Submitted:

11 June 2025

Posted:

11 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

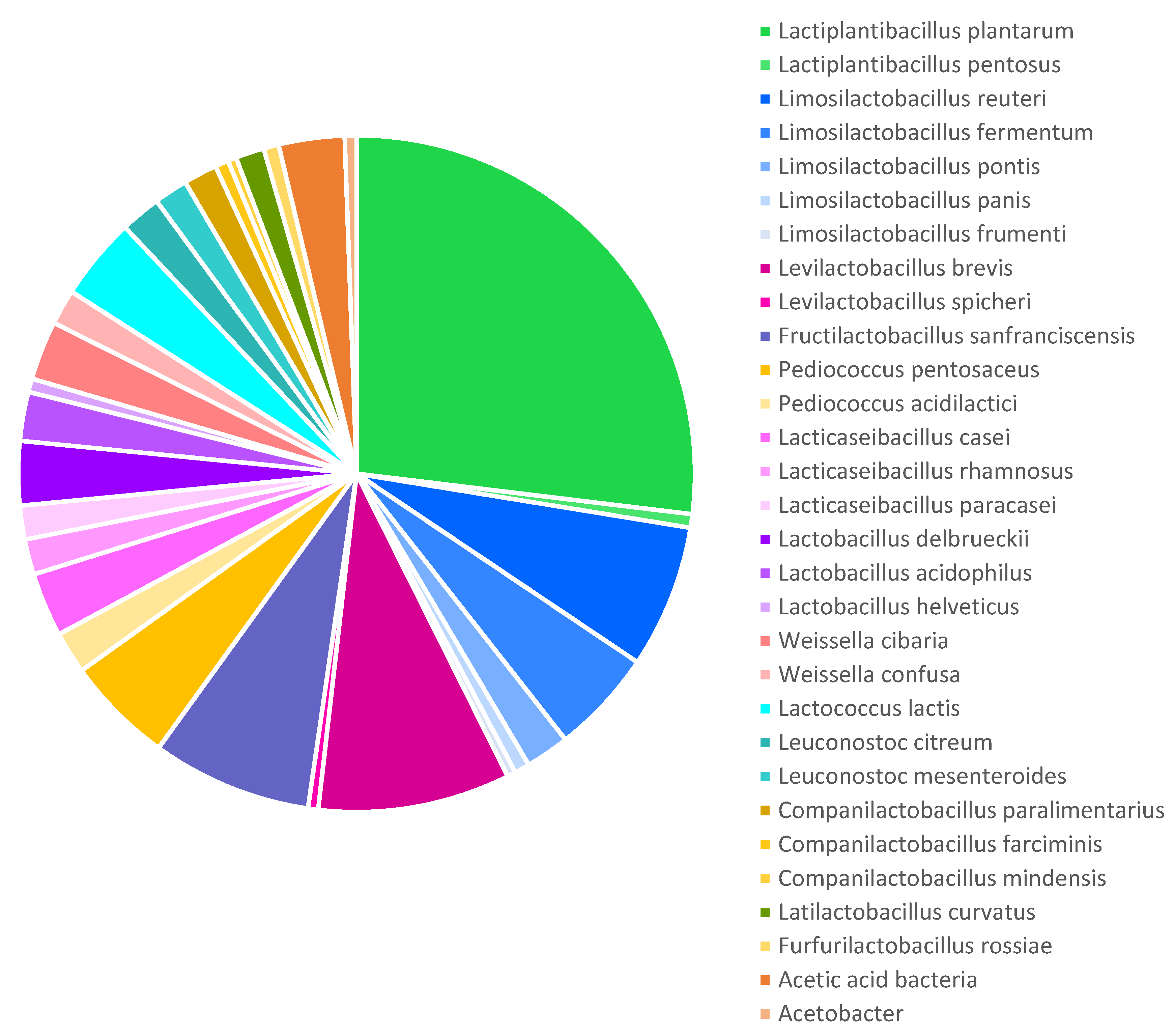

2. Sourdough Microbiota

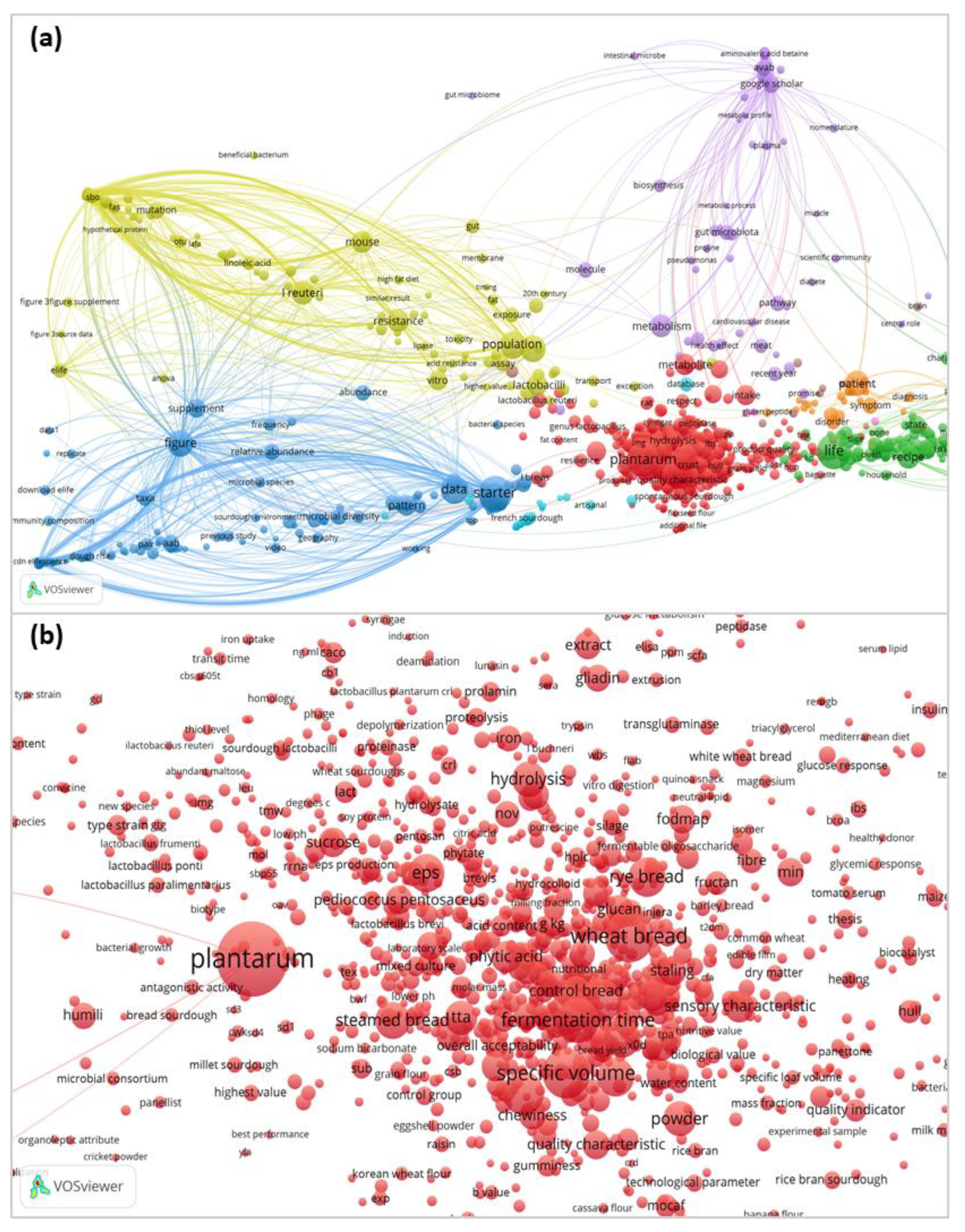

2.1. Mapping Terms Among Sourdough-Related Documents

2.2. Types of Sourdoughs

2.2.1. Type I Sourdough

2.2.2. Type II Sourdough

2.2.3. Type III Sourdough

2.2.4. Type IV Sourdough

3. The Effect of Sourdough LAB on the Shelf Life of Bread

3.1. Antifungal Compounds

3.1.1. Organic Acids

3.1.2. Other Compounds

3.1.3. Mycotoxin Removal

3.2. Antibacterial Activity

4. Contribution of Other Microorganisms to Protecting Bread from Spoilage

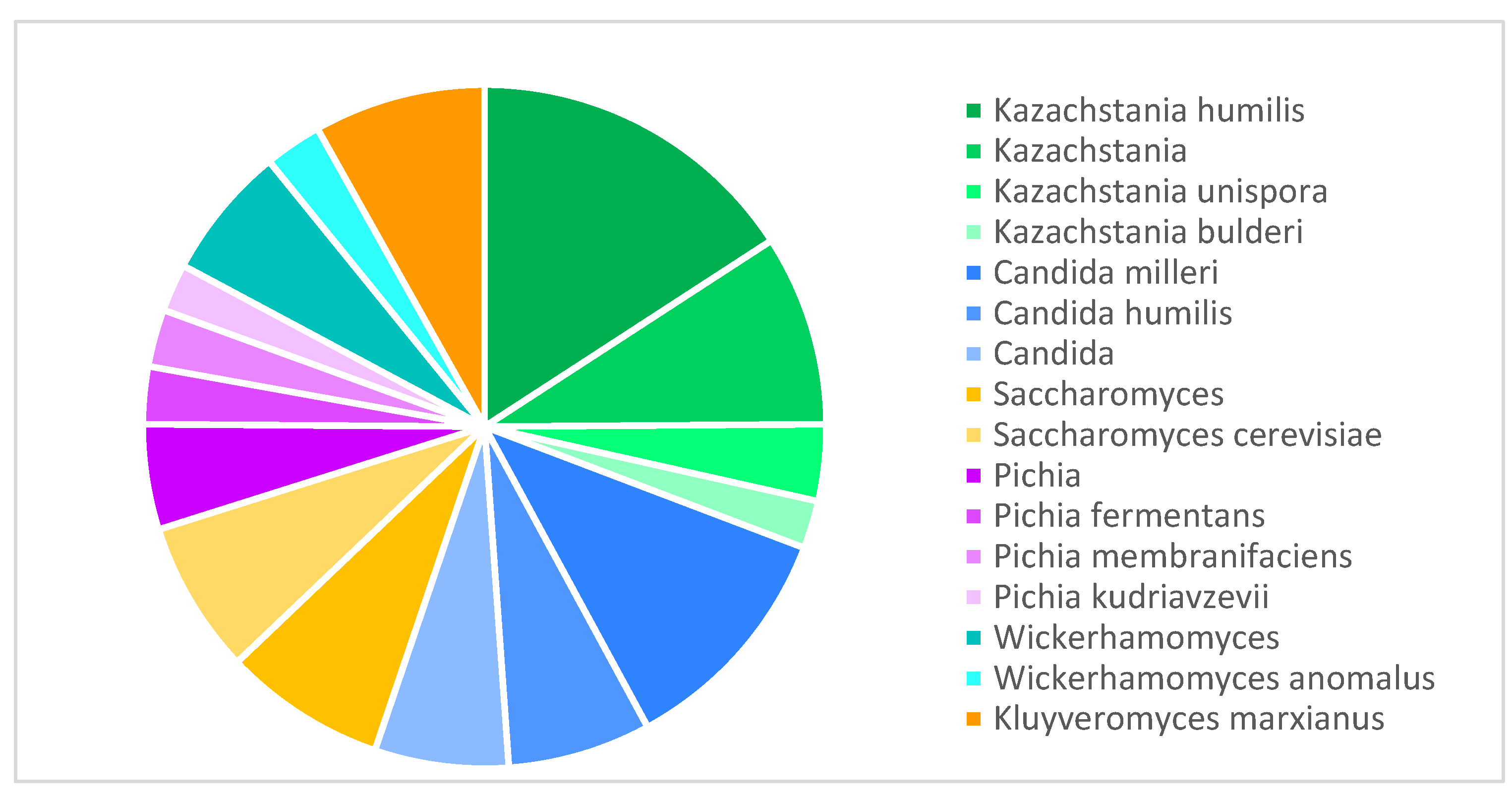

4.1. Yeast

4.2. Acetic Acid Bacteria

5. New Strategies for Using Bread Sourdoughs

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- The Federation of Bakers. European Bread Market. Available online: https://www.fob.uk.com/about-the-bread-industry/industry-facts/european-bread-market/ (accessed on 28 June 2025).

- Axel, C.; Zannini, E.; Arendt, E.K. Mold spoilage of bread and its biopreservation: A review of current strategies for bread shelf life extension. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2017, 57(16), 3528–3542. [CrossRef]

- Nasrollahzadeh, A.; Mokhtari, S.; Khomeiri, M.; Saris, P.E.J. Antifungal Preservation of Food by Lactic Acid Bacteria. Foods 2022, 11, 395. [CrossRef]

- Garcia, M.V.; Bernardi, A.O.; Parussolo, G.; Stefanello, A.; Lemos, J.G., Copetti, M.V. Spoilage fungi in a bread factory in Brazil: Diversity and incidence through the bread-making process. Food Res. Int. 2019a, 126, 108593. [CrossRef]

- Garcia, M.V.; Bernardi, A.O.; Copetti, M.V. The fungal problem in bread production: Insights of causes, consequences, and control methods. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2019b, 29, 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Awulachew, M.T. Bread deterioration and a way to use healthful methods. CyTA J. Food, 2024, 22(1): 2424848. [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Figueroa, R.H.; Mani-López, E.; Palou, E.; López-Malo, A. Sourdoughs as Natural Enhancers of Bread Quality and Shelf Life: A Review. Fermentation 2024a, 10, 7. [CrossRef]

- Lemos, J.G.; Silva, L.P.; Mahfouz, M.A.A.R.; Cazzuni, L.A.F.; Rocha, L.O.; Steel, C.J. Use of dielectric-barrier discharge (DBD) cold plasma for control of bread spoilage fungi. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2025, 430, 111034. [CrossRef]

- Illueca, F.; Moreno, A.; Calpe, J.; Nazareth, T.d.M.; Dopazo, V.; Meca, G.; Quiles, J.M.; Luz, C. Bread biopreservation through the addition of lactic acid bacteria in sourdough. Foods 2023, 12, 864. [CrossRef]

- Pacher, N.; Burtscher, J.; Johler, S.; Etter, D.; Bender, D.; Fieseler, L.; Domig, K.J. Ropiness in Bread—A Re-Emerging Spoilage Phenomenon. Foods 2022, 11, 3021. [CrossRef]

- EFSA. Scientific Opinion on the maintenance of the list of QPS biological agents intentionally added to food and feed (2012 update). EFSA J. 2012, 10:3020. [CrossRef]

- Zheng J.; Wittouck S.; Salvetti E.; Franz C.M.A.P.; Harris H.M.B.; Mattarelli P.; O’Toole, P.W.; Pot B.; Vandamme P.; Walter, J.; Watanabe, K.; Wuyts, S.; Felis, G.E.; Gänzle, M.G.; Lebeer, S. A taxonomic note on the genus Lactobacillus: description of 23 novel genera, emendeddescription of the genus Lactobacillus Beijerinck 1901, and union of Lactobacillaceae and Leuconostocaceae. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2020, 70, 2782–2858. [CrossRef]

- Lau, S.W.; Chong, A.Q.; Chin, N.L.; Talib, R.A.; Basha, R.K. Sourdough Microbiome Comparison and Benefits. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 1355. [CrossRef]

- De Vero, L.; Iosca, G.; Gullo, M.; Pulvirenti, A. Functional and Healthy Features of Conventional and Non-Conventional Sourdoughs. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 3694. [CrossRef]

- De Bondt, Y.; Verdonck, C.; Brandt, M.J.; De Vuyst, L.; Gänzle, M.G.; Gobbetti, M.; Zannini, E.; Courtin, C.M. Wheat sourdough breadmaking: a scoping review. Ann. Rev. Food Sci. Technol. 2024, 15: 265–282. [CrossRef]

- De Angelis, M.; Minervini, F.; Siragusa, S.; Rizzello, C.G.; Gobbetti, M. Wholemeal wheat flours drive the microbiome and functional features of wheat sourdoughs. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2019, 302, 35–46. [CrossRef]

- Boreczek, J.; Litwinek, D.; Żylińska-Urban, J.; Izak, D.; Buksa, K.; Gawor, J.; Gromadka, R.; Bardowski, J.K.; Kowalczyk, M. Bacterial community dynamics in spontaneous sourdoughs made from wheat, spelt, and rye wholemeal flour. MicrobiologyOpen, 2020, 9(4), e1009. [CrossRef]

- Oshiro, M.; Tanaka, M.; Zendo, T.; Nakayama, J. Impact of pH on succession of sourdough lactic acid bacteria communities and their fermentation properties. Biosci. Microbiota Food Health, 2020, 39(3), 152–159. [CrossRef]

- Suo, B., Chen, X., Wang, Y. Recent research advances of lactic acid bacteria in sourdough: origin, diversity, and function. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2021, 37, 66–75. [CrossRef]

- Khlestkin, V.K.; Lockachuk, M.N.; Savkina, O.A.; Kuznetsova, L.I.; Pavlovskaya, E.N.; Parakhina, O.I. Taxonomic structure of bacterial communities in sourdoughs of spontaneous fermentation. Vavilov J. Genetics Breeding, 2022, 26(4), 385. [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.H.; Jung, J.Y.; Jeon, C.O. Source tracking and succession of kimchi lactic acid bacteria during fermentation. J. Food Sci. 2015, 80(8), M1871–M1877. [CrossRef]

- Romi, W.; Ahmed, G.; Jeyaram, K. Three-phase succession of autochthonous lactic acid bacteria to reach a stable ecosystem within 7 days of natural bamboo shoot fermentation as revealed by different molecular approaches. Mol. Ecol. 2015, 24(13), 3372–3389. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, C.; Liu, F.; Jin, Z.; Xia, X. Ecological succession and functional characteristics of lactic acid bacteria in traditional fermented foods. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2023, 63(22), 5841–5855. [CrossRef]

- Baev, V.; Apostolova, E.; Gotcheva, V.; Koprinarova, M.; Papageorgiou, M.; Rocha, J.M.; Yahubyan, G.; Angelov, A. 16S-rRNA-Based Metagenomic Profiling of the Bacterial Communities in Traditional Bulgarian Sourdoughs. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 803. [CrossRef]

- Debonne, E.; Van Schoors, F.; Maene, P.; Van Bockstaele, F.; Vermeir, P.; Verwaeren, J.; Eeckhout, M.; Devlieghere, F. Comparison of the antifungal effect of undissociated lactic and acetic acid in sourdough bread and in chemically acidified wheat bread. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2020a, 321, 108551. [CrossRef]

- Weckx, S.; Van der Meulen, R.; Maes, D.; Scheirlinck, I.; Huys, G.; Vandamme, P.; De Vuyst, L. Lactic acid bacteria community dynamics and metabolite production of rye sourdough fermentations share characteristics of wheat and spelt sourdough fermentations. Food Microbiol. 2010, 27(8), 1000–1008. [CrossRef]

- Sanmartín, G.; Sánchez-Adriá, I.E.; Prieto, J.A.; Estruch, F.; Randez-Gil, F. Bioprospecting of sourdough microbial species from artisan bakeries in the city of Valencia. Food Microbiol. 2024, 120, 104474. [CrossRef]

- Minervini F.; Lattanzi A.; De Angelis M.; Di Cagno R.; Gobbetti M. Influence of artisan bakery- or laboratory-propagated sourdoughs on the diversity of lactic acid bacterium and yeast microbiotas. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2012, 78(15), 5328–5340. [CrossRef]

- Landis E.A.; Oliverio A.M.; McKenney E.A.; Nichols L.M.; Kfoury N.; Biango-Daniels M.; Shell L.K.; Madden A.A.; Shapiro L.; Sakunala S.; Drake K.; Robbat A.; Booker M.; Dunn R.R.; Fierer N.; Wolfe B.E. The diversity and function of sourdough starter microbiomes. eLife 2021, 10, e61644. [CrossRef]

- Leathers, T.D.; Bischoff, K.M. Biofilm formation by strains of Leuconostoc citreum and L. mesenteroides. Biotechnol. Lett. 2011, 33, 517–523. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Wang, Y.; An, Q., Sa, R.; Zhang, D.; Xu, R. Research on the role of LuxS/AI-2 quorum sensing in biofilm of Leuconostoc citreum 37 based on complete genome sequencing. 3 Biotech, 2021, 11, 189. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Gong, X.; Song, J.; Peng, Y.; Zeng, Y.; Chen, J.; Wang, Z.; Li, Z.; Zhu, Y. A novel bio-based film-forming helper derived from Leuconostoc mesenteroides: A promising alternative to chemicals for the preparation of biomass film. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 493, 152436. [CrossRef]

- Minervini, F.; Celano, G.; Lattanzi, A.; Tedone, L.; De Mastro, G.; Gobbetti, M.; De Angelis, M. Lactic Acid Bacteria in Durum Wheat Flour Are Endophytic Components of the Plant during Its Entire Life Cycle. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2015, 81(19), 6736–6748. [CrossRef]

- Gänzle M.G.; Zheng J. Lifestyles of sourdough lactobacilli – Do they matter for microbial ecology and bread quality? Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2019, 302, 15–23. [CrossRef]

- Vogel, R.F.; Pavlovic, M.; Ehrmann, M.; Wiezer, A.; Liesegang, H.; Offschanka, S.; Voget, S.; Angelov, A.; Böcker, G.; Liebl, W. Genomic analysis reveals Lactobacillus sanfranciscensis as stable element in traditional sourdoughs. Microb. Cell. Fact. 2011, 10(Suppl 1), S6. [CrossRef]

- Boiocchi, F.; Porcellato, D.; Limonta, L.; Picozzi, C.; Vigentini, I.; Locatelli, D. P.; Foschino, R. Insect frass in stored cereal products as a potential source of Lactobacillus sanfranciscensis for sourdough ecosystem. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2017, 123(4), 944–955. [CrossRef]

- Comasio, A.; Verce, M.; Van Kerrebroeck, S.; De Vuyst, L. Diverse Microbial Composition of Sourdoughs from Different Origins. Front Microbiol. 2020a, 11, 1212. [CrossRef]

- Xing, X.; Ma, J.; Fu, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Ai, Z.; Suo, B. Diversity of bacterial communities in traditional sourdough derived from three terrain conditions (mountain, plain and basin) in Henan Province, China. Food Res. Int. 2020, 133, 109139. [CrossRef]

- Han, D.; Yang, Y.; Guo, Z.; Dai, S.; Jiang, M.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Yu, Z.; Wang, K.; Rong, C.; et al. A Review on the Interaction of Acetic Acid Bacteria and Microbes in Food Fermentation: A Microbial Ecology Perspective. Foods 2024, 13, 2534. [CrossRef]

- Costa, L.F.; Kothe, C.I.; Grassotti, T.T.; Garske, R.P.; Sandoval, B.N.; Varela, A.P.M.; Prichula. J.; Frazzon, J.; Mann, M.B.; Thys, R.C.S.; Frazzon, A.P.G. Evolution of the spontaneous sourdoughs microbiota prepared with organic or conventional whole wheat flours from South Brazil. Anais da Academia Brasileira de Ciências, 2022, 94(suppl 4), e20220091. [CrossRef]

- Rappaport, H.B.; Senewiratne, N.P.; Lucas, S.K.; Wolfe, B.E.; Oliverio, A.M. Genomics and synthetic community experiments uncover the key metabolic roles of acetic acid bacteria in sourdough starter microbiomes. Msystems, 2024, 9(10), e00537-24. [CrossRef]

- Semumu, T.; Zhou, N.; Kebaneilwe, L.; Loeto, D.; Ndlovu, T. Exploring the Microbial Diversity of Botswana’s Traditional Sourdoughs. Fermentation, 2024, 10(8), 417. 10.3390/fermentation10080417.

- Arora, K.; Ameur, H.; Polo, A.; Di Cagno, R.; Rizzello, C.G.; Gobbetti, M. Thirty years of knowledge on sourdough fermentation: A systematic review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 108, 71–83. [CrossRef]

- Canesin, M.R.; Betim Cazarin, C.B. Nutritional quality and nutrient bioaccessibility in sourdough bread. Curr. Opin. Food Sci., 2021, 40, 81–86. [CrossRef]

- Pétel, C.; Onno, B.; Prost, C. Sourdough volatile compounds and their contribution to bread: A review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 59. 105–123. [CrossRef]

- Warburton, A.; Silcock, P.; Eyres, G.T. Impact of sourdough culture on the volatile compounds in wholemeal sourdough bread. Food Res. Int. 2022, 161, 111885. [CrossRef]

- Axel, C.; Brosnan, B.; Zannini, E.; Peyer, L.; Furey, A.; Coffey, A.; Arendt, E. Antifungal activities of three different Lactobacillus species and their production of antifungal carboxylic acids in wheat sourdough. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2016, 100, 1701–1711. [CrossRef]

- Comasio, A.; Van Kerrebroeck, S.; Harth, H.; Verté, F.; De Vuyst, L. Potential of Bacteria from Alternative Fermented Foods as Starter Cultures for the Production of Wheat Sourdoughs. Microorganisms 2020b, 8, 1534. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Brandt, M.J.; Schwab, C.; Gänzle, M.G. Propionic acid production by cofermentation of Lactobacillus buchneri and Lactobacillus diolivorans in sourdough. Food Microbiol. 2010, 27(3), 390–395. [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Li, X.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, W.; Ma, G.; Ma, N.; Hu, Q.; Pei, F. A novel lactic acid bacterium for improving the quality and shelf life of whole wheat bread. Food Control 2020, 109, 106914. [CrossRef]

- Muhialdin, B.J.; Hassan, Z.; Sadon, S.K. Antifungal Activity of Lactobacillus fermentum Te007, Pediococcus pentosaceus Te010, Lactobacillus pentosus G004, and L. paracasi D5 on Selected Foods. J. Food Sci. 2011, 76(7), M493–M499. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Hao, X.; Yang, F.; Wang, Y.; Fan, X.; Wang, Y. Antifungal Activity of Lactobacillus plantarum ZZUA493 and Its Application to Extend the Shelf Life of Chinese Steamed Buns. Foods 2022, 11, 195. [CrossRef]

- Plessas, S.; Mantzourani, I.; Bekatorou, A. Evaluation of Pediococcus pentosaceus SP2 as Starter Culture on Sourdough Bread Making. Foods 2020, 9, 77. [CrossRef]

- Kazakos, S.; Mantzourani, I.; Plessas, S. Quality Characteristics of Novel Sourdough Breads Made with Functional Lacticaseibacillus paracasei SP5 and Prebiotic Food Matrices. Foods 2022, 11, 3226. [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Fu, J.; Hu, S.; Li, Z.; Qu, J.; Wu, Z.; Chen, S. Comparison of the effects of acetic acid bacteria and lactic acid bacteria on the microbial diversity of and the functional pathways in dough as revealed by high-throughput metagenomics sequencing. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2021, 346, 109168. [CrossRef]

- Li H.; Hu S.; Fu J. Effects of acetic acid bacteria in starter culture on the properties of sourdough and steamed bread. Grain Oil Sci. Technol. 2022, 5, 13–21. [CrossRef]

- Chang J.M.; Fang T.J. Survival of Escherichia coli O157:H7 and Salmonella enterica serovars Typhimurium in iceberg lettuce and the antimicrobial effect of rice vinegar against E. coli O157:H7. Food Microbiol. 2007, 24(7-8), 745–751. [CrossRef]

- Ezz Eldin H.M.; Sarhan R.M.; Khayyal A.E. The impact of vinegar on pathogenic Acanthamoeba astronyxis isolate. J. Parasit. Dis. 2019, 43(3), 351–359. [CrossRef]

- Aitzhanova, A.; Oleinikova, Y.; Mounier, J.; Hymery, N.; Leyva Salas, M.; Amangeldi, A.; Saubenova, M.; Alimzhanova, M.; Ashimuly, K.; Sadanov, A. Dairy associations for the targeted control of opportunistic Candida. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2021, 37, 143. [CrossRef]

- Oleinikova, Y.; Alybayeva, A.; Daugaliyeva, S.; Alimzhanova, M.; Ashimuly, K.; Yermekbay, Zh.; Khadzhibayeva, I.; Saubenova, M. Development of an antagonistic active beverage based on a starter including Acetobacter and assessment of its volatile profile. Int. Dairy J. 2024a, 148, 105789. [CrossRef]

- Oleinikova, Y., Daugaliyeva, S., Mounier, J., Saubenova M., Aitzhanova A. Metagenetic analysis of the bacterial diversity of Kazakh koumiss and assessment of its anti-Candida albicans activity. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2024b, 40, 99. [CrossRef]

- Taheur, F.B.; Fedhila, K.; Chaieb, K.; Kouidhi, B.; Bakhrouf, A.; Abrunhosa, L. Adsorption of aflatoxin B1, zearalenone and ochratoxin A by microorganisms isolated from Kefir grains. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2017, 251, 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Adebiyi, J.A.; Kayitesi, E.; Adebo, O.A.; Changwa, R.; Njobeh, P.B. Food fermentation and mycotoxin detoxification: An African perspective. Food Control 2019, 106, 106731. [CrossRef]

- Afshar, P.; Shokrzadeh, M.; Raeis, S.N.; Saraei, A.G-H.; Nasiraii, L.R. Aflatoxins biodetoxification strategies based on probiotic bacteria. Toxicon 2020, 178, 50–58. [CrossRef]

- Lafuente, C.; Calpe, J.; Musto, L.; Nazareth, T.d.M.; Dopazo, V.; Meca, G.; Luz, C. Preparation of Sourdoughs Fermented with Isolated Lactic Acid Bacteria and Characterization of Their Antifungal Properties. Foods 2023, 12, 686. [CrossRef]

- Lafuente, C.; de Melo Nazareth, T.; Dopazo, V.; Meca, G.; Luz, C. Enhancing Bread Quality and Extending Shelf Life Using Dried Sourdough. LWT, 2024, 116379. [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, L.B.; Campos, J.Z.; Kothe, C.I.; Welke, J.E.; Rodrigues, E.; Frazzon, J.; Thys, R.C.S. Type III sourdough: Evaluation of biopreservative potential in bakery products with enhanced antifungal activity. Food Res. Int. 2024, 189, 114482. [CrossRef]

- Calasso, M.; Marzano, M.; Caponio, G.R.; Celano, G.; Fosso, B.; Calabrese, F.M.; De Palma. D.; Vacca. M.; Notario, E.; Pesole, G.; De Angelis, M.; De Leo, F. Shelf-life extension of leavened bakery products by using bio-protective cultures and type-III sourdough. LWT, 2023, 177, 114587. [CrossRef]

- Siepmann, F.B.; Ripari, V.; Waszczynskyj, N.; Spier, M.R. Overview of sourdough technology: From production to marketing. Food Bioproc. Tech. 2018, 11, 242–270. [CrossRef]

- Fekri, A.; Abedinzadeh, S.; Torbati, M.; Azadmard-Damirchi, S.; Savage, G.P. Considering sourdough from a biochemical, organoleptic, and nutritional perspective. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2024, 125, 105853. [CrossRef]

- Mūrniece, R.; Kļava, D. Impact of Long-Fermented Sourdough on the Technological and Prebiotical Properties of Rye Bread. Proc.Latv. Acad. Sci. 2022, 76(1), 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Syrokou, M.K.; Tziompra, S.; Psychogiou, E.-E.; Mpisti, S.-D.; Paramithiotis, S.; Bosnea, L.; Mataragas, M.; Skandamis, P.N.; Drosinos, E.H. Technological and Safety Attributes of Lactic Acid Bacteria and Yeasts Isolated from Spontaneously Fermented Greek Wheat Sourdoughs. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 671. [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Figueroa, R.H.; Mani-López, E.; López-Malo, A. Antifungal activity of wheat-flour sourdough (Type II) from two different Lactobacillus in vitro and bread. Appl. Food Res. 2023, 3(2), 100319. [CrossRef]

- Garcia, M.V.; Stefanello, R.F.; Pia, A.K.; Lemos, J.G.; Nabeshima, E.H.; Bartkiene, E.; Rocha, J.M.; Copetti, M.V.; Sant'Ana, A.S. Influence of Limosilactobacillus fermentum IAL 4541 and Wickerhamomyces anomalus IAL 4533 on the growth of spoilage fungi in bakery products. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2024, 413, 110590. [CrossRef]

- Sani A.R.; Hamza, T. M.; Legbo I.M.; Jubril F.I.; Ibrahim A.; Mohammed, A.; Buru, A.S. Isolation and Identification of Fungi spp Associated with Bread Spoilage in Lapai, Niger State. Nigerian Health J. 2025, 25(1), 365–370. [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Liu, Y.; Guo, Z.; Ji, N.; Sun, Q.; Liu, T.; Li, Y. Antifungal activities of Pediococcus pentosaceus LWQ1 and Lactiplantibacillus plantarum LWQ17 isolated from sourdough and their efficacies on preventing spoilage of Chinese steamed bread. Food Control, 2025, 168, 110940. [CrossRef]

- Garofalo, C.; Zannini, E.; Aquilanti, L.; Silvestri, G.; Fierro, O.; Picariello, G.; Clementi, F. Selection of Sourdough Lactobacilli with Antifungal Activity for Use as Biopreservatives in Bakery Products. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2012, 60(31), 7719–7728. [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Figueroa, R.H.; Mani-López, E.; Ramírez-Corona, N.; López-Malo, A. Optimizing Lactic Acid Bacteria Proportions in Sourdough to Enhance Antifungal Activity and Quality of Partially and Fully Baked Bread. Foods 2024b, 13, 2318. [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Figueroa, R.H.; Mani-López, E.; Ramírez-Corona, N.; López-Malo, A. Optimizing Lactic Acid Bacteria Proportions in Sourdough to Enhance Antifungal Activity and Quality of Partially and Fully Baked Bread. Foods 2024c-f, 13, 2318. [CrossRef]

- Mou, T.; Xu, R.; Li, Q.; Li, J.; Liu, S.; Ao, X.; Chen, S.; Liu, A. Screening of Antifungal Lactic Acid Bacteria and Their Impact on the Quality and Shelf Life of Rye Bran Sourdough Bread. Foods 2025, 14, 1253. [CrossRef]

- Arsoy, E.S.; Gül, L.B.; Çon, A.H. Characterization and selection of potential antifungal lactic acid bacteria isolated from Turkish spontaneous sourdough. Curr. Microbiol. 2022, 79(5), 148. [CrossRef]

- Jin, J.; Nguyen, T.T.H.; Humayun, S.; Park, S.; Oh, H.; Lim, S.; Mk, I.K.; Li, Y.; Pal, K.; Kim, D. Characteristics of sourdough bread fermented with Pediococcus pentosaceus and Saccharomyces cerevisiae and its bio-preservative effect against Aspergillus flavus. Food Chem. 2021, 345, 128787. [CrossRef]

- Ma, M.; Li, A.; Feng, J.; Wang, Z.; Jia, Y.; Ma, X.; Ning, Y. Antifungal mechanism of Lactiplantibacillus plantarum P10 against Aspergillus niger and its in-situ biopreservative application in Chinese steamed bread. Food Chem. 2024, 449, 139181. [CrossRef]

- Stefanello, R.F.; Vilela, L.F.; Margalho, L.P.; Nabeshima, E.H.; Matiolli, C.C.; da Silva, D.T.; Schwan, R.F.; Emanuelli T.; Noronha, M.F.; Cabral, L.; Sant’Ana, A.S.; Copetti, M.V. Dynamics of microbial ecology and their bio-preservative compounds formed during the panettones elaboration using sourdough-isolated strains as starter cultures. Food Biosci. 2024, 60, 104279. [CrossRef]

- Mota-Gutierrez, J.; Franciosa, I.; Ruggirello, M.; Dolci, P. Technological, functional and safety properties of lactobacilli isolates from soft wheat sourdough and their potential use as antimould cultures. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2021, 37(9), 146. [CrossRef]

- EL Boujamaai, M.; Mannani, N.; Aloui, A.; Errachidi, F.; Salah-Abbès, J.B.; Riba, A.; Abbès, S.; Rocha, J.M.; Bartkiene, E.; Brabet, C.; Zinedine, A. Biodiversity and biotechnological properties of lactic acid bacteria isolated from traditional Moroccan sourdoughs. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2023, 39, 331 . [CrossRef]

- Stiles, J.; Penkar, S.; Plocková, M.; Chumchalová, J.; Bullerman, L.B. Antifungal activity of sodium acetate and Lactobacillus rhamnosus. J. Food Prot. 2002, 65(7), 1188e1191. [CrossRef]

- Le Lay, C.; Mounier, J.; Vasseur, V.; Weill, A.; Le Blay, G.; Barbier, G.; Coton E. In vitro and in situ screening of lactic acid bacteria and propionibacteria antifungal activities against bakery product spoilage molds. Food Control 2016, 60, 247–255. [CrossRef]

- Fraberger, V.; Ammer, C.; Domig, K.J. Functional Properties and Sustainability Improvement of Sourdough Bread by Lactic Acid Bacteria. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 1895. [CrossRef]

- Kennepohl, D.; Farmer, S.; Reusch, W.; Neils, T. Acidity of carboxylic acids. In Organic Chemistry. LibreTextsTM Chemistry. 1118–1121. Available online: https://chem.libretexts.org/Bookshelves/Organic_Chemistry/Supplemental_Modules_(Organic_Chemistry)/Carboxylic_Acids/Properties_of_Carboxylic_Acids/Physical_Properties_of_Carboxylic_Acids/Acidity_of_Carboxylic_Acids (accessed on 16 May 2025).

- Williams, R. pKa Values. Available online: https://chem.libretexts.org/@go/page/169800 (accessed on 16 May 2025).

- Bartkiene, E.; Lele, V.; Ruzauskas, M.; Domig, K.J.; Starkute, V.; Zavistanaviciute, P.; Bartkevics, V.; Pugajeva, I.; Klupsaite, D.; Juodeikiene, G.; et al. Lactic Acid Bacteria Isolation from Spontaneous Sourdough and Their Characterization Including Antimicrobial and Antifungal Properties Evaluation. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 64. [CrossRef]

- Debonne, E.; Maene, P.; Vermeulen, A.; Van Bockstaele, F.; Depredomme, L.; Vermeir, P.; Eeckhout, M.; Devlieghere, F. Validation of in-vitro antifungal activity of the fermentation quotient on bread spoilage moulds through growth/no-growth modelling and bread baking trials. LWT, 2020b, 117, 108636. [CrossRef]

- Debonne, E.; Vermeulen, A.; Bouboutiefski, N.; Ruyssen, T.; Van Bockstaele, F.; Eeckhout, M.; Devlieghere, F. Modelling and validation of the antifungal activity of DL-3-phenyllactic acid and acetic acid on bread spoilage moulds. Food Microbiol. 2020c, 88, 103407. [CrossRef]

- Ström, K.; Sjögren, J.; Broberg, A.; Schnürer, J. Lactobacillus plantarum MiLAB 393 Produces the Antifungal Cyclic Dipeptides Cyclo(L-Phe-L-Pro) and Cyclo(L-Phe-trans-4-OH-L-Pro) and 3-Phenyllactic Acid. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2002, 68(9), 4322–4327. [CrossRef]

- Lavermicocca, P.; Valerio, F.; Evidente, A.; Lazzaroni, S.; Corsetti, A.; Gobbetti, M. Purification and Characterization of Novel Antifungal Compounds from the Sourdough Lactobacillus plantarum Strain 21B. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2000, 66(9), 4084–4090. [CrossRef]

- Rizzello, C.G.; Cassone, A.; Coda, R.; Gobbetti, M. Antifungal activity of sourdough fermented wheat germ used as an ingredient for bread making. Food Chem. 2011, 127:952–959. [CrossRef]

- Dagnas, S.; Gauvry, E.; Onno, B.; Membré, J.M. Quantifying effect of lactic, acetic, and propionic acids on growth of molds isolated from spoilesd bakery products. J. Food Prot. 2015, 78(9), 1689–1698. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Brandt, M.J.; Schwab, C.; Gänzle, M.G. Propionic acid production by cofermentation of Lactobacillus buchneri and Lactobacillus diolivorans in sourdough. Food Microbiol. 2010, 27(3): 390–395. [CrossRef]

- Axel, C.; Zannini, E.; Arendt, E.K.; Waters, D.M.; Czerny, M. Quantification of cyclic dipeptides from cultures of Lactobacillus brevis R2D by HRGC/MS using stable isotope dilution assay. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2014, 406, 2433–2444. [CrossRef]

- Luz, C.; D’Opazo, V.; Mañes, J.; Meca, G. Antifungal activity and shelf life extension of loaf bread produced with sourdough fermented by Lactobacillus strains. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2019, 43, e14126. [CrossRef]

- Houssni, I.E.; Khedid, K.; Zahidi, A.; Hassikou, R. The inhibitory effects of lactic acid bacteria isolated from sourdough on the mycotoxigenic fungi growth and mycotoxins from wheat bread. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2023, 50, 102702. [CrossRef]

- Corsetti, A.; Gobbetti, M.; Rossi, J.; Damiani, P. Antimould activity of sourdough lactic acid bacteria: identification of a mixture of organic acids produced by Lactobacillus sanfrancisco CB1. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 1998, 50(2), 253–256. [CrossRef]

- Sadeghi, A.; Ebrahimi, M.; Mortazavi, S.A.; Abedfar, A. Application of the selected antifungal LAB isolate as a protective starter culture in pan whole-wheat sourdough bread. Food Control 2018, 95, 298–307. [CrossRef]

- Ryan, L.A.M.; Zannini, E.; Dal Bello, F.; Pawlowska, A.; Koehler, P.; Arendt, E.K. Lactobacillus amylovorus DSM 19280 as a novel food-grade antifungal agent for bakery products. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2011, 146, 276–283. 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2011.02.036.

- Axel, C.; Röcker, B.; Brosnan, B.; Zannini, E.; Furey, A.; Coffey, A.; Arendt, E.K. Application of Lactobacillus amylovorus DSM19280 in gluten-free sourdough bread to improve the microbial shelf life. Food Microbiol. 2015, 47, 36–44. [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, M.; Lynch, K.M.; Zannini, E.; Arendt, E.K. Fundamental study on the improvement of the antifungal activity of Lactobacillus reuteri R29 through increased production of phenyllactic acid and reuterin. Food Control, 2018, 88, 139–148. [CrossRef]

- Petkova, M.; Stefanova, P.; Gotcheva, V.; Angelov, A. Isolation and Characterization of Lactic Acid Bacteria and Yeasts from Typical Bulgarian Sourdoughs. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 1346. [CrossRef]

- Ai, Y.; Kang, N.; Montalbán-López, M.; Wu, X.; Li, X.; Mu, D. Enhanced stability, quality and flavor of bread through sourdough fermentation with nisin-secreting Lactococcus lactis NZ9700. Food Biosci. 2024, 62, 105484. [CrossRef]

- Thanjavur, N.; Sangubotla, R.; Lakshmi, B.A.; Rayi, R.; Mekala, C.D.; Reddy, A.S.; Viswanath, B. Evaluating the antimicrobial and apoptogenic properties of bacteriocin (nisin) produced by Lactococcus lactis. Process Biochem. 2022, 122, 76–86. [CrossRef]

- Abd-Elhamed, E.Y.; El-Bassiony, T.A.E.R.; Elsherif, W.M.; Shaker, E.M. Enhancing Ras cheese safety: antifungal effects of nisin and its nanoparticles against Aspergillus flavus. BMC Vet. Res. 2024, 20(1), 493. [CrossRef]

- Yilmaz, B.; Bangar, S.P.; Echegaray, N.; Suri, S.; Tomasevic, I.; Manuel Lorenzo, J.; Melekoglu, E.; Rocha, J.M.; Ozogul, F. The Impacts of Lactiplantibacillus plantarum on the Functional Properties of Fermented Foods: A Review of Current Knowledge. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 826. [CrossRef]

- Wen, L.S.; Philip, K.; Ajam, N. Purification, characterization and mode of action of plantaricin K25 produced by Lactobacillus plantarum. Food Control 2016, 60, 430–439. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Han, J.; Bie, X.; Lu, Z.; Zhang, C.; Lv, F. Purification and characterization of plantaricin JLA-9: a novel bacteriocin against Bacillus spp. produced by Lactobacillus plantarum JLA-9 from Suan-Tsai, a traditional Chinese fermented cabbage. J. Agric.Food Chem. 2016, 64(13), 2754–2764. [CrossRef]

- Digaitiene, A.; Hansen, Å.S.; Juodeikiene, G.; Eidukonyte, D.; Josephsen, J. Lactic acid bacteria isolated from rye sourdoughs produce bacteriocin-like inhibitory substances active against Bacillus subtilis and fungi. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2012, 112(4), 732–742. [CrossRef]

- Chen, X. Y.; Levy, C.; Gänzle, M.G. Structure-function relationships of bacterial and enzymatically produced reuterans and dextran in sourdough bread baking application. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2016, 239, 95–102. [CrossRef]

- Martin, H.; Maris, P. Synergism between hydrogen peroxide and seventeen acids against five Agri-food-borne fungi and one yeast strain. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2012, 113, 1451–1460. [CrossRef]

- Liu, A.; Xu, R.; Zhang, S.; Wang, Y.; Hu, B.; Ao, X.; Li, Q.; Li, J.; Hu, K.; Yang, Y.; Liu, S. Antifungal mechanisms and application of lactic acid bacteria in bakery products: a review. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 924398. [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Figueroa, R.H.; Morales-Camacho, J.I.; Mani-López, E.; López-Malo, A. Assessment of antifungal activity of aqueous extracts and protein fractions from sourdough fermented by Lactiplantibacillus plantarum. Future Foods 2024c, 9, 100314. [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Figueroa, R.H.; Mani-López, E.; López-Malo, A. Antifungal Capacity of Poolish-Type Sourdough Supplemented with Lactiplantibacillus plantarum and Its Aqueous Extracts In Vitro and Bread. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 1813. [CrossRef]

- Muhialdin, B.J.; Hassan, Z.; Saari, N. In vitro antifungal activity of lactic acid bacteria low molecular peptides against spoilage fungi of bakery products. Ann. Microbiol. 2018, 68(9), 557–567. [CrossRef]

- Ebrahimi, M.; Sadeghi, A.; Mortazavi, S.A. The use of cyclic dipeptide producing LAB with potent anti-aflatoxigenic capability to improve techno-functional properties of clean-label bread. Ann. Microbiol. 2020, 70, 24. [CrossRef]

- Dal Bello, F.; Clarke, C.I.; Ryan, L.A.M.; Ulmer, H.; Schober, T.J.; Ström, K., Sjögren, J.; van Sinderen, D.; Schnürer, J.; Arendt, E.K. Improvement of the quality and shelf life of wheat bread by fermentation with the antifungal strain Lactobacillus plantarum FST 1.7. J. Cereal Sci. 2007. 45(3), 309–318. [CrossRef]

- Ryan, L.A.M.; Dal Bello, F.; Arendt, E.K.; Koehler, P. Detection and Quantitation of 2,5-Diketopiperazines in Wheat Sourdough and Bread. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2009, 57(20), 9563–9568. [CrossRef]

- Nionelli, L.; Wang, Y.; Pontonio, E.; Immonen, M.; Rizzello, C.G.; Maina, H. N.; Katina, K.; Coda, R. Antifungal effect of bioprocessed surplus bread as ingredient for bread-making: Identification of active compounds and impact on shelf-life. Food Control 2020, 118, 107437. [CrossRef]

- Coda, R.; Cassone, A.; Rizzello, C.G.; Nionelli, L.; Cardinali, G.; Gobbetti, M. Antifungal Activity of Wickerhamomyces Anomalus and Lactobacillus Plantarum during Sourdough Fermentation: Identification of Novel Compounds and Long-Term Effect during Storage of Wheat Bread. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2011, 77, 3484–3492. [CrossRef]

- Thiele, C.; Gänzle, M.G.; Vogel, R.F. Contribution of sourdough lactobacilli, yeast, and cereal enzymes to the generation of amino acids in dough relevant for bread flavour. Cereal Chem. 2002, 79(1), 45–51. [CrossRef]

- Biesiekierski, J.R. What is gluten? J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2017, 32, 78–81. [CrossRef]

- Rahimi, D.; Auld, K.; Sadeghi, A.; Kashaninejad, M.; Ebrahimi, M.; Zhang, J.; Gänzle, M.G. Optimising bread preservation: use of sourdough in combination with other clean label approaches for enhanced mould-free shelf life of bread. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2025, 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Hassan, Y.I.; Zhou, T.; Bullerman, L.B. Sourdough lactic acid bacteria as antifungal and mycotoxin-controlling agents. Food Sci. Technol. Int. 2015, 22(1), 79–90. [CrossRef]

- Özdemir, N.; Gül, H. Effects of fermentation time, baking, and storage on ochratoxin A levels in sourdough flat bread. Food Sci. Nutr. 2024. 12(10), 7370–7378. [CrossRef]

- Noroozi, R.; Kobarfard, F.; Rezaei, M.; Ayatollahi, S.A.; Paimard, G.; Eslamizad, S.; Razmjoo, F.; Sadeghi, E. Occurrence and exposure assessment of aflatoxin B1 in Iranian breads and wheat-based products considering effects of traditional processing. Food Control, 2022, 138, 108985. [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Koehler, P.; Rychlik, M. Effect of sourdough processing and baking on the content of enniatins and beauvericin in wheat and rye bread. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2014, 238(4), 581–587. [CrossRef]

- Cao, H.; Meng, D.; Zhang, W.; Ye, T.; Yuan, M.; Yu, J.; Wu, X.; Li, Y.; Yin, F.; Fu, C.; Xu, F. Growth inhibition of Fusarium graminearum and deoxynivalenol detoxification by lactic acid bacteria and their application in sourdough bread. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 56(5), 2304–2314. [CrossRef]

- Badji, T.; Durand, N.; Bendali, F.; Piro-Metayer, I.; Zinedine, A.; Salah-Abbès, J.B.; Montet, D.; Riba, A.; Brabet, C. In vitro detoxification of aflatoxin B1 and ochratoxin A by lactic acid bacteria isolated from Algerian fermented foods. Biol. Control, 2023, 179, 105181. [CrossRef]

- Zadeike, D.; Vaitkeviciene, R.; Bartkevics, V.; Bogdanova, E.; Bartkiene, E.; Lele, V.; Juodeikiene, G.; Cernauskas, D.; Valatkeviciene, Z. The expedient application of microbial fermentation after whole-wheat milling and fractionation to mitigate mycotoxins in wheat-based products. LWT, 2021, 137, 110440. [CrossRef]

- Vidal, A.; Marín, S.; Morales, H.; Ramos, A.J.; Sanchis, V. The fate of deoxynivalenol and ochratoxin A during the breadmaking process, effects of sourdough use and bran content. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2014, 68, 53–60. 10.1016/j.fct.2014.03.006.

- Banu, I.; Dragoi, L.; Aprodu, I. From wheat to sourdough bread: A laboratory scale study on the fate of deoxynivalenol content. Quality Assurance and Safety of Crops & Foods, 2014, 6(1), 53–60. [CrossRef]

- Iosca, G.; Fugaban, J.I.I.; Özmerih, S.; Wätjen, A.P.; Kaas, R.S.; Hà, Q.; Shetty, R.; Pulvirenti, A.; De Vero, L.; Bang-Berthelsen, C.H. Exploring the Inhibitory Activity of Selected Lactic Acid Bacteria against Bread Rope Spoilage Agents. Fermentation 2023, 9, 290. [CrossRef]

- Pereira, A.P.M.; Stradiotto, G.C.; Freire, L.; Alvarenga, V.O.; Crucello, A.; Morassi, L.L.; Silva, F.P.; Sant’Ana, A.S. Occurrence and enumeration of rope-producing spore forming bacteria in flour and their spoilage potential in different bread formulations. Lwt 2020, 133, 110108. [CrossRef]

- Çakır, E.; Arıcı, M.; Durak, M.Z.; Karasu, S. The molecular and technological characterization of lactic acid bacteria in einkorn sourdough: Effect on bread quality. J. Food Meas. Charact. 2020, 14, 1646–1655. [CrossRef]

- Maidana, S.D.; Ficoseco, C.A.; Bassi, D.; Cocconcelli, P.S.; Puglisi, E.; Savoy, G.; Vignolo, G.; Fontana, C. Biodiversity and technological-functional potential of lactic acid bacteria isolated from spontaneously fermented chia sourdough. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2020, 316, 108425. [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Siepmann, F.B.; Tovar, L.E.R.; Chen, X.; Gänzle, M.G. Effect of copy number of the spoVA2mob operon, sourdough and reutericyclin on ropy bread spoilage caused by Bacillus spp. Food Microbiol. 2020, 91, 103507. [CrossRef]

- Pahlavani, M.; Sadeghi, A.; Ebrahimi, M.; Kashaninejad, M.; Moayedi, A. Application of the selected yeast isolate in type IV sourdough to produce enriched clean-label wheat bread supplemented with fermented sprouted barley. J. Agric. Food Res. 2024, 15, 101010. [CrossRef]

- Shahryari, S.; Sadeghi, A.; Ebrahimi, M.; Mahoonak, A.S.; Moayedi, A. Evaluation of probiotic and antifungal properties of the yeast isolated from buckwheat sourdough. Iranian Food Science & Technology Research Journal/Majallah-i Pizhūhishhā-yi ̒Ulūm va Sanāyi̒-i Ghaz̠āyī-i Īrān, 2022, 18(5), 575. [CrossRef]

- Milani, J.; Heidari, S. Stability of ochratoxin A during bread making process. J. Food Saf. 2017, 37(1), e12283. [CrossRef]

- Hermann, M.; Petermeier, H.; Vogel, R.F. Development of novel sourdoughs with in situ formed exopolysaccharides from acetic acid bacteria. European Food Research and Technology, 2015, 241(2), 185–197. [CrossRef]

- Mohd Roby, B. H.; Muhialdin, B.J.; Abadl, M.M.T.; Mat Nor, N.A.; Marzlan, A.A.; Lim, S.A.H., N.A. Mustapha; Meor Hussin, A.S. Physical properties, storage stability, and consumer acceptability for sourdough bread produced using encapsulated kombucha sourdough starter culture. J. Food Sci. 2020, 85(8), 2286–2295. [CrossRef]

- Kilmanoglu, H.; Akbas, M.; Cinar, A.Y.; Durak, M.Z. Kombucha as alternative microbial consortium for sourdough fermentation: Bread characterization and investigation of shelf life. Int. J. Gastron. Food Sci. 2024, 35, 100903. [CrossRef]

- Calvert, M.D.; Madden, A.A.; Nichols, L.M.; Haddad, N.M.; Lahne, J.; Dunn, R.R.; McKenney, E.A. A review of sourdough starters: Ecology, practices, and sensory quality with applications for baking and recommendations for future research. PeerJ 2021, 9, e11389. [CrossRef]

- Pontonio, E., Verni, M., Montemurro, M., Rizzello, C.G. Sourdough: A Tool for Non-conventional Fermentations and to Recover Side Streams. In Handbook on Sourdough Biotechnology; Gobbetti, M., Gänzle, M., Eds.; Springer; Cham, Switzerland, 2023, 257–302. [CrossRef]

- Banovic, M.; Arvola, A.; Pennanen, K.; Duta, D.E.; Brückner-Gühmann, M., Lähteenmäki, L., Grunert, K.G. Foods with increased protein content: A qualitative study on European consumer preferences and perceptions. Appetite 2018, 125, 233–243. [CrossRef]

- Oleinikova, Y.; Maksimovich, S.; Khadzhibayeva, I.; Khamedova, E.; Zhaksylyk, A.; Alybayeva, A. Meat quality, safety, dietetics, environmental impact, and alternatives now and ten years ago: a critical review and perspective. Food Prod. Process. Nutr. 2025, 7(1), 18. [CrossRef]

- Gobbetti, M.; De Angelis, M.; Di Cagno, R.; Polo, A.; Rizzello, C.G. The sourdough fermentation is the powerful process to exploit the potential of legumes, pseudo-cereals and milling by-products in baking industry. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2020, 60(13), 2158–2173. [CrossRef]

- Ameur, H.; Arora, K.; Polo, A.; Gobbetti, M. The sourdough microbiota and its sensory and nutritional performances. In Good Microbes in Medicine, Food Production, Biotechnology, Bioremediation, and Agriculture; de Bruijn, F.J., Smidt, H., Cocolin, L.S., Sauer, M., Dowling, D., Thomashow, L., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, New Jersey, USA, 2022, 169–184. 10.1002/9781119762621.ch14.

- Aspri, M., Mustač, N. Č., Tsaltas, D. Non-cereal and Legume Based Sourdough Metabolites. In Sourdough Innovations; Garcia-Vaquero, M., Rocha, J.M.F., Eds.; CRC Press, Boca Raton, USA, 2023, 63–86. 10.1201/9781003141143-4.

- Vurro, F.; Santamaria, M.; Summo, C.; Pasqualone, A.; Rosell, C.M. Exploring the functional potential of pea-based sourdough in traditional durum wheat focaccia: Role in enhancing bioactive compounds, in vitro antioxidant activity, in vitro digestibility and aroma. J. Funct. Foods, 2024, 123, 106607. [CrossRef]

- Patrascu, L.; Vasilean, I.; Turtoi, M.; Garnai, M.; Aprodu, I. Pulse germination as tool for modulating their functionality in wheat flour sourdoughs. Qual. Assur. Saf. Crops Foods, 2019, 11(3), 269–282. [CrossRef]

- Cacak-Pietrzak, G.; Sujka, K.; Księżak, J.; Bojarszczuk, J.; Dziki, D. Sourdough wheat bread enriched with grass pea and lupine seed flour: Physicochemical and sensory properties. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13(15), 8664. [CrossRef]

- Drakula, S.; Novotni, D.; Mustač, N.Č.; Voučko, B.; Krpan, M.; Hruškar, M.; Ćurić, D. Alteration of phenolics and antioxidant capacity of gluten-free bread by yellow pea flour addition and sourdough fermentation. Food Biosci. 2021, 44, 101424. [CrossRef]

- González-Montemayor, A.M.; Solanilla-Duque, J.F.; Flores-Gallegos, A.C.; López-Badillo, C.M.; Ascacio-Valdés, J.A.; Rodríguez-Herrera, R. Green Bean, Pea and Mesquite Whole Pod Flours Nutritional and Functional Properties and Their Effect on Sourdough Bread. Foods 2021, 10, 2227. [CrossRef]

- Verni, M., Wang, Y., Clement, H., Koirala, P., Rizzello, C. G., Coda, R. Antifungal peptides from faba bean flour fermented by Levilactobacillus brevis AM7 improve the shelf-life of composite faba-wheat bread. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2023, 407, 110403. [CrossRef]

- Hajinia, F.; Sadeghi, A.; Sadeghi Mahoonak, A. The use of antifungal oat-sourdough lactic acid bacteria to improve safety and technological functionalities of the supplemented wheat bread. J. Food Safety, 2021, 41(1), e12873. [CrossRef]

- Çakır, E.; Arıcı, M.; Durak, M.Z. Biodiversity and techno-functional properties of lactic acid bacteria in fermented hull-less barley sourdough. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 2020, 130(5), 450-456. [CrossRef]

- Korcari, D.; Secchiero, R.; Laureati, M.; Marti, A.; Cardone, G.; Rabitti, N. S.; Ricci, G.; Fortina, M. G. Technological properties, shelf life and consumer preference of spelt-based sourdough bread using novel, selected starter cultures. LWT 2021, 151, 112097. [CrossRef]

- Rizi, A.Z.; Sadeghi, A., Jafari, S. M., Feizi, H., & Purabdolah, H. Controlled fermented sprouted mung bean containing ginger extract as a novel bakery bio-preservative for clean-label enriched wheat bread. J. Agric. Food Res. 2024, 16, 101218. [CrossRef]

- Rizi A.Z.; Sadeghi A, Feizi H, Jafari S M, Purabdolah H. Evaluation of textural, sensorial and shelf-life characteristics of bread produced with mung bean sourdough and saffron petal extract. FSCT 2024, 21(148), 141–153. URL: http://fsct.modares.ac.ir/article-7-72055-en.html.

- Aryashad, M.; Sadeghi, A.; Nouri, M.; Ebrahimi, M.; Kashaninejad, M.; Aalami, M. Use of fermented sprouted mung bean (Vigna radiata) containing protective starter culture LAB to produce clean-label fortified wheat bread. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2023, 58(6), 3310–3320. [CrossRef]

- Rasoulifar, M.; Sadeghi, A.; Hajinia, F.; Ebrahimi, M.; Ghorbani, M. Effect of the Controlled Fermented Sprouted Lentil Containing Fennel Extract on the Characteristics of Wheat Bread. Iran. Food Sci. Technol. Res. J., 2024, 20(4), 433–446. [CrossRef]

- Dopazo, V.; Musto, L.; de Melo Nazareth, T.; Lafuente, C.; Meca, G.; Luz, C. Revalorization of rice bran as a potential ingredient for reducing fungal contamination in bread by lactic acid bacterial fermentation. Food Biosci. 2024, 58, 103703. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Xie, C.; Pulkkinen, M.; Edelmann, M.; Chamlagain, B.; Coda, R.; Sandell, M.; Piironen, V.; Maina, N.H.; Katina, K. In situ production of vitamin B12 and dextran in soya flour and rice bran: A tool to improve flavour and texture of B12-fortified bread. LWT, 2022, 161, 113407. [CrossRef]

- Păcularu-Burada, B.; Georgescu, L.A.; Vasile, M.A.; Rocha, J.M.; Bahrim, G.-E. Selection of Wild Lactic Acid Bacteria Strains as Promoters of Postbiotics in Gluten-Free Sourdoughs. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 643. [CrossRef]

- Schettino, R.; Pontonio, E.; Gobbetti, M.; Rizzello, C.G. Extension of the Shelf-Life of Fresh Pasta Using Chickpea Flour Fermented with Selected Lactic Acid Bacteria. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 1322. [CrossRef]

- Hoehnel, A.; Bez, J.; Sahin, A.W.; Coffey, A.; Arendt, E.K.; Zannini, E. Leuconostoc citreum TR116 as a Microbial Cell Factory to Functionalise High-Protein Faba Bean Ingredients for Bakery Applications. Foods 2020, 9, 1706. [CrossRef]

- Rouhi, E.; Sadeghi, A.; Jafari, S.M.; Abdolhoseini, M.; Assadpour, E. Effect of the controlled fermented quinoa containing protective starter culture on technological characteristics of wheat bread supplemented with red lentil. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2023, 60(8), 2193–2203. [CrossRef]

- Kia, P.S.; Sadeghi, A.; Kashaninejad, M.; Zarali, M.; Khomeiri, M. Application of controlled fermented amaranth supplemented with purslane (Portulaca oleracea) powder to improve technological functionalities of wheat bread. Appl. Food Res. 2024, 4(1), 100395. [CrossRef]

- Ebrahimi, M.; Sadeghi, A.; Sarani, A.; Purabdolah, H. Enhancement of technological functionality of white wheat bread using wheat germ sourdough along with dehydrated spinach puree. J. Agric. Sci. Technol. 2021, 23(4), 839–851. URL: http://jast.modares.ac.ir/article-23-37775-en.html.

- Omedi, J.O.; Huang, J.; Huang, W.; Zheng, J.; Zeng, Y.; Zhang, B.; Zhou, L.; Zhao, F.; Li, N.; Gao, T. Suitability of pitaya fruit fermented by sourdough LAB strains for bread making: its impact on dough physicochemical, rheo-fermentation properties and antioxidant, antifungal and quality performance of bread. Heliyon, 2021, 7(11), e08290. [CrossRef]

- Zarali, M.; Sadeghi, A.; Ebrahimi, M.; Jafari, S.M.; Mahoonak, A.S. Techno-nutritional capabilities of sprouted clover seeds sourdough as a potent bio-preservative against sorbate-resistant fungus in fortified clean-label wheat bread. Food Measure 2024, 18, 5577–5589. [CrossRef]

- Mantzourani, I.; Daoutidou, M.; Plessas, S. Impact of Functional Supplement Based on Cornelian Cherry (Cornus mas L.) Juice in Sourdough Bread Making: Evaluation of Nutritional and Quality Aspects. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 4283. [CrossRef]

- Mantzourani, I.; Daoutidou, M.; Terpou, A.; Plessas, S. Novel Formulations of Sourdough Bread Based on Supplements Containing Chokeberry Juice Fermented by Potentially Probiotic L. paracasei SP5. Foods 2024, 13, 4031. [CrossRef]

- Plessas, S.; Mantzourani, I.; Alexopoulos, A.; Alexandri, M.; Kopsahelis, N.; Adamopoulou, V.; Bekatorou, A. Nutritional Improvements of Sourdough Breads Made with Freeze-Dried Functional Adjuncts Based on Probiotic Lactiplantibacillus plantarum subsp. plantarum and Pomegranate Juice. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 1113. [CrossRef]

- Neylon, E.; Nyhan, L.; Zannini, E.; Sahin, A.W.; Arendt, E.K. From Waste to Taste: Application of Fermented Spent Rootlet Ingredients in a Bread System. Foods 2023, 12, 1549. [CrossRef]

- Dopazo, V.; Illueca, F.; Luz, C.; Musto, L.; Moreno, A.; Calpe, J.; Meca, G. Evaluation of shelf life and technological properties of bread elaborated with lactic acid bacteria fermented whey as a bio-preservation ingredient. LWT, 2023, 174, 114427. [CrossRef]

- Luz, C.; Quiles, J. M.; Romano, R.; Blaiotta, G.; Rodríguez, L.; Meca, G. Application of whey of Mozzarella di Bufala Campana fermented by lactic acid bacteria as a bread biopreservative agent. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 56(9), 4585–4593. [CrossRef]

- Izzo, L.; Luz, C.; Ritieni, A.; Mañes, J.; Meca, G. Whey fermented by using Lactobacillus plantarum strains: A promising approach to increase the shelf life of pita bread. J. Dairy Sci. 2020, 103(7), 5906–5915. [CrossRef]

- Bartkiene, E.; Bartkevics, V.; Lele, V.; Pugajeva, I.; Zavistanaviciute, P.; Zadeike, D.; Juodeikiene, G. Application of antifungal lactobacilli in combination with coatings based on apple processing by-products as a bio-preservative in wheat bread production. J. Food Sci.Technol. 2019, 56, 2989–3000. [CrossRef]

- Bartkiene, E.; Bartkevics, V.; Lele, V.; Pugajeva, I.; Zavistanaviciute, P.; Mickiene, R.; Zadeike, D.; Juodeikiene, G. A concept of mould spoilage prevention and acrylamide reduction in wheat bread: Application of lactobacilli in combination with a cranberry coating. Food Control, 2018, 91, 284–293. [CrossRef]

- Sharaf, O.; Ibrahim, G.A.; Mahammad, A.A. Prevention of mold spoilage and extend the shelf life of bakery products using modified mixed nano fermentate of Lactobacillus sp. Egypt. J. Chem. 2023, 66(12), 207–215. [CrossRef]

- Gregirchak, N.; Stabnikova, O.; Stabnikov, V. Application of lactic acid bacteria for coating of wheat bread to protect it from microbial spoilage. Plant Foods Hum. Nutr. 2020, 75(2), 223–229. [CrossRef]

- Iosca, G.; Turetta, M.; De Vero, L.; Bang-Berthelsen, C. H.; Gullo, M.; Pulvirenti, A. Valorization of wheat bread waste and cheese whey through cultivation of lactic acid bacteria for bio-preservation of bakery products. LWT, 2023, 176, 114524. [CrossRef]

- Calabrese, F.M.; Ameur, H.; Nikoloudaki, O.; Celano, G.; Vacca, M.; Lemos Junior, W.J.F.; Manzari, C.; Vertè, F.; Di Cagno, R.; Pesole, G.; De Angelis, M.; Gobbetti, M. Metabolic framework of spontaneous and synthetic sourdough metacommunities to reveal microbial players responsible for resilience and performance. Microbiome 2022, 10, 148 . [CrossRef]

| Name | Systematic name | Producing LAB species | Affected molds | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Saturated aliphatic fatty acids | ||||

| Formic* | formic |

F. sanfranciscensis; L. plantarum and F. rossiae |

A. niger, F. graminearum, P. expansum, and M. sitophila; P. roqueforti |

[103]; [97] |

| Acetic* | acetic | F. sanfranciscensis | A. niger, P. paneum | [25,93,94] |

| Propionic* | propanoic |

F. sanfranciscensis; L. buchneri and L. diolivorans |

A. niger, F. graminearum, P. expansum, and M. sitophila; A. clavatus, Cladosporium spp., Mortierella spp. and P. roquefortii |

[103]; [99] |

| Butyric | butanoic | F. sanfranciscensis | A. niger, F. graminearum, P. expansum, and M. sitophila | [103] |

| n-Valeric | pentanoic | F. sanfranciscensis | A. niger, F. graminearum, P. expansum, and M. sitophila | [103] |

| Caproic* | hexanoic | F. sanfranciscensis | A. niger, F. graminearum, P. expansum, and M. sitophila | [103] |

| Capric | decanoic | L. reuteri | A. niger | [104] |

| Hydroxy acids and phenyl substituted acids | ||||

| Lactic* | 2-hydroxypropanoic |

L. acidophilus, L. casei; W. cibaria, L. plantarum subsp. plantarum, L. pseudomesenteroides, F. sanfranciscensis, L. brevis, and L. pentosus |

P. crysogenum, P. corylophilum; A. flavus, A. niger, P. expansum |

[73]; [81] |

| Hydro-cinnamic | 3-phenylpropanoic | L. amylovorus | A. fumigatus | [105] |

| Phenyl-lactic* | 2-hydroxy-3-phenylpropanoic |

L. plantarum; L. bulgaricus; L. amylovorus; L. reuteri and, L. brevis |

E. repens, E. rubrum, P. corylophilum, P. roqueforti, P. expansum, E. fibuliger, A. niger, A. flavus, M. sitophila, and F. graminearum; A. niger and P. polonicum; F. moniliformis, F. graminearum, F. verticillioides and P. expansum; environmental moulds; Fusarium culmorum and environmental moulds |

[96]; [76]; [101]; [106]; [47]; [107] |

| Phloretic | 3-(4-hydroxyphenyl)propanoic | L. amylovorus | environmental moulds | [47,106] |

| Hydroxy-phenyl-lactic | 2-hydroxy-3-(4-hydroxyphenyl)propanoic | L. amylovorus |

A. fumigatus; environmental moulds |

[105]; [47,106] |

| Hydro-caffeic | 3-(3,4-dihydroxyphenyl)propanoic |

L. amylovorus |

F. culmorum, environmental moulds | [47] |

| Hydro-ferulic | 3-(4-hydroxy-3-methoxyphenyl)propanoic | L. amylovorus | F. culmorum, environmental moulds | [47,106] |

| 2-Hydroxyiso-caproic | 2-hydroxy-4-methylpentanoic | L. amylovorus, L. reuteri, and L. brevis | F. culmorum, environmental moulds | [47] |

| 3-Hydroxy-capric | 3-hydroxydecanoic | L. reuteri | A. niger | [104] |

| 3-Hydroxy-lauric | 3-hydroxydodecanoic | L. reuteri | A. niger | [104] |

| Unsaturated phenyl-substituted acids | ||||

| ρ-Coumaric | (2E)-3-(4-Hydroxyphenyl)prop-2-enoic) | L. amylovorus | A. fumigatus | [105] |

| Caffeic | (2E)-3-(3,4-dihydroxyphenyl)prop-2-enoic | L. plantarum | P. expansum, P. roqueforti, P. camemberti, F. moniliformis, F. graminearum, F. verticillioides, A. niger, and A. parasiticus | [101] |

| Ferulic | (2E)-3-(4-hydroxy-3-methoxyphenyl)prop-2-enoic | L. brevis | F. culmorum, environmental moulds | [47] |

| 2-Methyl-cinnamic | 2e-3-2-methylphenylprop-2-enoic acid | L. amylovorus | A. fumigatus | [105] |

| Sinapic | 3-(4-hydroxy-3,5-dimethoxyphenyl)prop-2-enoic acid | L. bulgaricus | F. moniliformis, F. graminearum, F. verticillioides, and P. expansum | [101] |

| Polyphenol compound | ||||

| Chlorogenic | (1S,3R,4R,5R)-3-{[(2E)-3-(3,4-Dihydroxyphenyl)prop-2-enoyl]oxy}-1,4,5-trihydroxycyclohexane-1-carboxylic acid | L. plantarum and L. bulgaricus | P. expansum, P. roqueforti, P. camemberti, F. moniliformis, F. graminearum, F. verticillioides, A. niger, and A. parasiticus | [101] |

| Dicarboxylic acids | ||||

| Azelaic | nonanedioic | L. amylovorus and L. reuteri | F. culmorum, environmental moulds | [47] |

| Uronic acids | ||||

| D-Glucuronic acid | (2S,3S,4S,5R,6R)-3,4,5,6-Tetrahydroxyoxane-2-carboxylic acid | L. amylovorus | A. fumigatus | [105] |

| Benzoic (aromatic) acids | ||||

| Salicylic | 2-hydroxybenzoic acid | L. amylovorus | A. fumigatus | [105] |

| Gallic | 3,4,5-trihydroxybenzoic | L. plantarum | P. expansum, P. roqueforti, P. camemberti, F. moniliformis, F. graminearum, F. verticillioides, A. niger, and A. parasiticus | [101] |

| Vanillic | 4-hydroxy-3-methoxybenzoic | L. plantarum and L. bulgaricus | P. expansum, P. roqueforti, P. camemberti, F. moniliformis, F. graminearum, F. verticillioides, A. niger, and A. parasiticus | [101] |

| Syringic | 4-hydroxy-3,5-dimethoxybenzoic | L. plantarum | P. expansum, P. roqueforti, P. camemberti, F. moniliformis, F. graminearum, F. verticillioides, A. niger, and A. parasiticus | [101] |

| Component | LAB | Target | Mode of action | Refference |

| Einkorn sourdough | L. paraplantarum and P. acidilactici | B. subtilis ATCC6633, B. cereus ATCC11778 | Not studied | [141] |

| L. crustorum and L. brevis | Penicillium carneum, A. flavus and A. niger. | |||

| Oat-sourdough | P. pentosaceus | A. flavus | Increased total phenolic content and antioxidant activity | [163] |

| Hull-less barley sourdough | P. acidilactici and L. plantarum | P. carneum, A. flavus, and A. niger | Not studied | [164] |

| Spelt-based sourdough | W. cibaria and P. pentosaceus | F. verticillioides, A. flavus | Not studied | [165], |

| Fermented sprouted mung bean sourdough | L. brevis | A. niger | Not studied | [166,167] |

| Fermented sprouted mung bean sourdough | P. pentosaceus | A. niger | Not studied | [168] |

| Fermented sprouted lentil with fennel extract | P. acidilactici | A. niger | Not studied | [169] |

| 20 % of rice bran | L. plantarum |

Penicillium commune and A. flavus; aflatoxin |

Lactic and phenyllactic acids | [170] |

| 50% of fermented soya flour and rice bran | Propionibacterium freudenreichii and W. confusa | Environmental molds | Acetic and propionic acids | [171] |

| Fermented extracts of chickpea, quinoa, and buckwheat flour | Lactobacillus spp., Leuconostoc spp. | A. niger, A. flavus, Penicillium spp., Bacillus spp. | Organic acids |

[172] |

| Fermented chickpea flour | L. plantarum and F. rossiae | P. roqueforti, P. paneum, and P. carneum | Peptides of 12-20 amino residues | [173] |

| Fermented faba bean flour (30%) | L. brevis | P. roqueforti | Peptides of 11–22 amino acid residues, encrypted into sequences of vicilin and legumin type B; defensin-like protein (8,792 Da) and a non-specific lipid-transfer protein (11,588 Da) | [162] |

| Fermented faba bean flour (15%) | L. citreum | Potentially antifungal | Lactic, acetic, 4-hydroxybenzoic, caffeic, coumaric, ferulic, phenyllactic acids | [174] |

| Fermented quinoa and red lentil supplement | Enterococcus hirae | Environmental molds | Not studied | [175] |

| Fermented amaranth sourdough supplemented with purslane powder | L. brevis | A. niger | Not studied | [176] |

| Wheat germ sourdough along with dehydrated spinach puree | L. lactis | A. flavus | Not studied | [177] |

| 20% of fermented pitaya fruit | L. plantarum and P. pentosaceus | A. niger, Cladosporium sphaerospermum, and P. chrysogenum | Phenolic acids: gallic, caffeic, protocatechuic; increased antioxidant activity | [178] |

| Sprouted clover seeds sourdough | Lacticaseibacillus rhamnosus | Aspergillus brasiliensis | Increased antioxidant activity | [179] |

| Fermented cornelian cherry supplement | L. plantarum ATCC 14917 | Environmental molds, Bacillus spp. | Increased total phenolic content and antioxidant activity; lactic, acetic, formic, n-valeric, and caproic acids | [180] |

| Fermented chokeberry juice supplement | L. paracasei | Environmental molds, Bacillus spp. | Lactic and acetic acids; increased total phenolic content and antioxidant activity | [181] |

| Fermented pomegranate juice supplement | L. plantarum | Environmental molds, Bacillus spp. | Increased total phenolic content; lactic acid, acetic acid | [182] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).