1. Introduction

Life on Earth has been inextricably linked to a dynamic coexistence with microbes [

1]. From the earliest stages of development through aging, humans are continuously shaped by microbial signals encountered through environmental contact, diet, and respiration [

2]. Nowhere is this symbiosis more profound than in the gastrointestinal tract, where a densely populated and metabolically diverse microbiota transforms dietary substrates into bioactive molecules with far-reaching systemic effects—including on the brain [

3]. Among the complex network of metabolic interactions bridging the gut and distant organs, the tryptophan (Trp) metabolic axis has emerged as a pivotal regulator of immune homeostasis, neurophysiological integrity, and energy balance [

2]. Beyond serving as a precursor for serotonin and niacin, Trp is enzymatically channeled by both host and microbial systems into the kynurenine (KYN) metabolic pathway, generating a suite of metabolites capable of modulating inflammatory responses—either dampening immune activation or exacerbating pathological inflammation [

4]. Additionally, natural compounds targeting neuroinflammation are gaining attention for their antidepressant potential, offering a complementary pathway to modulate Trp metabolism [

5].

Over the past decade, next-generation sequencing and metabolomics have mapped thousands of associations between altered Trp metabolism and diseases as diverse as depression, diabetes, cancer, and Alzheimer’s disease (AD) [

6,

7]. Over the past decade, groundbreaking research has redefined our understanding of neurological diseases and mental illnesses, laying the groundwork for precision interventions [

8,

9]. Moreover, the integration of biomarkers and imaging with neuroinflammatory markers offers promising diagnostic and therapeutic insights in AD and related disorders [

10]. Similarly, phytochemicals such as phenols, alkaloids, and terpenoids have demonstrated notable neuroprotective effects against neurodegenerative disorders, offering complementary intervention strategies [

11,

12,

13,

14]. Yet association is not causation [

15]. We still lack a coherent framework linking specific microbial consortia, host enzymes such as indoleamine-2,3-dioxygenase-1 (IDO1) and tryptophan-2,3-dioxygenase-2 (TDO2), and downstream metabolites like kynurenic acid (KYNA) or quinolinic acid (QUIN) to discrete physiological outcomes [

16] (

Table 1). This gap hampers the design of targeted interventions—whether they involve probiotics, small-molecule inhibitors, or lifestyle prescriptions—that aim to rebalance Trp flux toward health-promoting routes [

17]. Recent reconceptualizations propose a paradigm shift in how Trp–KYN metabolism is targeted for innovative clinical interventions [

18].

A second challenge is spatial. Traditional bulk assays average signals across tissues and cell types, obscuring metabolic micro-domains that may act as “checkpoints” for Trp fate [

19] (

Table 1). Recent spatial-omics and single-cell technologies have begun to reveal astrocytic and microglial niches in the human prefrontal cortex, endothelial “gates” at the blood–brain barrier (BBB), and perivascular hubs in peripheral organs where KYN metabolic activity is disproportionately high [

20]. These findings demand a rewiring of our mental map: instead of a homogeneous pipeline, Trp metabolism resembles a switchboard with cell-type-specific levers that can be pharmacologically or genetically tuned [

21].

Timing is the third frontier. Circadian biologists have long known that virtually every metabolic pathway oscillates over the 24-hour day [

21]. Emerging evidence suggests that KYN metabolism is no exception and that sex hormones further modulate these rhythms [

22] (

Table 1). Clinical trials of chemotherapy and checkpoint inhibitors demonstrate that dosing time can double efficacy or halve toxicity, yet KYN-targeting agents have rarely been tested under chrono-pharmacological designs [

23]. Without granular, time-stamped metabolite monitoring, we risk missing critical windows when interventions would be most effective—or least harmful [

24].

Technological advances now offer tools to close these knowledge gaps [

25]. Stable-isotope tracing in gnotobiotic mice can timestamp flux through IDO1 versus TDO2; single-cell proteomics in intestinal organoids can pinpoint which epithelial or immune subsets respond to specific “metabokines”; and CRISPR-based kill switches or inducible operons allow synthetic consortia to dial metabolite output like a volume knob [

25,

26,

27]. Parallel progress in wearable biosensors, artificial intelligence (AI) feedback loops, and adaptive trial designs promises to link real-time biomarker readouts—such as saliva KYNA or morning KYN/TRP slopes—to dynamic adjustments in drug dose, exercise load, or probiotic composition [

28,

29,

30].

Yet formidable obstacles remain. We lack validated, non-invasive biomarkers that faithfully mirror tissue-level KYN activity [

31]. The ecological rules governing colonization by engineered microbes are not fully charted, and existing kill-switch circuits require rigorous containment testing [

27]. Regulatory frameworks struggle to keep pace with live biotherapeutic products (LBPs) that blur the line between drugs and devices [

32]. Finally, ethical and logistical challenges complicate the deployment of adaptive, time-randomized clinical trials that integrate molecular, behavioral, and environmental data streams [

33].

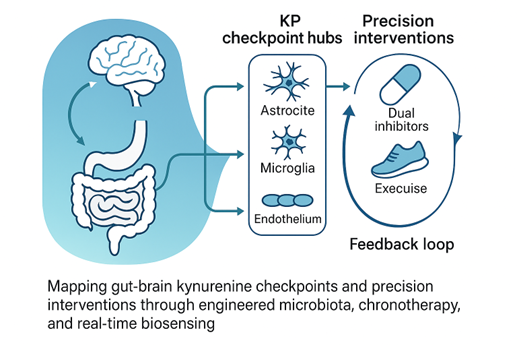

Against this backdrop, the present review aims to synthesize cutting-edge insights across microbiology, neuroscience, immunology, and bioengineering to articulate a unified roadmap for precision modulation of the Trp–KYN axis. We first survey the spatial organization of KYN metabolism “checkpoints” in the brain and periphery, highlighting how localized enzyme activity interfaces with systemic immunity and neural circuitry. We then examine sex- and circadian-specific modifiers that dictate when and how the pathway tilts toward neurotoxicity or resilience. Next, we explore microbiota-based strategies—from designer consortia to encapsulated post-biotics—that act as precision switches for Trp flux, and we discuss their manufacturing, safety, and regulatory hurdles. Finally, we outline “Intervention 2.0,” an integrated platform combining dual-enzyme inhibitors, structured exercise, and AI-driven biosensing to create closed-loop therapeutics. By weaving these threads together, we seek to move the field beyond static snapshots toward dynamic, multi-scale models that can predict individual responses and guide adaptive interventions (

Table 2). In doing so, we hope to catalyze collaborations between bench scientists, clinicians, data engineers, and regulatory experts, accelerating the translation of Trp-KYN biology into tangible health benefits.

The objectives of this review is to map the cellular and spatial heterogeneity of KYN metabolic activity and identify metabolic “checkpoints” amenable to intervention; to critically appraise evidence for sex- and circadian-dependent modulation of Trp metabolism and its clinical implications; to evaluate current and emerging microbiota-based tools for precision control of KYN flux, including synthetic consortia, kill switches, and post-biotic delivery systems; to assess the therapeutic promise and practical challenges of dual IDO1/TDO2 inhibition in conjunction with lifestyle levers such as exercise; and to propose a framework for adaptive, biomarker-guided clinical trials that integrate real-time metabolite monitoring with dosing algorithms. By addressing these aims, the review intends to illuminate fertile research avenues and provide a practical blueprint for next-generation strategies targeting the gut–brain–immune axis via the KYN metabolic pathway.

Specialized clusters of microglia, astrocytes, and endothelial cells, known as KYN checkpoints, regulate Trp catabolism and maintain immune balance throughout the brain–body axis. Spatial-omics pinpoints these hubs in the human prefrontal cortex and BBB, where KYN overload erodes neuronal resilience and fuels depression, stroke, and dementia. Peripheral checkpoints likewise calibrate T-cell vigor. Tumors hijack the circuit: chronic IDO1 activity floods the microenvironment with immunosuppressive KYN, yet IDO1 blockade alone falters, bypassed by TDO2 and alternative aryl-hydrocarbon-receptor ligands. Environmental toxins, infections, and diet further tilt these metabolic gates, whereas systemic checkpoints defend serotonin and niacin pools. Critical gaps stall translation. Cell-type-resolved maps of IDO1, TDO2, transporters, and System L remain incomplete; single-cell, longitudinal multi-omics in inflamed tissues and cancers are needed. Real-time biomarkers of KYN burden and transporter flux are lacking, complicating precision dosing. Optimal regimens for dual IDO1/TDO2 or aryhydorcarbon receptor (AhR) blockade—and for brain-penetrant microglial modulators—are undefined. Preclinical models rarely integrate microbiota composition, circadian rhythm, sex, or pollutant exposure, all strong modifiers of KYN metabolism. Bridging these voids will require integrated biosensing, adaptive trials, and machine-learning-guided strategies to tailor checkpoint-directed therapies to individual neuroimmune landscapes.

4. Sex and the Circadian City: Hidden Modifiers

Circadian rhythms and biological sex weave an under-appreciated backdrop to KYN metabolism, subtly steering mood and immune tone across the day [

112]. Sex hormones and circadian rhythms likewise modulate migraine vulnerability, further emphasizing the need for personalized neuroimmune interventions [

113]. Immune challenges such as interferon-α therapy consistently lower circulating Trp, boost KYN, and heighten depressive symptoms, but these shifts peak at distinct clock phases and manifest more severely in women [

114]. Preclinical lipopolysaccharide models echo this dimorphism, with female mice displaying protracted neuroimmune and behavioral scars that fluoxetine can erase only when given at their active phase [

115] Human imaging studies add another layer: reduced Trpand skewed KYN metabolites track hippocampal-subfield atrophy, yet the correlation tightens in early-morning scans, hinting at chronobiological gating [

116]. Rapid-acting antidepressants such as ketamine appear to reset both the monoaminergic–glutamatergic interface and downstream KYN flux, but again response rates diverge by sex and time of dosing [

114]. Post-mortem data reveal anterior cingulate cortex KYN signatures that segregate by sex and suicide status, underscoring personalized vulnerability windows [

116]. Neuroanatomical findings from autism research similarly reveal that circadian and neuroimmune factors may influence structural brain development [

117]. Collectively, these findings suggest that sex hormones and the molecular clock act as “hidden modifiers,” dictating when and how immune activation tilts KYN balance toward neurotoxicity or resilience [

118]. Similar to the evolving understanding in mental health research, recognizing sex- and circadian-dependent variability supports a dimensional view of disease vulnerability and resilience [

119]. Parsing these temporal-sexual intersections could unlock chronotherapy strategies for mood disorders.

4.1. Literature Review: Circadian Misalignment, Mood Vulnerability, and Emerging Chronotherapeutics

Longitudinal wearables reveal that phase delays in core-body temperature and melatonin release often precede mood dips in major depression and bipolar disorder, supporting circadian realignment as a digital-medicine target [

120]. In healthy adults, endogenous 24-hour rhythms modulate anxiety- and depression-like affect, with later dim-light melatonin onset and compressed phase-angle differences predicting poorer mood [

121]. Disruption of the molecular clock by hypercortisolism in Cushing’s syndrome flattens immune-cell oscillations and skews steroid profiles, illustrating endocrine–immune crosstalk [

122]. Similar circadian misalignment exacerbates autoimmunity in lupus, acting as a prodromal biomarker for flares [

123]. Non-pharmacologic interventions show promise: group music therapy realigns autonomic and melatonin rhythms in depressed women, while optimal circadian–circasemidian coupling buffers morning blood-pressure surges and fosters resilience [

121]. Nutritional modulation is equivocal; omega-3 supplementation dampens inflammation yet leaves KYN metabolism and mood unchanged in healthy men [

124]. Experimental LPS infusion acutely activates KYN metabolism, linking immune challenge, chronobiology, and affect in real time [

124]. Adolescents display bidirectional pathways: anxiety forecasts future sleep disruption, whereas a genetically longer free-running period in males predicts later mood vulnerability [

123]. Collectively, these studies underscore circadian alignment as a modifiable lever for mood regulation and highlight the need for personalized chrono-therapeutic strategies across lifespan and disease contexts.

4.2. Research Gaps: Timing, Sex, and Biomarker Integration for Precision Kynurenine (KYN) Intervention

Despite compelling evidence that dosing time and sex strongly influence chemotherapy and immunotherapy outcomes, major knowledge gaps limit translation to KYN-targeting agents [

125]. First, no clinical trials have yet tested chrono-pharmacology for IDO1/TDO2 inhibitors, KMO blockers, or KAT activators, leaving optimal schedules unexplored [

126]. Second, existing studies rarely stratify by both circadian phase and biological sex; pharmacokinetic data disaggregated for women are virtually absent, obscuring why afternoon regimens reduce toxicity in female lymphoma patients [

125]. Third, mechanistic links between peripheral clock genes, immune cell oscillations, and drug metabolism remain undefined, particularly how estrogen and glucocorticoids modulate daily fluctuations in KYN enzyme activity [

127]. Fourth, wearable-derived chronotypes are not integrated into trial design, preventing personalized timing algorithms that could harmonize drug exposure with individual rhythms [

125]. Fifth, preclinical tumor models often use male rodents housed in static light cycles, overlooking sex- and circadian-dimorphic responses seen in patients [

128]. Finally, validated real-time biomarkers that couple KYN metabolite swings to treatment efficacy are lacking, hindering adaptive dosing [

129] (

Table 5). Addressing these gaps will require multi-omic chronopharmacology studies, sex-balanced animal models, and adaptive clinical trials embedding circadian sensors to craft precision schedules for KYN-focused therapies.

4.3. Multi-Time-Point Plasma Kynurenine (KYN) Profiles Stratified by Sex and Hormonal Phase

Current evidence shows that plasma KYN levels fluctuate with sex, age, and endocrine status, yet most datasets rely on single fasting draws [

130]. Parkinson’s and breast-cancer cohorts reveal disease-specific shifts toward neurotoxic QUIN, but without high-resolution sampling it is unclear whether these changes reflect trait abnormalities or time-of-day/hormone-phase effects [

131]. Metabolomic screens (KarMeN) can classify sex and age, implying a strong biological signal, while ambulatory microdialysis (U-RHYTHM) now permits hourly hormone/metabolite capture—an underused tool for KYN kinetics [

131]. Feminizing gender-affirming hormone therapy reshapes amino-acid pools after six months; however, acute diurnal patterns and menstrual-cycle nuances remain unmapped [

132]. Animal work shows estrous-dependent adipokine oscillations, hinting that luteal-phase progesterone surges might also bias KYN flux [

132]. No study yet aligns luteal sub-phases, cytokine pulses, and KYN derivatives in healthy women, nor measures phase-specific KYN shifts during immunotherapy or antiandrogen treatment [

130]. Next steps: deploy wearable-triggered, multi-time-point plasma collection across 24-h and menstrual cycles; integrate liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry (LC-MS) panels for KYN, Trp, QUIN, and KYNA with sex-hormone, cortisol, and brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) profiles; and model trajectories using mixed-effects chronopharmacology frameworks. Such datasets will clarify whether timing and hormonal milieu confound or mediate KYN biomarkers, guiding precise sampling windows and sex-hormone-aware interventions.

4.4. Wearable Light-Exposure + Metabolite Logging to See If Circadian Misalignment Exaggerates the Quinolinic Spike

Circadian misalignment (CM) rewires metabolic, cardiovascular, and immune circuits, yet whether it magnifies neurotoxic (QUIN) surges remains untested [

133]. Night-shift paradigms reveal clock-driven insulin resistance, lipidome disruption, and blood-pressure creep, while murine models link chronic CM to immune senescence and shortened lifespan [

134]. Sex adds complexity—females show partial protection against CM on a high-fat diet—suggesting divergent QUIN trajectories [

135]. Light timing is the master zeitgeber; continuous lux logging via smartwatches can quantify misalignment magnitude, whereas ambulatory microdialysis or dried-blood-spot kits now enable multi-time-point KYN metabolite sampling [

123]. Pairing these technologies would let researchers correlate light-phase offsets with 24-h QUIN area-under-curve, stratified by sex and feeding rhythms [

136]. Key next steps includes pilot a cross-over study where shift-workers wear light- and activity-trackers plus collect hourly capillary samples across two work cycles; model QUIN dynamics versus lux-derived phase angle using mixed-effects chronobiology; overlay cortisol and melatonin rhythms to disentangle stress versus circadian effects; and test whether timed blue-light blockers, melatonin, or time-restricted feeding blunt QUIN spikes [

136] (

Table 6). Such integrative phenotyping could identify high-risk chronotypes and guide precision-timed KP interventions to mitigate CM-induced neuroinflammation.

4.5. Adaptive Trial Designs that Randomize Dose-Timing Rather Than Just Dose Size

Bayesian and response-adaptive frameworks have revolutionized dose-finding, yet virtually all published trials modulate quantity, not clock time [

137]. Radiation for pancreatic cancer, ketamine infusions for late-life depression, and molnupiravir for early COVID-19 show how real-time efficacy–toxicity trade-offs hone dose size, but none test whether morning versus evening delivery alters those curves [

138]. Chronotherapy evidence from chemotherapy and immune checkpoint inhibitors indicates that timing can double efficacy or halve toxicity, with sex as a major moderator, underscoring a missed opportunity [

139]. Key gaps include statistical models that treat dosing time as a continuous, circadian-anchored covariate; real-time biomarkers (e.g., actigraphy-derived phase angle) to guide allocation; and operational logistics for pharmacy and nursing around-the-clock interventions [

137]. Next steps include simulate Bayesian hierarchical designs where dose level and dosing hour are co-randomized, borrowing strength across adjacent time bins; integrate wearable-captured chronotype to stratify randomization and inform priors; embed rolling interim analyses that drop unfavorable time windows rather than doses; and pilot such designs in drugs with known chrono-toxicities, using point-of-care melatonin or cortisol assays as safety triggers [

140] (

Table 7). Developing regulatory guidance and EHR-linked scheduling tools will be crucial to mainstream adaptive chrono-trials, paving the way for precision-timed KP inhibitors and beyond [

139].

Table 1.

Three Translational Frontiers in Tryptophan (Trp)–Kynurenine (KYN) Research. This table outlines three key challenges impeding the development of precision interventions targeting tryptophan metabolism: (1) the lack of causal frameworks linking microbial-host-enzyme interactions to downstream metabolites and clinical outcomes; (2) insufficient spatial resolution masking critical cell- and tissue-specific metabolic hotspots; and (3) the neglect of circadian and hormonal influences on metabolic flux, limiting chronotherapeutic optimization.

Table 1.

Three Translational Frontiers in Tryptophan (Trp)–Kynurenine (KYN) Research. This table outlines three key challenges impeding the development of precision interventions targeting tryptophan metabolism: (1) the lack of causal frameworks linking microbial-host-enzyme interactions to downstream metabolites and clinical outcomes; (2) insufficient spatial resolution masking critical cell- and tissue-specific metabolic hotspots; and (3) the neglect of circadian and hormonal influences on metabolic flux, limiting chronotherapeutic optimization.

| Challenge |

|

Core Issue |

|

Implication |

1. Causal Mapping

(Conceptual Challenge) |

|

Despite thousands of disease associations, we lack a coherent causal framework linking microbiota, host enzymes (e.g., IDO1, TDO2), and metabolites (e.g., KYNA, QUIN) to physiological outcomes. |

|

Limits precision design of interventions (e.g., probiotics, enzyme inhibitors, lifestyle prescriptions). |

| 2. Spatial Resolution (Anatomical Challenge) |

|

Bulk assays obscure localized metabolic activity in specialized niches (e.g., astrocytes, microglia, BBB endothelial cells). |

|

Demands a paradigm shift: from homogeneous pathways to cell-type-specific “switchboards” requiring targeted modulation. |

| 3. Temporal Dynamics (Chronobiological Challenge) |

|

Trp–KYN flux oscillates with circadian rhythms and is modulated by sex hormones, but time-sensitive dosing is understudied. |

|

Missing chronotherapeutic windows may reduce efficacy or increase toxicity of interventions. |

Table 2.

Key Objectives for a Unified Roadmap to Precision Modulation of the Tryptophan (Trp)–Kynurenine (KYN) Axis. This table outlines five core objectives of the review: integrating spatial insights, sex and circadian modifiers, microbiota-based strategies, next-generation intervention platforms, and dynamic, multiscale modeling with cross-disciplinary collaboration to advance translational outcomes in Trp–KYN biology.

Table 2.

Key Objectives for a Unified Roadmap to Precision Modulation of the Tryptophan (Trp)–Kynurenine (KYN) Axis. This table outlines five core objectives of the review: integrating spatial insights, sex and circadian modifiers, microbiota-based strategies, next-generation intervention platforms, and dynamic, multiscale modeling with cross-disciplinary collaboration to advance translational outcomes in Trp–KYN biology.

| Objective |

|

Description |

| 1. Map Spatial “Checkpoints” |

|

Survey localized KYN metabolism niches in brain and periphery, detailing how enzyme activity in astrocytes, microglia, BBB, and peripheral hubs interfaces with immunity and circuitry. |

| 2. Characterize Sex & Circadian Modifiers |

|

Examine how sex hormones and circadian rhythms influence Trp–KYN flux, identifying periods tilting toward neurotoxicity or resilience to inform time- and sex-specific interventions. |

| 3. Develop Microbiota-Based Precision Switches |

|

Explore designer microbial consortia and encapsulated post-biotics to steer Trp flux, addressing manufacturing, safety, and regulatory considerations for clinical translation. |

| 4. Outline Integrated “Intervention 2.0” Platform |

|

Propose a closed-loop therapeutic framework combining dual enzyme inhibitors, structured exercise regimens, and AI-driven biosensing for adaptive modulation of the Trp–KYN axis. |

| 5. Build Dynamic, Multiscale Predictive Models & Networks |

|

Weave spatial, temporal, and microbiome data into predictive tools; foster collaborations among bench scientists, clinicians, data engineers, and regulators to guide personalized interventions. |

Table 3.

Next steps in precision modulation of neurovascular kynurenine (KYN) flux. This table outlines the sequential experimental steps to refine endothelial targeting, validate functional outcomes, monitor real-time neurotransmitter dynamics, evaluate effects on cancer metastasis, and ensure systemic safety, aiming to open new avenues for precise modulation of the neurovascular KYN metabolism.

Table 3.

Next steps in precision modulation of neurovascular kynurenine (KYN) flux. This table outlines the sequential experimental steps to refine endothelial targeting, validate functional outcomes, monitor real-time neurotransmitter dynamics, evaluate effects on cancer metastasis, and ensure systemic safety, aiming to open new avenues for precise modulation of the neurovascular KYN metabolism.

| Next Steps |

|

Purpose |

| 1. Build bar-coded AAV libraries to refine endothelial specificity |

|

Enhance targeting precision |

| 2. Validate knock-down efficiency and KYN metabolite flux in brain-slice co-culture |

|

Confirm functional impact on Trp metabolism |

| 3. Monitor glutamate dynamics with optogenetic reporters in vivo |

|

Track real-time neurotransmitter changes |

| 4. Assess effects on tumor infiltration and behavior in KMO-high breast-cancer metastasis models |

|

Evaluate therapeutic impact on metastasis |

| 5. Conduct parallel safety screens to chart NAD pools and mitochondrial stress in non-target tissues |

|

Ensure systemic safety and minimize off-target effects |

Table 4.

Converging Strategies for Real-Time Control and Monitoring of Cellular Function. Summary of complementary approaches integrating riboswitch-mediated gene regulation and pulsed light-induced calcium dynamics to enable real-time metabolic readouts without cellular damage.

Table 4.

Converging Strategies for Real-Time Control and Monitoring of Cellular Function. Summary of complementary approaches integrating riboswitch-mediated gene regulation and pulsed light-induced calcium dynamics to enable real-time metabolic readouts without cellular damage.

| Key Concept |

|

Mechanism |

|

Application |

|

Advantages |

| Riboswitches with Z-lock or Photocleavable Linker |

|

Light-controlled conformational changes in RNA elements regulate gene expression. |

|

Precise gating of target gene expression in living cells |

|

High specificity; reversible; minimal background activation |

| Pulsed Light-Driven Calcium Oscillations in Astrocytes |

|

Tunable light pulses induce calcium signaling cascades without causing photodamage. |

|

Real-time monitoring of cellular metabolism and signaling |

|

Non-invasive; tunable frequency/amplitude; low cytotoxicity |

Table 5.

Critical Research Gaps in Chrono-pharmacology of Kynurenine (KYN)-Targeting Agents. This table delineates six principal gaps hindering the integration of circadian and sex-specific considerations into KYN-modulating therapies. Addressing these deficits will necessitate longitudinal, multi-omic chrono-pharmacology studies, sex-balanced preclinical models, and adaptive clinical trial designs incorporating real-time circadian monitoring and biomarker-driven dosing.

Table 5.

Critical Research Gaps in Chrono-pharmacology of Kynurenine (KYN)-Targeting Agents. This table delineates six principal gaps hindering the integration of circadian and sex-specific considerations into KYN-modulating therapies. Addressing these deficits will necessitate longitudinal, multi-omic chrono-pharmacology studies, sex-balanced preclinical models, and adaptive clinical trial designs incorporating real-time circadian monitoring and biomarker-driven dosing.

| Research Gap |

|

Description |

| 1. Absence of Chrono-pharmacology Trials |

|

No clinical studies have evaluated time-of-day effects for IDO1/TDO2 inhibitors, KMO inhibitors, or KAT activators. Optimal administration schedules remain unexplored, impeding evidence-based chrono-dosing strategies. |

| 2. Inadequate Stratification by Circadian Phase and Sex |

|

Trials and PK/PD analyses seldom disaggregate data by both circadian timing and biological sex. Female-specific pharmacokinetic profiles are largely unreported, obscuring mechanistic reasons for sex-dependent toxicity reductions (e.g., afternoon regimens in lymphoma). |

| 3. Undefined Mechanistic Links between Clock Genes, Immune Oscillations, and KYN Enzyme Activity |

|

The interactions among peripheral circadian regulators, immune cell rhythmicity, and drug metabolism—especially modulation by estrogen and glucocorticoids on daily fluctuations of KYN pathway enzymes—remain mechanistically uncharacterized. |

| 4. Lack of Wearable-Derived Chronotype Integration in Trial Design |

|

Personalized chrono-type metrics from wearable sensors are not incorporated into clinical protocols. Without individual rhythm profiling, dosing algorithms cannot be tailored to synchronize drug exposure with each patient’s endogenous rhythm. |

| 5. Sex and Circadian Biases in Preclinical Models |

|

Preclinical experiments predominantly use male rodents under fixed light–dark schedules, neglecting sex-dimorphic and circadian-variant responses. This undermines translational relevance for patients exhibiting divergent chrono-biological profiles. |

| 6. Absence of Validated Real-Time Biomarkers Coupling KYN Dynamics to Efficacy |

|

There is a shortage of dynamic biomarkers that track KYN metabolite oscillations in real time and correlate these fluctuations with therapeutic outcomes. This gap limits the implementation of adaptive dosing regimens based on metabolic feedback. |

Table 6.

Key Next Steps for Circadian Misalignment and Quinolinic Acid (QUIN) Dynamics Intervention Studies. This table summarizes the proposed strategies to investigate how circadian misalignment influences QUIN dynamics and to evaluate interventions that may mitigate these effects in shift workers through real-time monitoring and targeted therapies.

Table 6.

Key Next Steps for Circadian Misalignment and Quinolinic Acid (QUIN) Dynamics Intervention Studies. This table summarizes the proposed strategies to investigate how circadian misalignment influences QUIN dynamics and to evaluate interventions that may mitigate these effects in shift workers through real-time monitoring and targeted therapies.

| Next Steps |

|

Purpose |

| 1. Pilot a cross-over study where shift workers wear light and activity trackers and collect hourly capillary samples across two work cycles |

|

Capture real-time physiological and circadian data in shift workers |

| 2. Model QUIN dynamics versus lux-derived phase angle using mixed-effects chronobiology |

|

Analyze the relationship between light exposure patterns and QUIN fluctuations |

| 3. Overlay cortisol and melatonin rhythms to disentangle stress versus circadian effects |

|

Separate stress-induced effects from circadian-driven changes in biomarkers |

| 4. Test whether timed blue light blockers, melatonin, or time-restricted feeding blunt QUIN spikes |

|

Evaluate interventions to mitigate QUIN elevations linked to circadian misalignment |

| 5. Pilot a cross-over study where shift workers wear light and activity trackers and collect hourly capillary samples across two work cycles |

|

Capture real-time physiological and circadian data in shift workers |

Table 7.

Next Steps in Chronopharmacology-Informed Adaptive Trial Designs. This table outlines the strategic steps to develop and pilot advanced Bayesian hierarchical models that integrate dosing time and level, wearable-derived chronotype data, and real-time safety biomarkers, aiming to optimize precision chronotherapy in clinical trials.

Table 7.

Next Steps in Chronopharmacology-Informed Adaptive Trial Designs. This table outlines the strategic steps to develop and pilot advanced Bayesian hierarchical models that integrate dosing time and level, wearable-derived chronotype data, and real-time safety biomarkers, aiming to optimize precision chronotherapy in clinical trials.

| Next Steps |

|

Purpose |

| 1. Simulate Bayesian hierarchical designs co-randomizing dose level and dosing hour, borrowing strength across adjacent time bins |

|

Enhance efficiency and robustness in chrono-dose finding |

| 2. Integrate wearable-captured chronotype to stratify randomization and inform priors |

|

Personalize treatment timing based on individual circadian profiles |

| 3. Embed rolling interim analyses that drop unfavorable time windows rather than doses |

|

Optimize trial adaptation by focusing on optimal dosing windows |

| 4. Pilot such designs in drugs with known chronotoxicities, using point-of-care melatonin or cortisol assays as safety triggers |

|

Validate design feasibility and safety in chronotherapy-prone drugs |

| 5. Simulate Bayesian hierarchical designs co-randomizing dose level and dosing hour, borrowing strength across adjacent time bins |

|

Enhance efficiency and robustness in chrono-dose finding |

Table 8.

Critical Research Gaps in Translating Engineered Consortia for Multi-Drug Resistant Organisms Decolonization. This table highlights six principal gaps stalling the clinical translation of defined or engineered microbial consortia for decolonizing multidrug-resistant organisms (MDROs). Addressing these gaps requires standardized engraftment biomarkers, mechanistic phage–bacteria–host studies in gnotobiotic models, robust safety assessments of horizontal gene transfer, GMP-aligned manufacturing/QC, adaptive trial frameworks integrating antibiotics and diet rhythms, and harmonized regulatory pathways.

Table 8.

Critical Research Gaps in Translating Engineered Consortia for Multi-Drug Resistant Organisms Decolonization. This table highlights six principal gaps stalling the clinical translation of defined or engineered microbial consortia for decolonizing multidrug-resistant organisms (MDROs). Addressing these gaps requires standardized engraftment biomarkers, mechanistic phage–bacteria–host studies in gnotobiotic models, robust safety assessments of horizontal gene transfer, GMP-aligned manufacturing/QC, adaptive trial frameworks integrating antibiotics and diet rhythms, and harmonized regulatory pathways.

| Next Steps |

|

Purpose |

| 1. Unpredictable Engraftment and Lack of Comparative Trials |

|

Engraftment remains erratic (e.g., VE303 only after antibiotic conditioning; VE707’s murine efficacy lacks human PK analogues). No head-to-head studies versus FMT)exist, so key efficacy drivers (bacteriocins, phages, niche competition) are unclear. |

| 2. Scarce Durability and Mechanistic Data |

|

Longitudinal sequencing hints at phage-mediated suppression post-FMT, but detailed mechanistic dissection of phage–bacteria–host interactions over time is missing, leaving durability of decolonization unpredictable. |

| 3. Undercharacterized Safety and Horizontal Gene Transfer Risks |

|

Potential for engineered strains (e.g., E. coli secreting microcins) to acquire resistance cassettes in vivo is insufficiently studied, so safety profiles and mitigation strategies for HGT remain undefined.

|

| 4. Manufacturing and Quality Control Deficits |

|

Current frameworks lag pharmaceutical standards: multi- LBPs lack verified batch-to-batch consistency in metabolite outputs and stability, hindering reproducibility and scale-up. |

| 5. Absence of Adaptive Trial Designs Integrating Timing Factors |

|

Trials rarely modulate dosing relative to antibiotic schedules, feeding rhythms, or bile acid fluctuations, despite evidence these factors gate colonization resistance; person-alized timing algorithms remain unexplored. |

| 6. Fragmented Regulatory Pathways for Genetically Modified LBPs |

|

Regulatory requirements differ across jurisdictions for engineered or defined consortia, deterring investment and delaying standardization; clear, harmonized guidelines are needed to accelerate safe, predictable, and durable applications. |

Table 9.

Next Steps for kynurenic acid (KYNA) Encapsulation and Delivery Research. This table outlines the proposed experimental approaches for improving KYNA delivery systems, including stability testing, release profiling, triggered delivery, and bioavailability assessments in gnotobiotic models.

Table 9.

Next Steps for kynurenic acid (KYNA) Encapsulation and Delivery Research. This table outlines the proposed experimental approaches for improving KYNA delivery systems, including stability testing, release profiling, triggered delivery, and bioavailability assessments in gnotobiotic models.

| Next Steps |

|

Purpose |

| 1. Screen GRAS-grade polymers for KYNA compatibility under accelerated aging |

|

Identify stable encapsulation materials suitable for KYNA under storage conditions |

| 2. Map release profiles in simulated gastrointestinal fluids and pig colonic explants |

|

Characterize release dynamics in physiologically relevant gut environments |

| 3. Employ near-infrared–triggered nanocapsules to test on-demand bursts during inflammation |

|

Enable controlled KYNA release in response to inflammation using light-triggered mechanisms |

| 4. Quantify systemic versus luminal KYNA using LC-MS in gnotobiotic mice, benchmarking against Bifidobacterium-produced levels |

|

Evaluate bioavailability and distribution of KYNA compared to natural microbial production |

| 5. Screen GRAS-grade polymers for KYNA compatibility under accelerated aging |

|

Identify stable encapsulation materials suitable for KYNA under storage conditions |

Table 12.

Key Gaps in Chronotherapeutic Clinical Trial Methodologies. Summary of critical gaps hindering the integration of circadian biology into clinical trial designs, highlighting areas needing methodological innovation and validation for effective translational application.

Table 12.

Key Gaps in Chronotherapeutic Clinical Trial Methodologies. Summary of critical gaps hindering the integration of circadian biology into clinical trial designs, highlighting areas needing methodological innovation and validation for effective translational application.

| Key Gap Description |

|

Implication |

| 1. Adaptive randomization models that incorporate dosing clock time as a modifiable arm |

|

Enables dynamic optimization of treatment timing to enhance therapeutic efficacy and reduce toxicity |

| 2. Validated software bridges between CGM, lactate, or KYN sensors and electronic trial master files |

|

Facilitates seamless integration of real-time biomarker data into clinical trial records, improving data fidelity and regulatory compliance |

| 3. Safety rules for rapid dose time shifts in outpatient settings |

|

Ensures patient safety during temporal treatment adjustments, especially outside controlled environments |

| 4. Patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) sensitive to circadian toxicity |

|

Captures subjective patient experiences related to time-dependent side effects, enhancing the assessment of tolerability and quality of life |

Table 13.

Immediate Next Steps for KYNA-Targeted Pacing and Dosing Optimization. This table summarizes the next phase in developing precision KYNA-targeted dosing strategies, focusing on pharmacokinetic profiling, Bayesian algorithm calibration, and integration of patient-reported outcomes to improve therapeutic tolerability.

Table 13.

Immediate Next Steps for KYNA-Targeted Pacing and Dosing Optimization. This table summarizes the next phase in developing precision KYNA-targeted dosing strategies, focusing on pharmacokinetic profiling, Bayesian algorithm calibration, and integration of patient-reported outcomes to improve therapeutic tolerability.

| Immediate Next Steps |

|

Objective |

| 1. Run a crossover pharmacokinetic study comparing saliva, plasma, and tumor microdialysate KYNA after RY103 micro-dosing |

|

Evaluate the relationship between KYNA levels in different biological matrices post micro-dosing |

| 2. Calibrate the Bayesian control algorithm using simulated patient data |

|

Optimize the Bayesian algorithm for real-time adaptive control of dosing schedules |

| 3. Embed patient-reported fatigue and cognitive scores to test whether KYNA-targeted pacing improves tolerability compared to fixed BID regimens |

|

Assess the clinical benefit of KYNA-guided dosing on patient fatigue and cognitive outcomes relative to standard dosing practices |

Table 14.

Clues Supporting Feasibility of AI-Driven, Adaptive Gut–Brain Modulation. This table summarizes key lines of evidence that support the feasibility of integrating AI-driven therapeutic feedback loops with sensor-driven exercise platforms and probiotic modulation strategies, laying the groundwork for dynamic, real-time gut–brain axis interventions.

Table 14.

Clues Supporting Feasibility of AI-Driven, Adaptive Gut–Brain Modulation. This table summarizes key lines of evidence that support the feasibility of integrating AI-driven therapeutic feedback loops with sensor-driven exercise platforms and probiotic modulation strategies, laying the groundwork for dynamic, real-time gut–brain axis interventions.

| Clues Supporting Feasibility |

|

Objective |

| 1. Clinical artificial intelligence operations (ClinAIOps) frameworks for continuous therapeutic monitoring in hypertension and diabetes |

|

Demonstrate the capability of AI frameworks to adaptively manage complex biological feedback loops |

| 2. Kinect- or sensor-driven treadmills that auto-adjust speed based on user position |

|

Validate the use of real-time biomechanical data to modulate physical activity interventions |

| 3. Murine and human studies showing tailored probiotic blends reduce intestinal inflammation and modulate TRP metabolism |

|

Provide proof of principle that microbiome-based therapies can influence gut–brain biochemical pathways |