Introduction

HELLP syndrome represents a rare yet severe obstetric condition that occurs in fewer than 1% of pregnancies and is characterized by serious liver and blood complications. Typically, HELLP syndrome develops during the late stages of pregnancy or shortly after delivery, posing considerable risks to both maternal and fetal health. Diagnosis is based on specific laboratory findings indicating hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelet counts. Unlike preeclampsia, HELLP syndrome does not always present with elevated blood pressure (>140/90 mmHg) or significant proteinuria (>300 mg/day or a protein:creatinine ratio >30 mg/mmol). The diagnostic criteria for HELLP syndrome include the presence of hemolysis, increased liver enzymes, and thrombocytopenia, with hemolysis resulting from the destruction of red blood cells as they traverse damaged blood vessels. Laboratory tests may reveal hepatomegaly and elevated liver function tests (LFTs). Key indicators of hemolysis include the presence of schistocytes, low serum haptoglobin levels, decreased hemoglobin, elevated lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), and increased indirect bilirubin levels. Elevated liver enzymes, particularly aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and alanine aminotransferase (ALT), occur as a result of sinusoidal microangiopathy, which leads to necrosis of hepatocytes. Thrombocytopenia, or low platelet count, arises due to increased consumption of platelets in areas of vascular injury. HELLP syndrome is classified primarily using the Mississippi and Tennessee classification systems, which assess severity based on platelet counts and other relevant laboratory values.

Women with a family history of HELLP syndrome are at a significantly higher risk for developing the condition, particularly if their mothers or sisters have experienced it. Typically, women diagnosed with HELLP syndrome are older than those diagnosed with preeclampsia. The incidence of HELLP syndrome is notably higher among African-American women compared to their Caucasian counterparts. Additionally, the condition is more prevalent in multiple-fetus pregnancies due to increased thrombocytopenia and liver dysfunction. Women with a history of high-risk pregnancies also exhibit an elevated risk of developing HELLP syndrome. Evidence indicates that women who have previously experienced HELLP syndrome have a less than 20% chance of encountering hypertensive disorders in future pregnancies. HELLP syndrome is characterized by hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelet counts, with symptoms including abdominal pain, nausea, headaches, and elevated blood pressure. Management typically occurs postpartum, with corticosteroids potentially utilized to mitigate disease progression and severity. A standardized treatment approach, referred to as the Mississippi protocol, has been established for the effective management of HELLP syndrome.

N-acetylcysteine (NAC) is recognized for its hepatoprotective properties and has demonstrated effectiveness in reducing hepatotoxicity from various substances. Initially introduced as a mucolytic agent in the 1960s, NAC is also the primary antidote for acetaminophen overdose. This thiol, derived from the amino acid L-cysteine, acts as a precursor to endogenous reduced glutathione. Its mechanism in the treatment of acetaminophen toxicity involves replenishing depleted intracellular glutathione or serving as an alternative thiol substrate. Furthermore, NAC can break disulfide bonds, bind to metal contaminants, and neutralize free radicals, thereby demonstrating its multifunctional role in cellular protection against oxidative stress.

Methods

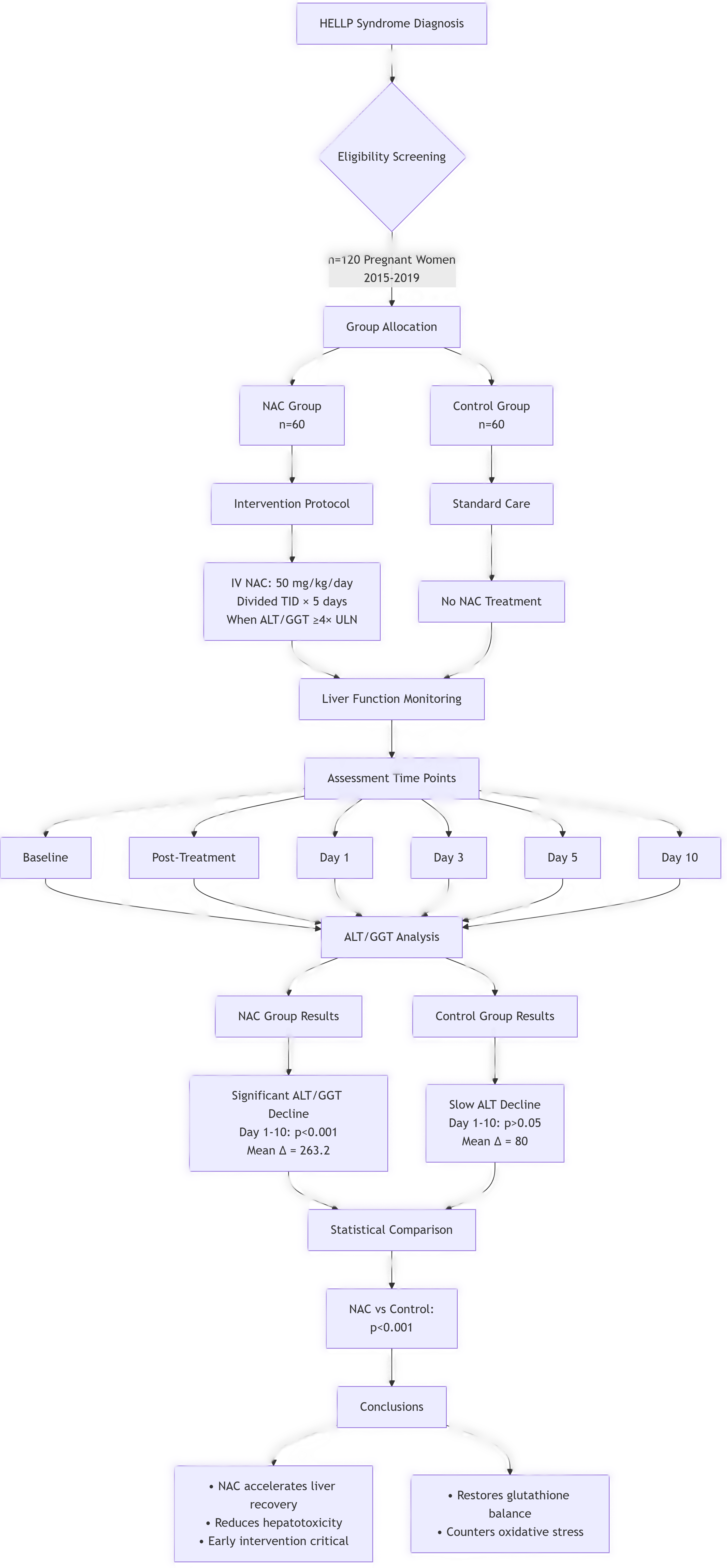

The study involved a retrospective analysis of 120 pregnant patients diagnosed with HELLP syndrome from 2015 to 2019. Participants were categorized into NAC and non-NAC groups based on their treatment regimens. When ALT or GGT levels spiked to four times the normal threshold, 60 patients received NAC at a dosage of 50 mg/kg intravenously, administered over a three-day period. The control group included 60 postoperative patients diagnosed with HELLP syndrome who did not receive NAC. ALT and GGT levels were documented at baseline, post-treatment, and on days 1, 3, 5, and 10 following treatment to provide a comprehensive assessment of liver function dynamics. Differential diagnoses encompassed acute fatty liver of pregnancy, thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura, antiphospholipid syndrome, and hemolytic uremic syndrome, ensuring a thorough evaluation of potential confounding factors. Further exploration into the roles of corticosteroids, low molecular weight heparin, and additional treatments for HELLP syndrome is warranted, necessitating larger randomized controlled trials to establish comprehensive management protocols.

Results

Demographic and diagnostic data for both groups are summarized in

Table 1. The average age in the non-NAC group was 24.31 years, while in the NAC group, it was 23.07 years, with no significant differences noted (p>0.05). Statistically significant changes were observed in the NAC group with a p-value of <0.001. In the non-NAC group, ALT levels exhibited a decrease from day 10 compared to day 1. The NAC group demonstrated a more pronounced reduction in GGT levels compared to the non-NAC group, with a p-value of <0.001 indicating a highly significant difference.

Table 1.

Diagnostic Criteria for HELLP Syndrome Classification.

Table 1.

Diagnostic Criteria for HELLP Syndrome Classification.

| Mississippi |

HELLP Class |

Platelets (L) |

AST* or ALT (IU/L) |

LDH (IU/L) |

| 1 |

≤50x10^9 |

≥70 |

≥600 |

|

| 2 |

≤100x10^9 to ≥50x10^9 |

≥70 |

≥600 |

|

| 3 |

≤150x10^9 to ≥100x10^9 |

≥40 |

≥600 |

|

| Partial HELLP |

Presence of 2 of the 3 laboratory abnormalities and evidence of severe preeclampsia or eclampsia |

|

|

|

Table 2.

Demographics and Diagnosis Distribution in NAC and Non-NAC Groups.

Table 2.

Demographics and Diagnosis Distribution in NAC and Non-NAC Groups.

| Group |

Non-NAC (n=60) |

NAC (n=60) |

P-value |

| Gender |

Female: 60 (100) |

Female: 60 (100) |

1 |

| Diagnosis |

Pre-eclampsia: 30 (50) |

25 (40.6) |

0.73 |

| Recurrent HELLP |

12 (20) |

10 (16.6) |

0.81 |

| Age (years) |

Mean ± SD: 24.31± 6.32 |

23.07± 7.75 |

0.77 |

Table 3.

Changes in ALT and GGT Levels Over Time.

Table 3.

Changes in ALT and GGT Levels Over Time.

| Day |

Non-NAC Group (n=60) |

NAC Group (n=60) |

| 1-3 |

Mean: 1.9, P: > 0.05 |

Mean: 112.5, P: 0.003 |

| 3-5 |

Mean: 36.1, P: > 0.05 |

Mean: 145.2, P: 0.000 |

| 5-10 |

Mean: 41.9, P: 0.006 |

Mean: 89.1, P: 0.000 |

| 1-10 |

Mean: 80, P:> 0.05 |

Mean: 263.2, P: 0.000 |

Statistically significant changes were noted in ALT and GGT levels within the NAC group, with reductions observed from day 1 to day 10, indicating a robust therapeutic response to NAC treatment.

Discussion

NAC has been established as a hepatoprotective agent that alleviates various forms of hepatotoxicity, and this study explored NAC’s potential in mitigating liver damage related to HELLP syndrome. Elevated bilirubin levels may be associated with decreased drug clearance, while hypoalbuminemia increases the risk of hematologic toxicity. Dose modifications are recommended for patients with low serum albumin to ensure optimal therapeutic outcomes. Our findings indicate that the NAC group experienced significant reductions in ALT and GGT values compared to the non-NAC group at the specified intervals, underscoring NAC’s potential in clinical practice.

Oxidative stress is a major contributor to tissue damage, with many chemotherapeutic agents generating reactive oxygen species (ROS) that can lower antioxidant enzyme levels. Glutathione peroxidase plays a crucial role in protecting tissues against oxidative damage by converting hydrogen peroxide into harmless water. Previous studies have shown that NAC diminishes lipid peroxidation and enhances glutathione levels in liver tissues, suggesting its capability to counteract the toxic effects of HELLP syndrome. Glutathione, a tripeptide found in all mammalian cells, is essential for combating free radicals and toxic substances. Thiol compounds, particularly glutathione, are vital for preserving cell viability and maintaining membrane integrity. NAC’s role as a glutathione precursor indicates its potential effectiveness in restoring cellular GSH levels diminished by HELLP syndrome.

The data suggest that NAC treatment modifies the oxidant-antioxidant balance, which may initially lead to free radical production but ultimately results in increased GSH levels once homeostasis is regained. The results indicate that HELLP syndrome significantly reduces GSH levels, which can be restored through NAC administration. This finding suggests that NAC may enhance the body’s response to oxidative stress in compromised tissues by raising GSH levels. Recent research highlights the involvement of reactive oxygen metabolites in HELLP syndrome-related hepatotoxicity, further supporting the need for antioxidant therapies to reduce oxidative damage and improve clinical outcomes.

Conclusions

This study demonstrates that HELLP syndrome results in significant increases in liver function parameters. The NAC group exhibited notable differences in ALT and GGT values, with a marked decline observed from day 1 to day 10 post-treatment. Statistical analyses confirm that liver function tests improved significantly in the NAC group, indicating that early intervention with NAC could be crucial for effectively managing hepatotoxicity in pregnant women diagnosed with HELLP syndrome. Future research should explore the long-term outcomes of NAC therapy in this population, as well as investigate additional therapeutic strategies that may complement NAC in the management of HELLP syndrome.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

References

- Finotti M, Zanetto A, Vitale A, Rodriguez-Davalos M, Burra P, Cillo U, D'Amico F. N-Acetylcysteine and Liver Transplant. Advantages of its Administration in Multi-Organ Donors Especially During World-Economical-Crisis. Long-Term Sub-Group Analysis in a Randomized Study. Transplant Proc. 2025 Mar;57(2):264-271. Epub 2025 Jan 14. PMID: 39809659. [CrossRef]

- Wallace K, Harris S, Addison A, Bean C. HELLP Syndrome: Pathophysiology and Current Therapies. Curr Pharm Biotechnol. 2018;19(10):816-826. PMID: 29998801. [CrossRef]

- Weijl NI, Cleton FJ, Osanto S (1997) Free radicals and antioxidants in chemotherapy-induced toxicity. Cancer Treat Rev 23:209–240. [CrossRef]

- Crohns M, Liippo K, Erhola M et al (2009) Concurrent decline of several antioxidants and markers of oxidative stress during combination chemotherapy for small cell lung cancer. Clin Biochem 42: 1236–1245. [CrossRef]

- Simone CB, Simone NL, Simone V (2007) Antioxidants and other nutrients do not interfere with chemotherapy or radiation therapy and can increase kill and increase survival. Altern Ther Health Med 13:22–28.

- Facorro G, SarrasagueMM TH, Hager A et al (2004) Oxidative study of patients with total body irradiation: effects of amifostine treatment. BoneMarrowTransplant33:793–798. [CrossRef]

- Chen Y, JungsuwadeP VM, Butterfield DA, St Clair DK (2007) Collateral damage in cancer chemotherapy: oxidative stress in nontargeted tissues. Mol Interv 7:147–156. [CrossRef]

- SariI CA, Kaynar L, Saraymen R et al (2008) Disturbance of prooxidative/antioxidative balance in allogeneic peripheral blood stem cell transplantation. Ann Clin Lab Sci 38:120–125.

- Brea-Calvo G, Rodríguez-Hernández A, Fernández-Ayala et al (2006) Chemotherapy induces an increase in coenzyme Q10 levels incancer cell lines. Free Radic BiolMed 40:1293–1302. [CrossRef]

- Sangeetha P, Das UN, Koratkar R, Suryaprabha P (1990) Increase in free radical generation and lipid peroxidation following chemotherapy in patients with cancer. Free Radic Biol Med 8:15–19. [CrossRef]

- White AC, Sousa AM, Blumberg J et al (2006) Plasma antioxidants in subjects before hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant 38:513–520. [CrossRef]

- Clemens MR, Waladkhani AR, Bublitz K et al (1997) Supplementationwithantioxidants prior to bonemarrowtransplantation. Wien Klin Wochenschr 109:771–776.

- Fridovich I (1983) Superoxide radical: an endogenous toxicant. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 23:239–257. [CrossRef]

- Sugiyama S, Hayakawa M, Kato T et al (1989) Adverse effects of anti-tumor drug, cisplatin, on rat kidney mitochondria: disturbances in glutathione peroxidase activity. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 159:1121–1127. [CrossRef]

- Zhang JG, Zhong LF, Zhang M, Xia YX (1992) Protection effects of procaine on oxidative stress and toxicities of renal cortical slices from rats caused by cisplatin in vitro. Arch Toxicol 66:354–358. [CrossRef]

- Gill RA, Onstad GR, Cardamone JM et al (1982) Hepatic venoocclusive disease caused by 6-thioguanine. Ann Intern Med 96:58– 60. [CrossRef]

- Stoneham S, Lennard L, Coen P et al (2003) Veno-occlusive disease in patients receiving thiopurines during maintenance therapy for childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Br J Haematol 123: 100–102. [CrossRef]

- Lee WM (1995) Drug-induced hepatotoxicity. N Engl J Med 333: 1118–1127. [CrossRef]

- DeLeve LD, Shulman HM, McDonald GB (2002) Toxic injury to hepatic sinusoids: sinusoidal obstruction syndrome (veno-occlusive disease). Semin Liver Dis 22:27–42. [CrossRef]

- Chughlay MF, Kramer N, Spearman CV et al (2016) Nacetylcysteine for non-paracetamol drug induced liver injury: a systematic review. Br J Clin Pharmacol 81:1021–1029. [CrossRef]

- Koren G, Beatty K, Seto A et al (1992) The effects of impaired liver function on the elimination of antineoplastic agents. Ann Pharmacother 26:363–371. [CrossRef]

- Desai ZR, Van den Berg HW, Bridges JM, Shanks RG (1982) Can severe vincristine neurotoxicity be prevented? Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 8:211–214. [CrossRef]

- Hohneker JA (1994) A summary of vinorelbine (Navelbine) safety datafrom north American clinical trials. Semin Oncol 21:42–46.

- Van den Berg HW, Desai ZR, Wilson R et al (1982) The pharmacokinetics of vincristine in man: reduced drug clearance associated with raised serum alkaline phosphatase and dose-limited elimination. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 8:215–219. [CrossRef]

- Stewart CF, Arbuck SG, Fleming RA, Evans WE (1990) Changes intheclearance of total and unbound etoposideinpatients withliver dysfunction. J Clin Oncol 8:1874–1879. [CrossRef]

- Raymond E, Boige V, Faivre S et al (2002) Dosage adjustment and pharmacokinetic profile ofirinotecan incancerpatientswith hepatic dysfunction. J Clin Oncol 20:4303–4312. [CrossRef]

- Neuman MG, Cameron RG, Haber JA et al (1999) Inducers of cytochrome P450 2E1 enhance methotrexate-induced hepatocytoxicity. Clin Biochem 32:519–536. [CrossRef]

- Jahovic N, Cevik H, Sehirli AO et al (2003) Melatonin prevents methotrexate-induced hepatorenal oxidative injury in rats. J Pineal Res 34:282–287.

- Cetiner M, Sener G, Sehirli AO et al (2005) Taurine protects against methotrexate-induced toxicity and inhibits leukocyte death. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 209:39–50. [CrossRef]

- Ali N, Rashid S, Nafees S et al (2017) Protective effect of chlorogenic acid against methotrexate induced oxidative stress, inflammation and apoptosis in rat liver: an experimental approach. Chem Biol Interact 272:80–91. [CrossRef]

- Szabo S (1984) Role of sulfhydryls and early vascular lesions in gastric mucosal injury. Acta Physiol Hung 64:203–214.

- Ross D (1988) Glutathione, free radicals and chemotherapeutic agents. Mechanisms of free-radical induced toxicity and glutathione-dependent protection. Pharmacol Ther 37:231–249. [CrossRef]

- Babiak RM, Campello AP, Carnieri EG (1998) Methotrexate: pentose cycle and oxidative stress. Cell Biochem Funct 16:283–293. [CrossRef]

- Manov I, Hırsh M, Iancu TC (2002) Acetaminophen hepatotoxicity and mechanisms of its protection by N-acetylcysteine: a study of Hep3B cells. Exp Toxicol Pathol 53:489–500. [CrossRef]

- Kumar O, Sugendran K, Vijayaraghavan R (2003) Oxidative stress associated hepatic and renal toxicity induced by ricin in mice. Toxicon 1:333–338. [CrossRef]

- Akhgari M, Abdollahi M, Kebryaeezadeh A et al (2003) Biochemical evidence for free radical-induced lipid peroxidation as a mechanism for subchronic toxicity of malathion in blood and liver of rats. Hum Exp Toxicol 22:205–211. [CrossRef]

- Tafazoli S, Spehar DD, O’Brien PJ (2005) Oxidative stress mediated idiosyncratic drug toxicity. Drug Metab Rev 37:311–325. [CrossRef]

- Cetiner M, Sener G, Sehirli AO et al (2005) Taurine protects against methotrexate-induced toxicity and inhibits leukocyte death. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 209:39–50. [CrossRef]

- Dervieux T, Brenner TL, Hon YY et al (2002) De novo purine synthesis inhibition and antileukemic effects of mercaptopurine alone or in combination with methotrexate in vivo. Blood 15: 1240–1247. [CrossRef]

- Minakami, H., H. Yamada, and S. Suzuki; Gestational thrombocytopenia and pregnancy-induced antithrombin deficiency: progenitors to the development of the HELLP syndrome and acute fatty liver of pregnancy. Semin Thromb hemost, 2002; 28, 515-518.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).