Introduction

In recent decades, the advancement of digital technologies has markedly transformed clinical dental practice, fostering approaches that are increasingly predictable, minimally invasive, and tailored to individual patient profiles. The digitalization of clinical workflows has significantly influenced all domains of dentistry, including diagnostic protocols, treatment planning, and the fabrication of prosthetic, orthodontic, and surgical devices.¹ Within this evolving paradigm, intraoral scanning,² digital mandibular motion tracking,³ and aesthetic-functional previewing have emerged as integral components in enhancing both treatment quality and patient satisfaction. Intraoral scanners (IOS) have, in many instances, supplanted traditional impression techniques, offering a series of clinical and operational advantages. These include improved patient comfort, decreased distortion associated with conventional impression materials, real-time quality control of digital acquisitions, and seamless integration with CAD/CAM systems for prosthetic design.⁴⁻⁶ Moreover, IOS technology constitutes the foundational element for the generation of a “digital twin” of the patient, facilitating advanced diagnostic simulations, analytical evaluations, and interdisciplinary planning. In addition to IOS, the integration of digital technologies for recording mandibular dynamics enables precise assessment of functional occlusion,⁷⁻⁸ mandibular movement trajectories, and the craniomandibular relationship. These data sets are particularly relevant in cases involving temporomandibular disorders, full-mouth rehabilitations, or extensive restorative interventions, where vertical dimension, centric relation, and functional mandibular pathways critically influence prosthetic planning.⁹ The dynamic registration provided by systems like Zebris supports individualized occlusal schemes that align with the patient’s natural biomechanics, thereby enhancing long-term functional outcomes and reducing the risk of complications.

A further key component of the digital workflow is aesthetic and functional previsualization. Software platforms allow clinicians to simulate final treatment outcomes by integrating facial and intraoral photographs with digital scans.¹⁰ These tools enable a comprehensive evaluation of dental and facial proportions, incisal edge position, smile line, and gingival architecture, facilitating the validation of the proposed treatment plan before initiating any irreversible procedures. The use of digital smile design enhances interdisciplinary communication, improves patient understanding and engagement, and significantly contributes to case acceptance by allowing preview and modification of the aesthetic outcome based on objective criteria.

This case report presents an integrated, fully digital approach to aesthetic and functional prosthetic rehabilitation, incorporating intraoral scanning, digital mandibular motion registration, and smile previewing technologies. The objective is to demonstrate how the synergistic application of these tools contributes to more precise treatment planning, enhanced predictability of prosthetic outcomes, and superior functional and aesthetic results. The case also emphasizes the value of digital documentation in facilitating long-term follow-up and interdisciplinary collaboration.

Case Summary

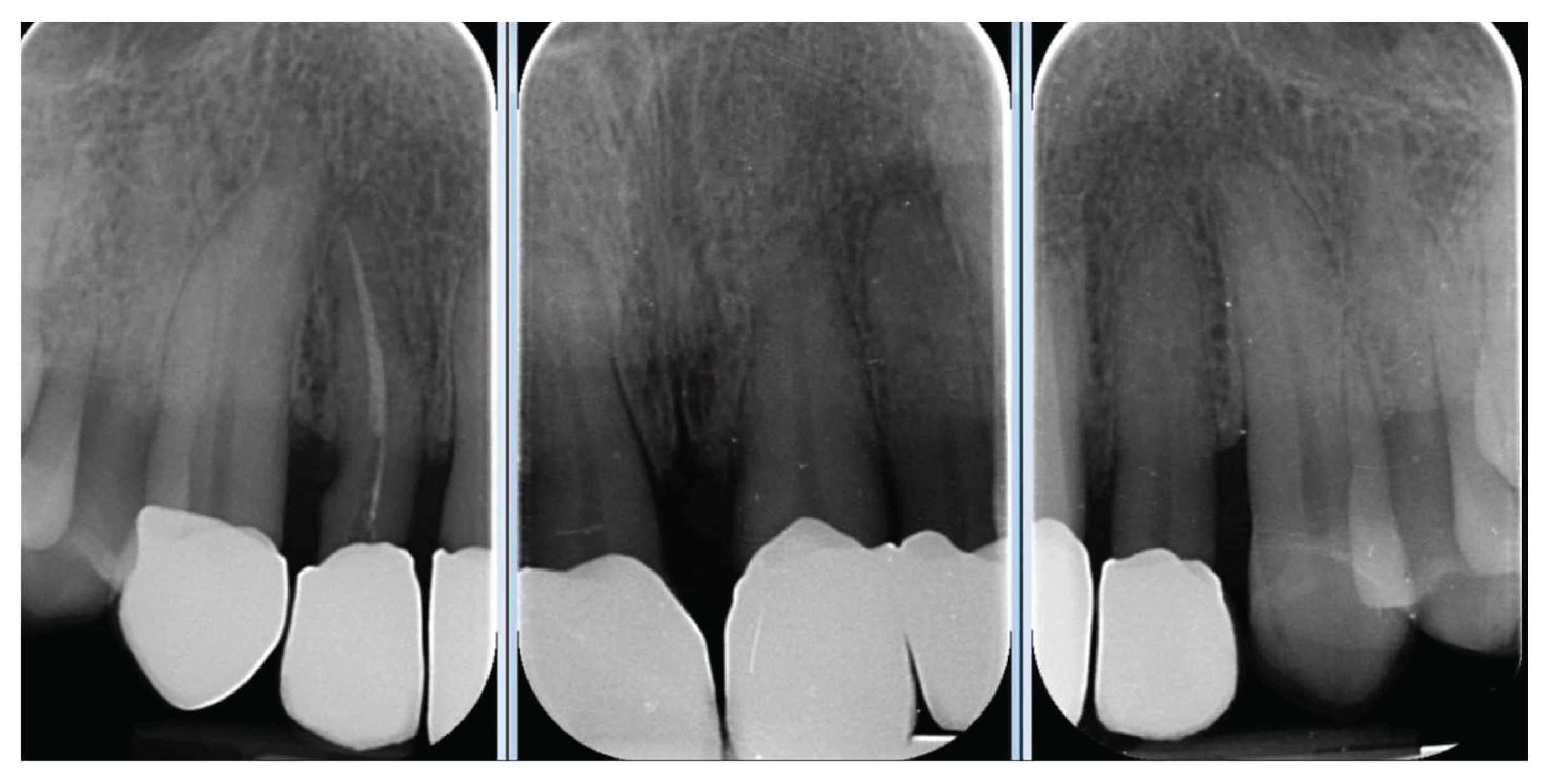

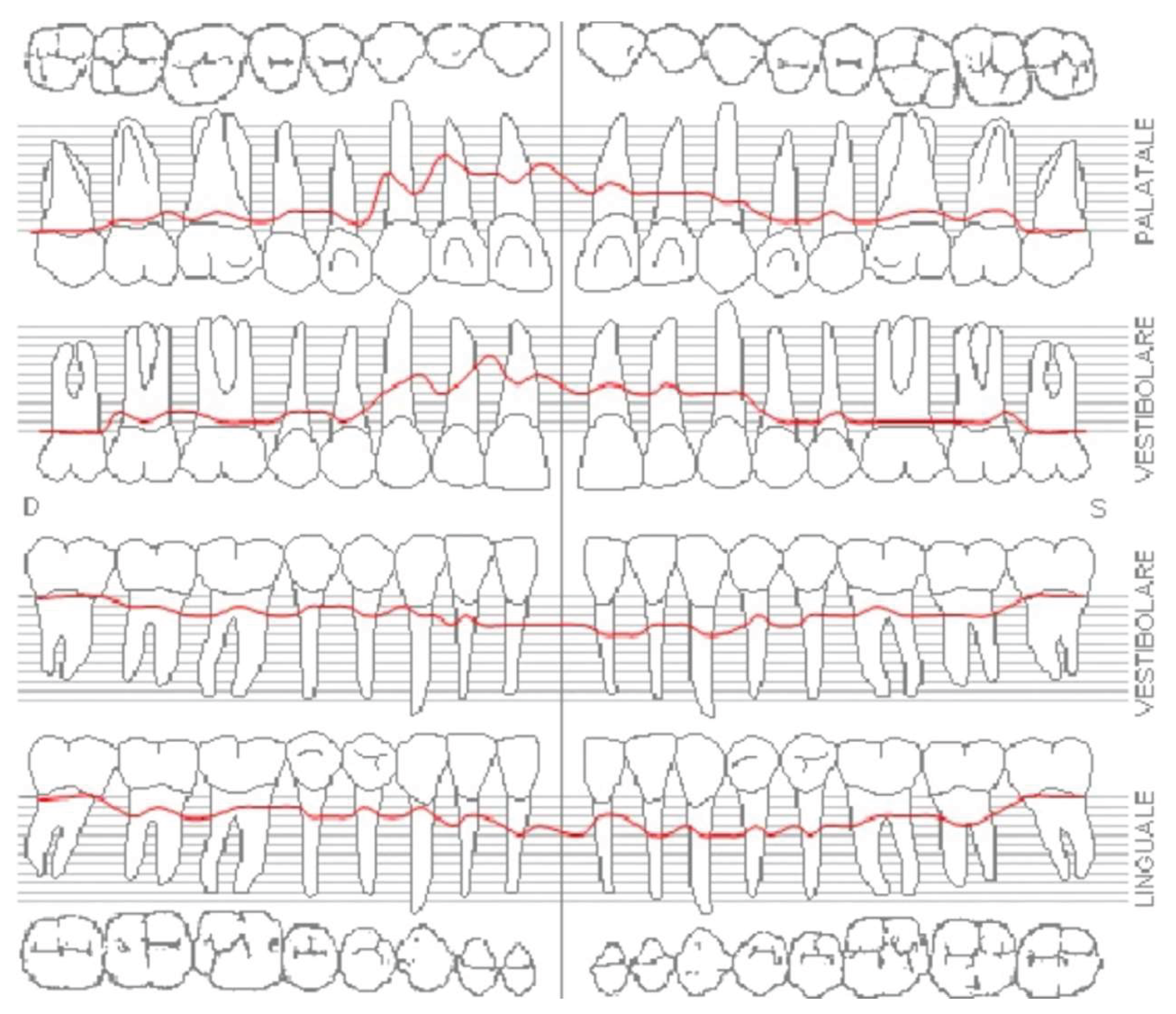

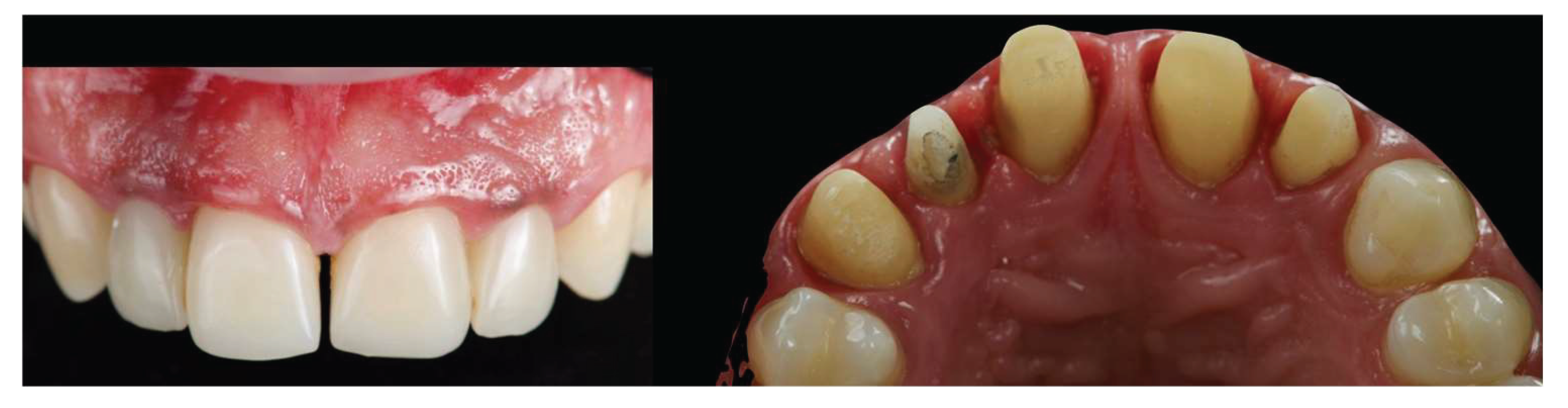

A 39-year-old male patient presented for prosthetic rehabilitation of the anterior maxillary region, primarily motivated by aesthetic concerns and periodontal health improvement. The patient reported a history of smoking (10–15 cigarettes per day) and had been diagnosed with Stage III, Grade B periodontitis. Initial clinical and radiographic evaluation (

Figure 1) revealed the absence of all four third molars, the presence of conservative restorations on teeth 1.6, 3.7, and 4.6, and evidence of horizontal alveolar bone resorption in the regions corresponding to teeth 1.4 and 2.3. A conoid morphology was noted in the upper left lateral incisor.

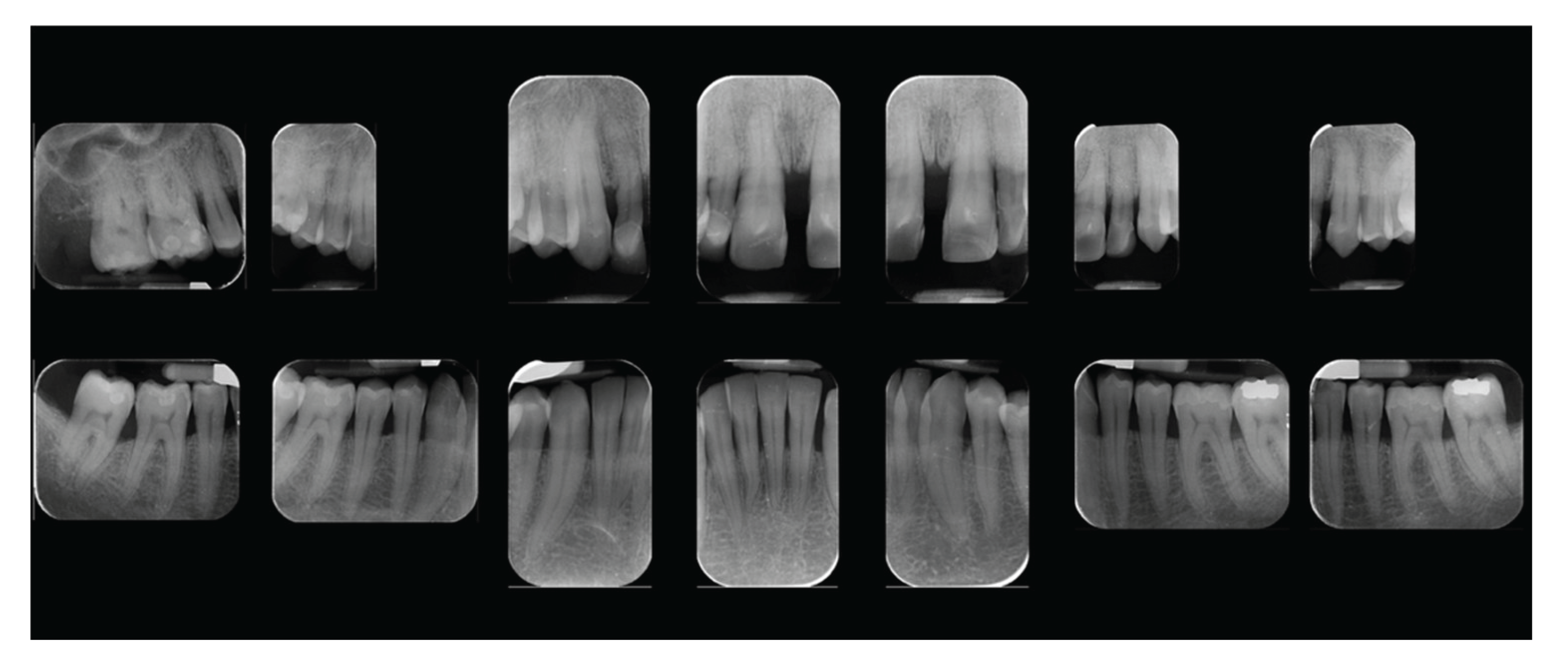

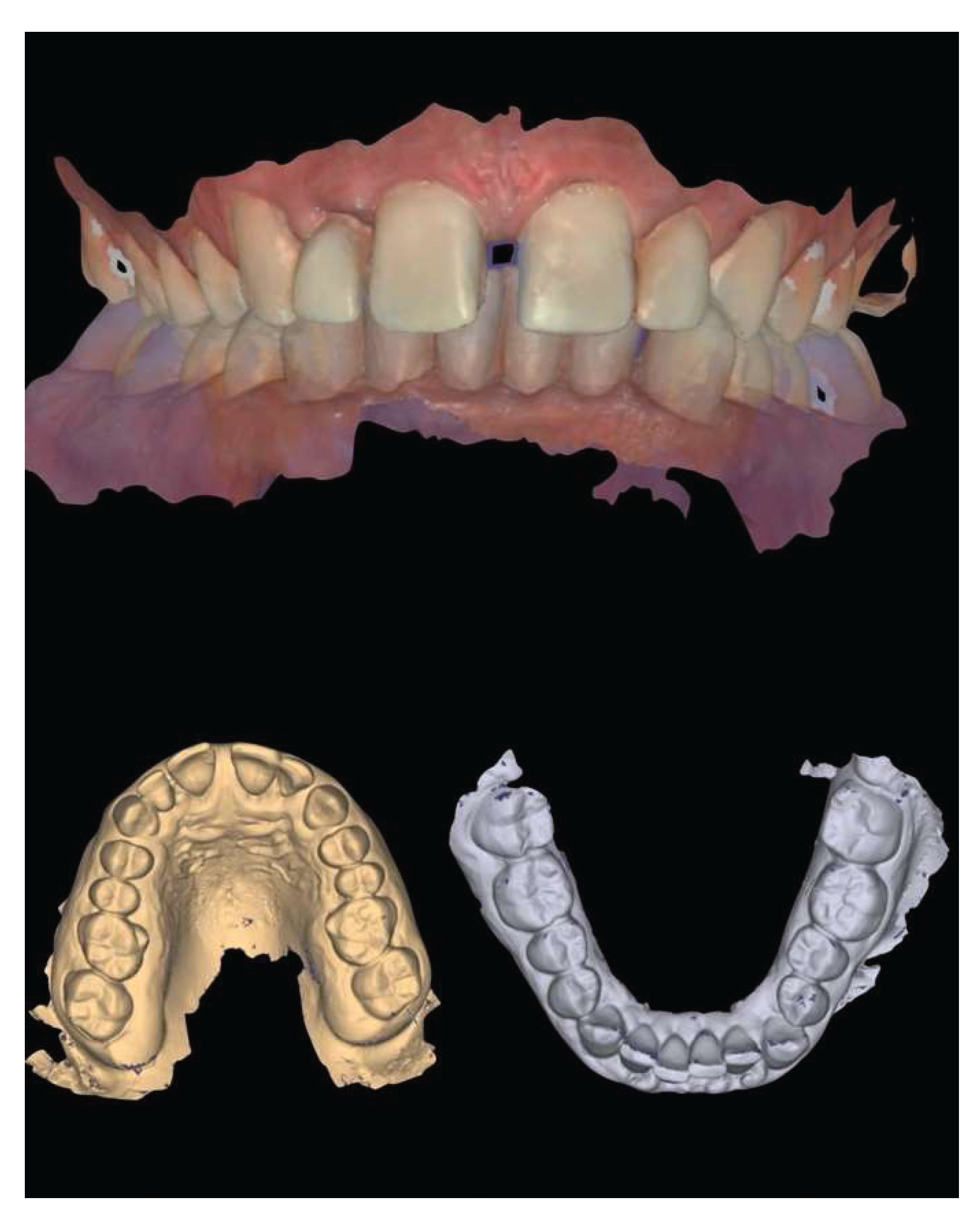

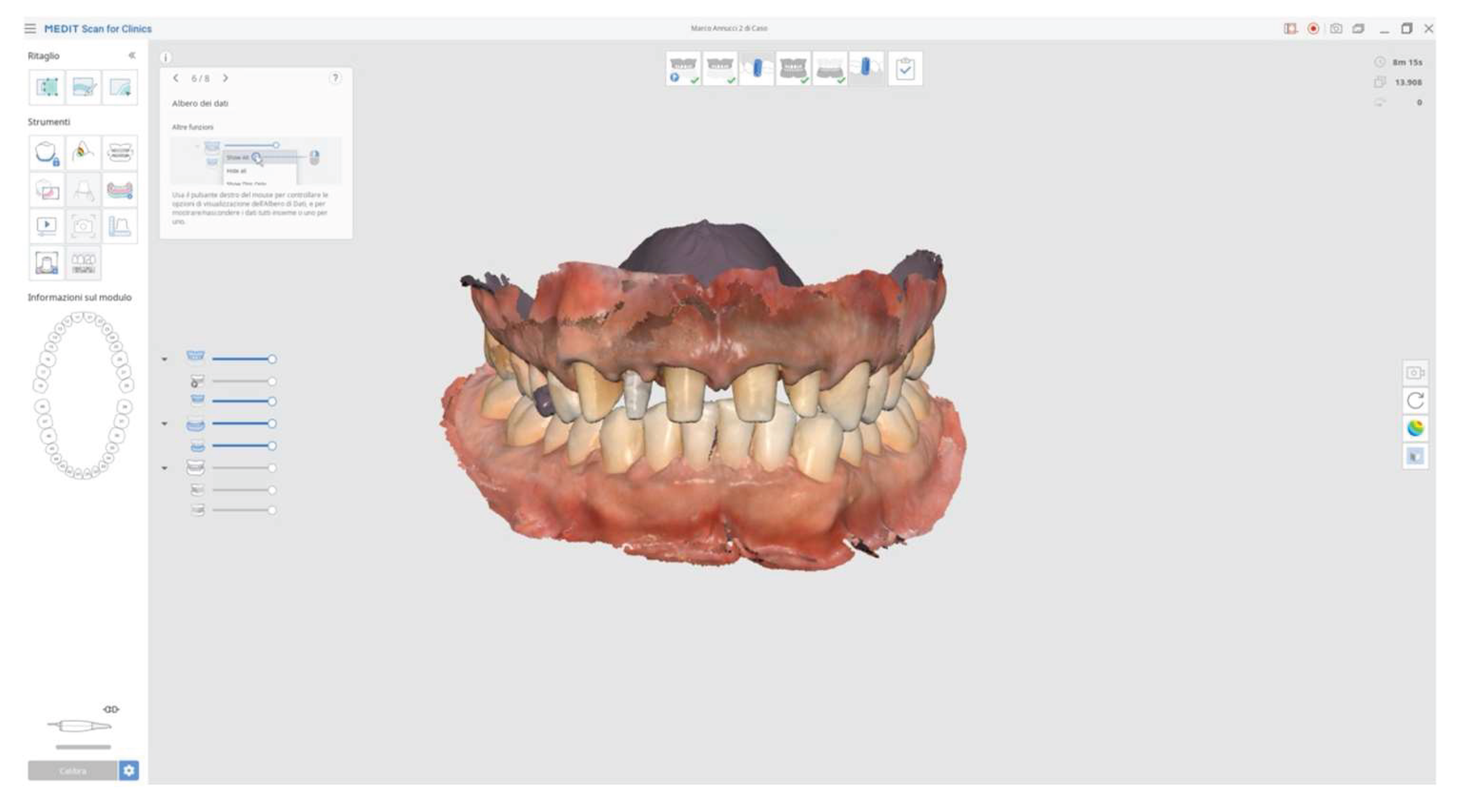

In addition to standard radiographs, a cone beam computed tomography (CBCT) scan was performed to obtain a three-dimensional assessment of the alveolar bone volume and morphology in the anterior maxillary region. Digital intraoral impressions were acquired using the Medit i500 scanner (MEDIT Corp., South Korea, Seoul,

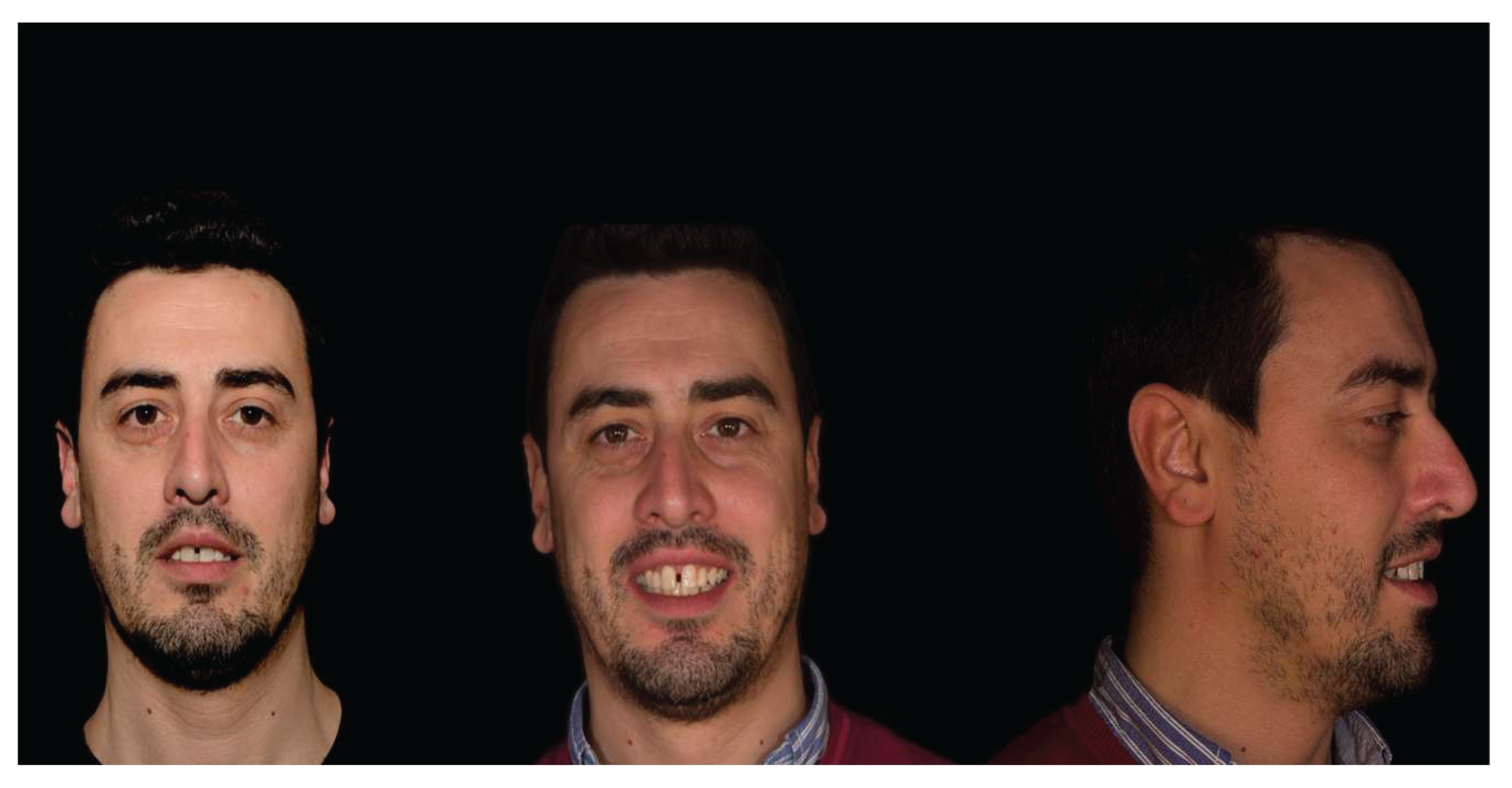

Figure 2), complemented by intraoral and extraoral photographic records for comprehensive facial and dento-labial analysis (

Figure 3 and

Figure 4), and aesthetic, predictive simulation using digital smile design software (Exocad Smile Creator, InCAD Smile Design, Exocad GmbH, Darmstadt, Germany).

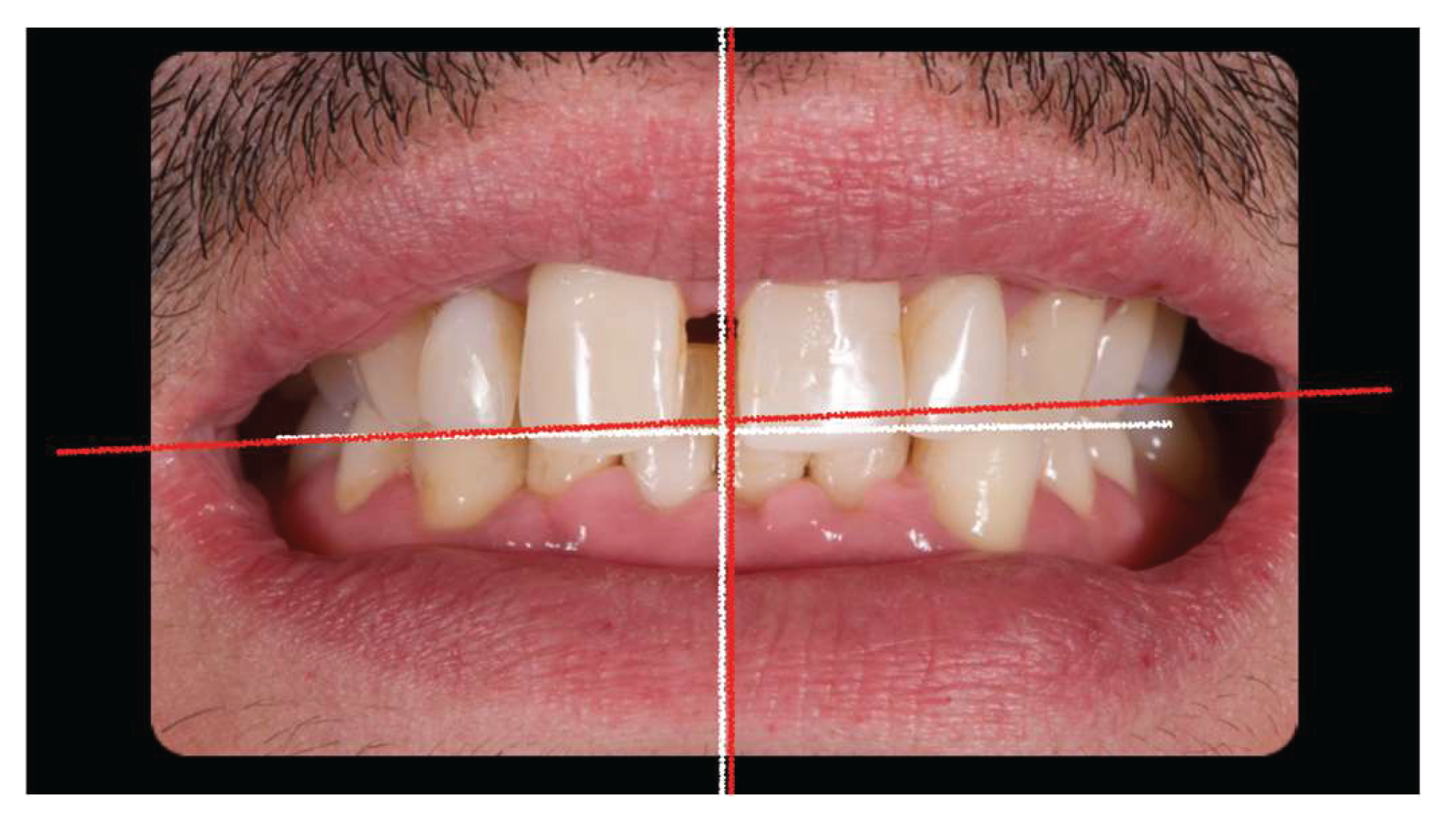

Initial esthetic evaluation revealed a 7 mm incisal display at rest, a flat incisal edge morphology, a high smile line, and a smile width encompassing ten teeth with normal buccal corridors. The facial midline was aligned with the interincisal midline, although a diastema was observed between teeth 1.1 and 2.1 (

Figure 5).

The occlusal plane appeared canted relative to both the labial commissure and the horizontal reference plane, whereas the interpupillary line was centered. Functional analysis demonstrated a minor discrepancy between centric relation and maximum intercuspation (0.5 mm), a deep bite, and group function occlusion. Evaluation of maxillary positioning, mandibular dynamics, and temporomandibular joint (TMJ) function was conducted using the Zebris Jaw Movement Analysis System (JMA, Zebris Medical GmbH, Germany). Periodontal assessment at baseline revealed a Stage III, Grade B periodontitis with a mean probing depth of 2.6 mm, mean sextant probing depth of 4.8 mm, clinical attachment loss averaging 2.2 mm, a plaque index of 12%, bleeding on probing at 16%, and Grade I mobility of teeth 1.1, 1.2, 2.1, and 2.2 (

Figure 6).

Following diagnostic evaluation and presentation of treatment alternatives, the proposed comprehensive rehabilitation plan was accepted.

Initial periodontal therapy.

First temporary restorations made up of a milled PMMA bridge from tooth 13 to 11 and a second one from tooth 21 to 22.

Endodontic therapy on tooth 22.

Second temporary restorations on definitive teeth preparations.

Definitive restorations made on porcelain fused to zirconia.

Maintenance periodontal therapy every four months.

Clinical Procedures

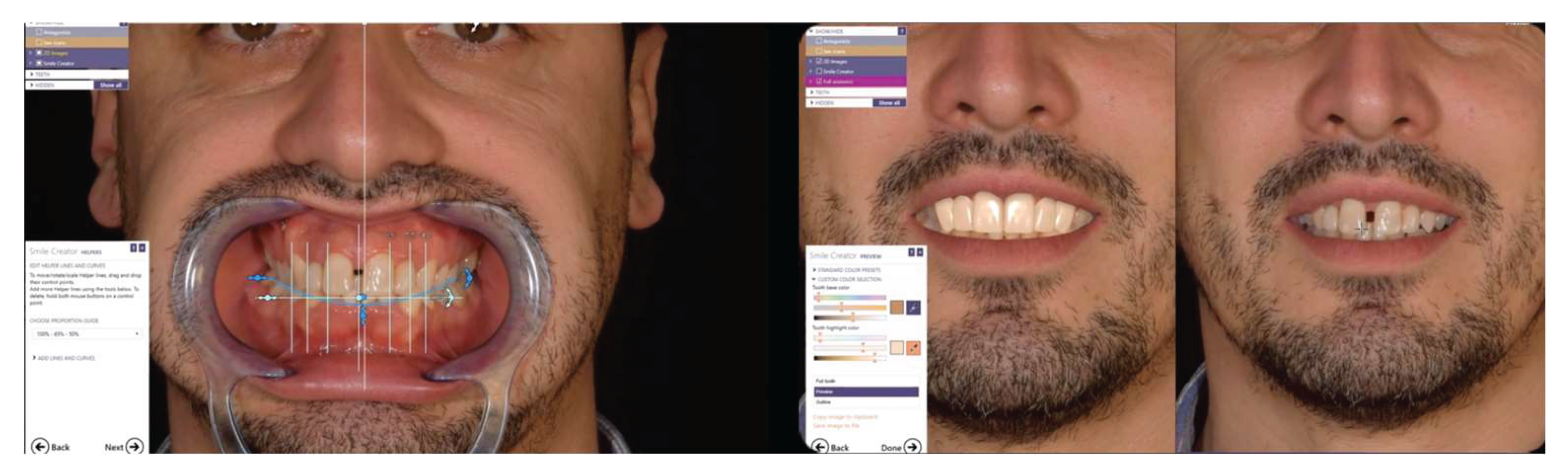

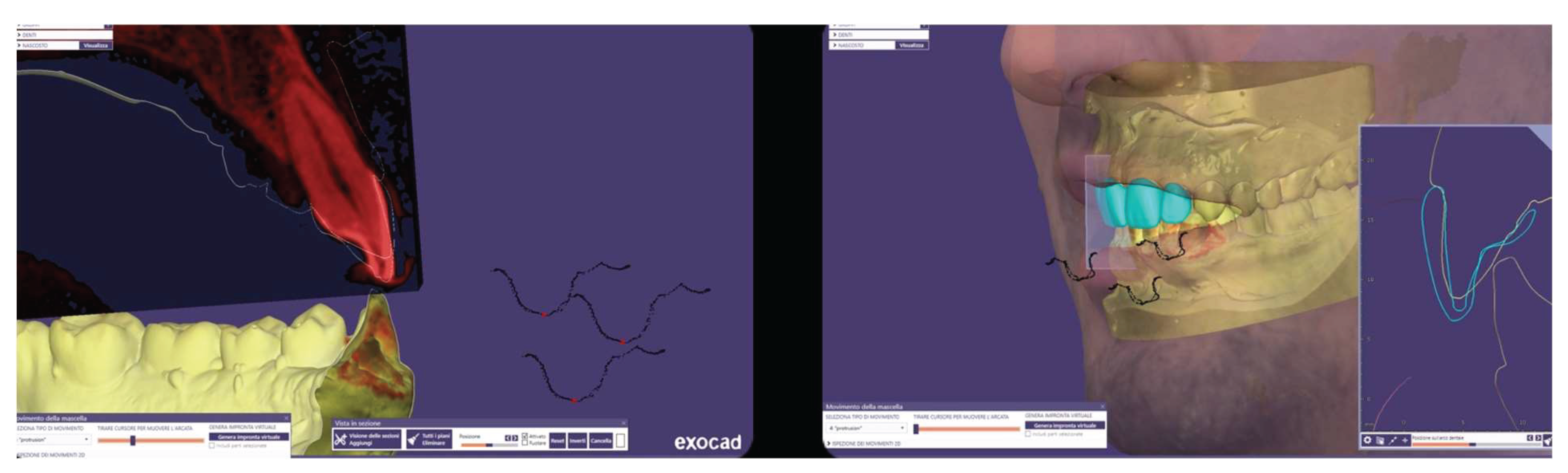

Initial periodontal therapy was performed, including non-surgical treatment in the second sextant. A provisional restoration was then designed through a digital laboratory workflow (CAD – Smile Creator) (

Figure 7) to simulate the final outcome and evaluate whether to maintain the interincisal diastema.

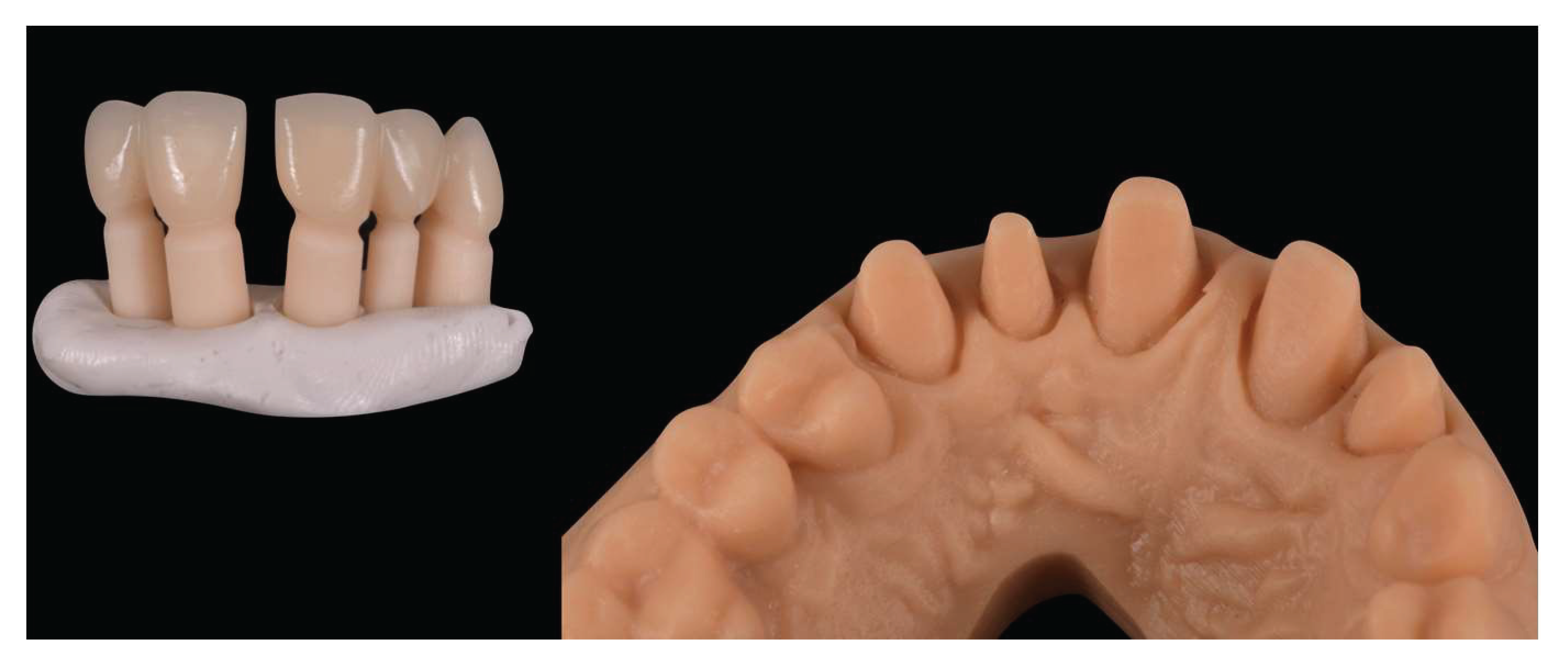

Since the patient declined orthodontic treatment, a pre-preparation provisional was fabricated to preserve the diastema, reduce overbite, and improve both anterior guidance and posterior group function. The initial extra oral photos with and without retractors were imported in exocad and converted to 3D objects, which can be matched to 3D scans of the teeth. Tooth shapes were selected from extensive library and edited by using dedicated editing tools. Highly realistic AI-based (artificial intelligence) smile makeover visualizations (TruSmile™ Video and TruSmile™ Photo, Exocad GmbH) based on individual tooth setups and treatment plans were obtained and discussed with the patient. Provisional restorations were fabricated by CAD/CAM milling in polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA) (

Figure 8).

Following completion of initial periodontal therapy, edgeless tooth preparations were performed on teeth 1.3, 1.2, 1.1, 2.1, and 2.2 using a Komet 6863D rotary instrument (Komet Italia SRL, Verona, Italy), in accordance with the principles of the biologically oriented preparation technique (BOPT) (

Figure 9).

The first set of provisional restorations (

Figure 10) was cemented using a non-eugenol temporary luting agent (Temp-Bond™ Clear).

These provisional were segmented into two units (right and left) and maintained the existing interincisal diastema. During the second provisional phase, tooth 1.2 developed symptoms of thermal sensitivity and mild pain, necessitating endodontic treatment. Approximately four months later, the preparations were refined under 16× magnification to optimize the emergence profiles and support soft tissue conditioning, while preserving the edgeless finish line to enhance papillary stability and control (

Figure 11).

The second provisional restorations (

Figure 12) were luted using zinc phosphate cement (Harvard) and mixed with petroleum jelly to facilitate later removal. At this stage, the interincisal diastema was closed.

Due to restrictions related to the COVID-19 health emergency, the final impression phase was delayed and performed nine months later, once soft tissue maturation had stabilized. Conventional impressions were obtained using the double-cord retraction technique (

Figure 13 and

Figure 14), followed by digital acquisition with the Medit i500 intraoral scanner (MEDIT Corp.,

Figure 14).

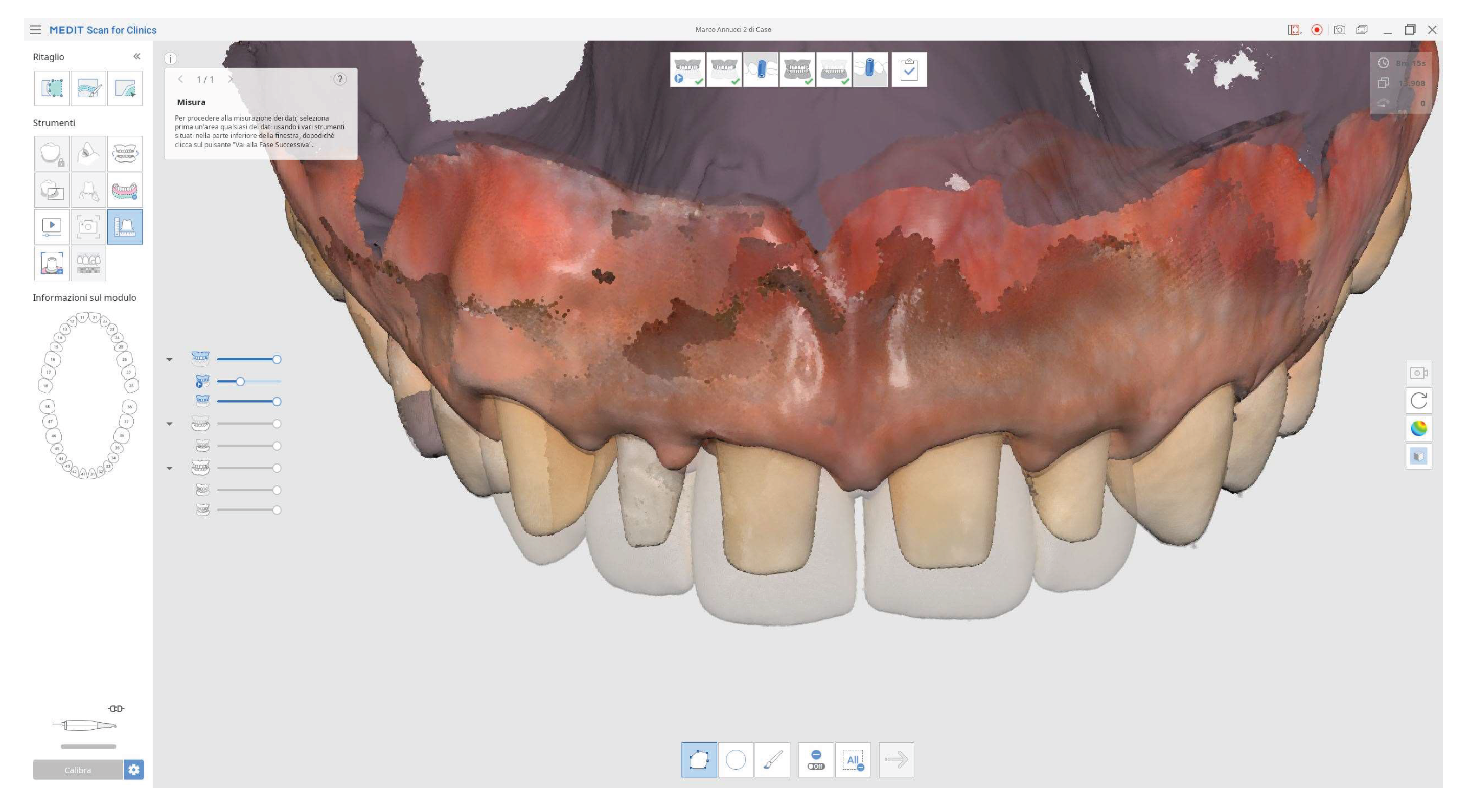

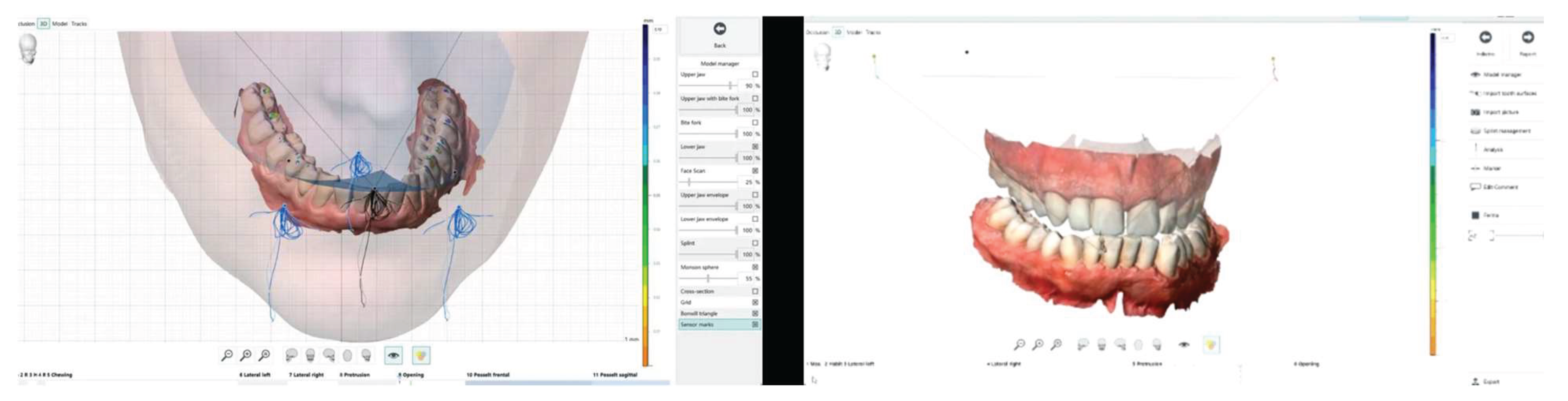

In addition, the provisional restorations were digitized, and mandibular movements, along with maxillary spatial orientation, were recorded using the Zebris Jaw Movement Analysis System (Zebris Medical GmbH,

Figure 15).

These records facilitated the individualized design of anterior guidance (

Figure 16), calibrated to the condylar pathway in order to achieve functional posterior disclusion. A centric relation position with a 1 mm long centric stop was established, and the vertical overlap (overbite) was further reduced.

A master model was generated, upon which a monolithic zirconia framework was fabricated and subsequently layered with feldspathic ceramic. A clinical try-in was conducted to assess the passive fit, aesthetic parameters, and functional integration of the definitive restorations. Final cementation was performed using a conventional glass ionomer luting agent (Ketac Cem Easy Clean, 3M Italia SRL, Milan, Italy,

Figure 17).

The patient was subsequently enrolled in a structured periodontal and prosthetic maintenance program, with follow-up evaluations scheduled at four-month intervals to monitor periodontal health, occlusal stability, and the integrity of the prosthetic components (

Figure 18 and

Figure 19).

Figure 18.

Final intraoral image.

Figure 18.

Final intraoral image.

Figure 19.

Intraoral image at four-year follow-up.

Figure 19.

Intraoral image at four-year follow-up.

Figure 20.

Four-year follow-up radiographic examination.

Figure 20.

Four-year follow-up radiographic examination.

At the four-year follow-up, clinical evaluation demonstrated stable soft and hard tissues, with no biological or mechanical complications observed throughout the entire follow-up period.

Discussion

Prosthetic rehabilitation in the aesthetic zone of periodontally compromised patients presents a multifactorial clinical challenge, requiring the integration of aesthetic, functional, and biological considerations within a framework of risk management and long-term stability. In the present case, the presence of Stage III periodontitis, occlusal discrepancies, tooth mobility, and an altered occlusal plane necessitated a comprehensive and minimally invasive treatment plan, supported by digital technologies and interdisciplinary collaboration. A key component of the approach was the strategic management of the interincisal diastema. Initially preserved in the first set of provisional restorations, the diastema allowed for gradual patient adaptation both functionally and aesthetically. Its subsequent closure during the advanced provisional phase was guided by aesthetic simulations using digital smile design software, which facilitated informed patient involvement and optimized treatment acceptance.10

The overall digital workflow, incorporating intraoral scanning, mandibular motion tracking, and CAD/CAM design, proved essential in ensuring diagnostic accuracy and clinical predictability. These tools, someone base on AI, allowed for high-precision execution, streamlined communication between clinical and laboratory teams, and enhanced control over prosthetic and occlusal parameters.2,7-9 In particular, the use of digital mandibular motion registration enabled the creation of a customized anterior guidance scheme, improving posterior disclusion and contributing to the correction of the deep bite.9 Tooth preparation followed the biologically oriented preparation technique (BOPT), employing edgeless margins to preserve coronal structure and support gingival tissue stability. This approach is particularly advantageous in periodontally compromised patients, where interdental papilla preservation and emergence profile control are critical for long-term aesthetic success.11,12 Customized provisional restorations were dynamically adapted over the course of treatment. Beyond their aesthetic function, they facilitated soft tissue conditioning, refinement of occlusal relationships, and real-time monitoring of the periodontal response. Although one unplanned endodontic procedure was necessary due to post-operative sensitivity, no significant biological or mechanical complications occurred throughout the remainder of the treatment.

At the four-year follow-up, the clinical situation remained stable and asymptomatic. Periodontal evaluation revealed probing depths within physiological limits, a low plaque index (7%), and minimal bleeding on probing (8%), all consistent with a healthy periodontal environment. Radiographic assessment confirmed the maintenance of alveolar bone levels without signs of resorption. The patient’s reduction in tobacco use and adherence to four-month maintenance therapy intervals likely played a pivotal role in sustaining these outcomes. The four-year follow-up also confirmed the clinical stability of the treatment, both occlusally and periodontally, with a significant improvement in clinical indices and complete patient satisfaction. Masticatory function remained effective, the deep bite was corrected, and the interincisal diastema was successfully closed, resulting in a harmonious and stable aesthetic outcome. The final decision to fabricate individual crowns was justified by the favorable tissue response and the occlusal stability achieved.

The management of a periodontally compromised patient with high aesthetic demands required an interdisciplinary approach, grounded in careful planning and the integration of digital tools and conservative techniques. The clinical case presented demonstrated how the combination of targeted periodontal therapy, minimally invasive tooth preparations, digital occlusal registration, and customized CAD/CAM restorations can lead to predictable and durable aesthetic, functional, and biological outcomes.

Conclusions

This case highlights the importance of regular follow-up, patient cooperation, and the use of digital technologies in improving accuracy, clinical efficiency, and the long-term success of complex prosthetic rehabilitations.

References

- Mangano Guest Editor F. Digital Dentistry: The Revolution has Begun. Open Dent J. 2018 Jan 31;12:59-60. PMID: 29492170; PMCID: PMC5814950. [CrossRef]

- Tallarico, M. Computerization and Digital Workflow in Medicine: Focus on Digital Dentistry. Materials 2020, 13, 2172. [CrossRef]

- Kihara H, Hatakeyama W, Komine F, Takafuji K, Takahashi T, Yokota J, Oriso K, Kondo H. Accuracy and practicality of intraoral scanner in dentistry: A literature review. J Prosthodont Res. 2020 Apr;64(2):109-113. Epub 2019 Aug 30. PMID: 31474576. [CrossRef]

- Papaspyridakos P, Vazouras K, Chen YW, Kotina E, Natto Z, Kang K, Chochlidakis K. Digital vs Conventional Implant Impressions: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Prosthodont. 2020 Oct;29(8):660-678. Epub 2020 Jul 16. PMID: 32613641. [CrossRef]

- Ahrberg D, Lauer HC, Ahrberg M, Weigl P. Evaluation of fit and efficiency of CAD/CAM fabricated all-ceramic restorations based on direct and indirect digitalization: a double-blinded, randomized clinical trial. Clin Oral Investig. 2016 Mar;20(2):291-300. Epub 2015 Jun 14. PMID: 26070435. [CrossRef]

- Alghazzawi TF. Advancements in CAD/CAM technology: Options for practical implementation. J Prosthodont Res. 2016 Apr;60(2):72-84. Epub 2016 Feb 28. PMID: 26935333. [CrossRef]

- Risciotti E, Squadrito N, Montanari D, Iannello G, Macca U, Tallarico M, Cervino G, Fiorillo L. Digital Protocol to Record Occlusal Analysis in Prosthodontics: A Pilot Study. J Clin Med. 2024 Feb 28;13(5):1370. PMID: 38592229; PMCID: PMC10931913. [CrossRef]

- Zimmermann M, Mehl A, Mörmann WH, Reich S. Intraoral scanning systems - a current overview. Int J Comput Dent. 2015;18(2):101-29. English, German. PMID: 26110925.

- Kordass, B., Bernhardt, O., Ratzmann, A., Hugger, S., & Hugger, A. (2014). Standard and limit values of mandibular condylar and incisal movement capacity. International journal of computerized dentistry, 17(1), 9–20.

- Georg R. (2023). Digital Smile Design: Utilizing Novel Technologies for Ultimate Esthetics. Compendium of continuing education in dentistry (Jamesburg, N.J. : 1995), 44(10), 567–573.

- Abad-Coronel, C., Villacís Manosalvas, J., Palacio Sarmiento, C., Esquivel, J., Loi, I., & Pradíes, G. (2024). Clinical outcomes of the biologically oriented preparation technique (BOPT) in fixed dental prostheses: A systematic review. The Journal of prosthetic dentistry, 132(3), 502–508. [CrossRef]

- Tallarico, M.; Cuccu, M.; Meloni, S.M.; Lumbau, A.I.; Baldoni, E.; Pisano, M.; Fiorillo, L.; Cervino, G. Digital Analysis of a Novel Impression Method Named the Biological-Oriented Digital Impression Technique: A Clinical Audit. Prosthesis 2023, 5, 992-1001. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).