Submitted:

06 June 2025

Posted:

10 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

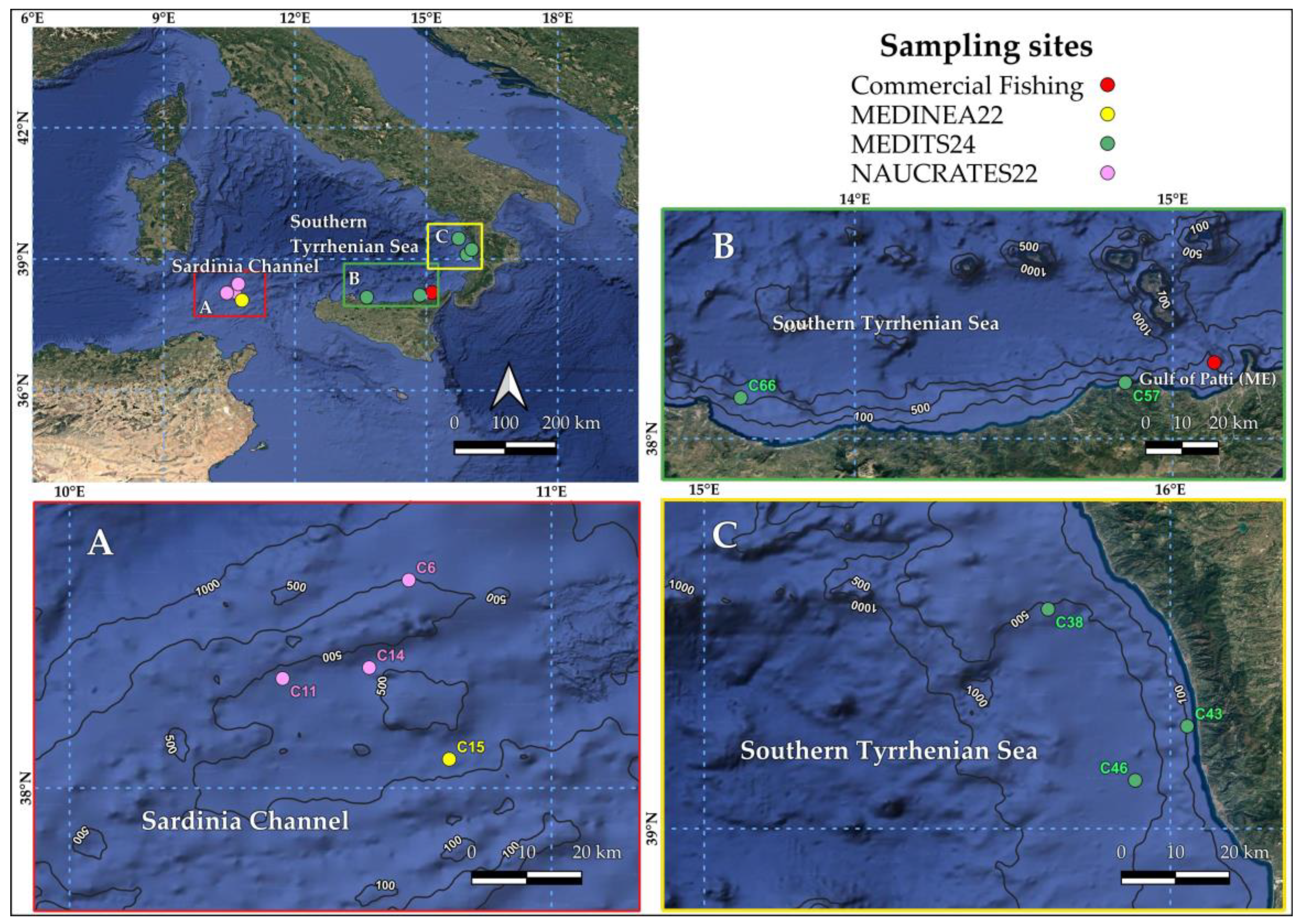

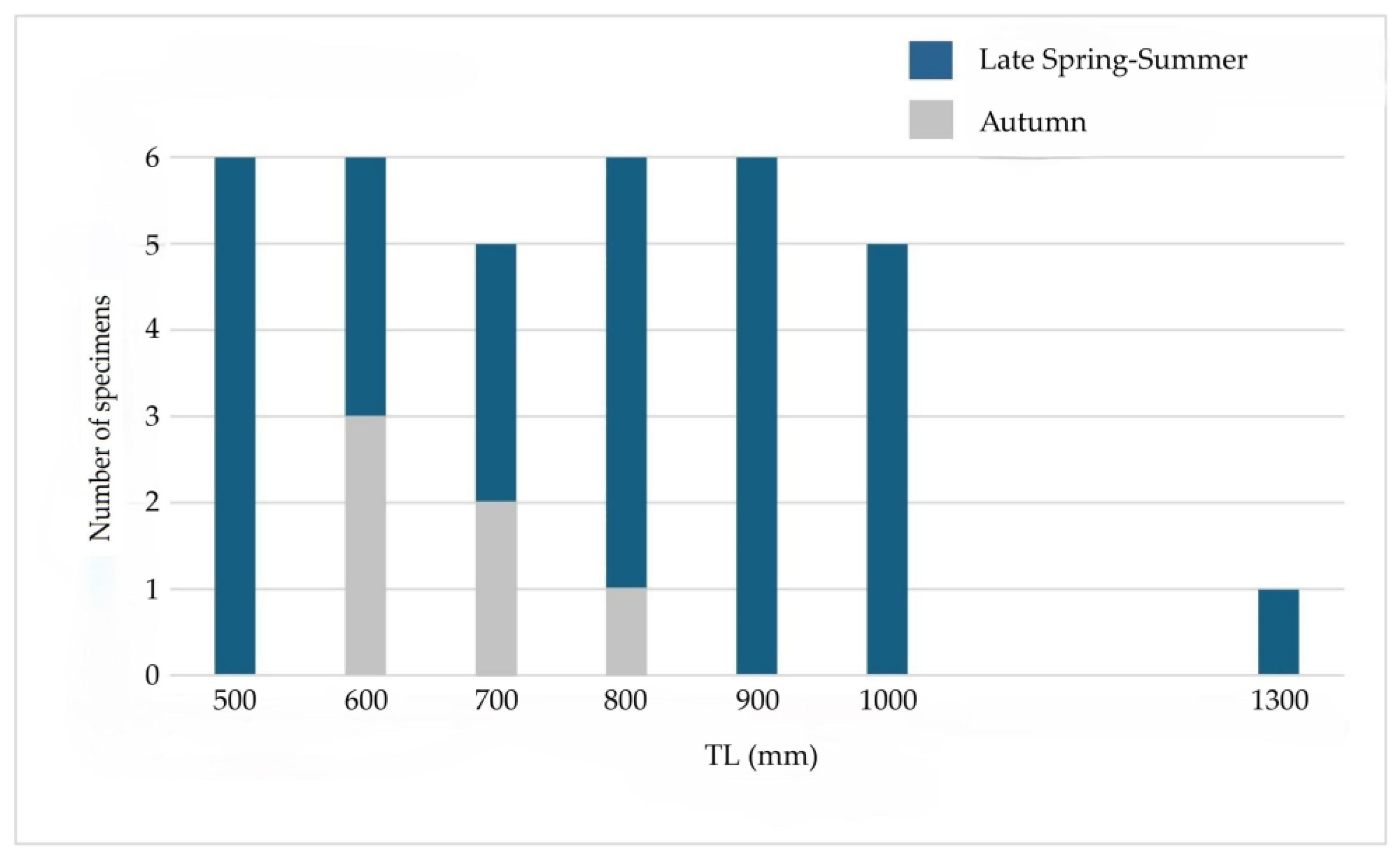

2.1. Study Area and Samples Collection

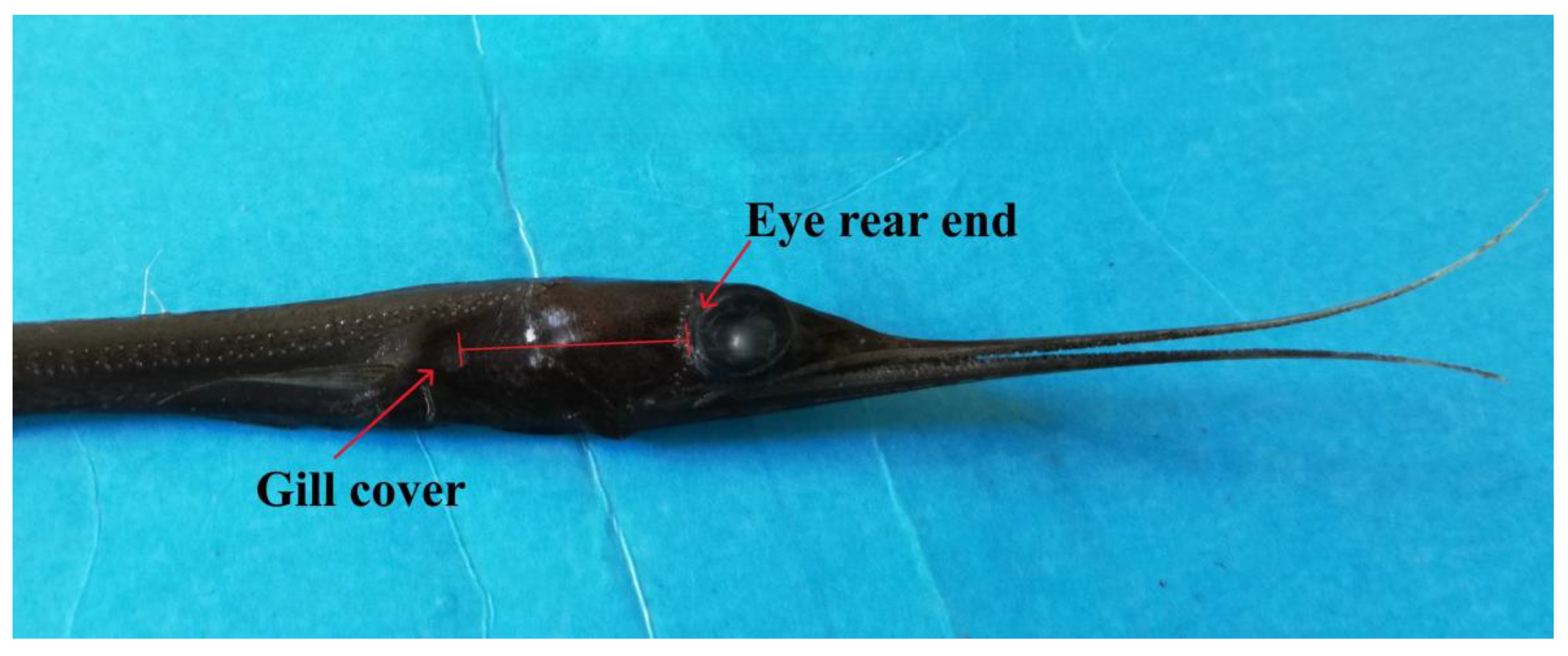

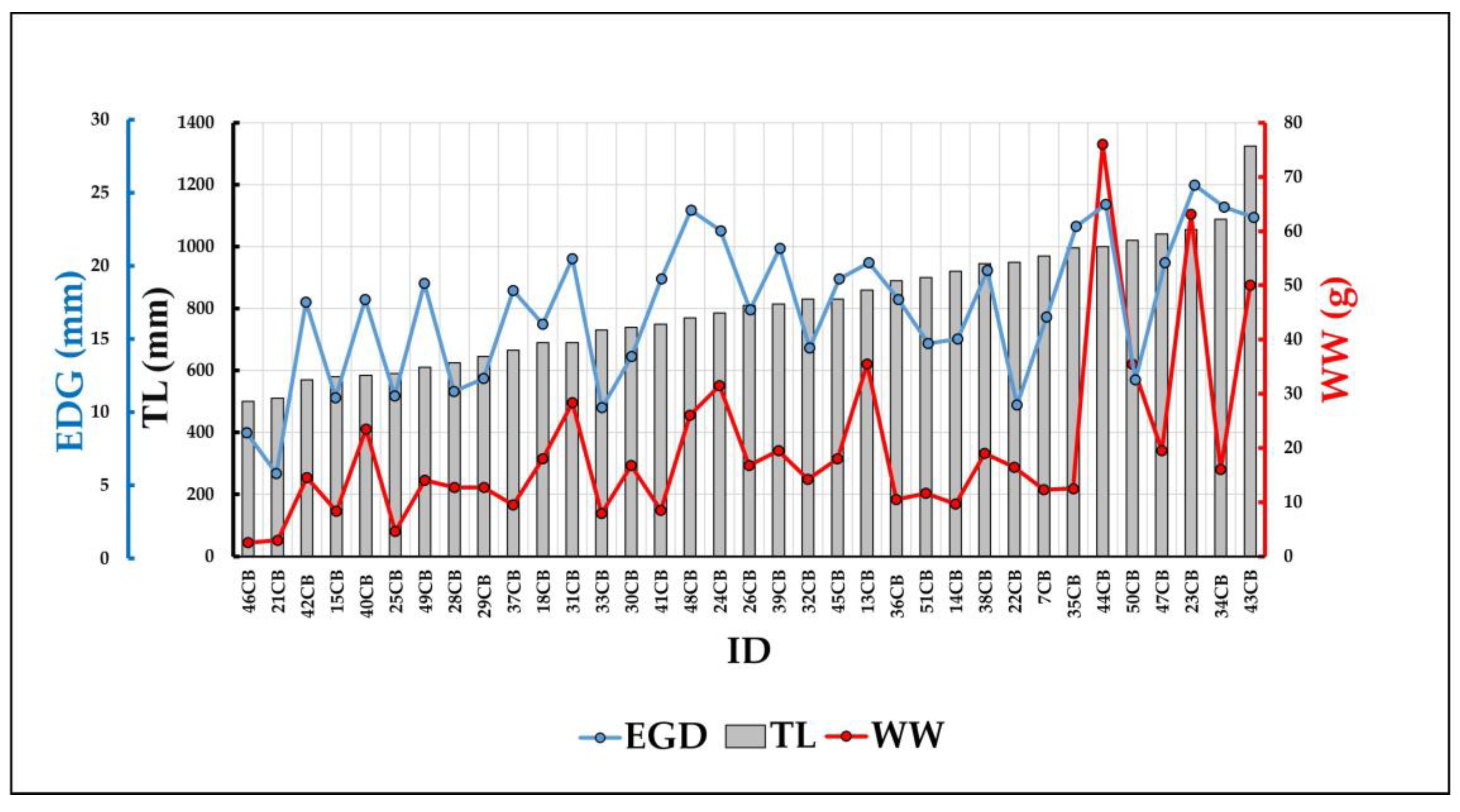

2.2. Laboratory Analysis

2.3. Trophic Indexes

3. Results

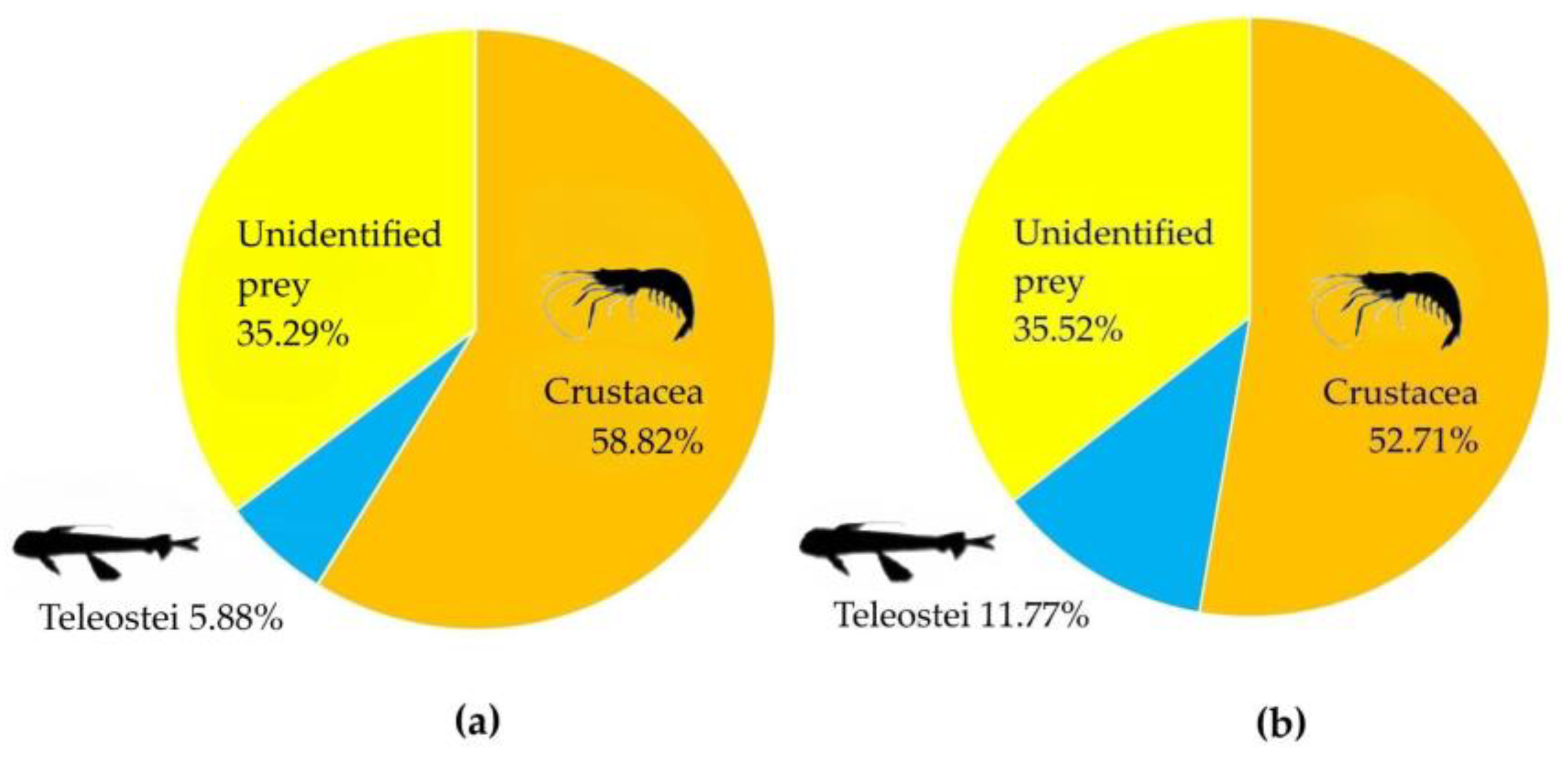

3.1. Trophic Ecology

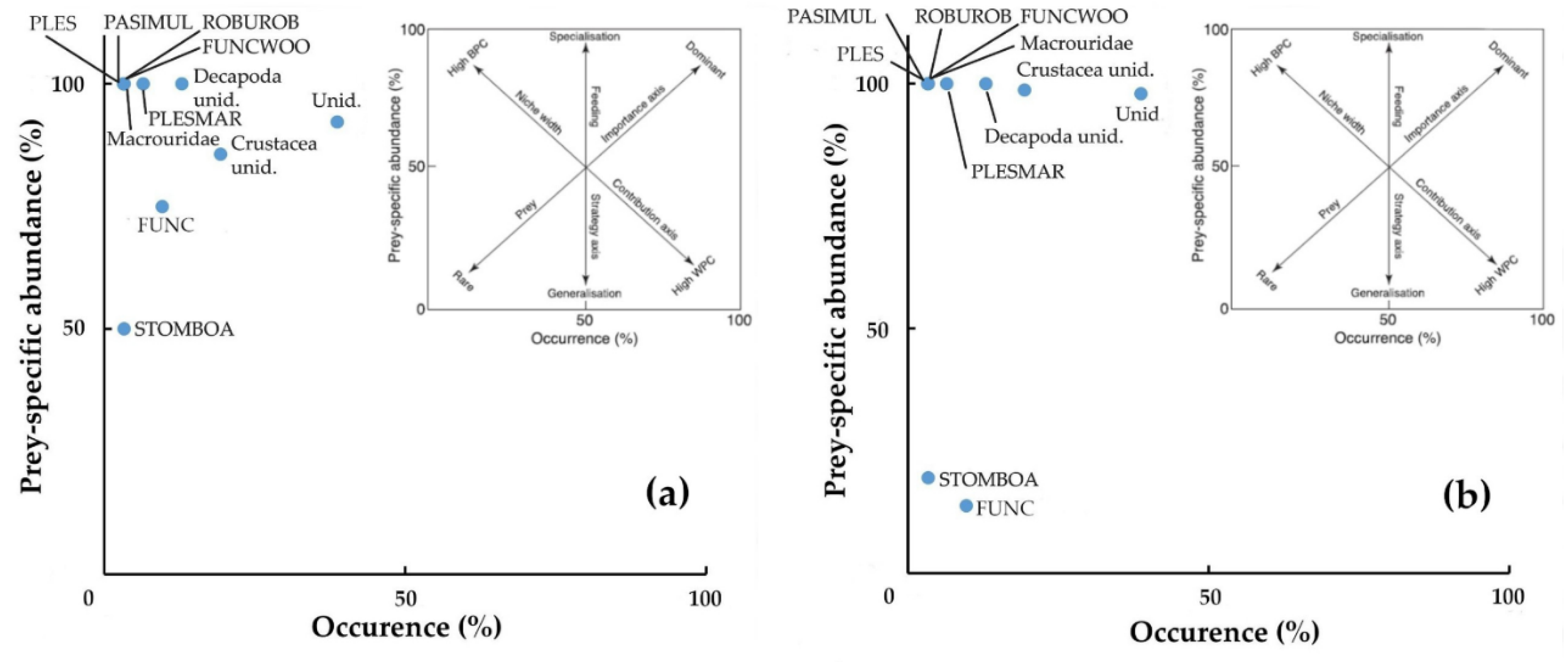

3.2. Feeding Strategy

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bilecenoglu, M.; Kaya, M.; Irmak, E. First records of the slender snipe eel, Nemichthys scolopaceus (Nemichthyidae), and the robust cusk-eel, Benthocometes robustus (Ophidiidae), from the Aegean Sea. Acta ichthyologica et piscatoria 2006, 36, 85–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, J.G.; Smith, D.G. The eel family Nemichthyidae (Pisces, Anguilliformes). Dana Report 1978, 88. [Google Scholar]

- Fishelson, L. Comparative morphology of deep-sea eels, with particular emphasis on gonads and gut structure. J. Fish. Biol. 1994, 44, 75–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, D.G.; Tighe, K.A. Snipe eels. Family Nemichthyidae. In: Collette, B.B.; Klein-MacPhee G (eds) Fishes of the Gulf of Maine 3rd edn; Smithsonian Institute Press, Washington, D.C. 2002, pp. 100–101.

- Karmovskaya, E.S. Systematics and some ecology of the snipe eels of the family Nemichthyidae. Proc. PP Shirshov Inst. Oceanol. 1982, 118, 151–161. [Google Scholar]

- Feagans-Bartow, J. N.; Sutton, T. T. Ecology of the oceanic rim: Pelagic eels as key ecosystem components. Marine Ecology Progress Series 2014, 502, 257–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gartner, J.V. Jr.; Sulak, K.J.; Ross, S.W.; Necaise, A.M. Persistent near-bottom aggregations of mesopelagic animals along the North Carolina and Virginia continental slopes. Mar. Biol. 2008, 153, 825–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, D.G.; Nielsen, J.G. Family Nemichthyidae: Snipe eels. In: Böhlke, E.B. (ed) Fishes of the western North Atlantic, Part 9, Vol 1. Sears Foundation for Marine Research, New Haven, CT 1989, pp 441-459. [CrossRef]

- Charter, S.R. Nemichthyidae: Snipe eels. In: H.G. Moser (ed.) The early stages of fishes in the California Current region. California Cooperative Oceanic Fisheries Investigations (CalCOFI) Atlas 1996, 33, 122–129.

- Bayhan, Y. K.; Ergüden, D.; Ayas, D. The first occurrence of male specimen of Nemichthys scolopaceus (Richardson, 1848) from Eastern Mediterranean. Turkish Journal of Maritime and Marine Sciences 2020, 6, 137–143. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, M.; Koyama, S.; Mochioka, N.; Aoyama, J.; Watanabe, S.; Tsukamoto, K. Vertical body orientation by a snipe eel (Nemichthyidae, Anguilliformes) in the deep mesopelagic zone along the West Mariana Ridge. Marine and Freshwater Behaviour and Physiology 2014, 47, 265–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gartner, J.V. Jr.; Crabtree, R.E.; Sulak, K.J. Feeding at depth. In: Randall, D.J.; Farrell, A.P. (eds). Deep-sea fishes. New York (NY), Academic Press; pp. 115–193. Marine and Freshwater Behaviour and Physiology 1997, 271. [CrossRef]

- Merrett, N.R. Biogeography and the oceanic rim: A poorly known zone of ichthyofaunal interaction. Pelagic Biogeography, Proc of an Int Symposium. UNESCO Tech. Pap. Mar. Sci 1986, 49, 201–209. [Google Scholar]

- Bucklin, A.; Batta-Lona, P.G.; Questel, J.M.; McMonagle, H.; Wojcicki, M.; Llopiz, J.K.; Wiebe, P.H. Metabarcoding and morphological analysis of diets of mesopelagic fishes in the NW Atlantic Slope Water. Frontiers in Marine Science 2024, 11, 1411996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feagans, J. N. Trophic ecology of the slender snipe eel, Nemichthys scolopaceus (Anguilliformes: Nemichthyidae). M.S. thesis 2008. Boca Raton (FL) Florida Atlantic University, p. 30.

- Falciai, L.; Minervini, R. Guida ai crostacei decapodi d'Europa Seconda edizione. Ricca editore . 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Tuset, V.M.; Lombarte, A.; Assis, C.A. Otolith atlas for the western Mediterranean, north and central eastern Atlantic. Scientia Marina 2008, 72(S1), 7–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, D.M.; Inada, T.; Iwamoto, T.; Scialabba. Gadiform Fishes of the World. FAO Fisheries Synopsis 1990, 125 (10), pp. 453.

- Bräger, Z.; Moritz, T. A scale atlas for common Mediterranean teleost fishes. Vertebrate zoology 2016, 66, 275–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apollonio, S. Breeding Fecundity of the Glass Shrimp, Pasiphaea multidentata (Decapoda, Caridea), in the Gulf of Maine. Journal Fisheries Research Board of Canada 1969, 26, 1969–1983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Company, J. B.; Sardà, F. Growth parameters of deep-water decapod crustaceans in the Northwestern Mediterranean Sea: A comparative approach. Marine Biology 2000, 136, 79–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chilari, A.; Thessalou-Legaki, M.; Petrakis, G. Population structure and reproduction of the deep-water shrimp Plesionika martia (decapoda: Pandalidae) from the eastern Ionian Sea. Journal of Crustacean Biology 2005, 25, 233–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Başusta, N.; Başusta, A. Length- Weight Relationship and Condition Factor of Hollowsnout grenadier (Coelorinchus caelorhincus, (Rinso, 1810) From Iskenderun Bay, northeastern Mediterranean, Turkey. International Marine & Freshwater Sciences Symposium Proceedings (MARFRESH2018). In: Özcan G, Tarkan A.S, Özcan T. (Eds.). 2018. Proceeding Book, International Marine & Freshwater Sciences Symposium, 18-21 October 2018, Kemer-Antalya/Turkey 2018, 300-302.

- Sousa, R.; Gouveia, L.; Pinto, A. R.; Timóteo, V.; Delgado, J.; Henriques, P. Weight-length relationships of six shrimp species caught off the Madeira Archipelago, Northeastern Atlantic. Brazilian Journal of Biology 2018, 79, 133–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerra-Marrero, A.; Caballero-Méndez, C.; Espino-Ruano, A.; Couce-Montero, L.; Jiménez-Alvarado, D.; Castro, J. J. Length-weight relationships of 15 mesopelagic shrimp species caught during exploratory surveys off the Canary Islands (central eastern Atlantic). Scientia Marina 2024, 88, e081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinkas, L.; Oliphant, M.S.; Iverson, I.L.K. Food habits of albacore, bluefin tuna and bonito in California waters. California Department of Fish and Game’s Fish Bulletin 1971, 152, 1–105. [Google Scholar]

- Hyslop, E.J. Stomach content analysis: A review of methods and their application. Journal of Fish Biology 1980, 17, 411–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hacunda, J.S. Trophic relationships among demersal fishes in a coastal area of the Gulf of Maine. Fishery Bulletin 1981, 79, 775–788. [Google Scholar]

- Costello, M.J. Predator feeding strategy and prey importance: A new graphical analysis. Journal of Fish Biology 1990, 36, 261–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amundsen, P.A.; Gabler, H.M.; Staldvik, F.J. A new approach to graphical analysis of feeding strategy from stomach contents data modification of the Costello (1990) method. J. Fish. Biol. 1996, 48, 607–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pauly, D.; Christensen, V. Primary production required to sustain global fisheries. Nature 1995, 374, 255–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pauly, D.; Trites, A.W.; Capuli, E.V.; Christensen, V. Diet composition and trophic levels of marine mammals. ICES J. Mar. Sci 1998, 55, 467–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pauly, D.; Froese, R.; Sa-a, P.; Palomares, M.; Christensen, V.; Rius, J. TrophLab Manual. ICLARM 2000, Manila, Philippines.

- Pauly, D.; Palomares, M.L. Approaches for dealing with three sources of bias when studying the fishing down marine food web phenomenon. CIESM Work. Ser. 2000, 12, 61–66. [Google Scholar]

- Pandian, T.J. Intake, digestion, absorption, and conversion of food in the fishes Megalops cyprinoides and Ophiocephalus striatus. Mar. Biol. 1967, 1, 16–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandian, T.J. Transformation of food in the fish Megalops cyprinoides. I. Influence of quality of food. Mar Biol 1967, 1, 60–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cartes, J. E. Diets of deep-water pandalid shrimps on the Western Mediterranean slope. Marine Ecology Progress Series 1993, 96, 49–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cartes, J. E. Feeding habits of pasiphaeid shrimps close to the bottom on the western Mediterranean slope. Marine Biology 1993, 117, 459–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mead, G.W.; Earle, S.A. Notes on the natural history of snipe eels. Proc. Calif. Acad. Sci. 1970, 99–103. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, D.G.; Tighe, K.A. Snipe eels. Family Nemichthyidae. In: Collette B.B., Klein-MacPhee G (eds) Fishes of the Gulf of Maine. 3rd edn. Smithsonian Institute Press, Washington, DC 2002, pp. 100–101.

| Campaign | Fishing Area | Local Date | Lat. N | Long. E | Sampling depth (m) | Local time (Start-Finish) |

Specimens caught (per time) |

Specimen ID number |

| Commercial fishing | Gulf of Patti (ME) | May-June 2022 | 38°14.346' | 15°7.818' | 300-700 | - | 11 | 7CB, 13CB, 14CB, 15CB, 18CB, 21CB, 22CB, 23CB, 24CB, 25CB, 26CB |

| May-June 2023 | - | 12 | 34CB, 35CB, 36CB, 37CB, 38CB, 39CB, 40CB, 41CB, 42CB, 47CB, 48CB, 49CB | |||||

| NAUCRATES22 | Pa-Ca Canyon | 12/10/2022 | 38°25.91' | 10°42.24' | 309-305 | 12:53-17:35 | 1 | 28CB |

| 19/10/2022 | 38°13.65' | 10°37.32' | 323-358 | 22:20-1:47 | 1 | 31CB | ||

| 14/10/2022 | 38°15.00' | 10°37.32' | 370-311 | 12:30-16:33 | 2 | 32CB, 33CB | ||

| MEDINEA22 | Pa-Ca Canyon | 14/10/2022 | 38°03.60' | 10°47.28' | 332-349 | 19:07-23:07 | 2 | 29CB, 30CB |

| MEDITS24 | GSA10 | 21/06/2024 | 39° 28.24' | 15° 44.27' | 583-626 | 07:13-08:13 | 2 | 44CB, 45CB |

| 22/06/2024 | 39° 13.18' | 16° 02.19' | 83-86 | 06:51-07:21 | 1 | 50CB | ||

| 22/06/2024 | 39° 06.21' | 15° 55.49' | 634-619 | 14:46-15:46 | 1 | 46CB | ||

| 25/06/2024 | 38° 10.56' | 14° 51.02' | 26-18 | 12:00-12:30 | 1 | 51CB | ||

| 26/06/2024 | 38° 07.70' | 13° 38.44' | 568-529 | 16:15-17:15 | 1 | 43CB |

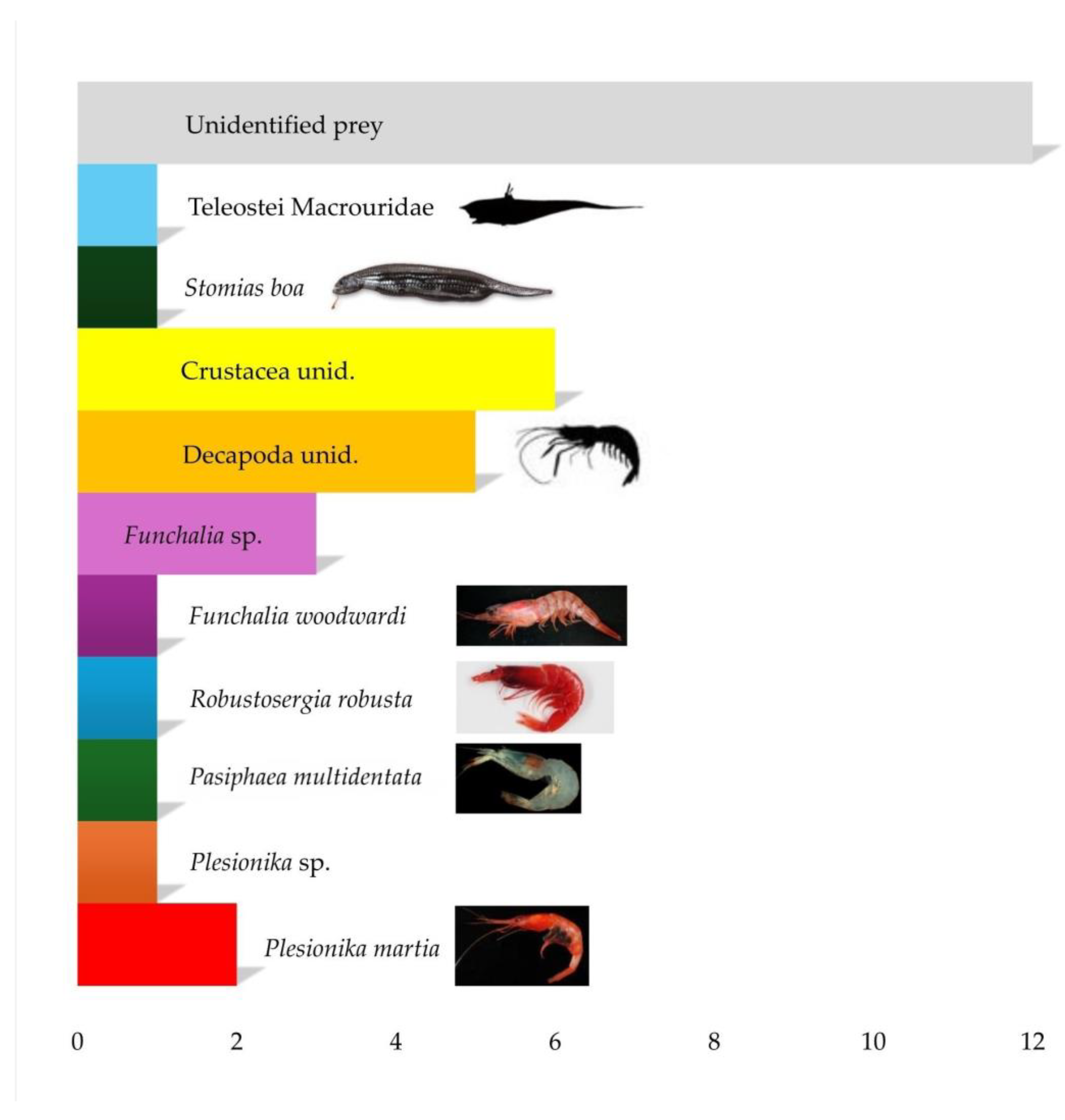

| Phylum/ Subphylum/ Class/Order |

Family | Species/Taxa | %Ni | %Wi | %Fi | %IRIi |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ARTROPODA | ||||||

| CRUSTACEA | ||||||

| Malacostraca | ||||||

| Decapoda | Pandalidae |

Plesionika martia (A. Milne-Edwards, 1883) |

5.88 | 9.31 | 6.45 | 10.46 |

| Plesionika sp. | 2.94 | 8.33 | 3.23 | 15.19 | ||

| Pasiphaeidae | Pasiphea multidentata Esmark, 1866 | 2.94 | 4.65 |

3.23 | 10.47 |

|

| Sergestidae | Robustosergia robusta (Smith, 1882) | 2.94 | 0.78 |

3.33 | 5.53 |

|

| Peneidae | Funchalia woodwardi Johnson, 1868 | 2.94 | 0.23 |

3.33 | 4.82 |

|

| Funchalia sp. | 8.82 | 0.43 | 9.68 | 4.70 | ||

| Decapoda unid. | 14.71 | 13.18 | 12.90 | 8.10 | ||

| Crustacea unid. | 17.65 | 15.81 | 19.35 | 7.45 | ||

| CHORDATA | ||||||

| VERTEBRATA | ||||||

| Teleostei | ||||||

| Stomiiformes | Stomiidae |

Stomias boa (Risso, 1810) |

2.94 | 0.72 |

3.33 | 5.44 |

| Gadiformes | Macrouridae | Macrouridae unid. | 2.94 | 11.05 | 3.33 | 18.66 |

| Unidentified | 35.29 | 35.42 | 40.00 | 9.17 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).