Submitted:

25 June 2025

Posted:

26 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

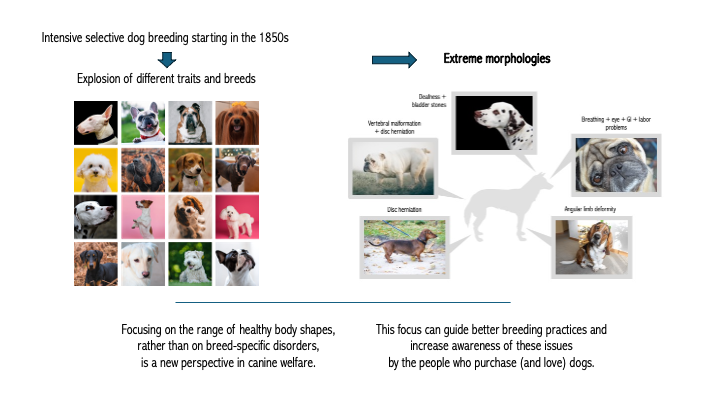

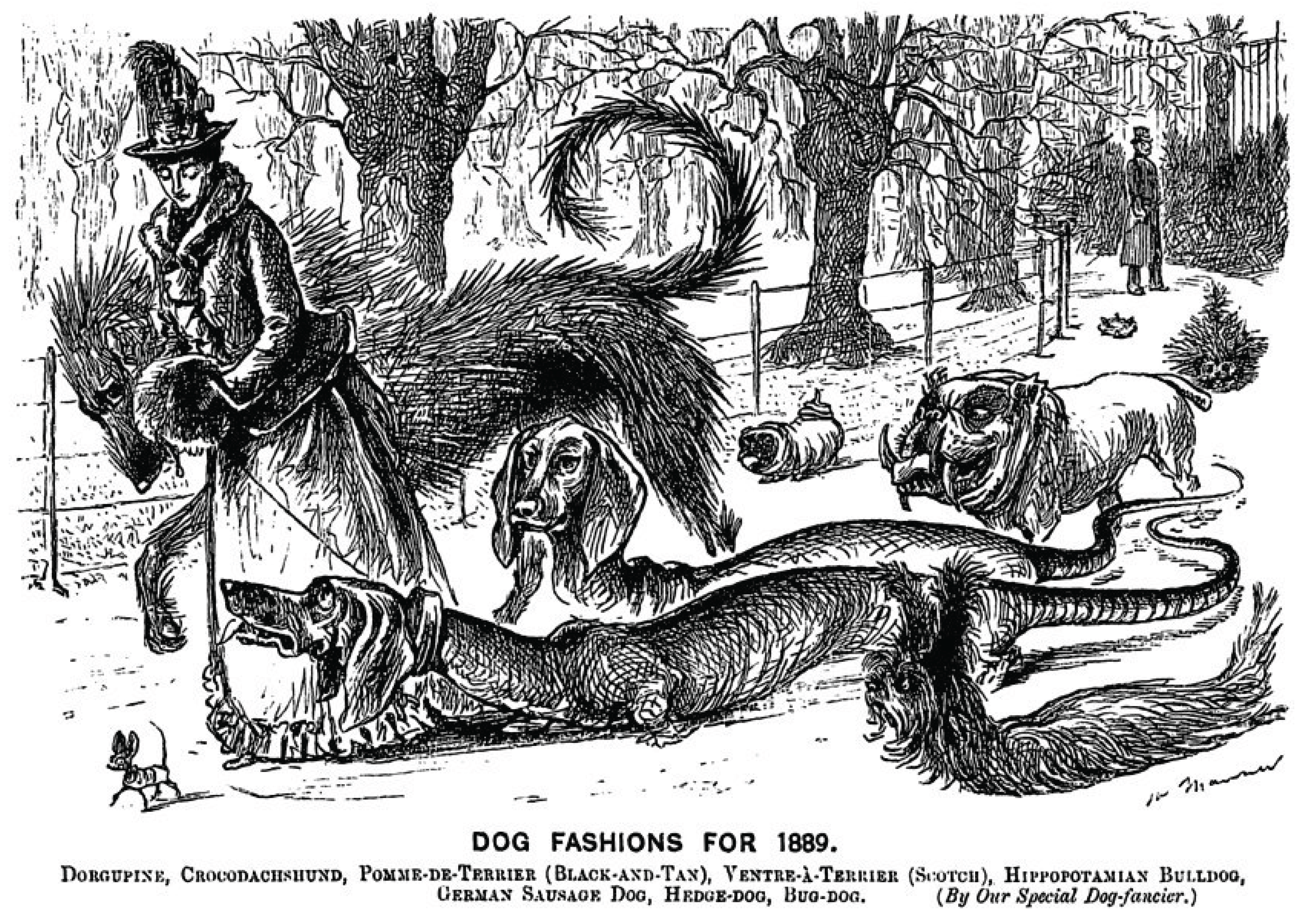

1. Introduction

2. Size

2.1. Lifespan

2.2. Cancer

2.3. Orthopedics

2.4. Heart Disease

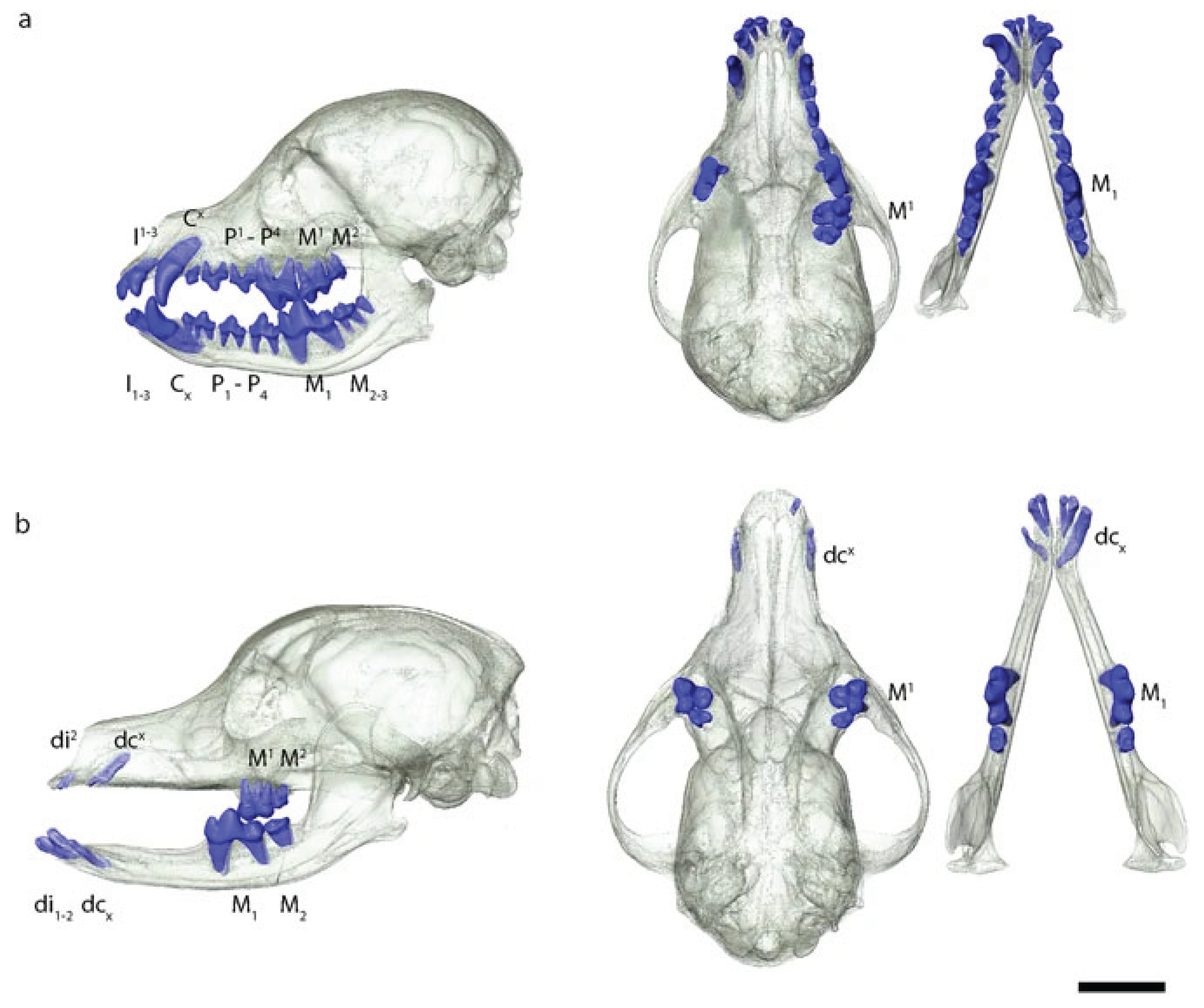

2.5. Dental Disease

2.6. Energy Regulation

2.7. Labor Difficulties

2.8. Behavior

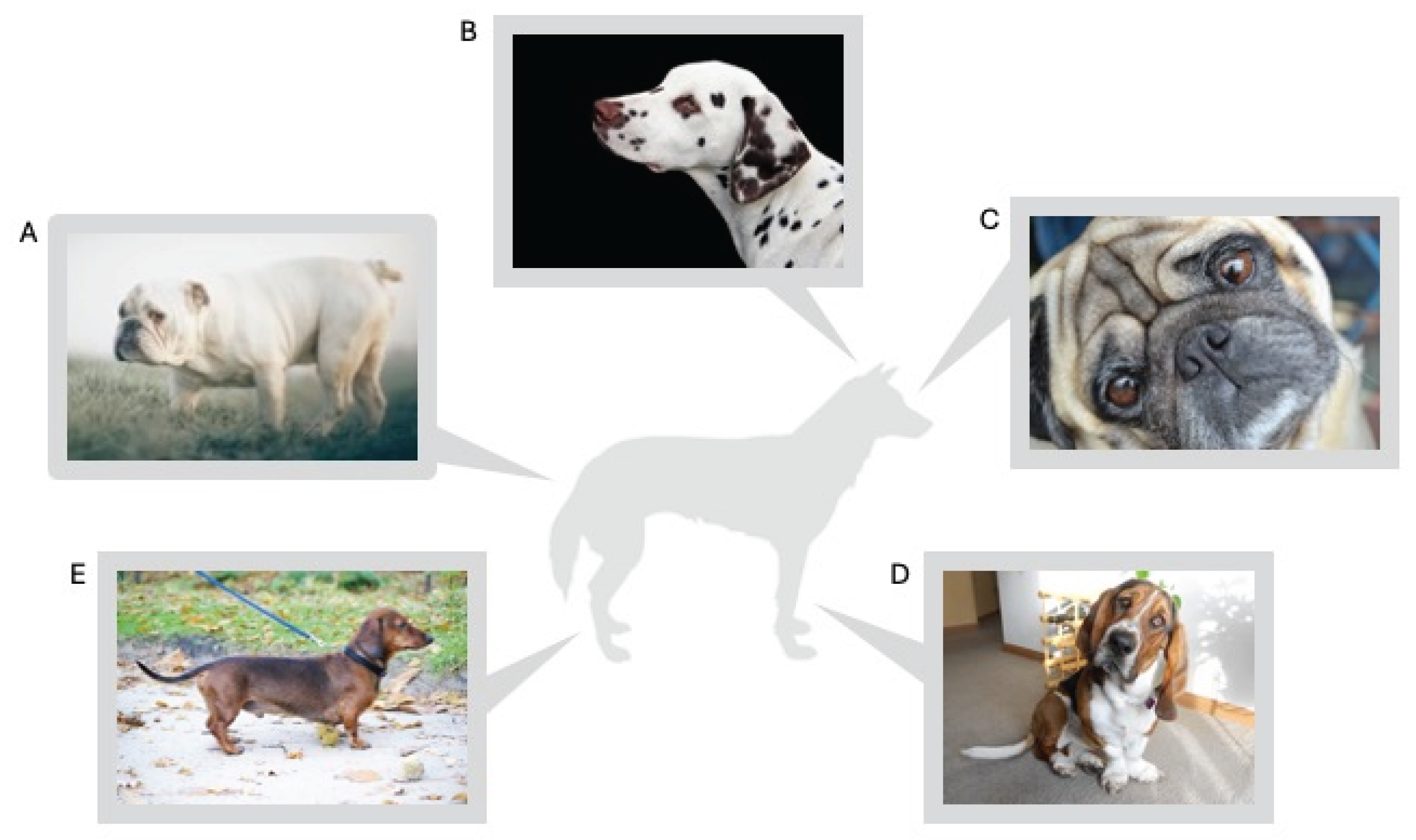

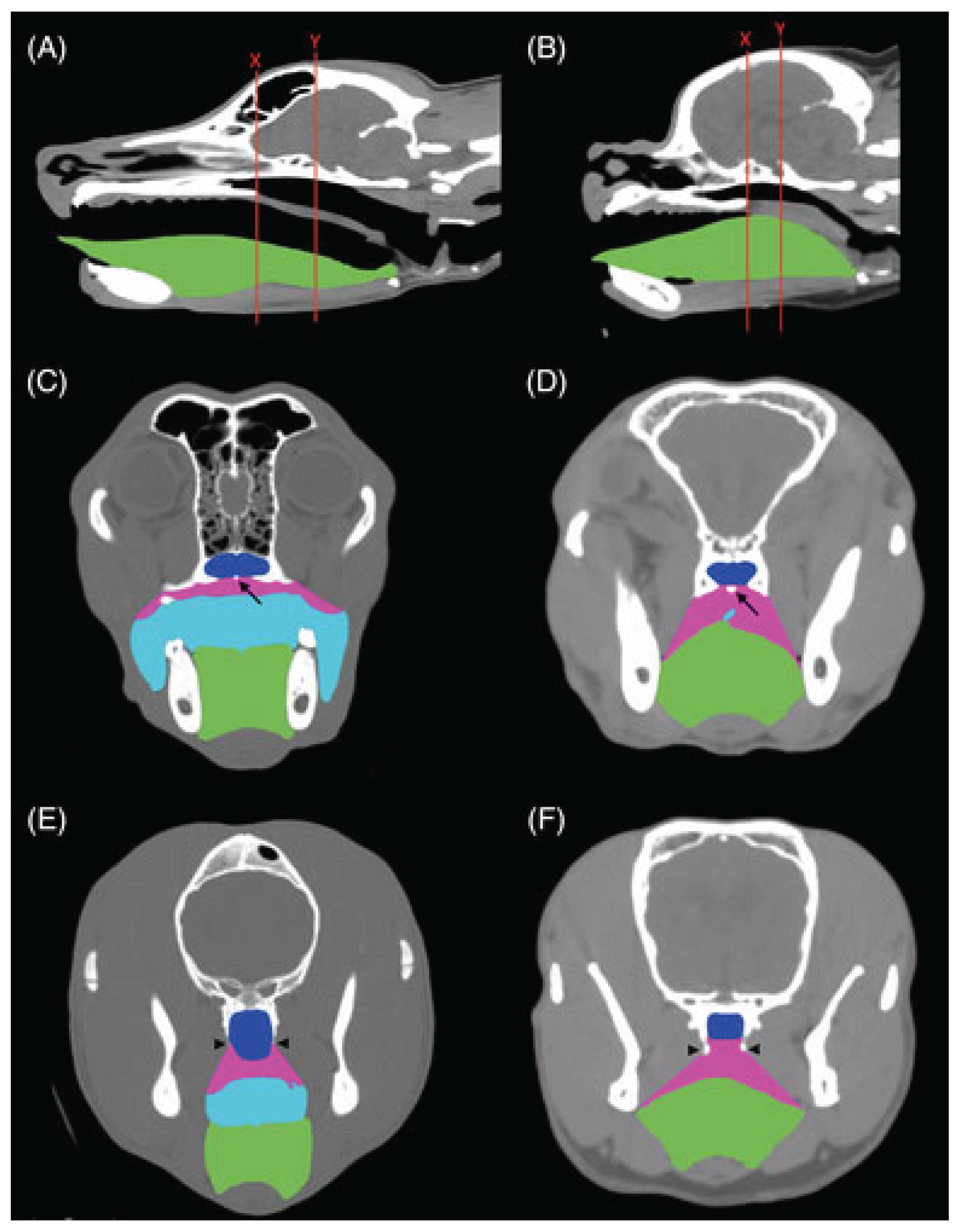

3. Skull Shape

3.1. Brachycephalic Obstructive Airway Syndrome (BOAS)

3.2. Brain and Nervous System Abnormalities

3.3. Eye Disease

3.4. Ear Infections

3.5. Developmental Abnormalities of the Skull

3.6. Labor Difficulties

4. Dwarfism

4.1. Chondrodysplasia

4.2. Chondrodystrophy

5. Chest Depth

6. Skin Folds

6.1. Facial Skin Folds in Brachycephalic Dogs

6.2. Entropion and Ectropion

6.3. Shar pei Skin Folds

7. Tail Length and Curliness

7.1. Neurological Disorders

7.2. Skin Folds Around the Tail in Screw-Tailed Dogs

7.3. Communication

8. Coat

8.1. Ridge

8.2. Hairlessness

8.3. Color and Pattern

9. Discussion

10. Conclusions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- A. L. Shearin, E. A. Ostrander, Canine morphology: hunting for genes and tracking mutations. PLoS Biol 8, e1000310 (2010). [CrossRef]

- P. W. Hedrick, L. Andersson, Are dogs genetically special? Heredity (Edinb) 106, 712–713 (2011). [CrossRef]

- A. H. Freedman, et al., Genome sequencing highlights the dynamic early history of dogs. PLoS Genet 10, e1004016 (2014). [CrossRef]

- L. R. Botigué, et al., Ancient European dog genomes reveal continuity since the Early Neolithic. Nat Commun 8, 16082 (2017). [CrossRef]

- A. R. Perri, et al., Dog domestication and the dual dispersal of people and dogs into the Americas. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 118 (2021). [CrossRef]

- P. Skoglund, E. Ersmark, E. Palkopoulou, L. Dalén, Ancient wolf genome reveals an early divergence of domestic dog ancestors and admixture into high-latitude breeds. Curr Biol 25, 1515–1519 (2015). [CrossRef]

- Z. Fan, et al., Worldwide patterns of genomic variation and admixture in gray wolves. Genome Res 26, 163–173 (2016). [CrossRef]

- A. Bergström, et al., Origins and genetic legacy of prehistoric dogs. Science 370, 557–564 (2020). [CrossRef]

- A. R. Boyko, et al., Complex population structure in African village dogs and its implications for inferring dog domestication history. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106, 13903–13908 (2009). [CrossRef]

- D. Brewer, “Hunting, animal husbandry and diet in ancient Egypt” in A History of the Animal World in the Ancient Near East, (Brill, 2002), pp. 425–456.

- F. Hole, C. Wyllie, The Oldest Depictions of Canines and a Possible Early Breed of Dog in Iran. Paléorient 33, 175–185 (2007). [CrossRef]

- S. H. Lonsdale, Attitudes Towards Animals in Ancient Greece1. Greece Rome 26, 146–159 (1979). [CrossRef]

- A. T. Lin, et al., The history of Coast Salish “woolly dogs” revealed by ancient genomics and Indigenous Knowledge. Science 382, 1303–1308 (2023). [CrossRef]

- C. Jung, D. Pörtl, How old are (Pet) Dog Breeds? Pet Behav. Sci. 29–37 (2019). [CrossRef]

- B. M. vonHoldt, et al., Genome-wide SNP and haplotype analyses reveal a rich history underlying dog domestication. Nature 464, 898–902 (2010). [CrossRef]

- A. Tonoike, et al., Comparison of owner-reported behavioral characteristics among genetically clustered breeds of dog (Canis familiaris). Sci. Rep. 5, 17710 (2015). [CrossRef]

- C. Ameen, et al., Specialized sledge dogs accompanied Inuit dispersal across the North American Arctic. Proc. Biol. Sci. 286, 20191929 (2019). [CrossRef]

- G. Larson, et al., Rethinking dog domestication by integrating genetics, archeology, and biogeography. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 109, 8878–8883 (2012). [CrossRef]

- M. E. Derry, Made to Order: The Designing of Animals (University of Toronto Press, 2022).

- M. Worboys, J.-M. Strange, N. Pemberton, The invention of the modern dog: breed and blood in Victorian Britain (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2018).

- H. F. Proschowsky, et al., A new future for dog breeding. Anim. Welf. 34, e1 (2025). [CrossRef]

- C. Brassard, et al., Unexpected morphological diversity in ancient dogs compared to modern relatives. Proc. Biol. Sci. 289, 20220147 (2022). [CrossRef]

- A. Herzog, Torture breeding, definitions, judgement, pathogenesis. (1997).

- H. Howe, T. Katamine, Using the law to address harmful conformation in dogs-is a breed-specific breed ban the answer?

- Luxembourg, Law of June 27, 2018 on the protection of animals. (2018). Available at: https://legilux.public.lu/eli/etat/leg/loi/2018/06/27/a537/jo [Accessed 13 January 2025].

- Eurogroup for Animals, Landmark ruling against unethical dog breeding in Norway. (2023). Available at: https://www.eurogroupforanimals.org/news/landmark-ruling-against-unethical-dog-breeding-norway [Accessed 13 January 2025].

- W. Woods II, Ojai becomes first U.S. city to ban torture breeding. (2024). Available at: https://www.vcstar.com/story/news/local/california/2024/10/24/ojai-bans-torture-breeding-of-animals/75814787007/ [Accessed 13 January 2025].

- D. S. Mills, et al., Pain and problem behavior in cats and dogs. Animals (Basel) 10, 318 (2020). [CrossRef]

- N. B. Sutter, et al., A single IGF1 allele is a major determinant of small size in dogs. Science 316, 112–115 (2007). [CrossRef]

- B. C. Hoopes, M. Rimbault, D. Liebers, E. A. Ostrander, N. B. Sutter, The insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor (IGF1R) contributes to reduced size in dogs. Mamm. Genome 23, 780–790 (2012). [CrossRef]

- A. R. Boyko, et al., A simple genetic architecture underlies morphological variation in dogs. PLoS Biol. 8, e1000451 (2010). [CrossRef]

- M. Rimbault, et al., Derived variants at six genes explain nearly half of size reduction in dog breeds. Genome Res. 23, 1985–1995 (2013). [CrossRef]

- J. Plassais, et al., Whole genome sequencing of canids reveals genomic regions under selection and variants influencing morphology. Nat. Commun. 10, 1489 (2019). [CrossRef]

- K. Morrill, et al., Ancestry-inclusive dog genomics challenges popular breed stereotypes. Science 376, eabk0639 (2022). [CrossRef]

- M. A. Tryfonidou, et al., Hormonal regulation of calcium homeostasis in two breeds of dogs during growth at different rates. J. Anim. Sci. 81, 1568–1580 (2003). [CrossRef]

- J. K. Kirkwood, The influence of size on the biology of the dog. J. Small Anim. Pract. 26, 97–110 (1985). [CrossRef]

- J. da Silva, B. J. Cross, Dog life spans and the evolution of aging. Am. Nat. 201, E140–E152 (2023). [CrossRef]

- C. Kraus, N. Snyder-Mackler, D. E. L. Promislow, How size and genetic diversity shape lifespan across breeds of purebred dogs. GeroScience 45, 627–643 (2023). [CrossRef]

- C. Kraus, S. Pavard, D. E. L. Promislow, The size–life span trade-off decomposed: why large dogs die young. Am. Nat. 181, 492–505 (2013). [CrossRef]

- D. Bannasch, et al., The effect of inbreeding, body size and morphology on health in dog breeds. Canine Med. Genet. 8, 1–9 (2021). [CrossRef]

- J. P. de Magalhães, J. Costa, G. M. Church, An analysis of the relationship between metabolism, developmental schedules, and longevity using phylogenetic independent contrasts. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 62, 149–160 (2007). [CrossRef]

- K. A. Greer, L. M. Hughes, M. M. Masternak, Connecting serum IGF-1, body size, and age in the domestic dog. Age (Dordr.) 33, 475–483 (2011). [CrossRef]

- D. E. Berryman, J. S. Christiansen, G. Johannsson, M. O. Thorner, J. J. Kopchick, Role of the GH/IGF-1 axis in lifespan and healthspan: lessons from animal models. Growth Horm. IGF Res. 18, 455–471 (2008). [CrossRef]

- J. M. Fleming, K. E. Creevy, D. E. L. Promislow, Mortality in North American dogs from 1984 to 2004: an investigation into age-, size-, and breed-related causes of death. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 25, 187–198 (2011). [CrossRef]

- S. M. Schwartz, et al., Lifetime prevalence of malignant and benign tumours in companion dogs: Cross-sectional analysis of Dog Aging Project baseline survey. Vet. Comp. Oncol. 20, 797–804 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Y. Nam, et al., Dog size and patterns of disease history across the canine age spectrum: Results from the dog aging project. PLoS One 19, e0295840 (2024). [CrossRef]

- L. Nunney, The effect of body size and inbreeding on cancer mortality in breeds of the domestic dog: a test of the multi-stage model of carcinogenesis. R. Soc. Open Sci. 11, 231356 (2024). [CrossRef]

- K. M. Makielski, et al., Risk factors for development of canine and human osteosarcoma: a comparative review. Vet. Sci. 6, 48 (2019). [CrossRef]

- T. T. Samaras, H. Elrick, L. H. Storms, Birthweight, rapid growth, cancer, and longevity: a review. J. Natl. Med. Assoc. 95, 1170 (2003).

- S. Simpson, et al., Comparative review of human and canine osteosarcoma: morphology, epidemiology, prognosis, treatment and genetics. Acta Vet. Scand. 59, 1–11 (2017). [CrossRef]

- D. G. O’Neill, et al., Dog breeds and conformations predisposed to osteosarcoma in the UK: a VetCompass study. Canine Med. Genet. 10, 8 (2023). [CrossRef]

- G. Ru, B. Terracini, L. T. Glickman, Host related risk factors for canine osteosarcoma. Vet. J. 156, 31–39 (1998). [CrossRef]

- I. Zapata, et al., Risk-modeling of dog osteosarcoma genome scans shows individuals with Mendelian-level polygenic risk are common. BMC Genomics 20, 1–14 (2019). [CrossRef]

- M. Harada, K. Akita, Mouse fibroblast growth factor 9 N143T mutation leads to wide chondrogenic condensation of long bones. Histochem. Cell Biol. 153, 215–223 (2020). [CrossRef]

- E. K. Karlsson, et al., Genome-wide analyses implicate 33 loci in heritable dog osteosarcoma, including regulatory variants near CDKN2A/B. Genome Biol. 14, 1–16 (2013). [CrossRef]

- Y. Jiao, Y. Feng, X. Wang, Regulation of tumor suppressor gene CDKN2A and encoded p16-INK4a protein by covalent modifications. Biochemistry (Mosc.) 83, 1289–1298 (2018). [CrossRef]

- R. A. Pettitt, A. J. German, Investigation and management of canine osteoarthritis. In Pract. 37, 1–8 (2015). [CrossRef]

- K. L. Anderson, et al., Prevalence, duration and risk factors for appendicular osteoarthritis in a UK dog population under primary veterinary care. Sci. Rep. 8, 5641 (2018). [CrossRef]

- K. L. Anderson, H. Zulch, D. G. O’Neill, R. L. Meeson, L. M. Collins, Risk factors for canine osteoarthritis and its predisposing arthropathies: a systematic review. Front. Vet. Sci. 7, 220 (2020). [CrossRef]

- D. G. O’Neill, R. L. Meeson, A. Sheridan, D. B. Church, D. C. Brodbelt, The epidemiology of patellar luxation in dogs attending primary-care veterinary practices in England. Canine Genet. Epidemiol. 3, 1–12 (2016). [CrossRef]

- M. D. King, Etiopathogenesis of canine hip dysplasia, prevalence, and genetics. Vet. Clin. North Am. Small Anim. Pract. 47, 753–767 (2017). [CrossRef]

- F. H. Comhaire, F. Snaps, Comparison of two canine registry databases on the prevalence of hip dysplasia by breed and the relationship of dysplasia with body weight and height. Am. J. Vet. Res. 69, 330–333 (2008). [CrossRef]

- M. Ginja, A. M. Silvestre, J. M. Gonzalo-Orden, A. J. A. Ferreira, Diagnosis, genetic control and preventive management of canine hip dysplasia: a review. Vet. J. 184, 269–276 (2010). [CrossRef]

- T. H. Witsberger, J. A. Villamil, L. G. Schultz, A. W. Hahn, J. L. Cook, Prevalence of and risk factors for hip dysplasia and cranial cruciate ligament deficiency in dogs. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 232, 1818–1824 (2008). [CrossRef]

- J. Michelsen, Canine elbow dysplasia: aetiopathogenesis and current treatment recommendations. Vet. J. 196, 12–19 (2013). [CrossRef]

- D. G. O’Neill, D. C. Brodbelt, R. Hodge, D. B. Church, R. L. Meeson, Epidemiology and clinical management of elbow joint disease in dogs under primary veterinary care in the UK. Canine Med. Genet. 7, 1–15 (2020). [CrossRef]

- G. Harasen, Canine cranial cruciate ligament rupture in profile: 2002–2007. Can. Vet. J. 49, 193 (2008). [CrossRef]

- J. M. Duval, S. C. Budsberg, G. L. Flo, J. L. Sammarco, Breed, sex, and body weight as risk factors for rupture of the cranial cruciate ligament in young dogs. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 215, 811–814 (1999). [CrossRef]

- E. J. Comerford, K. Smith, K. Hayashi, Update on the aetiopathogenesis of canine cranial cruciate ligament disease. Vet. Comp. Orthop. Traumatol. 24, 91–98 (2011). [CrossRef]

- G. W. Niebauer, B. Restucci, Etiopathogenesis of canine cruciate ligament disease: a scoping review. Animals (Basel) 13, 187 (2023). [CrossRef]

- H. G. Parker, P. Kilroy-Glynn, Myxomatous mitral valve disease in dogs: does size matter? J. Vet. Cardiol. 14, 19–29 (2012). [CrossRef]

- M. J. Mattin, et al., Degenerative mitral valve disease: Survival of dogs attending primary-care practice in England. Prev. Vet. Med. 122, 436–442 (2015). [CrossRef]

- A. Tidholm, J. Häggström, M. Borgarelli, A. Tarducci, Canine idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy. Part I: aetiology, clinical characteristics, epidemiology and pathology. Vet. J. 162, 92–107 (2001). [CrossRef]

- M. W. S. Martin, M. J. Stafford Johnson, B. Celona, Canine dilated cardiomyopathy: a retrospective study of signalment, presentation and clinical findings in 369 cases. J. Small Anim. Pract. 50, 23–29 (2009). [CrossRef]

- D. G. O’Neill, et al., Epidemiology of periodontal disease in dogs in the UK primary-care veterinary setting. J. Small Anim. Pract. 62, 1051–1061 (2021). [CrossRef]

- C. Wallis, E. K. Saito, C. Salt, L. J. Holcombe, N. G. Desforges, Association of periodontal disease with breed size, breed, weight, and age in pure-bred client-owned dogs in the United States. Vet. J. 275, 105717 (2021). [CrossRef]

- C. Wallis, A. Ivanova, L. J. Holcombe, Persistent deciduous teeth: Association of prevalence with breed, breed size and body weight in pure-bred client-owned dogs in the United States. Res. Vet. Sci. 169, 105161 (2024). [CrossRef]

- M. A. Gioso, F. Shofer, P. S. M. Barros, C. E. Harvey, Mandible and mandibular first molar tooth measurements in dogs: relationship of radiographic height to body weight. J. Vet. Dent. 18, 65–68 (2001). [CrossRef]

- M. Kyllar, B. Doskarova, V. Paral, Morphometric assessment of periodontal tissues in relation to periodontal disease in dogs. J. Vet. Dent. 30, 146–149 (2013). [CrossRef]

- O. Idowu, K. Heading, Hypoglycemia in dogs: Causes, management, and diagnosis. Can. Vet. J. 59, 642 (2018).

- A. G. Jimenez, K. Paul, A. Zafar, A. Ay, Effect of different masses, ages, and coats on the thermoregulation of dogs before and after exercise across different seasons. Vet. Res. Commun. 47, 833–847 (2023). [CrossRef]

- E. J. Hall, A. J. Carter, D. G. O’Neill, Dogs don’t die just in hot cars—exertional heat-related illness (Heatstroke) is a greater threat to UK dogs. Animals (Basel) 10, 1324 (2020). [CrossRef]

- D. G. O’Neill, et al., Canine dystocia in 50 UK first-opinion emergency-care veterinary practices: prevalence and risk factors. Vet. Rec. 181, 88–88 (2017). [CrossRef]

- A. Münnich, U. Küchenmeister, Dystocia in numbers–evidence-based parameters for intervention in the dog: causes for dystocia and treatment recommendations. Reprod. Domest. Anim. 44, 141–147 (2009). [CrossRef]

- K. S. Borge, R. Tønnessen, A. Nødtvedt, A. Indrebø, Litter size at birth in purebred dogs—A retrospective study of 224 breeds. Theriogenology 75, 911–919 (2011). [CrossRef]

- A. J. Cornelius, R. Moxon, J. Russenberger, B. Havlena, S. H. Cheong, Identifying risk factors for canine dystocia and stillbirths. Theriogenology 128, 201–206 (2019). [CrossRef]

- D. Bennett, Canine dystocia—a review of the literature. J. Small Anim. Pract. 15, 101–117 (1974).

- P. D. McGreevy, et al., Dog behavior co-varies with height, bodyweight and skull shape. PLoS One 8, e80529 (2013). [CrossRef]

- I. Zapata, J. A. Serpell, C. E. Alvarez, Genetic mapping of canine fear and aggression. BMC Genomics 17, 1–20 (2016). [CrossRef]

- I. Zapata, A. W. Eyre, C. E. Alvarez, J. A. Serpell, Latent class analysis of behavior across dog breeds reveal underlying temperament profiles. Sci. Rep. 12, 15627 (2022). [CrossRef]

- C. Arhant, H. Bubna-Littitz, A. Bartels, A. Futschik, J. Troxler, Behaviour of smaller and larger dogs: Effects of training methods, inconsistency of owner behaviour and level of engagement in activities with the dog. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 123, 131–142 (2010). [CrossRef]

- A. Bassi, L. Pierantoni, S. Cannas, C. Mariti, Dog’s size affects owners’ behaviour and attitude during dog walking. Dog behavior 2, 1–8 (2016).

- W. S. Helton, N. D. Helton, Physical size matters in the domestic dog’s (Canis lupus familiaris) ability to use human pointing cues. Behav. Processes 85, 77–79 (2010). [CrossRef]

- B. Wilson, J. Serpell, H. Herzog, P. McGreevy, Prevailing clusters of canine behavioural traits in historical US demand for dog breeds (1926–2005). Animals (Basel) 8, 197 (2018). [CrossRef]

- E. E. Hecht, et al., Neurodevelopmental scaling is a major driver of brain–behavior differences in temperament across dog breeds. Brain Struct. Funct. 226, 2725–2739 (2021). [CrossRef]

- B. L. Finlay, R. B. Darlington, Linked regularities in the development and evolution of mammalian brains. Science 268, 1578–1584 (1995). [CrossRef]

- B. L. Finlay, R. B. Darlington, N. Nicastro, Developmental structure in brain evolution. Behav. Brain Sci. 24, 263–278 (2001). [CrossRef]

- B. L. Finlay, K. Huang, Developmental duration as an organizer of the evolving mammalian brain: scaling, adaptations, and exceptions. Evol. Dev. 22, 181–195 (2020). [CrossRef]

- F. Pirrone, et al., Correlation between the size of companion dogs and the profile of the owner: A cross-sectional study in ItalyMarian. Dog behavior 1, 32–43 (2015). [CrossRef]

- D. G. O’Neill, et al., Unravelling the health status of brachycephalic dogs in the UK using multivariable analysis. Sci. Rep. 10, 17251 (2020). [CrossRef]

- R. M. A. Packer, D. G. O’Neill, F. Fletcher, M. J. Farnworth, Great expectations, inconvenient truths, and the paradoxes of the dog-owner relationship for owners of brachycephalic dogs. PLoS One 14, e0219918 (2019). [CrossRef]

- R. M. A. Packer, A. Hendricks, C. C. Burn, Do dog owners perceive the clinical signs related to conformational inherited disorders as “normal”for the breed? A potential constraint to improving canine welfare. Anim. Welf. 21, 81–93 (2012). [CrossRef]

- R. M. A. Packer, A. Wade, J. Neufuss, Nothing Could Put Me Off: Assessing the Prevalence and Risk Factors for Perceptual Barriers to Improving the Welfare of Brachycephalic Dogs. Pets 1, 458–484 (2024). [CrossRef]

- E. S. Paul, et al., That brachycephalic look: Infant-like facial appearance in short-muzzled dog breeds. Anim. Welf. 32, e5 (2023). [CrossRef]

- D. Krainer, G. Dupré, Brachycephalic obstructive airway syndrome. Vet. Clin. North Am. Small Anim. Pract. 52, 749–780 (2022). [CrossRef]

- S. Mitze, V. R. Barrs, J. A. Beatty, S. Hobi, P. M. Bęczkowski, Brachycephalic obstructive airway syndrome: much more than a surgical problem. Vet. Q. 42, 213–223 (2022). [CrossRef]

- K. J. Ekenstedt, K. R. Crosse, M. Risselada, Canine brachycephaly: anatomy, pathology, genetics and welfare. J. Comp. Pathol. 176, 109–115 (2020). [CrossRef]

- J. Grand, S. Bureau, Structural characteristics of the soft palate and meatus nasopharyngeus in brachycephalic and non-brachycephalic dogs analysed by CT. J. Small Anim. Pract. 52, 232–239 (2011). [CrossRef]

- D. A. Barker, C. Rubiños, O. Taeymans, J. L. Demetriou, Magnetic resonance imaging evaluation of olfactory bulb angle and soft palate dimensions in brachycephalic and nonbrachycephalic dogs. Am. J. Vet. Res. 79, 170–176 (2018). [CrossRef]

- B. A. Jones, B. J. Stanley, N. C. Nelson, The impact of tongue dimension on air volume in brachycephalic dogs. Vet. Surg. 49, 512–520 (2020). [CrossRef]

- J. A. Ginn, M. S. A. Kumar, B. C. McKiernan, B. E. Powers, Nasopharyngeal turbinates in brachycephalic dogs and cats. J. Am. Anim. Hosp. Assoc. 44, 243–249 (2008). [CrossRef]

- R. Schuenemann, G. U. Oechtering, Inside the brachycephalic nose: intranasal mucosal contact points. J. Am. Anim. Hosp. Assoc. 50, 149–158 (2014). [CrossRef]

- M. Auger, K. Alexander, G. Beauchamp, M. Dunn, Use of CT to evaluate and compare intranasal features in brachycephalic and normocephalic dogs. J. Small Anim. Pract. 57, 529–536 (2016). [CrossRef]

- F. J. Fasanella, J. M. Shivley, J. L. Wardlaw, S. Givaruangsawat, Brachycephalic airway obstructive syndrome in dogs: 90 cases (1991–2008). J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 237, 1048–1051 (2010). [CrossRef]

- A. Conte, S. Morabito, R. Dennis, D. Murgia, Computed tomographic comparison of esophageal hiatal size in brachycephalic and non-brachycephalic breed dogs. Vet. Surg. 49, 1509–1516 (2020). [CrossRef]

- E. J. Reeve, D. Sutton, E. J. Friend, C. M. R. Warren-Smith, Documenting the prevalence of hiatal hernia and oesophageal abnormalities in brachycephalic dogs using fluoroscopy. J. Small Anim. Pract. 58, 703–708 (2017). [CrossRef]

- L. Lilja-Maula, et al., Comparison of submaximal exercise test results and severity of brachycephalic obstructive airway syndrome in English bulldogs. Vet. J. 219, 22–26 (2017). [CrossRef]

- K. Schmidt-Nielsen, W. L. Bretz, C. R. Taylor, Panting in dogs: unidirectional air flow over evaporative surfaces. Science 169, 1102–1104 (1970). [CrossRef]

- R. Oshita, S. Katayose, E. Kanai, S. Takagi, Assessment of nasal structure using CT imaging of brachycephalic dog breeds. Animals (Basel) 12, 1636 (2022). [CrossRef]

- I. Carrera, R. Dennis, D. J. Mellor, J. Penderis, M. Sullivan, Use of magnetic resonance imaging for morphometric analysis of the caudal cranial fossa in Cavalier King Charles Spaniels. Am. J. Vet. Res. 70, 340–345 (2009). [CrossRef]

- S. P. Knowler, et al., Quantitative analysis of Chiari-like malformation and syringomyelia in the Griffon Bruxellois dog. PLoS One 9, e88120 (2014). [CrossRef]

- C. Rusbridge, New considerations about Chiari-like malformation, syringomyelia and their management. In Pract. 42, 252–267 (2020). [CrossRef]

- C. Rusbridge, P. Knowler, The need for head space: brachycephaly and cerebrospinal fluid disorders. Life (Basel) 11, 139 (2021). [CrossRef]

- S. P. Knowler, et al., Facial changes related to brachycephaly in Cavalier King Charles Spaniels with Chiari-like malformation associated pain and secondary syringomyelia. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 34, 237–246 (2020). [CrossRef]

- C. Rusbridge, H. Carruthers, M. Dubé, M. Holmes, N. D. Jeffery, Syringomyelia in cavalier King Charles spaniels: the relationship between syrinx dimensions and pain. J. Small Anim. Pract. 48, 432–436 (2007). [CrossRef]

- A. C. Freeman, et al., Chiari-like malformation and syringomyelia in American Brussels griffon dogs. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 28, 1551–1559 (2014). [CrossRef]

- A. Kiviranta, C. Rusbridge, A. K. Lappalainen, J. J. T. Junnila, T. S. Jokinen, Persistent fontanelles in Chihuahuas. Part I. Distribution and clinical relevance. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 35, 1834–1847 (2021). [CrossRef]

- I. N. Plessas, et al., Long-term outcome of Cavalier King Charles spaniel dogs with clinical signs associated with Chiari-like malformation and syringomyelia. Vet. Rec. 171, 501–501 (2012). [CrossRef]

- S. Sanchis-Mora, et al., Dogs attending primary-care practice in England with clinical signs suggestive of Chiari-like malformation/syringomyelia. Vet. Rec. 179, 436–436 (2016). [CrossRef]

- M. S. Thøfner, et al., Prevalence and heritability of symptomatic syringomyelia in Cavalier King Charles Spaniels and long-term outcome in symptomatic and asymptomatic littermates. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 29, 243–250 (2015). [CrossRef]

- K. Wijnrocx, et al., Twelve years of chiari-like malformation and syringomyelia scanning in Cavalier King Charles Spaniels in the Netherlands: Towards a more precise phenotype. PLoS One 12, e0184893 (2017). [CrossRef]

- T. J. Mitchell, S. P. Knowler, H. van den Berg, J. Sykes, C. Rusbridge, Syringomyelia: determining risk and protective factors in the conformation of the Cavalier King Charles Spaniel dog. Canine Genet. Epidemiol. 1, 1–12 (2014). [CrossRef]

- S. Cerda-Gonzalez, N. J. Olby, E. H. Griffith, Medullary position at the craniocervical junction in mature cavalier king charles spaniels: relationship with neurologic signs and syringomyelia. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 29, 882–886 (2015). [CrossRef]

- J. Couturier, D. Rault, L. Cauzinille, Chiari-like malformation and syringomyelia in normal cavalier King Charles spaniels: a multiple diagnostic imaging approach. J. Small Anim. Pract. 49, 438–443 (2008). [CrossRef]

- J. E. Parker, S. P. Knowler, C. Rusbridge, E. Noorman, N. D. Jeffery, Prevalence of asymptomatic syringomyelia in Cavalier King Charles spaniels. Vet. Rec. 168, 667–667 (2011). [CrossRef]

- T. R. Pedersen, et al., Clinical predictors of syringomyelia in Cavalier King Charles Spaniels with chiari-like malformation based on owners’ observations. Acta Vet. Scand. 66, 5 (2024). [CrossRef]

- T. Lewis, C. Rusbridge, P. Knowler, S. Blott, J. A. Woolliams, Heritability of syringomyelia in Cavalier King Charles spaniels. Vet. J. 183, 345–347 (2010). [CrossRef]

- C. Limpens, V. T. M. Smits, H. Fieten, P. J. J. Mandigers, The effect of MRI-based screening and selection on the prevalence of syringomyelia in the Dutch and Danish Cavalier King Charles Spaniels. Front. Vet. Sci. 11, 1326621 (2024). [CrossRef]

- A. Prodger, S. Khan, G. Harris, Prevalence of structural and idiopathic epilepsy in brachycephalic and non-brachycephalic dogs in the context of the International Veterinary Epilepsy Task Force guidelines. J. Small Anim. Pract. (2025). [CrossRef]

- L. Sebbag, R. F. Sanchez, The pandemic of ocular surface disease in brachycephalic dogs: The brachycephalic ocular syndrome. Vet. Ophthalmol. 26, 31–46 (2023). [CrossRef]

- S. V. Palmer, F. E. Gomes, J. A. A. McArt, Ophthalmic disorders in a referral population of seven breeds of brachycephalic dogs: 970 cases (2008–2017). J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 259, 1318–1324 (2021). [CrossRef]

- D. G. O’Neill, M. M. Lee, D. C. Brodbelt, D. B. Church, R. F. Sanchez, Corneal ulcerative disease in dogs under primary veterinary care in England: epidemiology and clinical management. Canine Genet. Epidemiol. 4, 1–12 (2017). [CrossRef]

- R. M. A. Packer, A. Hendricks, C. C. Burn, Impact of facial conformation on canine health: corneal ulceration. PLoS One 10, e0123827 (2015). [CrossRef]

- R. M. A. Packer, A. Hendricks, M. S. Tivers, C. C. Burn, Impact of facial conformation on canine health: brachycephalic obstructive airway syndrome. PLoS One 10, e0137496 (2015). [CrossRef]

- D. G. O’Neill, et al., Disorders of Bulldogs under primary veterinary care in the UK in 2013. PLoS One 14, e0217928 (2019). [CrossRef]

- D. G. O’Neill, E. C. Darwent, D. B. Church, D. C. Brodbelt, Demography and health of Pugs under primary veterinary care in England. Canine Genet. Epidemiol. 3, 1–12 (2016). [CrossRef]

- T. Töpfer, C. Köhler, S. Rösch, G. Oechtering, Brachycephaly in French bulldogs and pugs is associated with narrow ear canals. Vet. Dermatol. 33, 214–e60 (2022). [CrossRef]

- R. Salgüero, M. Herrtage, M. Holmes, P. Mannion, J. Ladlow, Comparison between computed tomographic characteristics of the middle ear in nonbrachycephalic and brachycephalic dogs with obstructive airway syndrome. Vet. Radiol. Ultrasound 57, 137–143 (2016). [CrossRef]

- W. Stern-Bertholtz, L. Sjöström, N. W. Håkanson, Primary secretory otitis media in the Cavalier King Charles spaniel: a review of 61 cases. J. Small Anim. Pract. 44, 253–256 (2003). [CrossRef]

- M. V. Estevam, et al., Congenital malformations in brachycephalic dogs: A retrospective study. Front. Vet. Sci. 9, 981923 (2022). [CrossRef]

- N. Roman, P. C. Carney, N. Fiani, S. Peralta, Incidence patterns of orofacial clefts in purebred dogs. PLoS One 14, e0224574 (2019). [CrossRef]

- S. Peralta, R. D. Campbell, N. Fiani, K. H. Kan-Rohrer, F. J. M. Verstraete, Outcomes of surgical repair of congenital palatal defects in dogs. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 253, 1445–1451 (2018). [CrossRef]

- K. M. Kelly, J. Bardach, “Biologic basis of cleft palate and palatal surgery” in Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery in Dogs and Cats, (Elsevier, 2012), pp. 343–350.

- A. Nemec, L. Daniaux, E. Johnson, S. Peralta, F. J. M. Verstraete, Craniomaxillofacial abnormalities in dogs with congenital palatal defects: computed tomographic findings. Vet. Surg. 44, 417–422 (2015). [CrossRef]

- S. Peralta, A. Nemec, N. Fiani, F. J. M. Verstraete, Staged double-layer closure of palatal defects in 6 dogs. Vet. Surg. 44, 423–431 (2015). [CrossRef]

- K. M. Evans, V. J. Adams, Proportion of litters of purebred dogs born by caesarean section. J. Small Anim. Pract. 51, 113–118 (2010). [CrossRef]

- E. Wydooghe, E. Berghmans, T. Rijsselaere, A. Van Soom, International breeder inquiry into the reproduction of the English bulldog. Vlaams Diergeneeskd. Tijdschr. 82 (2013).

- A. Eneroth, C. Linde-Forsberg, M. Uhlhorn, M. Hall, Radiographic pelvimetry for assessment of dystocia in bitches: a clinical study in two terrier breeds. J. Small Anim. Pract. 40, 257–264 (1999). [CrossRef]

- A. Bergström, A. N. E. Nødtvedt, A. Lagerstedt, A. Egenvall, Incidence and breed predilection for dystocia and risk factors for cesarean section in a Swedish population of insured dogs. Vet. Surg. 35, 786–791 (2006). [CrossRef]

- D. Bannasch, et al., The effects of FGF4 retrogenes on canine morphology. Genes (Basel) 13, 325 (2022). [CrossRef]

- H. G. Parker, et al., An expressed fgf4 retrogene is associated with breed-defining chondrodysplasia in domestic dogs. Science 325, 995–998 (2009). [CrossRef]

- H. G. Parker, A. Harris, D. L. Dreger, B. W. Davis, E. A. Ostrander, The bald and the beautiful: hairlessness in domestic dog breeds. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 372, 20150488 (2017). [CrossRef]

- S. Martínez, R. Fajardo, J. Valdés, R. Ulloa-Arvizu, R. Alonso, Histopathologic study of long-bone growth plates confirms the basset hound as an osteochondrodysplastic breed. Can. J. Vet. Res. 71, 66 (2007).

- A. K. Lappalainen, et al., Breed-typical front limb angular deformity is associated with clinical findings in three chondrodysplastic dog breeds. Front. Vet. Sci. 9, 1099903 (2023). [CrossRef]

- T. W. Kwan, D. J. Marcellin-Little, O. L. A. Harrysson, Correction of biapical radial deformities by use of bi-level hinged circular external fixation and distraction osteogenesis in 13 dogs. Vet. Surg. 43, 316–329 (2014). [CrossRef]

- R. E. Lau, Inherited premature closure of the distal ulnar physis. (1977).

- C. B. Carrig, Growth abnormalities of the canine radius and ulna. (1983). [CrossRef]

- D. B. Fox, J. L. Tomlinson, J. L. Cook, L. M. Breshears, Principles of uniapical and biapical radial deformity correction using dome osteotomies and the center of rotation of angulation methodology in dogs. Vet. Surg. 35, 67–77 (2006). [CrossRef]

- J. Temwichitr, et al., Evaluation of radiographic and genetic aspects of hereditary subluxation of the radial head in Bouviers des Flandres. Am. J. Vet. Res. 71, 884–890 (2010). [CrossRef]

- J. L. Knapp, J. L. Tomlinson, D. B. Fox, Classification of angular limb deformities affecting the canine radius and ulna using the center of rotation of angulation method. Vet. Surg. 45, 295–302 (2016). [CrossRef]

- A. K. Lappalainen, T. Hyvärinen, J. Junnila, O. Laitinen-Vapaavuori, Radiographic evaluation of elbow incongruity in Skye terriers. J. Small Anim. Pract. 57, 96–99 (2016). [CrossRef]

- L. F. H. Theyse, G. Voorhout, H. A. W. Hazewinkel, Prognostic factors in treating antebrachial growth deformities with a lengthening procedure using a circular external skeletal fixation system in dogs. Vet. Surg. 34, 424–435 (2005). [CrossRef]

- American Kennel Club, Dachshund Dog Breed Information. Available at: https://www.akc.org/dog-breeds/dachshund/ [Accessed 2024].

- Skye Terrier Club of America, Skye Terrier Breed Standard. Available at: https://stca.us/about-skye-terriers/skye-terrier-breed-standard/.

- Cardigan Welsh Corgi Club of America, Official Standard of the Cardigan Welsh Corgi. Available at: https://cardigancorgis.com/cwcca/breed/standard [Accessed 2024].

- American Kennel Club, Official standard for the Basset Hound. Available at: https://images.akc.org/pdf/breeds/standards/BassetHound.pdf [Accessed 2024].

- The Basset Hound Club of America, Inc, Pocket guide to the Basset Hound: an aid for judges. Available at: https://basset-bhca.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/Pocket-Guide-3112015.pdf [Accessed 2024].

- E. A. Brown, et al., FGF4 retrogene on CFA12 is responsible for chondrodystrophy and intervertebral disc disease in dogs. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 114, 11476–11481 (2017). [CrossRef]

- K. Batcher, et al., Phenotypic effects of FGF4 retrogenes on intervertebral disc disease in dogs. Genes (Basel) 10, 435 (2019). [CrossRef]

- N. Bergknut, et al., Intervertebral disc degeneration in the dog. Part 1: Anatomy and physiology of the intervertebral disc and characteristics of intervertebral disc degeneration. Vet. J. 195, 282–291 (2013). [CrossRef]

- N. D. Jeffery, J. M. Levine, N. J. Olby, V. M. Stein, Intervertebral disk degeneration in dogs: consequences, diagnosis, treatment, and future directions. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 27, 1318–1333 (2013). [CrossRef]

- H.-J. Hansen, A pathologic-anatomical study on disc degeneration in dog: With special reference to the so-called enchondrosis intervertebralis. Acta Orthop. Scand. 23, 1–130 (1952). [CrossRef]

- V. L. J. Reunanen, T. S. Jokinen, M. K. Hytönen, J. J. T. Junnila, A. K. Lappalainen, Evaluation of intervertebral disc degeneration in young adult asymptomatic Dachshunds with magnetic resonance imaging and radiography. Acta Vet. Scand. 65, 42 (2023). [CrossRef]

- L. A. Smolders, et al., Intervertebral disc degeneration in the dog. Part 2: chondrodystrophic and non-chondrodystrophic breeds. Vet. J. 195, 292–299 (2013). [CrossRef]

- R. M. A. Packer, A. Hendricks, H. A. Volk, N. K. Shihab, C. C. Burn, How long and low can you go? Effect of conformation on the risk of thoracolumbar intervertebral disc extrusion in domestic dogs. PLoS One 8, e69650 (2013). [CrossRef]

- R. M. A. Packer, I. J. Seath, D. G. O’Neill, S. De Decker, H. A. Volk, DachsLife 2015: an investigation of lifestyle associations with the risk of intervertebral disc disease in Dachshunds. Canine Genet. Epidemiol. 3, 1–15 (2016). [CrossRef]

- P. J. Dickinson, D. L. Bannasch, Current understanding of the genetics of intervertebral disc degeneration. Front. Vet. Sci. 7, 431 (2020). [CrossRef]

- A. K. Lappalainen, E. Vaittinen, J. Junnila, O. Laitinen-Vapaavuori, Intervertebral disc disease in Dachshunds radiographically screened for intervertebral disc calcifications. Acta Vet. Scand. 56, 1–7 (2014). [CrossRef]

- B. A. Brisson, S. L. Moffatt, S. L. Swayne, J. M. Parent, Recurrence of thoracolumbar intervertebral disk extrusion in chondrodystrophic dogs after surgical decompression with or without prophylactic enestration: 265 cases (1995–1999). J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 224, 1808–1814 (2004). [CrossRef]

- P. D. Mayhew, et al., Risk factors for recurrence of clinical signs associated with thoracolumbar intervertebral disk herniation in dogs: 229 cases (1994–2000). J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 225, 1231–1236 (2004). [CrossRef]

- J. M. Levine, et al., Owner-perceived, weighted quality-of-life assessments in dogs with spinal cord injuries. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 233, 931–935 (2008). [CrossRef]

- M. U. Ball, J. A. McGuire, S. F. Swaim, B. F. Hoerlein, Patterns of occurrence of disk disease among registered dachshunds. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 180, 519–522 (1982). [CrossRef]

- UC Davis Veterinary Medicine Veterinary Genetics Laboratory, Chondrodystrophy (CDDY and IVDD) and Chondrodysplasia (CDPA). Available at: https://vgl.ucdavis.edu/test/cddy-cdpa [Accessed 2024].

- L. T. Glickman, N. W. Glickman, C. M. Pérez, D. B. Schellenberg, G. C. Lantz, Analysis of risk factors for gastric dilatation and dilatation-volvulus in dogs. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 204, 1465–1471 (1994). [CrossRef]

- L. Glickman, et al., Radiological assessment of the relationship between thoracic conformation and the risk of gastric dilatation-volvulus in dogs. Vet. Radiol. Ultrasound 37, 174–180 (1996). [CrossRef]

- R. H. Schaible, et al., Predisposition to gastric dilatation-volvulus in relation to genetics of thoracic conformation in Irish setters. J. Am. Anim. Hosp. Assoc. 33, 379–383 (1997). [CrossRef]

- D. Schellenberg, Q. Yi, N. W. Glickman, L. T. Glickman, Influence of thoracic conformation and genetics on the risk of gastric dilatation-volvulus in Irish setters. J. Am. Anim. Hosp. Assoc. 34, 64–73 (1998). [CrossRef]

- J. S. Bell, Inherited and predisposing factors in the development of gastric dilatation volvulus in dogs. Top. Companion Anim. Med. 29, 60–63 (2014). [CrossRef]

- C. R. Sharp, E. A. Rozanski, Cardiovascular and systemic effects of gastric dilatation and volvulus in dogs. Top. Companion Anim. Med. 29, 67–70 (2014). [CrossRef]

- A. Pike, T. M. Smalle, Gastric dilatation-volvulus in dogs: A review of the literature from 2000-2020. Aust. Vet. Pr. 52 (2022).

- L. T. Glickman, N. W. Glickman, D. B. Schellenberg, M. Raghavan, T. Lee, Non-dietary risk factors for gastric dilatation-volvulus in large and giant breed dogs. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 217, 1492–1499 (2000). [CrossRef]

- D. G. O’neill, et al., Gastric dilation-volvulus in dogs attending UK emergency-care veterinary practices: prevalence, risk factors and survival. J. Small Anim. Pract. 58, 629–638 (2017). [CrossRef]

- K. K. Song, S. E. Goldsmid, J. Lee, D. J. Simpson, Retrospective analysis of 736 cases of canine gastric dilatation volvulus. Aust. Vet. J. 98, 232–238 (2020). [CrossRef]

- The American Kennel Club, Official Standard of the German Shepherd Dog. Available at: https://images.akc.org/pdf/breeds/standards/GermanShepherdDog.pdf [Accessed 23 January 2025].

- The American Kennel Club, The Official Standard of the Great Dane. Available at: https://images.akc.org/pdf/breeds/standards/GreatDane.pdf [Accessed 23 January 2025].

- S. Hobi, V. R. Barrs, P. M. Bęczkowski, Dermatological problems of brachycephalic dogs. Animals (Basel) 13, 2016 (2023). [CrossRef]

- D. G. O’NeillI, D. Rowe, D. C. Brodbelt, C. Pegram, A. Hendricks, Ironing out the wrinkles and folds in the epidemiology of skin fold dermatitis in dog breeds in the UK. Sci. Rep. 12, 10553 (2022). [CrossRef]

- D. G. O’Neill, et al., Is it now time to iron out the wrinkles? Health of Shar Pei dogs under primary veterinary care in the UK. Canine Med. Genet. 10, 11 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Universities Federation for Animal Welfare, Genetic Welfare Problems of Companion Animals - English Bulldog. Available at: https://www.ufaw.org.uk/dogs/english-bulldog [Accessed 2024].

- F. C. Stades, K. N. Gelatt, Diseases and surgery of the canine eyelid. Essentials of Veterinary Ophthalmology 22, 53 (2008).

- A. Van Der Woerdt, Adnexal surgery in dogs and cats. Vet. Ophthalmol. 7, 284–290 (2004).

- E. A. Giuliano, Don’t worry; he’ll grow out of his entropion… (BSAVA Library, 2015).

- J. Vidt, Eye Tacking. Available at: https://cspca.com/eye-tacking/ [Accessed 2024].

- A. Guandalini, et al., Epidemiology of ocular disorders presumed to be inherited in three large Italian dog breeds in Italy. Vet. Ophthalmol. 20, 420–426 (2017). [CrossRef]

- M. Olsson, et al., A novel unstable duplication upstream of HAS2 predisposes to a breed-defining skin phenotype and a periodic fever syndrome in Chinese Shar-Pei dogs. PLoS Genet. 7, e1001332 (2011). [CrossRef]

- American Kennel Club, Official standard of the Chinese Shar-Pei. Available at: https://images.akc.org/pdf/breeds/standards/ChineseSharPei.pdf [Accessed 2024].

- J. L. Bouma, Kyphosis and kyphoscoliosis associated with congenital malformations of the thoracic vertebral bodies in dogs. Congenital Abnormalities of the Skull, Vertebral Column, and Central Nervous System, An Issue of Veterinary Clinics of North America: Small Animal Practice, E-Book: Congenital Abnormalities of the Skull, Vertebral Column, and Central Nervous System, An Issue of Veterinary Clinics of North America: Small Animal Practice, E-Book 46, 295 (2016). [CrossRef]

- R. Ryan, R. Gutierrez-Quintana, G. Ter Haar, S. De Decker, Prevalence of thoracic vertebral malformations in French bulldogs, Pugs and English bulldogs with and without associated neurological deficits. Vet. J. 221, 25–29 (2017). [CrossRef]

- S. Bertram, G. Ter Haar, S. De Decker, Congenital malformations of the lumbosacral vertebral column are common in neurologically normal French bulldogs, English bulldogs, and pugs, with breed-specific differences. Vet. Radiol. Ultrasound 60, 400–408 (2019). [CrossRef]

- S. De Decker, C. Rohdin, R. Gutierrez-Quintana, Vertebral and spinal malformations in small brachycephalic dog breeds: Current knowledge and remaining questions. Vet. J. 106095 (2024). [CrossRef]

- T. A. Mansour, et al., Whole genome variant association across 100 dogs identifies a frame shift mutation in DISHEVELLED 2 which contributes to Robinow-like syndrome in Bulldogs and related screw tail dog breeds. PLoS Genet. 14, e1007850 (2018). [CrossRef]

- J. E. Niskanen, et al., Canine DVL2 variant contributes to brachycephalic phenotype and caudal vertebral anomalies. Hum. Genet. 140, 1535–1545 (2021). [CrossRef]

- C. Rohdin, et al., Presence of thoracic and lumbar vertebral malformations in pugs with and without chronic neurological deficits. Vet. J. 241, 24–30 (2018). [CrossRef]

- P. Moissonnier, P. Gossot, S. Scotti, Thoracic kyphosis associated with hemivertebra. Vet. Surg. 40, 1029–1032 (2011). [CrossRef]

- J. Guevar, et al., Computer-assisted radiographic calculation of spinal curvature in brachycephalic “screw-tailed” dog breeds with congenital thoracic vertebral malformations: reliability and clinical evaluation. PLoS One 9, e106957 (2014). [CrossRef]

- T. Aikawa, S. Kanazono, Y. Yoshigae, N. J. H. Sharp, K. R. Muñana, Vertebral stabilization using positively threaded profile pins and polymethylmethacrylate, with or without laminectomy, for spinal canal stenosis and vertebral instability caused by congenital thoracic vertebral anomalies. Vet. Surg. 36, 432–441 (2007). [CrossRef]

- M. Charalambous, et al., Surgical treatment of dorsal hemivertebrae associated with kyphosis by spinal segmental stabilisation, with or without decompression. Vet. J. 202, 267–273 (2014). [CrossRef]

- T. Aikawa, et al., A comparison of thoracolumbar intervertebral disc extrusion in French bulldogs and dachshunds and association with congenital vertebral anomalies. Vet. Surg. 43, 301–307 (2014). [CrossRef]

- M. C. C. M. Inglez de Souza, et al., Evaluation of the influence of kyphosis and scoliosis on intervertebral disc extrusion in French bulldogs. BMC Vet. Res. 14, 1–8 (2018). [CrossRef]

- N. Grapes, S. Bertram, R. Gonçalves, S. De Decker, Prevalence of discospondylitis and association with congenital vertebral body malformations in English and French bulldogs. J. Vet. Intern. Med. (2024). [CrossRef]

- K. Faller, et al., The effect of kyphoscoliosis on intervertebral disc degeneration in dogs. Vet. J. 200, 449–451 (2014). [CrossRef]

- E. Schlensker, O. Distl, Heritability of hemivertebrae in the French bulldog using an animal threshold model. Vet. J. 207, 188–189 (2016). [CrossRef]

- L. Roses, F. Yap, E. Welsh, Surgical management of screw-tail in dogs. Companion Anim. 23, 287–292 (2018). [CrossRef]

- P. Abrescia, et al., Caudectomy for resolution of tail folds intertrigo in brachycephalic dogs: about eleven cases. (2017). [CrossRef]

- M. Siniscalchi, S. d’Ingeo, M. Minunno, A. Quaranta, Communication in dogs. Animals (Basel) 8, 131 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Leaver, Reimchen, Behavioural responses of Canis familiaris to different tail lengths of a remotely-controlled life-size dog replica. Behaviour 145, 377–390 (2008). [CrossRef]

- N. H. C. Salmon Hillbertz, et al., Duplication of FGF3, FGF4, FGF19 and ORAOV1 causes hair ridge and predisposition to dermoid sinus in Ridgeback dogs. Nat. Genet. 39, 1318–1320 (2007). [CrossRef]

- X. Zhang, O. Distl, A study of Rhodesian Ridgeback dogs indicates that the duplication responsible for hair ridge is not identical with the hypothesized locus for dermoid sinus. Anim. Genet. 53 (2022). [CrossRef]

- C. H. Vite, In: Braund’s Clinical Neurology in Small Animals: Localization, Diagnosis and Treatment, CH Vite (Ed.).

- J. S. Gammie, Dermoid sinus removal in a Rhodesian Ridgeback dog. Can. Vet. J. 27, 250 (1986).

- N. J. Volstad, D. Tyrrell, J. Beck, Sacrocaudal dermoid sinus in three Rhodesian Ridgeback dogs. Aust. Vet. Pr. 46 (2016).

- V. Moritz, U. Ridgebacks, Rhodesian Ridgeback Health and Genetics A Breeders perspective.

- S. R. R. Sverige, Strategies for Health and Long-term Sustainable breeding. Available at: https://www.srrs.org/srrs/nyhetsarkiv/20231206-strategies-health-and-long-term-sustainable-breeding [Accessed 2024].

- C. Drögemüller, U. Philipp, B. Haase, A.-R. Günzel-Apel, T. Leeb, A noncoding melanophilin gene (MLPH) SNP at the splice donor of exon 1 represents a candidate causal mutation for coat color dilution in dogs. J. Hered. 98, 468–473 (2007). [CrossRef]

- D. J. Wiener, et al., Clinical and histological characterization of hair coat and glandular tissue of Chinese crested dogs. Vet. Dermatol. 24, 274–e62 (2013). [CrossRef]

- K. Kupczik, A. Cagan, S. Brauer, M. S. Fischer, The dental phenotype of hairless dogs with FOXI3 haploinsufficiency. Sci. Rep. 7, 5459 (2017). [CrossRef]

- L. Brancalion, B. Haase, C. M. Wade, Canine coat pigmentation genetics: a review. Anim. Genet. 53, 3–34 (2022). [CrossRef]

- G. M. Strain, Canine deafness. Vet. Clin. North Am. Small Anim. Pract. 42, 1209–1224 (2012). [CrossRef]

- M. F. Rothschild, P. S. Van Cleave, K. L. Glenn, L. P. Carlstrom, N. M. Ellinwood, Association of MITF with white spotting in Beagle crosses and Newfoundland dogs. Anim. Genet. 37 (2006). [CrossRef]

- S. Stritzel, A. Wöhlke, O. Distl, A role of the microphthalmia-associated transcription factor in congenital sensorineural deafness and eye pigmentation in Dalmatian dogs. J. Anim. Breed. Genet. 126, 59–62 (2009). [CrossRef]

- G. M. Strain, Deafness prevalence and pigmentation and gender associations in dog breeds at risk. Vet. J. 167, 23–32 (2004). [CrossRef]

- American Kennel Club, Official standard of the Dalmatian. Available at: https://images.akc.org/pdf/breeds/standards/Dalmatian.pdf [Accessed 2024].

- M. Reissmann, A. Ludwig, Pleiotropic effects of coat colour-associated mutations in humans, mice and other mammals (Elsevier, 2013). [CrossRef]

- T. Kawakami, et al., R-locus for roaned coat is associated with a tandem duplication in an intronic region of USH2A in dogs and also contributes to Dalmatian spotting. PLoS One 16, e0248233 (2021). [CrossRef]

- D. Bannasch, Mutations in the SLC2A9 gene cause hyperuricosuria and hyperuricemia in the dog. PLoS Genet. 4, 1–8 (2008). [CrossRef]

- Dalmatian Club of America, Dalmatians and Uric Acid HUA and LUA. Available at: https://dcaf.org/dalmatian-health/urinary-stones/lua-dalmatians/ [Accessed 2024].

- L. A. Clark, J. M. Wahl, C. A. Rees, K. E. Murphy, Retrotransposon insertion in SILV is responsible for merle patterning of the domestic dog. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103, 1376–1381 (2006). [CrossRef]

- B. C. Ballif, et al., The PMEL gene and merle in the domestic dog: A continuum of insertion lengths leads to a spectrum of coat color variations in Australian shepherds and related breeds. Cytogenet. Genome Res. 156, 22–34 (2018). [CrossRef]

- M. Langevin, H. Synkova, T. Jancuskova, S. Pekova, Merle phenotypes in dogs–SILV SINE insertions from Mc to Mh. PLoS One 13, e0198536 (2018). [CrossRef]

- I. Reetz, M. Stecker, W. Wegner, Audiometric findings in dachshunds (merle gene carriers). (1977).

- U. Philipp, et al., Polymorphisms within the canine MLPH gene are associated with dilute coat color in dogs. BMC Genet. 6, 1–15 (2005). [CrossRef]

- A. Bauer, A. Kehl, V. Jagannathan, T. Leeb, A novel MLPH variant in dogs with coat colour dilution. Anim. Genet. 49, 94–97 (2018). [CrossRef]

- S. L. Van Buren, et al., A third MLPH variant causing coat color dilution in dogs. Genes (Basel) 11, 639 (2020). [CrossRef]

- W. H. Miller Jr, Colour dilution alopecia in Doberman Pinschers with blue or fawn coat colours: a study on the incidence and histopathology of this disorder. Vet. Dermatol. 1, 113–122 (1990). [CrossRef]

- M. Welle, et al., MLPH genotype—melanin phenotype correlation in dilute dogs. J. Hered. 100, S75–S79 (2009). [CrossRef]

- S. M. Schmutz, T. G. Berryere, Genes affecting coat colour and pattern in domestic dogs: a review. Anim. Genet. 38, 539–549 (2007). [CrossRef]

- C. Laffort-Dassot, L. Beco, D. N. Carlotti, Follicular dysplasia in five Weimaraners. Vet. Dermatol. 13, 253–260 (2002). [CrossRef]

- F. O. Smith, The Issue of the Silver Labrador. Available at: https://thelabradorclub.com/the-issue-of-the-silver-labrador/.

- French Bull Dog Club of America, Interpretation of the French Bulldog Standard on Color. Available at: https://frenchbulldogclub.org/color/ [Accessed 2024].

- L. Asher, G. Diesel, J. F. Summers, P. D. McGreevy, L. M. Collins, Inherited defects in pedigree dogs. Part 1: Disorders related to breed standards. The Veterinary Journal 182, 402–411 (2009). [CrossRef]

- G. Lehner, C. S. Louis, R. S. Mueller, Reproducibility of ear cytology in dogs with otitis externa. Vet. Rec. 167, 23–26 (2010). [CrossRef]

- D. G. O’Neill, et al., Frequency and predisposing factors for canine otitis externa in the UK–a primary veterinary care epidemiological view. Canine Med. Genet. 8, 1–16 (2021). [CrossRef]

- M.-D. Crapon De Caprona, P. Savolainen, Extensive Phenotypic Diversity among South Chinese Dogs. ISRN Evol. Biol. 2013, 1–8 (2013). [CrossRef]

- A. T. Vanak, M. E. Gompper, Interference competition at the landscape level: the effect of free-ranging dogs on a native mesocarnivore. J. Appl. Ecol. 47, 1225–1232 (2010). [CrossRef]

- E. Ruiz-Izaguirre, et al., Roaming characteristics and feeding practices of village dogs scavenging sea-turtle nests. Anim. Conserv. 18, 146–156 (2015). [CrossRef]

- D. Krauze-Gryz, J. Gryz, Free-Ranging Domestic Dogs ( Canis familiaris ) in Central Poland: Density, Penetration Range and Diet Composition. Pol. J. Ecol. 62, 183–193 (2014). [CrossRef]

- L. Vychodilova, et al., Genetic diversity and population structure of African village dogs based on microsatellite and immunity-related molecular markers. PLoS One 13, e0199506 (2018). [CrossRef]

- G. Leroy, S.-Z. Wang, T. Lewis, S. Licari, Ancient and Recent Changes in Breeding Practices for Dogs. Dogs, Past and Present 24 (2023).

- American Kennel Club, Most Popular Dog Breeds. (2024). Available at: https://www.akc.org/most-popular-breeds/ [Accessed 20 January 2025].

- D. G. O’Neill, et al., French Bulldogs differ to other dogs in the UK in propensity for many common disorders: a VetCompass study. Canine Med. Genet. 8, 1–14 (2021). [CrossRef]

- L. R. McAuliffe, C. S. Koch, J. Serpell, K. L. Campbell, Associations between atopic dermatitis and anxiety, aggression, and fear-based behaviors in dogs. J. Am. Anim. Hosp. Assoc. 58, 161–167 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Brachycephalic Working Group, Brachycephalic Working Group. Available at: https://www.ukbwg.org.uk/ [Accessed 20 January 2025].

- F. W. Nicholas, Response to the documentary pedigree dogs exposed: three reports and their recommendations. [Preprint] (2011).

- E. Morel, L. Malineau, C. Venet, V. Gaillard, F. Péron, Prioritization of Appearance over Health and Temperament Is Detrimental to the Welfare of Purebred Dogs and Cats. Animals (Basel) 14, 1003 (2024). [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author[s] and contributor[s] and not of MDPI and/or the editor[s]. MDPI and/or the editor[s] disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).