1. Introduction

Every economic activity within a region contributes, to a greater or lesser extent, to its GDP or wealth. Traditionally, its contribution was analysed directly, quantified in monetary units relative to other activities in the region or as a percentage indicating the weight or relevance of a sector in a particular economy.

However, the emergence and development of a new concept, what we now understand as the circular economy (CE), has necessitated a shift in how we analyse GDP. Where previously the approach for each sector followed a linear pattern of "take, make, dispose," determining GDP contribution based on resources used in activity, there is now a need to change the paradigm. We must focus on using resources differently in production and subsequently modify the way wealth generation is measured [

1].

It is necessary to rethink sectoral activities, focusing on a system of production and consumption aligned with resource regeneration, in line with climate change-related Sustainable Development Goals [

2]. Additionally, materials and resources should be considered within cycles, aiming to maximize their value over a longer time frame than previously practised.

Undoubtedly, this paradigm shift affects not only each sector but also the entire region, as it facilitates the creation of new activities, companies, and jobs linked to these shifts [

3]. This directly increases GDP figures but, more significantly, generates indirect and induced economic effects—new businesses/jobs emerging from demand for circular economy solutions and enhanced purchasing power among residents, leading to greater consumption (induced circular income return).

Furthermore, this new approach is not solely about generating new wealth or GDP contributions in the present but ensuring that these contributions grow in the future. The adoption of circular economy activities will benefit both short- and long-term economic sustainability.

Given these factors, the traditional GDP analysis approach must evolve. It should adhere to the three principles that form the basis of the circular economy [

4]: designing systems that eliminate waste and pollution, keeping products and materials in use, and contributing to the regeneration of natural systems [

5].

By combining traditional GDP analysis with these three principles, indirect and induced GDP contributions will become more significant than before.

The concept of circular economy integrates principles found in various theoretical perspectives, such as industrial ecology [

6], cradle-to-cradle design [

7], biomimicry [

8], and the performance economy [

9]. A shared directive among these theories is the challenge of planned obsolescence and the dependence on virgin raw materials, shifting focus towards industrial symbiosis, material circularity, and energy efficiency.

The wine sector is economically and culturally significant, and structurally positioned to transition towards more sustainable production and consumption models [

10]. Both viticulture and winemaking generate substantial organic by-products, require significant water and energy consumption, and rely on materials such as glass, cork, and cardboard for commercialisation [

11]. This makes it a sector naturally inclined towards circular economy practices, contributing not only directly to GDP but also generating indirect and induced economic effects.

Among the emerging activities, one of the most prominent is sustainable wine tourism. This sector strengthens the business figures of wineries engaged in it, not only returning wealth to the wineries themselves but also spreading economic benefits across the surrounding region through wine tourists’ consumption.

Since sustainable wine tourism has become an increasingly chosen strategy by wineries to expand their revenue streams, it must be considered a crucial factor in GDP growth, serving as a fundamental indirect and induced contribution to the economy.

In this study, we analyse wine sector data from one of Spain’s leading tourist destinations: the Valencian Community. Given its substantial influx of visitors, it has a greater capacity than other Spanish regions to convert general tourists into wine tourists, thereby enhancing the sector’s direct, indirect, and induced contributions to regional GDP.

This study compares the wine sector’s contribution to Valencian GDP with that of seven other Spanish autonomous communities engaged in viticulture. Collectively, these regions represent more than 90% of the country’s total wine production. We examine key differences in aspects such as employment, trade balance contribution, business structure, and vineyard area, highlighting how these factors influence circular economy initiatives.

Through specific examples, we illustrate how circular economy activities in the wine sector significantly enhance the autonomous community’s overall GDP.

Several cooperative wineries in the Valencian Community, such as Vera de Estenas and La Viña, have developed pilot projects to convert grape pomace into compost or repurpose it for cosmetics and animal feed [

12]. These initiatives are part of broader industrial symbiosis projects in the region, exploring collaborations between wineries and energy or composting companies to reuse wine sector residues. Examples include the use of wine lees for biofertilisers or biogas production, as demonstrated by Grupo Coviñas and Bodegas Vegalfaro.

These new business activities associated with the circular economy have led to the creation of new industries, increased indirect and induced employment, and improved the annual income of local residents.

Another example of circular economy integration within wine tourism is the development of sustainable wine tourism experiences in the Hoces del Cabriel Natural Park. This initiative promotes short supply chains, local gastronomy, and bioclimatic architecture in wineries, generating a direct economic return for previously underperforming establishments in the area.

The Valencian Community has also seen a public policy push in this direction, spearheaded by IVACE (Valencian Institute for Business Competitiveness). Their support plan includes incentives to foster renewable energy usage in wineries, such as photovoltaic self-consumption systems. This programme has led to the creation of a new sector focused on installing these technologies, contributing to GDP growth through job creation and overall wealth increase.

Other public initiatives include regional programmes aimed at supporting sustainable agriculture, such as the 2023–2027 PEPAC agri-environmental aid and the Valencian Organic Production Plan. Further support has come from agro-food innovation centres, such as the Valencian Institute of Agricultural Research (IVIA) and CIAGRO-UMH.

A distinctive feature of this region compared to other wine-producing areas in Spain is its network of cooperatives and family-run wineries, facilitating collaborative economics and shared logistics.

Circular economy practices in the wine sector of the Valencian Community manifest through concrete initiatives spanning vineyard management to wine distribution and consumption. The region’s agro-climatic diversity, presence of small and medium-sized innovative wineries, and institutional support have allowed the development of circular strategies focused on resource efficiency, waste reduction, and agricultural ecosystem regeneration.

Beyond direct sector impact, circular economy principles are applied across the entire production and commercialisation chain. This includes sustainable labelling and environmental certifications—such as V-Label, organic farming stamps, and carbon footprint assessments—allowing consumers to identify wines with sustainability attributes. Additionally, wineries have adopted circular wine tourism models incorporating agroecological routes, local product tastings, and visitor waste management systems.

Educational efforts and responsible consumption campaigns, led by associations such as PROAVA and local municipal projects, reinforce consumer awareness and appreciation for sustainable wine practices.

To measure circular economy implementation, various indicators have been developed, including the Circular Economy Indicator Prototype (CEIP), the Material Circularity Indicator (MCI), and the Eurostat Circular Material Use Rate (CMUR). These frameworks quantify how materials remain in use, are recycled, or are reintegrated into the economic system [

13].

Despite these advancements, our study focuses on quantifying the wine sector’s contribution to GDP compared to other Spanish autonomous communities. This comparative approach identifies where economic impacts differ and how they affect regional wealth generation.

The circular economy not only represents a technical and productive transformation, but also a fundamental shift in the economic paradigm, with institutional, cultural, and organizational implications. Its effective implementation requires Coherent regulatory frameworks that ensure consistency across different governance levels, participatory governance mechanisms to foster collaboration among stakeholders and a cultural transition toward responsible consumption and sustainability valuation (Gil-Lamata & Latorre-Martínez, 2022; Espinoza, 2023) [

14,

15]

In this study, we propose the following hypotheses:

H1: Circular economy activities contribute more significantly to the regional GDP than in other autonomous communities.

H2: Circular economy activities generate GDP contributions indirectly and induced.

H3: Circular economy activities lead to greater professionalisation in the workforce—both direct, indirect, and induced—enhancing GDP contribution figures.

H4: The business structure (winery size) influences the implementation of circular economy activities.

2. Methodology and Analysis

To test our hypotheses, we analysed the wine sector’s GDP contributions across eight Spanish autonomous communities, which collectively account for more than 90% of the country's wine production.

The regions included in our analysis are Aragón, Catalonia, Castilla-La Mancha (CLM), Castilla y León (CyL), Extremadura, Galicia, La Rioja, and the Valencian Community. We considered each region’s GDP contributions in monetary units, the number of jobs generated (direct, indirect, and induced), the size of vineyards, and their role in international trade balance (export surplus vs. import figures).

Our model determined how these variables influence the final contribution to the GDP of each autonomous community.

The data sources used in our analysis include international and national organisations related to the wine sector, alongside government agencies from both the European Union and Spain [

16,

17]. Additional insights were gathered from reports by OIVE [

18], AFI [

19], OeMV [

20], and OIV [

21].

To establish our predictive model, we conducted variance analysis (ANOVA) to evaluate the significance of each variable in contributing to GDP. Additionally, a one-way and two-way permutational multivariate ANOVA (PERMANOVA) was performed to determine whether individual variables impacted regional GDP and how they interacted collectively.

3. Results

The following dataset was compiled using the aforementioned sources (

Table 1):

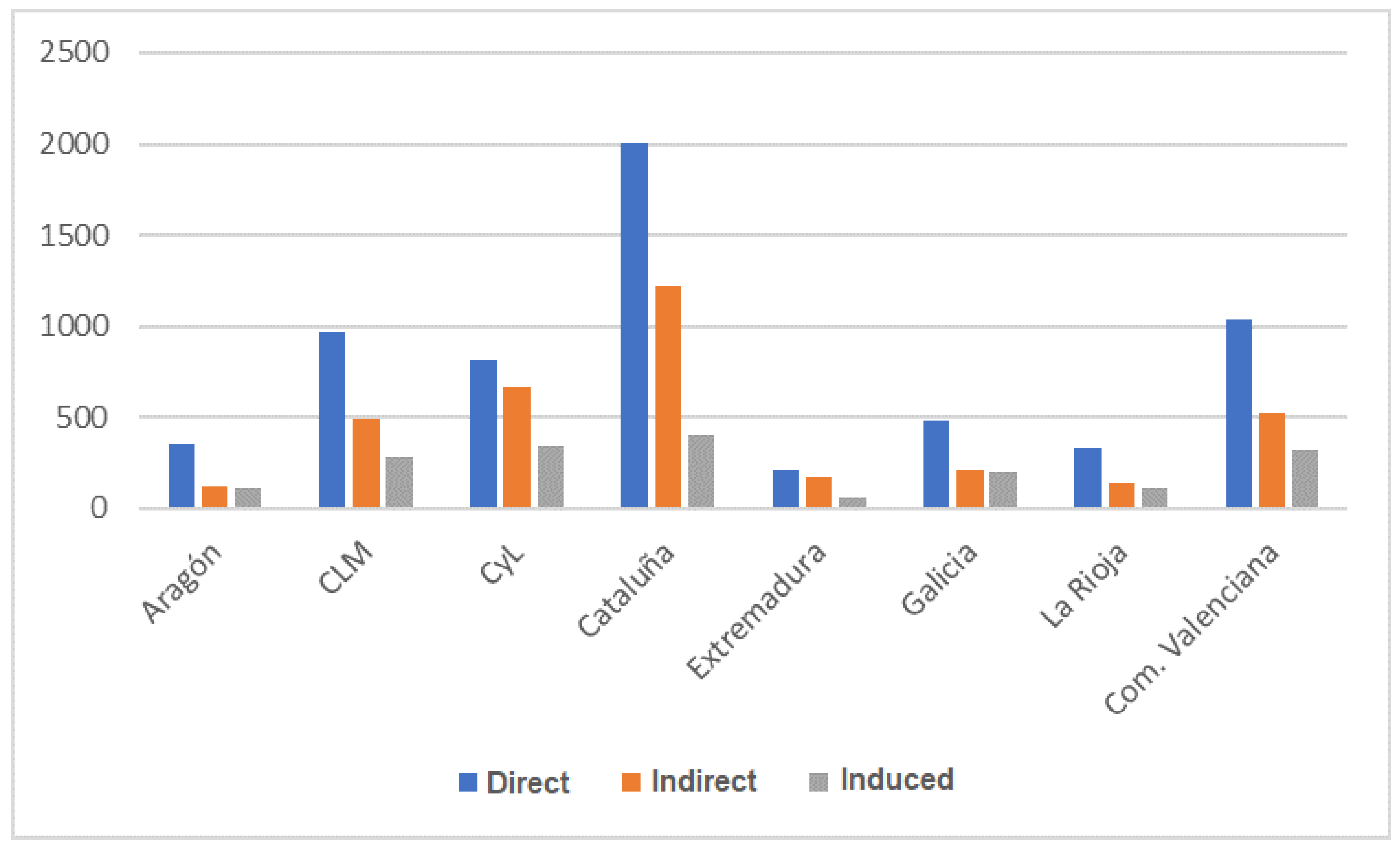

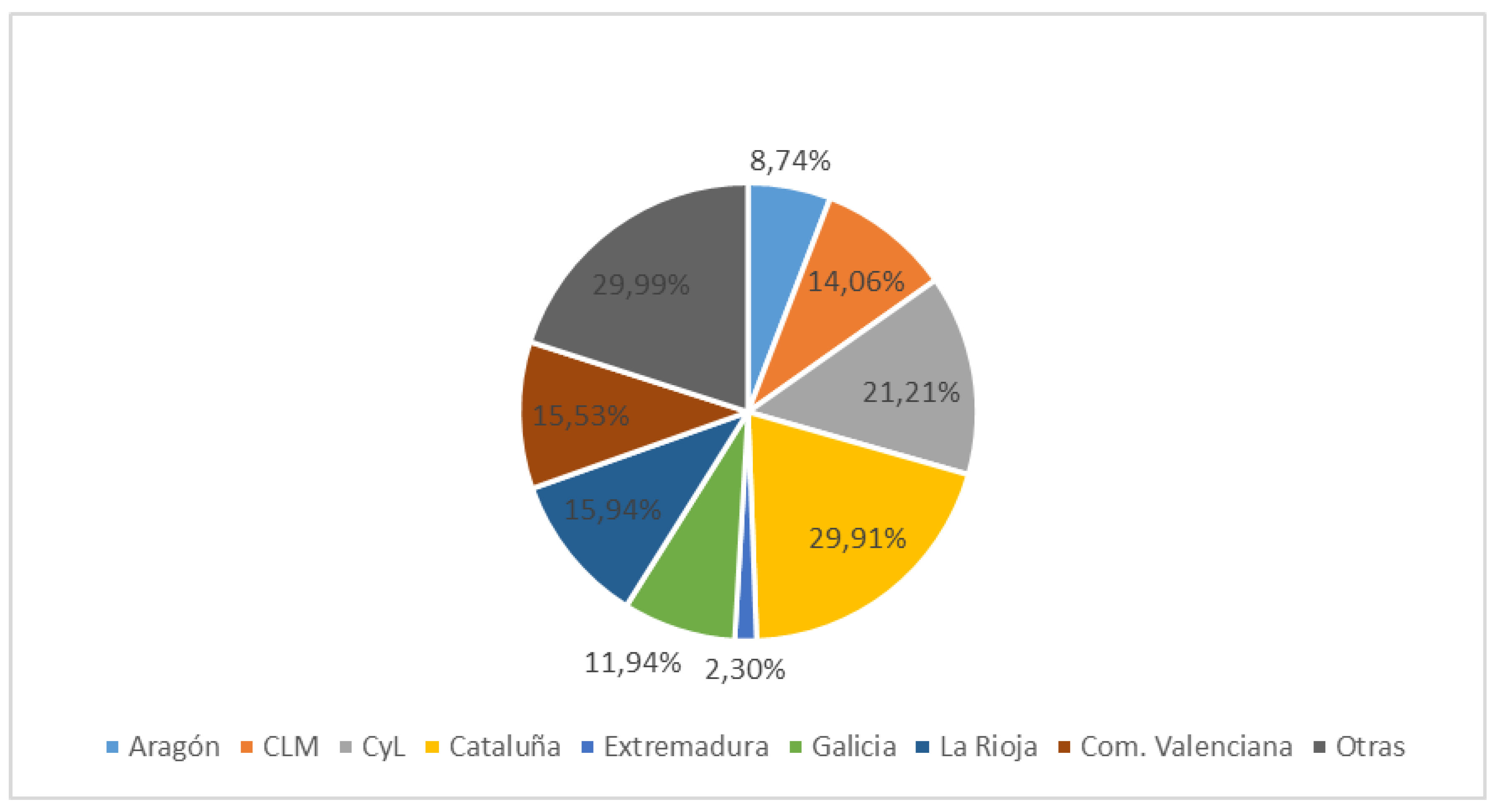

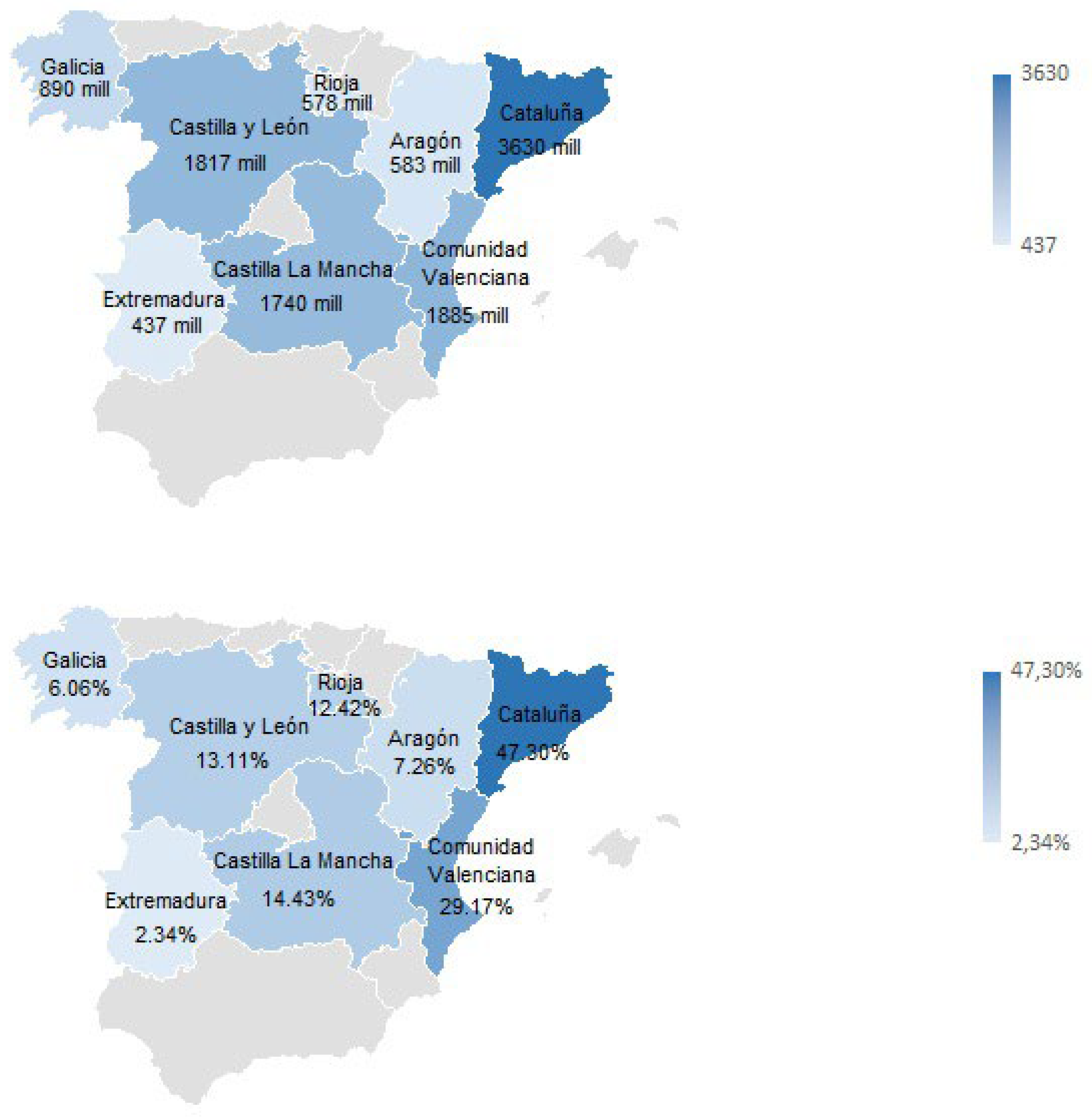

Our study identified a key characteristic and distinction in the Valencian wine sector: although its monetary contribution to the regional GDP is highly significant—ranking as the second-largest contributor among Spanish autonomous communities, with €1.885 billion (only behind Catalonia) (

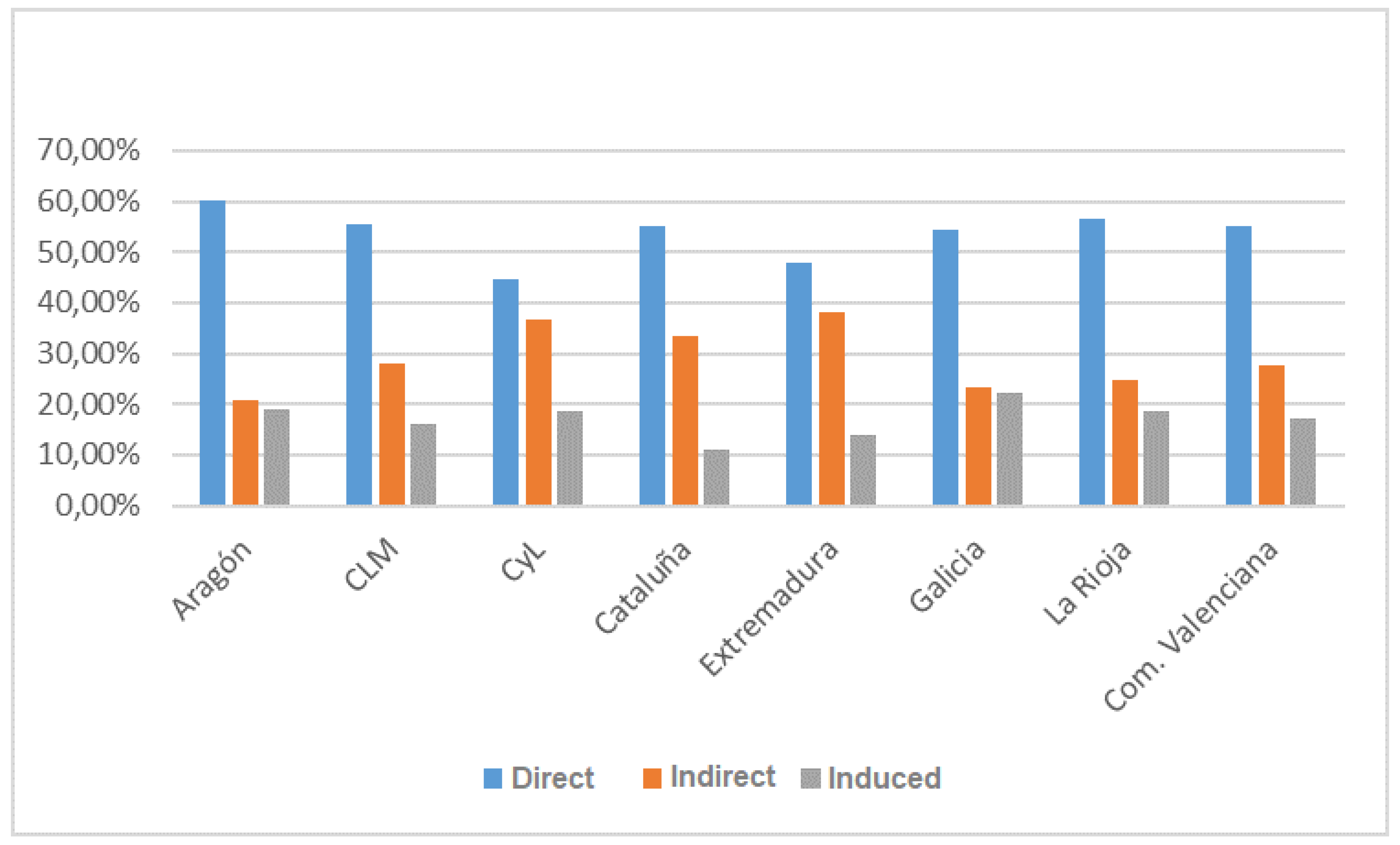

Figure 1)—its business network extends across multiple sectors. This is largely due to the extensive range of activities linked to the circular economy, which are more widespread in this region than in other areas of Spain. As a result, the wine sector's percentage share of the regional GDP is relatively lower, standing at 1.7% of the Valencian Community’s GDP compared to the national average of 1.9% (

Figure 2).

Our predictive model allowed us to obtain a regression linking the three weighted variables and analysing how they influence the final GDP contribution, based on data from the eight autonomous communities that produce the highest volume of wine at the national level.

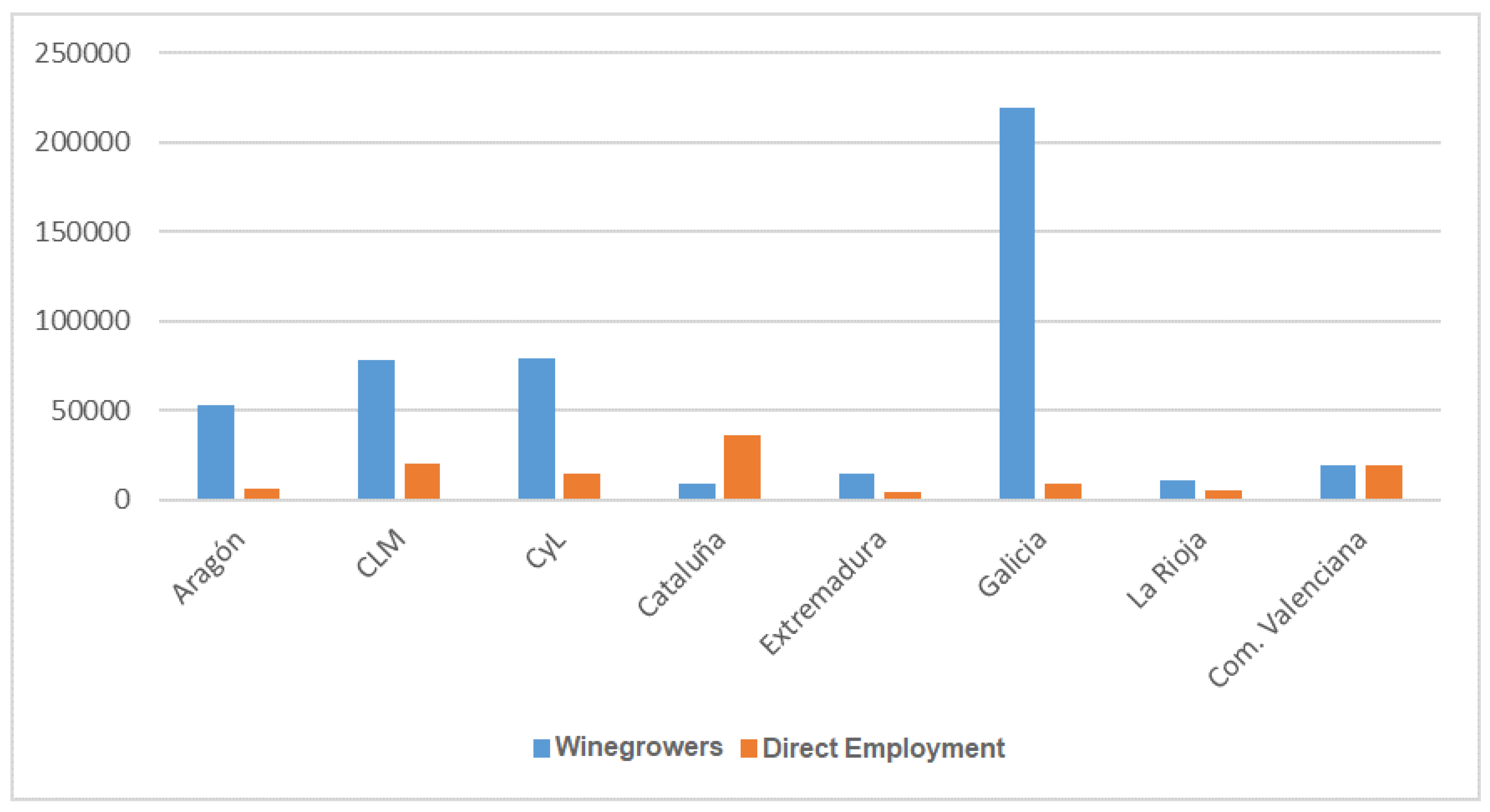

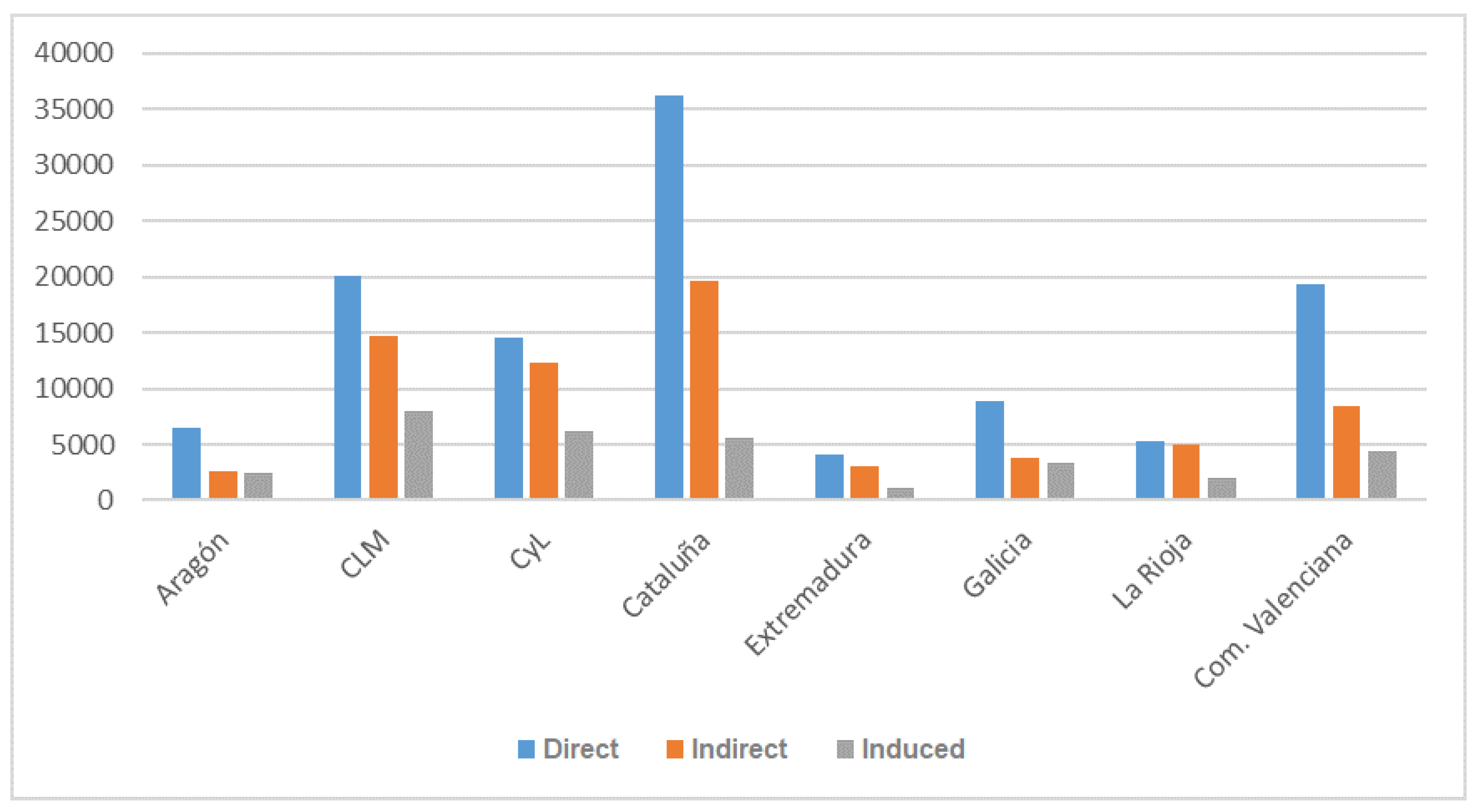

When examined individually, employment in the sector (

Figure 3;

Figure 4) and a positive external trade balance (

Figure 5) both contribute favourably to increasing the wine sector’s GDP impact on the economy. In contrast, a smaller vineyard surface area negatively affects GDP figures (

Figure 6).

If we focus more directly on the possible correlation between the implementation of circular economy activities and their contribution to the GDP that the wine sector contributes to each autonomous community, the factor that we consider relevant is the percentage of vineyard surface area that each community has with organic certification.

Comparing the 8 Autonomous Communities in terms of their contribution to GDP and the percentage of vineyards with organic certification (

Table 2), it can be clearly seen that those in which the wine sector contributes most to GDP in monetary units are those with the highest percentage of area with organic certification, as can be seen in

Figure 7.

The organic certification of vineyards means having to implement circular economy activities that end up increasing the figures that the wine sector contributes to GDP to a greater extent than those regions with less surface area with this certification.

Statistical Model

By interrelating the three variables, we obtained the following regression statistics (

Table 3 and

Table 4):

With an Adjusted R² of 0.93519252, very close to 1, and a Critical F-value (8.5341E-06) far below the alpha used in the model (0.05), alongside the t-statistic probability for all three weighted variables being below our alpha (indicating their significance), we can establish the following regression equation that supports our hypothesis:

where:

299.16 is the constant,

X1 represents Employment,

X2 represents External Trade Balance (exports minus imports).

-

X3 represents Vineyard Surface Area,

The results indicate: (Interpretation of Variables)

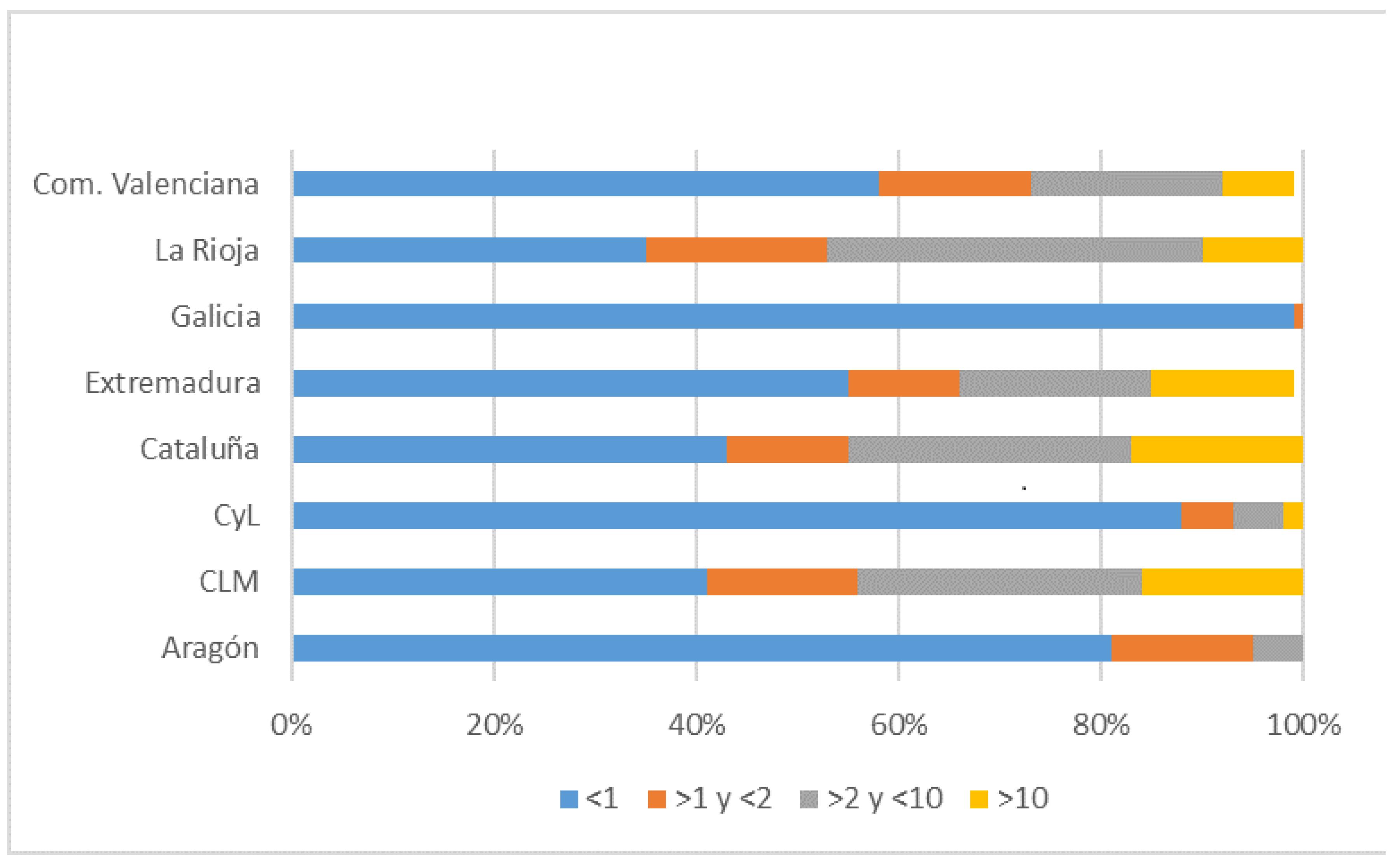

Employment: Shows a positive contribution to GDP. The relatively low coefficient reflects that in many autonomous communities, employment primarily consists of viticulturists—direct-sector workers who are not full-time, leading to lower monthly income levels and, consequently, lower returns to the local economy in a circular framework. In the Valencian Community and Catalonia, greater professionalisation (higher monthly earnings) results in a higher monetary contribution to GDP than in other communities.

External Trade Balance: Appears negative when interacting with other variables, though it is individually positive in its contribution to GDP. This occurs because indirect and induced GDP returns do not happen within the autonomous community but rather in the destination countries of exports. Thus, even if an external trade balance is positive, when interacting with employment and vineyard size, a high surplus can limit local job creation and reduce economic consumption impacts from workers linked to the sector.

Vineyard Surface Area: Shows a strong negative impact. Small vineyards contribute to smaller wineries, fewer available resources, and, consequently, lower capacity for undertaking circular economy activities. Many wineries struggle to quantify the monetary return of circular initiatives, making it difficult to justify their adoption. As a result, many decide not to implement circular economy strategies, despite their potential long-term benefits.

4. Discussion

Despite the progress made and the exemplary initiatives of certain wineries, the transition to a fully circular winemaking model in the Valencian Community—and its contribution to GDP—still faces multiple structural, economic, and cultural challenges. Addressing these challenges requires coordinated efforts from public policy, research, and the business sector.

One of the main obstacles is the absence of a specific regulatory framework that clearly governs and promotes circular economy practices in the agri-food sector, beyond the wine industry. At the European level, initiatives such as the Green Deal and the 2020 Circular Economy Action Plan [

22] seek to address this gap. In Spain, similar strategies exist, including the Spanish Circular Economy Strategy 2030, alongside plans from organisations such as the Spanish Wine Federation [

23]. At the regional level, the Valencian Circular Economy Strategy 2030 [

24] has been introduced. However, conflicting priorities and approaches between EU, national, and regional governments often slow implementation and create uncertainty regarding execution [

25,

26,

27,

28].

Our findings support the first two hypotheses:

H1: Circular economy activities contribute more significantly to the Valencian Community’s GDP than those of other autonomous communities.

H2: Circular economy activities generate indirect and induced GDP contributions.

The Valencian Community ranks second nationwide in GDP contributions from the wine sector, particularly through indirect and induced channels. This confirms that circular economy-related activities substantially enhance the wine sector’s economic impact. However, due to the diversification of business models associated with circular practices, the direct percentage share of GDP remains slightly below the national average (1.7% versus 1.9%).

Quantitatively speaking, the monetary contribution to GDP is among the highest in Spain, driven by circular economy initiatives and their associated activities.

Indirect and induced impacts stem from the expansion of small wineries requiring goods and services for circular economy initiatives. These demands lead to the creation of new enterprises that, while small in scale, collectively contribute significantly to GDP growth. This profile aligns with previous studies highlighting the role of circular economy in adapting to business structures [

29,

30].

H3: Circular economy activities contribute to greater professionalisation in the workforce, improving GDP contributions.

The professionalisation of the wine sector in the Valencian Community has helped generate Spain’s second-highest GDP contribution from wine activities. This is largely due to the implementation of circular economy practices within wineries, as well as the creation of related industries that boost indirect and induced contributions to GDP—particularly through increased consumer spending by workers in these sectors.

This aligns with previous research indicating that a clear strategy is necessary to implement a series of actions for achieving circular economy goals [

31].

Professionalising the wine sector increases the number of full-time employees compared to part-time viticulturists. This results in higher monthly earnings, allowing workers to contribute more substantially to regional GDP through increased consumption.

Professionalisation also extends beyond the wineries themselves. Small businesses providing goods and services for circular economy activities contribute significantly to local GDP growth.

As previously mentioned, sustainable wine tourism is emerging as a key activity, contributing to the creation of new, more professionalised jobs. This trend has been confirmed by various prior studies [

32,

33], which highlight how sustainable enotourism enhances employment quality and economic impact in wine-producing regions.

H4: Business structure (winery size) influences the adoption of circular economy activities.

Many small wineries lack the necessary resources to access technologies for waste treatment, circularity monitoring, or digitalisation [

34]. As noted in previous studies analysing circular economy in manufacturing industries [

35,

36,

37] the lack of economies of scale—particularly in highly fragmented wine sectors—poses challenges for circular waste management, reverse logistics, and packaging reuse. This problem is especially pronounced in rural areas with dispersed production.

Additionally, the initial investment cost for renewable energy, water recycling systems, or eco-friendly product design remains high. Many wineries perceive returns as unclear or difficult to quantify, which discourages adoption—a challenge identified in prior research [

38]. Without targeted financial instruments such as tax incentives, green loans, or circular innovation grants, wider adoption remains difficult.

Nonetheless, small wineries are increasingly incorporating circular practices where feasible, demonstrating their positive impact on GDP figures.

Winery size correlates with vineyard fragmentation. Higher fragmentation results in smaller-scale wineries with fewer resources to implement circular economy initiatives. The Valencian Community ranks fourth in Spain for vineyard fragmentation, meaning its businesses face greater challenges in implementing large-scale circular practices. However, many wineries still incorporate smaller-scale circular economy strategies, collectively contributing to the region’s GDP [

39,

40].

5. Conclusions

While the circular economy in the Valencian wine sector is viable and growing, a multi-actor, multi-dimensional strategy is required to combine technological innovation, public policy, cooperative business initiatives, and cultural shifts.

Our analysis confirms that regions with more professionalised wine sectors—such as Catalonia and the Valencian Community—achieve higher GDP contributions through direct, indirect, and induced circular economy impacts.

The paradigm shift toward a circular economy model proposed in this study for the wine sector of the Valencian Community represents both a structural necessity and a strategic opportunity. This transition could become a key factor in the region’s GDP contribution.

In today’s economic context—marked by natural resource pressures, climate change, sectoral volatility, and challenges in industries such as agriculture—the circular economy presents an integrated framework that enables a reassessment of production methods.

This approach rethinks every stage of the production chain, including wine distribution and consumption, fostering systemic efficiency, ecological regeneration, and shared value creation.

The analysis conducted indicates that while there are promising circular initiatives across various segments of the value chain, the overall adoption of circularity remains in an early and fragmented phase, constrained by regulatory, technological, cultural, and scale-based barriers.

We can conclude that, while the Valencian Community stands apart from other Spanish autonomous communities in terms of its GDP contribution, with circular economy activities playing a more significant role here than in other regions, there is potential for broader, more systematic adoption. If the region can successfully advance in the following strategic action lines, it can further enhance its contribution to GDP and strengthen its economic resilience through sustainable wine production:

Clearer regulations aligned across EU, national, and regional levels, promoting circular innovation through incentives, green certifications, and sustainable procurement policies.

Investment in shared infrastructure and technology to facilitate circular waste management, water treatment, and renewable energy integration.

Technical training and business support to help smaller wineries adopt cost-effective circular practices.

Intersectoral collaborations to strengthen synergies between agri-food, tourism, education, and research.

Consumer awareness campaigns to elevate the market value of sustainable wine, strengthening its competitive position.

Circular economy is not just a set of isolated activities; rather, it represents an agro-industrial transformation that allows Valencian viticulture to evolve toward a more resilient, inclusive, and environmentally sustainable model. The wine sector can serve as a pioneer for systemic innovation within Mediterranean rural economies.

6. Limitations and Future Research Directions

Two key limitations were identified in this study

On one hand, the companies established to provide resources for wineries to implement circular economy practices tend to be small-scale enterprises, making it highly complex to accurately quantify their contribution to the regional GDP—both in number and monetary value.

On the other hand, quantifying the monetary value of the induced impact of each circular economy-related activity is economically unviable. The cost of measuring these contributions outweighs the perceived economic benefit of doing so. As a result, many businesses engage in circular economy practices without attempting to quantify their precise GDP impact. They adopt these measures knowing that they improve overall business performance, yet they remain uncertain about the exact contribution such practices make to their financial success.

Future research could focus on identifying the full scope of circular economy activities within Valencian wineries. This could:

Pinpoint the most cost-effective circular practices that could be adopted more widely, allowing for greater economic efficiency.

Develop standardised cost-benefit ratios, enabling generalisation beyond Valencian wineries and facilitating adoption across other Spanish wine regions.

References

- Webster, K. (2021). A Circular Economy Is About the Economy. Circ.Econ.Sust. 1, 115–126 (2021). [CrossRef]

- López, R. C., & Ferrer, F. J. C. (2018). La viticultura mediterránea en España frente al cambio climático. Publicaciones Cajamar, 155. Online in: https://publicacionescajamar.es/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/el-sector-vitivinicola-frente-al.pdf#page=155.

- Friant, M.C., Vermeulen, W.J.V. & Salomone, R. (2020). A typology of circular economy discourses: Navigating the diverse visions of a contested paradigm. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 161. [CrossRef]

- Ellen MacArthur Foundation. (2013). Towards the Circular Economy: Economic and Business Rationale for an Accelerated Transition. https://ellenmacarthurfoundation.org.

- Lewandowski, M. (2016). Designing the business models for circular economy: Towards the conceptual framework. Sustainability, 8(1), 43. [CrossRef]

- Frosch, R. A., & Gallopoulos, N. E. (1989). Strategies for manufacturing. Scientific American, 261(3), 144–152.

- Braungart, M., & McDonough, W. (2002). Cradle to Cradle: Remaking the Way We Make Things. North Point Press.

- Benyus, J. M. (2002). Biomimicry: Innovation Inspired by Nature. Harper Perennial.

- Stahel, W. R. (2010). The Performance Economy. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Kirchherr, J., Reike, D., & Hekkert, M. (2017). Conceptualizing the circular economy: An analysis of 114 definitions. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 127, 221–232. [CrossRef]

- Carpio, A., Vázquez-Rowe, I., & Aldaco, R. (2023). Circular economy strategies in the wine sector: A life cycle perspective. Journal of Cleaner Production, 398, 136536. [CrossRef]

- Geissdoerfer, M., Savaget, P., Bocken, N. M., & Hultink, E. J. (2017). The Circular Economy–A new sustainability paradigm? Journal of Cleaner Production, 143, 757–768. [CrossRef]

- Moraga, G., Huysveld, S., Mathieux, F., Blengini, G. A., Alaerts, L., Van Acker, K., ... & Dewulf, J. (2019). Circular economy indicators: What do they measure? Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 146, 452–461. [CrossRef]

- Gil-Lamata, M., & Latorre-Martínez, M. P. (2022). La economía circular y la sostenibilidad: una revisión sistemática de la literatura. Cuadernos de Gestión, 22(1), 129-142. [CrossRef]

- Espinoza, H. A. (2023). Economía circular: una aproximación a su origen, evolución e importancia como modelo de desarrollo sostenible. Revista de Economía Institucional, 25(49), 109-134. DOI: . [CrossRef]

- INE – Instituto Nacional de Estadística (2025) https://www.ine.es/ Acces on may 2025.

- MAPA – Ministerio de Agricultura, Pesca y Alimentación (2025). https://www.mapa.gob.es/es/ Access on may 2025.

- OIVE – Interprofesional del Vino de España (2025). https://interprofesionaldelvino.es/ Access on may 2025.

- AFI (2025) https://www.afiglobaleducation.com/ Access on may 2025.

- OEMV (2025) https://www.oemv.es/ Access on may 2025.

- OIV International Organisation of Vine and Wine (2025). https://www.oiv.int/es Access on may 2025.

- European Commission (2020). Nuevo Plan de Acción para la Economía Circular. Por una Europa más limpia y más competitiva. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/ES/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A52020DC0098.

- Federación Española del Vino (FEV). (2021). Guía práctica para la economía circular en bodegas. https://www.fev.es.

- Generalitat Valenciana. (2022). Estrategia Valenciana de Economía Circular 2030. https://circulaval.gva.es.

- Kirchherr, J., Piscicelli, L., Bour, R., Kostense, E., Muller, J., Huibrechtse, A., & Hekkert, M. (2018). Barriers to the Circular Economy: Evidence from the European Union (EU). Ecological Economics, 150, 264-272. [CrossRef]

- European Commission. (2020). Modificar nuestras pautas de producción y consumo: El nuevo Plan de acción para la economía circular muestra el camino hacia una economía competitiva y climáticamente neutra de consumidores empoderados. [Comunicado de prensa]. Bruselas. Obtenido de https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/deta il/es/ip_20_420.

- European Commission. (2023). Joint Employment Report 2024 : Commission proposal. Publications Office Of The EU. https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/93b9c730-8da5-11ee-8aa6-01aa75ed71a1/language-en.

- Alicia Ferradás-González, Cristina Pérez-Rico, Alba Adá-Lameiras (2024). Circular Economy, Sustainability Technology and SDGs. Sustainable Technology and Entrepreneurship Volume 3, Issue 3, September–December 2024 . [CrossRef]

- Navarro, C., & García-García, D. (2021). Modelos de economía circular en el sector agroalimentario mediterráneo: experiencias y propuestas. Cuadernos de Desarrollo Rural, 18(90), 101–123. [CrossRef]

- Bag, S., Dhamija, P., Bryde, D. J., & Singh, R. K. (2022). Effect of eco-innovation on green supply chain management, Circular Economy Capability, and performance of small and Medium Enterprises. Journal of Business Research, 141, 60–72. [CrossRef]

- Bocken, N. M. P., Bakker, C., & Pauw, I. de. (2016). Product design and business model strategies for a circular economy. Journal of Industrial and Production Engineering, 33(5), 308–320. [CrossRef]

- Marco-Lajara, B., Úbeda-García, M., Zaragoza-Sáez, P., Poveda-Pareja, E., & Martínez Falcó, J. (2023). Enoturismo y sostenibilidad: Estudio de casos en la Ruta del Vino de Alicante (España). PASOS Revista De Turismo Y Patrimonio Cultural, 21(2), 307–320. [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Falcó, J., Martínez-Falcó, J., Marco-Lajara, B., & Sánchez-García, E. (2024). El enoturismo como motor de sostenibilidad e innovación: el caso de Bodegas Franco-Españolas (España). ROTUR. Revista de Ocio y Turismo, 18(2), 24–44. [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, S., Raut, R. D., Mandal, M. C., & Ray, A. (2023). Are the small- and medium-sized enterprises in developing countries ready to implement circular economy practices? an empirical quest for key readiness factors. IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management, 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Rosa, P., Sassanelli, C., & Terzi, S. (2019). Towards circular economy implementation in manufacturing systems: A systematic literature review. Journal of Cleaner Production, 236, 117696. [CrossRef]

- Al-Awlaqi, M. A., & Aamer, A. M. (2022). Individual entrepreneurial factors affecting adoption of circular business models: An empirical study on small businesses in a highly resource- constrained economy. Journal of Cleaner Production, 379, 134736. [CrossRef]

- Thopte, I., Evangelista, A., Jenner, R. & Poldner, K. (2025). Regenerative Business Practices: Supporting Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises’ Transition to a Net-Positive Circular Economy .Journal of Circular Economy, 3(1). [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, V., & Ülkü, S. (2012). Product design in a circular economy: Balancing cost with environmental impact. International Journal of Production Economics, 140(2), 451–461. [CrossRef]

- Caldera, H. T. S., Desha, C., & Dawes, L. (2019). Evaluating the enablers and barriers for successful implementation of sustainable business practice in ‘lean’ smes. Journal of Cleaner Production, 218, 575–590. [CrossRef]

- Despoudi, S., Sivarajah, U., Spanaki, K., Charles, V., & Durai, V. K. (2023). Industry 4.0 and circular economy for emerging markets: Evidence from small and medium-sized enterprises (smes) in the Indian Food Sector. Annals of Operations Research. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).