1. Introduction

Titanium and titanium alloys are widely used in various fields of technology due to their unique properties but their production volumes are small due to high production costs. This is due to the relatively high cost of raw materials, the refractoriness of titanium alloys and the significant chemical activity of titanium melts during their production. Therefore, the production of titanium alloys requires special conditions for the preparation of charge, the use of energy-intensive furnaces that ensure the melting under vacuum conditions and in the absence of contact with refractory materials. It is achieved by the use of vacuum skull melting furnaces with electric arc or electron beam energy sources [

1]. At the same time, another problem is the production of titanium alloy castings in the alloy casting process. It is due to the high activity of melts resulting in the formation of an alpha case on the surface of the casting and the formation of pores and other defects caused by the interaction of the melt with the walls of the casting mold from the moment the melt is poured until it solidifies [

2]. As a consequence, there is a need to search for inert materials that do not actively interact with the titanium alloy during melting and casting. Therefore, today we need studies of the interaction processes occurring when liquid titanium comes into contact with refractory and molding materials.

For many decades, studies have been conducted to find materials that are inert or relatively inert to titanium melts [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21]. The interaction of titanium melts with a variety of simple and complex oxides, nitrides, carbides and graphite is studied within the framework of these studies. However, all these materials still cause an interfacial reaction, and the reaction between graphite and titanium alloy results in carburization and the formation of a carbonized layer that includes a carbon-rich brittle phase [

3,

4,

5,

6].

The paper [

2] gives a review for selection of various materials intended for melting of titanium alloys and shows that relatively stable materials are oxides—Y

2O

3, CaZrO

3, BaZrO

3, etc. It made it possible to propose the use of these compounds to line induction furnaces and to manufacture crucibles for the melting titanium alloys. However, Y

2O

3 ceramics, despite the best resistance to titanium melts, has a high cost and can be used only in low-tonnage production. Refractories and molding materials made of CaZrO

3, BaZrO

3 [

7,

8,

9,

10,

11] are economically more attractive, although their cost is also high.

In [

22], the manufacture of a (Ca,Sr,Ba)ZrO

3 crucible with slip casting methods for vacuum induction melting of NiTi alloy is presented. The presented crucible material sintering technology at 1500 °C results in a homogeneous distribution of elements. It was found after melting the titanium alloy in this crucible that the total oxygen and nitrogen content remaining in the TiNi alloy after (Ca,Sr,Ba)ZrO

3 crucible melting was 0.0173% wt%, that is in line with the ASTM standard for biomedical TiNi alloys. It is presented that the (Ca,Sr,Ba)ZrO

3 crucible stability to molten NiTi is related to the slow diffusion effect of high-entropy ceramics. And the authors propose this material as a potential crucible material for melting titanium alloys in a vacuum induction furnace.

However, as it is shown by studies [

12] CaZrO

3 in contact with titanium melt still interacts and causes contamination of titanium melt with zirconium and oxygen.

It is shown in the paper [

7] that titanium melt interacts well with the BaZrO

3 surface dissolving zirconium with oxygen, and also reduces barium to a metallic state. It calls the prospects of using these materials in lining and molding mixtures of the titanium industry into question. At the same time, the interaction of liquid titanium with BaZrO

3 and SrZrO

3 as well as SrTiO

3 titanate was considered in the same work [

7]. It is shown that titanium dissolves zirconium and oxygen and reduces barium and strontium to a metallic state in contact with these ceramic materials. Barium and strontium evaporate due to the high vapor pressure at the experimental temperature, and cause the melt to splash or form a vapor layer that reduces the interaction rate of the melt with the ceramic.

Considering the procedure for the selection and further use of potential materials for melting a particular titanium alloy, it should be noted that it is important to take several important aspects into account: the interaction of the material with the melt and the thermodynamics of the reactions involved, the melting and softening points of the refractory material, wettability and heat resistance [

2]. As a result, there is a need to study the processes of reaction diffusion and wetting that develop when titanium melts come into contact with the most inert materials, such as titanates and zirconates of alkaline, alkaline earth and rare-earth metals.

The works devoted to the general theory of wetting are extensive [

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21]. At the same time, metal wetting of ceramics is determined by two types of interactions occurring at the interface, leading to non-reactive wetting and reactive wetting [

9,

14]. Non-reactive wetting occurs in liquid/solid systems where mass transfer across the interface is very limited and has little effect on the interfacial energy. Wetting, involving the chemical alteration and/or diffusion of chemicals across the interface, is reactive wetting. It often occurs in metal/ceramic systems at high temperatures. However, only a small number of studies of interfacial phenomena and wettability of ceramic materials with titanium melts are reported in the literature.

For example, the wettability and interaction of pure liquid titanium and yttrium-stabilized zirconium dioxide with the lying drop method in an argon atmosphere at 1973 K were considered in [

14]. It is shown that interfacial reactions occur at high temperatures, and at the same time the wetting angle increases with an increase in the substrate porosity. The wetting angles turned out to be stable and exceed 90°.

Works on the effect of titanium on oxide wetting in such systems as Ni–Ti/Al

2O

3 [

23], Sn–Ti/Al

2O

3 are described in [

24]. The liquid wetting and spreading processes are considered in these works. The microstructure and properties of the transient layer of contact between ceramics and metal are built determining the properties of the system. It shows that there is a significant interaction between dissolved substances—O and Ti, causing adsorption of O–Ti clusters on the liquid side of the contact and the formation of metallic oxides, such as TiO, on the solid side of the contact interface [

25]. And it apparently leads to a decrease in the contact angle.

Meanwhile, the paper [

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12], [

26,

27,

28] considers the processes of interaction of liquid titanium with zirconates and titanates of some alkaline earth metals, but it does not consider the process of wetting.

Besides, the interaction of ceramics with titanium melt is described in the paper [

12], and it is shown that there are disadvantages of molding materials based on CaO and CaZrO

3 used to cast titanium alloys. It is shown that when titanium melt interacts with CaZrO

3, a highly porous CaTiO

3 layer is formed in the reaction zone, while zirconium dissolves in the melt. The authors suggest that CaTiO

3 can be used as a promising casting mold material to obtain castings from titanium alloys. Therefore, there is a need to study the interaction of titanium melt with CaTiO

3 ceramics and the wetting of its surface.

In this regard, the purpose of this paper is to consider the processes that develop when titanium melt comes into contact with calcium titanate by determining the wetting contact angle and studying the structure and distribution of elements in the transition zone.

2. Materials and Methods

It is known that the development of redox reactions and mutual diffusion is possible when titanates come into contact with titanium melt. As a result, new compounds in the form of single-phase, two-phase and three-phase layers can be formed at the interface of contact between the solid and liquid phases. The limiting number of phases in the layers forming the diffusion zone under conditions of isothermal interaction, as it is known, is determined by the state diagram of the system. Intermediate phases that can form in the diffusion zone can also be judged based on the analysis of state diagrams of the corresponding systems.

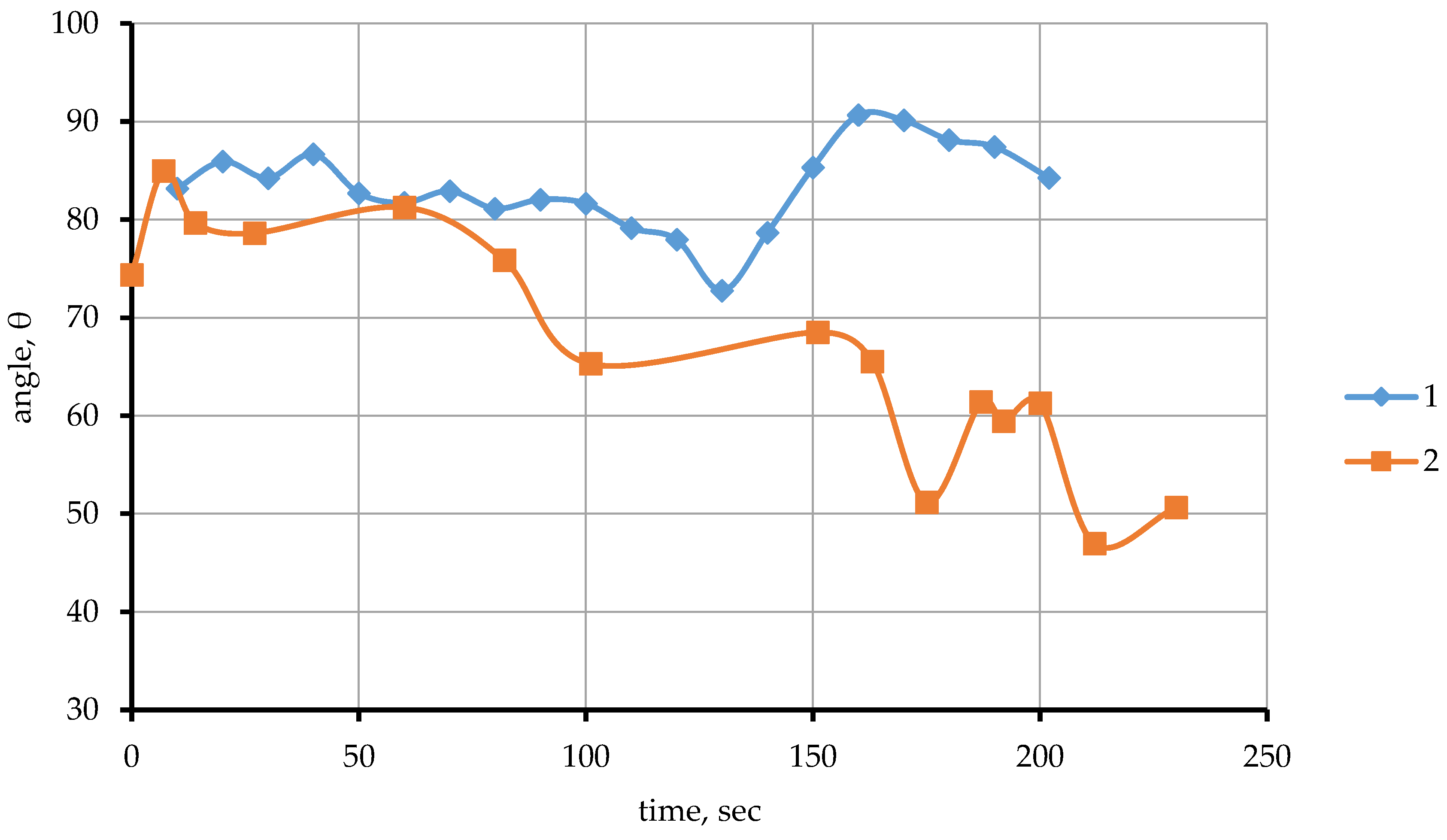

The change in Gibbs energy for reactions 1-3 were calculated to assess the possibility of interaction of titanium with calcium titanate. The “OUTOKUMPU HSC CHEMISTRY 8.0” was used for thermodynamic calculations. The results are presented in

Figure 1.

For reaction 1, the change in the Gibbs energy (∆G) in the temperature range from 1400 to 1800 °C is positive, hence the reaction cannot proceed directly. It may indicate that the reaction of calcium titanate with titanium occurs in two stages.

According to reaction 2, calcium titanate should dissociate with separation of TiO2 and its dissolution in the melt as a result of interaction with titanium melt. At the same time, a calcium oxide layer should be formed at the contact boundary. It will form a protective barrier that prevents further interaction due to the positive Gibbs energy according to reaction 3. It allows us to expect that calcium titanate CaTiO3 can be an effective material to produce new refractory and molding materials for melting and casting of titanium alloys. It is characterized with high moisture resistance, resistance to interaction with carbon dioxide and low production cost. It makes it necessary to study the mechanism of interaction of calcium titanate with titanium melt experimentally.

Calcium titanate substrates were synthesized for an experimental study to determine the wetting angle and to consider the interaction of titanium melt with calcium titanate.

The calcium titanate was synthesized with the liquid-phase method under reaction 4.

In the first step, a suspension was obtained by mixing CaCO

3 (99.9%) <20 μm and titanium oxide TiO

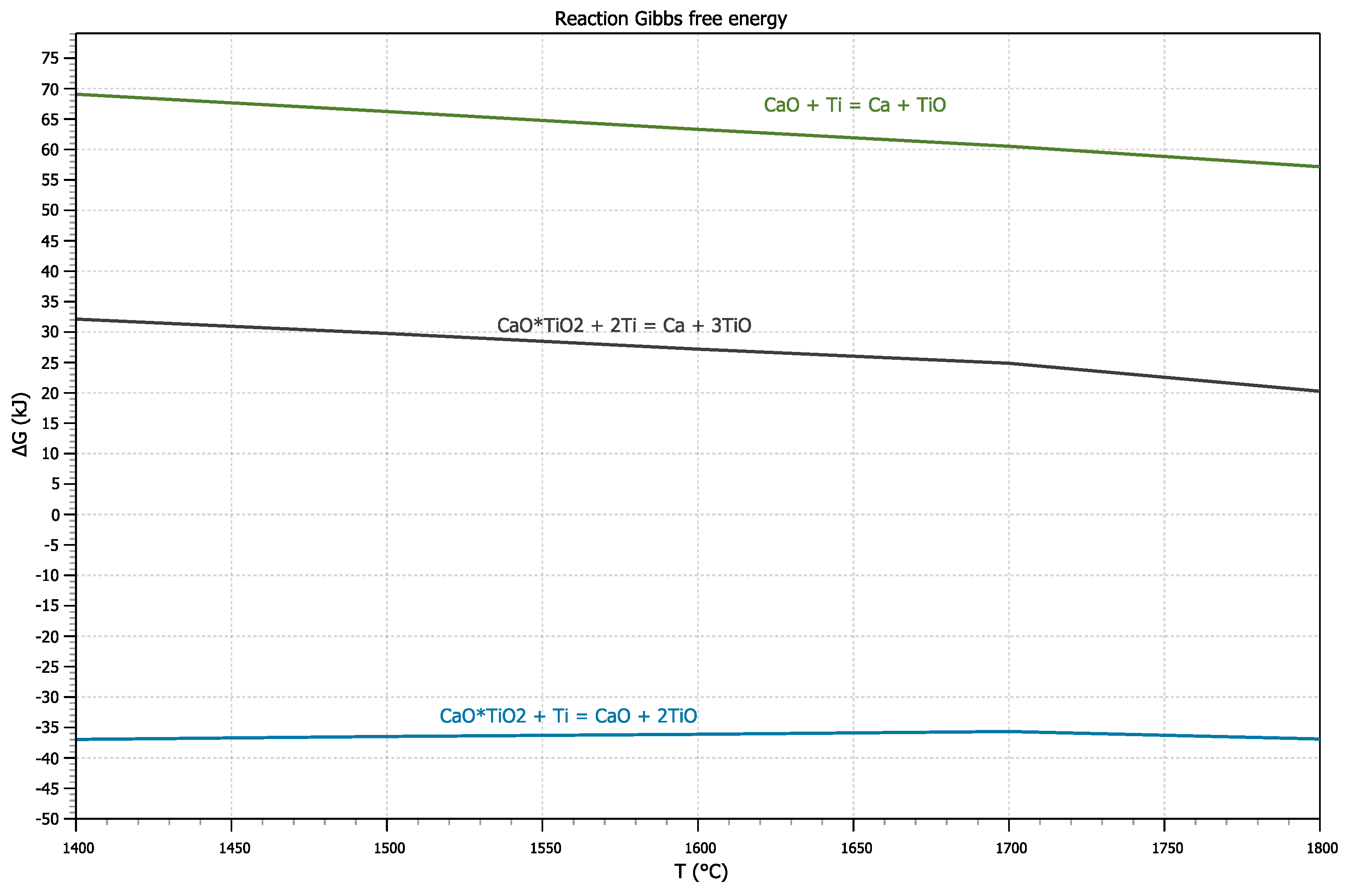

2 (99.5%) <10 μm powders in water at a S:L ratio of 1/2 for a long time. The suspension was dried in a drying oven and then melted in a two-electrode arc furnace. The resulting sintered materials were crushed and re-melted to achieve a homogeneous composition. The material obtained after double melting was crushed and sifted through a 120 μm sieve. The resulting powders were mixed with an aqueous solution of distillery sulfide stillage (SAS) added at the rate of 1% by weight. Tablets of ∅40 mm and a height of 5 mm were obtained from the mixture with a hydraulic press at a pressure of 2 MPa. These tablets were sintered at 1600 °C for 2 hours in a normal atmosphere in a RHTV 120-600/C 40 “Nabertherm” tube furnace. The phase composition of the obtained ceramic tablets was studied using the D8 Advance X-ray diffractometer (BRUKER). The results obtained (

Figure 2) confirm that the substrates are formed by CaTiO

3 monophase. The substrate surface was finished and polished before wetting experiments.

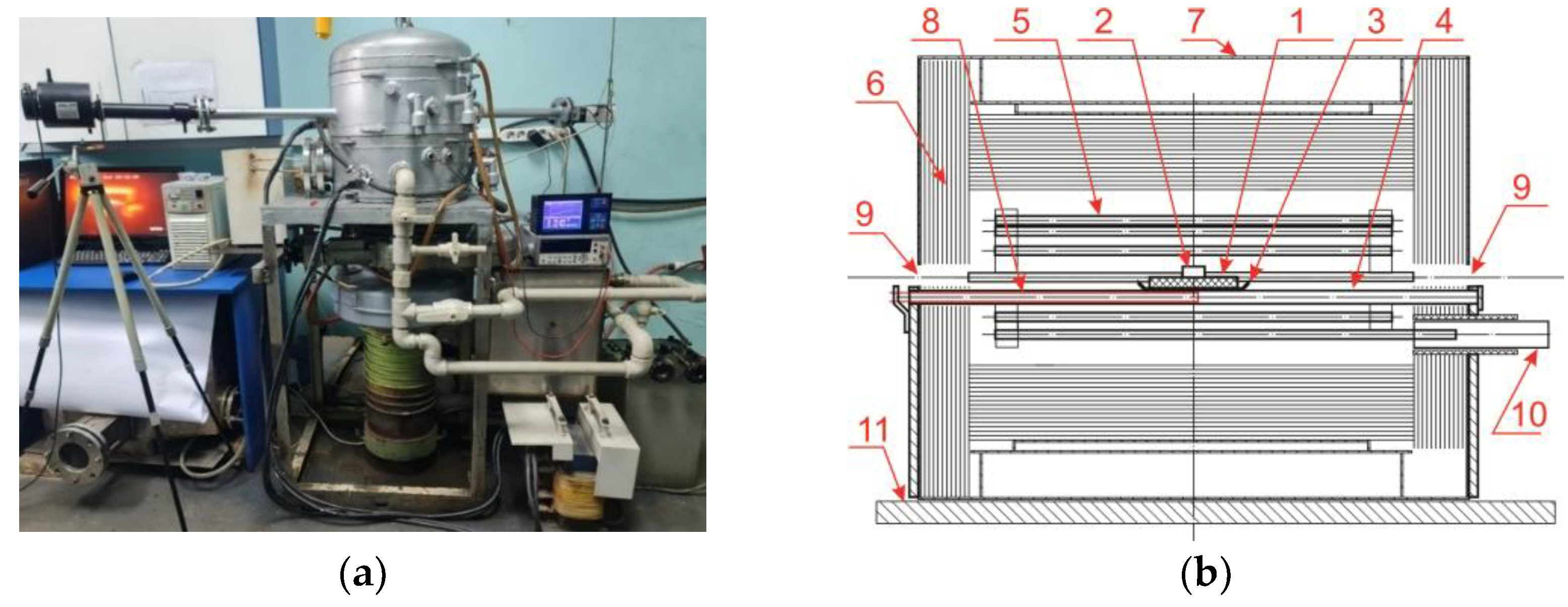

An experimental unit has been made to determine the parameters of wetting ceramic substrates with titanium melt (

Figure 3a). This unit provides heating of a ceramic substrate with a titanium alloy cylinder installed on its surface to a specified temperature, video recording of the process of spreading titanium melt on the surface of a ceramic sample in a horizontal projection. The heating process takes place under high vacuum conditions provided with a two-stage vacuum pumping system. During heating, the melt temperature is recorded using Thermoscope-800-2C-VT1, a stationary infrared pyrometer of spectral ratio.

A cylinder made of titanium alloy of the Grade 2, ∅10 mm and 5 mm high was installed in the center of the CaTiO

3 substrate. (

Figure 4)

The sample on a molybdenum pallet was then placed in the unit furnace to determine the wetting contact angle (

Figure 3b). When a residual pressure of 3-5*10

-4 mmHg was reached in the unit chamber the furnace was heated. A video recording was turned on at the beginning of titanium melting while the melt temperature was continuously recorded. When the specified temperature was reached, isothermal holding was conducted. At the end of the holding, the heating of the furnace was stopped, and the sample was cooled under conditions of continuous pumping to 50-100 °C.

When the wetting contact angle was measured, freeze frames of the video of the melt spreading process on the substrate were used. Measurements of the wetting contact angle were conducted using the ImageJ program. The contact zone structure of the melt and the ceramic substrate and the composition of the phases formed in it were studied using Leica DM IRM, an optical inverted microscope, and JEOL JXA-8230, an electron probe microanalyzer (Japan). These studies were conducted on transverse sections of the obtained samples.

3. Results

3.1. Study of Wetting of CaTiO3 Substrates with Titanium Melt

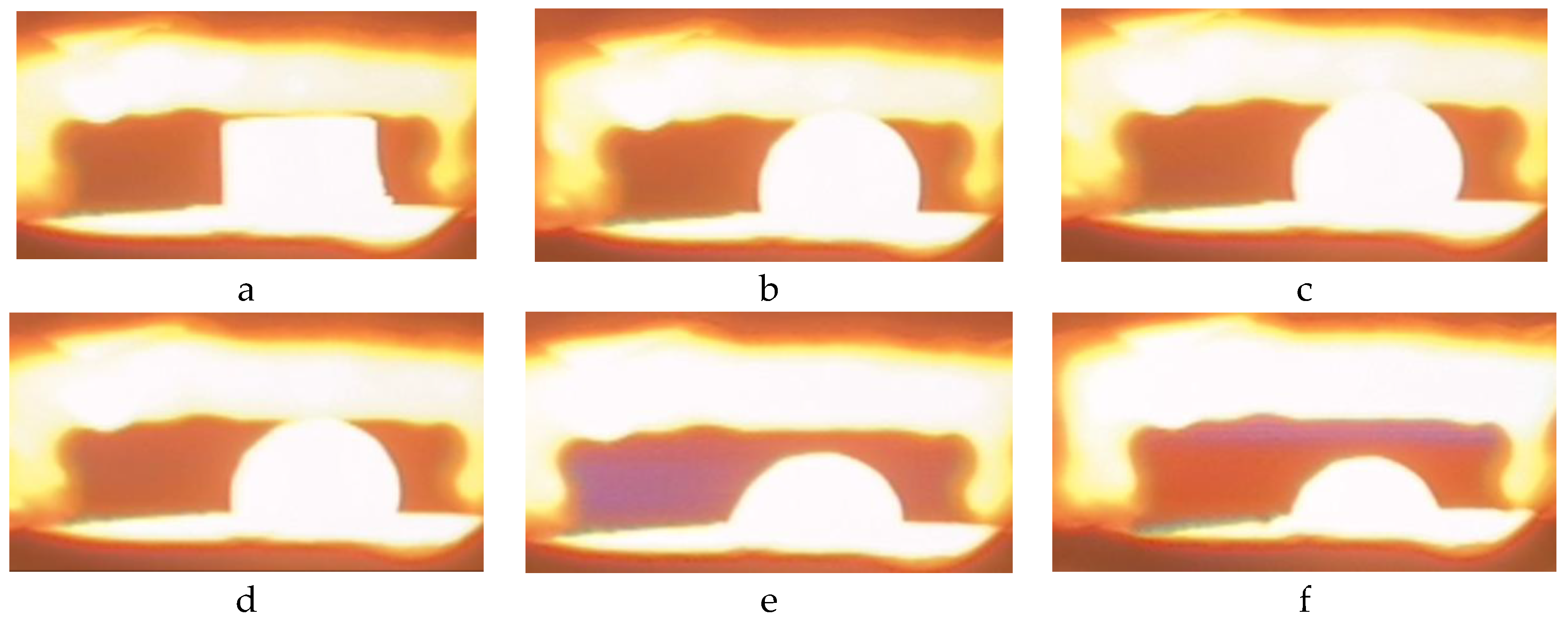

Figure 5 shows the key stages of changing the shape of the droplet when the titanium melt interacts with the surface of the calcium titanate substrate with an increase in temperature from the melting point to 1728 °C. The molten titanium forms a droplet of a regular hemispherical shape from the moment of melting to 1728 °C. Oscillation of the melt surface was observed with periodic bursts and the formation of secondary hemispheres and the ejection of microdroplets at higher temperatures up to 1728 °C. It indicates gas emission at temperatures above 1718 °C.

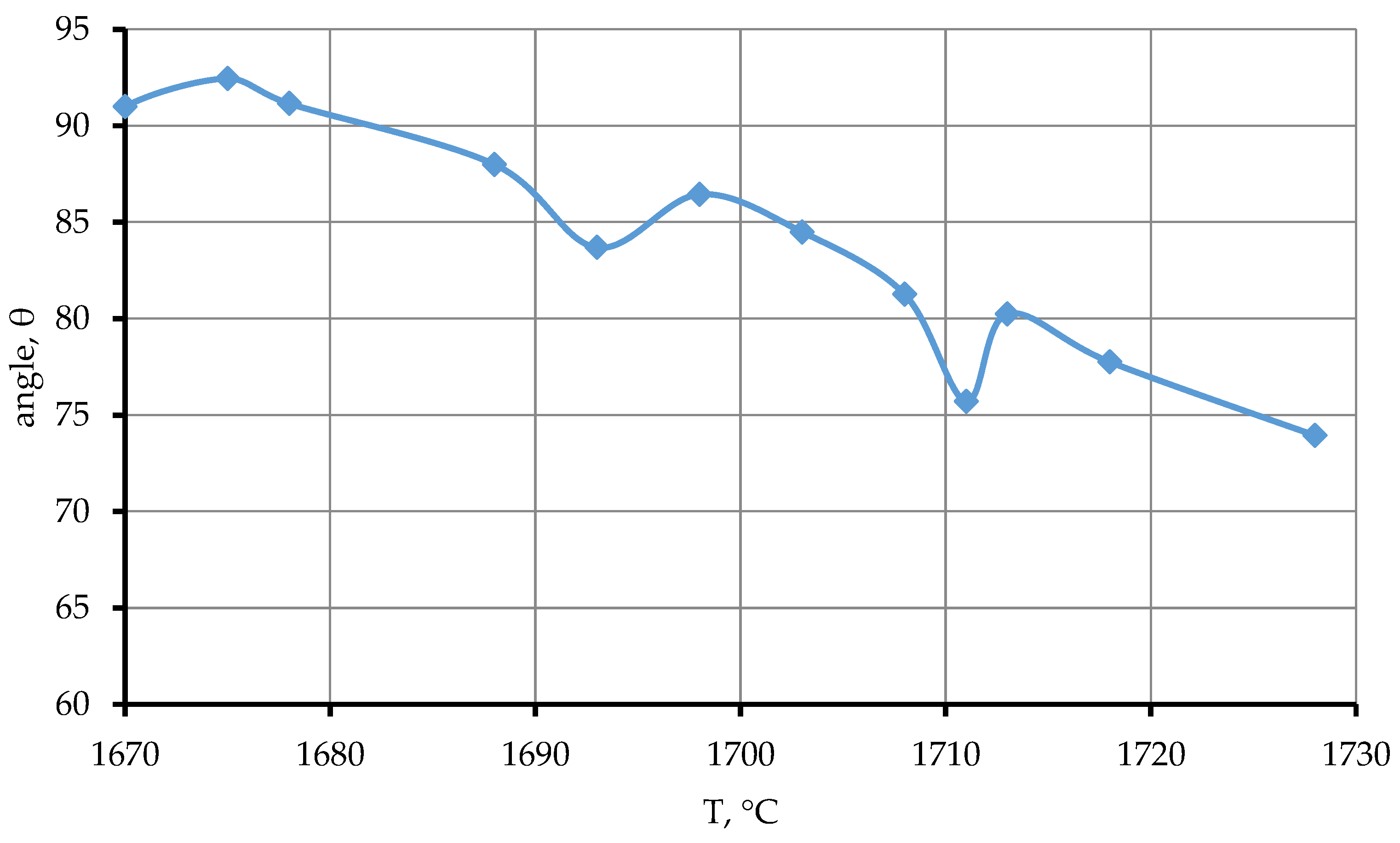

The wetting contact angle increases to 93° from the moment of melting, indicating the low wettability of the substrate surface by the titanium melt (

Figure 6). A further increase in temperature from >1688 °C to 1728 °C leads to a gradual decrease in the wetting contact angle from 93 °C to 74 °C.

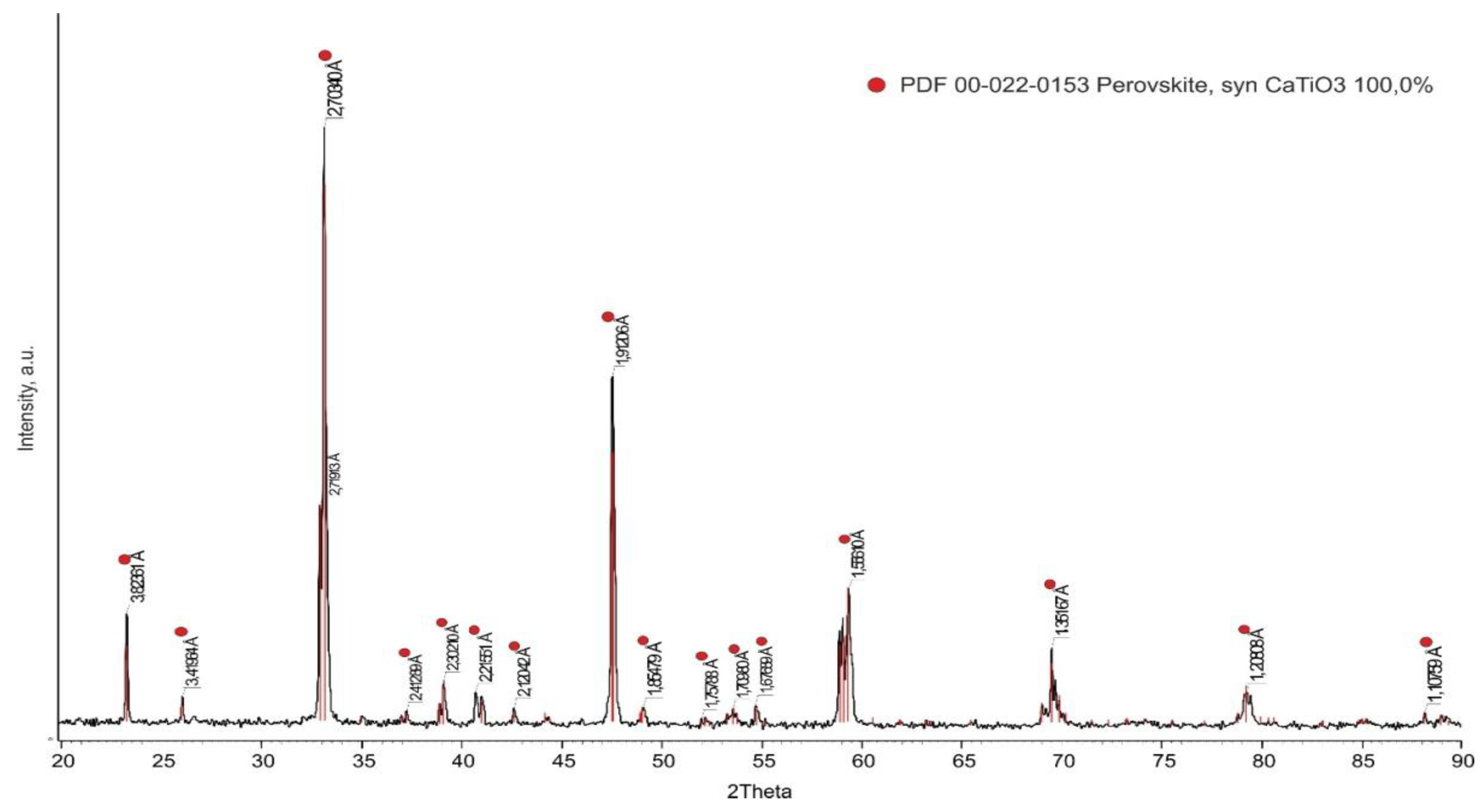

As it can be seen from the data presented (

Figure 7, line 1), the contact angle ranges from 83° to 86° for the first seconds and then stabilizes at 82° under isothermal holding conditions at 1705 °C. The wetting angle is gradually reduced from 82° to 72° at 100 second. Then, at 140 seconds, the angle increases from 72° to 90°. Further exposure results in a decrease in the edge angle from 90 to 84°. The established time dependence of the wetting contact angle of the CaTiO

3 substrate by the titanium melt at 1705 °C indicates a change in the reaction interaction at the substrate/melt contact interface over time.

Figure 7.

Dependence of the contact angle θ on time. 1—1705 °C, 2—1720 °C.

Figure 7.

Dependence of the contact angle θ on time. 1—1705 °C, 2—1720 °C.

Figure 8.

View of the sample of the post-experiment on the titanium melt wettability on the CaTiO3 substrate.

Figure 8.

View of the sample of the post-experiment on the titanium melt wettability on the CaTiO3 substrate.

The dependence of the wetting contact angle of a CaTiO

3 substrate with titanium melt at 1720 °C on the contact time is shown in

Figure 7, line 2. As it can be seen from the data presented, isothermal holding for the first seconds leads to an increase in the marginal angle to 84°, and then to a gradual decrease in the wetting angle from 84° to 50°. The reason for the abrupt change in the wetting angle is the release of the gas phase and the resulting oscillation of the droplet surface.

Thus, it was established in the course of the studies conducted that the wetting contact angle decreases with an increase in the contact temperature of the melt with the substrate. As the isothermal holding time increases at 1705 °C, the wetting contact angle increases, and at 1720 °C, the wetting contact angle gradually decreases. It indicates a change in the parameters of interfacial interaction and surface tension of the melt both with a change in the contact temperature and with an increase in the duration of contact.

3.2. Study of the Transition Zone Formed at the CaTiO3/Ti Melt Contact Interface

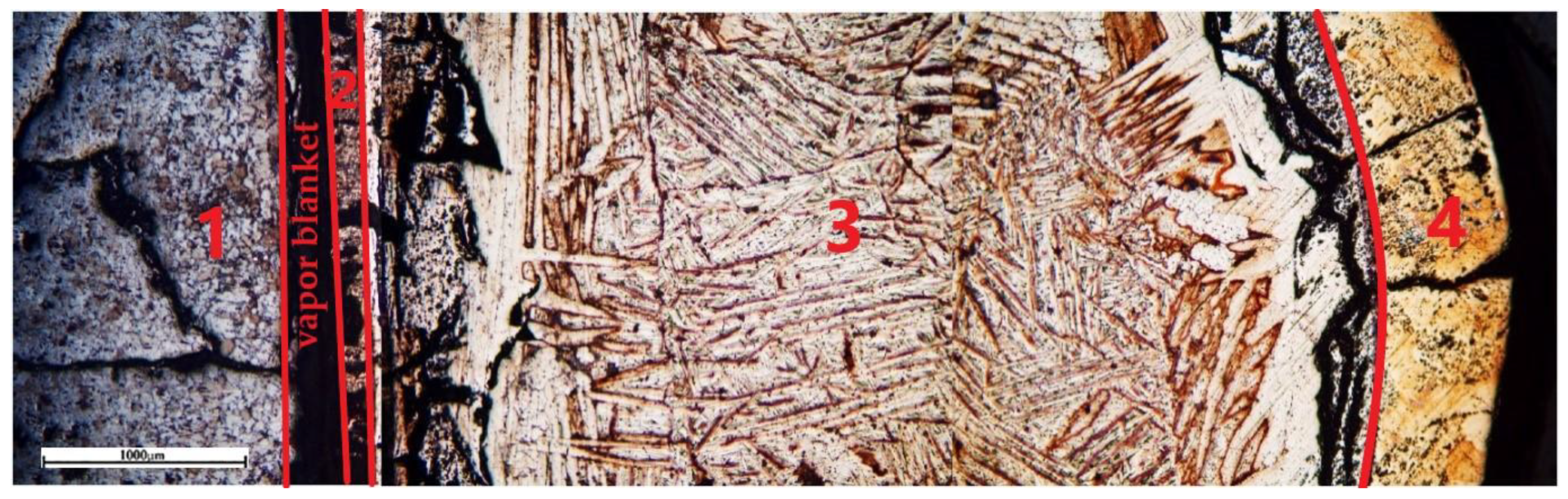

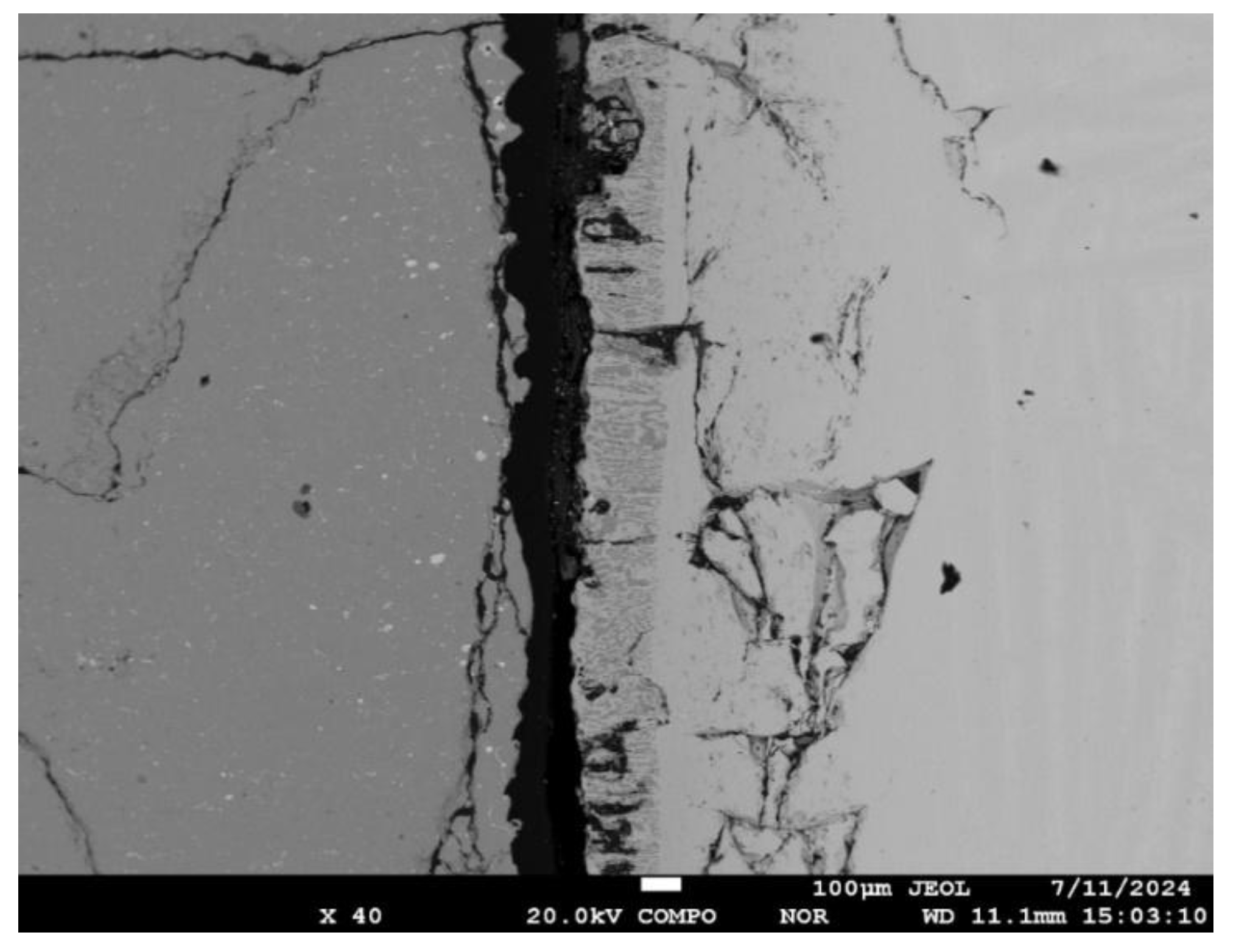

A section was prepared to study the transition zone in a sample formed after isothermal holding at 1720 °C for 430 s. Characteristic zones were found in the cross-section indicating the development of reactive interaction and diffusion of reaction products into the melt volume (

Figure 9): 1—ceramics impregnated with melted titanium, 2—CaTiO

3+ αTi(O) eutectic zone, 3—transition alphonated layer with a coarse-crystalline needle-like structure, 4—titanium with a polyhedral fine-grained structure.

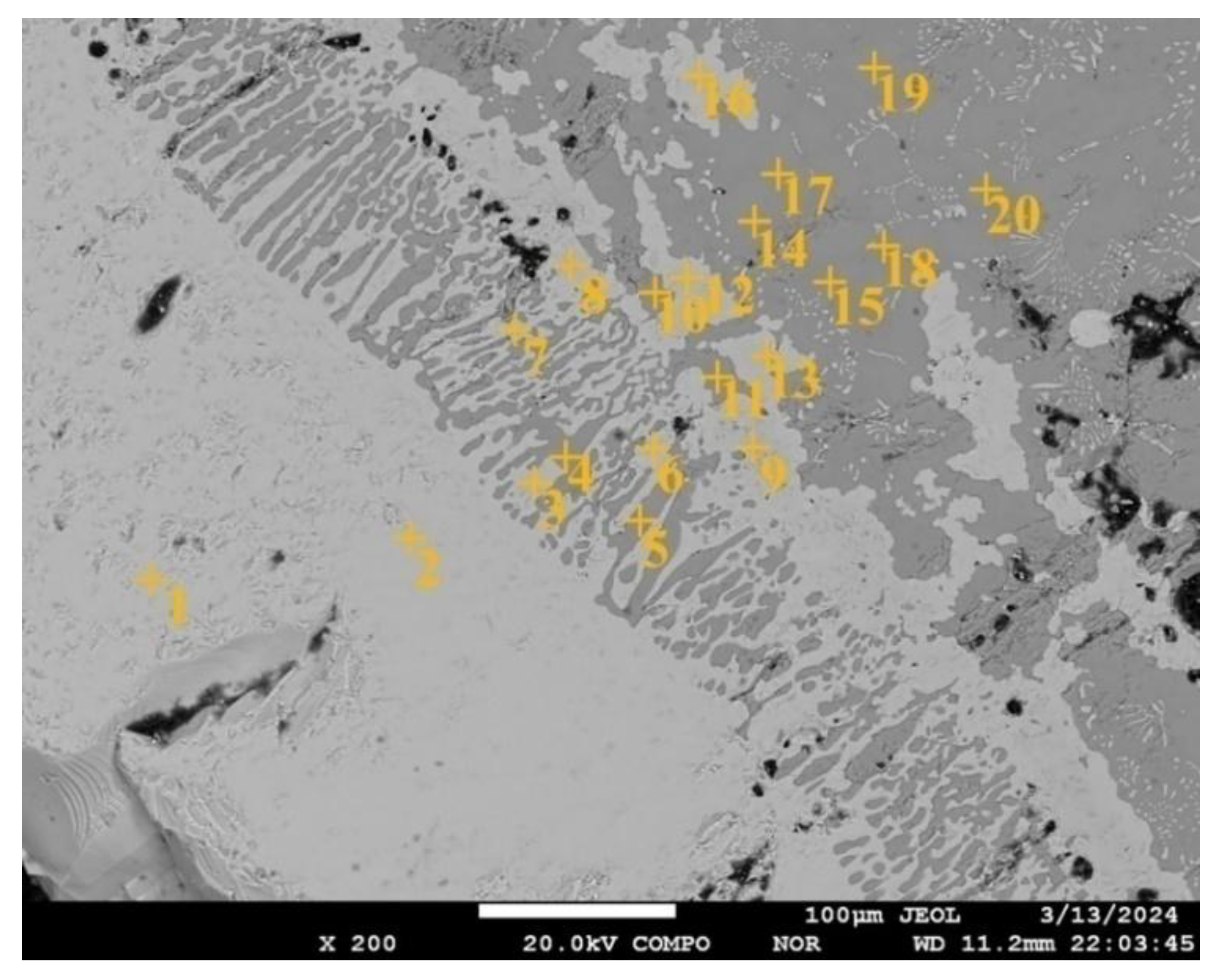

Titanium veins with a high oxygen content along the boundaries of CaTiO

3 grains are found in zone No. 1 (

Figure 10). The depth of its penetration from the ceramic substrate surface is 1.2-1.3 mm. It is obvious that this process develops due to capillary wetting at the initial stages of the interaction of the titanium melt with the substrate. Subsequently, the penetration of the melt is suspended.

A two-phase mixture was formed in the form of globular emissions of a solid solution of oxygen and calcium in titanium up to 25 μm in size (

Figure 11) in a CaTiO

3 matrix directly at the contact with the melt in the ceramic substrate structure at a depth of up to 200 μm. This structure suggests the formation of a liquid phase containing Ca, Ti, and oxygen at the CaTiO

3 grain boundaries. At the same time, the composition of the oxide phase at all sites corresponds to the composition of the original CaTiO

3 after crystallization (points 14, 15, 17, 18, 19 and 20 in

Figure 11 and in

Table 1).

A biphasic region formed near the substrate made by a mixture of columnar, globular, and teardrop crystals in a titanium matrix in zone No. 2 (

Figure 11). The width of this zone is 90-130 μm. Columnar crystals are oriented mainly perpendicular to the substrate surface. Microprobe analysis of the transition zone indicates that it is formed with a two-phase mixture of a solid solution of oxygen and calcium in titanium (points 3, 6, 7, 8, 9 in

Figure 11 and in

Table 1) and columnar oxide secretions. The composition of the oxide phase is close to CaTiO

3, but with a slightly higher oxygen content (points 4, 5 and 10 in

Figure 11 and in

Table 1). The rounded shape and the presence of globular inclusions of a titanium-based solid solution in their structure indicate that the oxide phase material was in a liquid state. This structure may indicate the eutectic decay of the melt during cooling.

A gap of inhomogeneous width of 100-200 μm was formed at the boundary between the transition layer (zone No. 2) and the ceramic substrate (zone No. 1) (

Figure 10). Pores of various shapes and sizes (10-20 μm) were formed near the contact boundary of titanium and ceramics. The variable width of the gap may be a consequence of the formation of a vapor blanket at the interface between the melt and the solid ceramic substrate.

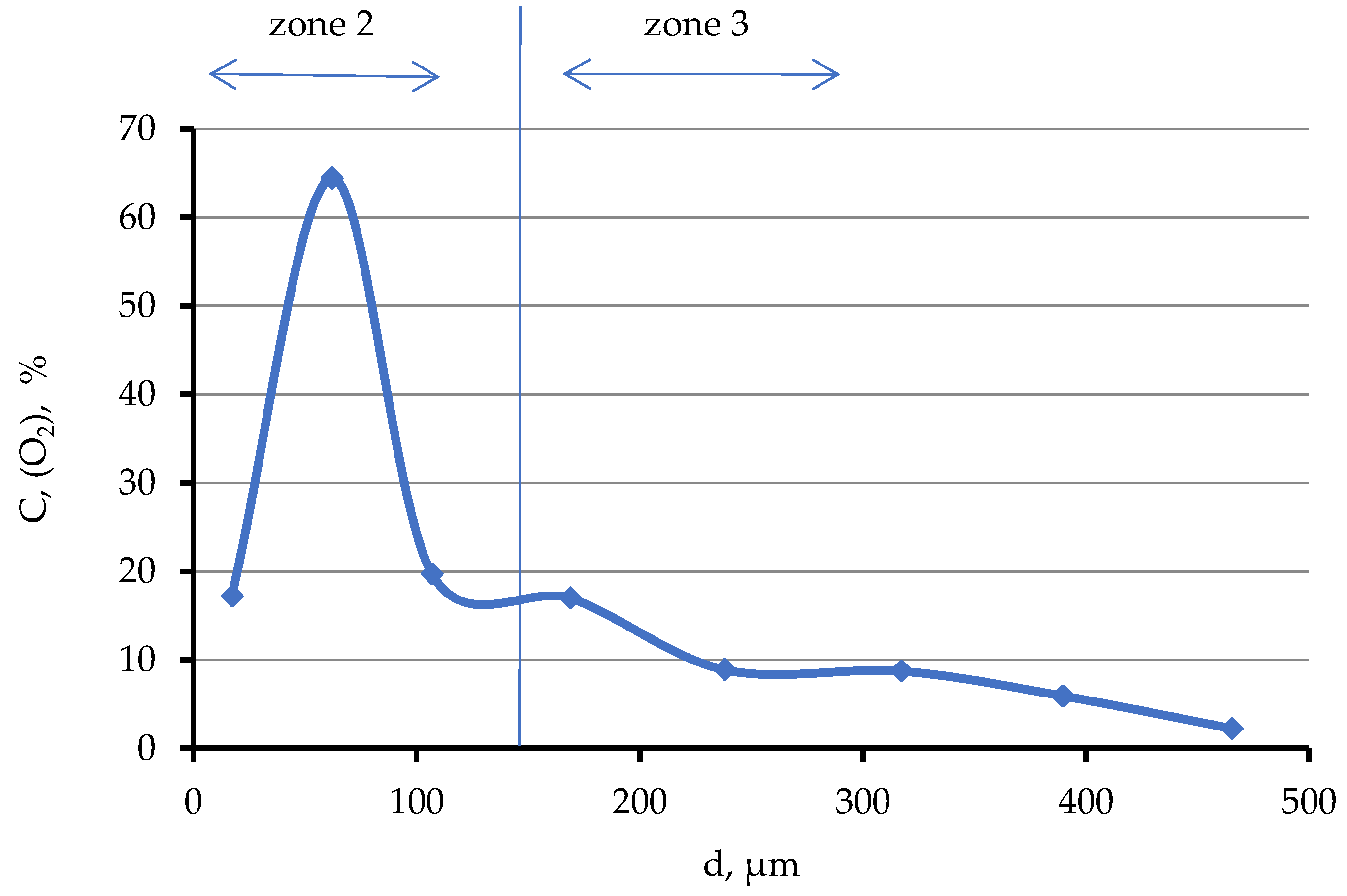

Titanium has a structure characteristic of α titanium in zone No. 3 (

Figure 9). This area has a coarse-grained coarse-needle structure. The width of this layer is up to 2.9 mm. Titanium contains a high concentration of oxygen immediately in the vicinity of zone No. 2 (points 1 and 2 in

Figure 11 and in

Table 1), while calcium is not found in these points. As you move away from the boundary with zone No. 2, the oxygen concentration decreases from ~16 to 2 mol.% already at a distance of ~400 μm (

Figure 12). Further, oxygen is not recorded by microprobe analysis. The oxygen concentration increases again with approach to zone No. 4 at a distance of <300 μm, (

Figure 13,

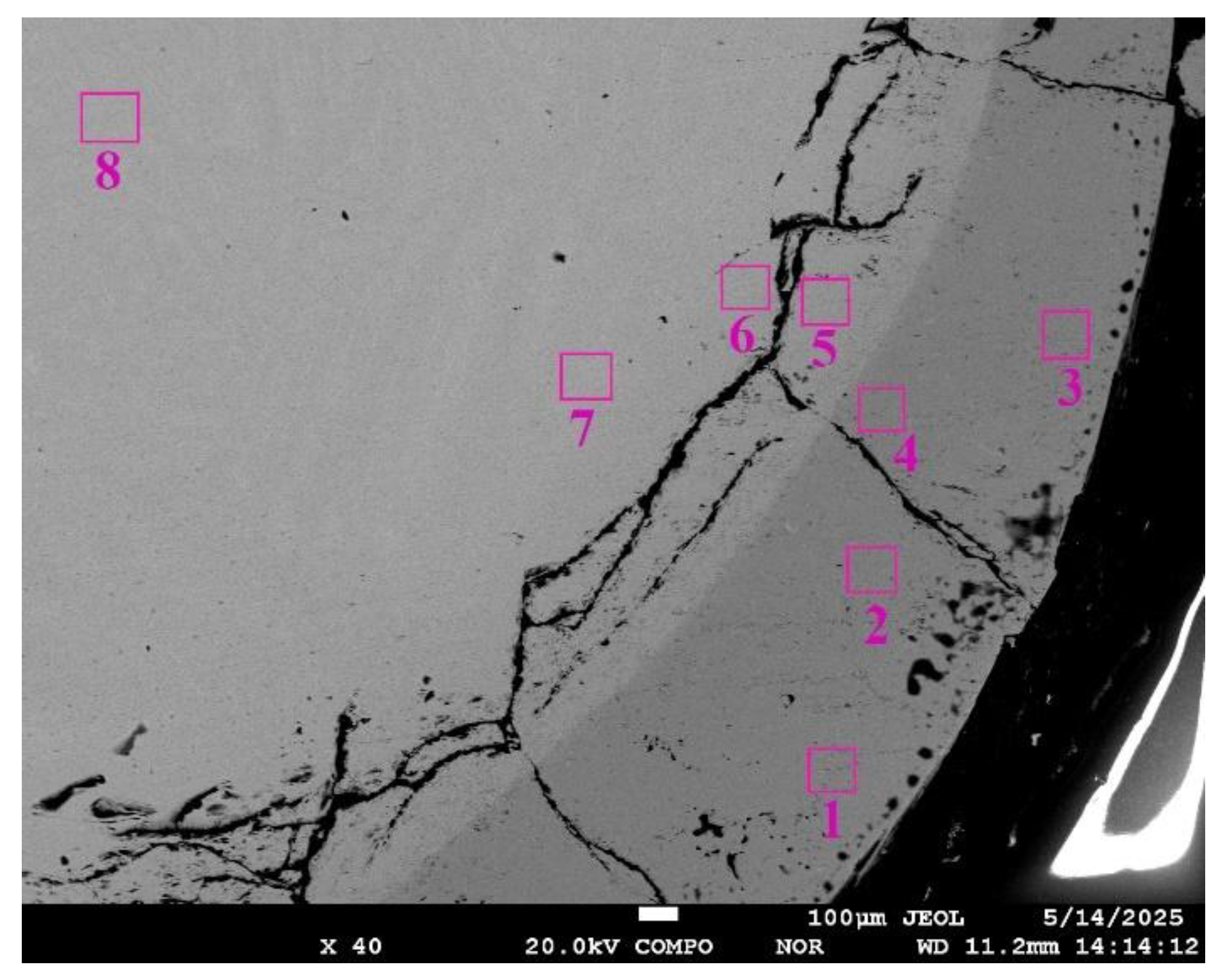

Table 2, point 5) and reaches 24.6 mol.% at the boundary with zone No. 4.

Zone No. 4 is a layer that forms the shell of the titanium melt dome bordering the furnace atmosphere at a residual pressure of 1.3*10

-3 mmHg. The microstructure of the metal in zone No. 4 is fine-grained. When it is etched it acquires a light brown color, before etching the surface had a metallic sheen. Analysis of the composition along the cross-section of this zone revealed a ratio of atoms close to the equiatomic ratio (

Figure 13,

Table 2). It indicates that the material forming this layer is a TiO compound. At the same time, the oxygen concentration in it decreases to 27.6 mol.% at the border with zone No. 3.

4. Discussion

As a rule, the substrate wetting by the melt increases in the case of a reactive interaction. The wetting contact angle is large in a titanium melt/CaTiO3 substrate system. It can indicate an insignificant diffusion interaction. However, studies of the melt-substrate contact zone have shown that the titanium melt reacts with calcium titanate. The following features of the reactive interaction of CaTiO3 with titanium melt are distinguished:

- −

the titanium melt penetrates into the substrate due to capillary wetting in the process of interaction;

- −

calcium, oxygen and titanium diffuse from the surface of the substrate into the melt, due to the dissolution of the substrate;

- −

a gap is formed at the boundary between the melt and the substrate;

- −

a zone where oriented CaTiO3 crystals alternate with a solid solution of oxygen and calcium in titanium is formed at the contact boundary in titanium;

- −

a liquid phase is formed in the ceramic substrate near the interface;

- −

despite a fairly long isothermal exposure, calcium and oxygen penetrated into titanium to a small depth (up to 90-130 μm and up to ~400 μm, respectively) from the contact boundary with the CaTiO3 substrate;

- −

a shell with a high oxygen content has formed on the surface of the titanium droplet. It is similar in composition to the TiO compound.

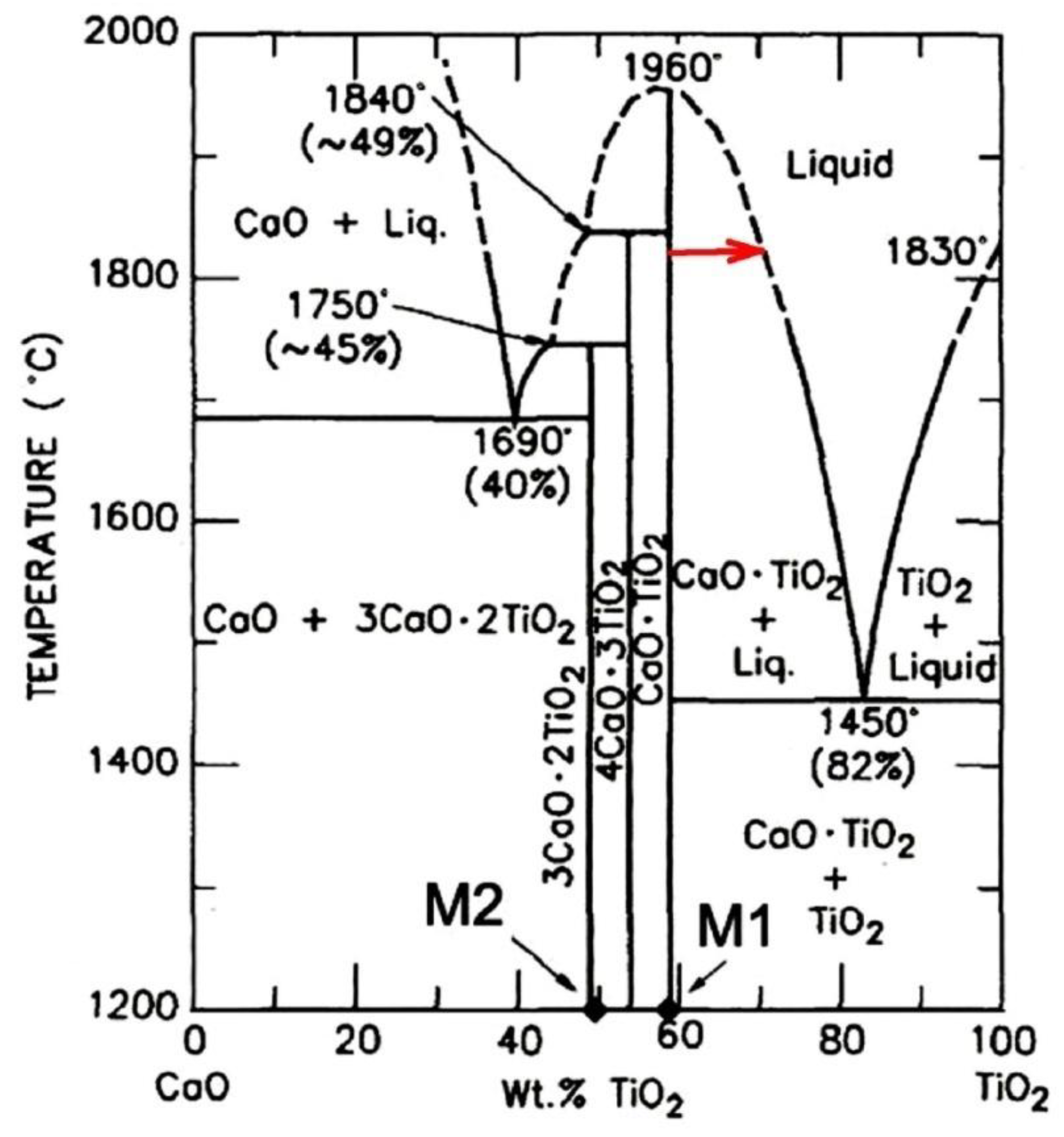

The observed changes in composition and structure in the diffusion pair titanium melt/CaTiO3 substrate indicate the development of complex physical and chemical processes at the interface of their contact. Since the interaction between the melt and the substrate is dictated by the system tendency to equilibrium, some of the observed phenomena can be described by considering the regions of the Ti-Ca-O state diagram.

According to the CaO-TiO

2 state diagram (

Figure 14), when the CaO concentration decreases, a liquid phase is formed. Then when it is cooled, it crystallizes by eutectic reaction with the release of a mixture of CaTiO

3+TiO

2 at 1450 °C. The formation of a mixture of CaTiO

3+αTiO, Ca crystals was found in the experiments conducted in the transition layer (zone No. 2). Since the CaTiO

3-αTiO, Ca state diagram has not been constructed, it can be concluded by analogy with the CaO-TiO

2 diagram that a liquid phase is formed due to a decrease in the proportion of CaO at the boundary of contact with the titanium melt, and it crystallizes as eutectics. This is confirmed by the results of studies of the substrate microstructure. The reason for the decrease in the CaO content at the interface of contact with the titanium melt can only be the reduction of calcium directly from the CaTiO

3 compound by titanium (reaction 2,

Figure 1) and its subsequent evaporation. According to the Ca-Ti state diagram [

29], calcium does not form solid solutions with titanium. It explains the fact that calcium in titanium is found only in the reaction zone, in the area where, in addition to it, the composition contains a high concentration of oxygen (up to 25 at.%).

It is known [

31] that the vapor pressure of calcium metal increases significantly with an increase in temperature and a decrease in atmospheric pressure. The boiling point of calcium at atmospheric pressure is 1484 °C. Obviously, that under the experimental conditions (1720 °C, 1.3*10

-3 mmHg. reduction of calcium to a metallic state led to the release of the vapor phase. It explains the observed gap between the titanium melt and the substrate that is an analogue of a “vapor blanket”. Oxygen and titanium generated during the reaction interaction were dissolved in the titanium melt. A significant heterogeneity in the distribution of oxygen across the cross-section of the titanium melt droplet can be explained by the formation of two stratification liquids. According to the Ti-O state diagram at atmospheric pressure in the range of oxygen concentration of 37-53 atm. % above ~1780 °C there is a monotectic transformation in the system. Probably, a decrease in pressure causes a change in equilibrium in the Ti-O system and, as a consequence, the state diagram is transformed with a decrease in the temperatures of the phase transformation lines. It may explain the formation of a TiO shell on the surface of a titanium droplet at 1720 °C and the preservation of the droplet in a liquid state during the experiment.

According to the Ti-O state diagram [

32], with an increase in the concentration of oxygen in titanium, its melting point increases. Therefore, βTi and αTi layers should be formed at a certain distance from the contact boundary with ceramics in the case of isothermal interaction of titanium with CaTiO

3 in the temperature range of 1670-1720 °C. And the αTi layer are formed above 1720 °C. However, this is not found. In particular, there is no significant dissolution of oxygen in titanium at a distance from the reaction zone. Obviously, the simultaneous dissolution of oxygen and calcium, as well as low pressure, does not cause the formation of an αTi layer, and oxygen diffuses to the surface of the droplet and directly binds to the TiO compound.

The large wetting contact angle of the CaTiO3 substrate by the titanium melt, despite the development of reactive interaction, is explained by the formation of a thin layer of calcium vapor. For this reason, the value of the wetting contact angle is mainly determined by the forces of surface tension.

Thus, the interaction mechanism of a titanium melt with a CaTiO3 substrate can be described from the standpoint of gradual dissolution of CaTiO3 in the melt with simultaneous reduction of metallic calcium according to reaction equation 2 and redistribution of oxygen and titanium in the melt volume. The formation of the vapor layer limits the reaction process and prevents the ceramics from being wetted by the melt.

These properties of CaTiO3 ceramics make it a promising material as the basis of molding sands for casting titanium alloys. The formation of a vapor layer at the contact boundary will prevent the formation of burn-on defects. At the same time, there will be an insignificant saturation of the titanium melt with oxygen under conditions of short-term contact, and it will not have a noticeable effect on the mechanical properties of the castings. CaTiO3 cannot be used as a refractory crucible material for smelting titanium alloys, since the long duration of contact with the melt and the circulation of the melt will lead to significant oxygen contamination.

5. Conclusion

- −

Calcium titanate CaTiO3 obtained by melting and subsequent sintering, is poorly wetted by titanium melt at low temperatures and short contact times. The wetting improves with an increase in temperature and contact time due to the development of a reaction between CaTiO3 and titanium;

- −

The reactive interaction includes the following processes: impregnation of the sintered material with titanium melt, dissolution of the surface of CaTiO3 and formation of solutions of calcium and oxygen in titanium in the reaction zone; reduction to a metallic state of Ca with its subsequent evaporation; formation of a layer of compound similar in composition to TiO on the outer surface of the melt;

- −

The observed phase formation and oxygen distribution in the reaction zone cannot be explained by the state diagrams of the CaO-TiO2 and Ti-O systems in full. It is assumed that the high-temperature part of the Ti-O state diagram is substantially transformed at low pressure;

- −

The data obtained allow us to recommend CaTiO3 as a filler for molding materials used in casting titanium alloys.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.K., A.P. and A.M.; methodology, A.P. A.U. and M.Ch.; software, A.P., A.U. and M.Ch.; validation, A.P., A.U. and M.Ch.; formal analysis A.P., A.U. and M.Ch.; investigation, A.P., A.U., M.Ch., B.Ksh. and Zh.A.; resources, A.U., M.Ch., B.Ksh. and Zh.A.; data curation, A.U., M.Ch. and B.Ksh.; writing—original draft preparation, A.P., A.U. and M.Ch.; writing—review and editing, A.P., A.U. and M.Ch.; visualization, A.P., A.U. and M.Ch.; supervision, B.K., A.P. and A.M.; project administration, A.P.; A.M.; funding acquisition, B.K.; A.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Science Committee of the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Republic of Kazakhstan, grant number BR21882140

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable. The authors declare that this manuscript does not involve or relate to animals, human subjects, human tissues, or plants.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Panichkin, A.V.; Uskenbayeva, A.M.; Imanbayeva, A.; Temirgaliyev, S.; Djumabekov, D. Interaction of titanium melts with various refractory compounds. Complex use of mineral resources 2016, 3, 84–90. [Google Scholar]

- Fashu, S.; Lototskyy, M.; Davids, M.; Pickering, L.; Linkov, V.; Tai, S.; Renheng, T.; Fangming, X.; Fursikov, P.; Tarasov, B. A review on crucibles for induction melting of titanium alloys. Mater. Des. 2020, 186, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, B.; Chen, G.; Xiong, F.; Liu, X.; Zhang, X.; et al. A Review on the Preparation Techniques of Titanium Alloy and the Selection of Refractories. J Miner Sci Materials 2020, 1, 1007. [Google Scholar]

- Frueh, C.; Poirier, D.R.; Maguire, M.C.; Harding, R.A. Attempts to develop a ceramic mould for titanium casting — a review. International Journal of Cast Metals Research 1996, 9, 233–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kartavykh, A.V.; Tcherdyntsev, V.V.; Zollinger, J. TiAl–Nb melt interaction with AlN refractory crucibles. Materials Chemistry and Physics 2009, 116, 300–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frenzel, J.; Zhang, Z.; Neuking, K.; Eggeler, G. High quality vacuum induction melting of small quantities of NiTi shape memory alloys in graphite crucibles. Journal of Alloys and Compounds 2004, 385, Issues 1–2, 214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenzhaliyev, B.K.; Panichkin, A.V.; Uskenbayeva, A.; Chukmanova, M.T.; Mamaeva, A.A.; Kshibekova, B.B.; Alibekov, Zh. Interaction of liquid titanium with zirconates and titanates of some alkaline earth metals. Materials Research Express 2024, 11, 106509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.H.; Gao, Y.H.; Lu, X.G.; Ding, W.Z.; Ren, Z.M.; Deng, K. Interaction between the ceramic CaZrO3 and the melt of titanium alloys. Advances in Science and Technology 2010, 70, 136–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klotz, U.E.; Legner, C.; Bulling, F.; Freitag, L.; Faßauer, C.; Schafföner, S.; Aneziris, C.G. Investment casting of titanium alloys with calcium zirconate moulds and crucibles. The International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology 2019, 103, 343–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Kang, J.; Gao, P.; Qin, Z.; Lu, X.; Li, C. Dissolution of BaZrO3 refractory in titanium melt. International Journal of Applied Ceramic Technology 2018, 15, 1459–1466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhu, K.L.; Liu, L.J.; Lu, X.G.; Wu, G.X.; Li, C.H. Preparation of BaZrO3 crucible and its interfacial reaction with molten titanium alloys. Journal of The Chinese Ceramic Society 2013, 41, 1272–1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamayeva, A.A.; Panichkin, A.V.; Chukmanova, M.T.; Imbarova, A.T.; Kenzhaliyev, B.K.; Belov, V.D. Investigation of the mechanism for interaction of calcium zirconate, oxides of calcium and zirconium with titanium melts. International Journal of Cast Metals Research 2022, 35, 152–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passerone, A.; Muolo, M.L.; Valenza, F. Critical Issues for Producing UHTC-Brazed Joints: Wetting and Reactivity. Journal of Materials Engineering and Performance 2016, 25, 3330–3347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Kamiya, A.; Yamada, T.; Shi, W.; Naganuma, K.; Mukai, K. Surface tension, wettability and reactivity of molten titanium in Ti/yttria-stabilized zirconia system. Materials Science and Engineering: A 2002, 327, Issue 2, 117–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eustathopoulos, N. Dynamics of wetting in reactive metal/ ceramic systems. Acta Materialia 1998, 46, 2319–2327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhang, H.; Gao, M.; Li, Q.; Bian, W.; Tao, T.; Zhang, H. High-Temperature Wettability and Interactions between Y-Containing Ni-Based Alloys and Various Oxide Ceramics. Materials 2018, 11, 749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, J.; Puga, H.; Ribeiro, C.S.; Teodoro, O.M.N.D.; Monteiro, A.C. Characterisation of metal/mould interface on investment casting of γ-TiAl. International Journal of Cast Metals Research 2006, 19, 331–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, K.F.; Lin, C.C. Interfacial reactions between Ti-6Al-4V alloy and zirconia mold during casting. Journal of materials science 1999, 34, 5899–5906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panichkin, A.V.; Imanbayeva, A.B.; Imbarova, A.T. Titanium melt interaction with the refractory oxides of some metals. Complex use of mineral resources 2019, 2, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warren, J.A.; Boettinger, W.J.; Roosen, A.R. Modeling reactive wetting. Acta Materialia 1998, 46, Issue 9, 3247–3264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meier, A.; Javernick, D.A.; Edwards, G.R. Ceramic-metal interfaces and the spreading of reactive liquids. JOM. 1999, 51, 44–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, S.; Li, M.; Wang, H.; Zhu, J.; Shao, G.; Xu, H.; Lu, H.; Zhang, R. Preparation of a (Ca,Sr,Ba)ZrO3 Crucible by Slip Casting for the Vacuum Induction Melting of NiTi Alloy. Materials 2024, 17, 1924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naidich, Y.V.; Zhuravlev, V.S.; Chuprina, V.G. Sov. Powder Metall. Met. Ceram. 1974, 13, 236. [Google Scholar]

- Tomsia, A.P.; Saiz, E.; Dalgleish, B.J.; Canon, R.M. Proceedings of the Fourth Japan International SAMPE Symposium. 1998, 347.

- Zhu, J.; Kamiya, A.; Yamada, T.; Shi, W.; Naganuma, K.; Mukai, K. Surface tension, wettability and reactivity of molten titanium in Ti/yttria-stabilized zirconia system. Materials Science and Engineering: A 2002, 327, 117–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schafföner, S.; Fruhstorfer, J.; Faßauer, C.; Freitag, L.; Jahn, C.; Aneziris, C.G. Advanced refractories for titanium metallurgy based on calcium zirconate with improved thermomechanical properties. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2019, 39, 4394–4403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schafföner, S.; Fruhstorfer, J.; Faßauer, C.; Freitag, L.; Jahn, C.; Aneziris, C.G. Influence of in situ phase formation on properties of calcium zirconate refractories. Journal of the European Ceramic Society 2017, 37, 305–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freitag, L.; Schafföner, S.; Lippert, N.; Faßauer, C.; Aneziris, C.G.; Legner, C.; Klotz, U.E. Silica-free investment casting molds based on calcium zirconate. Ceram. Int. 2017, 43, 6807–6814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obinata, I.; Takeuchi, Y.; Saikawa, S. The System Titanium-Calcium. Trans. Am. Soc. Met. 1960, 52, 1072–1083. [Google Scholar]

- DeVries, R.C.; Roy, R.; Osborn, E.F. Phase equilibria in the system CaO–TiO2. J Phys Chem. 1954, 58, 1069–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacob, K.T.; Srikanth, S.; Waseda, Y. Activities, concentration fluctuations and complexing in liquid Ca–Al alloys. Trans. Japan Inst. Metals 1988, 29, 50–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okamoto, H. O-Ti (oxygen-titanium). Journal of Phase Equilibria and Diffusion 2011, 32, 473–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).