1. Introduction

The development of inactivated polio vaccines based on Sabin strains was the most significant achievement in the 70-year history of poliomyelitis vaccines after the introduction of wild strains inactivated and Sabin strains attenuated vaccines [

1]. The primary goal of attenuation strategies is to reduce virulence and maintain high immunogenicity in the resulting viral vaccine particles. The development of vaccine-associated paralytic polio as a side effect of oral Sabin polio attenuated vaccine limits their use and reduces their effectiveness [

2]. Despite this, its widespread use in the 1960s - 2000s led to a significant decrease in the incidence of paralytic poliomyelitis worldwide and the victory over the circulation of wild strains of poliovirus types 2 and 3 [

3].

The World Health Organization’s Global Polio Eradication Initiative encourages vaccine manufacturers to use Sabin strains to develop and produce inactivated vaccines to minimize the risk of spreading wild strains [

4].

Inactivating agents must destroy viral structural, immunogenically unimportant proteins or the viral genome to prevent infection of cells by a virus and/or completely destroy its ability to replicate in infected cells [

5].

Formaldehyde [

6] or beta-propiolactone [

7] can be used for chemical inactivation of poliovirus Sabin strains. Formaldehyde is used in the current production of inactivated polio vaccines [

1]. The use of formaldehyde is known to alter the antigenic epitopes of the virus [

5]. Also, both chemical agents are toxic, so that, the chemical agent should be removed and/or converted into a nontoxic before the formulation of final vaccine formulation [

8].Therefore, alternative methods of virus inactivation are being developed, and radiation technologies can provide destruction of the viral genome (RNA in poliovirus) and maintain high immunogenicity by preserving the protein antigen (D-antigen in poliovirus) [

9]. Inactivation of Sabin poliovirus strains with accelerated electrons is attractable because of low requirements to infrastructure in comparison to gamma or ultraviolet irradiation technologies [

7,

9]. Poliovirus genomic RNA is sensitive to radiation damage because it exists in a single copy [

10], and the breaks in its chain stop replication. The proteins of immunogenic D-antigen are more resistant to accelerated electrons due to their high molecular mass, high number of weak van der Waals bonds and the number of copies in a viral unit [

11,

12].

Analyzing of viral genome integrity after inactivation is routinely performed by quantitative polymerase-chain reaction (qPCR) [

13,

14,

15]. The cycle threshold (Ct) of qPCR is defined as the number of amplification cycles required for the accumulated fluorescence (resulting from amplification of target DNA) to reach a threshold value above background. Ct values are therefore inversely proportional to the stability of the viral genome; low Ct values indicate genome integrity and high Ct values indicate a high degree of viral genome degradation [

16]. The main limitation of qPCR is its ability to give reliable results only with short amplicons in the range of 150 - 500 base pairs [

17]. The size of the genome of different viruses varies from 2,000 nucleotides to 1.2 million bases [

18] and in most studies there is no argument to explain the choice of site for amplification to detect genome breakdown after inactivation [

13,

14,

15].

Many important processes in living cells (organisms) involve electrons as donors or acceptors [

19,

20]. Electroanalysis allows the registration of nucleotide molecular profiles (after isolation of DNA, RNA from biosamples) by electrooxidation of heterocyclic bases [

21], which makes it possible to perform comparative analysis relative to the control (intact sample) and to evaluate the mechanism of interaction of various chemical compounds with nucleotides [

22,

23,

24,

25], as well as to analyze DNA or RNA decomposition. Previously, we developed the label-free approach based on differential pulse voltammetry (DPV) technique for the direct detection of DNA fragmentation and degradation after exposure to restriction enzymes and during apoptosis [

26].

In this study, we have shown that different sites of poliovirus RNA have a different dependence of Ct on the dose of accelerated electron irradiation. The degradation of viral genome was also analyzed by electrochemical approach. These results are necessary to confirm genome decomposition in viral particles after inactivation for antiviral vaccine development purposes.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Poliomyelitis Virus Propagation

Poliovirus of the Sabin strain type 2 was propagated in Vero cells (WHO 10-87). Vero cells were grown in a 50-liter bioreactor XDR-50 (Cytiva, Marlborough, MT) using the LXMC-dex1 microcarrier 3 g/L, (SunResin, Shaanxi, China) in the MEM (Institute of Poliomyelitis, Moscow, Russia) containing 5% fetal serum (LTBiotech, Vilnius, Lithuania). Cultivation settings: temperature - 37°C, pH control - 7.3±0.1; DO (dissolved oxygen) control - 70%, stirring speed - 40 rpm. Before infection, the suspension of microcarriers with cells was washed with Hanks’ solution (Institute of Poliomyelitis, Moscow, Russia) and the nutrient medium was changed to M199 (Institute of Poliomyelitis, Moscow, Russia). Cells were infected with a multiplicity of infection of 0.01 - 0.05 TCID/cell after reaching a cell concentration of 1-2*10

6 cells/mL. Infected cells were incubated at 34°C for 2 days (or until the monolayer of cells on the microcarriers degrades). Viral suspension was clarified by filtration through PES-filter cascade: 0.65/0.45-0.22 µm and concentrated at Sartoflow Advanced tangential flow filtration system with 100 kDa PES cassettes. Virus titer was measured via 50% tissue culture infectious dose) assay [

27] using Hep-2 cells. For the experiments, a virus suspension with a concentration of 10

10 TCID

50 was used.

2.2. Inactivation by Electron Beam Irradiation or Chemicals

Inactivation of Sabin 2 polioviruses was performed by accelerated electron beam irradiation at doses 5, 10, 15, or 25 kGy. The power accelerator was 15 kW and the energy of electrons was 10 mEV. Samples with viral material were packed by 4 ml into 5 ml cryotubes (three tubes for each inactivation condition) and placed hermetically sealed containers. The samples were initially precooled and irradiated at temperatures 25ºC, 2-8ºC, -20ºC or -70ºC. Control samples were not irradiated and stored at the same temperatures. Actual absorbed doses were determined by absorbed dose detector SO PD (F) R-5/50 (VNIIFTRI, Solnechnogorsk, Russia).

To inactivate viruses by formaldehyde, the pool of virus-containing fractions after chromatographic purification was diluted in a 2:1 ratio with 199 medium, a 37% formalin solution was added to a final concentration of 0.025% (v/v), mixed, filtered through a Millipore membrane (Merch-Millipore, Kenilworth, NJ) with a pore diameter of 0.22 microns (for sterilization and removal of viral aggregates). Inactivation was performed at a temperature of 37 ± 1 °C for 13 days. The neutralization of formaldehyde was carried out using sodium sulfite (Na2SO3).

To inactivate viruses by beta-propiolactone, the suspension containing the poliovirus was inactivated by beta-propiolactone with a final concentration of 0.2% (v/v). After the addition of beta-propiolactone, the contents were mixed and transferred to fresh sterile containers to remove the virus that had not reacted with beta-propiolactone. The mixture was kept for 24 hours at 4 °C and then incubated at 37 ° C for three hours. Beta-propiolactone was neutralized by the same method as for formaldehyde [

28].

2.3. Quantitative Polymerase-Chain Reaction (qPCR)

Viral RNA was isolated from inactivated or control samples using the Qiuck-RNA Viral Kit (Zymo Research, Seattle, WA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The concentration of isolated RNA was determined using the Qubit RNA HS Assay Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA) with the Qubit 4 Fluorometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA). The integrity and quality of RNA was determined using the Qubit RNA IQ Assay Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA). Isolated RNA was visualized by electrophoresis in 1 % agarose gel, stained with ethidium bromide and photographed under UV-light. Five micrograms of viral RNA was subjected to reverse transcription using MMLV RT kit (Evrogen, Moscow, Russia) in 25 µL reaction mixture. Hexamer random primer was used for initiation of transcription. The viral genome was segmented to 20 regions to get amplification segments not longer than 500 из (see

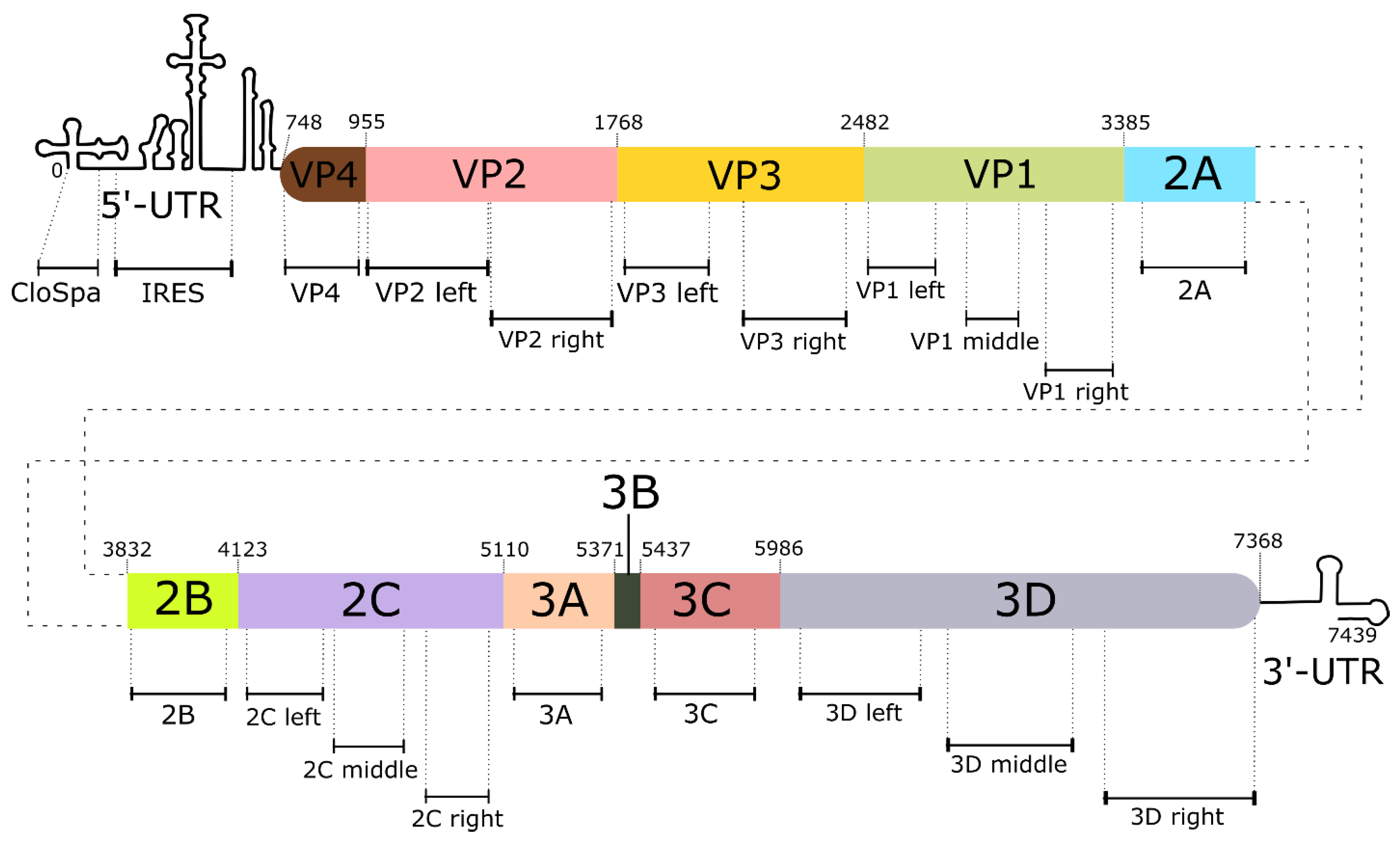

Table 1S in the Supplementary file). The location of PCR segments on the viral genome is shown on

Figure 1 Primers listed in

Table 1 were used for qPCR of each segment. Real-time PCR detection was performed in 20 µL mix-HS SYBR (Evrogen, Moscow, Russia) using the DTprime5 machine and software (DNA Technology, Protvino, Russia). The Ct of detection was defined for each sample as the number of amplification cycles required for the accumulated fluorescence to reach a threshold value above background. The Ct of each sample was measured in triplicate.

2.4. Electrochemical Study

Electrochemical measurements were performed at room temperature in 60 μL of 0.1 M potassium phosphate buffered saline (PBS) containing 50 mM NaCl (pH 7.4) using a PalmSens potentiostat (PalmSens BV, Houten, The Netherlands) with PSTrace software (version 5.8). The following DPV parameters for direct electrochemical oxidation of RNA were used: potential range 0.2-1.2 V, pulse amplitude 0.025 V, potential step 0.005 V, pulse duration 50 ms and scan rate 0.05 V/s. The screen-printed electrodes (SPE, ColorElectronics, Moscow, Russia) with graphite working electrode were modified by 2 μL (0.75±0.05 mg/mL) water dispersion of 0.4% single-wall carbon nanotubes (SWCNT TUBALL BATT H2O, OCSiAl, Novosibirsk, Russia). The SPE/SWCNT electrodes were kept at room temperature until completely dry. All other chemicals were analytical grade and purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Modified electrodes were pre-treated three times by DPV in PBS, pH 7.4. Two microlitres of the RNA probe was dropped onto the surface of the modified electrode and incubated for 24 h at +4°C before measurements. All potentials were referenced to the Ag/AgCl reference electrode. PSTrace with baseline correction was used to process the signal intensity values. All electrochemical data presented are the mean of three experiments with standard deviation.

2.5. Statistics

The graph of Ct versus dose was plotted and the coefficient of determination (R2) was calculated using Graph Prism 8 software (GraphPad Software, Inc. Boston, MA). Results are presented as mean ± standard deviation. R2 value higher than 0.7 was considered significant.

3. Results

3.1. Quality of RNA Isolated from Inactivated Virus

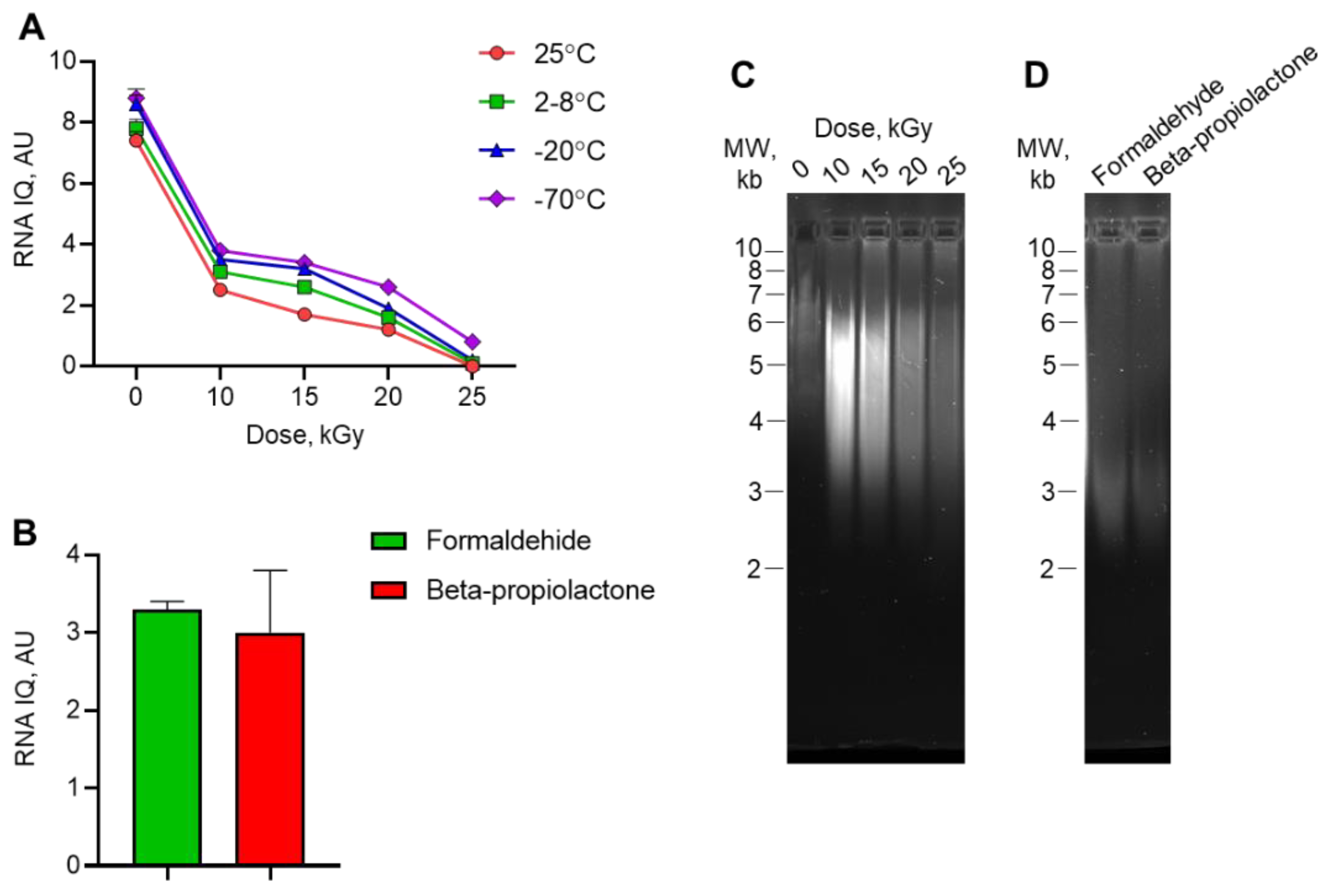

We studied the integrity and quality of the isolated viral RNA by fluorescently labeling the large and small RNAs. A number between 1 and 10 represents the percentage of large RNA molecules in the sample. We observed a gradual decrease in IQ values in samples irradiated with accelerated electron doses. (

Figure 2A). The IQ of the non-irradiated control samples was 7.4 – 8.8 AU, indicating a high degree of RNA integrity. This value dramatically decreased to 0 – 0.8 AU in 25 kGy irradiated samples, indicating complete RNA degradation. In general, the IQ values of samples irradiated at -20°C or -70°C were higher than those of samples irradiated at 25°C or 2-8°C, indicating that the viral genome is more stable in frozen samples when exposed to electron beam irradiation. The IQ values of samples inactivated by formaldehyde or beta-propiolactone did not exceed 4 AU (

Figure 2B). Agarose gel electrophoresis of total RNA isolated from irradiated viral samples (

Figure 2С) confirmed that the genome was degraded by irradiation. The main RNA bend from the control, non-irradiated sample was located at the top of the gel, within the 7 kb molecular weight marker area. After irradiation with 10 kGy, the size of the main bend decreased to 5 kb. Subsequent irradiation with increased doses of radiation resulted in the complete loss of full-size RNA. The RNA bends from samples inactivated with formaldehyde or beta-propiolactone located near the 3 kb molecular weight marker (

Figure 2D).

D Left Segment of Poliovirus Most Sensitive to Accelerated Electrons

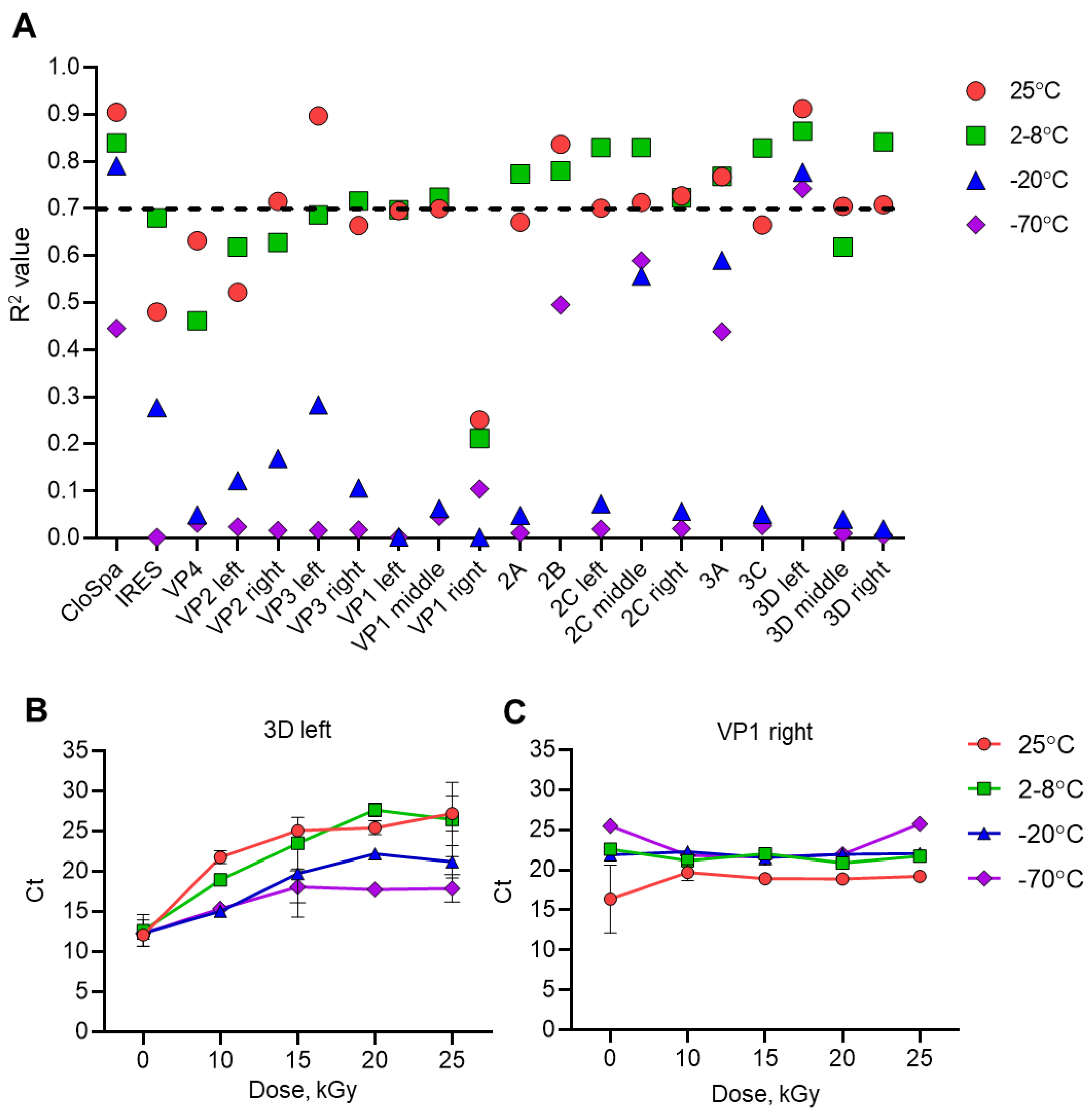

Values of Ct are inversely proportional to the stability of the viral genome [

16]. Using qPCR, we determined Ct values for each viral genome segment in samples irradiated at different doses and temperatures. R

2 values for the dose-dependency of Ct showed that decreasing sample temperature was associated with increased stability or integrity of viral RNA. The highest R

2 values were observed for samples irradiated at 25ºC or 2-8ºC (

Figure 3A). The mean R

2 values among all samples were 0.693 and 0.706 respectively. The lowest R

2 values were for samples frozen at -20ºC (mean 0.243) and -70ºC (mean 0.153).

Low Ct values indicate genome integrity and high Ct values indicate a high degree of viral genome decomposition. Only the 3D left segment of the viral RNA reached R

2 value higher than 0.7 at all temperatures (

Figure 3 A and B). The highest R

2 values of 0.912 and 0.864 were observed for this segment in samples irradiated at 25ºC or 2-8ºC. Viral segment VP 1 right (

Figure 3 A and C) showed the lowest R

2 values: even for temperature 25ºC it was at an insignificant value of 0.251.

The results of this experiment showed that the 3D left segment of the viral genome is the most representative for studying the effect of accelerated electrons on genome degradation, while the VP1 left segment is the least representative.

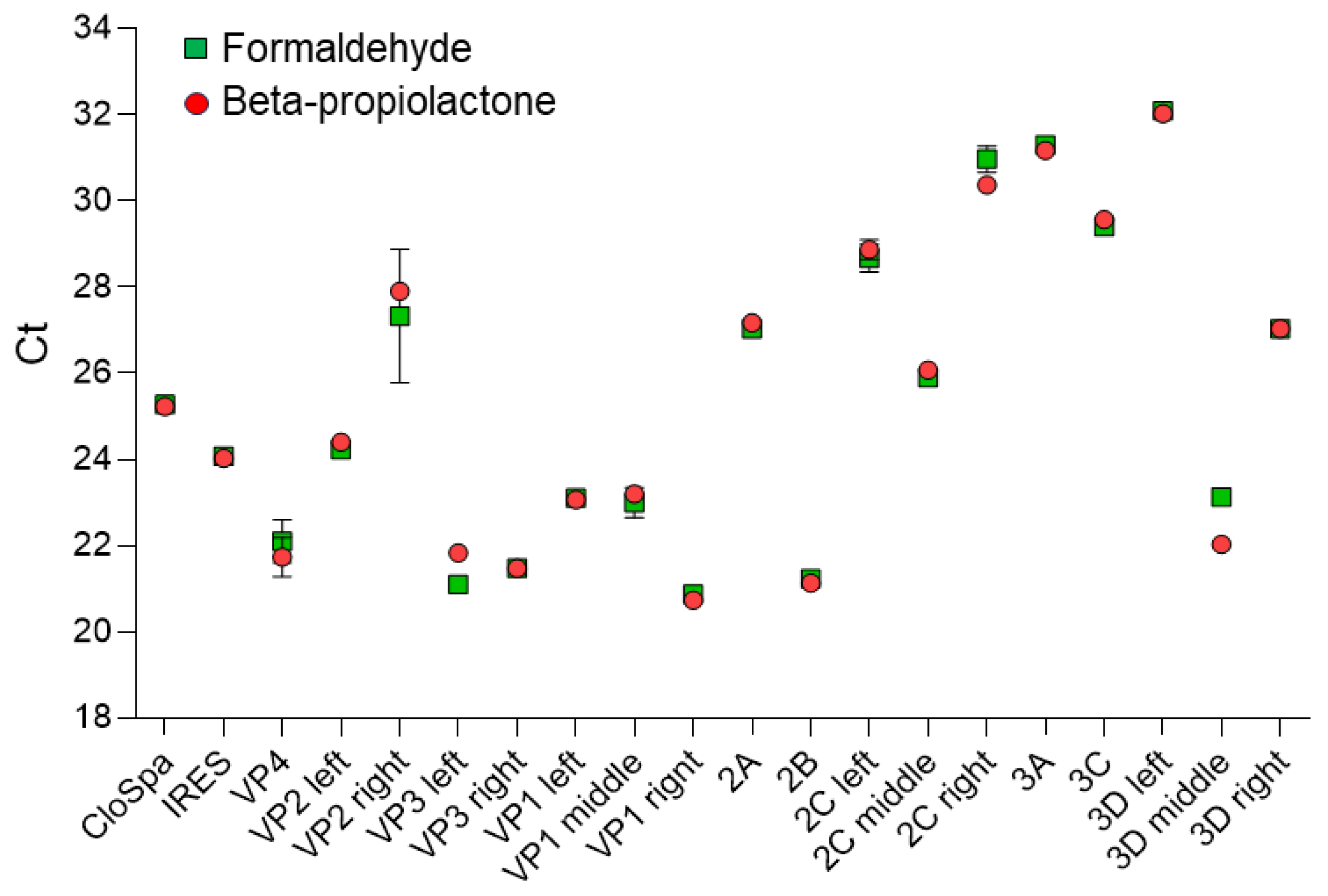

We determined Ct for each poliovirus genome segment after inactivation with the commonly used chemical reagents formaldehyde or beta-propiolactone (

Figure 4). Very good agreement between Ct values was observed for samples treated with each of these reagents. Again, the left 3D segment showed the highest Ct values of 32.10 ± 0.10 for formaldehyde and 32.03 ± 0.15 for beta-propiolactone treated samples demonstrating the high sensitivity of this segment to inactivating chemicals. The VP1 right segment showed the lowest Ct values of 20.87±0.06 for formaldehyde and 20.87±0.15 for beta-propiolactone treated samples. Low Ct values again indicate the highest resistance of this segment to degradation.

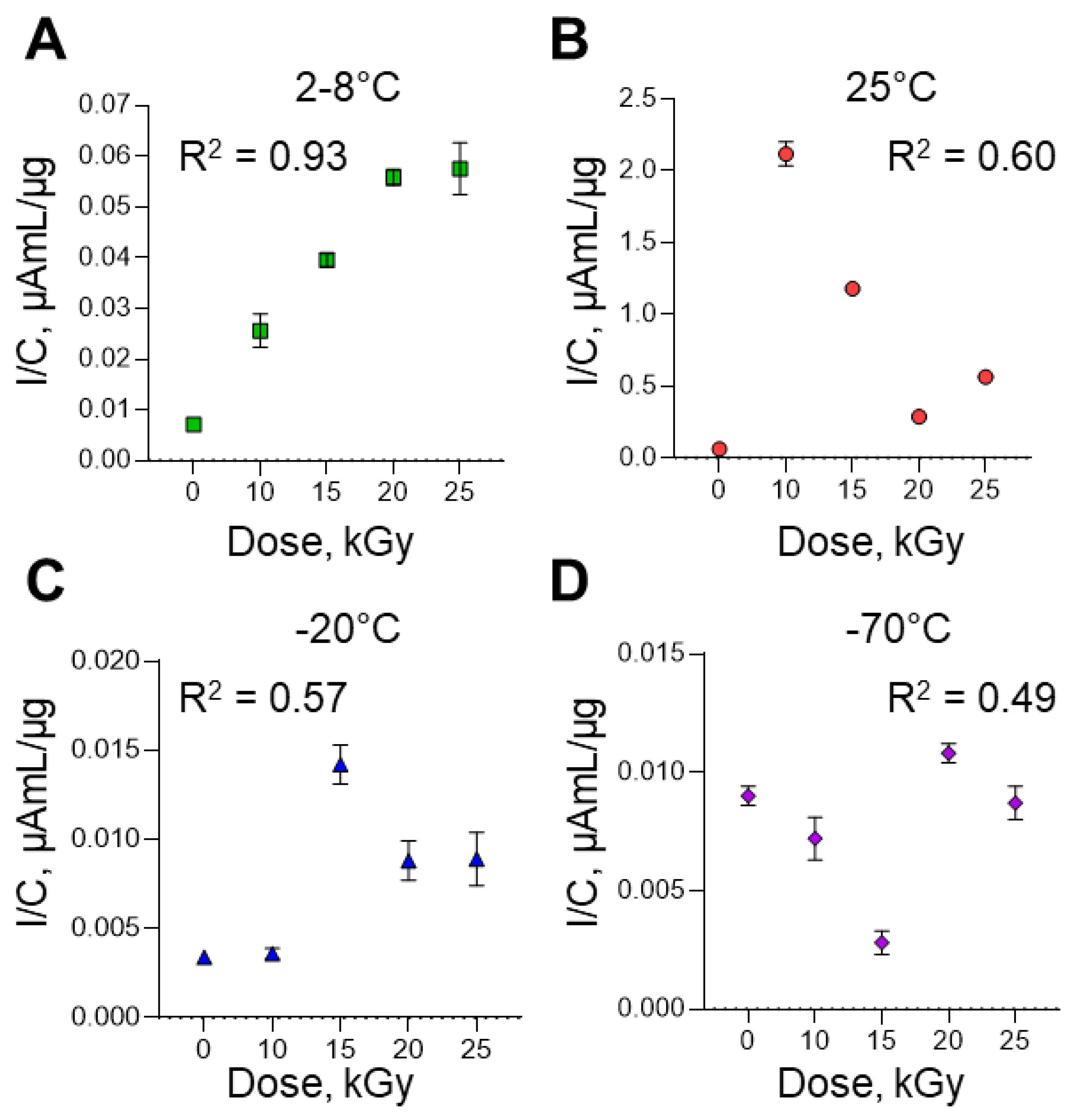

3.4. Electroanalysis of Poliovirus RNA Degradation on SPE/SWCNT

Electrochemical profiling of RNA isolated from samples of Sabin 2 strain of poliovirus before and after inactivation by accelerated electrons was carried out. Nucleotide molecular fingerprints were obtained by differential pulse voltammetry. Two oxidation peaks at potentials of +0.49±0.01 V (with shoulder at +0.60±0.01 V) and +0.82±0.01 V corresponding to electrooxidation of RNA nucleobases guanine and adenine, respectively were registered (see

Figure 2S in the Supplementary file). The electrooxidation peak at potential +0.49±0.01 V is not uniform and composite. It is possible to assume that the wave with a broad shoulder corresponds not only guanine, but also represents the oxidation of proteins that may form a complex with virus RNA (ribonucleoproteins or covalently bound protein VPg) [

29] or the RNA fragments of different length with different guanine exposure and, respectively, different guanine availability for electrochemical oxidation. For a quantitative comparison of the electrooxidation peak current (I) at a potential of +0.49±0.01 V, which revealed the most intense response, this experimental parameter was normalized by the RNA concentration (C) in the samples, I/C (

Figure 5). As shown on

Figure 5 A-D, the increase in the irradiation dose was accompanied by an increase in the signals of RNA electrooxidation (R

2 from 0.49 to 0.93). The highest R

2 values were observed for samples irradiated at 2-8ºC (

Figure 5 A). The peak current of guanine electrooxidation (

Figure 5 A) increases eightfold when the RNA is irradiated (irradiation dose 25 kGy, 2-8°C) and compared to the control native RNA. We assume, that an increase of peak current intensity is a result of strand viral RNA fragmentation or complete dispruption during irradiation procedure [

30,

31].

The data obtained suggest that the increase of RNA electrooxidation signals with increasing irradiation dose is associated with damage of the RNA structure. The results obtained are consistent with the qPCR results for these samples and the results of gel electophoresis.

4. Discussion

Genome decomposition ensures the inactivation of viruses during the development and production of vaccines based on attenuated viruses. Fine-tuning the type of irradiation, dose, and regimen, such as energy and temperature, can result in the selective decomposition of viral nucleic acids. According to the radiation target theory, viral genomes are more susceptible to structural damage by electron beam irradiation than viral proteins due to their higher molecular weight [

32]. Based on these data, viral RNA was chosen as experimental target for analysis of polio virus Sabin 2 genome degradation.

The results of this study demonstrated three approaches that can be applied to analyze viral genome decomposition after irradiation of inactivation by chemicals. This study demonstrated three approaches for analyzing viral genome decomposition after chemical inactivation or irradiation. The first approach is based on measuring RNA fluorescence in treated samples using a commercially available kit that detects the proportion of integrated and decomposed RNA in a sample. (

Figure 2 A and B). As expected, the integrity (i.e., IQ value) decreased upon irradiation with accelerated electrons. These results were consistent with the electrophoretic visualization of degraded RNA, which showed a decrease in the size of RNA bends after irradiation (

Figure 2 С and D). It should be noted that IQ values also depended on sample temperature: lower temperatures corresponded to higher IQ in samples irradiated with the same doses. These results could be explained by the ability of accelerated electrons to disrupt nucleic acids through direct impact, which induces strain breaks, or indirectly, by inducing reactive oxygen species during water radiolysis [

33]. Radiolysis decreases at lower temperatures, which leads to a decrease in genome decomposition rates. In our experiments, the dose of accelerated electrons had a greater effect on genome decomposition than temperature did.

The second approach demonstrated in this study is the possibility to determine RNA integrity by qPCR of its different segments. PCR is a frequently used technique for demonstrating genome disintegration upon virus inactivation [

13,

14,

15]. However, as our work shows, the choice of the genome segment to be amplified is of primary importance for obtaining valid results (

Figure 3 and 4). We have demonstrated that certain regions of the genome are more stable for irradiation, while others are highly susceptible to degradation. Up to date we still do not have reasonable explanation why different Sabin 2 genome segments have different resistance for degradation. Some structural features of RNA folding within viral particles may be significant in exposing the 3D left segment and hiding the VP1 right segment from accelerated electrons and/or products of water radiolysis.

The relative resistance of certain fragments of the genome (for example, VP1right) to irradiation with accelerated electrons, as well as chemical methods of inactivation, can theoretically be explained by the possible interaction of these regions with capsid proteins inside the particle. A closely located protein shell can “shield” and non-specifically protect a region of the genome from chemical or physical effects. However, to date, specific fragments of the poliovirus genome that participate in binding to capsid proteins and are responsible for packaging of genomic RNA have not been identified [

34]. Moreover, the packaging process is apparently primarily associated with the replication process and is possibly triggered by protein-protein interactions (for example, between capsid proteins and the replication protein 2CATPase) [

35]. But this fact does not negate the fact that individual fragments of the genome have a higher affinity for the inner part of the capsid, while others have a lower affinity. Perhaps our data are an indirect indication of the involvement of more stable fragments in the genome-capsid interaction.

Traditional laboratory-based nucleic acids assays possess many shortcomings and are time-consuming, labor-intensive and need additional expensive chemical and biochemical reagents and modern complicated equipment [

29]. Electrochemical DNA/RNA biosensors have drawn attention due to their obvious advantages such as high sensitivity, portability, cost-effectiveness, fast response time, and compatibility with miniaturized detection technologies and compact equipment with user-friendly software [

36,

37]. The DPV method using carbon nanotube-modified electrodes was developed to study the effect of electron beam irradiation potency on the damage of viral genome RNA. The third approach used in our study involved the comparative electrochemical profiling of RNA isolated from intact and irradiated viruses. The electrochemical profiles have reflected the extent of RNA damage depending on the dose of accelerated electron irradiation and temperature regime of experiments (

Figure 5). The increase of RNA peak current intensity due to electrooxidation signals with increasing irradiation dose is associated with damage of viral RNA structure, due to greater availability of heterocyclic bases to electrochemical reactions at the electrode [

30,

31]. The differential pulse voltammetry approach confirmed the quantitative PCR (qPCR) results for the degradation of the polio virus Sabin genome after electron beam irradiation at an experimental temperature of 2-8ºC and an irradiation dose of 20-25 kGy. In our experimental assay, we demonstrated that electrochemical label-free biosensors proved the concept of viral genome degradation, as registered by the IQ assay and qPCR.

In conclusion, this study demonstrated that irradiation of Sabin 2 poliovirus by accelerated electrons leads to the degradation of viral genome segments on different rate. Some segments (primary 3D left segment) are rather sensitive while some are resistant (primary VP1 right segment). Some segments, such as 3D left segment, are rather sensitive, while others, such as VP1 right segment, are resistant. This indicates that the accelerated electron impact process on RNA is uneven, and the most representative segment for the qPCR study must be selected for each virus before studying virus inactivation.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on

Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.D.Z.; investigation, D.D.Z., A.N.S., Y.Y.I., A.A.K, A.N.P., I.V.L., S.V.B., O.A.S., R.S.C., L.E.A., A.V.B., V.V.S., A.A.I.; discussion of experimental results, D.D.Z., Y.Y.I., L.E.A.; writing—original draft preparation, D.D.Z., Y.Y.I., L.E.A.; writing—review and editing, D.D.Z.; visualization, Y.Y.I.; project administration, D.D.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The research was supported by the Russian Science Foundation project No. 23-15-00471.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Piniaeva, A.; Ignatyev, G.; Kozlovskaya, L.; Ivin, Y.; Kovpak, A.; Ivanov, A.; Shishova, A.; Antonova, L.; Khapchaev, Y.; Feldblium, I.; et al. Immunogenicity and Safety of Inactivated Sabin-Strain Polio Vaccine “PoliovacSin”: Clinical Trials Phase I and II. Vaccines 2021, 9, 565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowdle, W.R.; De Gourville, E.; Kew, O.M.; Pallansch, M.A.; Wood, D.J. Polio eradication: the OPV paradox. Rev. Med. Virol. 2003, 13, 277–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polio Eradication Strategy 2022–2026: Executive summary. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2021. Licence CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO. 2021.

- Bakker, W.A.M.; Thomassen, Y.E.; van’t Oever, A.G.; Westdijk, J.; van Oijen, M.G.C.T.; Sundermann, L.C.; van’t Veld, P.; Sleeman, E.; van Nimwegen, F.W.; Hamidi, A.; et al. Inactivated polio vaccine development for technology transfer using attenuated Sabin poliovirus strains to shift from Salk-IPV to Sabin-IPV. Vaccine 2011, 29, 7188–7196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanders, B.; Koldijk, M.; Schuitemaker, H. Inactivated Viral Vaccines. Vaccine Anal. Strateg. Princ. Control 2014, 45–80. [Google Scholar]

- Wilton, T.; Dunn, G.; Eastwood, D.; Minor, P.D.; Martin, J. Effect of Formaldehyde Inactivation on Poliovirus. J. Virol. 2014, 88, 11955–11964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhdanov, D.D.; Ivin, Y.Y.; Shishparenok, A.N.; Kraevskiy, S. V; Kanashenko, S.L.; Agafonova, L.E.; Shumyantseva, V. V; Gnedenko, O. V; Pinyaeva, A.N.; Kovpak, A.A.; et al. Perspectives for the creation of a new type of vaccine preparations based on pseudovirus particles using polio vaccine as an example. Biomed. Khim. 2023, 69, 253–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabbaghi, A.; Miri, S.M.; Keshavarz, M.; Zargar, M.; Ghaemi, A. Inactivation methods for whole influenza vaccine production. Rev. Med. Virol. 2019, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, H.S. Application of radiation technology in vaccines development. Clin. Exp. Vaccine Res. 2015, 4, 145–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quarleri, J. Poliomyelitis is a current challenge: long-term sequelae and circulating vaccine-derived poliovirus. GeroScience 2023, 45, 707–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahar, M.W.; Porta, C.; Fox, H.; Macadam, A.J.; Fry, E.E.; Stuart, D.I. Mammalian expression of virus-like particles as a proof of principle for next generation polio vaccines. NPJ vaccines 2021, 6, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lentz, K.N.; Smith, A.D.; Geisler, S.C.; Cox, S.; Buontempo, P.; Skelton, A.; DeMartino, J.; Rozhon, E.; Schwartz, J.; Girijavallabhan, V.; et al. Structure of poliovirus type 2 Lansing complexed with antiviral agent SCH48973: comparison of the structural and biological properties of the three poliovirus serotypes. Structure 1997, 5, 961–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, Z.; Kwee, E.J.; Cleveland, M.H.; Cole, K.D.; Lin-Gibson, S.; He, H.-J. Quantitation and integrity evaluation of RNA genome in lentiviral vectors by direct reverse transcription-droplet digital PCR (direct RT-ddPCR). Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 14470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wurtzer, S.; Duvivier, M.; Accrombessi, H.; Levert, M.; Richard, E.; Moulin, L. Assessing RNA integrity by digital RT-PCR: Influence of extraction, storage, and matrices. Biol. methods Protoc. 2024, 9, bpae053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burton, J.; Love, H.; Richards, K.; Burton, C.; Summers, S.; Pitman, J.; Easterbrook, L.; Davies, K.; Spencer, P.; Killip, M.; et al. The effect of heat-treatment on SARS-CoV-2 viability and detection. J. Virol. Methods 2021, 290, 114087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabat, J.; Subhadra, S.; Rath, S.; Ho, L.M.; Kanungo, S.; Panda, S.; Mandal, M.C.; Dash, S.; Pati, S.; Turuk, J. Yielding quality viral RNA by using two different chemistries: a comparative performance study. Biotechniques 2021, 71, 510–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Holm, W.; Ghesquière, J.; Boon, N.; Verspecht, T.; Bernaerts, K.; Zayed, N.; Chatzigiannidou, I.; Teughels, W. A Viability Quantitative PCR Dilemma: Are Longer Amplicons Better? Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2021, 87, e0265320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogata, H.; Claverie, J.-M. Unique genes in giant viruses: regular substitution pattern and anomalously short size. Genome Res. 2007, 17, 1353–1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shumyantseva, V. V.; Agafonova, L.E.; Bulko, T. V.; Kuzikov, A. V.; Masamrekh, R.A.; Yuan, J.; Pergushov, D. V.; Sigolaeva, L. V. Electroanalysis of Biomolecules: Rational Selection of Sensor Construction. Biochem. 2021, 86, S140–S151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shumyantseva, V. V; Koroleva, P.I.; Bulko, T. V; Agafonova, L.E. Alternative Electron Sources for Cytochrome P450s Catalytic Cycle: Biosensing and Biosynthetic Application. Processes 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paleček, E.; Bartošík, M. Electrochemistry of nucleic acids. Chem. Rev. 2012, 112, 3427–3481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shumyantseva, V. V; Pronina, V. V; Bulko, T. V; Agafonova, L.E. Electroanalysis in Pharmacogenomic Studies: Mechanisms of Drug Interaction with DNA. Biochemistry. (Mosc). 2024, 89, S224–S233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agafonova, L.; Tikhonova, E.; Sanzhakov, M.; Kostryukova, L.; Shumyantseva, V. Electrochemical Studies of the Interaction of Phospholipid Nanoparticles with dsDNA. Processes 2022, 10, 2324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shumyantseva, V. V; Bulko, T. V; Agafonova, L.E.; Pronina, V. V; Kostryukova, L. V Comparative Analysis of the Interaction between the Antiviral Drug Umifenovir and Umifenovir Encapsulated in Phospholipids Micelles (Nanosome/Umifenovir) with dsDNA as a Model for Pharmacogenomic Analysis by Electrochemical Methods. Processes 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shumyantseva, V. V; Berezhnova, A. V; Agafonova, L.E.; Bulko, T. V; Veselovsky, A. V Electrochemical Analysis of the Interaction between DNA and Abiraterone D4A Metabolite. J. Anal. Chem. 2024, 79, 873–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agafonova L.E.; Zhdanov D.D.; Gladilina Yu.A.; Shisparenok A.N.; Shumyantseva V.V. Electrochemical approach for the analysis of DNA degradation in native DNA and apoptotic cells. HELIYON-D-23-46903 2023.

- Thomassen, Y.E.; Welle, J.; van Eikenhorst, G.; van der Pol, L.A.; Bakker, W.A.M. Transfer of an adherent Vero cell culture method between two different rocking motion type bioreactors with respect to cell growth and metabolic rates. Process Biochem. 2012, 47, 288–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S.D.; Pye, D.; Cox, J.C. Inactivation of poliovirus with beta-propiolactone. J. Biol. Stand. 1986, 14, 103–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozer, T.; Geiss, B.J.; Henry, C.S. Review-Chemical and Biological Sensors for Viral Detection. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2020, 167, 37523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stempkowska, I.; Ligaj, M.; Jasnowska, J.; Langer, J.; Filipiak, M. Electrochemical response of oligonucleotides on carbon paste electrode. Bioelectrochemistry 2007, 70, 488–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brabec, V.; Koudelka, J. Oxidation of deoxyribonucleic acid at carbon electrodes. The effect of the quality of the deoxyribonucleic acid sample. J. Electroanal. Chem. Interfacial Electrochem. 1980, 116, 793–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grieb, T.; Forng, R.-Y.; Brown, R.; Owolabi, T.; Maddox, E.; Mcbain, A.; Drohan, W.N.; Mann, D.M.; Burgess, W.H. Effective use of Gamma Irradiation for Pathogen Inactivation of Monoclonal Antibody Preparations. Biologicals 2002, 30, 207–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranawat, P.; Rawat, S. Radiation resistance in thermophiles: mechanisms and applications. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2017, 33, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comas-Garcia, M. Packaging of Genomic RNA in Positive-Sense Single-Stranded RNA Viruses: A Complex Story. Viruses 2019, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, Y.; Gorbatsevych, O.; Liu, Y.; Mugavero, J.; Shen, S.H.; Ward, C.B.; Asare, E.; Jiang, P.; Paul, A. V; Mueller, S.; et al. Limits of variation, specific infectivity, and genome packaging of massively recoded poliovirus genomes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2017, 114, E8731–E8740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, A.G.; Brickner, H.; Looney, D.; Hall, D.A.; Aronoff-Spencer, E. Clinical detection of Hepatitis C viral infection by yeast-secreted HCV-core:Gold-binding-peptide. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2018, 119, 230–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sha, Z.; Xu, J.; Wang, Y.; Ma, L.; Li, X.; Chen, Y.; Gu, H.-Y. Direct electrochemistry & enzyme characterization of fresh tobacco RNA. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2023, 931, 117156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).