1. Introduction

Passive seismic techniques based on the analysis and interpretation of seismic noise recorded by triaxial seismometers have proven to be valuable tools for studying the mechanical properties of soil. The Horizontal-to-Vertical Spectral Ratio (HVSR), also known as the H/V Spectral Ratio, is a passive seismic technique used to determine the fundamental frequency of soil by computing the Fourier spectral ratio between the horizontal and vertical components of seismic noise at a given location. The analysis of this phenomenon enables the estimation of the soil fundamental frequency (f0), a parameter closely related to the thickness of sedimentary layers covering a basin and, consequently, to the depth of the underlying bedrock.

This approach was first proposed by

Nogoshi & Igarashi [1,2], but was later popularized by

Nakamura [3] for site-effect investigations. Due to its simplicity, it quickly gained popularity.

Lermo & Chávez-García [4] applied this method to S-wave seismic records and developed the theoretical foundation for the numerical inversion of SV-waves. A few years later,

Ibs-von Seht & Wohlenberg [5] identified a correlation between the fundamental frequency of a soil, measured through seismic noise, and the thickness of sedimentary layers. Their findings concluded that the Nakamura method is a powerful tool for estimating sediment thickness. Later,

Yamazaki and Ansary [6] expanded this approach to include site characterization, terrain classification, and other applications.

In Europe, the SESAME Project (Site EffectS assessment using AMbient Excitations) played a crucial role in assessing the reliability of the H/V and array techniques for site-effect estimation and seismic risk mitigation in urban areas. The project ultimately led to the development of guidelines for applying this technique [

7].

In recent years, the H/V Spectral Ratio method, also known as HVSR (Horizontal-to-Vertical Spectral Ratio) method, has been extensively used for characterizing the seismic properties of the subsurface, including site classification, site-effect analysis, and velocity structure inversion, among others (e.g.,

[8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15]). In the Guadalquivir Basin, the HVSR method has proven particularly effective for subsurface studies (e.g.,

[16,17,18,19,20,21]), enabling the identification of structures that influence the basin bedrock and shape its geomorphology.

The Guadalquivir Basin is a subtriangular basin, currently crossed by the river of the same name from east to west, with an approximately main direction of N070ºE, open towards the Gulf of Cádiz in the southwestern Iberian Peninsula. It represents one of the three major geological domains of Andalusia: to the north, the Variscan Iberian Massif (southern parts of the Central Iberian, Ossa-Morena and South Portuguese Zones); to the southeast, the Alpine Betic Cordillera; and between these, the Guadalquivir Basin. In the westernmost region of the basin, rivers display abrupt changes in orientation, shifting to approximately N-S directions. This pattern is evident in the Guadalquivir River, its tributary the Guadiamar, and the Tinto, Odiel, and Piedras rivers. The Guadiana River, which traverses the Variscan basement from east to west, undergoes a sharp directional change to flow north–south, roughly aligning with the 7.5ºW meridian, before continuing toward its mouth, where it forms part of the border between Portugal and Spain. These sudden changes, along with the asymmetry in riverbank morphology and the absence of meandering forms, contrast sharply with the overall smoothness and low gradient of the basin's relief (1–2° southeastward).

These features may be influenced by blind faults affecting both the basin’s bedrock and its overlying sediments, thereby conditioning its geomorphology, as suggested by

Viguier [22] and

Alonso-Chaves et al., [19]. However, the region's surface geology, dominated by Neogene and Quaternary sediments derived from the dismantling of the Variscan basement to the north and the Alpine orogenic front to the east and southeast, can obscure these structures, making their identification highly challenging.

In this context, passive seismic techniques, such as the H/V spectral ratio method, are crucial for identifying the soil fundamental frequency, which is closely linked to the depth of the contact between materials with high mechanical contrast, such as soft sediments and hard bedrock. In the Guadalquivir Basin, Miocene and Pliocene sediments overlie a Paleozoic basement, with localized Mesozoic outcrops in Niebla and Ayamonte. The basin’s basal unit, known as the Niebla Formation

[23,24], is composed of calcarenitic sediments identified in deep boreholes (Alonso-Chaves et al., 2019). This formation also acts as a mechanically rigid substrate (though not corresponding to the geological basement), with an estimated thickness of 10–20 meters that slightly increases toward the basin interior [

24].

This study aims to achieve two primary objectives. First, it seeks to determine the soil fundamental frequency through passive seismic methods, specifically the HVSR method, to estimate the depth of the mechanical bedrock. Second, it analyzes the western margin of the Guadalquivir Basin by integrating seismic interpretations with surface geological information and borehole data to identify the tectonic structures conditioning the landscape and to construct a three-dimensional model of the underlying bedrock. Ultimately, the study aims to provide a tectonic perspective on the geodynamic evolution of the forebulge zone of the Betic orogen and to explore how strain partitioning may explain the presence of extensional structures in a region adjacent to an orogenic front within a plate convergence context.

2. Geographical and Geological Setting

Geologically, the study area is located to the west of the Sevilla meridian in the Guadalquivir Basin, where the basin widens before being covered by the waters of the Atlantic Ocean. It lies between 37.10ºN and 37.50ºN latitude and 7.4ºW and 6.18ºW longitude (see

Figure 1). The area extends from the vicinity of Aznalcóllar (Seville) in the northeast to the city of Ayamonte in the southwest, encompassing the southern region of Huelva province and the southwestern portion of Seville province.

The Guadalquivir Basin is a major Neogene foreland depression located at the front of the Betic orogen. Since the mid-20

th century, the region has attached sustained interest from the oil industry due to the structural and stratigraphic configuration of its sedimentary fill, which hosts tectono-stratigraphic trap systems with favorable reservoir and seal characteristics [

25]. These geological units are marked by considerable thickness, extensive lateral continuity, and excellent sealing and isolation capacities, making them highly suitable for fluid accumulation and long-term storage. Although the basin’s hydrocarbon reservoirs—primarily composed of biogenic gas— are currently depleted or in the process of depletion, their potential for conversion into underground gas storage facilities is under active investigation.

Moreover, the basin’s basement has drawn increasing interest from the mining sector, owing to the presence of economically significant copper and other metal deposits. Given that until the early 21st century, mining activity in the region was largely concentrated in sites inherited from Roman times—or even earlier—with most operations located where mineral outcrops had historically been identified. A notable exception is the Cobre Las Cruces mine, the only one situated within the interior of the Guadalquivir Basin whose ore deposit is entirely buried beneath Neogene sediments, with no surface exposure. In this case, the ore body—characterized by a more rigid mechanical behavior—lies in direct contact with a softer marly cover, raising the possibility that other mineral deposits may remain buried beneath the basin’s sedimentary fill.

The most prominent geological feature in the study area is the discordance between the basin infill and the Variscan basement to the north. This discordance exhibits a primary N070ºE orientation (parallel to the northern boundary of the basin), dipping gently to the southeast. (see

Figure 1)

The basement rocks of the study area outcrop in the northern and northwestern sectors and belong to the South Portuguese Zone, the southernmost geological province of the Iberian Massif. These rocks include:

- Phyllite-Quartzite Group (PQ Group) Upper Devonian in age (e. g.,

[26,27]): Located in the northeasternmost portion of the area (colored in greyish blue in

Figure 1).

- Volcano-Sedimentary Complex ranging in age from the Upper Devonian to the Lower Carboniferous (e. g., [

28]): Notable for its significant massive sulfide deposits, location of numerous mineral deposits (brownish in

Figure 1).

- Synorogenic Unit of Culm Facies, a Carboniferous unit: Paleozoic shales and greywackes deposited on the Paleozoic seafloor (e.g.,

[26,27]), which cover the largest area of the study region (greyish green in

Figure 1)

Figure 1.

Geological map of the southwestern part of Iberia. In the upper left, a schematic representation of the three main domains in the southern Iberian region is shown: the Iberian Massif, the Guadalquivir Basin, and the Betic System. The red square highlights the area depicted in the detailed map.

Figure 1.

Geological map of the southwestern part of Iberia. In the upper left, a schematic representation of the three main domains in the southern Iberian region is shown: the Iberian Massif, the Guadalquivir Basin, and the Betic System. The red square highlights the area depicted in the detailed map.

These units, ranging from the Middle Devonian to the Upper Carboniferous, were affected by the Variscan Orogeny, and their main tectonic structures and fabrics show a predominant NW-SE strike. Locally, these basement rocks are overlain by Triassic deposits (red in

Figure 1), including sandstones, carbonates, and volcanosedimentary rocks, which outcrop near Ayamonte and Niebla.

On the other hand, the sedimentary fill of the Guadalquivir Basin exhibits a marked transverse asymmetry from the middle Miocene to the Holocene. In the sector nearest to the Alpine orogenic front, the stratigraphic record is characterized by olistostromic units interbedded within the Neogene sequence. In contrast, the outermost part of the basin—where the present study is concentrated—reflects crustal flexure processes associated with the development of a forebulge structure.

The basal stratigraphic unit, dated to the Tortonian, corresponds to a well-documented transgressive sequence that extends westward from the Doñana National Park area. Its lower boundary, marking the top of the geological basement, is clearly defined in seismic reflection profiles acquired by oil companies. Overlying this unit are several younger depositional sequences: (1) a Tortonian–Messinian 1 transgressive sequence; (2) a Messinian 2–Pliocene 1 regressive sequence linked to a major eustatic sea-level fall; (3) a Pliocene 2 transgressive sequence; and (4) a Pliocene 2–Pleistocene sequence, predominantly continental in nature, particularly in the distal parts of the basin

[30,31]. A brief discussion of some of the sedimentary units described in the regional geological literature is presented below.

- Niebla Formation (Tortonian): Calcarenitic sediments constituting the basal transgressive complex of the basin [

32] (salmon in

Figure 1). This unit has been identified in boreholes located far from Niebla within the basin [

18]. These calcarenitic sediments act as a mechanical, not geological, basement

[19,20,21]. The geological (Variscan, Mesozoic) bedrock has to be found a few meters below this mechanical basement.

- Gibraleón Clays and Blue Marls Formation (Upper Tortonian–Lower Pliocene): Composed of clays and marls with some silt and sand levels. These layers exhibit glauconite-rich horizons and thicknesses ranging from 30–35 m near the Guadiamar River to over 2000 m southeast of Villamanrique de la Condesa (e. g.,

[23,33,34]) (yellow in

Figure 1).

- Huelva Sands Formation (Lower Pliocene): Silty sands with glauconite-rich basal levels, reaching a thickness of ~30 m

[23,35] (intermediate yellow in

Figure 1).

- Bonares Sands Formation (Upper Pliocene): Fine-grained sands with a maximum thickness slightly greater than 20 m

[23,35] (light yellow in

Figure 1).

- Pleistocene Conglomerates (Conquero Continental Unit, Pleistocene): Characterized by reddish gravel and coarse-grained sand layers with a maximum thickness of ~25 m [

36].

- Quaternary Deposits: Fluvial sediments (conglomerates, sandstones, gravels, and sands) associated with terraces and low-elevation deposits, as well as marine-fluvial deposits and marsh clays and silts (light and dark grey in

Figure 1)

All these Neogene units exhibit a gentle homocline structure with dips generally below 5º toward the southeast.

Data from boreholes drilled by the IGME (Spanish Geological Survey) and various oil companies along with seismic profiles [

31] reveal the presence of olistostromic complexes in nearby areas. These complexes may exhibit mechanical contrasts resembling a geological basement. However, given the location and depth of these olistostromic units, their presence in the study area is unlikely to be detected with the methodology used in this work.

In the western Guadalquivir Basin, river systems display a pronounced reorientation to a N-S direction. Notably, the Guadalquivir River changes its course near Seville, shifting from an overall N070ºE trend to a southward flow towards the Gulf of Cádiz. This behavior is especially evident in the segment between the meridians of Aznalcóllar and Villamanrique de la Condesa. The river margins exhibit notable asymmetry, with the eastern margin presenting a slope gradient below 5%, while the western margin exceeds 30%. The tributary networks further highlight this contrast: the eastern tributaries are characterized by longer courses and more hierarchical drainage systems, whereas the western side lacks major tributaries, instead comprising short, first-order streams.

A similar pattern is observed in the Guadiamar River, a tributary of the Guadalquivir. Originating in the Sierra de Aracena (Huelva), the Guadiamar flows NW-SE before reorienting to a NNE-SSW direction near Aznalcóllar (Seville). In this segment, between Aznalcóllar and Villamanrique de la Condesa, the western margin features a hierarchical drainage network with a slope gradient below 10%, while the eastern margin comprises short, first-order tributaries with gradients exceeding 30%.

This asymmetry is also apparent in other rivers within the Guadalquivir Basin, including the Tinto, Odiel, and Piedras Rivers. For example, the Tinto River flows sinuously through Huelva province, transitioning to a pronounced N045ºE orientation near Moguer, northeast of Huelva, before discharging into the Ría de Huelva, the estuarine zone where it converges with the Odiel River. Its eastern margin exhibits steep slopes exceeding 30%, while the western margin consists of extensive marshlands with gradients below 5% (to get an idea of the slope of these river margins, refer to

Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Elevation map over orthophotography (provided by the IGN), color-coded by range to highlight the slope on both margins of the two rivers.

Figure 2.

Elevation map over orthophotography (provided by the IGN), color-coded by range to highlight the slope on both margins of the two rivers.

Similarly, the Odiel River originates in the Sierra de Aracena and Picos de Aroche Natural Park (Huelva), flowing NW-SE through a narrow and steep valley until reaching the water reservoir “Embalse del Sancho”, located north of Gibraleón. From this point, the river adopts a N-S orientation, transitioning into an expansive marshland more than 4 km wide (designated as the Natural Area “Marismas del Odiel”) with gradients below 1% (see again

Figure 2). The eastern margin of the Odiel is marked by prominent relief (up to 50 meters, locally known as “Cabezos de Huelva") with slopes occasionally exceeding 50%, while the western margin exhibits more subdued topography with elevations around 20 meters and slopes exceeding 10%.

Although less pronounced, the Piedras River also displays a reorientation in its final segment, adopting a well-defined NNE-SSW orientation over its last 12 km near the town of Lepe.

Special mention should be made of the numerous anthropogenic deposits and fills that cover the surface of the study area. Notably, immediately east of the city of Huelva, there is a massive phosphogypsum pond located directly on the marshlands, with dimensions nearly comparable to those of the city itself, which pose a significant environmental risk in the event of a plausible earthquake or tsunami. Additionally, the entire study area has been extensively used for agricultural purposes.

3. Methodology

The seismic noise recording in the Guadalquivir Basin was conducted in order to apply the Horizontal to Vertical Spectral Ratio (HVSR) method, which facilitates the identification of the soil fundamental frequency. This parameter is closely linked to the thickness of the sedimentary cover overlying a hard rock basement. The depth (h) of the mechanical discontinuity between the crystalline basement and the “soft” sedimentary cover is strongly correlated with the soil fundamental frequency (f

0) and the shear wave velocity (V

S) [

37]. By applying an empirical equation, which relates the depth of the rock basement (not necessarily the geological Variscan basement) to the soil fundamental frequency, a three-dimensional map of the basin’s basement can be constructed.

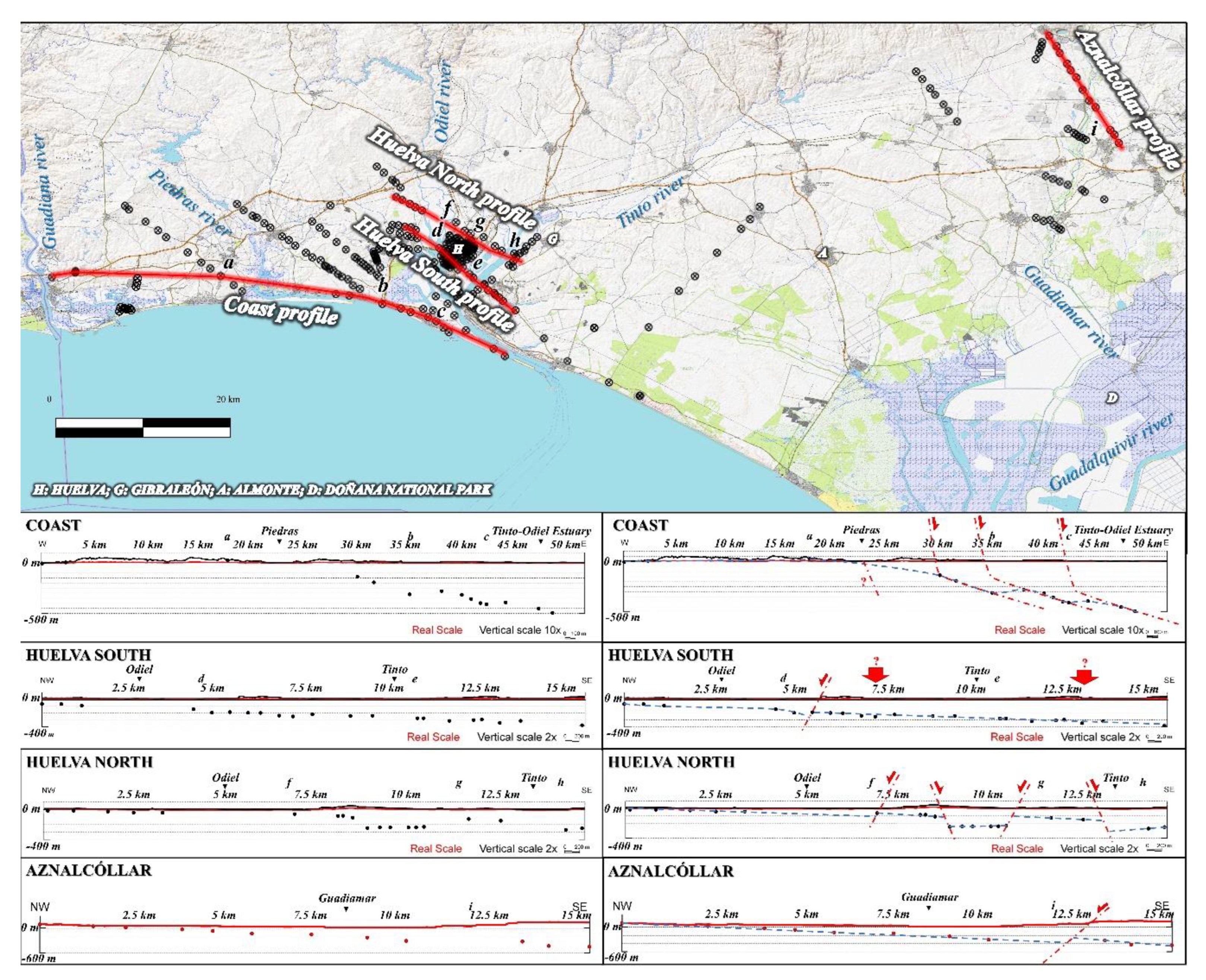

Seismic noise measurements were carried out at a total of 334 discrete sampling points, many of which were integrated into profiles. Most of these profiles are oriented approximately NW-SE, following the general slope of the basement-cover contact (see

Figure 3), with variable lengths ranging from 2 km to over 35 km. Additionally, orthogonal NE-SW profiles were designed to delineate potential structural features affecting the area.

The primary limitations encountered during this study were related to restricted access to protected areas, such as the “Marismas del Odiel” Natural Area (Huelva) and the Guadiamar Green Corridor (Seville), which limited vehicle entry and access to certain zones. However, efforts were made to maintain a sufficiently dense sampling grid in these areas to mitigate data gaps. Additional challenges included intense agricultural, industrial, and urban land use, which further restricted access to specific sites. Sampling efforts were consequently adapted to public areas, such as forest roads, walking paths, and other accessible zones.

This study includes seismic noise recordings acquired during the development of the ALERTES-RIM project, focusing on the central sampling area, specifically the city of Huelva and nearby industrial zones. Within this region, 5 seismic arrays were deployed in the city of Huelva to determine S-wave velocities (V

S), and 45 H/V sampling points were recorded, the results of which were previously published by the research team

[17,19].

Additionally, this work incorporates data collected during six subsequent campaigns outside the scope of the ALERTES-RIM project and PGC2018-100914-B-I00, covering a total area exceeding 2,300 km² (see location in

Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Location of seismic noise sampling points in the western Guadalquivir basin.

Figure 3.

Location of seismic noise sampling points in the western Guadalquivir basin.

The profiles were designed to ensure continuity in the seismic noise data, spanning from the boundary of the basin, where the Variscan basement (geological substratum) outcrops, towards the interior of the basin. This design facilitates the development of both surface and basement topographic profiles.

Some sampling points were positioned directly above historical deep exploratory boreholes, enabling the derivation of empirical relationships for calculating the depth of the basement rock

[16,17]. Additional details on sampling, locations and other relevant information are provided in

Table A1 of the annexes.

Seismic noise measurements were made with a SARA SL06 digitizer and a Lennartz LE 3D/5s triaxial seismometer, with a natural frequency of 0.2 Hz. Exceptionally, Lennartz LE-3D/20s, with natural frequency of 0.05 Hz were employed in areas presumed to have greater basement depths (southeastern portion of the study area). The equipment simultaneously recorded both time (UTC) and location through an integrated GPS device. The measurements used a sampling frequency of 200.

The minimum recording time was approximately 25–30 minutes, with a standard duration of 45 minutes per sampling session. Exceptionally, longer recording times (up to 90 minutes) were used in areas with adverse conditions, such as high background noise from vehicular traffic or greater substrate depths.

The recorded signal was processed using Geopsy (v. 3.4.2) [

38], which generates graphs that relate the Fourier spectra of the horizontal components (N and E) to the vertical component (Z). This process yields an H/V vs. frequency graph from which the soil fundamental frequency (f

0) is determined. Between 7 and 19 calculation windows, each approximately 300 seconds long, were utilized for this analysis.

In most cases, the highest amplitude and lowest frequency peak in these graphs corresponds to the soil fundamental frequency. The high amplitude and narrow width of the peaks allowed for a precise determination of f0.

The interpolation maps of basement depth were generated using Surfer (v. 15.6.3), employing kriging interpolation. These maps were subsequently imported into QGIS (v. 3.32), where they were overlaid onto the surface geological map.

4. Results and Interpretations

4.1. Empirical Equation for the Estimation of the Basement Depth from Vs and f0 for the Western Guadalquivir Basin

The soil fundamental frequency (f

0) is related to the shear wave velocity in the soft soil layer (V

S) and the thickness of this layer (h) following the relationship proposed by

Bard [37] (1):

To calculate the depth of the bedrock (h), it is necessary to know the vertical profile of shear wave velocity (V

S) at each point where the fundamental frequency of the soil (f

0) has been measured. However, this information is often not available a priori. To address this issue, the vertical profile of V

S is parameterized using empirical relationships of the form h=a·f

0b, derived from mechanical borehole or geophysical exploration data

[5,39,40]. Evidently, the parameters

a and

b depend on the geomechanical characteristics of the materials constituting the soft soil layer.

A new empirical relationship has been developed (

Figure 4) for the southwestern region of the Guadalquivir Basin by combining data from the H/V spectral ratio method, array techniques (5 datasets), reflection seismics (2 datasets), and mechanical boreholes (2 datasets) that reached the bedrock. This empirical relationship was calibrated using nine data pairs, covering a frequency range from 0.27 to 0.89 Hz and a wide depth range from 120 to 650 meters. The correlation coefficient for this relationship is 97.44% (see

Figure 4).

The equation used for estimating the depth is as follows (2):

Figure 4.

Empirical relationship for calculating the depth of the bedrock in the Guadalquivir Basin (near the city of Huelva) based on the fundamental frequency.

Figure 4.

Empirical relationship for calculating the depth of the bedrock in the Guadalquivir Basin (near the city of Huelva) based on the fundamental frequency.

This differs slightly from the equation used in

Alonso-Chaves et al. [19].

4.2. H/V Graphs, f0 and Estimated Basement Depth

Figure 5.

Example of the five different responses obtained during the study. Dashed lines represent the measurement error, while continuous lines represent the average. The gray bands correspond to the uncertainty range in the calculation of f0, where a wider band indicates greater indeterminacy in f0. Finally, a peak is considered when its amplitude exceeds 2H/V.

Figure 5.

Example of the five different responses obtained during the study. Dashed lines represent the measurement error, while continuous lines represent the average. The gray bands correspond to the uncertainty range in the calculation of f0, where a wider band indicates greater indeterminacy in f0. Finally, a peak is considered when its amplitude exceeds 2H/V.

The analysis of 334 seismic noise sampling points has led to the conclusion that most of the H/V spectral ratio graphs exhibit high amplitude and a sufficiently defined peak width for accurate peak identification, with at least one peak exceeding 2 H/V (a necessary criterion for considering it as f

0). Furthermore, five distinct response types have been identified in the H/V spectral ratio (see

Figure 5):

- a)

High-frequency H/V peaks (>1 Hz): Characteristic of areas where the bedrock is closer to the surface.

- b)

Low-frequency H/V peaks (<1 Hz): Indicative of deep-seated bedrock.

- c)

Broad peaks: Potentially associated with irregular bedrock surfaces, such as fault zones, which are critical areas for further study.

- d)

Multiple peaks (at least two exceeding 2 H/V): Typically found in marshlands or areas with significant lithological contrast between unconsolidated Quaternary sediments and other type of Neogene sediments.

- e)

Flat response (no peaks exceeding 2 H/V): Classified as "rock", characteristic of shallow or exposed bedrock.

The fundamental frequency (f

0) estimated from these graphs ranges from 0.23 to 18 Hz, covering a wide spectrum of values (see

Figure 6). The highest frequencies are systematically located near the basin margins (northern and northwestern areas), while lower frequencies dominate in the basin interior (southeastern areas). The f

0 values progressively decrease toward the SE, which correlates with the expected increase in sediment thickness and bedrock depth toward the basin interior (from NW to SE). Notably, the color bands representing different frequency ranges align closely with the structural boundary between the bedrock and sedimentary cover.

Figure 6.

Fundamental frequency data measured with passive seismic over the same geological map of the study area (

Figure 1). The colors represent different ranges of fundamental frequency: cold colors correspond to high frequencies, while warm colors indicate low fundamental frequencies.

Figure 6.

Fundamental frequency data measured with passive seismic over the same geological map of the study area (

Figure 1). The colors represent different ranges of fundamental frequency: cold colors correspond to high frequencies, while warm colors indicate low fundamental frequencies.

Similarly, as shown in

Figure 7, the flat response (rock-type, marked with a blue cross in the figure), observed at only one sampling point, is also located in the northwestern area, where the bedrock is either more exposed or even visible in certain sections.

Moreover, the areas where double-peak responses (green stars in

Figure 7) are most concentrated are specifically located in marshlands and floodplains of various rivers. Wide peaks (yellow crosses in

Figure 7) are systematically found along NE-SW oriented corridors near the Odiel River (on both the right and left banks) and NNE-SSW in the case of the Guadiamar River. As observed, these align with remarkable precision along fault traces identified through cartographic methods. However, no fault planes could be identified at the surface due to the unconsolidated nature of the overlying materials.

The basement depth is estimated to range from just a few meters below the surface level (or even outcropping in some areas) in the northern and northwestern parts of the study area to depths exceeding 600 meters, reaching up to -667 meters above the sea level in the southeasternmost sector (

Figure 8).

The isolines corresponding to the mechanical basement elevation follow a fairly consistent N70-80ºE direction, aligning well with the morphology and orientation of the Guadalquivir Basin. However, deviations in orientation are observed near the rivers (Odiel, Tinto, and Guadiamar), where the isolines locally shift to an E-W direction, particularly beneath the city of Huelva, dipping southward. This pattern may be attributed to fractures affecting both the mechanical (and geological) basement and the overlying Neogene sediments.

Figure 7.

Location of the different types of H/V spectral ratio responses vs. f

0 (examples of each response type are shown in

Figure 5) in the westernmost sector of the Guadalquivir Basin, overlaid on the geological map of the area (

Figure 1).

Figure 7.

Location of the different types of H/V spectral ratio responses vs. f

0 (examples of each response type are shown in

Figure 5) in the westernmost sector of the Guadalquivir Basin, overlaid on the geological map of the area (

Figure 1).

Figure 8.

Map of basement depth (in meters above the sea level) estimated by kriging interpolation, based on depths obtained through the H/V method over the geological map (

Figure 1). Faults in the study area have been smoothed to emphasize contour lines. Colored points represent depths derived from seismic noise measurements, while black points indicate depths obtained from borehole logging by IGME.

Figure 8.

Map of basement depth (in meters above the sea level) estimated by kriging interpolation, based on depths obtained through the H/V method over the geological map (

Figure 1). Faults in the study area have been smoothed to emphasize contour lines. Colored points represent depths derived from seismic noise measurements, while black points indicate depths obtained from borehole logging by IGME.

4.3. Profiles

Based on the transects conducted, most of which follow a NW-SE orientation and approximate the true dip of the mechanical basement, an average slope of approximately 1-3º dipping towards the SE has been estimated, with a standard deviation of around 1º. However, as seen in

Figure 9, significant localized slope breaks of 5-7º have been identified. These slope discontinuities can be correlated across adjacent profiles (see

Figure 9, also can be seen corresponding figures in

Amador Luna et al. [20,21]). Notably, these ruptures tend to occur in areas near river channels.

In the Coast profile, three abrupt slope changes have been identified: two at the beginning of the Odiel marshes (on the western bank of the Odiel River, marked as

b in

Figure 9) and another at the confluence of the Odiel and Tinto rivers (

c in the same figure). This subsurface morphology could explain the structural highs to the west and the depressed areas to the east (Odiel marshes and Huelva Estuary). The terraced morphology may be attributed to ancient river terraces on the western bank or to brittle structures (faults) that have downthrown the eastern sector.

Figure 9.

Map showing the location of sampling points used to establish topographic and mechanical basement depth profiles. The lower section displays the profiles for each transect, with the red line representing the true-scale profile and the black line showing the vertically exaggerated scale (the vertical exaggeration is indicated in the lower right corner of each profile). Black and red points represent the estimated depth. On the right, the same profiles are presented with interpreted data: the dashed blue line represents the mechanical (non-geological) basement, while the dashed red line marks faults that may explain slope discontinuities. Additionally, the locations of various rivers and specific points of interest (labeled with letters) are indicated. The arrows with question marks indicate areas where the slope changes; however, further study would be required for a rigorous interpretation.

Figure 9.

Map showing the location of sampling points used to establish topographic and mechanical basement depth profiles. The lower section displays the profiles for each transect, with the red line representing the true-scale profile and the black line showing the vertically exaggerated scale (the vertical exaggeration is indicated in the lower right corner of each profile). Black and red points represent the estimated depth. On the right, the same profiles are presented with interpreted data: the dashed blue line represents the mechanical (non-geological) basement, while the dashed red line marks faults that may explain slope discontinuities. Additionally, the locations of various rivers and specific points of interest (labeled with letters) are indicated. The arrows with question marks indicate areas where the slope changes; however, further study would be required for a rigorous interpretation.

In the Huelva profiles, slope changes correlate well with known structural highs identified in the topographic profile, such as the Cabezos de Huelva, east of the Odiel (point d), and the Cabezos de Moguer and Palos, east of the Tinto River (only slightly visible east of the Huelva North profile). A slight elevation, corresponding to the location of northern part of the current phosphogypsum deposits is also observed just east of the city (g in the Huelva North profile).

Although the Huelva South profile requires further investigation in the areas marked with question marks in

Figure 9, the slope changes show a very good correlation with the faults interpreted (and much more evident) in the Huelva North profile. Notably, the slope changes in both cases occur along corridors that can be correlated between the two profiles.

Another possibility is that the structures identified in the northern profile exhibit greater vertical displacements (several tens of meters) than those in the southern profile (a few tens of meters), making them more difficult to identify. A more detailed study at a smaller scale is planned in the future in order to better delineate these structures.

Across all cases, it is evident that sediment thickness remains minimal in the northwestern sector but increases markedly east of the Odiel River meridian, highlighting significant subsidence in the southeastern region.

In the Aznalcóllar area, the slope change becomes evident beyond the Guadiamar River, coinciding at the surface with an increase in topographic elevation. This could be explained by the presence of a fault that relatively uplifts the eastern block. Although no fault planes have been identified at the surface, the significant basement offset and the corresponding change in the eastern riverbank slope suggest the existence of an uplifted block.

In all cases, these slope discontinuities can be attributed to faults affecting both the mechanical (and geological) basement and the sedimentary cover. These faults are high-angle structures, extending over 8 to 15 km, with vertical displacements between 50 and 100 m, and can be correlated across different profiles, following NE-SW to NNE-SSW orientations.

5. Discussion

5.1. Geology and Passive Seismic Results

As shown in

Figure 6 to

Figure 9, the results from passive seismic methods are highly consistent with surface geology and the depth estimations inferred from it. High-frequency signals (indicating shallower basement depths) are systematically located near the boundary between the basement and the sedimentary basin, progressively deepening toward the southeast, as expected. Conversely, low-frequency signals (indicating deeper basement levels) are concentrated in the southeastern areas (near to Mazagón or Villamanrique de la Condesa surroundings). The primary orientation of the isolines also exhibits a strong parallelism with this boundary, following an N60–80ºE trend. Changes in the basement slope direction coincide with the river channels and variations in surface topography, aligning with the mapped fault traces. However, no fault planes have been identified at the surface. Due to the lithological characteristics of the area—dominated by expansive clays—the identification of fault planes in the field becomes particularly challenging. These materials are prone to intense weathering and plastic deformation, which tend to obscure or entirely erase the structural evidence typically associated with fault planes. As a result, surface expressions of tectonic structures are often subtle or absent, making direct observation and mapping of fault planes virtually impossible without geomorphological criteria or geophysical or subsurface data.

The cross-sections reveal significant changes in the deep basement slope, which also correlate with geomorphological features and mapped fault traces. These vertical separations are estimated to range between 50 and 100 meters, affecting both the basement and its overlying cover, which may explain certain cartographic features. These slope variations can be correlated across different profiles, exhibiting an approximate N70–80ºE (or even NNE–SSW) orientation, once again coinciding with the basin’s main structural trend.

Two main interpretations can be proposed for these slope changes: (i) they may correspond to ancient fluvial terraces of the Guadalquivir River, which has migrated eastward since the Miocene, leaving elevated terraces in the westernmost part of the basin; or (ii) they may be associated with fractures that control both surface relief and river courses. If the latter is the case, these fractures align well with the passive seismic records, where broad spectral peaks have been observed, typically associated with irregular basement structures such as fault zones. These alignments are consistent with previous studies

[19,41]. Therefore, these slope discontinuities can be attributed to faults affecting both the mechanical (and geological) basement and the sedimentary cover. These faults are high-angle structures, extending over 8 to 15 km, with vertical displacements between 50 and 100 m, and can be correlated across different profiles NE-SW to NNE-SSW. A possible interpretation of these slope variations along the cross-sections as faults is illustrated in

Figure 9 (right), where many of these fractures can be correlated across different profiles.

Three main fault zones have been identified in the western part: one at the easternmost end of the Odiel River (coinciding with the relief of the Cabezos de Huelva, see

d and

f in

Figure 9), another at its western margin (see

b in

Figure 9), and a third one along the eastern margin of the Tinto River near Moguer. Additionally, another fault may be present along the eastern margin of the Guadiamar River. In the central sector of the study area, particularly near Almonte, a noticeable curvature in the orientation of the isolines is observed. This feature coincides with changes in lithology and topographic forms, suggesting the possible presence of a fault, although its fault plane is not identifiable in the field. The so-called “Almonte Fault” and its surrounding areas will be the subject of future investigations, aimed at identifying additional fault structures inferred from satellite imagery, even if their fault planes remain untraceable on the ground.

Figure 2 further reveals a sharp topographic break in southern Huelva. The orientation of this possible structure is also reflected in one of the western branches of the Odiel River, and if extended eastward, it coincides with the phosphogypsum deposits. This WNW–ESE-trending structure can also be identified in seismic records, where broad spectral peaks align in the same direction. Moreover,

Figure 2 shows that the elevation of the phosphogypsum deposits in the northern sector (>30 m) is higher than in the southern sector (where maximum elevations are around 20 m), potentially indicating subsidence of the southern block, consistent with a south-dipping normal fault. These observations are in agreement with previous studies by

González [42] and represent a significant environmental risk due to the critical location of these deposits above a structural feature. This feature can be inferred from not only by digital imagery (as shown in

Figure 2), deduced from changes in the orientation of the isolines in

Figure 8, and even identified in the seismic profiles in

Figure 9 (point

e).

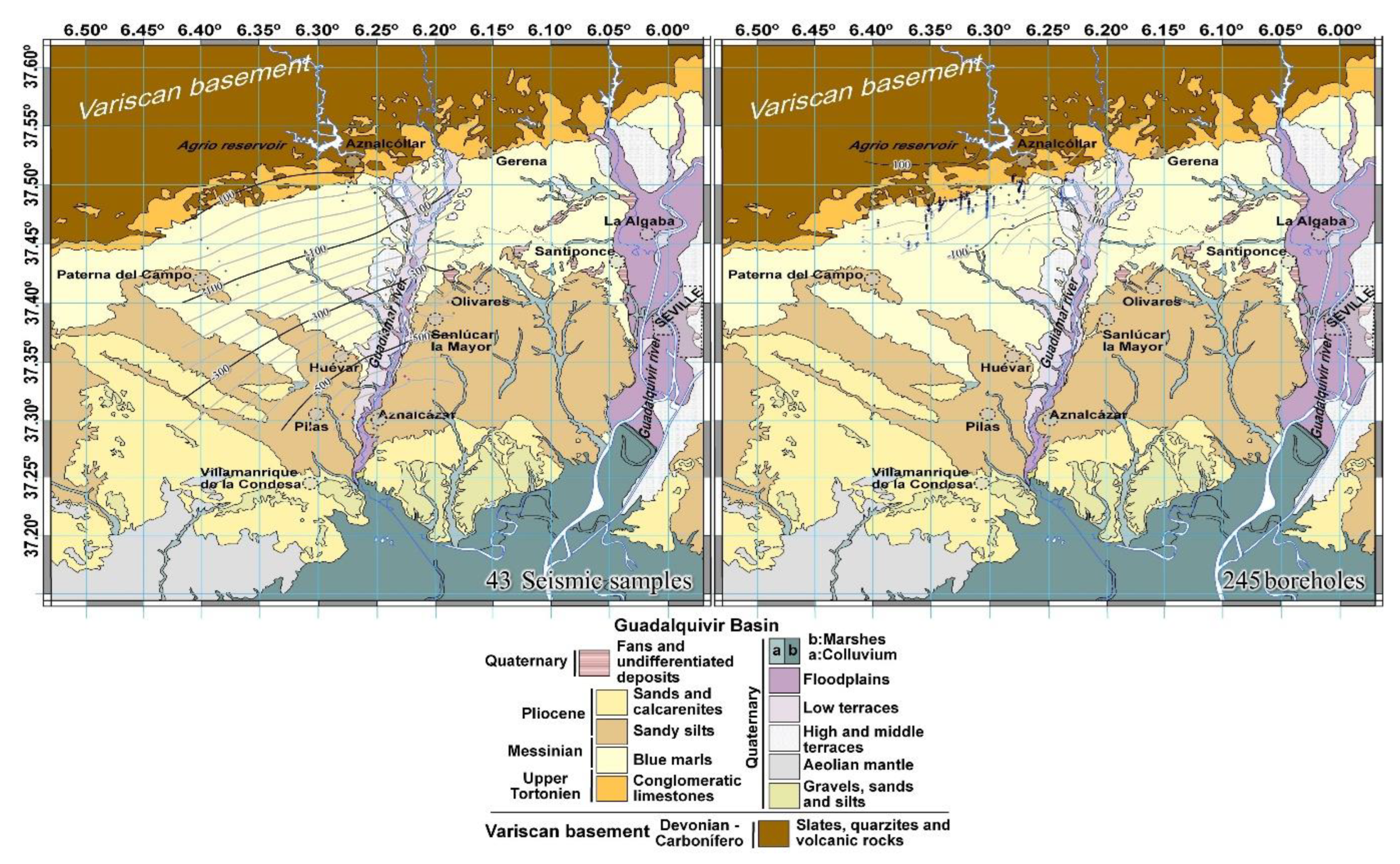

5.2. Boreholes

Some of the passive seismic measurements, as shown in

Figure 8, were conducted directly above historical boreholes drilled by the IGME and oil companies. These measurements aimed to compare the depth estimates obtained through the passive seismic method with those derived from borehole data.

Saltés-1, the easternmost borehole, reached the geological basement at an elevation of -560 m (meters above the sea level), while the passive seismic sampling point

HU42, located vertically above it, estimated a mechanical basement depth of -494 m. In the case of

Huelva-1, which reached -603 m for the geological basement,

HU41 estimated a depth of -500 m for the geological basement. Lastly, the

Moguer-1 and

Mazagón-1 boreholes reached the basement at -679 m, whereas

HVAME16 estimated a mechanical basement depth of -585 m. For the Aznalcóllar case, a similar pattern was observed, with an estimated depth discrepancy of approximately 30–50 meters above the actual geological basement depth (see

Figure 10). As previously mentioned, this discrepancy may be attributed to the Niebla calcarenites, which outcrop in the northern part of the study area and have been confirmed to extend in depth through borehole data [

18]. This formation, although it is part of the basin filling, behaves as a mechanically rigid substrate, contrasting with the softer basin sediments. The observed 30-meter error in the northern zone and the approximately 100-meter discrepancy further into the basin could be related to the increasing thickness of this material toward the basin interior, with the actual geological basement lying between 30 and 100 meters below the estimated mechanical basement.

A separate discussion is warranted for boreholes located deeper within the basin, where geological basement depths exceed -1000 m. The passive seismic method typically operates at frequencies ranging from 0.2 to 20 Hz, corresponding to a maximum depth of approximately 850 meters (based on empirical formula). Thus, at such depths, the method could not reach the mechanical basement. However, in a nearby area, as shown in

Figure 8, a well-defined depth of approximately -660 m has been identified (see

ARNO in

Table A1 in appendix). This suggests the presence of a fault with significant throw toward the southeast, which could explain the substantial depth variation between these points.

Lastly, the Almonte-1 borehole, located further north, reached the geological basement at approximately -620 m—significantly deeper than the depth estimated by the seismic method. However, this borehole is situated between two fault systems identified in geological mapping, which correspond well with changes in the curvature of the depth isolines and are referenced by only a few nearby data points. This region is of particular interest, as borehole data indicate a former structural high (characterized by a thinner sedimentary cover compared to adjacent boreholes and the absence of certain units, such as the Guadalquivir sands). This elevated structure, along with those identified along the eastern margin of the Guadiamar and the western margin of the Guadalquivir, may represent active tectonic features that could have influenced the Guadalquivir River course and its progressive eastward migration. The presence of olistostrome bodies in boreholes further east from the study area (Villamanrique de la Condesa to the south) also suggests that the Miocene orogenic front was previously located further west, with the Guadalquivir Basin shifting over time. Future surveys should aim to increase data density in this area and extend measurements toward the Guadalquivir to enhance the depth model.

A similar approach was later applied in the Aznalcóllar area using boreholes provided by various companies operating in the area (see

Figure 10), revealing a similar pattern with minor discrepancy —of around 30 meters—between HVSR-derived estimates and borehole measurements.

Figure 10.

Comparison of depth maps (generated through kriging interpolation) between passive seismic data (left) and exploration borehole data (right).

Figure 10.

Comparison of depth maps (generated through kriging interpolation) between passive seismic data (left) and exploration borehole data (right).

5.3. 3-D Architecture

Figure 11. Composite figure of satellite image (top), geological map with data derived from interpolation of seismic noise measurements (Figure 45, middle), and 3D model derived from these data (bottom) of the westernmost sector of the Guadalquivir Basin.

The morphology of the mechanical basement in the westernmost sector of the Guadalquivir Basin (considering that the Variscan basement should be located a few tens meters below it) is illustrated in Figure 11.

As shown, the interpretations derived from all observations align well with the surface morphology and geology, presenting a general slope towards the southeast, from very shallow or even outcropping basement materials in the west, to deep basements in the east (depths greater than 600 m). Sudden changes in slope are systematically located along the riverbeds, aligning approximately in NE-SW directions (Piedras, Odiel, and Tinto rivers) or NNE-SSW directions (Guadiamar).

In summary, the relief of the western end of the Guadalquivir basin can be explained by the development of structures that create a horst and graben landscape, with the horsts located in areas such as the Cabezos de Huelva and other topographically higher zones (as can be also in the eastern end of the Guadiamar), and the grabens being associated with the river marshes. These structures could be explained by the accommodation of deformation caused by the advance of the Alpine orogenic front (the Betics) in the forebulge region, significantly distanced from the front itself.

6. Conclusions

Seismic noise measurements were conducted at 334 discrete sampling points in the southwestern end of the Guadalquivir Basin to apply the Horizontal-to-Vertical Spectral Ratio (HVSR) method. The data presented in this study indicate that both the geological and mechanical basement are aligned along an azimuth of N070ºE and exhibit a gentle southeastward dip, oriented toward the Alpine orogenic front. This structural surface is disrupted by north-trending fault systems. The integration of 334 data points distributed over an area slightly exceeding 2300 km2 has enabled the construction of a three-dimensional model that delineates first-order reference surfaces relevant to basin architecture— such as, conceptually, the sedimentary fill interface or basin wall.

Furthermore, the incorporation of seismic noise data along NW-SE-oriented profiles permits the identification of variations in the dip of the mechanical basement in two-dimensional cross-sections. Borehole data suggest that similar structural variations may also be present in the geological basement, providing additional support for the observed subsurface heterogeneities.

A new empirical relationship was developed for the southwestern Guadalquivir Basin by integrating data from the HVSR method, seismic array techniques (5 datasets), reflection seismics (2 datasets), and mechanical boreholes (2 datasets) that reached the bedrock. This relationship, expressed as h=80.16·f0-1.48, enabled the determination of the mechanical basement depth, the Tortonian paleotopography, and the presence of potential fractures influencing current topography.

The geological basement reaches depths exceeding 600 m near Mazagón and Villamanrique de la Condesa, located in the southeastern part of the study area. The estimated dip of the basement surface is approximately 1–3º southeastward, with slope breaks coinciding with fluvial courses. The main structural trend follows a N070ºE orientation, aligning with the basement-cover contact.

The HVSR spectral ratio method yielded five distinct response types: (i) high-frequency peaks or (ii) no response, associated with shallow or outcropping basement in the northwestern sector; (iii) low-frequency peaks in the southeastern sector, indicative of deep-seated basement; (iv) double peaks in marshland areas; and (v) broad peaks, characteristic of irregular basement surfaces, potentially corresponding to fault zones.

The presence of sites exhibiting at least two peaks in the H/V spectral ratio may reflect not only contrasts in the mechanical behavior of the materials composing the subsurface at those locations, but also potential lithological changes. These double peaks could indicate the presence of different materials within the basin fill itself. As such, the detailed analysis of these features warrants particular attention in future investigations.

Passive seismic results show strong consistency with surface geological observations and depth estimations. Borehole data validated these depth estimations, with minor discrepancies ranging from 30 to 100 m, likely due to the presence of mechanically rigid units such as the Niebla calcarenites.

Two main hypotheses are proposed to explain abrupt slope changes: (i) they may represent ancient fluvial terraces formed by the eastward migration of the Guadalquivir River since the Miocene, or (ii) they may be related to fault activity controlling surface

relief including the orientation and flow direction of rivers. The alignment of broad seismic peaks with mapped fault zones supports the latter hypothesis, suggesting active or reactivated fault structures.

At depths greater than 800 m, the HVSR method presents limitations; however, the strong variations in basement depth suggest significant faulting in the southeastern sector of the study area.

The interpreted basement morphology reveals a horst and graben system, with structural highs corresponding to elevated areas (e.g., to the west of the Odiel estuary, Cabezos de Huelva, east of the Tinto estuary, or in the Aljarafe area in Seville) and depressions associated with river marshes in the northern margin of the Gulf of Cadiz, including the marshes of Odiel, Tinto and Doñana, among others.

The observed structural configuration is likely attributable to lithospheric flexure, facilitating upper-crustal extension. This tectonic regime is consistent with deformation expected in a forebulge setting, associated with the northern segment of the Gibraltar Arc in response to the propagation of the Alpine orogenic front.

Given the structural complexity of the western Guadalquivir Basin, future research should focus on increasing data density, particularly in northeastern areas where borehole data indicate structural highs or anomalies. Additional passive seismic surveys, complemented by geophysical techniques and detailed geological mapping, will be essential to refine the depth model and improve understanding of the tectonic evolution of the region.

Moreover, the methodology developed in this study opens new avenues for research across various branches of Earth Sciences. In particular, it shows strong potential for application in hydrocarbon exploration, where it could serve as a preliminary tool for identifying potential structural traps and fault systems, including blind faults. Notably, the Cobre Las Cruces deposit—one of the most significant copper deposits globally—was discovered within the study area, beneath the sedimentary fill of the Guadalquivir Basin and rooted in the Variscan basement. This technique could therefore prove highly usefull in the identification of similar new buried mineral deposits.

Geophysical anomalies, including gravimetric data, combined with the application of the H/V spectral ratio technique, may offer an effective approach for delineating the geometry of sedimentary fills that overlie geologically prospective zones. Additionally, the areas provide valuable input for seismic vulnerability assessments of infrastructure. This is particularly relevant in seismically active regions such as the San Vicente Transpressive Zone (see [

43]), where the occurrence of high-magnitude earthquakes remains a plausible scenario.

To sum up, the generation of three-dimensional maps of the bedrock surface, the recognition of blind faults, along with the determination of soil fundamental frequencies, would enable the development of more detailed hazard maps in areas of high seismic and tsunamigenic risk—such as the study area. Given its simplicity, versatility, rapid data acquisition, low cost, and reliable results, this technique has the potential to become a powerful tool across a range of applications. While its utility in geological studies is demonstrated in the present work, it also holds significant promise for other fields such as civil engineering, geotechnics, hydrocarbon industries and even mining.

Acknowledgments

David Amador Luna acknowledges the funding from the ‘Estrategia Política de Investigación y Transferencia’ (EPIT) of the University of Huelva for the predoctoral contract to promote the hiring of novice research personnel (EPIT20/00832), without which this work would not have been possible. We also would like to thank to ALERTES-RIM and “Analisis Multidisciplinar y multiescala de los mecanismos de localización y reparto de la deformación cortical en convergencia oblicua”, PGC2018-100914-B-I00, this study includes seismic noise recordings acquired during the development of these projects.

Appendix A

Appendix A.1

Table A1.

Summary table of the measurements conducted in the Guadalquivir Basin, including coordinates, fundamental frequency, estimated thickness, basement depth, and interpretation of the resulting HVSR curves.

Table A1.

Summary table of the measurements conducted in the Guadalquivir Basin, including coordinates, fundamental frequency, estimated thickness, basement depth, and interpretation of the resulting HVSR curves.

| STATION |

COORDINATES |

FUNDAMENTAL FREQUENCY (f0) (Hz) |

THICKNESS (m) |

ELEVATION (m) |

INTERPRETATION |

| LAT (°) |

LONG (°) |

| HVAME2 |

37.2888 |

-6.9326 |

0.74 |

125 |

-84 |

LOW F0 PEAK |

| HVAME3 |

37.2859 |

-6.9255 |

0.77 |

118 |

-79 |

LOW F0 PEAK |

| HVAME4 |

37.2817 |

-6.9108 |

0.71 |

133 |

-106 |

LOW F0 PEAK |

| HVAME10 |

37.2265 |

-6.9096 |

0.43 |

280 |

-276 |

TWO PEAKS |

| HVAME11 |

37.2202 |

-6.9057 |

0.38 |

336 |

-321 |

LOW F0 PEAK |

| HVAME12 |

37.2171 |

-6.8987 |

0.37 |

349 |

-311 |

LOW F0 PEAK |

| HVAME13 |

37.1654 |

-6.8418 |

0.28 |

527 |

-506 |

LOW F0 PEAK |

| HVAME14 |

37.2121 |

-6.8932 |

0.36 |

364 |

-345 |

LOW F0 PEAK |

| HVAME15 |

37.2151 |

-6.8977 |

0.38 |

336 |

-298 |

LOW F0 PEAK |

| HVAME5 |

37.2714 |

-6.8980 |

0.7 |

136 |

-127 |

LOW F0 PEAK |

| HVAME7 |

37.2391 |

-6.9268 |

0.47 |

245 |

-241 |

LOW F0 PEAK |

| HVAME8 |

37.2347 |

-6.9225 |

0.46 |

253 |

-246 |

LOW F0 PEAK |

| HVAME9 |

37.2472 |

-6.9346 |

0.5 |

224 |

-222 |

BROAD PEAK |

| HVAME16 |

37.1391 |

-6.8149 |

0.25 |

624 |

-585 |

LOW F0 PEAK |

| HVAME17 |

37.1975 |

-6.8746 |

0.33 |

414 |

-382 |

LOW F0 PEAK |

| HVAME18 |

37.2079 |

-6.8889 |

0.39 |

323 |

-319 |

TWO PEAKS |

| HVAME19 |

37.3162 |

-6.5948 |

0.44 |

270 |

-159 |

BROAD PEAK |

| HVAME20 |

37.3021 |

-6.6058 |

0.37 |

349 |

-246 |

LOW F0 PEAK |

| HVAME21 |

37.2910 |

-6.6163 |

0.33 |

414 |

-316 |

LOW F0 PEAK |

| HVAME22 |

37.2639 |

-6.6438 |

0.3 |

476 |

-376 |

LOW F0 PEAK |

| HVAME23 |

37.2365 |

-6.6689 |

0.29 |

501 |

-413 |

LOW F0 PEAK |

| HVAME24 |

37.2894 |

-7.0182 |

0.83 |

106 |

-74 |

LOW F0 PEAK |

| HVAME25 |

37.2861 |

-7.0071 |

0.75 |

123 |

-114 |

LOW F0 PEAK |

| HVAME26 |

37.2832 |

-6.9984 |

0.71 |

133 |

-120 |

BROAD PEAK |

| HVAME27 |

37.2820 |

-6.9937 |

0.62 |

163 |

-156 |

BROAD PEAK |

| HVAME28 |

37.1143 |

-6.7674 |

0.24 |

663 |

-619 |

LOW F0 PEAK |

| HVAME29 |

37.1781 |

-6.7219 |

0.27 |

557 |

-512 |

LOW F0 PEAK |

| HVAME30 |

37.2195 |

-6.6871 |

0.29 |

501 |

-429 |

LOW F0 PEAK |

| HVAME31 |

37.2664 |

-7.0064 |

0.76 |

120 |

-116 |

BROAD PEAK |

| HVAME32 |

37.2737 |

-7.0145 |

0.89 |

95 |

-91 |

BROAD PEAK |

| HVAME33 |

37.2755 |

-7.0293 |

1.35 |

51 |

-46 |

BROAD PEAK |

| HVAME34 |

37.2640 |

-7.0180 |

0.68 |

142 |

-132 |

BROAD PEAK |

| HVAME35 |

37.2680 |

-6.9864 |

0.56 |

189 |

-187 |

BROAD PEAK |

| HVAME36 |

37.2679 |

-6.9968 |

0.69 |

139 |

-136 |

BROAD PEAK |

| HVAME37 |

37.2702 |

-7.0029 |

0.8 |

112 |

-109 |

BROAD PEAK |

| HVAME38 |

37.2804 |

-6.9873 |

0.58 |

180 |

-174 |

LOW F0 PEAK |

| HVAME39 |

37.1533 |

-6.8994 |

0.31 |

454 |

-451 |

LOW F0 PEAK |

| HVAME40 |

37.1746 |

-6.9311 |

0.34 |

396 |

-393 |

TWO PEAKS |

| HVAME41 |

37.2049 |

-6.9522 |

0.38 |

336 |

-331 |

LOW F0 PEAK |

| HVAME42 |

37.1915 |

-6.9443 |

0.36 |

364 |

-361 |

LOW F0 PEAK |

| HVAME43 |

37.2134 |

-6.9660 |

0.39 |

323 |

-320 |

TWO PEAKS |

| HVAME44 |

37.2530 |

-6.9677 |

0.52 |

211 |

-207 |

TWO PEAKS |

| HVAME45 |

37.2257 |

-7.0604 |

0.56 |

189 |

-159 |

BROAD PEAK |

| HVAME46 |

37.2218 |

-7.0524 |

0.5 |

224 |

-211 |

BROAD PEAK |

| HVAME47 |

37.1989 |

-6.9804 |

0.37 |

349 |

-345 |

LOW F0 PEAK |

| HVAME48 |

37.1973 |

-6.9692 |

0.38 |

336 |

-331 |

LOW F0 PEAK |

| HVAME49 |

37.1724 |

-6.9509 |

0.33 |

414 |

-410 |

LOW F0 PEAK |

| HVAME50 |

37.1849 |

-6.9655 |

0.36 |

364 |

-359 |

LOW F0 PEAK |

| HVAME51 |

37.2985 |

-6.9427 |

1.17 |

64 |

-62 |

HIGH F0 PEAK |

| HVAME52 |

37.2329 |

-7.0664 |

0.58 |

180 |

-155 |

LOW F0 PEAK |

| HVAME53 |

37.2434 |

-7.0832 |

0.55 |

194 |

-156 |

LOW F0 PEAK |

| HVAME54 |

37.1952 |

-6.9947 |

0.39 |

323 |

-317 |

LOW F0 PEAK |

| HVAME55 |

37.1897 |

-6.9749 |

0.36 |

364 |

-359 |

LOW F0 PEAK |

| HVAME56 |

37.2584 |

-7.1073 |

0.93 |

89 |

-32 |

LOW F0 PEAK |

| HVAME57 |

37.2640 |

-7.1146 |

0.83 |

106 |

-46 |

LOW F0 PEAK |

| HVAME58 |

37.2046 |

-7.0267 |

0.42 |

289 |

-281 |

LOW F0 PEAK |

| HVAME59 |

37.2719 |

-7.1266 |

1.38 |

50 |

-32 |

HIGH F0 PEAK |

| HVAME60 |

37.2784 |

-7.1339 |

1.51 |

44 |

-20 |

BROAD PEAK |

| HVAME61 |

37.2975 |

-7.1619 |

1.69 |

37 |

-22 |

BROAD PEAK |

| HVAME62 |

37.3038 |

-7.1705 |

8.55 |

3 |

20 |

HIGH F0 PEAK |

| HVAME63 |

37.3060 |

-7.1755 |

4.05 |

10 |

23 |

HIGH F0 PEAK |

| HVAME64 |

37.3124 |

-7.1861 |

- |

- |

33 |

ROCK |

| HVAME65 |

37.3194 |

-7.1936 |

5.39 |

7 |

56 |

HIGH F0 PEAK |

| HVAME66 |

37.3178 |

-7.0867 |

1.59 |

40 |

16 |

HIGH F0 PEAK |

| HVAME67 |

37.2663 |

-6.8902 |

0.62 |

163 |

-152 |

LOW F0 PEAK |

| HVAME68 |

37.2489 |

-7.0930 |

0.65 |

152 |

-120 |

LOW F0 PEAK |

| HVAME69 |

37.2553 |

-7.0979 |

0.81 |

109 |

-69 |

BROAD PEAK |

| HVAME70 |

37.2824 |

-7.1416 |

1.5 |

44 |

-18 |

BROAD PEAK |

| HVAME71 |

37.2924 |

-7.1550 |

1.37 |

50 |

-25 |

TWO PEAKS |

| HU1 |

37.2746 |

-6.9403 |

0.62 |

163 |

-98 |

LOW F0 PEAK |

| HU2 |

37.2725 |

-6.9404 |

0.6 |

171 |

-123 |

LOW F0 PEAK |

| HU3 |

37.2779 |

-6.9464 |

0.77 |

118 |

-97 |

BROAD PEAK |

| HU4 |

37.2739 |

-6.9535 |

0.76 |

120 |

-117 |

LOW F0 PEAK |

| HU5 |

37.2693 |

-6.9621 |

0.66 |

148 |

-146 |

TWO PEAKS |

| HU6 |

37.2502 |

-6.9436 |

0.5 |

224 |

-223 |

BROAD PEAK |

| HU7 |

37.2709 |

-6.9254 |

0.67 |

145 |

-125 |

LOW F0 PEAK |

| HU8 |

37.2793 |

-6.9386 |

0.65 |

152 |

-102 |

INDETERMINED |

| HU9 |

37.2764 |

-6.9361 |

0.66 |

148 |

-108 |

LOW F0 PEAK |

| HU10 |

37.2717 |

-6.9332 |

0.62 |

163 |

-132 |

LOW F0 PEAK |

| HU11 |

37.2735 |

-6.9306 |

0.66 |

148 |

-119 |

LOW F0 PEAK |

| HU12 |

37.2787 |

-6.9506 |

0,86 |

100 |

-95 |

BROAD PEAK |

| HU13 |

37.2758 |

-6.9498 |

0.81 |

109 |

-103 |

BROAD PEAK |

| HU14 |

37.2684 |

-6.9552 |

0.67 |

145 |

-141 |

TWO PEAKS |

| HU15 |

37.2602 |

-6.9601 |

0.55 |

194 |

-190 |

BROAD PEAK |

| HU16 |

37.2549 |

-6.9579 |

0.55 |

194 |

-190 |

TWO PEAKS |

| HU17 |

37.2607 |

-6.9272 |

0.54 |

200 |

-193 |

LOW F0 PEAK |

| HU18 |

37.2577 |

-6.9253 |

0.52 |

211 |

-205 |

LOW F0 PEAK |

| HU19 |

37.2605 |

-6.9227 |

0.55 |

194 |

-188 |

LOW F0 PEAK |

| HU20 |

37.2561 |

-6.9302 |

0.5 |

224 |

-216 |

LOW F0 PEAK |

| HU21 |

37.2535 |

-6.9351 |

0.47 |

245 |

-235 |

LOW F0 PEAK |

| HU22 |

37.2522 |

-6.9380 |

0.46 |

253 |

-249 |

LOW F0 PEAK |

| HU23 |

37.2583 |

-6.9358 |

0.48 |

238 |

-222 |

LOW F0 PEAK |

| HU24 |

37.2599 |

-6.9385 |

0.48 |

238 |

-219 |

LOW F0 PEAK |

| HU25 |

37.2664 |

-6.9390 |

0.53 |

205 |

-173 |

LOW F0 PEAK |

| HU26 |

37.2639 |

-6.9393 |

0.5 |

224 |

-194 |

LOW F0 PEAK |

| HU27 |

37.2693 |

-6.9302 |

0.61 |

167 |

-141 |

LOW F0 PEAK |

| HU28 |

37.2674 |

-6.9462 |

0.53 |

205 |

-158 |

LOW F0 PEAK |

| HU29 |

37.2742 |

-6.9454 |

0.61 |

167 |

-100 |

LOW F0 PEAK |

| HU30 |

37.2649 |

-6.9512 |

0.53 |

205 |

-198 |

LOW F0 PEAK |

| HU31 |

37.2624 |

-6.9457 |

0,5 |

224 |

-184 |

LOW F0 PEAK |

| HU32 |

37.2605 |

-6.9452 |

0.49 |

230 |

-196 |

LOW F0 PEAK |

| HU33 |

37.2513 |

-6.9567 |

0.48 |

238 |

-235 |

BROAD PEAK |

| HU34 |

37.2642 |

-6.9582 |

0.54 |

200 |

-197 |

BROAD PEAK |

| HU35 |

37.2811 |

-6.9412 |

0.71 |

133 |

-106 |

BROAD PEAK |

| HU36 |

37.2784 |

-6.9280 |

0.69 |

139 |

-106 |

LOW F0 PEAK |

| HU37 |

37.2619 |

-6.9474 |

0.5 |

224 |

-191 |

LOW F0 PEAK |

| HU38 |

37.2578 |

-6.9469 |

0.48 |

238 |

-199 |

BROAD PEAK |

| HU39 |

37.2578 |

-6.9489 |

0.48 |

238 |

-212 |

LOW F0 PEAK |

| HU40 |

37.1774 |

-6.7842 |

0.27 |

557 |

-500 |

LOW F0 PEAK |

| HU41 |

37.1774 |

-6.7842 |

0.27 |

557 |

-500 |

LOW F0 PEAK |

| HU42 |

37.1446 |

-6.8867 |

0.29 |

501 |

-494 |

LOW F0 PEAK |

| G9-10 HU3 |

37.2440 |

-6.9662 |

0.5 |

224 |

-222 |

TWO PEAKS |

| G25-26 HU3 |

37.2439 |

-6.9667 |

0.48 |

238 |

-236 |

TWO PEAKS |

| G40 HU3 |

37.2439 |

-6.9671 |

0.5 |

224 |

-222 |

TWO PEAKS |

| R0S1 |

37.2503 |

-6.9504 |

0.44 |

270 |

-266 |

TWO PEAKS |

| R1S2 |

37.2504 |

-6.9506 |

0.46 |

253 |

-249 |

TWO PEAKS |

| R1S3 |

37.2505 |

-6.9502 |

0.47 |

245 |

-241 |

TWO PEAKS |

| R1S4 |

37.2501 |

-6.9503 |

0.46 |

253 |

-249 |

TWO PEAKS |

| R2S5 |

37.2507 |

-6.9505 |

0.38 |

336 |

-331 |

LOW F0 PEAK |

| R2S6 |

37.2502 |

-6.9498 |

0.47 |

245 |

-241 |

TWO PEAKS |

| R2S7 |

37.2500 |

-6.9507 |

0.47 |

245 |

-241 |

LOW F0 PEAK |

| R3S2 |

37.2507 |

-6.9514 |

0.48 |

238 |

-234 |

LOW F0 PEAK |

| R3S3 |

37.2509 |

-6.9495 |

0.46 |

253 |

-249 |

LOW F0 PEAK |

| R3S4 |

37.2494 |

-6.9501 |

0.47 |

245 |

-240 |

LOW F0 PEAK |

| R4S5 |

37.2523 |

-6.9514 |

0.49 |

230 |

-227 |

LOW F0 PEAK |

| R4S6 |

37.2496 |

-6.9479 |

0.47 |

245 |

-241 |

LOW F0 PEAK |

| R4S7 |

37.2488 |

-6.9528 |

0.48 |

238 |

-234 |

LOW F0 PEAK |

| R5S2 |

37.2505 |

-6.9547 |

0.44 |

270 |

-266 |

BROAD PEAK |

| R5S3 |

37.2528 |

-6.9474 |

0.43 |

280 |

-275 |

BROAD PEAK |

| R5S4 |

37.2467 |

-6.9494 |

0.48 |

238 |

-234 |

BROAD PEAK |

| R0S1 |

37.2696 |

-6.9232 |

0.64 |

155 |

-140 |

LOW F0 PEAK |

| R1S2 |

37.2696 |

-6.9230 |

0.65 |

152 |

-137 |

LOW F0 PEAK |

| R1S3 |

37.2698 |

-6.9233 |

0.66 |

148 |

-133 |

LOW F0 PEAK |

| R1S4 |

37.2695 |

-6.9235 |

0.66 |

148 |

-133 |

LOW F0 PEAK |

| R2S5 |

37.2699 |

-6.9228 |

0.65 |

152 |

-137 |

LOW F0 PEAK |

| R2S6 |

37.2697 |

-6.9238 |

0.64 |

155 |

-139 |

LOW F0 PEAK |

| R2S7 |

37.2692 |

-6.9231 |

0.64 |

155 |

-140 |

LOW F0 PEAK |

| R3S2 |

37.2694 |

-6.9221 |

0.64 |

155 |

-141 |

LOW F0 PEAK |

| R3S3 |

37.2705 |

-6.9234 |

0.66 |

148 |

-132 |

LOW F0 PEAK |

| R3S4 |

37.2691 |

-6.9241 |

0.64 |

155 |

-139 |

LOW F0 PEAK |

| R4S5 |

37.2711 |

-6.9214 |

0.67 |

145 |

-131 |

LOW F0 PEAK |

| R4S6 |

37.2703 |

-6.9259 |

0.64 |

155 |

-134 |

LOW F0 PEAK |

| R4S7 |

37.2673 |

-6.9226 |

0.63 |

159 |

-146 |

LOW F0 PEAK |

| R0S1 |

37.2659 |

-6.9295 |

0.58 |

180 |

-163 |

LOW F0 PEAK |

| R1S2 |

37.2660 |

-6.9292 |

0.57 |

184 |

-167 |

LOW F0 PEAK |

| R1S3 |

37.2661 |

-6.9297 |

0.58 |

180 |

-162 |

LOW F0 PEAK |

| R1S4 |

37.2657 |

-6.9295 |

0.57 |

184 |

-168 |

LOW F0 PEAK |

| R2S5 |

37.2664 |

-6.9294 |

0.58 |

180 |

-161 |

LOW F0 PEAK |

| R2S6 |

37.2656 |

-6.9292 |

0.58 |

180 |

-164 |

LOW F0 PEAK |

| R2S7 |

37.2658 |

-6.9300 |

0.58 |

180 |

-164 |

LOW F0 PEAK |

| R3S2 |

37.2662 |

-6.9284 |

0.58 |

180 |

-163 |

LOW F0 PEAK |

| R3S3 |

37.2665 |

-6.9303 |

0.58 |

180 |

-161 |

LOW F0 PEAK |

| R3S4 |

37.2650 |

-6.9299 |

0.56 |

189 |

-175 |

LOW F0 PEAK |

| R0S1 |

37.2775 |

-6.9251 |

0.68 |

142 |

-122 |

LOW F0 PEAK |

| R1S2 |

37.2776 |

-6.9248 |

0.68 |

142 |

-122 |

LOW F0 PEAK |

| R1S3 |

37.2776 |

-6.9253 |

0.68 |

142 |

-121 |

LOW F0 PEAK |

| R1S4 |

37.2772 |

-6.9251 |

0.69 |

139 |

-119 |

LOW F0 PEAK |

| R2S5 |

37.2779 |

-6.9250 |

0.68 |

142 |

-121 |

LOW F0 PEAK |

| R2S6 |

37.2772 |

-6.9247 |

0.69 |

139 |

-120 |

LOW F0 PEAK |

| R2S7 |

37.2773 |

-6.9257 |

0.68 |

142 |

-118 |

LOW F0 PEAK |

| HU43 |

37.2898 |

-6.9889 |

0.83 |

106 |

-93 |

BROAD PEAK |

| HU44 |

37.2928 |

-6.9943 |

0.97 |

84 |

-68 |

LOW F0 PEAK |

| HU46 |

37.2935 |

-7.0013 |

0.95 |

86 |

-68 |

BROAD PEAK |

| HU47 |

37.2951 |

-7.0085 |

1.06 |

74 |

-51 |

BROAD PEAK |

| HU48 |

37.2956 |

-7.0154 |

1 |

80 |

-67 |

BROAD PEAK |

| HU49 |

37.2680 |

-6.9497 |

0.55 |

194 |

-180 |

BROAD PEAK |

| HU50 |

37.2597 |

-6.9552 |

0.53 |

205 |

-202 |

BROAD PEAK |

| HU51 |

37.2629 |

-6.9345 |

0.52 |

211 |

-187 |

LOW F0 PEAK |

| HU52 |

37.2562 |

-6.9539 |

0.5 |

224 |

-218 |

BROAD PEAK |

| HU53 |

37.2547 |

-6.9406 |

0.46 |

253 |

-239 |

LOW F0 PEAK |

| HU54 |

37.2566 |

-6.9470 |

0.48 |

238 |

-228 |

LOW F0 PEAK |

| Odiel1 |

37.2837 |

-6.9497 |

0.88 |

97 |

-95 |

BROAD PEAK/TWO PEAKS |

| Odiel2 |

37.2836 |

-6.9501 |

0.91 |

92 |

-90 |

BROAD PEAK/TWO PEAKS |

| Odiel3 |

37.2835 |

-6.9503 |

0.89 |

95 |

-93 |

BROAD PEAK/TWO PEAKS |

| R0S1 |

37.2738 |

-6.9306 |

0.65 |

152 |

-124 |

LOW F0 PEAK |

| R1S2 |

37.2740 |

-6.9304 |

0.65 |

152 |

-124 |

LOW F0 PEAK |

| R1S3 |

37.2735 |

-6.9306 |

0.65 |

152 |

-123 |

LOW F0 PEAK |

| R1S4 |

37.2738 |

-6.9308 |

0.65 |

152 |

-123 |

LOW F0 PEAK |

| R2S5 |

37.2742 |

-6.9309 |

0.65 |

152 |

-123 |

LOW F0 PEAK |

| R2S6 |

37.2737 |

-6.9301 |

0.65 |

152 |

-124 |

LOW F0 PEAK |

| R2S7 |

37.2734 |

-6.9311 |

0.64 |

155 |

-124 |

LOW F0 PEAK |

| R3S2 |

37.2743 |

-6.9298 |

0.66 |

148 |

-121 |

LOW F0 PEAK |

| R3S3 |

37.2729 |

-6.9305 |

0.65 |

152 |

-123 |

LOW F0 PEAK |

| R3S4 |

37.2737 |

-6.9317 |

0.66 |

148 |

-117 |

LOW F0 PEAK |

| ARNO-G12 (L1) |

37.0991 |

-6.7319 |

0.23 |

706 |

-660 |

LOW F0 PEAK |

| ARNO-G12 (L2) |

37.0989 |

-6.7326 |

0.23 |

706 |

-661 |

LOW F0 PEAK |

| ARNO-G2 (L1) |

37.0988 |

-6.7321 |

0.24 |

663 |

-661 |

LOW F0 PEAK |

| WALJ_09 |

37.2468 |

-7.0293 |

0.53 |

205 |

-188 |

BROAD PEAK |

| RIN_15 |

37.2360 |

-7.0309 |

0.51 |

220 |

-199 |

BROAD PEAK |

| RIN_14 |

37.2384 |

-7.0329 |

0.51 |

220 |

-211 |

BROAD PEAK |

| RIN_13 |

37.2430 |

-7.0400 |

0.57 |

183 |

-146 |

BROAD PEAK |

| RIN_07 |

37.2588 |

-7.0584 |

0.75 |

123 |

-88 |

LOW F0 PEAK |

| RIN_08 |

37.2572 |

-7.0560 |

0.73 |

129 |

-96 |

LOW F0 PEAK |

| WALJ_01 |

37.2652 |

-7.0370 |

0.66 |

148 |

-112 |

BROAD PEAK |

| WALJ_02 |

37.2628 |

-7.0362 |

0.53 |

203 |

-176 |

BROAD PEAK |

| WALJ_03 |

37.2611 |

-7.0354 |

0.52 |

211 |

-188 |

BROAD PEAK |

| WALJ_04 |

37.2594 |

-7.0346 |

0.56 |

187 |

-165 |

BROAD PEAK |

| WALJ_06 |

37.2565 |

-7.0336 |

0.51 |

217 |

-197 |

BROAD PEAK |

| WALJ_05 |

37.2574 |

-7.0340 |

0.51 |

217 |

-192 |

BROAD PEAK |

| WALJ_07 |

37.2552 |

-7.0333 |

0.48 |

241 |

-211 |

BROAD PEAK/TWO PEAKS |

| WALJ_08 |

37.2536 |

-7.0326 |

0.49 |

228 |

-212 |

BROAD PEAK/TWO PEAKS |

| EALJ_01.5 |

37.2743 |

-7.0167 |

1.10 |

70 |

-66 |

BROAD PEAK |

| EALJ_02.5 |

37.2695 |

-7.0156 |

1.01 |

79 |

-75 |

BROAD PEAK |

| EALJ_03 |

37.2681 |

-7.0120 |

0.78 |

116 |

-111 |

BROAD PEAK/TWO PEAKS |

| EALJ_03.5 |

37.2666 |

-7.0110 |

0.77 |

117 |

-112 |

BROAD PEAK/TWO PEAKS |

| EALJ_04 |

37.2656 |

-7.0078 |

0.75 |

122 |

-112 |

BROAD PEAK |

| EALJ_05 |

37.2644 |

-7.0067 |

0.74 |

126 |

-115 |

BROAD PEAK/TWO PEAKS |

| RIN_12 |

37.2455 |

-7.0419 |

0.52 |

212 |

-189 |

BROAD PEAK |

| RIN_11 |

37.2481 |

-7.0455 |

0.51 |

215 |

-188 |

BROAD PEAK |

| RIN_10 |

37.2507 |

-7.0483 |

0.57 |

185 |

-167 |

BROAD PEAK |

| RIN_01 |

37.2996 |

-7.1075 |

1.40 |

49 |

-4 |

BROAD PEAK |

| RIN_02 |

37.2924 |

-7.0990 |

1.14 |

66 |

-37 |

TWO PEAKS |

| RIN_03 |

37.2854 |

-7.0918 |

1.01 |

79 |

-40 |

LOW F0 PEAK |

| RIN_04 |

37.2761 |

-7.0797 |

0.67 |

145 |

-78 |

LOW F0 PEAK |

| RIN_05 |

37.2675 |

-7.0688 |

0.72 |

129 |

-84 |

BROAD PEAK |

| RIN_09 |

37.2531 |

-7.0514 |

0.60 |

171 |

-150 |

BROAD PEAK |

| CEP_13A |

37.2480 |

-7.0916 |

0.63 |

157 |

-128 |

LOW F0 PEAK |

| CEP_13B |

37.2451 |

-7.0877 |

0.56 |

191 |

-150 |

LOW F0 PEAK |

| CEP_14A |

37.2391 |

-7.0782 |

0.62 |

163 |

-134 |