1. Introduction

Artificial Intelligence of Things integrated (AIoT) Electronic Health Record (EHR) system is an extensive real-time digital patient-centered health record accessible from many different interoperable automated systems and available instantly and securely to authorized users through standardized Health Information data format, which supports system functions [

1]. Healthcare facilities using EHR systems face enormous and persistent cybersecurity attacks that challenge the integrity of critical EHR infrastructure with dire consequences to patient privacy, patient safety, and risk to an organization’s finances or reputation. As such, confidentiality, integrity, and availability of the EHR system are very crucial, as health providers need to be able to make life or death decisions by recording accurate patient hospital-related activities, including but not limited to diagnosis, personally identifying information (PII), and demographic information [

1]. The 2019 National Electronic Record survey shows that approximately 89% of USA office-based physicians use EHRs [

2]. In addition, over 90% of large, medium, small rural, and critical access hospitals use some form of EHRs [

2]. There are four core EHR uses, with increasing subs uses as research and development in technology continue to grow. The four uses include providing healthcare practitioners with history and a potential projected view on patients’ health; Aiding healthcare practitioners in enhancing the quality of patient care and efficiency in care by providing access to current health state concerning disease, medication history, medical exams records, from a central location; Reducing the cost of care by removing redundancy in procedures, reducing errors (i.e. such as wrong prescription and drug interactions); and Serving as a memory bank for practitioners and patients in understanding previous ailments and care [

3].

Such core functionalities make EHR systems an essential part of any Healthcare Information Technology infrastructure, requiring every measure to guarantee that sensitive patient information such as PII, medical history, diagnosis, medications, treatment plans, immunization dates, allergies, radiology images, laboratory and test results are protected against any adverse threat (either internally or externally). For example, PII collected by a Health custodian during a patient visit, if not safeguarded and subjected to a data breach, can result in identity theft with severe consequences (i.e., impersonation attacks and fraud). Although there is many definitions of what constitutes data breach, for the purpose of this work, data breach limited to any unauthorize access to patients PII, demographic data, diagnose data, or other EHR system data that compromise confidentiality of patient or system information.

Unfortunately, there are documented challenges [

1,

48] in designing and securing EHR systems, including but not limited to how to adequately address security and privacy control requirements for secure collection, retention, and use of available data . Other difficulties include but are not restricted to protecting data in multiple states ( transit, storage, or process); Protecting infrastructure supporting EHR; Access control provisioning to online EHR resources to prevent data breaches; Determining the authenticity of an individual during enrollment into the EHR before granting access, privileges, credentials, and services; Secure access to other stakeholders to connect to the EHR and how to protect stakeholder’s sensitive data; and Education to consumers, providers, employees the importance of protecting data and somehow introducing an incentive [

4].

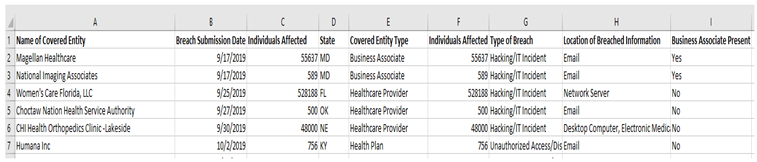

In the past, such challenges have resulted in successful data breaches against some key organization EHRs. As documented in

Table 1, several Healthcare facilities across the globe have suffered data breaches . Such Cyber attacks indicate that security measures employed to secure EHRs in most jurisdictions might be subpar and require measured security control and aggressive solutions to address security vulnerabilities that can lead to a successful data breach for EHRs.

As Healthcare data breaches become omnipresent, as depicted in

Table 1, most patients continuously lose confidence in the security and protection of their health records [

48]. Therefore, they are uncomfortable providing information or interest in the fully participating EHR system [

11]. Patients' trust and confidence that Healthcare providers are protecting their private and sensitive information at all costs have dwindled. In a recent global survey, approximately 80% of Americans, 81% of Britons, and 83% of Australians had strong reservations about allowing their paper health record to be migrated into the EHR system because of the risk of identity theft, the possibility of privacy breaches, intrusive privacy violation by nosy healthcare workers, or other employers [

11]. Most participants from the survey acknowledge a high risk of exposure to privacy threats while their medical records are managed by healthcare organizations [

11]. Keeping EHR secure is a challenge that government and healthcare providers around the globe are beginning to grasp in its infancy [

23].

In addressing the research question, “Does current EHR implementation lack the requisite security control to prevent a cyber breach and protect user privacy?” Based on current literature and preliminary work, we hypothesize that:

H0: Most EHR implementations lack sufficient security controls to guarantee patient privacy, safety, and hospital operation continuity during a Cyberattack.

H1: Most EHR cybersecurity attacks are concentrated using similar attack methodologies and face common vulnerabilities.

In addressing our stated research question and testing our hypothesis, we assess the current solutions in the literature and conduct an exploratory study on existing HIPAA data breaches between 2010 - 2022. Based on our findings, we make the two important contributions: First, this work provides detailed analysis of current health data breaches to demonstrate common modes of attacks highly breach area assets within the EHR infrastructure, allowing health entities to invest in solutions that focus on identified areas. Second, a descriptive and trend analysis to describe, demonstrate, summarize data points, and predict the direction of EHR data breaches based on current and historical data by a covered entity for other researchers to build on our work.

The rest of this work is divided into section 2, background and motivation, addressing why EHR security privacy should be of great concern.

Section 3 discusses related work.

Section 4 presents the methodology.

Section 5 presents results, analysis, and discussions.

Section 6 focuses on the discussion and conclusion.

2. Background

The current landscape of EHR system security, privacy, and related safety concerns continues to be critical issues attracting attention in mainstream media as health entities continue to suffer from Cyberattacks. To develop a firm grasp of the security and privacy requirements, we review the background and current EHR security landscape, including but not limited to the following:

2.1. Overview “EHR System & Security Requirement:

Most advanced countries, such as Canada and the United States, have accepted the importance and significantly benefited from establishing health infrastructure [

2]. However, although there are many EHR benefits, complex cybersecurity issues must be resolved to provide privacy and security assurance to stakeholders. Some security issues result from the varied size of EHR data repository and complexity and the designated strategies of protecting access, securing data and systems, providing the proper access control, and securing physical infrastructure[

47]. For example, the universal healthcare system in Canada is homogenous and involves millions of interactions between patients and healthcare professionals. This usually results in over “3.5 million hospital discharges from general and allied special hospitals; over 800 hospitals, some 123000 in-patient beds; More than 28, 000 general practitioners and 27 000 medical specialists; Approximately 230000 registered nurses in adding to nursing assistants; and More than 9000 pharmacists, 6000 occupational therapists and 9,000 physiotherapists” [

1].

Figure 1 below shows such multiple data sources and possible interactions that can occur within an EHR system and, therefore, require meticulous security controls to protect such complex interactions.

The security of an EHR system must begin from project initiation [

12]. It must incorporate EHR system policy application, access control design, data collection security, data transmission, storage security, application security, infrastructure security, and patient privacy. In addition, an adequately secure EHR system should satisfy the following security principles:

Confidentiality: The patient record during the collection, storage, and access stages must be private and confidential so that no unauthorized person or entity may be able to inspect the content of the patient record [

3].

Integrity: Good data integrity must be defined so that only authorized persons can modify patient records, and proper auditing is put in place to enforce nonrepudiation. A data integrity policy must be implemented and enforced since a patient’s previous record is paramount to their care [

3].

Availability: Necessary care ensuring systems are robust and redundant is taken. First, it must be guaranteed that EHR systems are available anytime, any day. Second, the EHR system must have close to 0% downtime due to its critical role during patient care. Third, all necessary efforts must be implemented to defend against attacks such as Denial of Service, Distributed Denial of Service, and others. Lastly, the hosting server must have the redundant capability to accommodate hardware failure and ensure healthcare providers have continuous access to health records [

3].

Other fundamental EHR security principles must be critically analyzed to address shortfalls in maintaining the security of EHR systems and data. Such principles are required to provide holistic EHR security integration to address systems components and interactions ranging from the issue of data classification, data ownership, data confidentiality, data access, data integrity, and data maintenance requirements in EHR systems [

20]. These principles must be closely monitored to provide optimum data security for various data states(e.g storage, transit, etc) within any EHR system or any user interaction with data within the EHR system.

2.2. General Background about AIoT

Artificial intelligence (AI) coupled with Internet of Things technologies is increasingly being deployed in various industries as a double-edged sword regarding user privacy[

46]. There is a myriad of advantages and likewise opposing disadvantages. However, within the context of breach management and Compliance, AIoT can be leveraged in many positive avenues, including deployment of my conceptual model that allows organizations to automate reporting to HIPAA data breaches, thereby optimizing efficiency on decisions, performing routine tasks, currency of new attacks, and up to date data sharing of attack strategies. The major leverage of AIoT is to change the trajectory of Compliance by automating health data breach tasks currently performed manually, such as reporting health data breaches.

In today’s world, it’s imperative to understand the exponential growth of AIoT (Artificial Intelligence of Things). AIoT is a combination of AI and IoT. AI focuses on programs doing specific tasks requiring human thinking and having a supporting computational power[

44]. IoT leverages interconnected devices that act individually or collectively[

44] within the EHR environment.

2.3. Data Ownership

There is fierce debate on the ownership of data in Healthcare in various jurisdictions [

34]. The ownership of information on patient activities, such as prescriptions taken and diagnoses at hospitals, is a complex issue in many jurisdictions worldwide [

15]. Healthcare data ownership is inconsistent globally compared to other fields, such as banking. The data collected, such as transactions on credit cards and spending behavior, is clearly defined as directly owned by the bank that issued the credit card [

17]. Although patient records can be similar to information collected by financial institutions, there is consistent complexity in defining Information owner when the law, medicine, and technology (electronic) intersect [

16]. For example, in 1992, Canada’s Supreme Court, in a case dealing with this complex issue regarding a patient's medical record ownership, set ownership to primarily physicians of health records, with only the patients have access rights to them [Quiet, unfortunately, such a comparison view of electronic data ownership and hard copy ownership introduces challenges considering that electronic records deal with the elusive nature of information (data existing on multiple mediums at the same time), blurring of public and private spaces, and actual physical security [

18]. In the past, such a definition of data ownership and security responsibility was based on much speculation and points to the fact that EHR data cannot be monetized. Further, such thinking has led hospitals or healthcare providers not to take all necessary to protect EHR [

14].

Further, for countries that enjoy publicly funded Healthcare (e.g., Canada or the UK), providers do not have to deal with losing clientele due to electronic health data breaches. First, this results from the fact that most Universal Healthcare is based on jurisdiction. This means that regardless of how poorly a hospital protects patient health records. Patients have no option but to attend the same hospital if it is the closest provider to their home address. Secondly, funding is not directed to several patients seen in such jurisdiction but rather a complex and intertwined aggregate. Finally, there is not much financial loss to hospitals that disregard protecting patients electronically [

20]. For example, in the province of Ontario, Canada, “funding is based primarily on a principle of global (or base) funding where a set budget is provided to each hospital annually” [

20].

To address the issue of who owns data in a secure EHR, the designer must clearly define data ownership and assign data accountability to the owner. This means either through legislation or internal EHR information protection policy. There must be a way to trace any issues regarding data breaches to the data owner and investigate to ensure that prudent security measures are in place. In a nutshell, implementing punitive measures can easily act as a catalyst to ensure that hospitals (data owners) of EHR data continuously invest in the security of patient data. With this said, any established data-sharing agreement should not impede a health professional’s ability to comply with the obligations regarding medical records in performing their responsibilities or access such records and, where required, transition the data to another service. The healthcare provider should ensure that health professionals comply with their obligations to secure patient data, irrespective of any nuisances that may affect the EHR system [

13]. Therefore, the data-sharing agreement should focus on looking for avenues where the health professional has only required access to PHI but at the same time can provide access to patients requiring access to the PHI without having to burden the health professional’s ability to conduct his core responsibility patient care within the EHR.

2.4. Confidentiality and Privacy of Data

Providing confidentiality for data and patient privacy is complex and involves several moving parts that must be synchronized. These include but are not limited to employee training on confidentiality, tools and a measure to ensure confidentiality, and information security policies to enforce the behavior of information owners and ensure confidentiality. The confidentiality and privacy of EHR records can range from a curious healthcare worker trying to snoop on a new boyfriend’s health record to a more severe breach of patient privacy, including illegal access to patient records through an adversary. The confidentiality principle within EHR is essential, as it ensures compliance initiatives established by health or related patient privacy laws. However, confidentiality and privacy principles can be daunting as they are intertwined with human factors or error-prone processes. Human factors can contribute to undesirable failures ranging from lack of training and understanding of confidentiality by healthcare workers. The lack of adequate measures to ensure employee access is properly logged to establish accountability of access records is essential. Also, there are no adequate punitive measures on information security policy violations by employees to deter preventable errors such as copying and transferring unencrypted data, and inadequate technological solutions to provide automatic safeguards to deal with minimal human errors [

21]. It is imperative to note that confidentiality issues such as unauthorized disclosure may harm reputation, credibility, privacy, or regulatory Compliance with the health system.

In dealing with the human factors that negatively affect data security in any EHR deployment, the Healthcare organization must develop an end-to-end personnel practice starting from job posting, hiring, training, and background checks. Therefore, much emphasis must be placed on employees' training and development. In reference to the employee training, we are not limiting it to employees or stakeholders who directly interact with the EHR but rather expanding the scope of employees to include janitors, hospital aides, and others who have physical access to the EHR system or through login. In addition, we must understand that intentional breaches of an EHR system can be done through social engineering attacks, where any hospital employee can be a point of contact. Social engineering attacks involve deceiving people into breaching their security practices and allowing unauthorized access to their network, and the success of professional hackers sometimes depends on such human error [

21]. For example, for “eleven months, Frank Abagnale impersonated a Chief Resident Pediatrician in a Georgia hospital under the alias Frank Conners” [

22]. He gained access to this role and the health records of Georgia Hospital after becoming a friend’s doctor, his neighbor. However, without a proper background check, he was subsequently offered a temporary Supervisor of Resident interns’ position after tricking the real doctor into thinking he was qualified [

22].

3. Related Work

3.1. EHR System Security and Data Breaches

We present current research on the privacy and security of EHR system and provides details on unique research work that significantly contributes to privacy and security-related patient data issues. To date, various proposed architectural designs have either run short of required security principles or missed the details with the necessary and critical data protection schemes required for protecting EHR systems in storage, processing, or transit. Most solutions proposed a data security framework, which is not fully inclusive through the EHR system development life cycle and implementation. Several works [23, 24,25,26, 27, 28] have looked at EHR security and privacy challenges, but currently, a limited number of works focus on defining a holistic solution. Most of these author proposed work that lack consideration of security at the forefront of development of deployment. Rather in most of these works cited most EHR system development, security and privacy integration are an afterthought, fragmented, and improperly thought through [

23,

25]. Most of the published materials or recently deployed EHR system within Canada and the United States does not provide or recommend solutions that can address the issue of data security concerning design, implementation, and the entire system life cycle. Current works do not fully address patient privacy compliance requirements and issues surrounding developing stakeholder training or cybersecurity policies.

The current Electronic Health Record infrastructure (EHR) Privacy and Security conceptual architecture” [

29] proposes privacy and security conceptual architecture”. It takes a stab at a framework that mitigates patient data breaches in an EHR system. Their work focuses on the business and technical architecture for interoperable EHR systems. The conceptual architecture only illustrates high-level services, data storehouses, and data presented within the enterprise. The author's [

29] blueprint focuses on interoperability within the systems but does not focus and lacks requisite security principles in the architecture. This work [

29] fell short in addressing direct patient data privacy compliance challenges to regulations such as PHIPA or HIPPA. The authors [

29] fail to propose solutions to the technical specificities required to provide data security within any EHR system. The proposed framework and recommendations did not adequately address unique data security within the EHR system. This does not include several services necessary to ensure the privacy and security of Personal Health Information (PHI) stored or accessed by EHR system users. For this work, a more functional design or model of EHR security architecture is necessary to focus on making security a key component of all interactions within an EHR system. The emphasis of their architecture should not just strictly focus on the interoperability of the various key services and their functionalities but rather incorporate the security of those services and all other interactions between the services. Although the authors proposed conceptual architecture as a roadmap for designing and implementing common services within EHR, security integration is required at the grassroots level.

Several other research works are looking at ways to protect data within EHR [

1,

3,

23,

29]. For example, a recent work published by Camps et al. [

3], “Security Requirements for a Lifelong Electronic Health Record System: An Opinion,” describes the security requirements for EHR and emphasizes the principles of confidentiality, integrity, and legal value. The authors' [

3] work compared localized patient health records (PHR) and centralized EHR. The authors [

3] looked at the various security principles required for both systems to provide health data protection and access vulnerabilities and essential security requirements needed to implement EHR and proposed fourteen principles for securing EHR [

3]. Although the authors' [

3] work provided good contributions in addressing EHR security, their work has a research gap by narrowly focused on integrity and legal guidelines. The second gap is that the authors[

3] did not offer substantial technical details to potentially make a significant difference in solving the problem, leaving out some critical administrative controls such as policies and technical controls.

The authors [

1], in their review of some of the other works, provided a better blanket support EHR system developed in the USA. Upon a close look at that system reviewed by the authors [

1], it was immediately apparent that there was no focus on integrating data security within EHR. In a nutshell, their EHR development only focused on eight identifiable critical activities [

1]. Similarly, the “Data Breach Battle” survey [

11] conducted by SailPoint Market Pulse of adults in the United States, Great Britain, and Australia evaluated the impact of security breaches from the consumer perspective. The authors [

11] provided several statistics regarding users' Electronic Health Record security concerns. It provided critical statistical information on the seriousness of this issue for ordinary citizens.

Regarding the problem discussed within the article, the authors focused on users' high-level concerns and did not dig deep to discover the burden and legal liability that can be put on governments in countries with Universal healthcare systems like Canada and Great Britain. The authors pinpoint direct causation to an average everyday taxpayer within any Universal Health system and show how such data breaches within an EHR affect their pocketbook. Citizens must understand the trickledown effect of legal liability that can be brought against the government when EHR data is continuously breached.

Young et al.'s [

23] research on “Electronic Health Records-Privacy and Security issue” discusses the benefits of EHR to patient care and the challenges EHR poses to all stakeholders. The authors [

23] describe several characteristics of EHR and question current privacy laws' ability to address strong enough measures to protect EHR systems. Their work highlights core issues of conflicting privacy laws as EHR data across multi-jurisdictions. For example, in a country like Canada with multi-jurisdiction privacy laws, individual provinces like Ontario, Manitoba, Saskatchewan, and Alberta have adopted individual-specific health sector privacy legislation to protect against the conflicting application of these laws as various EHR systems exchange data. Although most of the issues were discussed in Young et al., the authors [

23] did not propose a mechanism to address conflicting privacy policies or establish control to protect the EHR system. Other authors such as Reegu et al. work focus on systematic review of interoperability requirements for blockchain-enabled EHR [

49]. The authors[

49] presented a systematic investigation current research trends, challenges, and solutions to implement blockchain to address the challenges [

49] . Similar work focuses on Blockchain-Based framework for interoperable EHR for an Improved system [

50]. The authors [

50] address research gap within this domain by developing an interoperable blockchain-based EHR framework that can fulfill the requirements defined by various national and international EHR standards such as HIPAA and HL7[

50].

Shultz et al. [

30] investigated the challenges of protecting data within EHR [

30]. The authors provided an overview of recent Electronic Health Record security breaches and their impact on healthcare providers and patients [

30]. Their work highlighted the impacts of health data breaches and related consequences from EHR breaches. They investigated two cases, the rationale of why hacking of electronic records is on the rise, and the challenges healthcare workers and regulators face [

30]. Although their work shed light on the recent surge of interest in EHR data breaches, they did not address or provide solutions to any challenges facing EHRs or propose any mitigation technique that can be used in any given EHR to deal with data theft or data protection. [

30]

The “Guide to Privacy and Security of Health Information “[

31] provides detailed knowledge on the importance of Privacy and Security within an EHR system. The authors [

31] made the case that the security of EHR is paramount to the delivery of care, and users should trust that the system's security does not disclose important medical information. The work [

31] analyzes EHR security from the point of view that expects the government to be instrumental in providing a mandate established through government policies as a recourse for a liable lawsuit where necessary due care and due diligence are not exercised to protect EHR data security and privacy. The authors discuss the concept of “meaningful use” to show the importance of providing access to any EHR based on the need-to-know concept, addressing the core objective of protecting EHR through technical means and conducting security analysis following sound security principles to address Information security risk. Although the authors [

31] provided sound work in EHR security, they failed to propose comprehensive technical controls or tools to address gaps in EHR security. Secondly, the authors did not provide administrative safeguards or address human factors challenges, which renders most EHR security vulnerable and susceptible to attack.

In the review of the security of EHR,” Khin [

32] analyzes a research question of whether the current information security technologies are adequate for EHR records. The author [

32] reviewed the most up-to-date Electronic Health Record security breaches resulting from inadequate security tools. The authors [

32] deduced that although current information technology security tools are in place, their adequacy is questionable in addressing private and public interests to achieve maximum usage of EHR security. All the authors [

32] analyzed incidents of security breaches within EHR, information security, and technology; they failed to propose any solutions for mitigating or minimizing risk related to EHR data security.

3.2. Artificial Intelligence of Things (AIoT) Integrated Healthcare Security and Privacy

In the journal article, “Enabling Artificial Intelligence of Things (AIoT) Healthcare Architectures and Listing Security Issues,” Anil Audumbar Pise [

45] and other researchers were able to validate and support the severity of their problem statement effectively [

45]. To exemplify, through their expansive research, they discovered various security and privacy concerns in AIoT (this would include systems, applications, and devices), which can consist of cell phones and wearable sensor devices. It’s imperative to understand that these devices produce sensitive data, and improper handling of this sensitive data can lead to a “major impact on the overall system’s and its stakeholders’ privacy and security”[

45]. It exemplifies how critical it is to properly and efficiently handle sensitive data as this would not significantly impact the Healthcare system and the stakeholders having privacy and security issues. In this case, these stakeholders would refer to internal people. To be more specific, this would refer to patients. To expand on privacy issues, this would include improper sharing of sensitive data (e.g., Heart rate, location), and it also ties in the violation of confidentiality, which means giving the data to unauthorized personnel. As for security issues, this would refer to a lack of encryption (or weak encryption like SHA-1) since this would refer to the data between the wearable device and the server. Without or having weak encryption, attackers (e.g., hackers) can see the traffic between these two components. Overall, Anil Audumbar Pise and other researchers [

45] had an effective and logical argument since they could explain thoroughly the privacy and security issues of AIoT.

In “Security issues and challenges in cloud-of-things-based applications for industrial automation,” Neeraj Kumar Pandey and other researchers [

43] were able to support the validity and severity of their problem statement. The researchers were able to address various security issues and challenges of AIoT. Their study found that “AIoT is used in the healthcare system, so most attacks are performed using HTTPS and DNS tunnels, ransomware, and BOTNETS. The radiology data is attacked more, so the storage servers of hospitals are soft targets.” [

43]. This shows that despite the certain security measures (e.g., firewall) that were in place in EHR, the attackers were able to penetrate through the network. The authors [

43] show that the severe impact on sensitive data and servers was also not secure. The authors [

43] also found that “most hospital chains share diagnostic data over the network for remote consultancy and expert opinion”[

43]. This exemplifies weakness in the healthcare center’s overall network based on the lack of encryption or weak encryption (e.g., SHA-1). Ultimately, the authors [

43] and other researchers had a solid and logical argument and provided many details regarding the security issues/challenges of AIoT.

In the research “Artificial Intelligence of Things for Smarter Healthcare: A Survey of Advancements, Challenges, and Opportunities,” Stephanie Baker and Wei Xiang [

42] proved the validity and security issues in AIoT. The authors [

42] discussed various challenges that AIoT brings to Healthcare. One of the major challenges that the authors [

42] assessed was security laboratory and clinical components. They demonstrated how availability, one of the components of the Confidentiality, Integrity, and Availability (CIA) triad, was negatively impacted. The authors [

42] showed that, for example, people with limited access could potentially include medical professionals, lab technicians, and biomedical engineers.

Unavailability would disrupt their productivity and result in financial and operational loss for the hospital. Not only that, other companies that have a relationship with the hospital would also see the hospital as untrustworthy if they don’t see any value. Hence, there is reputational loss. As for privacy concerns, the authors discussed one of their approaches to privacy. To amplify, this would include federated learning. This would allow various hospitals to train an ML (Machine learning) model without revealing sensitive patient information. The authors showed that federated learning could create a single point of failure for a single server for learning. In short, the authors argued that if the central server compromises, the other nodes will also be affected [

42].

The authors [

46] Rajeswari and Ponnusamy, in their work “Internet of Things and Artificial Intelligence in Biomedical Systems,” proved the validity and severity of security and privacy concerns in AIoT. The authors [

46] explained how biomedical systems incorporating IoT and AI can positively impact hospitals. Such includes “remote health monitoring, disease prediction and diagnosis, and treatment”[

46]. However, it’s important to note that there are many challenges to these biomedical systems, including significant challenges that would include security and privacy. The authors identify such concerns, including tampering with the original data and modifying is the nightmare of any technology, ease of access to AIoT system datasets and computational power (Graphics Processing Unit )) have been considered severe threats to growing AIoT technology [

46]. Overall this study differs from many existing study review as it amongst the few of the selected work that focus on using ARIMA model to provide a detailed analysis of the data demonstrating breaches caused by hacking and IT incidents show a significant trend analysis to describe, demonstrate, summarize data points, and predict type of breaches, and point of breaches within Healthcare and health entities.

4. Methodology

We complemented the findings from a literature overview with an examination and analysis of current Health Information Protection Portability Act (HIPPA) breach data. The focus of this work is on AI integrated EHR devices with potential to collect, process, stored PHI. To address the research question, we conducted an exploratory study into currently reported attacks on hospitals and related healthcare entities from 2010 to 2022, utilizing HIPPA breach reporting data. HIPPA breach reporting data is a multi-stage, specific self-reporting electronic form survey filled out by health entities within the United States who discover a breach of unsecured protected health information. For a breach affecting 500 or more individuals, covered entities must notify the Secretary of Health and Human Services within 60 days following a breach. However, covered entities can report a breach that affects less than 500 individuals within a year and sixty days. All the data are publicly available online (

https://ocrportal.hhs.gov/ocr/breach/breach_report.jsf).

Based on this data, we assess the type of Cyberattack, trends, and impact in healthcare institutes required to meet HIPPA security and privacy compliance. This exploratory study evaluates the current HIPPA breach reported data to analyze it and interpret observations about commonly known attacks, adversary attack patterns in healthcare, and how affected companies differ by type, state, technical control, etc. In addition, we sought to identify the main security vulnerabilities, failure in technical controls, and different threat agents that learned to breach EHR systems, impacting user privacy violations or affecting critical healthcare operations and patient safety. The empirical study complements the gaps from a literature overview to identify potential new issues in EHR security. The mainmethod processes involves:

Collect, analyze, and interpret observations about current EHR systems, design to look for specific phenomena in EHR data breaches, and look for patterns to determine relative importance to Cyberattack.

Identify shows that EHR systems serve as a goldmine for an attacker, lack sufficient control to guarantee patient privacy and hospital operation continuity during a Cyberattack, and require integration, implementation, and application of essential security principles, controls, and strategies necessary to safeguard patient data generated through the EHR systems life cycle.

To understand why a particular type of attack occurs, how the attack is conducted, whom it affects, how it impacts stakeholders, the mood of the attack, affected systems, period of attack (if IT staff is around), location of breached information on the Network/System, type of breach, and the number of affected records, and privacy of safety impact.

Data Description

We downloaded a copy of the 2010 to 2022 breach reporting data from the USA Department of Health and Human Services data download portal (

https://ocrportal.hhs.gov/ocr/breach/breach_report.jsf). As required by section 13402(e)(4) of the HITECH Act, the US Secretary of Health and Human Service must post a list of breaches of unsecured protected health information affecting 500 or more individuals [

33]. In addition, we downloaded 24 months of all health data breaches reported within the last 24 months that are currently under investigation by the Office for Civil Rights.

As illustrated in

Table 2, we organize the download Excel file column into “Name of Covered Entity,” “Breach Submission Date,” “Individual Affected,” State, “Covered Entity Type,” “Number of Individual Affected,” “Type of Breach,” “Location of Breached Information,” “Business Associate Present.”

5. Descriptive Analysis

5.1. Covered Entities

The covered entities in the dataset include business associates, health plans, healthcare clearing houses, and healthcare providers.

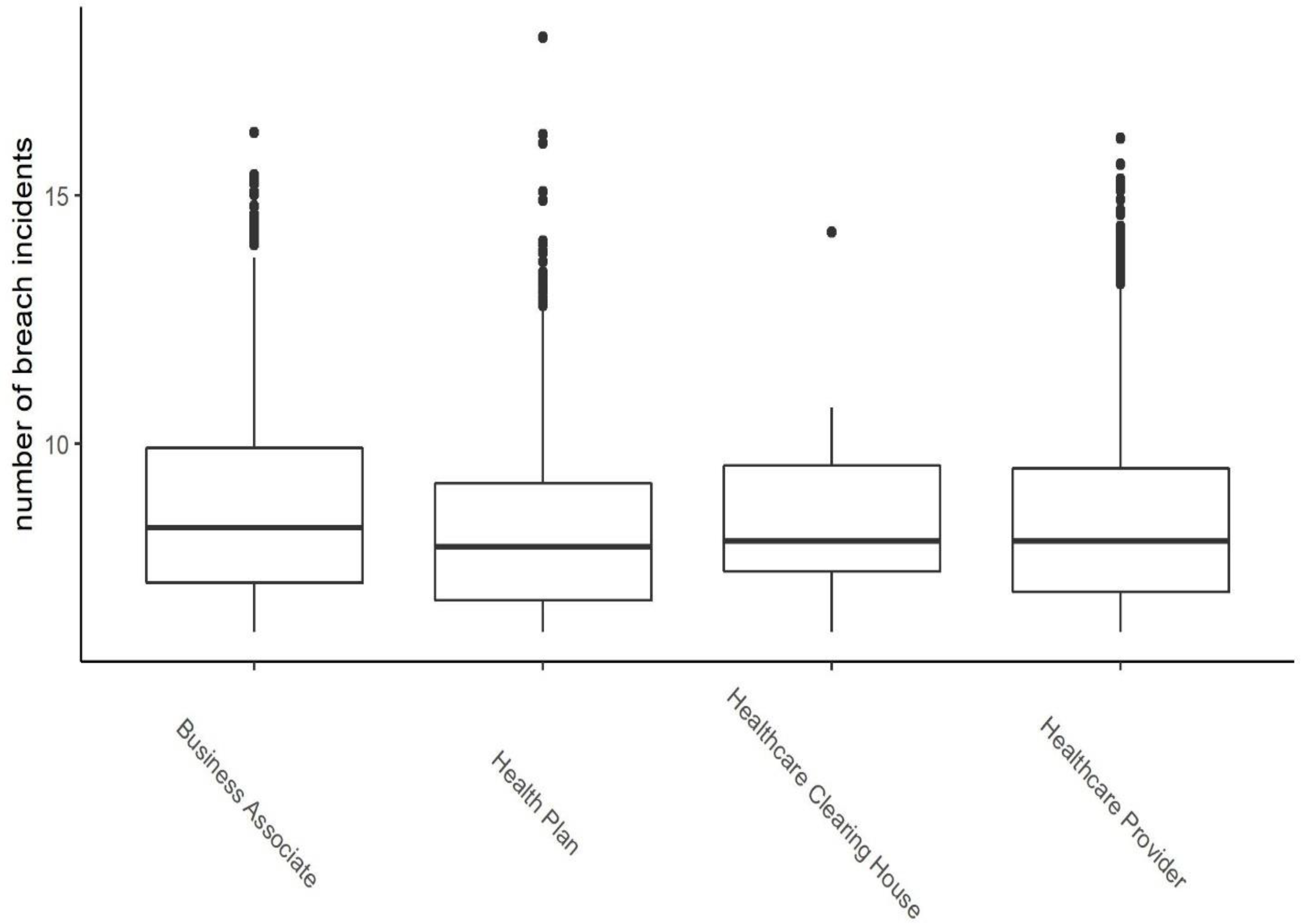

Figure 2 shows the frequency distribution of the number of individuals involved in data breaches for each category of the covered entity. The vertical axis is in log scale for better illustration. From

Figure 2, it is evident that the distributions of the number of individual records in breach incidents on all categories of covered entities are skewed toward zero, meaning that most of the incidents involved a low number of personal health records and all categories, except healthcare clearing houses, have outliers with incidents involving a high number of personal health records.

A deeper insight can be gained from

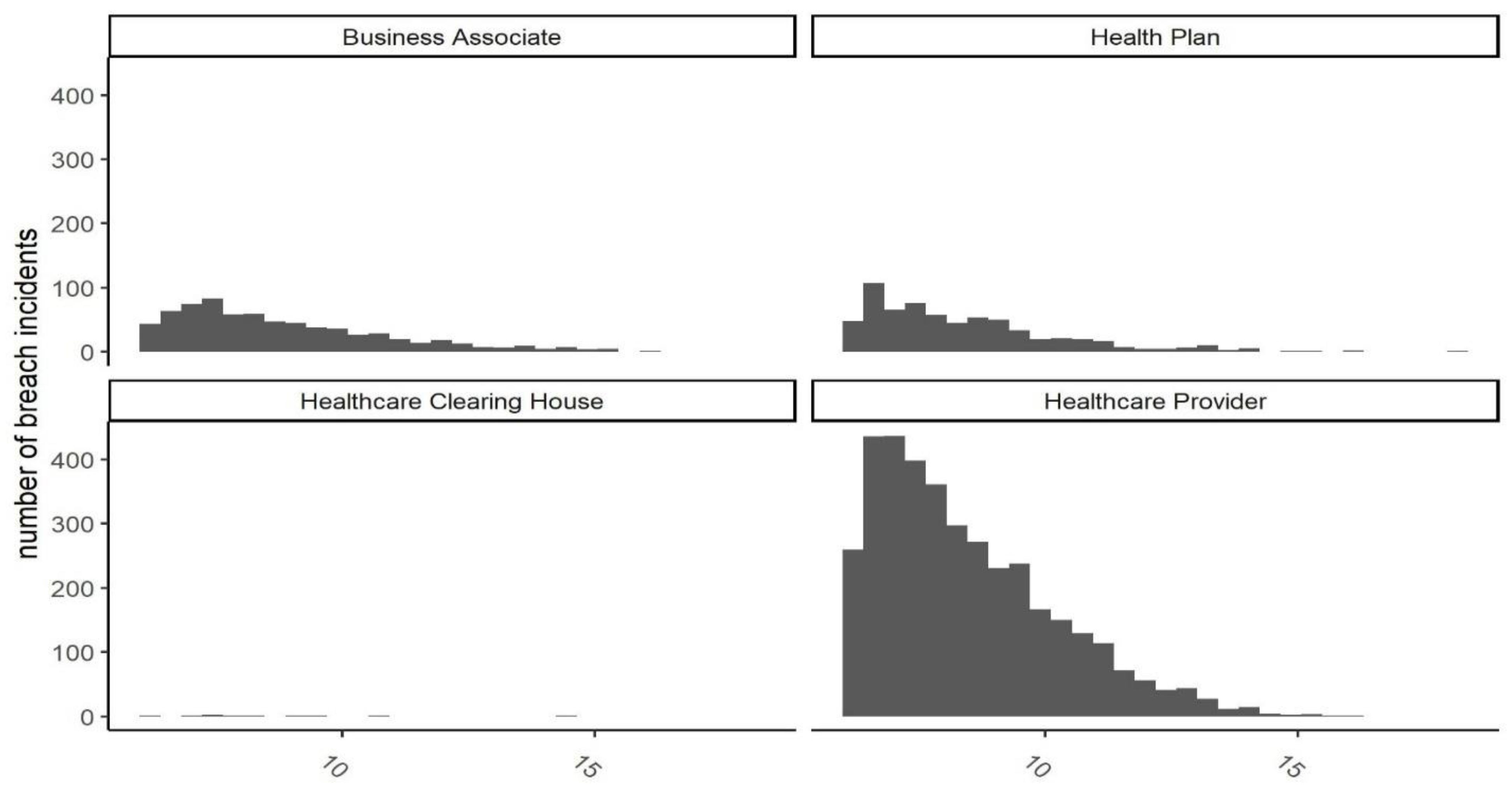

Figure 3, showing histograms of each category. The figure shows that skewness toward zero is more significant for the healthcare provider category, while health plans and business associate categories seem to have a more uniformly distributed number of records. This figure also shows that the category healthcare clearing house does not have a meaningful number of incidents, with only 10 data breaches.

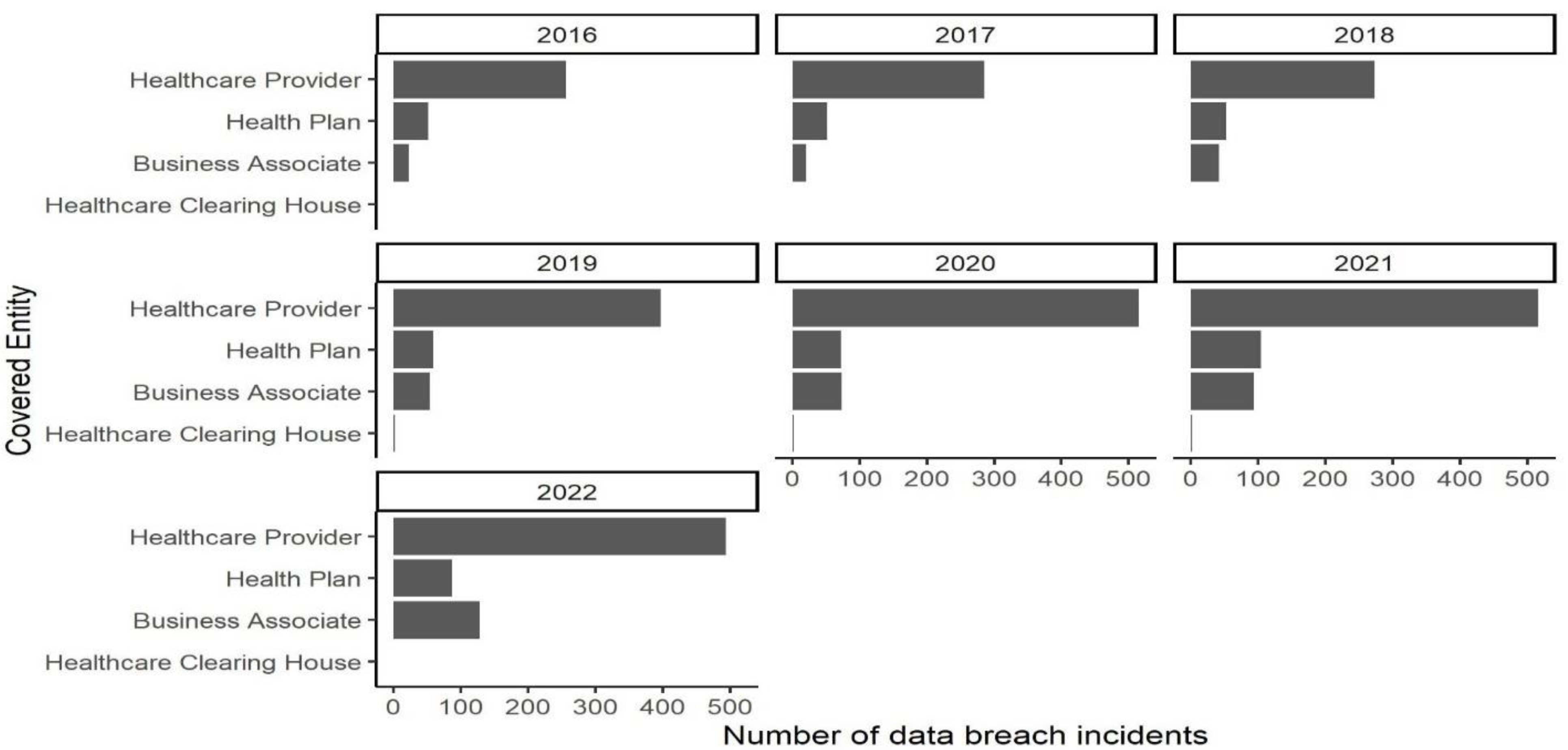

Figure 4 shows trends in incidents by covered entity type from 2016 to 2022. As illustrated, healthcare providers are consistently at the top in the number of breaches during the analyzed period, and the trend is increasing. Healthcare clearinghouses had negligible incidents attributable to them. The health plan category seems to have a constant share of all incidents throughout the period. The most interesting pattern in this figure is the increasing trend in the number of incidents belonging to business associates. This might be due to regulatory pressure from on hospitals contracting with businesses or consumer pressure on business associates.

5.2. Type of Breaches

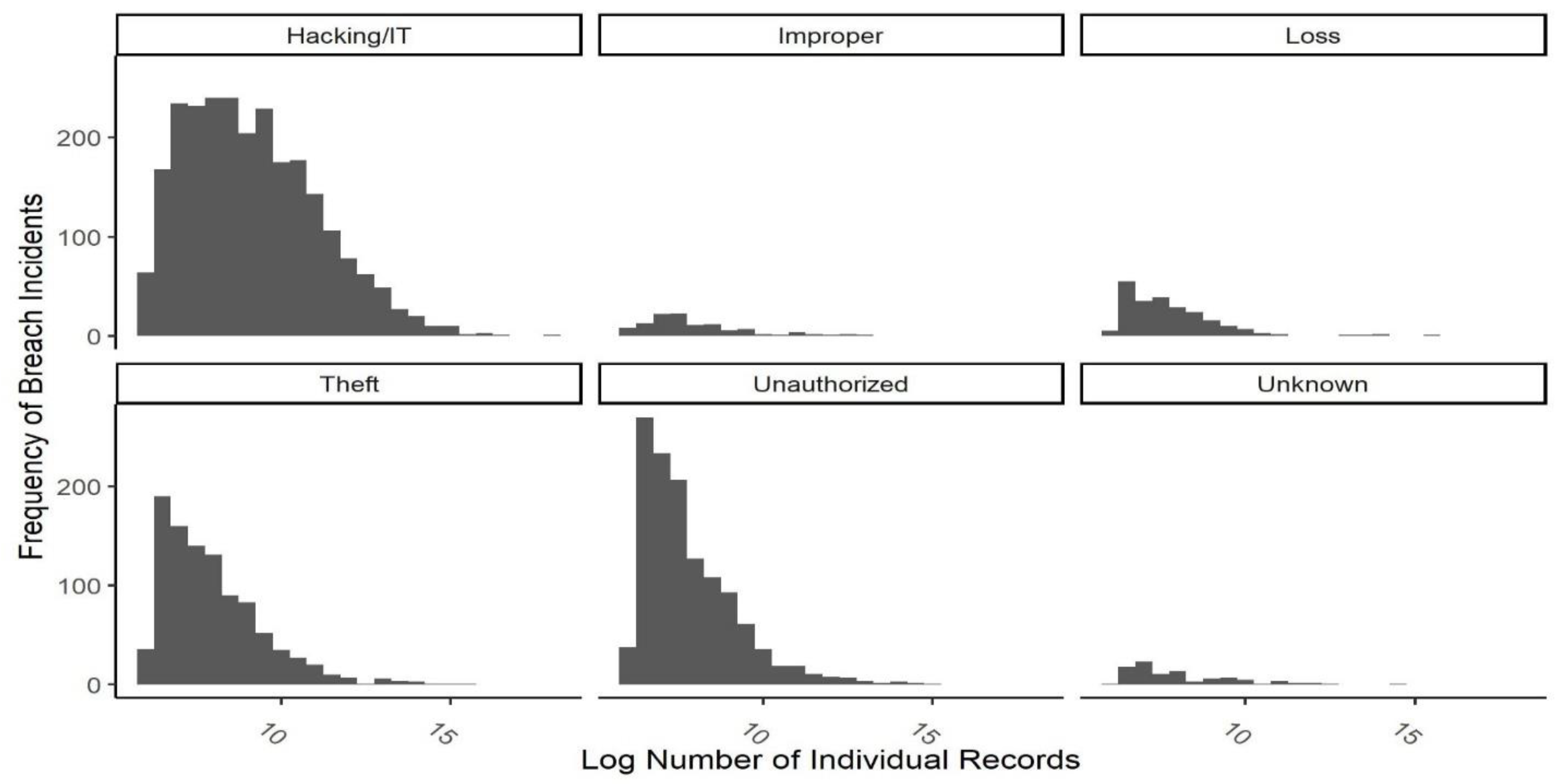

The type of breach is inconsistently reported in the original dataset. For example, the type of some incidents is recorded as theft/improper access/Hacking. We cleaned the dataset and recategorized the type of incidents based on the content in the description column. We identified five main categories of types of breaches: hacking/IT incidents, improper disposal, loss, theft, and unauthorized access/disclosure.

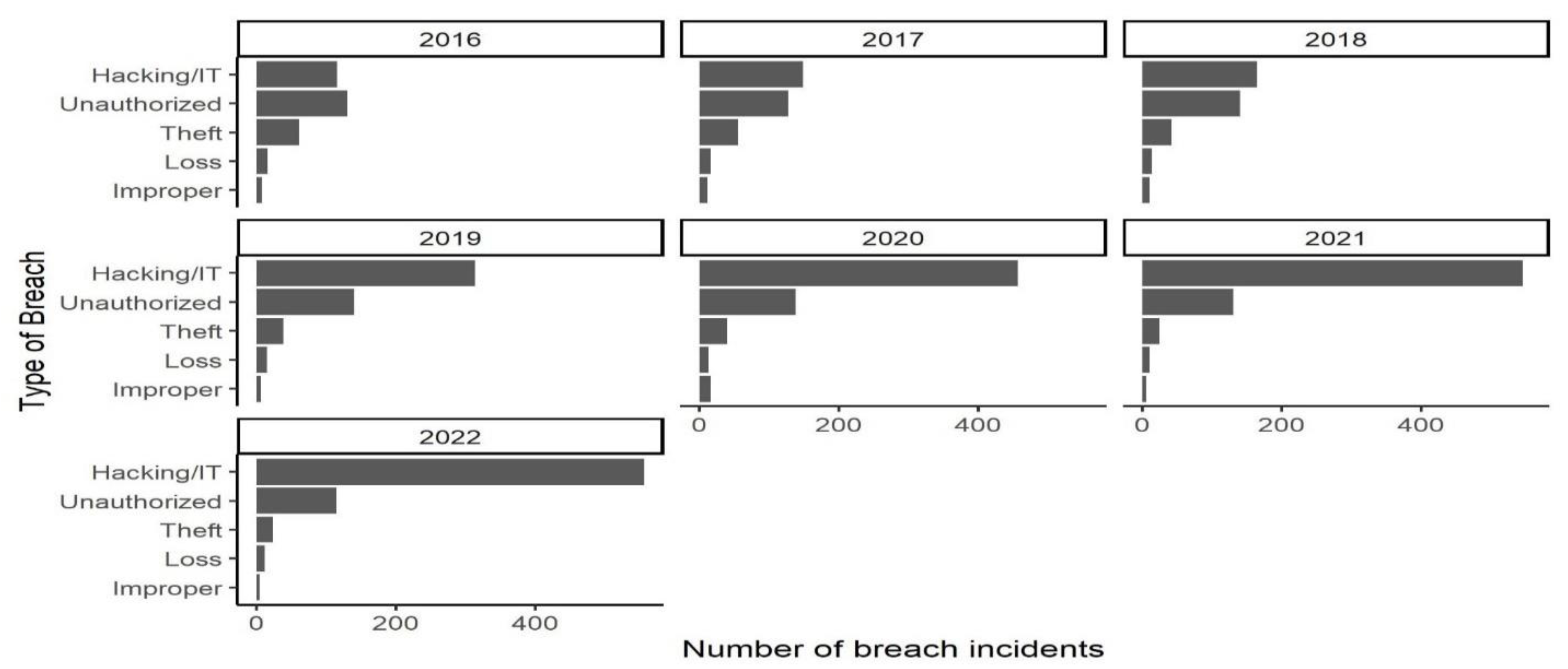

Figure 5 illustrates the frequency distribution of the size of breach incidents for each type of breach. It is evident from the figure that most of the majority of incidents belong to the Hacking/IT incidents category. The distribution of all categories is skewed towards zero, meaning that most incidents involved a low number of individual records. However, the distribution of the Hacking/IT incidents category is less skewed and includes more incidents with a high number of individual records involved. The implication is that, while incidents such as theft of devices or unauthorized access usually occur in settings with a small number of individual records, such as small hospitals and healthcare providers, Hacking and IT incidents occur in high-stake settings with large numbers of individuals involved.

Figure 6 illustrates the trends of the number of breach incidents for each specified type of breach. The significance of unauthorized access remains constant while hacking/IT type increases, especially since 2018. This may show the increasing vulnerability of health organizations in their network and server systems when criminals can access and steal health data by hacking IT infrastructure.

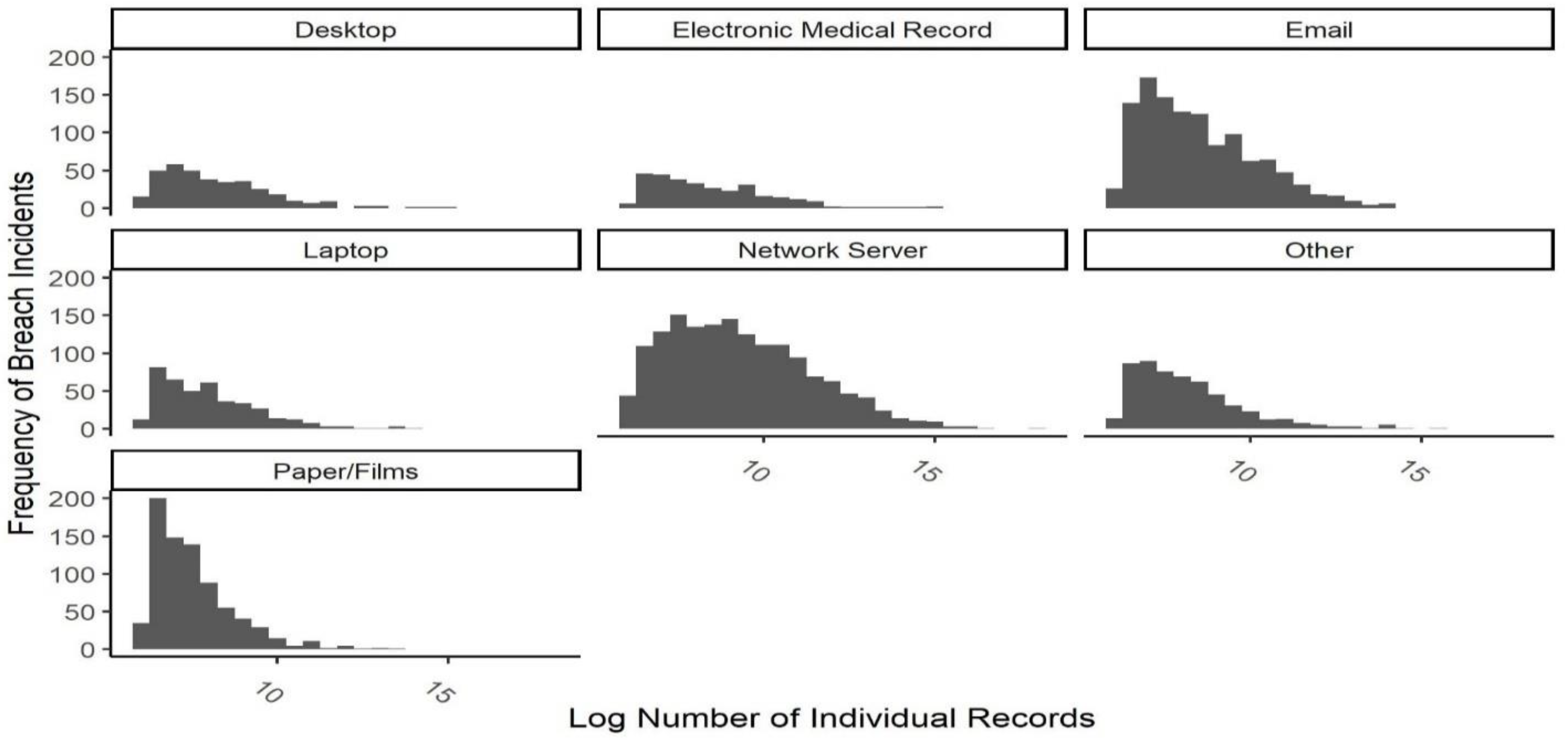

5.3. Point of Breaches

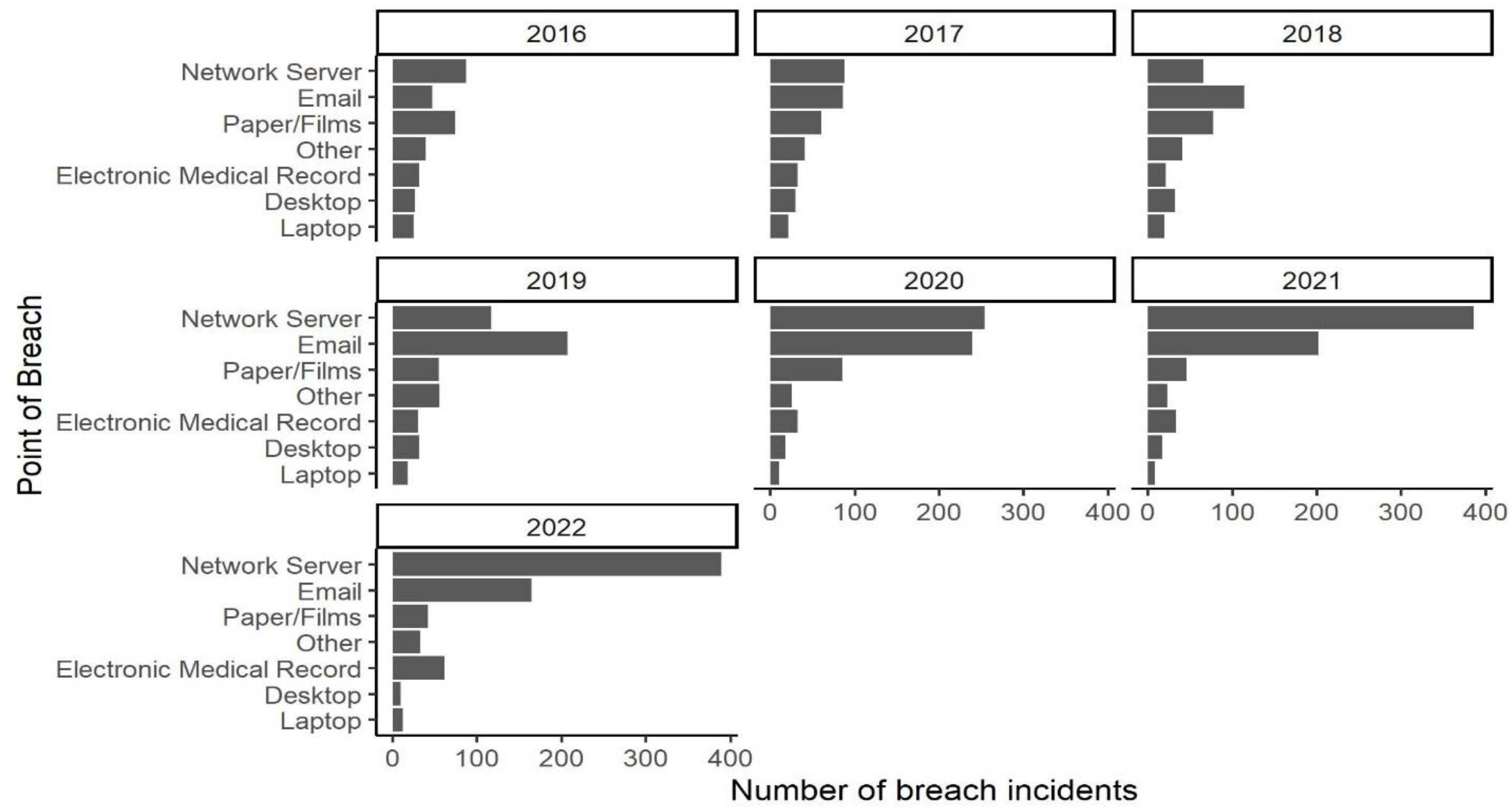

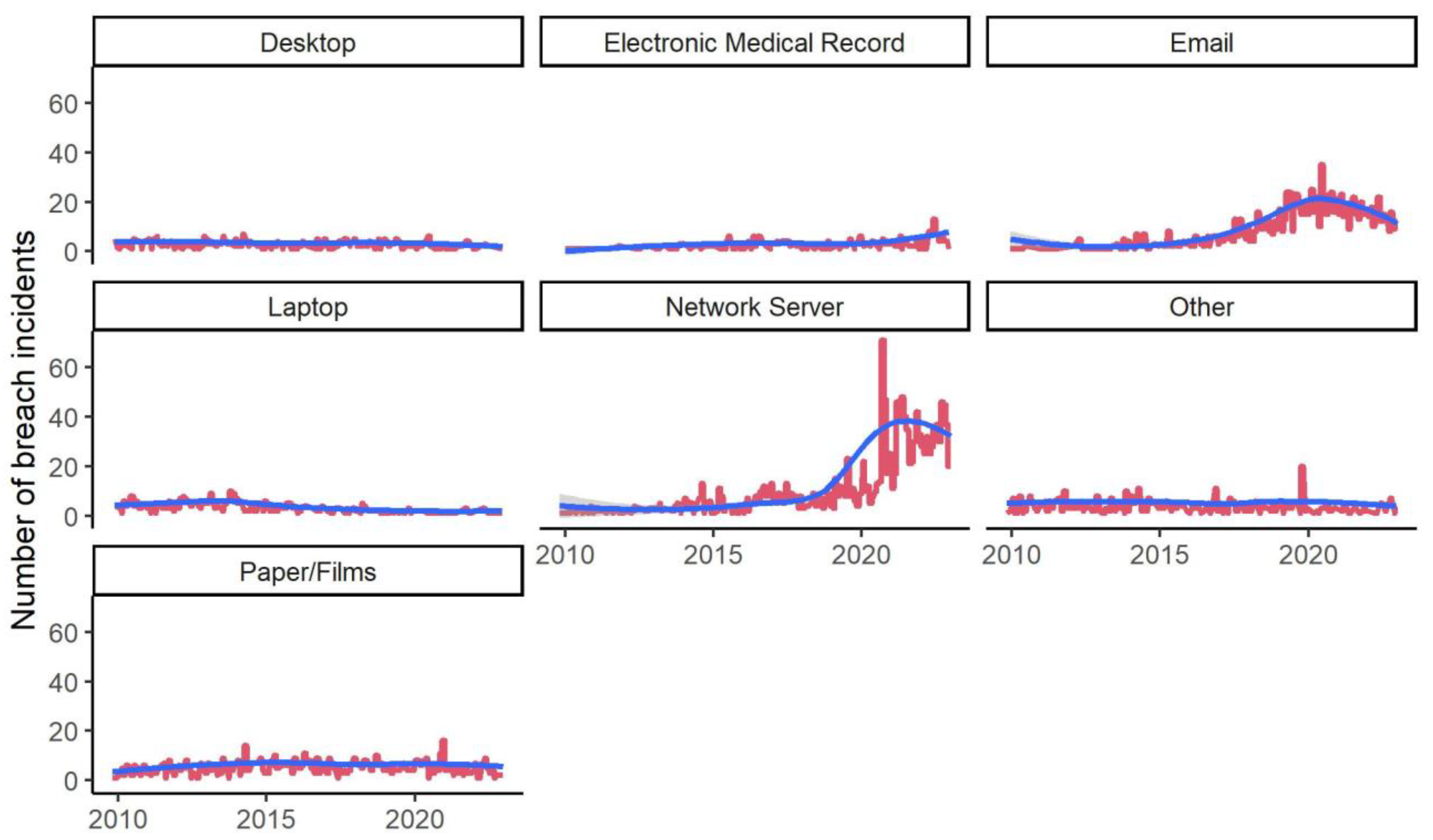

Figure 7 shows the frequency distribution of the size of breach incidents for each category or type of breach. Almost all categories have size distributions skewed toward zero, meaning that the individual health records involved in most incidents have been smaller than 20 thousand. The exceptions are “Network Server” and “Email” groups, which, although still skewed, have many incidents with a high number of individual records breached.

Figure 8 illustrates the trends of the number of breach incidents in each group of points of breach in the dataset. It is evident from the figure that the significance of the two groups of “Network Server” and “Email” has been consistently increasing since 2016, while other groups remain constant.

6. Trend Analysis

6.1. Type of Breach

We first examine the trends of the incidence occurrence by the type of breach.

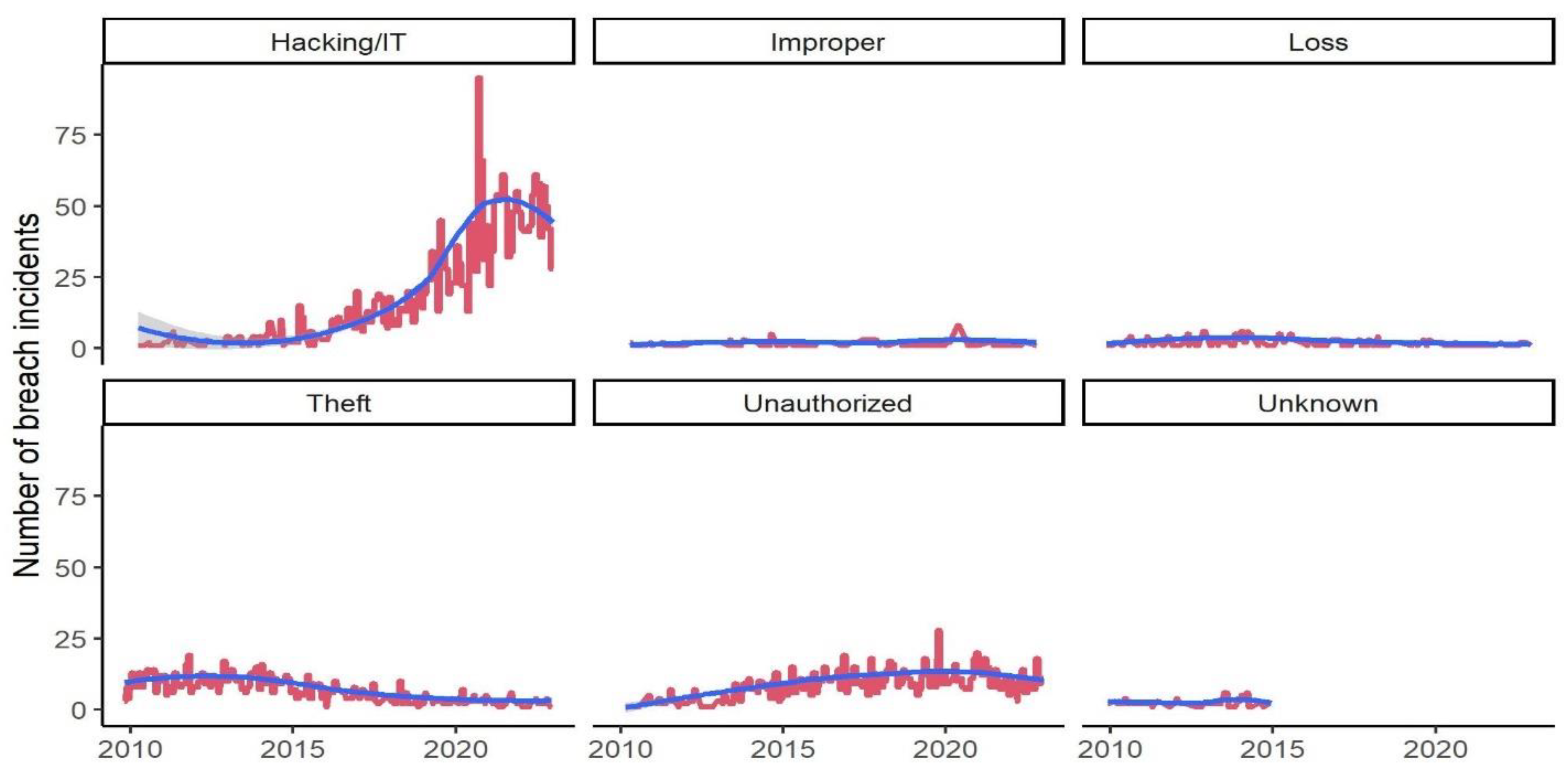

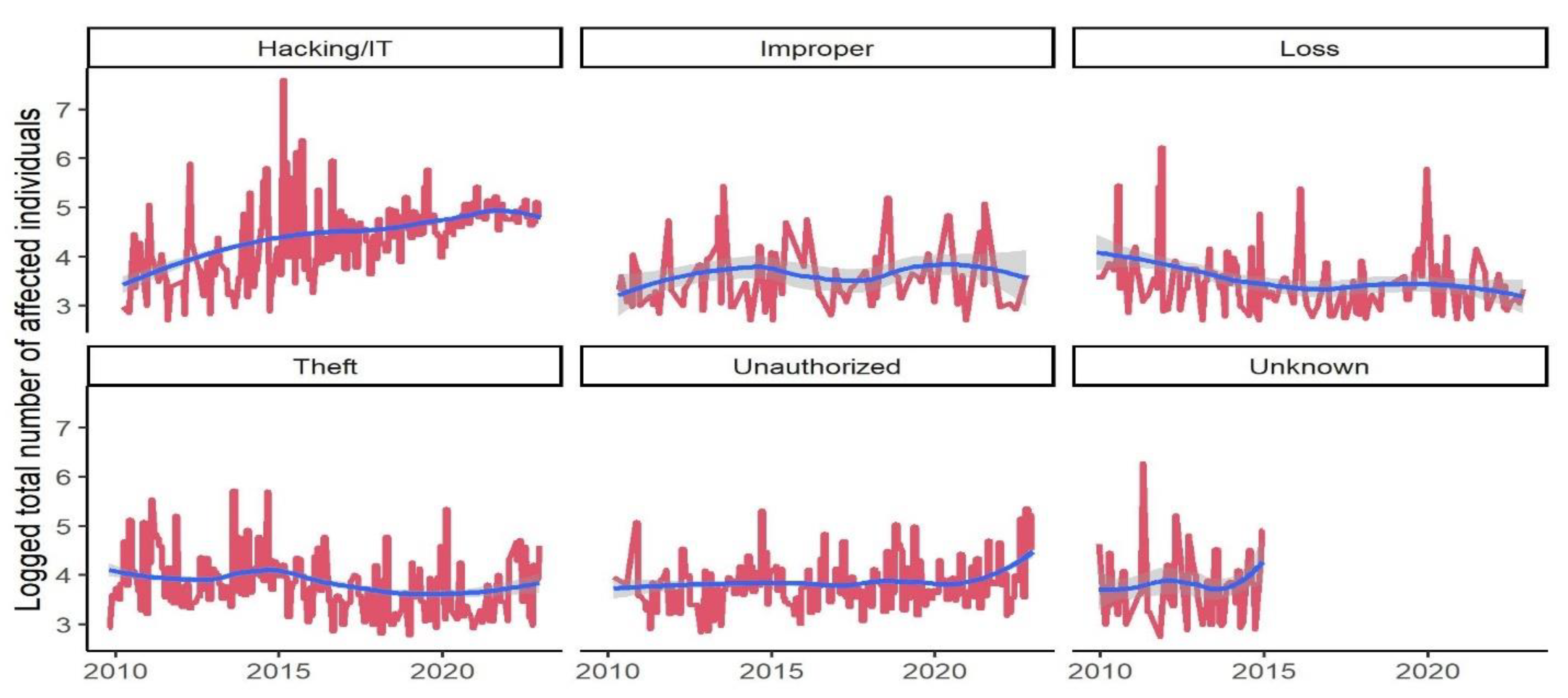

Figure 9 illustrates the monthly number of breach incidents by the type of breach in the red line. The number of breach incidents attributed to “Hacking/IT” has been increasing consistently throughout 2010 to 2022. The blue line indicates the estimated LOESS (locally estimated scatterplot smoothing). This visual exploratory analysis implies that while data breaches caused by improper use of devices, loss of data or devices, theft, and unauthorized access have been relatively constant during the analysis period, incidents caused by hacking and other deliberate attacks on IT infrastructures have witnessed an increasing trend. Analyzing the average number of personal records breached (number of affected individuals) provides a better view of the trends.

Figure 10 illustrates the monthly average personal records reported in the dataset grouped by the types of breaches. The logged total number of affected individuals is relatively low and stays constant during the analysis period for all groups. There is one exception, which is incidents caused by hacking. The average number of individuals has grown from 20000 to 160000 individuals for incidents caused by hacking, while for other groups, the number is around 3000 and remains constant. For more detailed analysis, we fit the data to the ARIMA model and reported the coefficients and their significance in

Table 3 and

Table 4.

Consistent with the visualization, breaches caused by hacking and IT incidents show a significant trend (coefficient 0.84, p-value < 2.2e-16 ***). Interestingly, the Theft and Unauthorized types are also significant and increasing. However, these two types have much smaller coefficients. Unlike visuals, the results of ARIMA models for the trends of median size of the breaches show that all types of breaches have no significant trends. This indicates the high amount of noise in breach-size data that could have originated from measurement errors, inconsistent reports to Health and Human Services , and misattribution of records [

48]. These results partially support our H0 hypothesis indicating a significant increasing trend in the number of incidents but inadequate evidence of the increased number of individual records lost in each breach incident. In other words, although the median size of data breach incidents remained unchanged the frequency of the occurrence of those breaches has increased significantly. This trends show that current EHR implementations lack sufficient security controls, thus compromising patient privacy, safety, and hospital operation continuity during a cyberattack.

6.2. Point of Breach

Analyzing trends for groups of data breaches based on the point of the breach could provide deeper insights into recent developments in health records security.

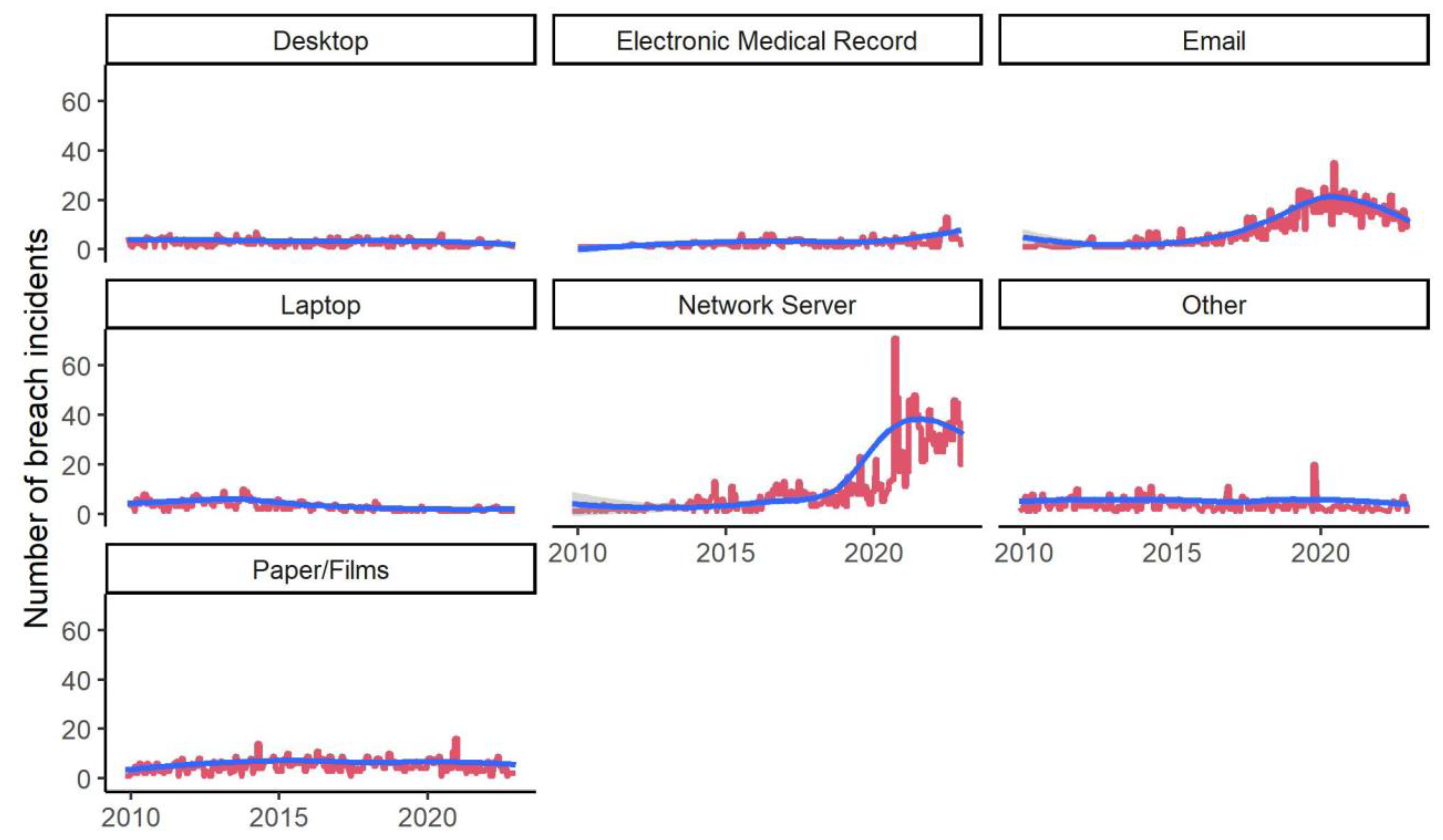

Figure 11 illustrates the monthly number of data breach incidents during the analysis period for each incident category based on the breach point. The number of breaches that occurred via network servers, email, and electronic health record management systems show increasing trends. For further investigation, we ran an ARIMA model to see if the trends were statistically significant. The results are shown in

Table 5. Consistent with visuals, ARIMA coefficients for all types of breach are statistically significant except for the groups Desktop and Other. The largest coefficients belong to Network Servers and Email groups, indicating the increasing usage of these platforms for communication and inappropriate access to health records. Changes in the median size of breach incidents in terms of the number of personal health records are illustrated in

Figure 12. In line with our discussion in the previous section, due to the large noise in the report of the size of data breaches, we cannot identify any meaningful trend in this variable for any point of the breach.

Table 4 provides further evidence of this issue. The results show that, historically, most prevalent points of vulnerabilities have been via emails, network servers, papers/films, and laptops. From these points of breach, however, the frequency of incidents has significantly been increasing for emails, electronic medial records, network servers, and laptops but not for other groups. The median size of breach for different points of breach incidents do not show any significant trends. These results support our H1 indicating that most EHR cybersecurity attacks are concentrated using similar attack methodologies and face common vulnerabilities.

7. Discussion & Conclusions

To look for avenues of addressing data security issues within EHR, it must be established, understood, and agreed on that EHR data must be treated differently, and priority must be set to protect it at all costs. EHR data is about people, usually people's health data. It's unique in finding ways, tools, and methodology to prevent it from getting into the hands of the wrong people or being used for non-intended purposes. In addressing the inherent problem with data breaches, the crucial part focuses on the understanding that once patient data confidentiality is breached and the data is within the public sphere, it can not be retracted. Its effects can be more significant and far-reaching than ever imagined. Again, this makes EHR data unique and requires very stringent mechanisms and rules to protect it within the EHR.

The importance contribution of this work is centered around provision of descriptive analysis of PHI breach data empathizing on the individual covered entities and impact of cyber-attack breach. Such information is important for other researchers in understanding the various data breach risk associated with each covered entities and required targeted solution that can be applied. Similarly, these entities can garner information from this work to understand where within their infrastructure they should be spending the limited security budget in addressing risk. Overall, the detailed analysis of current Health Data breaches to demonstrate common modes of attacks highly breach area assets within the EHR infrastructure, allowing health entities to invest in solutions that focus on identified areas.

Second, contribution made through the analysis of frequency of type of breach, and points of breaches, is an important one in understanding the most occurring breach type, method use by adversary. This contribution allows stakeholders within the healthcare domain to understand the requisite controls needed to address the most occurring breach type with maximum impact. Such information allows organization to prioritize risk and required effort needed to address them. Such descriptive and trend analysis to describe, demonstrate, summarize data points, and predict the direction of EHR data breaches based on current and historical data by a covered entity for other researchers to build on our work.

In this work, we demonstrated that Electronic Health Record (EHR) data breaches create severe concerns for patients' privacy, safety, and risk of loss for healthcare entities responsible for managing patient health records. This explorative work into current Artificial Intelligence of Things integrated EHR cybersecurity attacks using United States Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) privacy and security breach reported data shows through a descriptive and trend analysis breaches caused by hacking and IT incidents show a significant trend (coefficient 0.84, p-value < 2.2e-16 ***) over the duration of the data collection. The finding indicates that individual records in breach incidents on all categories of covered entities are skewed toward zero, demonstrating that healthcare providers are consistently at the top in the number of breaches. Further, the trend is increasing, with the number of breach incidents attributed to “Hacking/IT” increasing consistently from 2010 to 2022. The analysis validated the first hypothesis that Artificial Intelligence of Things integrated EHR implementation lacks sufficient security controls to guarantee patient privacy, safety, and hospital operation continuity during a cyberattack. The analysis proved that attacks integrated AIoT EHR systems are concentrated using similar attack methodologies and face common vulnerabilities. The reliability of this explorative research work was through retesting and reanalyzing the HIPAA breach data. The result receive was consistent with the initial result and analysis. The limitation of this work focus on the authors inability to validated if companies are reporting all data breaches to US Health and Human services. As such the feature work is to evaluate and explore automated breach reporting options to ensure a level of accurate data report.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare. All co-authors have seen and agree with the manuscript’s contents, and there is no financial interest to report. We certify that the submission is original work and is not under review at any other publication.

References

- Sherman, G.; Towards Electronic Health Record. Health Canada: Office of Health and the Information Highway 2001. Available online: https://publications.gc.ca/collections/Collection/H21-166-2001E.pdf (accessed on day month year).

- CDC. Electronic Medical Records/Electronic Health Records. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/electronic-medical-records.htm (accessed on 5 December 2021).

- Camps, C.J.R.; Wainer, J.; Salinas, M.D.U.; Sigulem, D.; Security Requirements for a Lifelong Electronic Health Record System: An Opinion. The Open Medical Informatics Journal 2008 2, 160-165. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2669643/ (accessed on 5 December 2021).

- Frampton, S.; and Guastello, S. Patient-Centered Care Guide. (accessed on 5-Dec-2021]. Available online: http://www.patient-centeredcare.org/inside/practical.html (accessed on 5 December 2021).

- Chromium, P. The Chromium Projects: System Hardening. 28 March 2021. Available online: http://www.chromium.org/chromium-os/chromiumos-design-docs/system-hardening (accessed on 28 March 2021).

- Humphries, M. AI Leaks Over 2.5M Medical Records. Available online: https://uk.pcmag.com/encryption/128228/report-ai-company-leaks-over-25m-medical-records (accessed on day month year).

- Clmpanu, C. AMCA data breach has now gone over the 20 million mark”. Available online: https://www.zdnet.com/article/amca-data-breach-has-now-gone-over-the-20-million-mark/ (accessed on 20 November 2021).

- Tidy, J. Hackers Threaten to Leak Plastic Surgery Pictures. Available online: https://www.bbc.com/news/technology-55439190 (accessed on 1 November 2021).

- Murphy, H. Why a Dat Breach at a Genealogy Site Has Privacy Expert Worried. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2020/08/01/technology/gedmatch-breach-privacy.html?referringSource=articleShare (accessed on 20 Octomber 2021).

- Iwin, L. ; Breach at Norway’s Largest Healthcare Authority Was a Disaster Waiting to Happen. Available online: https://www.itgovernance.eu/blog/en/breach-at-norways-largest-healthcare-authority-was-a-disaster-waiting-to-happen (accessed on 24 October 2021).

- Sailpoint. SailPoint Market Pulse Survey: The Data Breach Battle. Available online: http://assets.fiercemarkets.net/public/newsletter/fierceemr/sailpoint.pdf (accessed on 5 November 2021).

- ________. Implementation of Electronic Records. Available online: http://openonlinecourses.com/ehr/ImplementationOfInformationSystems.asp (accessed on 23 August 2021).

- _________. Data Sharing Principles.” The Canadian Medical Protective Association. Available online: https://www.cmpa-acpm.ca/static-assets/pdf/advice-and-publications/handbooks/com_electronic_records_handbook-e.pdf (accessed on 15 October 2021).

- ______. Healthcare in Digital Age: Who owns data.” The Wall Street Journal. Available online: http://live.wsj.com/video/health-care-in-the-digital-age-who-owns-the-data/28B6E0AD-8506-40B2-A65920A9B696F524.html?goback=%2Egna_2890588%2Egde_2890588_member_191525235#!28B6E0AD-8506-40B2-A659-20A9B696F524 (accessed on 5 December 2021).

- Sharma, R. Who Really owns You’re your Health Data? Available online: https://www.forbes.com/sites/forbestechcouncil/2018/04/23/who-really-owns-your-health-data/?sh=3bf0587c6d62 (accessed on 23 November 2021).

- King, M. Who Owns Your Banking Data? Available online: https://iveybusinessjournal.com/who-owns-your-banking-data/ (accessed on September 2021).

- _______. When law and medicine intersect: Influential court decision still relevant to patient's access to medical records.” The Canadian Medical Protective Association December 2011. Available online: http://www.cmpa-acpm.ca/cmpapd04/docs/resource_files/perspective/2011/04/com_p1104_3-e.cfm (accessed on 23 Octomber 2021).

- Takach, G. Computer Law, 2nd ed.; Irwin Law: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2003; p. 515. [Google Scholar]

- Saksena, N.; Matthan, R.; Bhan, A.; et al. Rebooting consent in the digital age: A governance framework for health data exchange. BMJ Global Health 2021, 6, e005057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- _______. Health Services in Your Community. Available online: http://www.health.gov.on.ca/english/public/contact/hosp/hospfaq_dt.html (accessed on 23 August 2021).

- Valerius, J.D. The Electronic Health Record: What Every Information Manager Should Know. Available online: http://www.arma.org/bookstore/files/Valerius.pdf (accessed on 15 February 2013).

- ______. Frank Abagnale. Wikipedia. Available online: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Frank_Abagnale (accessed on 16 February 2013).

- Young, D. Electronic Health Records-Privacy and Security Issues. McMillan. 2010. Available online: http://www.mcmillan.ca/Electronic-Health-Records--Privacy-and-Security-Issues (accessed on 12 June 2012).

- ___________. Electronic Health Records in Canada: An Overview of Federal and Provincial Reports.” Office of the Auditor General of Canada. April 2010. Available online: http://www.oag-bvg.gc.ca/internet/English/parl_oag_201004_07_e_33720.html (accessed on 2 July 2012).

- Yankson, B. Ubiquitous Biometrics NOW: Identity Management Solution for the Canadian Government, Canadian Business, and You. UOIT MITS Course Project December 2011.

- ________. Hospital Treating Kate Middleton falls for a prank call.” Toronto Star December 5th, 2012. Available online: http://www.thestar.com/news/world/article/1297749--hospital-treating-kate-middleton-falls-for-prank-call-gives-out-health-information (accessed on 18 January 2013).

- McMurch, T. EHEALTH SASKATCHEWAN SECURITY REVIEWS UNDER WAY FOLLOWING COMPUTER DISPOSAL ERROR. Government of Saskatchewan March 27, 2012. Available online: http://www.gov.sk.ca/news?newsId=202531cf-0596-40fa-9434-5d2c4aa6135a (accessed on 15 January 2013).

- Priest, L. A sickening side-effect of the eHealth revolution. Globe and Mail September 6, 2012. Available online: http://m.theglobeandmail.com/news/politics/a-sickening-side-effect-of-the-ehealth-revolution/article2315265/?service=mobile (accessed on 17 January 2013).

- _________________. Electronic Health Record Infostructure (EHRi): Privacy and Security Conceptual Architecture.” Health Canada Infoway June 2005. Available online: https://knowledge.infoway-inforoute.ca/EHRSRA/doc/EHR-Privacy-Security.pdf (accessed on 15 July 2012).

- Shultz, D. As Patients’ records Go Digital, Theft and Hacking Problem grow. Kaiser Health News June 3rd, 2012. Available online: http://www.kaiserhealthnews.org/Stories/2012/June/04/electronic-health-records-theft-hacking.aspx (accessed on 20 July 2012).

- ___________________. Guide to Privacy and Security of Health Information. Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology. Available online: http://www.healthit.gov/sites/default/files/pdf/privacy/privacy-and-security-guide.pdf (accessed on 2 July 2012).

- Khin, T.W. A Review of Security of Electronic Health Records. Health Information Management 2005, 34, 13–17. Available online: https://www.cs.uwaterloo.ca/twiki/pub/Main/MaxwellYoung/Review_Win.pdf (accessed on 12 August 2012).

- Available online: https://ocrportal.hhs.gov/ocr/breach/breach_report.jsf.

- Available online: https://www.onespan.com/topics/biometric-authentication.

- Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat: Federating Identity Management in the Government of Canada: A Backgrounder. Available online: http://www.tbs-sct.gc.ca/sim-gsi/publications/docs/2011/fimgc-fgigc/fimgc-fgigctb-eng.asp (accessed on day month year).

- El-Khatib, Khalil: Biometric, Access Control, and Smart Card Technology: Lecture 1 page 15. University of Ontario Institute of Technology, Oshawa Ontario, September 2012.

- Feldman, Robin: Considerations on the Emerging Implementation of Biometric Technology, 2004. Available online: http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=492444 (accessed on 21 November 2013).

- Available online: https://www.onespan.com/blog/behavioral-biometric-authentication-will-kick-passwords-curb-sooner-you-think.

- Reeder, W. Expandable Grids for Visualizing and Authoring Computer Security Policies. Available online: http://dl.acm.org/citation.cfm?id=1357285 (accessed on 22 January 2013).

- Saltzer & Schrober. The Protection of Information in Computer Systems. The University of Virginia, Department of Computer Science. Available online: http://www.cs.virginia.edu/~evans/cs551/saltzer/ (accessed on 30 January 2013).

- Warfield, C. The Disaster Management Cycle. Available online: http://www.gdrc.org/uem/disasters/1-dm_cycle.html (accessed on 1 March 2013).

- Baker, S.; Xiang, W. Artificial intelligence of things for smarter Healthcare: A survey of advancements, challenges, and opportunities. IEEE Communications Surveys & Tutorials 2023, 25, 1261–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, N.K.; Kumar, K.; Saini, G.; Mishra, A.K. Security issues and challenges in cloud of things-based applications for industrial automation. Annals of Operations Research 2023, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pappakrishnan, V.; Mythili, R.; Kavitha, V.; Parthiban, N. Role of artificial intelligence of things (AIoT) in COVID-19 pandemic: A brief survey. In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Internet of Things, Big Data and Security; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Pise, A.A.; Almuzaini, K.K.; Ahanger, T.A.; Farouk, A.; Pant, K.; Pareek, P.K.; Nuagah, S.J. Enabling artificial intelligence of Things (AIoT) healthcare architectures and listing security issues. Computational Intelligence and Neuroscience 2022, 2022, 8421434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajeswari, S.V.K.R.; Ponnusamy, V. Internet of Things and artificial intelligence in biomedical systems. In Artificial Intelligence for Innovative Healthcare Informatics; Springer International Publishing:, 2022; pp. 153–177. [Google Scholar]

- Yankson, B.; Ottah, A. Investigating HIPAA Cybersecurity & Privacy Breach Compliance Reporting During Covid-19. 18th Annual Symposium on Information Assurance 2023, 18, 14–21. [Google Scholar]

- Barati, M.; Yankson, B. Predicting the occurrence of a data breach. International Journal of Information Management Data Insights 2022, 2, 100128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reegu, F.A.; et al. Interoperability Requirements for Blockchain-Enabled Electronic Health Records in Healthcare: A Systematic Review and Open Research Challenges. Secur. Commun. Networks 2022, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reegu, F.A.; Abas, H.; Gulzar, Y.; Xin, Q.; Alwan, A.A.; Jabbari, A.; Sonkamble, R.G.; Dziyauddin, R.A. Blockchain-Based Framework for Interoperable Electronic Health Records for an Improved Healthcare System. Sustainability 2023, 15, 6337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).