1. Introduction

The Mediterranean basin is recognised as one of the most climate-vulnerable regions globally, facing increasing pressure from prolonged droughts, rising temperatures, water scarcity and the dependence on fossil fuel imports [

1,

2]. These challenges are compounded by a high population density and the production of significant volumes of organic waste derived from agricultural, livestock, agro-industrial and urban sources [

3]. Such waste streams represent a largely untapped resource for renewable energy production within a Circular Bioeconomy (CBE) framework.

Anaerobic Digestion (AD) is a mature and scalable technology that enables the conversion of organic substrates into biogas and digestate. Biogas can be used for Combined Heat and Power (CHP) plants or upgraded into biomethane, a renewable substitute for natural gas suitable for injection into the grid or as a transport fuel [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8]. This transition supports the reduction of Greenhouse Gas (GHG) emissions, enhances waste valorisation and improves energy independence [

9,

10].

Pioneering work by Comparetti et al. (2012) [

11] assessed energy recovery potentials from livestock and agro-industrial waste, laying the foundation for AD-based strategies in Mediterranean rural contexts. Attard et al. (2017) [

7] demonstrated the feasibility of integrating AD systems in Mediterranean islands, noting their alignment with regional renewable energy and waste management goals. More recently, Greco et al. (2022) [

12] emphasised the socio-economic and environmental benefits of small-scale biowaste AD plants, especially in urban-rural transition areas.

Supporting this paradigm, Greco et al. (2019a) [

13] explored manure pyrolysis as a complementary valorisation pathway, while Comparetti et al. (2017) [

14] and Greco et al., (2019b) [

15] highlighted nutrient recycling from cactus pear residues. Further studies by Campiotti et al. (2019) [

16] affirmed the importance of renewable energy, including biomethane, in sustainable greenhouse production systems.

Within this framework, biomethane not only emerges as a clean energy vector but also acts as a catalyst for integrated rural development when adopted in multifunctional farms [

8,

17]. Additionally, Greco et al. (2020, 2021) [

18,

19] demonstrated the role of compost and vermicompost derived from digestate as effective peat substitutes, thus closing the organic matter cycle and enhancing soil health.

Overall, biomethane production through Anaerobic Digestion stands out as a key enabler of sustainable energy transition, circularity and resilience in Mediterranean agri-food systems.

2. Biomethane Production Technologies

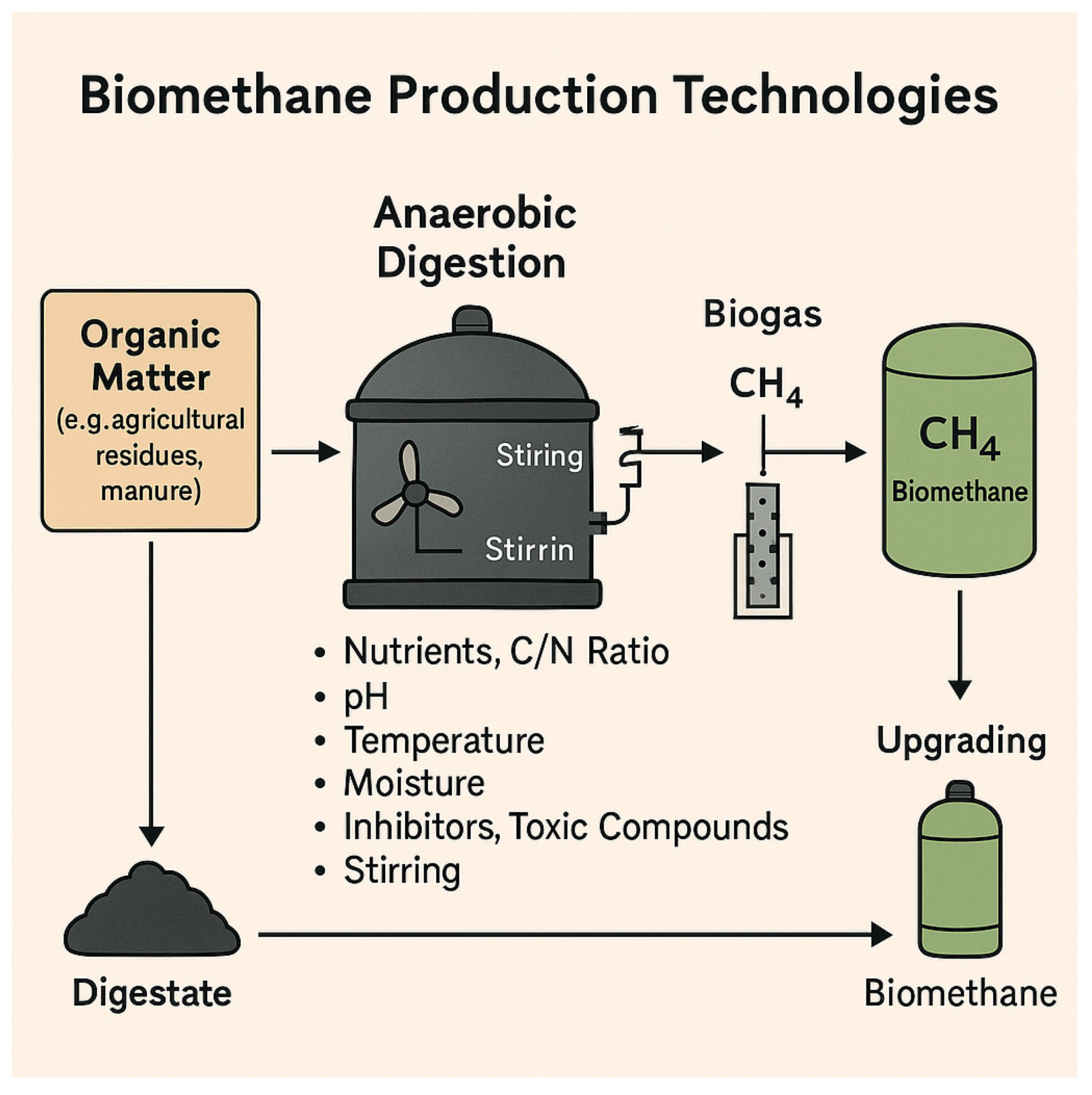

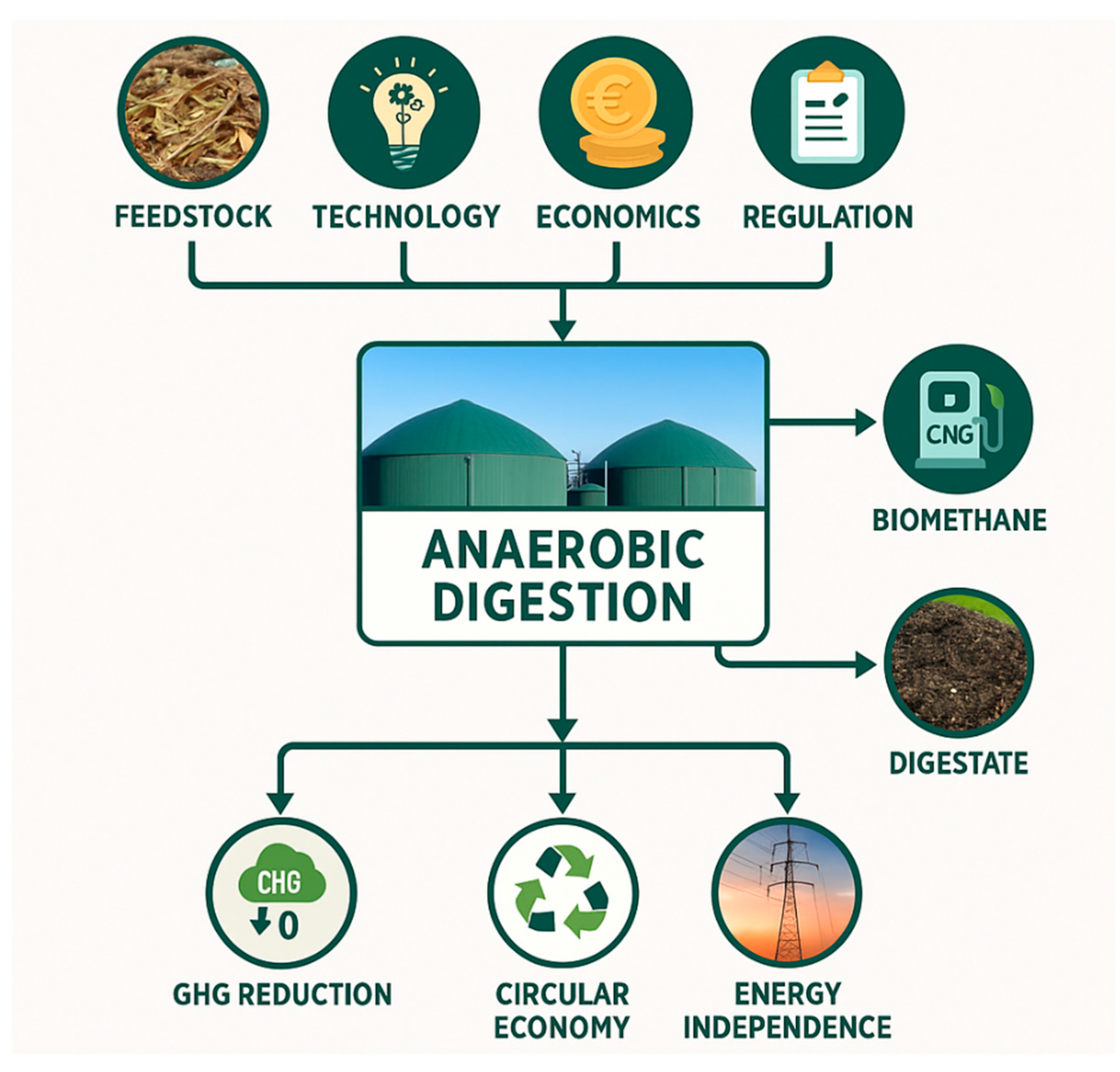

Biomethane production primarily relies on Anaerobic Digestion (AD), a consolidated and adaptable biotechnology capable of converting organic matter into biogas and digestate under oxygen-free conditions (

Figure 1).

The efficiency of the AD process is governed by multiple interdependent parameters. Key factors include the biochemical composition of the feedstock, particularly the balance of carbon and nitrogen (C/N ratio), as well as pH, Hydraulic Retention Time (HRT) and activity of microbial consortia responsible for hydrolysis, acidogenesis, acetogenesis and methanogenesis. Environmental temperature plays a critical role, with thermophilic digestion—operating at temperatures around 50–60°C—often preferred in Mediterranean region, due to climate conditions. Thermophilic systems have demonstrated faster reaction kinetics and enhanced pathogen reduction, although they require more stable operational control and energy input compared to mesophilic digestion [

20,

21].

Feedstock heterogeneity remains a major challenge in achieving optimal AD performance. Therefore, pre-treatment technologies are increasingly applied to improve the biodegradability of lignocellulosic substrates common in Mediterranean agricultural waste, such as straw, pruning residues and fruit-processing by-products. Techniques such as mechanical shredding, steam explosion, thermal hydrolysis and alkaline or acid chemical conditioning can effectively disrupt complex organic structures, increase surface area and enhance enzymatic accessibility, thereby increasing methane yield [

22,

23].

Moreover, co-digestion strategies have proven particularly effective in improving both process stability and methane yield. Combining livestock manure—which typically provides buffering capacity and microbial inoculum—with high-energy agro-industrial by-products such as olive mill wastewater, citrus peel or winery grape marc allows for improved nutrient balance and synergistic microbial interactions. These strategies not only optimise substrate characteristics but also facilitate integrated waste management in agro-industrial districts [

24,

25].

In addition to energy generation, digestate derived from AD systems holds agronomic value as a soil amendment, closing nutrient loops and contributing to Circular Bioeconomy. The dual benefit of waste valorisation and renewable gas production positions biomethane as a key enabler of climate-neutral strategies in Mediterranean farming systems, where distributed energy solutions and decentralised resource recovery are becoming increasingly vital under the pressures of climate change and energy transition policies [

3,

26].

Biogas is typically composed of 50–70% methane (CH₄) and 30–50% carbon dioxide (CO₂), with traces of hydrogen sulfide (H₂S), ammonia (NH₃), siloxanes and water vapour.

Biogas upgrading technologies are essential to convert raw biogas itself—— into high-purity biomethane, suitable as a renewable substitute for natural gas for grid injection or as a vehicle fuel. The upgrading process is primarily aimed at removing CO₂ and contaminants, as well as reducing other impurities that could damage end-use equipment or compromise pipeline standards.

The most widely applied upgrading technologies include Pressure Swing Adsorption (PSA), water scrubbing, chemical absorption using amines, membrane separation and cryogenic upgrading. PSA relies on differences in adsorption capacity to separate methane from other gases and is effective for plants with consistent gas flows. Water scrubbing is based on the physical solubility of CO₂ and H₂S in water and is widely used in small and medium-scale AD plants, due to its simplicity and moderate cost [

27,

28]. Amine scrubbing, a chemical absorption method, offers high purity and selectivity but it implies increased operational and maintenance costs, making it more suitable for large-scale plants.

Membrane separation has gained traction, due to modular design, energy efficiency and ease of integration. In this process, gas components are separated based on differential permeability across polymeric or ceramic membranes. The technology is particularly suitable for decentralised agricultural AD plants in Mediterranean region, where space constraints and cost-efficiency are priorities [

29,

30].

Cryogenic upgrading, involving the liquefaction of CO₂ and CH₄ at low temperatures, achieves high methane purity but it is energy-intensive and best suited for large-scale and centralised AD plants or for producing liquefied biomethane (Bio-LNG).

Emerging upgrading technologies are increasingly contributing to the viability of distributed biomethane production. Biological methanation, for instance, uses hydrogen and CO₂ conversion by archaea to produce methane, enabling power-to-gas applications and improving energy integration. Compact and containerised upgrading systems are now being adopted in small cooperative networks and multifunctional farms, providing modular and scalable solutions with minimal infrastructure investment [

31,

32]. These innovations make biomethane production more accessible to Mediterranean agricultural systems, where energy autonomy and resource valorisation are critical for sustainability.

3. Feedstocks in the Mediterranean Region

The Mediterranean region, characterised by a favourable agro-climatic setting and high agricultural biodiversity, offers a wide range of organic feedstocks suitable for biomethane production. The valorisation of such resources aligns with Circular Bioeconomy principles and supports sustainable rural development in areas often constrained by water scarcity, energy dependency and land fragmentation.

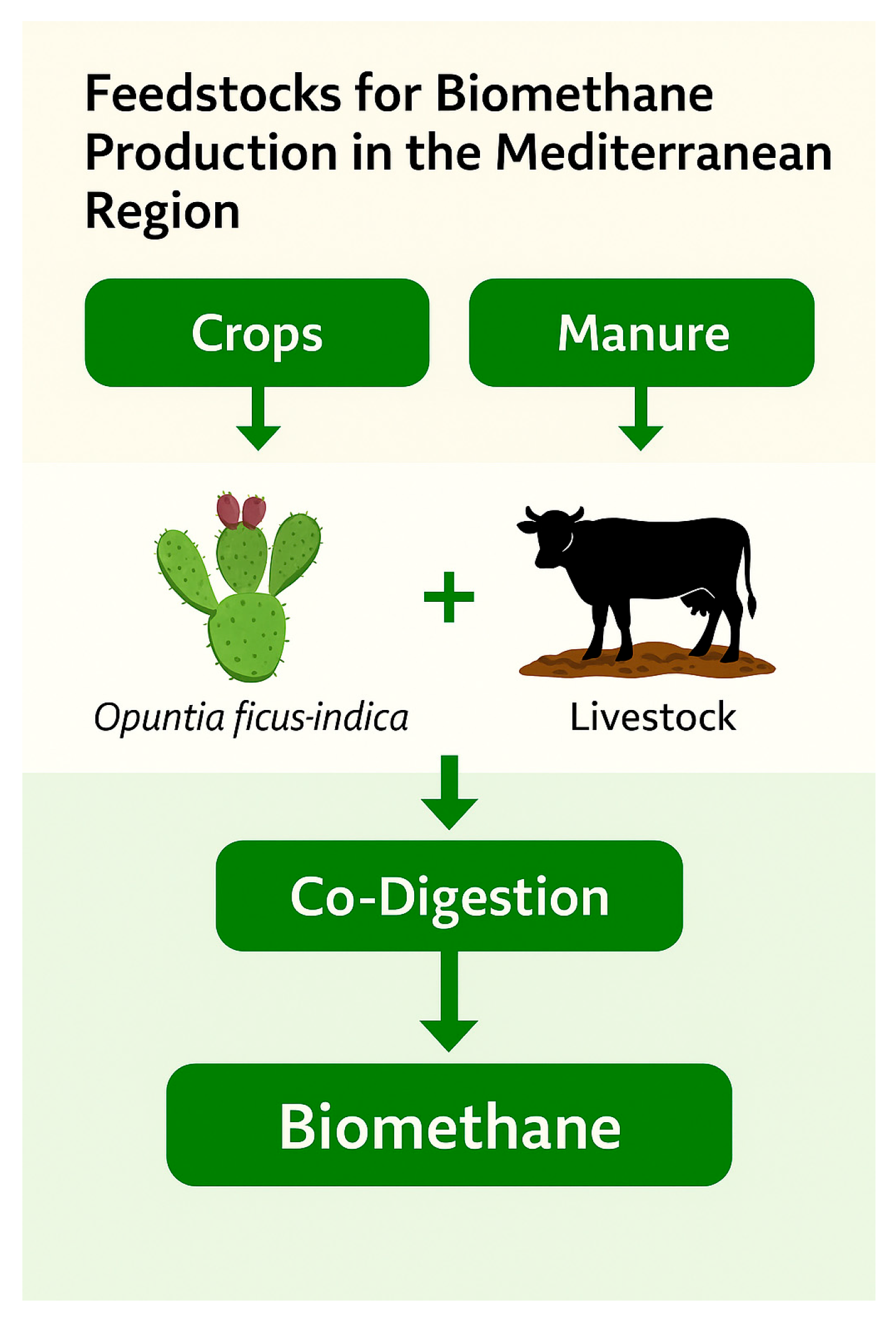

Crops like cactus pear (

Opuntia ficus-indica), an abundant CAM species well-adapted to arid Mediterranean conditions, have been investigated for their bioenergy potential. Comparetti et al. (2017) [

14] demonstrated that cladodes from

O. ficus-indica can serve as effective substrates for AD, producing both methane-rich biogas and nutrient-rich digestate suitable for soil amendment. Similarly, residual biomass from wine making cellars (grape marc), olive mills (pomace and wastewater) and citrus processing (peel) can be integrated into AD process, contributing to both waste reduction and decentralised energy generation [

33,

34].

Livestock manure remains a cornerstone substrate for AD, due to its stable composition and buffering capacity. Studies by Greco et al., (2019a) and Attard et al. (2023) [

13,

17] have confirmed the feasibility of manure-based biogas production in Mediterranean islands, highlighting not only its energy potential but also the co-benefits of pathogen reduction and nutrient recovery. Co-digestion strategies combining livestock manure with agro-industrial by-products, such as olive mill pomace and wastewater, grape marc or tomato processing waste, have been shown to enhance methane yield, due to improved substrate C/N balance and increased biodegradability [

35,

36].

Moreover, waste from fruit and vegetable markets, pruning biomass and even invasive plant species (e.g.

Ailanthus altissima) can be sustainably valorised via AD. Integrating these different substrates through local or cooperative-scale AD plants offers an opportunity for energy self-sufficiency, organic waste reduction and rural income diversification—key goals under EU renewable energy and Circular Bioeconomy frameworks [

3,

37].

These findings collectively support the view that strategic feedstock selection, especially via co-digestion, can optimise biomethane production, while fostering environmental, agronomic and socio-economic resilience across Mediterranean agroecosystems.

The Mediterranean region is rich in different biomass types for biomethane production (

Figure 2), whose most relevant sources are summarised in

Table 1.

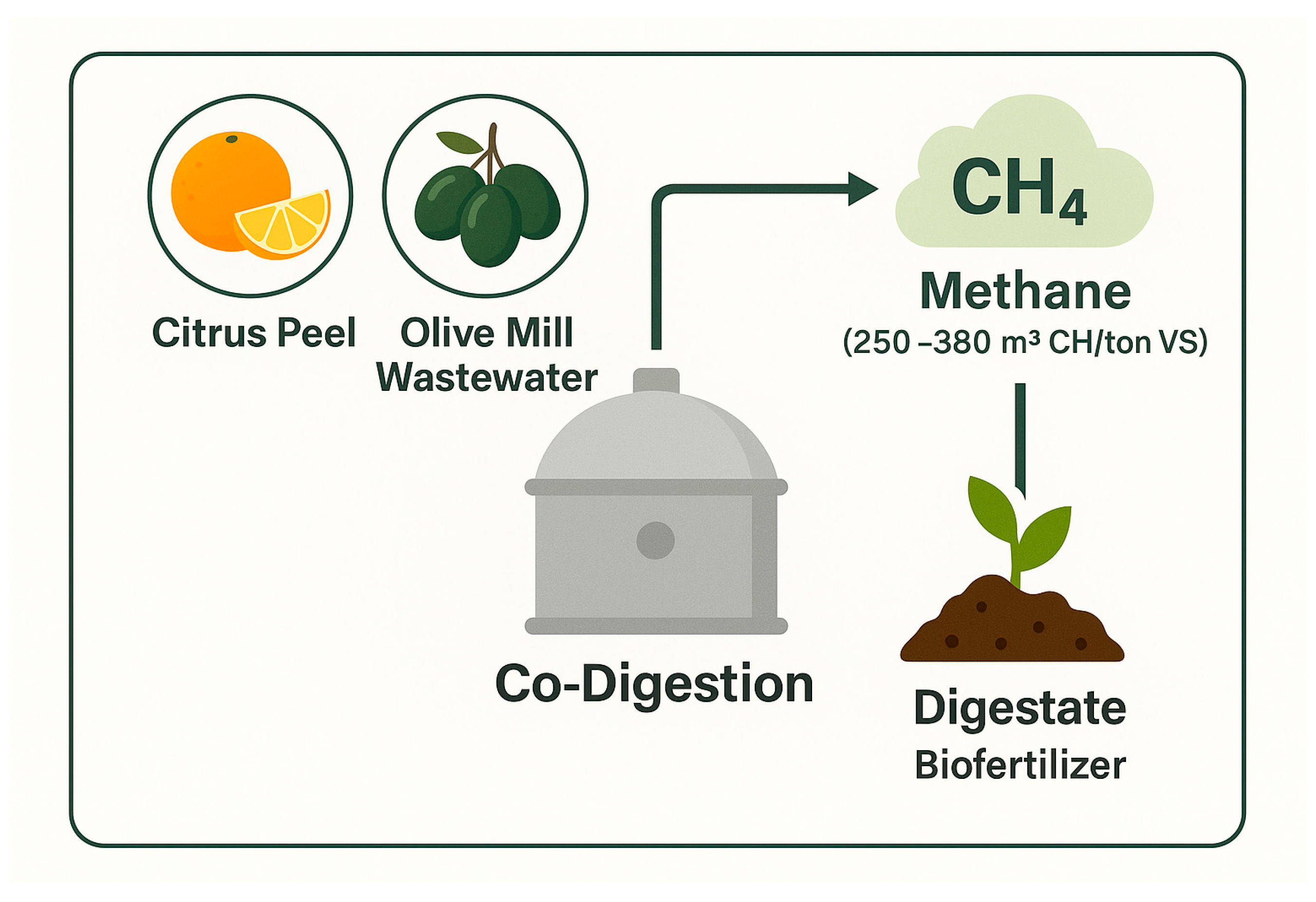

Recent studies have demonstrated promising methane yields—ranging from 250 to 380 m³ CH₄ per ton of Volatile Solids (VS)—from the co-digestion of citrus peel and olive mill wastewater, two abundant agro-industrial by-products in the Mediterranean region (

Figure 3). These by-products are rich in readily biodegradable organic compounds, including sugars, organic acids and essential oils. While their high biodegradability contributes to high biogas production, the presence of inhibitory compounds such as limonene in citrus peel and polyphenols in olive mill wastewater needs for careful process management or pre-treatment to avoid microbial inhibition [

38,

39]. Co-digestion with livestock manure or food waste has been shown to dilute toxic components, improve nutrient balance and enhance microbial diversity, thereby stabilising the AD process and increasing methane output [

35,

40].

Moreover, the resulting digestate is rich in macro- and micronutrients and has demonstrated agronomic value when applied as a biofertiliser. This aligns with European Union goals for sustainable nutrient recycling and reduced reliance on synthetic chemical fertilisers. Several field-scale assessments have confirmed the capacity of digestate derived from olive and citrus waste mixtures to increase soil organic matter content, water retention and crop yield, especially in degraded Mediterranean soils [

36,

41].

4. Potential Biomethane Production in the Mediterranean Region

The Mediterranean region possesses significant and diversified potential for biomethane production, due to its high availability of organic residues from agricultural, agro-industrial, municipal and livestock sources. Agricultural by-products such as olive pomace and wastewater, grape marc, citrus peel and tomato processing residues represent highly fermentable feedstocks with methane yields ranging from 250 to 450 m³ CH₄ per ton of Volatile Solids (VS) [

22,

36]. In Greece and Italy, the olive oil industry produces over 2 and 5 million tons of olive pomace per year, respectively, while Spain leads with over 3 million tons [

42]. Similarly, the wine industries of France, Italy and Greece contribute more than 6 million tons of grape marc annually, particularly during September–October harvest periods.

These lignocellulosic residues, often low in nitrogen, benefit from co-digestion with livestock manure or food waste, in order to optimise nutrient ratios and process stability [

23,

35]. In Southern Spain and Portugal, integrated AD plants have demonstrated a 15–20% increase in methane yield when co-digesting olive mill residues and pig slurry [

43]. Despite this, logistical limitations—particularly in fragmented rural areas of Southern Italy and inland Greece—still constrain the full exploitation of manure streams, with over 40% of theoretical potential unutilised [

7].

The Organic Fraction of Municipal Solid Waste (OFMSW) is increasingly valorised in urban regions like Barcelona, Rome and Marseille, with biogas yields between 100 and 250 m³ CH₄/t, especially when enriched by food service sector waste [

3,

44]. In France and Italy, dedicated biowaste collection schemes enable high capture rates (>70%) in urban districts, supporting stable feedstock availability for medium- to large-scale digesters. Portugal has recently expanded OFMSW separation zones in Lisbon and Porto, aiming at increasing biomethane output by 25% by 2030.

Emerging substrates like cactus pear (

Opuntia ficus-indica), widely cultivated in Sicily, Southern Spain and Tunisia, show great promise for biogas generation in arid zones. Cladodes and fruit processing residues have demonstrated yields of 300–350 m³ CH₄/t VS with very low irrigation and nutrient needs [

14,

45]. Moreover, citrus peel from Calabria and Valencia, and orange pulp from Moroccan juice industries, provide rich carbon sources, though requiring limonene pre-treatment, aimed at avoiding methanogenesis inhibition [

46,

47].

Sewage sludge from municipal wastewater treatment plants in cities like Athens, Palermo and Madrid also represents a consistent substrate, particularly when co-digested with brewery and dairy waste [

29]. Cross-sector integration is gaining ground, with France implementing regional hubs that collect food industry waste and municipal sewage sludge for biogas upgrading, boosting Circular Bioeconomy synergies [

48].

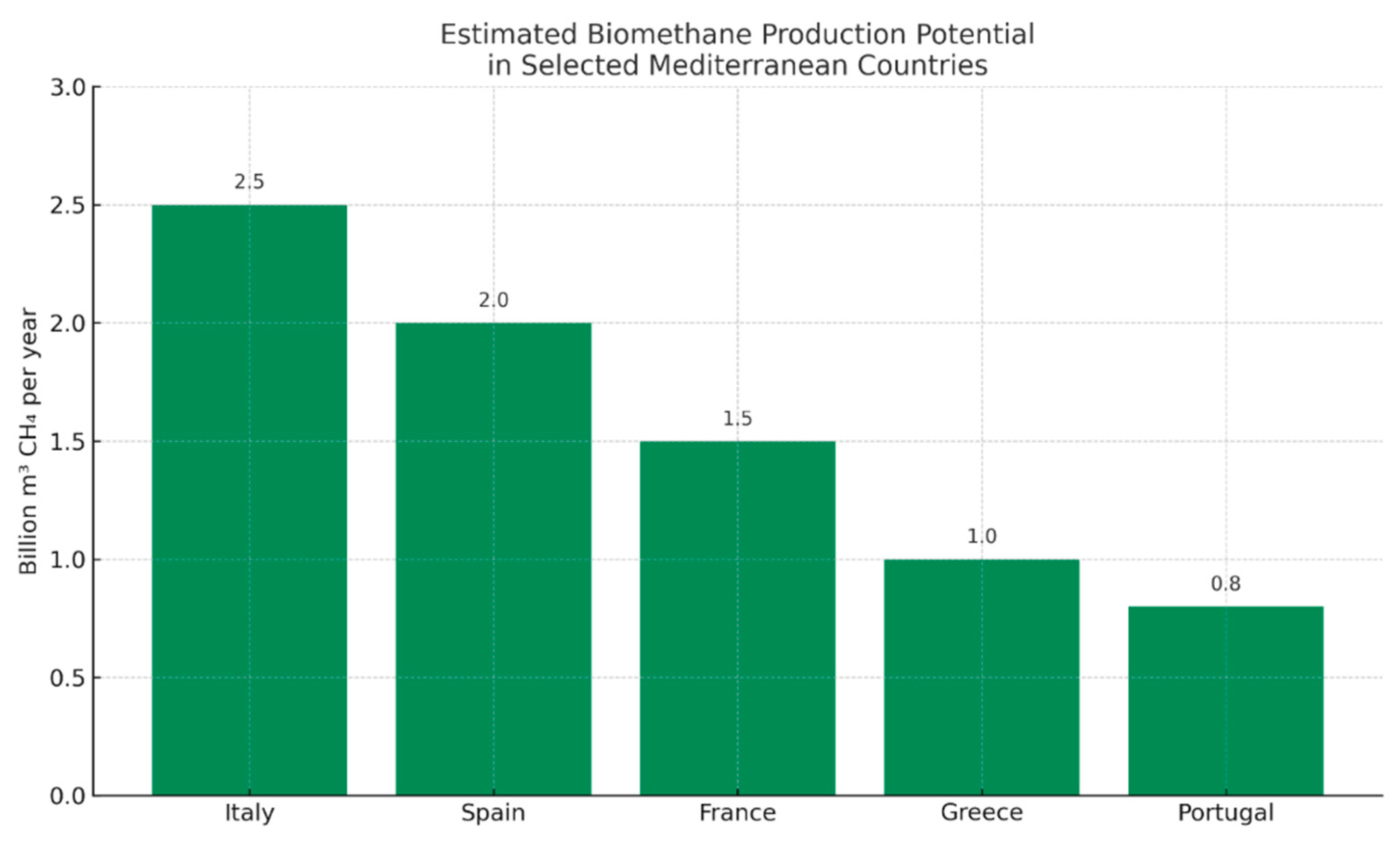

Overall, the combined biomethane production potential in the Mediterranean region—accounting for agro-industrial residues, OFMSW, manure, cactus biomass and sewage sludge—exceeds 8 billion m³ CH₄ per year, provided that collection logistics, pre-treatment strategies and upgrading units are adequately implemented. Unlocking this capacity could significantly reduce fossil gas dependence, support decarbonisation targets and empower rural bioeconomies through integrated biorefinery models across Italy, France, Spain, Greece and Portugal.

Figure 4 displays the annual potential biomethane production in billion cubic meters of CH₄ per year, based on available organic substrates such as agricultural residues, agro-industrial by-products, OFMSW and livestock manure in Italy (2.5 billion m³ CH₄/year), Spain (2.0 billion m³ CH₄/year), France (1.5 billion m³ CH₄/year), Greece (1.0 billion m³ CH₄/year), Portugal (0.8 billion m³ CH₄/year).

These figures reflect regional capacity based on agricultural residues, agro-industrial by-products, OFMSW and co-digestion integration.

5. Policy and Economic Drivers

The policy and economic landscape for biomethane production in the Mediterranean region is shaped by a combination of European Union directives, national strategies and local incentive frameworks, aimed at promoting renewable energy, waste valorisation and rural development. At the EU level, the Renewable Energy Directive II (Directive (EU) 2018/2001) [

49] and its recent recasting, RED III (Directive (EU) 2023/2413) [

50], establish ambitious targets for renewable energy integration, mandating increased shares of renewable gas—including biomethane—in the transport and heating sectors. These directives explicitly encourage the deployment of biomethane by setting sub-targets for advanced biofuels and facilitating market access through guarantees of origin and certification schemes [

51].

The EU Methane Strategy, adopted in 2020, further strengthens the policy framework by addressing methane emissions across the energy, agriculture and waste sectors. It promotes biomethane as a key tool for methane mitigation, encouraging the capture and use of methane from livestock waste and organic residues through AD [

52]. Additionally, the EU Biomethane Industrial Partnership (BIP), launched in 2022, aims at scaling up biomethane production to 35 billion m

3 annually by 2030, with specific support measures for investment, innovation and regional integration.

At national level, countries like Italy, Spain, France and Tunisia have implemented policies to stimulate biomethane development. Italy’s

Biometano Decree provides financial incentives for upgrading biogas to biomethane, including feed-in tariffs and premiums for biomethane used in transport. Spain’s Strategic Framework for Energy and Climate includes biomethane in its decarbonisation roadmap, supporting investment in infrastructure and biomethane injection into the gas grid. Tunisia, with support from international donors and the EU, has initiated pilot projects and regulatory reforms to facilitate small-scale biomethane production from agricultural waste [

53,

54].

In this evolving context, decision-support tools are essential to guide project developers and policymakers. The work of Asciuto et al. (2023) [

8] introduced an investment decision support tool specifically designed for evaluating biogas plant feasibility in Mediterranean islands. This tool integrates technical, environmental and economic parameters to assess the viability of AD projects in insular and rural areas, demonstrating how financial viability can be aligned with Circular Bioeconomy goals and regional sustainability objectives.

Furthermore, public-private partnerships and EU funding mechanisms such as the Horizon Europe programme, LIFE and the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) funds are increasingly directed towards Circular Bioeconomy projects, including biomethane production. These instruments reduce financial risks for investors and foster innovation adoption, particularly in decentralised and small-scale AD plants, common in the Mediterranean region [

55,

56].

6. Environmental and Agronomic Benefits

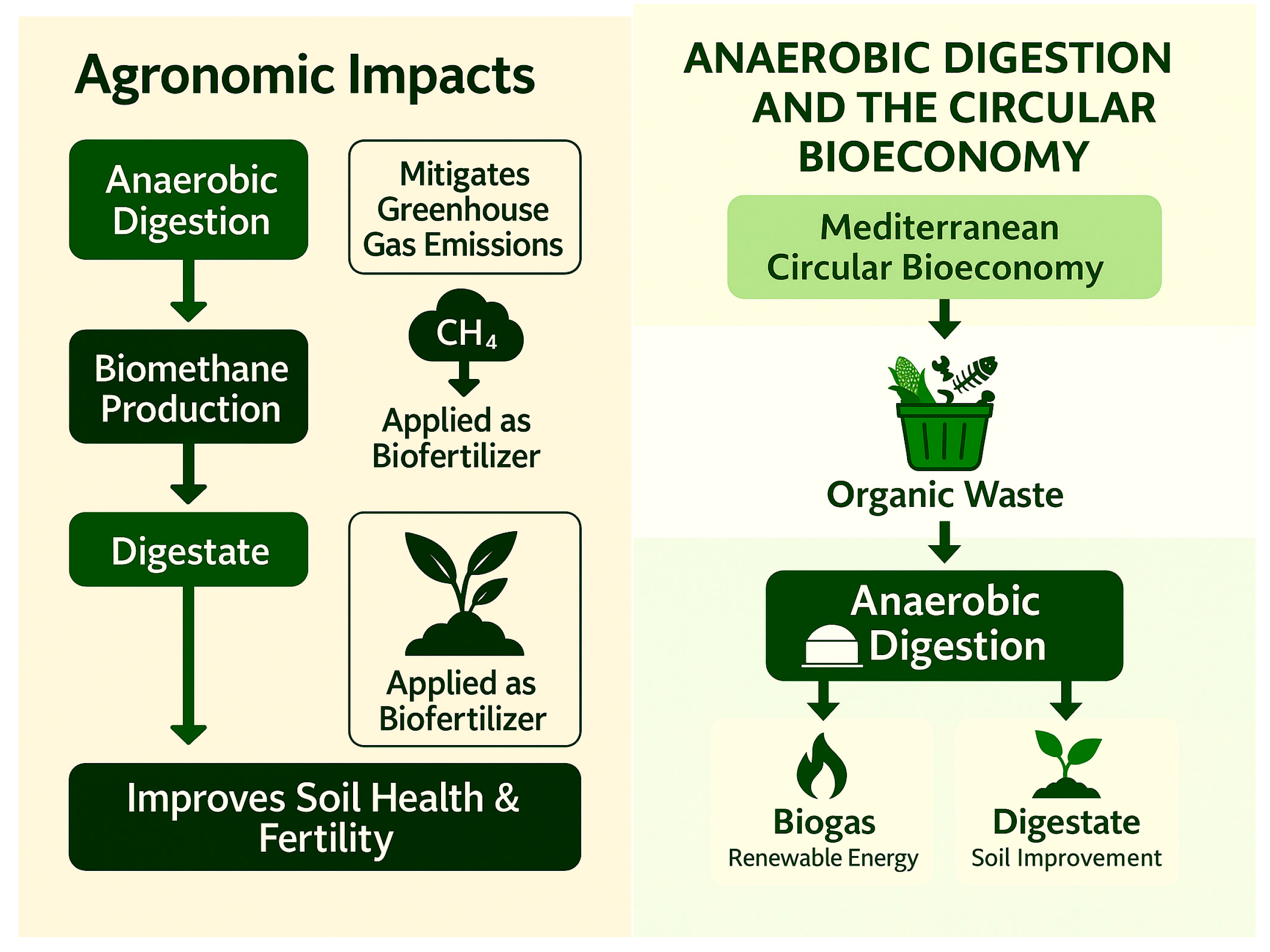

Biomethane production through Anaerobic Digestion (AD) not only offers a renewable energy pathway but also provides significant agronomic and environmental benefits (

Figure 5), making it a key enabler of climate-smart and circular agriculture in Mediterranean systems. By capturing methane that would otherwise be released from unmanaged organic waste—such as livestock manure, crop residues and agro-industrial by-products—AD mitigates one of the most potent greenhouse gases, i.e. methane. This directly contributes to climate neutrality goals outlined in the European Green Deal (EDG) and the “Fit for 55” package, aligning with strategies to decarbonise the agricultural and waste sectors [

3,

51].

A crucial co-product of the AD process is digestate, a semi-liquid or solid residue rich in nutrients and organic matter. Digestate typically contains readily plant-available nitrogen (both ammonium and organic forms), phosphorus, potassium, micronutrients and residual carbon. Its application to agricultural land has been shown to improve soil fertility, structure and microbial activity, as well as increase soil water retention and reduce erosion risk—particularly beneficial in Mediterranean areas prone to drought and soil degradation [

57,

58].

Field studies across Southern Europe have demonstrated that digestate use can increase crop yields and reduce the need for synthetic mineral fertilisers, contributing to nutrient circularity and lower environmental footprints. In particular, the application of digestate from co-digestion processes has proven effective in enhancing nitrogen-use efficiency, due to improved C/N balance and slower nutrient mineralisation rates, compared to synthetic chemical fertilisers [

59]. The reuse of digestate also reduces dependency on fossil-based synthetic chemical fertilisers, aligning with EU efforts for lower crop input costs and promoting sustainable nutrient management.

In high-input systems such as greenhouse horticulture, digestate can be used in fertigation systems, providing both nutrients and water to crops and improving resource-use efficiency [

16]. Furthermore, composted digestate can serve as a renewable substitute for peat in horticultural substrates, as well as its application contributes to the protection of peatlands and reduces carbon emissions linked to peat extraction. Greco et al. (2020, 2021) [

18,

19] found that compost and vermicompost derived from digestate were suitable for growing aromatic and medicinal plants, such as sage (

Salvia officinalis), without compromising its quality or yield.

From a life cycle perspective, the environmental performance of biomethane systems improves when powered by on-site renewable electricity and heat, particularly from solar photovoltaic (PV) or biomass boilers. Integrating AD into diversified farm systems with solar arrays or thermal recovery units can reduce energy costs and Greenhouse Gas (GHG) emissions while increasing energy autonomy [

32,

60]. Additionally, co-digestion strategies using different organic feedstocks—such as livestock manure, food waste and crop residues—optimise bioreactor stability, increase biogas yield and improve the quality and consistency of digestate.

Collectively, these agronomic and environmental synergies position biomethane production as a transformative technology for Mediterranean agriculture, offering integrated solutions for waste management, energy generation and soil regeneration, in line with agroecological and bioeconomic principles.

7. Biomethane in the Circular Bioeconomy

Anaerobic Digestion (AD) plays a pivotal role in the Circular Bioeconomy (CBE), offering a sustainable pathway to valorise organic waste streams, while producing renewable energy and bio-based products. In the context of the European Union’s energy transition and in light of recent geopolitical tensions—especially energy dependency from third countries such as Russia, Algeria, Libya, and the ongoing instability in Ukraine—AD represents a strategic solution to reduce reliance on imported fossil gas [

3,

48]. By converting agricultural residues, livestock manure and biowaste into biomethane, AD not only contributes to energy self-sufficiency but also supports regional development in rural areas [

61]. Moreover, the digestate—a nutrient-rich by-product of AD—serves as a valuable biofertiliser, closing nutrient cycles and reducing the need for synthetic chemical fertilisers [

58]. Recent studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of digestate and compost in enhancing soil structure, organic matter content and microbial biodiversity in Mediterranean agroecosystems [

62,

63]. In particular, research has shown that stabilised digestate and vermicompost can serve as renewable alternatives to peat in soilless cultivation systems, especially for nutraceutical and aromatic crops such as sage

(Salvia officinalis), oregano (

Origanum vulgare) and rosemary (

Rosmarinus officinalis) [

15,

18,

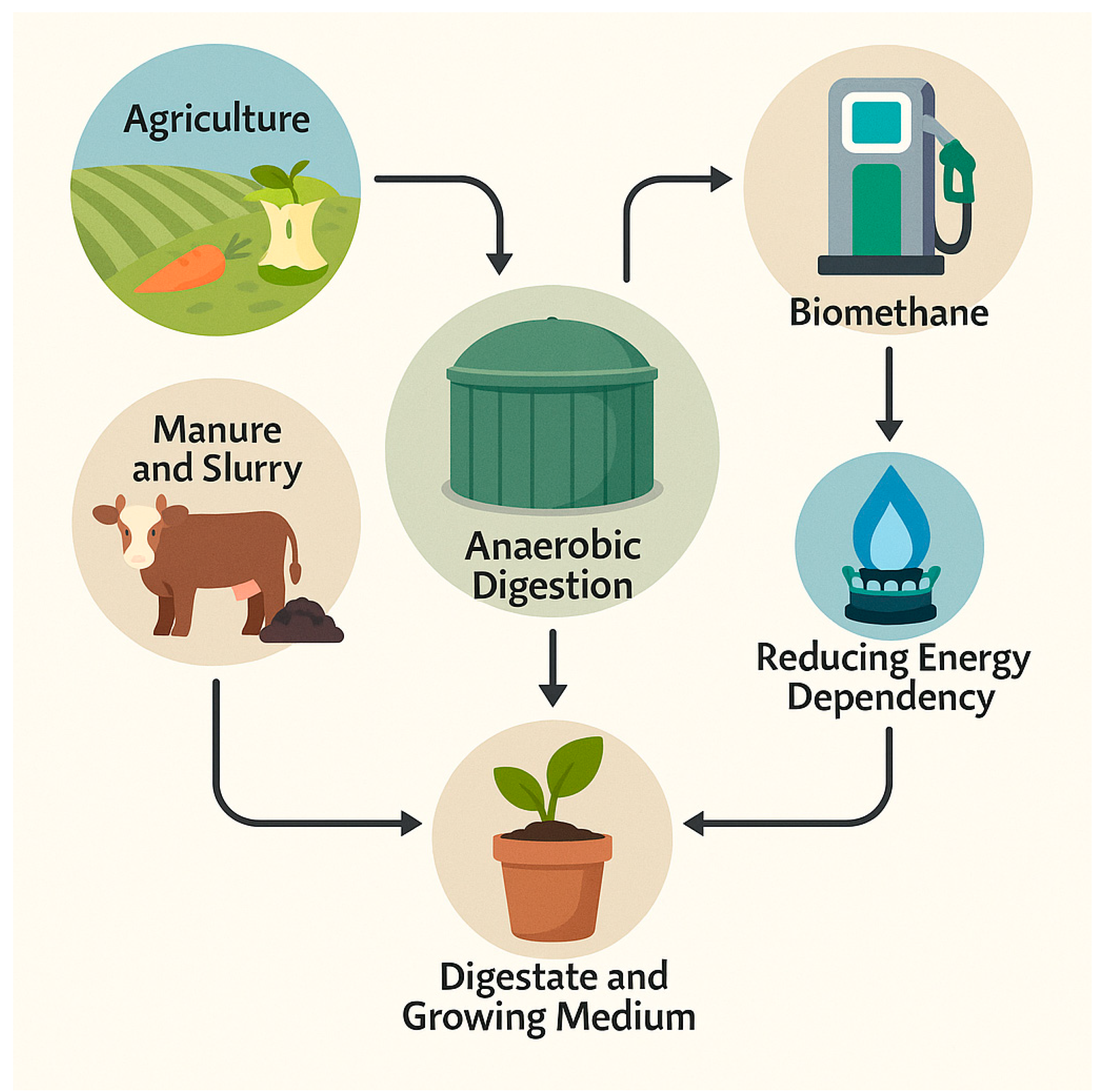

19]. These substrates support qualitative parameters of plant growth, while reducing environmental pressures associated with peat extraction. Thus, the integration of AD into agro-industrial supply chains enhances environmental sustainability, fosters circularity and promotes regional resilience within Mediterranean bioeconomies.

Figure 6 illustrates the integration of biowaste from agriculture, food industry and livestock (manure and slurry) into AD systems, producing biomethane and digestate, which are then used for generating renewable energy and as biofertiliser or peat alternative. This closed-loop model supports soil health and aromatic crop production, as well as it reduces energy dependency.

8. Biomethane in the Circular Bioeconomy

Despite the compelling environmental and socio-economic advantages of biomethane production, several technical, economic, infrastructural and social challenges continue to constrain its widespread adoption in the Mediterranean region (

Figure 7).

From a technical standpoint, the heterogeneity and seasonality of available feedstocks such as olive pomace and wastewater, citrus peel, grape marc and livestock manure pose challenges for consistent Anaerobic Digestion (AD) performance. These substrates often have variable moisture content, inhibitory compounds (e.g. phenolics, limonene) or high lignocellulosic fractions, requiring pre-treatment methods to enhance hydrolysis and microbial accessibility [

22,

23]. Furthermore, maintaining a stable microbial community under fluctuating environmental conditions remains a core research priority, especially for decentralised and small-scale digesters in rural or island contexts [

61,

64]. Limitations in gas upgrading infrastructure and the lack of gas grid injection points—common in peri-urban and remote areas—further restrict the scalability of biomethane initiatives.

Economic constraints represent another major barrier. The capital-intensive nature of AD plant development, particularly the upgrading stage to produce biomethane, imposes high entry costs. Operational expenses, including energy inputs, digestate management and maintenance, are also significant. While supportive national policies exist, such as Italy’s

Biometano Decree and Spain’s Recovery, Transformation and Resilience Plan, the lack of a harmonised Mediterranean regulatory framework leads to policy fragmentation, discouraging transnational investments and slowing market integration [

29]. Furthermore, the absence of long-term feed-in tariffs or stable biomethane pricing mechanisms creates uncertainty for project developers and investors.

Social challenges include limited public awareness of biomethane’s role in sustainable energy and agricultural systems, as well as moderate acceptance of digestate use in food-producing sectors. Concerns over odour emissions, land application practices and the proximity of AD plants to residential areas persist [

65]. In order to overcome these barriers, targeted stakeholder engagement, transparent communication strategies and educational campaigns are essential. The integration of biomethane initiatives into cooperative platforms and multifunctional farms can also improve community participation and socio-environmental acceptance.

Looking ahead, future perspectives should emphasise multi-actor innovation strategies. Research priorities include optimisation of co-digestion ratios, using locally abundant feedstocks, microbial consortia engineering for thermotolerant and inhibitor-resistant strains, as well as real-time process control through IoT-based monitoring systems and AI-enhanced diagnostics [

30,

31]. Modular and mobile AD plants offer a promising pathway for off-grid and seasonal production systems, particularly in fragmented Mediterranean landscapes. Additionally, integrating AD plants with renewable electricity sources such as solar PV and leveraging digestate for bio-based products—compost, biochar or bioplastics—can boost overall system circularity and value generation [

65,

66,

67,

68,

69,

70,

71,

72].

Finally, cross-border collaboration through platforms such as PRIMA (Partnership for Research and Innovation in the Mediterranean Area), IEA Bioenergy and Horizon Europe will be vital to harmonise technical standards, enable knowledge transfer and foster innovation ecosystems for a resilient Mediterranean biomethane sector.

9. Conclusions

Anaerobic Digestion (AD) emerges as a strategic technology at the intersection of sustainable agriculture, climate resilience and the Circular Bioeconomy (CBE)—offering tailored solutions to the complex environmental and energy challenges faced by Mediterranean countries. In a region marked by biowaste surpluses, declining soil fertility and dependency on external gas imports, AD provides a multifunctional pathway that transforms agricultural and agro-industrial residues into two high-value outputs: biomethane, a clean and locally produced renewable energy source, and digestate, a nutrient-rich amendment that can restore degraded soils and close nutrients cycles.

The dual role of AD in producing renewable energy and regenerating soil health embodies the basic principles of CBE. Its integration into diversified, multifunctional farming systems can reduce Greenhouse Gas (GHG) emissions, enhance soil organic matter and improve water retention—particularly critical in regions such as Sicily, Spain, Malta and Greece that are increasingly threatened by desertification. Moreover, the deployment of small- and medium-scale biomethane plants across rural and insular areas enables decentralised energy production, supports local economies and enhances climate-smart infrastructure.

Case studies from Italy, Spain, Tunisia and other Mediterranean countries confirm the technical feasibility and socio-economic value of embedding AD systems within existing agricultural and waste management frameworks. These systems support a variety of utilisation pathways—including grid injection, vehicle biofuel, on-site power generation and digestate reuse—each offering synergistic benefits across environmental, economic and agronomic domains.

Nonetheless, realising the full potential of biomethane requires a paradigm shift from linear to circular models of production. This transformation hinges on coordinated efforts in innovation, policy and capacity building. Technical challenges such as feedstock seasonality, lignocellulosic recalcitrance and cost-efficient upgrading require further research into co-digestion strategies, microbial optimisation and pre-treatment technologies. Meanwhile, advances in digital monitoring, precision agriculture and IoT-enabled systems can improve process control and tailor digestate applications to site-specific conditions.

Policy frameworks such as RED III and national biogas strategies provide momentum but harmonisation across Mediterranean countries, long-term investment incentives and higher stakeholder awareness are essential to scale up deployment. Social acceptance and knowledge transfer mechanisms will also play a decisive role in mainstreaming AD into agricultural and energy policy landscapes.

Ultimately, AD is far more than a waste management tool as it is a cornerstone technology for a resilient, low-carbon and regenerative Mediterranean agriculture. By embracing AD within a broader Circular Bioeconomy framework, Mediterranean countries can reduce waste, enhance food and energy security, mitigate climate impacts and revitalise rural areas. In doing so, they can lead the way in building an agricultural future, that is not only productive but also sustainable and equitable.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.C. and C.G.; methodology, S.O., S.C., F.S.; software, C.G. and S.O.; validation, A.C., C.G. and F.S.; formal analysis, S.C.; investigation, C.G. and A.C.; resources, S.C.; data curation, F.S.; writing—original draft preparation, A.C., C.G. and S.O.; writing—review and editing, S.C. and F.S.; visualization, S.O. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was financially supported by the Innovation Diffusion Plan within the first Food District Call - District Contract Program “Distretto del Cibo Bio Slow Pane e Olio” – CUP: J95B02000030007. Piano di diffusione delle innovazioni nell’ambito del primo Bando Distretti del cibo - Programma del Contratto di Distretto “Distretto del cibo Bio Slow Pane e Olio”: J95B02000030007.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Cramer, W.; Guiot, J.; Fader, M.; Garrabou, J.; Gattuso, J.P.; Iglesias, A.; ...; Xoplaki, E. Climate change and interconnected risks to sustainable development in the Mediterranean. Nature Climate Change 2018, 8(11), 972-980.

- Lionello, P.; Scarascia, L. The relation between climate change in the Mediterranean region and global warming. Regional Environmental Change 2018, 18, 1481-1493. [CrossRef]

- Scarlat, N.; Dallemand, J.F.; Fahl, F. Biogas: Developments and perspectives in Europe. Renewable Energy 2018, 129, 457-472. [CrossRef]

- Zupančič, M.; Možic, V.; Može, M.; Cimerman, F.; Golobič, I. Current status and review of waste-to-biogas conversion for selected European countries and worldwide. Sustainability 2022, 14(3), 1823. [CrossRef]

- Comparetti, A.; Febo, P.; Greco, C.; Orlando, S.; Navickas, K.; Venslauskas, K. Sicilian potential biogas production. Journal of Agricultural Engineering 2013, 44(s2).

- Comparetti, A.; Febo, P.; Greco, C.; Navickas, K.; Nekrosius, A.; Orlando, S.; Venslauskas, K. Assessment of organic waste management methods through energy balance. American Journal of Applied Sciences 2014, 11(9), 1631-1644. [CrossRef]

- Attard, G.; Comparetti, A.; Febo, P.; Greco, C.; Mammano, M.M., Orlando, S. (2017). Case study of potential production of Renewable Energy Sources (RES) from livestock wastes in Mediterranean islands. Chemical Engineering Transactions 2018, 58, 553-558.

- Asciuto, A.; Agosta, M.; Attard, G.; Comparetti, A.; Greco, C.; Mammano, M.M. Development of an Investment Decision Tool for Biogas Production from Biowaste in Mediterranean Islands. In Conference of the Italian Society of Agricultural Engineering; Cham Springer International Publishing: 2022, 251-262.

- Choudhary, A.; Kumar, A.; Kumar, S.; Govil, T.; Sani, R.K. Enhanced biogas production from pine litter codigestion with food waste, microbial community, kinetics, and technoeconomic feasibility. Journal of Environmental Engineering 2023, 149(1), 04022089. [CrossRef]

- Kougias, P.G.; Angelidaki, I. Biogas and its opportunities—A review. Frontiers of Environmental Science & Engineering 2018, 12, 1-12.

- Comparetti, A.; Greco, C.; Navickas, K.; Venslauskas, K. Evaluation of potential biogas production in Sicily. In Proceedings of the 11th International Scientific Conference Engineering for Rural Development; Jelgava, Latvia, 2012, 24-25.

- Greco, C.; Comparetti, A.; Orlando, S.; Mammano, M.M. A contribution to environmental protection through the valorisation of kitchen biowaste. In Safety, Health and Welfare in Agriculture and Agro-food Systems. SHWA 2020. Lecture Notes in Civil Engineering (LNCE); Biocca, M., Cavallo, E., Cecchini, M., Failla, S., Romano, E., eds.; 2022, Volume 252, 411–420.

- Greco, C.; Attard, G.; Fenech, O.; Alessandro, A.; Comparetti, A. Manure as a potential source of renewable energy: The behaviour and characterisation of biofuels generated from three animal manure types when subjected to pyrolysis. Rivista di Studi sulla Sostenibilità 2019a, IX, Supplemento 2, 331-344. [CrossRef]

- Comparetti, A.; Febo, P.; Greco, C.; Mammano, M.M.; Orlando, S. Potential production of biogas from prinkly pear (Opuntia ficus-indica L.) in Sicilian uncultivated areas. Chemical Engineering Transactions 2017, 58, 559-564.

- Greco, C.; Navickas, K.; Orlando, S.; Comparetti, A.; Venslauskas, K. Life Cycle Impact Assessment applied to cactus pear crop production for generating bioenergy and biofertiliser. Rivista di Studi sulla Sostenibilità 2019b, IX, Supplemento 2, 315-329. [CrossRef]

- Campiotti, C.A.; Bibbiani, C.; Greco, C. Renewable energy for greenhouse agriculture. Qual. - Access to Success 2019, 20.

- Attard, G.; Azzopardi, N.; Comparetti, A.; Greco, C.; Gruppetta, A.; Orlando, S. Potential bioenergy and biofertiliser production from livestock waste in Mediterranean Islands within circular bioeconomy. In Conference of the Italian Society of Agricultural Engineering; Cham Springer International Publishing: 2022, 271-283.

- Greco, C.; Comparetti, A.; Febo, P.; La Placa, G.; Mammano, M.M.; Orlando, S. Sustainable valorisation of biowaste for soilless cultivation of Salvia officinalis in a circular bioeconomy. Agronomy 2020, 10(8), 1158. [CrossRef]

- Greco, C.; Comparetti, A.; Fascella, G.; Febo, P.; La Placa, G.; Saiano, F.; ... Laudicina, V.A. Effects of vermicompost, compost and digestate as commercial alternative peat-based substrates on qualitative parameters of Salvia officinalis. Agronomy 2021, 11(1), 98.

- Asunis, F.; De Gioannis, G.; Isipato, M.; Muntoni, A.; Polettini, A.; Pomi, R.; ... Spiga, D. Control of fermentation duration and pH to orient biochemicals and biofuels production from cheese whey. Bioresource Technology 2019, 289, 121722. [CrossRef]

- Bolzonella, D.; Pavan, P.; Battistoni, P.; Cecchi, F. Anaerobic co-digestion of sludge with other organic wastes and phosphorus reclamation in wastewater treatment plants for biological nutrients removal. Water Science and Technology 2006, 53(12), 177-186. [CrossRef]

- Bacenetti, J.; Fiala, M.; Baboun, S.H.; Demery, F.; Aburdeineh, I. Environmental impact assessment of electricity generation from biogas in Palestine. Environmental Engineering & Management Journal (EEMJ) 2016, 15(9). [CrossRef]

- Carrere, H.; Antonopoulou, G.; Affes, R.; Passos, F.; Battimelli, A.; Lyberatos, G.; Ferrer, I. Review of feedstock pretreatment strategies for improved anaerobic digestion: From lab-scale research to full-scale application. Bioresource Technology 2016, 199, 386-397. [CrossRef]

- Tallou, A.; Salcedo, F.P.; Haouas, A.; Jamali, M.Y.; Atif, K.; Aziz, F.; Amir, S. Assessment of biogas and biofertilizer produced from anaerobic co-digestion of olive mill wastewater with municipal wastewater and cow dung. Environmental Technology & Innovation 2020, 20, 101152. [CrossRef]

- Calabrò, P.S.; Pontoni, L.; Porqueddu, I.; Greco, R.; Pirozzi, F.; Malpei, F. Effect of the concentration of essential oil on orange peel waste biomethanization: Preliminary batch results. Waste Management 2016, 48, 440-447. [CrossRef]

- Arfelli, F.; Cespi, D.; Ciacci, L.; Passarini, F. Application of life cycle assessment to high quality-soil conditioner production from biowaste. Waste Management 2023, 172, 216-225. [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q.; Li, H.; Yan, J.; Liu, L.; Yu, Z.; Yu, X. Selection of appropriate biogas upgrading technology-a review of biogas cleaning, upgrading and utilisation. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2015, 51, 521-532. [CrossRef]

- Petersson, A.; Wellinger, A. Biogas upgrading technologies–developments and innovations. IEA Bioenergy 2009, 20, 1-19.

- Scarlat, N.; Prussi, M.; Padella, M. Quantification of the carbon intensity of electricity produced and used in Europe. Applied Energy 2022, 305, 117901. [CrossRef]

- Angelidaki, I., Treu, L., Tsapekos, P., Luo, G., Campanaro, S., Wenzel, H., & Kougias, P. G. Biogas upgrading and utilization: Current status and perspectives. Biotechnology Advances 2018, 36(2), 452-466. [CrossRef]

- Tian, G.; Yang, B.; Dong, M.; Zhu, R.; Yin, F.; Zhao, X.; ... Cui, X. The effect of temperature on the microbial communities of peak biogas production in batch biogas reactors. Renewable Energy 2018, 123, 15-25. [CrossRef]

- Rossi, E.; Pecorini, I.; Iannelli, R. Multilinear regression model for biogas production prediction from dry anaerobic digestion of OFMSW. Sustainability 2022, 14(8), 4393. [CrossRef]

- Qin, Y.; Huang, L.; Jiang, Q.; Lu, T.; Xin, Y.; Zhen, Y.; ... Shen, P. Anaerobic co-digestion of molasses vinasse and three kinds of manure: A comparative study of performance at different mixture ratio and organic loading rate. Journal of Cleaner Production 2022, 371, 133631. [CrossRef]

- Khalid, N.A.; Rajandas, H.; Parimannan, S.; Croft, L.J.; Loke, S.; Chong, C.S.; ... Yahya, A. Insights into microbial community structure and diversity in oil palm waste compost. Biotech 2019, 9, 1-11. [CrossRef]

- Semeraro, B.; Summa, D.; Costa, S.; Zappaterra, F.; Tamburini, E. Bio-delignification of green waste (GW) in co-digestion with the organic fraction of municipal solid waste (OFMSW) to enhance biogas production. Applied Sciences 2021, 11(13), 6061. [CrossRef]

- Di Maria, F.; El-Hoz, M. A short review of comparative energy, economic and environmental assessment of different biogas-based power generation technologies. Energy Procedia 2018, 148, 846-851.

- Drosg, B. Process monitoring in biogas plants. IEA Bioenergy: Paris, France, 2013, pp.1-38.

- Zema, D.A.; Fòlino, A.; Zappia, G.; Calabrò, P.S.; Tamburino, V.; Zimbone, S.M. Anaerobic digestion of orange peel in a semi-continuous pilot plant: An environmentally sound way of citrus waste management in agro-ecosystems. Science of the Total Environment 2018, 630, 401-408. [CrossRef]

- García-González, M.C.; Hernández, D.: Molinuevo-Salces, B.: Riaño, B. Positive impact of biogas chain on GHG reduction. Improving Biogas Production: Technological Challenges, Alternative Sources, Future Developments 2019, 217-242.

- Capson-Tojo, G.; Moscoviz, R.; Astals, S.; Robles, Á.; Steyer, J.P. Unraveling the literature chaos around free ammonia inhibition in anaerobic digestion. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2020, 117, 109487. [CrossRef]

- Chinea, L.; Slopiecka, K.; Bartocci, P.; Park, A.H.A.; Wang, S.; Jiang, D.; Fantozzi, F. Methane enrichment of biogas using carbon capture materials. Fuel 2023, 334, 126428. [CrossRef]

- FAO (Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Faostat: crop production data. Production data 2020. Available online: http://www.fao.org/faostat/ (accessed on 6 May 2025).

- Deschamps, L.; Imatoukene, N.; Lemaire, J.; Mounkaila, M.; Filali, R.; Lopez, M.; Theoleyre, M.A. In-situ biogas upgrading by bio-methanation with an innovative membrane bioreactor combining sludge filtration and H2 injection. Bioresource Technology 2021, 337, 125444. [CrossRef]

- Avena, L.G.; Almendrala, M.; Marron, E.J.; Obille, J.A. Biogas Production from the Co-and Tri-digestion of Pineapple Wastes with Food Wastes and Pig Manure. In E3S Web of Conferences; EDP Sciences: 2024, Volume 521, p. 01004.

- Antón-Herrero, R.; García-Delgado, C.; Alonso-Izquierdo, M.; Cuevas, J.; Carreras, N.; Mayans, B.; ...; Eymar, E. New uses of treated urban waste digestates on stimulation of hydroponically grown tomato (Solanum lycopersicon L.). Waste and Biomass Valorization 2021, 12, 1877-1889.

- Zema, D.A.; Fòlino, A.; Zappia, G.; Calabrò, P.S.; Tamburino, V.; Zimbone, S.M. Anaerobic digestion of orange peel in a semi-continuous pilot plant: An environmentally sound way of citrus waste management in agro-ecosystems. Science of the Total Environment 2018, 630, 401-408. [CrossRef]

- Riaño, B.; García-González, M.C. On-farm treatment of swine manure based on solid-liquid separation and biological nitrification-denitrification of the liquid fraction. J Environ Manage 2014, 132, 87-93. [CrossRef]

- Kampman, N.; Busch, A.; Bertier, P.; Snippe, J.; Hangx, S.; Pipich, V.; ...; Bickle, M.J. Observational evidence confirms modelling of the long-term integrity of CO2-reservoir caprocks. Nature Communications 2016, 7(1), 12268.

- Directive (EU) 2018/2002 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 11 December 2018 amending directive 2012/27/EU on energy efficiency.

- EU RED III. Directive 2023/2413 on the promotion of the use of energy from renewable sources.

- European Commission. The European Green Deal. COM(2019) 640 final. Brussels, 2019. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:52019DC0640 (accessed on 13 May 2025).

- European Commission. A European Green Deal – EU Strategy to Reduce Methane Emissions; COM(2020) 663 Final, Brussels, 2020. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:52020DC0663 (accessed on 14 May 2025).

- Borchers, M.; Thrän, D.; Chi, Y.; Dahmen, N.; Dittmeyer, R.; Dolch, T.; ...; Yeates, C. Scoping carbon dioxide removal options for Germany–What is their potential contribution to Net-Zero CO2?. Frontiers in Climate 2022, 4, 810343.

- Kardung, M.; Cingiz, K.; Costenoble, O.; Delahaye, R.; Heijman, W.; Lovrić, M.; ...; Zhu, B.X. Development of the circular bioeconomy: Drivers and indicators. Sustainability 2021, 13(1), 413.

- European Biogas Association (EBA). Biomethane Industrial Partnership—Accelerating Biomethane Scale-up in the EU; EBA, 2022. Available online: https://www.europeanbiogas.eu/bip/ (accessed on 26 May 2025).

- Bertolino, A.M.; Giganti, P.; dos Santos, D.D.; Falcone, P.M. A matter of energy injustice? comparative analysis of biogas development in Brazil and Italy. Energy Research & Social Science 2023, 105, 103278. [CrossRef]

- Tambone, F.; Pradella, M.; Bedussi, F.; Adani, F. Moringa oleifera Lam. as an energy crop for biogas production in developing countries. Biomass Conversion and Biorefinery 2020, 10(4), 1083-1089. [CrossRef]

- Möller, K.; Müller, T. Effects of anaerobic digestion on digestate nutrient availability and crop growth: A review. Engineering in Life Sciences 2012, 12(3), 242-257. [CrossRef]

- Tamburini, G.; Pereira-Peixoto, M.H.; Borth, J.; Lotz, S.; Wintermantel, D.; Allan, M.J., ...; Klein, A.M. Fungicide and insecticide exposure adversely impacts bumblebees and pollination services under semi-field conditions. Environment International 2021, 157, 106813.

- Fantozzi, F.; Buratti, C. Anaerobic digestion of mechanically treated OFMSW: Experimental data on biogas/methane production and residues characterization. Bioresource Technology 2011, 102(19), 8885-8892. [CrossRef]

- Tamburini, M.; Pernetti, R.; Anelli, M.; Oddone, E.; Morandi, A.; Osuchowski, A.; ...; Monti, M.C. Analysing the Impact on Health and Environment from Biogas Production Process and Biomass Combustion: A Scoping Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2023, 20(7), 5305.

- Alburquerque, J.A.; de la Fuente, C.; Ferrer-Costa, A.; Carrasco, L.; Cegarra, J.; Abad, M.; Bernal, M.P. Assessment of the fertiliser potential of digestates from farm and agroindustrial residues. Biomass and Bioenergy 2012, 40, 181-189. [CrossRef]

- Greco, C.; Navickas, K.; La Placa, G.; Mammano, M.M.; Agnello, A. Biowaste in a circular bioeconomy in Mediterranean area: A case study of compost and vermicompost as growing substrates alternative to peat. Rivista di Studi sulla Sostenibilità 2019c, IX, Supplemento 2, 345-362. [CrossRef]

- De Gioannis, G.; Dell’Era, A.; Muntoni, A.; Pasquali, M.; Polettini, A.; Pomi, R.; ...; Zonfa, T. Bio-electrochemical production of hydrogen and electricity from organic waste: Preliminary assessment. Clean Technologies and Environmental Policy 2023, 25(1), 269-280.

- D’Adamo, I.; Mazzanti, M.; Morone, P.; Rosa, P. Assessing the relation between waste management policies and circular economy goals. Waste Management 2022, 154, 27-35. [CrossRef]

- Hidalgo, D.; Martín-Marroquín, J.M.; Corona, F. A multi-waste management concept as a basis towards a circular economy model. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2019, 111, 481-489. [CrossRef]

- Luttenberger, L.R. Waste management challenges in transition to circular economy–case of Croatia. Journal of Cleaner production 2020, 256, 120495. [CrossRef]

- Pires, A.; Martinho, G. Waste hierarchy index for circular economy in waste management. Waste Management 2019, 95, 298-305. [CrossRef]

- Romero-Hernández, O.; Romero, S. Maximizing the value of waste: From waste management to the circular economy. Thunderbird International Business Review 2018, 60(5), 757-764. [CrossRef]

- Chioatto, E.; Sospiro, P.. Transition from waste management to circular economy: the European Union roadmap. Environment, Development and Sustainability 2023, 25(1), 249-276. [CrossRef]

- Nelles, M.; Gruenes, J.; Morscheck, G. Waste management in Germany–development to a sustainable circular economy?. Procedia Environmental Sciences 2016, 35, 6-14.

- Afshari, H.; Gurtu, A.; Jaber, M.Y. Unlocking the potential of solid waste management with circular economy and Industry 4.0. Computers & Industrial Engineering 2024, 110457. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).