Submitted:

28 July 2023

Posted:

31 July 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

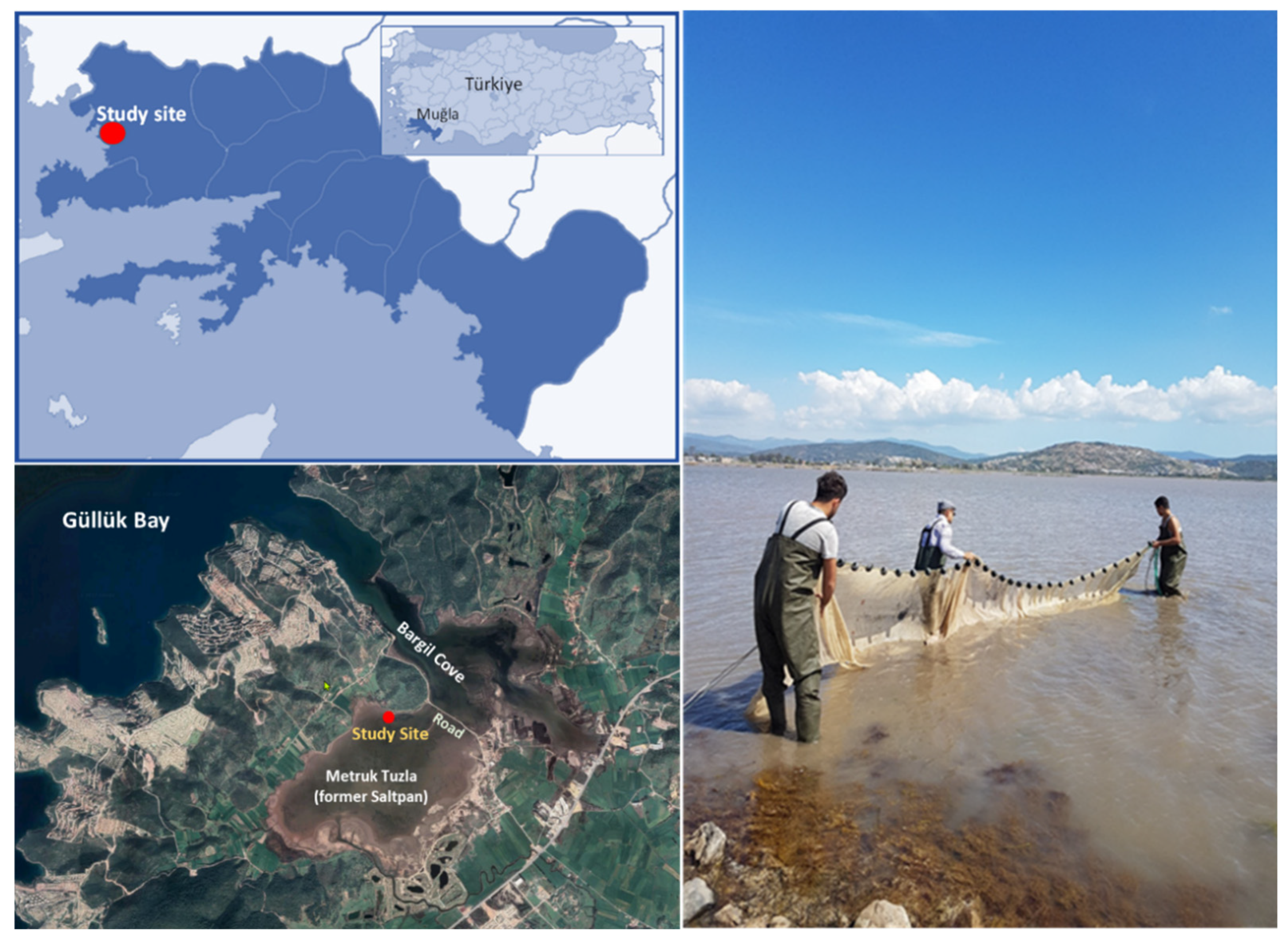

2.1. Study site and fish collection

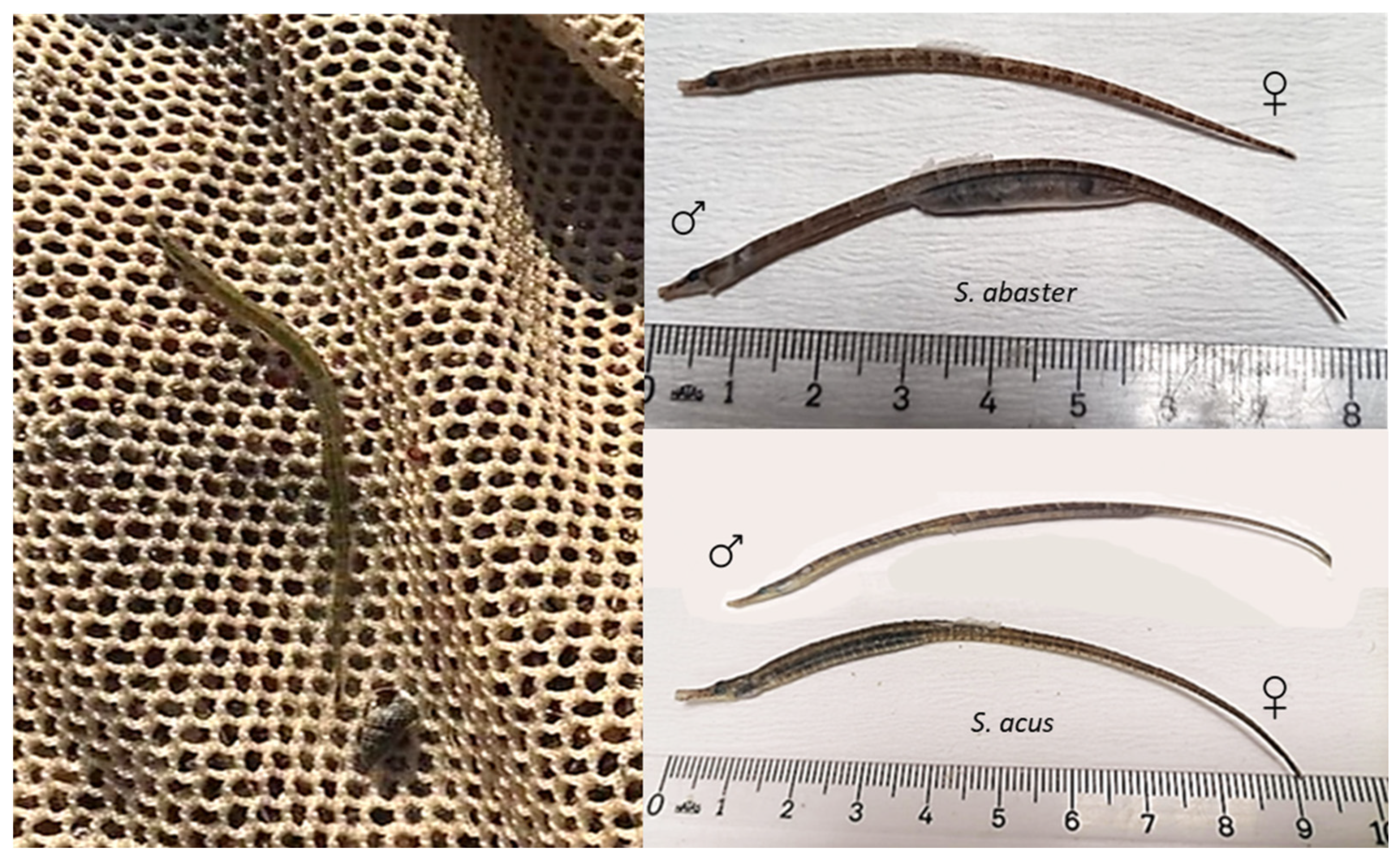

2.2. Fish sampling and analyses

2.3. Stable isotopes

2.4. Data treatment

2.5. Bioethics

3. Results

3.1. Abiotic data

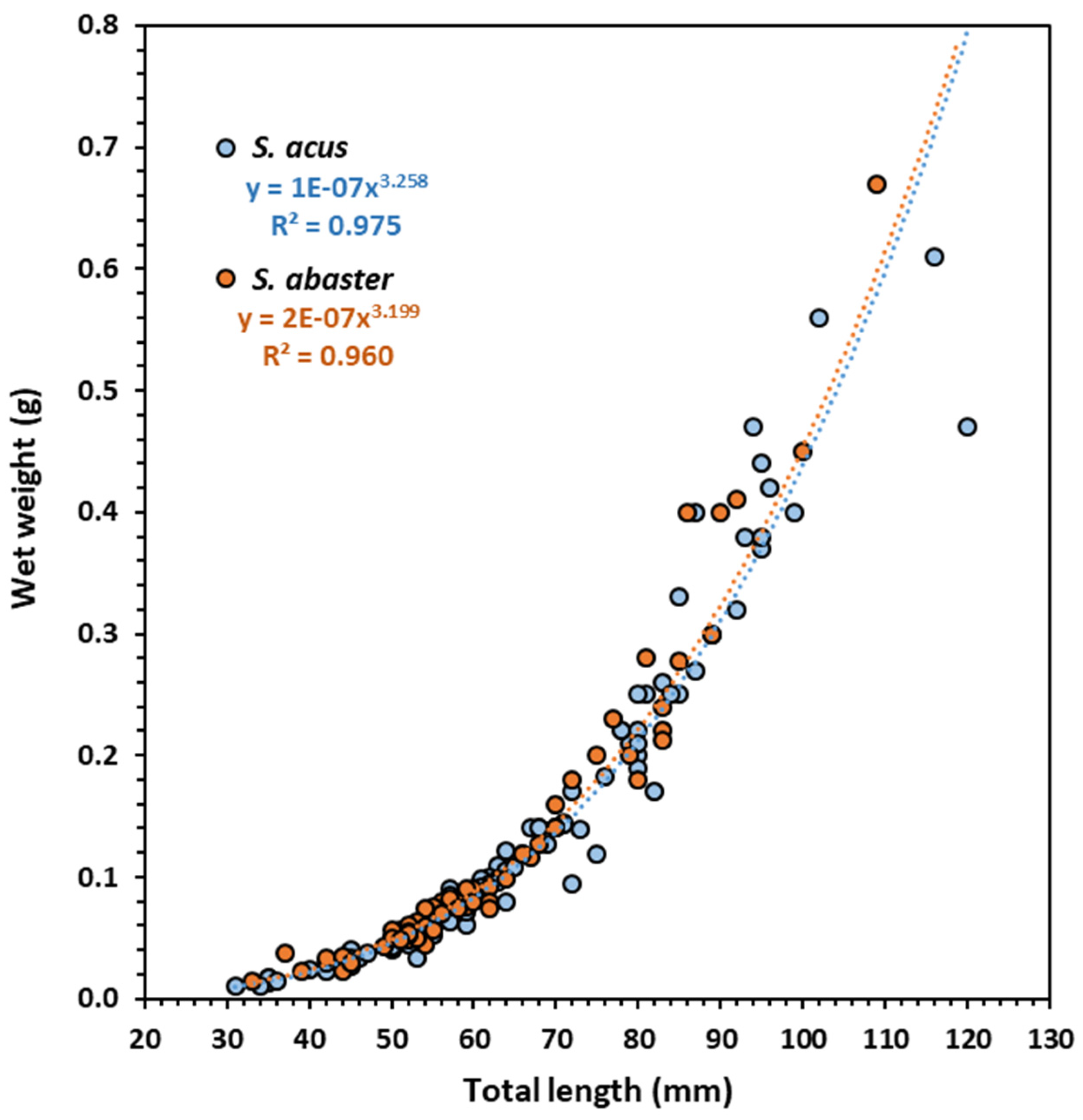

3.2. Fish populations

3.3. Gut content

3.4. Isotopic profiles

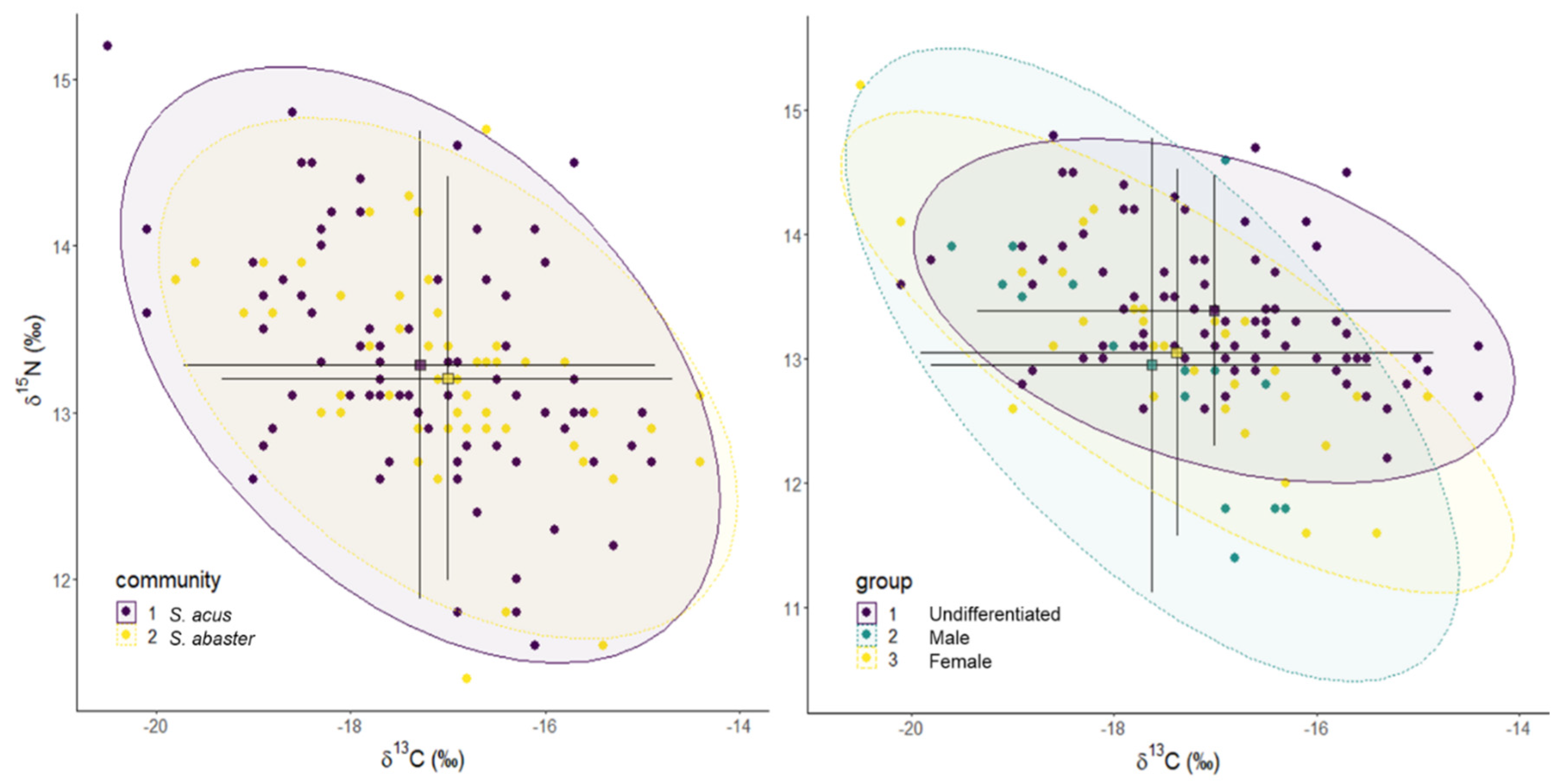

3.5. Trophic structure and niche overlap

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

- -

- Iterations: 20210:40000

- -

- Thinning interval: 10

- -

- Number of chains: 5

- -

- Sample size per chain: 2000

References

- Cherry, J. A. Ecology of wetland ecosystems: Water, substrate, and life. Nat. Educ. Know. 2011. 3(10), 16. [Google Scholar]

- Whittaker, R.H.; Likens, G.E. Carbon in the biota. In Carbon in the Biosphere; Woodwell, G. M., Peacan, E. R. Peacan, Eds.; National Technical Information Service: Springfield, VA, 1973; pp. 281–302. [Google Scholar]

- Curebal, I. , Efe, R., Soykan, A.; Sonmez, S. Impacts of anthropogenic factors on land degradation during the Anthropocene in Turkey. J. of Environ. Bio. 2015. 36(1), 51-58. [Google Scholar]

- Murat, A.; Ortaç, O. Wetland loss in Turkey over a hundred years: implications for conservation and management. Ecosyst. Health Sustain. 2021; 7(1),1930587.

- Çolak, M.A.; Öztaş, B.; Özgencil, İ.K.; Soyluer, M.; Korkmaz, M.; Ramírez-García, A.; Metin, M.; Yılmaz, G.; Ertuğrul, S.; Tavşanoğlu, Ü.N.; et al. Increased water abstraction and climate change have substantial effect on morphometry, salinity, and biotic communities in lakes: Examples from the semi-arid Burdur Basin (Turkey). Water 2022, 14, 1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somay-Altaş, A.M. Hydrogeochemical fingerprints of a mixohaline wetland in the Mediterranean: Güllük coastal wetland systems- GCWS (Muğla, Turkey). Turkish J Earth Sci 2021, 30, 38–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anonymous. Gediz Delta Wetland Management Plan. T.R. Ministry of Environment and Forestry, General Directorate of Nature Conservation and National Parks, Department of Nature Conservation, Directorate of Wetlands Branch, 2007, 424 p. (in Turkish).

- Tosunoğlu, Z.; Ünal, V.; Kaykaç, M.H. Ege Dalyanları. SÜR-KOOP Su Ürünleri Kooperatifleri Merkez Birliği Yayınları No: 03, ISBN:978-605-60880-2-5, Ankara, 2017, 322 pp. (in Turkish).

- Davis, T.; Blasco, D.; Carbonell, M. The Ramsar Convention manual: a guide to the Convention on wetlands (Ramsar, Iran, 1971);Convention on Wetlands of International Importance Especially as Waterfowl Habitat, Ramsar Convention Bureau.; IUCN: International Union for Conservation of Nature: Gland, Switzerland, 1997.

- Ramsar Convention Secretariat. An Introduction to the Convention on Wetlands (previously The Ramsar Convention Manual). Ramsar Convention Secretariat: Gland, Switzerland. 2016; pp. 107.

- Demirak, A.; Balcı, A.; Demirhan, H.; Tüfekçi, M. The reasons of the pollution in the Güllük Bay, in Proceedings of the 4th National Ecology and Environment Congress, 2001; pp. 383–388 (in Turkish).

- Demirak, A.; Balci, A.; Tüfekçi, M. Environmental impact of the marine aquaculture in Güllük Bay, Turkey. Environ Monit Assess. 2006, 123(1-3), 1-12.

- Yucel-Gier, G.; Pazi, I.; Kucuksezgin, F. Spatial analysis of fish farming in the Gulluk Bay (Eastern Aegean). Turk. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 2013, 13, 737–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MARA (Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs) Report, 1988. Research project of Gulluk Lagun. Institute of Fishery in Bodrum, Turkey, 1988, 41 pp (In Turkish).

- Tokaç, A., Ünal V., Tosunoğlu, Z., Akyol O., Özbilgin H., Gökçe G. Fisheries of Aegean Sea; IMEAK Deniz Ticaret Odası İzmir Şubesi Yayınları: İzmir, 2010; 371 pp. (in Turkish).

- Sağlam, C.; Akyol, O.; Ceyhan, T. Fisheries in Güllük Lagoon. Ege J Fish Aqua Sci. 2015, 32(3), 145–149. [Google Scholar]

- Altınsaçlı, S.; Perçin-Paçal, F.; Altınsaçlı, S.. Assessments on diversity, spatiotemporal distribution and ecology of the living ostracod species (Crustacea) in oligo-hypersaline coastal wetland of Bargilya (Milas, Muğla, Turkey). Int. J. Fish. Aquat. Stud. 2015, 3(2), 357-373.

- Cerim, H. Determination of some biological and population parameters of common sole (Solea solea Linnaeus, 1758) in Güllük Bay trammel net fishery. Doctoral dissertation, Muğla Sıtkı Koçman University, Muğla, Turkey, 2017 (in Turkish).

- IUCN. The IUCN Red List of threatened species. 2023, https://www.iucnredlist.org/ (accessed on 12 June 2023).

- Dawson, C.E. Syngnathidae. In Fishes of the North-eastern Atlantic and the Mediterranean, Whitehead, P.J.P., Bauchot, M.-L., Hureau, J.-C., Nielsen, J., Tortonese. E., Eds.; Unesco: Paris, 1986; Volume 2., p. 628-639.

- Smith-Vaniz, W.F. Syngnathus acus. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2015: E.T198765A44933898. Available online: 10.2305/\T1\iucn.uk.20154 (accessed on 12 June 2023).

- Pollom, R.. Syngnathus abaster. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2016: e.T21257A19423178. https://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-3.RLTS.T21257A19423178.en (accessed on 12 June 2023).

- Vasileva, E.D. Main alterations in ichthyofauna of the largest rivers of the northern coast of the Black Sea in the last 50 years: A review. Folia Zoo.a 2003, 52, 337–358. [Google Scholar]

- Monteiro, N.M.; Vieira, M.N. Rendez-vous at the Baltic? The ongoing dispersion of the black-striped pipefish, Syngnathus abaster. Oceanogr. Fish. Open Access J. 2017, 3, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Didenko, A.; Kruzhylina, S.; Gurbyk, A. Feeding patterns of the black-striped pipefish Syngnathus abaster in an invaded freshwater habitat. Environ. Biol. Fishes 2018, 101, 917–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cakić, P.M.; Lenhardt, D.; Mićkovıć, N.; Sekulıć, L.; Budakov, J. Biometric analysis of Syngnathus abaster populations. J. Fish Biol. 2002, 60, 1562–1569.

- Kolangi-Miandare, H.; Askari, G.; Fadakar1, D.; Aghilnegad, M.; Azizah, S. The biometric and cytochrome oxidase sub unit I (COI) gene sequence analysis of Syngnathus abaster (Teleostei: Syngnathidae) in Caspian Sea. Mol. Bio. Res. Commun. 2013, 2(4),133–142. [Google Scholar]

- Vieira, R.P.; Monteiro, P.; Ribeiro, J.; Bentes, L.; Oliveira, F.; Erzini, K.; Gonçalves, J.M.S. Length-weight relationships of six syngnathid species from Ria Formosa, SW Iberian coast. Cah. Biol. Mar. 2014, 55, 9–12. [Google Scholar]

- Yildiz, T.; Uzer, U.; Firdes Saadet, K. Preliminary report of a biometric analysis of greater pipefish Syngnathus acus Linnaeus, 1758 for the western Black Sea. Turk. J. Zool. 2015. 39(5), 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurkan, S.; Innal, D. Some morphometric features of congeneric pipefish species (Syngnathus abaster Risso 1826, Syngnathus acus Linnaeus, 1758) distributed in Lake Bafa (Turkey). Oceanol. Hydrobiol. Stud. 2018, 47(3), 239–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawson, C.E. Syngnathidae. InFishes of the north-eastern Atlantic and the Mediterranean, Whitehead, P.J.P. Ed.; Unesco, Paris, France, 1986;, pp. 628-639.

- Planas, M.; Piñeiro-Corbeira, C.; Bouza, C.; Castejón-Silvo, I.; Vera, M.; Regueira, M.; Ochoa, V.; Bárbara, I.; Terrados, J.; Chamorro, A.; et al. A multidisciplinary approach to identify priority areas for the monitoring of a vulnerable family of fishes in Spanish Marine National Parks. BMC Ecol. Evol. 2021, 21, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, K.; Monteiro, N.M.; Almada, V.C.; Vieira, M.N. Early life history of Syngnathus abaster (Pisces: syngnathidae). J. Fish Biol. 2006, 68, 80–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Planas, M. Ecological traits and trophic plasticity in the greater pipefish Syngnathus acus in the NW Iberian Peninsula. Biology 2022, 11(5), 712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, K,; Monteiro, N. M.; Vieira, M.N.; Almada, V.C. Reproductive behaviour of the black-striped pipefish, Syngnathus abaster (Pisces; Syngnathidae). J. Fish Biol. 2006, 69, 1860–1869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franzoi, P.R.; Maccagnani, R.R.; Ceccherelli, V.U. Life cycles and feeding habits of Syngnathus taenionotus and Syngnathus abaster (Pisces, Syngnathidae) in brackish bay of the Po River delta (Adriatic Sea). Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 1993, 97, 71–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vizzini, S.; Mazzola, A. The structure of pipefish community (Pisces: Synganthidae) from a western Mediterranean sea grass meadow based on stable isotope analysis. Estuaries 2004, 27(2), 325–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kendrick, A.J.; Hydnes, G.A. Variations in the dietary compositions of morphologically diverse syngnathid fishes. Environ. Biol. Fish., 2005, 72, 415–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taşkavak, E.; Gürkan, Ş.; Severa, T.M.; Akalına, S.; Özaydına, O. Gut contents and feeding habits of the great pipefish, Syngnathus acus Linnaeus, 1758, in Izmir Bay (Aegean Sea, Turkey). Zool. Middle East 2010, 50, 75–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurkan, Ş.; Innal, D.; Gulle, I. Monitoring of the trophic ecology of pipefish species (Syngnathus abaster, Syngnathus acus) in an alluvial lake habitat (Lake Bafa, Turkey). Oceanol. Hydrobiol. Stud. 2021, 50, 24–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manning, C.G.; Foster, S.J.; Vincent, A.C.J. A review of the diets and feeding behaviours of a family of biologically diverse marine fishes (Family Syngnathidae). Rev. Fish Biol. Fisheries 2019, 29, 197–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MEF, 2011. General Directory of Nature Protection and National Parks. http://gis2.cevreorman.gov.tr/mp/ (accessed 2 June 2023). 2 June.

- Tomasini, J.A.; Quignard, P.; Capapé, C.; Bouchereau, L. Facteurs du succès reproductif de Syngnathus abaster Risso, 1826 (Pisces, Teleostei, Syngnathidae) en milieu lagunaire méditerranéen (lagune de Mauguio, France). Acta Oecol. 1991, 12, 331–355. [Google Scholar]

- Vincent, A.; Berglund, A.; Ahnesjö, I. Reproductive ecology of five pipefish species in one eelgrass meadow. Environ. Biol. Fish 1995, 44, 347–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riccato, F.; Fiorin, R.; Franco, A.; et al. Population structure and reproduction of three pipefish species (Teleostei, Syngnathidae) in a seagrass meadow of the Venice lagoon. Biol. Mar. Medit. 2003, 10, 138–145. [Google Scholar]

- Liao, H.; Pierce, C.L.; Larscheid, J.G. Empirical assessment of indices of prey importance in the diets of predacious fish. T. Am. Fısh Soc. 2001, 130, 583–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinnegar, J.K.; Polunin, N.V.C. Differential fractionation of δ13C and δ15N among fish tissues: implications for the study of trophic interactions. Funct. Ecol. 1999, 13, 225–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sotiropoulos, M.A.; Tonn, W.M.; Wassenaar, L.I. Effects of lipid extraction on stable carbon and nitrogen isotope analyses of fish tissues: potential consequences for food web studies. Ecol. Freshw. Fish 2004, 13, 155–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweeting, C.J.; Polunin, N.V.C.; Jennings, S. Effects of chemical lipid extraction and arithmetic lipid correction on stable isotope ratios of fish tissues. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 2006, 20, 595–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Post, D.M.; Layman, C.A.; Arrington, D.A.; Takimoto, G.; Quattrochi, J.; Montaña, C.G. Getting to the fat of the matter: models, methods and assumptions for dealing with lipids in stable isotope analyses. Oecol. 2007, 152, 179–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logan, J.M.; Jardine, T.D.; Miller, T.J.; Bunn, S.E.; Cunjak, R.A.; Lutcavage, M.E. Lipid corrections in carbon and nitrogen stable isotope analyses: comparison of chemical extraction and modelling methods. J. Anim. Ecol. 2008, 77, 838–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valladares, S.; Planas, M. Non-lethal dorsal fin sampling for stable isotope analysis in seahorses. Aquat. Ecol. 2012, 46, 363–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Planas, M.; Paltrinieri, A.; Carneiro, M.D.D.; Hernández-Urcera, J. Effects of tissue preservation on carbon and nitrogen stable isotope signatures in Syngnathid fishes and prey. Anim. 2020, 10, 2301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- R Core Team. The R Project for Statistical Computing. Available online: http://www.R-project.org (accessed on 23 April 2020).

- R Core Team. Stats: The R stats package. Available online: https:// https://www.rdocumentation.org/packages/stats/versions/3.6.2 (accessed on 23 February 2018).

- Le Cren, E.D. The length-weight relationship and seasonal cycle in gonad weight and condition in the Perch (Perca fluviatilis). J. Ani. Ecol., 1951, 20, 201–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricker, W.E.; Carter, N.M. Handbook of computations for biological statistics of fish populations, No. 119. The Fisheries Research Board of Canada, Queen’s printer and controller of stationary: Ottawa, 1958.

- Jackson, A. L.; Inger, R.; Parnell, A. C.; Bearhop, S. Comparing isotopic niche widths among and within communities: SIBER – Stable isotope Bayesian ellipses in R. J. Anim. Ecol. 2011, 80, 595–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lysy, M.; Stasko, A.D.; Swanson, H.K. nicheROVER: (Niche) (R)egion and Niche(Over)lap metrics for multidimensional ecological niches. R package version 1.1.0. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=nicheROVER (accessed 17 September 2019). 17 September.

- Swanson, H.K.; Lysy, M.; Power, M.; Stasko, A.D.; Johnson, J.D.; Reist, J.D. A new probabilistic method for quantifying n-dimensional ecological niches and niche overlap. Ecol. 2015, 96, 318–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wickham, H.; Chang, W. Create elegant data visualisations using the grammar of graphics. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=ggplot2 (accessed 17 September 2019). 17 September.

- Veiga, P.; Machado, D.; Almeida, C.; Bentes, L.; Monteiro, P.; Oliveira, F.; Ruano, M.; Erzini, K.; Gonçalves, J.M.S. Weight-length relationships for 54 species of the Arade estuary, southern Portugal. J. Appl. Ichthyol. 2009, 25, 493–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gürkan, Ş.; Taşkavak, E.; Hoşsucu, B. The reproductive biology of the Great Pipefish Syngnathus acus (Family: Syngnathidae) in the Aegean Sea. North˗West J. Zool. 2009, 5(1), 179˗190.

- Simal Rodríguez, A.; Grau, A.; Castro-Fernández, J.; et al. Reproductive biology of pipefish Syngnathus typhle and S. abaster (Syngnathidae) from Western Mediterranean Sea. J. Ichthyol. 2021, 61, 608–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liousia, V. Study on the biology of the syngnathidae family in Greece. PhD Thesis, Dissertation, University of Ioannina, Greece, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Fritzsche, R. A. Revision of the Eastern Pacific Syngnathidae (Pisces: Syngnathiformes), including both recent and fossil forms. Proceedings of the California Academy of Sciences, San Francisco, USA, 1980; 42, 181–227.

- Garcia, E.; Rice, C.A.; Eernisse, D.J.; Forsgren, K.L.; Quimbayo, J.P.; Rouse, G.W. Systematic relationships of sympatric pipefishes (Syngnathus spp.): A mismatch between morphological and molecular variation. J. Fish Biol. 2019, 95(4), 999–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chunco, A.J.; Jobe, T.; Pfennig, K.S. Why do species co-occur? A test of alternative hypotheses describing abiotic differences in sympatry versus allopatry using spadefoot toads. PLoS One 2012. 7(3), e32748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seehausen, O.; van Alphen, J.J.M.; Witte, F. Cichlid fish diversity threatened by eutrophication that curbs sexual selection. Sci. 1977, 277, 1808–1811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundin, J.; Aronsen, T.; Rosenqvist, G. et al. Sex in murky waters: algal-induced turbidity increases sexual selection in pipefish. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 2017, 71-78.

- Wilson, A. B. Interspecies mating in sympatric species of Syngnathus pipefish. Mol. Ecol. 2006, 15, 809–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moser, F.N.; Wilson, A.B. Reproductive isolation following hybrid speciation in Mediterranean pipefish (Syngnathus spp.). Anim. Behav. 2020, 161, 77–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piñeiro-Corbeira, C.; Iglesias, L.; Nogueira, R.; Campos, S.; Jiménez, A.; Regueira, M.; Barreiro, R.; Planas, M. Structure and trophic niches in mobile epifauna assemblages associated with seaweeds and habitats of syngnathid fishes in Cíes Archipelago (Atlantic Islands Marine National Park, NW Iberia). Front. Mar. Sci. 2021, 8, 773367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tieszen, L.L.; Boutton, T.W.; Tesdahl, K.G.; Slade, N.A. Fractionation and turnover of stable carbon isotopes in animal tissues: implications for δ13C analysis of diet. Oecol. 1983, 57, 32–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fry, B. Food web structure on Georges Bank from stable C, N and S isotopic compositions. Limnol. Oceanogr. 1988, 33, 1182–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobson, K. A.; Ambrose, Jr. W. G.; Renaud, P. E. Sources of primary production, benthic-pelagic coupling, and trophic relationships within the Northeast Water Polynya: insights from δ13C and δ15N analysis. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 1995, 128, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Lussanet Marc, H.E; Muller, M. The smaller your mouth, the longer your snout: predicting the snout length of Syngnathus acus, Centriscus scutatus and other pipette feeders. J. R. Soc. Interface. 2007, 4561–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Killi, N. Spatio-temporal variation in the distribution and abundance of marine cladocerans in relation to environmental factors in a productive lagoon (Güllük Bay, SW Aegean Sea, Turkey)" Oceanol. Hydrobiol. Stud. 2020, 49(4), 374–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boix, D.; Gascón, S.; Sala, J.; Martinoy, M.; Gifre, J.; Quintana, X.D. A new index of water quality assessment in Mediterranean wetlands based on crustacean and insect assemblages: the case of Catalunya (NE Iberian Peninsula). Aquatic Conserv. Mar. Freshw. Ecosyst. 2005, 15, 635–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brucet, S.; Compte, J.; Boix, D.; López-Flores, R.; Quintana, X. D. Feeding of nauplii, copepodites and adults of Calanipeda aquaedulcis (Calanoida) in Mediterranean salt marshes. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2008, 355, 183–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazareva, V.I. The Mediterranean copepod Calanipeda aquaedulcis Kritschagin, 1873 (Crustacea, Calanoida) in the Volga River reservoirs. Inland Water Biol. 2018, 11(3), 303–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uriarte, I.; Villate, F.; Iriarte, A. Zooplankton recolonization of the inner estuary of Bilbao: influence of pollution abatement, climate and non-indigenous species. J. Plankton Res. 2016, 38(3), 718–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Planas, M. Was that my meal? Uncertainty from source sampling period in diet reconstruction based on stable isotopes in a syngnathid fish. Front. Mar. Sci. 2022, 9, 982883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurkan, Ş.; Taşkavak, E. The relationships between gut length and prey preference of three pipefish (Syngnathus acus, Syngnathus typhle, Nerophis ophidion Linnaeus, 1758) species distributed in Aegean Sea, Turkey. Iran. J. Fish. Sci. 2019, 18, 1093–1100. [Google Scholar]

- Tipton, K.; Bell, S.S. Foraging patterns of two syngnathid fishes: importance of harpacticoid copepods. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 1988, 47, 31–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, F.; Erzini, K.; Gonçalves, J.M.S. Feeding habits of the deep-snouted pipefish Syngnathus typhle in a temperate coastal lagoon. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2007, 72, 337–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, J.J.; Carpenter, S.R.; Kitchell, J.; Weidel, B. Strong evidence for terrestrial support of zooplankton in small lakes based on stable isotopes of carbon, nitrogen, and hydrogen. Biol. Sci. 2020, 108(5), 1975–1980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Planas, M.; Chamorro, A.; Paltrinieri, A.; Campos, S.; Nedelec, K.; Hernández-Urcera, J. Effect of diet on breeders and inheritance in Syngnathids: Application of isotopic experimentally derived data to field studies. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2020, 650, 107–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayol, J.; Grau, A.; Riera, F.; Oliver, J. Llista vermella dels peixos de les Balears; Conselleria de Medi Ambient-Conselleria d’Agricultura i Pesca, Palma de Mallorca, España, 2000.

- Manent Sintes, P.; Abella-Gutiérrez, J. Aspectos ecológicos y biológicos de Syngnathus abaster (Risso, 1826) en la bahía de Fornells. Revista de Menorca 2004, 88, 89–105. [Google Scholar]

- Quezada-Romegialli, C.; Jackson, A. L.; Hayden, B.; Kahilainen, K. K.; Lopes, C.; Harrod, C. tRophicPosition, an R package for the Bayesian estimation of trophic position from consumer stable isotope ratios. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2018, 9, 1592–1599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Total length (cm) | Wet weight (g) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Species | Sex condition | n | Mean | sd | Max | Min | Mean | sd | Max | Min |

| Syngnathus abaster | Pooled | 51 | 5.9 | 1.6 | 10.9 | 3.3 | 0.115 | 0.128 | 0.669 | 0.015 |

| Undifferentiated | 37 | 5.2 | 0.7 | 6.6 | 3.3 | 0.058 | 0.023 | 0.119 | 0.015 | |

| Male | 7 | 8.8 | 1.0 | 10.9 | 7.7 | 0.358 | 0.155 | 0.669 | 0.230 | |

| Female | 7 | 7.2 | 1.5 | 10.0 | 5.4 | 0.168 | 0.134 | 0.450 | 0.069 | |

| Syngnathus acus | Pooled | 78 | 6.3 | 1.9 | 12.0 | 3.1 | 0.124 | 0.125 | 0.610 | 0.010 |

| Undifferentiated | 45 | 5.0 | 0.9 | 6.4 | 3.1 | 0.051 | 0.025 | 0.096 | 0.010 | |

| Male | 9 | 8.4 | 1.9 | 12.0 | 6.3 | 0-272 | 0.154 | 0.470 | 0.098 | |

| Female | 24 | 7.8 | 1.4 | 11.6 | 6.1 | 0.206 | 0.130 | 0.610 | 0.095 | |

| Species | n | a | b | se b | CI b | R2 | p | t-test p | Growth type |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Syngnathus abaster | 51 | 0.000294 | 3.179 | 0.095 | 2.989 – 3.369 | 0.958 | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 | Allometric (+) |

| Syngnathus acus | 78 | 0.000269 | 3.182 | 0.057 | 3.069 – 3.296 | 0.976 | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 | Allometric (+) |

| S. abaster | S. acus | S. abaster | S. acus | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pooled | Pooled | Spring | Summer | Spring | Summer | |||||||

| Prey Groups | %F | %N | %F | %N | %F | %N | %F | %N | %F | %N | %F | %N |

| Copepoda | ||||||||||||

| Halicyclops biscupidatus | n.d. | n.d. | 1.2 | 0.2 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | 1.0 | 54.2 |

| Calanipeda aquaedulcis | 42.6 | 71.8 | 35.3 | 47.5 | 37.0 | 70.5 | 47.3 | 75.5 | 87.7 | 44.9 | 53.6 | 53.6 |

| Other copepods | 37.7 | 15.5 | 11.8 | 4.7 | 73.0 | 29.6 | 18.9 | 10.2 | 5.2 | 4.1 | 6.2 | 6.3 |

| Cladocera | ||||||||||||

| Daphnia longispina | n.d. | n.d. | 3.5 | 0.6 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | 0.6 | 0.5 | 1.0 | 0.7 |

| Ceriodaphnia quadrangula | n.d. | n.d. | 1.2 | 0.2 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Pleopis polyphemoides | n.d. | n.d. | 2.3 | 0.4 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | 0.6 | 0.3 | 1.0 | 0.7 |

| Cladocera pieces | n.d. | n.d. | 40.0 | 45.7 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | 4.5 | 49.6 | 35.0 | 35.9 |

| Insecta | n.d. | n.d. | 1.2 | 0.2 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | 0.6 | 0.3 | n.d. | 0.7 |

| Mollusca | n.d. | n.d. | 1.2 | 0.2 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | 1.0 | n.d. |

| Fish scale | 4.9 | 0.7 | 1.2 | 0.2 | 7.4 | 0.5 | 1.3 | 1.4 | 0.6 | 0.3 | n.d. | 0.7 |

| Unidentified eggs | 14.7 | 12.0 | n.d. | n.d. | 25.9 | 11.7 | 32.4 | 12.9 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. |

| δ13C ‰ | δ15N ‰ | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Species | Sex condition | n | Mean | sd | Max | Min | Mean | sd | Max | Min |

| Syngnathus abaster | Pooled | 51 | -17.0 | 1.2 | -14.4 | -19.8 | 13.2 | 0.6 | 14.7 | 11.4 |

| Undifferentiated | 37 | -17.0 | 1.2 | -14.4 | -19.8 | 13.4 | 0.5 | 14.7 | 12.6 | |

| Male | 7 | -17.6 | 1.2 | -16.4 | -19.6 | 12.8 | 0.9 | 13.9 | 11.4 | |

| Female | 7 | -16.6 | 0.9 | -15.4 | -17.8 | 12.9 | 0.6 | 13.4 | 11.6 | |

| Syngnathus acus | Pooled | 75 | -17.3 | 1.2 | -14.9 | -20.5 | 13.3 | 0.7 | 15.2 | 11.6 |

| Undifferentiated | 43 | -17.1 | 1.2 | -15.0 | -22.1 | 13.4 | 0.6 | 14.8 | 12.2 | |

| Male | 8 | -17.6 | 1.6 | -16.3 | -21.4 | 13.4 | 0.6 | 14.8 | 12.2 | |

| Female | 24 | -17.6 | 1.1 | -16.3 | -19.0 | 13.1 | 0.8 | 15.2 | 11.6 | |

| Syngnathus abaster | Syngnathus acus | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Metrics | Undifferentiated | Males | Females | Undifferentiated | Males | Females |

| TA | 6.65 | 2.19 | 1.60 | 8.79 | 4.11 | 7.98 |

| SEA | 1.66 | 1.69 | 1.06 | 2.11 | 2.87 | 2.05 |

| SEAc | 1.70 | 2.03 | 1.28 | 2.16 | 3.35 | 2.14 |

| S. abaster | S. acus | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Species | Sex condition | Female | Male | Undif. | Female | Male | Undif. |

| Syngnathus abaster | Female | - | 51 | 85 | 94 | 88 | 90 |

| Male | 34 | - | 58 | 87 | 86 | 71 | |

| Undifferentiated | 59 | 40 | - | 77 | 81 | 95 | |

| Syngnathus acus | Female | 53 | 70 | 74 | - | 87 | 82 |

| Male | 44 | 59 | 65 | 78 | - | 76 | |

| Undifferentiated | 52 | 40 | 86 | 73 | 80 | - | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).