Submitted:

05 June 2025

Posted:

11 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- Determine the rate and suitability of referrals and subsequent clinical impact.

- Quantify medicine optimization for patients who underwent medicine review.

- Explore patient experiences and feelings around referrals and their medicines.

- Explore ambulance healthcare professionals’ perceptions of the value of referral.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Context

2.2. Improvement Initiative

| Inclusion | Exclusion |

| Aged ≥ 65 | Aged < 65 |

| Face-to-face assessment by an ambulance clinician | No face-to-face contact |

| Primary reason for ambulance attendance was fall | Patient conveyed to hospital |

| Taking ≥ 1 medicine (prescribed or otherwise) | Not taking medicines |

| Fall in a residential address | Fall in public or patient is a care/nursing home resident |

| Registered with a local confederation GP | Registered with a GP outside the confederation |

| Non-urgent referral made | No referral made |

2.3. Service Evaluation

2.4. Stakeholder Surveys

2.4.1. Patient Survey

2.4.2. Ambulance Clinician Survey

2.5. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

3.1. Referral Rate, Suitability, and Clinical Impact

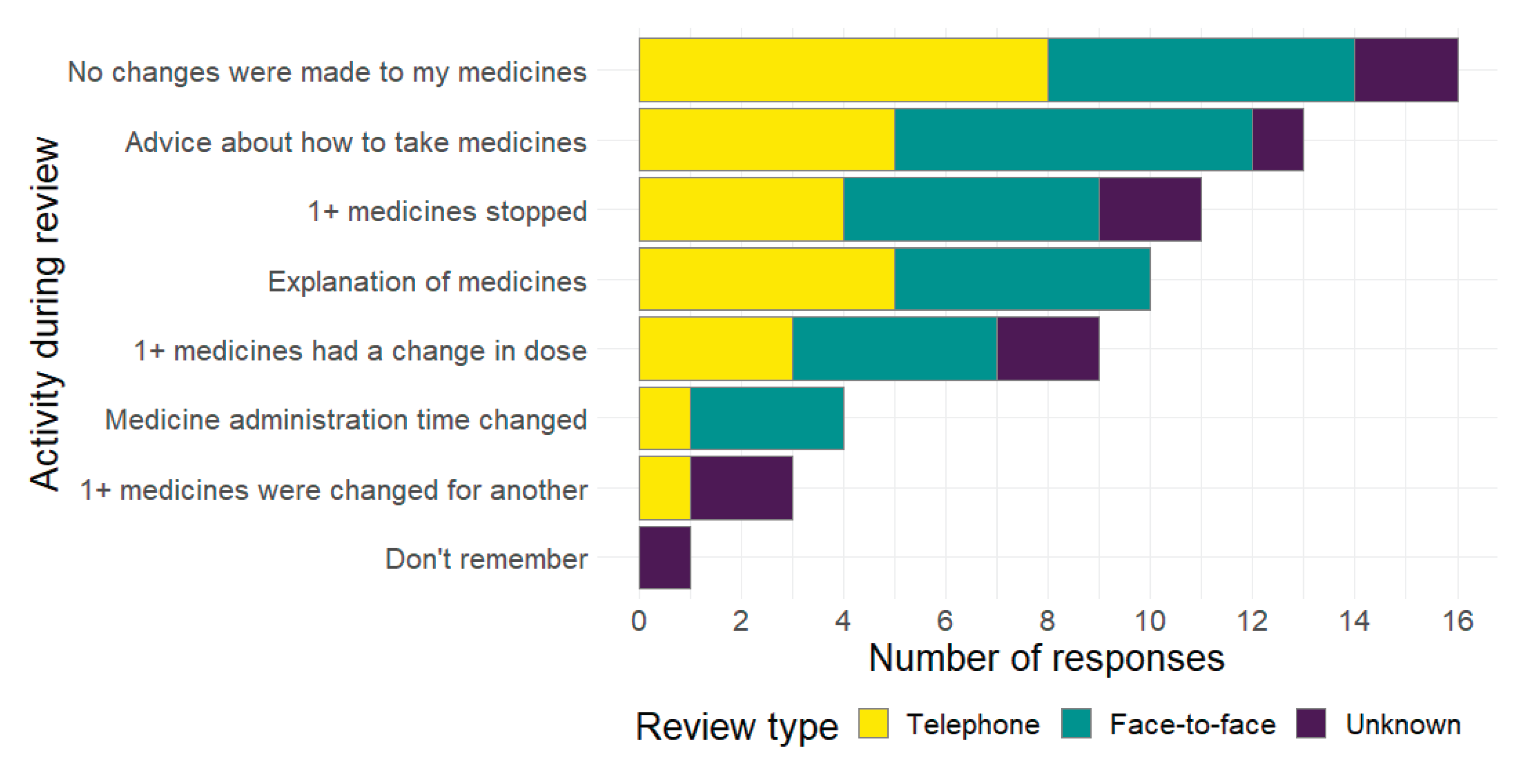

3.2. Medicine Optimisation

3.3. Patient Experiences and Feelings

3.4. Ambulance Healthcare Professional Perceptions

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations

4.2. Future research

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SQUIRE | Standards for Quality Improvement Reporting Excellence (2.0) |

| CROSS | Checklist for Reporting of Survey Studies |

| CI | Confidence Interval |

| OR | Odds Ratio |

| IQR | Interquartile Range |

References

- Stevens, J., J. Mahoney, and H. Ehrenreich. "Circumstances and Outcomes of Falls among High Risk Community-Dwelling Older Adults." Injury Epidemiology 1 (2014). [CrossRef]

- Jørstad, E., K. Hauer, C. Becker, and S. Lamb. "Measuring the Psychological Outcomes of Falling: A Systematic Review." Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 53, no. 3 (2005): 501-10. [CrossRef]

- Schoene, D., C. Heller, Y. Aung, C. Sieber, W. Kemmler, and E. Freiberger. "A Systematic Review on the Influence of Fear of Falling on Quality of Life in Older People: Is There a Role for Falls?" Clinical Interventions in Aging 14 (2019): 701-19. [CrossRef]

- Hollinghurst, R., N. Williams, R. Pedrick-Case, L. North, S. Long, R. Fry, and J. Hollinghurst. "Annual Risk of Falls Resulting in Emergency Department and Hospital Attendances for Older People: An Observational Study of 781,081 Individuals Living in Wales (United Kingdom) Including Deprivation, Frailty and Dementia Diagnoses between 2010 and 2020." Age and Ageing 51, no. 8 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Public Health England. "Falls and Fracture Consensus Statement: Supporting Commissioning for Prevention." London, 2017.

- O'Cathain, A., E. Knowles, L. Bishop-Edwards, J. Coster, A. Crum, R. Jacques, C. James, R. Lawson, M. Marsh, R. O'Hara, A. Siriwardena, T. Stone, J. Turner, and J. Williams. "Understanding Variation in Ambulance Service Non-Conveyance Rates: A Mixed Methods Study." Health Services and Delivery Research 6, no. 19 (2018): 45. [CrossRef]

- Joint Royal Colleges Ambulance Liaison Committee (JRCALC), and Association of Ambulance Chief Executives (AACE). "Falls in Older Adults." In Jrcalc Clinical Guidelines. Bridgwater: Class Publishing Ltd, 2022.

- Dhalwani, N., R. Fahami, H. Sathanapally, S. Seidu, M. Davie, and K. Khunti. "Association between Polypharmacy and Falls in Older Adults: A Longitudinal Study from England." BMJ Open 16, no. 7 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Montero-Odasso, M., N. van der Velde, F. Martin, M. Petrovic, M. Tan, J. Ryg, S. Aguilar-Navarro, N. Alexander, C. Becker, H. Blain, R. Bourke, I. Cameron, R. Camicioli, L. Clemson, J. Close, K. Delbaere, L. Duan, G. Duque, S. Dyer, E. Freiberger, D. Ganz, F. Gómez, J. Hausdorff, D. Hogan, S. Hunter, J. Jauregui, N. Kamkar, R. Kenny, S. Lamb, N. Latham, L. Lipsitz, T. Liu-Ambrose, P. Logan, S. Lord, L. Mallet, D. Marsh, K. Milisen, R. Moctezuma-Gallegos, M. Morris, A. Nieuwboer, M. Perracini, F. Pieruccini-Faria, A. Pighills, C. Said, E. Sejdic, C. Sherrington, D. Skelton, S. Dsouza, M. Speechley, S. Stark, C. Todd, B. Troen, T. van der Cammen, J. Verghese, E. Vlaeyen, J. Watt, T. Masud, and the Task Force on Global Guidelines for Falls in Older Adults. "World Guidelines for Falls Prevention and Management for Older Adults: A Global Initiative." Age and Ageing 51, no. 9 (2022). [CrossRef]

- National Institute of Health and Care Excellence. "Falls: Assessment and Prevention in Older People and in People 50 and over at Higher Risk [Ng249]." 2025.

- Smith, H. "Role of Medicines Management in Preventing Falls in Older People." Nursing Older People (2022). [CrossRef]

- Crawford, P., R. Plumb, P. Burns, S. Flanagan, and C. Parsons. "A Quantitative Study on the Impact of a Community Falls Pharmacist Role, on Medicines Optimisation in Older People at Risk of Falls." BMC Geriatrics 24 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Curtin, D., E. Jennings, R. Daunt, S. Curtin, M. Randles, P. Gallagher, and D. O'Mahony. "Deprescribing in Older People Approaching End of Life: A Randomized Controlled Trial Using Stoppfrail Criteria." Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 68, no. 4 (2019): 762-69. [CrossRef]

- Marvin, V., E. Ward, A. Poots, K. Heard, A. Rajagopalan, and B. Jubraj. "Deprescribing Medicines in the Acute Setting to Reduce the Risk of Falls." European Journal of Hospital Pharmacy 24, no. 1 (2017): 10-15. [CrossRef]

- Wright, D., R. Holland, D. Alldred, C. Bond, C. Hughes, G. Barton, F. Poland, L. Shepstone, A. Arthur, L. Birt, J. Blacklock, A. Blyth, S. Cheilari, A. Daffu-O'Reilly, L. Dalgarno, D. Desborough, J. Ford, K. Grant, J. Gray, C. Handford, B. Harry, H. Hill, J. Inch, P. Myint, N. Norris, M. Spargo, V. Maskrey, D. Turner, L. Watts, and A. Zermansky. The Care Home Independent Pharmacist Prescriber Study (Chipps): Development and Implementation of an Rct to Estimate Safety, Effectiveness and Cost-Effectiveness, Programme Grants for Applied Research. Southampton: National Institute for Health and Care Research, 2023.

- Ming, Y., A. Zecevic, S. Hunter, W. Miao, and R. Tirona. "Medication Review in Preventing Older Adults’ Fall-Related Injury: A Systematic Review & Meta-Analysis." Canadian Geriatrics Journal 24, no. 3 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Zermansky, A., D. Alldred, D. Petty, D. Raynor, N. Freemantle, J. Eastaugh, and P. Bowie. "Clinical Medication Review by a Pharmacist of Elderly People Living in Care Homes—Randomised Controlled Trial." Age and Ageing 35, no. 6 (2006): 586-91. [CrossRef]

- Pit, S., J. Byles, D. Henry, L. Holt, V. Hansen, and D. Bowman. "A Quality Use of Medicines Program for General Practitioners and Older People: A Cluster Randomised Controlled Trial." Medical Journal of Australia 187, no. 1 (2007): 23-30. [CrossRef]

- Phelan, E., B. Williamson, B. Balderson, A. Cook, A. Piccorelli, M. Fujii, K. Nakata, V. Graham, M. Theis, J. Turner, C. Tannenbaum, and S. Gray. "Reducing Central Nervous System–Active Medications to Prevent Falls and Injuries among Older Adults: A Cluster Randomized Clinical Trial." JAMA Network Open 7, no. 7 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Seppala, L., N. Kamkar, E. van Poelgeest, K. Thomsen, J. Daams, J. Ryg, T. Masud, M. Montero-Odasso, S. Hartikainen, M. Petrovic, and N. van der Velde. "Medication Reviews and Deprescribing as a Single Intervention in Falls Prevention: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis." Age and Ageing 51, no. 9 (2022): afac191. [CrossRef]

- Gillespie, L., M. Robertson, W. Gillespie, C. Sherrington, S. Gates, L. Clemson, and S. Lamb. "Interventions for Preventing Falls in Older People Living in the Community." Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, no. 9 (2012). [CrossRef]

- Cameron, I., S. Dyer, C. Panagoda, G. Murray, K. Hill, R. Cumming, and N. Kerse. "Interventions for Preventing Falls in Older People in Care Facilities and Hospitals." Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, no. 9 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Almutairi, H., A. Stafford, C. Etherton-Beer, and L. Flicker. "Optimisation of Medications Used in Residential Aged Care Facilities: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomised Controlled Trials." BMC Geriatrics 20, no. 236 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Lee, J., A. Negm, R. Peters, E. Wong, and A. Holrbook. "Deprescribing Fall-Risk Increasing Drugs (Frids) for the Prevention of Falls and Fall-Related Complications: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis." BMJ Open 11, no. 2 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Acquisto, N., J. Cushman, A. Rice, and C. Edwards. "Collaboration by Emergency Medicine Pharmacists and Prehospital Services Providers." American Journal of Health-System Pharmacy 77, no. 12 (2020): 918-21. [CrossRef]

- Crockett, B., K. Jasiak, T. Walroth, K. Degenkolb, A. Stevens, and C. Jung. "Pharmacist Involvement in a Community Paramedicine Team." Journal of Pharmacy Science 30, no. 2 (2016): 223-28. [CrossRef]

- Hayball, P., R. Elliot, and S. Morris. "Ambulance Pharmacist – Why Haven't We Thought of This Role Earlier?" Pharmacy Practice and Research 45, no. 3 (2015): 318-21. [CrossRef]

- Ogrinc, G., L. Davies, D. Goodman, P. Batalden, F. Davidoff, and D. Stevens. "Squire 2.0 (Standards for Quality Improvement Reporting Excellence): Revised Publication Guidelines from a Detailed Consensus Process " BMJ Quality & Safety 25, no. 12 (2016): 986-92. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A., N. T. Tran Minh Duc, T. Luu Lam Thang, N. Hai Nam, S. J. Ng, K. Said Abbas, N. Tien Huy, A. Marušić, C. L. Paul, J. Kwok, J. Karbwang, C. de Waure, F. J. Drummond, Y. Kizawa, E. Taal, J. Vermeulen, G. H. M. Lee, A. Gyedu, K. Gia To, M. L. Verra, É. M. Jacqz-Aigrain, W. K. G. Leclercq, S. T. Salminen, C. D. Sherbourne, B. Mintzes, S. Lozano, U. S. Tran, M. Matsui, and M. Karamouzian. "A Consensus-Based Checklist for Reporting of Survey Studies (Cross)." Journal of General Internal Medicine 36, no. 10 (2021): 3179-87. [CrossRef]

- PrescQIPP. "Care Homes - Medication and Falls." 4-8, 2014.

- Agresti, A. Analysis of Ordinal Categorical Data. 2nd ed, Wiley Series in Probability and Statistics. Hoboken: Wiley, 2010.

- Harrell, F. Regression Modeling Strategies: With Application to Linear Models Logistic Regression, and Survival Analysis, Springer Series in Statistics. New York: Springer-Verlag, 2001.

- Julious, S., M. Campbell, and D. Altman. "Estimating Sample Sizes for Continuous, Binary, and Ordinal Outcomes in Paired Comparisons: Practical Hints." Journal of Biopharmaceutical Statistics 9, no. 2 (1999): 241-51. [CrossRef]

- Nymoen, L., T. Flatebø, T. Moger, E. Øie, E. Molden, and K. Viktil. "Impact of Systematic Medication Review in Emergency Department on Patients' Post-Discharge Outcomes - a Randomised Controlled Clinical Trial." PLoS ONE 17, no. 9 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Mikolaizak, A., S. Lord, A. Tiedeman, P. Simpson, G. Caplan, J. Bendall, K. Howard, L. Webster, N. Payne, S. Hamilton, J. Lo, E. Ramsay, S. O'Rourke, L. Roylance, and J. Close. "A Multidisciplinary Intervention to Prevent Subsequent Falls and Halth Service Use Following Fall-Related Paramedic Care: A Randomised Controlled Trial." Age and Ageing 46 (2017): 200-08. [CrossRef]

- Al Bulushi, S., T. McIntosh, A. Grant, D. Stewart, and S. Cunningham. "Implementation Frameworks for Polypharmacy Management within Healthcare Organisations: A Scoping Review." International Journal of Clinical Pharmacy 45 (2023): 343-54. [CrossRef]

- Seppala, L., E. van de Glind, J. Daams, K. Ploegmakers, M. de Vries, A. Wermelink, and N. van der Velde. "Fall-Risk-Increasing Drugs: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis: Iii. Others." Journal of the American Medical Directors Association 19, no. 4 (2018): 372e.1-72.e8. [CrossRef]

- Seppala, L., M. Petrovic, J. Ryg, G. Bahat, E. Topinkova, K. Szczerbińska, T. van der Cammen, S. Hartikainen, B. Ilhan, F. Landi, Y. Morrissey, A. Mair, M. Gutiérrez-Valencia, M. Emmelot-Vonk, M. Mora, M. Denkinger, P. Crome, S. Jackson, A. Correa-Pérez, W. Knol, G. Soulis, A. Gudmundsson, G. Ziere, M. Wehling, D. O'Mahony, A. Cherubini, and N. van der Velde. "Stoppfall (Screening Tool of Older Persons Prescriptions in Older Adults with High Fall Risk): A Delphi Study by the Eugms Task and Finish Group on Fall-Risk-Increasing Drugs." Age and Ageing 50, no. 4 (2021): 1189-99. [CrossRef]

- Alićehajić-Bečić, Ð., and H. Smith. "Medicines and Falls." National Falls Prevention Coordination Group, 2023.

- Campbell, A., M. Robertson, M. Gardner, R. Norton, and D. Buchner. "Psychotropic Medication Withdrawal and a Home-Based Exercise Program to Prevent Falls: A Randomized, Controlled Trial." Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 47, no. 7 (2015): 850-53.

- Hindi, A., E. Schafheutle, and S. Jacobs. "Patient and Public Perspectives of Community Pharmacies in the United Kingdom: A Systematic Review." Health Expectations 21, no. 2 (2017): 409-28. [CrossRef]

- Chopra, E., T. Choudhary, A. Hazen, S. Shrestha, I. Dehele, and V. Paudyal. "Clinical Pharmacists in Primary Care General Practices: Evaluation of Current Workforce and Their Distribution." Journal of Pharmaceutical Policy and Practice 15, no. 101 (2022). [CrossRef]

- NHS England. "Structured Medication Reviews and Medicines Optimisation: Guidance." In Network Contract Directed Enhanced Service, 2021.

- Bonner, M., M. Capsey, and J. Batey. "A Paramedic's Role in Reducing Number of Falls and Fall-Related Emergency Service Use by over 65s: A Systematic Review." British Paramedic Journal 6, no. 1 (2021): 46-52. [CrossRef]

- Shaya, F., V. Chirikov, C. Rochester, R. Zaghab, and K. Kucharski. "Impact of a Comprehensive Pharmacist Medication-Therapy Management Service." Journal of Medical Economics 18, no. 10 (2015): 828-37. [CrossRef]

- Siddle, J., P. Pang, C. Weaver, E. Weinstein, D. O'Donnell, T. Arkins, and C. Miramonti. "Mobile Integrated Health to Reduce Post-Discharge Acute Care Visits: A Pilot Study." The American Journal of Emergency Medicine 36, no. 5 (2018): 843-45. [CrossRef]

- Graabæk, T., U. Hedegaard, M. Christensen, M. Clemmensen, T. Knudsen, and L. Aagaard. "Effect of a Medicines Management Model on Medication-Related Readmissions in Older Patients Admitted to a Medical Acute Admission Unit—a Randomized Controlled Trial." 25 (2019): 88-96. [CrossRef]

- Kitchen, S., K. McGrail, M. Wickham, M. Law, and C. Hohl. "Emergency Department-Based Medication Review on Outpatient Health Services Utilization: Interrupted Time Series." BMC Health Services Research 20 (2020): 254. [CrossRef]

- Santolaya-Perrín, R., B. Calderón-Hernanz, G. Jiménez-Díaz, N. Galán-Ramos, M. Moreno-Carvajal, J. Rodríguez-Camacho, P. Serra-Simó, J. García-Ortiz, J. Tarradas-Torras, A. Ginés-Palomares, and I. Sánchez-Navarro. "The Efficacy of a Medication Review Programme Conducted in an Emergency Department." International Journal of Clinical Pharmacy 41 (2019): 757-66. [CrossRef]

- De Oliveira, G., L. Castro-Alves, M. Kendall, and R. McCarthy. "Effectiveness of Pharmacist Intervention to Reduce Medication Errors and Health-Care Resources Utilization after Transitions of Care: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials." Journal of Patient Safety 17, no. 5 (2021): 375-80. [CrossRef]

- Gillespie, U., A. Alassaad, D. Henrohn, H. Garmo, M. Hammarlund-Udenaes, H. Toss, Å. Kettis-Lindblad, H. Melhus, and C. Mörlin. "A Comprehensive Pharmacist Intervention to Reduce Morbidity in Patients 80 Years or Older - a Randomized Controlled Trial." JAMA Internal Medicine 169, no. 9 (2009): 894-900. [CrossRef]

- Hawes, E., W. Maxwell, S. White, J. Mangun, and F. Lin. "Impact of an Outpatient Pharmacist Intervention on Medication Discrepancies and Health Care Resource Utilization in Posthospitalization Care Transitions." Journal of Primary Care & Community Health 5, no. 1 (2013): 14-18. [CrossRef]

- Phatak, A., R. Prusi, B. Ward, L. Hansen, M. Williams, E. Vetter, N. Chapman, and M. Postelnick. "Impact of Pharmacist Involvement in the Transitional Care of High-Risk Patients through Medication Reconciliation, Medication Education, and Postdischarge Call-Backs (Ipitch Study)." Journal of Hospital Medicine 11 (2015): 39-44.

- McCahon, D., P. Duncan, R. Payne, and J. Horwood. "Patient Perceptions and Experiences of Medication Review: Qualitative Study in General Practice." BMC Primary Care 23 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Peters, A., D. Lim, and N. Naidoo. "Down with Falls! Paramedicine Scope Regarding Falls Amongst Older Adults in Rural and Remote Communiies: A Scoping Review." Austrailian Journal of Rural Health 31 (2023): 605-16. [CrossRef]

- Health Innovation Network. "Resources to Support Patients Having a Structured Medication Review." https://thehealthinnovationnetwork.co.uk/programmes/medicines/polypharmacy/patient-information/ (.

- Health Innovation Yorkshire & Humber. "Resources to Tackle Polypharmacy." Available online: https://www.healthinnovationyh.org.uk/resources-to-tackle-polypharmacy/ (accessed on 3rd June 2025).

- Hertig, R., R. Ackerman, B. Zagar, and S. Tart. "Pharmacy Student Involvement in a Transition of Care Program." Currents in Pharmacy Teaching and Learning 9, no. 5 (2017): 841-47. [CrossRef]

- Association of Ambulance Chief Executives (AACE), and Joint Royal Colleges Ambulance Liaison Committee (JRCALC). Jrcalc Clinical Guidelines. Bridgwater: Class Professional Publishing, 2022.

- Eccles, M., S. Hrisos, J. Francis, E. Kaner, H. Dickinson, F. Beyer, and M. Johnston. "Do Self- Reported Intentions Predict Clinicians' Behaviour: A Systematic Review." Implementation Science 1 (2006): 28. [CrossRef]

- Hrisos, S., M. Eccles, J. Francis, H. Dickinson, E. Kaner, F. Beyer, and M. Johnston. "Are There Valid Proxy Measures of Clinical Behaviour? A Systematic Review." Implementation Science 4 (2009): 37. [CrossRef]

| Objective | Measure | |

| Referral Rate, Suitability, and Clinical Impact | 1 | Referral rates |

| 2 | Referral appropriateness | |

| 3 | Fall and/or ambulance recurrence | |

|

Medicine Optimisation |

4 | Polypharmacy reduction. |

| 5 | Deprescribing of fall-risk medicines as per PrescQIPP [30] (Table S3) | |

| Patient Experiences | 6 | Change in emotions about their medicines post-review |

| 7 | Impact of specific review activities on emotions | |

|

Ambulance Staff Perceptions |

8 | Key indicators of medicine management difficulty |

| 9 | Perceived frequency of such cases | |

| 10 | Perceived value of pharmacist referral | |

| 11 | Influence of clinician demographics on referral value perception | |

| Case Demographic |

All referred n = 775 |

Received medicine review n = 340 (43.9%) |

Did not receive medicine review n = 435 (56.1%) |

| Age median (interquartile range) | 84 (77–89) | 84 (77–89) | 84 (77–90) |

| Patient fallen in last 12 months | |||

| Yes | 573 (73.9%) | 243 (71.5%) | 330 (75.9%) |

| No | 159 (20.5%) | 79 (23.2%) | 80 (18.4%) |

| Not recorded | 43 (5.6%) | 18 (5.3%) | 25 (5.7%) |

| Patient prescribed ≥4 medicines | 597 (77.0%) | 264 (77.6%) | 333 (76.6%) |

| Ambulance crew concerned about medicines | 173 (22.3%) | 64 (18.8%) | 109 (25.1%) |

| Time from referral to initial review decision median days (interquartile range) | 10 (4–27) | 9 (3–21) | 28 (10–109) |

| Case Demographic | Value |

| Frailty n (%) | |

| Severe | 86 (25.3%) |

| Moderate | 106 (31.2%) |

| Mild | 6 (1.8%) |

| Not frail | 128 (37.6%) |

| Not recorded | 14 (4.1%) |

| Pharmacist review type n (%) | |

| Face-to-face | 7 (2.1%) |

| Telephone | 77 (22.6%) |

| Notes based | 125 (36.8%) |

| Not recorded | 131 (38.5%) |

| Referral considered appropriate n (%) | |

| Yes | 263 (77.4%) |

| No | 67 (19.7%) |

| Not recorded | 10 (2.9%) |

| Proforma Field | Value |

| Number of medicines median (interquartile range) | |

| Prior to review | 9 (6–12) |

| After review | 9 (6–12) |

| Stopped by pharmacist | 0 (0–0) |

| Changes recommended by pharmacists n (%) | 149 (43.8%) |

| Pharmacist categorisation of medicine fall risk as per PrescQIPP n (%) | |

| Yes | 76 (22.2%) |

| High risk | 43 (12.6%) |

| Medium risk | 11 (3.2%) |

| Possible risk | 13 (3.8%) |

| Risk present but level not recorded | 9 (2.6%) |

| No | 51 (15.0%) |

| Not recorded | 213 (62.6%) |

| Survey Question | Result |

| Age mean (standard deviation) | 83.59 (9.99) |

| Gender n (%) | |

| Male | 26 (54.2%) |

| Female | 21 (43.8%) |

| N/A | 1 (2.1%) |

| Ethnic group n (%) | |

| Asian/Asian British Indian | 1 (2.1%) |

| White British | 44 (91.7%) |

| White Irish | 2 (4.2%) |

| N/A | 1 (2.1%) |

| How many medicines were you taking? n (%) | |

| 0 | 1 (2.1%) |

| 1 to 4 | 14 (29.2%) |

| 5 or more | 30 (62.5%) |

| Don’t know | 1 (2.1%) |

| N/A | 2 (4.2%) |

| How was your medicines review undertaken? n (%) | |

| Face-to-face | 15 (31.2%) |

| Telephone | 13 (27.1%) |

| Don’t know | 14 (29.2%) |

| N/A | 6 (12.5%) |

| Reported emotion before review (n) | Reported emotion after review (n) | ||

| Negative | Neutral | Positive | |

| Negative | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Neutral | 0 | 23 | 0 |

| Positive | 0 | 1 | 5 |

| Question |

Overall n (%) |

Referred n (%) |

Not referred n (%) |

| Total responses | 146 (100%) | 18 (12.3%) | 128 (87.7%) |

| Respondent role | |||

| Advanced Paramedic | 7 (4.8%) | 0 (0%) | 7 (5.5%) |

| Emergency Care Assistant | 21 (14.4%) | 1 (5.6%) | 20 (15.6%) |

| Emergency Medical Technician | 9 (6.2%) | 3 (16.7%) | 6 (4.7%) |

| Manager | 13 (8.9%) | 1 (5.6%) | 12 (9.4%) |

| Newly Qualified Paramedic | 21 (14.4%) | 1 (5.6%) | 20 (15.6%) |

| Paramedic | 65 (44.5%) | 11 (61.1%) | 54 (42.2%) |

| Specialist Paramedic | 6 (4.1%) | 1 (5.6%) | 5 (3.9%) |

| Student Paramedic | 4 (2.7%) | 0 (0%) | 4 (3.1%) |

| Working arrangement | |||

| Full-time (37.5 hours a week) | 112 (76.7%) | 16 (88.9%) | 96 (75.0%) |

| Part-time (including bank) | 34 (23.3%) | 2 (11.1%) | 32 (25.0%) |

| How frequently do you attend an incident involving a patient over the age 65 years who has fallen, on average? | |||

| More than once a shift | 55 (37.7%) | 8 (44.4%) | 47 (36.7%) |

| Once a shift | 63 (43.2%) | 8 (44.4%) | 55 (43.0%) |

| Once a week | 12 (8.2%) | 1 (5.6%) | 11 (8.6%) |

| Once a month | 16 (11.0%) | 1 (5.6%) | 15 (11.7%) |

| Have you or your crewmate referred a patient to a pharmacist for a community medicine review? | |||

| Yes | 18 (12.3%) | 18 (100%) | 0 (0%) |

| No, and work in the study area | 22 (15.1%) | 0 (0%) | 22 (17.2%) |

| No, but do not work in the study area | 102 (69.9%) | 0 (0%) | 102 (79.7%) |

| Unsure | 4 (2.7%) | 0 (0%) | 4 (3.1%) |

| How important do you feel it is to have the option to refer patients who have fallen and who are taking multiple medicines, to a community pharmacist for review? | |||

| Very important | 79 (54.1%) | 12 (66.7%) | 67 (52.3%) |

| Important | 46 (31.5%) | 4 (22.2%) | 42 (32.8%) |

| Neutral | 16 (11.0%) | 1 (5.6%) | 15 (11.7%) |

| Unimportant | 2 (1.4%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (1.6%) |

| Very unimportant | 1 (0.7%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (0.8%) |

| N/A | 2 (1.4%) | 1 (5.6%) | 1 (0.8%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).