1. Introduction

Implementation science was developed to tackle the well-known gap between generating and applying evidence in practice. However, despite years of research yielding evidence-based interventions, translating discoveries into widespread implementation is still slow, inconsistent, and incomplete across fields like healthcare, public health, education, and social services [

1]. This ongoing issue leads to subpar outcomes, inefficient use of resources, and persistent inequities that compromise the core objective of evidence-based practice.

Evidence synthesis is a significant hurdle in this translation process, which involves systematically gathering, assessing, and integrating research findings to guide implementation decisions. While traditional evidence synthesis methods are thorough, they require considerable time and resources, generally taking 6 to 24 months and thousands of person-hours to conduct systematic reviews [

2,

3]. This lengthy process clashes with the urgent requirement for prompt and responsive implementation of evidence-based practices, especially in fast-changing sectors or crises. The increasing pace of research publication exacerbates the situation, with biomedical literature growing by around 4,000 new articles each day [

4]. As a result, it becomes increasingly challenging for human reviewers to stay updated with pertinent evidence, while systematic reviews risk becoming outdated soon after they are published as new evidence surfaces [

5].

Recent advancements in artificial intelligence, especially in machine learning and large language models, have showcased their ability to automate essential aspects of evidence synthesis workflows [

6,

7,

8,

9,

10]. This has sparked interest in their potential to tackle long-standing issues, even amidst concerns regarding their limitations and risks. However, implementation science presents specific demands regarding evidence synthesis that go beyond conventional systematic review methods. The field emphasizes understanding not only "what works" but also "for whom, under what conditions, and how" [

11,

12]. Implementation decisions rely on timely, context-specific synthesis that adjusts responsively to changing evidence, local circumstances, and practical experiences while upholding the field's dedication to stakeholder engagement, contextual sensitivity, and equity considerations.

The contrast between the efficiency offered by automation and the focus of implementation science on detailed understanding of context and stakeholder viewpoints creates both opportunities and challenges that must be navigated carefully to uphold the core values of the field while harnessing technological advancements. The Exploration, Preparation, Implementation, and Sustainment (EPIS) framework provides a proven structure for understanding implementation processes and can guide the responsible integration of automated synthesis technologies [

13].

This study aims to develop a thorough framework for incorporating automated evidence synthesis methods into implementation science practices, while considering critical issues related to contextual sensitivity, trustworthiness, and equity at the core of the field. By systematically analyzing empirical evidence on the performance of automated synthesis, evaluating the specific requirements of implementation science, and applying the Exploration, Preparation, Implementation, and Sustainment framework, we offer structured guidance for responsible adoption that strikes a balance between efficiency improvements and the preservation of vital human expertise in contextual interpretation and stakeholder engagement. Our framework advances implementation science by introducing the first systematic method for integrating technology that adheres to field principles while allowing organizations to utilize automation's proven capabilities to decrease synthesis time by 50-95% and to facilitate ongoing evidence monitoring, which has the potential to change the translation of evidence into practice significantly.

2. Methods

Framework Development Approach

We developed our integration framework through a systematic, multi-phase process that combined evidence synthesis, theoretical application, and principles of implementation science. The framework was developed between October 2024 and June 2025, incorporating recent empirical evidence and established implementation science theories.

Literature Analysis and Evidence Synthesis

We carried out an extensive review of empirical research on automated evidence synthesis methods, particularly their potential applications in implementation science. Our search approach focused on peer-reviewed articles from 2020 to 2025 that presented quantitative performance metrics for AI-enhanced synthesis techniques, including studies related to automated screening, data extraction, living reviews, and measures of synthesis accuracy [

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19].

The literature analysis followed a three-step approach. Initially, we located studies via targeted searches in primary databases that emphasized machine learning's role in systematic reviews, the effectiveness of large language models in evidence synthesis, and the validation of automated screening methods. We also incorporated recent systematic reviews and methodological guidance on living systematic reviews [

20,

21]. Next, we extracted quantitative performance data such as time reduction percentages, accuracy metrics, measures of sensitivity and specificity, and comparisons of resource utilization between automated and conventional approaches. Finally, we examined reported limitations and challenges, focusing on issues like contextual sensitivity, reference accuracy, and equity considerations that are particularly pertinent to the field of implementation science.

Implementation Science Perspective Analysis

We thoroughly assessed the recognized advantages and disadvantages of automated synthesis, focusing specifically on the principles and values of implementation science [

11,

12,

22]. This evaluation included aligning the capabilities and limitations of automated synthesis with essential requirements of implementation science, such as the necessity for contextual awareness, engagement of stakeholders, considerations of equity, and processes rooted in evidence-based decision making.

Our analytical framework explored five essential dimensions of implementation science. We evaluated the requirements for contextual sensitivity by examining how automated methods manage subtle implementation factors, including organizational context, population traits, and adaptation needs of interventions. We analyzed the effects of stakeholder engagement by investigating how automated synthesis could influence the collaborative decision-making processes vital for successful implementation. We reviewed equity considerations by considering potential biases within automated systems and their impact on various implementation contexts [

23,

24]. Additionally, we assessed the requirements for evidence integration by exploring how automated methods address the varied types of evidence necessary for implementation decisions, encompassing both effectiveness and implementation research. Lastly, we evaluated the implications for capacity and resources by reflecting on the infrastructure, skills, and governance needed for deploying automated synthesis across different organizational settings.

Theoretical Framework Application

We used the Exploration, Preparation, Implementation, and Sustainment (EPIS) framework [

13] to structure our integration recommendations. This framework was chosen for its proven, phase-based model of the implementation process, which has shown effectiveness in various implementation contexts and has been validated through systematic review across 50+ applications [

25]. The four phases of the framework correspond well with the decision points where automated synthesis may offer benefits, necessitating different considerations and precautions.

In our application of EPIS, we systematically mapped opportunities and challenges related to automated synthesis across each implementation phase. During the Exploration phase, we explored how automated synthesis could aid in needs assessment and intervention identification while ensuring stakeholder input and contextual factors are respected. In the Preparation phase, we assessed how automated approaches could improve strategy development and adaptation planning while adhering to quality and equity standards. In the Implementation phase, we looked into possibilities for continuous evidence monitoring and strategy refinement while guaranteeing proper human oversight. Lastly, in the Sustainment phase, we evaluated how automated synthesis could facilitate ongoing adaptation and quality improvement while developing sustainable capacity and governance frameworks.

Multi-Dimensional Comparative Assessment

We conducted a detailed comparative analysis across nine essential dimensions of implementation science practice [

22,

26,

27]. This evaluation systematically examined the possible advantages and disadvantages of automated synthesis for each dimension, utilizing empirical evidence when accessible and implementation science theory when empirical data were scarce.

The assessment process included developing thorough evaluation matrices for each dimension. We gathered quantitative data on synthesis acceleration to save time, weighing potential quality trade-offs. To ensure comprehensiveness, we examined scope expansion capabilities against the risks of information overload and diminished selectivity. For consistency, we looked into the benefits of standardization while being mindful of the dangers of algorithmic rigidity. Regarding contextual sensitivity, we assessed automated methods' effectiveness in capturing implementation-relevant nuances, identifying possible losses of crucial contextual information.

Regarding trustworthiness, we evaluated data on accuracy and reliability while addressing transparency and auditability challenges [

28,

29]. For stakeholder engagement, we analyzed resource implications alongside potential effects on collaborative processes. To preserve human expertise, we explored the possibilities of augmentation while recognizing the risks of skill atrophy [

30,

31]. When considering equity, we assessed the potential for democratization while analyzing the risks of bias amplification [

23,

24]. Lastly, we reviewed the advantages of continuous monitoring and the challenges in information management for living evidence capabilities.

Integration Strategy Development

Through our evaluation, we established tailored integration strategies that harness the advantages of automated synthesis while addressing identified risks. This involved generating specific recommendations for each EPIS phase, outlining suitable divisions of human and AI tasks, quality assurance protocols, stakeholder engagement methods, and equity protections.

Our strategy for integration development rests on three essential principles drawn from implementation science theory and practice. First, we focused on enhancing human-AI collaboration instead of human replacement, ensuring that automation enhances rather than replaces crucial human judgment in interpretation and stakeholder interaction. Second, we emphasized equity and inclusion by incorporating systematic bias monitoring and diverse stakeholder engagement into all recommendations [

32]. Third, we highlighted adaptive implementation by developing flexible frameworks that adjust to various organizational contexts and changing technological capabilities.

The human-AI collaboration model central to our framework is implemented through a structured workflow that maintains human oversight at critical decision points while utilizing automation for efficiency gains.

Figure 1 illustrates this collaborative process across six phases, from project initiation to continuous monitoring. The workflow highlights strategic handoff points where human expertise is essential, particularly for contextual interpretation, stakeholder engagement, and quality validation. This collaborative approach ensures that automation enhances rather than replaces human judgment in areas where implementation science expertise is irreplaceable.

Framework Validation and Testing Considerations

Although this framework offers a conceptual contribution grounded in existing empirical evidence and implementation science theory, our recommendations are crafted to facilitate systematic empirical validation. Each recommendation outlines clear, measurable criteria that can be assessed through pilot implementations, comparative effectiveness studies, and stakeholder assessment research.

We organized the framework validation method into three levels. For individual recommendations, each suggestion contains specific metrics to assess success, such as goals for time reduction, accuracy thresholds, stakeholder satisfaction measures, and equity indicators. At the phase level, we identified essential outcomes for each EPIS phase that can be evaluated through implementation studies, including the quality of needs assessment, effectiveness of strategy development, capabilities for implementation monitoring, and success rates for sustainment. At the framework level, we outlined overall system outcomes that can be analyzed through longitudinal studies, such as reductions in the evidence-to-practice gap, implementation equity improvements, and stakeholder capacity development.

The validation design includes mechanisms for iterative refinement. We organized recommendations to integrate feedback from pilot implementations and stakeholder experiences, facilitating ongoing framework improvement based on practical testing. This adaptive validation method embodies the principles of implementation science, focusing on learning-driven and context-aware development that can adapt according to empirical evidence and user requirements.

3. Results

3.1. Empirical Evidence on Automated Synthesis Capabilities

Time Efficiency Gains: Numerous empirical studies indicate significant time savings from automated synthesis methods. Screening tasks reveal a 50-90% reduction in time while maintaining sensitivity levels that meet or surpass those of human reviewers [

6,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18]. Wang and colleagues noted that a screening task could be completed in a single day, which would usually take 530 human hours [

6]. Data extraction tasks show 90-97% accuracy and cut down extraction time from hours to just minutes per study [

19,

33,

34].

Enhancements in Comprehensiveness and Consistency: Automated methods expand the inclusion scope by lowering the marginal costs of adding new sources [

35,

36]. Research shows that these methods decrease variability in screening decisions and data extraction compared to teams of human reviewers [

37,

38], resulting in fewer conflicts and improved adherence to inclusion criteria [

38,

39,

40].

Living Evidence Capabilities: Automated systems efficiently monitor ongoing literature and live systematic reviews [

41,

42]. Marshall and colleagues showcased robust continuous scanning and alert notifications through RobotReviewer Live [

41]. Academic knowledge graph frameworks allow for integrating new evidence at significantly reduced costs compared to traditional methods [

42,

43]. The development of living systematic reviews has become increasingly feasible through automation, addressing previous methodological challenges identified in recent surveys of the field [

20].

3.2. Identified Limitations and Concerns

Contextual Sensitivity Challenges: Present AI technologies, such as large language models, have limitations in recognizing contextual subtleties and relationships, especially those that involve implicit knowledge or narrative interpretation [

44,

45]. Research shows they might overlook subtle yet essential details related to implementation, even when explicitly instructed to focus on such factors [

46,

47]. This limitation is at odds with implementation science, which prioritizes contextual understanding [

11,

12]. It may lead to a preference for quantitative data over qualitative insights that are often essential for making implementation decisions [

48,

49].

Trustworthiness Concerns: Large language models show notable deficiencies in reference accuracy [

28,

29], with GPT-4 reaching just 13.8% recall in systematic review reference retrieval tasks [

29]. The "hallucination" phenomenon poses risks of producing factually incorrect outputs that appear credible [

50,

51], while "black box" processing restricts transparency and auditability. These shortcomings weaken the transparency and methodological rigor required by implementation science and threaten the stakeholder trust vital for collaborative decision-making.

Concerns about Equity and Representation: Automated systems can reflect and even intensify existing biases found in the literature and the algorithms themselves [

23,

24]. Technical requirements may establish new technological divides [

52], which could disadvantage organizations or communities that lack sufficient infrastructure or expertise. This situation goes against the principles of implementation science that advocate for health equity and context-sensitive practices [

53].

Table 1 systematically compares these benefits and concerns across key dimensions relevant to implementation science.

Figure 2 presents this comparative assessment visually through a radar chart that plots current automated synthesis performance against implementation science requirements across nine critical dimensions. The analysis reveals significant strengths in time efficiency, living evidence capabilities, and consistency, where automated methods meet or exceed field requirements. However, critical gaps emerge in contextual sensitivity, trustworthiness, and stakeholder engagement, where current capabilities fall substantially short of implementation science needs. This visual analysis demonstrates that successful integration requires targeted approaches to address these limitations while leveraging demonstrated strengths.

3.3. EPIS-Guided Integration Framework

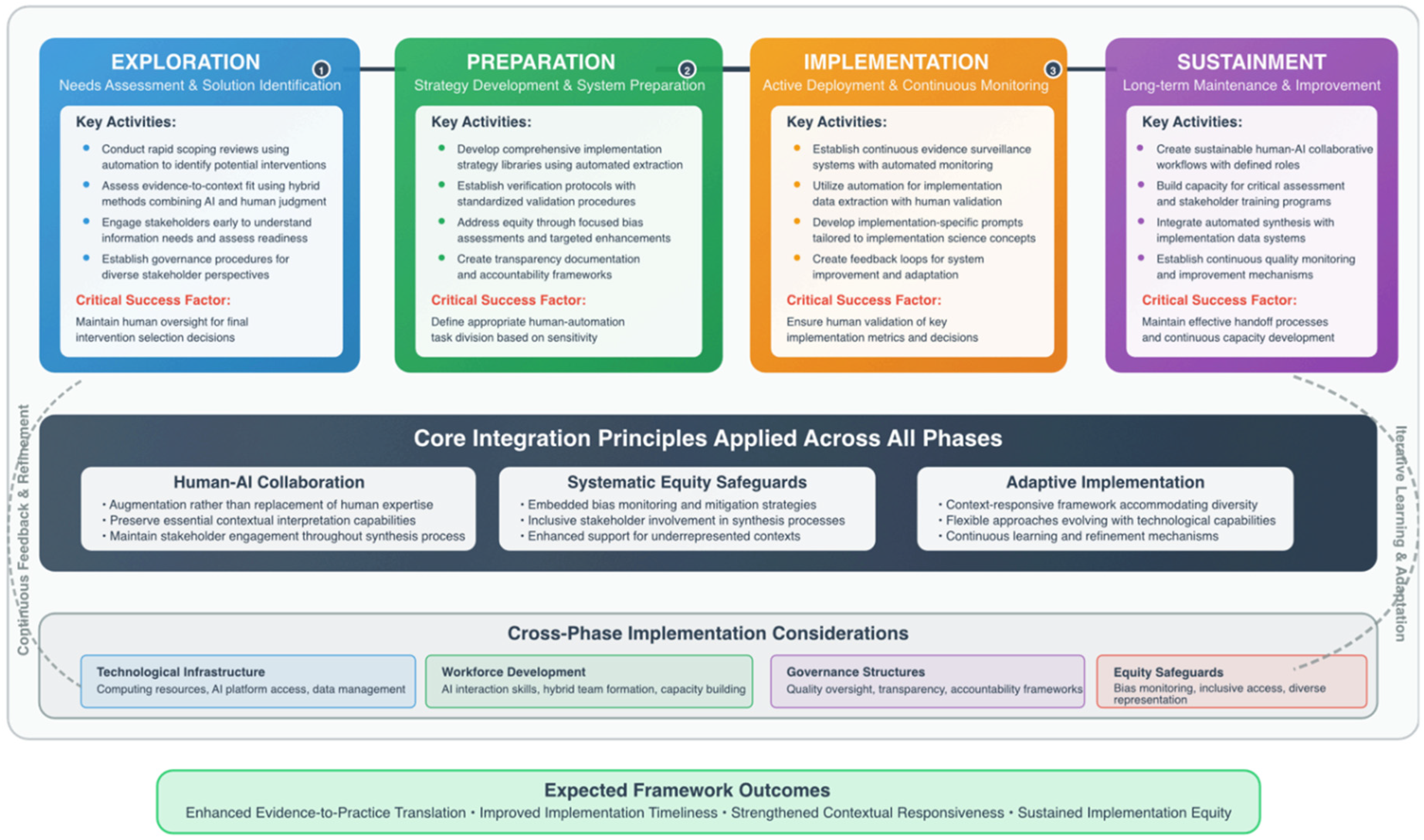

Our comprehensive framework is organized by EPIS implementation phases, providing detailed guidance for each stage while emphasizing the core principles that ensure successful integration (

Figure 3).

3.3.1. Framework Overview

The framework tackles the primary issue of incorporating automated synthesis methods into implementation science by creating a systematic approach that upholds field values while utilizing technological resources [

11,

12]. Instead of suggesting that automation completely replaces traditional synthesis methods, the framework views integration as a meticulously planned process that develops across various phases, each defined by unique objectives, activities, and success indicators.

The framework's architecture mirrors the focus of implementation science on systematic, evidence-based methods for changing practices [

1,

22]. Each phase builds on prior achievements and lays the groundwork for future stages, ensuring a seamless transition from the initial needs assessment to ongoing sustenance. The EPIS framework serves as the theoretical underpinning for this stepwise strategy [

13], acknowledging that organizations begin their journey toward automating synthesis from different starting points and possess various capabilities.

3.3.2. Phase-Specific Implementation Guidance

The Exploration phase lays the groundwork for effective integration by merging automated capabilities with human expertise in assessing needs and identifying interventions [

54,

55]. This phase places significant importance on the engagement of stakeholders and the planning of governance [

53], highlighting that the successful adoption of automated synthesis necessitates wide organizational backing and well-defined accountability structures from the beginning. Key activities include conducting rapid scoping reviews using automation to identify potential interventions, assessing evidence-to-context fit using hybrid methods combining AI and human judgment, engaging stakeholders early to understand information needs and assess readiness, and establishing governance procedures for diverse stakeholder perspectives. The critical success factor is maintaining human oversight for final intervention selection decisions that require contextual comprehension.

The shift from Exploration to Preparation marks a pivotal moment when organizations decide on particular automated synthesis methods, informed by contextual evaluations and stakeholder feedback. During the Preparation phase, these decisions are put into action through the organized development of strategies and the creation of necessary infrastructure [

35,

36]. This phase combines technical readiness with the protection of equity [

23,

24], ensuring automated systems are designed to enhance, rather than detract from, the commitment of implementation science to serve diverse populations and contexts. Key activities include developing comprehensive implementation strategy libraries using automated extraction, establishing verification protocols with standardized validation procedures, addressing equity through focused bias assessments and targeted enhancements, and creating transparency documentation and accountability frameworks. The critical success factor is defining an appropriate human-automation task division based on sensitivity and stakes.

The Implementation phase transition signifies the move from preparation to active deployment. It necessitates a careful balance between utilizing automation for efficiency gains [

6,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18] and upholding quality standards through human oversight [

50,

51]. This phase focuses on ongoing monitoring and adaptive refinement, acknowledging the need to continuously validate automated synthesis performance against implementation science requirements [

44,

45,

46,

47]. The living evidence capabilities established during this phase [

20,

41,

42] are crucial for pinpointing necessary adjustments and averting quality degradation over time. Key activities include establishing continuous evidence surveillance systems with automated monitoring, utilizing automation for implementation data extraction with human validation, developing implementation-specific prompts tailored to implementation science concepts, and creating feedback loops for system improvement and adaptation. The critical success factor is ensuring human validation of key implementation metrics and decisions

The sustainment phase transition emphasizes incorporating automated synthesis capabilities into organizational routines and institutional frameworks [

30,

31]. This last phase tackles the vital issue of sustaining innovation benefits while developing a lasting capacity for continuous quality assurance and system evolution. During this phase, merging automated synthesis with current implementation data systems establishes robust information ecosystems that enhance long-term organizational efficiency while safeguarding the human expertise necessary for contextual interpretation [

11,

12]. Key activities include creating sustainable human-AI collaborative workflows with defined roles, building capacity for critically assessing automated synthesis through training and guidance, integrating automated synthesis with implementation data systems, and establishing continuous quality monitoring and improvement mechanisms. The critical success factor is maintaining effective handoff processes and continuous capacity development.

3.3.3. Core Principles Integration

Three fundamental principles guide every implementation phase, ensuring that the integration of automated synthesis remains true to the values of implementation science, irrespective of unique organizational settings or technological frameworks.

Human-AI Collaboration principles direct decision-making throughout the framework by defining clear distinctions between suitable automated tasks and those requiring human involvement [

56,

57]. This principle helps avoid the frequent trap of either excessively depending on automation in situations requiring human judgment or not fully utilizing automation in scenarios where efficiency can be enhanced without sacrificing quality [

30,

31].

Systematic Equity Safeguards are ingrained rather than just additional factors, necessitating organizations to focus on bias monitoring, inclusive stakeholder engagement, and diverse representation throughout every implementation phase [

23,

24,

32]. These safeguards function by proactively identifying potential inequities, systematically monitoring automated synthesis outputs for bias indicators, and maintaining ongoing engagement with stakeholder communities that synthesis decisions could impact.

Adaptive implementation principles allow the framework to adjust to various organizational settings and advancing technological capabilities while upholding essential quality standards [

11,

12]. This principle acknowledges the swift evolution of automated synthesis technologies [

6,

7,

8,

9,

10], necessitating implementation strategies that can integrate new features without complete system redesign.

3.3.4. Implementation Considerations

The integration process demands coordinated focus across four cross-phase implementation domains, as depicted in the framework's implementation considerations panel. The requirements for technological infrastructure go beyond merely acquiring software; they also include the development of a comprehensive ecosystem, which involves computing resources, data management systems, security protocols, and the ability to integrate with current organizational systems [

6,

7,

8,

9,

10]. It's essential to plan these infrastructure considerations starting from the Exploration phase and to refine them during implementation to ensure the organization has sufficient capacity to meet its needs while addressing possible technological gaps.

Workforce development signifies an ongoing commitment from the organization that covers all implementation phases. It starts with assessing existing capabilities during the Exploration phase and continues with constant capacity building through Sustainment [

30,

31]. This area tackles the vital issue of enhancing organizational competence in human-AI collaboration while maintaining key expertise in implementation science. Successful workforce development necessitates a coordinated focus on technical skill enhancement, change management, and professional development paths that acknowledge the dynamic nature of implementation science practice, all while avoiding skill atrophy.

Governance frameworks should be set up promptly and refined regularly to provide adequate oversight and accountability during the adoption of automated synthesis [

50,

51]. These frameworks cover quality assurance, transparency standards, and stakeholder engagement protocols that uphold implementation science principles while considering technological strengths and constraints. The success of governance relies on well-defined roles, systematic quality assessments, and flexible procedures capable of addressing new challenges like reference accuracy problems or concerns around stakeholder trust.

Equity safeguards serve as both fundamental principles and practical requirements, necessitating focused efforts to prevent bias, ensure inclusive access, and promote diverse representation at all stages and areas [

23,

24,

32]. These safeguards involve established protocols for monitoring automated synthesis outputs, engaging with underrepresented stakeholder communities, and creating mechanisms to tackle any inequities that may arise during implementation. By spanning all phases, equity safeguards ensure that these factors shape technical decisions, organizational practices, and evaluation standards, rather than being considered only when issues occur, thereby reinforcing implementation science's core commitment to health equity and responsiveness to context.

4. Discussion

4.1. Implications for Implementation Science Practice

Research shows that automated synthesis methods hold transformative potential for overcoming ongoing challenges in implementation science, necessitating careful consideration of field-specific values and needs [

1,

5]. The reported capabilities for reducing time by 50-95% across various studies [

6,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18] signify more than slight efficiency improvements; they mark a significant shift in the time dynamics of translating evidence into practice, potentially transforming the operation of implementation science.

This acceleration tackles a fundamental contradiction in implementation science. While the field emphasizes evidence-based practice, the lengthy timelines often needed for thorough evidence synthesis clash with the urgent demands of decision-making in implementation [

2,

3]. Organizations that adopt evidence-based practices often encounter regulatory deadlines, funding cycles, or emergencies requiring prompt action. When the synthesis process can take months or even years, implementation decisions may proceed based on incomplete or outdated evidence. This situation undermines the core principle that practice should rely on up-to-date, comprehensive evidence.

The ability to synthesize living evidence [

20,

41,

42] offers a major opportunity for advancing implementation science. This capability facilitates a shift from static, one-time synthesis to dynamic, ongoing evidence monitoring that can assist adaptive implementation strategies. This function is particularly beneficial in rapidly changing fields where new evidence is constantly arising, in crisis situations where advice must adapt to new information, and in innovative intervention areas where initial evidence may be sparse yet is anticipated to grow quickly.

Nevertheless, the recognized limitations in contextual sensitivity [

44,

45,

46,

47] and reference accuracy [

28,

29] pose essential challenges to the foundational epistemological commitments of implementation science. Unlike conventional efficacy research, implementation science focuses on comprehending whether interventions are effective, how they operate, for whom they are effective, under what circumstances, and with which modifications [

11,

12]. This focus on context necessitates synthesis methods that capture the subtle nuances of implementation environments, mechanisms, and moderating factors critical for successful translation.

The possibility that automated synthesis could consistently ignore or misinterpret qualitative evidence [

46,

47] is a significant issue, especially as implementation science increasingly values mixed-methods approaches and realist evaluation frameworks [

48,

49]. Qualitative implementation research offers vital insights regarding context, mechanisms, and stakeholder perspectives that quantitative studies often miss. Should automated synthesis techniques unwittingly favor the processing of more straightforward quantitative data, they could compromise the methodological pluralism and contextual depth that implementation science seeks to uphold.

4.2. Theoretical Contributions and Field Evolution

This framework makes a notable theoretical contribution to implementation science by introducing the first systematic method for integrating automated synthesis techniques while upholding the field's essential values and epistemological commitments. The EPIS-guided structure [

13] presents a fresh application of recognized implementation theory to technology adoption within the discipline, illustrating how the principles of implementation science can inform the field's development. The framework builds upon extensive validation of the EPIS framework across diverse implementation contexts [

25] and extends its application to technology integration.

The proposed human-AI collaboration model redefines common beliefs about automation as purely a replacement technology. Instead, it views automated synthesis as a means to enhance human capabilities while maintaining essential skills like contextual interpretation and stakeholder engagement [

56,

57]. This perspective is consistent with the principles of implementation science, highlighting the significance of participatory approaches and acknowledging that successful implementation relies on human relationships, trust, and contextual understanding, all of which cannot be automated.

The framework's consistent focus on equity considerations [

23,

24,

32] during every phase of implementation marks a significant progress in addressing technological equity in implementation science. Instead of regarding equity as an afterthought or additional consideration, the framework integrates equity safeguards as essential requirements for ethical automated synthesis implementation. This strategy recognizes that technological solutions can unintentionally worsen existing inequities if they are not thoughtfully designed and implemented with clear attention to the varied needs and contexts of stakeholders.

The multi-dimensional assessment approach presented here offers a methodological contribution for evaluating other technological innovations in implementation science. Conducting a systematic comparison of benefits and risks across relevant dimensions provides a template for future technology assessments that respects field values while objectively assessing the potential for innovation.

4.3. Implementation Challenges and Organizational Considerations

This analysis highlights the complexities of effectively integrating automated synthesis across various organizational settings. The technological infrastructure needed [

6,

7,

8,

9,

10] goes beyond merely acquiring software; it involves complex ecosystem requirements, such as computing resources, data management systems, technical skills, and continuous maintenance support. Numerous implementing organizations, especially smaller nonprofits, community-based groups, and resource-limited health systems, may lack the infrastructure to sustain advanced automated synthesis functionalities.

Figure 4.

Technology Infrastructure Architecture for Automated Evidence Synthesis. The layered architecture shows five integrated components: external services (blue), core processing platform (purple), data management (green), security and integration (red), and user interfaces (orange). Data flow arrows (green and black) indicate information movement between layers.

Figure 4.

Technology Infrastructure Architecture for Automated Evidence Synthesis. The layered architecture shows five integrated components: external services (blue), core processing platform (purple), data management (green), security and integration (red), and user interfaces (orange). Data flow arrows (green and black) indicate information movement between layers.

This infrastructure gap poses a serious risk that automated synthesis could worsen, rather than alleviate, current disparities in access to synthesized evidence [

52]. Organizations with ample resources may substantially outpace others in evidence synthesis abilities, while those aiding vulnerable communities or functioning in resource-limited areas may become even more disadvantaged. Tackling this issue calls for collaborative initiatives to create shared resource frameworks, technical support programs, and accessible implementation strategies that ensure automated synthesis doesn't generate new kinds of technological inequality.

The workforce development needs highlighted in this analysis indicate that achieving successful automated synthesis goes beyond just technical training; it necessitates significant shifts in how implementation scientists view their roles and expertise [

30,

31]. The move toward human-AI collaboration calls for the development of new competencies while also preserving traditional critical appraisal skills, creating possible conflict between adopting innovations and maintaining existing expertise. Organizations must strategically navigate this transition to prevent skill attrition while enhancing new capabilities.

The governance challenges identified through this analysis underscore the necessity for new institutional frameworks that offer suitable oversight for automated synthesis, all while upholding the essential transparency and accountability standards of implementation science. Conventional peer review and quality assurance methods might not adequately assess automated synthesis outputs, necessitating the creation of new validation techniques, audit processes, and accountability systems [

58].

4.4. Framework Limitations and Future Development Needs

Although this framework offers thorough guidance for integrating automated synthesis, there are key limitations to consider. It serves as a conceptual contribution grounded in existing evidence, rather than being empirically validated within the field of implementation science. Systematic testing through pilot implementations, comparative effectiveness studies, and stakeholder feedback is necessary to assess the practical effectiveness of these recommendations and to identify needed improvements.

The fast evolution of AI technology suggests that the capabilities and limitations outlined in this analysis could change rapidly, necessitating regular updates to the framework to stay relevant. Additionally, the framework's focus on current large language model capabilities may become less relevant as new AI technologies are developed or existing ones advance in context awareness and reference precision.

The framework emphasizes organizational-level implementation, which might overlook system-level factors that can affect the adoption of automated synthesis throughout the broader field of implementation science. Key stakeholders, including professional societies, funding agencies, academic institutions, and policymakers, significantly influence technology adoption trends that go beyond the choices made by individual organizations.

Although the equity considerations are thorough, they need continuous attention and improvement as the implementation of automated synthesis uncovers new biases or exclusions that may not be visible in current theoretical analyses. Equity safeguards within the framework are initial strategies that should be adapted based on practical empirical evidence regarding their effectiveness.

4.5. Research Priorities and Future Directions

The research agenda arising from this analysis covers various areas that need coordinated exploration to facilitate the responsible adoption of automated synthesis in implementation science. Method development research should focus on enhancing automated systems' capability to capture contextually relevant factors for implementation [

11,

12,

44,

45,

46,

47] and creating strategies to blend qualitative insights from implementation with automated synthesis methods [

48,

49]. This effort necessitates a strong partnership between implementation scientists and AI researchers to ensure that technological advancements cater to the specific needs of implementation science, rather than just general synthesis requirements.

Research on implementation outcomes is vital for assessing if the theoretical advantages of automated synthesis result in tangible enhancements in implementation practices [

1]. Studies on comparative effectiveness that explore traditional versus automated synthesis techniques in real-world scenarios can help pinpoint where automation is most beneficial and reveal situations where conventional methods excel. This research should evaluate not only efficiency metrics but also the quality of decisions, stakeholder satisfaction, and final implementation results.

Research on stakeholder perspectives necessitates a systematic exploration of how various implementation stakeholders interpret and utilize automated synthesis products [

53], the factors affecting trust and acceptance of automated methods [

50,

51], and strategies for effectively integrating diverse viewpoints into the development and assessment of automated methods [

56,

57]. This inquiry should investigate perspectives from various organizational settings, stakeholder roles, and cultural contexts to guarantee that automated synthesis development meets the needs of different implementation communities.

Research on governance and ethics needs to develop frameworks that enhance implementation equity through automated synthesis rather than detract from it [

23,

24]. It should also set transparency standards suitable for applications in implementation science [

50,

51] and clarify the distribution of responsibility and accountability in human-AI collaborative synthesis [

30,

31]. This research must address both the governance needs at the organizational level and the policy requirements at the field level that can inform the responsible adoption of automated synthesis.

Research on long-term impacts should explore how adopting automated synthesis affects the evolution of implementation science. This includes examining changes in methodological approaches, theoretical frameworks, and patterns of knowledge accumulation. Gaining insights into these field-level effects is crucial to guarantee that automated synthesis contributes positively to the intellectual growth and practical effectiveness of implementation science.

Conclusion

Automated evidence synthesis methods offer a transformative potential for implementation science, evidenced by their ability to cut synthesis time by 50-95%. They also facilitate ongoing evidence monitoring, which could effectively bridge the gap between evidence production and the decision-making requirements in implementation. Nevertheless, notable challenges regarding contextual sensitivity, reference accuracy, and possible equity implications necessitate thoughtful integration strategies that uphold the fundamental values of implementation science, namely stakeholder engagement, contextual awareness, and equitable practices.

The EPIS-guided framework developed in this analysis offers a structured approach to navigate this integration challenge through systematic human-AI collaboration instead of replacement, comprehensive attention to equity safeguards, and phase-specific implementation guidance. Achieving success requires coordinated focus on technological infrastructure, workforce development, governance innovation, and equity protection across various organizational contexts.

Implementation science is at a pivotal point where active involvement in developing automated synthesis can mold these technologies to meet the field's specific needs while setting necessary boundaries and protections. The field's reaction will influence whether automated synthesis strengthens or weakens implementation science's ability to effectively and fairly close the evidence-to-practice gap.

The framework and recommendations outlined here establish a basis for responsible adoption, yet their true value relies on empirical validation, stakeholder feedback, and ongoing refinement informed by practical experiences. By carefully navigating this technological shift while adhering to fundamental principles, implementation science can enhance its capacity to foster more effective and equitable implementation of evidence-based interventions in various contexts and among diverse populations.

Acknowledgements

The author thanks colleagues at the Institute of Learning (IoL) at MBRU for their constructive feedback on drafts of this manuscript.

References

- Bauer MS, Damschroder L, Hagedorn H, Smith J, Kilbourne AM. An introduction to implementation science for the non-specialist. BMC Psychology. 2015;3(1):32. [CrossRef]

- Borah R, Brown AW, Capers PL, Kaiser KA. Analysis of the time and workers needed to conduct systematic reviews of medical interventions using data from the PROSPERO registry. BMJ Open. 2017;7(2):e012545. [CrossRef]

- Bastian H, Glasziou P, Chalmers I. Seventy-five trials and eleven systematic reviews a day: how will we ever keep up? PLOS Medicine. 2010;7(9):e1000326. [CrossRef]

- Landhuis E. Scientific literature: Information overload. Nature. 2016;535(7612):457-458. [CrossRef]

- Shojania KG, Sampson M, Ansari MT, Ji J, Doucette S, Moher D. How quickly do systematic reviews go out of date? A survival analysis. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2007;147(4):224-233. [CrossRef]

- Wang Z, Lin H, Zhang P, Yu L, Sun J. TrialMind: a human-machine teaming framework for evidence synthesis. JAMA Network Open. 2024;7(2):e2355683.

- Trad C, Mohamad El-Hajj H, Khanji MYG, Nasr R, Kahale LA, Akl EA. Artificial intelligence for abstract and full-text screening of articles for a systematic review. BMJ Evidence-Based Medicine. 2024;29(3):145-151.

- Sanghera R, Soltan AA, Jaskulski S, et al. Large language model ensemble for systematic review article screening: speed, accuracy and at scale. medRxiv. 2024.

- van de Schoot R, de Bruin J, Schram R, et al. An open source machine learning framework for efficient and transparent systematic reviews. Nature Machine Intelligence. 2021;3(2):125-133. [CrossRef]

- Cao C, Chi G, Ma Z, McCrae C, Bobrovitz N. Using large language models in systematic reviews: a generalizable framework for accelerating literature screening. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2024;167:153-169.

- Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, Kirsh SR, Alexander JA, Lowery JC. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: a consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implementation Science. 2009;4:50. [CrossRef]

- Nilsen P. Making sense of implementation theories, models and frameworks. Implementation Science. 2015;10:53. [CrossRef]

- Moullin JC, Dickson KS, Stadnick NA, Rabin B, Aarons GA. Systematic review of the Exploration, Preparation, Implementation, Sustainment (EPIS) framework. Implementation Science. 2019;14(1):1. [CrossRef]

- Tran VT, Riveros C, Ravaud P. Automation of systematic review screening using large language models. Artificial Intelligence in Medicine. 2023;141:102581.

- Guo E, Goh E, Barrow E, et al. Automated paper screening for clinical reviews using large language models: data analysis study. Journal of Medical Internet Research. 2023;25:e48996. [CrossRef]

- Gartlehner G, Wagner G, Grootendorst D, et al. Assessing the accuracy of machine learning assisted abstract screening with Claude: a pilot study. Research Synthesis Methods. 2023;14(6):763-769. [CrossRef]

- Przybyła P, Brockmeier AJ, Kontonatsios G, et al. Prioritising references for systematic reviews with RobotAnalyst: a user study. Research Synthesis Methods. 2018;9(3):470-488. [CrossRef]

- Rathbone J, Hoffmann T, Glasziou P. Faster title and abstract screening? Evaluating Abstrackr, a semi-automated online screening program for systematic reviewers. Systematic Reviews. 2015;4:80. [CrossRef]

- Khan H, Kiong JZH, Das A, et al. Assessment of large language models for data extraction in living systematic reviews. JAMA Network Open. 2025;8(1):e2453892.

- Akl EA, El Khoury R, Khamis AM, et al. The life and death of living systematic reviews: a methodological survey. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2023;156:11-21. [CrossRef]

- Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71. [CrossRef]

- Kislov R, Pope C, Martin GP, Wilson PM. Harnessing the power of theorising in implementation science. Implementation Science. 2019;14(1):103. [CrossRef]

- Budhwar K, Bitterman A. Towards a more equitable future: understanding and addressing bias in artificial intelligence for healthcare. Journal of Medical Systems. 2022;46(11):81.

- Chiang T, Roberts K, Perer A. Challenges in equity-centered research in machine learning for healthcare. medRxiv. 2022.

- Moullin JC, Dickson KS, Stadnick NA, Rabin B, Aarons GA. Systematic review of the exploration, preparation, implementation, sustainment (EPIS) framework. Implementation Science. 2019;14(1):1-16. [CrossRef]

- Damschroder LJ, Reardon CM, Widerquist MAO, Lowery J. The updated Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research based on user feedback. Implementation Science. 2022;17:75. [CrossRef]

- Powell BJ, Waltz TJ, Chinman MJ, et al. A refined compilation of implementation strategies: results from the Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change (ERIC) project. Implementation Science. 2015;10:21. [CrossRef]

- Khandelwal AR, Adhikari PR, Martinez D, Gordon C. AI-generated content in evidence synthesis: a study on accuracy, hallucination, and citations by large language models. Journal of Medical Internet Research. 2023;25:e49122.

- Morrison A, Polisena J, Husereau D, et al. Reference accuracy in the medical artificial intelligence literature: critical need for improvement. Journal of Medical Internet Research. 2023;25:e46265.

- Tsamados A, Aggarwal N, Cowls J, et al. The ethics of algorithms: key problems and solutions. AI & Society. 2022;37:215-230. [CrossRef]

- Parasuraman R, Manzey DH. Complacency and bias in human use of automation: an attentional integration. Human Factors. 2010;52(3):381-410. [CrossRef]

- Hassan M, Kushniruk A, Borycki E. Barriers to and facilitators of artificial intelligence adoption in health care: scoping review. JMIR Human Factors. 2024;11:e48633. [CrossRef]

- Liu Y, Liu C, Xu H, et al. Assessing the feasibility and accuracy of Claude-2 large language model for data extraction from randomized controlled trials: a proof-of-concept study. JMIR Medical Informatics. 2025;13(1):e52914. [CrossRef]

- Hamel C, Kelly SE, Thavorn K, et al. An evaluation of DistillerSR's machine learning-based prioritization tool for title/abstract screening -- impact on reviewer-relevant outcomes. BMC Medical Research Methodology. 2020;20:256. [CrossRef]

- Gorelik A, Ridley D, Shaffer R, et al. Modeling the cost and effectiveness of text mining for rapid systematic reviews. BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making. 2020;20:1-9. [CrossRef]

- Ali S, Swarup S, Wang H, et al. Separability as a practical indicator for machine learning automation potential in education-focused systematic reviews. Review of Educational Research. 2025;95(1):105-138.

- Wang Z, Nayfeh T, Tetzlaff J, et al. Error rates of human reviewers during abstract screening in systematic reviews. PLOS ONE. 2020;15(1):e0227742. [CrossRef]

- Ferdinands G, Schram R, de Bruin J, et al. Performance of active learning models for screening prioritization in systematic reviews: a simulation study. Systematic Reviews. 2023;12:38. [CrossRef]

- Ames HMR, Glenton C, Lewin S, et al. Accuracy and efficiency of machine learning-assisted risk-of-bias assessments in "real-world" systematic reviews. BMC Medical Research Methodology. 2022;22:288. [CrossRef]

- Qureshi R, Shaughnessy D, Gill KAR, et al. Are ChatGPT and large language models "the answer" to bringing us closer to systematic review automation? Systematic Reviews. 2023;12:72. [CrossRef]

- Marshall IJ, Wallace BC, Noel-Storr A, et al. Generating living, breathing evidence syntheses: RobotReviewer live for continuous updating. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2022;144:126-133. [CrossRef]

- Shemilt I, Noel-Storr A, Thomas J, et al. Cost and value of different approaches to searching for and identifying studies for a systematic evidence map of research on COVID-19. Research Synthesis Methods. 2021;12(6):742-754. [CrossRef]

- Wallace BC, Small K, Brodley CE, Lau J, Trikalinos TA. Deploying an interactive machine learning system in an evidence-based practice center: abstrackr. In: Proceedings of the 2nd ACM SIGHIT International Health Informatics Symposium. 2012:819-823. [CrossRef]

- Oami T, Suwa H, Oshima K, et al. The efficiency and efficacy of large language models for title and abstract screening in systematic reviews. Systematic Reviews. 2024;13(1):49.

- Sun L, Kim CJ, Baumer EP, et al. Using large language models in software engineering: an exploration of use cases and implications. Studies in Big Data. 2025;117:1-28.

- Liu X, Shi J, Maglalang DD, et al. Qualitative data analysis using large language models: an examination of ChatGPT performance. Journal of Technology in Behavioral Science. 2023;8(3):429-439.

- Bittermann A, Grant S. Exploring the potential of large language models in qualitative data analysis: promises and perils. International Journal of Qualitative Methods. 2024;23:1-14.

- Greenhalgh T, Pawson R, Wong G, et al. Realist methods in review in action: the case of complex health interventions. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2013;69(7):1453-1464. [CrossRef]

- Paparini S, Green J, Papoutsi C, et al. Case study research for better evaluations of complex interventions: rationale and challenges. BMC Medicine. 2020;18(1):301. [CrossRef]

- Touvron H, Lavril T, Izacard G, et al. LLaMA: Open and efficient foundation language models. arXiv preprint. 2023;arXiv:2302.13971. [CrossRef]

- Ji Z, Lee N, Frieske R, et al. Survey of hallucination in natural language generation. ACM Computing Surveys. 2023;55(12):1-38. [CrossRef]

- Owens B. The potential and pitfalls of AI for global health equity. The Lancet Digital Health. 2023;5(3):e116-e117.

- Wieringa S, Engebretsen E, Heggen K, Greenhalgh T. How and why AI explanations matter in medicine: interview study of the sociotechnical context. Journal of Medical Internet Research. 2023;25:e49197. [CrossRef]

- Edwards P, Green S, Clarke M, et al. ADVISE: automated data-driven value of information synthesis to evaluate policy decisions in sustainable development. Frontiers in Research Metrics and Analytics. 2023;8:1123996.

- Bienefeld N, Keller E, Grote G. Human-AI teaming in critical care: a comparative analysis of data scientists' and clinicians' perspectives on AI augmentation and automation. Journal of Medical Internet Research. 2024;26:e50130. [CrossRef]

- Danaher J. The threat of algocracy: reality, resistance and accommodation. Philosophy & Technology. 2016;29:245-268. [CrossRef]

- Farzaneh N, Williamson CA, Gryak J, Najarian K. Collaborative strategies for deploying AI-based physician decision support systems: challenges and deployment approaches. npj Digital Medicine. 2023;6:137.

- Shea BJ, Reeves BC, Wells G, et al. AMSTAR 2: a critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include randomised or non-randomised studies of healthcare interventions, or both. BMJ. 2017;358:j4008. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).