1. Introduction

The agricultural use of organophosphate (OP) insecticides to control crop insect infestations has been reduced in some countries due to the human toxicity of these compounds. OPs like malathion may still be used to control disease vectors such as mosquitoes, but pyrethroid-based insecticides are now preferred due to lower human toxicity. However, many regions of the world still employ OP insecticides due to their effectiveness and low cost [

1]. Global pesticide use, especially in lower income countries, has increased substantially in the last decade [

2].

Hundreds of different OP insecticides have been synthesized including acephate (active metabolite; methamidophos), chlorpyrifos, diazinon (active metabolite; diazoxon), dimethoate, fenthion (active metabolite; fenoxon), malathion (active metabolite; malaoxon), methamidophos, naled, phorate, phosmet and parathion (active metabolite; paraoxon), among others. Many of these insecticides are still used in agriculture and mosquito control. OP insecticides such as chlorpyriphos are still permitted for use on certain food crops in the US by the environmental protection agency (

https://www.epa.gov/pesticide-worker-safety/epa-update-use-pesticide-chlorpyrifos-food). Estimates of OP insecticide use in the US can be found here:

https://earthjustice.org/feature/organophosphate-pesticides-maps#define. Usage in many lower income nations is often much higher than in the US.

Parathion is one of the most toxic of these insecticides to humans. While parathion has been banned for use in some countries, it continues to be used in developing countries due to its low cost and high effectiveness. Parathion by itself is a toxic acetylcholinesterase inhibitor, but once in the body it is converted to paraoxon, a far more active toxin, by the enzymatic action of the P450 system in tissues such as the liver [

3]. Paraoxon, like other OP insecticides, acts to block the action of acetylcholinesterase, the enzyme which is responsible for deactivating the neurotransmitter acetylcholine at synapses in the brain, as well as at the neuromuscular junction. Excess acetylcholine at the neuromuscular junction results in over-activation and eventual exhaustion of muscular contraction, which can disrupt or halt respiration, leading to death. The standard treatment for OP poisoning involves the use of atropine sulfate to block the action of acetylcholine at muscarinic acetylcholine receptors. This prevents the over-activation of the acetylcholine receptors at the neuromuscular junction. In addition, the standard treatment also involves the administration of an oxime such as pralidoxime, which can reverse the action of OPs at the active site of the acetylcholinesterase enzyme, thus bringing acetylcholine levels at the neuromuscular junction under control.

Atropine sulfate and pralidoxime control the overactivation of neuromuscular junctions and can prevent death, even in some cases of severe OP insecticide poisoning, if they are administered promptly and repeatedly. However, these treatments do not cross the blood brain barrier and therefore cannot counteract the CNS effects of OP insecticides. In the CNS, OPs set off a cascade of pathological effects starting with overactivation of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Continuous acetylcholine action drives uncontrolled release of glutamate at glutamatergic synapses, which in turn leads to seizures and excitotoxic neuronal damage if not brought under control. The current treatment for convulsions and seizures is a benzodiazepine like diazepam or midazolam, but this treatment does not fully control the excessive glutamatergic action [

4]. As such, additional treatments are needed to protect the CNS from excitotoxic damage.

During the course of experiments to determine if the oxime obidoxime could be administered intranasally to bypass the blood brain barrier and protect the CNS from excitotoxic damage [

5], we noticed that the animals given paraoxon, but not treated with intranasal obidoxime, did not have any neuronal damage. This finding was difficult to explain because we were using very high doses of the insecticide paraoxon. Additional work showed that the administration of very brief (5 min) isoflurane that was used to facilitate intranasal delivery of obidoxime, was having powerful neuroprotective effects [

6]. Further investigation demonstrated that brief, 5 minute, isoflurane administration was very effective at protecting the CNS from damage, even when administration was delayed for 1 hour after paraoxon administration [

7]. In this review we examine the evidence in support of isoflurane and other halogenated ether anesthetics as adjunct anti-convulsant and neuroprotective treatments for OP poisoning.

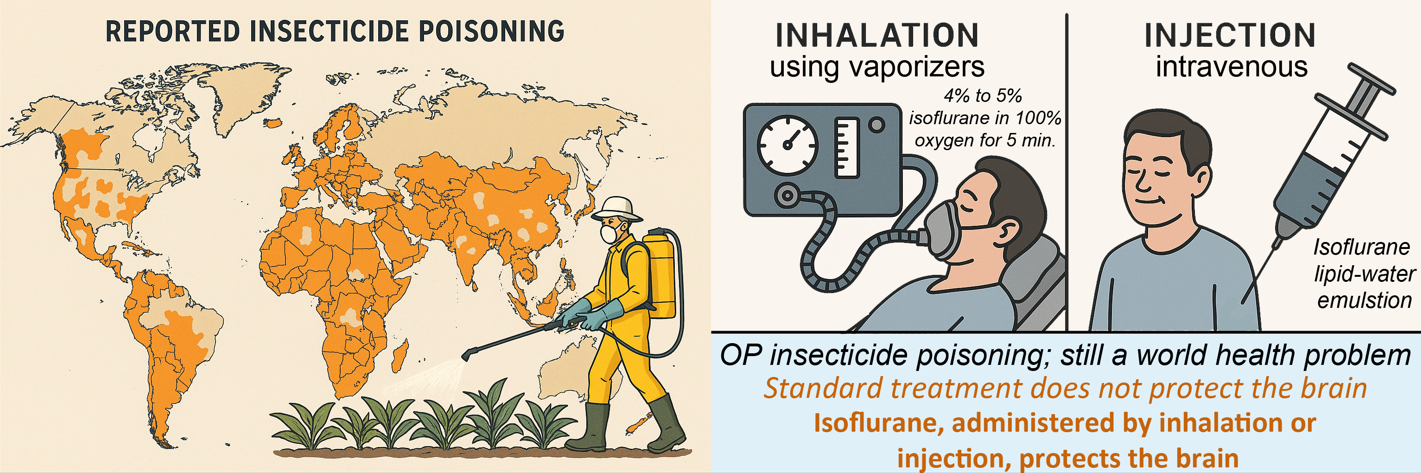

2. OP Insecticides, Still a World Health Problem

Despite declining worldwide use of OP insecticides, they continue to be used in developing countries where alternatives may not be available or affordable. It has been estimated that as many as 3 million people in the world are exposed to OP compounds every year [

8,

9]. In countries where OP insecticides are still in use, OP poisoning is the most common emergency treated at poisoning control centers [

10]. OP insecticides have been associated with tens of thousands of suicide attempts by farmers and agricultural workers in developing countries each year. Countries where OP pesticides are associated with a large number of suicide attempts have large agriculture populations, including India, Pakistan and China [

11]. A review of all reported pesticide poisoning cases in Pakistan up to 2021 indicated that in poisoning cases involving suicide attempts, OP insecticides accounted for the largest number of poisonings [

12]. A total of 53,323 cases of poisoning were identified, of which 24,546 [46.0%] were due to pesticides. OP insecticides were responsible for 13,816 (56.2%) of the total pesticide poisoning cases. There is evidence that occupational exposure to OP insecticides can lead to depression [

13,

14] and thus increase the likelihood that farmers and workers might then attempt suicide [

15,

16].

OP insecticides continue to be widely used in agriculture, particularly in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). Despite restrictions or bans in many high-income nations due to their acute neurotoxicity and environmental persistence, OPs remain prevalent elsewhere due to their affordability and effectiveness. However, pesticide use trends in LMICs have been substantially underestimated due to incomplete reporting and poor data transparency, complicating both risk assessment and intervention planning [

2].

This continued use of OP insecticides is not solely a matter of preference but reflects broader disparities in access to safer alternatives, limited regulatory enforcement, and agricultural dependence. OP insecticides such as chlorpyrifos, dimethoate, and malathion remain widely utilized in global agriculture due to their cost-effectiveness, broad-spectrum activity, and limited availability of safer substitutes, particularly in LMICs [

17]. In many areas, these compounds are readily accessible without adequate professional oversight, safety training, or labeling, which increases the risk of both occupational exposure and intentional misuse [

18]. Sale of banned or restricted OPs is widespread in some informal or rural markets, where enforcement of chemical regulations is often under-resourced or inconsistently applied [

17]. Moreover, widespread unsafe storage and pesticide-handling practices among small landholder and subsistence farmers—particularly in regions lacking centralized training infrastructure—have been consistently reported in global analyses of occupational pesticide exposure [

18,

19,

20]. These intersecting gaps in enforcement, oversight, and education continue to drive OP-related health risks across diverse agricultural economies.

Reports from rural agricultural regions have documented widespread circulation of counterfeit and unregistered pesticide products—often purchased unknowingly by farmers—which substantially heightens the risk of unregulated OP exposure [

17,

21]. According to a technical report by the United Nations Interregional Crime and Justice Research Institute (UNICRI), the illegal manufacturing and distribution of illicit pesticides—including OP-based formulations—has become increasingly tied to transnational organized crime and continues to undermine global chemical safety efforts [

22]. Although empirical data are limited, some reports suggest that access to precursor chemicals may allow for the unregulated synthesis of OPs in unregulated sectors, further complicating enforcement in regions with poor oversight (

https://anti-fraud.ec.europa.eu/document/download/38e8dee1-1665-4e31-ad21-29c9ce9fa598_en).

Estimates suggest that pesticide ingestion still accounts for approximately 258,000 deaths annually, primarily in LMICs [

23], despite decades of intervention efforts. Sri Lanka’s success in reducing suicide rates through aggressive OP regulation demonstrates that targeted policy actions can yield measurable impact if enforcement is diligently followed [

23]. Sri Lanka provides a notable example of successful regulatory intervention. Once among the countries with the highest rates of pesticide suicides, Sri Lanka implemented strict bans on highly hazardous pesticides (HHPs), including several OPs. This led to a marked decline in suicide rates without negatively impacting crop yields [

23]. This experience demonstrates that public health gains can be achieved through carefully targeted pesticide policies, though such strategies have yet to be widely replicated in many LMICs.

The public health implications of continued OP usage are considerable. Chronic occupational exposure can lead to cumulative neurotoxic effects, even without overt symptoms. Long-term OP exposure has been significantly associated with increased risk of depression among agricultural workers [

13], and suicidal ideation in broader exposed populations [

15]. On the other end of the spectrum, acute poisoning—particularly via intentional ingestion—remains a persistent crisis in rural regions. Self-poisoning using OPs accounts for a substantial proportion of pesticide-related deaths in LMICs [

11].

Beyond acute poisoning and occupational exposure, chronic low-level exposure to organophosphate (OP) pesticides through environmental and dietary routes poses significant public health concerns. OP residues are frequently detected on food crops, with recent analyses showing that over 50% of tested produce samples contained pesticide residues—many exceeding safety thresholds—with OPs among the most prevalent [

24]. Such residues contribute to widespread exposure among the general population, not just agricultural workers. Biomonitoring studies have revealed detectable levels of OP metabolites in urine samples from children living in agricultural communities, underscoring early-life exposure in rural environments and highlighting the pervasive nature of background exposure [

25].

Children are particularly vulnerable to these exposures, as several studies have linked prenatal and early-life OP contact to cognitive deficits, neurodevelopmental delays, and behavioral disorders [

26,

27]. These adverse effects are believed to result from OP-induced disruption of acetylcholinesterase activity and neurotransmitter function during critical windows of brain development [

28]. In addition, OPs have been identified as endocrine-disrupting chemicals, capable of altering hormonal signaling and affecting reproductive and developmental health [

29]. Collectively, these findings underscore the need for upstream interventions, not only to restrict OP access but also to mitigate chronic environmental exposure risks that extend beyond the occupational setting.

Although some regulatory improvements have been implemented globally, the persistence of OP use in LMICs—combined with inadequate access to medical care and antidotes—continues to impose a heavy health burden. In many rural settings, antidotal therapy is delayed due to limitations in infrastructure, transportation, and trained personnel, reducing the effectiveness of standard interventions. These systemic gaps contribute significantly to mortality and long-term morbidity from OP poisoning and underscore the need for adjunct therapies that mitigate irreversible CNS injury [

23].

3. Inhalation Administration of Halogenated Anesthetics

The halogenated ether anesthetics include halothane, isoflurane, desflurane and sevoflurane. Halothane is no longer in use in most countries due to its hepatotoxicity and association with cardiac arrhythmias, but is still in use where newer alternatives are not readily available [

30]. These anesthetics are administered through the use of specialized vaporizer equipment that mixes the anesthetic vapors with oxygen at specified concentrations. Vaporizers and trained staff are available at most hospitals throughout the world, making this treatment option the preferred method of administration in most circumstances.

Two early studies on the use of isoflurane in the treatment of OP poisoning indicated that this method might offer significant advantages over benzodiazepines [

6,

31]. These two studies involved the OP insecticide paraoxon and demonstrated that isoflurane reduced convulsions and seizures, prevented blood-brain barrier damage and edema and reduced neuronal loss and astrogliosis.

In the first study, by Bar-Klein and colleagues [

31], rats were subjected to a moderate dose of paraoxon (0.45 mg/kg) that was sufficient to develop recurrent seizures as a model for epilepsy. For their isoflurane treatment protocol, Bar-Klein et al. used multiple 1-hour administrations of 1%–2% isoflurane delivered in 100% oxygen, and this treatment was given at 1, 6 and 12 hours, and then again over multiple days (1, 2, 3, 7 and 30 days) after paraoxon administration. This use of isoflurane was done to mimic its use as an anesthetic, employing low doses delivered over extended administration times. They observed several therapeutic effects of this isoflurane regimen in their paraoxon model of epilepsy. Isoflurane treatment prevented the development of epilepsy caused by paraoxon poisoning and prevented blood-brain barrier damage and neuroinflammation as shown by magnetic resonance imaging. It also prevented delayed neurodegeneration and astrogliosis. The authors noted that isoflurane had anti-epileptic effects that were far more pronounced than they had observed with any other agent up to that time. They hypothesized that isoflurane’s protective effects involved multiple mechanisms, possibly including inhibition of calcium influx into endothelial cells, reduced neutrophil adhesion to endothelial cells, preservation of tight junction expression and inhibition of neuroinflammation.

The second early study [

6], which was done in our laboratory, came about as a serendipitous discovery during experiments to determine if the obidoxime could be efficiently delivered to the brain using intranasal administration [

5]. During the course of these experiments, we found that the rats given a lethal dose of paraoxon but not treated with intranasal obidoxime, had minimal convulsions and did not have any delayed neuronal damage. The only treatment they had received was 4-5% isoflurane given until the animals were unconscious (3 to 4 min.), which was administered only to facilitate accurate intranasal delivery. After reviewing the results, we concluded that brief, high-dose isoflurane had exceptional therapeutic properties in OP poisoning.

The discovery that brief isoflurane administration had powerful anticonvulsant and neuroprotective effects led us to investigate the phenomenon in more detail. For these experiments we used very high dose paraoxon (4mg/kg) [

6], which was approximately 9 times higher dose than that used by Bar-Klein and colleagues [

31]. Immediately after paraoxon administration, rats were given atropine sulfate and pralidoxime to allow a sufficient number of rats to survive the duration of the experiments (24 hours).

In time course studies [

6], we used our standard protocol for anesthesia induction in rats, which involved delivering 2% isoflurane in 100% oxygen for 3 minutes, followed by 5% isoflurane in 100% oxygen for 1 minute. This treatment was administered at multiple time points to determine the window of opportunity for isoflurane’s actions, including 10, 20, 30, 45, 60 and 120 minutes after paraoxon poisoning. Convulsions were scored using a modified Racine scale [

5], which showed that the brief exposure to isoflurane was most effective at halting convulsions when administered at 20 or 30 minutes after paraoxon. Lower, but significant reductions in convulsion severity were also seen when isoflurane was given at all the other time points. We used Fluoro-Jade C (FJC) staining to assess neuronal damage 24 hours after paraoxon with and without isoflurane administration. In rats that did not receive isoflurane, extensive FJC staining was observed throughout the forebrain, including the amygdala, hippocampus and central thalamus at 24 hours. Animals treated isoflurane 30 minutes after paraoxon (2% isoflurane for 3 minutes, followed by 5% isoflurane for 1 minute) had little to no FJC staining in any region, demonstrating robust neuroprotection.

We also performed dose-response studies with isoflurane [

6]. When we administered isoflurane 30 minutes after paraoxon, we found that 1% or 2% isoflurane given for 4 minutes did not block convulsions and did not reduce neuropathology as shown by FJC staining. When the concentration was increased to 2% for 3 minutes followed by 3.5% for 1 minute, convulsions were successfully blocked and FJC staining was prevented. This indicates that a dose of 3.5% or higher is needed for effectiveness with brief administration times. Because many studies limit the isoflurane concentration to 1 or 2%, many of the potentially protective effects may not have been achieved.

More recently, we investigated the effectiveness of brief isoflurane in blocking convulsions, protecting neurons and preventing brain edema and astrogliosis after paraoxon poisoning [

32]. In this later study we also determined if higher dose isoflurane (4% to 5% for 5 min) would extend the effective window of opportunity beyond the 30-minute post-exposure time point. In this study, convulsions were again assessed according to a modified Racine scale of convulsion severity [

6]. Rats were treated 1 hour after paraoxon administration with 4%, 4.5% or 5% isoflurane in 100% oxygen for 5 min. Paraoxon injury groups were treated with 2-PAM and atropine sulfate, but were not treated with isoflurane. Animals treated for 5 minutes with isoflurane at the 1-hour post-exposure time point regained consciousness within 8 to 10 minutes after cessation of isoflurane and only exhibited stage 1 convulsive activity afterwards, typically chewing motions without any other signs of convulsive activity. These animals remained awake, but mostly motionless, for up to 1 hour after isoflurane treatment and then displayed low locomotor activity for the next several hours. Unlike the isoflurane treated groups, the paraoxon-poisoned untreated group continued variable convulsive activity up to 8 hours, the latest time point examined. At 24 hours, the surviving rats that were not treated with isoflurane continued to show mild convulsive activity and were extremely lethargic. The animals in the isoflurane treatment groups appeared normal, with normal locomotor activity at this time point. We did not observe any differences in the anticonvulsant effectiveness among the 3 doses of isoflurane used, indicating that 4% isoflurane was sufficient to stop convulsions without the need for re-administration.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was used to quantify brain edema 24 hours after paraoxon administration. Isoflurane was administered at a concentration of 5% for 5 minutes, starting 1 hour after paraoxon administration. Then, 24 hours later, the animals were assessed by MRI to visualize brain edema using T2-weighted images and tissue damage using mean diffusivity measurements. Rats poisoned with paraoxon, but not treated with isoflurane, had hyperintense T2-weighted signals in several brain regions, including neocortex, hippocampus and amygdala, indicative of widespread brain edema. In contrast, in the rats given isoflurane (5% for 5 min) 1 hour after paraoxon, the T2 MRI values were comparable to the uninjured control group, demonstrating that isoflurane blocked brain edema completely, even when administration was delayed for 1 hour. Similarly, mean diffusivity measurements, wherein low values are indicative of tissue damage, were significantly lower in the injured group not treated with isoflurane, but were normal in the rats treated with isoflurane 1 hour after paraoxon. This finding further supports the conclusion that isoflurane, when administered at 5% for 5 minutes, prevents brain tissue damage, even when delayed for 1 hour after paraoxon.

The effective window of opportunity for brief isoflurane administration was examined by administering isoflurane (5% for 5 min) at 60, 90, 120 and 180 minutes after paraoxon poisoning and neuronal damage was then assessed by Fluoro-Jade B (FJB) staining. In rats that had been poisoned with paraoxon, but not treated with isoflurane, staining was extensive throughout the forebrain. Regions with high levels of neuronal damage included neocortex, thalamus and amygdala. Isoflurane administration at the 60-minute time point resulted in significant reductions in FJB staining in neocortex, thalamus and amygdala. At the 90-minute time point, significant reductions were observed in the amygdala, with non-significant but notable reductions observed in the other regions. Only minor non-significant reductions were observed at the 120-minute time point, and no improvement was observed at the 180-minute time point. These findings indicate that achieving full neuroprotective effectiveness requires that isoflurane be given within 1 hour of the onset of OP poisoning.

Astrogliosis is the defensive reaction of astrocytes to any type of brain injury. We examined astrogliosis in our paraoxon animal model using immunohistochemistry. In uninjured control rats, astrocytes had small cell bodies with very light staining, indicating a non-reactive condition. In the paraoxon poisoned rats, strong staining for astrocytes was extensive throughout the brain, and the astrocytes were enlarged, demonstrating a strong astrogliosis response to the tissue damage. When isoflurane (5% for 5 minutes) was administered 1 hour after paraoxon, astrogliosis was substantially attenuated, further demonstrating isoflurane’s effectiveness in protecting the brain from the excitotoxic damage caused by OP poisoning.

Taken together, these data reveal a previously unrecognized off-label use of brief isoflurane administration as a widely available, safe and effective anti-convulsant and neuroprotectant for the treatment of OP poisoning that is compatible with the standard treatment regimen.

4. Intravenous Administration of Isoflurane Emulsions

Halogenated ether anesthetics, including isoflurane, desflurane and sevoflurane, and the vaporizer equipment needed to administer them, are widely available in hospitals and clinics throughout much of the world. This makes these anesthetics well suited to the treatment of patients who arrive at medical facilities after intentional or unintentional exposure to OP toxins. Brief treatment using vaporizers offers a rapid and practical treatment option for OP poisoning in many countries, but there are many rural and under developed regions where vaporizers may not be available. Therefore, it would be desirable to develop an alternative administration method that did not require vaporizer equipment and trained personnel to administer.

Based on published studies on the safety and efficacy of injectable isoflurane lipid-water emulsions (ILE) [

33,

34,

35], we hypothesized that an intravenous administration method could be developed for the use of halogenated anesthetics to treat OP poisoning. ILEs have been proven safe and effective for anesthesia in humans [

33,

34,

35]. In clinical trials, loss of consciousness (LOC) was observed in all subjects who were given an ILE dose containing at least 22.6 mg/kg of isoflurane [

35]. The onset of LOC occurred about 40 seconds after the initiation of the ILE intravenous infusion. A single bolus injection of 4ml of ILE, with a dose of 36.8mg/kg, delivered over the course of 10 seconds led to LOC that persisted for approximately 7 minutes [

35].

We tested this hypothesis in rats using a micro-infusion pump to deliver ILEs with varying concentrations of isoflurane via implanted jugular cannulas [

36]. The ILEs were prepared by mixing isoflurane at several different concentrations with a pre-made lipid-water emulsion -- Intralipid-30. According to the manufacturer, Intralipid-30 is a sterile, non-pyrogenic, homogenous lipid emulsion for intravenous infusion as a source of calories and essential fatty acids for use in a pharmacy admixture program. The lipid content of Intralipid-30 is 30% and contains approximately 30 g soybean oil, 1.2 g egg yolk phospholipids, 1.7 g glycerin, water for injection, and sodium hydroxide to adjust the pH.

To prepare ILEs we mixed varying ratios of isoflurane with Intralipid-30 (vol./vol.) and tested these on rats. Based on the known solubility of isoflurane in Intralipid-30 [

37] and our results in achieving LOC in rats via jugular infusion, we chose a concentration of 10% isoflurane by volume. We then tested different flow rates for the ILE infusions in rats that had been given paraoxon (4mg/kg) 30 minutes earlier and found that an ILE containing 10% isoflurane could be used to stop convulsions when given to ~300gm rats at a flow rate of 200µl/min. for 5 minutes. This translates to an isoflurane infusion rate of 20 microliters per minute. Prior to administration of the ILE, all rats given paraoxon exhibited severe convulsions. Once ILE infusion was initiated, LOC was achieved in less than one minute and the animals remained unconscious for 8 to 10 minutes. Upon awakening, the paraoxon poisoned animals showed only very minor convulsion symptoms, such as chewing motions, but otherwise exhibited very low activity levels for approximately 1 hour. This depressed activity period was not observed in uninjured control animals that were not given paraoxon prior to administration of the ILE. They demonstrated normal activity levels within 5 to 10 minutes after awakening. It is noteworthy that the paraoxon poisoned animals did not resume any convulsive activity other than chewing motions for the remainder of the observation period of 4 hours.

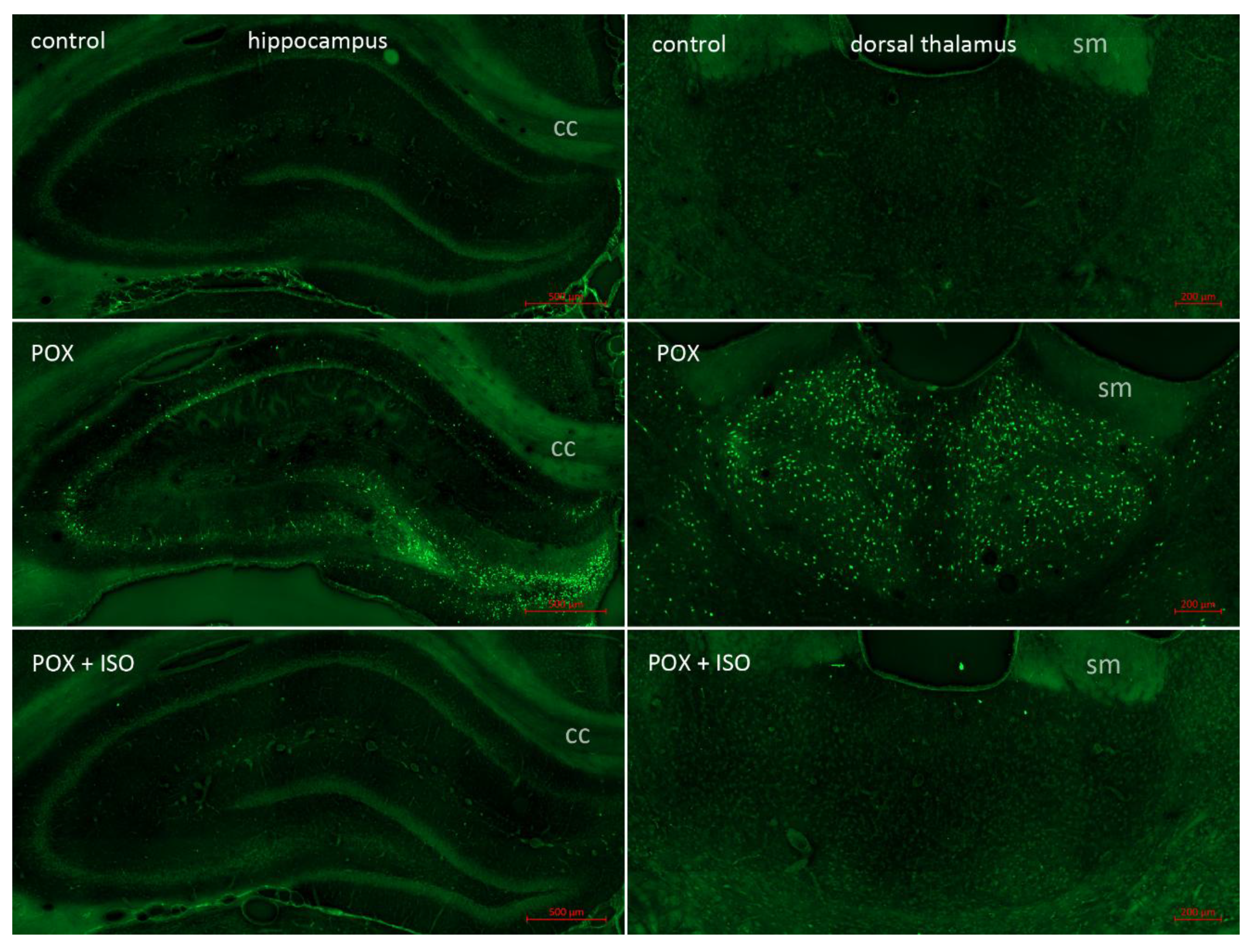

Neuropathology was assessed 24 hours after paraoxon poisoning using FJB staining to visualize damaged neurons (

Figure 1). No neuronal FJB staining was observed in any brain region in the uninjured control rats that did not receive paraoxon. The group that was given paraoxon, but not treated with the ILE, had extensive FJB staining in many brain regions, including the neocortex, thalamus, hippocampus, piriform cortex and amygdala. In the animals who were treated with the ILE (10% isoflurane delivered at 200 microliters per minute for 5 minutes) only minor FJB staining was observed in some of the vulnerable regions. No FJB stained neurons were observed in the neocortex or the hippocampus, and only a few scattered FJB stained neurons were observed in the thalamus (see

Figure 1, bottom right panel) and amygdala. These findings indicate that ILEs have potent neuroprotective effects in the treatment of OP poisoning that are not seen with other anticonvulsants such as the benzodiazepines. It is noteworthy that a recent report indicates that lipid-water emulsions have protective effects by themselves in the treatment of organophosphate poisoning [

38]. Li and Hu have shown that when the standard treatment regimen of atropine sulphate and pralidoxime was combined with the IV infusion of a 20% lipid-water emulsion (20% lipid by volume), tissue damage in multiple organ systems was significantly reduced. Such findings indicate that ILEs may be more effective in treating OP poisoning than inhaled isoflurane, while also negating the need for vaporizer equipment for administration.

5. Discussion

Tens of thousands of people are poisoned with OP insecticides every year, and the standard treatment regimen of atropine plus oxime to mitigate cholinergic over-activation and benzodiazepines to block convulsions, does not protect the CNS from permanent damage. Any adjunct treatment that helps protect the brain from the sequalae of OP poisoning would be desirable. Brief isoflurane administration provides a rapid and effective method for treating the convulsions associated with severe OP poisoning and for protecting the CNS from injury. Halogenated ether anesthetics and the vaporizer equipment needed to administer them are widely available in most hospitals throughout the world. However, in rural areas of under-developed countries, such access to hospitals may not be available even though it is in these countries that there may be a more urgent need for improved treatments for patients with OP poisoning. The pharmaceutical development of an ILE for intravenous administration to patients with OP poisoning would allow for administration in circumstances where vaporizer equipment is not available. Intralipid-30 is supplied from the manufacturer in IV drip bags for infusion into patients requiring parenteral nutritional support. A similar product could be made containing 5% to 10% isoflurane for IV drip administration to patients diagnosed with OP poisoning.

Investigations into non-cholinergic interventions for treating OP poisoning with the nerve agent sarine in swine showed that the oxygen concentration used may be important for neuroprotection. Sawyer et al. showed that the effectiveness of isoflurane was enhanced when the oxygen concentration was increased from 30% oxygen to 100% [

39]. All of our neuroprotective results were achieved with the use of 4% to 5% isoflurane mixed with 100% oxygen. As such, it may be important when using anesthesia vaporizers to administer isoflurane in conjunction with 100% oxygen to maximize effectiveness.

The use of halogenated ether anesthetics at low doses for extended periods during surgical procedures is in sharp contrast to our delivery of 4%–5% isoflurane administered in 100% oxygen for 5 min in a single dose sufficient to induce LOC for 8 to 10 minutes. The novelty of our approach was the discovery that longer duration administrations and repeated applications of isoflurane were not necessary to achieve its potent anticonvulsant and neuroprotective effects. In their investigation into the use of isoflurane to treat paraoxon poisoning in rats, Bar-Klein and colleagues used repeated 1-hour sessions of 1% to 2% isoflurane over the course of days, and found significant neuroprotection. Our results using a single, brief, high dose administration of isoflurane are in excellent agreement with their findings, indicating that the long-duration administration and repeated doses are not necessary for the protective effects of isoflurane.

The administration of short-duration isoflurane inhalation or single-dose ILE injection maximizes effectiveness while minimizing any potential side effects. Isoflurane can induce rare side effects, such as malignant hyperthermia, which affects between 1:10,000 to 1:250,000 people [

40]. Malignant hypothermia onset is dependent on the duration of anesthesia and is more common in patients given succinylcholine [

41]. Brief exposure to isoflurane would limit any side-effects or pathological responses in sensitive patients.

The long-term neurological consequences of excessive organophosphate insecticide exposure are not fully understood. Studies have linked pesticide exposure to the development of Parkinson’s disease [

42,

43,

44,

45] including exposure to OP insecticides. Additional associations have been made between pesticide exposure and cancer risk [

46,

47]. An Institute of Medicine report published in 2000 briefly addressed the issue of the long-term neurological consequences of OP insecticide poisoning [

48]. They concluded;

“Taken together, these cross-sectional studies report a consistent tendency toward poorer neuropsychological performance and increased rates of neuro-logical or psychiatric symptoms among persons with prior acute OP poisoning. The time from poisoning until evaluation in these studies is poorly documented but is typically on the order of years. … There is consistent evidence that OP pesticide exposures sufficient to produce acute symptoms requiring medical care or reporting are associated with longer-term (1–10 years) increases in reports of neuropsychiatric symptoms and poorer performance on standardized neuropsychological tests” [48; Appendix E]. Considering the potential for long-term neurological damage associated with OP insecticide poisoning, improved neuroprotective treatments are needed. Brief, high-dose isoflurane treatment offers a promising neuroprotective adjunct to the current treatment standard, and should be considered when patients are admitted to hospitals with clear signs of OP poisoning.

6. Conclusions

The use of OP-based insecticides continues to present health risks, especially in developing countries where alternative insecticides may not be readily available. Halogenated ether anesthetics, such as isoflurane, provide an adjunct anticonvulsant for use in the treatment of OP insecticide poisoning that also protect the brain from excitotoxic damage and brain edema. Inhalation anesthetics are available widely in clinics and hospitals throughout the world providing a simple method for halting OP-induced convulsions and protecting the CNS from irreversible damage. The use of halogenated ether anesthetics is compatible with the current OP treatment regimen of atropine sulfate and an oxime such as pralidoxime. It can also be administered after benzodiazepine treatment if benzodiazepines fail to control convulsions. Administrations times can be as brief as 5 minutes and still confer excellent control of convulsions and superior neuroprotection to existing treatments.

The current evidence indicates that adding volatile anesthetics to the treatment regimen for OP poisoning is warranted. Both inhalation and IV injection administration routes have been found to be effective for improved neuroprotection compared with benzodiazepines. Isoflurane lipid-water- emulsions could be delivered by IV drip or injection if suitable formulations are produced for human use. These applications repurpose an FDA approved anesthetic as a single dose anti-convulsant and neuroprotective drug for the treatment of OP poisoning.

7. Patents

The investigators AMN, JKSK, and JRM, in conjunction with the Henry Jackson Foundation for Military Medicine, have been awarded a US patent (US 11,291,637 B2) for the use of halogenated ethers to treat OP poisoning.

Author Contributions

A.M.N., J.K.S.K. and J.R.M. conceived the study, A.M.N., J.K.S.K. and J.R.M. wrote the manuscript and A.M.N. acquired the funding.

Funding

USUHS Short Term Discovery Grant APG-70-12933 and USUHS grant HU0001-22-2-00662.

Conflicts of Interest

The investigators AMN, JKSK and JRM, in conjunction with the Henry Jackson Foundation for Military Medicine, have been awarded a US patent (US 11,291,637 B2) for the use of halogenated ethers to treat OP poisoning.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Author disclaimer

The opinions and assertions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Uniformed Services University or the Department of Defense.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CNS |

central nervous system |

| FJB |

Fluoro-Jade B |

| FJC |

Fluoro-Jade C |

| ILE |

isoflurane lipid-water emulsions |

| IV |

intravenous |

| LMIC |

low to moderate income countries |

| LOC |

loss of consciousness |

| MRI |

magnetic resonance imaging |

| OP |

organophosphate |

| UNICRI |

United Nations Interregional Crime and Justice Research Institute |

References

- Costa, L.G., Organophosphorus Compounds at 80: Some Old and New Issues. Toxicol Sci, 2018. 162(1): p. 24-35.

- Shattuck, A., et al., Global pesticide use and trade database (GloPUT): New estimates show pesticide use trends in low-income countries substantially underestimated. Global Environmental Change, 2023. 81: p. 102693.

- Jan, Y.H., et al., Novel approaches to mitigating parathion toxicity: targeting cytochrome P450-mediated metabolism with menadione. Ann N Y Acad Sci, 2016. 1378(1): p. 80-86.

- Morgan, J.E., et al., Refractory and Super-Refractory Status Epilepticus in Nerve Agent-Poisoned Rats Following Application of Standard Clinical Treatment Guidelines. Front Neurosci, 2021. 15: p. 732213.

- Krishnan, J.K., et al., Intranasal Delivery of Obidoxime to the Brain Prevents Mortality and CNS Damage from Organophosphate Poisoning. Neurotoxicology., 2016. 53: p. 64-73.

- Krishnan, J.K.S., et al., Brief isoflurane administration as a post-exposure treatment for organophosphate poisoning. Neurotoxicology., 2017. 63: p. 84-89.

- Puthillathu, N., et al., Brief isoflurane administration as an adjunct treatment to control organophosphate-induced convulsions and neuropathology. Frontiers in Pharmacology, 2023. 14.

- Sontakke, T. and S. Kalantri, Predictors of Mortality in Hospitalized Patients With Pesticide Poisoning. Cureus, 2023. 15(7): p. e41284.

- Gunnell, D., et al., The global distribution of fatal pesticide self-poisoning: systematic review. BMC.Public.Health., 2007. 7: p. 357.

- Amir, A., et al., Organophosphate Poisoning: Demographics, Severity Scores and Outcomes From National Poisoning Control Centre, Karachi. Cureus, 2020. 12(5): p. e8371.

- Albano, G.D., et al., Toxicological Findings of Self-Poisoning Suicidal Deaths: A Systematic Review by Countries. Toxics, 2022. 10(11).

- Dabholkar, S., et al., Suicides by pesticide ingestion in Pakistan and the impact of pesticide regulation. BMC Public Health, 2023. 23(1): p. 676.

- Frengidou, E. Galanis, and C. Malesios, Pesticide Exposure or Pesticide Poisoning and the Risk of Depression in Agricultural Populations: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Agromedicine, 2024. 29(1): p. 91-105.

- Freire, C. and S. Koifman, Pesticides, depression and suicide: a systematic review of the epidemiological evidence. Int J Hyg Environ Health, 2013. 216(4): p. 445-60.

- Tan, M.-Y., et al., Association between exposure to organophosphorus pesticide and suicidal ideation among U.S. adults: A population-based study. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety, 2024. 281: p. 116572.

- Barbosa Junior, M. A. Ramos Huarachi, and A.C. de Francisco, The link between pesticide exposure and suicide in agricultural workers: a systematic review. Rural Remote Health, 2024. 24(2): p. 8190.

- Rother, H.-A., Falling through the regulatory cracks: Street selling of pesticides and poisoning among urban youth in South Africa. International journal of occupational and environmental health, 2010. 16(2): p. 202-13.

- Desye, B., et al., Pesticide safe use practice and acute health symptoms, and associated factors among farmers in developing countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis of an epidemiological evidence. BMC public health, 2024. 24(1): p. 3313-3313.

- Mequanint, C., et al., Practice towards pesticide handling, storage and its associated factors among farmers working in irrigations in Gondar town, Ethiopia, 2019. BMC research notes, 2019. 12(1): p. 709-709.

- Knapke, E.T., et al., Environmental and occupational pesticide exposure and human sperm parameters: A Navigation Guide review. Toxicology, 2022. 465: p. 153017-153017.

- Kassem, H.S. A. Hussein, and H. Ismail, Toward Fraudulent Pesticides in Rural Areas: Do Farmers’ Recognition and Purchasing Behaviors Matter? Agronomy, 2021. 11(9): p. 1882-1882.

- Illicit Pesticides, Organized Crime and Supply Chain Integrity. 2020.

- Gunnell, D., et al., The impact of pesticide regulations on suicide in Sri Lanka. International journal of epidemiology, 2007. 36(6): p. 1235-42.

- Beyuo, J., et al., The implications of pesticide residue in food crops on human health: a critical review. Discover Agriculture, 2024. 2(1): p. 123-123.

- Lambert, W.E., et al., Variation in organophosphate pesticide metabolites in urine of children living in agricultural communities. Environmental health perspectives, 2005. 113(4): p. 504-8.

- Eskenazi, B., et al., Organophosphate pesticide exposure and neurodevelopment in young Mexican-American children. Environmental health perspectives, 2007. 115(5): p. 792-8.

- Rauh, V.A., et al., Brain anomalies in children exposed prenatally to a common organophosphate pesticide. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2012. 109(20): p. 7871-6.

- Slotkin, T.A., et al., Exposure of neonatal rats to parathion elicits sex-selective impairment of acetylcholine systems in brain regions during adolescence and adulthood. Environmental health perspectives, 2008. 116(10): p. 1308-14.

- Matisová, E. and S. Hrouzková, Analysis of endocrine disrupting pesticides by capillary GC with mass spectrometric detection. International journal of environmental research and public health, 2012. 9(9): p. 3166-96.

- Gelb, A.W. and E. Vreede, Availability of halothane is still important in some parts of the world. Can J Anaesth, 2024. 71(10): p. 1427-1428.

- Bar-Klein, G., et al., Isoflurane prevents acquired epilepsy in rat models of temporal lobe epilepsy. Ann.Neurol., 2016. 80(6): p. 896-908.

- Puthillathu, N., et al., Brief isoflurane administration as an adjunct treatment to control organophosphate-induced convulsions and neuropathology. Front Pharmacol, 2023. 14: p. 1293280.

- Li, Q., et al., Intravenous lipid emulsion improves recovery time and quality from isoflurane anaesthesia: a double-blind clinical trial. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol, 2014. 115(2): p. 222-8.

- Yang, H., et al., The Bioequivalence of Emulsified Isoflurane With a New Formulation of Emulsion: A Single-Center, Single-Dose, Double-Blinded, Randomized, Two-Period Crossover Study. Front Pharmacol, 2021. 12: p. 626307.

- Huang, H., et al., A phase I, dose-escalation trial evaluating the safety and efficacy of emulsified isoflurane in healthy human volunteers. Anesthesiology, 2014. 120(3): p. 614-25.

- Krishnan, J.K.S., et al., Isoflurane-lipid emulsion injection as an anticonvulsant and neuroprotectant treatment for nerve agent exposure. Front Pharmacol, 2024. 15: p. 1466351.

- Zhou, J.X., et al., The efficacy and safety of intravenous emulsified isoflurane in rats. Anesth Analg, 2006. 102(1): p. 129-34.

- Li, G. and H. Hu, Protective effects of lipid emulsion on vital organs through the LPS/TLR4 pathway in acute organophosphate poisoning. BMC Pharmacol Toxicol, 2025. 26(1): p. 71.

- Sawyer, T.W., et al., Non-cholinergic intervention of sarin nerve agent poisoning. Toxicology., 2012. 294(2-3): p. 85-93.

- Smith, J.L. A. Tranovich, and N.A. Ebraheim, A comprehensive review of malignant hyperthermia: Preventing further fatalities in orthopedic surgery. J.Orthop., 2018. 15(2): p. 578-580.

- Visoiu, M., et al., Anesthetic drugs and onset of malignant hyperthermia. Anesth.Analg., 2014. 118(2): p. 388-396.

- Santos-Lobato, B.L., New Insights into the Association of Pesticide Exposure and Parkinson’s Disease. Mov Disord, 2025. 40(3): p. 579-580.

- Samareh, A., et al., Pesticide Exposure and Its Association with Parkinson’s Disease: A Case-Control Analysis. Cell Mol Neurobiol, 2024. 44(1): p. 73.

- Wendt, A., Pesticide exposure and Parkinson’s disease in the AGRICAN study. Int J Epidemiol, 2018. 47(3): p. 1006.

- Santos, J.R., et al., Pesticide exposure and the development of Parkinson disease: a systematic review of Brazilian studies. Cad Saude Publica, 2025. 41(4): p. e00011424.

- Wang, Y., et al., Different types of pesticide exposure and lung cancer incidence in the Agricultural Health Study cohort: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Environ Occup Health, 2024. 79(7-8): p. 263-272.

- Ataei, M. and M. Abdollahi, A systematic review of mechanistic studies on the relationship between pesticide exposure and cancer induction. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol, 2022. 456: p. 116280.

- in Gulf War and Health: Volume 1. Depleted Uranium, Sarin, Pyridostigmine Bromide, Vaccines, C.E. Fulco, C.T. Liverman, and H.C. Sox, Editors. 2000: Washington (DC).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).