1. Introduction

Cholangiocarcinomas are cancers arising from intrahepatic and extrahepatic bile ducts, accounting for 10-25% of all hepatobiliary malignancies [

1]. Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma is rare, but approximately 2500 cases are diagnosed annually in the United States [

2]. The incidence of cholangiocarcinoma has increased in the past few decades [

2]. Cholangiocarcinoma in the United States has been rising, especially for intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Several comprehensive epidemiological studies reveal that from 2001 to 2017, the incidence of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma nearly doubled, with an annual percentage change (APC) ranging from about 3% to 9% [

3]. Cholangiocarcinoma incidence rates are highest in Asian and Pacific Islander populations in the United States, followed by Hispanics, while non-Hispanic Black and White groups have lower rates. [

4,

5].

The common essential risk factors for cholangiocarcinoma include diabetes, cirrhosis, viral hepatitis, and obesity. Less common risks include tobacco use, inflammatory bowel disease, host genetic polymorphisms, and alcohol consumption [

1,

6,

7]. Among other risk factors associated with cholangiocarcinoma are

Opisthorchis viverrini or

Clonorchis sinensis parasitic infections, primary sclerosing cholangitis, and bile duct cysts [

1,

8]. Cholangiocarcinoma portends a high risk of mortality.

2. Methods

2.1. Database - The National Inpatient Sample 2022

This study utilized the National Inpatient Sample (NIS), a widely recognized and publicly accessible database in the United States that compiles inpatient healthcare information from various payers. The NIS is an essential resource for large-scale research, providing detailed regional and national data on hospital utilization, patient access, healthcare costs, quality metrics, insurance status, demographic characteristics, and clinical outcomes. Developed under the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), the dataset is created through a partnership of federal, state, and private entities. It includes a stratified sample representing about 20% of hospital discharges nationwide each year. According to the institutional guidelines at Southeast Health, research involving fully de-identified datasets like the NIS is exempt from Institutional Review Board (IRB) review. Therefore, this project was determined not to require IRB approval.

2.2. Study Population and Study Variable

The data from the 2022 National Inpatient Sample (NIS) were analyzed, and hospital admissions for adults (age > 18 years) with either a primary or secondary diagnosis of cholangiocarcinoma were identified using ICD-10-CM (International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification) codes. Racial groups, including White, African American, Hispanic, Asian or Pacific Islander, Native American, and Other (typically includes individuals who identify with races not explicitly listed, such as multiracial individuals, those from smaller racial groups, or those whose race was reported as "other" on hospital records), were recorded. Sociodemographic characteristics—such as age, gender, insurance status, and income quartile—and hospital-related factors, including facility size, geographic location, U.S. region, and teaching designation, were examined across these racial categories. The key clinical outcomes assessed in this study included in-hospital mortality, discharge disposition, total hospitalization costs, and length of stay.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

A cross-sectional study design was used, and data analysis was conducted using STATA/BE version 18.5. Chi-square tests were employed to examine associations between categorical variables, while independent t-tests were used to compare continuous variables. A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Multivariable logistic regression models were applied to evaluate the relationship between race and various clinical and utilization outcomes. These outcomes included the type of hospital admission, discharge status, healthcare resource utilization, and complications such as mechanical ventilation, acute kidney injury, and sepsis. The analyses adjusted for potential confounding variables, which included obesity, sociodemographic factors, and hospital characteristics.

3. Results

3.1. Patient and Hospital-Level Characteristics

In 2022, 7,479 hospitalizations were recorded for cholangiocarcinoma. Of these, 53.6% were male, and 46.4% were female. 65.99% of patients identified themselves as White, 13.27% as Hispanic, 10.13% as African-American, 6.78% as Asian or Pacific Islander, and 3.81% as Native American or part of other minority groups.

The average age of the patient population was 68 years, with a 95% confidence interval (CI) ranging from 67.7 to 68.3. When looking at specific racial groups, the mean age was 66 years for African American and Hispanic patients. In comparison, the average ages were 69 years for White patients, 67 years for Asian or Pacific Islander patients, and 68 years for Native American patients. A greater proportion of African-American (43.13%) and Hispanic (43.90%) patients were aged 64 years or younger compared to White patients (30.71%). Conversely, the majority of White (69.28%), Asian or Pacific Islander (64.49%), and Native American (65.95%) patients were aged 65 years or older. In contrast, only 56.86% of African-American and 46.09% of Hispanic patients were in this older age group. (p<0.001)

There was a statistically significant difference in gender distribution across racial groups (p< 0.001), with males comprising the majority in all groups, especially among Asians or Pacific Islanders and Native Americans. However, in Hispanic populations, the females outnumbered the males. There were real socioeconomic disparities identified in the study population, with Asian or Pacific Islander (45.80%) and White groups (29.91%) overrepresented in higher income brackets, and African-American (43.11%), Hispanic (31.73%), and Native American (47.73%) groups overrepresented in the lowest income bracket.

White (66.65%) and Native American (65.22%) are most likely to have Medicare, while Medicaid coverage was most common among Hispanics (21.99%), Asian or Pacific Islander (14.69%), and African-American (13.20%) patients. Private insurance was relatively evenly distributed, and Self-pay was most frequent among Hispanic patients (4.05%) and least common among Native Americans (p<0.001). The racial distributions vary significantly by the U.S hospital region, the South having the highest percentage of African-American with 57.26%, the West the highest Hispanics with 39.17%, Asian or Pacific Islander (52.47%), and Native American (40.43%) patients, and all differences showing strong statistical significance (p<0.00). Regardless of race and geography (urban vs rural), most patients received care at teaching hospitals with a p<0.001. The patient and Hospital level characteristics are summarized in

Table 1.

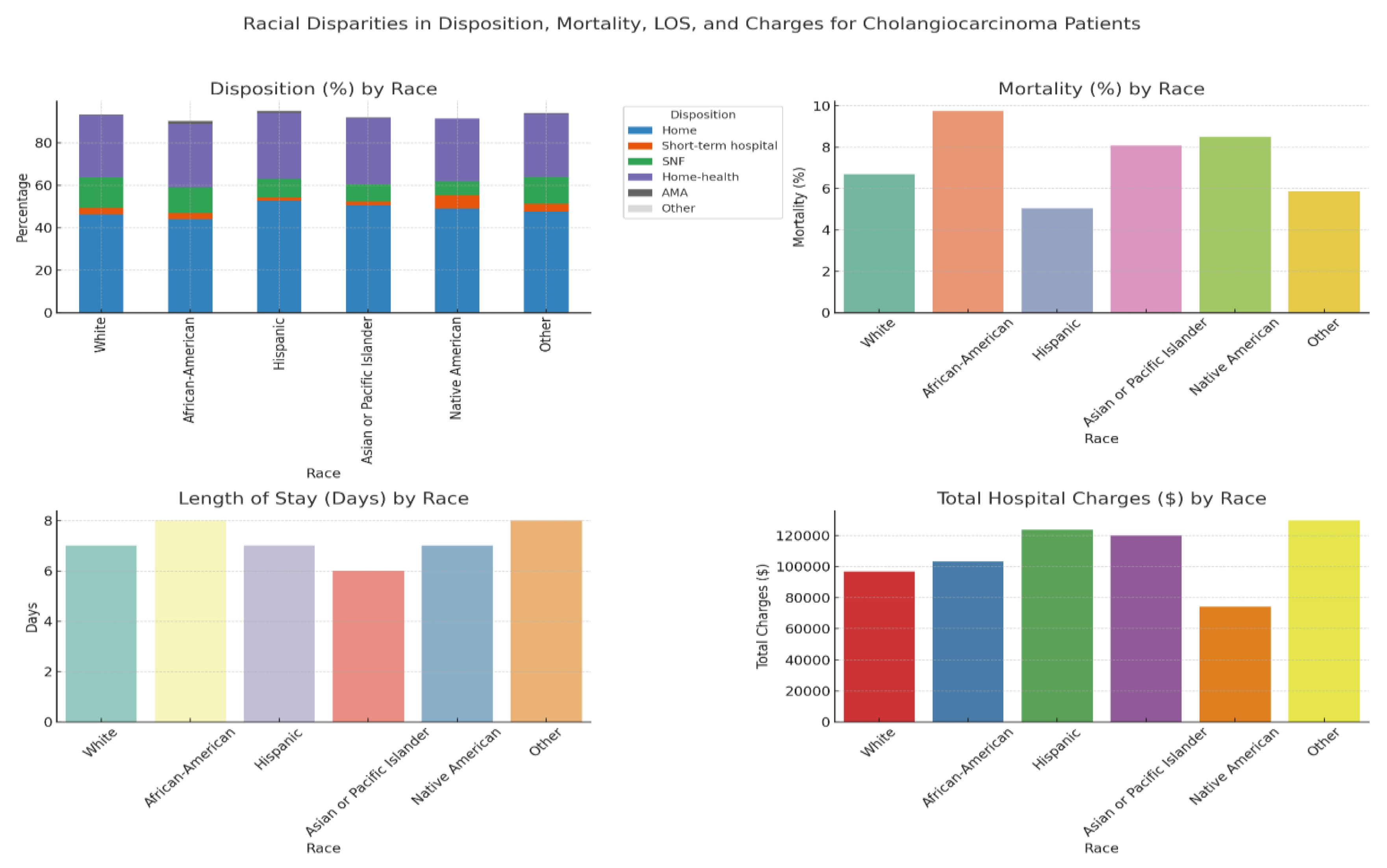

3.2. Primary Outcomes

Among various racial groups, most patients were discharged to their homes, with 52.67% Hispanic patients and 44.06% African American patients. Home health care was the most common discharge disposition, accounting for 31.16% of Asian or Pacific Islander patients and 31.12% of Hispanic patients. A skilled nursing facility was the most frequent discharge destination for White patients at 14.28%, while it was the least common among Native American patients at 6.36%. The differences observed were statistically significant, with a p-value of less than 0.001. In the univariate analysis, without adjusting for confounders, the African American population had the highest mortality rate at 9.76%. Native Americans followed this at 8.51% and Asian or Pacific Islanders at 8.09%. The Hispanic population had the lowest mortality rate at 5.04% (p<0.001). The median length of stay varies significantly, with the highest length observed in the African-American population and others with a mean length of stay of 8 days, and the least in Asian or Pacific Islanders with 6 days. The total hospitalization charges also varied significantly, with the highest median total charges observed in Other minor groups (

$129,606) and Hispanic population (

$123,703), and the lowest among Native American patients (

$74,064) (p<0.001). Most hospitalizations across all racial groups were for non-elective admissions (p<0.001). The racial inequities in admission and disposition outcomes and healthcare utilization among cholangiocarcinoma patients are summarized in

Table 2 and

Figure 1.

Multivariate logistic regression analysis was also performed after adjusting for confounders and White as the reference group. Compared to White patients, African-American (AOR 0.70, 95% CI: 0.54–0.89, p = 0.004), Hispanic (AOR 0.62, 95% CI: 0.50–0.77, p < 0.001), and Asian or Pacific Islander patients (AOR 0.67, 95% CI: 0.51–0.89, p = 0.006) had significantly lower odds of elective admission, while Native American patients had similar odds (AOR 1.16, 95% CI: 0.53–2.54, p = 0.38). The odds of death were as follows: African-American patients had significantly higher odds (AOR 1.44, 95% CI: 1.10–1.90, p = 0.007) and Hispanic patients had lower odds (AOR 0.70, 95% CI: 0.51–0.96, p = 0.02) compared to White patients, with no significant difference observed for Asian or Pacific Islander or Native American patients. The multivariate regression analysis affecting racial inequities in admission and Mortality of cholangiocarcinoma patients is summarized in

Table 3.

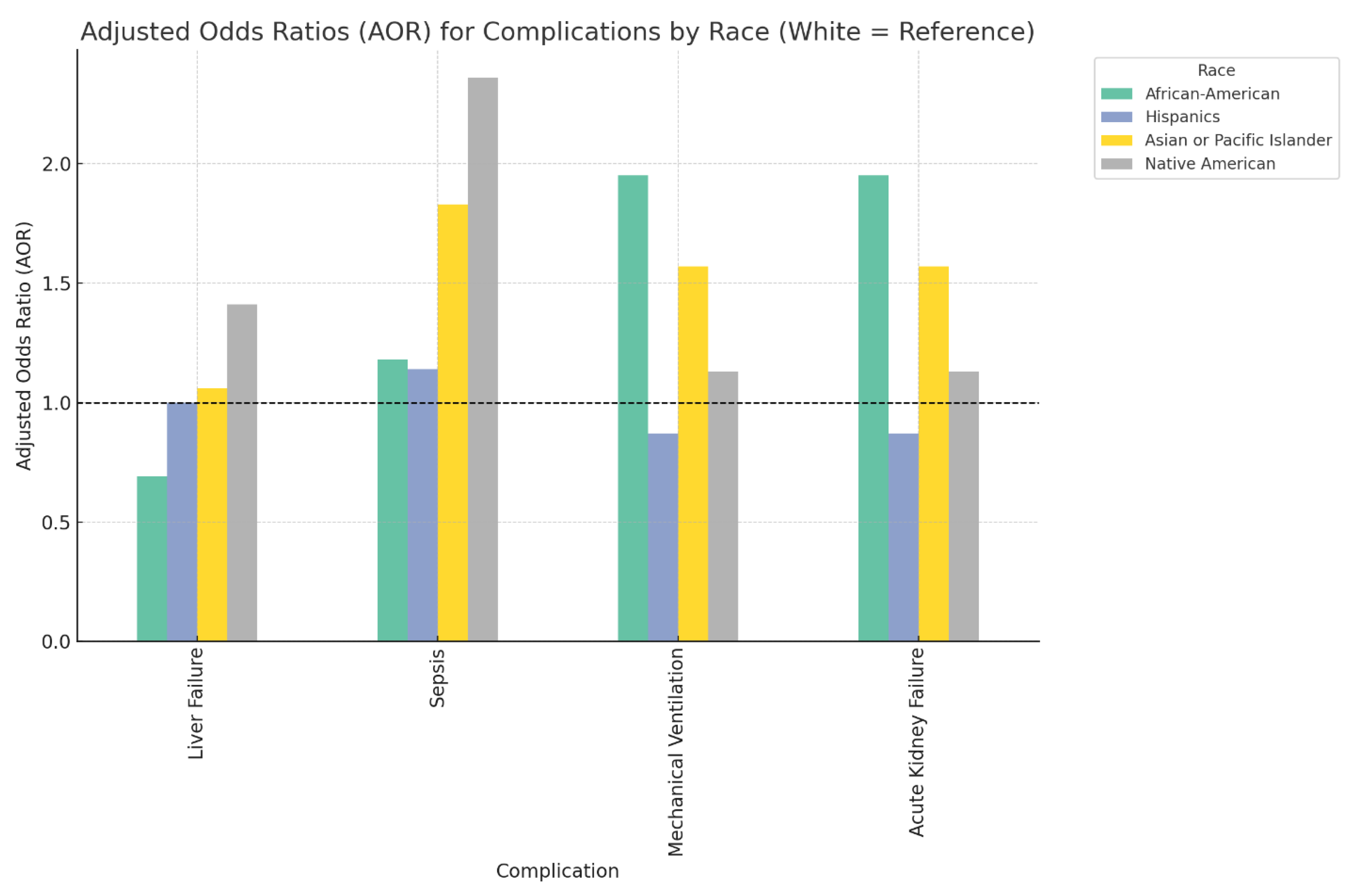

3.3. In-Hospital Complications

Compared to White patients, African-American patients demonstrated a significantly lower likelihood of developing liver failure during hospitalization (AOR 0.69, 95% CI: 0.49–0.97, p = 0.03). However, they were nearly twice as likely to require mechanical ventilation (AOR 1.95, 95% CI: 1.30–2.92, p = 0.001) and to experience acute kidney failure (AOR 1.95, 95% CI: 1.30–2.92, p = 0.00). In contrast, Asian or Pacific Islander patients had a markedly increased risk of developing sepsis (AOR 1.83, 95% CI: 1.41–2.36, p<0.001), as did Native American patients (AOR 2.36, 95% CI: 1.12–5.02, p = 0.02), when compared to White patients. Notably, there were no statistically significant differences in the risk of these in-hospital complications for Hispanic patients relative to White patients. The racial differences in the complications associated with Cholangiocarcinoma are summarized in

Figure 2 and

Table 4

4. Discussion

The results of this study underscore the presence of notable racial disparities among patients hospitalized with cholangiocarcinoma in the United States, as evidenced by the analysis of 2022 National Inpatient Sample (NIS) data. The investigation reveals that hospitalization patterns, clinical outcomes, and healthcare utilization exhibited significant variability across distinct racial cohorts. The age distribution of cholangiocarcinoma indicates that the incidence of this cancer increases with age across all racial groups, with the highest rates observed among older adults. Interestingly, while the incidence of cholangiocarcinoma is nearly twice as high in Asians compared to whites [

4,

9], our analysis showed that the overall distribution was higher in the white older population, followed by Native Americans and Asians.

The National data indicate that mortality rates associated with cholangiocarcinoma have risen across all racial groups. Our analysis focused on all racial groups compared to previous smaller studies. Notably, the highest increase occurred among African-Americans, with a 45% rise in mortality from 2000 to 2014; a 22% increase followed this in mortality rates among Asians, and a 20% increase among Whites during the same period [

10]. In our study, we found that African Americans had significantly worse in-hospital outcomes compared to Whites, followed by Native Americans and Asians. These findings highlight persistent disparities in cholangiocarcinoma outcomes and raise essential questions about the underlying systemic factors driving these inequities across groups.

The disparities observed in cholangiocarcinoma outcomes across racial groups are likely influenced by a combination of socioeconomic and systemic factors [

5]. Our analysis was consistent with national data demonstrating higher mortality rates among minority populations [

5,

11]. Socioeconomic status, insurance coverage, and access to quality post-acute care are critical determinants of outcomes. Prior research has shown that Black patients are less likely to receive surgical intervention for cholangiocarcinoma, and that lack of private insurance and lower income are associated with decreased overall survival [

5]. This evidence highlights the urgent need for targeted interventions that address social determinants of health and improve access to high-quality care for minority patients with cholangiocarcinoma. Additionally, it emphasizes the importance of including diverse populations in research and clinical trials to inform equitable treatment guidelines.

Significant racial disparities were observed in the in-hospital complications of cholangiocarcinoma patients. African Americans were less likely to develop acute liver failure compared to white populations; however, the risk of mechanical ventilation and development was twice in these populations. These coincide with previous studies that reported higher adverse outcomes and resource utilization among African Americans with cholangiocarcinoma [

11].

Discharge disposition reflects and can significantly influence disparities in healthcare outcomes. Our data indicates that White patients, who are often in higher income brackets, are more likely to be discharged to skilled nursing facilities. These facilities typically offer more comprehensive post-acute care. In contrast, African-Americans, Hispanics, and Native American patients, who are disproportionately found in lower income brackets, are more frequently discharged to home or with home health services. Previous research has shown that access to higher-quality post-discharge care, such as that provided by Skilled nursing facilities, can lead to improved recovery and long-term outcomes [

12]. Conversely, limited access to such care may contribute to higher readmission rates and poorer survival outcomes [

12].

As we analyze these results, it is vital to consider the broader implications for healthcare delivery and policy aimed at improving the quality of care for marginalized racial groups. Understanding such health outcome variations among racial groups is crucial for developing tailored diagnostic and management protocols, ensuring equitable treatment efficacy.

Limitations of the Study

The NIS database does not contain comprehensive patient-level information, including details about medications, laboratory results, and tumor features, which could significantly affect outcomes in cholangiocarcinoma but were not factored into our analysis [

13,

14]. Consequently, we could not rule out these factors as potential confounders in the outcomes we examined. Additionally, since the NIS relies on administrative coding, there is a risk of misclassification or coding inaccuracies, which may impact the validity of the diagnoses and complication rates reported [

13,

14]. The cross-sectional nature of our study also constrains our capacity to establish causal links between race, socioeconomic status, and patient outcomes; we can only discuss the associations evident in the data [

15]. Although we tried to adjust for various confounding factors, unmeasured variables could still influence the results.

Furthermore, since the NIS data is limited to hospitalized patients in the United States, our findings may not apply to populations in other countries or individuals who did not require hospitalization [

14]. The NIS database also does not track long-term outcomes or rates of readmission, which limits our ability to analyze long-term survival or the effects of repeated hospital stays [

13]. Nevertheless, the significant disparities related to race and socioeconomic status identified in our research highlight the critical need for further studies and targeted interventions aimed at addressing inequalities in the care and outcomes of cholangiocarcinoma patients [

16].

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, this study highlights pronounced racial and socioeconomic disparities in the hospitalization outcomes of patients with cholangiocarcinoma. African American, Native American, and Asian patients face disproportionately higher mortality and poorer in-hospital outcomes compared to their White counterparts. Moreover, factors such as lower income and less access to skilled post-discharge care contribute to these adverse outcomes among minority populations. These findings emphasize the critical need for focused healthcare strategies and policy reforms aimed at reducing these gaps and promoting equitable treatment and support for all individuals affected by cholangiocarcinoma.

References

- Tyson, Gia L., and Hashem B. El-Serag. "Risk factors for cholangiocarcinoma." Hepatology 54.1 (2011): 173-184.

- Shaib, Yasser, and Hashem B. El-Serag. "The epidemiology of cholangiocarcinoma." Seminars in liver disease. Vol. 24. No. 02. Copyright© 2004 by Thieme Medical Publishers, Inc., 333 Seventh Avenue, New York, NY 10001, USA., 2004.

- Javle M, Lee S, Azad NS, Borad MJ, Kate Kelley R, Sivaraman S, Teschemaker A, Chopra I, Janjan N, Parasuraman S, Bekaii-Saab TS. Temporal Changes in Cholangiocarcinoma Incidence and Mortality in the United States from 2001 to 2017. Oncologist. 2022 Oct 1;27(10):874-883. [CrossRef]

- Mosadeghi S, Liu B, Bhuket T, Wong RJ. Sex-specific and race/ethnicity-specific disparities in cholangiocarcinoma incidence and prevalence in the USA: An updated analysis of the 2000-2011 Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results registry. Hepatol Res. 2016 Jun;46(7):669-77. Epub 2015 Nov 12. PMID: 26508039. [CrossRef]

- Lee RM, Liu Y, Gamboa AC, Zaidi MY, Kooby DA, Shah MM, Cardona K, Russell MC, Maithel SK. Race, ethnicity, and socioeconomic factors in cholangiocarcinoma: What is driving disparities in receipt of treatment? J Surg Oncol. 2019 Sep;120(4):611-623. Epub 2019 Jul 13. PMID: 31301148; PMCID: PMC6752195. [CrossRef]

- Li, Junshan, et al. "Diabetes mellitus and the risk of cholangiocarcinoma: an updated meta-analysis." Gastroenterology Review/Przegląd Gastroenterologiczny 10.2 (2015): 108-117.

- Li, Jun-Shan, et al. "Obesity and the risk of cholangiocarcinoma: a meta-analysis." Tumor Biology 35 (2014): 6831-6838.

- De Groen, Piet C., et al. "Biliary tract cancers." New England Journal of Medicine 341.18 (1999): 1368-1378.

- Baidoun F, Sarmini MT, Merjaneh Z, Moustafa MA. Controversial risk factors for cholangiocarcinoma. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022 Mar 1;34(3):338-344. PMID: 3477545. [CrossRef]

- Yao KJ, Jabbour S, Parekh N, Lin Y, Moss RA. Increasing mortality in the United States from cholangiocarcinoma: an analysis of the National Center for Health Statistics Database. BMC Gastroenterol. 2016 Sep 21;16(1):117.

- 0527-z. PMID: 27655244; PMCID: PMC5031355.

- Antwi SO, Mousa OY, Patel T. Racial, Ethnic, and Age Disparities in Incidence and Survival of Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma in the United States; 1995-2014. Ann Hepatol. 2018 July - August,17(4):604-614. PMID: 29893702. [CrossRef]

- Yueping Liu, Xin Xu & Xiaoyan Ye. (2024) The benefits of an offline to online cognitive behavioral stress management regarding anxiety, depression, spiritual well-being, and quality of life in postoperative intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma patients. Asia-Pacific Journal of Clinical Oncology.

- Vaibhav Wadhwa, Yash Jobanputra, Prashanthi N. Thota, K.V. Narayanan Menon, Mansour A. Parsi, Madhusudhan R. Sanaka, Healthcare utilization and costs associated with cholangiocarcinoma, Gastroenterology Report, Volume 5, Issue 3, August 2017, Pages 213–218. [CrossRef]

- https://hcup-us.ahrq.gov/db/nation/nis/nisdbdocumentation.js.

- Mojtahedi, Z., Yoo, J. W., Callahan, K., Bhandari, N., Lou, D., Ghodsi, K., & Shen, J. J. (2021). Inpatient Palliative Care Is Less Utilized in Rare, Fatal Extrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma: A Ten-Year National Perspective. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(19), 10004. [CrossRef]

- Ransome, E., Tong, L., Espinosa, J., Chou, J., Somnay, V., & Munene, G. (2019). Trends in surgery and disparities in receipt of surgery for intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma in the US: 2005–2014. Journal of Gastrointestinal Oncology, 10(2), 339. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).