1. Introduction

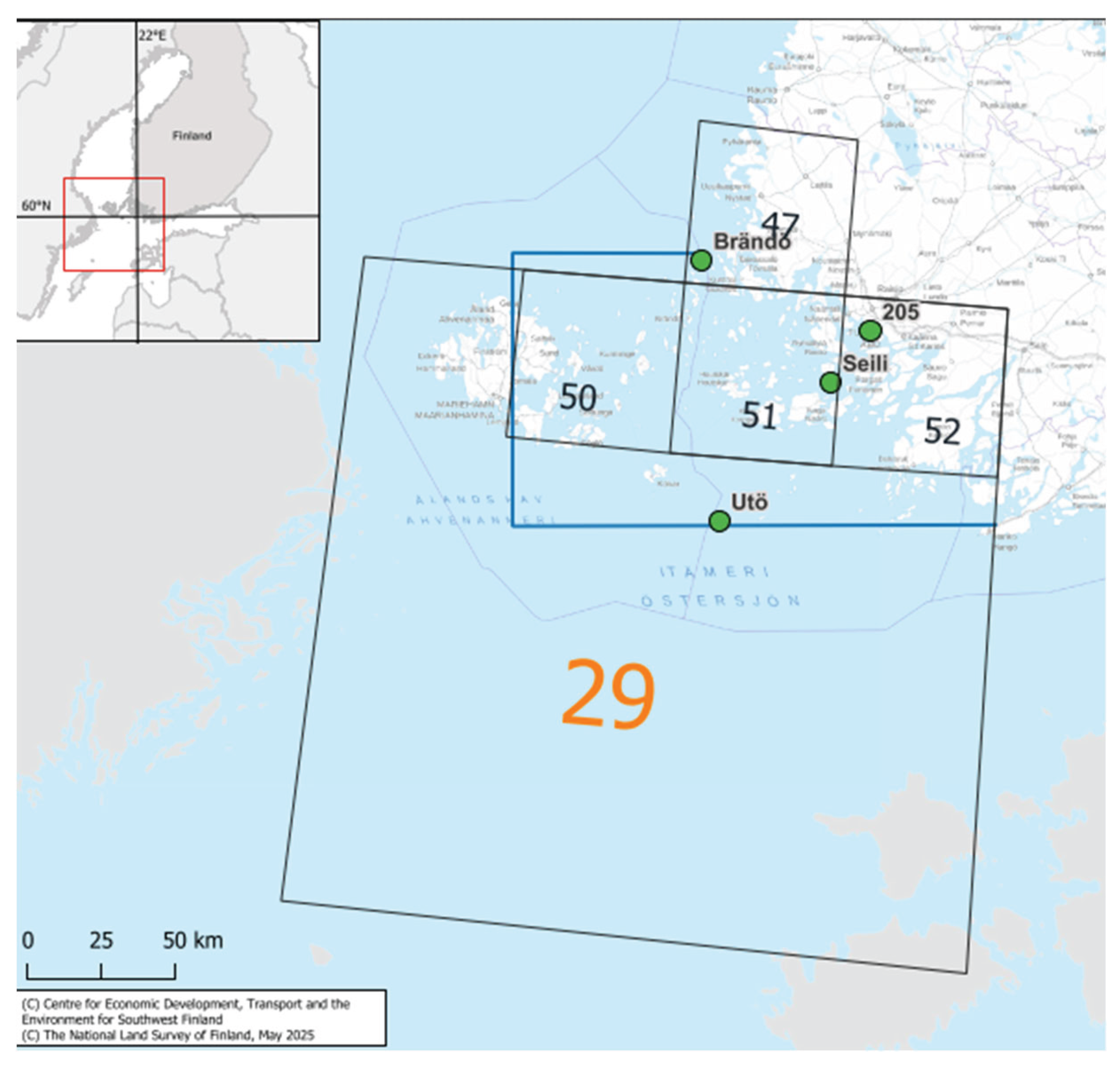

Eutrophication is recognized as the greatest threat to freshwater and coastal marine ecosystems globally [

1], due to its well-documented adverse impacts on aquatic ecosystem structure and functioning. This is also reflected in the current ecological status of the Baltic Sea, with particular emphasis on the Archipelago Sea, located in the northern Baltic Sea [

2]. Achieving improved conditions often requires substantial reductions in nutrient loading [

3]. However, since such reductions are generally challenging to implement, various action plans have proposed the removal of nutrients bound in aquatic biomass as a complementary measure. The underlying idea is that this could partially compensate for the required nutrient reductions. This approach has also been considered in efforts to improve the ecological status of the Archipelago Sea [

4].

An alternative strategy that has been proposed involves intensifying fishing activities to facilitate the removal of nutrients—primarily phosphorus and nitrogen—bound in fish biomass. However, it has also been suggested that, in many cases, retaining fish populations in the ecosystem may be more beneficial for the marine nutrient cycle. More effective reductions of nutrient availability in eutrophic systems plausibly favour the ‘protection’ rather than removal of fish to allow sequestration of internal nutrients into biomass of macrobiota rather than microphytic organisms [

5,

6].

All living organisms inherently contain nutrients incorporated into their biomass, collectively forming internal nutrient pools within ecosystem sinks [

7]. Unless physically or biologically translocated, these biomass-stored nutrients return to the surrounding environment upon death and decomposition. In aquatic ecosystems, fish can function both as temporary nutrient sinks and as potential sources of phosphorus, due to the accumulation of nutrients in their biomass. While fish often represent a substantial internal nutrient pool—frequently acting as a nutrient "sink" [

8]—their role in internal nutrient recycling may be relatively minor, owing to comparatively slow biomass turnover rates; for example, 367 days for fish versus 3.2 days for phytoplankton [

6,

7].

When evaluating the effectiveness of various measures aimed at reducing eutrophication, conclusions are often based on overly simplistic comparisons—for example, contrasting the amount of phosphorus removed through fish harvesting with phosphorus inputs from riverine sources [

9]. However, impact assessments should also consider what would happen to the nutrients contained in fish if they remained within the ecosystem's biogeochemical cycles instead of being extracted through fishing. Additionally, it is important to assess how from fish—such as fecal matter and excretions—affect the ecological status of the marine environment. In all cases, establishing a comprehensive and detailed nutrient budget for the target area is essential. This budget should be appropriately linked to the nutrient dynamics of fish populations within the specific ecological context.

This study involved compiling and updating data used to construct the phosphorus budget of the Archipelago Sea. As in this and previous nutrient studies conducted in the region [

10,

11], total phosphorus (TP) was used as a proxy for the nutrients available to planktonic organisms. Emphasis was placed on assessing the size of phosphorus pools associated with fish populations in the Archipelago Sea, using biomass data and species-specific phosphorus content. The results provide insight into the role of fish in the regional phosphorus budget and underscore their significance in long-term nutrient storage.

To support the assessment, a bioenergetic modeling approach [

12] was employed for Baltic herring (

Clupea harengus membras) and European perch (

Perca fluviatilis) to estimate species-specific food consumption. The difference between the phosphorus intake via diet and the phosphorus retained in somatic growth was used to quantify the annual phosphorus recycling mediated by these fish. Bioenergetics models are frequently applied to understand growth or resource use by fishes under specified environmental conditions and can be scaled up to the ecosystem or community level if informed by knowledge of population dynamics [

13].

3. Results

3.1. The Phosphorus Pool in the Water Column of the Archipelago Sea

The phosphorus pool in the water of the Archipelago Sea varies seasonally. In the 2000s, the highest amount of phosphorus was observed during winter (January 1–March 31), totaling 6,764 tons, and the lowest in early summer (May 15–June 15), after the spring bloom, at 4,789 tons. During the ecological classification period (July 1–September 7), the average phosphorus content in the water was 5,494 tons. The average total phosphorus concentrations in the entire water column were 30.7 µg/l in winter, 21.8 µg/l in early summer, and 25.0 µg/l during the ecological classification period. The seasonal reduction from the winter maximum to the early summer minimum—amounting to 1,975 tons—is primarily attributed to the spring phytoplankton bloom, during which large amounts of phosphorus are taken up by primary producers and subsequently transferred to the sediments through the sedimentation of organic matter.

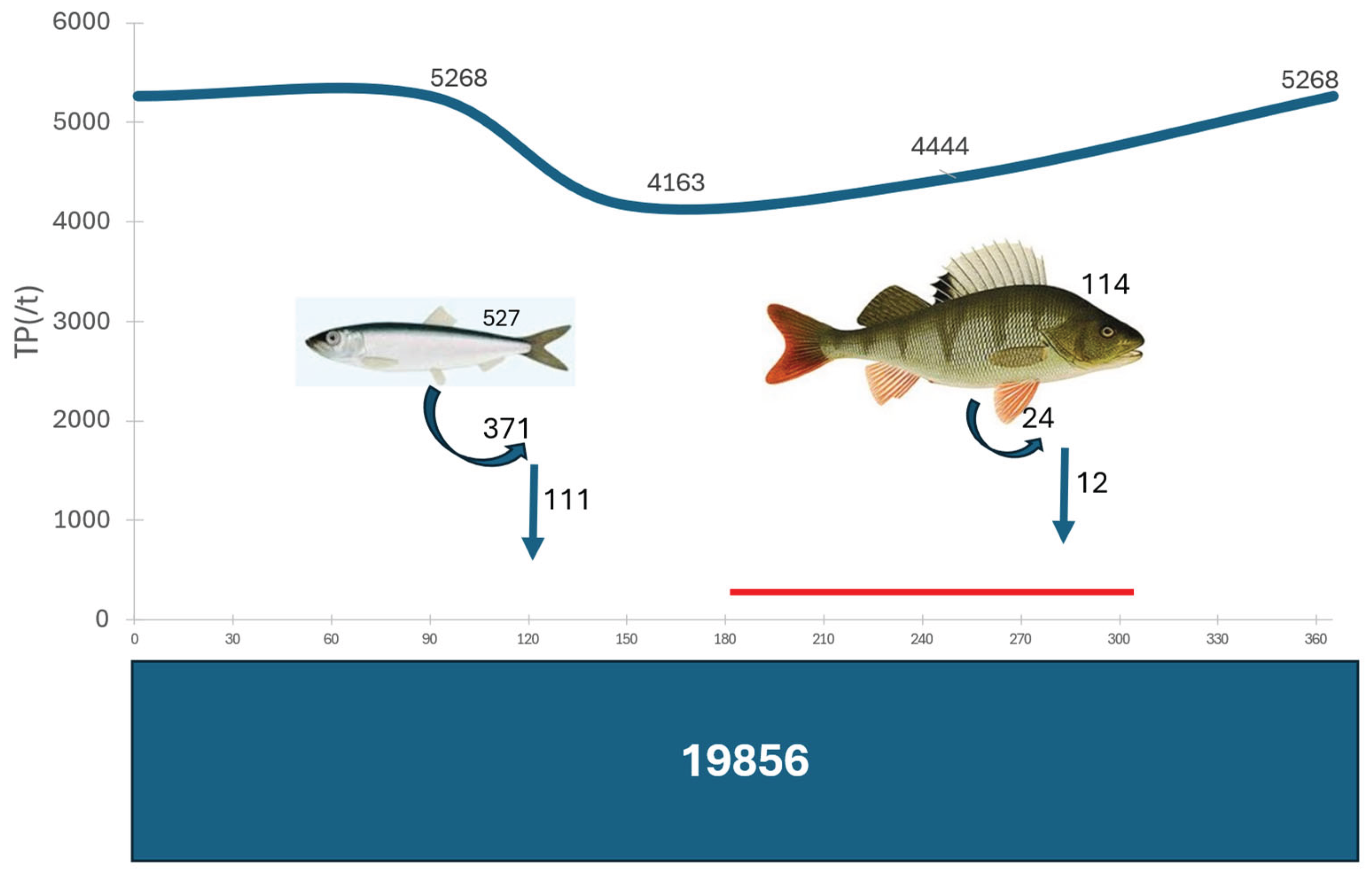

In the years 2001–2024, the average total phosphorus concentrations in the Inner Archipelago were 28% higher in winter compared to the average for the years 1983–1989. The corresponding difference was 15% in early summer and 23.6% during the ecological classification period. Based on the observed phosphorus concentrations, estimates were derived for the total phosphorus pool in the water phase of the Archipelago Sea during the late 1980s. The estimated phosphorus pools were 5,268 tons in winter, 4,163 tons in early summer, and 4,444 tons during the ecological classification period. The seasonal decline in phosphorus mass from winter to early summer amounted to 1,122 tons.

3.2. Fish Catches in the Archipelago Sea and Their Associated Phosphorus Contents

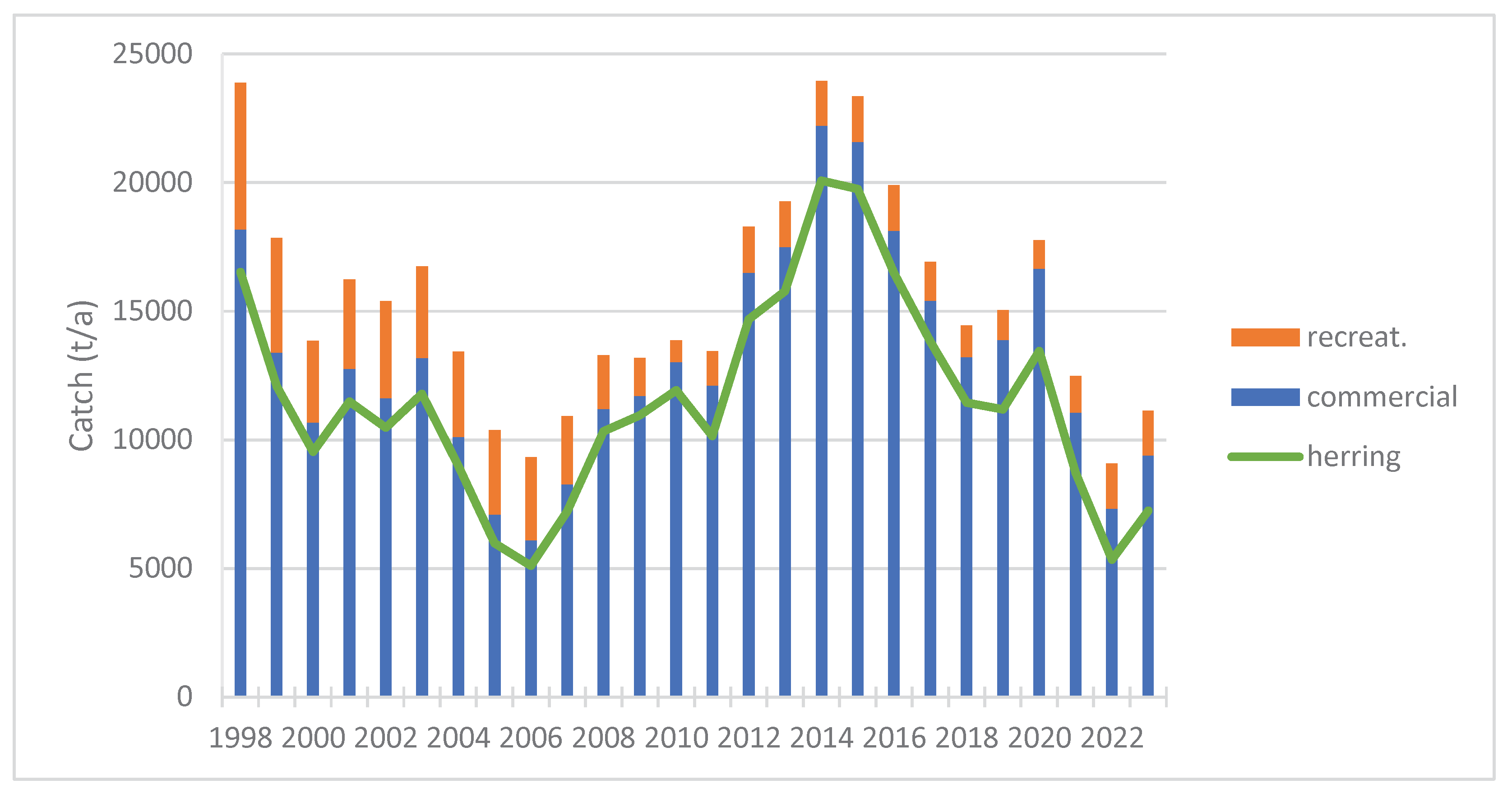

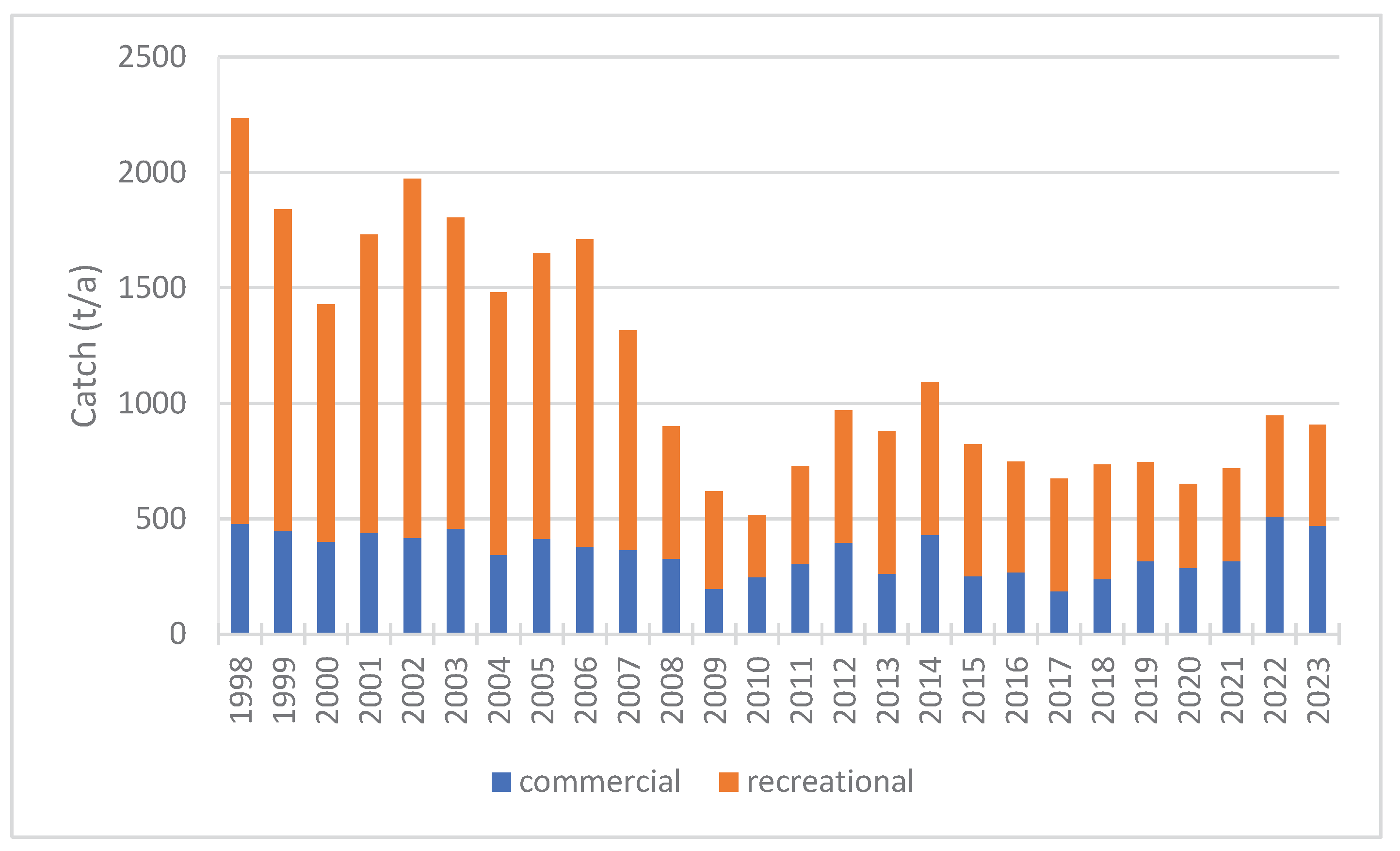

The total annual fish catch in the Archipelago Sea during the years 1998–2023 averaged 15,516.5 tons (median: 14,754.5 tons; minimum: 9,085 tons; maximum: 23,952 tons; see

Figure 6). On average, 73.1% of this catch consisted of commercially caught Baltic herring. The annual fish catch contained an average of 83.4 tons of phosphorus (median: 78.5 tons; minimum: 51.7 tons; maximum: 136.1 tons).

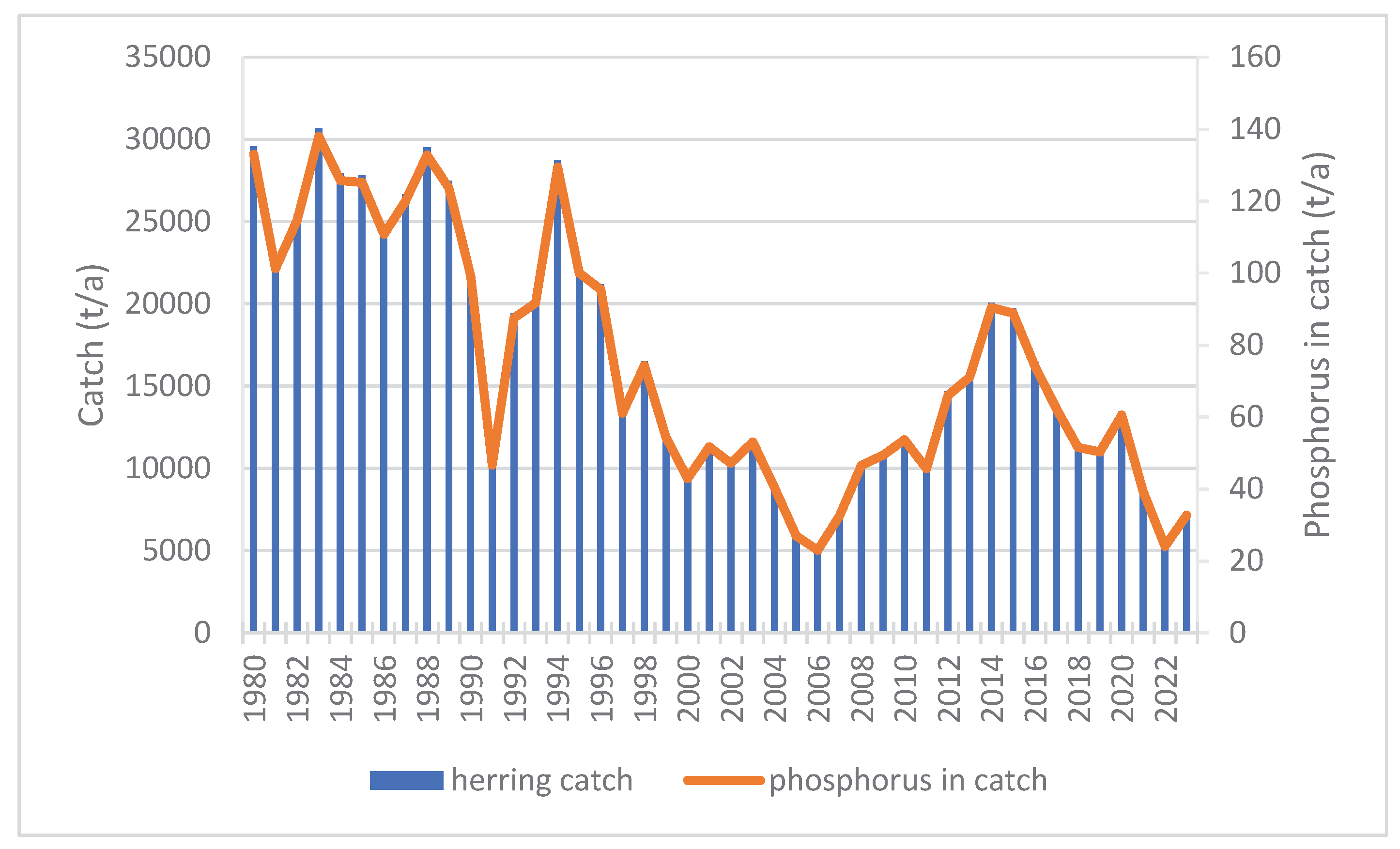

Over a longer period (1980–2023), the annual herring catch averaged 16,607 tons (median: 14,250.5 tons; minimum: 5,105 tons; maximum: 30,651 tons; see

Figure 7). The amount of phosphorus contained in the annual Baltic herring catch during this period averaged 74.7 tons (median: 64.1 tons; minimum: 23.0 tons; maximum: 137.9 tons; see

Figure 7).

In the 1980s, average Baltic herring catches were more than three times higher than in the 2020s (27,217 t/a vs. 8,690 t/a). Accordingly, over three times more phosphorus was removed through the herring catch during that time (122.5 t/a vs. 39 t/a).

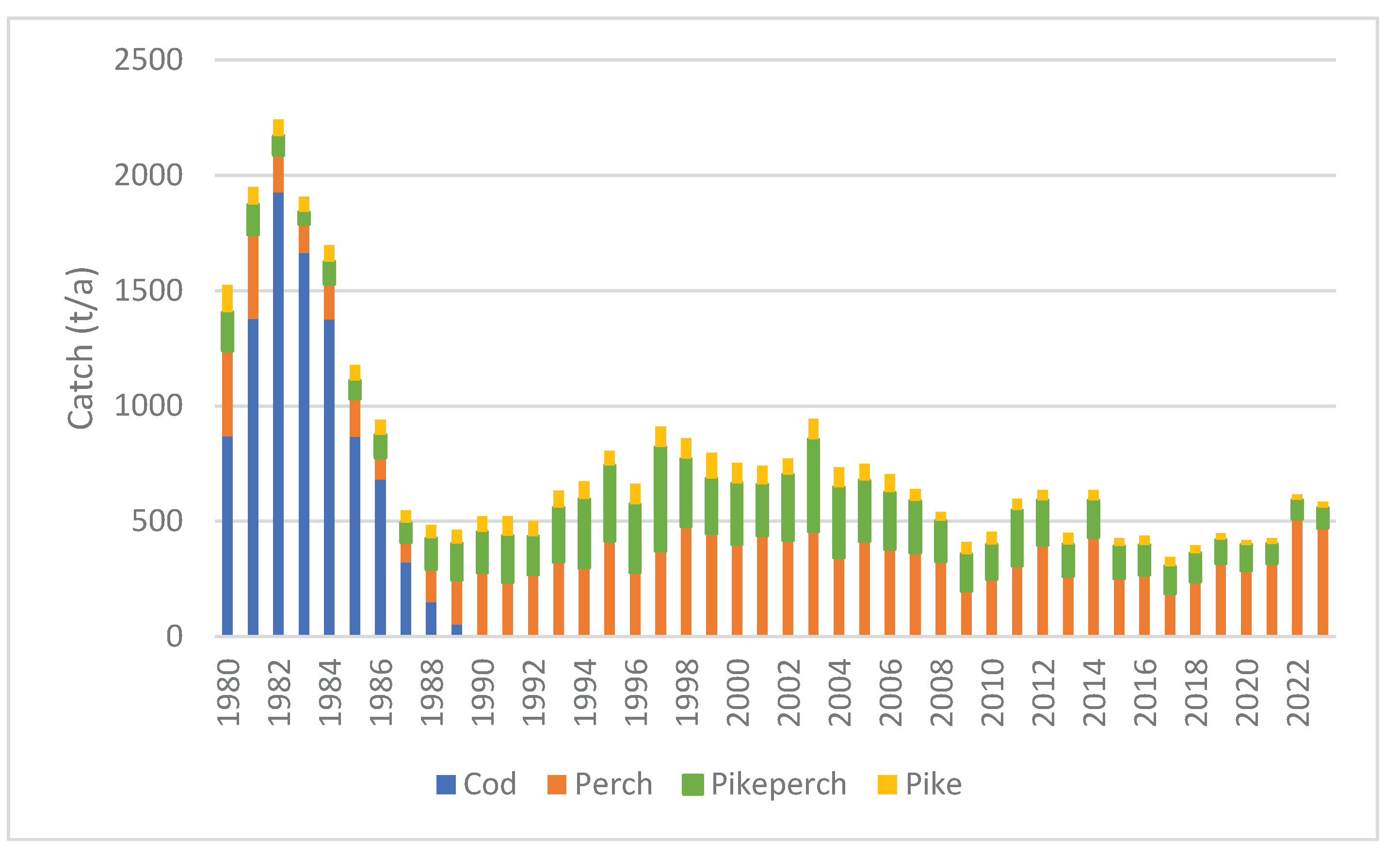

The share of predatory fish in commercial fishery catches has fluctuated considerably between 1980 and 2023 (

Figure 8). Notably, no cod has been caught since 1989. The annual catch of pikeperch was 400 tons in 2003 but began to decline thereafter, averaging only 92 tons in the 2020s. Similarly, the catch of pike has been decreasing since the early 2000s.

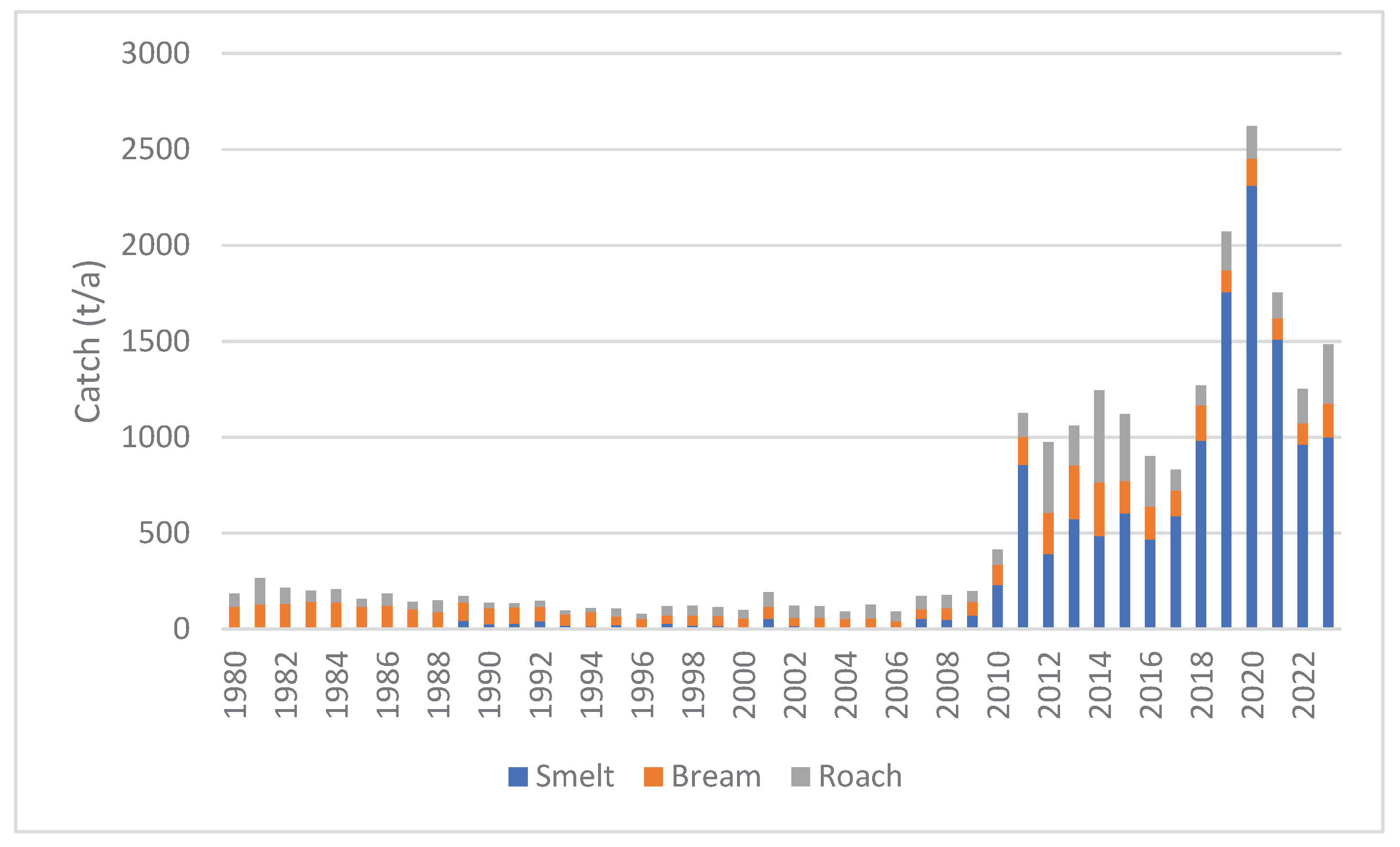

The commercial catches of species typically targeted in so-called management fishing (smelt, roach, and bream) remained modest until the early 2010s (

Figure 9). During the 2010s, however, smelt catches increased rapidly, reaching a record high of 2,311 tons in 2020. That year, the smelt catch removed 10.4 tons of phosphorus.

The total perch catch in the Archipelago Sea was highest at the beginning of the time series in 1998, estimated at 2,234 tons, and lowest in 2010, at 516 tons (

Figure 10). Over the entire period from 1998 to 2023, the average annual perch catch was approximately 1,150 tons, of which 69% was caught by recreational fishers. The amount of phosphorus contained in the annual total perch catch during this period averaged 12.4 tons (median: 10.0 tons; minimum: 5.6 tons; maximum: 24.1 tons).

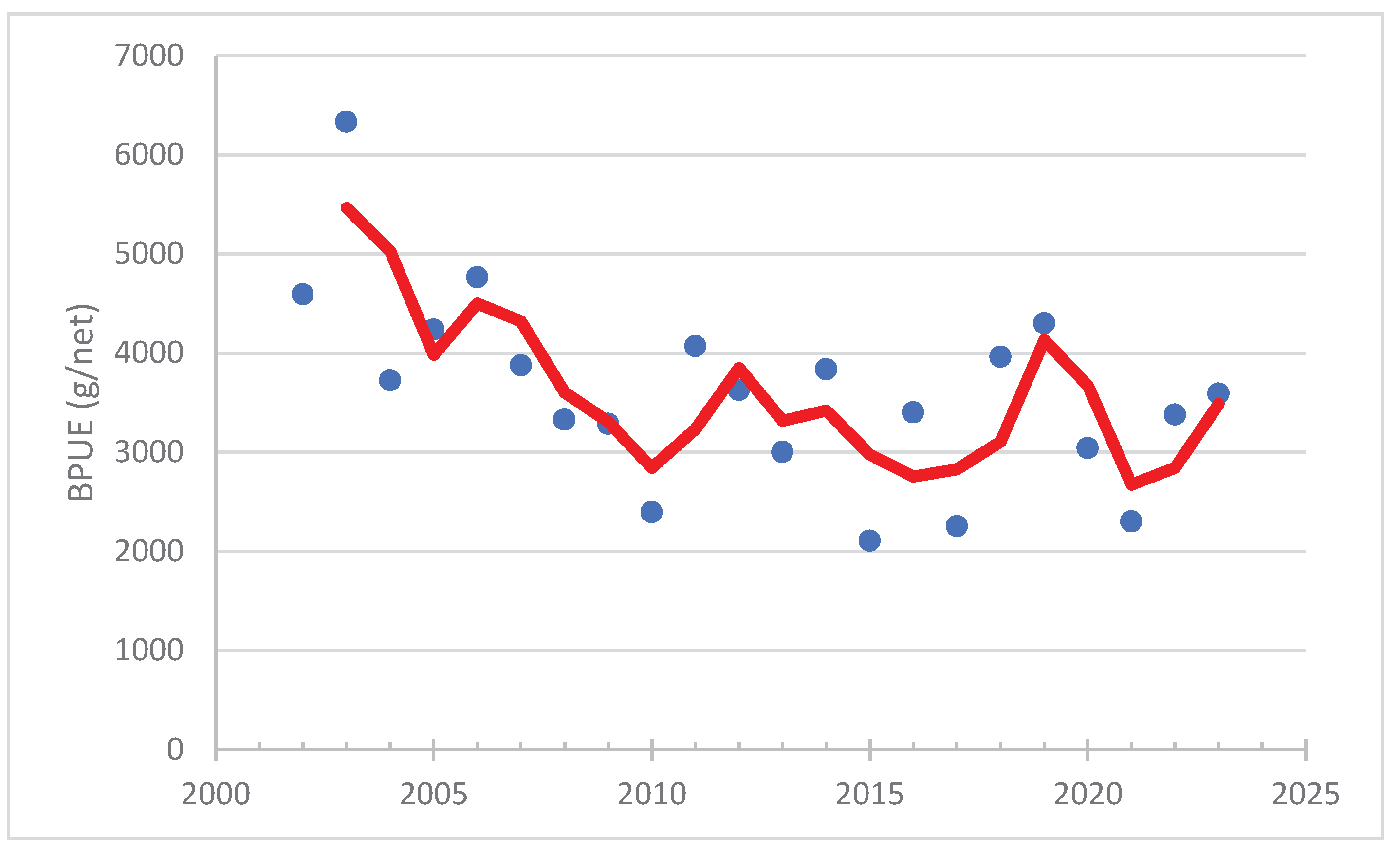

Based on the test fishing results, the perch stock was at its strongest in the early 2000s, with an average biomass per unit effort (BPUE) of 4,723 g/net; the maximum was recorded in 2003 at 6,334 g/net. During the years 2011–2023, perch biomass per unit effort (BPUE) averaged approximately 3,300 g/net, which is about 30% lower than the average observed during 2002–2005 (

Figure 11).

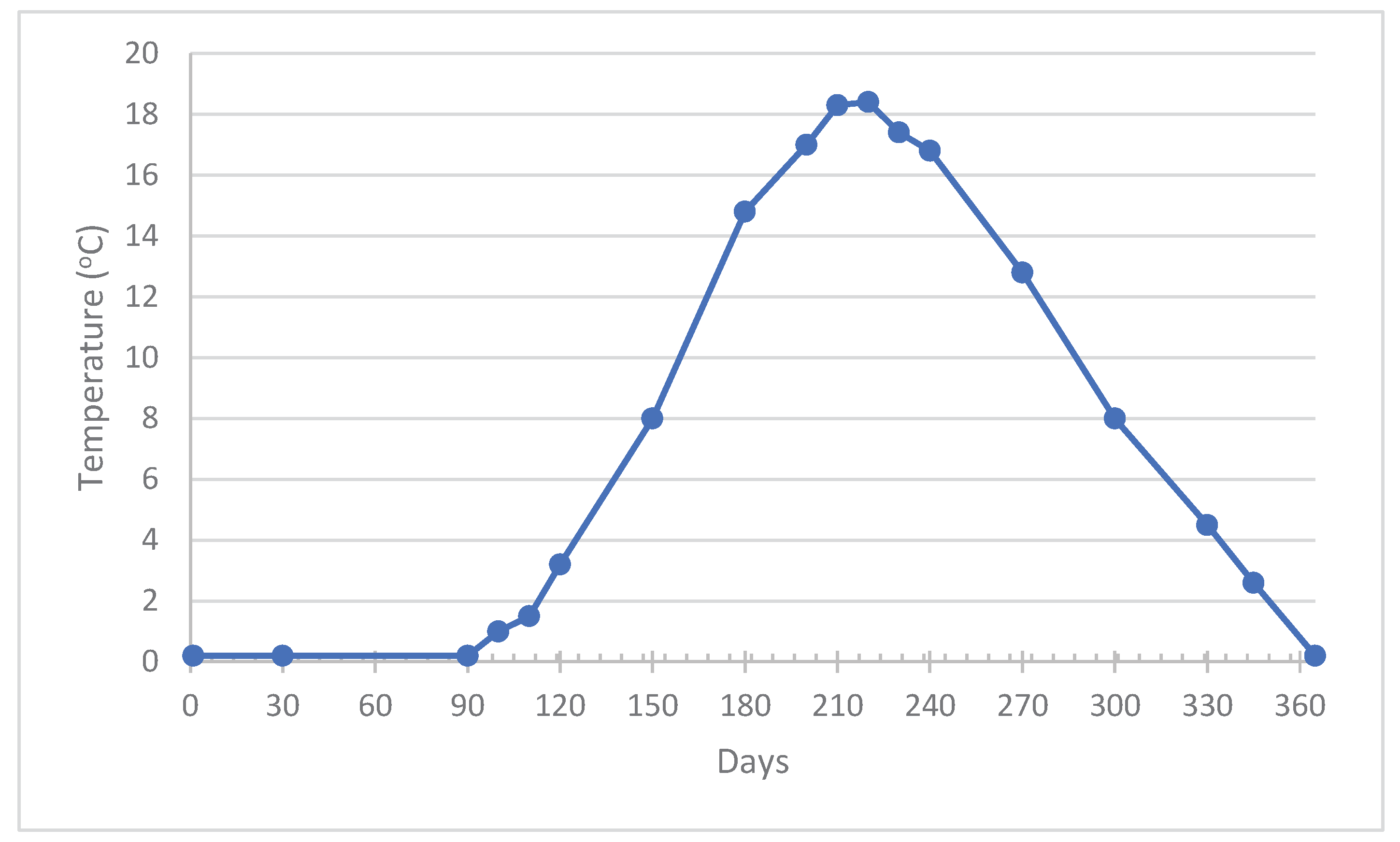

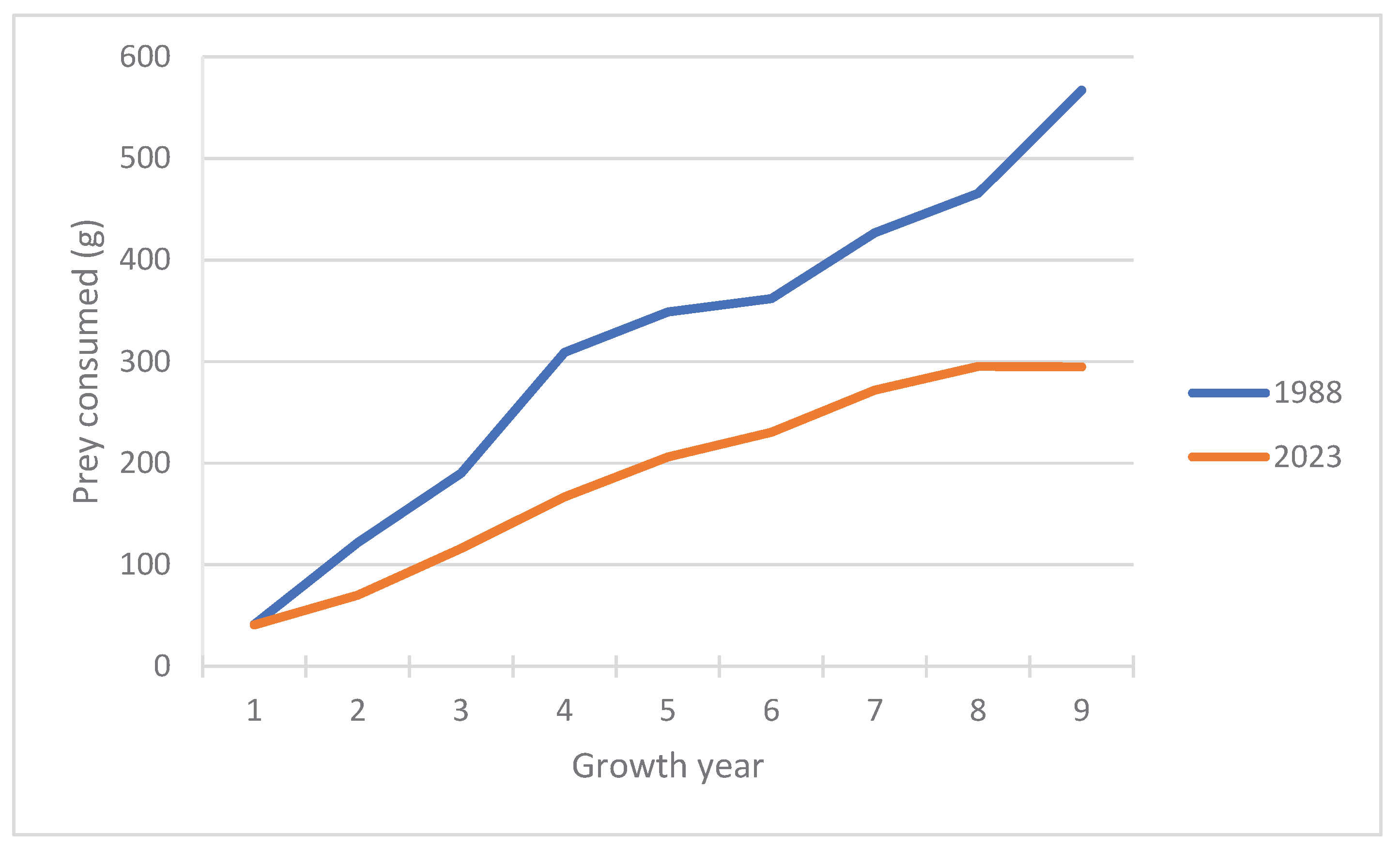

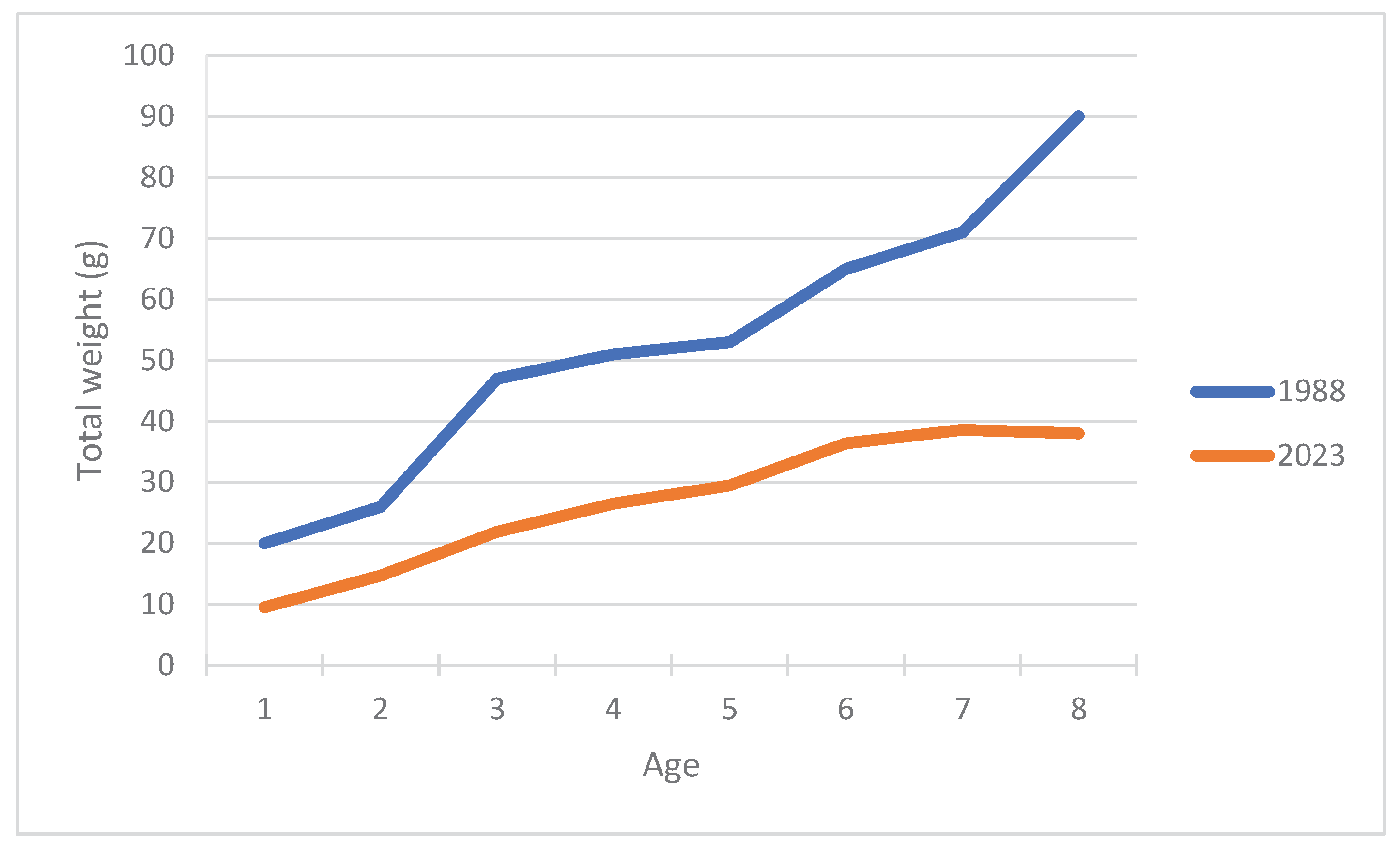

3.3. Internal Phosphorus Recycling of Herring Population

The annual food consumption of the 1+ age group and older was, on average, approximately 1.7 times higher in 1988 (characterized by strong growth and high yield) than in 2023 (poor growth, low yield; see Figure 12). The mean specific consumption rate (consumption per unit weight per day) in 1988 was approximately 12% lower—0.018 g/g/day (1.8%)—compared to 0.021 g/g/day (2.1%) in 2023. The consumption-to-predator biomass ratios were 6.6 in 1988 and 7.6 in 2023.

Figure 12.

Annual food consumption estimates (g) by herring age group calculated using a bioenergetics model for the years 1988 (strong growth, high yield) and 2023 (poor growth, low yield).

Figure 12.

Annual food consumption estimates (g) by herring age group calculated using a bioenergetics model for the years 1988 (strong growth, high yield) and 2023 (poor growth, low yield).

Based on the 1988 herring catch in the Archipelago Sea (29,507 tons), the corresponding spawning stock biomass is estimated at 117,091 tons, and the total biomass at 174,598 tons. These estimates reflect the potential maximum size of the subpopulation and are not necessarily geographically limited to the Archipelago Sea region. In 1988, the spawning stock of Baltic herring was estimated to contain approximately 527 tons of phosphorus, while the total population biomass accounted for about 786 tons.

Correspondingly, based on the 2023 catch (7,248 tons), the spawning stock biomass of Baltic herring in the Archipelago Sea is estimated at 17,465 tons, and the total biomass at 28,313 tons. Accordingly, in 2023, the spawning stock biomass was approximately 6.7 times lower, and the total biomass 6.2 times lower than in 1988. The 2023 spawning stock was estimated to contain approximately 79 tons of phosphorus, while the total biomass accounted for about 127 tons.

Table 2 presents estimates produced by bioenergetic modeling for the phosphorus load (via excretion and egestion) released into seawater by different components of the Baltic herring stock—namely, the harvested portion, the spawning stock, and the total population—in the years 1988 and 2023. The estimates have been calculated separately for the period during which the herring are present in the Archipelago Sea and for the entire year.

Table 2.

Calculations made with a bioenergetic model of phosphorus flows produced by different components of the Baltic herring stock—namely, the harvested portion (catch), the spawning stock (SSB), and the total population (TotB)—for the reference years 1988 and 2023. In the Archipelago Sea, this refers to the period when the herrings are mainly present in the area (November 1 to June 30).

Table 2.

Calculations made with a bioenergetic model of phosphorus flows produced by different components of the Baltic herring stock—namely, the harvested portion (catch), the spawning stock (SSB), and the total population (TotB)—for the reference years 1988 and 2023. In the Archipelago Sea, this refers to the period when the herrings are mainly present in the area (November 1 to June 30).

| |

Recycled P in AS

(t) |

Recycled P in AS

(mg/m2/day) |

Recycled P total

(t/v) |

| 1988 |

|

|

|

| catch |

93.4 |

0.040 |

274.1 |

| SSB |

370.6 |

0.159 |

1087.5 |

| TotB |

552.7 |

0.237 |

1621.7 |

| |

|

|

|

| 2023 |

|

|

|

| catch |

33.3 |

0.014 |

76.4 |

| SSB |

80.2 |

0.034 |

184.1 |

| TotB |

130.1 |

0.056 |

298.4 |

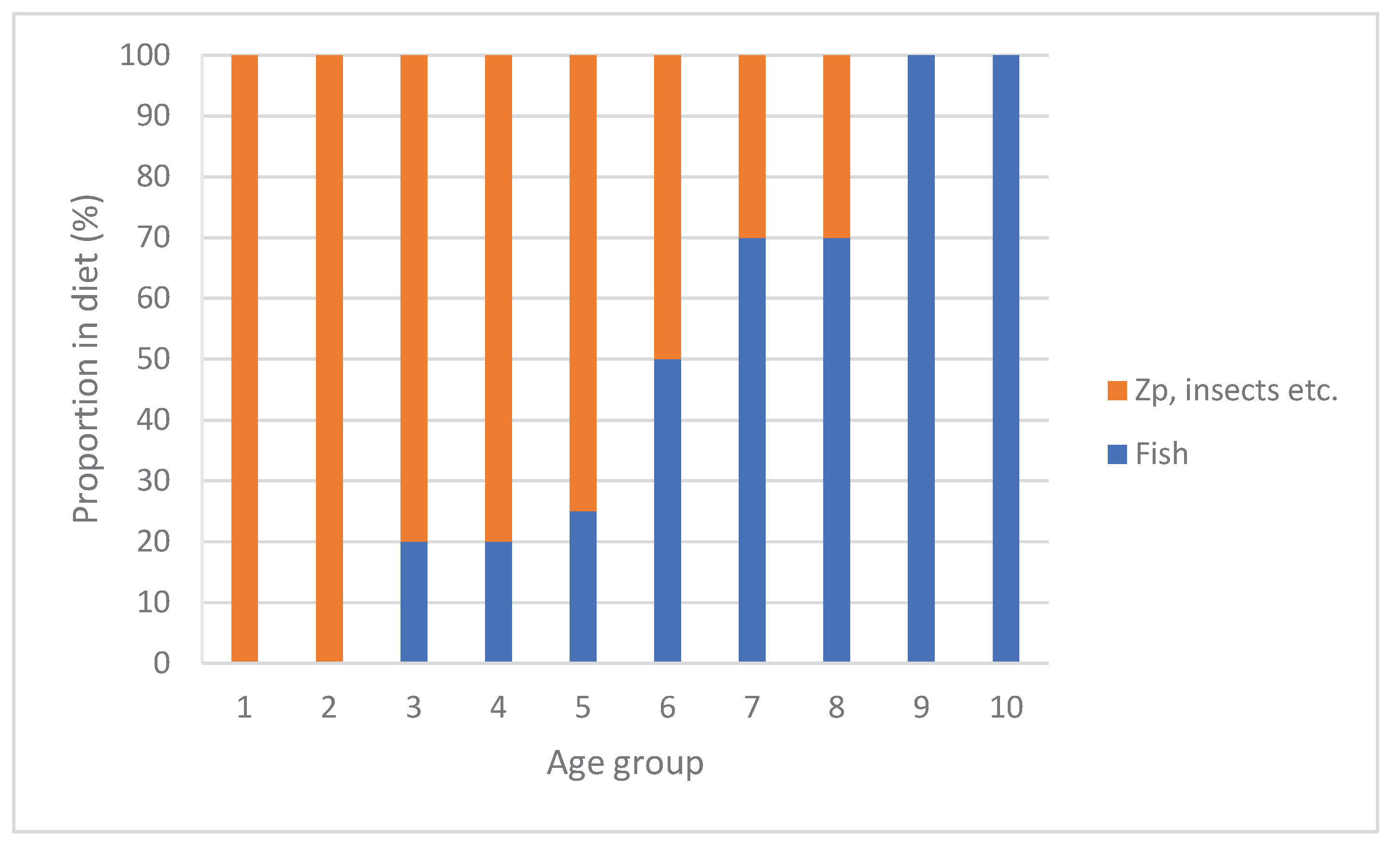

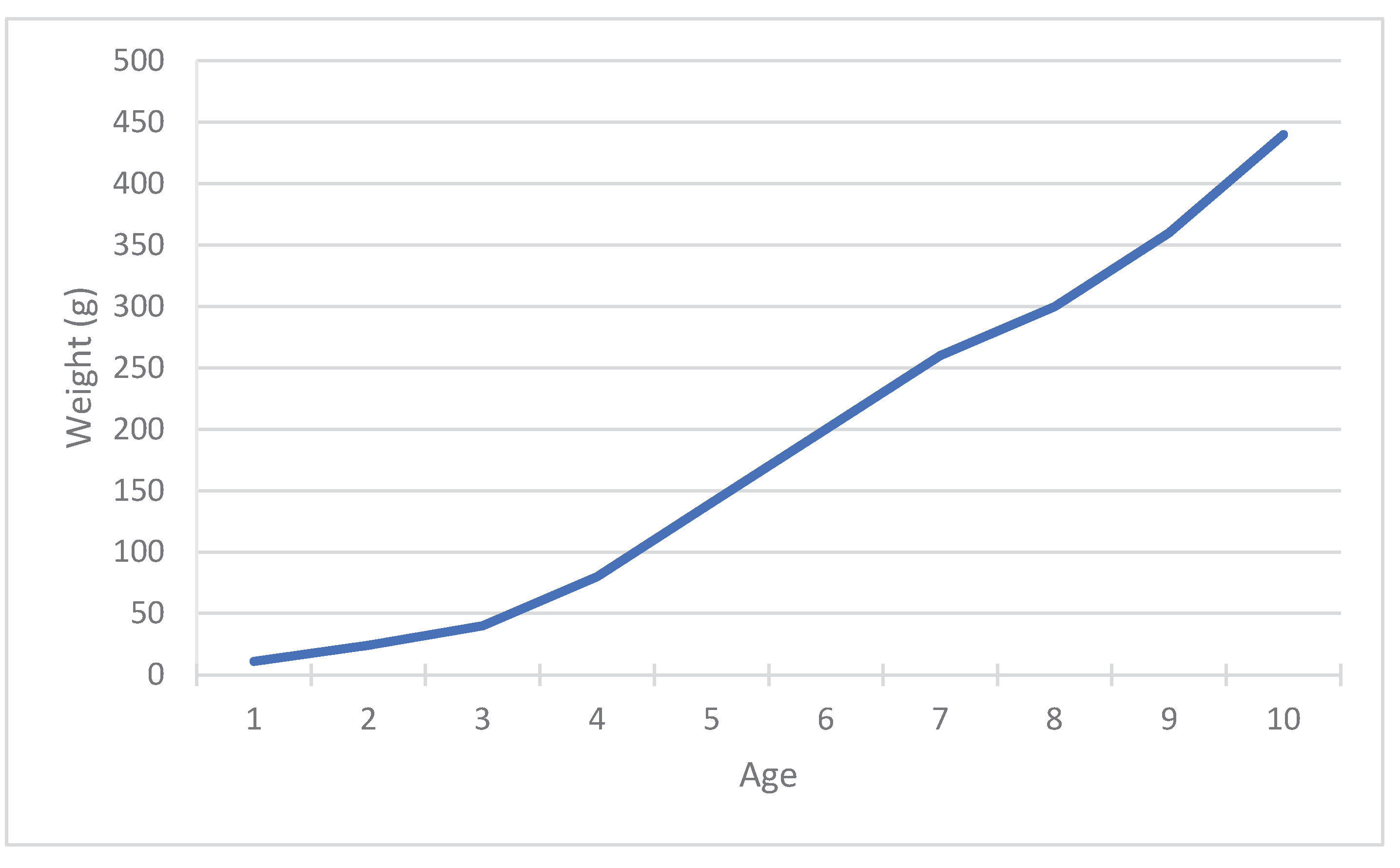

3.4. Internal Phosphorus Recycling/Regeneration of Perch Population

The annual food consumption of perch of different ages ranged from 39 g to 416 g, with an average of 219 g (Figure 12).

Figure 12.

Annual food consumption estimates (g) by perch age group calculated using a bioenergetics model for the years 1988.

Figure 12.

Annual food consumption estimates (g) by perch age group calculated using a bioenergetics model for the years 1988.

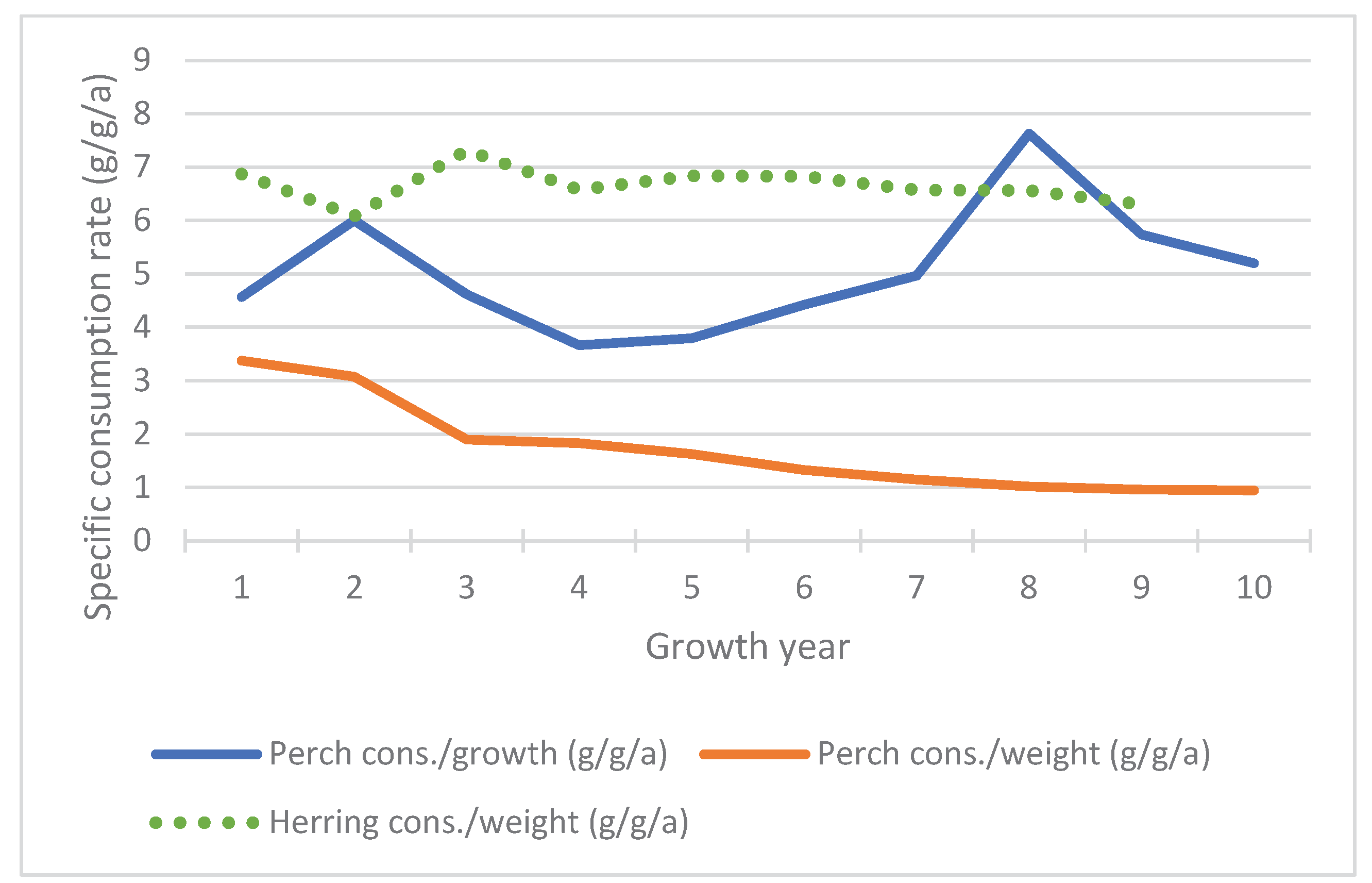

The specific consumption rate (SCR) per unit increase in weight (g/g weight/a) was about 3.2 for 1- and 2-year-old perch but decreased to approximately 1 for 6-year-olds and older (

Figure 13). The perch SCR per unit increase in growth (g/g growth/a) is much more consistent, with an average of 5.1. For Baltic herring, the SCR per unit increase in weight (g/g weight) is nearly 30% higher, at 6.7.

The calculation based on the bioenergetic model indicated that not all input data were accurate, as perch appeared to accumulate more phosphorus than it received through its diet. This was particularly evident in the younger age groups (1–4), which feed on zooplankton and crustaceans. Therefore, I adjusted the input value for the phosphorus content of perch (originally 1.08%) to an estimated 0.7% for age groups 1–6. After this adjustment, the phosphorus budget became balanced.

The phosphorus load released into seawater by the simulated perch population in 1998 (biomass 10,600 t), through excretion and egestion, was calculated to be 24.2 t/year. Approximately 56% of the phosphorus obtained from food is retained in the fish. The total perch stock contains up to 114 tons of phosphorus bound in biomass (assuming a phosphorus content of 1.08%), and the spawning stock contains 77 tons.

3.5. Generalized Phosphorus Budget of the Archipelago Sea

To support the situational analysis, I compiled a synthesis of results derived from various calculations and bioenergetic modeling approaches (

Figure 14). The summary includes an estimate of the phosphorus stock in the water phase of the Archipelago Sea for the year 1988. This estimate is, on average, approximately 18% lower than the more detailed estimate made for 2023.For the phosphorus stock in the surface layer of the sediment, only a single estimate [

19,

20] was available. The herring stock estimate representing 1988 was selected, as both the stock and catches were at their peak during that time. Similarly, the perch stock estimate for 1998 was included based on the same rationale. In 2023, the spawning stock of herring was only about 15% of the 1988 level, and the phosphorus content of the stock followed a similar proportion. The amount of phosphorus cycled by the herring stock in 2023 was 23% of the 1988 value. The total perch catch in 2023 was approximately 41% of the 1998 catch, and a similar reduction is assumed here for both the phosphorus bound in the perch stock and the amount of phosphorus recycled by it.

The phosphorus bound in the herring stock biomass corresponds to approximately 10% of the phosphorus present in the water phase during winter (

Figure 14). While the herring stock recycles phosphorus already present in the water column, part of this phosphorus is removed from circulation through excretion. Assuming a DIP:TP ratio of 0.7 in all phosphorus excreted by fish [

55], it can be estimated that during the period the herring stock resides in the Archipelago Sea, it could transfer approximately 111 tons of phosphorus from the water column to the surface layer of the sediment. This amount corresponds to roughly 10% of the phosphorus that settles to the bottom from the water column after the spring bloom. Most of the annual food consumption by herring occurs during the period when the stock is assumed to be absent from the Archipelago Sea (July 1 to November 1). In 1988, 33.6% of the herring stock’s total food consumption took place during its residence in the Archipelago Sea, whereas in 2023, the corresponding proportion was 43.2%.

The phosphorus content of the 1998 perch stock biomass was approximately 114 tons, corresponding to about 2% of the phosphorus in the water column (

Figure 14). The total phosphorus excretion and egestion by the perch stock was approximately 24 tons, of which roughly half may have been bound in fecal matter. This amount is negligible compared to, for example, the winter phosphorus stock in the water column, representing approximately 0.2%.

The amount of phosphorus removed through fish harvest should be considered in relation to both the phosphorus stock in the surface layer of the sediment and that in the water column. As fish carcasses sink to the bottom, part of the phosphorus may remain in the surface sediment layer. Organic phosphorus is converted to inorganic form (DIP) in the sediment, which can return to the water column and become available for reuse. During the years 1998–2023, the total fish catch in the Archipelago Sea removed a maximum of 136 tons of phosphorus per year. Correspondingly, during 1980–2023, the herring catch alone is estimated to have removed approximately 139 tons of phosphorus annually. If this phosphorus had remained in the Archipelago Sea, it would have increased the combined phosphorus stock of the sediment and water column (as measured in winter 1988) by approximately 0.6%.

Figure 14.

Generalized Phosphorus Budget of the Archipelago Sea. Potential reservoir of mobile phosphorus in the surface sediment layer: 19,856 tons

, shown as the blue bottom bar [

19,

20]. Phosphorus content in the water column during different seasons in the late 1980s: blue wavy line

. Amount of phosphorus (in tons) bound in the 1988 spawning stock of Baltic herring (117,091 t)

: shown above the fish symbol

. Curved arrow below the fish: phosphorus (t) recycled by the spawning stock during its residence in the Archipelago Sea. Straight downward arrow

: estimated total phosphorus (t) bound in feces. The red line indicates the period during which the Baltic herring stock is foraging beyond the Archipelago Sea. For the 1998 total perch stock (10,600 t)

, the phosphorus bound, recycled, and sedimented (t) is shown analogously to herring

.

Figure 14.

Generalized Phosphorus Budget of the Archipelago Sea. Potential reservoir of mobile phosphorus in the surface sediment layer: 19,856 tons

, shown as the blue bottom bar [

19,

20]. Phosphorus content in the water column during different seasons in the late 1980s: blue wavy line

. Amount of phosphorus (in tons) bound in the 1988 spawning stock of Baltic herring (117,091 t)

: shown above the fish symbol

. Curved arrow below the fish: phosphorus (t) recycled by the spawning stock during its residence in the Archipelago Sea. Straight downward arrow

: estimated total phosphorus (t) bound in feces. The red line indicates the period during which the Baltic herring stock is foraging beyond the Archipelago Sea. For the 1998 total perch stock (10,600 t)

, the phosphorus bound, recycled, and sedimented (t) is shown analogously to herring

.

4. Discussion

The amount of nutrients stored and cycled by fish can vary across space and time, influenced by environmental and physiological factors. In addition to natural variation, fishing can alter nutrient storage and cycling by affecting fish biomass and community structure [

56]. Based on the estimates presented earlier, fishing in the Archipelago Sea between 1980 and 2023 may have annually removed an amount of phosphorus equivalent to approximately 0.6% of the total phosphorus pool in the water column and the surface layer of the sediment. It is common to encounter comparisons in which the phosphorus content of fish catch is evaluated against only a portion of the external phosphorus load—typically riverine input alone. Using this approach, the phosphorus content of the fish catch would correspond on average approximately 24% to phosphorus load, range between 15–39% (fish catch P: mean 83,4 t, max. 136 t/year, min. 52 t/year vs. riverine input: 350 t/year [

10]). However, such comparisons are of limited relevance from a biogeochemical perspective, as the phosphorus delivered via riverine inputs is first assimilated into the Archipelago Sea ecosystem and cycled through various trophic levels before its eventual incorporation into fish biomass. The eutrophying effect of this phosphorus—namely, the stimulation of primary production—occurs prior to its transfer to higher trophic levels, and therefore, its removal through fish harvest does not mitigate the initial ecological impacts.

Rather than comparing to riverine input alone, assessments should, at a minimum, consider total external phosphorus loading, which, according to model estimates by Lignell et al. [

15], averaged 5,870 t/a in the Archipelago Sea during 2006–2014. Relative to this, the amount of phosphorus removed via fish harvest would represent only about 1.4% of the total load. Even in this comparison, it is important to account for the earlier point regarding internal phosphorus cycling within the ecosystem, as well as the fact that a substantial proportion of the phosphorus removed with the fish originates from outside the Archipelago Sea. The Baltic herring stock associated with the Archipelago Sea spends most of the summer feeding in the Bothnian Sea or the main basin of the Baltic Sea.

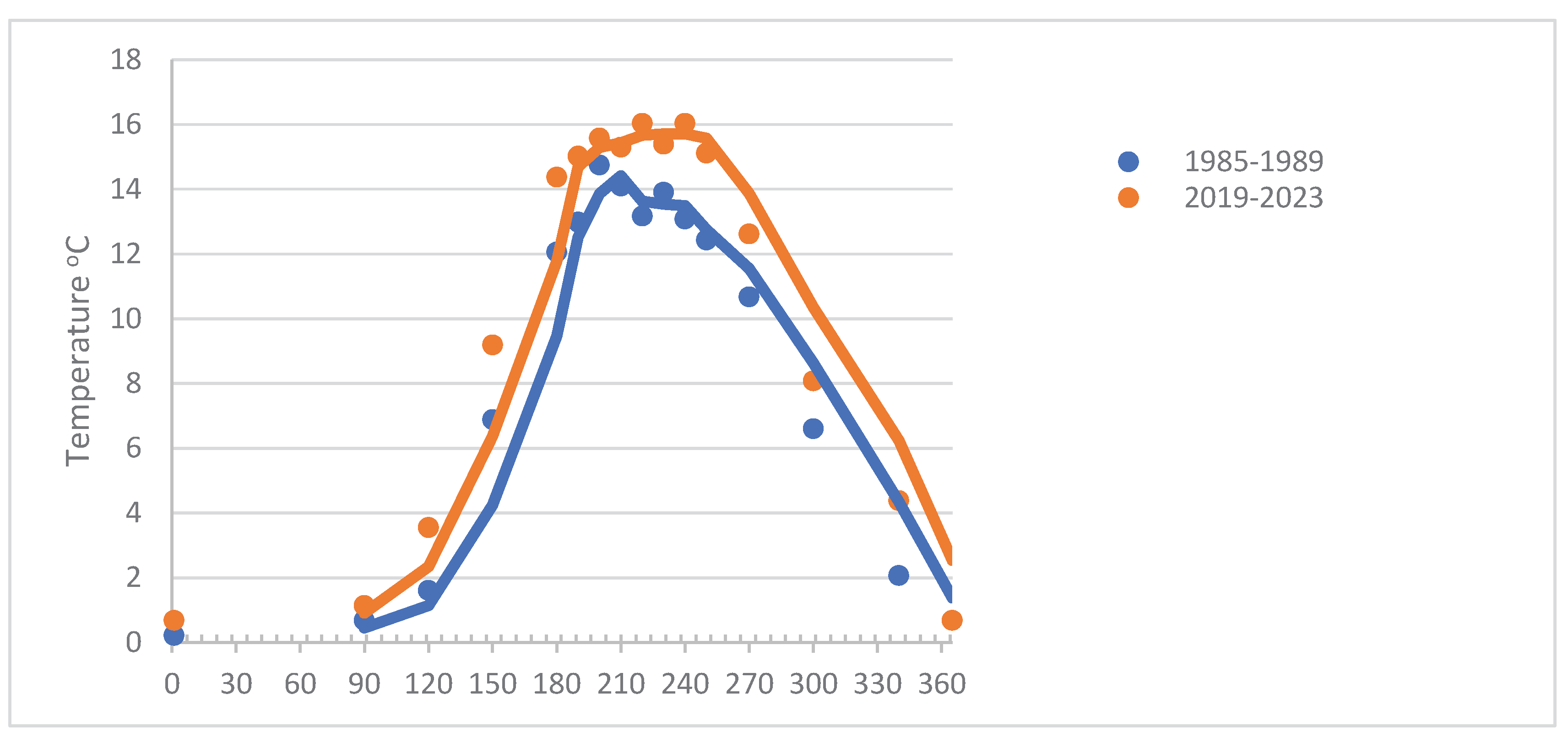

Between 1988 and 2023, the estimated phosphorus content in the spawning stock of Baltic herring in the Archipelago Sea decreased by approximately 85%, and by around 84% in the total biomass. This substantial decline reflects a significant reduction in herring biomass in the Archipelago Sea, which may have implications for phosphorus cycling, food web dynamics, and nutrient retention within the marine ecosystem. According to Rajasilta et al. [

57] the total lipid resources of spawning females have decreased by 40–50% during 1988-2019, and the mean length of the spawning population decreased from 21 to 16 cm due to the reduction of their growth rate. The decline in herring body condition is also clear in

Figure 2. According to Casini et al. [

58] the main predictor of herring and sprat condition is the total abundance of clupeids. They found the strong correlation between clupeid abundance and total zooplankton biomass which pointed to food competition and to top-down control by herring and sprat on common food resources.

Baltic sprat populations began to increase, likely by the 1990s at the latest, following the collapse of cod stocks due to poor recruitment and high fishing pressure. Sprat was the principal prey for cod in the Baltic Sea [

59]. Herring and sprat, although showing some differences in feeding preferences, have a strong diet overlap during a large part of their ontogeny. The sprat spawning stock peaked in 1997. Although the stock has declined since then, it has remained significantly more abundant than in the 1980s. In the Archipelago Sea, sprat catches have remained low, averaging approximately 40 tons per year between 1980 and 2023. In the late 1990s, when the stock was at its strongest, catches averaged around 200 tons per year. The majority of sprat are found in the Baltic Sea main basin and the Bothnian Sea—areas where Baltic herring from the Archipelago Sea also migrate to feed. In their 2011 publication, Casini et al. [

59] provided evidence that temporal fluctuations in both sprat and herring condition in all areas of the Baltic Proper can be linked to drastic variations in sprat density.

The summer build-up of fish biomass in the Archipelago Sea sequesters quantities of P, which is much greater than the amount removed annually via harvest. In 1988, the total Baltic herring stock in the Archipelago Sea was estimated to contain 786 tons of phosphorus, whereas by 2023, this amount had decreased to just 127 tons. However, this phosphorus pool can be considered a dynamic and partly transient component of the overall budget. According to bioenergetic model estimates of food consumption, in 1988 Baltic herring obtained approximately 66% of their annual food intake from areas outside the Archipelago Sea, and in 2023 about 57%. These figures may still be underestimates, as only indicative assessments exist regarding herring movements between the Archipelago Sea and their feeding grounds. Regardless, most of the phosphorus stored in Baltic herring originates from areas outside the Archipelago Sea. Baltic herring thus function as vectors of phosphorus transport, carrying a portion of the phosphorus pool that is partly removed through harvest and partly deposited into the Archipelago Sea during the spawning period.

The amount of phosphorus retained in the inner archipelago spawning areas via herring eggs can be estimated by assuming, for example, that half of the 1988 spawning stock biomass (117,091 tons) consisted of females (58,546 tons). Based on studies of Baltic herring eggs [

60], the mass of the released eggs may amount to approximately 10% of the spawning stock biomass. If it is further assumed that 90% of the deposited eggs are washed off from the substrate, this would result in an estimated 5,270 tons of non-viable egg mass remaining in the coastal zone. Assuming that the phosphorus content of herring eggs is like that of adult herring (0.45%), the estimated amount of phosphorus remaining in the coastal zone would be 23.7 tons. In 2023, the size of the Baltic herring spawning stock was estimated to be only about 15% of its 1988 level. The number of eggs deposited in the Archipelago Sea declined in proportion to the reduction in spawning stock size. According to studies by Puttonen [

19], the phosphorus stock in the surface sediment of the southwestern inner archipelago zone (679 km²) might be approximately 2,377 tons. The phosphorus input from herring eggs in 1988 would represent about 1% of this amount, but by 2023, only 1.5‰.

Fish contribute to phosphorus recycling in aquatic systems by excreting excess phosphorus, which can then be utilized by algae or other organisms. Nutrient recycling by fishes will tend to alleviate P limitation of phytoplankton growth, but the importance of this effect will be directly proportional to the magnitude of nutrient regeneration rates from fishes relative to other sources available to phytoplankton [

56]. The total herring stock in the Archipelago Sea was estimated to be capable of recycling phosphorus at a maximum rate of 0.237 mg/m²/day (

Table 2). This nutrient recycling is likely to be most significant in early summer, when water temperatures are rising, primary production is beginning, and the majority of herring are still present in the Archipelago Sea. The estimated size of the Baltic herring stock at that time 1988 was 117,598 tons, or 18.4 g/m², and the spawning stock was 117,019 tons, or 12.3 g/m². These estimates are broadly consistent with findings from other studies, despite potentially appearing elevated. For instance, 18.4 g/m² corresponds to 184 kg/ha, a value that is already considerable even in lacustrine systems. According to Thurow [

61], the total fish biomass in the Baltic Sea increased from about 5 g/m² in 1903 to 17–23 g/m² during the period 1970–1990. Axenrot and Hansson [

62] estimated stock spawning biomass (SSB) in ICES SD 27 during the years 1988–1989 to an average of 173,150 tons, or about 10 g/m².

Since no researched data is available, it is assumed here that approximately 30% of the estimated recycled phosphorus by herrings would be deposited to the seabed via fecal matter, at least temporarily (

Figure 14). Consequently, the maximum amount of dissolved inorganic phosphorus (DIP) recycled by herring and retained in the water column would be approximately 0.17 mg/m²/day. Dissolved P contains all urinary P and a portion of fecal P that is soluble and therefore leached from voided feces. DIP is bioavailable and can immediately fuel primary production. Egested nutrients are integrated into fecal pellets that sink out of the surface layer and are recycled at greater depths than if bound to smaller particles [

63,

64], especially fish fecal pellets that can sink faster and deeper than marine snow and phytodetritus [

56].

There is data available on the biomass of phytoplankton (see earlier VESLA, phytoplankton register) and zooplankton [

65] in the Archipelago Sea, but not on the rates at which they recycle nutrients, or similar processes. The phosphorus contained in plankton is essentially included in the phosphorus pool of the water column, but based on biomass data and concentration estimates, it can be separated from it to some extent. Based on data from the Seili monitoring station, the average phytoplankton biomass during the period April 1 to October 31 between 2001 and 2024 has been 1.58 mg L⁻¹ (wet weight), with a median value of 0.75 mg L⁻¹. Since the volume of the surface layer (0–10 m) of the Archipelago Sea has previously been estimated at 80.2 km³ [

10], the mean phytoplankton biomass can be calculated as approximately 127,037 tons wet weight. If phytoplankton contains 0.08% phosphorus by wet weight [

6], the average size of the instantaneous phosphorus pool of phytoplankton can be estimated at approximately 102 tons. This corresponds to approximately 1.8% of the estimated average total phosphorus pool in the entire water volume of the Archipelago Sea during the 2000s. According to Rousi et al. (figure 2; [65)], the average zooplankton biomass was approximately 1 g/m³, wet weight during the years 1980–1985 but had declined to around 0.2 g/m³ in the 2000s. The volume of the surface layer (0–20 m) is 131.5 km³, so in the 1980s the biomass of zooplankton in the Archipelago Sea averaged 131,500 tons (wet weight), and in the 2000s it was only 26,300 tons. Correspondingly, the amount of phosphorus contained in the zooplankton was 197 tons and 40 tons. In the 1980s, this accounted for approximately 4.4% of the estimated phosphorus pool in the water phase, and in the 2000s, 0.7%.

According to Griffiths [

6], in lake ecosystems, phosphorus turnover rates mediated by zooplankton (mg/m²/day) are estimated to be approximately eight times higher than those mediated by fish, while turnover via phytoplankton may be up to 34 times greater. But fish could be more important as nutrient stores than plankton. In the Archipelago Sea dataset, the phosphorus bound in Baltic herring reached a maximum of 82.7 mg/m² in 1988 and declined to 13.4 mg/m² by 2023. Corresponding values for zooplankton were 20.7 mg/m² in the 1980s and 4.2 mg/m² in the 2020s. The phosphorus content of phytoplankton has remained around 10.7 mg/m² during the 2000s. In the late 1990s, the maximum amount of phosphorus bound in perch biomass was approximately 12 mg/m², whereas today it is estimated to be about 30% lower (

Figure 11), i.e., approximately 8 mg/m². Notably, there has been a significant shift in the relative proportions of phosphorus pools. In the 1980s and 1990s, the ratio of phosphorus bound in plankton to that in fish was approximately 1:3. However, in the 2020s, this ratio has shifted to about 1:1.4, indicating a notable change in the distribution of phosphorus between trophic levels.

A notable aspect of the ecological changes observed in the Archipelago Sea is the marked decline in zooplankton biomass, which appears to have commenced in the early 1990s and has persisted to the present day: between the early 1980s and 2019, zooplankton biomass has decreased by approximately 80% [

65]. Concurrently, the estimated instantaneous total biomass of the herring stock has declined by as much as 84% from 1988 to 2023. However, it is important to note that herring in the Archipelago Sea primarily forage elsewhere, namely in the Baltic Proper or the Bothnian Sea, where it competes for the same food resources as the sprat [

58]. Rousi et al. [

65] concluded that a considerable biomass and functional biodiversity loss of the common mesozooplankton is likely driven by climatic factors. For example, Steinkopf et al. [

66] have emphasized the role of eutrophication as a key driver behind the changes observed in the Baltic Sea food webs. Eutrophication and increased temperatures can lead to massive filamentous, N2-fixing cyanobacterial (FNC) blooms in coastal ecosystems with largely unresolved consequences for the mass and energy supply in food webs. Mesozooplankton adapt to not top-down controlled FNC blooms by switching diets from phytoplankton to microzooplankton, resulting in a directly quantifiable increase in its trophic position. If, in this process—known as trophic lengthening—mesozooplankton is transferred to higher trophic levels within the food web, the resulting energy loss could lead to substantial declines in fish biomass.