1. Introduction

Plastic pollution has emerged as a critical global challenge, with more than 400 million metric tons of plastic produced annually [

1,

2] and approximately 8-11 million metric tons entering the oceans each year [

3,

4]. A substantial portion of this waste is derived from single-use and non-degradable plastics, which persist in the environment for hundreds of years, contributing to the accumulation of microplastics in terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems [

5]. The environmental and public health impacts of plastic pollution have prompted increasing global concern and have led many countries to develop national strategies and regulatory frameworks to reduce dependence on conventional plastics [

6,

7,

8].

Vietnam ranks among the top contributors to global marine plastic pollution, discharging approximately 0.28 to 0.73 million metric tons of plastic waste into oceans annually, with 72% stemming from single-use plastics [

9,

10,

11]. Rapid urbanization, population growth, and industrial expansion have exacerbated plastic consumption, leading to severe environmental impacts, including widespread microplastic contamination in water systems and coastal ecosystems [

12]. The persistence of non-degradable plastics poses long-term ecological threats, highlighting the urgent need for sustainable alternatives [

13]. In response, Vietnam has launched several initiatives, including the National Action Plan for Management of Marine Plastic Litter (2020–2030), targeting a 50% reduction by 2025 and 75% by 2030 [

9,

14]. Complementary policies aim to ban the production and import of plastic bags by 2026 and phase out most single-use plastics by 2031 [

15]. These measures, combined with economic incentives and research funding, promote the adoption of biodegradable materials such as polylactic acid (PLA), which offers a promising alternative due to its biodegradability, renewable origin, and alignment with Vietnam’s Green Growth Strategy and international sustainability goals.

Bioplastics, classified based on raw materials and biodegradability, represent an emerging class of eco-friendly materials capable of reducing dependence on fossil fuels and minimizing environmental pollution [

16].

Table 1 provides an overview of key bioplastic types, including starch-based plastics, cellulose-based plastics, chitosan-based plastics, seaweed-based plastics, PLA, PHA, PHB, and bio-based PE, detailing their sources, biodegradability, processing methods, strengths, and limitations. Among these, PLA has gained significant attention for its production from renewable feedstocks like corn starch and sugarcane [

17]. PLA’s industrial compostability and ability to degrade into water and carbon dioxide under controlled conditions address waste management challenges, while its production consumes 25–55% less energy than conventional plastics, resulting in lower carbon emissions [

18].

Table 2 compares PLA’s mechanical and thermal properties with PET and PS, demonstrating competitive tensile strength and modulus, although its thermal resistance and flexibility require enhancement for broader applications.

Global production of PLA is expanding, with major manufacturers operating in North America, Europe, and Asia. However, despite growing market interest, the scaling of PLA production technologies faces several challenges [

18]. These include high production costs, limited thermal and mechanical performance, and difficulties in processing using conventional plastic fabrication equipment [

19]. Addressing these barriers requires research focused on optimizing fermentation and polymerization processes, developing new catalysts, and incorporating additives to improve thermal stability and mechanical strength [

20,

21]. Collaboration among research institutions, industry stakeholders, and policymakers is essential for advancing bioplastic manufacturing capacity worldwide. Such coordinated efforts can drive technological innovation, support economic development, and accelerate the transition toward sustainable materials. Strengthening global partnerships will be key to scaling bioplastics like PLA, supporting circular economy models, and addressing the escalating plastic pollution crisis on an international scale.

Moreover, one of the major barriers to widespread PLA adoption is the lack of standardized production protocols and certification frameworks. Inconsistent product quality, variable biodegradability under different conditions, and the absence of harmonized standards across countries hinder the integration of PLA into mainstream plastic supply chains. Efforts by organizations such as the European Committee for Standardization and the ASTM International have led to the development of testing standards for compostability and biodegradability, but a global consensus on production and performance criteria remains limited. This gap not only affects market confidence but also limits the potential for national policy integration.

Recognizing these limitations, several governments have incorporated bioplastic development into broader sustainability agendas [

22,

23]. For instance, the European Union’s Green Deal and Circular Economy Action Plan emphasize reducing plastic waste and promoting bio-based alternatives [

24,

25]. Similarly, Japan’s Bioplastic Roadmap [

26,

27] and the United States’ BioPreferred Program [

25,

28] incentivize the research, development, and procurement of bioplastics such as PLA. These initiatives underscore the importance of aligning technological innovation with regulatory and economic instruments, including public procurement policies, tax incentives, and investment in infrastructure for composting and recycling.

In addition to its technical and environmental merits, the successful adoption of polylactic acid (PLA) as a sustainable alternative to conventional plastics also hinges on the establishment of regulatory frameworks and international standards [

4,

27,

29,

30]. Standardization efforts are crucial for ensuring the safety, performance, and environmental integrity of PLA-based products. Globally recognized organizations such as ASTM International and the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) have developed a series of standards that define aceebiodegradability, compostability, and product labeling. For instance, ASTM D6400 and ISO 17088 outline specifications for compostable plastics under industrial composting conditions, while EN 13432 is widely used in Europe to certify packaging materials' compostability.

Moreover, government policies and national strategies are playing a growing role in supporting PLA innovation and market growth [

31]. The European Union has enacted comprehensive legislation under the European Green Deal and Circular Economy Action Plan, including restrictions on single-use plastics and incentives for biodegradable alternatives [

25]. Countries like Germany and France have introduced extended producer responsibility (EPR) schemes and public funding programs for bioplastic research. Similarly, the United States supports PLA development through initiatives such as the BioPreferred Program administered by the U.S. Department of Agriculture, which promotes biobased products in federal procurement [

28].

Figure 1.

Circular Economy Model for the Production and Biodegradation of Polylactic Acid (PLA).

Figure 1.

Circular Economy Model for the Production and Biodegradation of Polylactic Acid (PLA).

In Asia, nations including Japan, South Korea, and China have implemented national plastic reduction roadmaps that explicitly encourage the use of bioplastics. Japan’s Biomass Plastic Introduction Roadmap, for example, sets a target of replacing 2 million tons of conventional plastics with bioplastics, including PLA, by 2030. These policies not only create favorable market conditions but also encourage investment in domestic PLA production capacity and innovation in end-of-life solutions such as composting and chemical recycling [

32].

Despite these advances, inconsistencies in certification standards, inadequate composting infrastructure, and limited public awareness remain challenges that must be addressed through coordinated international efforts [

27]. Establishing harmonized global standards and supportive policy mechanisms will be essential to unlock PLA’s full potential and ensure its effective integration into sustainable material systems [

30].

This review examines the current state of PLA manufacturing technologies, highlighting key innovations in fermentation, polymerization, and materials engineering. It also analyzes the role of standardization efforts and policy frameworks in supporting national transitions toward bioplastic adoption. By bridging technological readiness with policy implementation, countries can create enabling environments for PLA to become a viable and scalable alternative to conventional plastics. Such alignment is critical not only to mitigate environmental damage but also to stimulate green innovation, build domestic manufacturing capacity, and position nations competitively within the emerging global bioplastics market.

2. PLA in the World

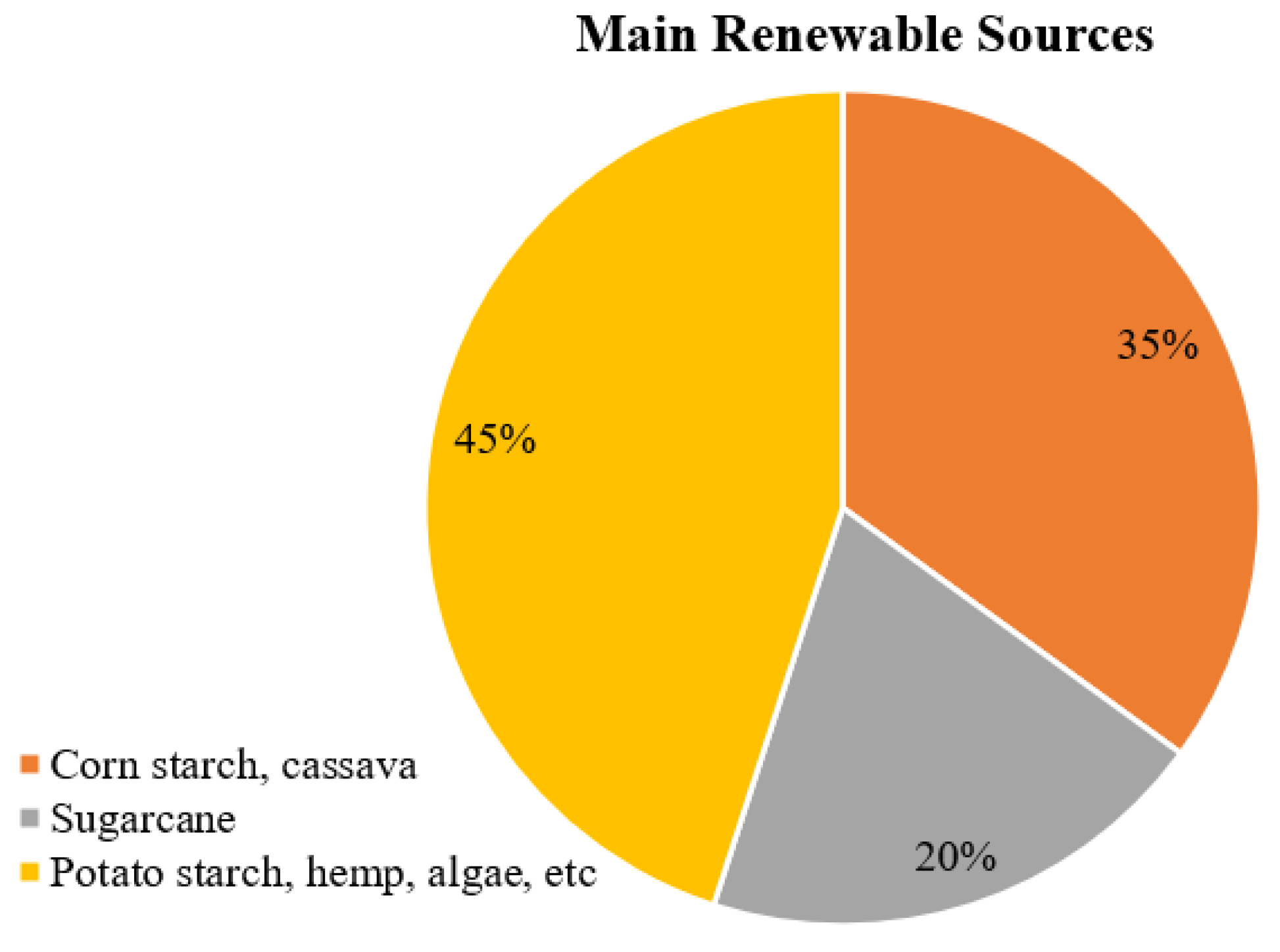

2.1. Potential for Utilizing Renewable Resources

The global shift toward sustainable materials is closely tied to the availability and utilization of renewable resources that serve as feedstocks for bioplastics [

33,

34]. Polylactic acid (PLA), one of the most commercially successful bioplastics, is derived primarily from fermentable sugars obtained from crops such as corn, sugarcane, cassava, and beetroot. These crops are cultivated in abundance across various regions, offering significant opportunities for large-scale, decentralized PLA production and reducing reliance on fossil-derived polymers. [

35]

Globally, the agricultural potential for supplying PLA feedstocks is robust [

36]. The United States and Brazil, for example, lead the world in corn and sugarcane production, respectively—two of the most common sources of fermentable sugars for PLA synthesis [

37,

38]. In Asia, countries such as Thailand, India, and China also possess extensive sugar and starch crop outputs, enabling regional supply chains for PLA manufacturing [

39,

40,

41,

42]. It is estimated that less than 0.05% of global agricultural land is currently used for bioplastics feedstock cultivation, indicating substantial room for growth without significantly impacting food security.

In addition to traditional crops, emerging feedstocks such as agricultural residues, algae, and industrial waste streams offer promising pathways to produce lactic acid through non-food-based biomass conversion [

43,

44]. Advancements in biorefinery technologies, including enzymatic hydrolysis and microbial fermentation, have increased the feasibility of extracting high yields of lactic acid from lignocellulosic biomass [

45,

46,

47]. These innovations not only diversify the resource base but also promote circular economy principles by utilizing waste as a resource.

The strategic integration of renewable resources into PLA production aligns with global sustainability goals, particularly the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), including SDG 9 (industry, innovation, and infrastructure), SDG 12 (responsible consumption and production), and SDG 13 (climate action) [

48]. Moreover, using bio-based feedstocks contributes to lower greenhouse gas emissions across the PLA life cycle, as biomass absorbs CO₂ during cultivation, partially offsetting emissions from processing and disposal stages [

32,

49].

Despite this potential, several barriers persist to fully harnessing global renewable resources for PLA production. These include the need for infrastructure investment, regional disparities in biomass availability, and competition with food and feed markets. Furthermore, conversion efficiencies and energy demands during fermentation and polymerization processes vary widely depending on feedstock type and technology used, influencing both the cost and environmental performance of PLA.

To overcome these challenges, various governments and regional bodies are supporting feedstock development programs, promoting sustainable agriculture practices, and investing in next-generation biorefineries. For example, the European Union’s Bioeconomy Strategy emphasizes the use of local biomass for industrial applications, while the United States Department of Agriculture’s BioPreferred Program supports the commercialization of biobased products through labeling and procurement incentives. In Asia, countries such as Thailand and Japan have established national roadmaps for bioplastics development, which include targets for increasing domestic biomass utilization and building PLA manufacturing capacity.

Vietnam's abundant renewable resources present a significant opportunity to enhance its energy portfolio and reduce reliance on fossil fuels [

50,

51]. The country is endowed with substantial potential in solar, wind, biomass, and hydropower. Solar energy potential is estimated at approximately 963 gigawatts (GW), with average solar radiation ranging from 4 to 5 kilowatt-hours per square meter per day [

52,

53]. Wind energy potential is also considerable, particularly in coastal regions and the central highlands, with technical potential estimated at around 1,000 GW [

54]. Biomass resources, derived from agricultural residues such as rice husks and straw, offer an estimated potential of 2,565 megawatts (MW) [

55]. Hydropower remains a significant contributor, with an estimated potential of 35,000 MW, of which approximately 17,000 MW has been exploited [

56].

Despite this vast potential, the integration of renewable energy into Vietnam's energy mix has been limited (

Figure 2). As of 2020, renewable energy sources accounted for approximately 10% of the total installed capacity, with hydropower being the dominant contributor. The government has set ambitious targets to increase the share of renewable energy, aiming for 30.9% to 39.2% by 2030 and 47% by 2050 [

57,

58]. Achieving these targets necessitates substantial investments in infrastructure, policy reforms, and technological advancements. Challenges such as high initial capital costs, limited grid capacity, and regulatory hurdles must be addressed to facilitate the integration of renewable energy sources. To capitalize on its renewable energy potential, Vietnam has implemented several policy initiatives. The Power Development Plan VIII (PDP8) outlines strategies to enhance renewable energy development, including the establishment of renewable energy zones and incentives for private sector investment [

59,

60]. Additionally, the government has introduced feed-in tariffs and tax incentives to encourage the adoption of renewable energy technologies. International cooperation and investment play a crucial role in advancing Vietnam's renewable energy sector.

In summary, the global potential for renewable resource utilization in PLA production is substantial and underexploited. Strengthening agricultural-industrial linkages, expanding the use of non-food biomass, and aligning national policies with sustainability goals are key to scaling up PLA production while minimizing environmental trade-offs. Harnessing this potential through technological innovation and international cooperation will be essential for advancing a sustainable global bioplastics industry.

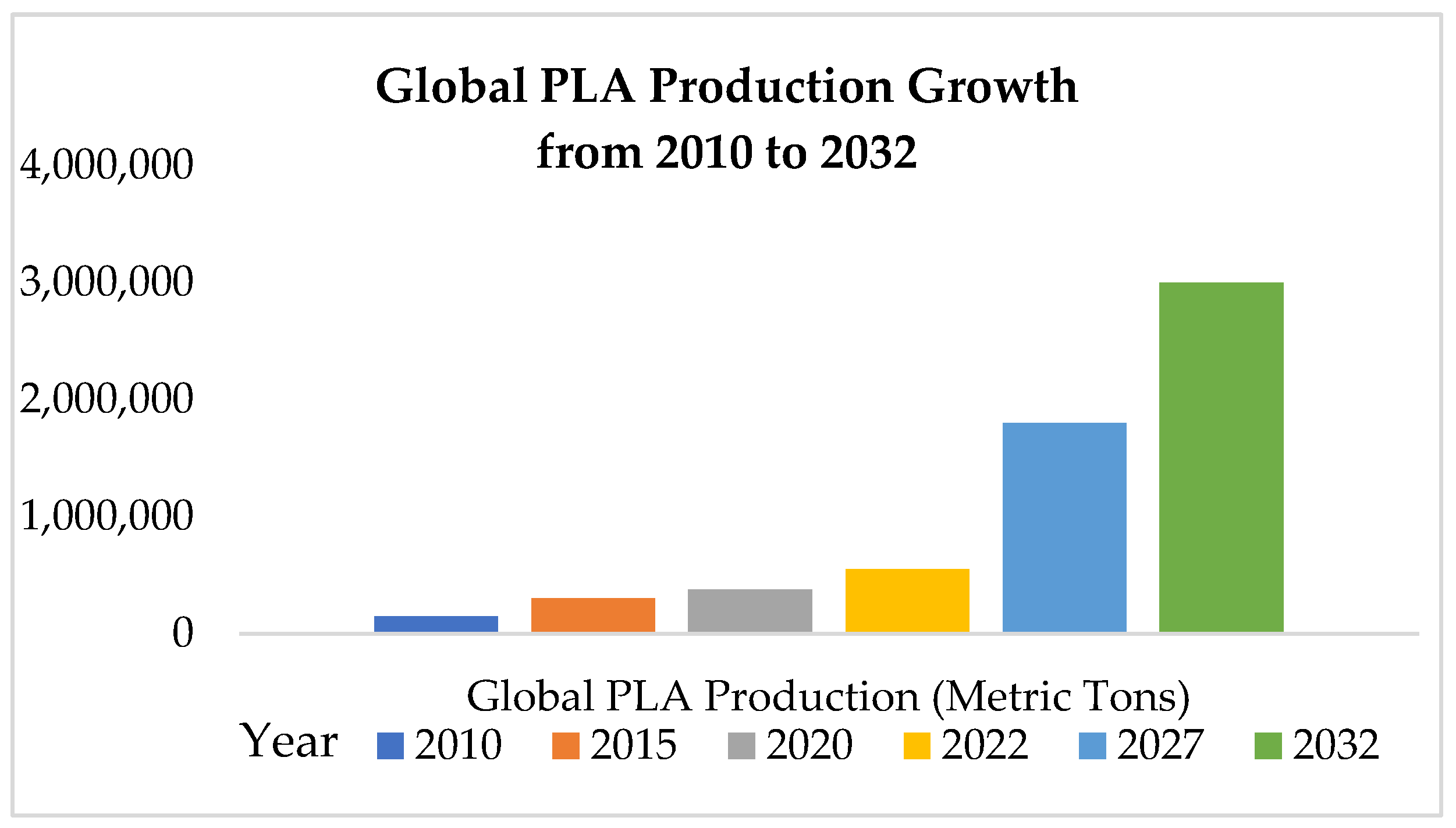

2.2. Scale and Growth Rate of the Global Bioplastic Market

The global bioplastics industry has undergone rapid expansion in the past decade, fueled by rising environmental concerns, tightening regulations on single-use plastics, and increasing demand for sustainable alternatives. In 2023, the global bioplastics market was valued at approximately USD 14.5 billion, with polylactic acid (PLA) accounting for nearly 13% of total bioplastics production by volume [

1,

61]. The industry is projected to grow at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 17–20%, reaching a market size of over USD 45 billion by 2032 [

62,

63,

64]. This growth reflects not only increased consumer awareness but also strategic policy shifts in both developed and emerging economies.

Bioplastics are being increasingly adopted across diverse end-use sectors, including packaging, agriculture, automotive, textiles, consumer electronics, and medical applications. The packaging industry remains the dominant consumer, representing nearly 60% of global demand in 2023, primarily for food containers, films, and shopping bags [

65]. PLA, with its clarity, printability, and industrial compostability, has become a material of choice for rigid and flexible packaging, as well as for 3D printing filaments and single-use utensils.

Geographically, Europe and Asia-Pacific are leading in bioplastic production and consumption. Europe continues to play a central role in policy development and investment, supported by frameworks such as the EU Green Deal, the Plastics Strategy, and extended producer responsibility (EPR) schemes. The Asia-Pacific region, led by China, Japan, Thailand, and South Korea, benefits from abundant agricultural feedstocks and increasingly sophisticated biopolymer manufacturing capacity. North America, meanwhile, has seen steady market growth driven by the United States' BioPreferred Program, municipal composting mandates, and corporate sustainability commitments from multinational brands.

Despite optimistic projections, the global bioplastics industry still faces significant technical, economic, and infrastructural challenges. High production costs remain a barrier to scaling, largely due to expensive feedstocks, limited economies of scale, and the energy-intensive nature of certain fermentation and polymerization processes [

66,

67,

68]. While the cost of PLA has declined in recent years, it still remains 20–80% more expensive than conventional petrochemical plastics in many markets [

23,

32,

70,

71].

Moreover, end-of-life management for bioplastics remains inconsistent across regions. While materials like PLA are industrially compostable, many countries lack the infrastructure to process them appropriately. If not properly collected and treated, bioplastics can contaminate conventional recycling streams or fail to degrade under ambient environmental conditions, reducing their ecological benefits [

72]. Harmonizing global standards for labeling, disposal, and certification is therefore critical to unlocking the full environmental potential of PLA and other bioplastics.

To address these challenges, governments and private stakeholders are increasing investments in research and development (R&D) to improve process efficiency, develop next-generation PLA composites with enhanced thermal and mechanical properties, and design biodegradable products tailored for regional waste systems [

73]. At the same time, public-private partnerships are emerging as key enablers of innovation. Multinational companies such as Danone, Nestlé, and Coca-Cola have launched pilot projects using PLA packaging, while governments are offering incentives for local manufacturing, green procurement mandates, and bioplastics innovation hubs [

74,

75,

76].

Looking forward, the global PLA market is expected to play a pivotal role in the transition toward climate-resilient and circular economies. Its success will depend on synchronized efforts among researchers, policymakers, industry actors, and civil society. Scaling PLA adoption at the national level will require the development of production standards, supportive fiscal policies, and robust waste management strategies to ensure that environmental gains are realized across the entire lifecycle—from farm to factory to final disposal.

2.3. Economic Challenges Production and Distribution

Despite the growing global demand for sustainable materials, the production and distribution of polylactic acid (PLA) continue to face notable economic constraints that hinder its competitiveness against conventional petrochemical-based plastics. These challenges are especially pronounced in developing economies but are also relevant across industrialized nations striving to establish domestic PLA supply chains.

One of the most pressing issues is high production costs, largely driven by the price of renewable feedstocks, the complexity of fermentation and polymerization technologies, and the absence of large-scale economies. Globally, the cost of producing PLA remains 20% to 80% higher than traditional plastics like polyethylene (PE) or polystyrene (PS) [

77,

78]. While feedstocks such as corn, sugarcane, and cassava are renewable, their availability and pricing are subject to seasonal variation and competition with food markets, which can elevate input costs. Additionally, the biotechnological processes used to convert sugars into lactic acid, followed by ring-opening polymerization, are energy-intensive and capital-intensive, requiring advanced equipment and skilled labor [

37,

79,

80].

These cost barriers are compounded by limited access to financing, especially for small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) in emerging economies that wish to participate in PLA production. In many countries, SMEs face restrictive lending policies, high interest rates, or a lack of institutional knowledge about bioplastics investment risks and returns. This restricts their ability to invest in production technologies or to scale operations effectively. Even in developed economies, venture capital and green financing for bioplastic ventures remain limited compared to fossil-based plastic innovations, which benefit from deeply entrenched supply chains and higher margins [

81,

82].

The infrastructure for distribution and storage presents another layer of difficulty. Unlike traditional plastics, PLA and other bioplastics require specialized conditions for storage to prevent premature degradation, particularly in humid or high-temperature environments. However, many regions lack cold-chain logistics or humidity-controlled warehouses tailored for biodegradable materials. Furthermore, global logistics networks still prioritize conventional packaging, meaning that PLA products often suffer from higher shipping and handling costs, longer delivery times, and insufficient integration into circular waste systems [

83,

84].

Another key challenge is competition from conventional plastics, which continue to dominate due to their low cost, versatility, and well-established supply and recycling infrastructures. In many price-sensitive markets, especially in low- and middle-income countries, the price differential between PLA and fossil-derived plastics makes bioplastics a less attractive option for manufacturers and consumers alike [

60,

85]. In the absence of market-based incentives, carbon pricing, or regulatory penalties on conventional plastic use, PLA struggles to gain traction despite its environmental advantages.

The production and distribution of PLA in Vietnam face several economic challenges that hinder the growth of the bioplastics industry. These challenges include high production costs, limited access to financing, inadequate infrastructure, and competition with conventional plastics. PLA production in Vietnam is associated with elevated costs due to the reliance on imported raw materials and the lack of economies of scale [

86,

87]. The cost of producing PLA is approximately 20-50% higher than that of traditional plastics, making it less competitive in the market (

Table 4) [

88]. Additionally, the technological processes involved in PLA production are capital-intensive, requiring significant investment in equipment and facilities [

89]. This financial burden is particularly challenging for small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) attempting to enter the bioplastics market.

SMEs in Vietnam often encounter difficulties in securing financing for PLA production due to stringent lending criteria and high-interest rates. The average lending interest rate for businesses in Vietnam ranges from 7% to 9% per annum, which is relatively high compared to other Southeast Asian countries [

90]. This financial constraint limits the ability of producers to invest in necessary technologies and scale up production capacities, thereby impeding the growth of the PLA industry. The distribution of PLA products is further complicated by inadequate infrastructure, including transportation networks and storage facilities. Vietnam's logistics performance index ranks 39th out of 160 countries, indicating room for improvement in logistics efficiency [

91]. Poor infrastructure leads to increased transportation costs and delays, affecting the timely delivery of PLA products to domestic and international markets [

92,

93]. Moreover, the lack of specialized storage facilities for bioplastics, which require specific conditions to maintain quality, poses additional challenges in the supply chain [

94].

Compounding these structural issues is low consumer awareness. While some high-income markets have embraced eco-friendly products, large segments of the global population are still unaware of the benefits and limitations of PLA. This gap hinders demand generation and limits the commercial viability of bioplastics at scale. Additionally, greenwashing by producers of oxo-degradable plastics often confuses consumers, reducing trust in genuinely compostable materials like PLA.

To overcome these economic challenges, a coordinated policy approach is needed. Governments can play a critical role by offering tax incentives, green procurement mandates, feedstock subsidies, and financing support for bioplastics producers. At the same time, industry stakeholders must invest in technological innovation to reduce costs—including new catalysts, continuous processing systems, and improved fermentation strains. Establishing global standards for PLA certification, biodegradability, and product labeling will further support market clarity and consumer confidence.

In conclusion, while PLA offers promising sustainability benefits, its widespread adoption is currently constrained by systemic economic hurdles. Bridging this gap will require multi-level collaboration across public and private sectors to drive down costs, build enabling infrastructure, and foster equitable access to financing and markets.

3. Polymerization Process of D-Lactic and L-Lactic into PLA

Polylactic acid (PLA) is synthesized from lactic acid monomers, which occur as two optical isomers—L-lactic acid and D-lactic acid—distinguished by the spatial configuration of their asymmetric carbon center (

Table 5). The stereochemistry of these enantiomers plays a critical role in determining the crystallinity, thermal behavior, degradation rate, and mechanical properties of the resulting polymer. PLA derived primarily from L-lactic acid (poly-L-lactic acid, PLLA) exhibits semi-crystalline morphology, high melting temperature (170–180°C), and superior tensile strength, making it suitable for load-bearing biomedical applications such as orthopedic implants, surgical sutures, and drug delivery matrices [

95,

96,

97,

98]. In contrast, the incorporation of D-lactic acid disrupts chain packing, yielding amorphous or low-crystallinity PLA with faster processing, higher flexibility, and slower hydrolytic degradation, which is advantageous for packaging, films, and controlled-release systems [

99,

100,

101,

102,

103,

104].

Both D- and L-lactic acid are typically produced through microbial fermentation of carbohydrate-rich substrates such as glucose, sucrose, or starch. Lactobacillus delbrueckii, Lactobacillus plantarum, and other homofermentative strains are commonly employed for L-lactic acid synthesis, while Lactobacillus coryniformis and Sporolactobacillus inulinus are used to produce D-lactic acid with high optical purity [

105,

106,

107,

108]. The choice of microbial strain, pH control, fermentation temperature, and nutrient composition are key parameters in optimizing enantiomeric excess and conversion efficiency. High-purity monomers are crucial, as even small amounts of D-isomer can significantly reduce the crystallinity of PLLA [

109,

110].

The polymerization of lactic acid into PLA can be accomplished through several methods, each with distinct implications for molecular weight, architecture, and end-use properties:

Direct polycondensation is the simplest route, involving the condensation of lactic acid monomers under heat and vacuum, with water as a byproduct. However, the reversible nature of the reaction and difficulties in removing water limit the achievable molecular weight (typically <20,000 Da) [

96]. Advanced techniques such as azeotropic dehydration, use of chain extenders (e.g., diisocyanates), or solid-state polymerization have been explored to overcome this limitation [

35].

Ring-opening polymerization (ROP) of lactide—a cyclic dimer of lactic acid—is the predominant industrial method for producing high-molecular-weight PLA (up to 500,000 Da). ROP provides superior control over polymer chain length, stereochemistry, and branching, and allows tuning of thermal and mechanical properties. Catalysts such as tin(II) octoate, aluminum alkoxides, and zinc-based systems are used to initiate polymerization under relatively mild conditions [

9,

10]. Different lactide forms, including L-lactide, D-lactide, and meso-lactide, enable the synthesis of tailored PLA structures. For instance, pure L-lactide yields PLLA, while racemic mixtures result in amorphous PLA, which is advantageous for applications demanding clarity and pliability [

110,

111].

Emerging polymerization strategies aim to improve sustainability, cost-efficiency, and environmental performance. Enzymatic polymerization, using lipases or esterases, offers a low-energy and eco-friendly alternative, although its industrial adoption is currently constrained by slow kinetics and high enzyme costs [

111,

112,

113,

114,

115]. Another promising direction is direct microbial polymerization, wherein genetically engineered microbes produce PLA or PLA-like polymers intracellularly from renewable substrates, integrating fermentation and polymerization in a single step. This approach simplifies the production chain and reduces waste, though challenges persist in achieving high polymer purity and yield [

116,

117,

118,

119].

Globally, the choice of polymerization technology is often dictated by application needs, scale, regulatory compliance, and raw material availability. As the demand for biodegradable polymers grows, continuous process innovation and optimization of catalysts, reactors, and bioprocess integration will be key to reducing production costs and expanding PLA’s utility across packaging, textiles, electronics, and medical sectors.

4. Catalysts in the Polymerization of PLA: Advancements and Industrial Relevance

Polylactic acid (PLA) is primarily synthesized via ring-opening polymerization (ROP) of lactide—a cyclic dimer of lactic acid—under the action of specific catalysts that critically influence reaction efficiency, polymer molecular weight, stereochemical control, and end-use properties [

35,

103,

120]. The catalyst system selected for the ROP process is not merely a facilitator but a decisive determinant of PLA’s final characteristics, such as crystallinity, thermal behavior, mechanical strength, and biodegradability.

4.1. Metal-Based Catalysts: Current Industrial Backbone

Among catalytic systems, metal-based catalysts dominate industrial-scale PLA production due to their high catalytic activity and ability to produce high-molecular-weight polymers with controlled microstructure. The most extensively employed is tin(II) octoate (Sn(Oct)₂), a commercially approved catalyst for food-contact polymers in some jurisdictions [

121,

122,

123]. It exhibits excellent polymerization kinetics, good tolerance to impurities, and compatibility with both L-, D-, and meso-lactide monomers. However, concerns about residual tin content and potential toxicity—especially for biomedical applications—have fueled the search for safer alternatives [

124,

125].

In response, zinc-based and aluminum-based catalysts have emerged as effective substitutes. These catalysts offer reduced toxicity while maintaining acceptable activity levels and enable the synthesis of PLA with controlled tacticity and molecular weight [

96,

103,

122,

126]. Zinc lactates and alkoxides, in particular, show promise for applications where low residual metal content is required. Additionally, certain rare earth metals (e.g., yttrium, lanthanum) have demonstrated high stereoselectivity, allowing the formation of isotactic PLA—a highly crystalline form with superior thermal and mechanical properties [

126,

127].

4.2. Organocatalysts: Toward Green and Sustainable Synthesis

To address environmental and health safety concerns associated with metal residues, organocatalysts have gained increasing attention. These metal-free systems—including N-heterocyclic carbenes (NHCs), phosphazene bases, and thioureas—offer advantages in biocompatibility, environmental sustainability, and milder reaction conditions [

128,

129]. For example, phosphazene-based catalysts have demonstrated high activity and good control over molecular weight, while also avoiding metal contamination [

130,

131,

132,

133]. However, challenges remain: moisture sensitivity, relatively lower catalytic efficiency, and limited industrial scalability are significant barriers to widespread adoption [

134,

135].

Despite these limitations, organocatalysts are particularly valuable in biomedical contexts and research settings, where purity and environmental footprint take precedence over production speed.

4.3. Emerging Catalytic Approaches and Integrated Technologies

Beyond traditional catalytic systems, enzymatic polymerization represents an emerging green alternative. Enzymes such as lipases enable ROP under ambient temperatures and pressures, reducing energy consumption [

136,

137,

138,

139,

140]. However, this method suffers from slow kinetics, low molecular weight yield, and high enzyme costs, limiting its industrial potential.

Another frontier lies in direct microbial biosynthesis of PLA or PLA-like polyesters using genetically engineered microorganisms such as

Escherichia coli. These systems incorporate lactic acid polymerization machinery within fermentation pathways, eliminating the need for separate purification and polymerization steps [

141,

142,

143,

145,

146]. While still in the early stages of development, such biosynthetic platforms hold promise for integrated and low-carbon production chains.

4.4. Catalysts and Final Product Performance

The choice of catalyst directly impacts the architecture and quality of the resulting PLA polymer. For example, stereoselective catalysts can induce the formation of highly crystalline isotactic PLA, which demonstrates higher melting temperatures, mechanical strength, and slower degradation—key attributes for medical and structural applications. In contrast, non-stereoselective catalysts produce atactic or amorphous PLA, which is more flexible and suitable for applications like packaging and single-use goods [

103,

110,

143,

147,

148].

The generalized ROP reaction catalyzed by these systems can be represented as:

Table 6.

Summarizes catalyst types and their corresponding advantages and limitations.

Table 6.

Summarizes catalyst types and their corresponding advantages and limitations.

| Catalyst Type |

Examples |

Advantages |

Limitations |

| Metal-based catalysts |

Tin(II) octoate, zinc lactate, aluminum isopropoxide |

- High catalytic efficiency- High molecular weight PLA- Well-established industrial use |

- Potential metal residue toxicity- Environmental and health concerns |

| Rare earth metal catalysts |

Yttrium, lanthanum complexes |

- High stereoselectivity- Improved crystallinity and thermal properties |

- High cost- Limited commercial availability |

| Zinc and aluminum-based |

Zinc acetate, aluminum alkoxides |

- Lower toxicity than tin- Effective for controlled polymerization |

- Less catalytic activity than tin-based systems |

| Organocatalysts |

N-heterocyclic carbenes (NHCs), phosphazene bases, thioureas |

- Metal-free (biocompatible)- Environmentally friendly- Selective control |

- Moisture sensitivity- Lower reaction rates- Scalability challenges |

| Enzymatic catalysts |

Lipase (e.g., Candida antarctica) |

- Mild conditions- Green chemistry approach |

- Slow polymerization- Low molecular weight products- High enzyme cost |

| Microbial biosynthesis (genetic engineering) |

Engineered E. coli, Corynebacterium glutamicum

|

- Direct PLA synthesis from biomass- Reduced processing steps |

- Limited to lab/pilot scale- Complex process control |

4.5. Industrial Integration and Application Advancements

Recent technological innovations have significantly improved the scalability and consistency of PLA production. For instance, Sulzer Chemtech has developed modular systems for lactic acid purification, lactide synthesis, and polymerization, enabling seamless integration of the entire PLA production chain [

149]. Companies like TotalEnergies Corbion and NatureWorks have leveraged these technologies to reach industrial capacities exceeding 75,000 tons per year, producing tailored PLA grades for packaging, consumer goods, and 3D printing [

150,

151].

PLA's popularity in additive manufacturing continues to grow, thanks to its low melting point, minimal warping, and biocompatibility. Simultaneously, nanocomposite enhancements—such as graphene, hydroxyapatite, and carbon nanotube reinforcements—are expanding PLA’s potential in high-performance applications like tissue engineering and smart materials [

98,

151,

152,

153].

The biomedical sector has seen significant progress in PLA-based materials, including nanocomposites enhanced with nanofillers such as graphene, hydroxyapatite, or carbon nanotubes [

154]. These nanocomposites exhibit improved mechanical strength, biocompatibility, and functionality, making them ideal for advanced drug delivery systems, tissue engineering scaffolds, and implantable medical devices [

155]. Simultaneously, advancements in industrial-scale PLA production have been realized, with companies such as TotalEnergies Corbion achieving an annual production capacity of 75 kilotons of high-performance PLA resins [

156]. These resins are optimized for applications in sustainable packaging, a sector that continues to drive demand for environmentally friendly alternatives to petroleum-based plastics.

Despite these advancements, challenges persist in optimizing PLA's thermal and mechanical properties to compete with conventional plastics such as polyethylene and polypropylene. Research efforts are focused on modifying PLA's molecular structure, incorporating copolymers, and developing PLA blends or composites to enhance its flexibility, durability, and thermal resistance. Additionally, ongoing innovations aim to reduce production costs through more efficient fermentation techniques and the utilization of alternative, cost-effective feedstocks such as agricultural waste or non-food biomass. These efforts are essential for scaling up PLA production sustainably and maintaining its competitive edge in the global market for biodegradable polymers.

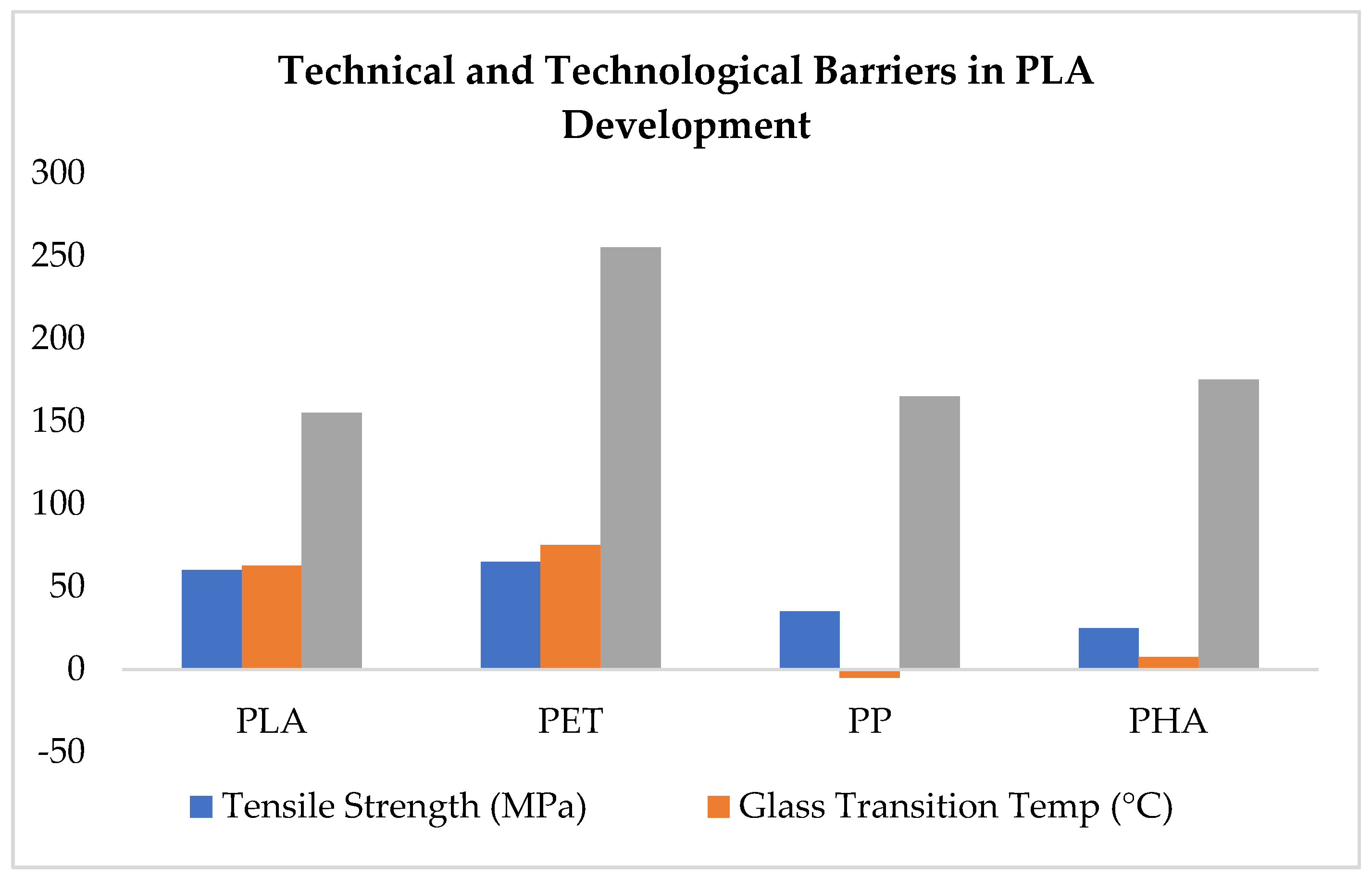

5. Technical and Technological Barriers in PLA Development

Polylactic acid (PLA) is a promising biodegradable polymer, yet its broader industrial adoption remains constrained by several technical and technological limitations [

157]. A primary concern is its mechanical brittleness, with an elongation at break of less than 10%, significantly lower than that of polyethylene terephthalate (PET) (50–150%) and polypropylene (PP) (200–700%) [

158,

159,

160]. Although PLA exhibits moderate tensile strength (50–70 MPa), its limited flexibility and poor impact resistance restrict its use in high-performance applications such as automotive components and structural parts [

161].

To overcome this, various blending and copolymerization strategies have been explored. Incorporating rubbery polymers such as polycaprolactone (PCL) or thermoplastic elastomers (TPE) improves toughness but often compromises thermal resistance [

162,

163]. Furthermore, PLA’s relatively low glass transition temperature (Tg ≈ 60°C) restricts its applicability in heat-resistant packaging and industrial settings [

67]. The use of nucleating agents, such as talc, has proven effective in increasing PLA’s crystallinity from 10% to over 40%, thereby enhancing thermal and mechanical performance [

164]. However, these modifications increase production complexity and associated costs [

165,

166].

Table 7.

Key Technical and Technological Barriers in PLA Development.

Table 7.

Key Technical and Technological Barriers in PLA Development.

| Barrier |

Description |

| Mechanical Limitations |

Inherent brittleness and low elongation at break, limiting impact resistance. |

| Thermal Stability |

Low glass transition temperature (~60°C) restricting use in high-temperature environments. |

| Barrier Properties |

High oxygen and moisture permeability limiting applications in food packaging. |

| Processing Challenges |

Narrow processing window and susceptibility to thermal degradation during melt processing. |

| Crystallization Rate |

Slow crystallization leading to longer production cycle times in molding processes. |

| Environmental Degradation |

Inconsistent degradation rates across natural environments, raising concerns about sustainability. |

The barrier properties of PLA pose another significant challenge, particularly in the packaging industry, where gas and moisture permeability are critical for preserving product shelf life [

165,

167]. PLA's oxygen transmission rate (OTR) is approximately 10–15 cm³·mil/m²·day, which is considerably higher than PET (1–5 cm³·mil/m²·day), making it less effective in protecting oxygen-sensitive products like food and beverages [

168]. Similarly, PLA's water vapor transmission rate (WVTR) is higher than that of conventional plastics, limiting its suitability for moisture-sensitive applications. To address these deficiencies, researchers have explored the incorporation of nanofillers such as graphene, clay nanoparticles, or cellulose nanocrystals. Studies have demonstrated that adding just 2% nanoclay can reduce PLA's oxygen permeability by up to 70%, while maintaining its biodegradability [

169,

170]. Multilayer coatings, combining PLA with high-barrier polymers like ethylene vinyl alcohol (EVOH), have also been developed to improve gas and moisture resistance [

171]. However, these solutions come with trade-offs, including increased production complexity, reduced recyclability, and higher costs, which remain significant barriers to commercialization [

172,

173,

174].

Processing challenges further complicate the scalability of PLA in industrial applications (

Figure 4). PLA’s narrow processing window, typically between 180°C and 200°C, makes it highly susceptible to thermal degradation during melt processing [

175]. Temperatures exceeding 200°C can cause hydrolysis and chain scission, resulting in a significant reduction in molecular weight and mechanical properties [

176]. This degradation is exacerbated by the presence of residual moisture, even at levels as low as 0.01%, necessitating thorough drying of PLA pellets before processing. Additionally, PLA’s slow crystallization rate leads to longer cycle times in injection molding and thermoforming processes, reducing production efficiency. To address these issues, research has focused on developing faster-crystallizing PLA grades through copolymerization with lactide isomers or the addition of crystallization promoters such as zinc stearate [

177]. For instance, the use of D-lactide in small quantities has been shown to enhance PLA crystallization rates without significantly compromising mechanical properties [

178]. Advanced processing techniques, such as reactive extrusion and solid-state polymerization, have also been employed to produce high-molecular-weight PLA with improved thermal and mechanical performance [

35,

179]. While these advancements are promising, they require significant investment in specialized equipment and expertise, posing challenges for smaller manufacturers and emerging markets [

180,

181].

While PLA is marketed as a biodegradable alternative to conventional plastics, its environmental performance is heavily influenced by external conditions. Under industrial composting conditions, where temperatures exceed 58°C and humidity is tightly controlled, PLA can degrade into water and carbon dioxide within 90–180 days [

89,

99,

100,

182]. However, in natural environments such as soil, freshwater, or marine settings, the degradation process is significantly slower. Studies have shown that PLA can persist in marine environments for up to 5 years, raising concerns about its contribution to microplastic pollution [

183,

184]. This discrepancy undermines the perception of PLA as an environmentally friendly material, highlighting the need for effective waste management systems to ensure that PLA products are directed to appropriate industrial composting facilities. Furthermore, the variability in degradation rates presents challenges for applications in agricultural films or marine-grade packaging, where predictable biodegradability is essential [

185]. To address this, researchers are exploring the incorporation of pro-degradant additives, such as metal oxides or enzymes, to accelerate PLA degradation in non-industrial environments [

186,

187]. While these approaches show potential, their scalability and long-term environmental impact remain areas of active investigation.

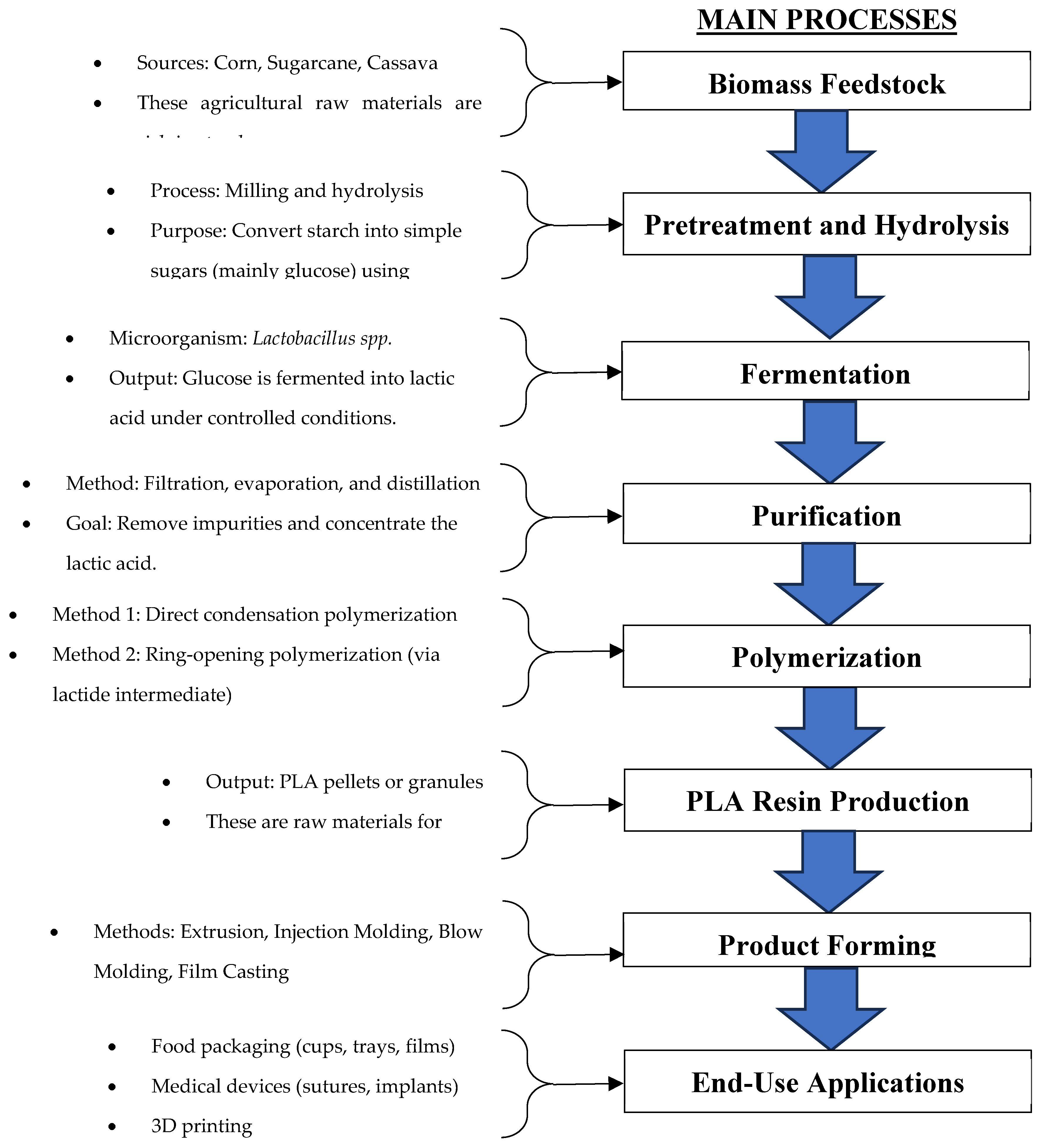

Figure 2.

Standard PLA production process.

Figure 2.

Standard PLA production process.

The production of polylactic acid (PLA) begins with the collection of renewable biomass feedstocks such as corn, sugarcane, or cassava—agricultural crops rich in starch or sugar. These raw materials undergo pretreatment and hydrolysis, where the starches are broken down into fermentable sugars like glucose using enzymatic or acid-based processes. The resulting glucose solution is then subjected to microbial fermentation, typically using Lactobacillus species, to produce lactic acid. After fermentation, the lactic acid is purified through filtration, evaporation, and distillation to achieve high purity, which is essential for polymerization. The purified lactic acid is then polymerized either by direct condensation or, more commonly, via ring-opening polymerization of lactide, a cyclic dimer of lactic acid, to form high-molecular-weight PLA. The resulting PLA polymer is cooled and processed into resin pellets or granules, which serve as raw materials for product fabrication. These resins can be formed into various shapes using conventional plastic manufacturing techniques such as extrusion, injection molding, blow molding, or film casting. Finally, PLA is utilized in a wide range of applications, including food packaging, 3D printing, biomedical devices, and agricultural films. Due to its compostability and lower carbon footprint, PLA offers a promising alternative to petroleum-based plastics, supporting global efforts toward a more sustainable materials economy.

6. Innovations in PLA Production Technology and Applications

6.1. Improving PLA Properties through Additives and Blending

Recent advancements in PLA research have concentrated on overcoming its inherent limitations—such as brittleness, low thermal stability, and poor barrier performance—through the use of polymer blending, incorporation of bio-based fillers, and functional additives. Blending PLA with other biodegradable polymers, such as poly(3-hydroxybutyrate) (PHB) or natural rubber, has been demonstrated to enhance flexibility, impact resistance, and thermal properties while maintaining overall biodegradability [

188].

The incorporation of modified biomass-derived fillers, including cellulose nanocrystals, lignin, and starch derivatives, further improves PLA’s mechanical strength, thermal resistance, and barrier properties. These biofillers not only reinforce the PLA matrix but also contribute to sustainability by utilizing renewable resources [

188].

Additionally, the use of organoclays and chain extenders has shown to be particularly effective in simultaneously enhancing multiple performance aspects. Organoclays increase gas barrier resistance and thermal stability through improved interfacial interactions, while chain extenders mitigate thermal degradation by rebuilding molecular weight during melt processing, thereby improving impact toughness and elongation at break [

189].

An emerging and promising technique is in situ microfibrillar blending, particularly with engineering polymers such as polyamide-6 (PA6). This approach leads to the formation of highly oriented fibrillar structures within the PLA matrix, which significantly enhances crystallization kinetics, mechanical performance, and foaming capability—important parameters for packaging and lightweight structural applications [

190].

Collectively, these material engineering strategies address PLA’s key deficiencies without compromising its biocompatibility, biodegradability, and processability, expanding its utility in advanced applications such as additive manufacturing (3D printing), biomedical scaffolds, and sustainable packaging systems [

191,

192].

6.2. Development of PLA Films with Natural Antibacterial and Antifungal Properties

Recent advancements in poly(lactic acid) (PLA) research have emphasized the development of active packaging materials by incorporating natural antibacterial and antifungal agents into PLA films, particularly for food preservation applications. Bioactive compounds such as essential oils (e.g., thymol, carvacrol), spruce resin, and chitosan have been successfully integrated into PLA matrices to inhibit the growth of common foodborne pathogens, including

Escherichia coli,

Listeria monocytogenes, and

Aspergillus niger [

193,

194].

In addition to providing antimicrobial functionality, these bio-based additives modulate key physicochemical properties of the films, such as tensile strength, oxygen and water vapor permeability, and thermal stability [

195]. For instance, the addition of chitosan enhances film flexibility and antimicrobial action, while certain essential oils can improve or impair mechanical integrity depending on their concentration and dispersion within the PLA matrix.

Various processing methods—such as solution casting, melt extrusion, and compression molding—have been employed to fabricate these active films, each presenting unique advantages in terms of additive dispersion and retention of bioactivity [

196,

197]. However, challenges remain in achieving uniform distribution and long-term stability of natural antimicrobials due to their volatility, hydrophobicity, and potential incompatibility with the PLA matrix [

198]. These issues necessitate modification strategies, such as microencapsulation, emulsification, or the use of compatibilizers, to enhance additive stability and interfacial adhesion.

Despite these challenges, ongoing research continues to demonstrate the viability and sustainability of using natural antimicrobial agents in PLA-based films, offering a biodegradable, non-toxic alternative to conventional synthetic packaging. This innovation aligns with increasing consumer demand for environmentally friendly and safe food packaging solutions.

6.3. PLA in Practical Packaging Applications

Polylactic acid (PLA) has emerged as a leading biodegradable polymer in the packaging industry due to its high tensile strength, optical clarity, and biocompatibility [

199]. These properties make PLA particularly attractive for applications such as food containers, trays, and films. However, its inherent brittleness, limited elongation at break, and suboptimal gas and moisture barrier properties have posed significant limitations for broader commercial adoption, particularly in the packaging of perishable or sensitive goods [

167,

200].

To address these challenges, researchers have employed a variety of modification strategies. The incorporation of plasticizers such as polyethylene glycol (PEG), citrate esters, or oligomeric lactic acid has been shown to reduce brittleness and improve flexibility, though this often comes at the expense of mechanical strength and thermal resistance [

201]. Blending PLA with other biodegradable polymers, including poly(butylene adipate-co-terephthalate) (PBAT) or polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHAs), enhances impact resistance and toughness while maintaining biodegradability.

Chain extenders—such as epoxy-functionalized additives—are commonly used to increase molecular weight and restore mechanical properties in recycled or degraded PLA, contributing to a more circular material lifecycle. Furthermore, nanocomposite technology has significantly advanced PLA’s applicability in packaging. The incorporation of nanofillers, including clay nanoparticles, cellulose nanocrystals, and graphene oxide, has demonstrated improvements in mechanical strength, thermal stability, and gas barrier performance, with some studies reporting reductions in oxygen and water vapor permeability by over 50% [

154].

In food packaging, tailoring barrier properties remains a priority to prolong shelf life and maintain product quality [

158,

159,

202]. Multilayered PLA structures and the inclusion of active agents—such as antioxidants and antimicrobial compounds—further expand its utility in smart and functional packaging solutions.

Despite current limitations, PLA continues to gain momentum as a sustainable alternative to petrochemical-based plastics. Its applications now extend beyond packaging to include medical implants, drug delivery systems, and 3D printing [

203]. Ongoing research is focused on enhancing processability, property retention during recycling, and performance in varying environmental conditions, all of which are essential to expanding PLA’s role in next-generation, environmentally friendly packaging systems.

6.4. Alternative Biomaterials and the Future of PLA

Polylactic acid (PLA) continues to garner attention as a biodegradable, bio-based alternative to petroleum-derived plastics, with a favorable environmental profile and compatibility with existing processing technologies [

89,

204]. However, intrinsic limitations in toughness, thermal stability, and gas barrier performance constrain its deployment in demanding industrial and packaging applications [

205].

To overcome these deficiencies, innovative material design strategies have been proposed. These include the blending of PLA with modified biomass components—such as lignin, cellulose derivatives, or starch—to enhance mechanical strength and maintain compostability [

64,

206]. The formation of stereocomplex PLA, derived from enantiomeric blends of poly(L-lactide) and poly(D-lactide), has shown considerable promise in elevating melting temperatures and crystallinity, thereby significantly improving thermal resistance and mechanical robustness.

Furthermore, the integration of natural and synthetic reinforcing fibers, including flax, kenaf, carbon fibers, or nanocellulose, has been explored to fabricate PLA-based biocomposites with superior load-bearing capabilities. These approaches not only enhance functional performance but also retain biodegradability, expanding PLA’s use in automotive components, consumer electronics, and structural packaging.

The advent of advanced fabrication techniques, such as additive manufacturing (3D printing), has also opened new horizons for PLA. PLA’s ease of processing, biodegradability, and biocompatibility make it well-suited for the production of personalized medical devices, biodegradable scaffolds, and multi-material constructs that leverage gradient properties for tailored functionality [

207,

208].

Despite these advancements, PLA faces growing competition from next-generation bio-based polymers such as polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHAs), polyethylene furanoate (PEF), and polybutylene succinate (PBS), which may offer improved thermal and mechanical profiles or enhanced environmental degradability under ambient conditions. However, PLA’s established infrastructure for production, processing, and end-of-life management remains a key advantage.

Looking ahead, the future of PLA hinges on continued material innovation, cost reduction strategies, and improved end-of-life pathways, including chemical recycling and industrial composting. As sustainability pressures intensify across industries, PLA’s potential as a scalable and versatile alternative to conventional plastics is poised to grow—particularly as part of integrated circular bioeconomy systems aimed at minimizing environmental impact while meeting performance demands across multiple sectors [

89].

7. International Strategies and Policies for Scaling Up PLA Use

7.1. PLA and the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)

Polylactic acid (PLA), a biodegradable and bio-based polymer synthesized from renewable agricultural resources, holds significant potential to support multiple United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)—notably SDG 12 (Responsible Consumption and Production) and SDG 13 (Climate Action) [

209]. As a low-carbon alternative to conventional petroleum-based plastics, PLA offers substantial environmental advantages, including a reduction in greenhouse gas emissions by approximately 60% over its life cycle, primarily due to the biogenic origin of its carbon feedstock and the relatively energy-efficient production processes.

The incorporation of PLA into sectors such as packaging, textiles, and consumer goods provides a tangible pathway for advancing climate mitigation goals under SDG 13, while also supporting circular economy practices under SDG 12. In Vietnam, where plastic consumption is rapidly increasing and plastic pollution ranks among the most pressing environmental challenges, the adoption of PLA can play a pivotal role. Vietnam is currently among the top five contributors to marine plastic pollution, with 0.28 to 0.73 million metric tons of plastic waste estimated to leak into the ocean each year. A shift from conventional polymers to PLA-based materials could significantly reduce this burden, particularly in the single-use packaging sector, which constitutes a major portion of plastic leakage.

Furthermore, the localization of PLA production using domestically available biomass sources, such as cassava starch, sugarcane bagasse, or corn, aligns with SDG 8 (Decent Work and Economic Growth) and SDG 9 (Industry, Innovation, and Infrastructure). It offers opportunities to stimulate rural agricultural economies, create new value chains, and attract green investment into bio-refinery and biopolymer manufacturing sectors. This, in turn, can enhance Vietnam’s economic resilience while fostering sustainable industrial development.

Despite its promise, the widespread adoption of PLA in Vietnam faces multiple barriers, including:

High production and retail costs relative to conventional plastics,

Low consumer awareness and acceptance of biodegradable alternatives,

Limited industrial composting facilities and infrastructure for bioplastic waste treatment,

Policy and regulatory gaps in bioplastics standards and labeling [

104].

To address these challenges, a comprehensive policy framework is essential. Recommended strategies include:

Subsidies or tax incentives for PLA producers and importers to improve market competitiveness,

Public procurement policies favoring biodegradable materials in government operations,

Educational campaigns to raise consumer awareness on the environmental and health benefits of bioplastics,

Investment in waste management infrastructure, particularly industrial composting and anaerobic digestion facilities,

Clear labeling standards and certification schemes to differentiate biodegradable PLA products from conventional or oxo-degradable plastics.

In the context of Vietnam, the integration of PLA into the manufacturing and packaging sectors presents an opportunity to address the country's escalating plastic waste problem. Vietnam ranks among the top five countries contributing to marine plastic pollution, with an estimated 0.28 to 0.73 million metric tons of plastic waste entering the ocean annually. By substituting conventional plastics with PLA, Vietnam can enhance its waste management practices and promote sustainable consumption patterns, in line with SDG 12 [

9]. Moreover, the utilization of locally sourced biomass for PLA production can stimulate the agricultural sector, providing economic benefits and fostering sustainable development.

Vietnam has taken initial steps toward sustainable materials adoption, including plastic bag levies and national action plans on marine plastic litter [

210,

211]. These efforts can be further strengthened through multi-stakeholder collaboration, engaging government agencies, academic institutions, private enterprises, and civil society to advance research, development, and commercialization of PLA and other biopolymers.

By leveraging its abundant biomass resources, growing scientific capacity, and rising public concern over environmental degradation, Vietnam is well-positioned to integrate PLA into a broader green transformation strategy—contributing meaningfully to its national sustainable development agenda and the global pursuit of the SDGs.

7.2. Government Policies and Support for PLA Bioplastics

Governments around the world are increasingly adopting policies to promote the development and use of polylactic acid (PLA) and other bioplastics as part of their strategies for environmental protection, waste reduction, and sustainable development. Regulatory frameworks targeting single-use plastics, incentives for bio-based materials, and support for research and innovation are among the key mechanisms used to facilitate this transition.

In the European Union, the European Green Deal and the Circular Economy Action Plan have set ambitious targets to reduce plastic waste and promote biodegradable alternatives. The EU Single-Use Plastics Directive, implemented in 2021, bans a range of disposable plastic items and encourages the development of bioplastics, including PLA, as alternatives. National strategies, such as France’s Roadmap for a Circular Economy, include targets for bioplastics adoption, research funding, and labeling schemes for compostable materials [

212].

Table 8.

Key Government Policies Supporting PLA Bioplastics Worldwide.

Table 8.

Key Government Policies Supporting PLA Bioplastics Worldwide.

| Policy/Initiative |

Description |

| EU Single-Use Plastics Directive (2021) |

Bans a range of single-use plastic items and promotes the development of biodegradable alternatives like PLA within the EU market. |

| USDA BioPreferred Program (USA) |

Certifies and promotes biobased products, including PLA, by encouraging federal procurement and raising consumer awareness. |

| Japan Biomass Utilization Promotion Plan |

Provides subsidies and strategic support for the development and commercialization of bioplastics, including those made from agricultural residues. |

| France Circular Economy Law (2020) |

Requires all plastic packaging to be recyclable, compostable, or reusable by 2025; includes labeling requirements for compostable bioplastics. |

| Canada’s Single-Use Plastics Ban (2023) |

Bans harmful plastic items and encourages innovation in sustainable alternatives, including PLA and compostable materials. |

| South Korea 2030 Resource Circulation Strategy |

Combines extended producer responsibility (EPR) with tax incentives and R&D funding to support bioplastics and circular economy goals. |

| India’s Single-Use Plastic Ban (2022) |

Nationwide prohibition of specific plastic items, with government support for alternatives including PLA derived from agricultural biomass. |

| Plastics Innovation Hub Vietnam (2022) |

A public-private partnership fostering research into PLA and other sustainable materials, supported by CSIRO and international donors. |

Similarly, countries like Japan and South Korea have established roadmaps for transitioning to a bioeconomy. Japan's “Biomass Utilization Promotion Plan” offers subsidies for manufacturers adopting bioplastics and supports public awareness campaigns to encourage environmentally responsible consumer behavior [

213]. South Korea’s “2030 Resource Circulation Strategy” includes bans on non-recyclable plastics and tax incentives for sustainable packaging solutions [

214].

In North America, the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) supports PLA development through its BioPreferred Program, which certifies and promotes biobased products [

28]. At the state level, California and New York have introduced legislative bans on single-use plastics, indirectly driving demand for alternatives such as PLA. Canada has announced a nationwide ban on harmful single-use plastics and is investing in composting and recycling infrastructure to manage bioplastic waste streams effectively.

Emerging economies are also taking action. Vietnam, for example, passed a new Law on Environmental Protection (2020) that includes future bans on non-biodegradable plastics and encourages domestic PLA production [

14]. The Plastics Innovation Hub Vietnam, established in collaboration with the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO), exemplifies growing public-private partnerships to scale up sustainable materials. Meanwhile, India has implemented national bans on single-use plastics and is investing in research initiatives focused on biopolymers derived from agricultural waste.

Specifically, from January 1, 2026, the manufacture and import of non-biodegradable plastic bags smaller than 50 cm x 50 cm and thinner than 50 μm will be prohibited, except for export purposes or packaging of other goods [

215]. Furthermore, by December 31, 2030, the production and import of single-use plastic products, non-biodegradable plastic packaging, and products containing microplastics will be banned, with certain exceptions. To support these initiatives, the government has collaborated with international organizations to tackle ocean plastic pollution. In 2020, Vietnam joined the Global Plastic Action Partnership, aiming to reduce plastic waste through public-private partnerships and policy interventions. Additionally, the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) has assisted Vietnam in designing and implementing integrated waste and plastic management programs, focusing on behavior change, waste segregation, and recycling.

Table 9.

Key Government Policies Supporting PLA Bioplastics in Vietnam.

Table 9.

Key Government Policies Supporting PLA Bioplastics in Vietnam.

| Policy/Initiative |

Description |

| Law on Environmental Protection (2020) |

Introduced regulations to control production and import of single-use plastics and non-biodegradable packaging. |

| Global Plastic Action Partnership (2020) |

Collaboration to reduce plastic waste through public-private partnerships and policy interventions. |

| Plastics Innovation Hub Vietnam (2022) |

Initiative to foster research and development in sustainable plastic alternatives, including PLA. |

| Proposed Consumption Tax on Plastic Bags |

Measure to discourage use of plastic bags and promote environmentally friendly alternatives. |

| Incentives for Eco-Friendly Product Manufacturers |

Policies to encourage businesses to produce and utilize bioplastics and other sustainable materials. |

Despite these initiatives, several challenges persist globally. The high production costs of PLA, limited consumer awareness, and gaps in industrial composting infrastructure remain significant barriers to widespread adoption [

216]. Furthermore, harmonized standards and certifications for compostability and biodegradability are still lacking across regions, hindering international trade and consumer confidence.

To overcome these obstacles, many governments are pursuing a combination of economic incentives, extended producer responsibility (EPR) schemes, public procurement policies favoring bioplastics, and investments in waste management infrastructure. International collaboration—such as through the Global Plastic Action Partnership, the UN Environment Programme (UNEP), and the OECD Working Party on Resource Productivity and Waste—is essential for aligning policies, sharing best practices, and accelerating the global transition toward sustainable materials like PLA.

Continued collaboration between government agencies, private enterprises, and international partners is essential to overcome these barriers and promote the sustainable development of the bioplastics industry in Vietnam.

7.3. Growth Potential of the Global PLA Sector in Sustainability Strategies

The global shift towards sustainable development and circular economy practices has positioned polylactic acid (PLA) as a key material in the transition to bio-based and biodegradable alternatives. Derived from renewable resources such as corn, sugarcane, and cassava, PLA aligns with global efforts to reduce plastic pollution, curb greenhouse gas emissions, and promote resource efficiency. Across various regions, supportive regulatory frameworks, increasing consumer demand for sustainable products, and growing investment in bioplastics are accelerating the adoption of PLA in packaging, agriculture, textiles, medical devices, and additive manufacturing.

Table 10.

Key Factors Influencing the Growth Potential of the Global PLA Sector.

Table 10.

Key Factors Influencing the Growth Potential of the Global PLA Sector.

| Factor |

Description |

| Government Policies |

Regulatory restrictions on conventional plastics and mandates for bio-based alternatives. |

| Feedstock Availability |

Abundance of renewable agricultural sources such as corn, sugarcane, cassava. |

| Production Costs |

Cost competitiveness with traditional plastics and scaling efficiencies. |

| Consumer Awareness |

Public understanding and acceptance of compostable and biodegradable products. |

| Waste Management Systems |

Infrastructure for industrial composting and effective end-of-life disposal. |

| Technological Innovations |

Advances in PLA synthesis, processing, blending, and material enhancement. |

| Market Demand |

Rising global demand for sustainable packaging and materials. |

| Investment and Incentives |

Financial support for bioplastics production and market development. |

| Environmental Impact |

Contribution to reducing fossil fuel use, carbon emissions, and plastic waste. |

Governments around the world have introduced policies restricting single-use and non-biodegradable plastics, creating favorable conditions for PLA expansion. For example, the European Union’s directive on single-use plastics, Canada’s national ban on plastic straws and bags, and India’s phase-out of select plastic items signal a rising commitment to alternative materials. These policies, coupled with tax incentives, green procurement standards, and public awareness campaigns, have catalyzed industry-wide shifts toward biodegradable options like PLA.

Feedstock availability also supports PLA expansion. Agricultural regions in Asia, South America, and parts of Africa provide plentiful biomass sources for lactic acid fermentation. Investments in second-generation feedstocks and waste-to-PLA technologies further promise to enhance sustainability while reducing competition with food crops.

Despite its potential, the PLA industry faces challenges, including high production costs, variability in composting infrastructure, and limitations in mechanical performance compared to petroleum-based plastics. Addressing these issues requires continued innovation in production technologies, public-private partnerships, and harmonization of international standards for biodegradability and certification.

Vietnam's commitment to sustainable development presents significant growth opportunities for the polylactic acid (PLA) sector (

Table 11). As a biodegradable polymer derived from renewable resources, PLA aligns with the nation's environmental objectives and offers a viable alternative to conventional plastics. The Vietnamese government has implemented several policies to promote the adoption of bioplastics, including PLA. The Law on Environmental Protection, enacted in 2020, introduced regulations to control the production and import of single-use plastic products and non-biodegradable plastic packaging. Specifically, from January 1, 2026, the manufacture and import of non-biodegradable plastic bags smaller than 50 cm x 50 cm and thinner than 50 μm will be prohibited, except for export purposes or packaging of other goods. Furthermore, by December 31, 2030, the production and import of single-use plastic products, non-biodegradable plastic packaging, and products containing microplastics will be banned, with certain exceptions. These regulatory measures create a favorable environment for the growth of the PLA industry.

In addition to regulatory support, Vietnam's abundant agricultural resources provide a substantial feedstock for PLA production. The country is a leading producer of cassava and sugarcane, both of which can be utilized in the fermentation processes to produce lactic acid, the monomer for PLA synthesis. Leveraging these resources can reduce reliance on imported raw materials and enhance the competitiveness of domestically produced PLA.

Despite these opportunities, challenges remain in scaling up PLA production. High production costs, limited consumer awareness, and inadequate waste management infrastructure hinder the transition from conventional plastics to bioplastics. To address these issues, the government has proposed measures such as consumption taxes on plastic bags and incentives for businesses producing environmentally friendly products. Continued collaboration between government agencies, private enterprises, and international partners is essential to overcome these barriers and promote the sustainable development of the bioplastics industry in Vietnam.

8. Standards and Certification Frameworks: A Critical Pillar for PLA Adoption

Despite the increasing interest in polylactic acid (PLA) as a sustainable substitute for petroleum-based plastics, the absence of harmonized global standards and certification frameworks remains a major bottleneck—particularly in developing countries, where infrastructure, regulatory capacity, and consumer awareness are still evolving. Standards serve as a cornerstone for ensuring product safety, environmental integrity, and market credibility, and are indispensable for enabling the scaling and integration of PLA into national material economies.

Several internationally recognized standards have been established to assess the compostability and biodegradability of PLA. These include ASTM D6400 and ISO 17088, which define criteria for industrial composting, and EN 13432, which is widely applied in the European Union. Certification schemes such as TÜV Austria’s OK Compost, DIN CERTCO, and the USDA BioPreferred® Program offer third-party verification for compostability and bio-based content. These frameworks provide important tools for validating environmental claims and facilitating global trade in PLA-based products.

However, these standards are often designed with developed countries in mind, where industrial composting infrastructure is accessible, regulatory enforcement is strong, and public understanding of eco-labels is relatively high. In developing countries, the situation is different: composting systems are limited, landfill disposal dominates, and inconsistent product labeling leads to confusion among consumers and policymakers. Without clear and enforceable standards adapted to local conditions, PLA products may not degrade as intended, potentially undermining both environmental goals and public trust.

Furthermore, many developing countries lack domestic certification bodies or the technical capacity to implement foreign standards. This creates a dependency on imported certification services, which can be costly and inaccessible for local producers and startups. As a result, market access is constrained, and innovation in bioplastics may be discouraged due to regulatory uncertainty.

Establishing national and regional standardization systems for bioplastics—aligned with international norms but tailored to local environmental, economic, and infrastructural contexts—is therefore essential. These systems should include:

Adapted biodegradability criteria for local composting and disposal conditions (e.g., landfill, marine, soil, home composting);