3, whereas data for basal glycolysis and compensatory glycolysis are shown as mean ± SD for n=2. Statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparison test. Significance is indicated as *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, and ****p < 0.0001.

Figure 1.

Baseline drug response and metabolic characterization of differentiated thyroid cancer (DTC) and non-malignant thyroid cell lines. (a-c) Cell viability of four DTC cell lines and one non-malignant thyroid cell line (Nthy-Ori 3.1) following treatment with (a) lenvatinib, (b) tigecycline, and (c) eravacycline for 72 h. Line charts show viability curves normalized to untreated controls (% UTC). IC50 values were determined with log(agonist) vs. response – Variable slope (four parameters) including 95% upper and lower confidence intervals (C.I.). (d) Representative kinetic profile of the Mito Stress test using oligomycin (Oligo, 2.5 µM), the uncoupling agent fluoro-carbonyl cyanide phenylhydrazone (FCCP, 1 µM), and a combination of rotenone/antimycin A followed by Hoechst 33342 injection for normalization (Rot/AA/Hoechst, 0.5 µM, 0.5 µM and 2 µM, respectively). (e) Representative profile of the Glycolytic Rate assay with injections of Rot/AA (0.5 µM each), 2-deoxyglucose (2-DG, 50 mM) and Hoechst (2 µM). (f-m) Quantification of key metabolic parameters from Seahorse analysis: (f) basal respiration, (g) maximal respiration, (h) ATP-linked respiration, (i) proton leak, (j) coupling efficiency, (k) basal glycolysis, (l) compensatory glycolysis, and (m) OCR/ECAR ratios. (n) Energy map visualizing metabolic phenotypes across cell lines. Significance refers to comparisons between DTC cell lines and the non-malignant Nthy-Ori 3.1 cell line. Data are shown as mean ± SEM for n≥3, whereas data for basal glycolysis and compensatory glycolysis are shown as mean ± SD for n=2. Statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparison test. Significance is indicated as *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, and ****p < 0.0001.

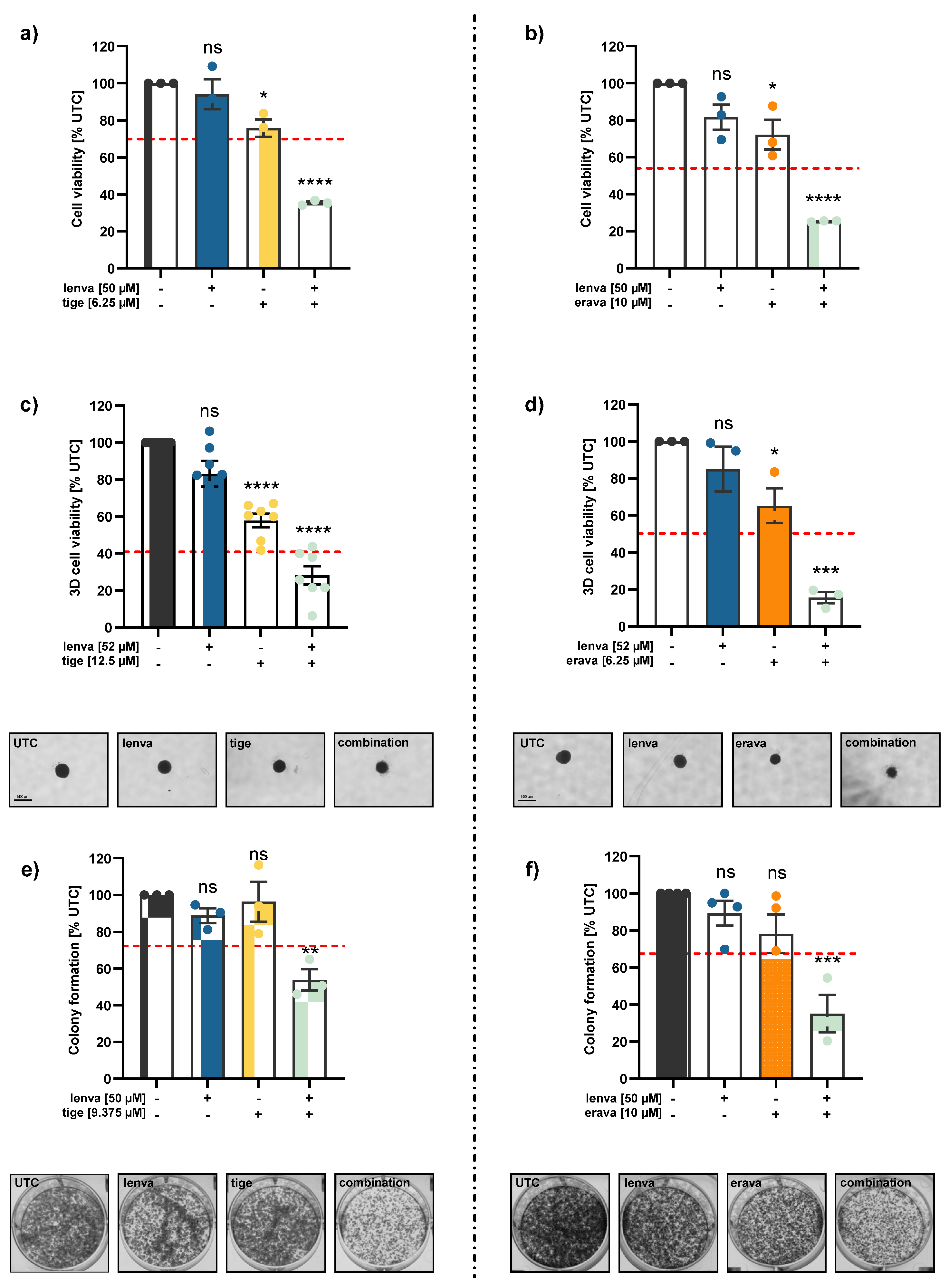

Figure 2.

Effects of combination treatments in the differentiated thyroid cancer (DTC) cell line K1. (a-b) 2D cell viability of K1 cells after 72 h treatment with lenvatinib (lenva, 50 µM), tigecycline (tige, 6.25 µM) or eravacycline (erava, 10 µM) and their respective combinations. (c-d) 3D spheroid viability of K1 cells following 96 h treatment with lenva (52 µM), tige (12.5 µM), erava (6.25 µM) and their respective combinations. Representative images of spheroids are shown; scale bar = 500 µm. (e-f) Colony formation assays after 24 h pre-treatment with lenva (50 µM), tige (9.375 µM), erava (10 µM) or combinations followed by re-seeding and 5 days of cultivation. Representative colony images are shown. The red dotted line indicates the expected additive effect (EA) in each graph and serves as a threshold for synergism. All data are normalized to the untreated controls (% UTC) and shown as mean ± SEM for n≥3; statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparison test. Significance is indicated as *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, and ****p < 0.0001 or not significant (ns).

Figure 2.

Effects of combination treatments in the differentiated thyroid cancer (DTC) cell line K1. (a-b) 2D cell viability of K1 cells after 72 h treatment with lenvatinib (lenva, 50 µM), tigecycline (tige, 6.25 µM) or eravacycline (erava, 10 µM) and their respective combinations. (c-d) 3D spheroid viability of K1 cells following 96 h treatment with lenva (52 µM), tige (12.5 µM), erava (6.25 µM) and their respective combinations. Representative images of spheroids are shown; scale bar = 500 µm. (e-f) Colony formation assays after 24 h pre-treatment with lenva (50 µM), tige (9.375 µM), erava (10 µM) or combinations followed by re-seeding and 5 days of cultivation. Representative colony images are shown. The red dotted line indicates the expected additive effect (EA) in each graph and serves as a threshold for synergism. All data are normalized to the untreated controls (% UTC) and shown as mean ± SEM for n≥3; statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparison test. Significance is indicated as *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, and ****p < 0.0001 or not significant (ns).

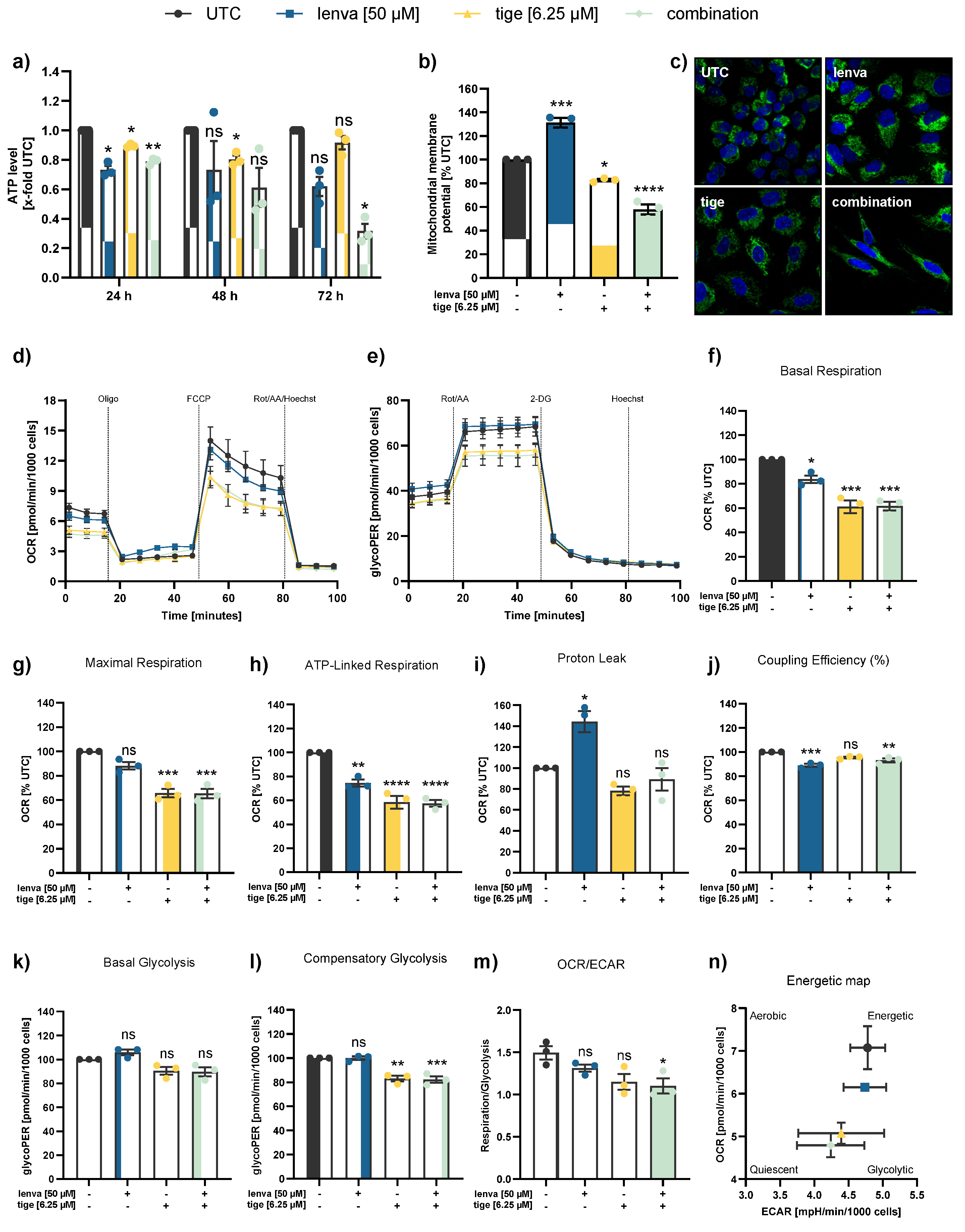

Figure 3.

Assessment of mitochondrial function and cellular metabolism in differentiated thyroid (DTC) K1 cancer cells after treatment with lenvatinib, tigecycline, and their combination. (a) ATP levels after 24, 48 and 72 h treatment with lenvatinib (lenva, 50 µM), tigecycline (tige, 6.25 µM), or their combination. (b) Mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP) after 72 h treatment measured by the JC-10 assay. (c) Confocal microscopy images after 72 h treatment showing nuclear staining (Hoechst 33342) and mitochondrial staining (MitoTracker Green), with a magnification of 40x (Zeiss LSM 700). (d) Representative line chart of the Seahorse XF Cell Mito Stress test using sequential injections of oligomycin (Oligo, 2.5 µM), the uncoupling agent fluoro-carbonyl cyanide phenylhydrazone (FCCP, 1 µM), and a combination of rotenone/antimycin A followed by Hoechst 33342 injection for normalization (Rot/AA/Hoechst, 0.5 µM, 0.5 µM and 2 µM, respectively). (e) Representative profile of the Glycolytic Rate assay with injections of Rot/AA (0.5 µM each), 2-deoxyglucose (2-DG, 50 mM) and Hoechst (2 µM). (f-m) Quantification of mitochondrial and glycolytic parameters after 12 h treatment: (f) basal respiration, (g) maximal respiration, (h) ATP-linked respiration, (i) proton leak, (j) coupling efficiency, (k) basal glycolysis, (l) compensatory glycolysis, and (m) OCR/ECAR ratios. (n) Energy map visualizing metabolic phenotypes. All data are normalized to the untreated controls (% UTC) and shown as mean ± SEM for n≥3; statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparison test. Significance is indicated as *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, and ****p < 0.0001 or not significant (ns).

Figure 3.

Assessment of mitochondrial function and cellular metabolism in differentiated thyroid (DTC) K1 cancer cells after treatment with lenvatinib, tigecycline, and their combination. (a) ATP levels after 24, 48 and 72 h treatment with lenvatinib (lenva, 50 µM), tigecycline (tige, 6.25 µM), or their combination. (b) Mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP) after 72 h treatment measured by the JC-10 assay. (c) Confocal microscopy images after 72 h treatment showing nuclear staining (Hoechst 33342) and mitochondrial staining (MitoTracker Green), with a magnification of 40x (Zeiss LSM 700). (d) Representative line chart of the Seahorse XF Cell Mito Stress test using sequential injections of oligomycin (Oligo, 2.5 µM), the uncoupling agent fluoro-carbonyl cyanide phenylhydrazone (FCCP, 1 µM), and a combination of rotenone/antimycin A followed by Hoechst 33342 injection for normalization (Rot/AA/Hoechst, 0.5 µM, 0.5 µM and 2 µM, respectively). (e) Representative profile of the Glycolytic Rate assay with injections of Rot/AA (0.5 µM each), 2-deoxyglucose (2-DG, 50 mM) and Hoechst (2 µM). (f-m) Quantification of mitochondrial and glycolytic parameters after 12 h treatment: (f) basal respiration, (g) maximal respiration, (h) ATP-linked respiration, (i) proton leak, (j) coupling efficiency, (k) basal glycolysis, (l) compensatory glycolysis, and (m) OCR/ECAR ratios. (n) Energy map visualizing metabolic phenotypes. All data are normalized to the untreated controls (% UTC) and shown as mean ± SEM for n≥3; statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparison test. Significance is indicated as *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, and ****p < 0.0001 or not significant (ns).

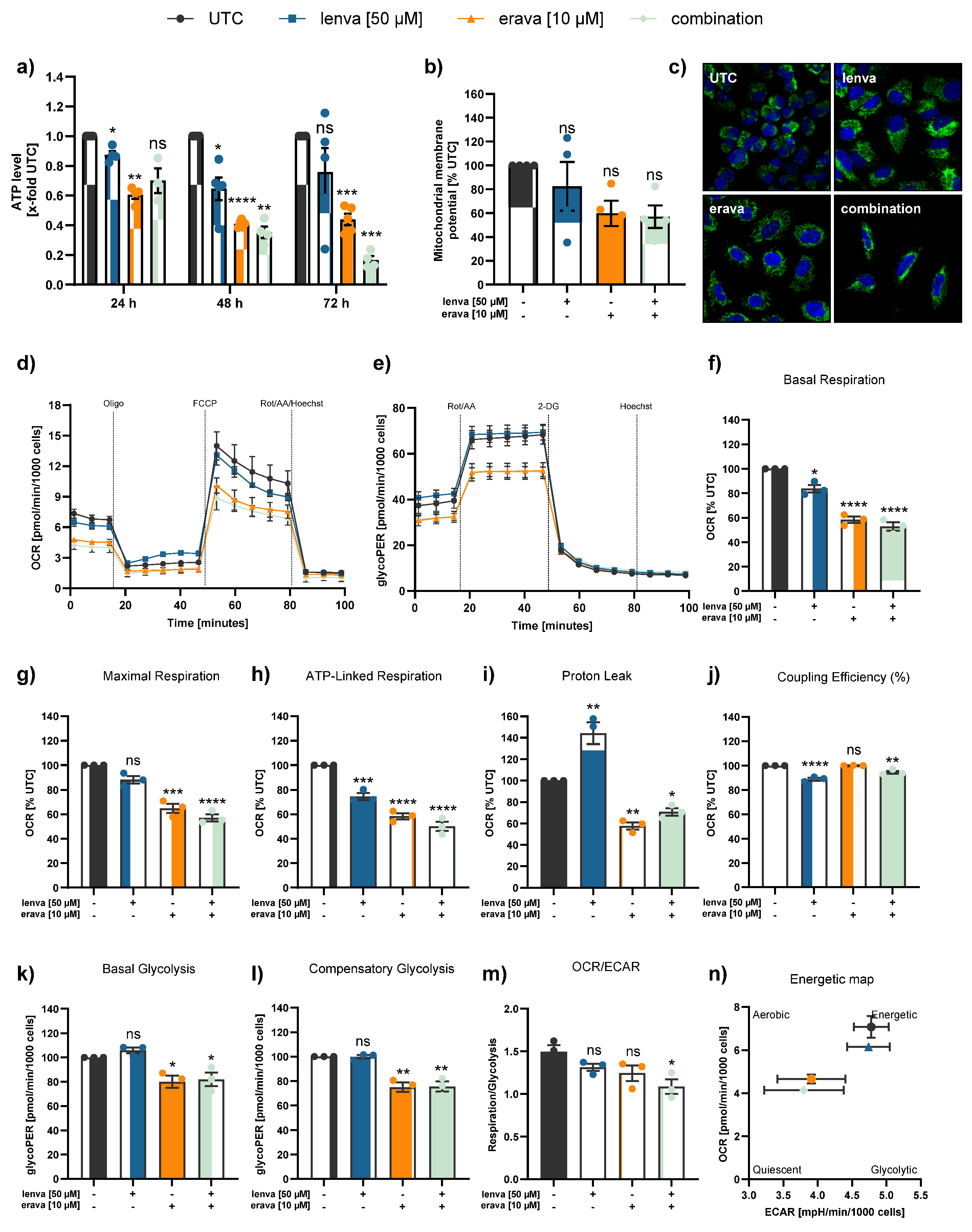

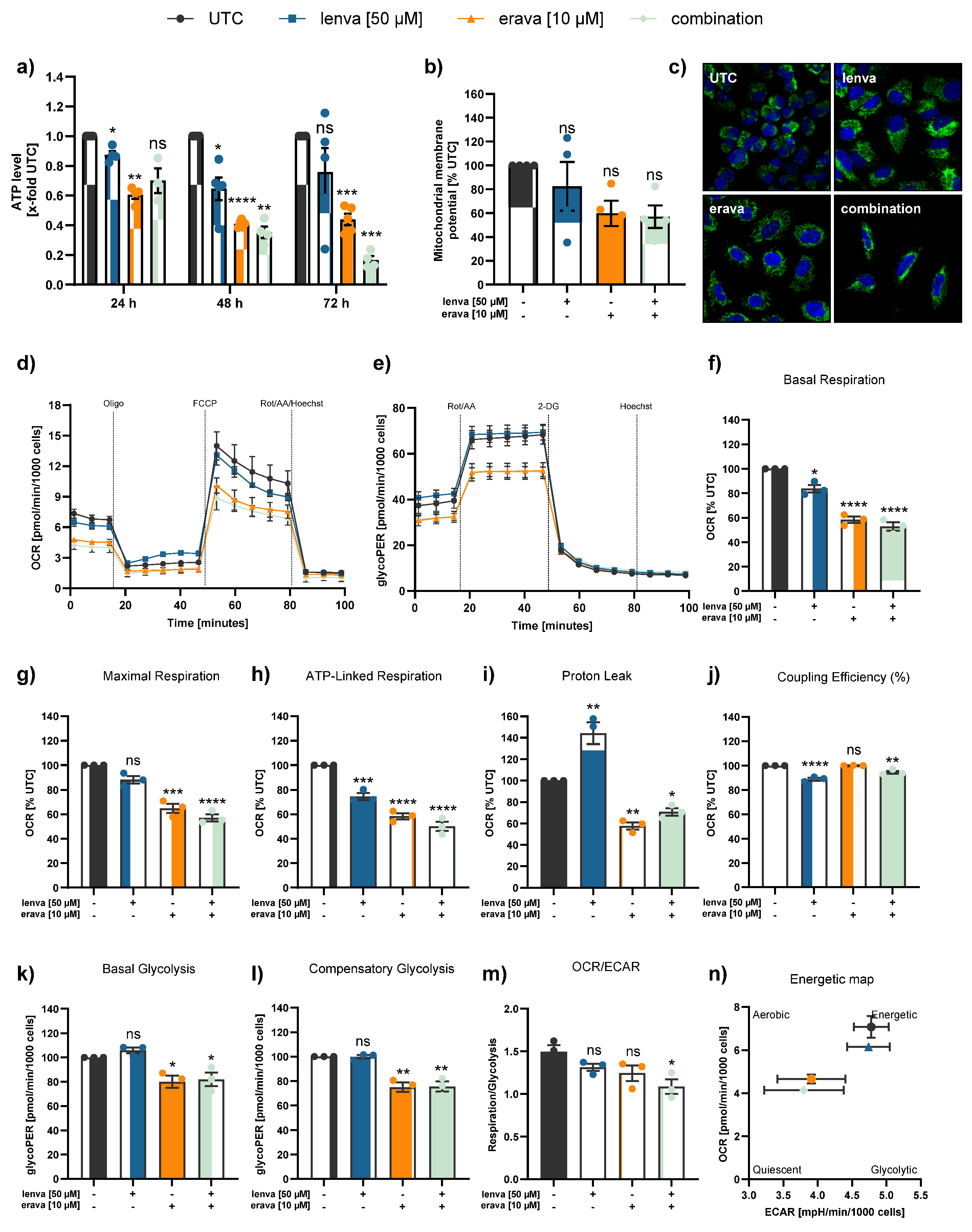

Figure 4.

Assessment of mitochondrial function and cellular metabolism in differentiated thyroid (DTC) K1 cancer cells after treatment with lenvatinib, eravacycline, and their combination. (a) ATP levels after 24, 48 and 72h treatment with lenvatinib (lenva, 50 µM), eravacycline (erava, 6.25 µM), or their combination. (b) Mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP) after 72 h treatment measured by JC-10 assay. (c) Confocal microscopy images after 72 h treatment showing nuclear staining (Hoechst 33342) and mitochondrial staining (MitoTracker Green), with a magnification of 40x (Zeiss LSM 700). (d) Representative line chart of the Seahorse XF Cell Mito Stress test using sequential injections of oligomycin (Oligo, 2.5 µM), the uncoupling agent fluoro-carbonyl cyanide phenylhydrazone (FCCP, 1 µM), and a combination of rotenone/antimycin A followed by Hoechst 33342 injection for normalization (Rot/AA/Hoechst, 0.5 µM, 0.5 µM and 2 µM, respectively). (e) Representative profile of the Glycolytic Rate assay with injections of Rot/AA (0.5 µM each), 2-deoxyglucose (2-DG, 50 mM) and Hoechst (2 µM). (f-m) Quantification of mitochondrial and glycolytic parameters after 12 h treatment: (f) basal respiration, (g) maximal respiration, (h) ATP-linked respiration, (i) proton leak, (j) coupling efficiency, (k) basal glycolysis, (l) compensatory glycolysis, and (m) OCR/ECAR ratios. (n) Energy map visualizing metabolic phenotypes. All data are normalized to the untreated controls (% UTC) and shown as mean ± SEM for n≥3; statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparison test. Significance is indicated as *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, and ****p < 0.0001 or not significant (ns).

Figure 4.

Assessment of mitochondrial function and cellular metabolism in differentiated thyroid (DTC) K1 cancer cells after treatment with lenvatinib, eravacycline, and their combination. (a) ATP levels after 24, 48 and 72h treatment with lenvatinib (lenva, 50 µM), eravacycline (erava, 6.25 µM), or their combination. (b) Mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP) after 72 h treatment measured by JC-10 assay. (c) Confocal microscopy images after 72 h treatment showing nuclear staining (Hoechst 33342) and mitochondrial staining (MitoTracker Green), with a magnification of 40x (Zeiss LSM 700). (d) Representative line chart of the Seahorse XF Cell Mito Stress test using sequential injections of oligomycin (Oligo, 2.5 µM), the uncoupling agent fluoro-carbonyl cyanide phenylhydrazone (FCCP, 1 µM), and a combination of rotenone/antimycin A followed by Hoechst 33342 injection for normalization (Rot/AA/Hoechst, 0.5 µM, 0.5 µM and 2 µM, respectively). (e) Representative profile of the Glycolytic Rate assay with injections of Rot/AA (0.5 µM each), 2-deoxyglucose (2-DG, 50 mM) and Hoechst (2 µM). (f-m) Quantification of mitochondrial and glycolytic parameters after 12 h treatment: (f) basal respiration, (g) maximal respiration, (h) ATP-linked respiration, (i) proton leak, (j) coupling efficiency, (k) basal glycolysis, (l) compensatory glycolysis, and (m) OCR/ECAR ratios. (n) Energy map visualizing metabolic phenotypes. All data are normalized to the untreated controls (% UTC) and shown as mean ± SEM for n≥3; statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparison test. Significance is indicated as *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, and ****p < 0.0001 or not significant (ns).

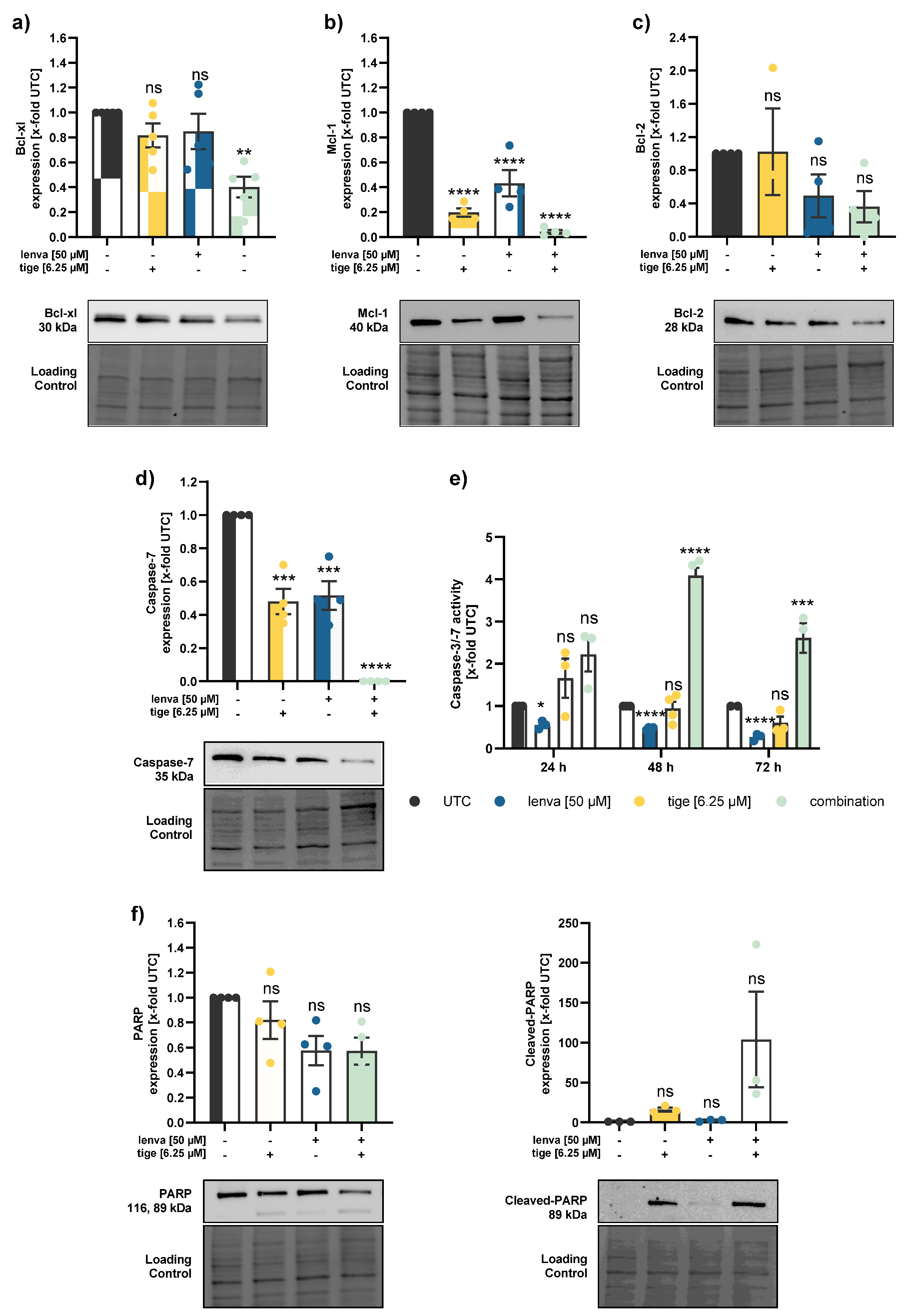

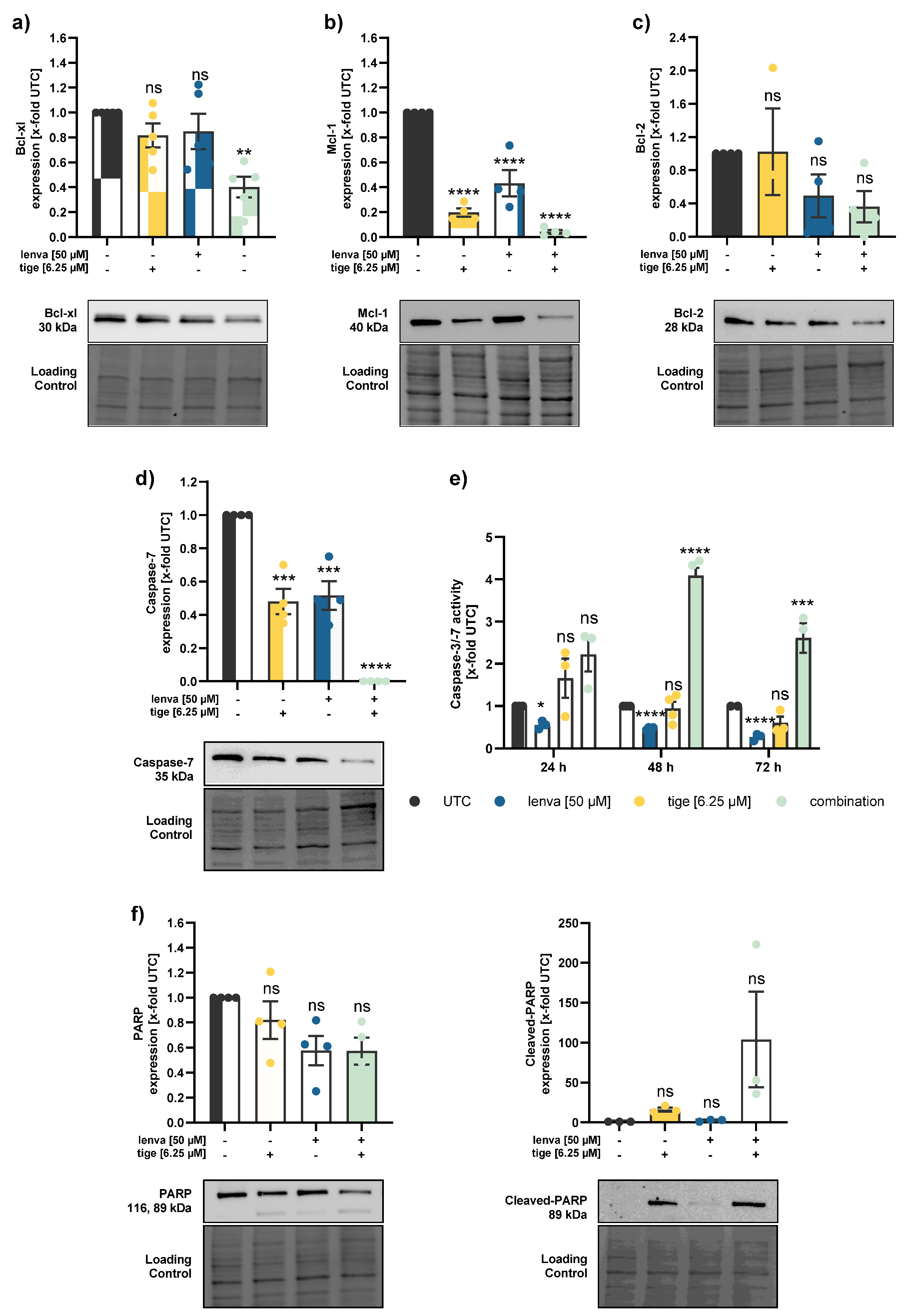

Figure 5.

Effect of lenvatinib and tigecycline combinational treatment on apoptosis related proteins and activity in differentiated thyroid (DTC) K1 cancer cells. Western blot analysis of (a) Bcl-xl, (b) Mcl-1, (c) Bcl-2, (d) Caspase-7, and (f) PARP and Cleaved-PARP in K1 cells after 24 h treatment with lenvatinib (50 µM), tigecycline (6.25 µM) or their combination. Protein expression was quantified via normalization to corresponding loading controls, which were further referred to untreated control cells (x-fold to untreated control = UTC). (e) Caspase-3/7 activity was measured in K1 cells after treatment with lenvatinib (50 µM), tigecycline (6.25 µM) or the combination of both for 24, 48 and 72 h. Luminescence values were normalized to the UTC (x-fold). Data are shown as mean ± SEM for n≥3; statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparison test. Significance is indicated as *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, and ****p < 0.0001 or not significant (ns).

Figure 5.

Effect of lenvatinib and tigecycline combinational treatment on apoptosis related proteins and activity in differentiated thyroid (DTC) K1 cancer cells. Western blot analysis of (a) Bcl-xl, (b) Mcl-1, (c) Bcl-2, (d) Caspase-7, and (f) PARP and Cleaved-PARP in K1 cells after 24 h treatment with lenvatinib (50 µM), tigecycline (6.25 µM) or their combination. Protein expression was quantified via normalization to corresponding loading controls, which were further referred to untreated control cells (x-fold to untreated control = UTC). (e) Caspase-3/7 activity was measured in K1 cells after treatment with lenvatinib (50 µM), tigecycline (6.25 µM) or the combination of both for 24, 48 and 72 h. Luminescence values were normalized to the UTC (x-fold). Data are shown as mean ± SEM for n≥3; statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparison test. Significance is indicated as *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, and ****p < 0.0001 or not significant (ns).

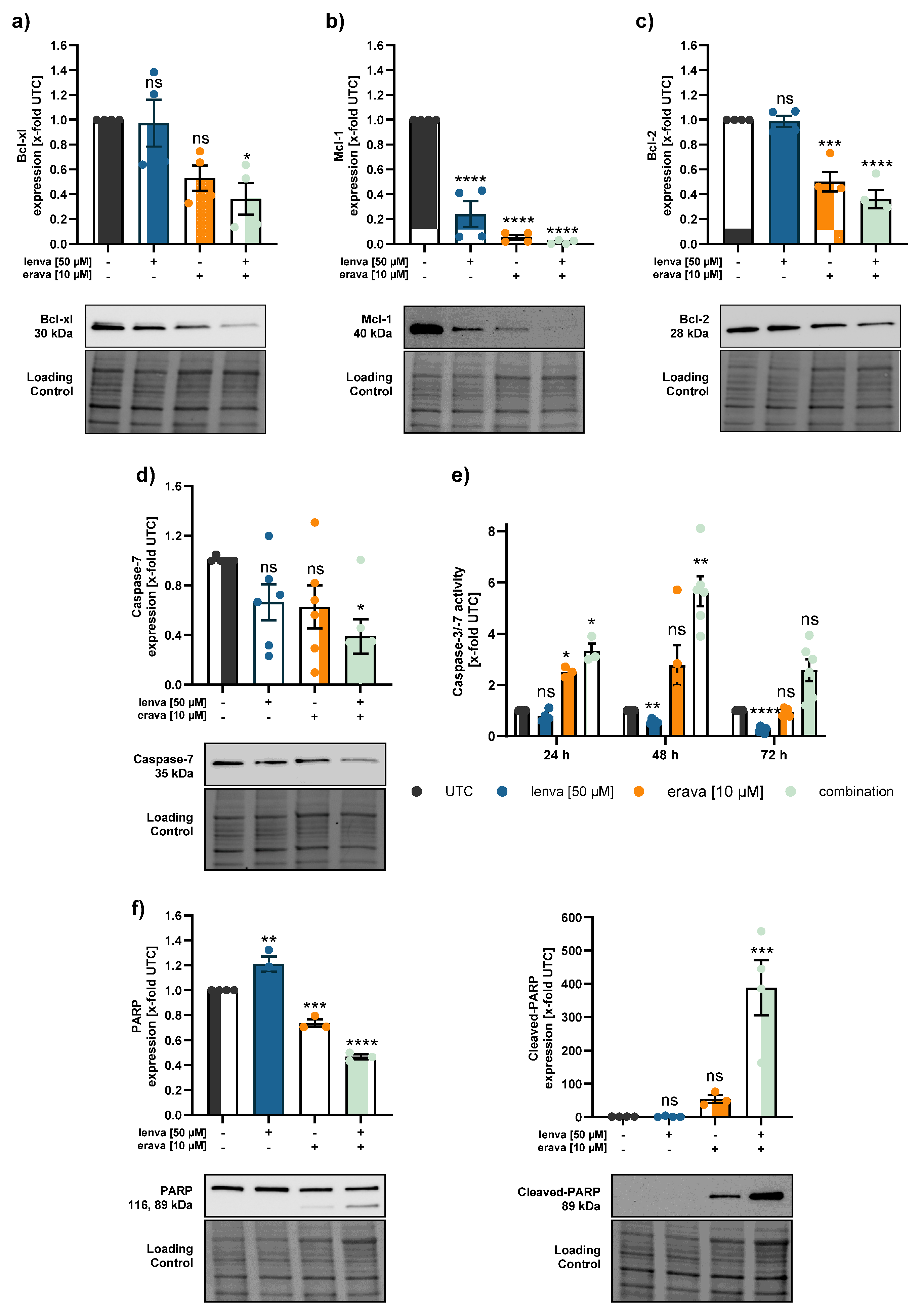

Figure 6.

Effect of lenvatinib and eravacycline combinational treatment on apoptosis related proteins and activity in differentiated thyroid (DTC) K1 cancer cells. Western blot analysis of (a) Bcl-xl, (b) Mcl-1, (c) Bcl-2, (d) Caspase-7, and (f) PARP and Cleaved-PARP in K1 cells after 24 h treatment with lenvatinib (50 µM), eravacycline (10 µM) or their combination. Protein expression was quantified via normalization to corresponding loading controls, which were further referred to untreated control cells (x-fold to untreated control = UTC). (e) Caspase-3/7 activity was measured in K1 cells after treatment with lenvatinib (50 µM), eravacycline (10 µM) or the combination of both for 24, 48 and 72 h. Luminescence values were normalized to UTC (x-fold). Data are shown as mean ± SEM for n≥3; statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparison test. Significance is indicated as *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, and ****p < 0.0001 or not significant (ns).

Figure 6.

Effect of lenvatinib and eravacycline combinational treatment on apoptosis related proteins and activity in differentiated thyroid (DTC) K1 cancer cells. Western blot analysis of (a) Bcl-xl, (b) Mcl-1, (c) Bcl-2, (d) Caspase-7, and (f) PARP and Cleaved-PARP in K1 cells after 24 h treatment with lenvatinib (50 µM), eravacycline (10 µM) or their combination. Protein expression was quantified via normalization to corresponding loading controls, which were further referred to untreated control cells (x-fold to untreated control = UTC). (e) Caspase-3/7 activity was measured in K1 cells after treatment with lenvatinib (50 µM), eravacycline (10 µM) or the combination of both for 24, 48 and 72 h. Luminescence values were normalized to UTC (x-fold). Data are shown as mean ± SEM for n≥3; statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparison test. Significance is indicated as *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, and ****p < 0.0001 or not significant (ns).