Submitted:

05 June 2025

Posted:

06 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

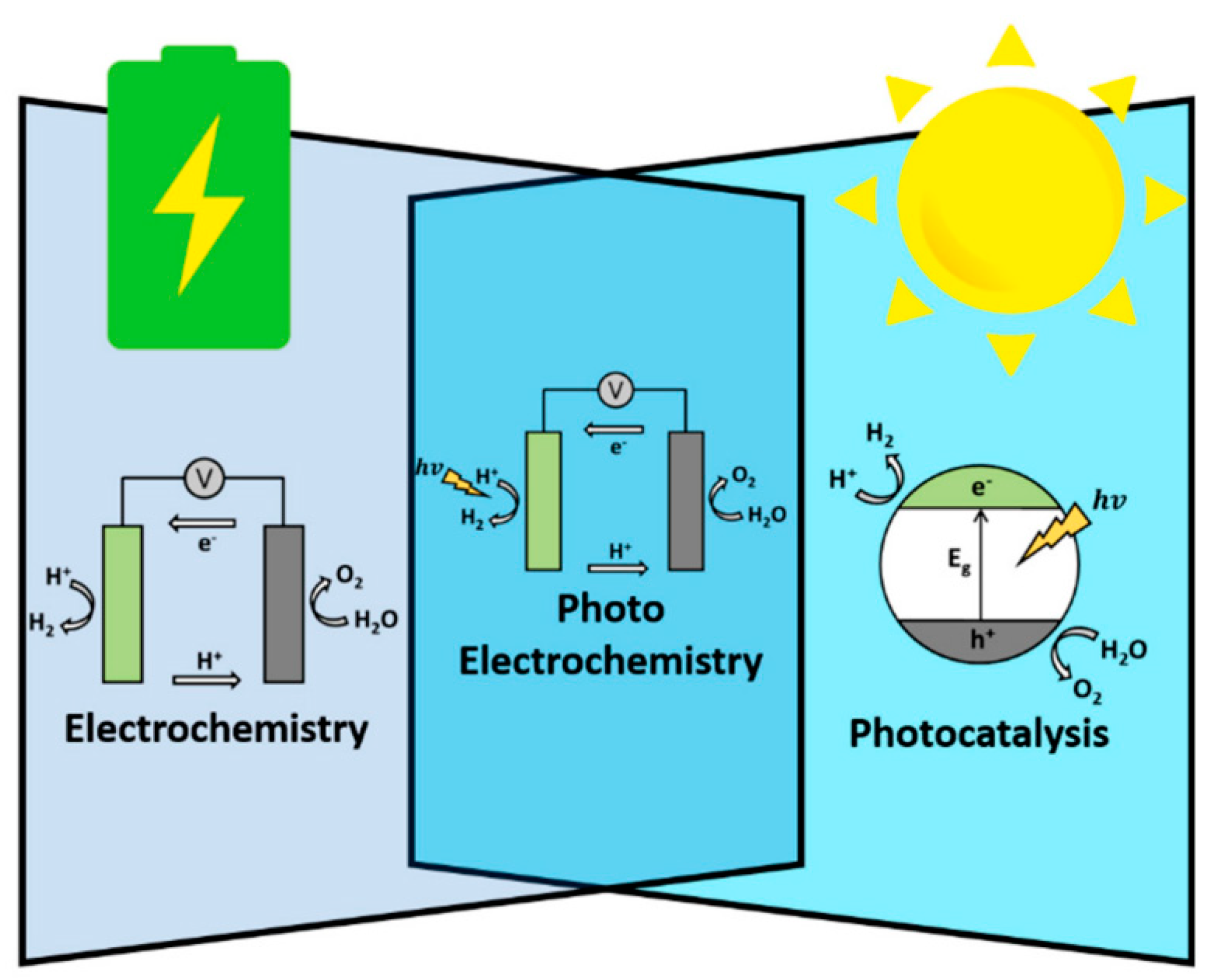

1.1. Photocatalytic Water Splitting and Its Challenges

1.2. Background of BaTiO3for Photocatalytic Water Splitting

1.3. Application of Atomistic Study of BaTiO3 Photocatalyst

1.4. Outline of Our Review

2. Main Body

2.1. DFT Calculations

| Designed systems | Methods | Main findings |

| TiO2[138] | DFT calculations using VASP with GGA-PBE functional. PAW method for ion-electron interactions (cutoff energy: 400 eV). DFT+U approach for d-electron correlation correction. FDTD method for electric field distribution simulations. |

Calculated band gap of TiO₂: 3.22 eV. Conduction band (CB) primarily composed of O(p) orbitals. Valence band (VB) primarily composed of Ti(d) orbitals. Photogenerated charge likely accumulates in these orbitals. |

| TiO2@ BaTiO3[138] | After combining with BaTiO₃, CB and VB compositions remain similar to TiO₂. Calculated band gap decreases to 1.53 eV (approximately half of TiO₂). |

|

| TiO2@ BaTiO3/ CdS [138] | Adding CdS clusters to TiO₂@BaTiO₃ caused slight crystal distortion in BaTiO₃, potentially inducing spontaneous polarization. Density of states at CB and VB formed by S(p), Ba(d), and Cd(d) orbitals. Band gap further decreased to 1.19 eV. TiO₂@BaTiO₃/CdS nanosheet exhibits an intrinsic electric field, facilitating charge separation and diffusion to the surface. |

|

| Wheat-heading BaTiO3 [139]. | DFT calculations using Materials Studio 2017 GGA-PBE functional Plane wave cutoff energy: 400 eV K-point mesh: 3 × 3 × 3 Maximum force tolerance: 0.05 eV/Å Cleaved along [001] direction Vacuum thickness of 10 Å in z-direction |

Band gap for wheat heading BaTiO3: 3.058 eV CB mainly composed of Ti 3d and O 2p orbitals VB dominated by O 2p orbitals Charge transfer from O 2p to Ti 3d After oxygen vacancy, band gap reduced to 2.717 eV VB remains dominated by O 2p orbitals CB contributions shift to O 2p, Ba 3d, and Ti 3d Enhanced charge transfer between Ti and Ovs Higher charge density improves piezo-photocatalytic performance |

| Wheat-heading BaTiO3-Oxygen Vacancy (Ovs) [139] | ||

| Pure BaTiO₃[140] | Spin-polarized DFT calculations using VASP GGA-PBE functional PAW method for core electrons Plane-wave cutoff energy: 400 eV 9 × 9 × 9 Monkhorst-Pack k-point mesh Fully optimized cubic BaTiO₃ unit cell with a lattice parameter of 4.004 Å 2 × 2 × 2 supercell (40 atoms) modeled for bulk BaTiO₃ Geometry convergence criterion: forces < 0.01 eV/Å HSE06 functional for electronic structure calculations with HF exchange fraction (α) = 0.32 |

Structural and electronic properties of BaTiO₃ were well reproduced Band gap improved with HSE06functional, aligning with experimental values Basis for further doping studies to enhance photocatalytic properties F- and N-doped BaTiO₃ (X@O) and Si-doped BaTiO₃ (X@Ti) showed negative formation energy, indicating thermodynamic stability Stability of doping systems depends on ionic radius and electronegativity of dopants relative to O or Ti C-, S-, Se-, and I-doped BaTiO₃ (X@O) extended the absorption edge into the visible light region, enhancing photocatalytic water splitting capabilities S- and Se-doped BaTiO₃ (X@Ti) exhibited potential for water splitting under visible light Doping-induced modifications improved both photo-oxidation and photo-reduction properties of BaTiO₃ Key Findings for X@O Doping Band gap (Eg) range: 1.93 eV (C) – 3.31 eV (Si, P, F) Highest CBM: F-doped BaTiO₃ (-3.82 eV) Lowest CBM: Si-doped BaTiO₃ (-3.03 eV) Electronegativity (χ) range: 4.68 (Si) – 5.47 (F) Photocatalytic potential: C-, S-, Se-, and I-doped BaTiO₃ extend absorption into the visible region, enhancing photocatalytic efficiency. Key Findings for X@Ti Doping Band gap (Eg) range: 0.84 eV (Cl) – 3.31 eV (F) Narrowest band gap: Cl-doped BaTiO₃ (Eg = 0.84 eV), due to low CBM (-5.69 eV) and VBM (-6.53 eV) Highest CBM: Si-doped BaTiO₃ (-3.89 eV) Highest VBM: Br-doped BaTiO₃ (-7.47 eV) Electronegativity generally higher for X@Ti systems compared to X@O, resulting in distinct electronic structure modifications. |

| Non-metal-doped BaTiO₃ (X@O or X@Ti, X = C, Si, N, P, S, Se, F, Cl, Br, I) [140] | DFT calculations with VASP 3 × 3 × 3 k-point mesh for geometry optimization and electronic properties Substituting O or Ti with non-metal dopants at a doping concentration of 2.5 at.% HSE06 functional used for accurate band gap calculations |

|

| Pure BaTiO₃[141] La-doped BaTiO₃[141] |

CASTEP program in Materials Studio DFT with plane-wave pseudopotential method GGA-PBE functional Birch-Murnaghan equation of state for lattice optimization Cut-off energy: 340 eV |

BaTiO₃ exists in a cubic structure (Pm3m) with Ba at corners, Ti at the body center, and O at face centers. The calculated lattice constant is 4.034 Å, closely matching experimental values. Optical properties such as dielectric function, absorption, and refractive index are analyzed. |

| La doping at Ba sites reduces the lattice parameter (a = 3.971 Å) and unit cell volume. The band structure changes from an indirect to a direct band gap, reducing the gap to 1.569 eV. This shift enhances conductivity by facilitating electron-hole recombination. The La-5d states contribute significantly to the conduction band. Optical properties, including dielectric function, absorption, and refractive index, are modified. | ||

| BaTiO₃ with Ba and Ti vacancy [142] | Modeled using Materials Studio Optimized structure using VASP First-principles calculations based on DFT framework 2 × 2 × 2 crystal structure containing 8 Ba, 24 O, and 8 Ti atoms PAW and PBE methods used for structure optimization and charge density calculations |

Lattice distortion occurs due to Ba and Ti vacancies, affecting oxygen coordination and Coulomb repulsion. Oxygen vacancies are necessary for charge conservation in the system. Lattice expansion and distortion due to Ti and O vacancies are significantly higher than those caused by Ba and O vacancies. Charge density changes: • Ba and O vacancies decrease charge density in specific regions of the unit cell. • Ti vacancy increases and homogenizes charge density at the vacancy position. Lattice deformation leads to internal atomic shifts, with Ti atoms moving away from symmetry centers. |

| Pure BaTiO₃ (BTO) [143] Mo-doped BTO (2.5 at%) [143] |

First-principles calculations using DFT with the supercell approach, performed using VASP. Functional: Generalized Gradient Approximation (GGA) for the projector-augmented wave (PAW) method. Structural Model: Cubic 1×1×1 BTO unit cell. Plane-wave energy cutoff: 500 eV. k-point sampling: Monkhorst-Pack grid of 7×7×7. |

The calculated bandgap of pure BTO is 1.56 eV, which is underestimated due to DFT limitations. Charge-density analysis confirms covalent Ti–O bonding. Mo doping narrows the bandgap to 1.27 eV due to impurity levels formed by Ti 3d and Mo 3d interactions. Mo–O bonding results in a more uniform charge distribution than pure BTO. |

| Pure BaTiO₃ [144] Cs-doped BaTiO₃ (0.13%, 0.26%, 0.39%) [144] |

• CASTEP code used for geometry optimization and property investigation. • GGA-PBE exchange correlation functional with DFT+U correction (U = 4 for Ti-d orbital). • Plane-wave pseudopotential technique based on DFT. • Vanderbilt-type ultrasoft pseudopotentials for electron–ion interactions. • BFGS energy minimization for electronic wave functions and charge densities. • Pulay density mixing scheme applied. • Monkhorst–Pack method for k-point sampling (6×6×6 k-points mesh). • Energy cutoff = 630 eV. • Total energy difference per atom: 2 × 10⁵ eV. • Max ionic displacement: 2 × 10³ Å. • Cubic phase (Pm3m, 221) chosen. |

Pure BaTiO₃ Indirect band gap: 2.513 eV (higher than previous theoretical value of 1.719 eV but closer to experimental results). The difference is due to DFT+U correction, as earlier studies used only PBE-GGA. TDOS maximum peak at 4.29 eV (6.58 value), with other peaks at 1.79 eV and 0.95 eV. Phonon spectra show no imaginary frequencies, confirming stability. |

| For Cs-doped BaTiO₃ (0.13%, 0.26%, 0.39%) Band gap converts from indirect to direct upon Cs doping. 0.13% Cs: 1.858 eV (direct band gap). 0.26% Cs: 2.103 eV (direct band gap). 0.39% Cs: 1.882 eV (direct band gap). TDOS of 0.13% Cs-doped BaTiO₃ shows enhanced peaks, with a maximum peak at 0.77 eV (57.46 value). New peaks in TDOS appear at 3.43, 2.37, 2.40, 3.36, and 4.47 eV. Phonon spectra confirm stability for 0.13% Cs-doped BaTiO₃ (no imaginary frequencies detected). | ||

| BaTiO3(111) surfaces with different terminations [145] | DFT calculations using VASP PAW method for core electrons Plane-wave basis with 400 eV cutoff DFT+U approach with PBE functional (Ueff = 4.0 eV for Ti 3d) Conjugated gradient geometry optimization 6×6×1 Monkhorst-Pack k-point sampling Dipole correction applied Slab model with 13 atomic layers (7 fixed, 6 relaxed) and 15 Å vacuum gap Considered stoichiometric (BaO3, Ti) and non-stoichiometric (BaO2, BaO, Ba, O3, O2, O) terminations |

Surface energy and stability BaO2 and O terminations have the lowest cleavage energies, making them the most thermodynamically stable. Removal of oxygen, Ti, or Ba reduces cleavage energy, stabilizing polar surfaces. Excess Ba (BaO +O2) or oxygen (Ba +O3) leads to instability with higher cleavage energies. Phase diagram analysis (SGP method) BaO2 and O terminations dominate under wide O- and Ba-rich conditions. Stoichiometric BaO3 and Ti terminations are stable only in limited conditions. Results from O-Ti phase diagram match O-Ba phase diagram, confirming BaO2 and O as the most stable. Charge compensation mechanism Bader charge analysis shows charge redistribution in surface layers to compensate dipole moments. |

| BaTiO3 doped with chalcogens (S, Se, Te) under different concentrations [146] | DFT calculations using WIEN2K package with FP-LAPW method and LDA+mBJ exchange-correlation potential Calculation of ε(ω) = ε1(ω) + iε2(ω) |

BaTiO3 has a cubic Pm3m structure. Lattice constant (a0 = 3.9412 Å) agrees with experimental (4.0000 Å) and theoretical values. The forbidden band gap decreases with increasing chalcogen concentration due to electronegativity differences. Doping reduces the band gap significantly (Eg reduction from 2.901 eV to 0 eV in some cases). Strong hybridization occurs between O-2p and chalcogen-p orbitals. |

| Pressed BaTiO3 (2.3% axial compressive strain)[147] Barium Titanate under triaxial compressive strain [147] |

- Ab initio calculations based on DFT using FP-LAPW method (WIEN2K package) - Exchange correlation potential: LDA + mBJ - Thermoelectric properties: BoltzTraP code - Brillouin zone integration: 6×6×6 k-points for electronic and optical properties, 10×10×10 for thermoelectric properties - Structural optimization: Comparison with experimental and theoretical results |

Lattice constant reduced to ap = 3.8505 Å. Pressed BaTiO3 exhibits a direct bandgap at the Γ point, unlike pure BaTiO3, which has an indirect bandgap. Further band gap reduction compared to non-pressed doped structures. Pressed BaTiO3 exhibits slightly higher optical property peaks in ε1(ω) and ε2(ω) compared to pure BaTiO3. |

| Electronic properties: Pure BaTiO3 is a semiconductor with an indirect band gap (2.901 eV for cubic, 2.922 eV for tetragonal phase) Under ξ = 2.3% compressive strain, BaTiO3 transitions to a direct band gap semiconductor, improving potential for photovoltaic applications Density of States analysis confirms VB is mainly O-2p, while CB is Ti-3d Band gap increases with strain, indicating possible piezoelectric properties | ||

| BaTiO₃ (001) surfaces doped with metal and nonmetal elements [148] | DFT calculations using VASP, PBE functional under GGA, and HSE06 hybrid functional. Plane-wave cutoff energy: 400 eV. k-point mesh: 9×9×9 for bulk optimization and 3×3×1 for surface calculations. | The tetragonal BaTiO₃ unit cell was fully optimized, with lattice parameters a = b = 3.992 Å, c = 4.056 Å, matching experimental and theoretical results. BaTiO₃ (001) surface modeled with TiO₂- and BaO- terminations. Symmetric slabs (odd atomic layers) were adopted due to the absence of macroscopic dipole moments. Co-doped systems (M+X) are more stable when M and X are adjacent due to M-X bond formation. Formation energies indicate that O substitution by C or N is easier under Ti-rich conditions, while Ti substitution by metal dopants is favored under O-rich conditions. Binding energy calculations show that co-doped systems are more stable than mono-doped systems. The computed bandgap of bulk BaTiO₃ is 3.03 eV, while the pure BaTiO₃ (001) surface has a bandgap of 1.42 eV. Passivated co-doping (e.g., V+N, Nb+N, Ta+N) introduces charge compensation, eliminating mid-gap states. The Ta+N co-doping system leads to the most significant bandgap narrowing (1.09 eV) due to the upshift of the valence band maximum. |

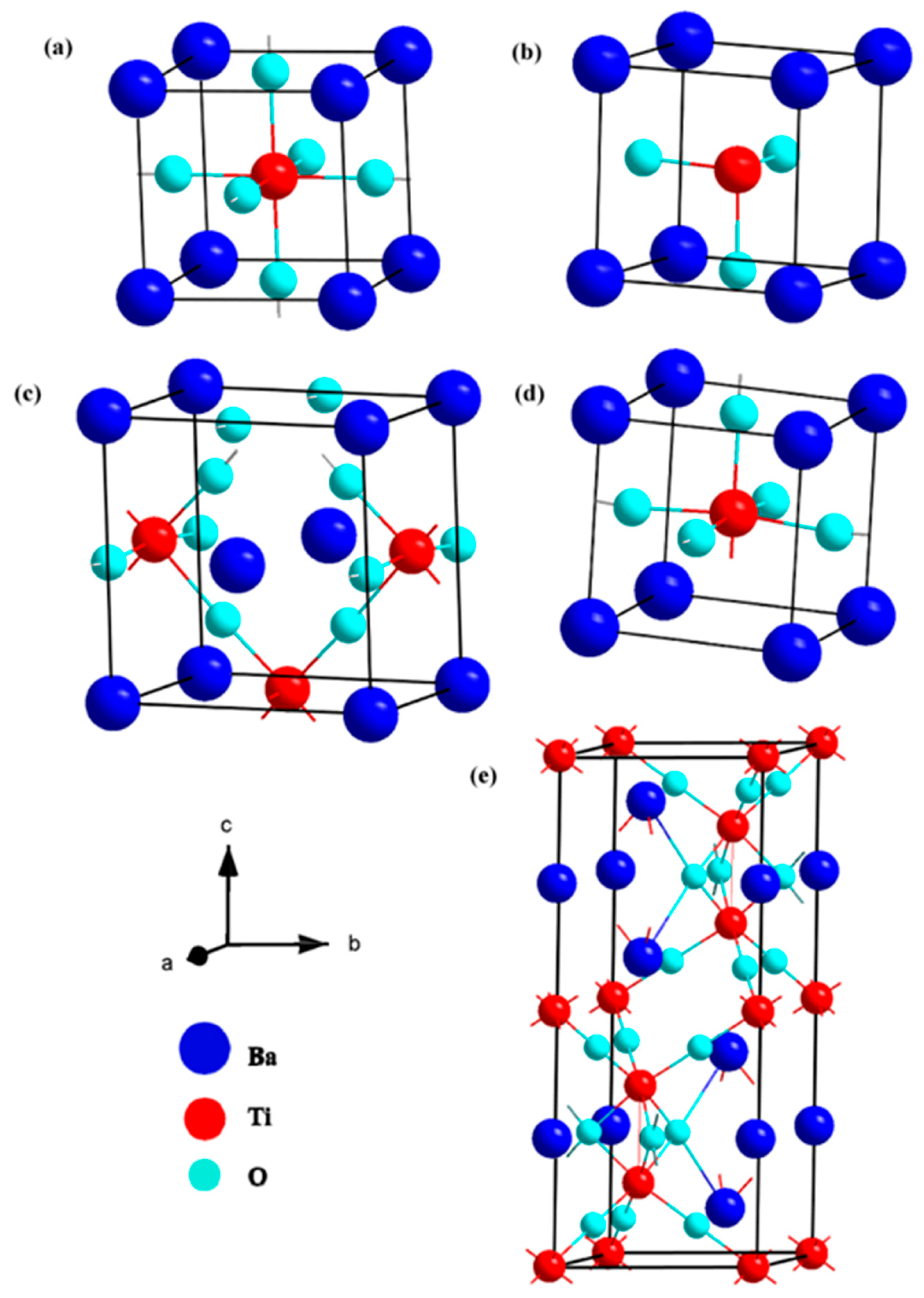

| BaTiO₃ polymorphs (Cubic, Rhombohedral, Orthorhombic, Tetragonal, Hexagonal) [149] | First-principles calculations using CASTEP within DFT framework (GGA-PBE, LDA, and HSE06 functionals) | Optimized lattice parameters are consistent with theoretical and experimental results. Formation enthalpies indicate all phases are energetically stable, with cubic phase being the most stable. Band structure analysis shows indirect bandgaps for four phases and a direct bandgap for the hexagonal phase. GGA-PBE and LDA underestimate bandgaps, while HSE06 gives values closer to experimental data. Higher electron mobility and conductivity inferred from band structure analysis. Density of states analysis confirms structural stability and electrical conductivity. |

| BaTiO₃, PGBT [150] BaTiO₃, PG, PGBT [150] |

Electronic structure and density of states calculations using Quantum ESPRESSO with PBE pseudopotentials - k-mesh: 9 × 9 × 1 for self-consistent field (scf) and 18 × 18 × 1 for non-self-consistent field calculations. - Energy cutoff: 90 Ry for wavefunctions, 740 Ry for charge density. |

Redshift in absorption edges of PGBT compared to pure BaTiO₃. Bandgap energies (Tauc method): BaTiO₃ (3.12 eV), PGBT (2.95–2.79 eV, decreasing with increasing PG content). Lower fluorescence intensity indicates reduced charge carrier recombination, enhancing photocatalytic efficiency. Electron migration from BaTiO₃ to PG via Ba–C bond supports charge separation. Beyond 7.5 PGBT, fluorescence intensity increases due to excess PG acting as a recombination center. |

| Fully relaxed 5 × 5 × 1 supercell of PGBT with a 12 Å vacuum to prevent interaction between composites. Estimated bandgap of 1.74 eV (indirect, R to Γ), lower due to DFT underestimation. Additional bandgaps observed: direct at Γ, indirect from M to Γ. BaTiO₃: VB primarily from O ‘p’ states; CB dominated by Ti ‘p’ states with minor O ‘p’ contributions. | ||

| Ba₁₋ₓGaₓTiO₃ (x = 50%) [151] | DFT simulations using WIEN2k Tetra-elastic package for elastic properties Ba₁₋ₓGaₓTiO₃ was studied using full-potential linearized augmented plane wave (FP-LAPW) method. A 2000 k-point mesh was used for Brillouin zone integration. Band structure and density of states were analyzed for electronic properties. Elastic coefficients were calculated usingEulerian strain approach. The unit cell structure was modeled with tetragonal symmetry. |

Pristine BaTiO₃ exhibits an indirect band gap of 2.65 eV. Ga substitution reduces the band gap to 1.84 eV for the majority spin channel. The minority spin channel exhibits metallic behavior with a half-metallic gap of 0.59 eV. Partial density of states analysis shows significant contributions from O-p, Ti-d, and Ga-p states. Dielectric constant (ε₁(0)) increased from 8.8 (pure) to 100 (Ga-doped). A peak in the imaginary dielectric function ε₂(ω) at 3.9 eV corresponds to O-p electron transitions to the conduction band. Ga doping shifts absorption peaks towards the visible and infrared regions, enhancing optical activity. |

| t-BTO@NiFe-LDH heterojunctions [152] | First-principles DFT calculations within GGA using PBE functional PAW potentials for ionic cores Plane wave basis set with 450 eV cutoff Gaussian smearing (0.05 eV) Self-consistent energy threshold: 10⁻⁶ eV Geometry optimization convergence: 0.05 eV/Å 2 × 2 × 1 Monkhorst-Pack k-point sampling Adsorption energy (E_ads) and free energy (G) calculations |

Formation of t-BTO@NiFe-LDH heterojunctions increased Ni³⁺ content (45% → 68% for NiFe LDH, 61% → 83% for t-BTO@NiFe-LDH) after OER test. Fe³⁺/Fe²⁺ ratio increased slightly after OER test, improving OER electrocatalytic activity. Free energy calculation showed a lower rate-determining step (RDS) energy for t-BTO@NiFe-LDH (1.52 eV for Ni site, 1.76 eV for Fe site) compared to NiFe-LDH. Bandgap of t-BTO@NiFe-LDH (0.42 eV) was lower than NiFe-LDH (0.95 eV) and t-BTO (2.37 eV), indicating enhanced electronic conductivity. Charge density difference analysis showed electron transfer from NiFe-LDH to t-BTO, improving OER activity. d-band center shifted from 3.89 eV (NiFe-LDH) to 2.98 eV (t-BTO@NiFe-LDH), favoring adsorption of OER intermediates. Enhanced electron movement near Ti atoms improved spontaneous polarization of t-BTO. |

| BTO, BTPO-0.09, BTPOv-0.09 [153] | DFT using VASP PBE exchange-correlation function PAW pseudopotentials Cutoff energy: 520 eV Monkhorst-Pack 2×2×1 k-points for Brillouin zone sampling DFT-D3 for vdW interactions Geometry optimization criteria: 1.0×10⁻⁵ eV/atom (energy), 0.01 eV/Å (force) UV-Vis diffuse reflectance spectroscopy UV photoelectron spectroscopy Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy XANES and XPS for charge distribution analysis |

The bandgaps of synthesized materials (3.24 eV, 3.20 eV, and 3.13 eV) are close to theoretical values, confirming minimal influence from PtOx loading. Pt-O-Ti³⁺ sites act as defect energy levels and oxidation sites. Charge density analysis revealed electron accumulation around PtOx and depletion around Ti atoms, matching XANES and XPS results. Polarization studies showed improved current response for PtOx-loaded samples, confirming enhanced photocatalytic activity. Pt serves as an electron aggregation center, accelerating proton reduction for H₂ production. Oxygen vacancies facilitate charge aggregation, and Ti³⁺ defects enhance rapid electron transfer. The defect energy level at Pt-O-Ti³⁺ sites allows efficient separation of electrons and holes, leading to an effective bifunctional catalytic system. |

| BaTiO₃/SrTiO₃ [154] |

First-principles calculations using DFT-D3 VASP Generalized-Gradient Approximation (GGA) with PBE functional Kinetic cutoff energy: 520 eV Brillouin zone sampling: 5×5×1 Monkhorst-Pack mesh External electrostatic field along [001] direction (E = 0.1 eV/Å) Band structure and density of statescalculations Gibbs free-energy change (ΔG_H*) calculations for hydrogen adsorption Visualization with VESTA software |

The BaTiO₃/SrTiO₃ heterojunction has a lower bandgap (1.1 eV) compared to individual SrTiO₃ (2.31 eV) and BaTiO₃ (2.15 eV), promoting photocatalytic efficiency. Application of an external electric field further narrows the bandgap to 1.0 eV, enhancing electron transport and energy band bending. Differential charge density analysis reveals efficient electron transfer from BaTiO₃ to SrTiO₃ at the heterostructure interface. Hydrogen adsorption Gibbs free energy (ΔG_H*) shows SrTiO₃ (0.57 eV), BaTiO₃ (-1.01 eV), and BaTiO₃/SrTiO₃ (-0.42 eV), indicating BaTiO₃/SrTiO₃has optimized adsorption-desorption balance. |

| Zr+X codoped BaTiO₃ systems [155] | DFT calculations SCAN functional for structural and energetic properties TB-mBJ functional for electronic and optical properties Full-potential linearized augmented plane wave (FP-LAPW) method using WIEN2k package 2×2×2 supercell approach for constructing doped and codoped systems k-mesh: 12×12×12 for bulk, 6×6×6 for supercell |

Structural and Thermodynamic Properties: SCAN functional accurately predicts lattice parameters and cohesive energies. The computed cohesive energies of S, Se, and Te match well with previous studies. Electronic Properties: TB-mBJ functional predicts larger band gaps than SCAN functional. X-doped systems (BTOX) have valence band edges composed of O-2p states with contributions from X-p states. Zr-doped system (BTZO) shows conduction band modifications due to Zr-4d states. Zr+X codoping (BTZOX) leads to a reduced band gap, making them promising for visible-light applications. |

| MO/BTO Heterostructures (ZnO/BTO, TiO2/BTO, SnO2/BTO) [156] | DFT using QuantumEspresso GGA for exchange-correlation functional Plane wave basis (320 Ry cut-off) k-point meshes: 6×6×1 for integration, 12×12×1 for density of states Marzari-Vanderbilt cold smearing (0.05 Ry) Fully relativistic norm-conserving pseudopotentials van der Waals corrections included DFT+U for accurate band gap predictions Charge carrier effective masses calculated from Bloch band curvature Structural relaxations using BFGS algorithm |

Structural Properties: ZnO/BTO shows a decrease in BTO lattice vector c due to interface-induced tetragonality enhancement. Interface distances: ZnO/BTO (2 Å), TiO2/BTO and SnO2/BTO (4 Å). ZnO mid-slab oxygen layers exhibit large displacements due to interface interactions. Lattice mismatch effects cause strain in BTO, compressing c in ZnO/BTO. Electronic Properties: Band gaps in bulk: BaTiO3 (3.28 eV), ZnO (3.41 eV), TiO2 (3.17 eV), SnO2 (3.52 eV). Interface effects modify band structures, introducing metal-induced gap states in ZnO/BTO. ZnO/BTO exhibits highly dispersive bands due to stronger interface interaction. TiO2/BTO shows a single dispersive surface state, SnO2/BTO retains bulk-like band structure. BTO and SnO2 maintain their direct semiconducting nature in HS form. |

| Rhombohedral BaTiO₃ (BaTiO₃ (001) surface, pure and Rh-doped) [157] | Ab initio plane-wave calculations using VASP with PAW formalism and PBE-GGA exchange-correlation functional. Solvation effects modeled using VASPsol. Monkhorst–Pack grid: 2×2×2 for bulk, 2×2×1 for slab. Cutoff energy: 520 eV. Convergence tolerance: 10⁻⁶ eV. Slab models with 7 alternating TiO₂- and BaO-planes and 13 Å vacuum gap. Rh doping effects analyzed by replacing Ti with Rh and re-optimizing structures. |

Rhombohedral BaTiO₃ is ferroelectric and stable below 90°C. Structural calculations show good agreement with experimental and previous theoretical studies. Ti displacement (-0.0137 Å) and O displacement (0.0232 Å) along [111] in rhombohedral BaTiO₃. Calculated Ba–O (2.87 Å) and Ti–O (1.89 Å) bond lengths match experimental data. Direct bandgap of 2.25 eV is consistent with previous theoretical studies, though underestimated by GGA-PBE. BaTiO₃ (001) surface (TiO₂-terminated) is nonpolar with a vacuum gap of 13 Å in slab models. Rh doping (substituting Ti with Rh) slightly affects lattice structure; minimal bond length change observed. Effective charge of Rh (1.66e) is lower than Ba (2.55e). Rh doping reduces the bandgap from 1.45 eV to 0.67 eV and introduces an in-bandgap acceptor level (0.115 eV above Fermi level). Rh and O hybridized orbitals create defect states in the bandgap, influencing photocatalytic performance. |

| BaTiO₃/LaAlO₃ heterostructures [158] | DFT calculations using Quantum Espresso Norm-conserving pseudopotentials GGA-PBE functional for exchange-correlation Monkhorst-Pack k-point grid (10×10×1 for heterostructure, 12×12×1 for bulk) 30 Å vacuum space with dipole correction DFT-D3(BJ) for van der Waals interactions Plane-wave cut-off energy: 45 Ry Slab model for surface and interface calculations Geometry optimization using the BFGS scheme Self-consistent field iteration convergence: 10⁻⁶ Ry Hybrid HSE06 functional for electronic structure calculations |

Optimized lattice parameters of bulk LaAlO₃ (3.83 Å) and BaTiO₃ (3.97 Å) agree with experimental values. Small lattice mismatch (-3.16%) in Conf(001) heterostructure allows epitaxial growth. Lattice mismatch in Conf(011) and Conf(111) was reduced using supercell stacking. Ab initio MD and phonon dispersion results confirm dynamic and thermal stability of BaTiO₃/LaAlO₃(001) heterostructures at 300 K. BaTiO₃(001) surface has the lowest bandgap (3.44 eV), favoring higher photocatalytic performance. BaTiO₃(011) and (111) surfaces show direct bandgap behavior (4.05 eV, 3.75 eV). Conf(111) heterostructure has an indirect bandgap (1.59 eV), while Conf(011) and Conf(111) show direct bandgap (2.21 eV, 1.75 eV), making them promising for visible-light photocatalysis. PDOS analysis reveals that charge carrier separation efficiency is influenced by surface composition. |

| BaTiO₃ thin films with TiO₂- and BaO-terminated slabs for electrocatalysis [159] | Ab initio periodic DFT+U calculations using the Quantum Espresso package, with GGA+U approximation and ultrasoft pseudopotentials. U = 4 eV for Ti d states. Kinetic energy cutoff: 320 eV. K-point grids: 4 × 4 × 1. Slabs modeled with four BaO and four TiO₂ layers on Pt as an electron reservoir. Binding free energy calculations performed for HER mechanism. |

Polarization direction affects electronic structure: Upward polarization → Electron-rich surface (downward band bending, Ti d states near Fermi level). Downward polarization → Hole-doped surface (upward band bending, O p states near Fermi level). Surface energy calculations: TiO₂-terminated slabs are the most stable. HER activity trends: Poled-up surfaces show smaller reaction barriers for HER, making them more favorable. Only H adsorption on O site of poled-down surface has an optimal |

| Up-poled and Down-poled BFO/BVO heterostructures [160] | DFT calculations using CRYSTAL23 code with B3LYP functional, D3 dispersion corrections, and spin polarization. Basis sets: pob-TZVP-Rev2. Slabs modeled in R3c space group with (110) surface exposed. | Up-poled BFO surface: Spontaneously dissociates water molecules, converting surface O to OH. Oxygen vacancies migrate to the surface under upward polarization, enhancing OH adsorption. XPS spectra: OL-H peak intensity increases, OL peak weakens and broadens with blue shift due to electron transfer to BVO. Stronger interaction with water compared to down-poled BFO, enhancing OW-C and OW-P peaks. Binds molecular oxygen more strongly, which may slow reaction rate. Down-poled BFO surface: H+ adsorption promotes surface OH formation, enhancing OL-H peak. OL and OL-H peaks shift to higher binding energies due to ferroelectric polarization effects. Weaker interaction with water, dominated by physisorption, leading to weaker OW-C peak and stronger OW-P peak. More fluid interaction with water and easier oxygen desorption, improving reaction rate. pH significantly affects BFO-water interactions due to availability of H+/OH−. |

| Anionic mono- and co-doped BaTiO₃[161] | QuantumATK software package DFT with PBE-GGA Norm-conserving PseudoDojo pseudopotential Self-consistent field simulations (10⁻⁸ Ha tolerance LBFGS geometry optimization Monkhorst–Pack k-grid for Brillouin Zone integration HSE06 hybrid density functional for electronic calculations 2×2×2 supercell approach with periodic boundary conditions |

Lattice constants of mono-doped and co-doped BaTiO₃ structures decrease due to incorporation of anionic elements. Formation energy calculations indicate anionic co-doping is more stable than mono-doping, especially in O-poor conditions. N-doping introduces asymmetrical density of state, leading to magnetic behavior (+1.0 μB). P-doping also induces magnetism (+1.0 μB) and localized states near the Fermi level. C-doping introduces two acceptor levels, with a strong magnetic moment (+2.002 μB). S-doping maintains valence electron count, interacting with Ti 3d states and resulting in a favorable band gap (2.24 eV) for visible light absorption. Co-doped systems (e.g., N-N, C-S, N-P) exhibit lower formation energies than their mono-doped counterparts, making them more thermodynamically favorable. N-N co-doping is the most stable due to similar atomic radii and strong anionic interactions. |

| Ir-doped BaTiO₃ [162] | DFT calculations usingVASP Projector Augmented Wave (PAW) method Generalized Gradient Approximation (GGA) with Perdew−Burke−Ernzerhof (PBE) functional GGA+U method (U values: Ti = 4 eV, O = 8 eV, Ir = 2 eV) Self-consistent and non-self-consistent field calculations with Monkhorst−Pack k-point grids (3×3×3 and 7×7×7) Cutoff energy: 500 eV Structural relaxation criteria: Total energy convergence at 10⁻⁶ eV, residual atomic force <0.01 eV/Å Analysis of Density of States and Fermi-level shifts |

Ir doping at the Ti site in BTO induces a transition from n-type to p-type conductivity. DOS calculations reveal a substantial downward shift in the Fermi level (from 4.36 eV to 3.18 eV), confirming p-type behavior. Ir doping at the Ba site does not induce a similar Fermi-level shift. DOS analysis indicates partially and fully occupied Ir 5d orbitals below and above the Fermi level. Charge neutrality is maintained by Ir³⁺ to Ir⁴⁺ transitions, contributing to hole formation and p-type behavior. Findings align with previous studies on Rh-doped SrTiO₃. Ir-doped BTO exhibits visible-light absorption, making it a promising material for optoelectronic and photocatalytic applications. urther investigations on solar hydrogen evolution activity are in progress. |

| Rh-doped BaTiO3 (Case A: Rh at Ba and Ti sites) [163] | - First-principles DFT calculations using Quantum ESPRESSO - PW functional with LDA pseudopotential - Norm-conserving pseudopotential with valence electrons: 6s² (Ba), 3d²4s² (Ti), 2s²2p⁴ (O) - Plane wave cutoff: 120 Ry, charge density cutoff: 480 Ry - k-point mesh: 4×4×4 (SCF), 8×8×8 (NSCF) - Electronic structure along G-X-M-G-R-X path |

BaTiO₃ has a cubic perovskite structure Direct bandgap of 1.929 eV at G point due to folding of R point onto G point in 2×2×2 supercell Additional indirect bandgap transitions (R → G and M → G) Underestimation of bandgap in DFT due to derivative discontinuities Valence band formed by O p-orbitals, conduction band formed by Ti d-orbitals Ba atoms have an ionic nature and do not contribute significantly to pDOS Rh-doped BaTiO3 (Case A: Rh at Ba and Ti sites) Formation of acceptor level within the bandgap (width: 0.167 eV above Fermi level) Reduction of bandgap to 0.673 eV Acceptor level formed due to hybridization of Rh (Ba site) d-orbitals and O p-orbitals Large gap (1.032 eV) between valence band and acceptor level increases recombination center lifetime Deep defect states observed in wavefunction analysis Direct bandgap: 2.028 eV at G point Indirect bandgap: 1.796 eV (X → G) due to defect band overlapping with valence band edge Hybridization of O p-orbitals and Rh d-orbitals at defect band region Rh-doped BaTiO3 (Case C: Rh at Ba sites only) Formation of donor level (width: 0.363 eV) 0.148 eV above valence band edge Reduction of bandgap to 1.525 eV (lowest among cases) Valence band mainly from O p-orbitals, with hybridization with Rh d-orbitals Minor Rh d-orbital contributions in conduction band Single occupancy ensures continuous band structure, facilitating charge carrier migration |

| BaTiO₃ surfaces with different polarization states for hydrogen evolution reaction [164] | First-principles calculations using VASP 5.4.4 with GGA-PBE functional and DFT-D3 dispersion correction | The tetragonal phase of BTO was used, as it is stable at room temperature where HER occurs. GGA was chosen due to limitations of LDA for hydrogen-bonded ferroelectrics. Lattice constants were fixed to experimental values. The calculated polarization of BTO bulk (30.23 μC/cm²) is close to experimental (∼26 μC/cm²), and U_eff = 6 eV improves accuracy. Surface structure relaxation leads to rumpling, affecting adsorption behavior. For out-of-plane polarized BTO, the most stable hydrogen adsorption site is the surface oxygen site. The surface titanium site is inactive for HER. In-plane polarization states can be modulated via thin-film growth techniques and electrochemical poling. A switchable HER catalysis mechanism is proposed, where mechanical strain can modulate BTO polarization states, affecting hydrogen adsorption. |

| La-N@B co-doped BaTiO3 [165] | DFT computations using CASTEP in Material Studio PBE exchange-correlation functional with GGA + U (U = 4.3 eV for Ti-3d, 8.1 eV for La-4f) Energy cutoff: 500 eV k-point grid: 3 × 3 × 3 Ultra-soft pseudopotentials Energy convergence: 1.0 × 10⁻⁵ eV/atom Structural relaxation: Max force = 3.0 × 10⁻² eV/Å, Max stress = 5.0 × 10⁻² GPa, Max atomic displacement = 1.0 × 10⁻³ Å |

La and N mono-doping effects: La substitution at the Ba site reduced the bandgap to 1.55 eV La substitution at the Ti site caused a slight bandgap increase (+0.10 eV) N substitution at O sites lowered the bandgap to 1.23 eV Co-doping impact (La-N@B, 25%): Band edge positions were more favorable for photocatalytic water decomposition Modulated electronic structure and optimized bandgap for improved absorption properties PDOS and TDOS analysis revealed Ti-3d and O-2p as dominant contributors to the conduction band minimum (CBM) and valence band maximum (VBM) - The cubic BaTiO3 phase (Pm3m) was used as a structural model despite its high-temperature stability for computational feasibility |

| [57] Tetragonal BaTiO3 with (001) TiO2- and BaO-terminated surfaces | DFT calculations using HSE06 functional Geometry optimization and substitution energy calculations Density of States and optical absorption analysis |

Modeled BaTiO3 (001) surfaces with TiO2- and BaO-terminated slabs. Rh doping of Ba/Ti sites prevents dipole moments due to symmetry preservation. BaO-terminated surfaces found to be unstable under operating conditions. Substitution of Ti4+ with Rh4+ slightly distorts the lattice, while Ba2+ → Rh3+ + OH− substitution leads to significant structural changes. Doping the TiO2-terminated surface with Rh4+ introduces Rh-4d states in the band gap, reducing its value. Optical absorption threshold shifts due to Rh4+ doping, with DOS analysis confirming band gap modifications. |

| [166] Pt-doped BaTiO₃ | First-principles calculations using the supercell method, DFT with GGA-PW91, CASTEP, PAW approach, Energy cutoff: 300 eV, Monkhorst-Pack k-mesh (4×4×4), Scissor operator (0.75 eV) applied | Optimized BaTiO₃ unit cell and constructed 2×2×2 supercell (40 atoms). Pt doping at Ba and Ti sites (0.125 ratio) slightly reduces stability but remains thermodynamically favorable. Bandgap reduction observed: 1.78 eV (Ba site) and 2.06 eV (Ti site), indicating semiconducting behavior. Strong hybridization between Pt–5d and O–2p states. Mulliken charge analysis shows increased charge redistribution around O atoms. Pt doping introduces ferromagnetism in BaTiO₃. Charge density analysis confirms the ionic-covalent bonding nature. |

| BaTiO3/Cu2O heterojunction [167] | Quantum Espresso package DFT Generalized Gradient Approximation (GGA) using PBE functional Ultrasoft pseudopotentials Plane-wave basis set (30 Ry energy cutoff, 180 Ry charge density cutoff) Monkhorst-pack mesh for Brillouin zone sampling Structural optimization via Hellman-Feynman forces |

Band alignment and offsets were calculated using supercell periodic slab models BaTiO3/Cu2O interface shows a staggered (Type-II) band alignment, which favors charge separation and enhances photoelectrochemical activity Band offset values were obtained by considering valence band (Ev) and conduction band (Ec) discontinuities Effective mass of electrons and holes was calculated, revealing that Cu2O has a lower electron effective mass, indicating higher carrier mobility The interface has a built-in dipole due to electronic charge transfer, influencing potential shifts across the heterojunction |

| [169] BaTiO3 (BTO) (001) surfaces, including perfect and oxygen-deficient (TiO2-terminated) surfaces | DFT with DFT+U using the VASP | PBE+U(Ti,O) approach improves the accuracy of band gap calculations and bond energy predictions compared to standard PBE and PBE+U(Ti). Oxygen vacancies (Ovac) introduce in-gap states with Ti-3d character, positioned ~1.0 eV above the valence band maximum (VBM) and ~0.8 eV below the conduction band minimum (CBM). The stability of BaO- and TiO2-terminated surfaces depends on temperature: BaO is more stable at 0K, but TiO2 dominates at high temperatures (>1000K). Formation of Ovac is energetically more favorable on TiO2-terminated surfaces than on BaO-terminated surfaces. Adsorption of oxygenated species (O*, HO*, HOO*) occurs preferentially on Ti5c sites, with binding energies increasing from the perfect surface to the reduced surface (cBTO-TiO2 → cBTO-TiO2−x). Adsorption of O* exhibits two states: radical adsorbate and surface hole (h+), with a transition state energy barrier of ~0.3 eV. The reaction step from radical O* to surface hole (h+) involves electron transfer from a surface oxygen atom connected to the Ti adsorption site. |

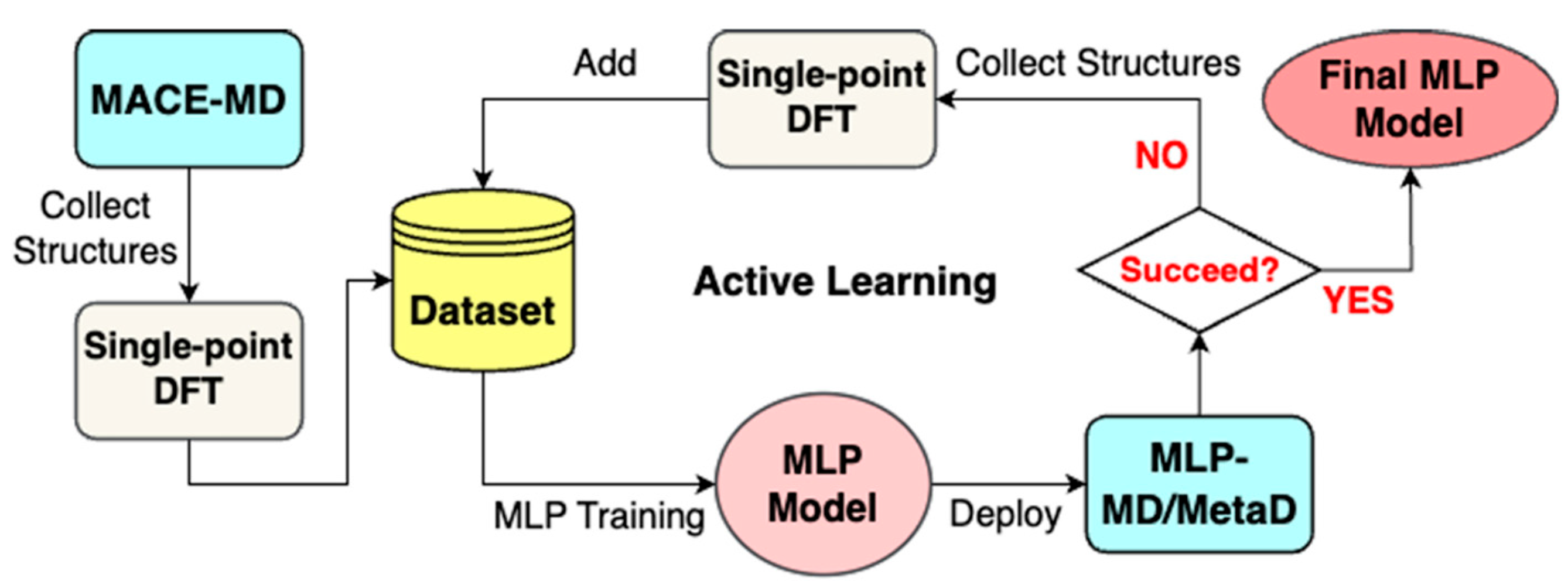

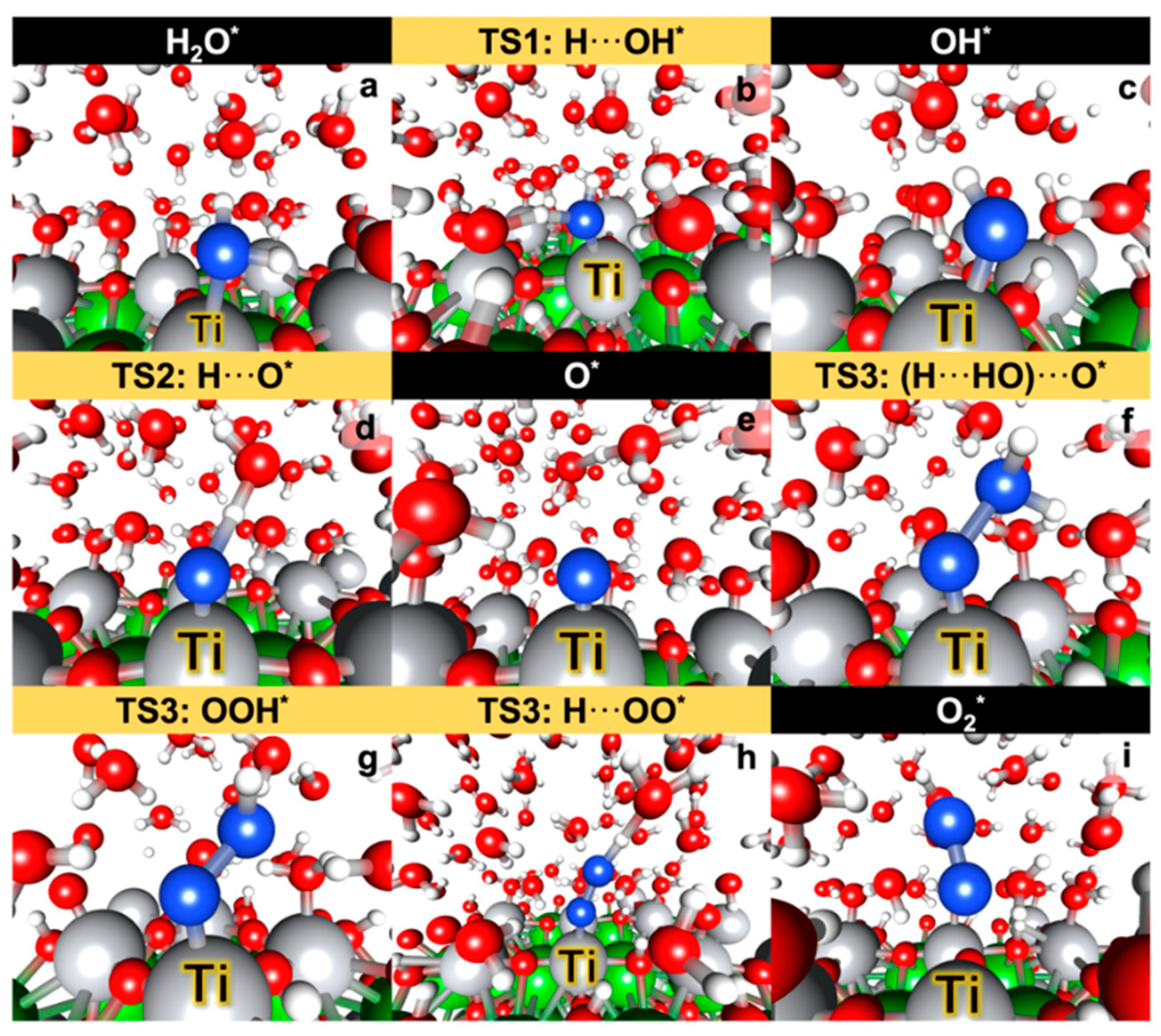

2.2. Ab initio MD Simulations

2.3. Classical All-Atom MD Simulations

3. Conclusions and Outlook

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CV | Conduction band |

| DFT | Density Functional Theory |

| MD | Molecular Dynamics |

| MLP | Machine learning potentials |

| SMR | Steam methane reforming |

| VB | Valence band |

References

- Atilhan, S.; Park, S.; El-Halwagi, M.M.; Atilhan, M.; Moore, M.; Nielsen, R.B. Green hydrogen as an alternative fuel for the shipping industry. Curr. Opin. Chem. Eng. 2021, 31, 100668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qazi, U.Y. Future of hydrogen as an alternative fuel for next-generation industrial applications; challenges and expected opportunities. Energies 2022, 15, 4741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, S.E.; Wahid, M.A. Hydrogen production from renewable and sustainable energy resources: Promising green energy carrier for clean development. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 57, 850–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiwen, L.; Bin, Y.; Tao, Z. Economic analysis of hydrogen production from steam reforming process: A literature review. Energy Sources, Part B 2018, 13, 109–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franchi, G.; Capocelli, M.; De Falco, M.; Piemonte, V.; Barba, D. Hydrogen production via steam reforming: A critical analysis of MR and RMM technologies. Membranes 2020, 10, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranjekar, A.M.; Yadav, G.D. Steam reforming of methanol for hydrogen production: A critical analysis of catalysis, processes, and scope. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2021, 60, 89–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Wang, Z.; Gong, X.; Guo, Z. The intensification technologies to water electrolysis for hydrogen production–A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2014, 29, 573–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Shafie, M. Hydrogen production by water electrolysis technologies: A review. Results Eng. 2023, 20, 101426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shayan, E.; Zare, V.; Mirzaee, I.J.E.C. Hydrogen production from biomass gasification; a theoretical comparison of using different gasification agents. Energy Convers. Manag. 2018, 159, 30–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tezer, Ö.; Karabağ, N.; Öngen, A.; Çolpan, C.Ö.; Ayol, A. Biomass gasification for sustainable energy production: A review. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2022, 47, 15419–15433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhlaghi, N.; Najafpour-Darzi, G. A comprehensive review on biological hydrogen production. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2020, 45, 22492–22512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Zhou, Q.; Yu, D. The future of hydrogen energy: Bio-hydrogen production technology. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2022, 47, 33677–33698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razi, F.; Dincer, I.; Gabriel, K. Exergoenvironmental analysis of the integrated copper-chlorine cycle for hydrogen production. Energy 2021, 226, 120426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strušnik, D.; Avsec, J. Exergoeconomic machine-learning method of integrating a thermochemical Cu–Cl cycle in a multigeneration combined cycle gas turbine for hydrogen production. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2022, 47, 17121–17149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- . [CrossRef]

- Song, H.; Luo, S.; Huang, H.; Deng, B.; Ye, J. Solar-driven hydrogen production: Recent advances, challenges, and future perspectives. ACS Energy Lett. 2022, 7, 1043–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeda, S.; Nam, H.; Chapman, A. Low-carbon energy transition with the sun and forest: Solar-driven hydrogen production from biomass. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2022, 47, 24651–24668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, Y.; Lee, D.-K.; Kim, S.M.; Park, W.; Cho, S.Y.; Sim, U. Low Dimensional Carbon-Based Catalysts for Efficient Photocatalytic and Photo/Electrochemical Water Splitting Reactions. Materials 2020, 13, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eidsvåg, H.; Bentouba, S.; Vajeeston, P.; Yohi, S.; Velauthapillai, D. TiO2 as a Photocatalyst for Water Splitting—An Experimental and Theoretical Review. Molecules 2021, 26, 1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadeem, M.A.; Khan, M.A.; Ziani, A.A.; Idriss, H. An Overview of the Photocatalytic Water Splitting over Suspended Particles. Catalysts 2021, 11, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arunachalam, P.; Nagai, K.; Amer, M.S.; Ghanem, M.A.; Ramalingam, R.J.; Al-Mayouf, A.M. Recent Developments in the Use of Heterogeneous Semiconductor Photocatalyst Based Materials for a Visible-Light-Induced Water-Splitting System—A Brief Review. Catalysts 2021, 11, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, L.; Guan, X.; Zong, S.; Dai, A.; Qu, J. Cocatalysts for Photocatalytic Overall Water Splitting: A Mini Review. Catalysts 2023, 13, 355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakhar, M.; Kumar, A.; Ahluwalia, P.K.; Tankeshwar, K.; Pandey, R. Engineering 2D Materials for Photocatalytic Water-Splitting from a Theoretical Perspective. Materials 2022, 15, 2221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dauletbekova, A.; Abuova, F.; Piskunov, S. First-principles modeling of the H color centers in MgF₂ crystals. Phys. Status Solidi C 2012, 10, 160–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abuova, F.U.; Kotomin, E.A.; Lisitsyn, V.M.; Akilbekov, A.T.; Piskunov, S. Ab initio modeling of radiation damage in MgF₂ crystals. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. B 2014, 326, 314–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goumri-Said, S.; Kanoun, M.B. Insight into the Effect of Anionic–Anionic Co-Doping on BaTiO3 for Visible Light Photocatalytic Water Splitting: A First-Principles Hybrid Computational Study. Catalysts 2022, 12, 1672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.; Lin, H.; Hu, J.; Su, Z.; Zhang, Y. Computational Study of Novel Semiconducting Sc2CT2 (T = F, Cl, Br) MXenes for Visible-Light Photocatalytic Water Splitting. Materials 2021, 14, 4739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Xie, W.; Guo, S.; Chang, J.; Chen, Y.; Long, X.; Zhou, L.; Ang, Y.S.; Yuan, H. Two-Dimensional GeC/MXY (M = Zr, Hf; X, Y = S, Se) Heterojunctions Used as Highly Efficient Overall Water-Splitting Photocatalysts. Molecules 2024, 29, 2793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, H.; Li, Y.; Zhang, M.; Zheng, Y. Designing a 0D/1D S-Scheme Heterojunction of Cadmium Selenide and Polymeric Carbon Nitride for Photocatalytic Water Splitting and Carbon Dioxide Reduction. Molecules 2022, 27, 6286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Chen, Z.; Cheng, X.; Shi, W. Research Progress of ZnIn2S4-Based Catalysts for Photocatalytic Overall Water Splitting. Catalysts 2023, 13, 967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Liu, J.; Xu, T.; Ji, W.; Zong, X. Recent Advances on Small Band Gap Semiconductor Materials (≤2.1 eV) for Solar Water Splitting. Catalysts 2023, 13, 728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morante, N.; Folliero, V.; Dell’Annunziata, F.; Capuano, N.; Mancuso, A.; Monzillo, K.; Galdiero, M.; Sannino, D.; Franci, G. Characterization and Photocatalytic and Antibacterial Properties of Ag- and TiOx-Based (x = 2, 3) Composite Nanomaterials under UV Irradiation. Materials 2024, 17, 2178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Z.; Li, R.; Zhao, C.; Pei, J. A Study on the Effect of Conductive Particles on the Performance of Road-Suitable Barium Titanate/Polyvinylidene Fluoride Composite Materials. Materials 2025, 18, 1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mamani Flores, E.; Vera Barrios, B.S.; HuillcaHuillca, J.C.; Chacaltana García, J.A.; Polo Bravo, C.A.; Nina Mendoza, H.E.; Quispe Cohaila, A.B.; Gamarra Gómez, F.; Tamayo Calderón, R.M.; Fora Quispe, G.d.L.; et al. Cr3+ Doping Effects on Structural, Optical, and Morphological Characteristics of BaTiO3 Nanoparticles and Their Bioactive Behavior. Crystals 2024, 14, 998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abidin, M.Z.U.; Ikram, M.; Moeen, S.; Nazir, G.; Kanoun, M.B.; Goumri-Said, S. A comprehensive review on the synthesis of ferrite nanomaterials via bottom-up and top-down approaches: Advantages, disadvantages, characterizations, and computational insights. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2024, 520, 216158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Q.; Cui, X.F.; Zhao, M. Size effects on Curie temperature of ferroelectric particles. Appl. Phys. A Mater. Sci. Process. 2004, 78, 703–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sood, A.; Desseigne, M.; Dev, A.; Maurizi, L.; Kumar, A.; Millot, N.; Han, S.S. A Comprehensive Review on Barium Titanate Nanoparticles as a Persuasive Piezoelectric Material for Biomedical Applications: Prospects and Challenges. Small 2023, 19, e2206401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, X.Y.; Jiang, Q. Size and interface effects on Curie temperature of perovskite ferroelectric nanosolids. J. Nanopart. Res. 2007, 9, 595–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wada, S.; Hoshina, T.; Yasuno, H.; Ohishi, M.; Kakemoto, H.; Tsurumi, T.; Yashima, M. Size Effect of Dielectric Properties for Barium Titanate Particles and Its Model. Key Eng. Mater. 2006, 301, 27–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, A.; Liton, M.N.H.; Sarker, M.S.I.; Rahman, M.M.; Khan, M.K.R. A comprehensive DFT evaluation of catalytic and optoelectronic properties of BaTiO₃ polymorphs. Phys. B: Condens. Matter 2023, 648, 414418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navas, D.; Fuentes, S.; Castro-Alvarez, A.; Chavez-Angel, E. Review on Sol-Gel Synthesis of Perovskite and Oxide Nanomaterials. Gels 2021, 7, 275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, W.; Quilitz, M.; Schmidt, H. Nanoscaled BaTiO3 powders with a large surface area synthesized by precipitation from aqueous solutions: Preparation, characterization and sintering. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2007, 27, 3149–3159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suherman, B.; Nurosyid, F.; Khairuddin; Sandi, D.K.; Irian, Y. Impacts of low sintering temperature on microstructure, atomic bonds, and dielectric constant of barium titanate (BaTiO3) prepared by co-precipitation technique. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2022, 2190, 12006. [CrossRef]

- Hayashi, H.; Hakuta, Y. Hydrothermal Synthesis of Metal Oxide Nanoparticles in Supercritical Water. Materials 2010, 3, 3794–3817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khort, A.A.; Podbolotov, K.B. Preparation of BaTiO3 nanopowders by the solution combustion method. Ceram. Int. 2016, 42, 15343–15348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, G.J.; Kim, H.S.; Cho, Y.S. BaTiO3 particles prepared by microwave-assisted hydrothermal reaction using titanium acylate precursors. Mater. Lett. 1999, 41, 122–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buscaglia, V.; Buscaglia, M.T.; Canu, G. BaTiO3-Based Ceramics: Fundamentals, Properties and Applications. Encyclopedia of Materials: Technical Ceramics and Glasses; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; pp. 311–344. ISBN 9780128222331. [Google Scholar]

- Ramakanth, S.; James Raju, K.C. Band gap narrowing in BaTiO3 nanoparticles facilitated by multiple mechanisms. J. Appl. Phys. 2014, 115, 173507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tewatia, K.; Sharma, A.; Sharma, M.; Kumar, A. Factors affecting morphological and electrical properties of Barium Titanate: A brief review. Mater. Today Proc. 2021, 44, 4548–4556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Gori, Y.; Kumar, A.; Meena, C.S.; Dutt, N. (Eds.) Advanced Materials for Biomedical Applications, 1st ed.; Taylor and Francis: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2023; ISBN 9781032356068.

- Benyoussef, M.; Mura, T.; Saitzek, S.; Azrour, F.; Blach, J.-F.; Lahmar, A.; Gagou, Y.; El Marssi, M.; Sayede, A.; Jouiad, M. Nanostructured BaTi1−xSnxO3 ferroelectric materials for electrocaloric applications and energy performance. Curr. Appl. Phys. 2022, 38, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, L.; Bi, X. Microstructure and grain size dependence of ferroelectric properties of BaTiO3 thin films on LaNiO3 buffered Si. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2009, 29, 1995–2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buscaglia, M.T.; Buscaglia, V.; Viviani, M.; Nanni, P.; Hanuskova, M. Influence of foreign ions on the crystal structure of BaTiO3. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2000, 20, 1997–2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khedhri, M.H.; Abdelmoula, N.; Khemakhem, H.; Douali, R.; Dubois, F. Structural, spectroscopic and dielectric properties of Ca-doped BaTiO3. Appl. Phys. A Mater. Sci. Process. 2019, 125, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Lu, Y.; Han, D.D.; Liu, Q.L.; Wang, Y.D.; Sun, X.Y. Structure and Dielectric Properties of Ce and Ca Co-Doped BaTiO3 Ceramics. Key Eng. Mater. 2016, 680, 184–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rached, A.; Wederni, M.A.; Belkahla, A.; Dhahri, J.; Khirouni, K.; Alaya, S.; Martín-Palma, R.J. Effect of doping in the physico-chemical properties of BaTiO3 ceramics. Phys. B Condens. Matter 2020, 596, 412343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, T.; Balasubramanian, G. Predictive Modeling of Molecular Mechanisms in Hydrogen Production and Storage Materials. Materials 2023, 16, 6050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inerbaev, T.M.; Abuova, A.U.; Zakiyeva, Z.Y.; Abuova, F.U.; Mastrikov, Y.A.; Sokolov, M.; Gryaznov, D.; Kotomin, E.A. Effect of Rh doping on optical absorption and oxygen evolution reaction activity on BaTiO₃ (001) surfaces. Molecules 2024, 29, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Yu, Z.; Ji, X.; Huang, R.; Luo, L.; Tang, Z.; Zhang, Y. Insight into the effect of pH on the ferroelectric polarization field applied in photoelectrochemical water oxidation. Mater. Sci. Semicond. Process. 2022, 147, 106729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boonpalit, K.; Artrith, N. Mechanistic Insights into the Oxygen Evolution Reaction on Nickel-Doped Barium Titanate via Machine Learning-Accelerated Simulations. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2412.15452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradley, R.; Radhakrishnan, R. Coarse-Grained Models for Protein-Cell Membrane Interactions. Polymers 2013, 5, 890–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, H.; Yang, J.; Yang, W.; Zhong, H.; Lin, J.; Radjenovic, P.M.; Sun, L.; Zhang, H.; Xu, J.; Tian, Z.; Li, J. Core–Shell–Satellite plasmonic photocatalyst for broad-spectrum photocatalytic water splitting. ACS Mater. Lett. 2020, 3, 69–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goga, N.; Mayrhofer, L.; Tranca, I.; Nedea, S.; Heijmans, K.; Ponnuchamy, V.; Vasilateanu, A. A Review of Recent Developments in Molecular Dynamics Simulations of the Photoelectrochemical Water Splitting Process. Catalysts 2021, 11, 807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdikarimova, U.; Bissenova, M.; Matsko, N.; Issadykov, A.; Khromushin, I.; Aksenova, T.; Munasbayeva, K.; Slyamzhanov, E.; Serik, A. Visible Light-Driven Photocatalysis of Al-Doped SrTiO3: Experimental and DFT Study. Molecules 2024, 29, 5326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eglitis, R.I.; Piskunov, S.; Popov, A.I.; Purans, J.; Bocharov, D.; Jia, R. Systematic Trends in Hybrid-DFT Computations of BaTiO3/SrTiO3, PbTiO3/SrTiO3 and PbZrO3/SrZrO3 (001) Hetero Structures. Condens. Matter 2022, 7, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eglitis, R.I.; Purans, J.; Jia, R. Comparative Hybrid Hartree-Fock-DFT Calculations of WO2-Terminated Cubic WO3 as Well as SrTiO3, BaTiO3, PbTiO3 and CaTiO3 (001) Surfaces. Crystals 2021, 11, 455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sikam, P.; Thirayatorn, R.; Kaewmaraya, T.; Thongbai, P.; Moontragoon, P.; Ikonic, Z. Improved Thermoelectric Properties of SrTiO3 via (La, Dy and N) Co-Doping: DFT Approach. Molecules 2022, 27, 7923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eglitis, R.I.; Jia, R. Review of Systematic Tendencies in (001), (011) and (111) Surfaces Using B3PW as Well as B3LYP Computations of BaTiO3, CaTiO3, PbTiO3, SrTiO3, BaZrO3, CaZrO3, PbZrO3 and SrZrO3 Perovskites. Materials 2023, 16, 7623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jouybar, S.; Naji, L.; Sarabadani Tafreshi, S.; de Leeuw, N.H. A Density Functional Theory Study of the Physico-Chemical Properties of Alkali Metal Titanate Perovskites for Solar Cell Applications. Molecules 2024, 29, 3355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elegbeleye, I.F.; Maluta, N.E.; Maphanga, R.R. Density Functional Theory Study of Optical and Electronic Properties of (TiO2)n=5,8,68 Clusters for Application in Solar Cells. Molecules 2021, 26, 955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Kang, W.; Deng, N.; Pan, Y.; Sun, W.; Ni, J.; Kang, X. TiO2 Gas Sensors Combining Experimental and DFT Calculations: A Review. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 3611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gustavsen, K.R.; Feng, T.; Huang, H.; Li, G.; Narkiewicz, U.; Wang, K. DFT Calculation of Carbon-Doped TiO2 Nanocomposites. Materials 2023, 16, 6117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhou, T.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, S.; Bai, J.; Li, J.; Zhou, B. The design of high-performance photoanode of CQDs/TiO₂/WO₃ based on DFT alignment of lattice parameter and energy band, and charge distribution. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2021, 600, 828–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thongyong, N.; Chanlek, N.; Srepusharawoot, P.; Takesada, M.; Cann, D.P.; Thongbai, P. Experimental study and DFT calculations of improved giant dielectric properties of Ni²⁺/Ta⁵⁺ co-doped TiO₂ by engineering defects and internal interfaces. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2022, 42, 4944–4952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amrhar, O.; Lee, H.S.; Lgaz, H.; Berisha, A.; Ebenso, E.E.; Cho, Y. Computational insights into the adsorption mechanisms of anionic dyes on the rutile TiO₂ (110) surface: Combining SCC-DFT tight binding with quantum chemical and molecular dynamics simulations. J. Mol. Liq. 2023, 377, 121554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Z.; Wodaczek, F.; Liu, K.; Stein, F.; Hutter, J.; Chen, J.; Cheng, B. Mechanistic insight on water dissociation on pristine low-index TiO₂ surfaces from machine learning molecular dynamics simulations. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 6131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boboriko, N.E.; Dzichenka, Y.U. Molecular dynamics simulation as a tool for prediction of the properties of TiO₂ and TiO₂: MoO₃-based chemical gas sensors. J. Alloys Compd. 2021, 855, 157490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raffaini, G. Surface chemistry, crystal structure, size, and topography role in the albumin adsorption process on TiO₂ anatase crystallographic faces and its 3D-nanocrystal: A molecular dynamics study. Coatings 2021, 11, 420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maleki, F.; Di Liberto, G.; Pacchioni, G. pH-and facet-dependent surface chemistry of TiO₂ in aqueous environment from first principles. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2023, 15, 11216–11224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nosaka, Y. Water Photo-Oxidation over TiO2—History and Reaction Mechanism. Catalysts 2022, 12, 1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estévez Ruiz, E.P.; Lago, J.L.; Thirumuruganandham, S.P. Experimental Studies on TiO2 NT with Metal Dopants through Co-Precipitation, Sol–Gel, Hydrothermal Scheme and Corresponding Computational Molecular Evaluations. Materials 2023, 16, 3076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, J.A.; Schall, J.D.; Maskey, S.; Mikulski, P.T.; Knippenberg, M.T.; Morrow, B.H. Review of force fields and intermolecular potentials used in atomistic computational materials research. Appl. Phys. Rev. 2018, 5, 031104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Bonati, L.; Polino, D.; Parrinello, M. Using metadynamics to build neural network potentials for reactive events: The case of urea decomposition in water. Catal. Today 2022, 387, 143–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowe, J.S.; Siegel, D.J. Modeling the interface between lithium metal and its native oxide. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12, 46015–46026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joraleechanchai, N.; Duangdangchote, S.; Sawangphruk, M. Machine Learning and Reactive Force Field Molecular Dynamics Investigation of Electrolytes for Ultra-fast Charging Li-ion Batteries. ECS Trans. 2020, 97, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, N.; Chen, X.; Fu, Z.H.; Zhang, Q. Applying classical, ab initio, and machine-learning molecular dynamics simulations to the liquid electrolyte for rechargeable batteries. Chem. Rev. 2022, 122, 10970–11021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Liu, Y.; Xu, Y.; Guo, X.; Cao, Y.; Ming, W. Review: Modeling and Simulation of Membrane Electrode Material Structure for Proton Exchange Membrane Fuel Cells. Coatings 2022, 12, 1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samantaray, S.; Mohanty, D.; Satpathy, S.K.; Hung, I.-M. Exploring Recent Developments in Graphene-Based Cathode Materials for Fuel Cell Applications: A Comprehensive Overview. Molecules 2024, 29, 2937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhanasekaran, A.; Subramanian, Y.; Omeiza, L.A.; Raj, V.; Yassin, H.P.H.M.; SA, M.A.; Azad, A.K. Computational Fluid Dynamics for Protonic Ceramic Fuel Cell Stack Modeling: A Brief Review. Energies 2023, 16, 208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Qu, Z.; Wang, X.; Zhang, J. A Molecular Model of PEMFC Catalyst Layer: Simulation on Reactant Transport and Thermal Conduction. Membranes 2021, 11, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Hou, W.; Zhai, F.; Cheng, J.; Yuan, S.; Li, Y.; Wang, N.; Zhang, L.; Ren, J. Reversible Hydrogen Storage Media by g-CN Monolayer Decorated with NLi4: A First-Principles Study. Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Li, Q.; Wang, F.; Wu, J.; Wang, Y. The Carrying Behavior of Water-Based Fracturing Fluid in Shale Reservoir Fractures and Molecular Dynamics of Sand-Carrying Mechanism. Processes 2024, 12, 2051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.; Wei, L. Review on Characterization of Biochar Derived from Biomass Pyrolysis via Reactive Molecular Dynamics Simulations. J. Compos. Sci. 2023, 7, 354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shelyapina, M.G. Hydrogen Diffusion on, into and in Magnesium Probed by DFT: A Review. Hydrogen 2022, 3, 285–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutisya, S.M.; Kalinichev, A.G. Carbonation reaction mechanisms of portlandite predicted from enhanced Ab Initio molecular dynamics simulations. Minerals 2021, 11, 509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohmuean, P.; Inthomya, W.; Wongkoblap, A.; Tangsathitkulchai, C. Monte Carlo Simulation and Experimental Studies of CO2, CH4 and Their Mixture Capture in Porous Carbons. Molecules 2021, 26, 2413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sobornova, V.V.; Belov, K.V.; Dyshin, A.A.; Gurina, D.L.; Khodov, I.A.; Kiselev, M.G. Molecular Dynamics and Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Studies of Supercritical CO2 Sorption in Poly(Methyl Methacrylate). Polymers 2022, 14, 5332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, K.; Niu, Z.; Kong, S.; Jia, B. Impact of Supercritical Carbon Dioxide on Pore Structure and Gas Transport in Bituminous Coal: An Integrated Experiment and Simulation. Molecules 2025, 30, 1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filipe, H.A.L.; Loura, L.M.S. Molecular Dynamics Simulations: Advances and Applications. Molecules 2022, 27, 2105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A.; Dong, X.; Raghavan, V. An Overview of Molecular Dynamics Simulation for Food Products and Processes. Processes 2022, 10, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celik, I.; Yadav, R.; Duzgun, Z.; Albogami, S.; El-Shehawi, A.M.; Fatimawali; Idroes, R.; Tallei, T.E.; Emran, T.B. Interactions of the Receptor Binding Domain of SARS-CoV-2 Variants with hACE2: Insights from Molecular Docking Analysis and Molecular Dynamic Simulation. Biology 2021, 10, 880. [CrossRef]

- SdfLiu, W.D.; Yu, Y.; Dargusch, M.; Liu, Q.; Chen, Z.G. Carbon allotrope hybrids advance thermoelectric development and applications. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 141, 110800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.Q.; Liu, Y.J.; Liu, Y.L.; Zhao, J.X. Boosting sensitivity of Boron Nitride Nanotube (BNNT) to nitrogen dioxide by Fe encapsulation. J. Mol. Graph. Model. 2014, 51, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Quintana, R.; Carbajal-Franco, G.; Rojas-Chávez, H. DFT study of the H2 molecules adsorption on pristine and Ni doped graphite surfaces. Mater. Lett. 2021, 293, 129660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.-S.; Liu, Y.-T.; Yao, T.-T.; Wu, G.-P.; Liu, Q. Oxygen defect engineering toward the length-selective tailoring of carbon nanotubes via a two-step electrochemical strategy. J. Phys. Chem. C 2020, 124, 27097–27106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elias, A.; Uddin, N.; Hossain, A.; Saha, J.K.; Siddiquey, I.A.; Sarker, D.R.; Diba, Z.R.; Uddin, J.; Choudhury, M.H.R.; Firoz, S.H. An experimental and theoretical study of the effect of Ce doping in ZnO/CNT composite thin film with enhanced visible light photo-catalysis. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2019, 44, 20068–20078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, Z.; Jia, X.; An, L. CO adsorption on Fe-doped vacancy-defected CNTs–A DFT study. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2019, 730, 316–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakhar, M.; Kumar, A.; Ahluwalia, P.K.; Tankeshwar, K.; Pandey, R. Engineering 2D Materials for Photocatalytic Water-Splitting from a Theoretical Perspective. Materials 2022, 15, 2221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Wan, Q.; Anpo, M.; Lin, S. Bandgap opening of graphdiyne monolayer via B, N-codoping for photocatalytic overall water splitting: Design strategy from DFT studies. J. Phys. Chem. C 2020, 124, 6624–6633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loh, G.; Pandey, R.; Yap, Y.K.; Karna, S.P. MoS2 quantum dot: Effects of passivation, additional layer, and h-BN substrate on its stability and electronic properties. J. Phys. Chem. C 2015, 119, 1565–1574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, D.; Kumar, A.; Chakrabarti, A.; Pandey, R. Stacking-dependent electronic properties of aluminene based multilayer van der Waals heterostructures. Comput. Mater. Sci. 2020, 185, 109952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.-P.; Bocharov, D.; Isakoviča, I.; Pankratov, V.; Popov, A.A.; Popov, A.I.; Piskunov, S. Chlorine Adsorption on TiO2(110)/Water Interface: Nonadiabatic Molecular Dynamics Simulations for Photocatalytic Water Splitting. Electron. Mater. 2023, 4, 33–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tada, K.; Sakata, K.; Yamada, S.; Okazaki, K.; Kitagawa, Y.; Kawakami, T.; Yamanaka, S.; Okumura, M. DFT calculations for Au adsorption onto a reduced TiO2 (110) surface with the coexistence of Cl. Mol. Phys. 2014, 112, 365–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Gao, D.; Peng, S.; Lu, G.; Li, S. Photocatalytic hydrogen evolution over Pt/Cd0.5Zn0.5S from saltwater using glucose as electron donor: An investigation of the influence of electrolyte NaCl. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2011, 36, 4291–4297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alghamdi, H.; Idriss, H. Study of the modes of adsorption and electronic structure of hydrogen peroxide and ethanol over TiO2 rutile (110) surface within the context of water splitting. Surf. Sci. 2018, 669, 103–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vu, N.H.; Le, H.V.; Cao, T.M.; Pham, V.V.; Le, H.M.; Nguyen-Manh, D. Anatase–rutile phase transformation of titanium dioxide bulk material: A DFT+U approach. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 2012, 24, 405501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolesov, G.; Grånäs, O.; Hoyt, R.; Vinichenko, D.; Kaxiras, E. Real–time TD–DFT with classical ion dynamics: Methodology and applications. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2016, 12, 466–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, P.; Chen, D.; Lian, C.; Zhang, C.; Meng, S. First–principles dynamics of photoexcited molecules and materials towards a quantum description. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Comput. Mol. Sci. 2021, 11, e1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, T.A.; Ping, Y.; Galli, G. Modelling heterogeneous interfaces for solar water splitting. Nat. Mater. 2017, 16, 401–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agosta, L.; Brandt, E.G.; Lyubartsev, A.P. Diffusion and reaction pathways of water near fully hydrated TiO2 surfaces from ab initio molecular dynamics. J. Chem. Phys. 2017, 147, 024704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balzaretti, F.; Gupta, V.; Ciacchi, L.C.; Aradi, B.; Frauenheim, T.; Köppen, S. Water reactions on reconstructed rutile TiO2: A density functional theory/density functional tight binding approach. J. Phys. Chem. C 2021, 125, 13234–13246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, M.; Connor, P.K.N.; Ho, G.W. Plasmonic photothermic directed broadband sunlight harnessing for seawater catalysis and desalination. Energy Environ. Sci. 2016, 9, 3151–3160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schilling, M.; Luber, S. Computational Modeling of Cobalt-Based Water Oxidation: Current Status and Future Challenges. Front Chem. 2018, 6, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VandeVondele, J.; Mohamed, F.; Krack, M.; Hutter, J.; Sprik, M.; Parrinello, M. The influence of temperature and density functional models in ab initio molecular dynamics simulation of liquid water. J. Chem. Phys. 2005, 122, 014515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sinha, V.; Govindarajan, N.; de Bruin, B.; Meijer, E.J. How Solvent Affects C–H Activation and Hydrogen Production Pathways in Homogeneous Ru-Catalyzed Methanol Dehydrogenation Reactions. ACS Catal. 2018, 8, 6908–6913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, J.; Liu, X.; VandeVondele, J.; Sulpizi, M.; Sprik, M. Redox Potentials and Acidity Constants from Density Functional Theory Based Molecular Dynamics. Acc. Chem. Res. 2014, 47, 3522–3529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Jiang, B.; Liu, Y.; Liu, L.; Xia, T.; Zhang, X.; Ye, C.; Yu, Y.; Wang, B. Two-Dimensional As/BlueP van der Waals Hetero-Structure as a Promising Photocatalyst for Water Splitting: A DFT Study. Coatings 2020, 10, 1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.K.; Mathew, K.; Zhuang, H.L.; Henning, R.G. Computational screening of 2D materials for photocatalysis. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2015, 6, 1087–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.G.; Lv, Y.H.; Xu, J.; Liu, Y.F.; Zhang, R.Q.; Zhu, Y.F. A strategy of enhancing the photoactivity of g-C3N4 via doping of nonmetal elements: A first-principles study. J. Phys. Chem. C 2012, 116, 23485–23493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Zhao, Y.C.; Zeng, S.M.; Ni, J. The realization of half-metal and spin-semiconductor for metal adatoms on arsenene. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2016, 390, 60–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.H.; Wang, B.J.; Cai, X.L.; Zhang, L.W.; Wang, G.D.; Ke, S.H. Tunable electronic properties of arsenene/GaS van der Waals heterostructures. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 28393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, L.Z.; Li, X.P.; Geng, Z.D.; Wang, T.X.; Xia, C.X. Band alignment tuning in GeS/arsenene staggered hetero-structures. J. Alloy. Compd. 2019, 793, 283–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamdagni, P.; Thakur, A.; Kumar, A.; Ahluwalia, P.K.; Pandey, R. Two dimensional allotropes of arsenene with a wide range of high and anisotropic carrier mobility. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2018, 20, 29939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.J.; Li, X.H.; Cai, X.L.; Yu, W.Y.; Zhang, L.W.; Zhao, R.Q.; Ke, S.H. Blue Phosphorus/Mg(OH)2 van der Waals hetero-structures as Promising Visible-Light Photocatalysts for Water Splitting. J. Phys. Chem. C 2018, 122, 7075–7080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.F.; Ma, X.F.; Lei, Z.; Wan, X.G.; Rao, W.F. Theoretical design of blue phosphorene/arsenene lateral heterostructures with superior electronic properties. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 2018, 51, 255304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inerbaev, T.M.; Graupner, D.R.; Abuova, A.U.; Abuova, F.U.; Kilin, D.S. Optical properties of BaTiO₃ at room temperature: DFT modelling. RSC Advances 2025, 15, 5405–5412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogunkunle, S.A.; Mortier, F.; Bouzid, A.; Hinsch, J.J.; Zhang, L.; Wu, Z.; Bernard, S.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, Y. Navigating Alkaline Hydrogen Evolution Reaction Descriptors for Electrocatalyst Design. Catalysts 2024, 14, 608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miran, H.A.; Jaf, Z.N.; Altarawneh, M.; Jiang, Z.-T. An Insight into Geometries and Catalytic Applications of CeO2 from a DFT Outlook. Molecules 2021, 26, 6485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Chen, Y.; Chen, T.; Rajendran, S.; Zeng, Z.; Qin, J.; Zhang, X. A long-standing polarized electric field in TiO₂@BaTiO₃/CdS nanocomposite for effective photocatalytic hydrogen evolution. Fuel 2021, 314, 122758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, W.; Ma, X.; Chen, J.; Shi, R.; Wang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Jing, D.; Yuan, H.; Du, J.; Que, M. Synergy of oxygen vacancy and piezoelectricity effect promotes the CO₂ photoreduction by BaTiO₃. Applied Surface Science 2023, 619, 156773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Wang, C.; Liu, Y.; Zhou, X. Hybrid density functional theory description of non-metal doping in perovskite BaTiO₃ for visible-light photocatalysis. Journal of Solid State Chemistry 2019, 280, 121018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizwan, M.; Hajra, N.; Zeba, I.; Shakil, M.; Gillani, S.; Usman, Z. Electronic, structural, and optical properties of BaTiO₃ doped with lanthanum (La): Insight from DFT calculation. Optik 2020, 211, 164611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Wang, P.; Luan, S.; Cheng, L.; Fu, Z.; Cao, X.; Zhang, L.; Yu, S.; Sun, R. Vacancy engineering for high tetragonal BaTiO₃ synthesized by solid-state approaches. Powder Technology 2024, 444, 119955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, P.; Yang, F.; Li, R.; Ai, C.; Lin, C.; Lin, S. Improving hydrogen evolution activity of perovskite BaTiO₃ with Mo doping: Experiments and first-principles analysis. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2019, 44, 11695–11704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usman, M.; Rehman, J.U.; Tahir, M.B.; Hussain, A. First-principles calculations to investigate the effect of Cs-doping in BaTiO₃ for water-splitting application. Solid State Communications 2022, 355, 114920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chun, H.; Lee, Y.; Kim, S.; Yoon, Y.; Kim, Y.; Park, S. Surface termination of BaTiO₃(111) single crystal: A combined DFT and XPS study. Applied Surface Science 2021, 578, 152018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahbi, S.; Tahiri, N.; Bounagui, O.E.; Ez-Zahraouy, H. Effects of oxygen group elements on thermodynamic stability, electronic structures, and optical properties of the pure and pressed BaTiO₃ perovskite. Computational Condensed Matter 2022, 32, e00728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahbi, S.; Tahiri, N.; Bounagui, O.E.; Ez-Zahraouy, H. Electronic, optical, and thermoelectric properties of perovskite BaTiO₃ compound under the effect of compressive strain. Chemical Physics 2021, 544, 111105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fo, Y.; Zhou, X. A theoretical study on tetragonal BaTiO₃ modified by surface co-doping for photocatalytic overall water splitting. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2022, 47, 19073–19085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, A.; Liton, M.; Sarker, M.; Rahman, M.; Khan, M. A comprehensive DFT evaluation of catalytic and optoelectronic properties of BaTiO₃ polymorphs. Physica B: Condensed Matter 2022, 648, 414418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhat, D.K.; Bantawal, H.; Pi, U.; Shenoy, U.S. Enhanced photoresponse and efficient charge transfer in porous graphene-BaTiO₃ nanocomposite for high-performance photocatalysis. Diamond and Related Materials 2023, 139, 110312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashir, M.Z.; Naqvi, S.A.Z.; Naeem, M.A.; Munir, R.; Noreen, S. Theoretical study of optoelectronic, elastic, and mechanical properties of gallium-modified barium titanate (Ba₁₋ₓGaₓTiO₃) perovskite ceramics by DFT. Materials Science in Semiconductor Processing 2024, 182, 108734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Ge, K.; Cui, H.; Li, S.; Yang, Y.; Pan, M.; Zhu, L. Self-polarization-enhanced oxygen evolution reaction by flower-like core–shell BaTiO₃@NiFe-layered double hydroxide heterojunctions. Chemical Engineering Journal 2023, 479, 147831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Ji, Y.; Shi, X.; An, P.; Zhang, J.; Li, Y.; Liu, S.F.; Yan, J. Oxygen-deficient BaTiO₃ loading sub-nm PtOₓ for photocatalytic biological wastewater splitting to green hydrogen production. Chemical Engineering Journal 2024, 496, 154261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, M.; Zhong, J.; Li, W.; Hou, H.; Bowen, C.R.; Zhan, X.; Yang, H.; Yang, M.; Chen, Z.; Chen, D.; Liang, Z.; Yang, W. Highly efficient photocatalytic hydrogen evolution enabled by piezotronic effects in SrTiO₃/BaTiO₃ nanofiber heterojunctions. Nano Energy 2024, 127, 109745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zulfiqar, W.; Alay-E-Abbas, S.M. Improved thermodynamic stability and visible light absorption in Zr+Xcodoped (X = S, Se, and Te) BaTiO₃ photocatalysts: A first-principles study. Materials Today Communications 2022, 32, 103867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovač, I; Mužević, M; Pajtler, M.V.; Lukačević, I. Charge carrier dynamics across the metal oxide/BaTiO₃ interfaces toward photovoltaic applications from the theoretical perspective. Surfaces and Interfaces 2023, 39, 102974. [CrossRef]

- Kaptagay, G.A.; Satanova, B.M.; Abuova, A.U.; Konuhova, M.; Zakiyeva, Z.h.Y.e.; Tolegen, U.Z.h.; Koilyk, N.O.; Abuova, F.U. Effect of rhodium doping for photocatalytic activity of barium titanate. Opt. Mater. X 2025, 25, 100382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opoku, F.; Akoto, O.; Kwaansa-Ansah, E.E.; Asare-Donkor, N.K.; Adimado, A.A. Role of BaTiO₃ crystal surfaces on the electronic properties, charge separation, and visible light–response of the most active (001) surface of LaAlO₃: A hybrid density functional study. Chemical Physics Impact 2023, 6, 100236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbasi, P.; Barone, M.R.; De La Paz Cruz-Jáuregui, M.; Valdespino-Padilla, D.; Paik, H.; Kim, T.; Kornblum, L.; Schlom, D.G.; Pascal, T.A.; Fenning, D.P. Ferroelectric Modulation of Surface Electronic States in BaTiO₃ for Enhanced Hydrogen Evolution Activity. Nano Lett. 2022, 22, 4276–4284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunawan, M.; Bowdler, O.; Zhou, S.; Fang, X.; Zhang, Q.; Sakamoto, Y.; Sun, K.; Gunawan, D.; Chang, S.L.; Amal, R.; Valanoor, N.; Scott, J.; Hart, J.N.; Toe, C.Y. Ferroelectric Polarization-Induced Performance Enhancements in BiFeO₃/BiVO₄ Photoanodes for Photoelectrochemical Water Splitting. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goumri-Said, S.; Kanoun, M.B. Insight into the Effect of Anionic–Anionic Co-Doping on BaTiO3 for Visible Light Photocatalytic Water Splitting: A First-Principles Hybrid Computational Study. Catalysts 2022, 12, 1672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrappa, S.; Galbao, S.J.; Krishnan, P.S.S.R.; Koshi, N.A.; Das, S.; Myakala, S.N.; Lee, S.; Dutta, A.; Cherevan, A.; Bhattacharjee, S.; Murthy, D.H.K. Iridium-Doping as a Strategy to Realize Visible-Light Absorption and P-Type Behavior in BaTiO₃. J. Phys. Chem. C 2023, 127, 12383–12393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhat, D.K.; Bantawal, H.; Shenoy, U.S. Rhodium Doping Augments Photocatalytic Activity of Barium Titanate: Effect of Electronic Structure Engineering. Nanoscale Adv. 2020, 2, 5688–5698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiu, H.; Yang, T.; Zhou, J.; Yang, K.; Ying, Y.; Ding, K.; Yang, M.; Huang, H. Tunable Hydrogen Evolution Activity by Modulating Polarization States of Ferroelectric BaTiO₃. J. Mater. Chem. A 2023, 11, 7034–7042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhou, Q.; Zhang, Q.; Ren, Y.; Cui, K.; Cheng, C.; Wu, K. Effects of La-N Co-Doping of BaTiO3 on Its Electron-Optical Properties for Photocatalysis: A DFT Study. Molecules 2024, 29, 2250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saadon, N.M.Q.; Miran, H.A. Optoelectronic Tuning of Barium Titanate Doped with Pt: A Systematic First-Principles Study. Pap. Phys. 2024, 16, 160002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, D.; Upadhyay, S.; Satsangi, V.R.; Shrivastav, R.; Waghmare, U.V.; Dass, S. Nanostructured BaTiO₃/Cu₂O Heterojunction with Improved Photoelectrochemical Activity for H₂ Evolution: Experimental and First-Principles Analysis. Appl. Catal. B 2016, 189, 75–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Ran, L.; Chen, R.; Song, Y.; Gao, J.; Sun, L.; Hou, J. Boosting Charge Mediation in Ferroelectric BaTiO₃₋ₓ-Based Photoanode for Efficient and Stable Photoelectrochemical Water Oxidation. Small Struct. 2023, 4, 2300072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tymińska, N.; Wu, G.; Dupuis, M. Water Oxidation on Oxygen-Deficient Barium Titanate: A First-Principles Study. J. Phys. Chem. C 2017, 121, 8378–8389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.T.; Wen, X.J.; Zhuang, Y.B.; Cheng, J. Molecular insight into the GaP (110)-water interface using machine learning accelerated molecular dynamics. J. Energy Chem. 2023, 82, 239–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, L.; Jia, W.; Cao, X.; Jiao, L. Computational chemistry for water-splitting electrocatalysis. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2024, 53, 2771–2807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Hou, Y.C.; Jiang, Y.; Ni, X.; Wang, Y.; Zou, X. Rational design of water splitting electrocatalysts through computational insights. Chem. Commun. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orhan, I.B.; Zhao, Y.; Babarao, R.; Thornton, A.W.; Le, T.C. Machine Learning Descriptors for CO2 Capture Materials. Molecules 2025, 30, 650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, K.; Yang, C.; Zhang, J.; Li, Y.; Jiang, G.; Chai, J. Machine Learning-Assisted Hartree–Fock Approach for Energy Level Calculations in the Neutral Ytterbium Atom. Entropy 2024, 26, 962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tereshchenko, A.; Pashkov, D.; Guda, A.; Guda, S.; Rusalev, Y.; Soldatov, A. Adsorption Sites on Pd Nanoparticles Unraveled by Machine-Learning Potential with Adaptive Sampling. Molecules 2022, 27, 357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, M.; Desai, R.; Mannodi-Kanakkithodi, A. Screening of novel halide perovskites for photocatalytic water splitting using multi-fidelity machine learning. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2024, 26, 23177–23188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]