Submitted:

07 June 2025

Posted:

09 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

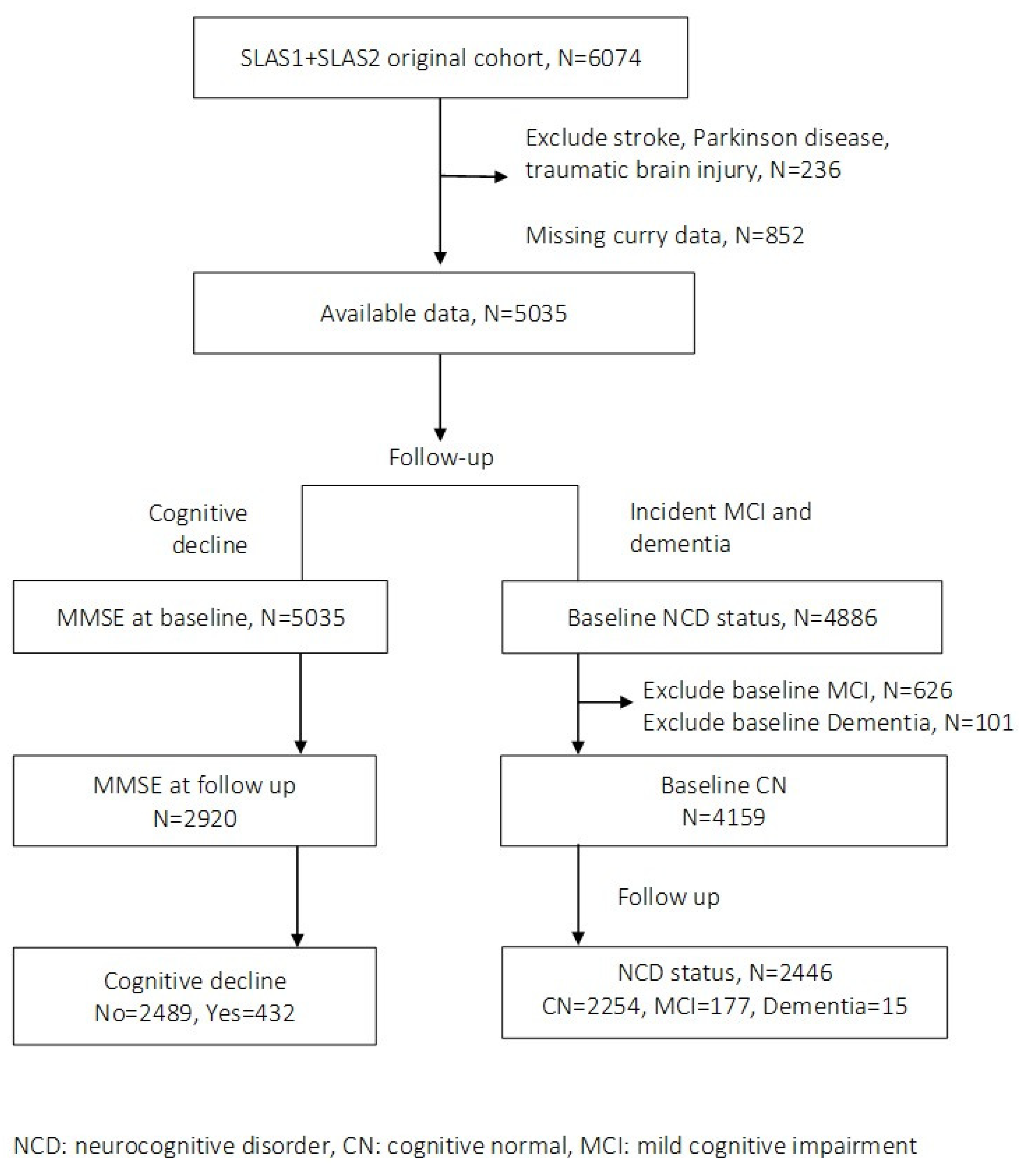

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

2.2. Measurements

2.2.1. Curry Consumption

2.2.2. Diagnosis of Neurocognitive Disorder (MCI and Dementia)

2.2.3. Covariates

2.3. Analysis

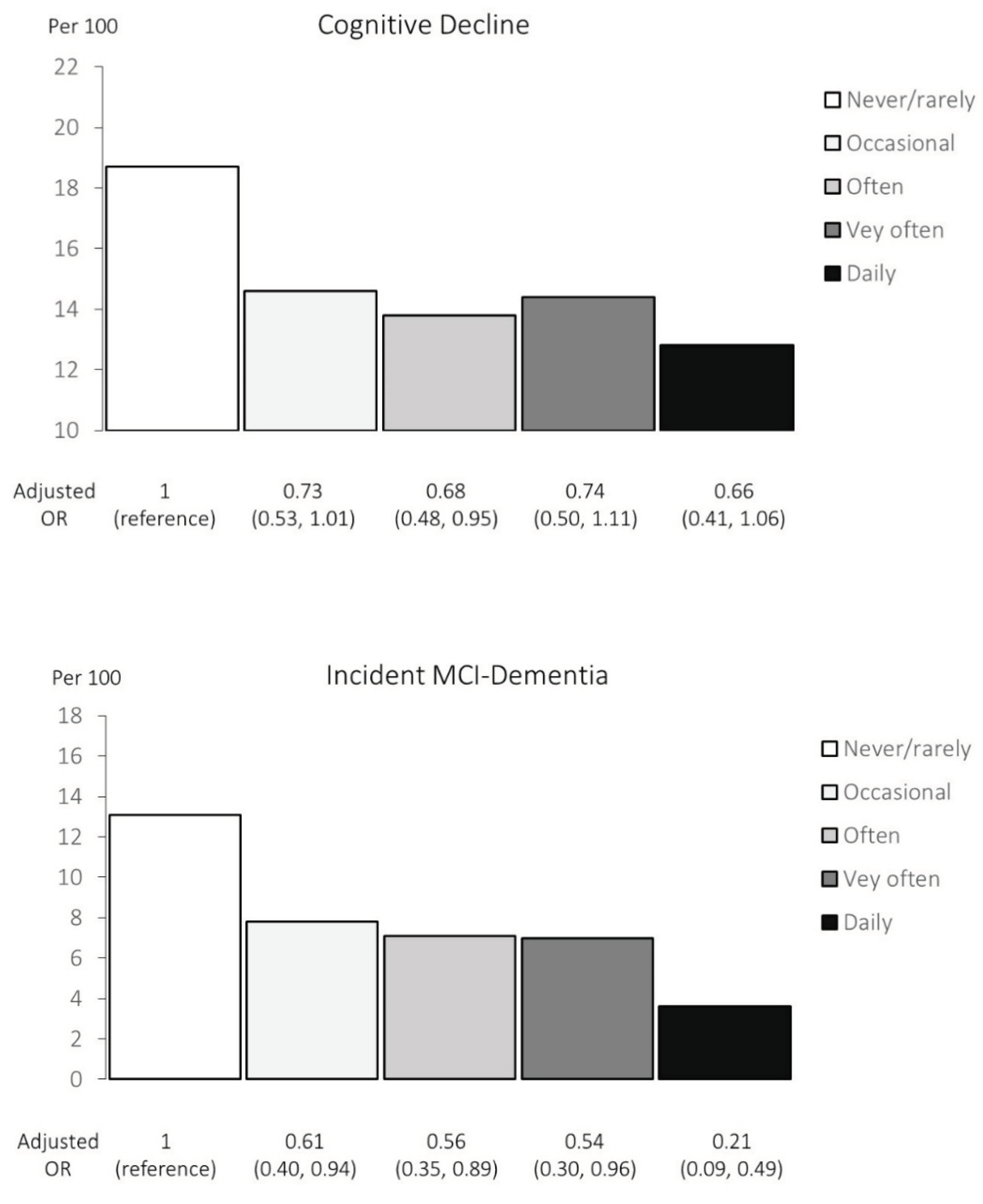

3. Results

3.1. Cognitive Decline

3.2. Incident MCI-Dementia

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Aβ | β amyloid |

| MMSE | Mini-Mental State Examination |

| SLAS | Singapore Longitudinal Ageing Study |

| CDR | Clinical Dementia Scale |

| SD | standard deviation |

| BADL | Basic Activities of Daily Living |

| CN | cognitively normal |

| GDS | Geriatric Depression Scale |

| OR | odds ratio |

| CI | confidence interval |

| SAM | senescence accelerated mouse |

| MWM | Morris Water Maze |

| SD | Sprague Dawley |

| LTP | long-term potentiation |

| NOL | novel object location |

| MoCA | Montreal Cognitive Assessment |

| APP | amyloid precursor protein |

References

- Salehi B, Stojanović-Radić Z, Matejić J, Sharifi-Rad M, Anil Kumar NV, Martins N, et al. The therapeutic potential of curcumin: A review of clinical trials. European Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 2019;163:527-45. [CrossRef]

- Nicoliche T, Bartolomeo CS, Lemes RMR, Pereira GC, Nunes TA, Oliveira RB, et al. Antiviral, anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effects of curcumin and curcuminoids in SH-SY5Y cells infected by SARS-CoV-2. Scientific Reports. 2024;14(1):10696. [CrossRef]

- Fu Y-S, Chen T-H, Weng L, Huang L, Lai D, Weng C-F. Pharmacological properties and underlying mechanisms of curcumin and prospects in medicinal potential. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy. 2021;141:111888. [CrossRef]

- Sarker MR, Franks SF. Efficacy of curcumin for age-associated cognitive decline: a narrative review of preclinical and clinical studies. GeroScience. 2018;40(2):73-95. Epub 2018/04/22. PubMed PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC5964053. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zang W-B, Wei H-L, Zhang W-W, Ma W, Li J, Yao Y. Curcumin hybrid molecules for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease: Structure and pharmacological activities. European Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 2024;265:116070. [CrossRef]

- Lo Cascio F, Puangmalai N, Ellsworth A, Bucchieri F, Pace A, Palumbo Piccionello A, et al. Toxic Tau Oligomers Modulated by Novel Curcumin Derivatives. Scientific Reports. 2019;9(1):19011. [CrossRef]

- Benameur T, Giacomucci G, Panaro MA, Ruggiero M, Trotta T, Monda V, et al. New Promising Therapeutic Avenues of Curcumin in Brain Diseases. Molecules (Basel, Switzerland). 2021;27(1). Epub 2022/01/12. PubMed PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC8746812. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen M, Du ZY, Zheng X, Li DL, Zhou RP, Zhang K. Use of curcumin in diagnosis, prevention, and treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. Neural regeneration research. 2018;13(4):742-52. Epub 2018/05/04. PubMed PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC5950688. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Askarizadeh A, Barreto GE, Henney NC, Majeed M, Sahebkar A. Neuroprotection by curcumin: A review on brain delivery strategies. International journal of pharmaceutics. 2020;585:119476. Epub 2020/05/31. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pradeep H, Yenisetti SC, Rajini PS, Muralidhara M. Chapter 16 - Neuroprotective Propensity of Curcumin: Evidence in Animal Models, Mechanisms, and Its Potential Therapeutic Value. In: Farooqui T, Farooqui AA, editors. Curcumin for Neurological and Psychiatric Disorders: Academic Press; 2019. p. 301-23.

- Zhang C, Browne A, Child D, Tanzi RE. Curcumin Decreases Amyloid-β Peptide Levels by Attenuating the Maturation of Amyloid-β Precursor Protein*. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2010;285(37):28472-80. [CrossRef]

- Bozkurt O, Kocaadam-Bozkurt B, Yildiran H. Effects of curcumin, a bioactive component of turmeric, on type 2 diabetes mellitus and its complications: an updated review. Food & Function. 2022;13(23):11999-2010. [CrossRef]

- Tabeshpour J, Hashemzaei M, Sahebkar A. The regulatory role of curcumin on platelet functions. Journal of cellular biochemistry. 2018;119(11):8713-22. Epub 2018/08/12. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li H, Sureda A, Devkota HP, Pittalà V, Barreca D, Silva AS, et al. Curcumin, the golden spice in treating cardiovascular diseases. Biotechnology advances. 2020;38:107343. Epub 2019/02/05. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bai X-J, Hao J-T, Wang J, Zhang W-F, Yan C-P, Zhao J-H, et al. Curcumin inhibits cardiac hypertrophy and improves cardiovascular function via enhanced Na+/Ca2+ exchanger expression after transverse abdominal aortic constriction in rats. Pharmacological Reports. 2018;70(1):60-8. [CrossRef]

- Cox FF, Misiou A, Vierkant A, Ale-Agha N, Grandoch M, Haendeler J, et al. Protective Effects of Curcumin in Cardiovascular Diseases-Impact on Oxidative Stress and Mitochondria. Cells. 2022;11(3). Epub 2022/02/16. PubMed PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC8833931. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saeidinia A, Keihanian F, Butler AE, Bagheri RK, Atkin SL, Sahebkar A. Curcumin in heart failure: A choice for complementary therapy? Pharmacological Research. 2018;131:112-9. [CrossRef]

- Hussain Y, Abdullah, Khan F, Alsharif KF, Alzahrani KJ, Saso L, et al. Regulatory Effects of Curcumin on Platelets: An Update and Future Directions. Biomedicines. 2022;10(12). Epub 2022/12/24. PubMed PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC9775400. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marton LT, Pescinini-e-Salzedas LM, Camargo MEC, Barbalho SM, Haber JFdS, Sinatora RV, et al. The Effects of Curcumin on Diabetes Mellitus: A Systematic Review. Frontiers in Endocrinology. 2021;12. [CrossRef]

- Fan L, Zhang Z. Therapeutic potential of curcumin on the cognitive decline in animal models of Alzheimer’s disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg’s Archives of Pharmacology. 2024;397(7):4499-509. [CrossRef]

- Sun CY, Qi SS, Zhou P, Cui HR, Chen SX, Dai KY, et al. Neurobiological and pharmacological validity of curcumin in ameliorating memory performance of senescence-accelerated mice. Pharmacology, biochemistry, and behavior. 2013;105:76-82. Epub 2013/02/14. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hishikawa N, Takahashi Y, Amakusa Y, Tanno Y, Tuji Y, Niwa H, et al. Effects of turmeric on Alzheimer’s disease with behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia. Ayu. 2012;33(4):499-504. Epub 2013/06/01. PubMed PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC3665200. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cox KH, Pipingas A, Scholey AB. Investigation of the effects of solid lipid curcumin on cognition and mood in a healthy older population. Journal of psychopharmacology (Oxford, England). 2015;29(5):642-51. Epub 2014/10/04. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rainey-Smith SR, Brown BM, Sohrabi HR, Shah T, Goozee KG, Gupta VB, et al. Curcumin and cognition: a randomised, placebo-controlled, double-blind study of community-dwelling older adults. The British journal of nutrition. 2016;115(12):2106-13. Epub 2016/04/23. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cox KHM, White DJ, Pipingas A, Poorun K, Scholey A. Further Evidence of Benefits to Mood and Working Memory from Lipidated Curcumin in Healthy Older People: A 12-Week, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled, Partial Replication Study. Nutrients. 2020;12(6). Epub 2020/06/10. PubMed PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC7352411. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Das SS, Gopal PM, Thomas JV, Mohan MC, Thomas SC, Maliakel BP, et al. Influence of CurQfen(®)-curcumin on cognitive impairment: a randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled, 3-arm, 3-sequence comparative study. Frontiers in dementia. 2023;2:1222708. Epub 2024/07/31. PubMed PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC11285547. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ng TP, Chiam PC, Lee T, Chua HC, Lim L, Kua EH. Curry consumption and cognitive function in the elderly. American journal of epidemiology. 2006;164(9):898-906. Epub 2006/07/28. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ng TP, Nyunt MSZ, Gao Q, Gwee X, Chua DQL, Yap KB. Curcumin-Rich Curry Consumption and Neurocognitive Function from 4.5-Year Follow-Up of Community-Dwelling Older Adults (Singapore Longitudinal Ageing Study). Nutrients. 2022;14(6). Epub 2022/03/27. PubMed PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC8952785. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ng TP, Feng L, Nyunt MS, Feng L, Gao Q, Lim ML, et al. Metabolic Syndrome and the Risk of Mild Cognitive Impairment and Progression to Dementia: Follow-up of the Singapore Longitudinal Ageing Study Cohort. JAMA neurology. 2016;73(4):456-63. Epub 2016/03/02. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niti M, Yap KB, Kua EH, Tan CH, Ng TP. Physical, social and productive leisure activities, cognitive decline and interaction with APOE-epsilon 4 genotype in Chinese older adults. International psychogeriatrics. 2008;20(2):237-51. Epub 2008/01/15. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ng TP, Niti M, Chiam PC, Kua EH. Ethnic and educational differences in cognitive test performance on mini-mental state examination in Asians. The American journal of geriatric psychiatry : official journal of the American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry. 2007;15(2):130-9. Epub 2007/02/03. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheung YB, Xu Y, Feng L, Feng L, Nyunt MS, Chong MS, et al. Unconditional and Conditional Standards Using Cognitive Function Curves for the Modified Mini-Mental State Exam: Cross-Sectional and Longitudinal Analyses in Older Chinese Adults in Singapore. The American journal of geriatric psychiatry : official journal of the American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry. 2015;23(9):915-24. Epub 2014/09/28. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jorm AF, Scott R, Cullen JS, MacKinnon AJ. Performance of the Informant Questionnaire on Cognitive Decline in the Elderly (IQCODE) as a screening test for dementia. Psychological medicine. 1991;21(3):785-90. Epub 1991/08/01. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cherbuin N, Anstey KJ, Lipnicki DM. Screening for dementia: a review of self- and informant-assessment instruments. International psychogeriatrics. 2008;20(3):431-58. Epub 2008/02/22. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng L, Ng TP, Chuah L, Niti M, Kua EH. Homocysteine, folate, and vitamin B-12 and cognitive performance in older Chinese adults: findings from the Singapore Longitudinal Ageing Study. The American journal of clinical nutrition. 2006;84(6):1506-12. Epub 2006/12/13. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee CK, Collinson SL, Feng L, Ng TP. Preliminary normative neuropsychological data for an elderly chinese population. The Clinical neuropsychologist. 2012;26(2):321-34. Epub 2012/02/01. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Segal, DL. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV-TR). The Corsini Encyclopedia of Psychology. p. 1-3.

- Morris, JC. The Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR): current version and scoring rules. Neurology. 1993;43(11):2412-4. Epub 1993/11/01. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee YS, Biddle S, Chan MF, Cheng A, Cheong M, Chong YS, et al. Health Promotion Board-Ministry of Health Clinical Practice Guidelines: Obesity. Singapore medical journal. 2016;57(6):292-300. Epub 2016/06/30. PubMed PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC4971447. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tay JC, Sule AA, Chew EK, Tey JS, Lau T, Lee S, et al. Ministry of Health Clinical Practice Guidelines: Hypertension. Singapore medical journal. 2018;59(1):17-27. Epub 2018/01/30. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goh SY, Ang SB, Bee YM, Chen YT, Gardner DS, Ho ET, et al. Ministry of Health Clinical Practice Guidelines: Diabetes Mellitus. Singapore medical journal. 2014;55(6):334-47. Epub 2014/07/16. PubMed PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC4294061. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tai ES, Chia BL, Bastian AC, Chua T, Ho SC, Koh TS, et al. Ministry of Health Clinical Practice Guidelines: Lipids. Singapore medical journal. 2017;58(3):155-66. Epub 2017/04/01. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nyunt MS, Fones C, Niti M, Ng TP. Criterion-based validity and reliability of the Geriatric Depression Screening Scale (GDS-15) in a large validation sample of community-living Asian older adults. Aging & mental health. 2009;13(3):376-82. Epub 2009/06/02. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuszewski JC, Wong RHX, Howe PRC. Can Curcumin Counteract Cognitive Decline? Clinical Trial Evidence and Rationale for Combining ω-3 Fatty Acids with Curcumin. Advances in nutrition (Bethesda, Md). 2018;9(2):105-13. Epub 2018/04/17. PubMed PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC5916424. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen Q, Prior M, Dargusch R, Roberts A, Riek R, Eichmann C, et al. A novel neurotrophic drug for cognitive enhancement and Alzheimer’s disease. PloS one. 2011;6(12):e27865. Epub 2011/12/24. PubMed PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC3237323. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rainey-Smith SR, Brown BM, Sohrabi HR, Shah T, Goozee KG, Gupta VB, et al. Curcumin and cognition: a randomised, placebo-controlled, double-blind study of community-dwelling older adults. British Journal of Nutrition. 2016;115(12):2106-13. Epub 04/22. [CrossRef]

- Murrow L, Debnath J. Autophagy as a Stress-Response and Quality-Control Mechanism: Implications for Cell Injury and Human Disease. Annual Review of Pathology: Mechanisms of Disease. 2013;8(Volume 8, 2013):105-37. [CrossRef]

- Ravanan P, Srikumar IF, Talwar P. Autophagy: The spotlight for cellular stress responses. Life Sciences. 2017;188:53-67. [CrossRef]

- Wang C, Zhang X, Teng Z, Zhang T, Li Y. Downregulation of PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway in curcumin-induced autophagy in APP/PS1 double transgenic mice. European Journal of Pharmacology. 2014;740:312-20. [CrossRef]

- Park S-Y, Kim H-S, Cho E-K, Kwon B-Y, Phark S, Hwang K-W, et al. Curcumin protected PC12 cells against beta-amyloid-induced toxicity through the inhibition of oxidative damage and tau hyperphosphorylation. Food and Chemical Toxicology. 2008;46(8):2881-7. [CrossRef]

- Zhang L, Fiala M, Cashman J, Sayre J, Espinosa A, Mahanian M, et al. Curcuminoids enhance amyloid-beta uptake by macrophages of Alzheimer’s disease patients. Journal of Alzheimer’s disease : JAD. 2006;10(1):1-7. Epub 2006/09/22. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim H, Park BS, Lee KG, Choi CY, Jang SS, Kim YH, et al. Effects of naturally occurring compounds on fibril formation and oxidative stress of beta-amyloid. Journal of agricultural and food chemistry. 2005;53(22):8537-41. Epub 2005/10/27. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ono K, Hasegawa K, Naiki H, Yamada M. Curcumin has potent anti-amyloidogenic effects for Alzheimer’s beta-amyloid fibrils in vitro. Journal of neuroscience research. 2004;75(6):742-50. Epub 2004/03/03. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang F, Lim GP, Begum AN, Ubeda OJ, Simmons MR, Ambegaokar SS, et al. Curcumin inhibits formation of amyloid beta oligomers and fibrils, binds plaques, and reduces amyloid in vivo. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2005;280(7):5892-901. Epub 2004/12/14. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shimmyo Y, Kihara T, Akaike A, Niidome T, Sugimoto H. Epigallocatechin-3-gallate and curcumin suppress amyloid beta-induced beta-site APP cleaving enzyme-1 upregulation. Neuroreport. 2008;19(13):1329-33. Epub 2008/08/13. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin R, Chen X, Li W, Han Y, Liu P, Pi R. Exposure to metal ions regulates mRNA levels of APP and BACE1 in PC12 cells: blockage by curcumin. Neuroscience letters. 2008;440(3):344-7. Epub 2008/06/28. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed T, Gilani AH, Hosseinmardi N, Semnanian S, Enam SA, Fathollahi Y. Curcuminoids rescue long-term potentiation impaired by amyloid peptide in rat hippocampal slices. Synapse (New York, NY). 2011;65(7):572-82. Epub 2010/10/22. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moghaddam NSA, Oskouie MN, Butler AE, Petit PX, Barreto GE, Sahebkar A. Hormetic effects of curcumin: What is the evidence? Journal of cellular physiology. 2019;234(7):10060-71. Epub 2018/12/06. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Never or rarely | Occasional | Often | Very Often | Daily | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Never or <once/year) | (>once/year, <once/month) | (>once/month, <once/week) | (>once/week, not daily) | (≥ once daily) | P | |||

| N of participants | 417 | 1030 | 805 | 395 | 273 | |||

| Sex: Women | 71.5 (298) | 70.6 (727) | 63.2 (509) | 58.0 (229) | 52.0 (142) | <0.001 | ||

| Age, years | 66.4 ± 7.3 | 65.7 ± 7.0 | 65.6 ± 7.2 | 64.9 ± 7.1 | 64.4 ± 6.7 | 0.003 | ||

| Ethnicity: Chinese | 98.6 (411) | 97.4 (1003) | 93.4 (752) | 89.9 (355) | 75.5 (206) | |||

| Malay, Indian and Other | 1.4 (6) | 2.6 (27) | 6.6 (53) | 10.1 (40) | 24.5 (67) | <0.001 | ||

| Education: 0-6 years | 63.3 (264) | 53.2 (548) | 48.9 (394) | 44.6 (176) | 42.5 (116) | <0.001 | ||

| Smoking: Past smoker | 8.4 (35) | 6.7 (69) | 9.7 (78) | 11.4 (45) | 8.4 (23) | |||

| Current smoker | 5.0 (21) | 6.3 (65) | 7.8 (63) | 6.3 (25) | 9.5 (26) | 0.005 | ||

| Alcohol >=once /week | 5.3 (22) | 4.1 (42) | 2.2 (18) | 5.3 (21) | 8.1 (22) | 0.143 | ||

| Physical activity score | 2.45 ± 1.91 | 2.42 ± 1.82 | 2.30 ±1.70 | 2.39 ± 1.84 | 2.43 ± 1.88 | 0.594 | ||

| Social activity score | 2.87 ± 2.30 | 3.32 ± 2.48 | 3.28 ± 2.54 | 3.30 ± 2.44 | 3.35 ±2.60 | 0.023 | ||

| Productive activity score | 3.96 ± 1.76 | 4.02 ± 1.73 | 4.05 ± 1.85 | 4.18 ± 1.82 | 4.15 ±1.92 | 0.375 | ||

| APOE-e4 ≥1 allele | 16.3 (68) | 17.6 (181) | 15.7 (126) | 15.0 (65) | 18.3 (50) | 0.901 | ||

| Central obesity | 43.2 (180) | 48.7 (502) | 52.7 (424) | 50.1 (198) | 52.7 (144) | 0.009 | ||

| Hypertension | 59.2 (247) | 59.2 (610) | 62.2 (501) | 56.7 (224) | 54.6 (149) | 0.256 | ||

| Diabetes or FBG>5.6mmol/L | 17.3 (72) | 17.8 (183) | 22.5 (181) | 19.0 (75) | 22.7 (62) | 0.032 | ||

| High triglyceride >2.2 mmol/L | 18.0 (75) | 27.6 (284) | 33.4 (269) | 21.0 (83) | 26.0 (71) | 0.167 | ||

| Low HDL-Cholesterol (<1.0mmol/L) | 18.7 (78) | 27.2 (280) | 34.7 (279) | 19.2 (76) | 29.3 (80) | 0.068 | ||

| Cardiac diseases | 8.2 (34) | 6.3 (65) | 8.2 (66) | 5.6 (22) | 8.8 (24) | 0.819 | ||

| GDS depression score | 1.58 ± 2.30 | 1.01 ± 1.94 | 0.91 ± 1.74 | 1.27 ± 2.30 | 1.33 ± 2.42 | <0.001 | ||

| GDS ≥5 | 9.8 (41) | 5.8 (60) | 3.6 (29) | 7.6 (30) | 7.7 (21) | <0.001 | ||

| MMSE | 27.3 ± 3.0 | 27.9 ± 2.5 | 28.2 ± 2.2 | 28.1 ± 2.3 | 27.8 ± 2.8 | <0.001 |

| Cognitive decline | Incident NCD | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | P | No | Yes | |||

| No. of participants | N=2489 | N=432 | N=2254 | N=192 | |||

| Never or rarely | Never or <once/year | 13.6 (339) | 18.1 (78) | 0.037 | 12.9 (291) | 22.9 (44) | <0.001 |

| Occasionally | >once/year,<once/month | 35.4 (880) | 34.8 (78) | 35.5 (801) | 35.4 (68) | ||

| Often | >once/month,<once/week | 27.9 (694) | 25.8 (150) | 28.4 (641) | 25.5 (49) | ||

| Very often | >once/week, not daily | 13.6 (338) | 13.2 (57) | 13.6 (307) | 12.0 (23) | ||

| Daily | ≥ once daily | 9.6 (238) | 8.1 (35) | 9.5 (214) | 4.2 (8) | ||

| Sex | Female | 64.3 (1601) | 70.5 (304) | 0.012 | 63.8 (1439) | 73.4 (141) | 0.008 |

| Age, years | Mean ± SD | 65.2 ± 6.9 | 67.4 ± 7.8 | <0.001 | 64.6 ±6.6 | 68.8 ± 7.9 | <0.001 |

| Non-Chinese ethnicity | Malay, Indian and Other | 6.3 (156) | 8.6 (37) | <0.001 | 5.2 (118) | 10.9 (21) | <0.001 |

| Education | 0-6 years | 49.4 (1229) | 62.4 (269) | <0.001 | 43.5 (981) | 72.4 (139) | <0.001 |

| Smoking | Past smoker | 9.0 (224) | 6.0 (26) | 0.056 | 8.6 (193) | 6.8 (13) | 0.657 |

| Current smoker | 7.0 (175) | 5.8 (25) | 7.1 (159) | 7.8 (15) | |||

| Alcohol | >=once /week | 4.3 (106) | 4.4 (19) | 0.887 | 4.5 (101) | 4.2 (8) | 0.839 |

| Physical activity score | Mean ± SD | 2.41 ± 1.81 | 2.30 ± 1.83 | 0.258 | 2.49 ± 1.82 | 2.10 ± 1.75 | 0.004 |

| Social activity score | Mean ± SD | 3.25 ± 2.47 | 3.19 ± 2.51 | 0.653 | 3.36 ±2.55 | 3.10 ± 2.06 | 0.174 |

| Productive activity score | Mean ± SD | 4.09 ± 1.80 | 3.87 ±1.80 | 0.020 | 4.16 ±1.80 | 3.94 ± 1.78 | 0.097 |

| APOE-e4 ≥1 allele | 16.6 (413) | 17.9 (77) | 0.514 | 16.1 (362) | 19.3 (37) | 0.248 | |

| Central obesity | 49.0 (1219) | 53.1 (229) | 0.111 | 48.8 (1101) | 56.8 (109) | 0.035 | |

| Hypertension | 58.3 (1452) | 64.7 (279) | 0.013 | 58.4 (1317) | 62.5 (120) | 0.271 | |

| Diabetes or FBG | >5.6mmol/L | 19.7 (490) | 19.3 (83) | 0.836 | 17.7 (400) | 25.5 (49) | 0.010 |

| High triglyceride | >2.2 mmol/L | 27.5 (685) | 22.5 (97) | 0.029 | 27.9 (628) | 21.4 (41) | 0.052 |

| Low HDL-Cholesterol | (<1.0mmol/L) | 27.6 (686) | 24.8 (107) | 0.239 | 28.0 (631) | 22.9 (44) | 0.131 |

| Cardiac diseases | 6.7 (168) | 10.0 (43) | 0.020 | 6.7 (151) | 6.3 (12) | 0.811 | |

| GDS depression score | Mean ± SD | 1.14 ± 2.05 | 1.24 ± 2.07 | 0.326 | 0.91 ± 1.67 | 1.47 ± 2.36 | <0.001 |

| GDS ≥5 | 6.1 (153) | 6.5 (28) | 0.781 | 4.2 (95) | 9.9 (19) | <0.001 | |

| MMSE | Mean ± SD | 27.8 ± 2.55 | 28.2 ± 2.35 | 0.009 | 28.7 ±1.62 | 27.2 ± 2.43 | <0.001 |

| Exposed | Cognitive decline | Unadjusted | Adjusted † | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Yes | Per 100 | OR | 95% | CI | P | OR | 95% | CI | P | ||

| Never or rarely | Never or <once/year | 417 | 78 | 18.7 | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| Occasionally | >once/year, <once/month | 1030 | 150 | 14.6 | 0.74 | 0.55, | 1.00 | 0.73 | 0.53, | 1.01 | ||

| Often | >once/month, <once/week) | 805 | 111 | 13.8 | 0.69 | 0.51, | 0.96 | * | 0.68 | 0.48, | 0.95 | * |

| Very often | >once/week, not daily) | 395 | 57 | 14.4 | 0.73 | 0.50, | 1.06 | 0.74 | 0.50, | 1.11 | ||

| Daily | ≥ once daily | 273 | 35 | 12.8 | 0.64 | 0.41, | 0.98 | * | 0.66 | 0.41, | 1.06 | |

| Linear trend, p | 0.037 | 0.150 | ||||||||||

| Exposed | NCD | Unadjusted | Adjusted † | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | MCI+dementia | Per 100 | OR | 95% | CI | P | OR | 95% | CI | P | ||

| Never or rarely | Never or <once/year | 335 | 42+2 | 13.1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| Occasionally | >once/year, <once/month | 869 | 61+7 | 7.8 | 0.56 | 0.38, | 0.84 | ** | 0.61 | 0.40, | 0.94 | * |

| Often | >once/month, <once/week) | 690 | 46+3 | 7.1 | 0.51 | 0.33, | 0.78 | ** | 0.56 | 0.35, | 0.89 | * |

| Very often | >once/week, not daily) | 330 | 20+3 | 7.0 | 0.49 | 0.29, | 0.84 | ** | 0.54 | 0.30, | 0.96 | * |

| Daily | ≥ once daily | 222 | 8 | 3.6 | 0.25 | 0.11, | 0.54 | *** | 0.21 | 0.09, | 0.49 | *** |

| Linear trend, p | <0.001 | 0.021 | ||||||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).