Positionality Statement

As an autistic and ADHD-identifying researcher and practitioner, this article is deeply grounded in my lived experiences within systems that often fail to support neurodivergent individuals in the workplace. I have worked across many autism and mental health organizations providing respite care, urgent response, program delivery and children/youth skill-building programs. I have supported autistic clients while navigating these environments myself as someone on the spectrum. Disclosure has consistently been fraught with risk, leading instead to surveillance, marginalization, and emotional harm. Accommodations offered to me were often not tools for growth but restrictions. This perspective article integrates lived experience with research to reframe workplace “support” as something that must emerge from authentic inclusion, not compliance.

Introduction

Autistic adults face persistent underemployment despite strong credentials and motivation [

1,

2]. In the UK, only 29 percent of working-age autistic adults are employed [

3], and similar disparities exist in Canada and the US [

4]. These inequities reflect institutional exclusion rather than individual deficits.

Workplace policies that prioritize behavioural coaching, soft-skills training, and masking place adaptation burdens on autistic people while systemic barriers, biased hiring practices, performative accommodations, inadequate training, and unsafe disclosure environments persist [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9]. Disclosure, framed as a support pathway, carries stigma without psychological safety; masking exacts heavy psychological tolls, resulting in burnout and reduced well-being [

10]. When accommodations occur, they are often reactive and restrictive rather than empowering. Experiences vary across intersecting identities: racialized, gender-diverse, and socioeconomically marginalized individuals face compounded exclusion rarely addressed by universal initiatives [

10].

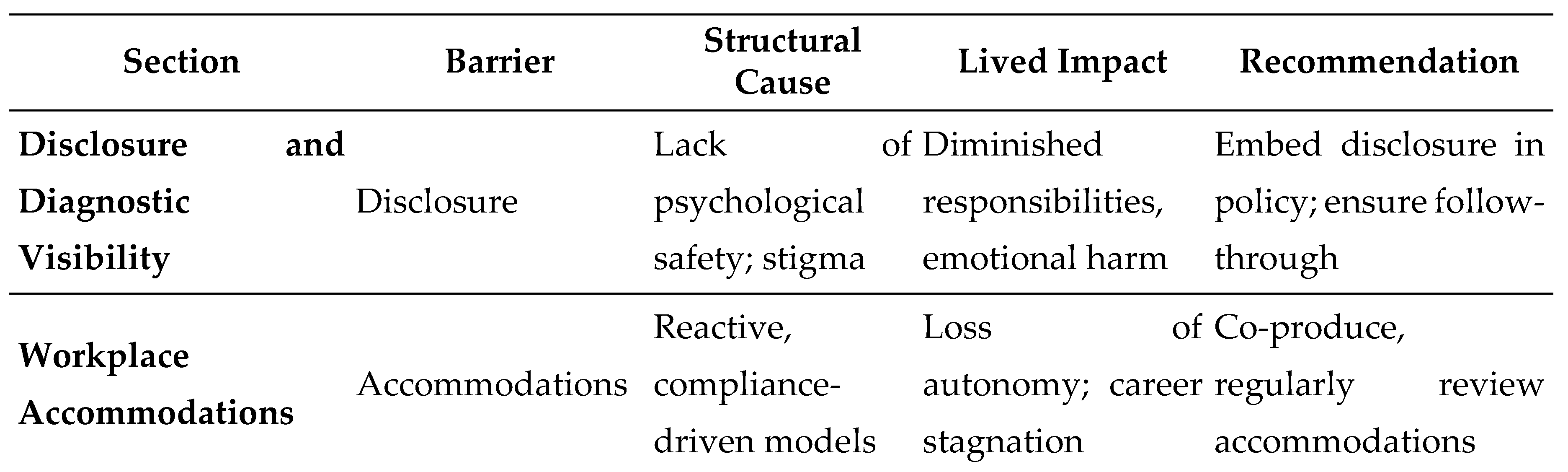

Figure 1.

Summary of employment barriers for autistic adults, aligned with article sections, structural causes, lived impacts, and reforms. Disclosure and Diagnostic Visibility.

Figure 1.

Summary of employment barriers for autistic adults, aligned with article sections, structural causes, lived impacts, and reforms. Disclosure and Diagnostic Visibility.

Disclosure of an autism diagnosis in the workplace constitutes a deeply strategic and often precarious decision for autistic individuals. While disclosure is frequently portrayed as a pathway to accessing support, empirical studies reveal that outcomes are highly contingent on organizational culture, managerial responsiveness, and broader power systems. Disclosure is not merely a procedural act but is embedded within socio-organizational dynamics, perceptions of psychological safety, and stigma anticipation [

11].

My disclosures have often been met with lowered expectations, micromanagement, and subtle forms of exclusion. I was framed as someone to be “managed,” not empowered. My workload was reduced without discussion, and I was removed from collaborative tasks. Instead of being supported to grow, I was put inside a box. My contributions were filtered through a deficit lens. Team members began associating me with the clients we supported, collapsing my identity into a stereotype. I felt pressure to appear “more autistic” to justify support, even as I struggled with mental health impacts from the disclosure itself. Ideas I contributed were often dismissed before being tested. Disclosure did not result in inclusion but led to distress and professional isolation. The emotional strain was immense, especially as I was simultaneously expected to perform emotional labour and serve others, all while feeling invisible in the eyes of my colleagues.

Many autistic participants who disclosed during the hiring process received no formal accommodations [

12]. Prompting structural adjustments, disclosure often exposed individuals to subtle stereotyping and marginalization. There are documented inconsistencies in post-disclosure support in Canadian workplaces, where implementation was frequently ad hoc and dependent on individual supervisors rather than codified organizational practices [

2].

Norris et al. [

8] provide nuanced insight into the conditional benefits of disclosure. In their mock interview study, autistic candidates who disclosed their diagnosis were rated more positively on motivation, competence, and interpersonal ability than those who did not. However, this positive shift only occurred when interviewers had a basic understanding of autism. Without structural investment in autism-specific training, disclosure may reinforce bias instead of reducing it.

Theorizing disclosure through a social identity lens,

Togher and Jay [

11] argue that decisions to disclose are shaped by both internalized autistic identity and anticipated stigma. Autistic adults who report strong identification with their diagnosis are more likely to disclose, especially when they perceive organizational environments as inclusive. In contrast, those who fear negative stereotyping often conceal their diagnosis, leading to unmet needs and increased masking burdens.

Huang et al. [

13] found that the diagnosis’s perceived legitimacy and timing, particularly when delivered in adulthood, significantly shaped internalized stigma, and subsequent disclosure confidence. Their findings indicate that invalidating diagnostic experiences can foster self-doubt and delay self-advocacy, especially when diagnostic framing emphasizes pathology over identity. The authors emphasize that organizational environments lacking neurodiversity-affirming language may inadvertently reinforce this internalization, compounding reluctance to disclose. These findings support the need for institutional discourse and practice to shift from deficit-based medicalization toward validation and empowerment as part of broader structural reform.

Recent research underscores the importance of preparing autistic individuals to navigate disclosure contexts. Leadbitter et al. [

14] suggest that self-advocacy is crucial to disclosure success, especially in unsupportive or uncertain organizational environments. Autistic individuals with access to self-determination training are more likely to disclose constructively and request support with confidence. Khalifa et al. [

15] in a scoping review of workplace accommodations, found that formal instruction in advocacy and rights-based navigation significantly improved employment outcomes and autonomy.

In my professional experience working within autism and mental health organizations, settings that explicitly positioned themselves as inclusive due to their role in supporting vulnerable populations, the realities surrounding disclosure were often contradictory. Despite the outward emphasis on acceptance, disclosing my diagnosis frequently resulted in subtle yet consequential forms of marginalization. My professional contributions were treated with increased scrutiny, collaborative opportunities were reduced, and I was perceived more as someone requiring oversight than a colleague with relevant expertise. Disclosure, rather than fostering inclusion, often reinforced a perception of vulnerability or incompetence.

Conversely, choosing not to disclose did not mitigate these challenges. Without explaining my communication style, challenges or working methods, colleagues often attributed differences to deficiency. I was viewed as unfit, out of sync, or lacking capability, which are all judgments that further intensified the need to mask and perform beyond capacity. These dynamics produced a sustained sense of precarity, regardless of the decision to disclose.

Such experiences underscore the structural nature of the problem: it is not disclosure itself that determines outcomes, but the organizational context in which it occurs. Even within sectors committed to care and support, inclusive rhetoric does not always translate into inclusive practice. Without systemic change through culturally competent leadership, neuro-affirmative policy, and relationally attuned workplace norms, disclosure will continue to be a high-stakes decision for autistic professionals, and masking will remain a coping strategy rather than a choice.

Workplace Accommodations

Workplace accommodations are often positioned as neutral or benevolent supports, yet my lived experience suggests otherwise. After disclosing my diagnosis, I was frequently placed on internal support plans that gradually reduced my responsibilities under the guise of helping. My workload was simplified, collaborative tasks reassigned, and developmental opportunities quietly withdrawn. While these changes were framed as accommodations, they functioned more like professional containment. There was no co-design, no meaningful dialogue, and no consideration of how my strengths could be built upon. The accommodations were static, non-negotiable, and rooted in deficit assumptions. I was not asked what I needed to succeed; I was told how I should adapt. These decisions eroded my confidence and sent a message that disclosure justified diminished expectations.

Accommodation processes often become overly formalized and rigid, failing to capture individual realities [

5] and are treated as isolated acts rather than embedded components of organizational accessibility; however, in many workplaces, accommodations remain reactive and compliance-driven, implemented only after difficulties arise rather than proactively supporting success. Meaningful accommodations require collaboration. They should emerge from a shared understanding between employee and employer, be revisited regularly, and be evaluated for impact. Autistic professionals should be active participants in determining what support looks like, not passive recipients of one-size-fits-all adjustments. When implemented effectively, accommodations can unlock potential, build trust, and foster sustainability. But without intention, they risk becoming mechanisms of subtle exclusion policies that create visibility without agency. My experience shows that what is needed is not more forms or checklists, but relational accommodation support rooted in recognition, flexibility, and investment. Accommodations should be strengths-based, not constraint-driven. To be effective, they must be about fostering growth, not minimizing disruption.

Masking and Burnout

Masking is defined as the intentional or unconscious suppression of autistic traits to conform to neurotypical norms and is a widely reported phenomenon among autistic employees. It is frequently used as a strategy to avoid stigma, social exclusion, or negative performance evaluations. However, masking is not a neutral behavioural adaptation; it is a cognitively and emotionally taxing form of self-regulation that contributes to long-term psychological harm, identity fragmentation, and burnout [

1,

9].

Masking is not just an act, but it is a condition for survival. I learned early in my career that authenticity was not welcome. I constantly monitored my speech, suppressed my natural gestures, and recalibrated my tone to sound more ‘professional,’ which really meant neurotypical. The exhaustion this caused was profound. It was not just that I was tired; I began to lose touch with who I was. The toll of that disconnection accumulated slowly but severely, leading to anxiety, insomnia, and persistent self-doubt.

The structural environments I worked in amplified this. I was often made to feel that no matter how much effort I gave, I would never be ‘enough.’ My colleagues and supervisors rarely engaged with me as a peer. I felt constantly surveilled, never for how well I worked, but for how closely I conformed. The more effort I put in, the more I was misunderstood. My style, my passion, and my energy were misread as overcompensation. I was not seen as accomplished; I was seen as compensating for a deficit.

In a comparative study conducted by Pryke-Hobbes et al. [

1], autistic adults engaged in significantly higher levels of masking than non-autistic neurodivergent or neurotypical individuals, especially in workplaces lacking explicit inclusion policies or psychological safety. Participants described altering their speech patterns, facial expressions, and physical behaviours to avoid appearing “unprofessional,” a concept implicitly tied to neurotypical communication standards.

Raymaker et al. [

2] conceptualize masking as a form of emotional labour. Autistic individuals in their qualitative study articulated the experience of maintaining a “social performance” throughout the workday, often at the expense of their mental health and authenticity. This effort led to cumulative exhaustion, heightened anxiety, and diminished job satisfaction, resulting in absenteeism and eventual disengagement from the workforce.

Tomczak and Kulikowski [

3] extended this line of inquiry by applying the Job Demands Resources (JD-R) framework to autistic burnout. Their findings indicate that burnout is not a byproduct of autism itself but rather the outcome of an imbalance between job demands (such as constant masking, inflexible tasks, and social pressure) and insufficient resources (such as tailored supervision, autonomy, or accommodations). The study provides strong evidence that workplace environments designed around neurotypical expectations systematically erode the well-being of autistic workers.

Autistic masking has been conceptualized as a structurally coerced adaptation to stigma, not a discretionary behavioural strategy [

4]. Grounded in social identity theory, this analysis locates masking within power dynamics that reward neurotypical conformity while penalizing autistic authenticity. The illusion of choice surrounding masking obscures its role as a defensive response to social exclusion, normative surveillance, and professional precarity. This framing reframes masking not as psychological coping, but as institutionalized self-suppression. The findings substantiate the view that autistic burnout results from cumulative identity erosion shaped by inaccessible systems, validating the need for structural, not individual, intervention.

Masking is often intensified following non-affirmative disclosure experiences. When disclosure does not lead to meaningful accommodations, as demonstrated in prior studies [

5,

6], autistic employees may continue to mask to compensate for the lack of structural support, thereby perpetuating cycles of exhaustion. This dynamic is further reinforced by findings that workplace accommodations yield long-term well-being benefits only when sustained by ongoing cultural and supervisory reinforcement [

7]. One-off adjustments do little to reduce masking if employees continue to fear social judgment or disciplinary consequences. Additionally, in environments lacking structured accessibility, disclosure can increase pressure to conform, further exacerbating identity suppression [

4] .These patterns highlight the need for disclosure and accommodation processes to be embedded within institutional policy, not reliant on individual negotiation or managerial discretion [

7].

Institutional neurodiversity frameworks have been shown to reproduce stigma by framing autistic difference as a managerial risk [

8]. Rather than dismantling exclusionary norms, these initiatives often reinforce deficit-oriented paradigms under the guise of inclusivity. Organizational discourse may co-opt diversity language while maintaining normative standards of competence and behaviour [

8]. Such frameworks can mandate assimilation through superficial accommodations, masking systemic gatekeeping as progressive reform. This underscores the necessity of co-produced, rights-based disclosure processes embedded within accountability structures. Disclosure must challenge, not accommodate, institutional bias. Without structural recalibration, stigma persists beneath rhetoric that presents itself as equity-driven.

Masking is best understood as a symptom of organizational inaccessibility. It is not simply a personal coping mechanism but a systemic outcome of workplaces that valorize conformity over authenticity [

4]. Masking has been conceptualized as a compelled adaptation to stigma, not a discretionary behaviour, and framed as a survival strategy imposed by deficit-oriented environments [

4]. Autistic burnout has been defined as a distinct syndrome marked by chronic exhaustion, diminished capacity, and loss of function resulting from sustained masking and identity suppression [

2]. Addressing masking and burnout requires structural interventions that validate neurodivergent expression, promote transparency in social expectations, and protect autistic workers from penalization for difference.

Hiring and Interview Practices

Interviews have always felt like minefields. The second I disclosed my diagnosis, I saw a visible shift in perspective. Interviewers’ expressions flattened, their tone changed, and they suddenly looked less interested. When I did not disclose, I spent days preparing to mask: rehearsing tone, simulating eye contact, and memorizing scripts. Either way, I was being judged on presentation, not potential. It felt like I was putting on a performance and acting in a way that did not represent who I was.

What helped support me through interviews was transparency. Interviews where expectations were laid out, questions shared in advance, and competencies evaluated flexibly allowed me to show my value. In most cases, even probation periods served as extended interviews where I was judged on attendance, participation in in-person events, or how well I “fit in” rather than how well I did my job. I was subjected to accommodation plans not because I lacked skill, but because I didn’t socialize as expected or seem as neurotypical as someone else. That is not inclusion, but conformity wrapped in policy.

Interview reform is necessary but insufficient to address the dehumanizing nature of conventional hiring for autistic professionals. Existing structural biases in hiring practices undermine equity, as interviews are constructed to privilege neurotypical modes of communication and social interaction [

9,

10,

11,

12]. These formats heavily rely on implicit social norms, eye contact, verbal spontaneity, and informal rapport, systematically disadvantaging candidates who process information or communicate differently [

9,

10]. Assessment procedures often operate less as evaluations of job-relevant capability and more as filters for social conformity [

9]. In simulated interview scenarios, autistic candidates with equivalent qualifications are consistently rated lower by interviewers, whose interpretations of reduced small talk, atypical tone, or facial affect are misattributed to incompetence or lack of motivation [

9,

12]. This dynamic entrenches exclusion and reinforces organizational gatekeeping, resulting in the systematic denial of opportunities for otherwise capable autistic individuals.

Disclosure of an autism diagnosis can attenuate misinterpretations during interviews, but only when interviewer training includes foundational autism knowledge [

12]. Ratings of autistic candidates improve with disclosure solely in contexts where evaluators possess relevant awareness; otherwise, disclosure confers no advantage and may reinforce bias. These outcomes highlight the insufficiency of individual-level strategies and the imperative for systemic interviewer education and standardized evaluative protocols.

Virtual interview coaching interventions incorporating strengths-based feedback enhance candidates’ self-advocacy and accommodation requests [

17]. However, their effectiveness is dependent on the employer’s willingness to value neurodivergent communication styles. Structural barriers persist even when candidates are thoroughly prepared, indicating that systemic responsiveness, not individual adaptation, determines successful outcomes. Greater integration of these interventions within organizational practice is warranted to realize equitable hiring.

Meta-analytic evidence confirms that pre-released questions, visual aids, and work-sample assessments improve competency measurement and reduce reliance on implicit social metrics [

10]. Despite their proven efficacy, these approaches are infrequently adopted, reflecting institutional inertia and reluctance to disrupt traditional models of assessment. Adoption of alternative assessment modalities should be prioritized to ensure alignment with neurodivergent strengths.

Intersectional analyses reveal that autistic applicants with additional marginalized identities, such as racial minorities or gender-diverse individuals, are at heightened risk of being overlooked in interviews [

18]. This compounding of disadvantage emerges from the confluence of disability and broader social biases, underscoring the necessity for hiring reforms that explicitly address intersectional exclusion. Data-driven monitoring and inclusive practice guidelines are critical to mitigate these disparities.

Supported internship programs developed through co-production with autistic stakeholders result in measurable gains in work-readiness, interview confidence, and sustained employment outcomes [

19]. These findings validate collaborative program design as essential for systemic transformation rather than symbolic compliance.

Training and Organizational Culture

Training programs intended to enhance autism inclusion in the workplace frequently fail to produce enduring organizational change. Despite the widespread adoption of diversity and inclusion initiatives, empirical evidence demonstrates that conventional autism training delivered via brief seminars, online modules, or general awareness campaigns does not significantly improve employee confidence or competence in supporting autistic colleagues [

12,

19]. A national survey of UK education sector employees found no meaningful difference in self-reported competence between those who had received autism training and those who had not, underscoring the limitations of informational training that does not address practical application or challenge entrenched normative biases [

12]. Additional research reveals that workplace understanding of autism is shaped more by personal relationships with autistic individuals than by institutional training programs [

19].

Effective training must move beyond awareness, directly engaging with organizational culture, power dynamics, and lived experience. Essential supervisory practices identified in the literature include flexibility, strength-based mentoring, trauma-informed engagement, normalization of neurodivergent behaviour, explicit communication, and authentic mentorship [

18]. These strategies cannot be transmitted through passive learning alone but require immersive, context-sensitive, and co-produced educational models [

18].

Inclusive practices must be embedded within organisational infrastructure rather than relegated to accommodation checklists.[

20] Evidence demonstrates that accessible communication channels, adaptable workflows, and flexible spatial design are fundamental to sustainable inclusion [

20]. Research further reveals that autistic communication styles are frequently perceived as rude or inappropriate when assessed against dominant politeness norms, highlighting that training programs failing to address these cultural frames perpetuate exclusion under the guise of inclusion [

21].

A longitudinal perspective demonstrates that ad hoc accommodations and one-time training interventions do not generate long-term gains in productivity or job satisfaction [

15]. Effectiveness is observed only when ongoing supervisory engagement, inclusive leadership practices, and mechanisms for accountability accompany training [

15]. These findings suggest that inclusion cannot be achieved through individual goodwill alone but requires institutional alignment and systematic evaluation.

Integration of autistic voices into training design and delivery is also critical [

12]. Participatory training models that foreground autistic expertise enable organizations to address misunderstandings and collaboratively redesign practices [

12]. When training is co-produced, it becomes a mechanism not only for competence but also for cultural transformation.

Intersectionality and Structural Marginalization

Intersectionality fundamentally shapes the lived experiences and employment outcomes of autistic adults. When neurodivergence intersects with other marginalized identities, including race, gender, and socioeconomic status, employment barriers become not merely cumulative but multiplicative. The structural and cultural obstacles embedded within organizations intensify for individuals who experience layered forms of exclusion [

21,

24].

Across diverse employment settings, research consistently demonstrates that autistic adults from racialized, gender-diverse, or economically disadvantaged backgrounds are disproportionately affected by exclusionary practices [

2,

16,

21]. They are more likely to be overlooked in hiring, to face stereotyping during disclosure, and to encounter a persistent lack of advancement opportunities. The inability of most organizational policies to address intersecting identities results in initiatives that often support only those who fit a narrow profile, neglecting those at the intersections of multiple forms of marginalization [

21,

24].

Workplace disclosure for multiply marginalized autistic individuals is frequently fraught with additional risk. Instead of facilitating support and understanding, disclosure can trigger increased scrutiny, microaggressions, or outright discrimination [

1,

8,

11,

19,

21]. Studies highlight that organizational responses to disclosure are inconsistent and frequently shaped by both visible and invisible social hierarchies [

11,

19,

24]. In many instances, accommodations are offered in a performative or ad hoc manner, with implementation dependent on managerial discretion rather than codified, equity-driven policy [

13,

14]. For racialized or gender-diverse autistic adults, this lack of structural consistency compounds their vulnerability to stereotyping and professional isolation [

2,

5,

19].

Masking, concealing autistic traits to conform to workplace expectations, is a phenomenon that is magnified among those who contend with multiple stigmatized identities [

9,

14,

24]. Masking is not merely a strategy for social acceptance; it becomes a necessity for psychological and occupational survival within environments where both ableism and other forms of bias are prevalent. Evidence indicates that such sustained masking leads to identity fragmentation, exhaustion, and long-term psychological harm, outcomes that are particularly severe for those navigating intersectional stigmas [

9,

14,

16,

24]. Organizational cultures that valorize conformity without acknowledging diversity in experience inadvertently incentivize these harmful coping mechanisms.

The role of organizational culture and leadership is crucial in either perpetuating or mitigating intersectional exclusion. While many workplaces have introduced neurodiversity initiatives, these often fall short by failing to address the complexities of intersecting identities [

5,

13,

15,

22]. Diversity trainings that are passive or generic rarely produce meaningful change, as they do not address the power dynamics and entrenched biases that shape real-world experiences. Effective initiatives must be participatory, sustained, and co-produced with input from those most affected by exclusion [

17,

18,

22]. For example, the development of trauma-informed, strengths-based supervision models and authentic mentorship has been shown to enhance inclusion and well-being for autistic employees with intersecting marginalized identities [

18,

24].

Hiring and promotion practices further illustrate how intersectional barriers operate. Simulated interview studies reveal that autistic candidates are frequently misinterpreted due to differences in communication style, eye contact, and rapport-building, all of which are filtered through the lens of implicit social norms [

7,

8,

9,

16,

23]. These biases are intensified when candidates also belong to racial or gender minorities, leading to disproportionate exclusion and underemployment [

4,

21]. Structural gatekeeping occurs not only at the point of entry but persists through informal networking, mentorship, and access to career development opportunities [

18,

19,

24].

Measurement and evaluation practices within organizations often fail to capture the full extent of intersectional disadvantage. Traditional metrics do not disaggregate data by social category, obscuring the disparities faced by the most marginalized [

20,

21]. The literature increasingly calls for equity-focused audits, data transparency, and the regular publication of inclusion outcomes that specifically address the experiences of employees at the intersection of multiple marginalized identities [

2,

19,

24].

From a personal perspective, intersectionality is not an abstract theoretical framework but a lived reality that shapes every professional encounter. Navigating the workplace as a racialized and neurodivergent individual means facing compounded barriers that are not always visible to those with greater privilege. Policies that fail to consider intersectionality serve only the most privileged autistic adults, reinforcing rather than disrupting patterns of exclusion. True equity demands systems-level reform, grounded in participatory policymaking, accountability, and a commitment to uncovering and addressing the deepest forms of structural disadvantage.

Equity in employment for autistic adults will remain aspirational unless organizations intentionally recognize, measure, and respond to the complexities of intersecting identities. Advancing inclusion requires more than representation; it necessitates redesigning organizational systems so that the most marginalized can thrive. The literature and lived experience together underscore that until intersectionality is fully integrated into both policy and practice, exclusion will persist beneath the rhetoric of inclusion.

Conclusions

Emerging Directions in Autism and Employment

Technology-Enabled Support and Digital Interventions

Technological innovation is reshaping pathways to workplace accessibility for autistic adults. Handheld cueing systems, as described by Thull and Glaser, foster career task independence and facilitate on-the-job problem-solving, reducing the need for constant supervisory intervention [

28]. Employment-related assistive technologies now encompass a spectrum of digital tools that support organization, communication, and emotional regulation [

29]. Artificial intelligence–enhanced interview preparation, including eye-tracking and cognitive feedback systems, offers actionable insights for self-presentation and stress management [

30]. The Ready2Work digital platform, co-developed with autistic job seekers, provides structured opportunities to articulate skills and preferences, helping to counteract social bias in traditional hiring [

31].

The proliferation of emotion recognition technologies introduces complex opportunities and risks. While such technologies have potential for advancing workplace inclusion, Katirai warns that algorithms may misinterpret autistic affect or promote surveillance, potentially leading to misclassification or stigma [

32]. Analysis of this literature underscores the necessity of rigorous evaluation and participatory design to ensure these tools empower rather than constrain autistic employees. Emerging evidence suggests that when technology is developed in genuine collaboration with autistic professionals, it has the potential to address longstanding barriers in communication, performance feedback, and workplace adaptation. Integration of these systems into broader organizational policy remains an important benchmark for sustained progress.

Strength-Based and Culturally Responsive Programs

Current research increasingly supports the effectiveness of strength-based, context-sensitive programming in employment transition and retention. Organizational support structures that recognize diverse skill sets and provide flexible, personalized adaptation have demonstrated significant improvements in job satisfaction and long-term retention [

33]. Programs such as the Enabling Academy, which is designed around local expertise and co-production, have achieved measurable gains in workforce participation and sustainable employment outcomes [

34]. Qualitative research indicates that career fulfillment among autistic professionals is associated with mentorship, self-advocacy training, and alignment between individual values and occupational roles [

35].

Holistic, skill-based interventions, exemplified by college transition programs targeting executive functioning and social cognition, have produced robust evidence for supporting successful transitions to adult employment [

36]. The adaptation of telehealth interventions, especially in low-resource settings, demonstrates flexibility in delivering workforce preparation and support across geographical and economic barriers [

40]. These approaches collectively reinforce the importance of moving beyond standardized, deficit-oriented interventions toward models that recognize and amplify the unique strengths and aspirations of autistic adults.

Intersectionality and Global Inclusion

An emerging consensus highlights the need to address intersectionality and global variation in workplace experiences. Research in professional fields, such as veterinary medicine, and in international contexts, including Kazakhstan, documents the compounding effects of cultural norms and policy gaps on autistic employment [

37,

39]. Studies demonstrate that individuals with intersecting marginalized identities face distinctive challenges in workplace integration, including access to advocacy, culturally sensitive support, and equitable advancement [

38,

40].

Global initiatives increasingly prioritize context-specific program design, cross-sector partnerships, and collaborative policy development. The internationalization of autism employment research brings to light the role of social determinants, such as access to peer networks, legal frameworks, and local resources, in shaping employment outcomes. Recognition of these factors is essential for the development of inclusive, sustainable, and culturally responsive interventions.

Innovative Recruitment, Training, and Metrics

Recent advances in recruitment and training practices underscore the need for neurodiversity-affirmative approaches. Strengths-based hiring, feedback-rich interview structures, and transparency in performance expectations are associated with improved access and fairness for autistic applicants [

41]. Studies of employer attitudes in the United Kingdom reveal persistent misconceptions about autistic competence and workplace adjustment, pointing to the need for policy and culture change [

42].

Artificial intelligence and digital platforms are increasingly utilized to support pre-employment training, skills assessment, and interview practice [

43]. Systematic reviews identify evidence-based practices for developing prosocial and employment skills, while quality-of-life interventions have demonstrated lasting benefits for both retention and wellbeing [

44,

45]. Evaluation frameworks are evolving beyond placement rates, incorporating metrics such as accommodation satisfaction, promotion trajectories, organizational climate, and peer support. These multi-dimensional measures are critical for assessing program effectiveness and informing continuous improvement.

Lived Experience, Community Engagement, and Policy Impact

The centrality of lived experience and participatory leadership in research and practice is now widely recognized. Initiatives such as neurodiversity-affirming resources for newly diagnosed adults and transition programs for military families have demonstrated improvements in agency, satisfaction, and employment outcomes [

46,

47].

Community engagement is critical for ensuring that employment interventions remain relevant and responsive to the evolving needs of autistic professionals. Participatory design, evaluation, and policy review have emerged as gold standards for developing interventions that reflect both the diversity and depth of autistic experience. Synthesis of the recent literature, as well as personal analytic reflection, suggests that the movement toward inclusion is most effective when guided by the insights and leadership of autistic stakeholders.

Assistive Technology and Ethical Artificial Intelligence

The expanding literature on assistive technology and artificial intelligence highlights both promise and caution. Reviews by Zhou et al. and Rumrill emphasize the dual need for user-centred design and ongoing evaluation of usability, equity, and unintended consequences [

48,

49]. Tools such as handheld cueing devices, cognitive supports, and adaptive software facilitate workplace independence and self-regulation, while also raising questions about data privacy and autonomy. Emotion recognition systems may enable or impede inclusion, depending on whether they are calibrated to diverse neurocognitive profiles and are used within ethical frameworks.

The practical implications of these technologies for workplace adaptation are significant. When integrated with organizational policy and professional development, such tools can address barriers in communication, task management, and feedback. The literature suggests that the most successful interventions are those that embed assistive technology into systemic strategies for inclusion rather than deploying it in isolation.

Structural Pressures, Disclosure Dynamics, and Inclusive Design

Emerging literature has turned critical attention to the structural conditions that constrain how autistic professionals navigate expression and identity at work. Recent findings highlight that both masking and visible autistic expression are surveilled within normative frameworks that position deviation as liability [

50]. Autistic individuals are penalized whether they conceal traits or express them openly, indicating that neither strategy guarantees psychological safety or professional legitimacy [

50]. These dynamics reflect a form of organizational gatekeeping that rewards conformity while pathologizing authenticity. Inclusion cannot rest on tolerance of difference conditioned by behavioural acceptability; it must instead be anchored in redesign that removes the need for such calibration altogether.

Research on presenteeism demonstrates the cost of this structural misalignment. Among Japanese white-collar workers, higher levels of autistic traits and social camouflaging were strongly correlated with presenteeism—continued work attendance despite cognitive, psychological, or emotional strain [

51]. These outcomes show that masking is not merely a personal strategy but a symptom of institutional inaccessibility. When the effort to meet implicit social expectations undermines capacity, both employees and organizations suffer. Structural efforts to mitigate presenteeism must shift from individual resilience to proactive workplace environments that affirm neurodivergent expression and prioritize psychological sustainability.

Inclusive design is increasingly operationalized through co-produced, evidence-based employment models. A longitudinal protocol for an end-to-end supported employment program emphasizes universal design, participatory development, and systems-level integration across the employment trajectory [

52]. This framework embeds accessibility from hiring to retention, aligning practice with the structural reforms demanded by neurodivergent professionals. Complementing this, adaptations of the Individual Placement and Support model to autistic job seekers have shown how mainstream vocational models can be effectively modified through coordinated supports, rapid job placement, and integrated mental health services [

53]. These initiatives reflect a shift from individualized remediation to collective accountability and infrastructure-level change.

Disclosure remains a central axis of inclusion but is increasingly recognized as contingent on institutional readiness. Experimental findings reveal that disclosure improves interview evaluations only when interviewers have received neurodiversity training; in its absence, disclosure offers no advantage and may activate bias [

54]. These findings confirm that disclosure cannot be treated as a universal mechanism for equity. Effective inclusion requires not only the option to disclose but assurance that doing so will be met with competence, affirmation, and structural support. Together, these studies reinforce the imperative to move from accommodation toward integrated, relational, and rights-based redesign.

Synthesis and Future Directions

Current trends in autism and employment research point to a new paradigm: the integration of technology, strength-based practice, intersectional awareness, and participatory leadership. Advances in assistive technology, digital platforms, and evidence-based training approaches are converging to support sustained, system-level transformation. However, the future of inclusion depends on the ethical deployment of these innovations and the centring of autistic perspectives in all phases of research, policy, and practice.

In summary, the next decade of autism employment research and practice should prioritize longitudinal studies, comparative effectiveness research, and continuous evaluation of both intended and unintended consequences. Effective transformation will require the sustained commitment of organizations, communities, and policymakers to ensure that emerging directions translate to meaningful, equitable, and sustainable employment opportunities for all autistic adults.

Recommendations

Drawing on the comprehensive literature review, emerging research, and personal perspective, the following recommendations are proposed to advance equitable and sustainable employment for autistic adults:

-

Institutional Redesign and Accountability

Embed inclusion into organizational policy: Move beyond ad hoc or compliance-driven accommodations to proactive, systemic redesign that foregrounds accessibility, equity, and co-production across all employment stages [

5,

6,

12,

13,

17,

19,

20,

21,

22,

28,

30,

34,

38].

Implement cross-functional neurodiversity advisory councils: Include autistic employees in policy creation and review, supporting co-produced, participatory leadership models [

17,

19,

22,

28,

32].

Regularly audit workplace culture and climate: Conduct ongoing assessments of psychological safety and inclusion climate to identify gaps and opportunities for structural reform [

19,

21].

Standardize and disseminate disclosure best practices: Develop confidential, accessible disclosure pathways that guarantee non-discrimination and accommodation access [

1,

2,

8,

10].

Embed lived experience in policy design: Integrate autistic voices at every level of organizational development, ensuring that policies reflect authentic needs [

12,

14,

15].

Evaluate and report on inclusion outcomes: Require organizations to track, evaluate, and report on accommodation satisfaction, well-being, retention, and advancement rates among autistic employees [

6,

7,

8,

13,

14].

Protect identity expression in policy: Develop explicit safeguards against penalization for natural autistic communication or behaviour. Move beyond superficial inclusion by embedding protections for non-normative expression, reducing behavioural surveillance and double binds [

50].

-

Hiring and Interview Reform

Shift to competency-based, context-specific hiring: Replace traditional, socially loaded interviews with multi-modal, work-sample, or strengths-based assessments [

4,

6,

8,

9,

16,

27,

28,

29,

33,

35,

36].

Integrate AI and assistive technologies judiciously: Support both candidates and interviewers with AI-enabled platforms and adaptive assessments, safeguarding against bias and surveillance [

28,

32,

35,

39,

42,

43].

Facilitate structured disclosure processes: Provide clear, low-risk pathways for candidates to share needs and request support [

8,

10].

Address intersectionality in hiring: Implement targeted interventions to counter compounded disadvantage for multiply marginalized autistic applicants [

21,

24,

27,

38].

Evaluate effectiveness of hiring reforms: Use quantitative and qualitative metrics to assess if new hiring practices are achieving equity and reducing exclusion [

6,

7,

8,

14].

Disaggregate hiring data: Regularly analyze hiring outcomes by gender, race, and disability status to uncover and remedy hidden biases [

3,

11,

21,

24].

-

Inclusive Workplace Culture and Training

Mandate participatory, ongoing training: Move beyond passive modules to immersive, co-produced training that centers autistic expertise [

3,

5,

12,

13,

14,

15,

21,

22,

31,

34,

40,

45,

47].

Strengthen leadership and accountability: Link leadership evaluations and professional development to inclusion outcomes [

13,

15,

17,

19,

38,

44,

46].

Promote trauma-informed supervision: Train managers in trauma-informed practices to support well-being [

31,

41].

Mandate context-sensitive and ongoing training: Ensure training is iterative and linked to measurable changes in workplace practice [

3,

5,

12,

14].

Cultivate authentic mentorship and peer networks: Build structures that foster mentorship, community, and knowledge sharing among neurodivergent staff [

14,

15].

Continuously evaluate cultural change: Use organizational climate surveys and qualitative assessments to monitor progress and adjust strategies [

6,

7,

8,

13,

14].

Invest in co-designed employment systems: Fund and adopt end-to-end supported employment models that embed accessibility throughout recruitment, onboarding, and retention. These models should be co-developed with autistic professionals and include built-in mechanisms for evaluation and refinement. [

52].

Adapt proven vocational frameworks: Modify existing models like Individual Placement and Support (IPS) to meet autistic-specific needs, such as sensory accommodations, communication scaffolding, and long-term job coaching. Ensure fidelity to neuro-inclusive principles [

53].

-

Accommodations and Supports

Normalize and individualize accommodations: Make supports visible, proactive, and tailored, embedding environmental and process adaptations within the workplace [

1]⁻[

2,

5,

10,

13,

18,

20,

23,

24,

26,

27,

32,

38,

41].

Establish neurodiversity support liaisons: Designate staff to coordinate accommodations and advocate for autistic employees [

2,

19,

32].

Develop resource banks: Maintain accessible, centralized databases of accommodation options [

38,

41].

Prioritize consistency and structure: Shift from informal support to standardized, universally accessible processes [

1,

2,

5,

13].

Assess and improve accommodation satisfaction: Gather regular feedback from autistic employees on accommodation effectiveness and make data-driven improvements [

6,

7,

8].

Link accommodations to organizational outcomes: Measure the impact of accommodations on retention, performance, and advancement [

6,

7,

8,

13,

14].

Monitor and reduce masking-related presenteeism: Recognize camouflaging as an organizational risk factor. Incorporate measures of masking fatigue and presenteeism into wellness and performance evaluations and proactively redesign workflows to reduce masking pressures. [

51].

-

Data-Driven Metrics and Continuous Evaluation

Implement robust metrics: Track accommodation satisfaction, retention and promotion rates, and equity audits [

6,

13,

14,

17,

18,

21,

23,

28,

36,

38,

41,

44].

Publish annual inclusion impact reports: Ensure transparent reporting on progress [

5,

17,

19,

44].

Utilize intersectional metrics: Disaggregate data by gender, race, disability, and other social categories [

3,

11,

21,

24,

27,

38,

41].

Require public disclosure of inclusion progress: Organizations should publicly share annual metrics and action plans to drive accountability [

5,

17,

19].

Align evaluation with employee feedback: Regularly include lived experience in evaluation cycles [

12,

14,

15].

Fund external audits of inclusion efforts: Use third-party evaluators to benchmark, validate, and recommend improvements [

46,

49].

-

Address Intersectional and Global Barriers

Prioritize intersectionality: Audit policies for compounded disadvantage and design targeted interventions [

3,

11,

21,

22,

24,

25,

27,

30,

38,

41,

46].

Engage in global and cross-sector collaboration: Learn from culturally adapted programs and international models [

31,

32,

36,

37,

41,

45,

46,

48].

Support peer networks: Foster employee resource groups and peer mentorship initiatives [

3,

38,

46].

Ensure representation in leadership: Actively promote autistic professionals with intersecting marginalized identities into leadership positions [

17,

19,

22].

Analyze intersectional outcomes: Regularly monitor the impact of workplace policies on retention and advancement for employees at the intersection of multiple marginalized identities [

21,

24,

27,

38].

Collaborate with advocacy organizations: Build coalitions with local, national, and international groups to expand policy impact [

36,

38,

45,

46].

-

Emerging Technologies and Future-Oriented Practice

Integrate evidence-based digital and AI interventions: Leverage digital coaching, online resources, and telehealth to support autonomy and access [

28,

29,

32,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40,

42,

43,

45,

48].

Invest in research-practice partnerships: Support ongoing research and piloting of new models [

32,

33,

34,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40,

41,

42,

44,

47,

48,

49].

Evaluate long-term impact: Fund and evaluate longitudinal studies on outcomes of emerging interventions [

37,

39,

44,

48].

Assess ethical implications of emerging technology: Evaluate risks and benefits of AI and assistive tools, ensuring privacy and autonomy are prioritized [

28,

32,

35,

39,

42,

43].

Center autistic voices in tech development: Engage autistic professionals as co-designers and evaluators of new digital tools [

29,

36,

48].

Promote access to technology across socioeconomic contexts: Ensure digital interventions are equitable and inclusive of low-resource and global contexts [

36,

38,

45].

Sustained transformation requires that employers, policymakers, and practitioners move from performative gestures to meaningful, measurable, and system-wide action. Centering autistic leadership and co-production, investing in rigorous metrics, and adopting innovative, evidence-informed practices are essential to building workplaces where neurodivergent adults thrive.

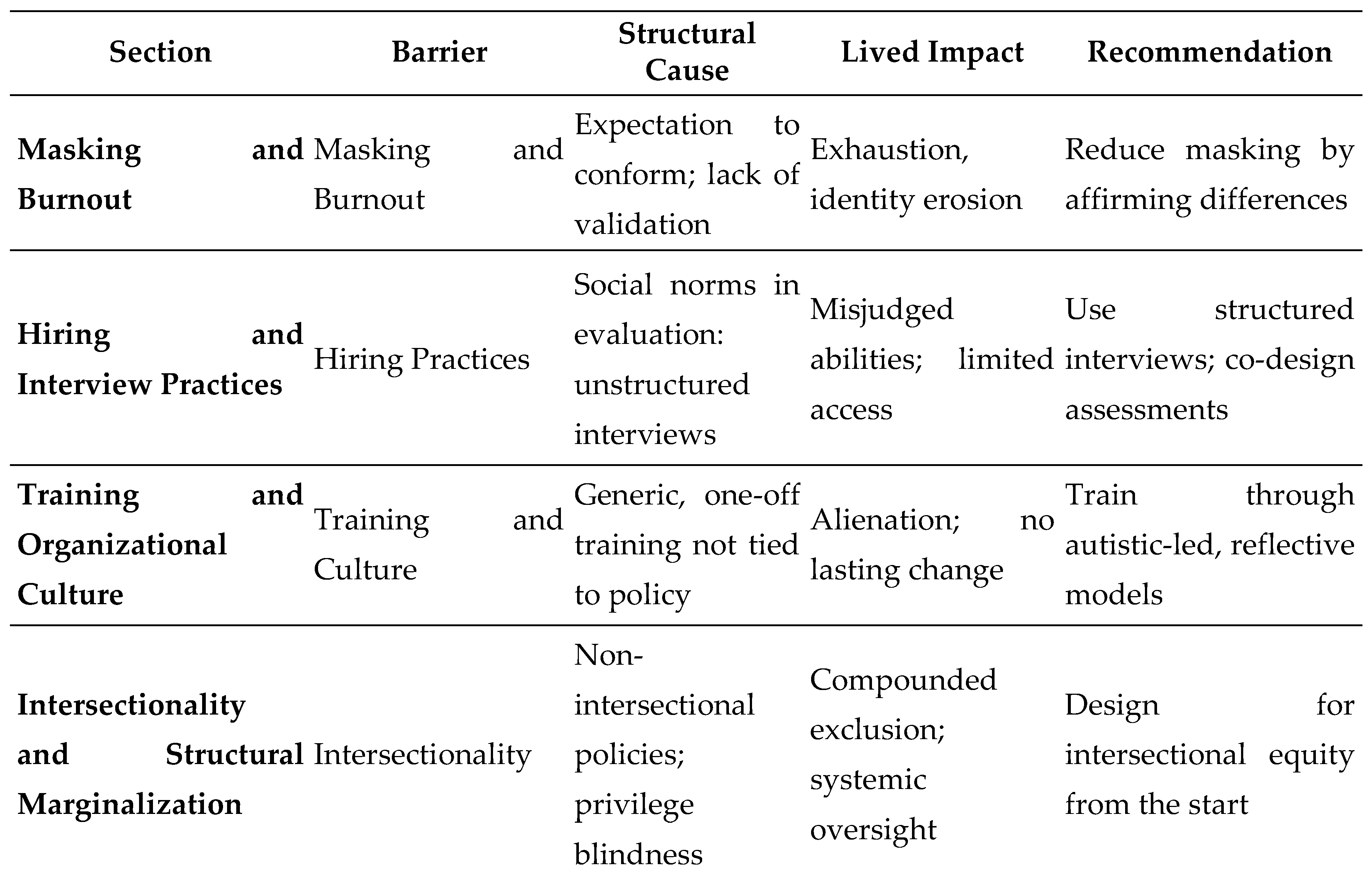

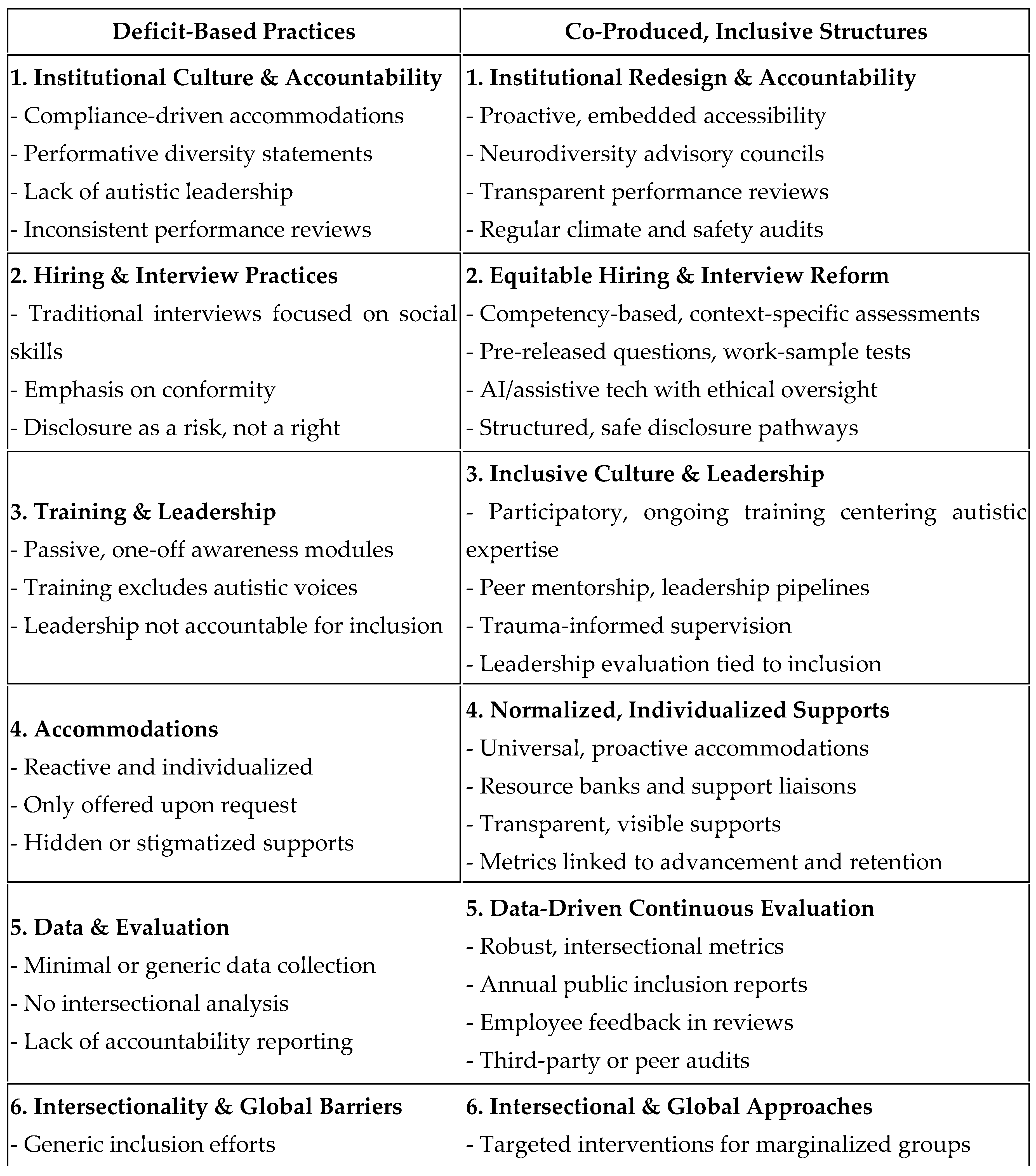

Figure 2.

A Systems-Level Shift from Deficit-Based Employment Practices to Co-Produced, Inclusive Structures for Autistic Adults.

Figure 2.

A Systems-Level Shift from Deficit-Based Employment Practices to Co-Produced, Inclusive Structures for Autistic Adults.

Acknowledgments

The author is solely responsible for the synthesis, analysis, and personal perspective shared in this article, including all lived experience content. Artificial intelligence language models (ChatGPT, OpenAI, 2024) were used to assist with language refinement, summarization, and manuscript editing. All article selection, interpretation, and integration of evidence reflect the author’s independent scholarship.

References

- Pryke-Hobbes A, Davies C, Crane L. Workplace masking experiences of autistic and non-autistic adults. Autism Adulthood. 2023;5(2):136-145. [CrossRef]

- Raymaker DM, Sharer M, Maslak J, Lund E. Narratives of autism and skilled employment: experiences of stigma, disclosure, and workplace identity. Autism. 2023;27(5):1312-1324. [CrossRef]

- Tomczak MT, Kulikowski K. Occupational burnout among autistic employees: the Job Demands–Resources perspective. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023;20(9):6023. [CrossRef]

- Pearson A, Rose K. A conceptual analysis of autistic masking: understanding the narrative of stigma and the illusion of choice. Autism Adulthood. 2021;3(1):52-60. [CrossRef]

- Petty S, Tunstall R, Richardson H, Eccles F. Supporting autistic employees: understanding and confidence in UK workplaces. J Occup Rehabil. 2023;33(1):112-124. [CrossRef]

- Genova HM, Lancaster K, Moore J, Smith T. KF STRIDE: A virtual interview coaching intervention for autistic job seekers. Disabil Rehabil. 2024;46(2):200-210. [CrossRef]

- Hartman LI, Hartman EA. Neurodiversity in the workplace: an agenda for research and action. Disabil Rehabil. 2024;46(4):645-658. [CrossRef]

- Norris J, Maras K, Heasman B, Remington A. Disclosing an autism diagnosis improves ratings of candidate performance in employment interviews. Autism Res. 2024;17(3):245-256. [CrossRef]

- Maras K, Norris J, Nicholson J, Heasman B. Autism and employment: improving job interview performance. Autism. 2021;25(5):1185-1197. [CrossRef]

- Yan, CO. Enhancing employment opportunities for individuals with autism spectrum disorder: a meta-analysis. J Vocat Rehabil. 2024;56(2):211-225.

- Togher C, Jay S. Disclosing an autism diagnosis: a social identity approach. Autism. 2023;27(7):1712-1723. [CrossRef]

- Nimante D, Laganovska E, Osgood R. To tell or not to tell—disclosure of autism in the workplace. Autism. 2023;27(4):1011-1020. [CrossRef]

- Huang Y, Trollor JN, Foley KR, Arnold SRC. “I’ve spent my whole life striving to be normal”: internalized stigma and perceived impact of diagnosis in autistic adults. Autism Adulthood. 2023;5(4):423-436. [CrossRef]

- Leadbitter K, Buckle KL, Ellis C, Dekker M. Autistic self-advocacy and the neurodiversity movement: implications for autism early intervention research and practice. Front Psychol. 2021; 12:635690. [CrossRef]

- Khalifa G, Sharif Z, Sultan M, Di Rezze B. Workplace accommodations for adults with autism spectrum disorder: a scoping review. Disabil Rehabil. 2020;42(9):1316-1331. [CrossRef]

- Lindsay S, Cagliostro E, Albarico M. Workplace disclosure and accommodations for people with autism: a systematic review. Disabil Rehabil. 2019;41(16):1887-1897. [CrossRef]

- Ashworth S, Brown H, Wray J, Lang R. Evaluating a supported employment internship programme for autistic young adults without intellectual disability. J Autism Dev Disord. 2023;53(5):1721-1735. [CrossRef]

- Ezerins M, Simon LS, Rosen CC. Autistic applicants’ job interview experiences and accommodation preferences: an intersectional analysis. J Manag. 2025;51(1):89-104.

- Dreaver J, Thompson C, Girdler S, Adolfsson M, Black M. Success factors enabling employment for adults on the autism spectrum from employers’ perspective. J Autism Dev Disord. 2020;50(5):1657-1667. [CrossRef]

- Waisman-Nitzan M, Gal E, Schreuer N. “It’s like a ramp for a person in a wheelchair”: workplace accessibility for employees with autism. Res Dev Disabil. 2021; 114:103940. [CrossRef]

- Elsayed D, Shattuck P, Cooper B, Roux A. The intersectionality of race, gender, and autism in employment settings: communication challenges and structural biases. Autism Res. 2024;17(2):215-227. [CrossRef]

- Praslova LN. Autism doesn’t hold people back at work. Discrimination does. Harv Bus Rev. July–August 2021.

- Johnson TD, Joshi A. A stigma perspective on neurodiversity research: lessons from autistic workers. Curr Opin Psychol. 2025; 62:101959. [CrossRef]

- Sreckovic MA, Brunsting NC, Able H. Coming out autistic at work: a review of the literature. Autism. 2023;27(3):799-811. [CrossRef]

- Lindsay S, Osten V, Rezai M, Bui S. Employers’ perspectives of hiring and accommodating workers with autism spectrum disorder. J Vocat Rehabil. 2021;54(2):97-107. [CrossRef]

- Petty S, Hanser CH, Williams JA, Hamilton LG. Sharing an Example of Neurodiversity Affirmative Hiring. Autism Adulthood. 2025;7(1):44-51. [CrossRef]

- Brouwers EPM, Bergijk M, van Weeghel J, Detaille S, Kerkhof H, Dewinter J. Barriers to and Facilitators for Finding and Keeping Competitive Employment: A Focus Group Study on Autistic Adults With and Without Paid Employment. J Occup Rehabil. 2025;35(1):54-65. [CrossRef]

- Jamil R, Ru OS, Lan YS, et al. Inclusive Human Capital—Employment Transition Programme for Adults with Autism at Enabling Academy, Yayasan Gamuda. Asian J Manag Cases. 2025;22(1):9-28.

- Lee SH, Kim SY, Lee K, Sim S, Park H. Beyond individual support: Employment experiences of autistic Korean designers receiving strength-based organizational support. Autism. 2025;29(4):988-1004.

- Guastella AJ, Hankin L, Stratton E, et al. Improving Accessibility for Work Opportunities for Adults With Autism in an End-to-End Supported Workplace Program: Protocol for a Mixed Methods Cohort Study. JMIR Res Protoc. 2025;14: e60806. [CrossRef]

- Viljoen M, Seris N, Shabalala N, et al. Adapting an early autism caregiver coaching intervention for telehealth delivery in low-resource settings: A South African study of the ‘what’ and the ‘why’. Autism. 2025;29(5):1246-1262.

- Day M, Wood C, Corker E, Freeth M. Understanding the barriers to hiring autistic people as perceived by employers in the United Kingdom. Autism. 2025;29(5):1263-1274.

- Kosherbayeva L, Kozhageldiyeva L, Pena-Boquete Y, Samambayeva A, Seredenko M. Effects of autism spectrum disorder on parents’ labour market: Productivity loss and policy evaluation in Kazakhstan. J Autism Dev Disord. 2025;55(3):421-438.

- Davies J, Melinek R, Livesey A, et al. “I did what I could to earn some money and be of use”: A qualitative exploration of autistic people’s journeys to career success and fulfilment. Autism. 2025;29(4):988-1004.

- Pickles K, Houdmont J, Smits F, Hill B. ‘Part of the team as opposed to watching from the outside’: Critical incident study of autistic veterinary surgeons’ workdays. Vet Rec. 2025;196(4): e4957. [CrossRef]

- Wilder TL, Stratchan NE. Artificial Intelligence-Enhanced Interview Success: Leveraging Eye-Tracking and Cognitive Measures to Support Self-Regulation in College Students with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. Educ Sci. 2025;15(2):165. [CrossRef]

- Zhou K, Richard C, Kim J. Employment-related assistive technologies for autistic individuals: A scoping review. J Vocat Rehabil. 2025;62(2):191-206. [CrossRef]

- Baker-Ericzén MJ, Schuck R, Herrera J, Gutierrez Miller I, MacDonald-Caldwell R. Piloting the College SUCCESS Curriculum on Campus: A Program to Enhance Executive Functioning and Social Cognitive Skills in Autistic College Students. Autism Adulthood. 2025;7(2):120-133. [CrossRef]

- Burnham Riosa P, Phan J, Whittingham L, et al. Ready2Work: The Development and Evaluation of a User-Informed Online Employment Website for Autistic Job Seekers. Autism Adulthood. 2025;7(2):134-145. [CrossRef]

- Hammond A, Morris J, Sabey C, Cutrer-Párraga E. Teaching social skills to adults with autism using video modeling and video prompting. Int J Dev Disabil. 2025:1-16. [CrossRef]

- May CP, Whelpley CE, Kaup R. Changing Outcomes for Job Candidates with Autism Spectrum Disorder: The Benefits of Neurodiversity Training and ASD Disclosure. J Autism Dev Disord. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Syriopoulou-Delli CK, Sarri K. Vocational rehabilitation of adolescents and young adults with autism spectrum disorder: a review. Int J Dev Disabil. 2023;71(1):41–60. [CrossRef]

- Petty S, Hanser CH, Williams JA, Hamilton LG. Sharing an Example of Neurodiversity Affirmative Hiring. Autism Adulthood. 2025;7(1):44-51. [CrossRef]

- Wu H, Savadlou A, Paul M, et al. Psychosocial Interventions and Quality of Life in Autistic Young Adults: A Systematic Review. Rev J Autism Dev Disord. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Pagán AF, Kenemore J, Ahlenius MM, Hernandez L, Armstrong S, Loveland KA, Acierno R. Launching! To Adulthood, A Culturally Adapted Treatment Program for Military-Dependent Autistic Young Adults and Their Military Parents: A Pilot Study. Mil Med. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Edwards C, Love AM, Cai RY, Heyworth M, Johnston A, Aldridge F, Gibbs V. “I’m not feeling alone in my experiences”: How newly diagnosed autistic adults engage with a neurodiversity-affirming “Welcome Pack”. Autism. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Smith H, Shaw SCK, Doherty M, Ives J. Reasonable adjustments for autistic clinicians: A qualitative study. PLoS One. 2025;20(3): e0319082. [CrossRef]

- Dulas HM, Bowman-Perrott L, Georgio TE, Dunn CM, Li YF. Increasing Prosocial Employment Skills for Adolescents With Emotional and/or Behavioral Disorders: A Systematic Review and Quality Review. Behav Disord. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Rumrill, PD. Employment and career development considerations for neurodiverse individuals. J Vocat Rehabil. 2025;62(2):103-105. [CrossRef]

- Dean M, Nordahl-Hansen A. The to be, or not to be, of acting autistic. Autism. 2025;29(3):802-814. [CrossRef]

- Sato W, Omiya T, Kumada-Deguchi N, Sankai T, Mayers T. Impact of autism spectrum disorder traits and social camouflaging on presenteeism among Japanese white-collar workers. Psychiatry Int. 2025;6(2):61. [CrossRef]

- Guastella AJ, Hankin L, Stratton E, Glozier N, Pellicano E, Gibbs V. Improving accessibility for work opportunities for adults with autism in an end-to-end supported workplace program: protocol for a mixed methods cohort study. JMIR Res Protoc. 2025;14: e60806. [CrossRef]

- Florence AC, Elwyn G, Mueser KT, McGurk SR, Liebmann EP, McLaren JL, Drake RE. Adapting individual placement and support for unemployed adults with autism spectrum disorder. J Vocat Rehabil. 2025;62(2):115-127. [CrossRef]

- May CP, Whelpley CE, Kaup R. Changing outcomes for job candidates with autism spectrum disorder: the benefits of neurodiversity training and ASD disclosure. J Autism Dev Disord. 2025. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).