Submitted:

06 June 2025

Posted:

09 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

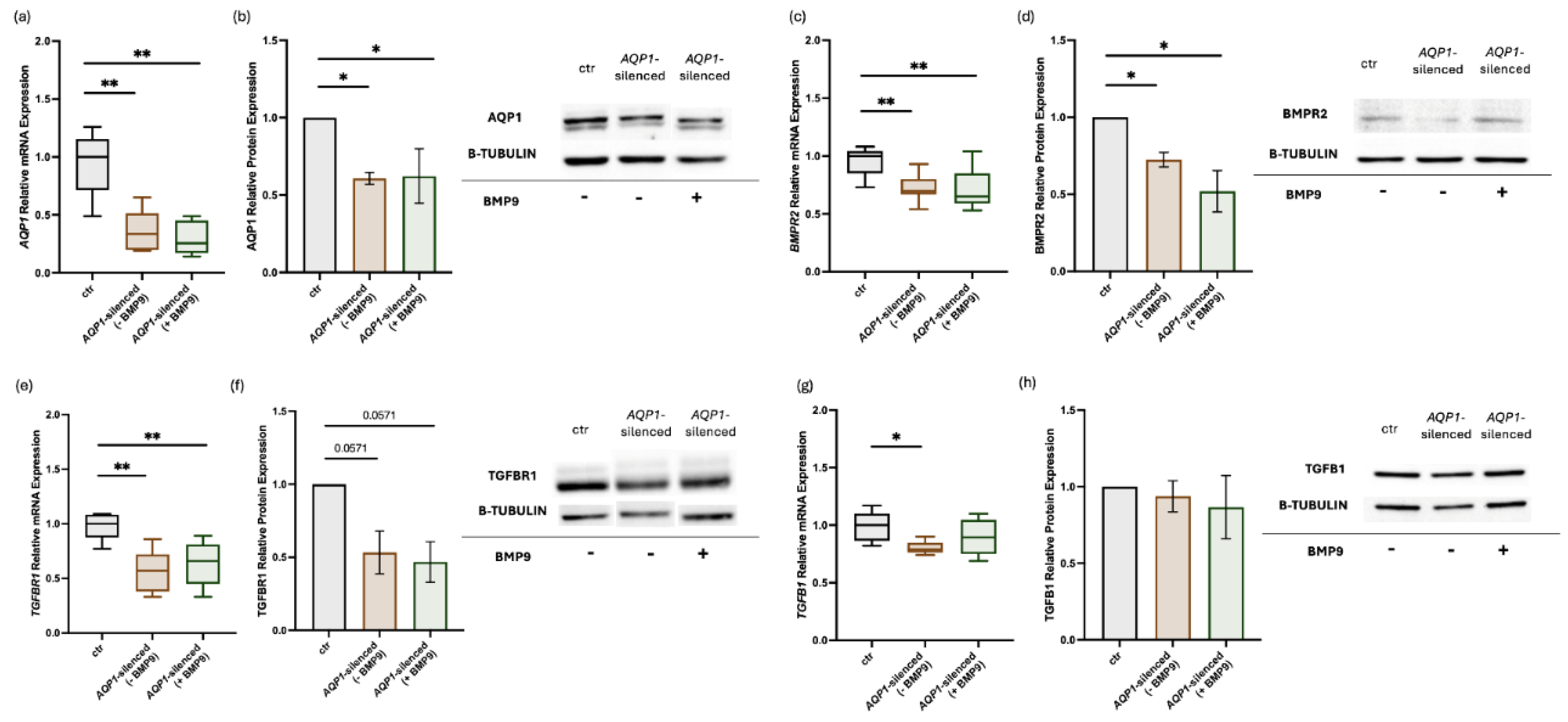

2.1. Effects of AQP1-Silencing and Exogenous Administration of BMP9 on AQP1 and BMP/TGF-β Signaling Molecules in Human Pulmonary Microvascular Endothelial Cells

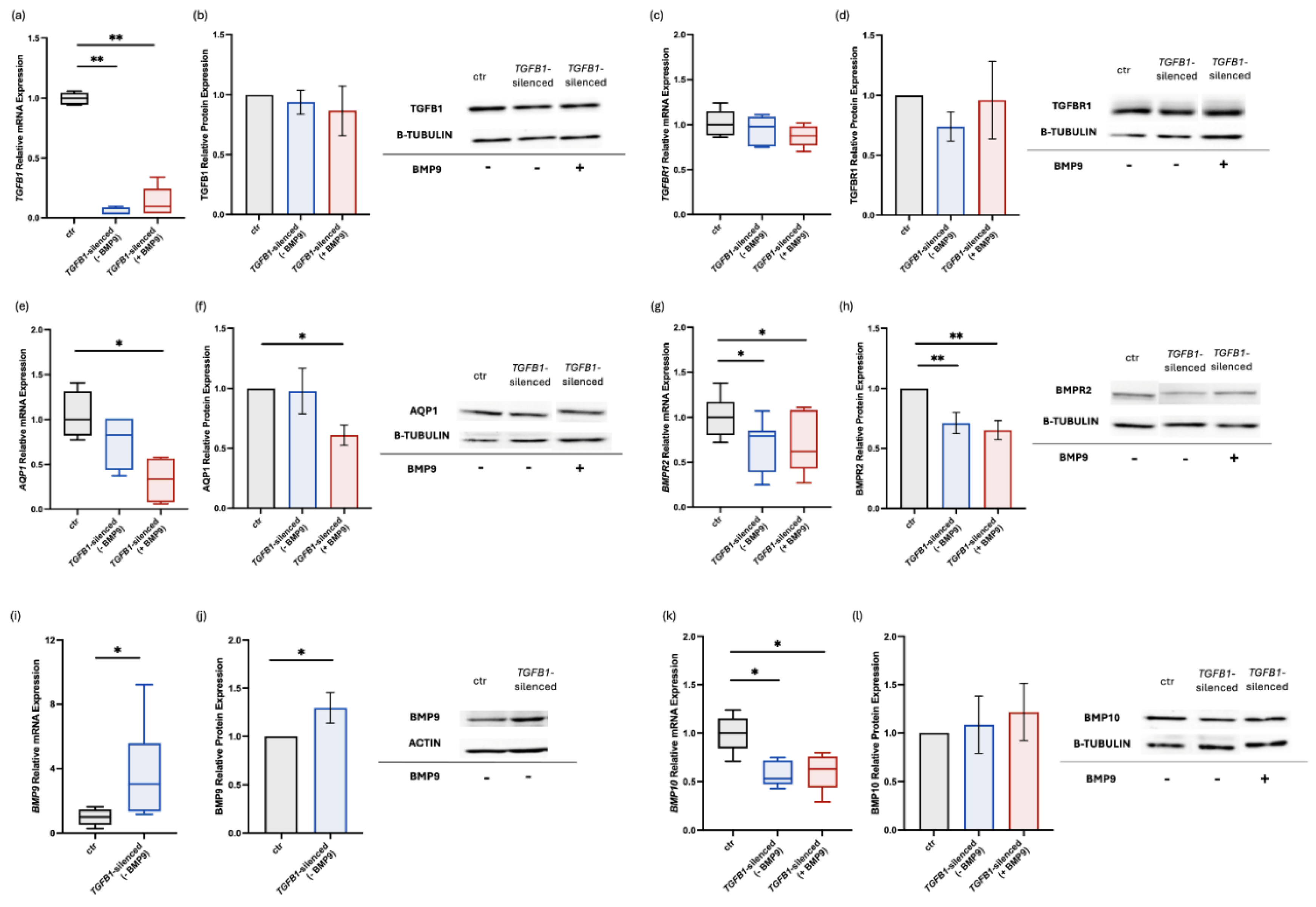

2.2. Effects of TGFB1-Silencing and Exogenous Administration of BMP9 on BMP/TGF-β Signaling Molecules and AQP1 in Human Pulmonary Microvascular Endothelial Cells

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Cell Culture, Transfection, and Treatment with BMP9

4.2. RNA and Protein Extraction

4.3. Reverse Transcription and Quantitative Real-Time PCR

4.4. SDS-Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis (PAGE) and Immunoblotting

4.5. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Li, W.; Quigley, K. Bone morphogenetic protein signalling in pulmonary arterial hypertension: revisiting the BMPRII connection. Biochemical Society transactions 2024, 52, 1515–1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huertas, A.; Guignabert, C.; Barberà, J.A.; Bärtsch, P.; Bhattacharya, J.; Bhattacharya, S.; Bonsignore, M.R.; Dewachter, L.; Dinh-Xuan, A.T.; Dorfmüller, P.; et al. Pulmonary vascular endothelium: the orchestra conductor in respiratory diseases: Highlights from basic research to therapy. The European respiratory journal 2018, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evans, C.E.; Cober, N.D.; Dai, Z.; Stewart, D.J.; Zhao, Y.Y. Endothelial cells in the pathogenesis of pulmonary arterial hypertension. The European respiratory journal 2021, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, L.; Ormiston, M.L.; Yang, X.; Southwood, M.; Gräf, S.; Machado, R.D.; Mueller, M.; Kinzel, B.; Yung, L.M.; Wilkinson, J.M.; et al. Selective enhancement of endothelial BMPR-II with BMP9 reverses pulmonary arterial hypertension. Nature medicine 2015, 21, 777–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrell, N.W.; Aldred, M.A.; Chung, W.K.; Elliott, C.G.; Nichols, W.C.; Soubrier, F.; Trembath, R.C.; Loyd, J.E. Genetics and genomics of pulmonary arterial hypertension. The European respiratory journal 2019, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marinho, Y.; Villarreal, E.S.; Loya, O.; Oliveira, S.D. Mechanisms of lung endothelial cell injury and survival in pulmonary arterial hypertension. American journal of physiology. Lung cellular and molecular physiology 2024, 327, L972–l983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorelova, A.; Berman, M.; Al Ghouleh, I. Endothelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition in Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension. Antioxidants & redox signaling 2021, 34, 891–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humbert, M.; Guignabert, C.; Bonnet, S.; Dorfmüller, P.; Klinger, J.R.; Nicolls, M.R.; Olschewski, A.J.; Pullamsetti, S.S.; Schermuly, R.T.; Stenmark, K.R.; et al. Pathology and pathobiology of pulmonary hypertension: state of the art and research perspectives. The European respiratory journal 2019, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurakula, K.; Smolders, V.F.E.D.; Tura-Ceide, O.; Jukema, J.W.; Quax, P.H.A.; Goumans, M.-J. Endothelial Dysfunction in Pulmonary Hypertension: Cause or Consequence? Biomedicines 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cober, N.D.; VandenBroek, M.M.; Ormiston, M.L.; Stewart, D.J. Evolving Concepts in Endothelial Pathobiology of Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension. Hypertension 2022, 79, 1580–1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, J.D.; Girerd, B.; Montani, D.; Wang, X.J.; Galiè, N.; Austin, E.D.; Elliott, G.; Asano, K.; Grünig, E.; Yan, Y.; et al. BMPR2 mutations and survival in pulmonary arterial hypertension: an individual participant data meta-analysis. The Lancet. Respiratory medicine 2016, 4, 129–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gräf, S.; Haimel, M.; Bleda, M.; Hadinnapola, C.; Southgate, L.; Li, W.; Hodgson, J.; Liu, B.; Salmon, R.M.; Southwood, M.; et al. Identification of rare sequence variation underlying heritable pulmonary arterial hypertension. Nature communications 2018, 9, 1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andre, P.; Joshi, S.R.; Briscoe, S.D.; Alexander, M.J.; Li, G.; Kumar, R. Therapeutic Approaches for Treating Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension by Correcting Imbalanced TGF-β Superfamily Signaling. Frontiers in medicine 2021, 8, 814222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bousseau, S.; Sobrano Fais, R.; Gu, S.; Frump, A.; Lahm, T. Pathophysiology and new advances in pulmonary hypertension. BMJ medicine 2023, 2, e000137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austin, E.D.; Aldred, M.A.; Alotaibi, M.; Gräf, S.; Nichols, W.C.; Trembath, R.C.; Chung, W.K. Genetics and precision genomics approaches to pulmonary hypertension. The European respiratory journal 2024, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lotsios, N.S.; Keskinidou, C.; Dimopoulou, I.; Kotanidou, A.; Orfanos, S.E.; Vassiliou, A.G. Aquaporin Expression and Regulation in Clinical and Experimental Sepsis. International journal of molecular sciences 2023, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meli, R.; Pirozzi, C.; Pelagalli, A. New Perspectives on the Potential Role of Aquaporins (AQPs) in the Physiology of Inflammation. Frontiers in physiology 2018, 9, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vassiliou, A.G.; Keskinidou, C.; Kotanidou, A.; Frantzeskaki, F.; Dimopoulou, I.; Langleben, D.; Orfanos, S.E. Knockdown of bone morphogenetic protein type II receptor leads to decreased aquaporin 1 expression and function in human pulmonary microvascular endothelial cells. Canadian Journal of Physiology and Pharmacology 2020, 98, 834–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vassiliou, A.G.; Keskinidou, C.; Kotanidou, A.; Frantzeskaki, F.; Dimopoulou, I.; Langleben, D.; Orfanos, S.E. Decreased bone morphogenetic protein type II receptor and BMP-related signalling molecules’ expression in aquaporin 1-silenced human pulmonary microvascular endothelial cells. Hellenic journal of cardiology : HJC = Hellenike kardiologike epitheorese 2021, 62, 84–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adu-Amankwaah, J.; You, Q.; Liu, X.; Jiang, J.; Yang, D.; Liu, K.; Yuan, J.; Wang, Y.; Hu, Q.; Tan, R. Pulmonary Hypertension: Molecular Mechanisms and Clinical Studies. MedComm 2025, 6, e70134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lotsios, N.S.; Keskinidou, C.; Dimopoulou, I.; Kotanidou, A.; Langleben, D.; Orfanos, S.E.; Vassiliou, A.G. Effects of Modulating BMP9, BMPR2, and AQP1 on BMP Signaling in Human Pulmonary Microvascular Endothelial Cells. International journal of molecular sciences 2024, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preston, I.R.; Lewis, D.; Gomberg-Maitland, M. Using Sotatercept in the Care of Patients With Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension. Chest 2024, 166, 604–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalucka, J.; de Rooij, L.; Goveia, J.; Rohlenova, K.; Dumas, S.J.; Meta, E.; Conchinha, N.V.; Taverna, F.; Teuwen, L.A.; Veys, K.; et al. Single-Cell Transcriptome Atlas of Murine Endothelial Cells. Cell 2020, 180, 764–779.e720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masri, F.A.; Xu, W.; Comhair, S.A.; Asosingh, K.; Koo, M.; Vasanji, A.; Drazba, J.; Anand-Apte, B.; Erzurum, S.C. Hyperproliferative apoptosis-resistant endothelial cells in idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension. American journal of physiology. Lung cellular and molecular physiology 2007, 293, L548–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guignabert, C.; Alvira, C.M.; Alastalo, T.P.; Sawada, H.; Hansmann, G.; Zhao, M.; Wang, L.; El-Bizri, N.; Rabinovitch, M. Tie2-mediated loss of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma in mice causes PDGF receptor-beta-dependent pulmonary arterial muscularization. American journal of physiology. Lung cellular and molecular physiology 2009, 297, L1082–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Q.; Yaoita, N.; Tabuchi, A.; Liu, S.; Chen, S.H.; Li, Q.; Hegemann, N.; Li, C.; Rodor, J.; Timm, S.; et al. Endothelial Heterogeneity in the Response to Autophagy Drives Small Vessel Muscularization in Pulmonary Hypertension. Circulation 2024, 150, 466–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saadoun, S.; Papadopoulos, M.C.; Hara-Chikuma, M.; Verkman, A.S. Impairment of angiogenesis and cell migration by targeted aquaporin-1 gene disruption. Nature 2005, 434, 786–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leggett, K.; Maylor, J.; Undem, C.; Lai, N.; Lu, W.; Schweitzer, K.; King, L.S.; Myers, A.C.; Sylvester, J.T.; Sidhaye, V.; et al. Hypoxia-induced migration in pulmonary arterial smooth muscle cells requires calcium-dependent upregulation of aquaporin 1. American journal of physiology. Lung cellular and molecular physiology 2012, 303, L343–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuoler, C.; Haider, T.J.; Leuenberger, C.; Vogel, J.; Ostergaard, L.; Kwapiszewska, G.; Kohler, M.; Gassmann, M.; Huber, L.C.; Brock, M. Aquaporin 1 controls the functional phenotype of pulmonary smooth muscle cells in hypoxia-induced pulmonary hypertension. Basic research in cardiology 2017, 112, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Liu, Q.; Pei, Y.; Gong, M.; Cui, X.; Pan, J.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Yuan, X.; et al. Aqp-1 Gene Knockout Attenuates Hypoxic Pulmonary Hypertension of Mice. Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology 2019, 39, 48–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, X.; Philip, N.M.; Jiang, H.; Smith, Z.; Huetsch, J.C.; Damarla, M.; Suresh, K.; Shimoda, L.A. Upregulation of Aquaporin 1 Mediates Increased Migration and Proliferation in Pulmonary Vascular Cells From the Rat SU5416/Hypoxia Model of Pulmonary Hypertension. Frontiers in physiology 2021, Volume 12, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogo, T.; Chowdhury, H.M.; Yang, J.; Long, L.; Li, X.; Torres Cleuren, Y.N.; Morrell, N.W.; Schermuly, R.T.; Trembath, R.C.; Nasim, M.T. Inhibition of overactive transforming growth factor-β signaling by prostacyclin analogs in pulmonary arterial hypertension. American journal of respiratory cell and molecular biology 2013, 48, 733–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, A.; Zuo, C.; He, Y.; Chen, G.; Piao, L.; Zhang, J.; Xiao, B.; Shen, Y.; Tang, J.; Kong, D.; et al. EP3 receptor deficiency attenuates pulmonary hypertension through suppression of Rho/TGF-β1 signaling. The Journal of clinical investigation 2015, 125, 1228–1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yung, L.M.; Nikolic, I.; Paskin-Flerlage, S.D.; Pearsall, R.S.; Kumar, R.; Yu, P.B. A Selective Transforming Growth Factor-β Ligand Trap Attenuates Pulmonary Hypertension. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine 2016, 194, 1140–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bellaye, P.S.; Yanagihara, T.; Granton, E.; Sato, S.; Shimbori, C.; Upagupta, C.; Imani, J.; Hambly, N.; Ask, K.; Gauldie, J.; et al. Macitentan reduces progression of TGF-β1-induced pulmonary fibrosis and pulmonary hypertension. The European respiratory journal 2018, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zabini, D.; Granton, E.; Hu, Y.; Miranda, M.Z.; Weichelt, U.; Breuils Bonnet, S.; Bonnet, S.; Morrell, N.W.; Connelly, K.A.; Provencher, S.; et al. Loss of SMAD3 Promotes Vascular Remodeling in Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension via MRTF Disinhibition. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine 2018, 197, 244–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rol, N.; Kurakula, K.B.; Happé, C.; Bogaard, H.J.; Goumans, M.J. TGF-β and BMPR2 Signaling in PAH: Two Black Sheep in One Family. International journal of molecular sciences 2018, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upton, P.D.; Davies, R.J.; Tajsic, T.; Morrell, N.W. Transforming growth factor-β(1) represses bone morphogenetic protein-mediated Smad signaling in pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells via Smad3. American journal of respiratory cell and molecular biology 2013, 49, 1135–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aykul, S.; Martinez-Hackert, E. Transforming Growth Factor-β Family Ligands Can Function as Antagonists by Competing for Type II Receptor Binding. The Journal of biological chemistry 2016, 291, 10792–10804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García de Vinuesa, A.; Abdelilah-Seyfried, S.; Knaus, P.; Zwijsen, A.; Bailly, S. BMP signaling in vascular biology and dysfunction. Cytokine & growth factor reviews 2016, 27, 65–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, L.; Desroches-Castan, A.; Mallet, C.; Guyon, L.; Cumont, A.; Phan, C.; Robert, F.; Thuillet, R.; Bordenave, J.; Sekine, A.; et al. Selective BMP-9 Inhibition Partially Protects Against Experimental Pulmonary Hypertension. Circulation Research 2019, 124, 846–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Upton, P.D.; Davies, R.J.; Trembath, R.C.; Morrell, N.W. Bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) and activin type II receptors balance BMP9 signals mediated by activin receptor-like kinase-1 in human pulmonary artery endothelial cells. The Journal of biological chemistry 2009, 284, 15794–15804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolic, I.; Yung, L.M.; Yang, P.; Malhotra, R.; Paskin-Flerlage, S.D.; Dinter, T.; Bocobo, G.A.; Tumelty, K.E.; Faugno, A.J.; Troncone, L.; et al. Bone Morphogenetic Protein 9 Is a Mechanistic Biomarker of Portopulmonary Hypertension. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine 2019, 199, 891–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Rice, M.; Swist, S.; Kubin, T.; Wu, F.; Wang, S.; Kraut, S.; Weissmann, N.; Böttger, T.; Wheeler, M.; et al. BMP9 and BMP10 Act Directly on Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells for Generation and Maintenance of the Contractile State. Circulation 2021, 143, 1394–1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouvard, C.; Tu, L.; Rossi, M.; Desroches-Castan, A.; Berrebeh, N.; Helfer, E.; Roelants, C.; Liu, H.; Ouarné, M.; Chaumontel, N.; et al. Different cardiovascular and pulmonary phenotypes for single- and double-knock-out mice deficient in BMP9 and BMP10. Cardiovascular Research 2022, 118, 1805–1820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Theilmann, A.L.; Hawke, L.G.; Hilton, L.R.; Whitford, M.K.M.; Cole, D.V.; Mackeil, J.L.; Dunham-Snary, K.J.; Mewburn, J.; James, P.D.; Maurice, D.H.; et al. Endothelial BMPR2 Loss Drives a Proliferative Response to BMP (Bone Morphogenetic Protein) 9 via Prolonged Canonical Signaling. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2020, 40, 2605–2618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szulcek, R.; Sanchez-Duffhues, G.; Rol, N.; Pan, X.; Tsonaka, R.; Dickhoff, C.; Yung, L.M.; Manz, X.D.; Kurakula, K.; Kiełbasa, S.M.; et al. Exacerbated inflammatory signaling underlies aberrant response to BMP9 in pulmonary arterial hypertension lung endothelial cells. Angiogenesis 2020, 23, 699–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krafft, E.; Lybaert, P.; Roels, E.; Laurila, H.P.; Rajamäki, M.M.; Farnir, F.; Myllärniemi, M.; Day, M.J.; Mc Entee, K.; Clercx, C. Transforming growth factor beta 1 activation, storage, and signaling pathways in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis in dogs. Journal of veterinary internal medicine 2014, 28, 1666–1675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krump-Konvalinkova, V.; Bittinger, F.; Unger, R.E.; Peters, K.; Lehr, H.A.; Kirkpatrick, C.J. Generation of human pulmonary microvascular endothelial cell lines. Laboratory investigation; a journal of technical methods and pathology 2001, 81, 1717–1727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lleu, P.L.; Rebel, G. Interference of Good’s buffers and other biological buffers with protein determination. Analytical biochemistry 1991, 192, 215–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livak, K.J.; Schmittgen, T.D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods (San Diego, Calif.) 2001, 25, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laemmli, U.K. Cleavage of Structural Proteins during the Assembly of the Head of Bacteriophage T4. Nature 1970, 227, 680–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Gene | Sequence (5’-3’) | nt | |

|---|---|---|---|

| AQP1 | F | 5’-TATGCGTGCTGGCTACTACCGA-3’ | 22 |

| R | 5’-GGTTAATCCCACAGCCAGTGTAG-3’ | 23 | |

| BMP9 | F | 5’-CCTGCCCTTCTTTGTTGTCTTCTC-3’ | 24 |

| R | 5’-TGACTGCTCTCACCTGCCTCTGTG-3’ | 24 | |

| BMP10 | F | 5’-AAGCCTATGAATGCCGTGGTG-3’ | 21 |

| R | 5’-AGGCCTGGATAATTGCATGCTT-3’ | 22 | |

| BMPR2 | F | 5’-CCACCTCCTGACACAACACC-3’ | 20 |

| R | 5’-TGTGAAGACCTTGTTTACGGT-3’ | 21 | |

| GAPDH | F | 5’-ATGGGGAAGGTGAAGGTCG-3’ | 19 |

| R | 5’-GGGGTCATTGATGGCAACAATA-3’ | 22 | |

| TGFB1 | F | 5’-GCGTGCTAATGGTGGAAAC-3’ | 19 |

| R | 5’-CGGTGACATCAAAAGATAACCAC-3’ | 23 | |

| TGFBR1 | F | 5’-GACAACGTCAGGTTCTGGCTCA-3’ | 22 |

| R | 5’-CCGCCACTTTCCTCTCCAAACT-3’ | 22 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).