1. Introduction

Inflammation is a complex biological response triggered by harmful stimuli such as injuries, infections, pathogens, and other foreign substances. The organism responds to these stimuli through a coordinated mechanism that involves the elimination of pathogenic factors and the activation of protective systems for self-repair and immune defense [

1].

At the tissue level, inflammation manifests through redness, swelling, heat, pain, and loss of tissue function—hallmarks resulting from local immune, vascular, and cellular inflammatory responses to infection or injury [

2]. Microcirculatory events occurring during the inflammatory process include increased vascular permeability, recruitment and accumulation of leukocytes, and the release of inflammatory mediators [

3,

4].

In certain diseases, the immune system triggers an inflammatory response in the absence of foreign substances or infection. These heterogeneous conditions are characterized by the excessive production of pro-inflammatory cytokines, including interleukin-1β (IL-1β) and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) [

5].

The inflammatory response involves the coordinated activation of signaling pathways that regulate the levels of inflammatory mediators in both tissue-resident and immune cells. Inflammation is a common pathogenic mechanism in many chronic diseases, including cardiovascular and gastrointestinal disorders, diabetes, arthritis, and malignancies [

6]. Although the specific features of the inflammatory response depend on the nature and location of the initial stimulus, these processes share a common mechanism that can be summarized as follows: (1) cell surface receptors recognize harmful stimuli; (2) inflammatory pathways are activated; (3) inflammatory markers are released; and (4) immune cells are recruited to the affected site [

7].

Synthetic anti-inflammatory drugs are widely used to suppress or inhibit pro-inflammatory mediators. However, the use of such medications is often associated with adverse side effects, such as gastric and duodenal ulcerations, which can reduce patient adherence to prescribed therapies. For this reason, in recent years, natural products have received increasing attention for their potential anti-inflammatory effects [

8].

Terpenes constitute a large and structurally diverse group of natural compounds synthesized by plants [

9]. This family comprises approximately 55,000 compounds with varying chemical structures and, consequently, distinct biological functions. Evidence from the scientific literature indicates that terpenoids can modulate the inflammatory process by inhibiting various molecular pathways, suggesting their potential as anti-inflammatory agents [

10].

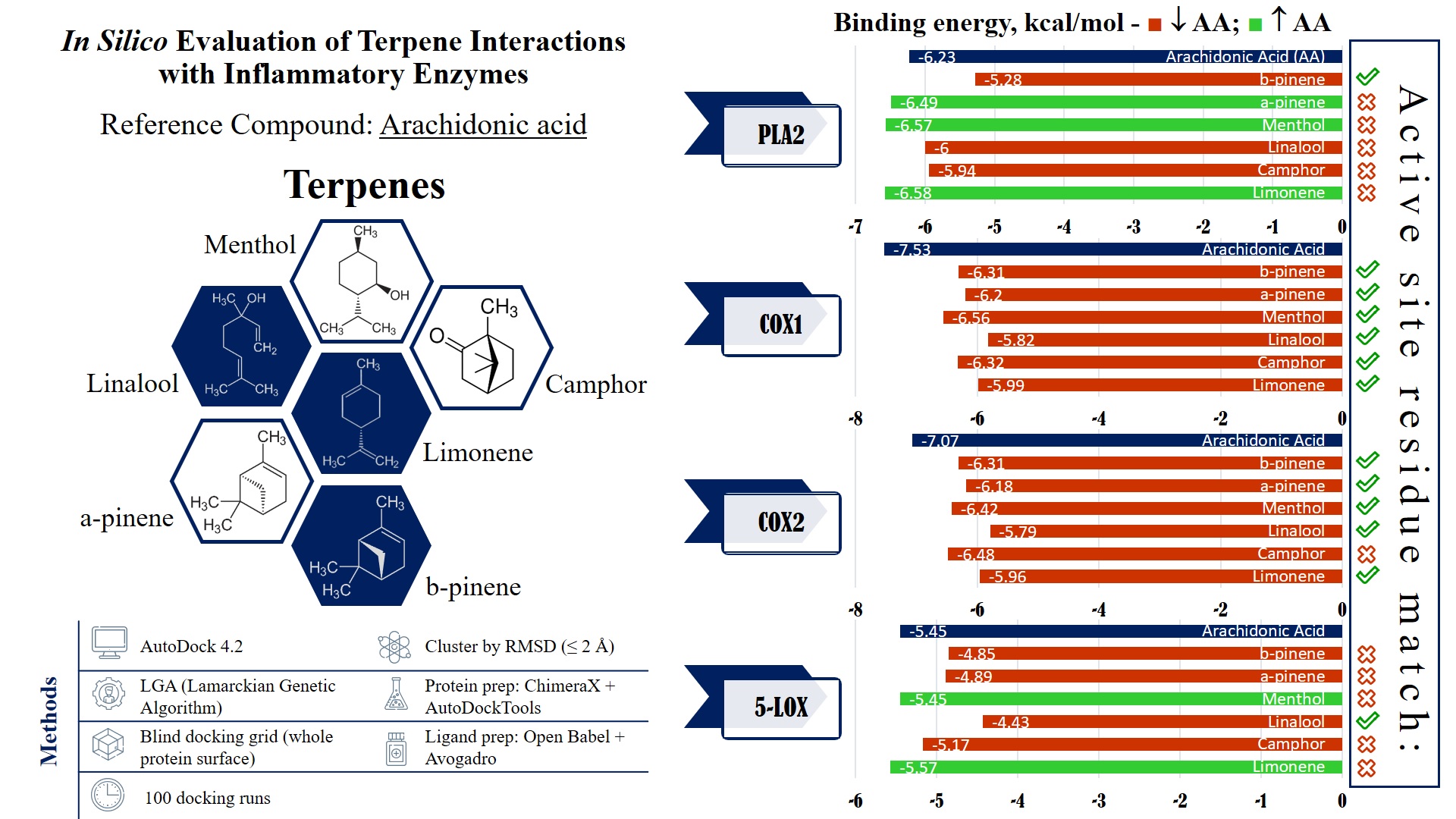

The aim of the present study is to evaluate the in silico anti-inflammatory potential of six terpenes—α-pinene, β-pinene, menthol, camphor, limonene, and linalool—by performing molecular docking analysis of their interactions with key enzymes involved in the inflammatory cascade: cyclooxygenase-1 (COX-1), cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2), phospholipase A2 (PLA2), and 5-lipoxygenase (5-LOX).

3. Results

3.1. COX-1 interactions

The interaction parameters of the selected terpenes with COX-1, compared to arachidonic acid (AA), are summarized in

Table 1.

One of the fundamental parameters for evaluating ligand–enzyme interactions is the binding energy, expressed in kcal/mol. Lower binding energy values correlate with the formation of more stable ligand–enzyme complexes, which, in turn, indicate higher binding affinity.

In the present study, AA exhibits the lowest binding energy (−7.53 kcal/mol), reflecting its strong interaction with COX-1. Among the terpenes analyzed, menthol has the lowest binding energy (−6.56 kcal/mol), followed by camphor (−6.32 kcal/mol) and β-pinene (−6.31 kcal/mol), suggesting that these compounds possess relatively high affinity for COX-1.

The inhibition constant (Ki) represents another indicator of the potential inhibitory activity of the studied molecules, with lower Ki values corresponding to greater inhibitory potential. The lowest Ki value is observed for AA (3.02 µM), consistent with its role as the natural substrate of COX-1. Among the terpenes, menthol (15.50 µM) and camphor (23.37 µM) exhibit the lowest Ki values, suggesting that these compounds may exert inhibitory activity toward the enzyme.

The root mean square deviation (RMSD) values, relative to the reference structure, provide insights into the extent of conformational changes undergone by the ligands upon binding. High RMSD values (>50 Å) are recorded for all analyzed molecules, indicating significant spatial reorientation. The highest RMSD values are observed for camphor (67.64 Å) and β-pinene (67.775 Å), suggesting that these molecules undergo substantial conformational changes upon binding to COX-1.

The total internal energy and torsional free energy provide additional insight into the molecular stability of the ligands. The highest torsional energy values are recorded for linalool (+1.49 kcal/mol) and AA (+4.47 kcal/mol), suggesting increased flexibility and a greater tendency for conformational changes. In contrast, menthol exhibits the lowest torsional energy (+0.60 kcal/mol), indicating a relatively stable conformation upon binding to COX-1.

Unbound energy is a parameter reflecting the energetic state of the molecule in its free form. The lowest unbound energy is observed for AA (−1.61 kcal/mol), consistent with its high binding affinity.

In summary, AA exhibits the highest affinity for COX-1, consistent with its role as the enzyme’s natural substrate. Among the terpenes investigated, menthol and camphor demonstrate the most favorable parameters, identifying them as potential COX-1 inhibitors. In contrast, linalool and α-pinene show relatively weaker interactions, likely due to their higher torsional energy and conformational flexibility.

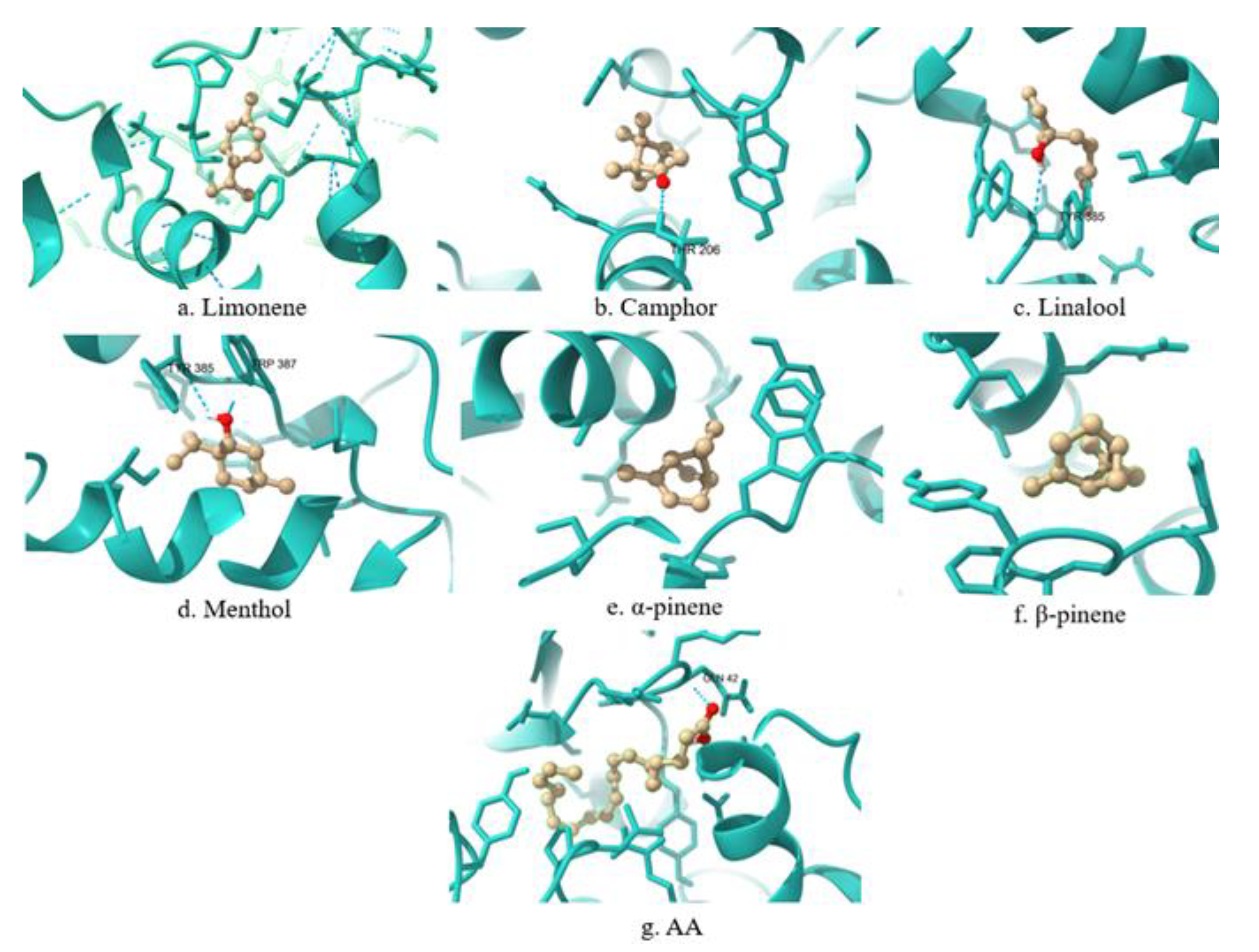

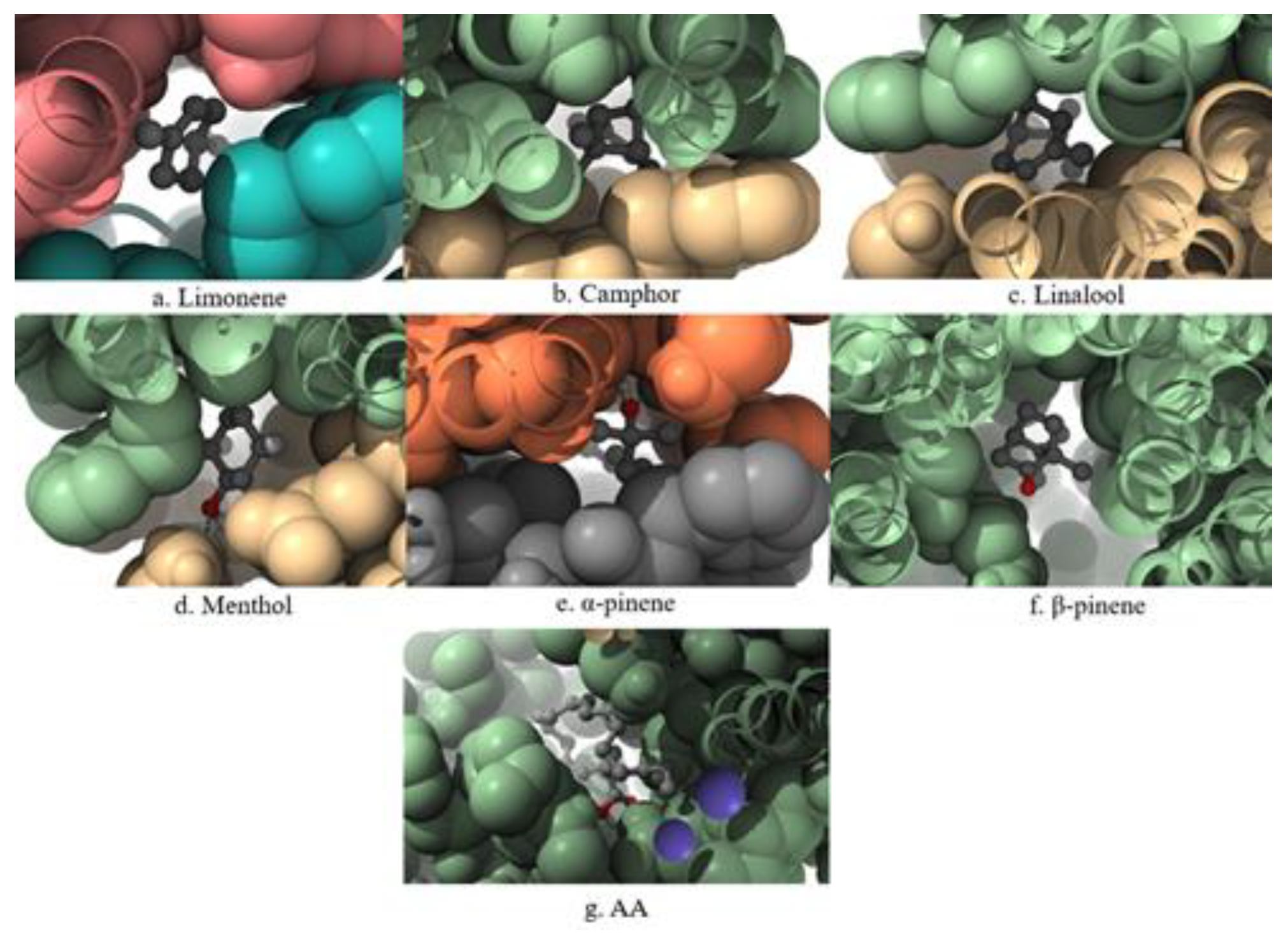

A 3D visualization of the interactions between the terpenes, AA, and the COX-1 enzyme is presented in

Figure 1. Ligands are shown in ball-and-stick representation (light brown), and the enzyme is displayed as a cartoon structure (cyan). Hydrogen bonds and relevant interactions are indicated with dashed lines where applicable. The positioning of each ligand relative to key catalytic residues illustrates potential binding modes and differences in spatial orientation.

3.2. COX-2 interactions

The interaction parameters of the selected terpenes with COX-2, compared to AA, are summarized in

Table 2.

AA exhibits the lowest binding energy (−7.07 kcal/mol), indicating strong interaction with COX-2. Among the terpenes analyzed, camphor has the lowest binding energy (−6.48 kcal/mol), followed by menthol (−6.42 kcal/mol).

The lowest Ki value is also observed for AA (6.55 µM), which is expected given its natural role in COX-2 enzymatic reactions. Among the terpenes, camphor (17.84 µM) and menthol (19.80 µM) exhibit the lowest Ki values, identifying them as potential COX-2 inhibitors.

The observed high RMSD values (>50 Å) for all analyzed molecules indicate significant spatial reorientation upon binding. The highest RMSD values are recorded for β-pinene (67.77 Å) and menthol (67.75 Å), suggesting substantial conformational changes during interaction with the enzyme.

Among all terpenes studied, the highest torsional energy is observed for linalool (+1.49 kcal/mol) and AA (+4.47 kcal/mol), indicating greater molecular flexibility. In contrast, α-pinene and β-pinene exhibit zero torsional energy (+0.00 kcal/mol), suggesting conformational stability upon binding.

The lowest unbound energy is recorded for AA (−1.18 kcal/mol), consistent with its high binding affinity.

The results indicate that, among all compounds studied, AA exhibits the highest affinity for COX-2, consistent with its role as the enzyme’s natural substrate. Among the terpenes, camphor and menthol demonstrate the most favorable parameters, identifying them as potential COX-2 inhibitors. In contrast, linalool and α-pinene show comparatively weaker interactions, likely due to their higher torsional energy and conformational flexibility.

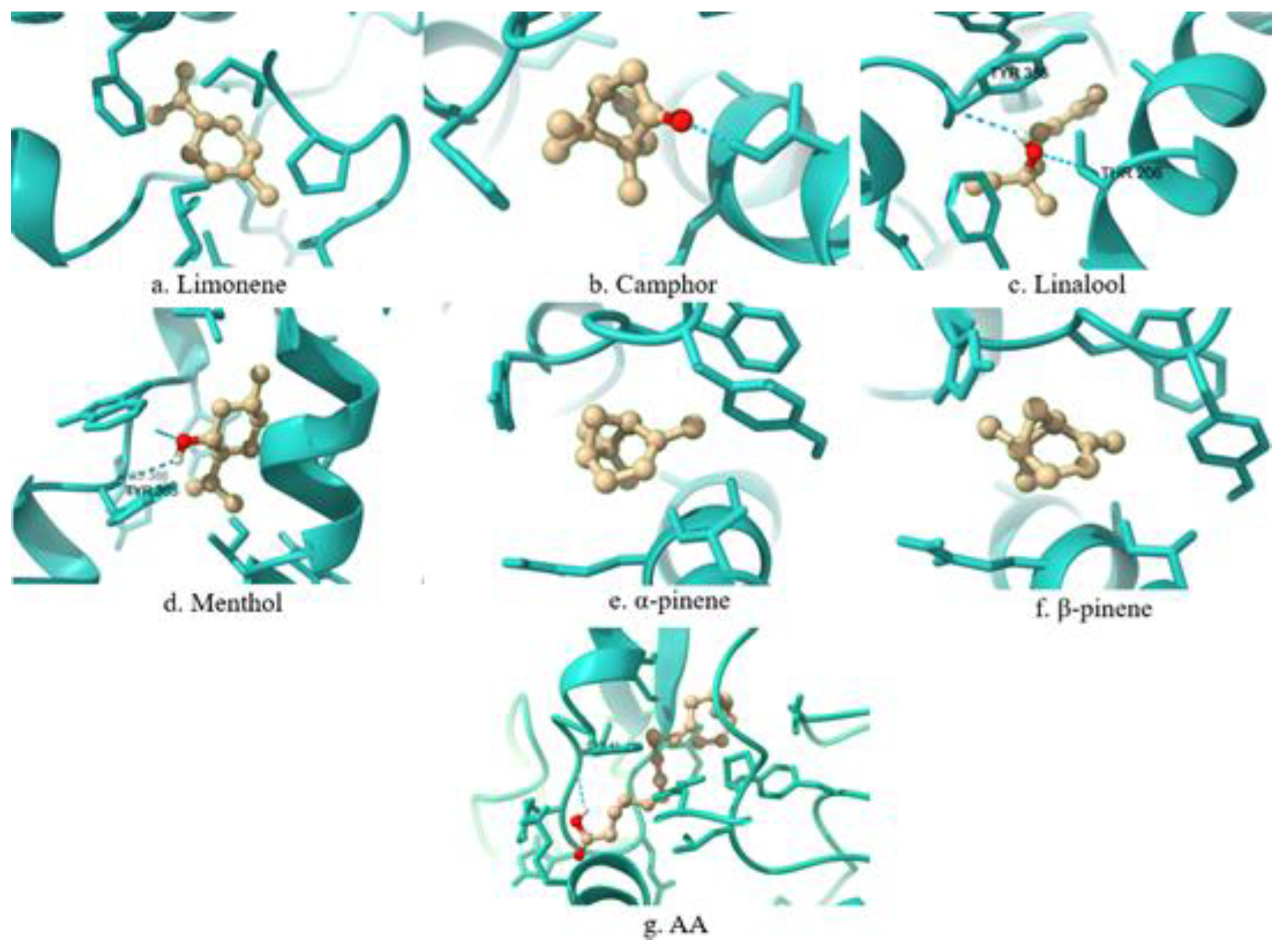

A 3D visualization of the interactions between the terpenes, AA, and the COX-2 enzyme is presented in

Figure 2. Ligands are shown in ball-and-stick representation (light brown), and the enzyme is displayed as a cartoon structure (cyan). Hydrogen bonds and relevant interactions are indicated with dashed lines where applicable. The positioning of each ligand relative to key catalytic residues illustrates potential binding modes and differences in spatial orientation.

3.3. 5-LOX interactions

The interaction parameters of the selected terpenes with 5-LOX, compared to AA, are summarized in

Table 3.

Limonene (−5.57 kcal/mol), menthol (−5.45 kcal/mol), and AA (−5.45 kcal/mol) exhibit the lowest binding energies, indicating stable interactions with 5-LOX. The remaining terpenes also demonstrate relatively favorable binding energies, with camphor displaying the highest value (−5.17 kcal/mol), which may suggest weaker interaction with the enzyme.

Limonene (82.28 µM), AA (101.13 µM), and menthol (102.00 µM) exhibit the lowest Ki values among the tested compounds, identifying them as the most promising potential 5-LOX inhibitors. In contrast, linalool shows a substantially higher Ki value (564.63 µM), indicating a significantly lower affinity for 5-LOX.

High RMSD values (>50 Å) are observed for camphor (77.022 Å) and limonene (64.854 Å), suggesting notable structural changes upon binding. Conversely, α-pinene (19.328 Å) and β-pinene (18.577 Å) demonstrate the lowest RMSD values, indicating minimal conformational changes during interaction with the enzyme.

Linalool (+1.49 kcal/mol) and AA (+4.47 kcal/mol) exhibit the highest torsional energies, suggesting greater conformational flexibility. In contrast, menthol (+0.60 kcal/mol) and α-pinene (+0.00 kcal/mol) show the lowest torsional energy values, indicating stable conformations upon binding to 5-LOX.

The lowest unbound energy is recorded for AA (−1.08 kcal/mol), supporting its high affinity for the enzyme.

The analysis reveals that limonene, menthol, and AA display the lowest binding energies, suggesting stable interactions with 5-LOX. Menthol and AA also demonstrate the lowest Ki values. In contrast, linalool exhibits the weakest affinity, suggesting lower inhibitory potential.

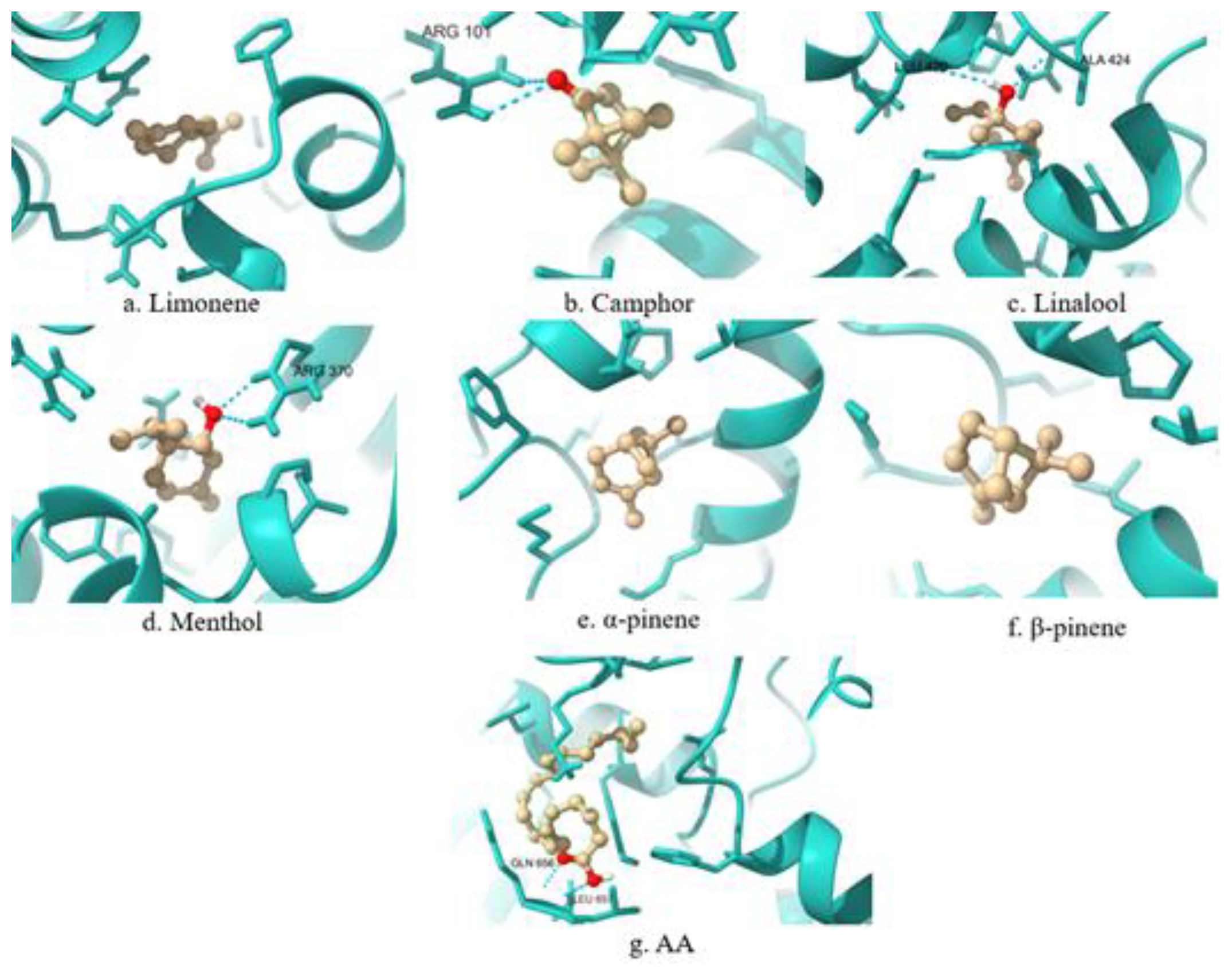

A 3D visualization of the interactions between the terpenes, AA, and the 5-LOX enzyme is presented in

Figure 3. Ligands are shown in ball-and-stick representation (light brown), and the enzyme is displayed as a cartoon structure (cyan). Hydrogen bonds and relevant interactions are indicated with dashed lines where applicable. The positioning of each ligand relative to key catalytic residues illustrates potential binding modes and differences in spatial orientation.

3.4. PLA2 interactions

The interaction parameters of the selected terpenes with PLA2, compared to AA, are summarized in

Table 4.

Limonene (−6.58 kcal/mol) exhibits the lowest binding energy, followed by menthol (−6.57 kcal/mol) and AA (−6.23 kcal/mol), indicating stable interactions with PLA2. The remaining terpenes also show good affinity, with β-pinene presenting the highest binding energy (−5.28 kcal/mol), which may indicate weaker interaction with the enzyme.

Among the terpenes, limonene (14.99 µM) and menthol (15.22 µM) exhibit the lowest Ki values, identifying them as the most promising potential inhibitors of PLA2. In contrast, β-pinene shows the highest Ki value (134.07 µM), indicating a weaker affinity for the enzyme.

High RMSD values are recorded for camphor (96.944 Å), linalool (96.905 Å), and menthol (98.205 Å), suggesting significant structural changes upon binding to PLA2. Notably, α-pinene (110.729 Å) and β-pinene (100.997 Å) exhibit the highest RMSD values, indicating pronounced flexibility during interaction.

The highest torsional energies are observed for α-pinene (+1.49 kcal/mol) and AA (+4.47 kcal/mol), suggesting greater conformational flexibility. In contrast, menthol (+0.60 kcal/mol) and limonene (+0.26 kcal/mol) display lower torsional energies, which may indicate more stable conformations when bound to PLA2.

AA exhibits the lowest unbound energy (−1.91 kcal/mol), consistent with its high affinity for PLA2. It is followed by α-pinene (−0.26 kcal/mol) and menthol (−0.17 kcal/mol).

The analysis reveals that limonene and menthol have the lowest binding energies, suggesting stable interactions with PLA2. These two compounds also demonstrate the lowest Ki values, identifying them as potential inhibitors of the enzyme. In contrast, β-pinene shows the weakest affinity, likely due to its high Ki value.

A 3D visualization of the interactions between the terpenes, AA, and the PLA2 enzyme is presented in

Figure 4. Ligands are shown in ball-and-stick format, surrounded by a space-filling surface representation of the protein to illustrate spatial accommodation and surface contact. The visualization highlights the degree of penetration and positioning of each ligand within the catalytic pocket of PLA₂.

3.5. Blind docking results

Table 5 presents the amino acid sequences of the active sites of the enzymes investigated in this study.

Table 6 presents the results of the blind docking analysis of the interactions between the selected terpenes and the enzymes involved in arachidonic acid metabolism. For comparative evaluation, arachidonic acid was included as a reference ligand. The table lists the amino acid residues involved in ligand–enzyme interactions as predicted by molecular docking, along with a comparison to known catalytic residues (“Match”). “Match” refers to overlap between contact residues and literature-defined catalytic residues for each enzyme, suggesting potential for functional inhibition.

For each ligand–enzyme complex, the following parameters were determined:

Active site sequence: A list of amino acid residues forming the catalytic site of the corresponding enzyme.

Binding residues: Specific residues through which the terpene establishes contact with the enzyme during docking.

Matches: Residues that appear most frequently across simulations, indicating potentially stable interactions and playing a key role in stabilizing the complex.

The data indicate that the terpenes interact selectively with the enzymes involved in arachidonic acid metabolism, establishing specific contacts within their active sites.

COX-1 is a constitutively expressed enzyme involved in the synthesis of prostaglandins essential for maintaining gastrointestinal and renal homeostasis. The analysis reveals that key contact residues within the active site include LEU117, ARG120, PHE205, PHE209, TYR348, PHE381, TYR385, and HIS388. Limonene forms a stable contact with PHE381, a residue within the active site. Camphor, linalool, menthol, α-pinene, and β-pinene exhibit strong interactions with HIS388 and TYR385, which may contribute to their affinity for the enzyme. Additionally, α-pinene and β-pinene interact with TRP387, which could play a stabilizing role in ligand binding.

COX-2 is inducible under inflammatory conditions and is a preferred target for selective inhibitors. The primary amino acid residues involved in terpene interactions include TYR385, HIS388, TRP387, PHE381, and VAL349. Limonene again shows affinity for PHE381. In the case of camphor, no overlap can be observed between the ligand–enzyme interaction residues and the active site residues of COX-2. Linalool, menthol, α-pinene, and β-pinene demonstrate stable binding with HIS388 and TYR385, consistent with the patterns observed for COX-1. α-Pinene and β-pinene also exhibit specific affinity for TRP387, which may influence their selectivity toward COX-2.

5-LOX catalyzes the first step in leukotriene biosynthesis, which plays a critical role in chronic inflammatory diseases. The key amino acid residues involved in ligand binding include HIS367, HIS372, HIS550, TYR181, and TRP599. Among the tested compounds, only linalool shows stable contacts with LEU414, TRP599, ALA603 and TYR181, which overlap with its interaction profile in COX-2. For the remaining terpenes, no overlap is observed between the ligand–enzyme interaction residues and the amino acid sequence of the 5-LOX active site.

PLA₂ is responsible for releasing AA from membrane phospholipids, representing the initial step in the inflammatory cascade. The main contact residues in the enzyme’s active site include HIS47, CYS44, TYR51, and PHE5. Among the terpenes, only β-pinene exhibits matching interactions, forming stable contacts with PHE5, CYS44, and HIS47, which are part of the active site of the phospholipase enzyme.

4. Discussion

In the present study, the anti-inflammatory properties of six terpenes are evaluated in silico through molecular docking against four enzymes involved in the inflammatory cascade. Arachidonic acid is used as a reference substrate, as it is the natural ligand for these enzymes and plays a central role in the synthesis of pro-inflammatory mediators.

The results show that for both COX-1 and COX-2, AA exhibits the lowest binding energy and Ki values, confirming its optimal positioning within the catalytic site. Among the terpenes studied, menthol and camphor show a tendency to bind near critical catalytic residues, although they do not achieve the full interaction profile characteristic of AA. This is reflected in their higher Ki values, suggesting that despite thermodynamically favorable docking scores, their overall affinity for COX-1 and COX-2 remains lower than that of the natural substrate.

In contrast, a different pattern is observed in the analysis of 5-LOX and PLA₂. Limonene and menthol can be positioned in close proximity to key catalytic residues essential for enzymatic function, which is supported by their favorable binding energy and Ki values. This suggests that they may exert a competitive effect by hindering the normal binding and function of AA within the active sites. Such positioning, combined with their relatively low torsional free energy—indicating more stable conformations upon binding—highlights their potential as inhibitors of 5-LOX and PLA₂.

Although cluster analysis is performed using a 2 Å RMSD threshold to group geometrically similar poses, certain high-RMSD docking results are retained for further evaluation due to their interactions with catalytically important residues reported in the literature. This strategy ensures that biologically relevant binding modes were not disregarded solely on the basis of geometric deviation. A comprehensive analysis of conformational parameters, including RMSD values and torsional free energy, indicate that many ligands undergo notable structural rearrangements upon enzyme binding. In particular, linalool and arachidonic acid exhibit higher torsional energies, suggesting a greater degree of conformational flexibility and the potential to adopt multiple orientations within the active site. Conversely, the lower torsional energies which are observed for limonene and menthol point to more rigid and stable binding poses, a feature that may contribute to more effective inhibition of enzymatic activity.

Despite these encouraging in silico results, it is important to acknowledge the limitations of the molecular docking approach. The rigid protein structures used during docking do not fully reflect the dynamic flexibility of enzymes, and conformational changes associated with the induced fit mechanism remain unresolved. Additionally, factors such as solvent effects, entropic contributions, and the specific ionization states of catalytic residues cannot be fully captured by docking algorithms. These limitations warrant caution when extrapolating in silico findings to actual biological activity.

The comparison of ligand–residue contacts with literature-defined catalytic residues provides additional insight into whether the ligand is positioned in close proximity to the enzyme’s functional center. In cases where a high degree of overlap is observed, lower binding energy and Ki values are typically recorded, supporting the conclusion that these interactions are not incidental, but reflect a real mechanism of enzymatic inhibition.

The observed interactions between the docked terpenoid compounds and key active site residues—previously identified as critical for arachidonic acid binding—suggest a potential for these molecules to interfere with the enzyme’s ability to process arachidonic acid. This supports the hypothesis that such terpenes may modulate the arachidonic acid metabolic pathway, potentially contributing to anti-inflammatory effects.

For COX-1 and COX-2, AA - despite its thermodynamically favorable binding profile—did not always align fully with key catalytic residues, which may be attributed to conformational characteristics of the selected protein structure. In contrast, limonene and menthol demonstrate more precise positioning within critical regions of 5-LOX and PLA₂, supporting their candidacy as potential inhibitors in these systems.

In addition to analyzing binding energies and Ki values, the structure–activity relationship between molecular parameters and the ability to establish contacts with amino acid residues proves to be particularly important in evaluating terpene potential. Molecules that fail to reach the active site, or that interact only peripherally, are likely to exhibit weaker inhibitory effects—even if their thermodynamic parameters appear favorable.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.I and D.C; methodology, I.I., D.C., N.A., G.Y., T.D., N.A. and S.G.; software, I.I. and K.M.; validation, I.I., and D.C; formal analysis, I.I. and D.C.; investigation, I.I. and D.C; resources, I.I., D.C., K.M., N.A., G.Y. T.D. and S.G.; data curation, I.I. and D.C.; writing—original draft preparation, I.I. and D.C.; writing—review and editing, G.Y. and S.G.; visualization, I.I. and K.M.; supervision G.Y. and S.G.; project administration, D.C.; funding acquisition, G.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Figure 1.

Comparative 3D visualization of the binding interactions between selected terpenes, arachidonic acid (AA), and the COX-1 enzyme.

Figure 1.

Comparative 3D visualization of the binding interactions between selected terpenes, arachidonic acid (AA), and the COX-1 enzyme.

Figure 2.

Comparative 3D visualization of the binding interactions between selected terpenes, arachidonic acid (AA), and the COX-2 enzyme.

Figure 2.

Comparative 3D visualization of the binding interactions between selected terpenes, arachidonic acid (AA), and the COX-2 enzyme.

Figure 3.

Comparative 3D visualization of the binding interactions between selected terpenes, arachidonic acid (AA), and the 5-LOX enzyme.

Figure 3.

Comparative 3D visualization of the binding interactions between selected terpenes, arachidonic acid (AA), and the 5-LOX enzyme.

Figure 4.

Comparative 3D visualization of the binding interactions between selected terpenes, arachidonic acid (AA), and the PLA2 enzyme.

Figure 4.

Comparative 3D visualization of the binding interactions between selected terpenes, arachidonic acid (AA), and the PLA2 enzyme.

Table 1.

In silico docking results for interactions between selected terpenes and COX-1: binding energy, conformational parameters, inhibition constants (Ki), and energy descriptors compared to arachidonic acid (AA).

Table 1.

In silico docking results for interactions between selected terpenes and COX-1: binding energy, conformational parameters, inhibition constants (Ki), and energy descriptors compared to arachidonic acid (AA).

| COX-1 |

Limonene |

Camphor |

Linalool |

Menthol |

α-pinene |

β-pinene |

AA |

| Conformations |

2 |

13 |

33 |

20 |

54 |

60 |

9 |

| RMSD from reference structure |

59.121 A |

67.643 A |

66.924 A |

67.481 A |

66.995 A |

67.775 A |

57.255 A |

| Binding energy |

-5.99 kcal/mol |

-6.32 kcal/mol |

-5.82 kcal/mol |

-6.56 kcal/mol |

-6.20 kcal/mol |

-6.31 kcal/mol |

-7.53 kcal/mol |

| Inhibition Constant, Ki |

40.60 µM |

23.37 µM |

54.64 µM |

15.50 µM |

28.74 µM |

23.61 µM |

3.02 µM |

| Total Internal energy |

-0.13 kcal/mol |

+0.00 kcal/mol |

-0.33 kcal/mol |

-0.17 kcal/mol |

+0.00 kcal/mol |

+0.00 kcal/mol |

-1.61 kcal/mol |

| Torsional Free Energy |

+0.30 kcal/mol |

+0.00 kcal/mol |

+1.49 kcal/mol |

+0.60 kcal/mol |

+0.00 kcal/mol |

+0.00 kcal/mol |

+4.47 kcal/mol |

| Unbound Energy |

-0.13 kcal/mol |

+0.00 kcal/mol |

-0.33 kcal/mol |

-0.17 kcal/mol |

+0.00 kcal/mol |

+0.00 kcal/mol |

-1.61 kcal/mol |

Table 2.

In silico docking results for interactions between selected terpenes and COX-2: binding energy, conformational parameters, inhibition constants (Ki), and energy descriptors compared to arachidonic acid (AA).

Table 2.

In silico docking results for interactions between selected terpenes and COX-2: binding energy, conformational parameters, inhibition constants (Ki), and energy descriptors compared to arachidonic acid (AA).

| COX-2 |

Limonene |

Camphor |

Linalol |

Menthol |

α-pinene |

β-pinene |

AA |

| Conformations |

3 |

13 |

19 |

26 |

36 |

46 |

7 |

| RMSD from reference structure |

59.204 A |

67.674 A |

66.971 A |

67.752 A |

67.087 A |

67.770 A |

58.016 A |

| Binding energy |

-5.96 kcal/mol |

-6.48 kcal/mol |

-5.79 kcal/mol |

-6.42 kcal/mol |

-6.18 kcal/mol |

-6.31 kcal/mol |

-7.07 kcal/mol |

| Inhibition Constant, Ki |

43.00 µM |

17.84 µM |

56.61 µM |

19.80 µM |

29.44 µM |

23.61 µM |

6.55 µM |

| Total Internal energy |

-0.13 kcal/mol |

+0.00 kcal/mol |

-0.37 kcal/mol |

-0.16 kcal/mol |

+0.00 kcal/mol |

+0.00 kcal/mol |

-1.18 kcal/mol |

| Torsional Free Energy |

+0.30 kcal/mol |

+0.00 kcal/mol |

+1.49 kcal/mol |

+0.60 kcal/mol |

+0.00 kcal/mol |

+0.00 kcal/mol |

+4.47 kcal/mol |

| Unbound Energy |

-0.13 kcal/mol |

+0.00 kcal/mol |

-0.37 kcal/mol |

-0.16 kcal/mol |

+0.00 kcal/mol |

+0.00 kcal/mol |

-1.18 kcal/mol |

Table 3.

In silico docking results for interactions between selected terpenes and 5-LOX: binding energy, conformational parameters, inhibition constants (Ki), and energy descriptors compared to arachidonic acid (AA).

Table 3.

In silico docking results for interactions between selected terpenes and 5-LOX: binding energy, conformational parameters, inhibition constants (Ki), and energy descriptors compared to arachidonic acid (AA).

| 5-LOX |

Limonene |

Camphor |

Linalool |

Menthol |

α-pinene |

β-pinene |

AA |

| Conformations |

15 |

13 |

1 |

14 |

32 |

26 |

1 |

| RMSD from reference structure |

64.854 A |

77.022 A |

23.527 A |

64.372 A |

19.328 A |

18.577 A |

28.948 A |

| Binding energy |

-5.57 kcal/mol |

-5.17 kcal/mol |

-4.43 kcal/mol |

-5.45 kcal/mol |

-4.89 kcal/mol |

-4.85 kcal/mol |

-5.45 kcal/mol |

| Inhibition Constant, Ki |

82.28 µM |

161.15 µM |

564.63 µM |

102.00 µM |

261.53 µM |

280.35 µM |

101.13 µM |

| Total Internal energy |

-0.13 kcal/mol |

+0.00 kcal/mol |

-0.39 kcal/mol |

-0.16 kcal/mol |

+0.00 kcal/mol |

+0.00 kcal/mol |

-1.08 kcal/mol |

| Torsional Free Energy |

+0.30 kcal/mol |

+0.00 kcal/mol |

+1.49 kcal/mol |

+0.60 kcal/mol |

+0.00 kcal/mol |

+0.00 kcal/mol |

+4.47 kcal/mol |

| Unbound Energy |

-0.13 kcal/mol |

+0.00 kcal/mol |

-0.39 kcal/mol |

-0.16 kcal/mol |

+0.00 kcal/mol |

+0.00 kcal/mol |

-1.08 kcal/mol |

Table 4.

In silico docking results for interactions between selected terpenes and PLA2: binding energy, conformational parameters, inhibition constants (Ki), and energy descriptors compared to arachidonic acid (AA).

Table 4.

In silico docking results for interactions between selected terpenes and PLA2: binding energy, conformational parameters, inhibition constants (Ki), and energy descriptors compared to arachidonic acid (AA).

| PLA2 |

Limonene |

Camphor |

Linalool |

Menthol |

α-pinene |

β-pinene |

AA |

| Conformations |

19 |

6 |

11 |

6 |

8 |

25 |

2 |

| RMSD from reference structure |

89.108 A |

96.944 A |

96.905 A |

98.205 A |

110.729 A |

100.997 A |

98.253 A |

| Binding energy |

-6.58 kcal/mol |

-5.94 kcal/mol |

-6.00 kcal/mol |

-6.57 kcal/mol |

-6.49 kcal/mol |

-5.28 kcal/mol |

-6.23 kcal/mol |

| Inhibition Constant, Ki |

14.99 µM |

44.43 µM |

39.77 µM |

15.22 µM |

17.50 µM |

134.07 µM |

27.27 µM |

| Total Internal energy |

-0.13 kcal/mol |

+0.00 kcal/mol |

+0.00 kcal/mol |

-0.17 kcal/mol |

-0.26 kcal/mol |

+0.00 kcal/mol |

-1.91 kcal/mol |

| Torsional Free Energy |

+0.30 kcal/mol |

+0.00 kcal/mol |

+0.00 kcal/mol |

+0.60 kcal/mol |

+1.49 kcal/mol |

+0.00 kcal/mol |

+4.47 kcal/mol |

| Unbound Energy |

-0.13 kcal/mol |

+0.00 kcal/mol |

+0.00 kcal/mol |

-0.17 kcal/mol |

-0.26 kcal/mol |

+0.00 kcal/mol |

-1.91 kcal/mol |

Table 5.

Active site amino acid residues in COX-1, COX-2, 5-LOX and PLA2 enzymes.

Table 5.

Active site amino acid residues in COX-1, COX-2, 5-LOX and PLA2 enzymes.

| Enzyme |

Active Site |

Bibliography |

| COX-1 |

LEU117, ARG120, PHE205, PHE209, VAL344, ILE345, TYR348, VAL349, LEU352, SER353, TYR355, PHE381, TYR385, TRP387, ILE523, HIS207, HIS388, GLN203 |

[11] |

| COX-2 |

TYR385, SER530, LEU531, VAL116, ALA527, VAL349, TYR355, LEU352, VAL523, PHE518, PHE205, PHE209, TYR348, VAL349, LEU352, PHE381, TYR385, TRP387, VAL523, ALA527, LEU534 |

[12] |

| 5-LOX |

HIS367, HIS372, HIS550, PHE177, TYR181, LEU368, LEU414, ILE406, ALA603, ALA606, TRP599, ASN407, HIS432 |

[13] |

| PLA2

|

PHE5, HIS6, ILE9, ALA18, TYR21, GLY22, GLY29, GLY32, CYS44, HIS47, TYR51 |

[14] |

Table 6.

Interaction profile of selected terpenes and arachidonic acid (AA) with the active sites of COX-1, COX-2, 5-LOX, and PLA₂ enzymes.

Table 6.

Interaction profile of selected terpenes and arachidonic acid (AA) with the active sites of COX-1, COX-2, 5-LOX, and PLA₂ enzymes.

| Terpene |

Enzyme |

Interaction |

Match |

| Limonene |

COX-1 |

PRO128, ARG376, PRO125, ALA378, ILE124, ILE377, PHE529, PHE381, LYS532 |

PHE381 |

| COX-2 |

PRO125, PRO128, ARG376, ILE124, ILE377, PHE529, LYS532, ALA378, PHE381 |

PHE381 |

| 5-LOX |

LEU448, TYR470, ILE454, PHE450, VAL243, ALA453 |

No match. |

| PLA2

|

PHE63, LYS62, PHE63 |

No match. |

| Camphor |

COX-1 |

ALA202, LEU390, MET391, THR206, HIS388 |

HIS388 |

| COX-2 |

ALA202, HIS388, THR206, MET391, LEU390 |

No match. |

| 5-LOX |

HIS130, VAL110, VAL109, ARG101, LYS133 |

No match. |

| PLA2

|

LYS62, LEU64, PHE63, PHE63 |

No match. |

| Linalool |

COX-1 |

HIS388, HIS386, LEU390, TYR385, ALA202, PHE21 |

HIS388, TYR385 |

| COX-2 |

LEU390, MET391, ALA202, HIS388, HIS207, PHE210, HIS386, THR206, TYR385 |

TYR385 |

| 5-LOX |

PHE359, PHE412, LEU414, TRP599, VAL604, HIS600, ALA603, TYR181, LEU420, ALA424 |

LEU414, TRP599, ALA603, TYR181 |

| PLA2

|

LYS62, LEU64, LEU64, PHE63 |

No match. |

| Menthol |

COX-1 |

HIS388, TYR385, ALA202, MET391, LEU390, ALA199 |

HIS388, TYR385 |

| COX-2 |

HIS388, TYR385, ALA202, MET391, LEU390, ALA199 |

TYR385 |

| 5-LOX |

PHE544, PHE450, SER447, ARG370, ALA453, VAL243 |

No match. |

| PLA2

|

LEU64, THR61, LYS62, PHE63, PHE63 |

No match. |

| α-pinene |

COX-1 |

TYR385, LEU390, HIS388, MET391, ALA199, ALA202, TRP387 |

TYR385, HIS388, TRP387 |

| COX-2 |

ALA199, HIS388, TYR385, TRP387, LEU390, MET391, ALA202 |

TYR385, TRP387 |

| 5-LOX |

VAL645, LEU641, PRO664, LEU617, MET619, ARG638 |

No match. |

| PLA2

|

PHE63, THR61, PHE63, LYS62, LEU64 |

No match. |

| β-pinene |

COX-1 |

HIS388, LEU390, TYR385, TRP387, ALA202, MET391 |

TYR385, HIS388, TRP387 |

| COX-2 |

HIS388, LEU390, TYR385, TRP387, ALA202, MET391 |

TYR385, TRP387 |

| 5-LOX |

LEU641, LEU617, VAL645, PRO664, MET619, ARG638 |

No match. |

| PLA2

|

PHE98, PHE5, ALA94, HIS47, CYS28, CYS44 |

PHE5, CYS44, HIS47 |

| AA |

COX-1 |

CYS47, CYS36, PRO156, PRO153, TYR130, HIS43, ILE46, LYS468, CYS41, LEU152, ARG469, PRO40 |

No match. |

| COX-2 |

LEU152, TYR39, CYS47, CYS36, PRO156, PRO153, TYR130, ILE46, HIS43, CYS41 |

No match. |

| 5-LOX |

MET231, LEU230, LYS319, LEU237, GLN656, TYR234, LEU657 |

No match. |

| PLA2

|

HIS47, CYS28, HIS27, ASP48, GLY29, TYR51, LEU2, ALA17, PHE5, ILE9, TYR21, PHE98, CYS44 |

PHE5, ILE9, TYR21, GLY29, CYS44, HIS47, TYR51 |