1. Introduction

1.1. Background of the Study

In the age of global connectivity, rapid technological advancements, and digitized information flow, the role of journalism and mass communication education is more crucial than ever. Informed citizens, ethical journalism, and critical communication skills are cornerstones of a democratic society. Journalism education is not just about disseminating facts or teaching technical skills—it is about equipping students with analytical, ethical, and contextual capabilities to question power, interpret society, and engage the public. In Bangladesh, however, the evolution of journalism education appears to be caught in a quagmire of outdated curricula, politically influenced pedagogy, and an entrenched culture of mediocrity. These factors have collectively led to a downward spiral in both academic standards and the employability of graduates in the field of mass communication and journalism (MCJ).

Since its inception in the early years of post-independence Bangladesh, journalism education has experienced phases of optimism and crisis. The Department of Mass Communication and Journalism at the University of Dhaka, established in 1962 as the first of its kind in the country, was envisioned to produce thought leaders, media professionals, and communication strategists who could shape public opinion and national narratives. However, over the past few decades, the expansion of MCJ departments across public and private universities has been accompanied by a noticeable decline in academic quality. This degeneration is not a mere consequence of resource limitations or infrastructural inadequacy; it is deeply rooted in the weaknesses of curriculum design and examination patterns, as well as the surface-level knowledge held by many educators in the field.

1.2. Problem Statement

The core of the current crisis lies in two interlinked issues: a rigid, poorly structured curriculum that fails to respond to the evolving media ecosystem, and an overreliance on repeated examination questions that perpetuate rote learning. These issues have been compounded by the prevalence of surface-level pedagogical engagement among faculty members. Many teachers, particularly in public universities, adhere to lecture methods grounded in outdated theories, decades-old notes, and limited reading, without adequate exposure to contemporary media practices or global academic debates. The reliance on repeated exam questions from past years fosters a culture of predictability and complacency among students, who often bypass the need for critical understanding by focusing on memorizing answers that are likely to reappear in assessments. As a result, MCJ graduates frequently lack the intellectual and practical competencies required for the digital-first journalism industry.

Anecdotal evidence and empirical observations suggest that this educational degradation is not isolated, but rather symptomatic of deeper structural, institutional, and pedagogical failures. These include inadequate teacher training, limited research output, lack of interdisciplinary collaboration, and absence of accountability mechanisms in curriculum revision and assessment systems. When students are evaluated through outdated or recycled questions, their ability to engage critically with course materials diminishes. In turn, the institutions producing these graduates lose credibility in the eyes of the media industry and international academic community.

1.3. Contextualizing the Crisis: Journalism in the Digital and Global Age

The media landscape in Bangladesh, like elsewhere, is experiencing a fundamental transformation. Digital platforms, citizen journalism, data visualization, mobile reporting, artificial intelligence in newsrooms, and algorithmic content distribution have reshaped how information is produced, consumed, and contested. Journalism is no longer confined to newspapers and broadcast studios; it now requires fluency in multimedia storytelling, data interpretation, ethical hacking, and interactive audience engagement. In this context, journalism education in Bangladesh must not only catch up but also innovate to remain relevant.

However, the current curriculum in most Bangladeshi MCJ departments remains rooted in analog-era theories with minimal integration of digital media practices or socio-technological change. Moreover, the exam-centric academic model prioritizes recall over reasoning, theory over application, and conformity over creativity. The mismatch between educational content and professional demands has reached a critical point, threatening to erode the legitimacy of journalism education itself.

1.4. Teachers as Epistemic Agents: A Missing Link

One of the most understudied yet pivotal factors in this discourse is the role of teachers as epistemic agents—that is, their role in shaping what is considered legitimate knowledge in the classroom. In Bangladesh, many educators in journalism departments lack active research engagement, field-level media experience, or international academic exposure. Their teaching often reflects surface-level knowledge: simplistic interpretations of communication theories, outdated examples, minimal familiarity with current trends in journalism ethics, technology, or media law. While these educators may possess formal academic qualifications, the depth and breadth of their intellectual engagement often remain limited.

Paulo Freire (1970) famously critiqued the ‘banking model’ of education, where teachers deposit knowledge into passive students without encouraging critical thought. This model appears especially apt in the case of many MCJ departments in Bangladesh, where lectures become one-way monologues, and assessments are reduced to regurgitation of textbook definitions. Without the intellectual leadership of critically aware educators, students are deprived of the tools necessary for navigating the complexities of contemporary media.

1.5. Implications for Higher Education and Democratic Society

The erosion of journalism education has broader implications beyond academic performance. It affects the quality of journalism, the vibrancy of democratic dialogue, and the ability of society to hold power accountable. A media ecosystem populated by undertrained journalists can lead to misinformation, sensationalism, ethical lapses, and even complicity in authoritarian agendas. Journalism education must, therefore, be viewed not as a technical or vocational endeavor but as a strategic investment in democratic resilience, public accountability, and social justice.

Bangladesh, despite being a rising economy with expanding access to digital technologies, continues to face challenges in press freedom, media pluralism, and journalistic professionalism. Without reforms in journalism education, including curriculum redesign and faculty development, the country risks producing generations of journalists who are ill-equipped to serve the public interest. This crisis, while structural, can be addressed through deliberate policy interventions, collaborative academic reforms, and a cultural shift in pedagogical practices.

1.6. Justification of the Study

While several studies have examined higher education challenges in Bangladesh, there is a relative dearth of empirical, critical, and interdisciplinary research on the specific crisis facing MCJ departments. This study seeks to fill that gap by focusing on three key dimensions: the weaknesses in curriculum content and structure, the prevalence and consequences of repeated examination questions, and the surface-level engagement of teachers with subject knowledge. By triangulating qualitative data from interviews, focus groups, and textual analysis of course materials, this research offers a comprehensive critique of the factors undermining journalism education in the country.

Furthermore, this study is timely in light of recent policy shifts, such as the implementation of outcome-based education (OBE) frameworks and calls for university accreditation reforms in Bangladesh. It provides evidence-based recommendations for stakeholders including university administrators, curriculum planners, education ministries, and media employers.

1.7. Research Gap

Most academic inquiries into journalism education in Bangladesh have focused on institutional history, student perceptions, or curriculum review in isolation. However, there has been little work linking curriculum weakness with pedagogical limitations and assessment practices. Moreover, the role of teacher epistemology—the depth, originality, and criticality of knowledge held and transmitted by faculty—has been largely ignored. This study addresses that gap by positioning teacher engagement as a central variable in the decline of journalism education.

1.8. Research Questions

To investigate the research problem systematically, this study poses the following guiding questions:

How do weaknesses in the existing MCJ curriculum affect the quality of journalism education in Bangladesh?

What are the patterns and impacts of repeated examination questions on student learning and critical engagement?

To what extent do faculty members in journalism departments possess and impart surface-level knowledge, and how does this affect pedagogical outcomes?

What reforms are necessary in curriculum design, teacher training, and assessment methods to enhance journalism education in Bangladesh?

1.9. Objectives of the Study

The main objectives of this study are:

To critically analyze the curriculum content of MCJ programs in Bangladeshi universities.

To investigate the prevalence and implications of repeated examination questions on learning outcomes.

To assess the depth of subject knowledge and pedagogical engagement of journalism educators.

To provide actionable recommendations for reforming journalism education in Bangladesh in line with global standards and local realities.

1.10. Structure of the Study

This research article is structured into several sections. Following this introduction, the literature review provides a critical overview of existing academic work on journalism education, curriculum theory, and pedagogy. The methodology section outlines the qualitative and textual analysis methods used in the study. This is followed by the findings and analysis section, which synthesizes data from course syllabi, interviews with teachers and students, and institutional documents. The discussion section links the findings to broader theoretical and policy debates. Finally, the conclusion and recommendations offer practical suggestions for curriculum reform, assessment redesign, and faculty development.

2.1. Research Design

This study adopts a qualitative research design rooted in a critical-interpretivist paradigm, which seeks to understand the underlying social, educational, and epistemological processes that contribute to the observed decline in the quality of Mass Communication and Journalism (MCJ) education in Bangladesh. The qualitative design allows for the exploration of subjective experiences, institutional practices, and sociocultural contexts that cannot be adequately captured through purely quantitative metrics. The research particularly focuses on understanding how curriculum deficiencies, repetitive exam patterns, and limited teacher engagement affect educational outcomes.

The critical dimension of this research enables the study to not only interpret but also critique existing pedagogical practices and recommend transformative changes. As Freire (1970) posits in Pedagogy of the Oppressed, education must be a liberating process rather than one of indoctrination. Accordingly, this study is positioned not merely as a descriptive inquiry but as an interventionist critique aimed at restoring academic excellence and relevance to MCJ education.

2.2. Research Questions

As outlined earlier, this study is driven by the following core research questions:

How do weaknesses in the existing MCJ curriculum affect the quality of journalism education in Bangladesh?

What are the patterns and impacts of repeated examination questions on student learning and critical engagement?

To what extent do faculty members in journalism departments possess and impart surface-level knowledge, and how does this affect pedagogical outcomes?

What reforms are necessary in curriculum design, teacher training, and assessment methods to enhance journalism education in Bangladesh?

2.3. Data Collection Methods

To capture a comprehensive understanding of the phenomena under investigation, this study utilizes multiple data collection methods, including:

2.3.1. Document Analysis

Document analysis is used to examine:

MCJ department curricula from major public universities (University of Dhaka, Rajshahi University, Chittagong University, etc.).

Course outlines, syllabi, reading lists, and assessment rubrics.

University academic calendars and teacher recruitment advertisements.

Examination questions from the past five to ten years.

The analysis focuses on identifying outdated content, thematic gaps, lack of skill-based modules, and the frequency of question repetition in exams. This method offers objective insights into institutional norms and academic rigidity.

2.3.2. In-Depth Interviews

Semi-structured, in-depth interviews were conducted with 20 respondents from the following categories:

10 currents and former MCJ students (selected purposively across public universities).

5 university teachers from MCJ departments (junior and senior faculty).

3 academic administrators or curriculum committee members.

2 media professionals/employers familiar with the hiring and evaluation of MCJ graduates.

Interviews explored perceptions of curriculum effectiveness, teaching methods, teacher competence, and students’ preparedness for the industry. A thematic guide ensured coverage of core areas while allowing flexibility for emergent themes.

2.3.3. Focus Group Discussions (FGDs)

Two FGDs were held:

The aim was to understand collective experiences regarding assessment patterns, learning motivation, teacher engagement, and employability concerns. FGDs helped uncover the emotional and cognitive impacts of rote-based education.

2.3.4. Classroom Observation

With permission from institutions, non-participant observations were conducted in four MCJ classroom sessions across two universities. Key aspects observed included:

Teaching methodology (e.g., lecture-based vs. participatory).

Use of teaching aids and updated content.

Student engagement levels.

Teacher’s command over the subject matter.

Observation notes were later coded for triangulation with other data sources.

2.4. Sampling Technique

Given the qualitative and exploratory nature of the study, purposive sampling was employed. This allowed the selection of information-rich participants who could provide nuanced insights into the research problem. Snowball sampling was also used to identify media professionals and former students working in the journalism field.

The selection criteria included:

Students who had completed at least two years in an MCJ program.

Teachers with a minimum of three years of teaching experience.

Institutions with established MCJ departments and available archival data.

This sampling approach ensured diversity in perspectives while maintaining the relevance of data sources to the research focus.

2.5. Data Analysis Procedures

Data from interviews, focus groups, and documents were subjected to thematic content analysis following Braun and Clarke’s (2006) six-step framework:

Familiarization with the data through repeated reading and transcription.

Initial coding to identify meaningful patterns (e.g., ‘repetitive questions,’ ‘outdated theory,’ ‘teacher apathy’).

Searching for themes by grouping codes into broader categories (e.g., ‘curriculum stagnation,’ ‘assessment culture,’ ‘epistemic surface’).

Reviewing themes to ensure internal consistency and external differentiation.

Defining and naming themes to reflect key findings.

Producing the report through data triangulation and interpretive synthesis.

NVivo software was used to organize and code qualitative data, facilitating systematic analysis and retrieval of themes.

2.6. Trustworthiness and Validity

To ensure credibility, the study used triangulation across data sources (documents, interviews, FGDs, and observations). Member checking was conducted by sharing summaries of interview responses with select participants to verify accuracy. Peer debriefing with academic colleagues helped refine interpretations and ensure objectivity.

Transferability was enhanced through thick description, enabling other researchers or policymakers to apply insights to similar contexts.

Dependability was ensured by maintaining an audit trail of coding decisions, data interpretation notes, and methodological adjustments during the research process.

Confirmability was supported through reflective memos documenting the researcher’s positionality, biases, and interaction with the data.

2.7. Ethical Considerations

The research adhered to ethical guidelines to protect participant rights and institutional integrity:

Informed consent was obtained from all interview and FGD participants.

Identities were anonymized using pseudonyms.

Institutional permissions were secured for classroom observations and document access.

Data were stored securely, with access limited to the researcher.

The research protocol was reviewed and approved by an academic ethics committee.

2.8. Limitations of the Study

While the study is comprehensive, certain limitations must be acknowledged:

The sample size, though rich in detail, may not represent all MCJ departments in the country.

Some faculty members were hesitant to discuss pedagogical weaknesses, possibly affecting the candor of responses.

The absence of quantitative data limits the generalizability of findings to national trends.

Despite these constraints, the study offers critical insights grounded in empirical evidence and theoretical reflection.

5. Nasty and Dirty Indoor Teachers’ Politics and the Practice of Pocketing Students: A Structural Critique

One of the most alarming and yet underexplored dimensions of the decline in Mass Communication and Journalism (MCJ) education in Bangladesh, especially within the Department of Mass Communication and Journalism, Rajshahi University (DoMCJRU), is the prevalence of indoor faculty politics and the practice of ‘pocketing’ students—a phenomenon marked by favoritism, exploitation, and unethical manipulation of student-faculty dynamics. These embedded power relations not only compromise academic integrity but also obstruct the healthy intellectual climate necessary for meaningful education.

5.1. Indoor Politics: Power Play in the Academic Arena

Faculty politics in many public universities, including DoMCJRU, have evolved into a highly polarized and ideologically fragmented arena, where political allegiance supersedes academic merit. Teachers often align themselves with national political parties and engage in factional conflict over departmental control, promotions, curriculum decisions, and administrative dominance. These rivalries translate into:

Nepotism in committee selection and academic assignments.

Sabotaging curriculum reform efforts initiated by opposing factions.

Delaying faculty training or blocking international collaborations to prevent credit from going to rivals.

Marginalizing junior or non-political faculty who attempt to innovate or reform teaching practices.

Such political toxicity results in institutional paralysis, where decisions are no longer driven by pedagogical or research excellence, but rather by turf wars and egoistic contests, damaging the overall academic culture and isolating students from progressive learning environments.

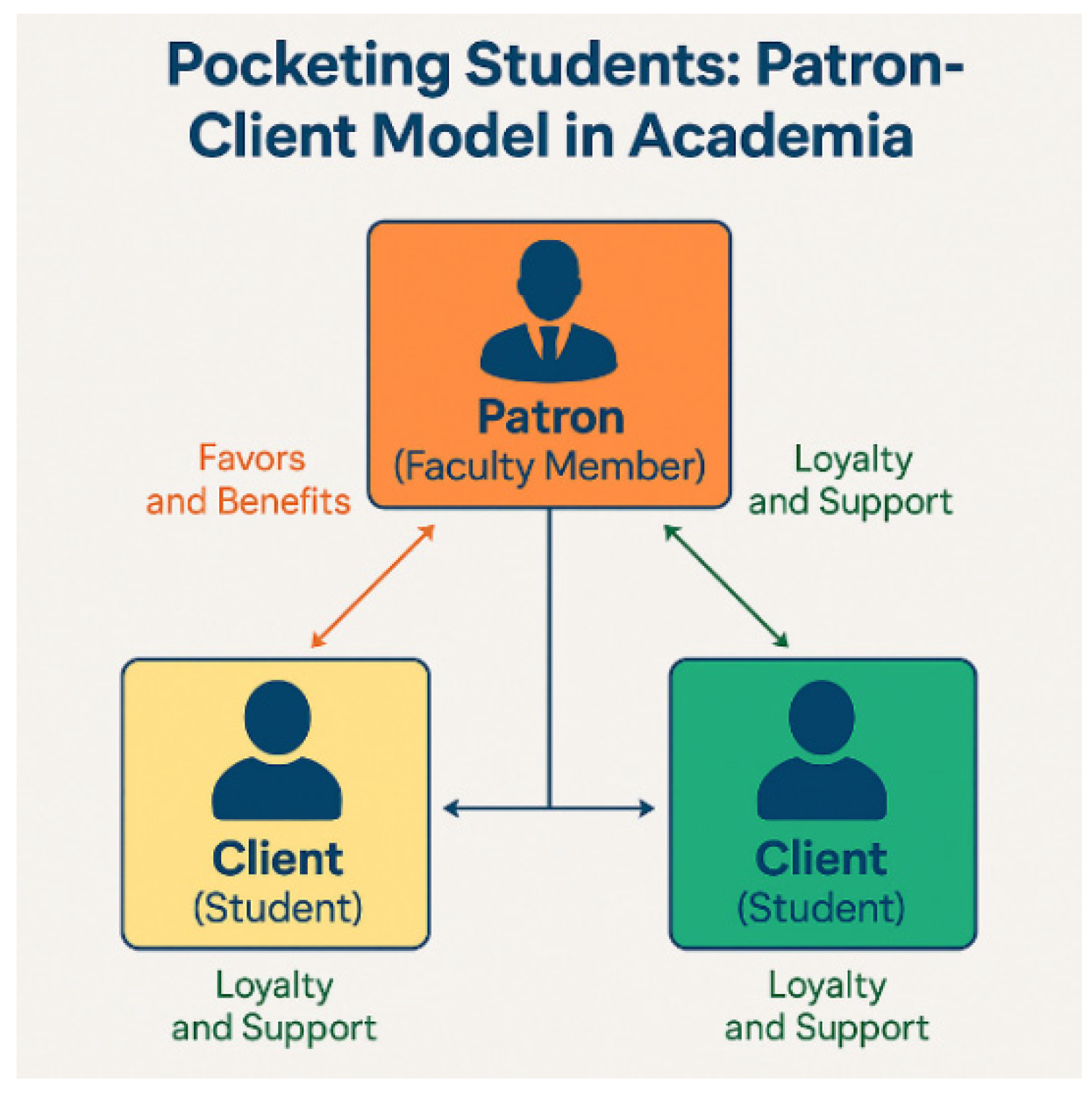

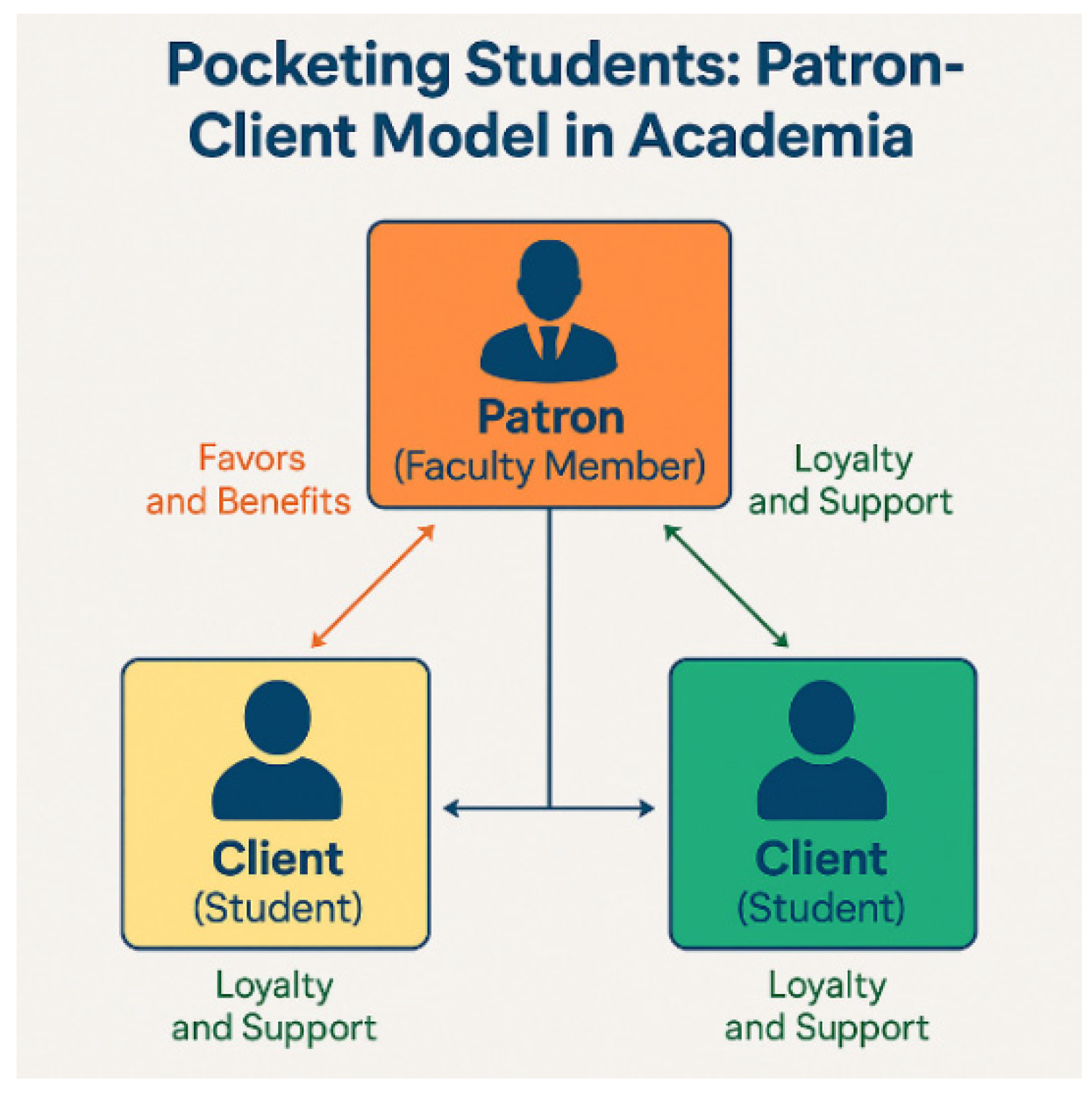

5.2. Pocketing Students: Patron-Client Model in Academia

Perhaps more damaging is the systemic practice of ‘student pocketing’, where faculty members cultivate personal groups of loyal students for their own political, personal, and academic leverage. This toxic patron-client relationship is sustained through:

Grade favoritism and manipulation of internal assessments.

Preferential treatment in internships, research projects, and conference participation.

Encouraging students to spy on peers or other faculty.

Using students to lobby for faculty promotions or administrative posts.

Discouraging dissent or critical thinking in favor of blind loyalty.

This model not only undermines the principles of equal opportunity and meritocracy but turns the educational process into a transactional, manipulative system. Students, in turn, become either passive dependents or opportunistic players in this power game, rather than autonomous learners or ethical communicators.

5.3. Consequences for the Academic and Ethical Environment

The outcomes of this embedded political-patronage system are dire:

- a)

Erosion of trust between students and teachers, leading to apathy, cynicism, and disengagement.

- b)

Suppression of intellectual diversity, as only politically aligned or ‘safe’ ideas are tolerated.

- c)

Normalization of unethical conduct, where students learn to succeed through loyalty and networking rather than talent and hard work.

- d)

Increased dropouts and psychological stress, as marginalized students feel alienated and unsupported.

- e)

Damaged institutional reputation, making it harder for departments to attract funding, partnerships, or credible faculty.

The integrity of MCJ education is compromised when political rivalry and personal gain become embedded in the classroom, turning knowledge production into a byproduct of political calculations rather than a democratic and ethical endeavor.

5.4. Reclaiming Academic Space: Policy and Structural Reforms

To mitigate these corrosive practices, the following interventions are critical:

Enforce strict codes of professional ethics that bar teachers from manipulating students or engaging in partisan factionalism.

Introduce anonymous student evaluations of faculty performance to highlight unethical practices.

Ensure transparent, merit-based assessment systems that reduce the space for favoritism.

Appoint ombudspersons or external monitors for academic departments to address grievances.

Foster a culture of democratic dialogue, where dissent and pluralism are protected, not penalized.

5.5. Towards Ethical Pedagogy and Democratic Education

Educational institutions, particularly those that train future journalists and communicators, must reflect values of transparency, fairness, and ethical accountability. Indoor politics and student pocketing are antithetical to these values. If unaddressed, they risk producing graduates who are not only professionally underprepared but also ethically compromised— a grave threat to both the media profession and society at large.

The future of MCJ education in Bangladesh thus demands not just technical reforms, but a moral reawakening within academia—one that prioritizes student growth over factional interests, and knowledge over control.

5.2. Pocketing Students: Patron-Client Model in Academia– A Focus Group Study on Rajshahi University MCJ

The phenomenon of ‘pocketing students’ in the Department of Mass Communication and Journalism at Rajshahi University (DoMCJRU) reflects a deeply ingrained patron-client model of academic relationships, where certain teachers cultivate personal networks of student followers who act as extensions of their influence. To investigate this issue more rigorously, a qualitative Focus Group Discussion (FGD) was conducted with 18 current students and recent graduates (2021–2024) of DoMCJRU. The findings were both revealing and troubling.

A. Design and Implementation of the Focus Group Study

Three separate focus group sessions were held between January and March 2025, each lasting approximately 90 minutes and involving 6 participants. The participants were selected to ensure diversity in academic standing, gender, political affiliations, and level of departmental involvement. The discussions were facilitated using semi-structured guidelines focused on themes such as faculty-student interaction, favoritism, access to academic resources, and perceived fairness.

All sessions were recorded with prior consent and transcribed for thematic analysis.

B. Thematic Findings from the Focus Group Discussions

Theme 1: Favor-Based Academic Privileges

Participants overwhelmingly confirmed the existence of preferential academic treatment based on loyalty to specific faculty members. This included:

Prior access to question patterns or potential exam topics.

Higher grades in internal assessments and practical exams without merit justification.

Selection for desirable extracurricular opportunities (workshops, seminars, media tours) based on alignment with a teacher’s faction.

One participant stated:

‘If you are in Sir’s good book, you don’t need to worry about passing or marks… even if you don’t perform, they will find a way to make you shine.’

Theme 2: Manipulative Guidance and Emotional Dependency

The ‘pocketing’ process often began with certain faculty members offering personalized guidance, small favors, or emotional support—which then evolved into an unspoken expectation of loyalty. Several students reported being subtly discouraged from interacting with rival faculty or expressing independent opinions.

‘Madam used to call a few of us regularly and discuss politics or ask us to give information about others. At first it felt like mentorship, but later it became suffocating.’

Theme 3: Silencing Dissent and Fear of Exclusion

Students outside these ‘pocket networks’ described feeling isolated or penalized. They were often:

Ignored during class discussions, even when well-prepared.

Excluded from academic projects or internships.

Victimized through unfair grading and harsh feedback.

One participant observed:

‘If you don’t follow them blindly, you are branded as arrogant or ungrateful… some of us just stopped speaking up.’

Theme 4: Instrumentalization in Departmental Politics

Participants noted that certain teachers used their favored students for departmental lobbying, especially during times of internal elections, curriculum disputes, or inter-teacher conflicts. These students would:

Write support letters or petitions.

Spy on opposition faculty or peers.

Amplify a faculty member’s social media narrative.

‘It’s like being a political pawn… students are dragged into teacher wars and if you try to stay neutral, you’re seen as weak or useless.’

C. Consequences of the Patron-Client Academic Culture

The focus group discussions highlight several damaging consequences of this model:

Erosion of academic meritocracy: Success becomes tied to proximity and loyalty, not talent or hard work.

Compromised student autonomy: Students are discouraged from independent critical thought, fearing academic retaliation.

Toxic departmental environment: A sense of mistrust and factionalism pervades both faculty and student communities.

Depression and demotivation: Marginalized students reported high levels of psychological stress and disengagement.

D. Student Recommendations for Reform

The participants suggested several reforms to dismantle the pocketing culture:

Anonymous student feedback and departmental audits.

Third-party monitoring of assessment fairness.

Rotational selection for academic privileges based on clear criteria.

Mentorship cells free from political or personal agendas.

As one student concluded:

‘We need teachers, not patrons… guides who inspire, not manipulate.’

The focus group study confirms that the patron-client dynamic within DoMCJRU is not an isolated or exaggerated perception but a structurally embedded pattern. If left unchecked, it will continue to corrupt the ethical and educational mission of journalism education. Systemic reforms, strong leadership, and the empowerment of student voices are critical to breaking this toxic cycle and restoring integrity to the academic space.

This study critically explored the multidimensional crisis engulfing Mass Communication and Journalism (MCJ) education in Bangladesh, with a particular focus on the Department of Mass Communication and Journalism at Rajshahi University (DoMCJRU). It reveals a troubling confluence of factors that contribute to the educational downturn, including outdated curricula, recycled examination patterns, surface-level pedagogical knowledge among faculty, and toxic departmental politics that prioritize personal gain over academic advancement.

The study reveals that repeated examination questions not only encourage rote memorization but also suppress intellectual engagement, creativity, and critical analysis—skills essential for students in media and communication fields. An outdated curriculum, lacking in contemporary media theories, digital journalism, and global communication competencies, fails to prepare graduates for the rapidly evolving media industry. This structural decay is further exacerbated by the presence of ‘surface-level teaching,’ where instructors demonstrate insufficient grasp of current trends, pedagogical methods, and transdisciplinary approaches—undermining their roles as academic leaders and role models.

Perhaps most disturbingly, this research exposes the deep entrenchment of faculty-driven partisan politics and the patron-client model of student management. The focus group discussions with students from DoMCJRU underscore how teachers’ factionalism and the practice of ‘pocketing’ students create a divisive academic climate where meritocracy, fairness, and critical inquiry are sidelined. The emotional and psychological toll on marginalized students, coupled with structural exclusion from opportunities, further depresses the academic ecosystem.

In synthesis, the decline of MCJ education in Bangladesh is not merely a curriculum issue; it is a systemic failure driven by bureaucratic inertia, unethical pedagogical practices, and authoritarian faculty-student dynamics. Without immediate reforms and a collective push for accountability, transparency, and modernization, journalism education in the country risks becoming irrelevant and even dangerous—producing graduates who are neither industry-ready nor ethically grounded.

Therefore, this research calls for:

Urgent curriculum revision in line with global media practices and critical pedagogy.

Transparent, varied, and analytical examination systems that reward originality over memorization.

Mandatory faculty development and training in media technologies, ethics, and critical theory.

Mechanisms to eliminate political partisanship and favoritism in academic decisions.

Strengthening of student autonomy and democratic participation in academic affairs.

This study concludes that the restoration of MCJ education in Bangladesh must begin with reimagining academic leadership, pedagogy, and ethical commitment, rooted in the values of intellectual honesty, pluralism, and social responsibility.

5.3. Making Errors and Unfamiliarity with Grading Systems: Crisis in Result Publication and Academic Assessment

In the ecosystem of higher education, especially in disciplines such as Mass Communication and Journalism (MCJ), assessment reliability and grading integrity are central to academic legitimacy. However, evidence from the Department of Mass Communication and Journalism at Rajshahi University (DoMCJRU) reveals a disturbing pattern of systematic errors in grading, misapplication of grading rubrics, and uninformed or negligent result publication practices by certain faculty members. This section explores how such deficiencies undermine academic credibility and student morale.

A. Institutional Incompetency in Grading Standards

Grading in the MCJ department often lacks standardization and consistency, partly due to the absence of department-wide evaluation rubrics, and partly because some faculty members are not adequately trained in modern assessment methods. In several instances, grades have been awarded without clear justification, and feedback is either unavailable or contradictory.

Students reported examples of:

Same answer scripts receiving different grades when reevaluated informally by peers or external faculty.

Absurd mark distribution, such as granting full marks for factual inaccuracies and deducting marks for critical insights.

Incomplete or arbitrary comments on assignments and practical reports, offering no learning value or future direction.

These errors are not always intentional but often stem from inadequate orientation with the Credit Hour System, GPA/CGPA models, and even basic statistical moderation techniques that are standard in university-level evaluations globally.

B. Careless Result Publication and Academic Harassment

The timing and accuracy of result publication have also become significant concerns. Several students noted:

Incorrect grade entries leading to unexpected failures or lower CGPA standings.

Delays in result finalization, impacting scholarship opportunities, job applications, and semester progression.

Unnotified changes in grades after publication, often without transparency or the student’s right to appeal.

One case involved a student whose CGPA was reduced due to a wrongly entered course grade. Despite multiple appeals, the mistake was not rectified in the official record. Such negligence not only reflects poor administrative oversight but also psychological and academic harassment of students.

C. Lack of Examiner Moderation and Peer Review

Unlike robust departments that apply double-checking mechanisms and inter-departmental moderation, the DoMCJRU often relies on single-examiner evaluations, especially in internal assessments. This lack of academic checks and balances contributes to misgrading and unchecked examiner bias.

Moreover, when questioned, some faculty members reportedly demonstrated a lack of familiarity with grade interpretation scales, marking schemes, and even the consequences of erroneous GPA calculations. This suggests a dire need for professional development in educational assessment and measurement.

D. Student Testimonies: A Pattern of Frustration

During the Focus Group Discussions, students shared that many errors could have been avoided if there were:

- a)

Departmental grievance cells.

- b)

External moderation boards.

- c)

Clear rubrics and answer keys.

- d)

Digital result tracking systems for verification before publication.

One student remarked:

‘We are told to accept our grades, but how do we trust a system where even the teachers don’t know the grade points? It’s demoralizing.’

E. Policy Recommendations

Mandatory training for all faculty members on assessment rubrics, GPA calculation, and the use of Learning Management Systems (LMS).

Introduction of internal moderation panels to verify grades before publication.

Standardized rubrics and grading criteria to ensure transparency and consistency.

Digital submission and tracking platforms that allow students to access their marked scripts.

Establishment of an academic grievance committee empowered to investigate and resolve grade-related issues independently.

This section makes it clear that errors in grading and unfamiliarity with assessment protocols are not mere accidents but systemic indicators of a failing academic culture, particularly within MCJ departments like that of Rajshahi University. These flaws not only disrupt student futures but also corrode trust in the entire educational process.

5.4. Errors in Grading and Failing Academic Assessment Protocols: A Crisis of Academic Integrity in Journalism Education

The Invisibility of a Pedagogical Crisis

In an academic discipline where truth, accuracy, and responsibility are foundational principles—as in Mass Communication and Journalism—it is paradoxical and deeply troubling that academic assessment mechanisms themselves suffer from fundamental errors and ethical breaches. At the Department of Mass Communication and Journalism, Rajshahi University (DoMCJRU), grading inconsistencies, structural lapses, and failure to uphold evaluative standards have emerged as serious issues, with cascading effects on student performance, psychological well-being, and institutional credibility. These issues point not only to isolated mistakes but to a systemic failure of academic governance and assessment culture.

A. Systematic Errors in Grading: A Structural Flaw, Not Random Anomalies

One of the most alarming findings from focus group discussions and interviews with students and junior faculty is the recurrence of grading errors that appear across semesters and batches. These are not random computational mistakes but are embedded in deeper dysfunctions such as:

Use of outdated or inconsistent marking rubrics, where faculty members follow personal standards in the absence of a department-wide evaluation protocol.

Mechanical and arbitrary allocation of marks—especially in theory courses—where subjective bias, favoritism, or fatigue influence assessments more than academic merit.

Copy-paste evaluation culture, where assignments and practical reports are evaluated without thorough reading or understanding.

In one documented case, students from the same batch who submitted identical content in a group project received drastically different grades due to careless marking or a possible bias against specific individuals.

B. Inadequate Understanding of Grading Systems Among Faculty

A particularly concerning aspect of assessment failure is faculty ignorance regarding modern grading systems, including the GPA/CGPA calculation model, credit hour-based assessments, or cumulative grade moderation. Some teachers—especially those appointed under politically motivated or non-meritocratic circumstances—reportedly:

Confuse percentage-based systems with grade point averages, miscalculating results with no clarity about cut-off marks for letter grades.

Fail to maintain proper records of internal assessments, leading to last-minute mark fabrication or guesswork.

Demonstrate resistance to digital grading tools like university portals, LMS, or spreadsheet evaluations, preferring handwritten notes prone to error.

This leads to multiple consequences: grade mismatches, unaccounted coursework, and unjust penalization of students. It also exposes the lack of institutional investment in capacity-building training or continuous professional development.

C. Result Publication: A Recurrent Site of Student Harassment

Even when grading is complete, result publication processes are marked by opacity, delay, and error-proneness. Several students at DoMCJRU reported the following:

Grades altered post-publication without official explanation or student consent.

Grades missing from transcripts due to clerical errors or negligence by the examination committee.

Delayed results affecting applications for jobs, scholarships, or higher education.

In many cases, students are neither notified of changes nor given access to re-evaluation options. The absence of a robust appeals or moderation process results in emotional trauma, academic disadvantage, and a loss of trust in institutional systems. The power imbalance between faculty and students further discourages victims from raising their voices due to fear of retaliation.

D. Impact on Student Learning and Mental Health

The long-term effects of flawed grading systems are far-reaching:

Demotivation and learned helplessness, where students begin to see performance as irrelevant to outcomes.

Mental health deterioration, including anxiety, depression, and self-doubt due to unpredictable academic evaluation.

Grade inflation or deflation, which misrepresents actual competencies and erodes the department’s academic credibility.

As one student noted in a focus group:

‘I studied hard for weeks, followed the rubric, and still failed. My friend copied from the internet and passed. It’s not about what you write, it’s who marks it.’

This situation creates an anti-intellectual culture, where performance and rigor are replaced by guessing, lobbying, or silence.

E. Institutional Negligence and Absence of Corrective Mechanisms

The responsibility for this crisis cannot be laid solely on individual faculty. Institutional structures have failed to implement checks and balances. There is no:

Audit system for result verification.

Grievance redressal committee for student appeals.

External evaluation system (such as anonymous double-blind assessments).

Standardized rubric training during orientation or yearly academic workshops.

Moreover, university syndicates and academic councils often overlook student petitions and treat grading errors as minor infractions, ignoring their profound consequences.

F. Policy Recommendations: Toward a Transparent and Accountable Assessment Culture

To restore integrity and fairness in academic assessment, the following reforms are essential:

Institutionalization of standardized rubrics for each course and assessment type, publicly shared with students.

Mandatory annual training for faculty on grading systems, GPA/CGPA calculations, and digital result management.

Deployment of digital grading systems with cross-verification and student access.

Creation of a Student Assessment Review Board (SARB) to evaluate claims of grading injustice.

External moderation panel composed of faculty from other departments/universities to review and validate critical evaluations.

The crisis in grading and assessment protocols within MCJ departments like DoMCJRU is not a marginal issue; it strikes at the heart of academic justice and educational credibility. When grading becomes unreliable, the entire pedagogical promise collapses. Students lose motivation, faculty lose legitimacy, and institutions lose trust. Addressing these systemic failures requires not just policy changes but a cultural shift toward transparency, accountability, and academic professionalism. Journalism students—who are future watchdogs of society—deserve no less.

5.5. Pocketing Students and Manipulating Dishonesty: The Psychedelic Crisis of Teachers in Mass Communication and Journalism Education

Introduction: From Mentorship to Manipulation

In the classical academic tradition, teachers serve as mentors, facilitators of intellectual growth, and ethical models for their students. However, within the Department of Mass Communication and Journalism at Rajshahi University (DoMCJRU), the relationship between students and some faculty members has been increasingly marked by clientelism, psychological manipulation, favoritism, and dishonest practices that derail the academic journey. This phenomenon can be described as a ‘psychedelic crisis’ of the teaching profession—a metaphorical disorientation and ethical hallucination where academic responsibility is replaced by egotism, dependency-building, and institutional corruption.

A. The Practice of ‘Pocketing Students’

‘Pocketing students’ refers to the informal yet highly structured practice whereby teachers co-opt select students into personal loyalty networks, often disguised as academic mentorship. These relationships are not built on intellectual merit, research interests, or pedagogical guidance but on:

Political loyalty, where students are aligned with faculty-backed student factions.

Personal errands, where students act as informal assistants, managing social media, arranging travel, or performing clerical work.

Emotional dependency, where faculty foster obedience and silence by rewarding allegiance with marks, job recommendations, or scholarships.

This behavior undermines fair academic competition and replaces meritocracy with patron-client networks, creating a toxic departmental culture.

B. Manipulating Dishonesty in Academic Practices

Several student testimonies reveal that some teachers not only favor their ‘pocketed students’ but also involve them in dishonest academic practices, including:

Leaking exam questions in advance to selected individuals.

Allowing plagiarism or ghostwriting in return for personal favors.

Suppressing complaints against themselves by using pocketed students as enforcers or informants.

Encouraging online trolling or bullying of dissenting voices through social media networks.

This manipulation is not merely unethical—it creates a culture of fear, silence, and internalized normalization of corruption. Many students report being forced into this system to avoid academic or political retaliation.

C. The ‘Psychedelic’ Crisis: Teachers Detached from Pedagogical Reality

The term psychedelic in this context refers to the disorienting and delusional detachment from the ethical and intellectual responsibilities of teaching. Several faculty members behave as though:

They are untouchable figures of authority, immune to accountability.

Subjectivity overrides evaluation, and personal liking determines grades or opportunities.

Pedagogy is secondary to power, control, and influence within the university’s bureaucratic and political ecosystem.

This delusion fosters abuse of power, erosion of academic standards, and psychological distress among students. The role of a teacher as a facilitator is replaced by that of a gatekeeper of favor.

D. Student Impact: Psychological and Academic Damage

The manipulation and exploitation by faculty under this patron-client structure have led to:

Fear-driven silence among students who choose not to speak out.

Erosion of peer solidarity, as favoritism breaks community bonds.

Internalized inferiority, where students outside the network believe they cannot succeed based on merit alone.

Academic demotivation, as critical thinking and independent inquiry are discouraged.

One student reported:

‘If you are not in their pocket, you are invisible. Even your best efforts won’t get you noticed, let alone graded fairly.’

E. Recommendations to Disrupt Pocketing and Manipulation

To dismantle this unethical structure, several interventions must be institutionalized:

Adopt a code of academic ethics and require annual compliance declarations from all faculty members.

Establish anonymous reporting mechanisms for students to report favoritism, coercion, or abuse.

Create independent faculty-student liaison committees with student representation.

Institute random audits of evaluations and viva processes to ensure transparency.

Ban non-academic relationships that can create dependency or conflict of interest in grading and mentoring.

The psychedelic crisis of teachers in departments like DoMCJRU symbolizes a larger collapse of educational ethics, pedagogical integrity, and institutional accountability. By manipulating students and commodifying academic relationships, certain faculty members are not only betraying their roles but also engineering a generation of journalists untrained in fairness, objectivity, and courage. A systematic effort is required to restore education as a public good, and teachers as ethical stewards—not political players or egoists.

Clientelism in higher education refers to the practice where academic resources, opportunities, or evaluations are distributed based on personal loyalty, political affiliation, or social connections rather than merit. This phenomenon undermines academic integrity and perpetuates inequality within educational institutions.

1. Political Clientelism in Higher Education

In many developing countries, political clientelism manifests when political elites use control over educational resources to secure loyalty from students and faculty. This often involves distributing scholarships, research grants, or faculty appointments based on political allegiance rather than academic qualifications. Such practices can lead to the misallocation of resources, where funds intended for educational development are diverted to reward political supporters, thereby ‘crowding out’ genuine educational investments and ‘degrading’ the quality of education (Haohan Chen and Herbert Kitschelt (2022).

2. Nepotism and Favoritism in Academic Appointments

In Italy, studies have highlighted the prevalence of favoritism in academic recruitment processes. Research indicates that the most significant determinant for career advancement in academia is not scientific merit but rather personal connections, such as the number of years a candidate has been affiliated with the same university as the selection committee president. Additionally, joint research collaborations with committee members significantly increase a candidate’s chances of success (Giovanni et al. 2018).

3. Clientelism in Post-Communist Eastern Europe

In post-communist countries like Albania, political clientelism has been observed in the higher education sector. Studies suggest that political engagement and patronage networks significantly influence employment pathways in academia. Individuals with political connections often secure academic positions and promotions, regardless of their qualifications, leading to a system where merit is secondary to political affiliation.

4. Authoritarian Regimes and Academic Patronage

In authoritarian regimes, clientelism can become institutionalized, with political leaders using control over educational institutions to maintain power. For example, in Hungary, the government has been accused of using educational institutions to reward political loyalty, thereby consolidating power and suppressing dissent. This creates an environment where academic freedom is compromised, and education serves as a tool for political control.

5. Gender Bias and Favoritism in Academic Recruitment

Gender bias also plays a role in clientelism within academia. Studies in Italy have found that while women in academic selection committees tend to give more weight to scientific merit, favoritism still exists. In particular, candidates who have collaborated on research projects with committee members are more likely to succeed, indicating that personal connections continue to influence academic appointments.

Clientelism in higher education is a multifaceted issue that affects various aspects of academic life, from admissions and appointments to resource allocation. Addressing this problem requires systemic reforms, including the establishment of transparent evaluation processes, the promotion of merit-based recruitment, and the safeguarding of academic freedom. Only through such measures can the integrity and quality of higher education be preserved.

Here are some examples of political favoritism affecting resource distribution in higher education:

1. Scholarships and Funding Allocations Based on Political Loyalty

In several developing countries, governments or ruling parties have been known to distribute scholarships, grants, and research funds preferentially to students and faculty who show allegiance to the party or political leaders. This undermines merit-based awarding and diverts resources away from more deserving candidates (Chen & Kitschelt, 2018).

2. Faculty Appointments and Promotions Influenced by Political Connections

In countries like Albania and parts of Eastern Europe, academic appointments and promotions are often tied to political patronage networks. Individuals with political ties or party membership are given preferential access to university positions, regardless of their academic merit (Golemis et al., 2022).

3. Use of University Resources for Political Campaigns or Factional Advantage

In some authoritarian regimes, universities have been pressured to use their resources—such as facilities, student bodies, or academic platforms—to support ruling party campaigns or suppress opposition groups, effectively channeling educational resources to political ends (Transparency International, 2020).

4. Manipulation of Research Funding

Research grants are sometimes distributed to projects that align with government narratives or political agendas, sidelining independent or critical scholarship. This political favoritism skews research priorities and stifles academic freedom (Altbach, 2015).

5. Political favoritism

Political favoritism in Bangladesh’s higher education often manifests in appointing politically affiliated individuals to key university positions, awarding scholarships linked to party loyalty, and skewing examination and grading processes to favor students connected to political groups (Rahman & Sultana, 2019).

5.6. Ideological Favoritism in Academia: Shaping Education Beyond Merit

Ideological favoritism refers to the preferential treatment of students, faculty, or academic content based on alignment with particular political, religious, or social beliefs, rather than objective academic merit. In higher education institutions, this form of favoritism distorts the academic environment by privileging conformity over critical inquiry and independent thought.

A. Manifestations of Ideological Favoritism

Curriculum Design and Content: Academic programs may be influenced to reflect the dominant ideology favored by faculty or administrative leadership, limiting exposure to diverse perspectives. This can lead to curriculum bias where dissenting or alternative viewpoints are marginalized or excluded (Kumar & Jha, 2017).

Hiring and Promotion: Faculty members who share or promote the prevailing ideological stance of the institution or its governing bodies are often preferred during hiring, tenure, and promotion decisions, sidelining scholars with dissenting or minority viewpoints (Morrison, 2019).

Student Evaluation: Students expressing views contrary to the dominant ideology may face harsher grading or academic neglect, while those aligning with favored ideologies may receive undue academic benefits, reinforcing ideological conformity (Smith & Lee, 2020).

Research Funding and Publication: Research that supports institutional or political ideologies is more likely to receive funding and publication opportunities, suppressing critical or oppositional scholarship (Altbach, 2015).

B. Consequences for Academic Freedom and Quality

Ideological favoritism undermines the fundamental principles of academic freedom and intellectual diversity. When ideas are valued based on political correctness or ideological alignment rather than evidence and reasoning, the quality of education and research suffers. This environment discourages critical thinking, innovation, and open debate—core pillars of robust academia (Giroux, 2014).

C. Examples from Global and Local Contexts

In several countries, universities have faced criticism for enforcing ideological conformity, such as promoting nationalism or religious orthodoxy at the expense of academic neutrality (Johnson, 2018).

In Bangladesh, some studies report ideological favoritism linked to political party allegiances and religious influences impacting faculty recruitment, student assessments, and curriculum choices, contributing to educational decline in departments like Mass Communication and Journalism (Rahman & Islam, 2020).

D. Policy Recommendations

Establish transparent and merit-based hiring, promotion, and evaluation criteria that explicitly safeguard against ideological bias.

Ensure curriculum committees include diverse stakeholders to promote pluralistic content.

Implement mechanisms to protect academic freedom, enabling faculty and students to express diverse perspectives without fear of reprisal.

Promote independent oversight bodies to monitor ideological impartiality in academic decisions.

Establish structural Alumni Association according to University and UGC rules.