Submitted:

10 June 2025

Posted:

12 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

Research Objectives

2. Background and Related Work

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Description of the Data

- Chemical properties: calcium carbonate, cation exchange capacity (CEC), pH value, soil organic matter, sodium adsorption ratio, electrical conductivity

- Physical properties: bulk density, sand content, silt content, clay content, saturated hydraulic conductivity, rock fragments, soil texture

- Land use related properties: depth to restrictive layer, wind erodibility index, soil depth, hydrologic group, land capability class, wind erodibility group, soil order, soil temperature regime

Satellite Data

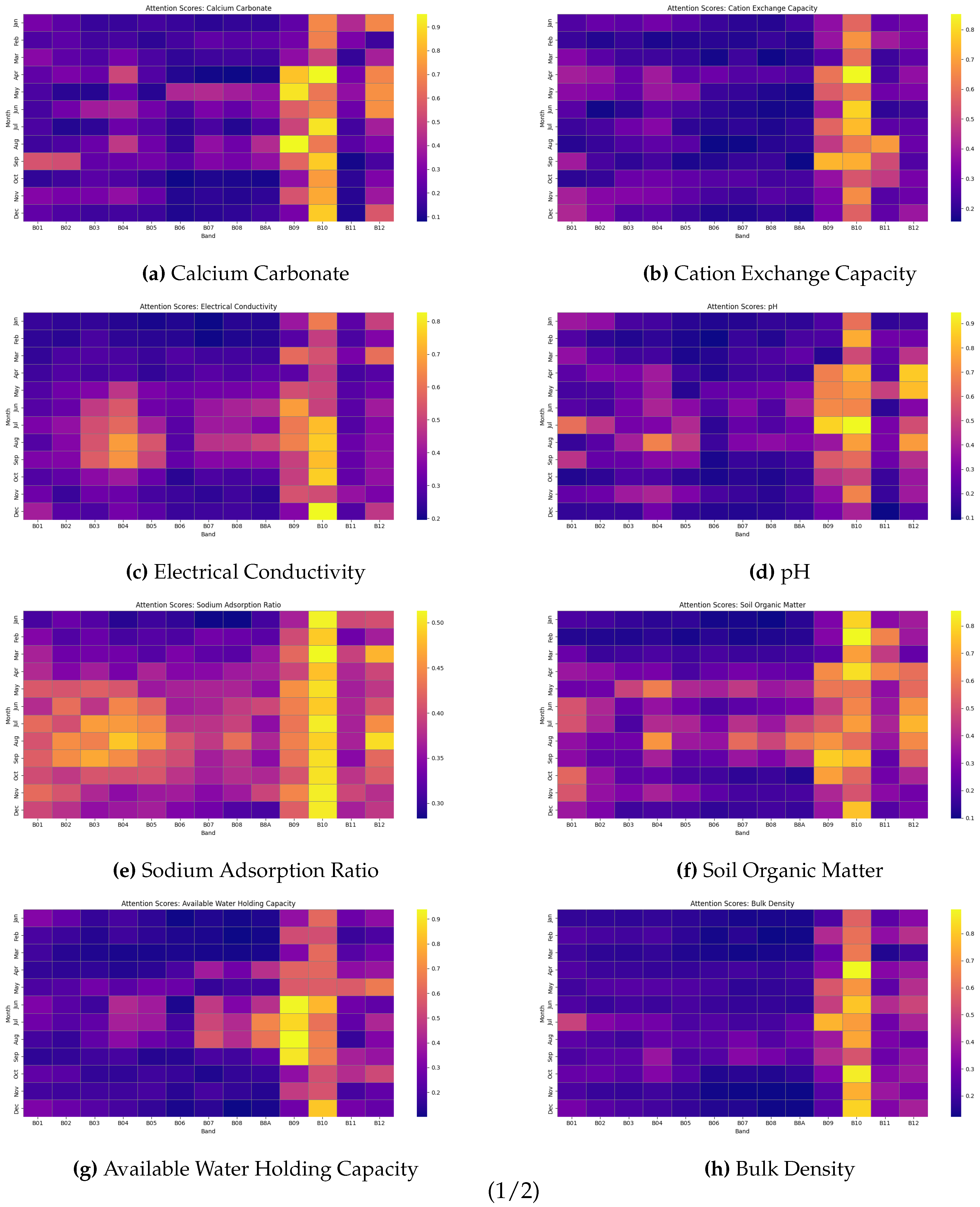

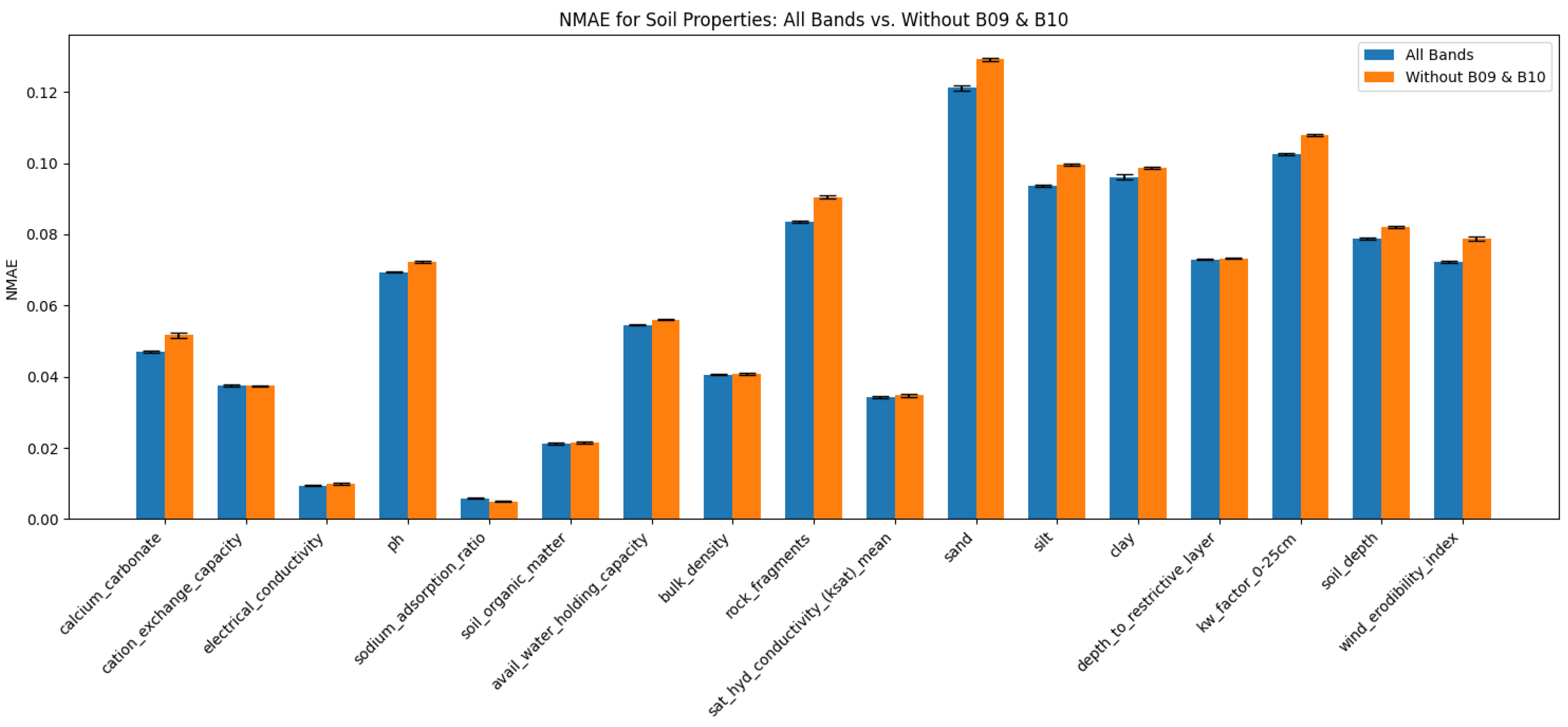

- Channels in the visible and near-infrared spectrum (B02–B08) are key for vegetation and soil status analysis.

- SWIR channels (B11 and B12) are useful for moisture detection and soil type classification.

- Red edge channels (B05, B06, B07) are especially valuable for monitoring vegetation stress.

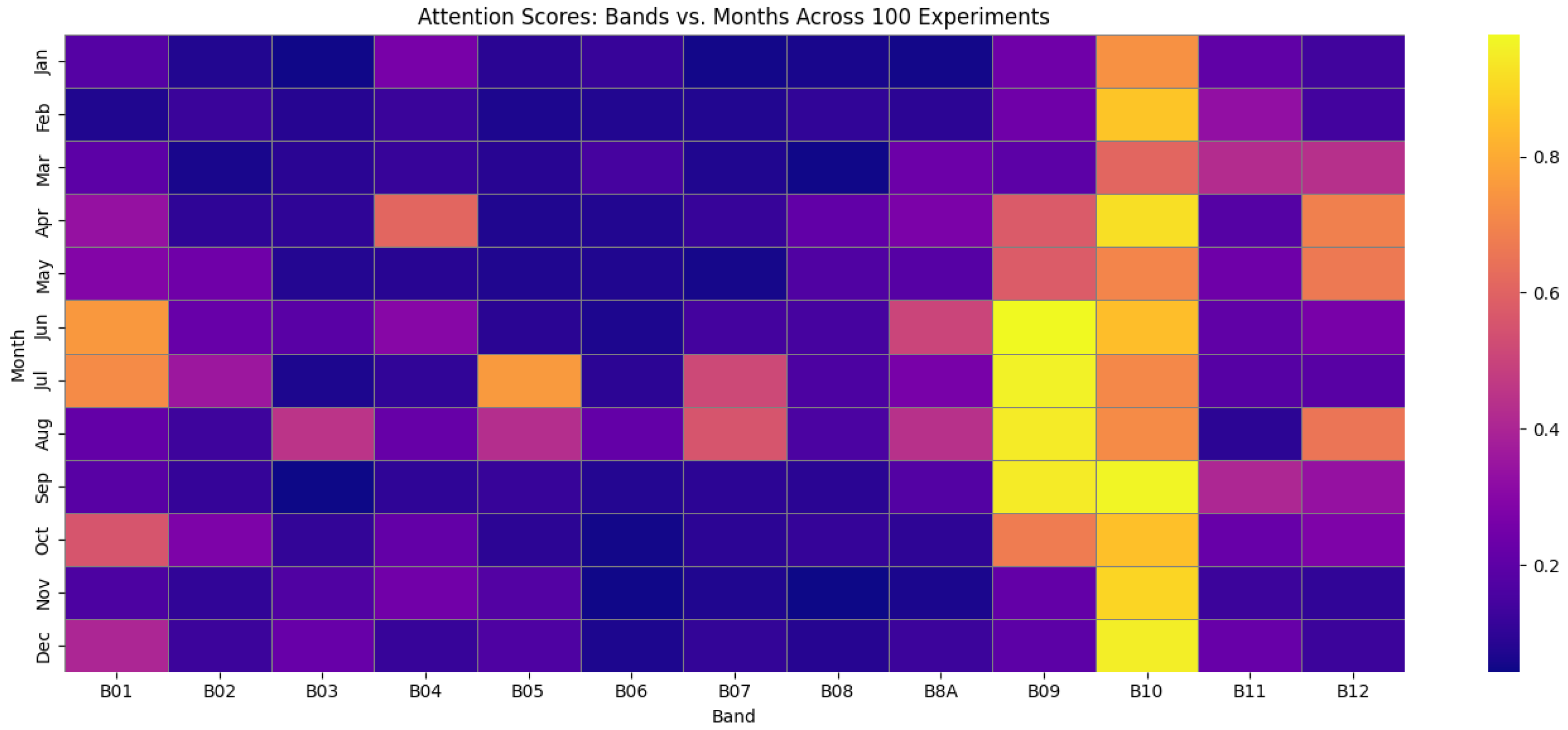

- B09 and B10 are most often used for atmospheric correction but may contain useful information for specific tasks.

3.2. Data Preprocessing

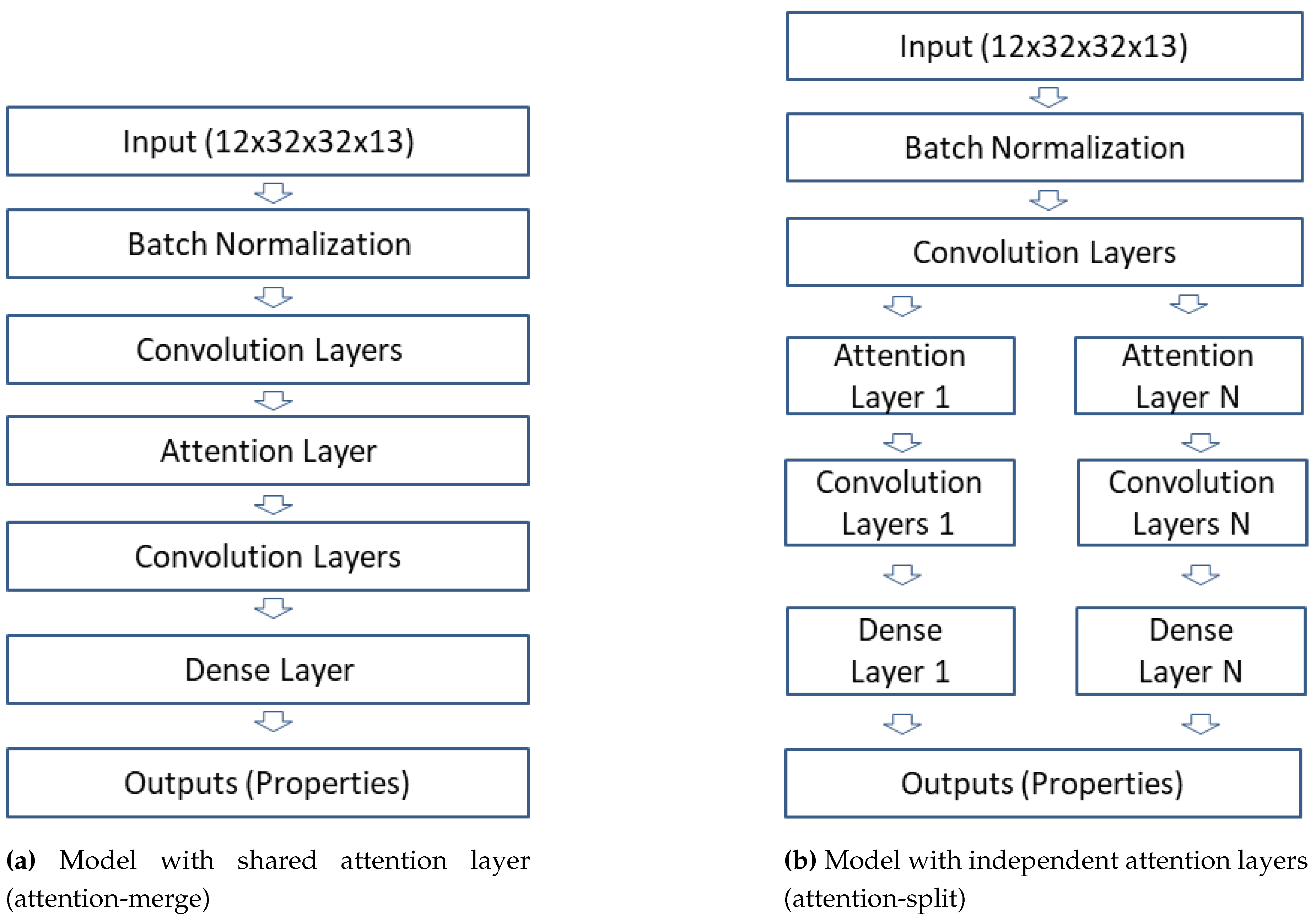

3.3. Model Architecture

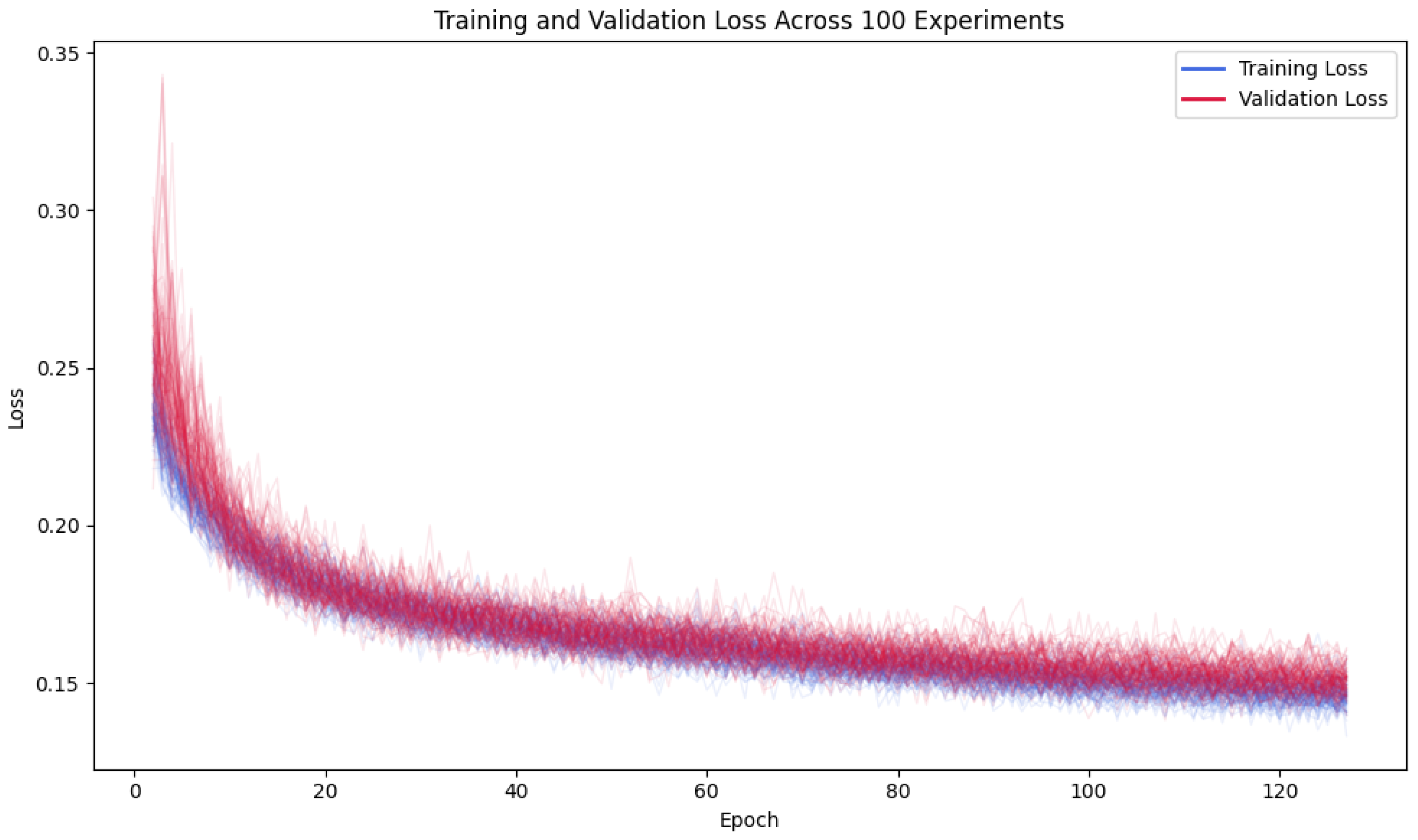

3.4. Model Training

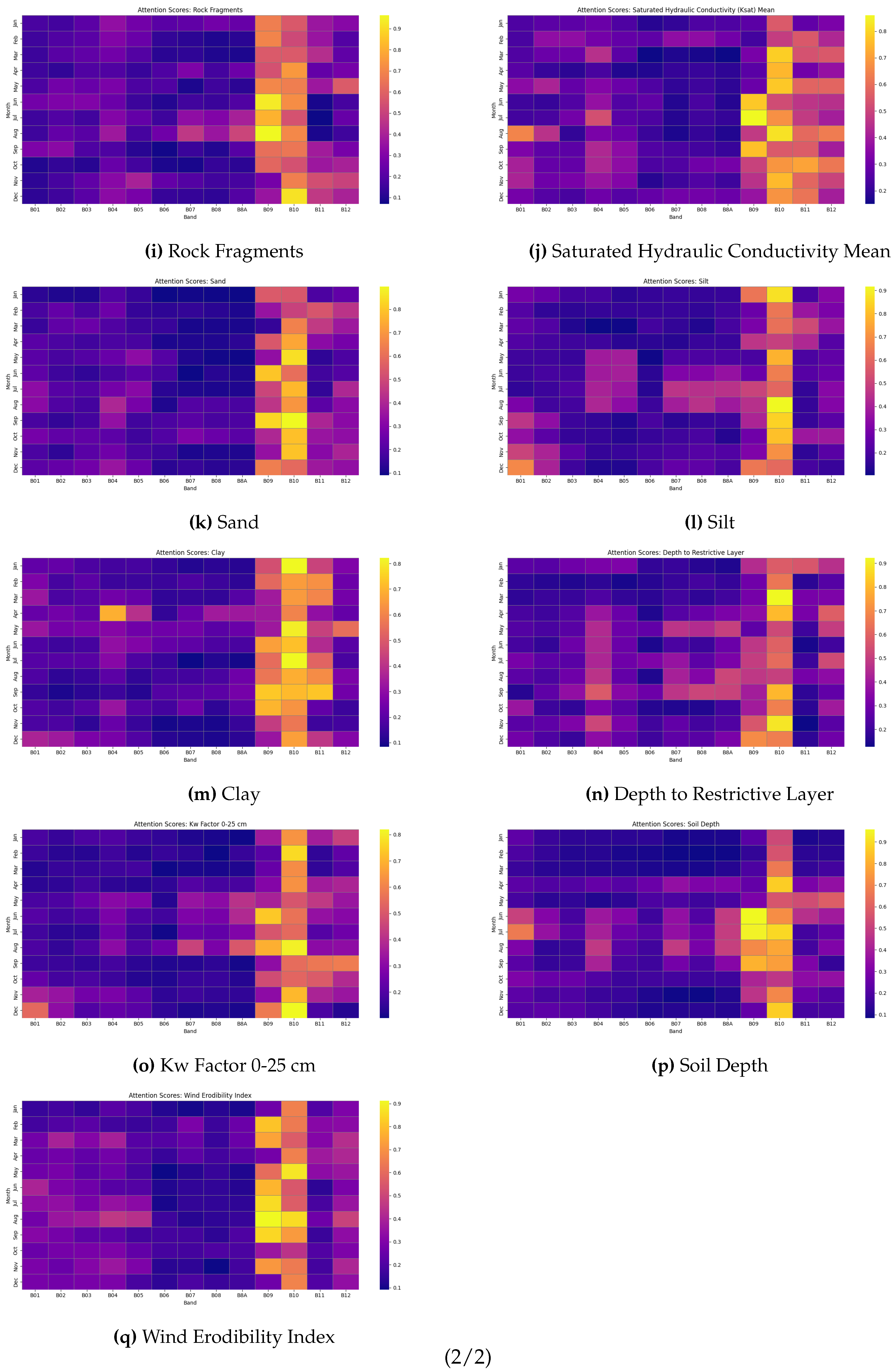

Note: The aim of the experimental design is not to achieve maximum model performance but to isolate and confirm the importance of individual input data. The number of epochs and training size were chosen to enable as much experiment replication and reliable statistical estimation of importance as possible, even at the cost of slightly compromised maximum accuracy metrics. The key value of this approach is the confirmation that the exclusion of attention-identified bands indeed leads to a reduction in the model’s ability to learn the appropriate relations, thus confirming their key role in the model.

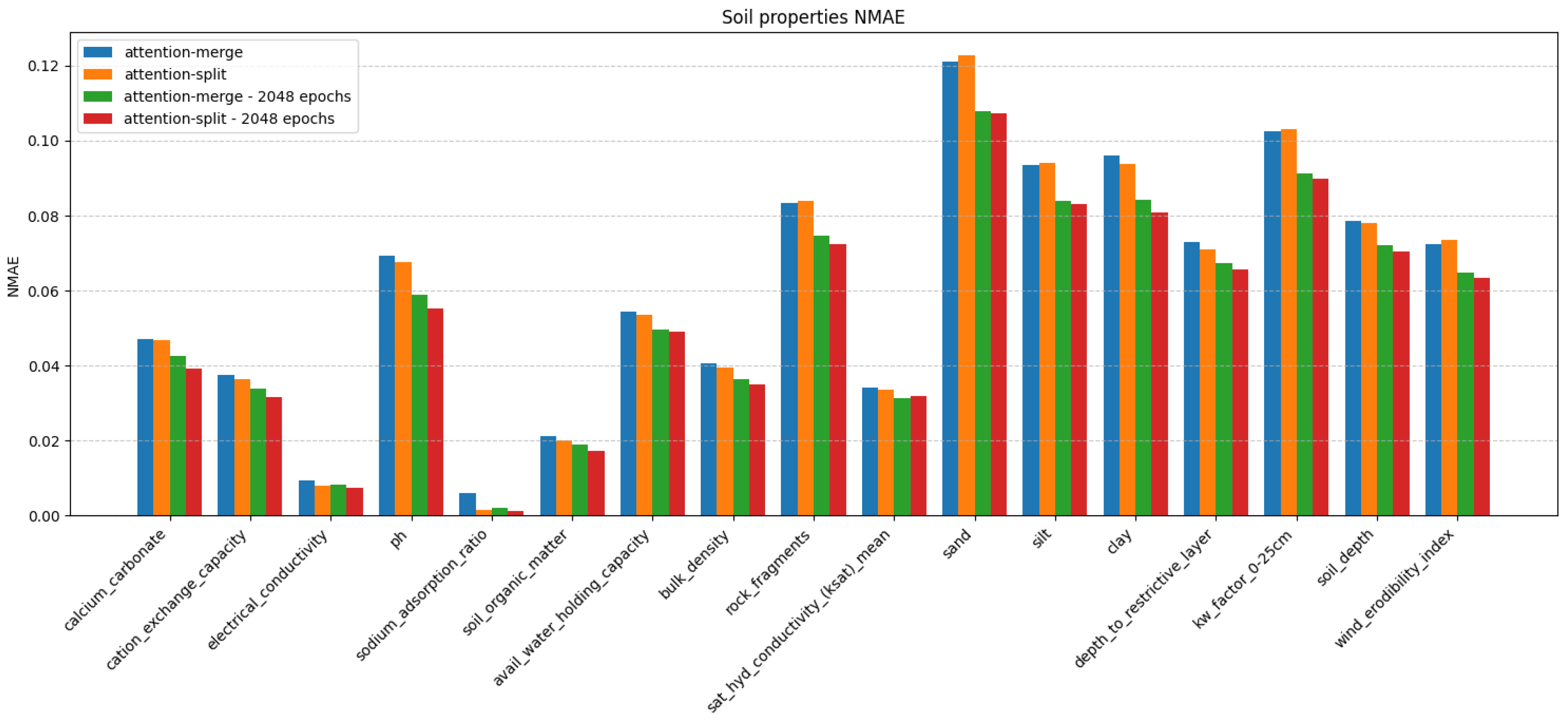

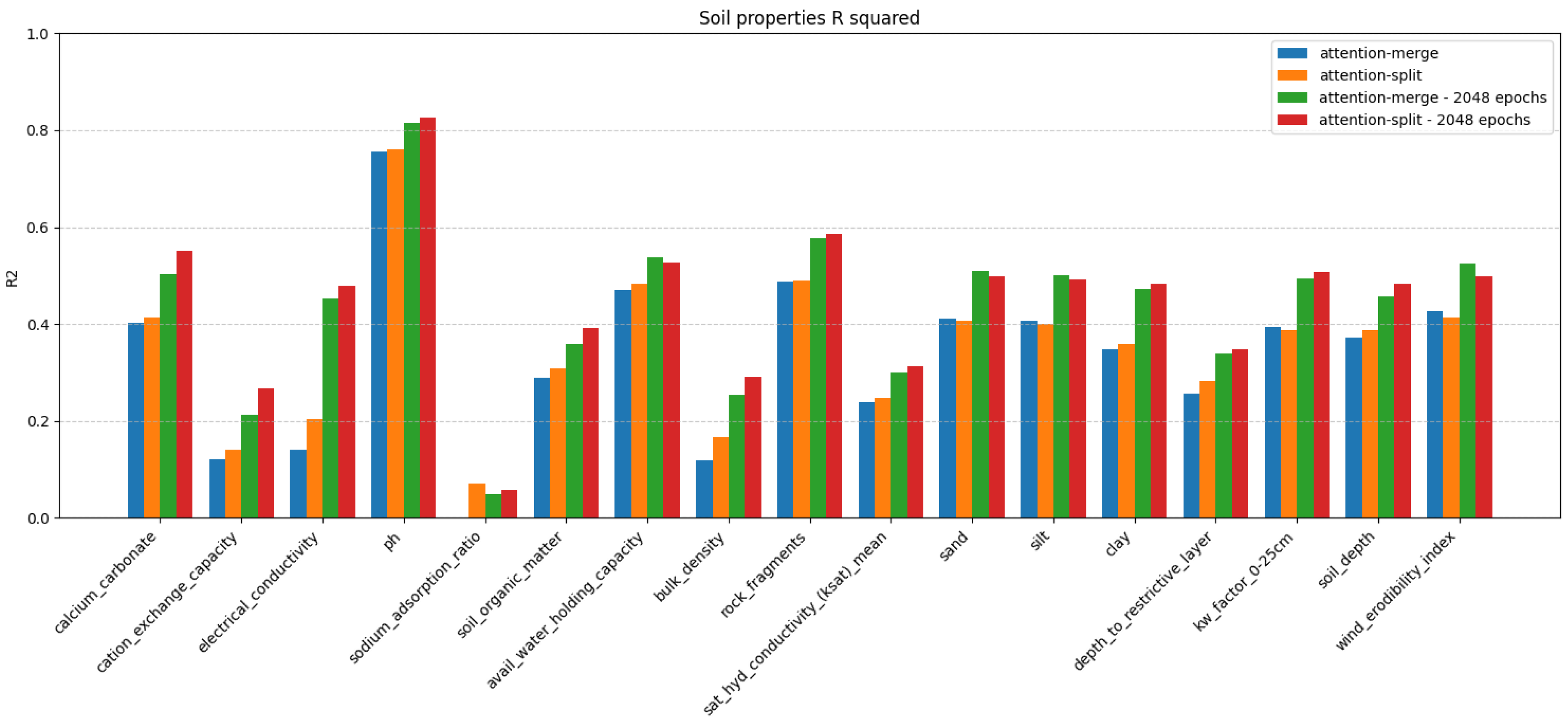

4. Results and Discussion

5. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Soil Properties: Detailed Description

- Calcium Carbonate (CaCO3): Amount of calcium carbonate in the soil. The presence of limestone is important for neutralizing soil acidity and determining overall fertility. Soils with high concentrations of CaCO3 are often alkaline, which can affect the availability of phosphorus and micronutrients.

- Cation Exchange Capacity (CEC): Measure of the soil’s ability to retain and exchange nutrient cations (e.g., Ca2+, Mg2+, K+, Na+). High CEC indicates a greater ability of the soil to retain nutrients and resistance to degradation.

- Electrical Conductivity (EC): Soil electrical conductivity, an indicator of total dissolved salts. High values indicate salinity that can endanger plant growth. EC is used to detect degradation and determine the need for reclamation.

- pH: Indicator of soil acidity or alkalinity. It affects nutrient availability, microorganism activity, and chemical processes in the soil. Optimal pH values (usually 6–7) allow maximum nutrient use.

- Sodium Adsorption Ratio (SAR): The ratio of sodium concentration to other cations in the soil. High SAR can cause degradation of soil structure, reduced permeability, and increased risk of erosion.

- Soil Organic Matter (SOM): The presence of organic matter (humus) increases fertility, water retention capacity, aggregate stability, and soil recovery.

- Available Water Holding Capacity (AWHC): The soil’s ability to retain water available to plants. Key for assessing crop drought resistance and irrigation planning.

- Bulk Density: Soil density (mass per unit volume). Lower values indicate loose and well-aerated soil, while high values may indicate compaction and poor water infiltration.

- Rock Fragments: Content of larger mineral particles and stones affects mechanical workability, water infiltration capacity, and overall soil productivity.

- Saturated Hydraulic Conductivity: The ability of the soil to conduct water when fully saturated. Key for drainage and prevention of excess water retention in the root zone.

- Sand, Silt, Clay: The granulometric composition of the soil determines soil texture (sandy, loamy, clayey) and capacity to retain water and nutrients.

- Depth To Restrictive Layer: Depth to a layer (e.g., rock, hard clay) that limits root growth and water flow. Greater depth allows better plant development.

- Kw Factor 0–25 cm: Wind erodibility factor for the surface soil layer, important for assessing the risk of erosion.

- Soil Depth: The total depth of the soil profile. Deeper soils usually have greater capacity for water and nutrients.

- Wind Erodibility Index: Index of soil susceptibility to wind erosion, important for planning protection and preserving the surface layer.

Appendix B. Sentinel-2 Bands: Technical Details and Applications

- B01 (443 nm, 60 m, Blue): This band is primarily intended for aerosol detection and estimation of atmospheric turbidity, which is crucial for correct interpretation of satellite data and precise atmospheric correction. Used for correction of reflected signals in water surfaces and vegetation. Due to low spatial resolution, used mainly as an auxiliary band in atmosphere.

- B02 (490 nm, 10 m, Blue): High spatial resolution enables detailed mapping of surface waters, detection and monitoring of clouds, snow, and ice cover. Extremely important in urban areas and for monitoring ecologically sensitive zones such as lakes and rivers. Often used for recognizing land-water boundaries.

- B03 (560 nm, 10 m, Green): The green band is key for basic vegetation analysis, including calculation of vegetation indices (NDVI, GNDVI). Enables detection of healthy and stressed plant communities. Also suitable for mapping land cover and monitoring terrain changes.

- B04 (665 nm, 10 m, Red): The most important band for calculating NDVI (Normalized Difference Vegetation Index), the standard for assessing photosynthetic activity and overall vegetation health. This band allows distinguishing between actively growing vegetation and non-vegetated soil, and is indispensable in agricultural and ecological monitoring.

- B05 (705 nm, 20 m, Red edge): The first red edge band in the Sentinel-2 series. Particularly sensitive to changes in chlorophyll content and can detect early signs of plant stress, invisible in classical visible bands. Used for monitoring crop phenological phases and detection of diseases or nutrient deficiencies.

- B06 (740 nm, 20 m, Red edge): Builds on B05 and allows even more precise assessment of changes in vegetation. Especially important for monitoring forest ecosystems, land degradation, and agricultural crops. Contributes to the analysis of vegetation cover structure and quality.

- B07 (783 nm, 20 m, Red edge): Used to assess total plant biomass, detect fires, and monitor vegetation regeneration after fires or degradation. Enables detailed mapping of permanent grasslands and forests. Often combined with B05 and B06 for advanced vegetation indices.

- B08 (842 nm, 10 m, Near-IR): The most important band for vegetation analysis. Near-IR reflects energy on healthy plants and enables very precise distinction of vegetation from non-vegetated surfaces (e.g., water, soil). Extremely useful for detection of soil moisture and flood areas, as well as for assessing vegetation cover density.

- B8A (865 nm, 20 m, Narrow Near-IR): This band enables more detailed segmentation of vegetation and is used for monitoring boundaries between vegetation and water surfaces, as well as for assessing changes in wetlands and coastal zones. Combined with B08 gives even more precise results in mapping biological and hydromorphological changes.

- B09 (945 nm, 60 m, Water vapor): Specific band designed for detection of water vapor content in the atmosphere. Essential for correction of atmospheric influence in the analysis of reflected signals, which increases the accuracy of multispectral analyses of soil and vegetation.

- B10 (1375 nm, 60 m, SWIR–Cirrus): Enables detection of cirrus clouds and assessment of the influence of high, thin clouds on image quality. Helps in automatic selection and filtering of scenes with undesirable atmospheric conditions, which is crucial for obtaining reliable data in time series.

- B11 (1610 nm, 20 m, SWIR): Shortwave infrared band used for analysis of soil and vegetation moisture, as well as for identification of mineral surface composition. Important for classification of soil types, detection of degradation, and determination of clay or sand content in soil.

- B12 (2190 nm, 20 m, SWIR): The furthest band in the SWIR domain of Sentinel-2 mission, used for estimation of total surface moisture, land cover classification, detection of forest and surface fires, as well as erosion and land degradation. Enables detection of changes not visible in visible or NIR spectrum.

References

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Soil is a non-renewable resource, 2015. Accessed: 2025-05-28.

- University of Minnesota Extension. Five factors of soil formation, 2025. Accessed: 2025-05-28.

- Natural Resources Conservation Service, USDA. Soil Health, 2025. Accessed: 2025-05-28.

- Fausak, L.K.; Bridson, N.; Diaz-Osorio, F.; Jassal, R.S.; Lavkulich, L.M. Soil health–a perspective. Frontiers in Soil Science 2024, 4, 1462428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derpsch, R.; Kassam, A.; Reicosky, D.; Friedrich, T.; Calegari, A.; Basch, G.; Gonzalez-Sanchez, E.; dos Santos, D.R. Nature’s laws of declining soil productivity and Conservation Agriculture. Soil Security 2024, 14, 100127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NC State Extension. Soil Physical Health, 2025. Accessed: 2025-05-28.

- Noble Research Institute. Soil and Water Relationships, 2022. Accessed: 2025-05-28.

- Needelman, B.A. Soil: The Foundation of Agriculture. Nature Education Knowledge 2013, 4, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Li, T.; Cui, L.; Filipović, V.; Tang, C.; Lai, Y.; Wehr, B.; Song, X.; Chapman, S.; Liu, H.; Dalal, R.C.; et al. From soil health to agricultural productivity: The critical role of soil constraint management. Catena 2025, 250, 108776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longepierre, M.; Widmer, F.; Hartmann, M. Limited resilience of the soil microbiome to mechanical compaction within four growing seasons of agricultural management. ISME Communications 2021, 1, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shahane, A.A.; Shivay, Y.S. Soil health and its improvement through novel agronomic and innovative approaches. Frontiers in Agronomy 2021, 3, 680456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopittke, P.M.; Menzies, N.W.; Wang, P.; McKenna, B.A.; Lombi, E. Soil and the intensification of agriculture for global food security. Environment international 2019, 132, 105078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliveira, R.C.d.; Silva, R.D.d.S.e. Artificial intelligence in agriculture: benefits, challenges, and trends. Applied Sciences 2023, 13, 7405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hrast Essenfelder, A.; Toreti, A.; Seguini, L. Expert-driven explainable artificial intelligence models can detect multiple climate hazards relevant for agriculture. Communications Earth & Environment 2025, 6, 207. [Google Scholar]

- Astolfi, D.; De Caro, F.; Vaccaro, A. Recent advances in the use of explainable artificial intelligence techniques for wind turbine systems condition monitoring. Electronics 2023, 12, 3509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novielli, P.; Magarelli, M.; Romano, D.; Di Bitonto, P.; Stellacci, A.M.; Monaco, A.; Amoroso, N.; Bellotti, R.; Tangaro, S. Leveraging explainable AI to predict soil respiration sensitivity and its drivers for climate change mitigation. Scientific Reports 2025, 15, 12527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abekoon, T.; Sajindra, H.; Rathnayake, N.; Ekanayake, I.U.; Jayakody, A.; Rathnayake, U. A novel application with explainable machine learning (SHAP and LIME) to predict soil N, P, and K nutrient content in cabbage cultivation. Smart Agricultural Technology 2025, 11, 100879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakhani, N.; Taghizadeh-Mehrjardi, R.; Omarzadeh, D.; Ryo, M.; Heiden, U.; Scholten, T. Towards explainable AI: interpreting soil organic carbon prediction models using a learning-based explanation method. European Journal of Soil Science 2025, 76, e70071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beucher, A.; Rasmussen, C.B.; Moeslund, T.B.; Greve, M.H. Interpretation of convolutional neural networks for acid sulfate soil classification. Frontiers in Environmental Science 2022, 9, 809995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohan, R.J.; Rayanoothala, P.S.; Sree, R.P. Next-gen agriculture: integrating AI and XAI for precision crop yield predictions. Frontiers in Plant Science 2025, 15, 1451607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shams, M.Y.; Gamel, S.A.; Talaat, F.M. Enhancing crop recommendation systems with explainable artificial intelligence: a study on agricultural decision-making. Neural Computing and Applications 2024, 36, 5695–5714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, Q.; Wang, L.; Li, Q. Soil temperature prediction based on explainable artificial intelligence and LSTM. Frontiers in Environmental Science 2024, 12, 1426942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turgut, Ö.; Kök, İ.; Özdemir, S. AgroXAI: Explainable AI-Driven Crop Recommendation System for Agriculture 4.0. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Conference on Big Data (BigData). IEEE; 2024; pp. 7208–7217. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, C.; Dhillon, J.; Huang, Y.; Reddy, K. Explainable machine learning models for corn yield prediction using UAV multispectral data. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 2025, 231, 109990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walkinshaw, M.; O’Geen, A.; Beaudette, D. Soil properties. California Soil Resource Lab, 1 Oct 2022, 2023.

| No. | Property Name | Category | Data Type | Used |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Calcium Carbonate | Chemical | Numeric | ✓ |

| 2 | Cation Exchange Capacity | Chemical | Numeric | ✓ |

| 3 | Cation Exchange Capacity 0-5 cm | Chemical | Numeric | |

| 4 | Cation Exchange Capacity 0-25 cm | Chemical | Numeric | |

| 5 | Cation Exchange Capacity 0-50 cm | Chemical | Numeric | |

| 6 | Electrical Conductivity | Chemical | Numeric | ✓ |

| 7 | Electrical Conductivity 0-5 cm | Chemical | Numeric | |

| 8 | Electrical Conductivity 0-25 cm | Chemical | Numeric | |

| 9 | PH | Chemical | Numeric | ✓ |

| 10 | PH 0-5 cm | Chemical | Numeric | |

| 11 | PH 0-25 cm | Chemical | Numeric | |

| 12 | PH 25-50 cm | Chemical | Numeric | |

| 13 | PH 30-60 cm | Chemical | Numeric | |

| 14 | Sodium Adsorption Ratio | Chemical | Numeric | ✓ |

| 15 | Soil Organic Matter | Chemical | Numeric | ✓ |

| 16 | Soil Organic Matter Max | Chemical | Numeric | |

| 17 | Available Water Holding Capacity | Physical | Numeric | ✓ |

| 18 | Available Water Holding Capacity 0-25 cm | Physical | Numeric | |

| 19 | Available Water Holding Capacity 0-50 cm | Physical | Numeric | |

| 20 | Bulk Density | Physical | Numeric | ✓ |

| 21 | Drainage Class | Physical | Categorical | |

| 22 | Rock Fragments | Physical | Numeric | ✓ |

| 23 | Saturated Hydraulic Conductivity Mean | Physical | Numeric | ✓ |

| 24 | Saturated Hydraulic Conductivity Min | Physical | Numeric | |

| 25 | Saturated Hydraulic Conductivity Max | Physical | Numeric | |

| 26 | Saturated Hydraulic Conductivity 0-5 cm | Physical | Numeric | |

| 27 | Soil Texture 0-5 cm | Physical | Categorical | |

| 28 | Soil Texture 0-25 cm | Physical | Categorical | |

| 29 | Soil Texture 25-50 cm | Physical | Categorical | |

| 30 | Sand | Physical | Numeric | ✓ |

| 31 | Sand 0-5 cm | Physical | Numeric | |

| 32 | Sand 0-25 cm | Physical | Numeric | |

| 33 | Sand 25-50 cm | Physical | Numeric | |

| 34 | Sand 30-60 cm | Physical | Numeric | |

| 35 | Silt | Physical | Numeric | ✓ |

| 36 | Silt 0-5 cm | Physical | Numeric | |

| 37 | Silt 0-25 cm | Physical | Numeric | |

| 38 | Silt 25-50 cm | Physical | Numeric | |

| 39 | Silt 30-60 cm | Physical | Numeric | |

| 40 | Clay | Physical | Numeric | ✓ |

| 41 | Clay 0-5 cm | Physical | Numeric | |

| 42 | Clay 0-25 cm | Physical | Numeric | |

| 43 | Clay 25-50 cm | Physical | Numeric | |

| 44 | Clay 30-60 cm | Physical | Numeric | |

| 45 | Depth To Restrictive Layer | Land Use | Numeric | ✓ |

| 46 | Hydrologic Group | Land Use | Categorical | |

| 47 | Kw Factor 0-25 cm | Land Use | Numeric | ✓ |

| 48 | Land Capability Class Non Irrigated | Land Use | Categorical | |

| 49 | Land Capability Class Irrigated | Land Use | Categorical | |

| 50 | Soil Depth | Land Use | Numeric | ✓ |

| 51 | Soil Order | Land Use | Categorical | |

| 52 | Soil Temperature Regime | Land Use | Categorical | |

| 53 | Wind Erodibility Group | Land Use | Categorical | |

| 54 | Wind Erodibility Index | Land Use | Numeric | ✓ |

| 55 | Survey Type | Land Use | Categorical |

| No. | Band | Central wavelength (nm) | Spatial resolution (m) | Spectral type |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | B01 | 443 | 60 | Blue |

| 2 | B02 | 490 | 10 | Blue |

| 3 | B03 | 560 | 10 | Green |

| 4 | B04 | 665 | 10 | Red |

| 5 | B05 | 705 | 20 | Red edge |

| 6 | B06 | 740 | 20 | Red edge |

| 7 | B07 | 783 | 20 | Red edge |

| 8 | B08 | 842 | 10 | Near-IR |

| 9 | B8A | 865 | 20 | Narrow Near-IR |

| 10 | B09 | 945 | 60 | Water vapor |

| 11 | B10 | 1375 | 60 | SWIR–Cirrus |

| 12 | B11 | 1610 | 20 | SWIR |

| 13 | B12 | 2190 | 20 | SWIR |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).