Submitted:

09 June 2025

Posted:

11 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. A Functional Overview of Translation and tRNA Binding Sites

1.2. Molecular Insights into AUG Recognition During Translation Initiation

1.3. Mechanisms Contributing to the Inactivation of the AUG Codon as a Translation Initiation Site

1.3.1. Inadequate Kozak Sequence Context

- If these positions are mutated (e.g., A→U at -3), the recognition efficiency of AUG drops significantly.

- As a result, ribosomes may bypass this AUG and continue scanning for an alternative downstream AUG within a stronger context.

1.3.2. Leaky Scanning Phenomenon

- This mechanism allows the generation of multiple protein isoforms from a single mRNA.

- The frequency of leaky scanning can be modulated by translation initiation factors like eIF1 and eIF1A.

1.3.3. Phosphorylation of eIF2α Under Cellular Stress Conditions

- Phosphorylated eIF2α sequesters the guanine nucleotide exchange factor eIF2B, reducing the recycling of eIF2-GDP to eIF2-GTP.

- This results in a global decrease in translation initiation from AUG codons.

- Some transcripts escape this repression through alternative translation initiation mechanisms.

1.3.4. RNA Secondary Structures in the 5' UTR

- Structures with a high thermodynamic stability (ΔG < -30 kcal/mol) near the 5′ cap or close to the AUG can inhibit initiation.

- eIF4A, an RNA helicase, is often required to resolve these structures to allow proper scanning.

1.3.5. microRNA- and RBP-Mediated Repression of AUG Recognition

- miRNAs often recruit the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC) to block initiation.

- RBPs like TIA-1 or HuR can bind and remodel RNA conformation or directly compete with translation machinery.

1.3.6. Utilization of Non-AUG Start Codons

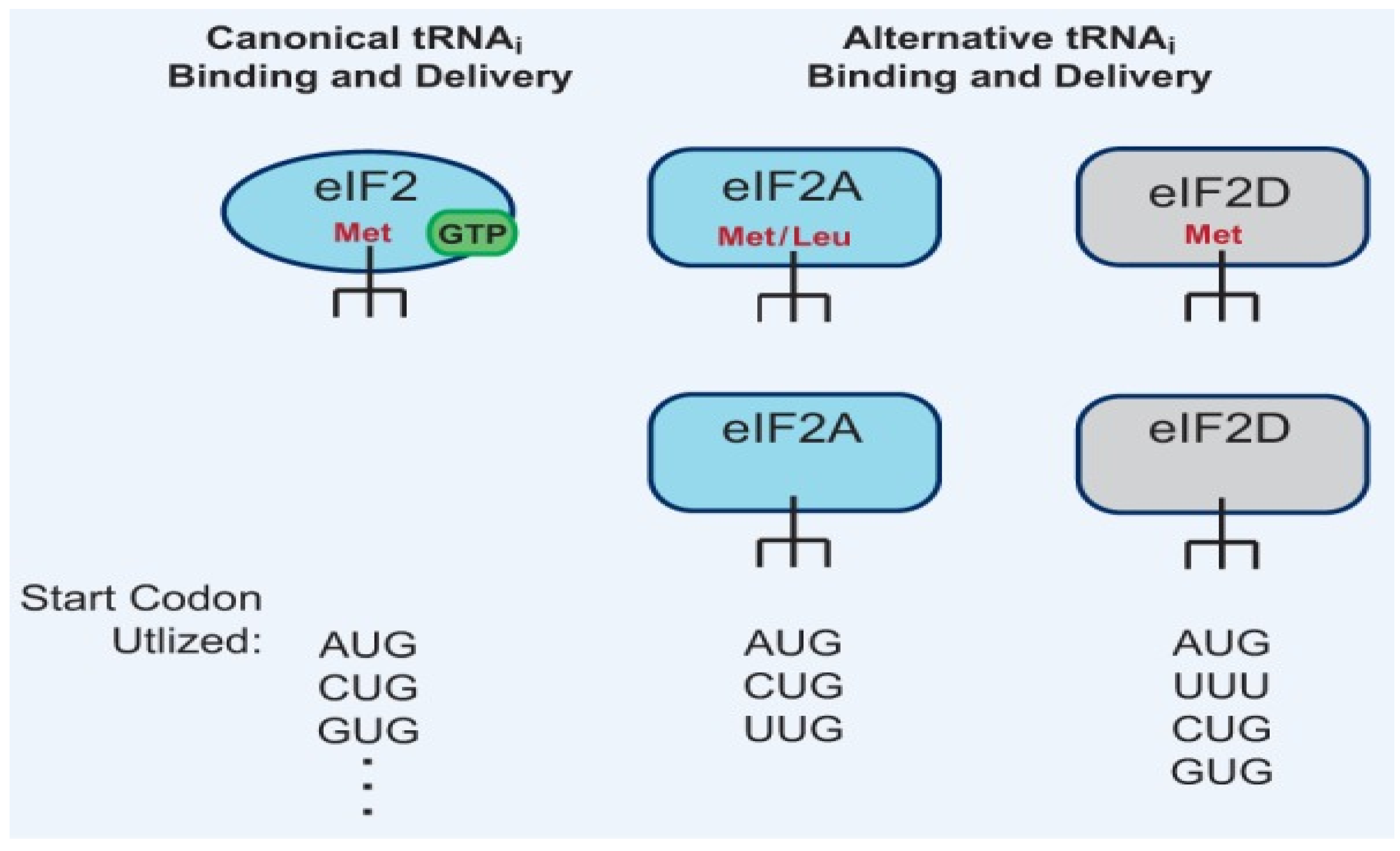

- This usually requires the use of alternative initiation factors like eIF2A or eIF2D instead of the canonical eIF2.

- These codons can lead to the synthesis of N-terminally extended or truncated isoforms.

- CUG is frequently used in the translation of transcription factor C/EBPα.

- Hox genes have shown evidence of non-AUG initiation, leading to protein variants with distinct localization or stability[8].

1.3.7. Upstream Open Reading Frames (uORFs) and Reinitiation

- After translating a uORF, the ribosome may dissociate or reinitiate at downstream sites depending on the availability of reinitiation factors.

- This regulation is sensitive to eIF2α phosphorylation and stress conditions.

1.3.8. Environmental Influences on AUG Codon Function

- These stressors often activate specific signaling pathways that lead to the phosphorylation or inactivation of key initiation factors (e.g., eIF2α, eIF4E).

- Some environmental conditions can also affect RNA structure by altering folding kinetics or stabilizing repressive elements near the AUG codon.

- Chronic exposure to environmental agents like arsenic or lead has been shown to induce long-term epigenetic changes, leading to altered ribosome behavior and start site selection.

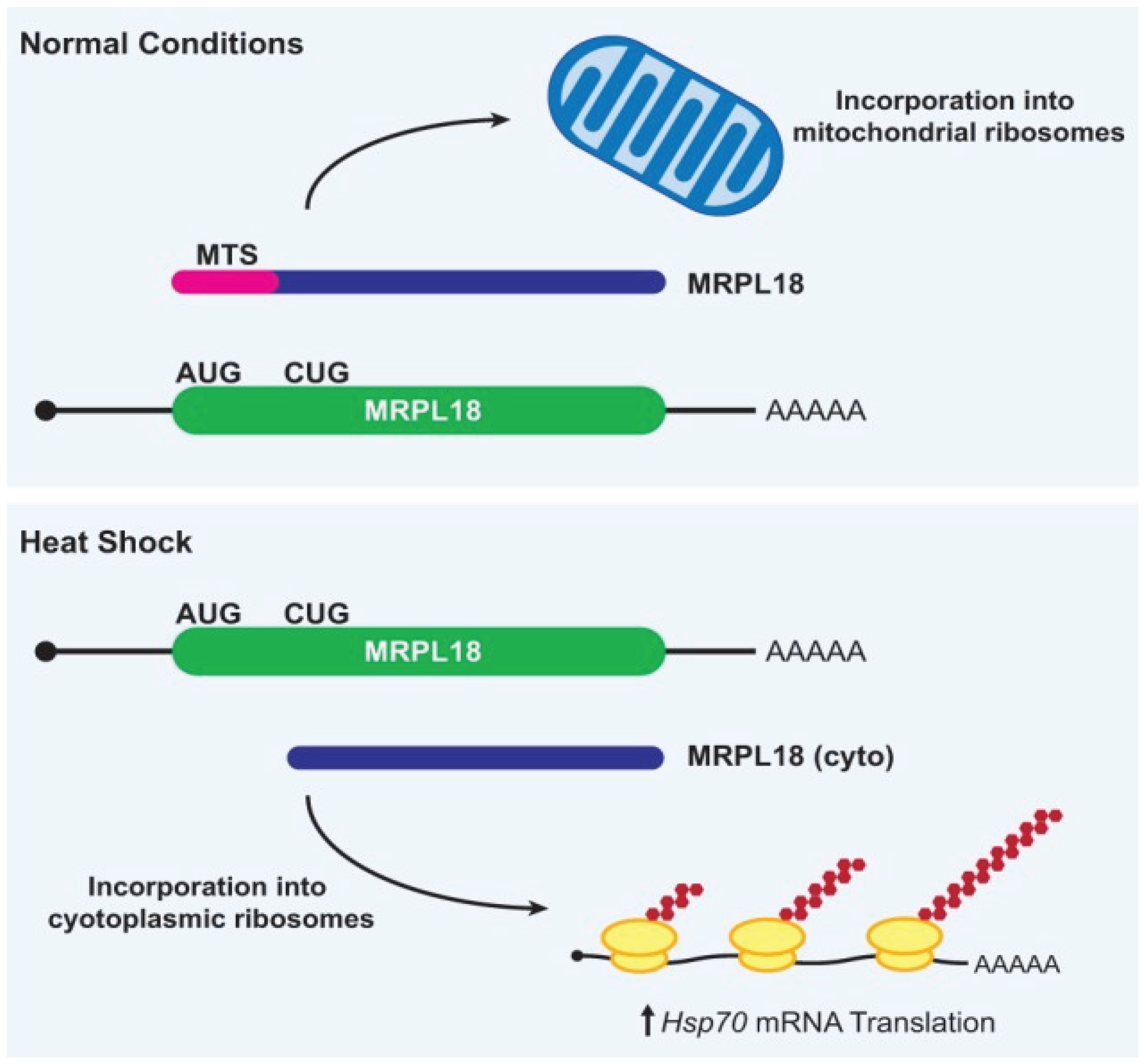

- Heat shock proteins (HSPs) are upregulated via alternative initiation mechanisms when canonical AUG recognition is impaired by temperature stress.

- Hypoxia-inducible factors (HIFs) are translated through cap-independent mechanisms like IRES when AUG-based scanning is inefficient.

1.4. Non-Methionine Start Codons

1.4.1. Natural

1.4.2. Engineered Start Codons

1.5. Met-tRNAiMet Is Generally, but Not Always, Used for Initiation in Eukaryotes

1.6. Usage of Non-AUG Initiation Codons Changes During Development and upon Stress

2. Conclusion

References

- Asano, K. Why is start codon selection so precise in eukaryotes? Translation 2014, 2, e28387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hinnebusch, A.G. Molecular mechanism of scanning and start codon selection in eukaryotes. Microbiology and molecular biology reviews 2011, 75, 434–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kozak, M. Point mutations define a sequence flanking the AUG initiator codon that modulates translation by eukaryotic ribosomes. Cell 1986, 44, 283–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hinnebusch, A.G. Molecular mechanism of scanning and start codon selection in eukaryotes. Microbiology and molecular biology reviews : MMBR 2011, 75, 434–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spriggs, K.A.; Bushell, M.; Willis, A.E. Translational regulation of gene expression during conditions of cell stress. Molecular cell 2010, 40, 228–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, R.J.; Hellen, C.U.; Pestova, T.V. The mechanism of eukaryotic translation initiation and principles of its regulation. Nature reviews. Molecular cell biology 2010, 11, 113–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartel, D.P. MicroRNAs: target recognition and regulatory functions. Cell 2009, 136, 215–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peabody, D.S. Translation initiation at non-AUG triplets in mammalian cells. The Journal of biological chemistry 1989, 264, 5031–5035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vattem, K.M.; Wek, R.C. Reinitiation involving upstream ORFs regulates ATF4 mRNA translation in mammalian cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2004, 101, 11269–11274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonenberg, N.; Hinnebusch, A.G. Regulation of translation initiation in eukaryotes: mechanisms and biological targets. Cell 2009, 136, 731–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RajBhandary, U.L. More surprises in translation: initiation without the initiator tRNA. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2000, 97, 1325–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starck, S.R.; Jiang, V.; Pavon-Eternod, M.; Prasad, S.; McCarthy, B.; Pan, T.; Shastri, N. Leucine-tRNA initiates at CUG start codons for protein synthesis and presentation by MHC class I. Science 2012, 336, 1719–1723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shetty, S.; Shah, R.A.; Chembazhi, U.V.; Sah, S.; Varshney, U. Two highly conserved features of bacterial initiator tRNAs license them to pass through distinct checkpoints in translation initiation. Nucleic acids research 2017, 45, 2040–2050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vincent, R.M.; Wright, B.W.; Jaschke, P.R. Measuring amber initiator tRNA orthogonality in a genomically recoded organism. ACS synthetic biology 2019, 8, 675–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kolitz, S.E.; Lorsch, J.R. Eukaryotic initiator tRNA: finely tuned and ready for action. FEBS letters 2010, 584, 396–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, H.; Chen, X.; Yin, Q.; Ruan, D.; Zhao, X.; Zhang, C.; McNutt, M.A.; Yin, Y. PTENβ is an alternatively translated isoform of PTEN that regulates rDNA transcription. Nature communications 2017, 8, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H.; Park, S.M.; Park, J.H.; Keum, S.J.; Jang, S.K. eIF2A mediates translation of hepatitis C viral mRNA under stress conditions. The EMBO journal 2011, 30, 2454–2464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komar, A.A.; Gross, S.R.; Barth-Baus, D.; Strachan, R.; Hensold, J.O.; Kinzy, T.G.; Merrick, W.C. Novel characteristics of the biological properties of the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae eukaryotic initiation factor 2A. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2005, 280, 15601–15611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, H.; He, S.; Yang, J.; Jia, X.; Wang, P.; Chen, X.; Zhang, Z.; Zou, X.; McNutt, M.A.; Shen, W.H.; et al. PTENα, a PTEN isoform translated through alternative initiation, regulates mitochondrial function and energy metabolism. Cell metabolism 2014, 19, 836–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sendoel, A.; Dunn, J.G.; Rodriguez, E.H.; Naik, S.; Gomez, N.C.; Hurwitz, B.; Levorse, J.; Dill, B.D.; Schramek, D.; Molina, H.; et al. Translation from unconventional 5′ start sites drives tumour initiation. Nature 2017, 541, 494–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golovko, A.; Kojukhov, A.; Guan, B.-J.; Morpurgo, B.; Merrick, W.C.; Mazumder, B.; Hatzoglou, M.; Komar, A.A. The eIF2A knockout mouse. Cell Cycle 2016, 15, 3115–3120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starck, S.R.; Tsai, J.C.; Chen, K.; Shodiya, M.; Wang, L.; Yahiro, K.; Martins-Green, M.; Shastri, N.; Walter, P. Translation from the 5′ untranslated region shapes the integrated stress response. Science 2016, 351, aad3867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dmitriev, S.E.; Terenin, I.M.; Andreev, D.E.; Ivanov, P.A.; Dunaevsky, J.E.; Merrick, W.C.; Shatsky, I.N. GTP-independent tRNA delivery to the ribosomal P-site by a novel eukaryotic translation factor. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2010, 285, 26779–26787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skabkin, M.A.; Skabkina, O.V.; Hellen, C.U.; Pestova, T.V. Reinitiation and other unconventional posttermination events during eukaryotic translation. Molecular cell 2013, 51, 249–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skabkin, M.A.; Skabkina, O.V.; Dhote, V.; Komar, A.A.; Hellen, C.U.; Pestova, T.V. Activities of Ligatin and MCT-1/DENR in eukaryotic translation initiation and ribosomal recycling. Genes & development 2010, 24, 1787–1801. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Han, K.-J.; Pang, X.-W.; Vaughan, H.A.; Qu, W.; Dong, X.-Y.; Peng, J.-R.; Zhao, H.-T.; Rui, J.-A.; Leng, X.-S.; et al. Large scale identification of human hepatocellular carcinoma-associated antigens by autoantibodies. The Journal of Immunology 2002, 169, 1102–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schleich, S.; Strassburger, K.; Janiesch, P.C.; Koledachkina, T.; Miller, K.K.; Haneke, K.; Cheng, Y.-S.; Küchler, K.; Stoecklin, G.; Duncan, K.E.; et al. DENR–MCT-1 promotes translation re-initiation downstream of uORFs to control tissue growth. Nature 2014, 512, 208–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janich, P.; Arpat, A.B.; Castelo-Szekely, V.; Lopes, M.; Gatfield, D. Ribosome profiling reveals the rhythmic liver translatome and circadian clock regulation by upstream open reading frames. Genome research 2015, 25, 1848–1859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jan, E.; Sarnow, P. Factorless ribosome assembly on the internal ribosome entry site of cricket paralysis virus. Journal of molecular biology 2002, 324, 889–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pestova, T.V.; Hellen, C.U. Translation elongation after assembly of ribosomes on the Cricket paralysis virus internal ribosomal entry site without initiation factors or initiator tRNA. Genes & development 2003, 17, 181–186. [Google Scholar]

- Cevallos, R.C.; Sarnow, P. Factor-independent assembly of elongation-competent ribosomes by an internal ribosome entry site located in an RNA virus that infects penaeid shrimp. Journal of virology 2005, 79, 677–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sasaki, J.; Nakashima, N. Methionine-independent initiation of translation in the capsid protein of an insect RNA virus. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2000, 97, 1512–1515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández, I.S.; Bai, X.C.; Murshudov, G.; Scheres, S.H.; Ramakrishnan, V. Initiation of translation by cricket paralysis virus IRES requires its translocation in the ribosome. Cell 2014, 157, 823–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koh, C.S.; Brilot, A.F.; Grigorieff, N.; Korostelev, A.A. Taura syndrome virus IRES initiates translation by binding its tRNA-mRNA–like structural element in the ribosomal decoding center. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2014, 111, 9139–9144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brar, G.A.; Yassour, M.; Friedman, N.; Regev, A.; Ingolia, N.T.; Weissman, J.S. High-resolution view of the yeast meiotic program revealed by ribosome profiling. science 2012, 335, 552–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachs, M.S.; Geballe, A.P. Downstream control of upstream open reading frames. Genes & development 2006, 20, 915–921. [Google Scholar]

- Chew, G.L.; Pauli, A.; Schier, A.F. Conservation of uORF repressiveness and sequence features in mouse, human and zebrafish. Nature communications 2016, 7, 11663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warner, J.R. The economics of ribosome biosynthesis in yeast. Trends in biochemical sciences 1999, 24, 437–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, Z.; Fujii, K.; Kovary, K.M.; Genuth, N.R.; Röst, H.L.; Teruel, M.N.; Barna, M. Heterogeneous ribosomes preferentially translate distinct subpools of mRNAs genome-wide. Molecular cell 2017, 67, 71–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Gao, X.; Coots, R.A.; Conn, C.S.; Liu, B.; Qian, S.B. Translational control of the cytosolic stress response by mitochondrial ribosomal protein L18. Nature structural & molecular biology 2015, 22, 404–410. [Google Scholar]

- Xue, S.; Tian, S.; Fujii, K.; Kladwang, W.; Das, R.; Barna, M. RNA regulons in Hox 5′ UTRs confer ribosome specificity to gene regulation. Nature 2015, 517, 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).