Submitted:

06 June 2025

Posted:

09 June 2025

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

1. Practical and Technical Considerations for Pipeline Execution

2. Pipelines

2.1. Descriptive Pipeline Overview

2.1.1. Short-Read Centered Pipelines

2.1.1.1. Anvi’o [45]

2.1.1.2. DATMA [42]

2.1.1.3. EasyMetagenome [46]

| Pipeline/Platform | Short reads | Long reads* | Hybrid Assembly | Multi-sample | Assembly/Binning strategies | Bin refinement | Computational resources** | Interface*** | Workflow manager | Software execution | Special features | |

| 1 | aDNA [44] | Yes | No | No | No | Single | Yes | Local, HPC | CLI | None | Local | Designed for ancient DNA |

| 2 | Anvi’o [45] | Yes | No | No | Yes | Single/Co | Yes | Local | CLI/GUI | None | Conda | Eukaryotic/Viral MAGs |

| 3 | Aviary [40] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Single | Yes | Local, HPC, CC | CLI | Snakemake | Conda | Genotype recovery |

| 4 | BV-BRC [25] | Yes | No | No | Yes | Single | No | External | GUI | None | None | Taxonomic profiling, Viral MAGs |

| 5 | DATMA [42] | Yes | No | No | No | Single | No | Local/HPC | CLI | COMP Superscalar | Local | Inverted binning and assembly |

| 6 | EasyMetagenome [46] | Yes | No | No | Yes | Single/Co | Yes | Local, HPC | CLI | None | Conda | Taxonomic profiling |

| 7 | EasyNanoMeta [47] | No | Yes (ONT) | Yes | Yes | Single | No | Local, HPC | CLI | None | Conda, Singularity | Taxonomic profiling |

| 8 | Eukfinder [37] | Yes | Yes | No | No | Single | No | Local, HPC | CLI | None | Conda | Eukaryotic MAGs |

| 9 | Galaxy [48] | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Single | Yes | External | GUI | None | None | Taxonomic profiling |

| 10 | GEN-ERA [49] | Yes | Yes (ONT) | No | Yes | Single | No | Local, HPC, CC | CLI | Nextflow | Singularity | Metabolic modeling |

| 11 | HiFi-MAG [50] | No | Yes (PacBio) | No | Yes | Single | Yes | Local, HPC, CC | CLI | Snakemake | Conda | |

| 12 | IDseq [51] | Yes | Yes (ONT) | No | No | Single | No | External | GUI | None | None | Viral MAGs |

| 13 | KBase [22] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Single/Co | Yes | External | GUI | None | None | Taxonomic profiling, metabolic modeling |

| 14 | MAGNETO [52] | Yes | No | No | Yes | Single/Co | No | Local, HPC, CC | CLI | Snakemake | Conda | Taxonomic profiling |

| 15 | MetaGEM [38] | Yes | No | No | Yes | Single | Yes | Local, HPC, CC | CLI | Snakemake | Conda | Eukaryotic MAGs, Metabolic modeling |

| 16 | MetaGenePipe [53] | Yes | No | No | Yes | Single/Co | No | Local, HPC, CC | CLI | WDL | Singularity | |

| 17 | Metagenome-Atlas [54] | Yes | No | No | Yes | Single | Yes | Local, HPC, CC | CLI | Snakemake | Conda | |

| 18 | Metagenomics-Toolkit [39] | Yes | Yes (ONT) | No | Yes | Single | Yes | Local, HPC, CC | CLI | Nextflow | Docker |

Plasmid assembly, Metabolic modeling, Controlled resource allocation |

| 19 | Metaphor [55] | Yes | No | No | Yes | Single/Co | Yes | Local, HPC, CC | CLI | Snakemake | Conda | |

| 20 | metaWGS [56] | Yes | Yes (PacBio) | No | Yes | Single/Co | Yes | Local, HPC, CC | CLI | Nextflow | Singularity | |

| 21 | MetaWRAP [57] | Yes | No | No | Yes | Single/Co | Yes | Local/HPC | CLI | None | Conda, Docker | Taxonomic profiling |

| 22 | MGnify [23] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Single/co | No | External | GUI | None | None | Taxonomic profiling |

| 23 | MOSHPIT [58] | Yes | No | No | Yes | Single | Yes | Local, HPC | CLI | None | Conda | Taxonomic profiling |

| 24 | MUFFIN [41] | No | Yes (ONT) | Yes | Yes | Single | Yes | Local, HPC, CC | CLI | Nextflow |

Conda, Docker, Singularity |

RNA-seq transcriptome analysis |

| 25 | NanoPhase [59] | No | Yes (ONT) | Yes | No | Single | Yes | Local, HPC | CLI | None | Conda | |

| 26 | nf-core/mag [60] | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Single/Co | Yes | Local, HPC, CC | CLI | Nextflow |

Conda, Docker, Singularity, Other |

Taxonomic profiling |

| 27 |

ngs-preprocess- MpGAp-Bacannot [61] |

Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Single | No | Local, HPC, CC | CLI | Nextflow | Conda, Docker, Singularity | |

| 28 | SnakeMAGs [62] | Yes | No | No | Yes | Single | No | Local, HPC, CC | CLI | Snakemake | Conda | |

| 29 | SqueezeMeta [63] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Single/co | Yes | Local, HPC | CLI | None | Conda | |

| 30 | Sunbeam [64] | Yes | No | No | Yes | Single | No | Local, HPC | CLI | Snakemake | Conda, Docker | Taxonomic profiling |

| 31 | VEBA [36] | Yes | No | No | Yes | Pseudo-coassembly | No | Local, HPC | CLI | None | Conda | Eukaryotic/Viral MAGs |

| *Long reads: ONT: Oxford Nanopore Technology. PacBio: Pacific Biosciences. **Computational resources: HPC: High Performance Cluster. CC: Cloud Computing. ***Interface: CLI: Command Line Interface. GUI: Graphical User Interface. | ||||||||||||

2.1.1.4. MAGNETO [52]

2.1.1.5. metaGEM [38]

2.1.1.6. MetaGenePipe [53]

2.1.1.7. Metagenome-Atlas [54]

2.1.1.8. Metagenomics-Toolkit [39]

2.1.1.9. Metaphor [55]

2.1.1.10. MetaWRAP [57]

2.1.1.11. MOSHPIT [58]

2.1.1.12. SnakeMAGs [62]

2.1.1.13. Sunbeam [64]

2.1.1.14. VEBA [36]

2.1.2. Long-Read Focused Pipelines

2.1.2.1. EasyNanoMeta [128]

2.1.2.2. Hi-Fi-MAG-Pipeline [50]

2.1.2.3. metaWGS [136]

2.1.2.4. NanoPhase [59]

2.1.3. Hybrid Pipelines

2.1.3.1. Aviary [40]

2.1.3.2. GEN-ERA [49]

2.1.3.3. MUFFIN [41]

2.1.3.4. nf-core/mag [60]

2.1.3.5. ngs-preprocess-MpGAp-Bacannot [61]

2.1.3.6. SqueezeMeta [63]

2.1.4. Web-Based Pipelines with External Computational Resource Support

2.1.4.1. BV-BRC [25]

2.1.4.2. Galaxy [48]

2.1.4.3. IDseq [51]

2.1.4.4. KBase [22]

2.1.4.5. MGnify [23]

2.1.5. Special Pipelines

2.1.5.1. Pipeline for ancient DNA [171]

2.1.5.2. Eukfinder [37]

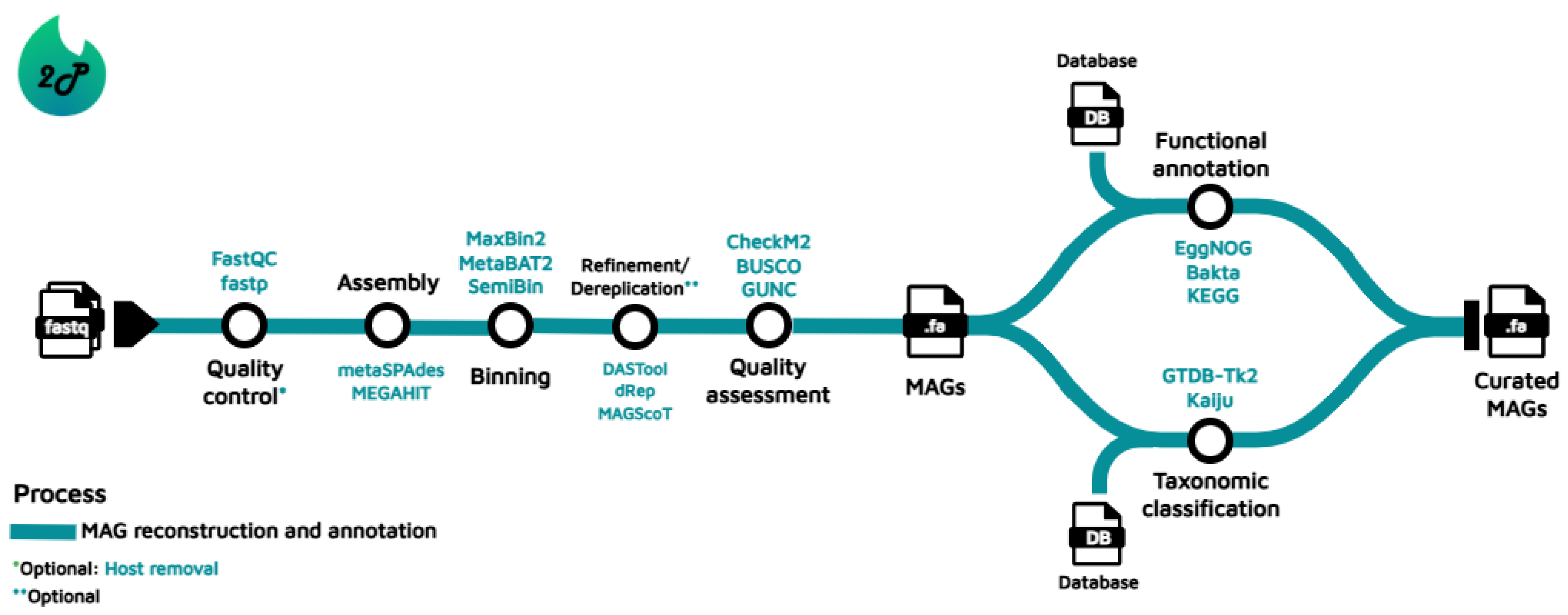

3. 2Pipe: It Starts with a Question

Conclusions

Availability of data and materials

Acknowledgments

References

- Bowers, R.M.; et al. Minimum information about a single amplified genome (MISAG) and a metagenome-assembled genome (MIMAG) of bacteria and archaea. Nat. Biotechnol. 2017, 35, 725–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Setubal, J.C. Metagenome-assembled genomes: concepts, analogies, and challenges. Biophys. Rev. 2021, 13, 905–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, N.; et al. Genome-resolved metagenomics: a game changer for microbiome medicine. Exp. Mol. Med. 2024, 56, 1501–1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lemos, L.N.; Mendes, L.W.; Baldrian, P.; Pylro, V.S. Genome-Resolved Metagenomics Is Essential for Unlocking the Microbial Black Box of the Soil. Trends Microbiol. 2021, 29, 279–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, A.E.; et al. Design considerations for workflow management systems use in production genomics research and the clinic. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goussarov, G.; et al. Benchmarking short-, long- and hybrid-read assemblers for metagenome sequencing of complex microbial communities. Microbiology 2024, 170, 001469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.-M.; et al. Comparative analysis of 7 short-read sequencing platforms using the Korean Reference Genome: MGI and Illumina sequencing benchmark for whole-genome sequencing. GigaScience, 2021; 10, giab014. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, C.; et al. A review of computational tools for generating metagenome-assembled genomes from metagenomic sequencing data. Computational and Structural Biotechnology Journal, 2021; 19, 6301–6314 . [Google Scholar]

- Vosloo, S.; et al. Evaluating de Novo Assembly and Binning Strategies for Time Series Drinking Water Metagenomes. Microbiol. Spectr. 2021; 9. [Google Scholar]

- Han, H.; Wang, Z.; Zhu, S. Benchmarking metagenomic binning tools on real datasets across sequencing platforms and binning modes. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 2865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynn, H.M.; Gordon, J.I. Sequential co-assembly reduces computational resources and errors in metagenome-assembled genomes. Cell Rep. Methods, 2025; 5. [Google Scholar]

- Christoph, M.; Hlemann, R.; Wacker, E.M.; Ellinghaus, D.; Franke, A. MAGScoT: a fast, lightweight and accurate bin-refinement tool. Bioinformatics 2022, 38, 5430–5433. [Google Scholar]

- Olm, M.R.; Brown, C.T.; Brooks, B.; Banfield, J.F. dRep: a tool for fast and accurate genomic comparisons that enables improved genome recovery from metagenomes through de-replication. ISME J. 2017, 11, 2864–2868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sieber, C.M.K.; et al. Recovery of genomes from metagenomes via a dereplication, aggregation and scoring strategy. Nat. Microbiol. 2018, 3, 836–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, J.T.; Denef, V.J. To Dereplicate or Not To Dereplicate? mSphere, 2020; 5. [Google Scholar]

- Goldfarb, T.; et al. NCBI RefSeq: reference sequence standards through 25 years of curation and annotation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2025, 53, D243–D257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaumeil, P.-A.; Mussig, A.J.; Hugenholtz, P.; Parks, D.H. GTDB-Tk v2: memory friendly classification with the genome taxonomy database. Bioinformatics 2022, 38, 5315–5316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The UniProt Consortium. UniProt: the Universal Protein Knowledgebase in 2025. Nucleic Acids Res. 2025, 53, D609–D617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanehisa, M.; Sato, Y.; Kawashima, M.; Furumichi, M.; Tanabe, M. KEGG as a reference resource for gene and protein annotation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016, 44, D457–D462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huerta-Cepas, J.; et al. eggNOG 5.0: a hierarchical, functionally and phylogenetically annotated orthology resource based on 5090 organisms and 2502 viruses. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019; 47, D309–D314 . [Google Scholar]

- Shaffer, M.; et al. DRAM for distilling microbial metabolism to automate the curation of microbiome function. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020, 48, 8883–8900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arkin, A.P.; et al. KBase: The United States Department of Energy Systems Biology Knowledgebase. Nat. Biotechnol. 2018, 36, 566–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, L.; et al. MGnify: the microbiome sequence data analysis resource in 2023. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, 51, D753–D759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sloggett, C.; Goonasekera, N.; Afgan, E. BioBlend: automating pipeline analyses within Galaxy and CloudMan. Bioinformatics 2013, 29, 1685–1686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, R.D.; et al. Introducing the Bacterial and Viral Bioinformatics Resource Center (BV-BRC): a resource combining PATRIC, IRD and ViPR. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, 51, D678–D689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achudhan, A.B.; Kannan, P.; Gupta, A.; Saleena, L.M. A Review of Web-Based Metagenomics Platforms for Analysing Next-Generation Sequence Data. Biochem. Genet. 2024, 62, 621–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navgire, G.S.; et al. Analysis and Interpretation of metagenomics data: an approach. Biol. Proced. Online 2022, 24, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köster, J.; et al. Sustainable data analysis with Snakemake. F1000Research 2021, 10, 33. [Google Scholar]

- Tommaso, P.D.; et al. Nextflow enables reproducible computational workflows. Nat. Biotechnol. 2017, 35, 316–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ewels, P.A.; et al. The nf-core framework for community-curated bioinformatics pipelines. Nat. Biotechnol. 2020, 38, 276–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voss, K.; Auwera, G.V.d.; Gentry, J. Full-stack genomics pipelining with GATK4 + WDL + Cromwell. F1000Research, 2017; 6. [Google Scholar]

- Wratten, L.; Wilm, A.; Göke, J. Reproducible, scalable, and shareable analysis pipelines with bioinformatics workflow managers. Nat. Methods 2021, 18, 1161–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roach, M.J.; et al. Ten simple rules and a template for creating workflows-as-applications. PLOS Comput. Biol. 2022, 18, e1010705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reiter, T.; et al. Streamlining data-intensive biology with workflow systems. GigaScience, 2021; 10. [Google Scholar]

- Kadri, S.; Sboner, A.; Sigaras, A.; Roy, S. Containers in Bioinformatics: Applications, Practical Considerations, and Best Practices in Molecular Pathology. J. Mol. Diagn. 2022, 24, 442–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinoza, J.L.; Dupont, C.L. VEBA: a modular end-to-end suite for in silico recovery, clustering, and analysis of prokaryotic, microeukaryotic, and viral genomes from metagenomes. BMC Bioinformatics 2022, 23, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.; et al. Eukfinder: a pipeline to retrieve microbial eukaryote genome sequences from metagenomic data. mBio 2025, 16, e00699–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zorrilla, F.; Buric, F.; Patil, K.R.; Zelezniak, A. metaGEM: reconstruction of genome scale metabolic models directly from metagenomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, e126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belmann, P.; et al. Metagenomics-Toolkit: The Flexible and Efficient Cloud-Based Metagenomics Workflow featuring Machine Learning-Enabled Resource Allocation. ( 2024.

- Newell, R.J.P.; et al. Aviary: Hybrid assembly and genome recovery from metagenomes. ( 2025.

- Damme, R. van et al. Metagenomics workflow for hybrid assembly, differential coverage binning, metatranscriptomics and pathway analysis (MUFFIN). PLOS Comput. Biol. 2021, 17, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Benavides, A.; Sanchez, F.; Alzate, J.F.; Cabarcas, F. DATMA: Distributed Automatic Metagenomic Assembly and annotation framework. PeerJ, 2020; 8. [Google Scholar]

- Wajid, B.; et al. Music of metagenomics—a review of its applications, analysis pipeline, and associated tools. Funct. Integr. Genomics 2022, 22, 3–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Standeven, F.J.; Dahlquist-Axe, G.; Speller, C.F.; Meehan, C.J.; Tedder, A. An efficient pipeline for creating metagenomic-assembled genomes from ancient oral microbiomes. ( 2024.

- Eren, A.M.; et al. Community-led, integrated, reproducible multi-omics with anvi’o. Nat. Microbiol. 2020, 6, 3–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, D.; et al. EasyMetagenome: A user-friendly and flexible pipeline for shotgun metagenomic analysis in microbiome research. iMeta 2025, 4, e70001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, K.; et al. Benchmarking of analysis tools and pipeline development for nanopore long-read metagenomics. Sci. Bull. 2025, 70, 1591–1595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Galaxy, Community; et al. The Galaxy platform for accessible, reproducible and collaborative biomedical analyses: 2022 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022, 50, W345–W351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornet, L.; et al. The GEN-ERA toolbox: unified and reproducible workflows for research in microbial genomics. GigaScience 2022, 12, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacific Biosciences. HiFi-MAG-Pipeline. (2025).

- Kalantar, K.L.; et al. IDseq—An open source cloud-based pipeline and analysis service for metagenomic pathogen detection and monitoring. GigaScience 2020, 9, giaa111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Churcheward, B.; Millet, M.; Bihouée, A.; Fertin, G.; Chaffron, S. MAGNETO: An Automated Workflow for Genome-Resolved Metagenomics. mSystems, 2022; 7. [Google Scholar]

- Shaban, B.; et al. MetaGenePipe: An Automated, Portable Pipeline for Contig-based Functional and Taxonomic Analysis. ( 2022. [CrossRef]

- Kieser, S.; Brown, J.; Zdobnov, E.M.; Trajkovski, M.; McCue, L.A. ATLAS: A Snakemake workflow for assembly, annotation, and genomic binning of metagenome sequence data. BMC Bioinformatics 2020, 21, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salazar, V.W.; et al. Metaphor—A workflow for streamlined assembly and binning of metagenomes. GigaScience 2023, 12, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mainguy, J.; et al. metagWGS, a comprehensive workflow to analyze metagenomic data using Illumina or PacBio HiFi reads. ( 2024.

- Uritskiy, G.V.; Diruggiero, J.; Taylor, J. MetaWRAP - A flexible pipeline for genome-resolved metagenomic data analysis. Microbiome 2018, 6, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziemski, M.; et al. MOSHPIT: accessible, reproducible metagenome data science on the QIIME 2 framework. ( 2025.

- Liu, L.; Yang, Y.; Deng, Y.; Zhang, T. Nanopore long-read-only metagenomics enables complete and high-quality genome reconstruction from mock and complex metagenomes. Microbiome 2022, 10, 209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krakau, S.; Straub, D.; Gourlé, H.; Gabernet, G.; Nahnsen, S. nf-core/mag: a best-practice pipeline for metagenome hybrid assembly and binning. NAR Genomics Bioinforma. 2022; 4. [Google Scholar]

- Almeida, F.M.d.; Campos, T.A.d.; Pappas, G.J. Scalable and versatile container-based pipelines for de novo genome assembly and bacterial annotation. F1000Research 2023, 12, 1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadrent, N.; et al. SnakeMAGs: a simple, efficient, flexible and scalable workflow to reconstruct prokaryotic genomes from metagenomes. F1000Research 2023, 11, 1522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamames, J.; Puente-Sánchez, F. SqueezeMeta, a highly portable, fully automatic metagenomic analysis pipeline. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 3349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clarke, E.L.; et al. Sunbeam: An extensible pipeline for analyzing metagenomic sequencing experiments. Microbiome 2019, 7, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breitwieser, F.P.; Baker, D.N.; Salzberg, S.L. KrakenUniq: confident and fast metagenomics classification using unique k-mer counts. Genome Biol. 2018, 19, 198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, D.D.; et al. MetaBAT 2: An adaptive binning algorithm for robust and efficient genome reconstruction from metagenome assemblies. PeerJ, 2019; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Alneberg, J.; et al. Binning metagenomic contigs by coverage and composition. Nat. Methods 2014, 11, 1144–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.W.; Simmons, B.A.; Singer, S.W. MaxBin 2.0: an automated binning algorithm to recover genomes from multiple metagenomic datasets. Bioinformatics 2016, 32, 605–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, E.D.; Heidelberg, J.F.; Tully, B.J. BinSanity: unsupervised clustering of environmental microbial assemblies using coverage and affinity propagation. PeerJ 2017, 5, e3035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bolger, A.M.; Lohse, M.; Usadel, B. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 2114–2120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, A. FastQC A Quality Control tool for High Throughput Sequence Data. ( 2010.

- Magoč, T.; Salzberg, S.L. FLASH: fast length adjustment of short reads to improve genome assemblies. Bioinformatics 2011, 27, 2957–2963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ontiveros-Palacios, N.; et al. Rfam 15: RNA families database in 2025. Nucleic Acids Res. 2025, 53, D258–D267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maidak, B.L.; et al. The RDP (Ribosomal Database Project). Nucleic Acids Res. 1997, 25, 109–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quast, C.; et al. The SILVA ribosomal RNA gene database project: improved data processing and web-based tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013, 41, D590–D596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benavides, A.; Isaza, J.P.; Niño-García, J.P.; Alzate, J.F.; Cabarcas, F. CLAME: a new alignment-based binning algorithm allows the genomic description of a novel Xanthomonadaceae from the Colombian Andes. BMC Genomics, 2018; 19. [Google Scholar]

- Nurk, S.; Meleshko, D.; Korobeynikov, A.; Pevzner, P.A. MetaSPAdes: A new versatile metagenomic assembler. Genome Res. 2017, 27, 824–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zerbino, D.R.; Birney, E. Velvet: Algorithms for de novo short read assembly using de Bruijn graphs. Genome Res. 2008, 18, 821–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, D.; et al. MEGAHIT v1.0: A fast and scalable metagenome assembler driven by advanced methodologies and community practices. Methods 2016, 102, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgulis, A.; et al. Database indexing for production MegaBLAST searches. Bioinformatics 2008, 24, 1757–1764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menzel, P.; Ng, K.L.; Krogh, A. Fast and sensitive taxonomic classification for metagenomics with Kaiju. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 11257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyatt, D.; et al. Prodigal: Prokaryotic gene recognition and translation initiation site identification. BMC Bioinformatics 2010, 11, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besemer, J.; Borodovsky, M. GeneMark: web software for gene finding in prokaryotes, eukaryotes and viruses. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005, 33, W451–W454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ondov, B.D.; Bergman, N.H.; Phillippy, A.M. Interactive metagenomic visualization in a Web browser. BMC Bioinformatics 2011, 12, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chklovski, A.; Parks, D.H.; Woodcroft, B.J.; Tyson, G.W. CheckM2: a rapid, scalable and accurate tool for assessing microbial genome quality using machine learning. Nat. Methods 2023, 20, 1203–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanehisa, M.; Sato, Y.; Morishima, K. BlastKOALA and GhostKOALA: KEGG Tools for Functional Characterization of Genome and Metagenome Sequences. J. Mol. Biol. 2016, 428, 726–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, J.; et al. dbCAN3: automated carbohydrate-active enzyme and substrate annotation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, 51, W115–W121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blanco-Míguez, A.; et al. Extending and improving metagenomic taxonomic profiling with uncharacterized species using MetaPhlAn 4. Nat. Biotechnol. 2021; 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Beghini, F.; et al. Integrating taxonomic, functional, and strain-level profiling of diverse microbial communities with bioBakery 3. eLife 2021, 10, e65088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, D.E.; Lu, J.; Langmead, B. Improved metagenomic analysis with Kraken 2. Genome Biol. 2019, 20, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Zheng, D.; Zhou, S.; Chen, L.; Yang, J. VFDB 2022: a general classification scheme for bacterial virulence factors. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022, 50, D912–D917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcock, B.P.; et al. CARD 2023: expanded curation, support for machine learning, and resistome prediction at the Comprehensive Antibiotic Resistance Database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, 51, D690–D699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, Y.; Gu, J. fastp: an ultra-fast all-in-one FASTQ preprocessor. Bioinformatics 2018, 34, i884–i890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langmead, B.; Salzberg, S.L. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat. Methods 2012, 9, 357–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wingett, S.W.; Andrews, S. FastQ Screen: A tool for multi-genome mapping and quality control. ( 2018.

- Benoit, G.; et al. Multiple comparative metagenomics using multiset k-mer counting. PeerJ Comput. Sci. 2016, 2, e94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parks, D.H.; Imelfort, M.; Skennerton, C.T.; Hugenholtz, P.; Tyson, G.W. CheckM: assessing the quality of microbial genomes recovered from isolates, single cells, and metagenomes. Genome Res. 2015, 25, 1043–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steinegger, M.; Söding, J. Clustering huge protein sequence sets in linear time. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 2542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Godzik, A. Cd-hit: a fast program for clustering and comparing large sets of protein or nucleotide sequences. Bioinformatics 2006, 22, 1658–1659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marçais, G.; et al. MUMmer4: A fast and versatile genome alignment system. PLOS Comput. Biol. 2018, 14, e1005944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cantalapiedra, C.P.; Hernández-Plaza, A.; Letunic, I.; Bork, P.; Huerta-Cepas, J. eggNOG-mapper v2: Functional Annotation, Orthology Assignments, and Domain Prediction at the Metagenomic Scale. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2021, 38, 5825–5829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruscheweyh, H.-J.; et al. Cultivation-independent genomes greatly expand taxonomic-profiling capabilities of mOTUs across various environments. Microbiome 2022, 10, 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Durbin, R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows–Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics 2009, 25, 1754–1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado, D.; Andrejev, S.; Tramontano, M.; Patil, K.R. Fast automated reconstruction of genome-scale metabolic models for microbial species and communities. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018, 46, 7542–7553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zelezniak, A.; et al. Metabolic dependencies drive species co-occurrence in diverse microbial communities. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2015, 112, 6449–6454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lieven, C.; et al. MEMOTE for standardized genome-scale metabolic model testing. Nat. Biotechnol. 2020, 38, 272–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seemann, T. Prokka: rapid prokaryotic genome annotation. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 2068–2069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, A.J.; et al. Roary: rapid large-scale prokaryote pan genome analysis. Bioinformatics 2015, 31, 3691–3693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emiola, A.; Oh, J. High throughput in situ metagenomic measurement of bacterial replication at ultra-low sequencing coverage. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 4956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, P.T.; Probst, A.J.; Grigoriev, I.V.; Thomas, B.C.; Banfield, J.F. Genome-reconstruction for eukaryotes from complex natural microbial communities. Genome Res. 2018, 28, 569–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saary, P.; Mitchell, A.L.; Finn, R.D. Estimating the quality of eukaryotic genomes recovered from metagenomic analysis with EukCC. Genome Biol. 2020, 21, 244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milanese, A.; et al. Microbial abundance, activity and population genomic profiling with mOTUs2. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aramaki, T.; et al. KofamKOALA: KEGG Ortholog assignment based on profile HMM and adaptive score threshold. Bioinformatics 2020, 36, 2251–2252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Líndez, P.P.; et al. Adversarial and variational autoencoders improve metagenomic binning. Commun. Biol. 2023, 6, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, S.; Zhao, X.M.; Coelho, L.P. SemiBin2: self-supervised contrastive learning leads to better MAGs for short- and long-read sequencing. Bioinformatics 2023, 39, i21–i29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manni, M.; Berkeley, M.R.; Seppey, M.; Zdobnov, E.M. BUSCO: Assessing Genomic Data Quality and Beyond. Curr. Protoc. 2021, 1, e323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orakov, A.; et al. GUNC: detection of chimerism and contamination in prokaryotic genomes. Genome Biol. 2021, 22, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mikheenko, A.; Saveliev, V.; Gurevich, A. MetaQUAST: evaluation of metagenome assemblies. Bioinformatics 2016, 32, 1088–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H. Minimap2: pairwise alignment for nucleotide sequences. Bioinformatics 2018, 34, 3094–3100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dröge, J.; Gregor, I.; McHardy, A.C. Taxator-tk: precise taxonomic assignment of metagenomes by fast approximation of evolutionary neighborhoods. Bioinformatics 2015, 31, 817–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krapohl, J.; Pickett, B.E. SnakeWRAP: a Snakemake workflow to facilitate automated processing of metagenomic data through the metaWRAP pipeline. F1000Research, 2022; 11. [Google Scholar]

- Bolyen, E.; et al. Reproducible, interactive, scalable and extensible microbiome data science using QIIME 2. Nat. Biotechnol. 2019, 37, 852–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eren, A.M.; Vineis, J.H.; Morrison, H.G.; Sogin, M.L. A Filtering Method to Generate High Quality Short Reads Using Illumina Paired-End Technology. PLOS ONE 2013, 8, e66643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aroney, S.T.N.; et al. CoverM: read alignment statistics for metagenomics. Bioinformatics 2025, 41, btaf147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchfink, B.; Reuter, K.; Drost, H.-G. Sensitive protein alignments at tree-of-life scale using DIAMOND. Nat. Methods 2021, 18, 366–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, D.E.; Salzberg, S.L. Kraken: ultrafast metagenomic sequence classification using exact alignments. Genome Biol. 2014, 15, R46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mistry, J.; et al. Pfam: The protein families database in 2021. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, D412–D419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, K.; et al. Benchmarking of analysis tools and pipeline development for nanopore long-read metagenomics. Sci. Bull. 2025, 70, 1591–1595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolmogorov, M.; et al. metaFlye: scalable long-read metagenome assembly using repeat graphs. Nat. Methods 2020, 17, 1103–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bertrand, D.; et al. Hybrid metagenomic assembly enables high-resolution analysis of resistance determinants and mobile elements in human microbiomes. Nat. Biotechnol. 2019, 37, 937–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kajitani, R.; et al. MetaPlatanus: a metagenome assembler that combines long-range sequence links and species-specific features. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, e130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Fan, J.; Sun, Z.; Liu, S. NextPolish: a fast and efficient genome polishing tool for long-read assembly. Bioinformatics 2020, 36, 2253–2255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asnicar, F.; et al. Precise phylogenetic analysis of microbial isolates and genomes from metagenomes using PhyloPhlAn 3.0. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Song, L.; Breitwieser, F.P.; Salzberg, S.L. Centrifuge: rapid and sensitive classification of metagenomic sequences. Genome Res. 2016, 26, 1721–1729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, H.; Concepcion, G.T.; Feng, X.; Zhang, H.; Li, H. Haplotype-resolved de novo assembly using phased assembly graphs with hifiasm. Nat. Methods 2021, 18, 170–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mainguy, J.; et al. metagWGS, a comprehensive workflow to analyze metagenomic data using Illumina or PacBio HiFi reads. ( 2024.

- Mainguy, J.; Hoede, C. Binette: a fast and accurate bin refinement tool to construct high quality Metagenome Assembled Genomes. J. Open Source Softw. 2024, 9, 6782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaser, R.; Sovic, I.; Nagarajan, N.; Sikic, M. Fast and accurate de novo genome assembly from long uncorrected reads. Genome Res. gr.214270.116 ( 2017. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walker, B.J.; et al. Pilon: An Integrated Tool for Comprehensive Microbial Variant Detection and Genome Assembly Improvement. PLOS ONE 2014, 9, e112963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stewart, R.D.; et al. Compendium of 4,941 rumen metagenome-assembled genomes for rumen microbiome biology and enzyme discovery. Nat. Biotechnol. 2019, 37, 953–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kieft, K.; Zhou, Z.; Anantharaman, K. VIBRANT: automated recovery, annotation and curation of microbial viruses, and evaluation of viral community function from genomic sequences. Microbiome 2020, 8, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kieft, K.; Anantharaman, K. Deciphering Active Prophages from Metagenomes. mSystems 2022, 7, e00084–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wick, R.R.; Judd, L.M.; Gorrie, C.L.; Holt, K.E. Unicycler: Resolving bacterial genome assemblies from short and long sequencing reads. PLOS Comput. Biol. 2017, 13, e1005595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, D.D.; Froula, J.; Egan, R.; Wang, Z. MetaBAT, an efficient tool for accurately reconstructing single genomes from complex microbial communities. PeerJ 2015, 3, e1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brůna, T.; Hoff, K.J.; Lomsadze, A.; Stanke, M.; Borodovsky, M. BRAKER2: automatic eukaryotic genome annotation with GeneMark-EP+ and AUGUSTUS supported by a protein database. NAR Genomics Bioinforma. 2021, 3, lqaa108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meunier, L.; Baurain, D.; Cornet, L. AMAW: automated gene annotation for non-model eukaryotic genomes. ( 2023. [CrossRef]

- Irber, L.; et al. sourmash v4: A multitool to quickly search, compare, and analyze genomic and metagenomic data sets. J. Open Source Softw. 2024, 9, 6830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parks, D.H.; et al. GTDB: an ongoing census of bacterial and archaeal diversity through a phylogenetically consistent, rank normalized and complete genome-based taxonomy. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022, 50, D785–D794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grabherr, M.G.; et al. Full-length transcriptome assembly from RNA-Seq data without a reference genome. Nat. Biotechnol. 2011, 29, 644–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patro, R.; Duggal, G.; Love, M.I.; Irizarry, R.A.; Kingsford, C. Salmon provides fast and bias-aware quantification of transcript expression. Nat. Methods 2017, 14, 417–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schubert, M.; Lindgreen, S.; Orlando, L. AdapterRemoval v2: rapid adapter trimming, identification, and read merging. BMC Res. Notes 2016, 9, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- von Meijenfeldt, F.A.B.; Arkhipova, K.; Cambuy, D.D.; Coutinho, F.H.; Dutilh, B.E. Robust taxonomic classification of uncharted microbial sequences and bins with CAT and BAT. Genome Biol. 2019, 20, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy Karin, E.; Mirdita, M.; Söding, J. MetaEuk—sensitive, high-throughput gene discovery, and annotation for large-scale eukaryotic metagenomics. Microbiome 2020, 8, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borry, M.; Hübner, A.; Rohrlach, A.B.; Warinner, C. PyDamage: automated ancient damage identification and estimation for contigs in ancient DNA de novo assembly. PeerJ 2021, 9, e11845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlicki, M.; Antonowicz, S.; Karnkowska, A. Tiara: deep learning-based classification system for eukaryotic sequences. Bioinformatics 2022, 38, 344–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camargo, A.P.; et al. Identification of mobile genetic elements with geNomad. Nat. Biotechnol. 2024, 42, 1303–1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ewels, P.; Magnusson, M.; Lundin, S.; Käller, M. MultiQC: summarize analysis results for multiple tools and samples in a single report. Bioinformatics 2016, 32, 3047–3048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koren, S.; et al. Canu: scalable and accurate long-read assembly via adaptive k-mer weighting and repeat separation. Genome Res. 2017, 27, 722–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwengers, O.; et al. Bakta: Rapid and standardized annotation of bacterial genomes via alignment-free sequence identification. Microb. Genomics 2021, 7, 000685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jolley, K.A.; Maiden, M.C. BIGSdb: Scalable analysis of bacterial genome variation at the population level. BMC Bioinformatics 2010, 11, 595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blin, K.; et al. antiSMASH 7.0: new and improved predictions for detection, regulation, chemical structures and visualisation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, 51, W46–W50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, K.; Huang, N.; Zou, Y.; Liao, X.; Wang, J. MultiNanopolish: refined grouping method for reducing redundant calculations in Nanopolish. Bioinformatics 2021, 37, 2757–2760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bushmanova, E.; Antipov, D.; Lapidus, A.; Prjibelski, A.D. rnaSPAdes: a de novo transcriptome assembler and its application to RNA-Seq data. GigaScience 2019, 8, giz100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caspi, R.; et al. The MetaCyc database of metabolic pathways and enzymes - a 2019 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020, 48, D445–D453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillespie, J.J.; et al. PATRIC: the Comprehensive Bacterial Bioinformatics Resource with a Focus on Human Pathogenic Species. Infect. Immun. 2011, 79, 4286–4298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brettin, T.; et al. RASTtk: A modular and extensible implementation of the RAST algorithm for building custom annotation pipelines and annotating batches of genomes. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 8365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Sundaram, J.P.; Spiro, D. VIGOR, an annotation program for small viral genomes. BMC Bioinformatics 2010, 11, 451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seaver, S.M.D.; et al. The ModelSEED Biochemistry Database for the integration of metabolic annotations and the reconstruction, comparison and analysis of metabolic models for plants, fungi and microbes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021; 49, D575–D588 . [Google Scholar]

- Zdobnov, E.M.; Apweiler, R. InterProScan – an integration platform for the signature-recognition methods in InterPro. Bioinformatics 2001, 17, 847–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finn, R.D.; Clements, J.; Eddy, S.R. HMMER web server: interactive sequence similarity searching. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011, 39, W29–W37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Standeven, F.J.; Dahlquist-Axe, G.; Speller, C.F.; Meehan, C.J.; Tedder, A. An efficient pipeline for creating metagenomic-assembled genomes from ancient oral microbiomes. ( 2024.

- Jónsson, H.; Ginolhac, A.; Schubert, M.; Johnson, P.L.F.; Orlando, L. mapDamage2.0: fast approximate Bayesian estimates of ancient DNA damage parameters. Bioinformatics 2013, 29, 1682–1684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Nguyen, H.; Lavenier, D. PLAST: parallel local alignment search tool for database comparison. BMC Bioinformatics 2009, 10, 329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.-H.; Liao, Y.-C. Accurate binning of metagenomic contigs via automated clustering sequences using information of genomic signatures and marker genes. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 24175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yepes-García, J.; Falquet, L. Metagenome quality metrics and taxonomical annotation visualization through the integration of MAGFlow and BIgMAG. F1000Research, 2024; 13, 640. [Google Scholar]

- Cansdale, A.; Chong, J.P.J. MAGqual: a stand-alone pipeline to assess the quality of metagenome-assembled genomes. Microbiome 2024, 12, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wood, J.M.; et al. Performance of Multiple Metagenomics Pipelines in Understanding Microbial Diversity of a Low-Biomass Spacecraft Assembly Facility. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, F.; et al. Tutorial: assessing metagenomics software with the CAMI benchmarking toolkit. Nat. Protoc. 2021, 16, 1785–1801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).